| Revision as of 07:02, 4 December 2013 view sourceCmguy777 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users51,052 edits Undid revision 584486628 by Cmguy777 (talk)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:34, 5 January 2025 view source Bruce leverett (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users5,799 edits Short description is too long, see explanation on talk page.Tag: Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Civil War general, U.S. president (1869 to 1877)}} | |||

| {{About|the president of the United States|others with the same name|Ulysses S. Grant (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Redirect-several|dab=off|text=|General Grant (disambiguation)|President Grant (disambiguation)|Ulysses S. Grant (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Redirect|General Grant}} | |||

| {{Featured article}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=April 2011}} | |||

| {{ |

{{Pp|small=yes}} | ||

| {{ |

{{Pp-move}} | ||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=October 2024}} | |||

| {{Use American English|date=October 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox officeholder | {{Infobox officeholder | ||

| | image = {{Easy CSS image crop | |||

| |name = Ulysses Grant | |||

| |image = Ulysses Grant 1870-1880.jpg | |image = Ulysses S. Grant 1870-1880.jpg | ||

| |desired_width = 220 | |||

| |office = ] ] | |||

| |location = center | |||

| |vicepresident = ] <small>(1869–1873)</small><br />] <small>(1873–1875)</small><br />''None'' <small>(1875–1877)</small> | |||

| |crop_top_perc = 5 | |||

| |term_start = March 4, 1869 | |||

| |term_end = March 4, 1877 | |||

| |predecessor = ] | |||

| |successor = ] | |||

| |office2 = ] | |||

| |president2 = ]<br />] | |||

| |term_start2 = March 9, 1864 | |||

| |term_end2 = March 4, 1869 | |||

| |predecessor2 = ] | |||

| |successor2 = ] | |||

| |birth_name = Hiram Ulysses Grant | |||

| |birth_date = {{birth date|1822|4|27}} | |||

| |birth_place = ] | |||

| |death_date = {{death date and age|1885|7|23|1822|4|27}} | |||

| |death_place = ] | |||

| |restingplace = ]<br />], ] | |||

| |party = ] | |||

| |spouse = ] | |||

| |children = ], ], ], ] | |||

| |alma_mater = ] | |||

| |profession = ] | |||

| |religion = ] | |||

| |signature = UlyssesSGrantSignature.svg | |||

| |signature_alt = Cursive signature in ink | |||

| |allegiance = {{nowrap|{{flagu|United States of America|1867}}}} | |||

| |branch = ] | |||

| |serviceyears = 1839–1854<br />1861–1869 | |||

| |rank = ] ] | |||

| |commands = ] <br /> ] <br /> ] <br /> ] | |||

| |battles = ] | |||

| ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| | alt = Photograph of Ulysses S. Grant's upper body | |||

| {{Ulysses Grant sidebar}} | |||

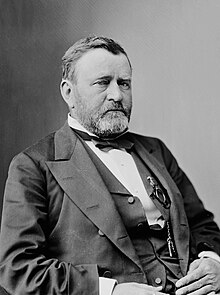

| | caption = Grant {{circa|1870–1880}} | |||

| '''Ulysses S. Grant''' (born '''Hiram Ulysses Grant'''; April 27, 1822 – July 23, 1885) was the ] president of the United States (1869–1877) following his success as military commander in the ]. Under Grant, the ] defeated the ]; the war, and ], ended with the surrender of ]'s army at Appomattox. As president, he led the ] in their effort to eliminate vestiges of Confederate nationalism and slavery, protect ] citizenship, and defeat the ]. In foreign policy, Grant sought to increase American trade and influence while remaining at peace with the world. Although his ] split in 1872 with reformers denouncing him, Grant was easily reelected. During his second term the country's economy was devastated by the ] while investigations exposed corruption scandals in the administration. The ] regained control of Southern state governments and Democrats took control of the federal House of Representatives. As Grant left the White House in 1877, his Reconstruction policies were being undone. | |||

| | order = 18th | |||

| | office = President of the United States | |||

| | vicepresident = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] {{awrap|(1869–1873)}} | |||

| * ] {{awrap|(1873–1875)}} | |||

| * ''None'' {{awrap|(1875–1877)}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | term_start = March 4, 1869 | |||

| | term_end = March 4, 1877 | |||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| | successor = ] | |||

| | office1 = ] | |||

| | president1 = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Andrew Johnson | |||

| }} | |||

| | term_start1 = March 9, 1864 | |||

| | term_end1 = March 4, 1869 | |||

| | predecessor1 = ] | |||

| | successor1 = ] | |||

| | office2 = Acting ] | |||

| | president2 = Andrew Johnson | |||

| | term_start2 = August 12, 1867 | |||

| | term_end2 = January 14, 1868 | |||

| | predecessor2 = ] | |||

| | successor2 = Edwin Stanton | |||

| | office3 = ] | |||

| | term_start3 = 1883 | |||

| | term_end3 = 1884{{sfn|Utter|2015|p=141}} | |||

| | predecessor3 = E. L. Molineux | |||

| | successor3 = ] | |||

| | birth_name = Hiram Ulysses Grant | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1822|4|27}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1885|7|23|1822|4|27}} | |||

| | death_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | resting_place = ], New York City | |||

| | party = ] | |||

| | parents = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | spouse = {{marriage|]|August 22, 1848}} | |||

| | children = {{flatlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | occupation = {{flatlist| | |||

| * Military officer | |||

| * politician | |||

| }} | |||

| | education = ] | |||

| | signature = UlyssesSGrantSignature.svg | |||

| | signature_alt = Cursive signature in ink | |||

| | nickname = {{flatlist| | |||

| * Sam | |||

| * Unconditional Surrender | |||

| }} | |||

| | branch = {{flatlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | serviceyears = {{plainlist| | |||

| * 1839–1854 | |||

| * 1861–1869 | |||

| }} | |||

| | rank = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | commands = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | battles = | |||

| {{collapsible list|title = {{nobold|''See list''}}| | |||

| {{tree list}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Ulysses S. Grant''' (born '''Hiram Ulysses Grant''';{{efn|Pronounced {{IPAc-en|ˈ|h|aɪ|r|ə|m|_|juː|ˈ|l|ɪ|s|iː|z}} {{respell|HY|rəm|_|yoo|LISS|eez}}}} April 27, 1822{{spaced ndash}}July 23, 1885) was the 18th ], serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as ], Grant led the ] to victory in the ]. | |||

| Grant was born in Ohio and graduated from the ] (West Point) in 1843. He served with distinction in the ], but resigned from the army in 1854 and returned to civilian life impoverished. In 1861, shortly after the Civil War began, Grant joined the Union Army and rose to prominence after securing victories in the ]. In 1863, he led the ] that gave Union forces control of the ] and dealt a major strategic blow to the Confederacy. President ] promoted Grant to ] and command of all Union armies after ]. For thirteen months, Grant fought ] during the high-casualty ] which ended with the capture of Lee's army ], where he formally surrendered to Grant. In 1866, President ] promoted Grant to ]. Later, Grant broke with Johnson over Reconstruction policies. A war hero, drawn in by his sense of duty, Grant was unanimously nominated by the Republican Party and then ]. | |||

| As president, Grant stabilized the post-war national economy, supported congressional Reconstruction and ], and prosecuted the ]. Under Grant, the Union was completely restored. An effective civil rights executive, Grant signed a bill to create the ] and worked with ] to protect African Americans during ]. In 1871, he created the ], advancing the civil service more than any prior president. Grant was re-elected in ], but was inundated by executive scandals during his second term. His response to the ] was ineffective in halting the ], which contributed to the Democrats ]. Grant's Native American policy was to assimilate Indians into Anglo-American culture. In Grant's foreign policy, the ] against Britain were peacefully resolved, but the Senate rejected Grant's ]. In the ], Grant facilitated the approval by Congress of a peaceful compromise. | |||

| Leaving office in 1877, Grant undertook ], becoming the first president to circumnavigate the world. In 1880, he ] for a third term. In 1885, impoverished and dying of throat cancer, Grant wrote ], covering his life through the Civil War, which were posthumously published and became a major critical and financial success. At his death, Grant was the most popular American and was memorialized as a symbol of national unity. Due to the ] and ] mythology of the ] spread by Confederate sympathizers around the turn of the 20th century, ] and ] of Grant's presidency suffered considerably before they began recovering in the 21st century. Grant's critics take a negative view of his economic mismanagement and the corruption within his administration, while his admirers emphasize his ], ], and securing North and South as a single nation within the Union.<!--DO NOT remove this citation. This content is not backed up in the body.-->{{sfn|Brands|2012a|p=636}} Modern scholarship has better appreciated Grant's appointments of Cabinet reformers. | |||

