| Revision as of 00:33, 14 January 2014 editIronGargoyle (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators152,423 editsm Reverted edits by 74.104.189.98 (talk) to last revision by ClueBot NG (HG)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:28, 9 January 2025 edit undoWikiCleanerBot (talk | contribs)Bots928,066 editsm v2.05b - Bot T20 CW#61 - Fix errors for CW project (Reference before punctuation)Tag: WPCleaner | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Egyptian god of the desert, storms, violence, and foreigners}} | |||

| {{about|the Egyptian deity|the third son of Adam and Eve|Seth||Set (disambiguation)|and|Seth (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Infobox deity | {{Infobox deity | ||

| | type |

| type = Egyptian | ||

| | name |

| name = Set | ||

| | image |

| image = Set.svg | ||

| | hiero = <hiero>s t:S E20 </hiero> | |||

| | image_size = | |||

| | cult_center = ], ], ] | |||

| | alt = | |||

| | symbol = ], ] | |||

| | caption = | |||

| | parents = ], ] | |||

| | god_of = '''God of storms, the desert, and chaos''' | |||

| | siblings = ], ], ], ] | |||

| | hiro = | |||

| | consort = ], ], ], and ] | |||

| | cult_center = ] | |||

| | offspring = ] (disputed),<ref>Doxey, Denise (2001). ''Anubis''. In: In D. Redford, ed. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. I.Oxford: Oxford University Press. p.98.</ref> ]<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.museumofmythology.com/Egypt/sobek.htm | title=Sobek from Ancient Egypt }}</ref> (in some accounts) and Maga<ref name=Ritner-1984>{{cite journal |last=Ritner |first=Robert K. |year=1984 |title=A uterine amulet in the Oriental Institute collection |journal=Journal of Near Eastern Studies |volume=43 |issue=3 |pages=209–221|doi=10.1086/373080 |pmid=16468192 |s2cid=42701708 }}</ref> | |||

| | symbol = The '']'' ] | |||

| | greek_equivalent = ] | |||

| | parents = ] and ] | |||

| | siblings = ], ], ], | |||

| | consort = ], ] (in some accounts), ], ] | |||

| | offspring = ], ] (in some accounts) | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Ancient Egyptian religion}} | |||

| {{Hiero|Seth|<hiero>sw-W-t:x-E20-A40</hiero><br />or<br /><hiero>s-t:S</hiero><br />or<br /><hiero>z:t:X</hiero>| translittération = Swtḫ|align=right|era=Egypt}} | |||

| '''Set''' {{IPAc-en|s|ɛ|t}} |

'''Set''' ({{IPAc-en|s|ɛ|t}}; ]: '''''Sutekh''' - swtẖ ~ stẖ''{{efn|Also transliterated '''Seth''', '''Setesh''', '''Sutekh''', '''Seteh''', '''Setekh''', or '''Suty'''. Sutekh appears, in fact, as a god of Hittites in the treaty declarations between the Hittite kings and ] after the battle of Qadesh. Probably '''Seteh''' is the lection (reading) of a god honoured by the Hittites, the "Kheta", afterward assimilated to the local Afro-Asiatic Seth.<ref name=Sayce-nd-Hittites/><ref name=Budge-nd-HstEgy/>}} or: '''Seth''' {{IPAc-en|s|ɛ|θ}}) is a ] of ]s, storms, disorder, violence, and foreigners in ].<ref name="oxford">{{cite encyclopedia|author=Herman Te Velde |title=Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt|chapter=Seth |year=2001|volume=3}}</ref>{{rp|269}} In ], the god's name is given as {{lang|grc-latn|Sēth}} ({{lang|grc-Grek|Σήθ|italic=no}}). Set had a positive role where he accompanies ] on his ] to repel ] (Apophis), the serpent of Chaos.<ref name="oxford"/>{{rp|269}} Set had a vital role as a reconciled combatant.<ref name="oxford"/>{{rp|269}} He was lord of the Red Land (desert), where he was the balance to ]' role as lord of the Black Land (fertile land).<ref name="oxford"/>{{rp|269}} | ||

| In ], Set is portrayed as the ] who |

In the ], the most important ], Set is portrayed as the ] who murdered and mutilated his own brother, ]. Osiris's sister-wife, ], reassembled his corpse and ] her dead brother-husband with the help of the ] ]. The resurrection lasted long enough to conceive his son and heir, ]. Horus sought revenge upon Set, and many of the ancient Egyptian myths describe their conflicts.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Strudwick|first=Helen|title=The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt|publisher=Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.|year=2006|isbn=978-1-4351-4654-9|location=New York|pages=124–125}}</ref> | ||

| == Family == | == Family == | ||

| ]|left]] | |||

| Set is the son of Geb, the Earth, and ], the Sky; his siblings are ], ], and ]. He married Nephthys and had had relationships with the foreign goddesses ] and ] in some accounts. Though it has commonly been assumed that Set was married to Nephthys and therefore must have been considered the father of Anubis,<ref>Doxey 2001,p.98.</ref><ref>E.A. Wallis Budge, "Nephthys", in "The Gods of the Egyptians or Studies in Egyptian Mythology: Volume 2", London: Methuen & Co, 1904, p.254.</ref> some Egyptologists, such as Herman te Velde, have heavily doubted whether Set was ever regarded as Anubis's father in ancient Egyptian religion.<ref name="oxford"/>{{rp|270}}<ref>Herman te Velde(1968). ''The Egyptian God Seth as a Trickster''. In: Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 7, p.39.</ref><ref>Levai, Jessica. "Nephthys and Seth: Anatomy of a Mythical Marriage", Paper presented at The 58th Annual Meeting of the American Research Center in Egypt, Wyndham Toledo Hotel, Toledo, Ohio, Apr 20, 2007.</ref> From these relationships is said to be born a crocodile deity called Maga.<ref name=Rogers-2019>{{cite journal |last=Rogers |first=John |year=2019 |title=The demon-deity Maga: geographical variation and chronological transformation in ancient Egyptian demonology |journal=Current Research in Egyptology 2019 |pages=183–203 |url=https://www.academia.edu/46879153 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Name origin== | |||

| Set's siblings are Osiris, Isis, and Nephthys. He married Nephthys and fathered ]; and in some accounts he had relationships with other goddesses: Hathor, Neith and the foreign goddesses Anat, and Astarte.<ref>Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, vol. 3, p. 270</ref> His homosexual episodes with Horus result in them fathering the moon god ].<ref>Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, vol. 3, p. 269</ref> | |||

| The meaning of the name ''Set'' is unknown, but it is thought to have been originally pronounced *''sūtiẖ'' based on spellings of his name in ] as ''stẖ'' and ''swtẖ''.{{sfn|te Velde |1967 |pp=1–7}} The ] spelling ''stš'' reflects the palatalization of ''ẖ'' while the eventual loss of the final consonant is recorded in spellings like ''swtj.''<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://aaew.bbaw.de/tla/servlet/S05?d=d001 |title=Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae|website=aaew2.bbaw.de|access-date=2017-09-21}}</ref> The ] form of the name, {{Coptic|ⲥⲏⲧ}} ''Sēt,'' is the basis for the English vocalization.{{sfn|te Velde |1967 |pp=1–7}}<ref>{{cite web |url=https://corpling.uis.georgetown.edu/coptic-dictionary/entry.cgi?entry=2733&super=1095 |title=Coptic Dictionary Online |website=corpling.uis.georgetown.edu |access-date=2017-03-16}}</ref> | |||

| == |

==Set animal== | ||

| {{main|Set animal}}{{Hiero | |||

| The meaning of the name ''Seth'' is unknown, thought to have been originally pronounced *{{unicode|Sūtaḫ}} based on the occurrence of his name in ] (''{{unicode|swtḫ}}''), and his later mention in the ] documents with the name ''Sēt''.<ref>.H. te Velde, ''Seth, God of Confusion: A Study of His Role in Egyptian Mythology and Religion'', Probleme der Ägyptologie, 6 , G. E. van Baaren-Pape, transl. (W. Helck. Leiden: Brill 1967), pp.1-7.</ref> | |||

| |1={{unbulleted list | |||

| |1=(top) Sutekh with the Set animal determinative | |||

| |2=(middle) Set | |||

| |3=(below) Sutekh - another written form}} | |||

| |2={{center|<hiero>sw-W-t:X-E20-A40</hiero>}}<br />or<br />{{center|<hiero>s-t:S</hiero>}}<br />or<br />{{center|<hiero>z:t:X</hiero>}} | |||

| |translit=Swtḫ |align=right |era=Egypt}} | |||

| ] | |||

| In ], Set is usually depicted as an enigmatic creature referred to by ] as the '']'', a beast not identified with any known animal, although it could be seen as resembling a ], an ], an ], a ], a ], a ], a ], an ], a ], or a ]. The animal has a downward curving ]; long ears with squared-off ends; a thin, forked tail with sprouted fur tufts in an inverted arrow shape; and a slender ] body. Sometimes, Set is depicted as a human with the distinctive head. Some early Egyptologists proposed that it was a stylised representation of the ], owing to the large flat-topped "horns" which correspond to a giraffe's ]s. The Egyptians themselves, however, used distinct depictions for the giraffe and the ]. During the ], Set is usually depicted as a ] or as a man with the head of a donkey,{{sfn|te Velde |1967 |pp=13–15}} and in the '']'', Set is depicted with a ] head.<ref>{{cite book |last=Beinlich |first=Horst |url=https://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/propylaeumdok/2891/1/Beinlich_Faiyum_2013.pdf |title=The Book of the Faiyum |publisher=University of Heidelberg |year=2013 |pages=27–77, esp.38–39 |section=Figure 7}}</ref> | |||

