| Revision as of 13:23, 11 June 2006 editKymeSnake (talk | contribs)127 edits →Slavery in Greece← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:51, 13 January 2025 edit undoBobKilcoyne (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users27,352 edits MOS:BOLDLEAD | ||

| (608 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|none}} <!-- "none" is preferred when the title is sufficiently descriptive; see ] --> | |||

| '''Slavery''' in the '''ancient''' ] cultures comprised a mixture of ], slavery as a punishment for crime, and the enslavement of ]. | |||

| {{More citations needed|date=September 2014}} | |||

| {{slavery}} | |||

| '''] in the ]''', from the earliest known recorded evidence in ] to the pre-medieval ] ] cultures, comprised a mixture of ], slavery as a ] for crime, and the enslavement of ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ditext.com/moral/slavery.html |title=Ancient Slavery |publisher=Ditext.com |access-date=2015-10-18}}</ref> | |||

| Masters could free slaves, and in many cases, such ] went on to rise to positions of ]. This would include those children born into slavery, but who were actually the children of the master of the house. The slave master would ensure that his children were not condemned to a life of slavery.{{Citation needed|date=September 2012}} | |||

| The institution of slavery condemned a majority of ]s to agricultural or industrial labour and they lived hard ]. In some of the city-states of ] and in the ], slaves were a very large part of the economy, and the Roman Empire built a large part of its wealth on slaves acquired through conquest. | |||

| The institution of ] condemned a majority of slaves to agricultural and industrial labor, and they lived hard lives. In many of these cultures, slaves formed a very large part of the economy, and in particular the Roman Empire and some of the ] ] built a large part of their wealth on slaves acquired through conquest. | |||

| Masters could free slaves, and in many cases such ] went on to rise to positions of ]. | |||

| ==Near East== | |||

| ==Slavery in ancient Egypt== | |||

| ]) and Pillia of ] (now Cilicia). Ref:{{British-Museum-db|131447|id=327265}}.]] | |||

| Historians can trace slavery in ] from an early date. Private ownership of slaves, captured in war and given by the king to their captor or otherwise, certainly occurred at the beginning of the ] (1550 - 1295 BCE). Sales of slaves occurred in the ] (732 - 656 BCE), and contracts of servitude survive from the ] (ca 672 - 525 BCE) and from the reign of ]: apparently such a contract then required the consent of the slave. | |||

| {{See also|History of slavery in the Muslim world}} | |||

| ===Sumer=== | |||

| The ] also recounts tales of slavery in Egypt: slave-dealers sold ] into bondage there, and the Hebrews suffered collective enslavement (], chapter 1) prior to ]. | |||

| The ], the oldest known surviving ], written c. 2100 – 2050 BCE, includes laws relating to slaves during the ] in ] ]. It states that a slave that marries cannot be forced to leave the household, and that the bounty for returning a slave who has escaped the city is two ]. <ref>{{cite book |last1=Roth |first1=Martha |title=Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor |pages=13–22}}</ref> It reveals that there were at least two major ]: those free, and those enslaved. | |||

| ===Babylon=== | |||

| ==Slavery in the Bible== | |||

| See ], ], ], in addition to the details of the ]. | |||

| The Babylonian ], written between 1755–1750 BC, also distinguishes between the free and the enslaved. Like the Code of Ur-Nammu, it offers a reward of two shekels for returning a fugitive slave, but unlike the other code, states that harbouring or assisting a fugitive was punishable by death. Slaves were either bought abroad, taken as prisoners in war, or enslaved as a punishment for being in debt or committing a crime. The Code of Hammurabi states that if a slave is purchased and within one month develops ] ("benu-disease") then the purchaser can return the slave and receive a full refund. The code has laws relating to the purchase of slaves abroad. Numerous contracts for the sale of slaves survive.<ref>{{cite web |title=A Collection of Contracts from Mesopotamia, c. 2300 - 428 BCE |url=https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/ancient/mesopotamia-contracts.asp}}</ref> The final law in the Code of Hammurabi states that if a slave denies his master, then his ear will be cut off.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Johns |first1=Claude Hermann Walter |title=BABYLONIAN LAW — The Code of Hammurabi |url=https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/ancient/hamcode.asp#:~:text=Claude%20Hermann%20Walter%20Johns%3A |publisher=Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=King |first1=L. W. |title=HAMMURABI'S CODE OF LAWS |url=https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/ancient/hamcode.asp#:~:text=HAMMURABI%27S%20CODE%20OF%20LAWS}}</ref> | |||

| ===] or ]=== | |||

| ] draws a distinction between Hebrew ]: | |||

| ===Hittites=== | |||

| :25:39 If your brother becomes impoverished with regard to you so that he sells himself to you, you must not subject him to slave service. | |||