| ==Early life and education== | |||

| {{further|Early life and career of Ulysses S. Grant}} | |||

| ] in ]]] | |||

| Grant's father ] was a ] supporter and a fervent abolitionist.{{sfn|Hesseltine|1957|p=4}} Jesse and ] were married on June 24, 1821, and their first child, Hiram Ulysses Grant, was born on April 27, 1822.{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1pp=5–6|White|2016|2pp=8–9}} The name Ulysses was drawn from ballots placed in a hat. To honor his father-in-law, Jesse named the boy "Hiram Ulysses", though he always referred to him as "Ulysses".{{sfnm|Simpson|2014|1pp=2–3|White|2016|2pp=9–10}} In 1823, the family moved to ], where five siblings were born: Simpson, Clara, Orvil, Jennie, and Mary.{{sfn|Longacre|2006|pp=6–7}} At the age of five, Ulysses started at a ] and later attended two private schools.{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1p=497|White|2016|2pp=16, 18}} In the winter of 1836–1837, Grant was a student at ], and in the autumn of 1838, he attended ]'s academy. | |||

| In his youth, Grant developed an unusual ability to ride and manage horses;{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1pp=8, 10, 140–141|White|2016|2p=21}} his father gave him work driving supply wagons and transporting people.{{sfnm|Brands|2012a|1p=8|White|2016|2p=19}} Unlike his siblings, Grant was not forced to attend church by his ] parents.{{sfnm|Longacre|2006|1pp=6–7|Waugh|2009|2p=14}} For the rest of his life, he prayed privately and never officially joined any denomination.{{sfnm|Simpson|2014|1pp=2–3|Longacre|2006|2pp=6–7}} To others, including his own son, Grant appeared to be ].{{sfn|Waugh|2009|p=14}} Grant was largely apolitical before the war but wrote, "If I had ever had any political sympathies they would have been with the Whigs. I was raised in that school."{{sfn|Chernow|2017|pp=99–100}} | |||

| ==Early military career and personal life== | |||

| ===West Point and first assignment=== | |||

| ] | |||

| At Jesse Grant's request, Representative ] nominated Ulysses to the ] at ], in spring 1839. Grant was accepted on July 1.{{sfn|White|2016|pp=24–25}} Unfamiliar with Grant, Hamer altered his name, so Grant was enlisted under the name "U. S. Grant".{{efn|One source states Hamer took the "S" from Simpson, Grant's mother's maiden name.{{sfn|Simon|1967|p=4}} According to Grant, the "S." did not stand for anything. Upon graduation from the academy he adopted the name "Ulysses S. Grant".{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1p=12|Smith|2001|2pp=24, 83|Simon|1967|3pp=3–4}} Another version of the story states that Grant inverted his first and middle names to register at West Point as "Ulysses Hiram Grant" as he thought reporting to the academy with a trunk that carried the initials H.U.G. would subject him to teasing and ridicule. Upon finding that Hamer had nominated him as "Ulysses S. Grant." Grant decided to keep the name so that he could avoid the "hug" monogram; and it was easier to keep the wrong name than to try changing school records.{{sfn|Garland 1898|pages=30–31}}}}{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1p=12|Smith|2001|2pp=24, 83|Simon|1967|3pp=3–4|Kahan|2018|4p=2}} Since the initials "U.S." also stood for "]", he became known among army colleagues as "Sam."{{sfn|White|2016|p=30}} | |||

| Initially, Grant was indifferent to military life, but within a year he reexamined his desire to leave the academy and later wrote that "on the whole I like this place very much".{{sfnm|Simpson|2014|1p=13–14|Smith|2001|2pp=26–28}} He earned a reputation as the ].{{sfn|McFeely|1981|p=10}} Seeking relief from military routine, he studied under ] artist ], producing nine surviving artworks.{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1p=27|McFeely|1981|2pp=16–17}} He spent more time reading books from the library than his academic texts.{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1pp=16–17|Smith|2001|2pp=26–27}} On Sundays, cadets were required to march to services at the academy's church, which Grant disliked.{{sfn|White|2016|p=41}} Quiet by nature, he established a few intimate friends among fellow cadets, including ] and ]. He was inspired both by the Commandant, Captain ], and by General ], who visited the academy to review the cadets. Grant later wrote of the military life, "there is much to dislike, but more to like."{{sfn|Brands|2012a|pp=12–13}} | |||

| Grant graduated on June 30, 1843, ranked 21st out of 39 in his class and was promoted the next day to ] ].{{sfnm|Chernow|2017|1p=27|Longacre|2006|2p=21|Cullum|1850|3pp=256–257}} He planned to resign his commission after his four-year term. He would later write that among the happiest days of his life were the day he left the presidency and the day he left the academy.{{sfnm|Chernow|2017|1p=28|McFeely|1981|2pp=16, 19}} Despite his excellent horsemanship, he was not assigned to the cavalry, but to the ].{{efn|At the time, class ranking largely determined branch assignments. Those at the top of the class were usually assigned to the Engineers, followed by Artillery, Cavalry, and Infantry.{{sfn|Jones|2011|p=1580}}}} Grant's first assignment was the ] near ].{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1pp=28–29|Brands|2012a|2p=15|Chernow|2017|3p=81}} Commanded by Colonel ], this was the nation's largest military base in the West.{{sfn|Smith|2001|pp=28–29}} Grant was happy with his commander but looked forward to the end of his military service and a possible teaching career.{{sfn|Smith|2001|pp=30–33}} | |||

| ===Marriage and family=== | |||

| In 1844, Grant accompanied Frederick Dent to Missouri and met his family, including Dent's sister ]. The two soon became engaged.{{sfn|Smith|2001|pp=30–33}} On August 22, 1848, they were married at Julia's home in St. Louis. Grant's abolitionist father disapproved of the Dents' owning slaves, and neither of Grant's parents attended the wedding.{{sfnm|Chernow|2017|1pp=61–62|White|2016|2p=102|Waugh|2009|3p=33}} Grant was flanked by three fellow West Point graduates in their blue uniforms, including Longstreet, Julia's cousin.{{efn|Several scholars, including ] and ], state that Longstreet was Grant's best man and the two other officers were Grant's groomsmen.{{sfnm|Chernow|2017|1p=62|Smith|2001|2p=73|Flood|2005|3p=2007}} All three went on to serve in the Confederate Army and surrendered to Grant at Appomattox.{{sfn|Chernow|2017|p=62}}}}{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1pp=73–74|Waugh|2009|2p=33|Chernow|2017|3p=62|White|2016|4p=102}} | |||

| The couple had four children: ], ] ("Buck"), ] ("Nellie"), and ].{{sfn|Smith|2001|p=73}} After the wedding, Grant obtained a two-month extension to his leave and returned to St. Louis, where he decided that, with a wife to support, he would remain in the army.{{sfn|Simpson|2014|p=49}} | |||

| ===Mexican–American War=== | |||

| {{main|Mexican–American War}} | |||

| ] during which Grant saw military action]] | |||

| Grant's unit was stationed in Louisiana as part of the ] under Major General ].{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1pp=35–37|Brands|2012a|2pp=15–17}} In September 1846, President ] ordered Taylor to march {{convert|150|mi}} south to the ]. Marching to ], to prevent a Mexican siege, Grant experienced combat for the first time on May 8, 1846, at the ].{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1pp=30–31|Brands|2012a|2p=23}} Grant served as regimental quartermaster, but yearned for a combat role; when finally allowed, he led a charge at the ].{{sfn|White|2016|p=80}} He demonstrated his equestrian ability at the ] by volunteering to carry a dispatch past snipers; he hung off the side of his horse, keeping the animal between him and the enemy.{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1pp=33–34|Brands|2012a|2p=37}} Polk, wary of Taylor's growing popularity, divided his forces, sending some troops (including Grant's unit) to form a new army under Major General ].{{sfn|McFeely|1981|pp=34–35}} | |||

| A career soldier, Grant graduated from the ] and served in the ]. When the Civil War began in 1861, he rejoined the Union army. In 1862, Grant was promoted to major general and took control of ] and most of ]. He then led Union forces to victory after initial setbacks in the ], earning a reputation as an aggressive commander. In July 1863, Grant defeated Confederate armies and seized ], giving the Union control of the ] and dividing the Confederacy in two. After the ] in late 1863, President ] promoted Grant to lieutenant general and commander of all of the Union armies. As commander, Grant confronted Robert E. Lee in a series of bloody battles in 1864, which ended with Grant trapping Lee at ]. During the siege, Grant coordinated a series of devastating campaigns launched by generals ], ], and ] in other theaters. Finally breaking through Lee's trenches, the Union Army captured Richmond in April 1865. Lee surrendered his depleted forces to Grant at Appomattox as the Confederacy collapsed. Most historians have hailed Grant's military genius, despite losses of men.{{sfn|Bonekemper 2004|pp=271–82}} | |||

| Traveling by sea, Scott's army landed at ] and advanced toward ].{{sfn|Brands|2012a|pp=41–42}} They met the Mexican forces at the battles of ] and ].{{sfn|McFeely|1981|p=36}} For his bravery at Molino del Rey, Grant was brevetted first lieutenant on September 30.{{sfnm|White|2016|1p=66|Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War 2013|2p=271}} At San Cosmé, Grant directed his men to drag a disassembled ] into a church steeple, then reassembled it and bombarded nearby Mexican troops.{{sfn|McFeely|1981|p=36}} His bravery and initiative earned him his brevet promotion to captain.{{sfnm|Simpson|2014|1p=44|Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War 2013|2p=271}} On September 14, 1847, Scott's army marched into the city; Mexico ], including ], to the U.S. on February 2, 1848.{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1pp=67–68, 70, 73|Brands|2012a|2pp=49–52}} | |||

