| Revision as of 20:43, 19 May 2014 edit188.29.120.183 (talk) →Presidential systems← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:32, 15 October 2024 edit undoGreenC bot (talk | contribs)Bots2,571,128 edits Move 1 url. Wayback Medic 2.5 per WP:URLREQ#articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com | ||

| (466 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Legal power to stop an official action, usually enactment of legislation}} | |||

| {{Other uses of}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September |

{{Other uses}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2024}} | |||

| ] signing a veto of a bill.]] | |||

| {{Refimprove|date=February 2008}} | |||

| A '''veto''' – Latin for "I forbid" – is the power (used by an officer of the state, for example) to unilaterally stop an official action, especially the enactment of legislation. A veto can be absolute, as for instance in the ], whose permanent members (], ], ], ], ]) can block any resolution. Or it can be limited, as in the legislative process of the United States, where a two-thirds vote in both the ] and ] may '''override''' a Presidential veto of legislation.<ref>] of the ]</ref> A veto only gives power to stop changes, not to adopt them (except for the rare "amendatory veto"). Thus a veto allows its holder to protect the status quo. | |||

| A '''veto''' is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a ] or ] vetoes a ] to stop it from becoming ]. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's ]. Veto powers are also found at other levels of government, such as in state, provincial or local government, and in international bodies. | |||

| The concept of a veto body originated with the ] ] and ]s. Either of the two consuls holding office in a given year could block a military or civil decision by the other; any tribune had the power to unilaterally block legislation passed by the ].<ref name="Spitzer">{{cite book|last=Spitzer|first=Robert J.|title=The presidential veto: touchstone of the American presidency|pages=1–2|publisher=SUNY Press|year=1988|isbn=978-0-88706-802-7}}</ref> | |||

| Some vetoes can be overcome, often by a ] vote: ], a two-thirds vote of the ] and ] can override a presidential veto.<ref name="us-veto">] of the ]</ref> Some vetoes, however, are absolute and cannot be overridden. For example, ], the five permanent members (], ], ], the ], and the ]) have an absolute veto over any Security Council ]. | |||

| ==Roman veto== | |||

| The institution of the veto, known to the Romans as the ''intercessio'', was adopted by the ] in the 6th century BC to enable the tribunes to protect the interests of the ] (common citizenry) from the encroachments of the ], who dominated the Senate. A tribune's veto did not prevent the senate from passing a bill, but meant that it was denied the force of law. The tribunes could also use the veto to prevent a bill from being brought before the plebeian assembly. The consuls also had the power of veto, as decision-making generally required the assent of both consuls. If one disagreed, either could invoke the ''intercessio'' to block the action of the other. The veto was an essential component of the Roman conception of power being wielded not only to manage state affairs but to moderate and restrict the power of the state's high officials and institutions.<ref name="Spitzer" /> | |||

| In many cases, the veto power can only be used to prevent changes to the status quo. But some veto powers also include the ability to make or propose changes. For example, the ] can use an amendatory veto to propose amendments to vetoed bills. | |||

| ==Westminster systems== | |||

| The executive power to veto legislation is one of the main tools that the executive has in the ], along with the ].{{sfn|Palanza|Sin|2020|p=367}} It is most commonly found in ] and ]s.<ref name="oecd-system"/> In ]s, the head of state often has either a weak veto power or none at all.{{sfn|Bulmer|2017|p=5}} But while some political systems do not contain a formal veto power, all political systems contain ]s, people or groups who can use ] to prevent policy change.{{sfn|Oppermann|Brummer|2017|p=3}} | |||

| ===Overview=== | |||

| In ]s and most ], the power to veto legislation by withholding the ] is a rarely used ] of the monarch. In practice, the Crown follows the convention of exercising its prerogative on the advice of its chief advisor, the prime minister. | |||

| The word "veto" comes from the ] for "I forbid". The concept of a veto originated with the ] offices of ] and ]. There were two consuls every year; either consul could block military or civil action by the other. The tribunes had the power to unilaterally block any action by a ] or the ] passed by the ].<ref name="Spitzer">{{cite book |last=Spitzer |first=Robert J. |title=The presidential veto: touchstone of the American presidency |pages=1–2 |publisher=SUNY Press |year=2000 |isbn=978-0-88706-802-7}}</ref> | |||