| :25:40 He must be with you as a hired worker, as a resident foreigner; he must serve with you until the year of jubilee, | |||

| :25:41 but then he may go free, he and his children with him, and may return to his family and to the property of his ancestors. | |||

| :25:42 Since they are my servants whom I brought out from the land of Egypt, they must not be sold in a slave sale. | |||

| :25:43 You must not rule over him harshly, but you must fear your God. | |||

| ] texts from Anatolia include laws regulating the institution of slavery. Of particular interest is a law stipulating that reward for the capture of an escaped slave would be higher if the slave had already succeeded in crossing the ] and getting farther away from the center of Hittite civilization — from which it can be concluded that at least some of the slaves kept by the Hittites possessed a realistic chance of escaping and regaining their freedom, possibly by finding refuge with other kingdoms or ethnic groups. | |||

| and "bondslaves", foreigners: | |||

| ===In the Bible=== | |||

| :25:44 As for your male and female slaves who may belong to you, you may buy male and female slaves from the nations all around you. | |||

| {{Main|The Bible and slavery}} | |||

| :25:45 Also you may buy slaves from the children of the foreigners who reside with you, and from their families that are with you, whom they have fathered in your land, they may become your property. | |||

| {{Also|Jewish views on slavery|Christian views on slavery}} | |||

| :25:46 You may give them as inheritance to your children after you to possess as property. You may enslave them perpetually. However, as for your brothers the Israelites, no man may rule over his brother harshly. | |||

| {{Religious text primary|section|date=September 2019}} | |||

| In the ] (the ]), there are many references to slaves, including rules of how they should behave and be treated. Slavery is viewed as routine, as an ordinary part of society. During ], slaves were to be released, according to the ].<ref>{{bibleref|Leviticus|25:8–13}}</ref> ] slaves were also to be released during their seventh year of service, according to the ].<ref>{{bibleref|Deuteronomy|15:12}}</ref> Non-Hebrew slaves and their offspring were the perpetual property of the owner's family,<ref>{{bibleref|Leviticus|25:44-47}}</ref> with limited exceptions.<ref>{{bibleref|Exodus|21:26-27}}</ref> The ] ({{bibleref|Genesis|9:18-27}}) is an important passage related to slavery. It has been noted that the slavery in the Bible differs greatly from Roman and modern slavery in that slaves mentioned in the Old Testament received sexual protection and enough food, and were not chained, tortured or physically abused.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Williams |first1=Peter J. |title=Does the Bible Support Slavery? |url=https://www.bethinking.org/bible/does-the-bible-support-slavery |website=Be Thinking |date=21 December 2015 |access-date=7 July 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ==Slavery in Greece== | |||

| {{main|Slavery in ancient Greece}} | |||

| ], ].]] | |||

| In the ], slaves are told to obey their owners, who are in turn told to "stop threatening" their slaves.<ref>{{bibleref||Ephesians|6:5-9}}</ref><ref>{{bibleref|1 Timothy|6:1}}</ref> The ] has many implications related to slavery. | |||

| Most ]s of ] defended slavery — ''douleia'' (the idea that not everyone should have voting rights and that some people should be forced to obey masters) as a natural and necessary institution; ] believed that the practice of any manual or ] job should be disqualifying for citizenship. Quoting Euripedes<!--Iph.Aul. 1400-->, Aristotle declared all non Greeks to be slaves by birth fit for nothing but obedience. | |||

| ==Egypt== | |||

| Some other philosophers, especially in ], opposed slavery and believed that every person who lives in a city-state has the right to be free and to be subject to no one, except only to laws that are decided using ]. ], for example, said "God has set everyone free. No one is created doulos by nature." A fragment of a poem of ] also shows that he opposed slavery-douleia. | |||

| {{main|Slavery in ancient Egypt}} | |||

| ]. ], Turin.]] | |||

| In ], slaves were mainly obtained through prisoners of war. Other ways people could become slaves was by inheriting the status from their parents. One could also become a slave on account of his inability to pay his debts. Slavery was the direct result of poverty. People also sold themselves into slavery because they were poor peasants and needed food and shelter. Slaves only attempted escape when their treatment was unusually harsh. For many, being a slave in Egypt made them better off than a freeman elsewhere.<ref name="touregypt1">{{cite web|url=http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/slaves.htm |title=Slaves and Slavery in Ancient Egypt |publisher=Touregypt.net |date=2011-10-24 |access-date=2015-10-18}}</ref> Young slaves could not be put to hard work and had to be brought up by the mistress of the household. Not all slaves went to houses. Some also sold themselves to temples or were assigned to temples by the king. Slave trading was not very popular until later in Ancient Egypt. But while slave trading eventually sprang up all over Egypt, there was little worldwide trade. Rather, the individual dealers seem to have approached their customers personally.<ref name="touregypt1" /> | |||