| After the ], Grant served two terms as president and worked to stabilize the nation during the turbulent ] period that followed. He enforced civil rights laws and fought ] violence. Grant encouraged passage of the ], giving protection for African-American voting rights. He used the army to build the Republican Party in the South, based on black voters, Northern newcomers ("]") and native white supporters ("]"). As a result, African-Americans were represented in the Congress for the first time in American history in 1870. Although there were some gains in political and civil rights by African Americans in the early 1870s, by the time Grant left office in 1877, Democrats in the South had regained control of state governments, while most blacks lost their political power for nearly a century. Reformers praised Grant's Indian peace policy that reduced Indian violence and created the ].{{sfnm|Brands||1p=501|Smith||2p=525}} In the long run, however, even his supporters agree his policies were unsuccessful. Grant's reputation fell as the economy plunged into the United States first industrial depression, called the ]. In his second term, Grant had to respond to a series of Congressional investigations into financial corruption in the government, including bribery charges of two cabinet members. | |||

| During the war, Grant established a commendable record as a daring and competent soldier and began to consider a career in the army.{{sfn|White|2016|p=75}}{{sfn|Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War 2013|p=271}} He studied the tactics and strategies of Scott and Taylor and emerged as a seasoned officer, writing in his memoirs that this is how he learned much about military leadership.{{sfnm|Simpson|2014|1p=458|Chernow|2017|2p=58}} In retrospect, although he respected Scott, he identified his own leadership style with Taylor's. Grant later believed the Mexican war was morally unjust and that the territorial gains were designed to expand slavery. He opined that the Civil War was divine punishment for U.S. aggression against Mexico.{{sfn|McFeely|1981|pp=30—31, 37–38}} | |||

| Historians have pointed to the importance of Grant's experience as an assistant quartermaster during the war. Although he was initially averse to the position, it prepared Grant in understanding military supply routes, transportation systems, and logistics, particularly with regard to "provisioning a large, mobile army operating in hostile territory", according to biographer Ronald White.{{sfn|White|2016|p=80}} Grant came to recognize how wars could be won or lost by factors beyond the battlefield.{{sfnm|White|2016|1pp=85, 96|Chernow|2017|2p=46}} | |||

| Grant's foreign policy, led by Secretary of State ], settled the ] with Britain and avoided war with ] over the ], but his attempted ] failed. Grant's response to the Panic of 1873 gave some financial relief to New York banking houses, but was ineffective in stopping the five-year industrial depression that followed. After leaving office, Grant embarked on a two-year world tour that included many enthusiastic receptions. In 1880, he made an unsuccessful bid for a third presidential term. However, his ], written as he was dying, were a critical and popular success. His death prompted an outpouring of national mourning. Historians have, until recently, ranked Grant as nearly the worst president. Grant's reputation was marred by his defense of corrupt appointees, and by his conservative deflationary policy during the ]. {{sfnm|Brands 2012b||1p=44|Murray & Blessing||2p=55}} While still below average, his ] has significantly improved in recent years because of greater appreciation for his commitment to civil rights, moral courage in his prosecution of the Ku Klux Klan, and enforcement of voting rights.{{sfn|Brands 2012b|p=44}} | |||

| == |

===Post-war assignments and resignation=== | ||

| Grant's first post-war assignments took him and Julia to ] on November 17, 1848, but he was soon transferred to ], a desolate outpost in upstate New York, in bad need of supplies and repair. After four months, Grant was sent back to his quartermaster job in Detroit.{{sfn|Chernow|2017|p=65}} When the discovery of ] brought prospectors and settlers to the territory, Grant and the 4th infantry were ordered to reinforce the small garrison there. Grant was charged with bringing the soldiers and a few hundred civilians from New York City to Panama, ] to the Pacific and then north to California. Julia, eight months pregnant with Ulysses Jr., did not accompany him.{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1p=76–78|Chernow|2017|2pp=73–74}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Early life and career of Ulysses S. Grant}} | |||

| Hiram Ulysses Grant was born in ] on April 27, 1822 to Jesse Root Grant, a ] and businessman, and Hannah (Simpson) Grant.{{sfn|Smith|pp=21–22}} Jesse Grant was a Whig in politics with abolitionist sentiments.{{sfn|Hesseltine|p=4}} In the fall of 1823, the family moved to the village of ] in ]. Raised in a ] family devoid of religious pretentiousness, Grant prayed privately and was not an official member of the church.{{sfnm|Farina||1pp=13–14|Simpson|2000|2pp=2–3}} Unlike his younger siblings, Grant was neither disciplined, baptized, nor forced to attend church by his parents.{{sfn|Longacre|pp=6–7}} One of his biographers suggests that Grant inherited a degree of introversion from his reserved, even "uncommonly detached" mother (she never took occasion to visit the White House during her son's presidency).{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=8}} Grant developed an unusual ability to work with, and control, horses in his charge, and became known as a capable horseman.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=10}} | |||

| While Grant was in Panama, a ] epidemic killed many soldiers and civilians. Grant organized a field hospital in ], and moved the worst cases to a hospital barge offshore.{{sfn|Chernow|2017|p=74}} When orderlies protested having to attend to the sick, Grant did much of the nursing himself, earning high praise from observers.{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1p=76–78|Chernow|2017|2pp=73–74}} In August, Grant arrived in San Francisco. His next assignment sent him north to ] in the ].{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1p=78|Chernow|2017|2p=75}} | |||

| When Grant was 17, Congressman ] nominated him for a position at the ] (USMA) at ]. Hamer mistakenly wrote down the name as "Ulysses S. Grant of Ohio." At West Point, he adopted this name with a middle initial only. His nickname became "Sam" among army colleagues at the academy, since the initials "U.S." also stood for "Uncle Sam". The "S", according to Grant, did not stand for anything, though Hamer had used it to abbreviate his mother's maiden name.{{sfnm|McFeely 1981||1p=12|Smith||2pp=24, 83}} The influence of Grant's family brought about the appointment to West Point, while Grant himself later recalled "a military life had no charms for me".{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=16}} Grant stood 5 feet 1 inches and weighed 117 lbs when he entered West Point.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=13}} Grant later said that he was lax in his studies, but he achieved above average grades in mathematics and geology.{{sfn|Smith|pp=26–28}} Although Grant had a quiet nature, he established a few intimate friends at West Point, including ] and ].{{sfnm|McFeely 1981||1p=20|Longacre||2p=18}} While not excelling scholastically, Grant studied under ] artist ] and produced nine surviving artworks.{{sfn|Smith|pp=26–28}} He also established a reputation as a fearless and expert horseman, setting an equestrian high-jump record that stood almost 25 years.{{sfn|Smith|pp=26–28}} He graduated in 1843, ranking 21st in a class of 39. Grant was glad to leave West Point and planned to resign his commission after serving the minimum term of obligated duty.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=16, 19}} Despite his excellent horsemanship, he was not assigned to the cavalry, as assignments were determined by class rank, not aptitude.{{sfn|Smith|pp=26–28}} Grant was instead assigned as a regimental quartermaster, managing supplies and equipment in the ], with the rank of brevet ].{{sfnm|Smith||1pp=26–28|Longacre||2p=24}} | |||

| Grant tried several business ventures but failed, and in one instance his business partner absconded with $800 of Grant's investment, {{Inflation|US-GDP|800|1852|r=-3|fmt=eq}}.{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|pp=48–49|Chernow|2017|p=77}} After he witnessed white agents cheating ] of their supplies, and their devastation by ] and ] transferred to them by white settlers, he developed empathy for their plight.{{sfnm|White|2016|1p=487|Chernow|2017|2p=78}} | |||

| ==Military career, 1843–1854== | |||

| Grant's first assignment after graduation took him to the ] near ] in September 1843.{{sfn|Smith|pp=28–29}} It was the nation's largest military bastion in the West, commanded by Colonel ]. Grant was happy with his new commander, but still looked forward to the end of his military service and a possible teaching career.{{sfn|Smith|pp=30–33}} Grant spent some of his time in Missouri visiting the family of his West Point classmate, Frederick Dent, and getting to know Dent's sister, ]; the two became secretly engaged in 1844.{{sfn|Smith|pp=30–33}} | |||