| ===Australia=== | |||

| Since the ] (1931), the United Kingdom Parliament may not repeal any Act of the Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia on the grounds that is repugnant to the laws and interests of the United Kingdom.<ref name="gov.au">{{cite web|url=http://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/item.asp?dID=25 |title=Documenting Democracy |publisher=Foundingdocs.gov.au |date=9 October 1942 |accessdate=2012-08-13}}</ref> Other countries in the ] (not to be confused with the Commonwealth of Australia), such as Canada and New Zealand, are likewise affected. However, according to the ] (sec. 59), the ] may veto a bill that has been given royal assent by the ] within one year of the legislation being assented to.<ref name="gov.au"/> This power has never been used. The Australian Governor-General himself or herself has, in theory, power to veto, or more technically, withhold assent to, a bill passed by both houses of the ], and contrary to the advice of the prime minister.<ref>{{Citation |last=Hamer |first=David |author-link=David Hamer |year=2002 |title=Can Responsible Government Survive in Australia? |chapter=Curiously ill-defined – the role of the head of state |publisher=Australian Government – Department of the Senate |publication-place=Canberra |origyear=1994, University of Canberra |url=http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Senate/Research_and_Education/hamer/chap05 |accessdate=19 December 2013}}</ref> This may be done without consulting the sovereign as per Section 58 of the constitution: | |||

| == History == | |||

| <blockquote>When a proposed law passed by both Houses of the Parliament is presented to the Governor-General for the Queen's assent, he shall declare, according to his discretion, but subject to this Constitution, that he assents in the Queen's name, or that he withholds assent, or that he reserves the law for the Queen's pleasure. The Governor-General may return to the house in which it originated any proposed law so presented to him, and may transmit therewith any amendments which he may recommend, and the Houses may deal with the recommendation.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/general/constitution/par5cha1.htm |title=Chapter I. The Parliament. Part V – Powers of the Parliament, Section 58 |work=] |publisher=]: ] |accessdate=13 October 2011 }}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| === Roman veto === | |||

| This ] is however, constitutionally arguable{{By whom|date=May 2013}}, and it is difficult to foresee an occasion when such a power would need to be exercised. It is possible that a Governor-general might so act if a bill passed by the Parliament was in violation of the Constitution.<ref></ref>{{dead link|date=May 2013}} One might argue, however, that a government would be hardly likely to present a bill which is so open to rejection. Many of the viceregal reserve powers are untested, because of the brief constitutional history of the Commonwealth of Australia, and the observance of the convention that the head of state acts upon the advice of his or her chief minister. The power may also be used in a situation where the parliament, usually a ], passes a bill without the blessing of the executive. The governor general on the advice of the executive could withhold consent from the bill thereby preventing its passage into law. | |||

| ] | |||

| The institution of the veto, known to the Romans as the ''intercessio'', was adopted by the ] in the 6th century BC to enable the tribunes to protect the ] interests of the ] (common citizenry) from the encroachments of the ], who dominated the Senate. A tribune's veto did not prevent the senate from passing a bill but meant that it was denied the force of law. The tribunes could also use the veto to prevent a bill from being brought before the plebeian assembly. The consuls also had the power of veto, as decision-making generally required the assent of both consuls. If they disagreed, either could invoke the ''intercessio'' to block the action of the other. The veto was an essential component of the Roman conception of power being wielded not only to manage state affairs but to moderate and restrict the power of the state's high officials and institutions.<ref name="Spitzer" /> | |||

| A notable use of the Roman veto occurred in the ], which was initially spearheaded by the tribune ] in 133 BC. When Gracchus' fellow tribune ] vetoed the reform, the Assembly voted to remove him on the theory that a tribune must represent the interests of the plebeians. Later, senators outraged by the reform murdered Gracchus and several supporters, setting off a period of internal political violence in Rome.<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| With regard to the six governors of the states which are federated under the Australian Commonwealth, a somewhat different situation exists. Until the ] 1986, each state was constitutionally dependent upon the British Crown directly. Since 1986, however, they are fully independent entities, although the Queen still appoints governors on the advice of the state head of government, the ]. So the Crown may not veto (nor the UK Parliament overturn) any act of a state governor or state legislature. Paradoxically, the states are more independent of the Crown than the federal government and legislature.<ref>{{cite web|author=Mediation Communications, Level 3, 414 Bourke Street, Melbourne Vic 3000, Phone 9602 2992, www.mediacomms.com.au |url=http://www.governor.vic.gov.au/role.htm |title=Government House |publisher=Governor.vic.gov.au |accessdate=2012-08-13}}{{dead link|date=September 2012}}</ref> State constitutions determine what role a governor plays. In general the governor exercises the powers the sovereign would have, including the power to withhold the Royal Assent. | |||