| | date=2017 | isbn=978-88-6969-180-5 | doi=10.14277/6969-180-5/ant-11-8 | page=}}</ref>]] | |||

| ===Set animal=== | |||

| {{main|Set animal}} | |||

| In ], Set is mostly depicted as a fabulous creature, referred to by ] as the '']'' or ''Typhonic beast''. The animal has a curved ], long, rectangular ears, a forked tail, and ] body; sometimes, Set is depicted as a human with only the head of the ''Set animal''. It does not resemble any known creature, although it could be seen as a composite of an ], a ], a ], or a ]. Some early Egyptologists have proposed that it was a stylised representation of the ], due to the large flat-topped 'horns' which correspond to a giraffe's ossicones. However, the Egyptians make a distinction between the giraffe and the Set animal. In the Late Period, Set is depicted as a donkey or with the head of a donkey.<ref>H. te Velde, ''Seth, God of Confusion: A Study of His Role in Egyptian Mythology and Religion'', Probleme der Ägyptologie, 6 , G. E. van Baaren-Pape, transl. (W. Helck. Leiden: Brill 1967), pp.13-15.</ref> | |||

| The earliest representations of what |

The earliest representations of what might be the ] comes from a tomb dating to the ] ("Naqada I") of ] (3790–3500 BCE), although this identification is uncertain. If these are ruled out, then the earliest Set animal appears on a ]head of ], a ruler of the ] phase. The head and the forked tail of the Set animal are clearly present on the mace.{{sfn|te Velde |1967 |pp=7–12}} | ||

| ==Conflict of Horus and Set== | |||

| ] and ]]] | |||

| In the mythology of Heliopolis, Set was born of the sky goddess ] and the earth god ]. Set's sister and wife was ]. Nut and Geb also produced another two children who became husband and wife: the divine ] and ], whose son was ]. The ] appears in many Egyptian sources, including the ], the ], the ], inscriptions on the walls of the temple of Horus at ], and various ] sources. The ] Papyrus No. 1 contains the legend known as ]. ] authors also recorded the story, notably ]'s ''De Iside et Osiride''.<ref>H. te Velde, ''Seth, God of Confusion: A Study of His Role in Egyptian Mythology and Religion'', Probleme der Ägyptologie, 6, G. E. van Baaren-Pape, transl. (W. Helck. Leiden: Brill 1967), chapter 2.</ref> | |||

| An important element of Set's mythology was his conflict with his brother or nephew, ], for the throne of Egypt. The contest between them is often violent but is also described as a legal judgment before the ], an assembled group of Egyptian deities, to decide who should ] the kingship. The judge in this trial may be Geb, who, as the father of Osiris and Set, held the throne before they did, or it may be the creator gods Ra or Atum, the originators of kingship.<ref>{{harvnb|Griffiths|1960|pp=58–59}}</ref> Other deities also take important roles: Thoth frequently acts as a conciliator in the dispute<ref>{{harvnb|Griffiths|1960|p=82}}</ref> or as an assistant to the divine judge, and in "Contendings", Isis uses her cunning and magical power to aid her son.<ref>{{harvnb|Assmann|2001|pp=135, 139–140}}</ref> | |||

| The rivalry of Horus and Set is portrayed in two contrasting ways. Both perspectives appear as early as the '']'', the earliest source of the myth. In some spells from these texts, Horus is the son of Osiris and nephew of Set, and the murder of Osiris is the major impetus for the conflict. The other tradition depicts Horus and Set as brothers.<ref>{{harvnb|Griffiths|1960|pp=12–16}}</ref> This incongruity persists in many of the subsequent sources, where the two gods may be called brothers or uncle and nephew at different points in the same text.<ref name="Assmann 134">{{harvnb|Assmann|2001|pp=134–135}}</ref> | |||

| These myths generally portray Osiris as a wise lord, king, and bringer of civilization, happily married to his sister, Isis. Set was envious of his brother, and he killed and dismembered Osiris. Isis reassembled Osiris' corpse and ] him. As the ] ], Osiris reigned over the afterworld as a king among deserving spirits of the dead. Osiris' son Horus was conceived by Isis with Osiris' corpse. Horus naturally became the enemy of Set, and the myths describe their conflicts. Some Egyptologists have reconstructed these as Set poking out Horus's left eye, and Horus retaliating by castrating Set. However the references to an eye and testicles appear more indirect, referring to the evil Set sexually abusing the young Horus, who protects himself by deflecting the seed of Set, which can be construed as the theft of Set's virile power.<ref>H. te Velde, ''Seth, God of Confusion: A Study of His Role in Egyptian Mythology and Religion'', Probleme der Ägyptologie, 6, G. E. van Baaren-Pape, transl. (W. Helck. Leiden: Brill 1967), pp. 32-41.</ref> | |||

| The divine struggle involves many episodes. "Contendings" describes the two gods appealing to various other deities to arbitrate the dispute and competing in different types of contests, such as racing in boats or fighting each other in the form of hippopotami, to determine a victor. In this account, Horus repeatedly defeats Set and is supported by most of the other deities.<ref>{{harvnb|Lichtheim|2006b|pp=214–223}}</ref> Yet the dispute drags on for eighty years, largely because the judge, the creator god, favors Set.<ref>{{harvnb|Hart|2005|p=73}}</ref> In late ritual texts, the conflict is characterized as a great battle involving the two deities' assembled followers.<ref>{{harvnb|Pinch|2004|p=83}}</ref> The strife in the divine realm extends beyond the two combatants. At one point Isis attempts to harpoon Set as he is locked in combat with her son, but she strikes Horus instead, who then cuts off her head in a fit of rage.<ref>{{harvnb|Lichtheim|2006b|pp=218–219}}</ref> Thoth replaces Isis's head with that of a cow; the story gives a ] for the cow-horn headdress that Isis commonly wears.{{sfn|Griffiths|2001|pp=188–190}} | |||

| It has also been suggested that the myth may reflect historical events. According to the Shabaka Stone, ] divided Egypt into two halves, giving ] (the desert south) to Set and ] (the region of the delta in the north) to Horus, in order to end their feud. However, according to the stone, in a later judgment Geb gave all Egypt to Horus. Interpreting this myth as a historical record would lead one to believe that Lower Egypt (Horus' land) conquered Upper Egypt (Set's land); but, in fact Upper Egypt conquered Lower Egypt. So the myth cannot be simply interpreted. | |||

| In a key episode in the conflict, Set sexually abuses Horus. Set's violation is partly meant to degrade his rival, but it also involves homosexual desire, in keeping with one of Set's major characteristics, his forceful, potent, and indiscriminate sexuality.<ref>{{harvnb|te Velde|1967|pp=55–56, 65}}</ref> In the earliest account of this episode, in a fragmentary Middle Kingdom papyrus, the sexual encounter begins when Set asks to have sex with Horus, who agrees on the condition that Set will give Horus some of his strength.<ref>{{harvnb|Griffiths|1960|p=42}}</ref> The encounter puts Horus in danger, because in Egyptian tradition semen is a potent and dangerous substance, akin to poison. According to some texts, Set's semen enters Horus's body and makes him ill, but in "Contendings", Horus thwarts Set by catching Set's semen in his hands. Isis retaliates by putting Horus's semen on lettuce-leaves that Set eats. Set's defeat becomes apparent when this semen appears on his forehead as a golden disk. He has been impregnated with his rival's seed and as a result "gives birth" to the disk. In "Contendings", Thoth takes the disk and places it on his own head; in earlier accounts, it is Thoth who is produced by this anomalous birth.<ref>{{harvnb|te Velde|1967|pp=38–39, 43–44}}</ref> | |||

| Several theories exist to explain the discrepancy. For instance, since both Horus and Set were worshipped in Upper Egypt prior to unification, perhaps the myth reflects a struggle within Upper Egypt prior to unification, in which a Horus-worshipping group subjugated a Set-worshipping group. What is known is that during the ], there was a period in which the King ]'s name or ] — which had been surmounted by a Horus falcon in the ] — was for a time surmounted by a Set animal, suggesting some kind of religious struggle. It was ended at the end of the dynasty by ], who surmounted his Serekh with both a falcon of Horus and a Set animal, indicating some kind of compromise had been reached. | |||

| Another important episode concerns mutilations that the combatants inflict upon each other: Horus injures or steals Set's testicles and Set damages or tears out one, or occasionally both, of Horus's eyes. Sometimes the eye is torn into pieces.<ref name="Pinch 82">{{harvnb|Pinch|2004|pp=82–83, 91}}</ref> Set's mutilation signifies a loss of virility and strength.<ref>{{harvnb|te Velde|1967|pp=42–43}}</ref> The removal of Horus's eye is even more important, for this stolen ] represents a wide variety of concepts in Egyptian religion. One of Horus's major roles is as a sky deity, and for this reason his right eye was said to be the sun and his left eye the moon. The theft or destruction of the eye of Horus is therefore equated with the darkening of the moon in the course of its cycle of phases, or during ]. Horus may take back his lost Eye, or other deities, including Isis, Thoth, and Hathor, may retrieve or heal it for him.<ref name="Pinch 82"/> Egyptologist Herman te Velde argues that the tradition about the lost testicles is a late variation on Set's loss of semen to Horus, and that the moon-like disk that emerges from Set's head after his impregnation is the Eye of Horus. If so, the episodes of mutilation and sexual abuse would form a single story, in which Set assaults Horus and loses semen to him, Horus retaliates and impregnates Set, and Set comes into possession of Horus's eye, when it appears on Set's head. Because Thoth is a moon deity in addition to his other functions, it would make sense, according to te Velde, for ] to emerge in the form of the Eye and step in to mediate between the feuding deities.<ref>{{harvnb|te Velde|1967|pp=43–46, 58}}</ref> | |||