| Promoted to ] on August 5, 1853, Grant was assigned to command Company F, ], at the newly constructed ] in California.{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1p=52|Cullum|1891|2p=171|Chernow|2017|3p=81}} Grant arrived at Fort Humboldt on January 5, 1854, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel ].{{sfn|Chernow|2017|pp=81–83}} Separated from his family, Grant began to drink.{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1p=55|Chernow|2017|2pp=84–85}} Colonel Buchanan reprimanded Grant for one drinking episode and told Grant to "resign or reform." Grant told Buchanan he would "resign if I don't reform."{{sfn|Chernow|2017|p=85}} On Sunday, Grant was found influenced by alcohol, but not incapacitated, at his company's paytable.{{sfnm|Cullum|1891|1p=171|Chernow|2017|2pp=84–85}} Keeping his pledge to Buchanan, Grant resigned, effective July 31, 1854.{{sfnm|Cullum|1891|1p=171|Chernow|2017|2pp=85–86}} Buchanan endorsed Grant's resignation but did not submit any report that verified the incident.{{efn|] said that Grant left the army simply because he was "profoundly depressed" and that the evidence as to how much and how often Grant drank remains elusive.{{sfn|McFeely|1981|p=55}} Jean Edward Smith maintains Grant's resignation was too sudden to be a calculated decision.{{sfn|Smith|2001|p=87}} Buchanan never mentioned it again until asked about it during the Civil War.{{sfn|Smith|2001|p=88}} The effects and extent of Grant's drinking on his military and public career are debated by historians.{{sfn|Farina|2007|p=202}} Lyle Dorsett said Grant was an "alcoholic" but functioned amazingly well. William Farina maintains Grant's devotion to family kept him from drinking to excess and sinking into debt.{{sfnm|Farina|2007|1pp=13, 202|Dorsett|1983}}}}{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1pp=86–87|White|2016|2pp=118–120|McFeely|1981|3p=55}} Grant did not face court-martial, and the War Department said: "Nothing stands against his good name."{{sfn|Longacre|2006|pp=55–58}} Grant said years later, "the vice of intemperance (drunkenness) had not a little to do with my decision to resign."{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1pp=87–88|Lewis|1950|2pp=328–332}} With no means of support, Grant returned to St. Louis and reunited with his family.{{sfn|Brands|2012a|pp=77–78}} | |||

| Rising tensions with Mexico saw Grant's unit shifted to Louisiana that year as a part of the ] under ] ].{{sfn|Smith|pp=35–37}} When the ] broke out in 1846, the Army entered Mexico. Not content with his responsibilities as a quartermaster, Grant made his way to the front lines to engage in the battle, and participated as a ''de facto'' cavalryman at the ].{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=32–33}} The army continued its advance into Mexico. At ], Grant demonstrated his equestrian ability, carrying a dispatch through sniper-lined streets on horseback while mounted in one stirrup.{{sfnm|Longacre||1pp=37–42|Brands 2012a||2pp=34–38}} President ], wary of Taylor's growing popularity, divided his army, sending some troops (including Grant's unit) to form a new army under Maj. Gen. ].{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=34–35}} Scott's army landed at ] and advanced toward ]. The army met the Mexican forces at battles of ] and ] outside Mexico City. At Chapultepec, Grant dragged a ] into a church steeple to bombard nearby Mexican troops.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=36–37}} Scott's army was soon into the city, and the Mexicans agreed to peace not long after. | |||

| ==Civilian struggles, slavery, and politics== | |||

| In his memoirs, Grant later wrote that he had learned about military leadership by observing the decisions and actions of his commanding officers, and in retrospect identified himself with Taylor's style. At the time he felt that the war was a wrongful one and believed that territorial gains were designed to spread slavery throughout the nation; writing in 1883, Grant said "I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day, regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation." He also opined that the later Civil War was inflicted on the nation as punishment for its aggression in Mexico.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=31, 37}} | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1854, at age 32, Grant entered civilian life, without any money-making vocation to support his growing family. It was the beginning of seven years of financial struggles and instability.{{sfnm|Chernow|2017|1pp=95, 106|Simon|2002|2p=242|McFeely|1981|3p=60–61|Brands|2012a|4pp=94–96}} Grant's father offered him a place in the ], branch of the family's leather business, but demanded Julia and the children stay in Missouri, with the Dents, or with the Grants in Kentucky. Grant and Julia declined. For the next four years, Grant farmed with the help of Julia's slave, Dan, on his brother-in-law's property, ''Wish-ton-wish'', near ].{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1pp=58–60|White|2016|2p=125}} The farm was not successful and to earn a living he sold firewood on St. Louis street corners.{{sfn|McFeely|1981|p=61}} | |||

| On August 22, 1848, after a four-year engagement, Grant and Julia were married.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=20, 26}} They would have four children: ]; ]; ]; and ].{{sfn|Smith|p=73}} Grant was assigned to several different posts over the ensuing six years. His first post-war assignments took him and Julia to ] and ], the location that made them the happiest.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=44}} In the spring of 1852, he traveled in to Washington, D.C. in a failed attempt to prevail upon the Congress to rescind an order that he, in his capacity as quartermaster, reimburse the military $1000 in losses incurred on his watch, for which he bore no personal guilt.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=46}} He was sent west to ] in the ] in 1852, initially landing in ] during the height of the ]. Julia could not accompany him as she was eight months pregnant with their second child.{{sfn|Smith|pp=76–77}} The journey proved to be an ordeal due to transportation disruptions and an outbreak of ] within the entourage while traveling overland through Panama. Grant made use of his organizational skills, arranging makeshift transportation and hospital facilities to take care of the sick; even so there were 150 fatalities.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=47}} After Grant arrived in San Francisco he traveled to Fort Vancouver, continuing his service as quartermaster. | |||

| In 1856, the Grants moved to land on Julia's father's farm, and built a home called "Hardscrabble" on ]; Julia described it as an "unattractive cabin".{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1pp=58–60|Chernow|2017|2p=94}} Grant's family had little money, clothes, and furniture, but always had enough food.{{sfn|Brands|2012a|p=96}} During the ], which devastated Grant as it did many farmers, Grant pawned his gold watch to buy Christmas gifts.{{sfn|White|2016|p=128}} In 1858, Grant rented out Hardscrabble and moved his family to Julia's father's ].{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1p=62|Brands|2012a|2p=86|White|2016|3p=128}} That fall, after having ], Grant gave up farming.{{sfnm|Brands|2012a|pp=89–90|White|2016|p=129}} | |||

| To supplement a military salary inadequate to support his family, Grant, assuming his work as quartermaster so equipped him, attempted but failed at several business ventures.{{sfn|Smith|pp=81–82}} The business failures in the West confirmed Jesse Grant's belief that his son had no head for business, creating frustration for both father and son. In one case, Grant had even naively allowed himself to be swindled by a partner.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=48–49}} These failures, along with the separation from his family, made for quite an unhappy soldier, husband and son. Rumors began to circulate that Grant was drinking in excess.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=48–49}} | |||

| That same year, Grant acquired a ] from his father-in-law, a thirty-five-year-old man named William Jones.{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1pp=94–95|White|2016|2p=130}} Although Grant was not an ] at the time, he disliked slavery and could not bring himself to force an enslaved man to work.{{sfn|Brands|2012a|pp=86–87}} In March 1859, Grant freed Jones by a ] deed, potentially worth at least $1,000 (equivalent to ${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|1000|1859|r=-3}}}} in {{Inflation/year|US}}).{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1pp=94–95|McFeely|1981|2p=69|White|2016|3p=130}} | |||

| In the summer of 1853, Grant was promoted to ], one of only fifty on active duty, and assigned to command Company F, 4th Infantry, at ], on the northwest California coast. Without explanation, he shortly thereafter resigned from the army on July 31, 1854. The commanding officer at Fort Humboldt, brevet Lieutenant Colonel ], a strict disciplinarian, had reports that Grant was intoxicated off duty while seated at the pay officer's table. Buchanan had previously warned Grant several times to stop his drinking. In lieu of a court-martial, Buchanan gave Grant an ultimatum to sign a drafted resignation letter. Grant resigned; the War Department stated on his record, "Nothing stands against his good name."{{sfn|Longacre|pp=55–58}} Rumors, however, persisted in the regular army of Grant's intemperance. According to biographer McFeely, historians overwhelmingly agree that his intemperance at the time was a fact, though there are no eyewitness reports extant.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=55}} Two of Grant's lieutenants corroborated this story and Buchanan confirmed it to another officer in a conversation during the Civil War. {{sfnm|Smith||1pp=87–88|Lewis|2pp=328–332}} Years later, Grant said, "the vice of intemperance had not a little to do with my decision to resign."{{sfnm|Smith||1pp=87–88|Lewis|2pp=328–332}} Grant's father, again believing his son's only potential for success to be in the military, tried to get the Secretary of War, ], to rescind the resignation, to no avail.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=57}} | |||

| Grant moved to St. Louis, taking on a partnership with Julia's cousin Harry Boggs working in the real estate business as a bill collector, again without success and at Julia's prompting ended the partnership.{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1p=64|Brands|2012a|2pp=89–90|White|2016|3pp=129–131}} In August, Grant applied for a position as county engineer. He had thirty-five notable recommendations, but Grant was passed over by the ] and ] county commissioners because he was believed to share his father-in-law's ] sentiments.{{sfnm|White|2016|1p=131|Simon|1969|2pp=4–5}} | |||