| Only slaves with special traits were traded worldwide. Prices of slaves changed with time. Slaves with a special skill were more valuable than those without one. Slaves had plenty of jobs that they could be assigned to. Some had domestic jobs, like taking care of children, cooking, brewing, or cleaning. Some were gardeners or field hands in stables. They could be craftsmen or even get a higher status. For example, if they could write, they could become a manager of the master's estate. Captive slaves were mostly assigned to the temples or a king, and they had to do manual labor. The worst thing that could happen to a slave was being assigned to the quarries and mines. Private ownership of slaves, captured in war and given by the king to their captor, certainly occurred at the beginning of the ] (1550–1295 BCE). Sales of slaves occurred in the ] (732–656 BCE), and contracts of servitude survive from the ] (c. 672 – 525 BCE) and from the reign of ]: apparently such a contract then required the consent of the slave. | |||

| Greece consisted of many independent ], each with its own laws. All of them permitted slavery, but the rules differed greatly from region to region. | |||

| ==Greece== | |||

| ] slaves had some chance of escape, as they could become suppliants in ]s and change their masters in case of maltreatment. In Athens, in case a maltreated slave become suppliant in a temple, his master was forced by law to sell him to another master. This law protected slaves, though a slave's master had the right to beat him at will. And a slave's testimony would be taken under torture - fear of the fact that a trusty slave may protect his masters secrets or fear of his master might otherwise make him lie, which reveals the kind of relation slaves had with their masters. <!--'''OCD'' ''s.v.''' sources include Dem 22.55; Ar. Rh. I, 15 ''et permulti alii''--> | |||

| {{main|Slavery in ancient Greece}} | |||

| The study of slavery in Ancient Greece remains a complex subject, in part because of the many different levels of servility, from traditional ] through various forms of ], such as ], ], and several other classes of non-citizens. | |||

| The system in ] encouraged slaves to save for their freedom, and there are records of slaves operating businesses by themselves, with only a fixed tax payment to their masters. There was also a law in Athens, forbidding the striking of slaves— if a person struck someone who seemed to be a slave at Athens, the person might be hitting a fellow citizen, because many citizens dressed no better. Other Greeks were startled by the fact that Athenians tolerated back-chat from slaves (). We are told, from nearly seven centuries afterward, that Athenian slaves fought together with Athenian freemen in the ], and there is a separate battle-monument for the slaves and allies, , or possibly they fought in another battle a little before. Also ] mentions that, during the ], Athenians were doing their best to save their "women, children and slaves." | |||

| Most ]s of ] defended slavery as a natural and necessary institution.<ref>{{cite book|title=]|author=G.E.M. de Ste. Croix|author-link=G.E.M. de Ste. Croix|pages= 409 ff. – Ch. VII, § ii ''The Theory of Natural Slavery''}}</ref> ] believed that the practice of any manual or ] job should disqualify the practitioner from citizenship. Quoting ]<!--Iph.Aul. 1400-->, Aristotle declared all non-Greeks slaves by birth, fit for nothing but obedience. | |||

| On the other hand, much of the wealth of ] came from its ]-] at ], and slaves, working in extremely poor conditions, produced the greatest part of the silver (although recent excavations seem to suggest the presence of free workers at Laureion). During the war between Athens and Sparta, twenty thousand Athenian slaves, including both mine-workers and artisans, escaped to the Spartans when their army camped at ] in ]. | |||

| By the late 4th century BCE passages start to appear from other Greeks, especially in ], which opposed slavery and suggested that every person living in a city-state had the right to freedom subject to no one, except those laws decided using ]. ], for example, said: "God has set everyone free. No one is made a slave by nature." Furthermore, a fragment of a poem of ] also shows that he opposed slavery. | |||

| Other than flight, resistance on the part of slaves occurred only rarely (e.x. in Sparta). ] gives two reasons. First they came from various regions and spoke various languages (similar to the contemporary multicultural states or cities). Second that a slave holder could rely on the support of fellow slaverholders if his slaves offered resistance. Finnaly another possible reason, not mentioned by Croix, is that each slave belonged to a different master so their treatment varied according to their master will. Slaves had no common goals in order to revolt and some slaves were treated well but their master. So the majority of slaves, except for the fact that they could not decide about the laws of their city state, they had no other reason to revolt. | |||

| ] | |||

| Athens had many classes of slave in Athens: | |||

| Greece in pre-Roman times consisted of many independent ]s, each with its own laws. All of them permitted slavery, but the rules differed greatly from region to region. ] slaves had some opportunities for emancipation, though all of these came at some cost to their masters. The law protected slaves, and though a slave's master had the right to beat him at will, a number of moral and cultural limitations existed on excessive use of force by masters. <!-- sources include Dem 22.55; Ar. Rh. I, 15 ''et permulti alii''--> | |||

