| Revision as of 20:59, 31 October 2013 editWeldNeck (talk | contribs)842 edits per WP:LEDE← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:17, 19 December 2024 edit undoGoszei (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Template editors86,886 editsm get closer to WP:SDSHORT targetTag: Shortdesc helper | ||

| (652 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1950 U.S. mass killing of civilians during the Korean War}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=July 2019}} | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| {{Infobox civilian attack | {{Infobox civilian attack | ||

| | title = No Gun Ri |

| title = No Gun Ri massacre | ||

| | partof = ] | | partof = the ] | ||

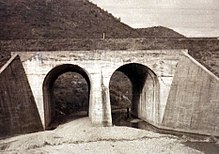

| | image = No Gun Ri bridge-1960.jpg | | image = No Gun Ri bridge-1960.jpg | ||

| | alt = The twin-underpass railroad bridge at No Gun Ri, South Korea, in 1960. Ten years earlier, the U.S. military killed a large number of South Korean refugees under and around the bridge, early in the Korean War. | | alt = The twin-underpass railroad bridge at No Gun Ri, South Korea, in 1960. Ten years earlier, members of the U.S. military killed a large number of South Korean refugees under and around the bridge, early in the Korean War. | ||

| | caption = The twin-underpass railroad bridge at No Gun Ri, South Korea, in 1960. Ten years earlier, the U.S. military killed a large number of South Korean refugees under and around the bridge, early in the Korean War. | | caption = The twin-underpass railroad bridge at No Gun Ri, South Korea, in 1960. Ten years earlier, members of the U.S. military killed a large number of South Korean refugees under and around the bridge, early in the Korean War. | ||

| | map = {{location map | |

| map = {{location map |South Korea |lat_deg=36.2153 |lon_deg=127.8803 |caption= }} | ||

| | location = ], South Korea | | location = ], ] (also known as No Gun Ri) | ||

| | target = | | target = | ||

| | coordinates = {{ |

| coordinates = {{Coord|36|12|55|N|127|52|49|E|type:event_region:KR|display=inline,title}} | ||

| | date = {{start date|1950|07|26}} – {{end date|1950|07|29}} | | date = {{start date|1950|07|26}} – {{end date and age|1950|07|29}} | ||

| | type = | | type = Shooting and air attack | ||

| | fatalities = At least 163 dead or missing |

| fatalities = At least 163 dead or missing, according to South Korea<br /> About 400 dead, according to survivors<br /> Unknown, according to the U.S. | ||

| | injuries = | | injuries = | ||

| | |

| victims = South Korean refugees | ||

| | perpetrators = |

| perpetrators = ] | ||

| ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''No Gun Ri Massacre''' occurred on July 26–29, 1950, early in the ], when an undetermined number of South Korean refugees were killed by the 2nd Battalion, ] Regiment (and a U.S. air attack) at a railroad bridge near the village of ], {{convert|100|mi}} southeast of Seoul. Estimates of the dead have ranged from dozens to 500. In 2005, a South Korean government report listed 163 dead or missing and 55 wounded and added that many other victims' names were not reported. The ] cites the number of casualties as "unknown". | |||

| The '''No Gun Ri massacre''' ({{Korean|hangul=노근리 양민 학살 사건}}) was a mass killing of South Korean refugees by U.S. military air and ground fire near the village of ] ({{Korean|hangul=노근리|labels=no}}) in central South Korea between July 26 and 29, 1950, early in the ]. In 2005, a South Korean government inquest certified the names of 163 dead or missing and 55 wounded, and added that many other victims' names were not reported. The No Gun Ri Peace Foundation estimates 250–300 were killed, mostly women and children. | |||

| The ] allegations were little known outside Korea until the publication of a series of controversial<ref>Joseph L. Galloway. . US News and World Reports. September 14,2000</ref><ref>Judith Greer. . Salon.com. June 3, 2002</ref> ] (AP) reports in 1999 containing interviews with 7th Cavalry veterans some of whom corroborated Korean survivors' accounts. The AP also uncovered orders to fire on ]s approaching US positions because of the KPA's use of these groups to cloak troop and guerrilla movements. Based on interviews with surviving US veterans and aerial reconnaissance footage taken shortly after the event, ] conducted an investigation and, in 2001, concluded the three-day event was "an unfortunate tragedy inherent to war and not a deliberate killing", rejecting survivors' demands for an apology and compensation. | |||

| The incident was little-known outside Korea until publication of an ] (AP) story in 1999 in which veterans of the U.S. Army unit involved, the ], corroborated survivors' accounts. The AP also uncovered declassified U.S. Army orders to fire on approaching civilians because of reports of ]n infiltration of refugee groups. In 2001, the ] conducted an investigation and, after previously rejecting survivors' claims, acknowledged the killings, but described the three-day event as "an unfortunate tragedy inherent to war and not a deliberate killing". Then-President ] issued a statement of regret, adding the next day that "things happened which were wrong", but survivors’ demands for an apology and compensation were rejected. | |||

| South Korean investigators disagreed with Pentagon findings, saying they believed 7th Cavalry troops were ordered to fire on the refugees although no evidence could be found corroborating this. The survivors' group called the U.S. report a "]". Additional archival documents later emerged showing U.S. commanders authorizing the use of lethal force against refugees during this period, declassified documents found but not disclosed by the Pentagon investigators. Among them was a report by the U.S. ] in South Korea in July 1950 that the U.S. military had adopted a ]-wide policy of firing on approaching refugee groups based on the KPA’s infiltration of refugees during the battle of Taejon. Despite demands, the U.S. investigation was not reopened. A South Korean excavation of the site in 2007 found no bones or other remains.<ref name="Yonhap">"http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/news/2007/08/22/0200000000AEN20070822002500315.HTML Search for remains of Nogeun-ri massacre likely to end with no remains found]", Yonhap, Aug. 22, 2007.</ref> | |||

| South Korean investigators disagreed with the U.S. report, saying they believed that 7th Cavalry troops were ordered to fire on the refugees. The survivors' group called the U.S. report a "whitewash". The AP later discovered additional archival documents showing that U.S. commanders ordered troops to "shoot" and "fire on" civilians at the war front during this period; these declassified documents had been found but not disclosed by the Pentagon investigators. Among the undisclosed documents was a letter from the U.S. ambassador in South Korea stating that the U.S. military had adopted a theater-wide policy of firing on approaching refugee groups. Despite demands, the U.S. investigation was not reopened. | |||

| Prompted by the exposure of No Gun Ri, survivors of similar alleged incidents in 1950–1951 filed reports with the Seoul government. In 2008 an investigative commission said more than 200 cases of alleged large-scale civilian killings by the U.S. military had been registered, mostly air attacks. | |||

| Prompted by the exposure of No Gun Ri, survivors of similar alleged incidents from 1950 to 1951 filed reports with the Seoul government. In 2008, an investigative commission said more than 200 cases of alleged large-scale killings by the U.S. military had been registered, mostly air attacks. | |||

| == Killings == | |||

| == |

==Background== | ||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Korean War}} | {{main|Korean War}} | ||

| ] | |||

| The division of Japan's former Korean colony into two zones at the end of World War II led to years of border skirmishing between U.S.-allied South Korea and Soviet-allied North Korea. On June 25, 1950, the North Korean army invaded the south to try to reunify the peninsula, touching off a ] that would draw in both the U.S. and Chinese militaries and end in an armistice and stalemate three years later. | |||

| The ] at the end of ] led to years of border skirmishing between U.S.-allied South Korea and Soviet-allied North Korea. On June 25, 1950, the ] invaded the south to try to reunify the peninsula, beginning the Korean War.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.history.com/topics/korea/korean-war |title=Korean War |work=History.com |date=May 11, 2022 |access-date=August 6, 2019 |archive-date=August 28, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190828224246/https://www.history.com/topics/korea/korean-war |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The U.S. dispatched occupation forces from Japan to fight alongside the South Korean army. These green American troops were insufficiently trained, poorly equipped and often led by inexperienced officers and NCO’s. In particular, they lacked training in how to deal with war-displaced civilians.<ref name="DAIG">Office of the Inspector General, Department of the Army. ]. Washington, D.C. January 2001</ref>{{rp|iv-v}} In the two weeks after the Americans first arrived on July 5, 1950, the U.S. Army estimated that 380,000 South Korean civilians fled south, passing through U.S. and South Korean lines, as the defending forces reeled in retreat.<ref name="Appleman">{{cite book | last1 = Appleman | first1 = Roy E. | title = South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu (June–November 1950) | publisher = Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army | year = 1961 | location = Washington, D.C. | url = http://www.history.army.mil/BOOKS/KOREA/20-2-1/toc.htm | accessdate = February 8, 2012}}</ref>{{rp|251}} | |||