| ==Civilian life== | |||

| ] | |||

| At age 32, with no civilian vocation, Grant struggled through seven financially lean years. His father, Jesse, initially offered Grant a position in the Galena, Illinois branch of the tannery business, on condition that Julia and the children, for economic reasons, stay with her parents in Missouri, or the Grants in Kentucky. Ulysses and Julia were adamantly opposed to another separation, and declined the offer.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=58–60}} In 1854, Grant farmed on his brother-in-law's property near St. Louis, using slaves owned by Julia's father, but it did not succeed.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=58–60}} Two years later, Grant and family moved to a section of his father-in-law's farm and, to give his family a home, built a house he called "]".{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=58–60}} Julia hated the rustic house, which she described as an "unattractive cabin".{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=58–60}} During this time, Grant also acquired a slave from Julia's father, a thirty-five-year-old man named William Jones.{{sfn|Smith|pp=94–95}} Having met with no success farming, the Grants left the farm when their fourth and final child was born in 1858. Grant freed his slave in 1859 instead of selling him, at a time when slaves commanded a high price and Grant needed money badly.{{sfn|Smith|pp=94–95}} For the next year, the family took a small house in St. Louis where he worked, again without success, with Julia's cousin Harry Boggs, as a bill collector.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=64}} In 1860 Jesse offered him the job in his tannery in ], without condition, which Ulysses accepted. The leather shop, "Grant & Perkins", sold harnesses, saddles, and other leather goods and purchased hides from farmers in the prosperous Galena area. He moved his family to ] that year.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=65–66}} | |||

| In April 1860, Grant and his family moved north to Galena, accepting a position in his father's leather goods business, "Grant & Perkins", run by his younger brothers Simpson and Orvil. In a few months, Grant paid off his debts.{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1pp=65–66|White|2016|2pp=133, 136}} The family attended the local Methodist church and he soon established himself as a reputable citizen.{{sfn|White|2016|pp=135–37}} | |||

| ]Grant was not politically active and never endorsed any candidate before the Civil War.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=69}} His father-in-law was a prominent ] in Missouri, a factor that helped derail Grant's bid to become county engineer in 1859, while his father was an outspoken ] in Galena.{{sfn|Brands 2012a|p=95}} In the 1856 election, Grant cast his first presidential vote for the Democrat, ], saying he was really voting against ], the Republican.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=69}} In 1860, he favored the Democratic presidential candidate ] over ], and Lincoln over the Southern Democrat, ]. Lacking the residency requirements in Illinois at the time, he could not vote. By August 1863, during the ], after the fall of ], Grant's political sympathies fully coincided with the ]' aggressive prosecution of the war and for the abolition of slavery.{{sfn|Catton 1968|p=8}} | |||

| ==Civil War== | ==Civil War== | ||

| {{main|Ulysses S. Grant and the American Civil War}} | {{main|Ulysses S. Grant and the American Civil War}} | ||

| ] | |||

| On April 13, 1861, the ] began as Confederate troops attacked Union ] in Charleston, South Carolina forcing its surrender. Two days later, Lincoln put out a call for 75,000 volunteers. A mass meeting was called in Galena to encourage recruitment. Recognized as the sole military professional in the area, Grant was asked to lead the meeting and ensuing effort. He proceeded to help recruit a company of volunteers and accompanied it to ], the capital of Illinois. Illinois Governor ] offered Grant a position recruiting and training volunteer units, which he accepted, but Grant wanted a field command in the regular Army. He made multiple efforts with contacts (including Maj. Gen. ]) to acquire such a position with no success. Meanwhile, Grant continued serving at the training camps and made a positive impression on the volunteer Union recruits. With the aid of his advocate in Washington, ], Grant was promoted to Colonel by Governor Richard Yates on June 14, 1861, and put in charge of the unruly ]. Transferred to northern Missouri, Grant was promoted by President Lincoln to Brigadier General, supported by Congressman Washburn, backdated to May 17, 1861.{{sfn|Smith|p=113}} By the end of August 1861, Grant was given charge of the southern Illinois, District of ], by Maj. Gen ], an outside Lincoln appointment, who viewed Grant as "a man of dogged persistence, and iron will." Grant's own demeanor had changed immediately at the outset of the war; with renewed energies and confidence.{{sfnm|McFeely 1981||1pp=73–76, 80|Smith||2pp=107–108}} He later recalled with apparent satisfaction that after that first recruitment meeting in Galena, 'I never went into our leather store again..."{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=73}} During this time Grant quickly perceived that the war would be fought for the most part by volunteers, and not professional soldiers.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=80}} | |||

| On April 12, 1861, the ] began when Confederate troops ] in ].{{sfn|White|2016|p=140}} The news came as a shock in Galena, and Grant shared his neighbors' concern about the war.{{sfn|Brands|2012a|p=121}} On April 15, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers.{{sfn|Smith|2001|p=99}} The next day, Grant attended a mass meeting to assess the crisis and encourage recruitment, and a speech by his father's attorney, ], stirred Grant's patriotism.{{sfnm|White|2016|1pp=140–43|Brands|2012a|2pp=121–22|McFeely|1981|3p=73|Bonekemper|2012|4p=17|Smith|2001|5p=99|Chernow|2017|6p=125}} In an April 21 letter to his father, Grant wrote out his views on the upcoming conflict: "We have a government and laws and a flag, and they must all be sustained. There are but two parties now, Traitors and Patriots."{{sfn|Brands|2012a|p=123}} | |||

| ===Forts Henry and Donelson=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Grant's troops first saw action in late 1861, starting out from his base at ], the strategic point where the Ohio River flows into the Mississippi River and near the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers.{{sfn|Brands 2012a|p=151}} The Confederate army was stationed in Columbus, Kentucky under Maj. Gen. ]. Maj. Gen. ] ordered Grant to make "demonstrations", not including attack, against the Confederate Army at Belmont.{{sfn|Brands 2012a|p=151}} After Lincoln relieved Frémont from command, Grant attacked Fort Belmont taking 3,114 Union troops by boat on November 7, 1861. He initially took the fort, but his army was later pushed back to Cairo by the reinforced Confederates under Brig. Gen. ]. A tactical defeat, the battle nonetheless instilled much needed confidence in Grant and his volunteers.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=92–94}} Following Belmont, Grant asked Maj. Gen. ] for permission to move against Fort Henry on the Tennessee River; Halleck agreed on condition that the attack be conducted with oversight by Union Navy ] ]. Grant's troops, in close cooperation with Foote's naval forces successfully captured ] on February 6, 1862 and nearby Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River on February 16.{{sfn|Smith|pp=141–164}} Fort Henry, undermanned by Confederates and nearly submerged from flood waters, was taken over with few losses.{{sfn|Whyte|pp=18–39}} However, at Fort Donelson, Grant and Foote encountered stiffer resistance from the Confederate forces under Pillow. Grant's initial 15,000 troops were joined by 10,000 reinforcements, against 12,000 Confederate troops at Fort Donelson. Foote's initial approach by Union naval ships were repulsed by Donelson's guns. The Confederates, who were surrounded by Grant's army attempted a break out, pushing Grant's right flank into disorganized retreat eastward on the Nashville road.{{sfn|Brands 2012a|pp=164–165}} Grant rallied his troops, resumed the offensive, retook the Union right and attacked Pillow's left. Pillow ordered Confederate troops back into the fort, relinquished command to Brig. Gen. ] who surrendered to Grant the next day. Grant's terms were repeated across the North: "No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted."{{sfn|Brands 2012a|pp=164–165}} Grant became a celebrity in the North, now nicknamed "Unconditional Surrender" Grant. With these victories, President Abraham Lincoln promoted Grant to ] of volunteers.{{sfn|Smith|pp=125–34}} | |||

| === |

===Early commands=== | ||

| {{further|Kentucky in the American Civil War}} | |||

| Grant's advance at Forts Henry and Donelson was the most significant advance into the Confederacy to date. His army, known as the ], had increased to 48,894 men and was encamped on the western side of the Tennessee River. Grant met with Brig. Gen. ], and they prepared to attack the Confederate stronghold of equal numbers at ].{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=111}} The Confederates had the same thing in mind, and moved first at dawn on April 6, 1862, with a full attack on the Union Army at the ]. The objective was to annihilate the western Union offensive in one massive assault. Over 44,000 Confederate troops, led by Generals ] and ], attacked the five divisions of Grant's army bivouacked nine miles south at Pittsburg Landing. Aware of the impending Confederate attack, Union troops sounded the alarm and readied for battle. The Confederates struck hard and pushed the Union Army back towards the Tennessee River. At the end of the day, the Union Army was vulnerable, and might have been destroyed had Beauregard's troops not been too exhausted to continue the fight.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=114}} Avoiding panic, Grant and Sherman rallied their troops for a counterattack the next morning. With reinforcement troops from Maj. Gen. ] and Maj. Gen. ]'s missing division, Grant succeeded in driving the Confederates back to the road from Corinth. Although he stopped short of capturing Beauregard's army, Grant was able to stabilize the Army of the Tennessee.{{sfnm|McFeely 1981||1p=115|Smith||2pp=167–205}} | |||

| On April 18, Grant chaired a second recruitment meeting, but turned down a captain's position as commander of the newly formed militia company, hoping his experience would aid him to obtain a more senior rank.{{sfnm|Brands|2012a|1pp=122–123|McFeely|1981|2p=80|Bonekemper|2012|p=17}} His early efforts to be recommissioned were rejected by Major General ] and Brigadier General ]. On April 29, supported by Congressman ] of Illinois, Grant was appointed military aide to Governor ] and mustered ten regiments into the ]. On June 14, again aided by Washburne, Grant was appointed colonel and put in charge of the ];<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=UIL0021RI | title=Battle Unit Details - the Civil War |publisher=U.S. National Park Service}}</ref> he appointed ] as his ] and brought order and discipline to the regiment. Soon after, Grant and the 21st Regiment were transferred to Missouri to dislodge Confederate forces.{{sfnm|Flood|2005|1pp=45–46|Smith|2001|2p=113|Bonekemper|2012|3pp=18–20}} | |||