| * House slaves, living in their master's home and working at home, on the land or in a shop. | |||

| * Freelance slaves, who didn't live with their master but worked in their master's shop or fields and paid him taxes from money they got from their own properties (as long as property was allowed to be owned by slaves). | |||

| * Public slaves, who worked as police-officers, ushers, secretaries, street-sweepers, etc. | |||

| * War-captives (''andrapoda'') who were primarily used in unskilled labor at which they could be chained: for example, rowers in commercial ships or miners. (Excavations may suggest that free persons also worked in the mines of ].) The miners' work was very hard and their living conditions very bad. | |||

| In ancient ], about 10-30% of the population were slaves.<ref name="Hopkins1981">{{cite book|last=Hopkins|first=Keith|author-link=Keith Hopkins|title=Conquerors and Slaves|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qEr4WFgOz5UC&pg=PA101|date=31 January 1981|publisher=]|location=]|isbn=978-0-521-28181-2|page=101}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Confronting Slavery in the Classical World {{!}} Emory {{!}} Michael C. Carlos Museum |url=https://carlos.emory.edu/exhibition/confronting-slavery-classical-world#:~:text=Estimates%20suggest%20that%20in%20Athens,25%20percent%20of%20the%20population. |access-date=2023-07-15 |website=carlos.emory.edu}}</ref> The system in ] encouraged slaves to save up to purchase their freedom, and records survive of slaves operating businesses by themselves, making only a fixed tax-payment to their masters.{{Citation needed|date=August 2012}} Athens also had a law forbidding the striking of slaves—if a person struck an apparent slave in Athens, that person might find himself hitting a fellow-citizen, because many citizens dressed no better. It startled other Greeks that Athenians tolerated back-chat from slaves (). ] (writing nearly seven centuries after the event) states that Athenian slaves fought together with Athenian freemen in the ], and the monuments memorialize them.<ref>{{cite book |translator=Jones, W.H.S. |translator2=H.A. Ormerod |author=Pausanias |title=Description of Greece|publisher=William Heinemann Ltd.|location=London|year=1918|isbn=0-674-99328-4|oclc=10818363|url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Paus.+1.29.1}}</ref> Spartan serfs, ], could win freedom through bravery in battle. ] mentions that during the ] Athenians did their best to save their "women, children and slaves". | |||

| The comedies of ] show how the Athenians preferred to view a house slave: as an enterprising and unscrupulous rascal, who must use his wits to profit from his master, rescue him from his troubles, or gain him the girl of his dreams. We have most of these plays in translations by ] and ], suggesting that the Romans liked the same genre. And the same sort of genre has not yet decome extinct, as the popularity of ] and '']'' attest. | |||

| On the other hand, much of the wealth of ] came from its ] at ], where slaves, working in extremely poor conditions, produced the greatest part of the silver (although recent excavations seem to suggest the presence of free workers at Laurion).{{Citation needed|date=August 2012}} During the ] between Athens and Sparta, twenty thousand Athenian slaves, including both mine-workers and artisans, escaped to the Spartans when their army camped at ] in 413 BC.{{Citation needed|date=August 2012}} | |||

| ===Helots and ''penestae''=== | |||

| In some areas of Greece, like ] and ], there existed a class of unfree laborers tied to the land and called '']'' or ]s respectively. (The Spartan ] were free non-citizens, as in the example below.) These were not ]s; they could not be bought and sold freely. ] has argued that helots and similar groups had a major advantage over other slaves because they could not be sold at will by their masters. This stability left them free to form family life without the fear that they might be divided one from another by being sold separately. That helots and similar groups were in a kind of half way position between chattel slave and free is fairly uncontroversial. ] takes issue with those who choose to give this intermediate status the label ]. Partly, this is because he gives greater emphasis on the many graduations amongst unfree laborers in the Ancient world. His prime objection, however, is that for him ''serf'' is a precise term, and serfs can only exist under feudal obligations. M I Finley had in his sights certain Marxist historians, especially Soviet,who, committed to ], attempted to show that ancient society passed through the same economic, and consequently social, forms as medieval and modern Europe. Geoffrey de Ste. Croix, though also a Marxist, is in agreement with Finley that to regard Sparta as having been a feudal society is absurd. For him serfdom was a form of unfree labor where that laborer is bound to the land and has to render fixed services, irrespective of to whom those services are owed. | |||