| Regardless, once the two lands were united, Set and Horus were often shown together crowning the new ]s, as a symbol of their power over both Lower and Upper Egypt. Queens of the ] bore the title "She Who Sees Horus and Set." The Pyramid Texts present the pharaoh as a fusion of the two deities. Evidently, pharaohs believed that they balanced and reconciled competing cosmic principles. Eventually the dual-god Horus-Set appeared, combining features of both deities (as was common in Egyptian theology, the most familiar example being ]). | |||

| In any case, the restoration of the eye of Horus to wholeness represents the return of the moon to full brightness,{{sfn|Kaper|2001|pp=480–482}} the return of the kingship to Horus,<ref>{{harvnb|Griffiths|1960|p=29}}</ref> and many other aspects of '']''.<ref>{{harvnb|Pinch|2004|p=131}}</ref> Sometimes the restoration of Horus's eye is accompanied by the restoration of Set's testicles, so that both gods are made whole near the conclusion of their feud.<ref>{{harvnb|te Velde|1967|pp=56–57}}</ref> | |||

| Later Egyptians interpreted the myth of the conflict between Set and Osiris/Horus as an analogy for the struggle between the desert (represented by Set) and the fertilizing floods of the ] (Osiris/Horus). | |||

| ==Protector of Ra== | |||

| ] | ] in the underworld]] | ||

| Set was depicted standing on the prow of |

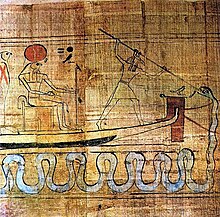

Set was depicted standing on the prow of ]'s ] defeating the dark ] ]. In some ] representations, such as in the ] ] at ], Set was represented in this role with a ]'s head, taking on the guise of ]. In the '']'', Set is described as having a key role in overcoming ]. | ||

| ==Set in the Second Intermediate and |

==Set in the Second Intermediate, Ramesside and later periods== | ||

| ] adore ] in the small temple at ].]] | |||

| During the ], a group of Asiatic foreign chiefs known as the ] (literally, "rulers of foreign lands") gained the rulership of Egypt, and ruled the ], from ]. They chose Set, originally Upper Egypt's chief god, the god of foreigners and the god they found most similar to their own chief god, as their patron, and then Set became worshiped as the chief god once again. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| During the ] (1650–1550 BCE), a group of Near Eastern peoples, known as the '']'' (literally, "''rulers of foreign lands''") gained control of Lower Egypt, and ruled the ], from ]. They chose Set, originally Upper Egypt's chief god, the god of foreigners and the god they found most similar to their own chief god, ], as their patron{{citation needed|date=July 2020}}. Set then became worshiped as the chief god once again. The Hyksos King ] is recorded as worshiping Set ], as described in the following passage:<ref>{{harvnb|Assmann|2008|pp=48, 151 n. 25}}, citing: {{harvnb|Goedicke|1986|pp=10–11}} and {{harvnb|Goldwasser|2006}}.</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|text=King Apophis chose for his Lord the god Seth. He did not worship any other deity in the whole land except Seth.{{efn|Translation from {{harvnb|Assmann|2008|p=48}}. Goedicke's translation: "And then King Apophis, ], was appointing for himself Sutekh as Lord. He never worked for any other god which is in this entire country except Sutekh.{{sfn|Goedicke|1986|p=31}} Goldwasser's translation: "Then, king Apophis l.p.h. adopted for himself Seth as lord, and he refused to serve any god that was in the entire land except Seth."{{sfn|Goldwasser|2006|p=129}}}}|author="]", ''Papyrus Sallier I'', 1.2–3 (British Museum No. 10185){{sfn|Gardiner|1932|p=84}}}} | |||

| ] argues that because the ancient Egyptians could never conceive of a "lonely" god lacking personality, Seth the desert god, who was worshiped on his own, represented a manifestation of evil.{{sfn|Assmann|2008|pp=47–48}} | |||

| The Hyksos King ] is recorded as worshiping Set in a monolatric way: | |||

| When ] overthrew the Hyksos and expelled them, in {{circa|1522 BCE}}, Egyptians' attitudes towards Asiatic foreigners became ], and royal propaganda discredited the period of Hyksos rule. The Set cult at Avaris flourished, nevertheless, and the Egyptian garrison of Ahmose stationed there became part of the priesthood of Set.{{citation needed|date=July 2020}} | |||

| {{quotation| chose for his Lord the god Seth. He didn't worship any other deity in the whole land except Seth.|''Papyrus Sallier 1 (Apophis and Sekenenre)'', 1.2-3, ed. Gardiner 1932}} | |||

| The founder of the ], ] came from a military family from Avaris with strong ties to the priesthood of Set. Several of the Ramesside kings were named after the god, most notably ] (literally, ''"man of Set"'') and ] (literally, ''"Set is strong"''). In addition, one of the garrisons of ] held Set as its patron deity, and Ramesses II erected the so-called "]" at ], commemorating the 400th anniversary of the Set cult in the Nile delta.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Nielsen |first1=Nicky |title=The Rise of the Ramessides: How a Military Family from the Nile Delta Founded One of Egypt's Most Celebrated Dynasties |url=https://www.arce.org/resource/rise-ramessides-how-military-family-nile-delta-founded-one-egypts-most-celebrated |website=American Research Center in Egypt |access-date=25 June 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ] argues that because the Ancient Egyptians could never conceive of a "lonely" god lacking personality, Seth the desert god, who was worshiped exclusively, represented a manifestation of evil.<ref>"''Of God and Gods''", Jan Assmann, p47-48, University of Wisconsin Press, 2008, ISBN 0-299-22550-X</ref> | |||

| In ], Set was commonly associated with the planet ].<ref> | |||

| When ] overthrew the Hyksos and expelled them from Egypt, Egyptian attitudes towards Asiatic foreigners became ], and royal propaganda discredited the period of Hyksos rule. Nonetheless, the Set cult at Avaris flourished, and the Egyptian garrison of Ahmose stationed there became part of the priesthood of Set. | |||

| {{cite journal | |||

| |last1=Parker |first1=R.A. | |||

| |year=1974 | |||

| |title=Ancient Egyptian astronomy | |||

| |journal=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London | |||

| |series=A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences | |||

| |volume=276 |issue=1257 |pages=51–65 | |||

| |jstor=74274 |doi=10.1098/rsta.1974.0009 | |||

| |bibcode=1974RSPTA.276...51P | |||

| |s2cid=120565237 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Set also became associated with foreign gods during the ], particularly in the delta. Set was identified by the Egyptians with the ] deity ], who, like Set, was a storm god, and the ] deity ], being worshipped together as "Seth-Baal".<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Keel |first1=Othmar |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NjYAWXO-jdAC&dq=Seth-Baal&pg=PA114 |title=Gods, Goddesses, And Images of God |last2=Uehlinger |first2=Christoph |date=1998-01-01 |publisher=Bloomsbury Academic |isbn=978-0-567-08591-7 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| The founder of the ], ] came from a military family from Avaris with strong ties to the priesthood of Set. Several of the Ramesside kings were named for Set, most notably ] (literally, "man of Set") and ] (literally, "Set is strong"). In addition, one of the garrisons of ] held Set as its patron deity, and Ramesses II erected the so-called ''Four Hundred Years' Stele'' at ], commemorating the 400 year anniversary of the Set cult in the Delta. | |||

| Additionally, Set is depicted in part of the ], a body of texts forming a ] used in ] during the fourth century CE.<ref></ref> | |||

| Set also became associated with foreign gods during the ], particularly in the Delta. Set was also identified by the Egyptians with the ] deity ], who was a storm god like Set. | |||

| == |

==The demonization of Set== | ||

| ] | |||

| Herman te Velde dates the demonization of Set to after Egypt's conquest by several foreign nations in the ] and ]s. Set, who had traditionally been the god of foreigners, thus also became associated with foreign oppressors, including the ] and ] empires.<ref>.H. te Velde, ''Seth, God of Confusion: A Study of His Role in Egyptian Mythology and Religion'', Probleme der Ägyptologie, 6 , G. E. van Baaren-Pape, transl. (W. Helck. Leiden: Brill 1967), pp. 138–140.</ref> It was during the time that Set was particularly vilified, and his defeat by Horus widely celebrated. | |||

| According to Herman te Velde, the demonization of Set took place after Egypt's conquest by several foreign nations in the ] and ]. Set, who had traditionally been the god of foreigners, thus also became associated with foreign oppressors, including the ] and ] empires.{{sfn|te Velde |1967 |pp=138–140}} It was during this time that Set was particularly vilified, and his defeat by Horus widely celebrated. | |||

| Set's negative aspects were emphasized during this period. Set was the killer of Osiris, having hacked Osiris' body into pieces and dispersed it so that he could not be ]. The Greeks later linked Set with ] because both were evil forces, storm deities, and sons of the Earth that attacked the main gods. | |||