| The invasion caught South Korea and its American ally by surprise, and sent the defending South Korean forces into retreat. The U.S. moved troops from Japan to fight alongside the South Koreans. The first troops landed on July 1, and by July 22, three U.S. Army divisions were in Korea, including the ].<ref name="Appleman"/>{{rp|61, 197}} These American troops were insufficiently trained, poorly equipped, and often led by inexperienced officers. Of particular relevance was that they lacked training in dealing with war-displaced civilians.<ref name="DAIG">Office of the Inspector General, Department of the Army. ]. Washington, D.C. January 2001</ref>{{rp|iv–v}} The combined U.S. and South Korean forces were initially unable to stop the North Korean advance, and continued to retreat throughout July.<ref name="Appleman">{{cite book |last1=Appleman |first1=Roy E. |title=South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu (June–November 1950) |publisher=Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army |year=1961 |location=Washington, D.C. |url=http://www.history.army.mil/BOOKS/KOREA/20-2-1/toc.htm |access-date=February 8, 2012 |archive-date=February 7, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140207235336/http://www.history.army.mil/books/korea/20-2-1/toc.htm |url-status=dead}}</ref>{{rp|49–247}} | |||

| With large gaps in their front lines and refugees fleeing the onrush of the North Korean advance, the Americans were sometimes attacked from behind, and reports spread that disguised North Korean soldiers were infiltrating south with refugee columns, a continuing concern throughout the war's first year.<ref name="DAIG" />{{rp|v}} During the ] in early July, 1950, North Korean infiltration teams provided accurate and detailed information on the location and strength of the ] providing the KPA with the intelligence needed to perform a coordinated assault, quickly routing the 3-21 from its positions.<ref name="Appleman" />{{rp|98}} Again during the ] later in mid July, hundreds of North Korean soldiers, many dressed in white to disguise themselves as refugees, infiltrated behind the ] and played a crucial role in the defeat of the 24th at Taejon resulting in the capture of ] the conflict's highest ranking ]. <ref>Bill Sloan. "The Darkest Summer: Pusan and Inchon 1950: The Battles That Saved South Korea--and the Marines--from Extinction". Simon and Schuster, Nov 10, 2009. pg 72</ref> | |||

| Two days before the incident at No Gun Ri, a company from the ] was reportedly attacked by North Korean irregulars who infiltrated a crowd of refugees west of ].<ref> {{cite news | first = Richard J.H. | last = Johnston | title = Guile Big Weapon of North Koreans | date = July 27, 1950 | work = The New York Times | pages = 1}}</ref> These infiltrators also established a roadblock behind the 8th Cavarly’s position, cutting them off from the rest of the American forces, wounding Battalion’s commanding officer, and attacking rear echelon field artillery units supporting the rescue effort of the trapped 8th Cav soldiers. <ref name="Appleman" />{{rp|198}} Adding to this confusing situation, a July 23, 1950 ] intelligence report stated almost all refugees were searched over one 24-hour period on the main road and none was found carrying arms or uniforms.<ref>Eighth U.S. Army. July 23, 1950. Interrogation report. "North Korean methods of operation". Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2. Cited in {{cite book | last1 = Hanley | first1 = Charles J. | title = Truth and Reconciliation in South Korea: Between the Present and Future of the Korean Wars | chapter = No Gun Ri: Official Narrative and Inconvenient Truths | editors = Jae-Jung Suh | publisher = Routledge | year = 2012 | location = London and New York | pages = 74 | isbn = 978-0-415-62241-7}}</ref> But three days later ] ], ] commander, told rear-echelon reporters he suspected most of the refugee movement towards the US defensive positions were North Korean infiltrators.<ref>''The Associated Press'', July 26, 1950.</ref> | |||

| In the two weeks following the ] on July 5, the U.S. Army estimated that 380,000 South Korean civilians fled south, passing through the retreating U.S. and South Korean lines.<ref name="Appleman"/>{{rp|251}} With gaps in their lines, U.S. forces were attacked from the rear,<ref name="Appleman"/>{{rp|131, 158, 202}} and reports spread that disguised North Korean soldiers were infiltrating refugee columns.<ref name="Williams">{{cite news |last=Williams |first=Jeremy |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/coldwar/korea_usa_01.shtml |title=Kill 'em All: The American Military in Korea |work=British Broadcasting Corp. |date=2011-02-17 |access-date=2015-08-13 |archive-date=December 31, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191231184300/http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/coldwar/korea_usa_01.shtml |url-status=live }}</ref> Because of these concerns, orders were issued to fire on Korean civilians in front-line areas, orders discovered decades later in declassified military archives.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Occurrence at Nogun-ri Bridge |journal=Critical Asian Studies |date=December 2001 |last=Cumings |first=Bruce |volume=33 |issue=4 |page=512 |issn=1467-2715}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=Williams |first=Jeremy |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/coldwar/korea_usa_01.shtml |title=Kill 'em All: The American Military in Korea |work=British Broadcasting Corp. |date=2011-02-17 |access-date=2015-08-13 |quote=Declassified military documents recently found in the U.S. National Archives show clearly how US commanders repeatedly, and without ambiguity, ordered forces under their control to target and kill Korean refugees caught on the battlefield. |archive-date=December 31, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191231184300/http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/coldwar/korea_usa_01.shtml |url-status=live }}</ref> Among those issuing the orders was 1st Cavalry Division commander ] ], who deemed Koreans left in the war zone to be "enemy agents", according to U.S. war correspondent O.H.P. King and U.S. diplomat Harold Joyce Noble.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Noble |first1=Harold Joyce |title=Embassy at War |location=Seattle |publisher=University of Washington Press |year=1975 |page=152 |isbn=978-0-295-95341-0}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=King |first1=O.H.P. |title=Tail of the Paper Tiger |location=Caldwell, Idaho |publisher=The Caxton Printers, Ltd. |year=1962 |pages=358–59}}</ref> On the night of July 25, that division's 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment,<ref group=nb>The 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division, Eighth U.S. Army, was composed of E, F, G, and H Companies</ref> hearing of an enemy breakthrough, fled rearward from its forward positions, to be reorganized the next morning, digging in near the village of Nogeun-ri (also romanized as No Gun Ri), 100 miles southeast of ].<ref name="Appleman"/>{{rp|203}}<ref>{{cite book |last1=Chandler |first1=Melbourne C. |title=Of Garryowen in Glory: The History of the 7th U.S. Cavalry |location=Annandale, Virginia |publisher=The Turnpike Press |year=1960 |page=246}}</ref> Later that day, on July 26, 1950, these troops saw hundreds of refugees approaching, many from the nearby villages of Chu Gok Ri and Im Ke Ri.<ref name="TBANGR">{{cite book |author1=Charles J. Hanley |author2=Martha Mendoza |author3=Sang-hun Choe |title=The Bridge at No Gun Ri: A Hidden Nightmare from the Korean War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FVInBgAAQBAJ |access-date=November 16, 2015 |year=2001 |publisher=Henry Holt and Company |location=New York, New York |isbn=978-1-4668-9110-4}}</ref>{{rp|90, 116}} | |||

| An official 25th ID ] describes the refugee predicament they were faced with in the early days of the war: | |||

| == Killings == | |||

| <blockquote>No one desired to shoot innocent people, but many of the innocent-looking refugees dressed in the traditional white clothes of the Koreans turned out to be North Korean soldiers transporting ammunition and heavy weapons in farm wagons and carrying military equipment in packs on their backs. They were observed many times changing from uniforms to civilian clothing and back into uniform. There were so many refugees that it was impossible to screen and search them all<ref>War Diary, 25th Infantry Division, July 24-30.</ref> </blockquote> | |||

| ===Events of July 25 to 29, 1950=== | |||

| On that day, one of Gay's front-line units, the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, dug in near the village of No Gun Ri, was faced with an approaching group of refugees, mostly from the nearby villages of Chu Gok Ri and Im Ke Ri. | |||

| ] | |||

| On July 25, as North Korean forces seized the town of Yongdong, 7 miles (11 km) west of No Gun Ri, U.S. troops were evacuating nearby villages, including hundreds of residents of Chu Gok Ri and Im Ke Ri. These villagers were joined by others as they walked down the main road south, and the estimated 600 refugees spent the night by a riverbank near Ha Ga Ri village, 3.5 miles (5.5 km) west of No Gun Ri. Seven refugees were killed by U.S. soldiers when they strayed from the group during the night. In the morning of July 26, the villagers found that the escorting soldiers had left. They continued down the road, were stopped by American troops at a roadblock near No Gun Ri, and were ordered onto the parallel railroad tracks, where U.S. soldiers searched them and their belongings, confiscating knives and other items. The refugees were resting, spread out along the railroad embankment around midday, when military aircraft strafed and bombed them.<ref name="Committee">{{cite book |last1=Committee for the Review and Restoration of Honor for the No Gun Ri Victims |title=No Gun Ri Incident Victim Review Report |publisher=Government of the Republic of Korea |year=2009 |location=Seoul |isbn=978-89-957925-1-3}} Committee members included South Korean Prime Minister Lee Hae-chan, chairman, and Foreign Minister Ban Ki-moon, later U.N. secretary-general.</ref>{{rp|69–72}} Recalling the air strike, Yang Hae-chan, a 10-year-old boy in 1950, said the attacking planes returned repeatedly, and "chaos broke out among the refugees. We ran around wildly trying to get away."<ref name="WDR">], Germany. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160314171912/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WhjhlG97Whg |date=March 14, 2016 }} March 19, 2007, retrieved August 17, 2015.</ref> He and another survivor said that soldiers reappeared and began shooting the wounded on the tracks.<ref name="MBC">Munwha Broadcasting Corp., South Korea, "No Gun Ri Still Lives On: The Truth Behind That Day," September 2009.</ref><ref name="Struck">{{cite news |last=Struck |first=Doug |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/inatl/longterm/korea/korea.htm |title=U.S., S.Korea gingerly probe the past |newspaper=The Washington Post |date=1999-10-27 |quote='They were checking every wounded person and shooting them if they moved,' said Chung (Koo-hun). |access-date=September 6, 2017 |archive-date=July 8, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180708015739/https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/inatl/longterm/korea/korea.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Survivors first sought shelter in a small culvert beneath the tracks, but soldiers and U.S. ground fire drove them from there into a double tunnel beneath a concrete railroad bridge. Inside the bridge underpasses, each 80 feet (24 m) long, 22 feet (6.5 m) wide and 40 feet (12 m) high, they came under heavy machine gun and rifle fire from 7th Cavalry troops from both sides of the bridge.<ref name="Committee"/>{{rp|71}} "The American soldiers played with our lives like boys playing with flies," said Chun Choon-ja, a 12-year-old girl at the time.<ref name="AP Original">{{cite news |title=War's hidden chapter: Ex-GIs tell of killing Korean refugees |date=September 29, 1999 |agency=Associated Press}}</ref> "Children were screaming in fear and adults were praying for their lives, and the whole time they never stopped shooting," said survivor Park Sun-yong, whose 4-year-old son and 2-year-old daughter were killed, while she was badly wounded.<ref name="WDR"/> | |||