| On August 5, with Washburne's aid, Grant was appointed brigadier general of volunteers.{{sfn|Bonekemper|2012|p=21}} Major General ], Union commander of the West, passed over senior generals and appointed Grant commander of the District of Southeastern Missouri.{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1pp=117–18|Bonekemper|2012|2p=21}} On September 2, Grant arrived at ], assumed command by replacing Colonel ], and set up his headquarters to plan a campaign down the Mississippi, and up the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers.{{sfnm|White|2016|1p=159|Bonekemper|2012|2p=21}} | |||

| The battle was the costliest of the war to date, with aggregate Union and Confederate casualties of 23,746, and minimal strategic advantage gained by either side. Nevertheless, Grant received high praise from many corners. He later remarked that the carnage at Shiloh had made it clear to him that the Confederacy would only be defeated by complete annihilation of its armies. Grant was criticized for his decision to keep the Union Army bivouacked rather than entrenched.{{sfn|Brands 2012a|pp=186–187}} Halleck transferred command of the Army of the Tennessee to Brig. Gen. ] and "promoted" Grant to the hollow position of second-in-command of all the armies of the west. As a result, Grant was again on the verge of resigning until Sherman paid a visit to his camp.{{sfn|Brands 2012a|pp=190–192}} Sherman, whose experiences in the military had been similar to Grant's, convinced Grant to remain in the army. During Halleck's sluggish advance on Corinth—covering 19 miles in 30 days—the entire Confederate force there escaped; the 120,000-man Union Army was then broken up. ], an investigative agent for Secretary of War ] at the time, interviewed Grant and related to Lincoln and Stanton that Grant appeared "self-possessed and eager to make war." Lincoln reinstated Grant to his command of the Army of the Tennessee.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=117–21}} | |||

| After the Confederates moved into western Kentucky, taking Columbus, with designs on southern Illinois, Grant notified Frémont and, without waiting for his reply, advanced on ], taking it without a fight on September 6.{{sfnm|Flood|2005|1p=63|White|2016|2p=159|Bonekemper|2012|3p=21}} Having understood the importance to Lincoln of Kentucky's neutrality, Grant assured its citizens, "I have come among you not as your enemy, but as your friend."{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1p=91|Chernow|2017|2pp=153–155}} On November 1, Frémont ordered Grant to "]" against the Confederates on both sides of the Mississippi, but prohibited him from attacking.{{sfn|White|2016|p=168}} | |||

| ===Vicksburg=== | |||

| {{further|Western Theater of the American Civil War}} | |||

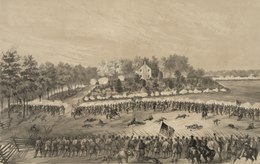

| ], fought on 14 May 1863, in Jackson, Mississippi, was part of the ].]] | |||

| Lincoln was determined to take the strategic Confederate stronghold at ], on the Mississippi River and authorized Maj. Gen. ] to raise an army in his home state of Illinois for the purpose. Grant was very frustrated at the lack of direction he was receiving to move forward from his station in Memphis, and more aggravated to learn of this apparent effort to brush him aside. According to biographer ], this discontent may have been responsible for Grant's ill-considered issuance of ] on December 17, 1862. This order expelled Jews, as a class, from Grant's military district, in reaction to illicit activities of overly aggressive cotton traders in the Union camps, who Grant believed were interfering with military operations.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=123–24}} Lincoln demanded the order be revoked, and Grant rescinded it twenty-one days after issuance. Without admitting fault, Grant believed he had only complied with the instructions sent from Washington. According to another Grant biographer, ], it was "one of the most blatant examples of state-sponsored ] in American history."{{sfn|Smith|pp=225–27}} Grant had believed that gold, along with cotton, was being smuggled through enemy lines and that Jews could pass freely into enemy camps.{{sfn|Longacre|pp=159–61}} Grant later expressed regret for this order in 1868; his attitude concerning Jews was otherwise undeclared.{{sfn|Longacre|pp=159–61}} | |||

| ===Belmont (1861), Forts Henry and Donelson (1862)=== | |||

| In December 1862, with Halleck's approval, Grant moved to take Vicksburg by an overland route, aided by ] and ], in combination with a water expedition on the Mississippi led by Maj. Gen. Sherman. Grant had thus pre-empted his rival McClernand's move. Confederate cavalry raiders Brig. Gen. ] and Maj. Gen. ] stalled Grant's advance by disrupting his communications, while the Confederate army led by Lt. Gen. ] concentrated and repulsed Sherman's direct approach at ]. McClernand afterwards attempted to salvage Sherman's effort to no avail, so at the end of the first day neither Grant nor McClernand had succeeded.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=125–26}} | |||

| {{main|Battle of Belmont|Battle of Fort Henry|Battle of Fort Donelson}} | |||

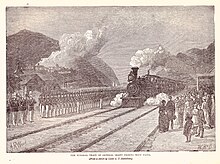

| ], 1887]] | |||

| On November 2, 1861, Lincoln removed Frémont from command, freeing Grant to attack Confederate soldiers encamped in ], Missouri.{{sfn|White|2016|p=168}} On November 5, Grant, along with Brigadier General ], landed 2,500 men at Hunter's Point, and on November 7 engaged the Confederates at the ].{{sfn|White|2016|pp=169–171}} The Union army took the camp, but the reinforced Confederates under Brigadier Generals ] and ] forced a chaotic Union retreat.{{sfn|White|2016|p=172}} Grant had wanted to destroy Confederate strongholds at ], and ], but was not given enough troops and was only able to disrupt their positions. Grant's troops escaped back to Cairo under fire from the fortified stronghold at Columbus.{{sfnm|White|2016|1pp=172–173|Groom|2012|2pp=94, 101–103}} Although Grant and his army retreated, the battle gave his volunteers much-needed confidence and experience.{{sfn|McFeely|1981|pp=92–94}} | |||

| During the second attempt to capture Vicksburg, Grant made a series of unsuccessful and criticized movements along bayou and canal water routes. Finally, in April 1863, Grant marched Union troops down the west side of the Mississippi River and crossed east over at Bruinsburg using Rear Adm. ]'s ships. Grant previously had ordered two diversion battles that confused Pemberton and allowed Grant's army to cross the Mississippi. After a series of battles, including the capture of a railroad junction near ], Grant went on to defeat Pemberton at the ]. Grant then assaulted the Vicksburg fortress twice, and suffered serious losses. After the failed assault, Grant settled in for a siege lasting seven weeks. As the siege began, Grant lapsed into a two-day drinking episode.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=132–35}} Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg to Grant on July 4, 1863.{{sfnm|McFeely 1981||1pp=122–138|Smith||2pp=206–257}} During the campaign, Grant assumed responsibility for refugee-contraband slaves who were displaced by the war and vulnerable to Confederate marauders; Lincoln had authorized their recruitment into the Union Army. Grant put the refugees under the protection of Brig. Gen. ] who authorized them to work on abandoned Confederate plantations to support the war effort. The effort was the precursor to the ] during later Reconstruction. | |||

| Columbus blocked Union access to the lower Mississippi. Grant and lieutenant colonel ] planned to bypass Columbus and move against ] on the ]. They would then march east to ] on the ], with the aid of gunboats, opening both rivers and allowing the Union access further south. Grant presented his plan to ], his new commander in the newly created ].{{sfnm|White|2016|1p=168|McFeely|1981|2p=94}} Halleck rebuffed Grant, believing he needed twice the number of troops. However, after consulting McClellan, he finally agreed on the condition that the attack would be in close cooperation with the navy ], ].{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1pp=138–142|Groom|2012|2pp=101–103}} Foote's gunboats bombarded Fort Henry, leading to its surrender on February 6, 1862, before Grant's infantry even arrived.{{sfn|Smith|2001|p=146}} | |||

| The fall of Vicksburg gave the Union control over the entire Mississippi and split the Confederacy in two. Grant demonstrated that an indirect assault coupled with diversionary tactics was highly effective strategy in defeating an entrenched army. Although the success at Vicksburg was a great morale boost for the Union war effort, Grant received much criticism for his decisions and his reported drunkenness. Lincoln again sent Dana to keep a watchful eye on Grant's alleged intemperance; Dana eventually became Grant's devoted ally, and made light of the drinking.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=128, 135}} The personal rivalry between McClernand and Grant continued over Vicksburg, but ended when Grant removed McClernand from command after he issued, and arranged the publication of, a military order in contravention of Grant. | |||