| Set's negative aspects were emphasized during this period. Set was the killer of Osiris, having hacked Osiris' body into pieces and dispersed it so that he could not be ]. The Greeks would later associate Set with ] and ], a monstrous and evil force of raging nature (being the three of them depicted as donkey-like creatures, classifying their worshippers as ]).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Litwa |first=M. David |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1243261365 |title=The Evil Creator: Origins of an Early Christian Idea |date=2021 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-756643-5 |location=New York, NY |chapter=The Donkey Deity |oclc=1243261365 |quote=We see this tradition recounted by several writers. Around 200 BCE, a man called Mnaseas (an Alexandrian originally from what is now southern Turkey), told a story of an Idumean (southern Palestinian) who entered the Judean temple and tore off the golden head of a pack ass from the inner sanctuary. This head was evidently attached to a body, whether human or donkey. The reader would have understood that the Jews (secretly) worshiped Yahweh as a donkey in the Jerusalem temple, since gold was characteristically used for cult statues of gods. Egyptians knew only one other deity in ass-like form: Seth.}}</ref> | |||

| Nevertheless, throughout this period, in some outlying regions of Egypt Set was still regarded as the heroic chief deity. | |||

| Set and Typhon also had in common that both were sons of deities representing the Earth (] and Geb) who attacked the principal deities (Osiris for Set, ] for Typhon).{{citation needed|date=July 2020}} Nevertheless, throughout this period, in some outlying regions of Egypt, Set was still regarded as the heroic chief deity.{{citation needed|date=July 2020}} | |||

| ==Temples== | |||

| ] Dr. ] shot an episode called "The Birth of the Devil" in the "Out of Egypt" documentary series.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://docuwiki.net/index.php?title=Out_of_Egypt | title=Out of Egypt - DocuWiki }}</ref> In this documentary, the scientist describes the process of demonization of Set and the positioning of the it as absolute evil on the opposite side, in parallel with the transition to ] in different regions from Rome to India, where God began to be perceived as the representative of absolute goodness. | |||

| Set was worshipped at the ] of ] (Nubt near Naqada) and Ombos (Nubt near ]), at Oxyrhynchus in upper Egypt, and also in part of the ] area. | |||

| ==Set temples== | |||

| More specifically, Set was worshipped in the relatively large metropolitan (yet provincial) locale of ], especially during the Rammeside Period.<ref>cf. Sauneron, Priests of Ancient Egypt, p. 181</ref> There, Seth was honored with an important temple called the "House of Seth, Lord of Sepermeru." One of the epithets of this town was "gateway to the desert," which fits well with Set's role as a deity of the frontier regions of ancient Egypt. At Sepermeru, Set's temple enclosure included a small secondary shrine called "The House of Seth, Powerful-Is-His-Mighty-Arm," and Ramesses II himself built (or modified) a second land-owning temple for Nephthys, called "The House of Nephthys of Ramesses-Meriamun.".<ref>Katary, Land Tenure in the Rammesside Period, 1989 ,p. 216</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Set was worshipped at the ] of ] (Nubt near Naqada) and Ombos (Nubt near ]), at ] in Middle Egypt, and also in part of the ] area. | |||

| More specifically, Set was worshipped in the relatively large metropolitan (yet provincial) locale of ], especially during the Ramesside Period.<ref>{{cite book |author=Sauneron |title=Priests of Ancient Egypt |page=181}}{{full citation needed|date=January 2021}}</ref> There, Seth was honored with an important temple called the "House of Seth, Lord of Sepermeru". One of the epithets of this town was "gateway to the desert", which fits well with Set's role as a deity of the frontier regions of ancient Egypt. At Sepermeru, Set's temple enclosure included a small secondary shrine called "The House of Seth, Powerful-Is-His-Mighty-Arm", and Ramesses II himself built (or modified) a second land-owning temple for Nephthys, called "The House of Nephthys of Ramesses-Meriamun".{{sfn|Katary|1989|p=216}} | |||

| There is no question, however, that the two temples of Seth and Nephthys in Sepermeru were under separate administration, each with its own holdings and prophets.<ref>Katary, Land Tenure, pg. 220</ref> Moreover, another moderately sized temple of Seth is noted for the nearby town of Pi-Wayna.<ref>Katary, Land Tenure, p.216</ref> The close association of Seth temples with temples of Nephthys in key outskirt-towns of this ''milieu'' is also reflected in the likelihood that there existed another "House of Seth" and another "House of Nephthys" in the town of Su, at the entrance to the Fayyum.<ref>Gardiner, Papyrus Wilbour Commentary, S28, pp. 127-128</ref> | |||

| The two temples of Seth and Nephthys in Sepermeru were under separate administration, each with its own holdings and prophets.{{sfn|Katary|1989|p=220}} Moreover, another moderately sized temple of Seth is noted for the nearby town of Pi-Wayna.{{sfn|Katary|1989|p=216}} The close association of Seth temples with temples of Nephthys in key outskirt-towns of this ''milieu'' is also reflected in the likelihood that there existed another "House of Seth" and another "House of Nephthys" in the town of Su, at the entrance to the Fayyum.<ref>{{cite book |editor=Gardiner |title=Papyrus Wilbour Commentary |volume=S28 |pages=127–128}}{{full citation needed|date=January 2021}}</ref> | |||

| Perhaps most intriguing in terms of the pre-Twentieth Dynasty connections between temples of Set and nearby temples of his consort Nephthys is the evidence of ], which preserves a most irritable complaint lodged by one Pra'em-hab, Prophet of the "House of Seth" in the now-lost town of Punodjem ("The Sweet Place"). In the text of Papyrus Bologna, the harried Pra'em-hab laments undue taxation for his own temple (The House of Seth) and goes on to lament that he is also saddled with responsibility for: "the ship, and I am likewise also responsible for the House of Nephthys, along with the remaining heap of district temples".<ref>P. Bologna 1094, 5,8-7, 1</ref> | |||

| ] preserves a most irritable complaint lodged by one Pra'em-hab, Prophet of the "House of Seth" in the now-lost town of Punodjem ("The Sweet Place"). In the text of Papyrus Bologna, the harried Pra'em-hab laments undue taxation for his own temple (The House of Seth) and goes on to lament that he is also saddled with responsibility for: ''"The ship, and I am likewise also responsible for the House of Nephthys, along with the remaining heap of district temples"''.<ref>Papyrus Bologna 1094, 5,8–7, 1 {{full citation needed|date=January 2021}}</ref> | |||

| It is unfortunate, perhaps, that we have no means of knowing the particular theologies of the closely connected Set and Nephthys temples in these districts—it would be interesting to learn, for example, the religious tone of temples of Nephthys located in such proximity to those of Seth, especially given the seemingly contrary Osirian loyalties of Seth's consort-goddess. When, by the ], the "demonization" of Seth was ostensibly inaugurated, Seth was either eradicated or increasingly pushed to the outskirts, Nephthys flourished as part of the usual Osirian pantheon throughout Egypt, even obtaining a Late Period status as tutelary goddess of her own Nome (UU Nome VII, "Hwt-Sekhem"/Diospolis Parva) and as the chief goddess of the Mansion of the Sistrum in that district.<ref>Sauneron, Beitrage Bf. 6, 46</ref><ref>C. Traunecker, Le temple d'El-Qal'a. Relevés des scènes et des textes. I' Sanctuaire central. Sanctuaire nord. Salle des offrandes 1 à 112</ref><ref>.P. Wilson, 'A Ptolemaic Lexikon: A Lexicographical Study of the Texts in the Temple of Edfu', OLA 78, 1997</ref><ref>P. Collombert, "Les stèles tardives de Hout-sekhem (Hout-sekhem et le septième nome de Haute-Égypte II)", RdE 48 (1997), pp. 15-70, pl. I-VII</ref> | |||

| Nothing is known about the particular theologies of the closely connected Set and Nephthys temples in these districts — for example, the religious tone of temples of Nephthys located in such proximity to those of Seth, especially given the seemingly contrary Osirian loyalties of Seth's consort-goddess. When, by the ], the "demonization" of Seth was ostensibly inaugurated, Seth was either eradicated or increasingly pushed to the outskirts, Nephthys flourished as part of the usual Osirian pantheon throughout Egypt, even obtaining a Late Period status as tutelary goddess of her own Nome (UU Nome VII, "Hwt-Sekhem"/Diospolis Parva) and as the chief goddess of the Mansion of the Sistrum in that district.<ref>Sauneron, Beitrage Bf. 6, 46 {{full citation needed|date=January 2021}}</ref><ref> | |||

| Yet, it is perhaps most telling that Seth's cult persisted with astonishing potency even into the latter days of ancient Egyptian religion, in outlying (but important) places like Kharga, Dakhlah, Deir el-Hagar, Mut, Kellis, etc. Indeed, in these places, Seth was considered "Lord of the Oasis/Town" and Nephthys was likewise venerated as "Mistress of the Oasis" at Seth's side, in his temples<ref>Essays on Ancient Egypt in Honor of Herman te Velde, pp. 234-237</ref> (esp. the dedication of a Nephthys-cult statue). Meanwhile, Nephthys was also venerated as "Mistress" in the Osirian temples of these districts, as part of the specifically Osirian college.<ref>Essays, 234-237</ref> It would appear that the ancient Egyptians in these locales had little problem with the paradoxical dualities inherent in venerating Seth and Nephthys as juxtaposed against Osiris, Isis & Nephthys. Further study of the enormously important role of Seth in ancient Egyptian religion (particularly after the Twentieth Dynasty) is imperative. | |||