| | isbn = 9781316061923 | |||

| | title = Law and Power in the Making of the Roman Commonwealth | |||

| | author-first = Luigi | |||

| | author-last = Capogrossi Colognesi | |||

| | publisher = Cambridge University Press | |||

| | year = 2014 | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=kMkZBQAAQBAJ | |||

| | chapter = Tiberius Gracchus and the distribution of the ''ager publicus'' | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Liberum veto === | ||

| {{main|Liberum veto}} | |||

| According to the ], the ] may veto a bill by refusing ]. If the ] withholds the Queen's assent, the sovereign may within two years disallow the bill, thereby vetoing the law in question. However, this power has never been used. | |||

| In the constitution of the ] in the 17th and 18th centuries, all bills had to pass the ''Sejm'' or "Seimas" (parliament) by ] consent, and if any legislator invoked the '']'', this not only vetoed that bill but also all previous legislation passed during the session, and dissolved the legislative session itself. The concept originated in the idea of "Polish democracy" as any Pole of noble extraction was considered as good as any other, no matter how low or high his material condition might be. The more and more frequent use of this veto power paralyzed the power of the legislature and, combined with a string of weak figurehead kings, led ultimately to the ] in the late 18th century. | |||

| Provincial viceroys, called "]" (plural), however are able to reserve Royal Assent to provincial bills for the governor general; this clause was last invoked in 1961 by the Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan.<ref>Bastedo, Frank Lindsay, </ref> | |||

| === Emergence of modern vetoes === | |||

| ===India=== | |||

| ] granting royal assent to the ].]] | |||

| {{see also|President of India#Important presidential interventions}} | |||

| The modern executive veto derives from the European institution of ], in which the monarch's consent was required for bills to become law. This in turn had evolved from earlier royal systems in which laws were simply issued by the monarch, as was the case for example in England until the reign of ] in the 14th century.{{sfn|Watson|1987|p=403}} In England itself, the power of the monarch to deny royal assent was not used after 1708, but it was used extensively in the British colonies. The heavy use of this power was mentioned in the ] in 1776.{{sfn|Watson|1987|p=404}} | |||

| In India, the president has three veto powers i.e. absolute, suspension & pocket. The president can send the bill back to parliament for changes, which constitutes a limited veto that can be overridden by a simple majority. The president can also take no action indefinitely on a bill, sometimes referred to as a pocket veto.The president can refuse to assent, which constitutes an absolute veto.<ref name="intro india">{{cite book | title=Introduction to the Constitution of India |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=srDytmFE3KMC&pg=PA145 | publisher=Prentice-Hall of India Learning Pvt. Ltd. | author=Sharma, B.k. | year=2007 | location=New Delhi | page=145 | isbn=978-81-203-3246-1}}</ref><ref name="india times">{{cite news | url=http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2002-08-26/education/27323497_1_powers-impeachment-resolution | title=The President’s role |work=Times of India | date=26 August 2002 | accessdate=4 January 2012 | author=Gupta, V. P.}}</ref> | |||

| Following the ] in 1789, the royal veto was hotly debated, and hundreds of proposals were put forward for different versions of the royal veto, as either absolute, suspensive, or nonexistent.<ref>{{Cite journal | |||

| ===Spain=== | |||

| | journal = Journal of the Western Society for French History | |||

| In Spain, article 115 of the Constitution provides that the King shall give his assent to laws passed by the General Courts within 15 days after their final passing by them. The absence of the royal assent, although not constitutionally provided{{clarify|date=September 2012}}, would mean the bill did not become law. | |||

| | title = What was "Absolute" about the "Absolute veto"? Ideas of National Sovereignty and Royal Power in September 1789 | |||

| | author-first = Robert | |||

| | author-last = Blackman | |||

| | volume = 32 | |||

| | year = 2004 | |||

| | hdl = 2027/spo.0642292.0032.008 | |||

| | url = http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.0642292.0032.008 | |||

| }}</ref> With the adoption of the ], King ] lost his absolute veto and acquired the power to issue a suspensive veto that could be overridden by a majority vote in two successive sessions of the Legislative Assembly, which would take four to six years.<ref name="longman-2014">{{Cite book | |||

| | title = The Longman Companion to the French Revolution | |||

| | author-first = Colin | |||

| | author-last = Jones | |||

| | publisher = Routledge | |||

| | year = 2014 | |||

| | page = 67 | |||

| | isbn = 9781317870807 | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=xcXKAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA67 | |||

| }}</ref> With the abolition of the monarchy in 1792, the question of the French royal veto became moot.<ref name="longman-2014"/> | |||