| Two communications specialists, Larry Levine and James Crume, said they remembered orders to fire on the refugees coming to the 2nd Battalion command post from a higher level, probably from 1st Cavalry Division. They recalled the ground fire beginning with a mortar round landing among the refugee families, followed by what Levine called a "frenzy" of small-arms fire.<ref>{{cite news |first=Richard |last=Pyle |title=Ex-GIs: U.S. troops in Korea War had orders to shoot civilians |date=November 21, 2000 |agency=Associated Press}}</ref><ref name="BBC"/> Some battalion veterans recalled front-line company officers ordering them to open fire.<ref>{{cite news |last=October Films |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pws_qyQnCcU |title=Kill 'Em All: American War Crimes in Korea |work=BBC ] |date=2002-02-01 |access-date=2015-09-16 |quote=Joseph Jackman: 'The old man (company commander), yes, right down the line he's running down the line, "Kill 'em all!" ... I don't know if they were soldiers or what. Kids, there was kids out there, it didn't matter what it was, 8 to 80, blind, crippled or crazy, they shot 'em.' |archive-date=April 18, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150418172941/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pws_qyQnCcU |url-status=live }}</ref> "It was assumed there were enemy in these people," said ex-rifleman Herman Patterson.<ref name="AP Original"/> "They were dying down there. I could hear the people screaming," recalled Thomas H. Hacha of the sister 1st Battalion, observing nearby.<ref name="WDR"/> Others said some soldiers held their fire.<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Thompson |first=Mark |title=The Bridge at No Gun Ri |magazine=Time |date=1999-10-11 |quote=(Ex-Pfc. Delos) Flint estimates half the troops near him fired on the civilians, and half—including himself—refused. 'I couldn't see killing kids,' he says, 'even if they were infiltrators.'}}</ref> ] | |||

| === Events of 25–29 July 1950 === | |||

| As North Korean forces seized the central South Korean town of Yongdong on July 25, 1950, 1st Cavalry Division troops began evacuating villages in front of the enemy advance, including hundreds of residents of Chu Gok Ri and Im Ke Ri. As they headed down the main road south, they were joined by other refugees. That first night several were killed, apparently by American soldiers as they strayed from a roadside assembly area.<ref name="TBANGR">{{cite book | last1 = Hanley | first1 = Charles J. | last2 = Choe | first2 = Sang-Hun | last3 = Mendoza | first3 = Martha | title = ] | publisher = Henry Holt and Company | year = 2001 | location = New York, New York | isbn = 0-8050-6658-6}}</ref>{{rp|110–114}} The next day, July 26, the strung-out refugee column approached the No Gun Ri area, {{convert|5|mi}} from their homes, when they were stopped by U.S. troops, made to move to the parallel railroad tracks, and were searched. Survivors said warplanes soon appeared over the horizon and attacked the civilians.<ref name="TRCSummary">Truth and Reconciliation Commission of the Republic of Korea. 2007. Retrieved January 28, 2012.</ref> In a 2007 German television documentary Yang Hae-chan described the air attack: "Suddenly bombers flew over and opened fire without warning. They came back again and again firing at us. Chaos broke out among the refugees. We ran around wildly trying to get away. But in that first attack very many people were hit and killed."<ref>], Germany. March 19, 2007, 11:20–12:18 mins , retrieved January 28, 2012.</ref> | |||

| Trapped refugees began piling up bodies as barricades and tried to dig into the ground to hide.<ref name="BBC">{{cite news |last=October Films |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pws_qyQnCcU |title=Kill 'Em All: American War Crimes in Korea |work=BBC ] |date=2002-02-01 |access-date=2015-09-16 |quote=Yang Hae-chan: 'The floor inside the tunnel was a mix of gravel and sand. People clawed with their bare hands to make holes to hide in. Other people piled up the dead, like a barricade.' |archive-date=April 18, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150418172941/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pws_qyQnCcU |url-status=live }}</ref> Some managed to escape that first night, while U.S. troops turned searchlights on the tunnels and continued firing, said Chung Koo-ho, whose mother died shielding him and his sister.<ref name="Committee"/>{{rp|71}}<ref name="Newsweek">{{cite news |url=http://www.newsweek.com/i-still-hear-screams-168234 |title=I Still Hear Screams |work=Newsweek |date=1999-10-10 |access-date=September 21, 2015 |archive-date=March 5, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160305142316/http://www.newsweek.com/i-still-hear-screams-168234 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=No Gun Ri Still Lives On: The Truth Behind That Day |language=ko |work=Munwha Broadcasting Corp. |location=South Korea |date=September 2009 |quote=Chung Koo-ho: 'Even now if I close my eyes I can see the people who were dying, as they cried out someone's name.'}}</ref> By the second day, the gunfire was reduced to potshots and occasional fusillades when a trapped refugee moved or tried to escape. Some also recall planes returning that second day to fire rockets or drop bombs. Racked with thirst, survivors resorted to drinking blood-filled water from a small stream running under the bridge.<ref name="TBANGR"/>{{rp|137–38}} | |||

| According to the South Korean government, dug-in troops of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, also opened fire on the refugees, some of whom took shelter in a low, narrow culvert beneath the railroad embankment. Further firing forced them into a larger double tunnel beneath a railroad bridge. Also according to the South Korean government Seventh Cavalry soldiers continued to fire into both ends of the tunnels for the next three days.<ref name="TRCSummary" /> Survivor Park Sun-yong said corpses were piled up as shields against the gunfire: "Children were screaming in fear and the adults were praying for their lives, and the whole time they never stopped shooting."<ref name="WDR">], Germany. March 19, 2007. Retrieved January 28, 2012.</ref> Chung Koo-ho said in a 2009 South Korean documentary, "Even now if I close my eyes I can see the people who were dying, as they cried out someone's name."<ref name="MBC">Munwha Broadcasting Corp., South Korea, "No Gun Ri Still Lives On: The Truth Behind That Day," September 2009.</ref> | |||

| During the killings, the 2nd Battalion came under sporadic artillery and mortar fire from the North Koreans, who advanced cautiously from Yongdong. Declassified Army intelligence reports showed that the enemy front line was two miles or more from No Gun Ri late on July 28, the third day of the massacre.<ref name="Routledge">{{cite book |last1=Hanley |first1=Charles J. |title=Truth and Reconciliation in South Korea: Between the Present and Future of the Korean Wars |chapter=No Gun Ri: Official Narrative and Inconvenient Truths |editor=Jae-Jung Suh |publisher=Routledge |year=2012 |location=London and New York |pages=68–94 |isbn=978-0-415-62241-7}}</ref>{{rp|82–83}} That night, the 7th Cavalry messaged division headquarters, "No important contact has been reported by our 2nd Battalion." The refugee killings were not reported in surviving unit documents.<ref name="TBANGR"/>{{rp|142–43}} | |||