| {{cite report | |||

| |first1=L. |last1=Pantalacci | |||

| |first2=C. |last2=Traunecker | |||

| |year=1990 | |||

| |title=Le temple d'El-Qal'a. Relevés des scènes et des textes. I' Sanctuaire central. Sanctuaire nord. Salle des offrandes 1 à 112 | |||

| |publisher=Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale | |||

| |place=Cairo, Egypt | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref><ref> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |first=P. |last=Wilson | |||

| |year=1997 | |||

| |title=A Ptolemaic Lexicon: A lexicographical study of the texts in the Temple of Edfu | |||

| |series=OLA 78 | |||

| |place=Leuven | |||

| |isbn=978-90-6831-933-0 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref><ref> | |||

| {{cite journal | |||

| |first=P. |last=Collombert | |||

| |year=1997 | |||

| |title=Hout-sekhem et le septième nome de Haute Égypte II: Les stèles tardives (Pl. I–VII) | |||

| |journal=Revue d'Égyptologie | |||

| |volume=48 |pages=15–70 | |||

| |doi=10.2143/RE.48.0.2003683 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Seth's cult persisted even into the latter days of ancient Egyptian religion, in outlying but important places like Kharga, Dakhlah, Deir el-Hagar, Mut, and Kellis. In these places, Seth was considered ''"Lord of the Oasis / Town"'' and Nephthys was likewise venerated as "Mistress of the Oasis" at Seth's side, in his temples{{sfn|Kaper|1997b|pp=234–237}} (esp. the dedication of a Nephthys-cult statue). Meanwhile, Nephthys was also venerated as "Mistress" in the Osirian temples of these districts as part of the specifically Osirian college.{{sfn|Kaper|1997b|pp=234–237}} It would appear that the ancient Egyptians in these locales had little problem with the paradoxical dualities inherent in venerating Seth and Nephthys, as juxtaposed against Osiris, Isis, and Nephthys. | |||

| The power of Seth's cult in the mighty (yet outlying) city of Avaris from the Second Intermediate Period through the Ramesside Period cannot be denied. There he reigned supreme as a deity both at odds and in league with threatening foreign powers, and in this case, his chief consort-goddesses were the Phoenicians Anat and Astarte, with Nephthys merely one of the harem.{{citation needed|date=September 2012}} | |||

| ==In modern religion== | ==In modern religion== | ||

| {{main| |

{{main|Kemetism|Temple of Set|Sethian Liberation Movement}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ==In popular culture== | ==In popular culture== | ||

| {{ |

{{in popular culture|date=July 2024}} | ||

| In the television series '']'', Set (using the name Sutekh and portrayed by ]) is depicted as an alien entity bent on destroying all life. He first appears in the 1975 serial '']'', where he schemes to escape an Egyptian pyramid he has been imprisoned in millennia ago by Horus. Sutekh returned after nearly 50 years in the ] two-part finale "]" / "]" as the God of Death in the Pantheon.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.radiotimes.com/tv/sci-fi/sutekh-doctor-who-one-who-waits/ |title= Who is Sutekh? The identity of Doctor Who's One Who Waits Explained |last= Jeffrey |first=Morgan |date= 15 June 2024|website= Radio Times |access-date=June 15, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| In the role-playing game '']'', the ancient Egyptian deity Set is depicted as an antediluvian vampire, believed to be one of the oldest undead beings. Revered as the founder of the enigmatic Followers of Set (now known as The Ministry in the game's fifth edition). Imprisoned in torpor, Set remains a focal point for his followers who strive to rouse him from his slumber. He commands powers entwined with manipulation, darkness, and serpentine subtlety, epitomized by his unique Discipline, Serpentis, dedicated to the mastery of serpents. | |||

| In the 1992 Nintendo Entertainment System video game '']'', the villain's public persona is that of "Sutekh", a criminal underboss who unifies the gangs of the fictitious Metro City. In line with the idea of Sutekh, of Egyptian mythology, the Sutekh in the video game reigns supreme over all of the violence in the city. Of particular note, in Egyptian mythology, Sutekh is also the god of foreigners. In the Nightshade video game, its villain is not of Egyptian descent, but instead a man by the name of Waldo P. Schmeer who is a historian obsessed with Egyptian lore. Set is also a minor villain in other video games, including '']'' (1995, 1996)<ref>{{cite web|url=https://steamcommunity.com/sharedfiles/filedetails/?id=3350694739|title=Encyclopedia Diabolica of Killing Time: Resurrected|author=Shiki-Kui|date=18 October 2024|access-date=13 December 2024}}</ref> and '']'' (1996).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.whipassgaming.com/genesisreviews/powerslave/powerslaveguide.htm|title=PowerSlave Walkthrough|first=David|last=Ruchala|access-date=15 December 2024}}</ref> | |||

| Sutekh is an antagonist in some films and other material in the '']'' universe. Sutekh is portrayed as the other worldly owner of the secret of life, which animates the eponymous puppets, and stalks anyone who steals it. | |||

| Ahead of the release of their 25th studio album, '']'', Australian band ] released the album's first three songs.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Rettig |first=James |date=2023-10-03 |title=King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard – "Theia / The Silver Cord / Set" |url=https://www.stereogum.com/2237851/king-gizzard-the-lizard-wizard-theia-the-silver-cord-set/music/ |website=Stereogum}}</ref> The third of these, titled "Set", describes Set killing Osiris and his subsequent conflict with Horus. | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| *] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{noteslist}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{reflist|refs= | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| <ref name=Sayce-nd-Hittites> | |||

| ==Bibliography== | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| *Allen, James P. 2004. "Theology, Theodicy, Philosophy: Egypt." In Sarah Iles Johnston, ed. ''Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide.'' Cambridge: ]. ISBN 0-674-01517-7. | |||

| |first=Archibald H. |last=Sayce | |||

| *Bickel, Susanne. 2004. "Myths and Sacred Narratives: Egypt." In Sarah Iles Johnston, ed. ''Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide.'' Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01517-7. | |||

| |title=The Hittites: The story of a forgotten empire | |||

| *Cohn, Norman. 1995. ''Cosmos, Chaos and the World to Come: The Ancient Roots of Apocalyptic Faith.'' New Haven: ]. ISBN 0-300-09088-9 (1999 paperback reprint). | |||

| }} | |||

| *Ions, Veronica. 1982. "Egyptian Mythology." New York: Peter Bedrick Books. ISBN 0-87226-249-9. | |||

| </ref>{{full citation needed|date=September 2021|reason=year, publisher, ISBN or other ID}} | |||

| *Kaper, Olaf Ernst. 1997. ''Temples and Gods in Roman Dakhlah: Studies in the Indigenous Cults of an Egyptian Oasis''. Doctoral dissertation; Groningen: ], Faculteit der Letteren. | |||

| *Kaper, Olaf Ernst. 1997. "The Statue of Penbast: On the Cult of Seth in the Dakhlah Oasis". In '''', edited by Jacobus van Dijk. Egyptological Memoirs 1. Groningen: Styx Publications. 231–241, ISBN 90-5693-014-1. | |||

| <ref name=Budge-nd-HstEgy> | |||

| *Lesko, Leonard H. 1987. "Seth." In The Encyclopedia of Religion, edited by Mircea Eliade, 2nd edition (2005) edited by Lindsay Jones. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Thomson-Gale. ISBN 0-02-865733-0. | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| *Osing, Jürgen. 1985. "Seth in Dachla und Charga." ''Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo'' 41:229–233. | |||

| |first=E.A. Wallis |last=Budge | |||

| *Quirke, Stephen G. J. 1992. ''Ancient Egyptian Religion''. New York: Dover Publications, inc., ISBN 0-486-27427-6 (1993 reprint). | |||

| |title=A History of Egypt from the End of the Neolithic Period to the Death of Cleopatra VII B.C. 30 | |||

| *Stoyanov, Yuri. 2000. ''The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy''. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08253-3 (paperback). | |||

| }} | |||

| *te Velde, Herman. 1967. ''Seth, God of Confusion: A Study of His Role in Egyptian Mythology and Religion''. 2nd ed. Probleme der Ägyptologie 6. Leiden: ], ISBN 90-04-05402-2. | |||

| </ref>{{full citation needed|date=September 2021|reason=year, publisher, ISBN or other ID}} | |||

| }} | |||

| ==Sources== | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| |last=Allen |first=James P. | |||

| |year=2004 | |||

| |chapter=Theology, theodicy, philosophy: Egypt | |||

| |editor-first=Sarah Iles |editor-last=Johnston | |||

| |title=Religions of the Ancient World: A guide | |||

| |place=Cambridge, Massachusetts | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |isbn=978-0-674-01517-3 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book|last=Assmann|first=Jan|author-link=Jan Assmann|others=Translated by David Lorton|title=The Search for God in Ancient Egypt|publisher=]|year=2001|orig-year=German edition 1984|isbn=978-0-8014-3786-1|url=https://archive.org/details/searchforgodinan00assm}} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| |first=Jan |last=Assmann | |||

| |year=2008 | |||

| |title=Of God and Gods: Egypt, Israel, and the rise of monotheism | |||

| |publisher=University of Wisconsin Press | |||

| |isbn=978-0-299-22550-6 | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| |last=Bickel |first=Susanne | |||