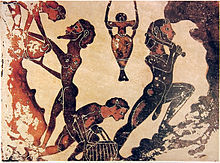

| ], 500-470 BC]] | |||

| Michael Grant takes a middle position saying that such groups between slave and free could be loosely “if somewhat anachronistically” called serfs. (Michael Grant,The Classical Greeks p284) Helots were assigned to individual Spartans but were not owned by them. The helots were obliged to surrender a proportion of the harvest to their master as tribute but were then free to keep the remainder themselves. Similar groups existed in Argos, Crete, Syracuse, Thessaly and other places. (Michael Grant p284) | |||

| Other than flight, resistance on the part of slaves occurred only rarely. ] gives two reasons: | |||

| # slaves came from various regions and spoke various languages | |||

| # a slave-holder could rely on the support of fellow slave-holders if his slaves offered resistance. | |||

| Athens had various categories of slave, such as: | |||

| Sparta, in particular, treated her slaves very harshly. Stories survive of how the Spartans blooded their young men by having them go out and kill some helots. Helots were compelled to get drunk, to demonstrate the ill consequences of drunkenness; and any Spartan might beat any helot at whim. The Spartans did take ''perioikoi'' (and in some cases helots) with them to war, where they usually had light arms; and freed the helots afterwards - especially during the difficult parts of the ]s. After the peace, however, some thousands of these ] disappeared one night, and were never heard from again. | |||

| * ], living in their master's home and working at home, on the land or in a shop. | |||

| * Freelance slaves, who didn't live with their master but worked in their master's shop or fields and paid him taxes from money they got from their own properties (insofar as society allowed slaves to own property). | |||

| Some commentators account for Spartan severity by emphasizing their constant fear of an organized rebellion of the Helots, and at least one such rebellion actually occurred in ]. Ste. Croix explained this fear from the helots largely having a common culture and language and hence being more able to take joint action than chattel slaves. Both the explanation and the underlying conjecture are controversial. M I Finley explains the greater rebelliousness of helots to rebel compared with chattel slaves by the fact that the helots being half free wanted more. | |||

| * Public slaves, who worked as police-officers, ushers, secretaries, street-sweepers, etc. | |||

| * War-captives (''andrapoda'') who served primarily in unskilled tasks at which they could be chained: for example, rowers in commercial ships, or miners. | |||

| ==Slavery in Rome== | |||

| According to the Roman law, "slaves had no head in the State, no name, no title, no register"; they had no rights of matrimony, and no protection against adultery; they could be bought and sold, or given away, as personal property; they might be tortured for evidence, or even put to death, at the discretion of their master."{{fact}} ] expelled his old and sick slaves out of house and home. ], one of the most humane of the ], wilfully destroyed the eye of one of his slaves with a ]. Roman ladies punished their maids with sharp iron instruments for the most trifling offences. A proverb prevailed in the Roman empire: "As many enemies as slaves." Hence the constant danger of servile insurrections, which more than once brought the republic to the brink of ruin, and seemed to justify the severest measures in self-defence — including the law of collective responsibility: if a slave killed his master, the authorities put all of the slaves in the household to death. | |||

| Estimates for the prevelance of slavery in the Roman Empire vary. Some estimate that the slave population in the 1st century consisted of approximately one-third of the total. The Roman economy was certainly heavily dependent on slavery, but was not (as is sometimes mistakenly stated) the most slave-dependent culture in the history of the world. That distiction probably belongs to the Spartans, with helots (the Spartan term for slave) outnumbering the Spartans around seven to one (]; book IX, 10). While we have from Herodotus an ancient source to place Spartan slavery at 7:1, few cite a similar source for the Roman 1:2 so it should be viewed as less reliable. A high proportion of the populations in Italy, what is today Tunisia, southern Spain and western Anatolia was slave. The actual proportion may have been less than 20% for the whole Empire, 12 million people, but we cannot be sure. Since there was a labor shortage in the Roman Empire, there was a constant need to find slaves to tie down the labor supply in various regions of the Empire. In the Later Empire emperors tried to tie people into hereditary occupations to secure vital services as the supply of slaves dried up. | |||

| In Republican Rome, the law recognised slaves as a ], and some authors found in their condition the earliest concept of ], given that the only property they were allowed to own was the gift of reproduction. Slaves lived then within this class with very little hope of a better life, and they were owned and exchanged, just like goods, by free men. They had a price as "human instruments"; their life had not, and their patron could freely even kill them. | |||

| Most of the ]s came from the ranks of the slaves. One of them, ], formed an army of slaves that battled the Roman armies in the ] for several years. | |||

| Augustus punished a wealthy Roman, one ], for feeding clumsy slaves to his eels; and under the ] laws restricting the power of masters over their slaves and children came into force and were steadily extended; however, we cannot know how well-enforced these were. ] ruled that if a master abandoned an old or sick slave, the slave became free. Under ], slaves were given the right to complain against their masters in court. Under ], a slave could claim his freedom if treated cruelly, and a master who killed his slave without just cause could be tried for ]. At the same time, it became more difficult for a person to fall into slavery under Roman law. By the time of ], free men could not sell their children or even themselves into slavery and creditors could not claim insolvent debtors as slaves. | |||