| Some veterans of the 7th Cavalry recounted a similar scene. "I shot, too. Shot at people. I don't know if they were soldiers or what. Kids, there was kids out there, it didn't matter what it was, 8 to 80, blind, crippled or crazy, they shot 'em all," Joseph Jackman, a G Company rifleman, told the ].<ref name="BBC">]: ''Kill 'Em All - American War Crimes in Korea''. ], October Films. February 1, 2002, 20:53 mins (Jackman), 30:50 mins (McCloskey).</ref> Norman L. Tinkler, an H Company machine gunner, remembered white-clad people coming down the railroad tracks toward the bridge, including "a lot of women and children. ... I was the one who pulled the trigger". He fired about 1,000 rounds and assumed "there weren't no survivors".<ref>{{cite news | title = Memories of a Massacre | date = July 23, 2000 | url = http://nl.newsbank.com/nl-search/we/Archives?p_product=WE&p_theme=we&p_action=search&p_maxdocs=200&s_dispstring=potter%20memories%20of%20a%20massacre%20AND%20date(all)&p_field_advanced-0=&p_text_advanced-0=(potter%20memories%20of%20a%20massacre)&xcal_numdocs=20&p_perpage=10&p_sort=YMD_date:D&xcal_useweights=no | work = Wichita (Kansas) Eagle | accessdate = February 17, 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite news | title = Kansas veteran's memories vivid of civilian deaths | date = September 30, 1999 | work = The Kansas City Star}}</ref> Thomas H. Hacha, dug in nearby with the sister 1st Battalion, witnessed the slaughter: "I could see the tracers (bullets) spinning around inside the tunnel ... and they were dying down there. I could hear the people screaming."<ref>], Germany. March 19, 2007, 21:10–22:00 mins, retrieved January 28, 2012.</ref> | |||

| In the predawn hours of July 29, the 7th Cavalry Regiment withdrew from No Gun Ri.<ref name="Appleman"/>{{rp|203}} That afternoon, North Korean soldiers arrived outside the tunnels and helped those still alive, about two dozen, mostly children, feeding them and sending them back toward their villages.<ref name="Newsweek"/><ref name="Choi">{{cite book |last1=Choi |first1=Suhi |title=Embattled Memories: Contested Meanings in Korean War Memorials |location=Reno |publisher=University of Nevada Press |year=2014 |page=24 |isbn=978-0-87417-936-1}}</ref> | |||

| Other veterans of the 7th Cavalry present during the events recall a dramatically different series of events. Buddy Wenzel who served with both G and H companies of the 2/7 during the war said that they briefly opened fire after coming under fire from the individuals in the refugee group: “The civilians started coming down the railroad tracks, on paths on both sides of the tracks. The front ones, there were like maybe 15 or 20 of them, and they were getting thicker beyond that. Somebody said, “Fire over their heads for a warning.” I got out of my hole with about 30 other guys; we all had M-1s. Now, we had one machine gun up on the railroad tracks and another air cooled machine gun on the right. Well when we fired over their heads they panicked. That’s when some of them started to run towards us. We were firing over them all this time. Then somebody yelled, “We’re being fired at,” then there was a bunch that started shooting into the refugees ... This all happened in a minute, but it all came out when we panicked ‘cause we thought we were getting shot at.” <ref name="BATEMAN">{{cite book | last1 = Robert Bateman | title = No Gun Ri: A Military History of the Korean War Incident | publisher = Stackpole Books | year = 2002 | location = | isbn = 978-0811717632}}. pg 118</ref> Wenzel also recalled that after being told to cease fire by a lieutenant another soldier found weapon near the dead refugees. | |||

| On July 29, 1950, three days after the killings began, the 7th Cavalry Regiment was withdrawn from those positions as the U.S. retreat continued.<ref name="Appleman" />{{rp|203}} | |||

| === Casualties === | === Casualties === | ||

| In the earliest published account of the killings, three weeks afterward, Chun Wook, a journalist with the North Korean 3rd Division troops who advanced to No Gun Ri, reported finding the area covered with layers of bodies and said about 400 people had been killed.<ref>Cho Sun In Min Bo newspaper, North Korea, August 19, 1950.</ref> Over the years, the survivors' own estimates of dead ranged from 300 to 500, with perhaps 150 wounded. In Pentagon interviews in 2000, 7th Cavalry veterans' estimates of No Gun Ri dead ranged from dozens to 300.<ref name="Committee">{{cite book | last1 = Committee for the Review and Restoration of Honor for the No Gun Ri Victims | title = No Gun Ri Incident Victim Review Report | publisher = Government of the Republic of Korea | year = 2009 | location = Seoul | isbn = 978-89-957925-1-3}}</ref>{{rp|107}} Homer Garza, a retired command sergeant major who as a corporal led a patrol through one No Gun Ri tunnel, said he saw 200 to 300 bodies piled up there, and most may have been dead.<ref name="WDR" /><ref>{{cite news | title = 1950 "shoot refugees" letter was known to No Gun Ri inquiry, but went undisclosed | date = April 13, 2007 | agency = Associated Press}}</ref>] | |||

| In the earliest published accounts of the killings, in August and September 1950, two North Korean journalists with the advancing northern troops reported finding an estimated 400 bodies in the No Gun Ri area, including 200 seen in one tunnel.<ref>{{cite news |last=Wook |first=Chun |title=400 Innocent Residents Massacred in Bombing and Strafing |language=ko |work=Cho Sun In Min Bo |date=1950-08-19 |quote=Indescribably gruesome scenes ... shrubs and weeds in the area and a creek running through the tunnels were drenched in blood, and the area was covered with two or three layers of bodies.}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=Korean Central News Agency |title=(Headline unavailable) |language=ko |work=Min Joo Cho Sun |date=1950-09-07 |quote=As we reached the tunnels, smells of blood disturbed us and the ground was drenched with blood. We could hear moans of those who were injured but were still alive.}}</ref> The survivors generally put the death toll at 400,<ref>{{cite news |last=Kang |first=K. Connie |title=Koreans Give Horrifying Accounts of Alleged Attack |work=] |date=1999-11-17}}</ref> including 100 in the initial air attack, with scores more wounded.<ref name="AP Original"/> In Pentagon interviews in 2000, 7th Cavalry veterans' estimates of No Gun Ri dead ranged from dozens to 300.<ref name="Committee"/>{{rp|107}} One who had a close look, career soldier Homer Garza, who led a patrol through one No Gun Ri tunnel, said that he saw 200 to 300 bodies piled up there.<ref name="WDR"/><ref>{{cite news |title=1950 'shoot refugees' letter was known to No Gun Ri inquiry, but went undisclosed |date=April 13, 2007 |agency=Associated Press}}</ref> | |||

| The U.S. Army's 2001 investigative report, citing 1950 aerial imagery, questioned the higher casualty estimates.<ref name="DAIG"/>{{rp|190–191}} ] In 2005, the South Korean government's Committee for the Review and Restoration of Honor for the No Gun Ri Victims, after a yearlong process of verifying claims through family registers, medical reports and other documents and testimony, certified the names of 150 No Gun Ri dead, 13 missing and 55 wounded, including some who later died of their wounds. It said reports were not filed on many other victims because of the passage of time and other factors. Of the certified victims, 41 percent were children under 15, and 70 percent were women, children or men over age 61.<ref name="Committee" />{{rp|247–249,328,278}} | |||

| In 2005, the South Korean government's Committee for the Review and Restoration of Honor for the No Gun Ri Victims, after a yearlong process of verifying claims through family registers, medical reports and other documents and testimony, certified the names of 150 No Gun Ri dead, 13 missing, and 55 wounded, including some who later died of their wounds. It said reports were not filed on many other victims because of the passage of time and other factors. Of the certified victims, 41 percent were children under 15, and 70 percent were women, children or men over age 61.<ref name="Committee"/>{{rp|247–49, 278, 328}}<ref name="218 killed">{{cite news |title=No Gun Ri victims officially recognized: 218 people |date=May 23, 2005 |url=http://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=102&oid=028&aid=0000112220 |work=] |access-date=2014-01-04 |language=ko |archive-date=July 25, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230725070151/https://n.news.naver.com/mnews/article/028/0000112220?sid=102 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The South Korean government-funded No Gun Ri Peace Foundation, which operates a memorial park and museum at the site, estimated in 2011 that 250–300 were killed.<ref name="newsis">{{cite news |last=Lee |first=B-C |url=http://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=102&oid=003&aid=0004768541 |title=노근리재단, 과거사 특별법 제정 세미나 개최 |language=ko |trans-title=No Gun Ri Foundation held special law seminar |work=] (online news agency) |location=Seoul |date=2012-10-15 |access-date=2015-06-02 |archive-date=June 4, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200604222930/https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=102&oid=003&aid=0004768541 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=In the Face of American Amnesia, The Grim Truths of No Gun Ri Find a Home |journal=The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus |date=2015-03-09 |last=Hanley |first=Charles J. |volume=13 |issue=10 |url=https://apjjf.org/2015/13/9/Charles-J.-Hanley/4294.html |access-date=2020-06-06 |archive-date=June 6, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200606194456/https://apjjf.org/2015/13/9/Charles-J.-Hanley/4294.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| == Aftermath == | == Aftermath == | ||

| ] | |||

| Information about the refugee killing reached the U.S. command in Korea and the Pentagon by late August 1950, in the form of a captured and translated North Korean military document that described the discovery.<ref>{{cite news | title = Captured North Korean document describes mass killings by U.S. troops | date = June 15, 2000 | agency = Associated Press}}</ref> Evidence of high-level knowledge also appeared a month later in a New York Times article from Korea, which reported, without further detail, that an unnamed high-ranking U.S. officer told the reporter that a U.S. Army regiment had shot "many civilians" that July.<ref>{{cite news | title = Stranded Enemy Soldiers Merge With Refugee Crowds in Korea | date = September 30, 1950 | url = http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F60D12F9395F147B93C2AA1782D85F448585F9 | work = The New York Times | accessdate = February 17, 2012}}</ref> | |||