| |year=2004 | |||

| |chapter=Myths and sacred narratives: Egypt | |||

| |editor-first=Sarah Iles |editor-last=Johnston | |||

| |title=Religions of the Ancient World: A guide | |||

| |place=Cambridge, Massachusetts | |||

| |publisher=Harvard University Press | |||

| |isbn=978-0-674-01517-3 | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| |last=Cohn |first=Norman | |||

| |orig-year=1995 |year=1999 | |||

| |edition=paperback reprint | |||

| |title=Cosmos, Chaos and the World to Come: The ancient roots of apocalyptic faith | |||

| |place=New Haven, CT | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |isbn=978-0-300-09088-8 | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| |title=Late-Egyptian Stories | |||

| |chapter=The Quarrel of Apophis and Seḳnentēr |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/GardinerLateEgyptianStoriesPdf/page/n185/mode/1up | |||

| |page=85 | |||

| |editor-last=Gardiner |editor-first=Alan H. | |||

| |series=Bibliotheca Aegptiaca |volume=I | |||

| |year=1932 |location=Bruxelles |publisher=Fondation Egyptologique Reine Elisabeth}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Goedicke |first1=Hans |title=The Quarrel of Apophis and Seqenenrec |date=1986 |publisher=Van Siclen |location=San Antonio |isbn=0-933175-06-X}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Goldwasser |first1=Orly |editor1-last=Czerny |editor1-first=Ernst |editor2-last=Hein |editor2-first=Irmgard |editor3-last=Hunger |editor3-first=Hermann |editor4-last=Melman |editor4-first=Dagmar |editor5-last=Schwab |editor5-first=Angela |title=Timelines: Studies in Honour of Manfred Bietak |series=Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta |volume=149/II |date=2006 |publisher=Peeters |location=Leuven |isbn=978-90-429-1730-9 |pages=129–133 |chapter=King Apophis of Avaris and the Emergence of Monotheism}} | |||

| *{{cite book|last=Griffiths|first=J. Gwyn|author-link=J. Gwyn Griffiths|title=The Conflict of Horus and Seth|year=1960|publisher=Liverpool University Press}} | |||

| *{{cite book|last=Griffiths |first=J. Gwyn |chapter=Osiris |editor-last=Redford|editor-first=Donald B. |editor-link=Donald B. Redford |title=The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt |volume=2 |pages=615–619 |year=2001|publisher=Oxford University Press| isbn=978-0-19-510234-5 }} | |||

| *{{cite book|last=Hart|first=George|title=The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, Second Edition|year=2005|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-0-203-02362-4}} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| |last=Ions |first=Veronica | |||

| |year=1982 | |||

| |title=Egyptian Mythology | |||

| |place=New York, NY | |||

| |publisher=Peter Bedrick Books | |||

| |isbn=978-0-87226-249-2 | |||

| |url-access=registration | |||

| |via=archive.org | |||

| |url=https://archive.org/details/egyptianmytholog00vero_0 | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{cite thesis | |||

| |last=Kaper |first=Olaf Ernst | |||

| |year=1997a | |||

| |title=Temples and Gods in Roman Dakhlah: Studies in the indigenous cults of an Egyptian oasis | |||

| |type=doctoral dissertation | |||

| |place=Groningen, DE | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |department=Faculteit der Letteren | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book|last=Kaper |first=Olaf E. |chapter=Myths: Lunar Cycle |editor-last=Redford|editor-first=Donald B. |title=The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt |volume=2 |pages=480–482 |year=2001|publisher=Oxford University Press| isbn=978-0-19-510234-5 }} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| |last=Kaper |first=Olaf Ernst | |||

| |year=1997b | |||

| |chapter=The Statue of Penbast: On the cult of Seth in the Dakhlah oasis | |||

| |editor-first=Jacobus |editor-last=van Dijk | |||

| |title=Essays on Ancient Egypt in Honour of Herman te Velde | |||

| |series=Egyptological Memoirs |volume=1 |pages=231–241 | |||

| |place=Groningen, DE | |||

| |publisher=Styx Publications | |||

| |isbn=978-90-5693-014-1 | |||

| |via=Google Books | |||

| |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dv_2slpteq4C&pg=PA231 | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| |last=Katary |first=Sally L.D. | |||

| |year=1989 | |||

| |title=Land Tenure in the Rammesside Period | |||

| |publisher=Kegan Paul International | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| |last=Lesko |first=Leonard H. | |||

| |year=2005 | |||

| |chapter=Seth | |||

| |title=The Encyclopedia of Religion |edition=2nd | |||

| |editor-first=Lindsay |editor-last=Jones | |||

| |others= | |||

| |place=Farmington Hills, Michigan | |||

| |publisher=Thomson-Gale | |||

| |isbn=978-0-02-865733-2 | |||

| |chapter-url-access=registration | |||

| |via=archive.org | |||

| |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofre0000unse_v8f2 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book|last=Lichtheim|first=Miriam|author-link=Miriam Lichtheim |title=Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume II: The New Kingdom|year=2006b|orig-year=First edition 1976|publisher=University of California Press| isbn=978-0-520-24843-4}} | |||

| * {{cite report | |||

| |last=Osing |first=Jürgen | |||

| |year=1985 | |||

| |title=Seth in Dachla und Charga | |||

| |series=Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts | |||

| |volume=41 |pages=229–233 | |||

| |publisher=Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts | |||

| |department=Abteilung Kairo | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book|last=Pinch|first=Geraldine|author-link=Geraldine Pinch|title=Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt|year=2004|orig-year=First edition 2002|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-517024-5}} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| |last=Quirke |first=Stephen G.J. | |||

| |year=1992 |orig-year=1993 | |||

| |title=Ancient Egyptian Religion | |||

| |edition=reprint | |||

| |place=New York, NY | |||

| |publisher=Dover Publications | |||

| |isbn=978-0-486-27427-0 | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| |last=Stoyanov |first=Yuri | |||

| |year=2000 | |||

| |title=The Other God: Dualist religions from antiquity to the Cathar heresy | |||

| |place=New Haven, CT | |||

| |publisher=Yale University Press | |||

| |isbn=978-0-300-08253-1 | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| |last=te Velde |first=Herman | |||

| |year=1967 | |||

| |title=Seth, God of Confusion: A study of his role in Egyptian mythology and religion |edition=2nd | |||

| |series=Probleme der Ägyptologie |volume=6 | |||

| |place=Leiden, NL | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |isbn=978-90-04-05402-8 | |||

| |translator-first=G.E. |translator-last=van Baaren-Pape | |||

| }} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Commons category|Seth}} | {{Commons category|Seth}} | ||

| * {{cite web | |||

| *: ''Hibis Temple representations of Sutekh as Horus'' | |||

| |title=Le temple d'Hibis, oasis de Khargha | |||

| |trans-title=Hibis Temple Khargha oasis | |||

| |website=alain.guilleux.free.fr | |||

| |url=http://alain.guilleux.free.fr/khargha_hibis/khargha_temple_hibis.html | |||

| }} – representations of Sutekh as Horus | |||

| {{Ancient Egyptian religion footer}} | {{Ancient Egyptian religion footer}} | ||

| {{Ancient Egypt topics}} | {{Ancient Egypt topics}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 06:28, 9 January 2025

Egyptian god of the desert, storms, violence, and foreigners This article is about the Egyptian deity. For the third son of Adam and Eve, see Seth. For other uses, see Set (disambiguation) and Seth (disambiguation).| Set | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Name in hieroglyphs |

| ||||

| Major cult center | Ombos, Avaris, Sepermeru | ||||

| Symbol | Was-sceptre, Set animal | ||||

| Genealogy | |||||

| Parents | Geb, Nut | ||||

| Siblings | Osiris, Isis, Nephthys, Horus the Elder | ||||

| Consort | Nephthys, Neith, Anat, and Astarte | ||||

| Offspring | Anubis (disputed), Sobek (in some accounts) and Maga | ||||

| Equivalents | |||||

| Greek | Typhon | ||||

Set (/sɛt/; Egyptological: Sutekh - swtẖ ~ stẖ or: Seth /sɛθ/) is a god of deserts, storms, disorder, violence, and foreigners in ancient Egyptian religion. In Ancient Greek, the god's name is given as Sēth (Σήθ). Set had a positive role where he accompanies Ra on his barque to repel Apep (Apophis), the serpent of Chaos. Set had a vital role as a reconciled combatant. He was lord of the Red Land (desert), where he was the balance to Horus' role as lord of the Black Land (fertile land).

In the Osiris myth, the most important Egyptian myth, Set is portrayed as the usurper who murdered and mutilated his own brother, Osiris. Osiris's sister-wife, Isis, reassembled his corpse and resurrected her dead brother-husband with the help of the goddess Nephthys. The resurrection lasted long enough to conceive his son and heir, Horus. Horus sought revenge upon Set, and many of the ancient Egyptian myths describe their conflicts.

Family

Set is the son of Geb, the Earth, and Nut, the Sky; his siblings are Osiris, Isis, and Nephthys. He married Nephthys and had had relationships with the foreign goddesses Anat and Astarte in some accounts. Though it has commonly been assumed that Set was married to Nephthys and therefore must have been considered the father of Anubis, some Egyptologists, such as Herman te Velde, have heavily doubted whether Set was ever regarded as Anubis's father in ancient Egyptian religion. From these relationships is said to be born a crocodile deity called Maga.

Name origin

The meaning of the name Set is unknown, but it is thought to have been originally pronounced *sūtiẖ based on spellings of his name in Egyptian hieroglyphs as stẖ and swtẖ. The Late Egyptian spelling stš reflects the palatalization of ẖ while the eventual loss of the final consonant is recorded in spellings like swtj. The Coptic form of the name, ⲥⲏⲧ Sēt, is the basis for the English vocalization.