| In some areas of Greece there existed a class of unfree laborers tied to the land and called '']'' in ] and ]s in ]. Penestae and helots did not rate as ]s; one could not freely buy and sell them. | |||

| Freedmen and freedwomen, called '']'', formed a separate class in Roman society at all periods. They had the ] as their symbol. These people were not numerous, but Rome needed to demonstrate at times the great frank spirit of this "civitas," so the freed slaves were made famous, as hopeful examples. Freed people suffered some minor legal disabilities that show in fact how otherwise open the society was to them—they could not hold certain high offices and they could not marry into the ] classes. They might grow rich and influential, but were still looked down on by free-born Romans as vulgar '']'', like ]. Their children had no prohibitions. | |||

| The comedies of ] show how the Athenians preferred to view a ]: as an enterprising and unscrupulous rascal, who must use his wits to profit from his master, rescue him from his troubles, or gain him the girl of his dreams. These plots were adapted by the Roman playwrights ] and ], and in the modern era influenced the character ] and '']''. | |||

| The Latin poet ], the son of a freedman, served as a military officer in the army of ] and seemed headed for a political career before the defeat of Brutus by ] and ]. Though Horace may have been an exceptional case, freedmen were an important part of Roman administrative functions. Freedmen of the Imperial families often were the main functionaries in the Imperial administration. Some rose to positions of great power and influence, for example ], a freedman of the Emperor ]. | |||

| ==Rome== | |||

| Many historians credit this improvement to the influence of ] and of ]. The Stoics taught that all men were manifestations of the same universal spirit, and thus by nature equal. At the same time, however, Stoicism held that external circumstances (such as being enslaved) did not truly impede a person from practicing the Stoic ideal of inner self-mastery: one of the more important Roman stoics, ], spent his youth as a slave. | |||

| {{Main|Slavery in ancient Rome}} | |||

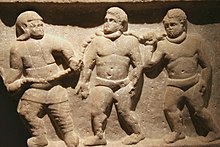

| ] (present-day ], Turkey) depicting a Roman soldier leading captives in chains|alt=]] | |||

| Rome differed from ] in allowing freed slaves to become ]. After ], a slave who had belonged to a citizen enjoyed not only passive freedom from ownership, but active political freedom (''libertas''), including the right to vote, though he could not run for public office.<ref>], ''The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic'' (University of Michigan, 1998, 2002), pp. 23, 209.</ref> During the ], Roman military expansion was a major source of slaves. Besides manual labor, slaves performed many domestic services, and might be employed at highly skilled jobs and professions. Teachers, accountants, and physicians were often slaves. Greek slaves in particular might be highly educated. Unskilled slaves, or those condemned to slavery as punishment, worked on farms, in mines, and at mills. | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| Both the Stoics and the early ] opposed the ill-treatment of slaves, rather than slavery itself. ] argues, indeed, that the influence of such texts as "obey your masters...with fear and trembling" may have made beatings ''more'' common in ]. Many Christian leaders (such as ] and ]) often called for good treatment for slaves and condemned slavery. In fact, tradition describes ] (term c. ] - ]), ] (term c. ] - ]) and ] (term c. ] - ]) as former slaves. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{1911}} | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 09:51, 13 January 2025

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Slavery in antiquity" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (September 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Slavery in the ancient world, from the earliest known recorded evidence in Sumer to the pre-medieval Antiquity Mediterranean cultures, comprised a mixture of debt-slavery, slavery as a punishment for crime, and the enslavement of prisoners of war.

Masters could free slaves, and in many cases, such freedmen went on to rise to positions of power. This would include those children born into slavery, but who were actually the children of the master of the house. The slave master would ensure that his children were not condemned to a life of slavery.

The institution of slavery condemned a majority of slaves to agricultural and industrial labor, and they lived hard lives. In many of these cultures, slaves formed a very large part of the economy, and in particular the Roman Empire and some of the Greek poleis built a large part of their wealth on slaves acquired through conquest.

Near East

Sumer

The Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest known surviving law code, written c. 2100 – 2050 BCE, includes laws relating to slaves during the Third Dynasty of Ur in Sumerian Mesopotamia. It states that a slave that marries cannot be forced to leave the household, and that the bounty for returning a slave who has escaped the city is two shekels. It reveals that there were at least two major social strata at the time: those free, and those enslaved.