| Information about the refugee killings reached the U.S. command in Korea and the Pentagon by late August 1950, in the form of a captured and translated North Korean military document, which reported the discovery of the massacre.<ref>{{cite news |title=Captured North Korean document describes mass killings by U.S. troops |date=June 15, 2000 |agency=Associated Press}}</ref> A South Korean agent for the U.S. counterintelligence command confirmed that account with local villagers weeks later, when U.S. troops moved back through the area, the ex-agent told U.S. investigators in 2000.<ref name="ROK">Ministry of Defense, Republic of Korea. ''The Report of the Findings on the No Gun Ri Incident''. Seoul, South Korea. January 2001.</ref>{{rp|199}} Evidence of high-level knowledge also appeared in late September 1950 in a ''New York Times'' article from Korea, which reported, without further detail, that an unnamed high-ranking U.S. officer told the reporter of the "panicky" shooting of "many civilians" by a U.S. Army regiment that July.<ref>{{cite news |last=Grutzner |first=Charles |url=https://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9907E3D8123BE13BBC4850DFBF66838B649EDE |title=Stranded Enemy Soldiers Merge With Refugee Crowds in Korea |work=] |date=1950-09-30 |access-date=February 11, 2017 |archive-date=March 5, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160305221834/http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9907E3D8123BE13BBC4850DFBF66838B649EDE |url-status=live }}</ref> No evidence has emerged, however, that the U.S. military investigated the incident at the time.<ref name="TBANGR"/>{{rp|170}} | |||

| === Petitions === | === Petitions === | ||

| During the U.S.-supported postwar autocracy of President ], survivors of No Gun Ri were too fearful of official retaliation to file public complaints.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Kim |first1=Dong-Choon |title=The Unending Korean War: A Social History |location=Larkspur, California |publisher=Tamal Vista Publications |year=2009 |page=viii |isbn=978-0-917436-09-3}}</ref> Survivor Yang Hae-chan said he was warned by South Korean police to stop telling others about the massacre.<ref name=Baik>{{cite journal |last1=Baik |first1=Tae-Ung |title=A War Crime against an Ally's Civilians: The No Gun Ri Massacre |journal=Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy |date=2001 |volume=15 |issue=2 |url=http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol15/iss2/3/ |access-date=June 16, 2015 |archive-date=January 9, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160109194306/http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol15/iss2/3/ |url-status=live }}</ref>{{rp|503}} Following the ] in 1960, which briefly established democracy in South Korea, former policeman ] filed the first petition to the South Korean and U.S. governments. His two small children had been killed and his wife, Park Sun-yong, badly wounded at No Gun Ri.<ref name=nytimes>{{cite news |first=Douglas |last=Martin |title=Chung Eun-yong, Who Helped Expose U.S. Killings of Koreans, Dies at 91 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/24/world/asia/chung-eun-yong-91-dies-helped-expose-us-killings-of-south-koreans.html?_r=0 |work=] |date=2014-08-22 |access-date=2014-08-31 |archive-date=April 3, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150403014137/http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/24/world/asia/chung-eun-yong-91-dies-helped-expose-us-killings-of-south-koreans.html?_r=0 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=South Korean who forced US to admit massacre has died |url=http://bigstory.ap.org/article/s-korean-who-forced-us-admit-massacre-has-died |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140903103144/http://bigstory.ap.org/article/s-korean-who-forced-us-admit-massacre-has-died |archive-date=2014-09-03 |agency=Associated Press |date=2014-08-06 |access-date=2014-08-31}}</ref> Over 30 petitions, calling for an investigation, apology, and compensation, were filed over the next decades, by Chung and later by a survivors' committee. Almost all were ignored, as was a petition to the U.S. and South Korean governments by the local Yongdong County Assembly.<ref name="Committee" />{{rp|126, 129, 135}} | |||

| {{quote box|width=25em|source = — excerpt from Chung's 1960 petition.<ref name="Committee" />{{rp|129,126}}|It goes beyond comprehension why they attacked and killed them with such cruelty. The U.S. government should take responsibility.}} | |||

| {{quote box|width=25em|source = — Excerpt from Chung's 1960 petition.<ref name="Committee" />{{rp|126}}|It goes beyond comprehension why they attacked and killed them with such cruelty. The U.S. government should take responsibility.}} | |||

| During the U.S.-supported postwar autocracy of President ], survivors of No Gun Ri did not file any public complaints. Following the ] in 1960, which briefly established democracy in South Korea, former policeman Chung Eun-yong filed the first petition to the South Korean and U.S. governments. His two small children had been killed and his wife badly wounded at No Gun Ri. Over 30 petitions, calling for an investigation, apology and compensation, were filed over the next decades – by Chung and later by a survivors' committee.<ref name="Committee" />{{rp|129,126}} | |||

| In 1994, Seoul newspapers reported on a book<ref>{{cite book |last1=Chung |first1=Eun-yong |title=Do You Know Our Pain? |location=Okcheon, South Korea |publisher=Podobat Publishing Co. |year=2020 |id=302-90-41252 |edition=English }}</ref> Chung published about the events of 1950, raising awareness of the allegations inside South Korea.<ref name="Committee" />{{rp|128}} In that same year, the U.S. Armed Forces Claims Service in Korea dismissed one No Gun Ri petition by asserting that any killings took place during combat. The survivors' committee retorted that there was no battle at No Gun Ri,<ref name="Young">{{cite book |last1=Young |first1=Marilyn |title=Crimes of War: Guilt and Denial in the Twentieth Century |chapter=An Incident at No Gun Ri |editor-last=Bartov |editor-first=Omar |editor2-last=Grossman |editor2-first=Atina |editor3-last=Nolan |editor3-first=Mary |location=New York |publisher=The New Press |year=2002 |page=245 |isbn=978-1-56584-654-8}}</ref> but U.S. officials refused to reconsider.<ref name="TBANGR" />{{rp|261}} | |||

| In 1994, the U.S. Armed Forces Claims Service in Korea dismissed one No Gun Ri petition by asserting that any killings took place during combat.{{cn|date=October 2013}} The survivors' committee retorted that there was no battle at No Gun Ri, and the official U.S. Army history agrees,<ref name="Appleman" />{{rp|203}} but U.S. officials refused to reconsider. In 1997, the survivors and victims filed a claim with a South Korean compensation committee under the binational Status of Forces Agreement. This time, the U.S. claims service responded by again citing what it claimed was a combat situation and saying there was no evidence the ] was at No Gun Ri, as the survivors' research indicated.<ref name="Committee" />{{rp|132,133}} | |||

| In 1997, the survivors filed a claim with a South Korean compensation committee under the binational Status of Forces Agreement. This time, the U.S. claims service responded by again citing what it claimed was a combat situation, and by asserting that there was no evidence the 1st Cavalry Division was in the No Gun Ri area, as the survivors' research indicated (and as the 1961 official U.S. Army history of the war confirms).<ref name="Appleman" />{{rp|179}}<ref name="Williams"/> | |||

| On April 28, 1998, the Seoul government committee made a final ruling against the No Gun Ri survivors, citing the long-ago expiration of a five-year statute of limitations.<ref name="Committee" />{{rp|135}} | |||

| On April 28, 1998, the Seoul government committee made a final ruling against the No Gun Ri survivors, citing the long-ago expiration of a five-year statute of limitations.<ref name="Committee" />{{rp|135}} In June 1998, South Korea's National Council of Churches, on behalf of the No Gun Ri survivors, sought help from the U.S. National Council of Churches, which quietly asked the Pentagon to investigate. In March 1999, the Army told the U.S. council that it had looked into the No Gun Ri allegations, and "found no information to substantiate the claim" in the operational records of the 1st Cavalry Division and other frontline units.<ref name="Committee"/>{{rp|148}}<ref name="TBANGR"/>{{rp|275–76}} | |||

| === Associated Press Story === | |||

| Chung, the leader of the survivors group, published a book in 1994 about the events of 1950. However, it received little attention outside South Korea.<ref name="Committee" />{{rp|128}} In April 1998 The Associated Press reported on the rejection of the survivors' 1997 claim; its reporters had already begun months of investigative work searching for 1st Cavalry Division veterans who were at No Gun Ri.<ref name="TBANGR" />{{rp|269–284}} On Sept. 29, 1999, after a year of AP internal struggle over releasing the article,<ref>{{cite book | last1 = Port | first1 = J. Robert | title = Into the Buzzsaw: Leading Journalists Expose the Myth of a Free Press | chapter = The Story No One Wanted to Hear | editors = Kristina Borjesson | publisher = Prometheus Books | year = 2002 | location = Amherst, New York | pages = 201–213 | isbn = 1-57392-972-7}}</ref> the AP published its investigative report on the incident, based on the accounts of 24 No Gun Ri survivors corroborated by 7th Cavalry Regiment veterans. The journalists' research into declassified archives uncovered recorded instructions in warfront units at the time to shoot South Korean refugees.<ref>Archives are maintained by the ]. For these purposes, mostly at ] facility</ref> A liaison officer of the sister 8th Cavalry Regiment had relayed word to his unit from 1st Cavalry Division headquarters to fire on refugees trying to cross U.S. front lines. Top commanders of the 25th Infantry Division ordered their troops to treat civilians in the war zone as enemy and shoot them.<ref group=nb name=directives/> On the day the No Gun Ri killings began, the Eighth Army ordered<ref>{{cite web|url=http://commons.wikimedia.org/File:No_Gun_Ri_07_-_Eighth_Army_26_July_-_Stop_all_refugees.jpg |title=File:No Gun Ri 07 - Eighth Army 26 July - Stop all refugees.jpg | publisher = Wikimedia Commons |date= |accessdate=2012-08-29}}</ref> all units to stop refugees from crossing their lines.<ref name="AP Original">{{cite news | title = War's hidden chapter: Ex-GIs tell of killing Korean refugees | date = September 29, 1999 | agency = Associated Press}}</ref> The AP reported in subsequent articles that many more South Korea civilians were killed when refugee columns were strafed by U.S. warplanes in the war's first months and when the U.S. military blew up two Naktong River bridges packed with refugees on Aug. 4, 1950.<ref>{{cite news | title = Veterans: Other incidents of refugees killed by GIs during Korea retreat | date = October 13, 1999 | work = The Associated Press}} {{cite news | title = Korean, U.S. witnesses, backed by military records, say refugees strafed | date = December 28, 1999 | work = The Associated Press}}</ref> ] | |||