| Grant ordered an immediate ], which dominated the Cumberland River. Unaware of the garrison's strength, Grant, McClernand, and Smith positioned their divisions around the fort. The next day McClernand and Smith independently launched probing attacks on apparent weak spots but were forced to retreat. On February 14, Foote's gunboats began bombarding the fort, only to be repulsed by its heavy guns. The next day, Pillow attacked and routed McClernand's division. Union reinforcements arrived, giving Grant a total force of over 40,000 men. Grant was with Foote four miles away when the Confederates attacked. Hearing the battle, Grant rode back and rallied his troop commanders, riding over seven miles of freezing roads and trenches, exchanging reports. When Grant blocked the Nashville Road, the Confederates retreated back into Fort Donelson.{{sfn|Axelrod|2011|p=210}} On February 16, Foote resumed his bombardment, signaling a general attack. Confederate generals ] and Pillow fled, leaving the fort in command of ], who submitted to Grant's demand for "unconditional and immediate surrender".{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1pp=141–164|Brands|2012a|2pp=164–165}} | |||

| ===Chattanooga and promotion=== | |||

| ] and defeat Bragg's army.]] | |||

| Lincoln put Grant in command of the newly formed ] in October 1863, giving Grant charge of the entire western theater of war, except for Louisiana. After the ], Confederate Gen. ] forced Maj. Gen. ]'s Army of the Cumberland to retreat into Chattanooga, a central railway hub, surrounded the city and trapped the Union army inside. Only Maj. Gen. ] and the XIV Corps kept the Army of the Cumberland from complete defeat at the Battle of Chickamauga. When informed of the ominous situation at Chattanooga, Grant relieved Rosecrans from duty and placed Thomas in charge of the besieged ]. To stop the siege and go on the attack, Grant, personally rode out to Chattanooga and took charge of the desperate situation. Lincoln sent Maj. Gen. ] and two divisions of the Army of the Potomac to reinforce the Army of the Cumberland, however, the Confederates kept the two armies from meeting. Grant's first action was to open up a supply line to the Army of the Cumberland trapped in Chattanooga. Following a plan devised by Maj. Gen. ], a "Cracker Line" was formed with Hooker's Army of the Potomac on Lookout Mountain and supplied the Army of the Cumberland with food and weapons.{{sfnm|McFeely 1981||1pp=139–51|Smith||2pp=262–71}} | |||

| Grant had won the first major victory for the Union, capturing Floyd's entire army of more than 12,000. Halleck was angry that Grant had acted without his authorization and complained to McClellan, accusing Grant of "neglect and inefficiency". On March 3, Halleck sent a telegram to Washington complaining that he had no communication with Grant for a week. Three days later, Halleck claimed "word has just reached me that ... Grant has resumed his bad habits (of drinking)."{{sfn|Groom|2012|pp=138, 143–144}} Lincoln, regardless, promoted Grant to major general of volunteers and the Northern press treated Grant as a hero. Playing off his initials, they took to calling him "Unconditional Surrender Grant".{{sfnm|Brands|2012a|1pp=164–165|Smith|2001|2pp=125–134}} | |||

| On November 23, 1863, Grant organized three armies to attack Bragg's troops on ] and ]. The next day, Sherman and four divisions of the Army of the Tennessee assaulted Bragg's right flank. Thomas and the ] overtook Confederate picket trenches at the base of Missionary Ridge. Hooker's forces took Lookout Mountain and captured 1,064 prisoners. On November 25, Sherman continued his attack on Bragg's right flank on the northern section of Missionary Ridge. In response to Sherman's assault Bragg withdrew Confederate troops on the main ridge to reinforce the Confederate right flank. Seeing that Bragg was reinforcing his right flank, Grant ordered Thomas to make a general assault on Missionary Ridge. After a brief delay, the Army of the Cumberland, led by Maj. Gen. ] and Brig. Gen. ], captured the first Confederate entrenchments. Without further orders, the Army of the Cumberland continued up hill and captured the Confederate's secondary entrenchments on top of Missionary Ridge; forcing the defeated Confederates into disorganized retreat. Although Bragg's army had not been captured, the decisive battle opened ] and the heartland of the Confederacy to Union invasion. Grant's fame increased and he was promoted to ], a position that had previously been given only to George Washington and Winfield Scott.{{sfn|Smith|pp=258–281}} | |||

| ===Shiloh (1862) and aftermath=== | |||

| ] Ulysses S. Grant]] | |||

| {{further|Battle of Shiloh}} | |||

| Disappointed with Maj. Gen. George Meade's failure to pursue Lee after the Confederate defeat at the ], Lincoln made Grant commander of all Union armies in March 1864.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=148}} Grant gave the Department of the Mississippi to Sherman, and went east to Washington, D.C., to devise a strategy with Lincoln. After settling Julia into a house in Georgetown, Grant established his headquarters fifty miles away, near Meade's Army of the Potomac in Culpeper, Virginia.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=156}} The Union strategy of a comprehensive effort to bring about a speedy victory for the Union consisted of coordinated Union offensives, attacking the rebel armies at the same time to keep the Confederates from shifting reinforcements within southern interior lines. Maj. Gen. Sherman would attack ] and Georgia, while Maj. Gen. Meade would lead the Army of the Potomac, with Grant in camp, to attack ]'s ]. Maj. Gen. ] was to attack and advance towards Richmond from the south, going up the ].{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=157}} Depending on Lee's actions, Grant would join forces with Butler's armies and be fed supplies from the James River. Maj. Gen. ] was to capture the railroad line at ], move east, and attack from the ].{{sfnm|McFeely 1981||1pp=157–175|Smith||2pp=313–39, 343–68}} Grant was riding a rising tide of popularity, and there were discussions in some corners that a Union victory early in the year could open the possibility of his candidacy for the presidency. Grant was aware of it, but had ruled it out in discussions with Lincoln; in any case, the possibility would soon vanish with delays on the battlefield.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|pp=162–63}} | |||

| ], 1888]] | |||

| Reinstated by Halleck at the urging of Lincoln and Secretary of War ], Grant rejoined his army with orders to advance with the ] into Tennessee. His main army was located at ], while 40,000 Confederate troops converged at ].{{sfnm|White|2016|1p=210|Barney|2011|2p=287}} Grant wanted to attack the Confederates at Corinth, but Halleck ordered him not to attack until Major General ] arrived with his division of 25,000.{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1pp=111–112|Groom|2012|2p=63|White|2016|3p=211}} Grant prepared for an attack on the Confederate army of roughly equal strength. Instead of preparing defensive fortifications, they spent most of their time drilling the largely inexperienced troops while Sherman dismissed reports of nearby Confederates.{{sfnm|Groom|2012|1pp=62–65|McFeely|1981|2p=112}} | |||

| ===Overland Campaign and victory=== | |||

| Sigel's and Butler's efforts sputtered and Grant was left alone to fight Lee in a series of bloody battles of attrition known as the ]. After taking the month of April 1864 to assemble and ready the Army of the Potomac, Grant crossed the ] on May 4 and attacked Lee in the ], a hard-fought three-day battle with many casualties. Rather than retreat as his predecessors had done, Grant flanked Lee's army to the southeast and attempted to wedge the Union Army between Lee and Richmond at Spotsylvania.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=165}} Lee's army got to ] first and a costly battle began that lasted thirteen days. During the battle, Grant attempted to break through Lee's line of defense at the Mule Shoe, which resulted in one of the bloodiest assaults during the Civil War, known as ]. Unable to break Lee's line of defense after repeated attempts, Grant flanked Lee to the southeast east again at ], a battle that lasted three days.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=169}} This time the Confederate Army had a superior defensive advantage on Grant. Grant then maneuvered the Union Army to ], a vital railroad hub that was linked to Richmond, but Lee's men were able to entrench against the Union assault. During the third day of the thirteen-day battle, Grant led a costly assault on Lee's trenches. As news spread in the North, heavy criticism fell on Grant, who was called "the Butcher", having taken 52,788 casualties in thirty days since crossing the Rapidan.{{sfn|Bonekemper 2011|pp=41–42}} Lee suffered 32,907 Confederate casualties, and was less able to replace them.{{sfn|Bonekemper 2011|pp=41–42}} When the two armies had fought to a stalemate, the generals took three days to reach a truce, so that the dead and dying could be removed from the battlefield.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=171}} The costly June 3 assault at Cold Harbor was the second of two battles in the war which Grant later distinctly regretted.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=173}} Unknown to Lee, Grant pulled out of Cold Harbor and moved his army south of the James River, freed Maj. Gen. Butler from ], and attacked Petersburg, Richmond's central railroad hub.{{sfnm|McFeely 1981||1pp=157–175|Smith||2pp=313–39, 343–68}} | |||

| On the morning of April 6, 1862, Grant's troops were taken by surprise when the Confederates, led by Generals ] and ], struck first "like an Alpine avalanche" near Shiloh church, attacking five divisions of Grant's army and forcing a confused retreat toward the Tennessee River.{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1p=111|Bonekemper|2012|2pp=51, 94|Barney|2011|3p=287}} Johnston was killed and command fell upon Beauregard.{{sfn|White|2016|pp=217–218}} One Union line held the Confederate attack off for several hours, giving Grant time to assemble artillery and 20,000 troops near Pittsburg Landing.{{sfn|Bonekemper|2012|pp=51, 58–59, 63–64}} The Confederates finally broke and captured a Union division, but Grant's newly assembled line held the landing, while the exhausted Confederates, lacking reinforcements, halted their advance.{{sfnm|McFeely|1981|1p=114|Flood|2005|2pp=109, 112|Bonekemper|2012|3pp=51, 58–59, 63–64}}{{efn|The April 6th fighting had been costly, with thousands of casualties. That evening, heavy rain set in. Sherman found Grant standing alone under a tree in the rain. "Well, Grant, we've had the devil's own day of it, haven't we?" Sherman said. "Yes," replied Grant. "Lick 'em tomorrow, though."{{sfn|Chernow|2017|p=205}}}} | |||