Set animal

Main article: Set animal

or

or

| |||||||||||

in hieroglyphs | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

In art, Set is usually depicted as an enigmatic creature referred to by Egyptologists as the Set animal, a beast not identified with any known animal, although it could be seen as resembling a Saluki, an aardvark, an African wild dog, a donkey, a hyena, a jackal, a pig, an antelope, a giraffe, or a fennec fox. The animal has a downward curving snout; long ears with squared-off ends; a thin, forked tail with sprouted fur tufts in an inverted arrow shape; and a slender canine body. Sometimes, Set is depicted as a human with the distinctive head. Some early Egyptologists proposed that it was a stylised representation of the giraffe, owing to the large flat-topped "horns" which correspond to a giraffe's ossicones. The Egyptians themselves, however, used distinct depictions for the giraffe and the Set animal. During the Late Period, Set is usually depicted as a donkey or as a man with the head of a donkey, and in the Book of the Faiyum, Set is depicted with a flamingo head.

The earliest representations of what might be the Set animal comes from a tomb dating to the Amratian culture ("Naqada I") of prehistoric Egypt (3790–3500 BCE), although this identification is uncertain. If these are ruled out, then the earliest Set animal appears on a ceremonial macehead of Scorpion II, a ruler of the Naqada III phase. The head and the forked tail of the Set animal are clearly present on the mace.

Conflict of Horus and Set

An important element of Set's mythology was his conflict with his brother or nephew, Horus, for the throne of Egypt. The contest between them is often violent but is also described as a legal judgment before the Ennead, an assembled group of Egyptian deities, to decide who should inherit the kingship. The judge in this trial may be Geb, who, as the father of Osiris and Set, held the throne before they did, or it may be the creator gods Ra or Atum, the originators of kingship. Other deities also take important roles: Thoth frequently acts as a conciliator in the dispute or as an assistant to the divine judge, and in "Contendings", Isis uses her cunning and magical power to aid her son.

The rivalry of Horus and Set is portrayed in two contrasting ways. Both perspectives appear as early as the Pyramid Texts, the earliest source of the myth. In some spells from these texts, Horus is the son of Osiris and nephew of Set, and the murder of Osiris is the major impetus for the conflict. The other tradition depicts Horus and Set as brothers. This incongruity persists in many of the subsequent sources, where the two gods may be called brothers or uncle and nephew at different points in the same text.

The divine struggle involves many episodes. "Contendings" describes the two gods appealing to various other deities to arbitrate the dispute and competing in different types of contests, such as racing in boats or fighting each other in the form of hippopotami, to determine a victor. In this account, Horus repeatedly defeats Set and is supported by most of the other deities. Yet the dispute drags on for eighty years, largely because the judge, the creator god, favors Set. In late ritual texts, the conflict is characterized as a great battle involving the two deities' assembled followers. The strife in the divine realm extends beyond the two combatants. At one point Isis attempts to harpoon Set as he is locked in combat with her son, but she strikes Horus instead, who then cuts off her head in a fit of rage. Thoth replaces Isis's head with that of a cow; the story gives a mythical origin for the cow-horn headdress that Isis commonly wears.

In a key episode in the conflict, Set sexually abuses Horus. Set's violation is partly meant to degrade his rival, but it also involves homosexual desire, in keeping with one of Set's major characteristics, his forceful, potent, and indiscriminate sexuality. In the earliest account of this episode, in a fragmentary Middle Kingdom papyrus, the sexual encounter begins when Set asks to have sex with Horus, who agrees on the condition that Set will give Horus some of his strength. The encounter puts Horus in danger, because in Egyptian tradition semen is a potent and dangerous substance, akin to poison. According to some texts, Set's semen enters Horus's body and makes him ill, but in "Contendings", Horus thwarts Set by catching Set's semen in his hands. Isis retaliates by putting Horus's semen on lettuce-leaves that Set eats. Set's defeat becomes apparent when this semen appears on his forehead as a golden disk. He has been impregnated with his rival's seed and as a result "gives birth" to the disk. In "Contendings", Thoth takes the disk and places it on his own head; in earlier accounts, it is Thoth who is produced by this anomalous birth.

Another important episode concerns mutilations that the combatants inflict upon each other: Horus injures or steals Set's testicles and Set damages or tears out one, or occasionally both, of Horus's eyes. Sometimes the eye is torn into pieces. Set's mutilation signifies a loss of virility and strength. The removal of Horus's eye is even more important, for this stolen eye of Horus represents a wide variety of concepts in Egyptian religion. One of Horus's major roles is as a sky deity, and for this reason his right eye was said to be the sun and his left eye the moon. The theft or destruction of the eye of Horus is therefore equated with the darkening of the moon in the course of its cycle of phases, or during eclipses. Horus may take back his lost Eye, or other deities, including Isis, Thoth, and Hathor, may retrieve or heal it for him. Egyptologist Herman te Velde argues that the tradition about the lost testicles is a late variation on Set's loss of semen to Horus, and that the moon-like disk that emerges from Set's head after his impregnation is the Eye of Horus. If so, the episodes of mutilation and sexual abuse would form a single story, in which Set assaults Horus and loses semen to him, Horus retaliates and impregnates Set, and Set comes into possession of Horus's eye, when it appears on Set's head. Because Thoth is a moon deity in addition to his other functions, it would make sense, according to te Velde, for Thoth to emerge in the form of the Eye and step in to mediate between the feuding deities.

In any case, the restoration of the eye of Horus to wholeness represents the return of the moon to full brightness, the return of the kingship to Horus, and many other aspects of ma'at. Sometimes the restoration of Horus's eye is accompanied by the restoration of Set's testicles, so that both gods are made whole near the conclusion of their feud.

Protector of Ra

Set was depicted standing on the prow of Ra's barge defeating the dark serpent Apep. In some Late Period representations, such as in the Persian Period Temple of Hibis at Khargah, Set was represented in this role with a falcon's head, taking on the guise of Horus. In the Amduat, Set is described as having a key role in overcoming Apep.

Set in the Second Intermediate, Ramesside and later periods

During the Second Intermediate Period (1650–1550 BCE), a group of Near Eastern peoples, known as the Hyksos (literally, "rulers of foreign lands") gained control of Lower Egypt, and ruled the Nile Delta, from Avaris. They chose Set, originally Upper Egypt's chief god, the god of foreigners and the god they found most similar to their own chief god, Hadad, as their patron. Set then became worshiped as the chief god once again. The Hyksos King Apophis is recorded as worshiping Set exclusively, as described in the following passage:

King Apophis chose for his Lord the god Seth. He did not worship any other deity in the whole land except Seth.

— "The Quarrel of Apophis and Seqenenre", Papyrus Sallier I, 1.2–3 (British Museum No. 10185)

Jan Assmann argues that because the ancient Egyptians could never conceive of a "lonely" god lacking personality, Seth the desert god, who was worshiped on his own, represented a manifestation of evil.

When Ahmose I overthrew the Hyksos and expelled them, in c. 1522 BCE, Egyptians' attitudes towards Asiatic foreigners became xenophobic, and royal propaganda discredited the period of Hyksos rule. The Set cult at Avaris flourished, nevertheless, and the Egyptian garrison of Ahmose stationed there became part of the priesthood of Set.

The founder of the Nineteenth Dynasty, Ramesses I came from a military family from Avaris with strong ties to the priesthood of Set. Several of the Ramesside kings were named after the god, most notably Seti I (literally, "man of Set") and Setnakht (literally, "Set is strong"). In addition, one of the garrisons of Ramesses II held Set as its patron deity, and Ramesses II erected the so-called "Year 400 Stela" at Pi-Ramesses, commemorating the 400th anniversary of the Set cult in the Nile delta.

In ancient Egyptian astronomy, Set was commonly associated with the planet Mercury.

Set also became associated with foreign gods during the New Kingdom, particularly in the delta. Set was identified by the Egyptians with the Hittite deity Teshub, who, like Set, was a storm god, and the Canaanite deity Baal, being worshipped together as "Seth-Baal".

Additionally, Set is depicted in part of the Greek Magical Papyri, a body of texts forming a grimoire used in Greco-Roman magic during the fourth century CE.

The demonization of Set

According to Herman te Velde, the demonization of Set took place after Egypt's conquest by several foreign nations in the Third Intermediate and Late Periods. Set, who had traditionally been the god of foreigners, thus also became associated with foreign oppressors, including the Kushite and Persian empires. It was during this time that Set was particularly vilified, and his defeat by Horus widely celebrated.

Set's negative aspects were emphasized during this period. Set was the killer of Osiris, having hacked Osiris' body into pieces and dispersed it so that he could not be resurrected. The Greeks would later associate Set with Typhon and Yahweh, a monstrous and evil force of raging nature (being the three of them depicted as donkey-like creatures, classifying their worshippers as onolatrists).

Set and Typhon also had in common that both were sons of deities representing the Earth (Gaia and Geb) who attacked the principal deities (Osiris for Set, Zeus for Typhon). Nevertheless, throughout this period, in some outlying regions of Egypt, Set was still regarded as the heroic chief deity.

Ancient Egyptologist Dr. Kara Cooney shot an episode called "The Birth of the Devil" in the "Out of Egypt" documentary series. In this documentary, the scientist describes the process of demonization of Set and the positioning of the it as absolute evil on the opposite side, in parallel with the transition to monotheism in different regions from Rome to India, where God began to be perceived as the representative of absolute goodness.