| === Associated Press story === | |||

| In June 2000, CBS News reported the existence of a U.S. Air Force memo from July 1950, once classified "Secret," in which the operations chief in Korea said the Air Force was strafing refugee columns at the Army's request.<ref>{{cite news | title = Orders To Fire On Civilians? | date = June 6, 2000 | url = http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2000/06/05/korea/main202826.shtml | work = CBS News | accessdate = February 13, 2012}}</ref><ref group=nb>]; Memo from Col. Turner C. Rogers noting the policy of strafing refugees.</ref> A Navy document later emerged in which pilots said the Army had told them to attack any groups of more than eight people in South Korea.<ref name="Routledge">{{cite book | last1 = Hanley | first1 = Charles J. | title = Truth and Reconciliation in South Korea: Between the Present and Future of the Korean Wars | chapter = No Gun Ri: Official Narrative and Inconvenient Truths | editors = Jae-Jung Suh | publisher = Routledge | year = 2012 | location = London and New York | pages = 68–94 | isbn = 978-0-415-62241-7}}</ref>{{rp|81}}<ref group=nb>]</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The AP report came under criticism in May 2000. '']'' reported that one of the key AP witnesses, Edward L. Daily, was not present for the events he described.<ref>{{cite news | title = Doubts About a Korean "Massacre" | date = May 14, 2000 | work = U.S. News & World Report}}</ref>Another of the AP’s sources, Eugene Hesselman, stated that he overheard an order from company commander Captain Melbourne Chandler directing his men to fire on the refugees when it was later discovered that Hesselman had been injured and evacuated before the incident took place. .<ref name="BATEMAN" />{{rp|166}} According to military historian and former 7th Cavalry officer ], he informed the AP team of Daley's deception weeks before their submission to the Pulitzer committee, but the AP team did not disclose this information.<ref>Robert Bateman. ''. ]</ref> Additional sources used by the AP later informed the US Army’s investigators and Bateman that they had been misquoted or their interviews had been taken out of context to support events that did not occur.<ref name="BATEMAN" />{{rp|xii}} A Pentagon spokesman said this would not affect the Army's No Gun Ri investigation, referring to Daily as "just one guy of many we've been talking to".<ref>{{cite news | title = Ex-GI acknowledges records show he couldn't have witnessed killings | date = May 25, 2000 | agency = Associated Press}}</ref> | |||

| Months before the Army's private correspondence with the church group, Associated Press reporters, researching those same 1950 operational records, found orders to shoot South Korean civilians. The U.S.-based news agency, which reported the rejection of the survivors' claim in April 1998, had begun investigating the No Gun Ri allegations earlier that year, trying to identify Army units possibly involved, and to track down their ex-soldiers.<ref name="TBANGR"/>{{rp|269–84}} On September 29, 1999, after a year of internal struggle over releasing the article,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Port |first1=J. Robert |title=Into the Buzzsaw: Leading Journalists Expose the Myth of a Free Press |chapter=The Story No One Wanted to Hear |editor=Kristina Borjesson |publisher=Prometheus Books |year=2002 |location=Amherst, New York |pages= |isbn=978-1-57392-972-1 |chapter-url-access=registration |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/intobuzzsawleadi00br |url=https://archive.org/details/intobuzzsawleadi00br/page/201}}</ref> the AP published its investigative report on the massacre, based on the accounts of 24 No Gun Ri survivors, corroborated by a dozen 7th Cavalry Regiment veterans. "We just annihilated them," it quoted former 7th Cavalry machine gunner Norman Tinkler as saying. The journalists' research into declassified military documents at the U.S. National Archives uncovered recorded instructions in late July 1950 that front-line units shoot South Korean refugees approaching their positions.<ref group=nb name=directives>The directives: | |||

| The No Gun Ri reporting by AP's Sang-hun Choe, Charles J. Hanley, Martha Mendoza and Randy Herschaft was awarded the 2000 ], along with 10 other major national and international journalism awards.<ref name="TBANGR" />{{rp|278}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *]</ref> A liaison officer of the sister ] had relayed word to his unit from 1st Cavalry Division headquarters to fire on refugees trying to cross U.S. front lines. Major General ] of the neighboring ] advised that any civilians found in areas supposed to be cleared by police should be considered enemies and "treated accordingly", an order relayed by his staff as "considered as unfriendly and shot".<ref group=nb name=directives/> On the day the No Gun Ri killings began, the ] ordered all units to stop refugees from crossing their lines.<ref name="AP Original"/><ref group=nb>{{cite web |url=http://commons.wikimedia.org/File:No_Gun_Ri_07_-_Eighth_Army_26_July_-_Stop_all_refugees.jpg |title=File:No Gun Ri 07 - Eighth Army 26 July - Stop all refugees.jpg |publisher=Wikimedia Commons |date=January 13, 2012 |access-date=2012-08-29 |archive-date=October 23, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131023034311/http://commons.wikimedia.org/File:No_Gun_Ri_07_-_Eighth_Army_26_July_-_Stop_all_refugees.jpg |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In subsequent articles, the AP reported that many more South Korean civilians were killed when the U.S. military blew up two ] bridges packed with refugees on August 4, 1950, and when other refugee columns were strafed by U.S. aircraft in the war's first months.<ref>{{cite news |title=Veterans: Other incidents of refugees killed by GIs during Korea retreat |date=October 13, 1999 |agency=Associated Press}} {{cite news |title=Korean, U.S. witnesses, backed by military records, say refugees strafed |date=December 28, 1999 |agency=Associated Press}}</ref> | |||

| The AP team (], ], ] and Randy Herschaft) was awarded the 2000 ] for their reporting on No Gun Ri, along with receiving 10 other major national and international journalism awards.<ref name="TBANGR" />{{rp|278}} | |||

| == Investigations == | |||

| In March 1999, six months before the AP story was published, the U.S. Army said it had looked into the No Gun Ri allegations as a result of a 1998 request from the U.S. ], on behalf of the Korean National Council of Churches. An Army official wrote the U.S. council that researchers reviewed operational records of the 1st Cavalry and 25th Infantry Divisions and "found no information to substantiate the claim". During the earlier 1998 investigation by Associated Press journalists, reviewing the same records at the ], several directives to fire on civilians were found.<ref name="TBANGR" />{{rp|275–276}}<ref group=nb name=directives>The directives: | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ]</ref> | |||

| Expanding on the AP's work, in June 2000, CBS News reported the existence of a ] memo from July 1950, in which the operations chief in Korea said the Air Force was strafing refugee columns approaching U.S. positions.<ref>{{cite news |title=Orders To Fire On Civilians? |date=June 6, 2000 |url=http://www.cbsnews.com/news/orders-to-fire-on-civilians/ |work=CBS News |access-date=February 13, 2012 |archive-date=October 4, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151004230745/http://www.cbsnews.com/news/orders-to-fire-on-civilians/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref group=nb>]; Memo from Col. Turner C. Rogers noting the policy of strafing refugees.</ref> The memo, dated July 25, the day before the No Gun Ri killings began with such a strafing, said the U.S. Army had requested the attacks on civilians, and "to date, we have complied with the army's request".<ref name="TKim">{{cite journal |title=War against an Ambiguous Enemy: U.S. Air Force Bombing of South Korean Civilian Areas, June–September 1950 |journal=Critical Asian Studies |year=2012 |first=Taewoo |last=Kim |volume=44 |issue=2 |page=223 |doi=10.1080/14672715.2012.672825 |s2cid=143224236}}</ref> A U.S. Navy document later emerged in which pilots from the aircraft carrier {{USS|Valley Forge|CV-45|6}} reported that the Army had told them to attack any groups of more than eight people in South Korea.<ref name="Collateral Damage"/>{{rp|93}}<ref group=nb>]</ref> "Most fighter-bomber pilots regarded Korean civilians in white clothes as enemy troops," South Korean scholar Taewoo Kim would later conclude after reviewing Air Force mission reports from 1950.<ref name="TKim"/>{{rp|224}} | |||