Babylon

The Babylonian Code of Hammurabi, written between 1755–1750 BC, also distinguishes between the free and the enslaved. Like the Code of Ur-Nammu, it offers a reward of two shekels for returning a fugitive slave, but unlike the other code, states that harbouring or assisting a fugitive was punishable by death. Slaves were either bought abroad, taken as prisoners in war, or enslaved as a punishment for being in debt or committing a crime. The Code of Hammurabi states that if a slave is purchased and within one month develops epilepsy ("benu-disease") then the purchaser can return the slave and receive a full refund. The code has laws relating to the purchase of slaves abroad. Numerous contracts for the sale of slaves survive. The final law in the Code of Hammurabi states that if a slave denies his master, then his ear will be cut off.

Hittites

Hittite texts from Anatolia include laws regulating the institution of slavery. Of particular interest is a law stipulating that reward for the capture of an escaped slave would be higher if the slave had already succeeded in crossing the Halys River and getting farther away from the center of Hittite civilization — from which it can be concluded that at least some of the slaves kept by the Hittites possessed a realistic chance of escaping and regaining their freedom, possibly by finding refuge with other kingdoms or ethnic groups.

In the Bible

Main article: The Bible and slavery See also: Jewish views on slavery and Christian views on slavery| This section uses texts from within a religion or faith system without referring to secondary sources that critically analyze them. Please help improve this article. (September 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In the Hebrew Bible (the Old Testament), there are many references to slaves, including rules of how they should behave and be treated. Slavery is viewed as routine, as an ordinary part of society. During jubilees, slaves were to be released, according to the Book of Leviticus. Israelite slaves were also to be released during their seventh year of service, according to the Deuteronomic Code. Non-Hebrew slaves and their offspring were the perpetual property of the owner's family, with limited exceptions. The Curse of Ham (Genesis 9:18–27) is an important passage related to slavery. It has been noted that the slavery in the Bible differs greatly from Roman and modern slavery in that slaves mentioned in the Old Testament received sexual protection and enough food, and were not chained, tortured or physically abused.

In the New Testament, slaves are told to obey their owners, who are in turn told to "stop threatening" their slaves. The Epistle to Philemon has many implications related to slavery.

Egypt

Main article: Slavery in ancient Egypt

In Ancient Egypt, slaves were mainly obtained through prisoners of war. Other ways people could become slaves was by inheriting the status from their parents. One could also become a slave on account of his inability to pay his debts. Slavery was the direct result of poverty. People also sold themselves into slavery because they were poor peasants and needed food and shelter. Slaves only attempted escape when their treatment was unusually harsh. For many, being a slave in Egypt made them better off than a freeman elsewhere. Young slaves could not be put to hard work and had to be brought up by the mistress of the household. Not all slaves went to houses. Some also sold themselves to temples or were assigned to temples by the king. Slave trading was not very popular until later in Ancient Egypt. But while slave trading eventually sprang up all over Egypt, there was little worldwide trade. Rather, the individual dealers seem to have approached their customers personally.

Only slaves with special traits were traded worldwide. Prices of slaves changed with time. Slaves with a special skill were more valuable than those without one. Slaves had plenty of jobs that they could be assigned to. Some had domestic jobs, like taking care of children, cooking, brewing, or cleaning. Some were gardeners or field hands in stables. They could be craftsmen or even get a higher status. For example, if they could write, they could become a manager of the master's estate. Captive slaves were mostly assigned to the temples or a king, and they had to do manual labor. The worst thing that could happen to a slave was being assigned to the quarries and mines. Private ownership of slaves, captured in war and given by the king to their captor, certainly occurred at the beginning of the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550–1295 BCE). Sales of slaves occurred in the Twenty-fifth Dynasty (732–656 BCE), and contracts of servitude survive from the Twenty-sixth Dynasty (c. 672 – 525 BCE) and from the reign of Darius: apparently such a contract then required the consent of the slave.

Greece

Main article: Slavery in ancient GreeceThe study of slavery in Ancient Greece remains a complex subject, in part because of the many different levels of servility, from traditional chattel slave through various forms of serfdom, such as helots, penestai, and several other classes of non-citizens.

Most philosophers of classical antiquity defended slavery as a natural and necessary institution. Aristotle believed that the practice of any manual or banausic job should disqualify the practitioner from citizenship. Quoting Euripides, Aristotle declared all non-Greeks slaves by birth, fit for nothing but obedience.

By the late 4th century BCE passages start to appear from other Greeks, especially in Athens, which opposed slavery and suggested that every person living in a city-state had the right to freedom subject to no one, except those laws decided using majoritarianism. Alcidamas, for example, said: "God has set everyone free. No one is made a slave by nature." Furthermore, a fragment of a poem of Philemon also shows that he opposed slavery.

Greece in pre-Roman times consisted of many independent city-states, each with its own laws. All of them permitted slavery, but the rules differed greatly from region to region. Greek slaves had some opportunities for emancipation, though all of these came at some cost to their masters. The law protected slaves, and though a slave's master had the right to beat him at will, a number of moral and cultural limitations existed on excessive use of force by masters.