Set temples

Set was worshipped at the temples of Ombos (Nubt near Naqada) and Ombos (Nubt near Kom Ombo), at Oxyrhynchus in Middle Egypt, and also in part of the Fayyum area.

More specifically, Set was worshipped in the relatively large metropolitan (yet provincial) locale of Sepermeru, especially during the Ramesside Period. There, Seth was honored with an important temple called the "House of Seth, Lord of Sepermeru". One of the epithets of this town was "gateway to the desert", which fits well with Set's role as a deity of the frontier regions of ancient Egypt. At Sepermeru, Set's temple enclosure included a small secondary shrine called "The House of Seth, Powerful-Is-His-Mighty-Arm", and Ramesses II himself built (or modified) a second land-owning temple for Nephthys, called "The House of Nephthys of Ramesses-Meriamun".

The two temples of Seth and Nephthys in Sepermeru were under separate administration, each with its own holdings and prophets. Moreover, another moderately sized temple of Seth is noted for the nearby town of Pi-Wayna. The close association of Seth temples with temples of Nephthys in key outskirt-towns of this milieu is also reflected in the likelihood that there existed another "House of Seth" and another "House of Nephthys" in the town of Su, at the entrance to the Fayyum.

Papyrus Bologna preserves a most irritable complaint lodged by one Pra'em-hab, Prophet of the "House of Seth" in the now-lost town of Punodjem ("The Sweet Place"). In the text of Papyrus Bologna, the harried Pra'em-hab laments undue taxation for his own temple (The House of Seth) and goes on to lament that he is also saddled with responsibility for: "The ship, and I am likewise also responsible for the House of Nephthys, along with the remaining heap of district temples".

Nothing is known about the particular theologies of the closely connected Set and Nephthys temples in these districts — for example, the religious tone of temples of Nephthys located in such proximity to those of Seth, especially given the seemingly contrary Osirian loyalties of Seth's consort-goddess. When, by the Twentieth Dynasty, the "demonization" of Seth was ostensibly inaugurated, Seth was either eradicated or increasingly pushed to the outskirts, Nephthys flourished as part of the usual Osirian pantheon throughout Egypt, even obtaining a Late Period status as tutelary goddess of her own Nome (UU Nome VII, "Hwt-Sekhem"/Diospolis Parva) and as the chief goddess of the Mansion of the Sistrum in that district.

Seth's cult persisted even into the latter days of ancient Egyptian religion, in outlying but important places like Kharga, Dakhlah, Deir el-Hagar, Mut, and Kellis. In these places, Seth was considered "Lord of the Oasis / Town" and Nephthys was likewise venerated as "Mistress of the Oasis" at Seth's side, in his temples (esp. the dedication of a Nephthys-cult statue). Meanwhile, Nephthys was also venerated as "Mistress" in the Osirian temples of these districts as part of the specifically Osirian college. It would appear that the ancient Egyptians in these locales had little problem with the paradoxical dualities inherent in venerating Seth and Nephthys, as juxtaposed against Osiris, Isis, and Nephthys.

In modern religion

Main articles: Kemetism, Temple of Set, and Sethian Liberation MovementIn popular culture

| This article may contain irrelevant references to popular culture. Please help Misplaced Pages to improve this article by removing the content or adding citations to reliable and independent sources. (July 2024) |

In the television series Doctor Who, Set (using the name Sutekh and portrayed by Gabriel Woolf) is depicted as an alien entity bent on destroying all life. He first appears in the 1975 serial Pyramids of Mars, where he schemes to escape an Egyptian pyramid he has been imprisoned in millennia ago by Horus. Sutekh returned after nearly 50 years in the 2024 Series 14 two-part finale "The Legend of Ruby Sunday" / "Empire of Death" as the God of Death in the Pantheon.

In the role-playing game Vampire: The Masquerade, the ancient Egyptian deity Set is depicted as an antediluvian vampire, believed to be one of the oldest undead beings. Revered as the founder of the enigmatic Followers of Set (now known as The Ministry in the game's fifth edition). Imprisoned in torpor, Set remains a focal point for his followers who strive to rouse him from his slumber. He commands powers entwined with manipulation, darkness, and serpentine subtlety, epitomized by his unique Discipline, Serpentis, dedicated to the mastery of serpents.

In the 1992 Nintendo Entertainment System video game Nightshade, the villain's public persona is that of "Sutekh", a criminal underboss who unifies the gangs of the fictitious Metro City. In line with the idea of Sutekh, of Egyptian mythology, the Sutekh in the video game reigns supreme over all of the violence in the city. Of particular note, in Egyptian mythology, Sutekh is also the god of foreigners. In the Nightshade video game, its villain is not of Egyptian descent, but instead a man by the name of Waldo P. Schmeer who is a historian obsessed with Egyptian lore. Set is also a minor villain in other video games, including Killing Time (1995, 1996) and PowerSlave (1996).

Sutekh is an antagonist in some films and other material in the Puppet Master universe. Sutekh is portrayed as the other worldly owner of the secret of life, which animates the eponymous puppets, and stalks anyone who steals it.

Ahead of the release of their 25th studio album, The Silver Cord, Australian band King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard released the album's first three songs. The third of these, titled "Set", describes Set killing Osiris and his subsequent conflict with Horus.

See also

Notes

- Also transliterated Seth, Setesh, Sutekh, Seteh, Setekh, or Suty. Sutekh appears, in fact, as a god of Hittites in the treaty declarations between the Hittite kings and Ramses II after the battle of Qadesh. Probably Seteh is the lection (reading) of a god honoured by the Hittites, the "Kheta", afterward assimilated to the local Afro-Asiatic Seth.

- Translation from Assmann 2008, p. 48. Goedicke's translation: "And then King Apophis, l.p.h., was appointing for himself Sutekh as Lord. He never worked for any other god which is in this entire country except Sutekh. Goldwasser's translation: "Then, king Apophis l.p.h. adopted for himself Seth as lord, and he refused to serve any god that was in the entire land except Seth."

References

- Doxey, Denise (2001). Anubis. In: In D. Redford, ed. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. I.Oxford: Oxford University Press. p.98.

- "Sobek from Ancient Egypt".

- Ritner, Robert K. (1984). "A uterine amulet in the Oriental Institute collection". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 43 (3): 209–221. doi:10.1086/373080. PMID 16468192. S2CID 42701708.

- Sayce, Archibald H. The Hittites: The story of a forgotten empire.

- Budge, E.A. Wallis. A History of Egypt from the End of the Neolithic Period to the Death of Cleopatra VII B.C. 30.

- ^ Herman Te Velde (2001). "Seth". Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 3.

- Strudwick, Helen (2006). The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-1-4351-4654-9.

- Doxey 2001,p.98.

- E.A. Wallis Budge, "Nephthys", in "The Gods of the Egyptians or Studies in Egyptian Mythology: Volume 2", London: Methuen & Co, 1904, p.254.

- Herman te Velde(1968). The Egyptian God Seth as a Trickster. In: Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 7, p.39.

- Levai, Jessica. "Nephthys and Seth: Anatomy of a Mythical Marriage", Paper presented at The 58th Annual Meeting of the American Research Center in Egypt, Wyndham Toledo Hotel, Toledo, Ohio, Apr 20, 2007.

- Rogers, John (2019). "The demon-deity Maga: geographical variation and chronological transformation in ancient Egyptian demonology". Current Research in Egyptology 2019: 183–203.

- ^ te Velde 1967, pp. 1–7.

- "Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae". aaew2.bbaw.de. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- "Coptic Dictionary Online". corpling.uis.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- te Velde 1967, pp. 13–15.

- Beinlich, Horst (2013). "Figure 7". The Book of the Faiyum (PDF). University of Heidelberg. pp. 27–77, esp.38–39.

- Lucarelli, Rita (2017). The Donkey in the Graeco-Egyptian Papyri. . doi:10.14277/6969-180-5/ant-11-8. ISBN 978-88-6969-180-5.

- te Velde 1967, pp. 7–12.

- Griffiths 1960, pp. 58–59

- Griffiths 1960, p. 82

- Assmann 2001, pp. 135, 139–140

- Griffiths 1960, pp. 12–16

- Assmann 2001, pp. 134–135

- Lichtheim 2006b, pp. 214–223

- Hart 2005, p. 73

- Pinch 2004, p. 83

- Lichtheim 2006b, pp. 218–219

- Griffiths 2001, pp. 188–190.

- te Velde 1967, pp. 55–56, 65

- Griffiths 1960, p. 42

- te Velde 1967, pp. 38–39, 43–44

- ^ Pinch 2004, pp. 82–83, 91

- te Velde 1967, pp. 42–43

- te Velde 1967, pp. 43–46, 58

- Kaper 2001, pp. 480–482.

- Griffiths 1960, p. 29

- Pinch 2004, p. 131

- te Velde 1967, pp. 56–57

- Assmann 2008, pp. 48, 151 n. 25, citing: Goedicke 1986, pp. 10–11 and Goldwasser 2006.

- Goedicke 1986, p. 31.

- Goldwasser 2006, p. 129.

- Gardiner 1932, p. 84.

- Assmann 2008, pp. 47–48.

- Nielsen, Nicky. "The Rise of the Ramessides: How a Military Family from the Nile Delta Founded One of Egypt's Most Celebrated Dynasties". American Research Center in Egypt. Retrieved 25 June 2022.