| === 1999–2001 investigations === | |||

| Shortly after the publication of the AP report, ] ] ordered ] ] to initiate an official ] investigation. The Seoul government also ordered an investigation, proposing the two inquiries conduct joint document searches and joint witness interviews. The Americans refused.<ref>Cable, U.S. Embassy, Seoul. October 14, 1999. "A/S Roth puts focus on cooperation in Nogun-ri review". Cited in | |||

| {{cite journal | title = No Gun Ri: Official Narrative and Inconvenient Truths | journal = Critical Asian Studies | date = December 2010 | first = Charles J. | last = Hanley | volume = 42 | issue = 4 | page = 592 | id = | url = http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14672715.2010.515389 | accessdate = February 17, 2012 | doi = 10.1080/14672715.2010.515389}}</ref> | |||

| In May 2000, challenged by a skeptical ''U.S. News & World Report'' magazine article,<ref>{{cite news |title=Doubts About a Korean "Massacre" |date=May 14, 2000 |work=U.S. News & World Report}}</ref> the AP team did additional archival research and reported that one of nine ex-soldiers quoted in the original No Gun Ri article, Edward L. Daily, had incorrectly identified himself as an eyewitness, and instead had been passing on second-hand information. A Pentagon spokesman said this would not affect an ongoing Army investigation of No Gun Ri, noting Daily was "just one guy of many we've been talking to".<ref>{{cite news |title=Ex-GI acknowledges records show he couldn't have witnessed killings |date=May 25, 2000 |agency=Associated Press}}</ref> Army officer Robert Bateman, a 7th Cavalry veteran who collaborated on the ''U.S. News & World Report'' article with a fellow 7th Cavalry association member,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Andersen |first1=Robin |title=A Century of Media, A Century of War |location=New York |publisher=Peter Lang |year=2006 |page=44 |isbn=978-0-8204-7894-4 |quote=Only later was it revealed that the attempt to discredit the story came from the military affairs reporter at ''U.S. News & World Report'', Joseph Galloway, a member of the veterans group opposed to the story.}}</ref> later published a book, ],<ref>{{cite web |author=Lucia Anderson |url=http://www.fredericksburg.com/featureslife/book-accuses-ap-journalists-of-sloppy-journalism/article_8e30270b-ace5-54f9-b33a-2645a12e3372.html |title=Book accuses AP journalists of sloppy journalism |work=Fredericksburg.com |date=June 23, 2002 |access-date=August 16, 2015 |archive-date=November 5, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181105221925/https://www.fredericksburg.com/featureslife/book-accuses-ap-journalists-of-sloppy-journalism/article_8e30270b-ace5-54f9-b33a-2645a12e3372.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="SFGate">{{cite web |author=Michael Taylor |url=http://www.sfgate.com/opinion/article/MEDIA-A-War-of-Words-on-a-Prize-Winning-Story-2854723.php |title=A War of Words on a Prize-Winning Story: No Gun Ri authors cross pens on First Amendment battlefield |work=San Francisco Chronicle |date=April 7, 2002 |access-date=August 16, 2015 |archive-date=September 24, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924162957/http://www.sfgate.com/opinion/article/MEDIA-A-War-of-Words-on-a-Prize-Winning-Story-2854723.php |url-status=live }}</ref> repeating his contentions that the AP reporting was flawed. The AP's methods and conclusions were defended by the AP in a lengthy, detailed refutation<ref>{{cite news |last=Schwartz |first=Jerry |url=http://nogunri.rit.albany.edu/omeka/items/show/63 |title=AP responds to questions about prize-winning investigation |agency=Associated Press |date=2000-05-16 |access-date=October 25, 2015 |archive-date=November 17, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151117015615/http://nogunri.rit.albany.edu/omeka/items/show/63 |url-status=live }}</ref> and by others.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.c-span.org/video/?182961-1/debate-gun-ri |title=What really happened at No Gun Ri? |work=Pritzker Military Library |publisher=C-SPAN |date=2004-07-20 |quote=(Moderator John Callaway to Bateman): Why do the project if you can't do it right? ... Why would you do a critical book on this subject if you didn't have the resources to go into the field to do that half of the story? ... Whose account should we pay more attention to, the person who has the resources to go to South Korea and conduct the interviews, or the person who doesn't go to South Korea? |access-date=June 8, 2015 |archive-date=November 17, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151117023952/http://www.c-span.org/video/?182961-1/debate-gun-ri |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=Dobbs |first=Michael |title=War and Remembrance |newspaper=The Washington Post |date=2000-05-21 |quote=Thanks to the doggedness of the AP reporters, and the persistence of the Korean survivors, historians will look at the U.S. Army's conduct in the Korean War in a new light. The AP reporters deserve their Pulitzer Prize.}}</ref> The Pulitzer committee reaffirmed its award and the credibility of the AP reporting.<ref name="Choi"/>{{rp|120}}<ref>{{cite news |last=Barringer |first=Felicity |title=A Press Divided: Disputed Accounts of a Korean War Massacre |work=] |date=2000-05-22}}</ref> | |||

| In the ensuing 15-month probes, conducted by the U.S. Army inspector general's office and Seoul's Defense Ministry, interrogators interviewed or obtained statements from some 200 U.S. veterans and 75 Koreans. The Army researchers reviewed 1 million pages of U.S. archival documents.<ref name="DAIG" />{{rp|i-ii}} The final weeks were marked by Seoul press reports of sharp disputes between the U.S. and Korean teams.<ref name="Committee" />{{rp|168}}<ref>''Dong-a Daily'', Seoul. December 7, 2000. (In Korean).</ref> | |||

| === U.S. and South Korean military investigations === | |||

| On Jan. 11 (U.S. time), 2001, the two governments issued their reports. The US report concluded the U.S. military had killed "an unknown number" of South Korean refugees at No Gun Ri with "small-arms fire, artillery and mortar fire, and strafing that preceded or coincided with the NKPA's advance and the withdrawal of U.S. forces in the vicinity of No Gun Ri during the last week of July 1950" but no orders were issued to fire on the civilians, and the shootings were the result of a perceived enemy threat.<ref name="DAIG" />{{rp|x–xi}} | |||

| ] ] issued a statement on the same day, declaring that “I deeply regret that Korean civilians lost their lives at No Gun Ri in late July, 1950,” but stopping short of an apology acknowledging wrongdoing.<ref>{{Cite news|author=]|date=January 11, 2001|title=US 'deeply regrets' civilian killings|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/1111350.stm|work=]|accessdate=2007-04-15}}</ref><ref>Clinton, William J. 2001. Washington, D.C.: Presidential Papers, Administration of William J. Clinton. 11 January. Retrieved January 14, 2012</ref> The U.S. offered a $4 million plan for a memorial at No Gun Ri and scholarship fund, but not the $400 million the individual compensation survivors demanded.<ref>{{cite news | title = Army says GIs killed South Korean civilians, Clinton expresses regret | date = January 11, 2001 | agency = Associated Press}}</ref> The survivors later rejected the plan because the memorial would be dedicated to all the war's South Korean civilian dead rather than just the No Gun Ri victims.<ref>{{cite news | title = US sticks to 2001 offer for shooting victims | date = August 5, 2005 | work = Yonhap News Agency}}</ref> | |||

| On September 30, 1999, within hours of publication of the AP report, ] ] ordered ] ] to initiate an investigation.<ref>{{cite news |last=Becker |first=Elizabeth |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1999/10/01/world/us-to-revisit-accusations-of-a-massacre-by-gi-s-in-50.html |title=U.S. to Revisit Accusations Of a Massacre By G.I.'s in '50 |work=] |date=1999-10-01 |access-date=February 11, 2017 |archive-date=September 11, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170911113754/http://www.nytimes.com/1999/10/01/world/us-to-revisit-accusations-of-a-massacre-by-gi-s-in-50.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The Seoul government also ordered an investigation, proposing that the two inquiries conduct joint document searches and joint witness interviews. The Americans refused.<ref name="MBC"/><ref>Cable, U.S. Embassy, Seoul. October 14, 1999. "A/S Roth puts focus on cooperation in Nogun-ri review". Cited in {{cite book |last1=Hanley |first1=Charles J. |title=Truth and Reconciliation in South Korea: Between the Present and Future of the Korean Wars |chapter=No Gun Ri: Official Narrative and Inconvenient Truths |editor=Jae-Jung Suh |publisher=Routledge |year=2012 |location=London and New York |page=71 |isbn=978-0-415-62241-7}}</ref> | |||