| {{stack| | |||

| ] | |||

| Bolstered by 18,000 troops from the divisions of Major Generals Buell and ], Grant counterattacked at dawn the next day and regained the field, forcing the disorganized and demoralized rebels to retreat to Corinth.{{sfnm|Bonekemper|2012|1pp=59, 63–64|Smith|2001|2p=206}} Halleck ordered Grant not to advance more than one day's march from Pittsburg Landing, stopping the pursuit.{{sfn|McFeely|1981|p=115–16}} Although Grant had won the battle, the situation was little changed.{{sfn|McFeely|1981|p=115}} Grant, now realizing that the South was determined to fight, would later write, "Then, indeed, I gave up all idea of saving the Union except by complete conquest."{{sfnm|Brands|2012a|1pp=187–88}} | |||

| ] surrendered to Grant at the Appomatox Court House.]] | |||

| }} | |||

| Shiloh was the costliest battle in American history to that point and the staggering 23,746 casualties stunned the nation.{{sfnm|Bonekemper|2012|1p=94|White|2016|2p=221}} Briefly hailed a hero for routing the Confederates, Grant was soon mired in controversy.{{sfn|White|2016|pp=223–224}} The Northern press castigated Grant for shockingly high casualties, and accused him of drunkenness during the battle, contrary to the accounts of those with him at the time.{{sfnm|Kaplan|2015|1pp=1109–1119|White|2016|2pp=223–225}} Discouraged, Grant considered resigning but Sherman convinced him to stay.{{sfnm|Brands|2012a|1pp=188–191|White|2016|2pp=230–231}} Lincoln dismissed Grant's critics, saying "I can't spare this man; he fights."{{sfn|White|2016|pp=225–226}} Grant's costly victory at Shiloh ended any chance for the Confederates to prevail in the Mississippi valley or regain its strategic advantage in the West.{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1p=204|Barney|2011|2p=289}} | |||

| After Grant and the Army of the Potomac had crossed the James River undetected and rescued Maj. Gen. Butler from the Bermuda Hundred, Grant advanced the army southward to capture ]. Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard, in charge of Petersburg, was able to defend the city and Lee's veteran reinforcements arrived. Grant forced Lee into a long nine-month siege of Petersburg and the war effort stalled.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=178}} Northern resentment grew as the war dragged on, but an indirect benefit of the Petersburg siege was found in preventing Lee from reinforcing armies to oppose Sherman and Sheridan.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=186}} During the siege, Sherman was able to take Atlanta, a victory that advanced President Lincoln's reelection. Maj. Gen. Sheridan was given command of the ] and directed to "follow the enemy to their death".{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=181}} Lee had sent General ] up the Shenandoah Valley to attack the federal capital and draw troops away from the Army of the Potomac, but Sheridan defeated Early, saving Washington from capture. Grant then ordered Sheridan's cavalry to destroy vital Confederate supply farms in the Shenandoah Valley. When Sheridan reported suffering attacks by irregular Confederate cavalry under ], Grant recommended rounding up their families for imprisonment as hostages at Ft. McHenry.{{sfn|McFeely 1981|p=181}} | |||

| Halleck arrived from St. Louis on April 11, took command, and assembled a combined army of about 120,000 men. On April 29, he relieved Grant of field command and replaced him with Major General ]. Halleck slowly marched his army to take Corinth, entrenching each night.{{sfn|White|2016|p=229}} Meanwhile, Beauregard pretended to be reinforcing, sent "deserters" to the Union Army with that story, and moved his army out during the night, to Halleck's surprise when he finally ] on May 30.{{sfnm|White|2016|1p=230|Groom|2012|2pp=363–364}} | |||

| Halleck divided his combined army and reinstated Grant as field commander on July 11.{{sfnm|Longacre|2006|1p=137|White|2016|2p=231}} Later that year, on September 19, Grant's army defeated Confederates at the ], then successfully ], inflicting heavy casualties.{{sfn|Brands|2012a|pp=211–212}} On October 25, Grant assumed command of the District of the Tennessee.{{sfn|Badeau|1887|p=126}} In November, after Lincoln's preliminary ], Grant ordered units under his command to incorporate former slaves into the Union Army, giving them clothes, shelter, and wages for their services.{{sfn|Flood|2005|p=133}} | |||

| ===Vicksburg campaign (1862–1863)=== | |||

| {{further|Vicksburg Campaign|General Order No. 11 (1862)}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| The Union capture of ], the last Confederate stronghold on the ], was considered vital as it would split the Confederacy in two.{{sfnm|White|2016|1p=243|Miller|2019|2p=xii|Chernow|2017|3p=236}} Lincoln appointed McClernand for the job, rather than Grant or Sherman.{{sfnm|Brands|2012a|1pp=221–223|Catton|2005|2p=112|Chernow|2017|3pp=236–237}} Halleck, who retained power over troop displacement, ordered McClernand to ], and placed him and his troops under Grant's authority.{{sfnm|Flood|2005|1pp=147–148|White|2016|2p=246|Chernow|2017|3pp=238–239}} | |||

| On November 13, 1862, Grant captured ] and advanced to ].{{sfnm|White|2016|1p=248|Chernow|2017|2pp=231–232}} His plan was to attack Vicksburg overland, while Sherman would attack Vicksburg from Chickasaw Bayou.{{sfn|Chernow|2017|p=239}} However, Confederate cavalry raids on December 11 and 20 broke Union communications and recaptured Holly Springs, preventing Grant and Sherman from converging on Vicksburg.{{sfnm|Catton|2005|1pp=119, 291|White|2016|2pp=248–249|Chernow|2017|3pp=239–241}} McClernand reached Sherman's army, assumed command, and independently of Grant led a campaign that captured Confederate ].{{sfn|Bonekemper|2012|pp=147–148}} After the sack of Holly Springs, Grant considered and sometimes adopted the strategy of foraging the land,{{sfn|Miller|2019|p=248}} rather than exposing long Union supply lines to enemy attack.{{sfn|Smith|2001|p=244}} | |||

| Fugitive ] slaves poured into Grant's district, whom he sent north to Cairo to be domestic servants in Chicago. However, Lincoln ended this when Illinois political leaders complained.{{sfn|Miller|2019|pp=206–207}} On his own initiative, Grant set up a pragmatic program and hired Presbyterian chaplain ] to administer ] camps.{{sfn|Miller|2019|pp=206–209}} Freed slaves picked cotton that was shipped north to aid the Union war effort. Lincoln approved and Grant's program was successful.{{sfn|Miller|2019|pp=209–210}} Grant also worked freed black labor on ] to bypass Vicksburg, incorporating the laborers into the Union Army and Navy.{{sfnm|White|2016|pp=1246–1247|Miller|2019|2p=154–155}} | |||

| ], fought on May 14, 1863, was part of the ].]] | |||

| Grant's war responsibilities included combating illegal Northern cotton trade and civilian obstruction.{{sfnm|Smith|2001|1p=225|White|2016|2pp=235–36}}{{efn|Smuggling of cotton was rampant, while the price of cotton skyrocketed.{{sfn|Chernow|2017|p=232}} Grant believed the smuggling funded the Confederacy and provided them with military intelligence.{{sfnm|Flood|2005|1pp=143–144, 151|Sarna|2012a|2p=37|White|2016|3pp=235–236}}}} He had received numerous complaints about Jewish speculators in his district.{{sfn|Miller|2019|p=259}} The majority, however, of those involved in illegal trading were not Jewish.{{sfnm|Chernow|2017|1pp=232–33|Howland|1868|2pp=123–24}} To help combat this, Grant required two permits, one from the Treasury and one from the Union Army, to purchase cotton.{{sfn|Chernow|2017|p=232}} On December 17, 1862, Grant issued a controversial ], expelling "Jews, as a class", from his military district.{{sfnm|Brands|2012a|1p=218|Shevitz|2005|2p=256}} After complaints, Lincoln rescinded the order on January 3, 1863. Grant finally ended the order on January 17. He later described issuing the order as one of his biggest regrets.{{efn|In 2012, historian ] said: "Gen. Ulysses S. Grant issued the most notorious anti-Jewish official order in American history."{{sfn|Sarna|2012b}} Grant made amends with the Jewish community during his presidency, appointing them to various federal positions.{{sfnm|Sarna|2012a|1pp=89, 147|White|2016|2p=494|Chernow|2017|3p=236}} In 2017, biographer Ron Chernow said of Grant: "As we shall see, Grant as president atoned for his action in a multitude of meaningful ways. He was never a bigoted, hate-filled man and was haunted by his terrible action for the rest of his days."{{sfn|Chernow|2017|p=236}}}}{{sfn|Smith|2001|pp=226–227}} | |||