| The presidential veto was conceived in by ] in the 18th and 19th centuries as a counter-majoritarian tool, limiting the power of a legislative majority.{{sfn|Bulmer|2017|pp=12-13}} Some republican thinkers such as ], however, argued for eliminating the veto power entirely as a relic of monarchy.{{sfn|Bulmer|2017|p=13}} To avoid giving the president too much power, most early presidential vetoes, such as the ], were qualified vetoes that the legislature could override.{{sfn|Bulmer|2017|p=13}} But this was not always the case: the Chilean constitution of 1833, for example, gave that country's president an absolute veto.{{sfn|Bulmer|2017|p=13}} | |||

| ===United Kingdom=== | |||

| In the United Kingdom, the royal veto ("withholding ]") was last exercised in 1708 by ] with the ]. | |||

| == Types == | |||

| The ] used to have the power of veto. However, reform first by a Liberal government and then by a Labour government has limited its powers. The ] reduced its powers: they can now only amend and delay legislation. They can delay legislation for up to one year. Under the 1911 Act, money bills (those concerning finance) cannot be delayed, and under the ], the Lords cannot delay any bills set out in the governing party's manifesto. | |||

| Most modern vetoes are intended as a check on the power of the government, or a ], most commonly the legislative branch. Thus, in governments with a ], vetoes may be classified by the branch of government that enacts them: an executive veto, ], or ]. | |||

| == United States ==<!-- This section is linked from ] --> | |||

| Other types of veto power, however, have safeguarded other interests. The denial of ] by governors in the British colonies, which continued well after the practice had ended in Britain itself, served as a check by one level of government against another.{{sfn|Watson|1987|p=403}} Vetoes may also be used to safeguard the interests of particular groups within a country. The veto power of the ancient Roman tribunes protected the interests of one social class (the plebeians) against another (the patricians).{{sfn|Watson|1987|p=402}} In the transition from ], a "white veto" to protect the interests of ] was proposed but not adopted.<ref>{{Cite news | |||

| ===According to the Constitution=== | |||

| | url = https://www.newsweek.com/apartheid-ash-heap-191424 | |||

| {{See also|List of United States presidential vetoes|Line-item veto in the United States|Pocket veto}} | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-17 | |||

| All legislation passed by both houses of Congress must be presented to the ]. This presentation is in the President's capacity as Head of State. | |||

| | title = Apartheid on the Ash Heap | |||

| | author = Joe Contreras | |||

| | work = Newsweek | |||

| | date = 1993-11-28 | |||

| }}</ref> More recently, ]es over industrial projects on Indigenous land have been proposed following the 2007 ], which requires the "free, prior and informed consent" of Indigenous communities to development or resource extraction projects on their land. However, many governments have been reluctant to allow such a veto.<ref>{{Cite journal | |||

| | title = Indigenous Veto Power in Bolivia | |||

| | author-first = Jessie | |||

| | author-last = Shaw | |||

| | pages = 231–238 | |||

| | year = 2017 | |||

| | doi = 10.1080/10402659.2017.1308737 | |||

| | journal = Peace Review | |||

| | volume = 29 | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| | s2cid = 149072601 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Vetoes may be classified by whether the vetoed body can override them, and if so, how. An absolute veto cannot be overridden at all. A qualified veto can be overridden by a ], such as two-thirds or three-fifths. A suspensory veto, also called a suspensive veto, can be overridden by a simple majority, and thus serves only to delay the law from coming into force.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| If the ] approves of the legislation, he signs it into law. According to ] of the Constitution,<ref>{{citation | url = http://www.senate.gov/reference/resources/pdf/RS22188.pdf | format = PDF | title = Regular Vetoes and Pocket Vetoes: An Overview | first = Kevin R. |last = Kosar | date = 18 July 2008}}</ref> when the President chooses, if he does not approve, he must return the ], unsigned, within ten days, excluding Sundays, to the house of the ] in which it originated, while the Congress is ]. The President is constitutionally required to state his objections to the legislation in writing, and the Congress is constitutionally required to consider them, and to reconsider the legislation. This action, in effect, is a veto. | |||

| | title = Black's Law Dictionary | |||

| | editor-first = Bryan | |||

| | editor-last = Garner | |||

| | page = 4841 | |||

| | edition = 8th | |||

| | year = 2004 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| === Types of executive vetoes === | |||