| South Korean investigators, whilst acknowledging a lack of documentation of specific No Gun Ri orders, referred to testimony from five former Air Force pilots that, during this period, they were directed to strafe civilians, and from 17 veterans of the 7th Cavalry that they believed there were orders to use lethal force to stop refugee movement if warranted. The Koreans noted that two of the veterans were battalion ] and, as such, were in an especially good position to know which orders had been relayed.<ref name="ROK">Ministry of Defense, Republic of Korea. ''The Report of the Findings on the No Gun Ri Incident''. Seoul, South Korea. January 2001.</ref>{{rp|176}}<ref>{{cite news | first = Richard | last = Pyle | title = Ex-GIs: U.S. troops in Korea War had orders to shoot civilians | date = November 21, 2000 | work = The Associated Press}}</ref> Former U.S. congressman ] of California, the only one of eight outside advisers to the U.S. inquiry to write a detailed analysis afterward, agreed with the Koreans. "I don't think there is any question that they were strafing and under orders," he said of U.S. warplanes,<ref name="BBC" /> and "I thought the Army report was a whitewash".<ref name="MBC" /> Korean investigators pointed out gaps in U.S.-supplied documentation, gaps that included the 7th Cavalry's journal, or communications log, for July 1950, the crucial document that would have carried No Gun Ri orders. It was missing from its place at the National Archives.<ref name="Routledge" />{{rp|83}}<ref name="ROK" />{{rp|14}} | |||

| In the ensuing 15-month probes, conducted by the U.S. Army inspector general's office and Seoul's defense ministry, interrogators interviewed or obtained statements from some 200 U.S. veterans and 75 Koreans. The Army researchers reviewed 1 million pages of U.S. archival documents.<ref name="DAIG"/>{{rp|i–ii}} The final weeks were marked by press reports from Seoul of sharp disputes between the U.S. and Korean teams.<ref name="Committee"/>{{rp|168}}<ref>''Dong-a Daily'', Seoul. December 7, 2000. (In Korean).</ref> On January 11, 2001, the two governments issued their separate reports. | |||

| Surviving documents said nothing about infiltrators at No Gun Ri, even though they would have been the 7th Cavalry's first enemy killed-in-action in Korea. However, several of the battalion soldiers interviewed said their unit was returning hostile fire from the tunnels. <ref name="DAIG" />{{rp|120,x}} The Korean survivors said there were no infiltrators in their group, and the South Korean investigative report argued the illogic of trapped infiltrators firing on the surrounding battalion, doubted the scenario.<ref>Kuehl, Dale C. . U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. June 6, 2003. Retrieved February 10, 2012. Biblioscholar (2012). ISBN 1249440270</ref>{{rp|83}} <ref name="Committee" />{{rp|97}} The survivors' committee called the U.S. Army report a "whitewash" of command responsibility.<ref>{{cite news | title = Army confirms G.I.'s in Korea killed civilians | date = January 12, 2001 | url = http://www.nytimes.com/2001/01/12/world/army-confirms-gi-s-in-korea-killed-civilians.html?scp=1&sq=%22army%22+%2B%22korea%22&st=nyt | work = The New York Times | accessdate = February 17, 2012}}</ref> | |||

| === |

==== U.S. report ==== | ||

| Speaking with reporters, Clinton had said, "The evidence was not clear that there was responsibility for wrongdoing high enough in the chain of command in the Army to say that, in effect, the government was responsible."<ref>{{cite news | title = No Gun Ri: Unanswered | date = January 13, 2001 | agency = Associated Press}}</ref> | |||

| After years of dismissing the allegations, the Army acknowledged in its report that the U.S. military had killed "an unknown number" of South Korean refugees at No Gun Ri with "small-arms fire, artillery and mortar fire, and strafing". However, it held that no orders were issued to fire on the civilians, and that the shootings were the result of hostile fire from among the refugees, or was firing meant to control them.<ref name="DAIG" />{{rp|x–xi}} At another point, it suggested that soldiers may have "misunderstood" the Eighth Army's stop-refugees order to mean they could be shot.<ref name="DAIG" />{{rp|185}}<ref name="Collateral Damage"/>{{rp|97}} At the same time, it described the deaths as "an unfortunate tragedy inherent to war and not a deliberate killing".<ref name="DAIG"/>{{rp|x}} The Army report dismissed the testimony of soldiers who spoke of orders to shoot at No Gun Ri because, it said, none could remember the wording, the originating officer's name, or having received the order directly himself.<ref name="DAIG" />{{rp|129}} | |||

| Established international laws of war held governments responsible for their soldiers' acts. "A belligerent party ... shall be responsible for all acts committed by persons forming part of its armed forces," says the ] on the laws of warfare,<ref>Hague Convention. 1907. The Hague, Netherlands. Retrieved February 14, 2012</ref> which the United States declared it would abide by at the Korean War's outbreak, along with the 1949 Geneva Conventions' articles regarding protection of civilians during wartime.<ref name="Committee" />{{rp|113}} In addition, the Hague Convention and the U.S. Army's own contemporaneous ''Rules of Land Warfare'' manual said troops must distinguish noncombatants from belligerents and treat them humanely.<ref>Hague Convention. 1907. The Hague, Netherlands. Retrieved February 14, 2012</ref><ref>{{cite book | last1 = U.S. War Department | title = Rules of Land Warfare | publisher = U.S. Government Printing Office | year = 1940 | location = Washington, D.C. | page = 6}}</ref> "Thus, the United States of America should take responsibility for the No Gun Ri incident," the South Korean government's victims review committee concluded in 2005.<ref name="Committee" />{{rp|119}} Writing to the Army inspector general's office after issuance of its 2001 investigative report, American lawyers for the survivors said that whether the 7th Cavalry troops acted under formal orders or not, "the massacre of civilian refugees, mainly the elderly, women and children, was in and of itself a clear violation of international law for which the United States is liable under the doctrine of command responsibility and must pay compensation".<ref>{{cite book | last1 = Chung | first1 = Koo-do | title = The Issue of Human Rights Violations During the Korean War and Perception of History: Focusing on the No Gun Ri and Other U.S. Military-Related Cases | publisher = Dunam Publishing Co. | year = 2008 | location = Seoul, South Korea | page = 440}}</ref> | |||

| The report questioned an early, unverified South Korean government estimate of 248 killed, missing, and wounded at No Gun Ri, citing an aerial reconnaissance photograph of the area, said to have been taken eight days after the killings ended, that it said showed "no indication of human remains or mass graves".<ref name="DAIG" />{{rp|xiv}} Four years after this 2001 report, the Seoul government's inquest committee certified the identities of a minimum of 218 casualties.<ref name="218 killed"/> | |||

| === Further evidence emerges === | |||

| A joint U.S.-South Korean "statement of mutual understanding" issued with the separate 2001 investigative reports did not include the assertion that no orders to shoot refugees were issued at No Gun Ri. But that remained a central "finding"<ref name="DAIG" />{{rp|xiii}} of the U.S. report itself, which either did not address or presented incomplete versions of key declassified documents previously reported in the news media. In describing the July 1950 Air Force memo,<ref name="wikimedia1" /> the U.S. report did not acknowledge it said refugees were being strafed at the Army's request.<ref name="DAIG" />{{rp|98}} The report did not address the order<ref>{{cite web|url=http://commons.wikimedia.org/File:No_Gun_Ri_12_-_25th_Infantry_Division_26_July_-_Shoot_civilians.jpg |title=File:No Gun Ri 12 - 25th Infantry Division 26 July - Shoot civilians.jpg | publisher = Wikimedia Commons |date= |accessdate=2012-08-29}}</ref> in the 25th Infantry Division to shoot civilians in the war zone.<ref name="DAIG" />{{rp|xiii}} In saying no such orders were issued at No Gun Ri, the Army did not disclose that the 7th Cavalry log, which would have held such orders, was missing from the National Archives. | |||

| ==== South Korean report ==== | |||

| ] | |||

| In their report, South Korean investigators acknowledged that no documents showed specific orders at No Gun Ri to shoot refugees. However, they pointed to gaps in the U.S.-supplied documents dealing with 7th Cavalry and U.S. Air Force operations. Missing documents included the 7th Cavalry's journal, or communications log, for July 1950, the record that would have carried No Gun Ri orders. It was missing without explanation from its place at the National Archives.<ref name="ROK" />{{rp|14}}<ref name="Stanford">{{cite journal |title=No Gun Ri: A Cover-Up Exposed |journal=Stanford Journal of International Law |date=Winter 2002 |first=Martha |last=Mendoza |volume=38 |issue=153 |page=157 |url=http://journals.law.stanford.edu/sjil |access-date=January 6, 2014 |archive-date=February 18, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140218055555/http://journals.law.stanford.edu/sjil |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| After the Army issued its report, it was learned it also had not disclosed its researchers' discovery of at least 14 additional declassified documents showing high-ranking commanders ordering or authorizing the use of lethal force to stop refugees in certain areas in the Korean War's early months. They included communications from 1st Cavalry Division commander Gay and a top division officer to consider refugees north of the firing line "fair game"<ref>{{cite web|url=http://commons.wikimedia.org/File:No_Gun_Ri_17_-_Maj._Gen._Gay_29_August_-_Refugee_are_fair_game.jpg |title=File:No Gun Ri 17 - Maj. Gen. Gay 29 August - Refugee are fair game.jpg | publisher = Wikimedia Commons |date= |accessdate=2012-08-29}}</ref> and to "shoot all refugees coming across river".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://commons.wikimedia.org/File:No_Gun_Ri_15_-_8th_Cavalry_9_August_-_Shoot_all_refugees.jpg |title=File:No Gun Ri 15 - 8th Cavalry 9 August - Shoot all refugees.jpg | publisher = Wikimedia Commons |date= |accessdate=2012-08-29}}</ref> | |||