In ancient Athens, about 10-30% of the population were slaves. The system in Athens encouraged slaves to save up to purchase their freedom, and records survive of slaves operating businesses by themselves, making only a fixed tax-payment to their masters. Athens also had a law forbidding the striking of slaves—if a person struck an apparent slave in Athens, that person might find himself hitting a fellow-citizen, because many citizens dressed no better. It startled other Greeks that Athenians tolerated back-chat from slaves (Old Oligarch, Constitution of the Athenians). Pausanias (writing nearly seven centuries after the event) states that Athenian slaves fought together with Athenian freemen in the Battle of Marathon, and the monuments memorialize them. Spartan serfs, Helots, could win freedom through bravery in battle. Plutarch mentions that during the Battle of Salamis Athenians did their best to save their "women, children and slaves".

On the other hand, much of the wealth of Athens came from its silver mines at Laurion, where slaves, working in extremely poor conditions, produced the greatest part of the silver (although recent excavations seem to suggest the presence of free workers at Laurion). During the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta, twenty thousand Athenian slaves, including both mine-workers and artisans, escaped to the Spartans when their army camped at Decelea in 413 BC.

Other than flight, resistance on the part of slaves occurred only rarely. GEM de Ste. Croix gives two reasons:

- slaves came from various regions and spoke various languages

- a slave-holder could rely on the support of fellow slave-holders if his slaves offered resistance.

Athens had various categories of slave, such as:

- House-slaves, living in their master's home and working at home, on the land or in a shop.

- Freelance slaves, who didn't live with their master but worked in their master's shop or fields and paid him taxes from money they got from their own properties (insofar as society allowed slaves to own property).

- Public slaves, who worked as police-officers, ushers, secretaries, street-sweepers, etc.

- War-captives (andrapoda) who served primarily in unskilled tasks at which they could be chained: for example, rowers in commercial ships, or miners.

In some areas of Greece there existed a class of unfree laborers tied to the land and called penestae in Thessaly and helots in Sparta. Penestae and helots did not rate as chattel slaves; one could not freely buy and sell them.

The comedies of Menander show how the Athenians preferred to view a house-slave: as an enterprising and unscrupulous rascal, who must use his wits to profit from his master, rescue him from his troubles, or gain him the girl of his dreams. These plots were adapted by the Roman playwrights Plautus and Terence, and in the modern era influenced the character Jeeves and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.

Rome

Main article: Slavery in ancient Rome

Rome differed from Greek city-states in allowing freed slaves to become Roman citizens. After manumission, a slave who had belonged to a citizen enjoyed not only passive freedom from ownership, but active political freedom (libertas), including the right to vote, though he could not run for public office. During the Republic, Roman military expansion was a major source of slaves. Besides manual labor, slaves performed many domestic services, and might be employed at highly skilled jobs and professions. Teachers, accountants, and physicians were often slaves. Greek slaves in particular might be highly educated. Unskilled slaves, or those condemned to slavery as punishment, worked on farms, in mines, and at mills.

See also

- History of slavery

- Slavery in ancient Babylon

- Slavery in ancient Egypt

- Slavery in ancient Greece

- Slavery in ancient Rome

- Black Sea slave trade

- Red Sea slave trade

- Trans-Saharan slave trade

- Bukhara slave trade

References

- "Ancient Slavery". Ditext.com. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- Roth, Martha. Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. pp. 13–22.

- "A Collection of Contracts from Mesopotamia, c. 2300 - 428 BCE".

- Johns, Claude Hermann Walter. "BABYLONIAN LAW — The Code of Hammurabi". Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911.

- King, L. W. "HAMMURABI'S CODE OF LAWS".

- Leviticus 25:8–13

- Deuteronomy 15:12

- Leviticus 25:44–47

- Exodus 21:26–27

- Williams, Peter J. (21 December 2015). "Does the Bible Support Slavery?". Be Thinking. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- Ephesians 6:5–9

- 1 Timothy 6:1

- ^ "Slaves and Slavery in Ancient Egypt". Touregypt.net. 2011-10-24. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- G.E.M. de Ste. Croix. The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World. pp. 409 ff. – Ch. VII, § ii The Theory of Natural Slavery.

- Hopkins, Keith (31 January 1981). Conquerors and Slaves. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-521-28181-2.

- "Confronting Slavery in the Classical World | Emory | Michael C. Carlos Museum". carlos.emory.edu. Retrieved 2023-07-15.

- Pausanias (1918). Description of Greece. Translated by Jones, W.H.S.; H.A. Ormerod. London: William Heinemann Ltd. ISBN 0-674-99328-4. OCLC 10818363.

- Fergus Millar, The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic (University of Michigan, 1998, 2002), pp. 23, 209.