| If the Congress ] the veto by a ] in each house, it becomes law without the President's signature. Otherwise, the bill fails to become law unless it is presented to the President again and he chooses to sign it. Historically, the Congress ] the Presidential veto less than 10% of the time.<ref name="US Senate Glossary">{{cite web|title=US Senate Glossary|url=http://www.senate.gov/reference/glossary_term/override_of_a_veto.htm|work=US Senate Glossary|publisher=US Senate|accessdate=2 December 2013}}</ref> | |||

| ] signing cancellation letters related to his ] for the ].]] | |||

| A package veto, also called a "block veto" or "full veto", vetoes a ] as a whole. A partial veto, also called a ], allows the executive to object only to some specific part of the law while allowing the rest to stand. An executive with a partial veto has a stronger negotiating position than an executive with only a package veto power.<ref name="oecd-system"/> | |||

| A bill can also become law without the President's signature if, after it is presented to him, he simply fails to sign it within the ten days noted. If there are fewer than ten days left in the session before Congress ], and if Congress does so ] before the ten days have expired in which the President might sign the bill, then the bill fails to become law. This procedure, when used as a formal device, is called a ]. | |||

| {{anchor|Amendatory veto}}<!-- redirect target from ] --> | |||

| An amendatory veto or amendatory observation returns legislation to the legislature with proposed amendments, which the legislature may either adopt or override. The effect of legislative inaction may vary: in some systems, if the legislature does nothing, the vetoed bill fails, while in others, the vetoed bill becomes law. Because the amendatory veto gives the executive a stronger role in the legislative process, it is often seen as a marker of a particularly strong veto power. | |||

| Some veto powers are limited to budgetary matters (as with line-item vetoes in some US states, or the financial veto in New Zealand).{{sfn|NCSL|1998|p=6-29}} Other veto powers (such as in Finland) apply only to non-budgetary matters; some (such as in South Africa) apply only to constitutional matters. A veto power that is not limited in this way is known as a "policy veto".<ref name="oecd-system"/> | |||

| ===Modifications declared unconstitutional=== | |||

| In 1983, the Supreme Court had struck down the one-house ], on ] grounds and on grounds that the action by one house of Congress violated the Constitutional requirement of bicameralism. The case was '']'', concerning a foreign exchange student in ] who had been born in Kenya but whose parents were from India. Because he was not born in India, he was not an Indian citizen. Because his parents were not Kenyan citizens, he was not Kenyan. Thus, he had nowhere to go when his student visa expired because neither country would take him, so he overstayed his visa and was ordered to show cause why he should not be deported from the United States. | |||

| One type of budgetary veto, the reduction veto, which is found in several US states, gives the executive the authority to reduce budgetary appropriations that the legislature has made.{{sfn|NCSL|1998|p=6-29}} When an executive is given multiple different veto powers, the procedures for overriding them may differ. For example, in the US state of Illinois, if the legislature takes no action on a reduction veto, the reduction simply becomes law, while if the legislature takes no action on an amendatory veto, the bill dies.<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| The Immigration and Nationality Act was one of many acts of Congress passed since the 1930s, which contained a provision allowing either house of that legislature to nullify decisions of agencies in the executive branch simply by passing a resolution. In this case, Chadha's deportation was suspended and the ] passed a resolution overturning the suspension, so that the deportation proceedings would continue. This, the Court held, amounted to the House of Representatives passing legislation without the concurrence of the Senate, and without presenting the legislation to the President for consideration and approval (or veto). Thus, the Constitutional principle of bicameralism and the separation of powers doctrine were disregarded in this case, and this legislative veto of executive decisions was struck down. | |||

| | url = https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/glossary.asp#V | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-18 | |||

| | title = Legislative Glossary | |||

| | publisher = Illinois General Assembly | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| A ] is a veto that takes effect simply by the executive or head of state taking no action. In the United States, the pocket veto can only be exercised near the end of a legislative session; if the deadline for presidential action passes ''during'' the legislative session, the bill will simply become law.{{sfn|Watson|1987|p=407}} The legislature cannot override a pocket veto.{{sfn|Palanza|Sin|2020|p=367}} | |||

| In 1996, the ] passed, and President ] signed, the ]. This ] allowed the President to veto individual items of budgeted expenditures from appropriations bills instead of vetoing the entire bill and sending it back to the Congress. However, this ] was immediately challenged by members of Congress who disagreed with it. In 1998, the ] declared the line-item veto unconstitutional. The Court found the language of the Constitution required each bill presented to the President to be either approved or rejected as a whole. An action by which the President might pick and choose which parts of the bill to approve or not approve amounted to the President acting as a legislator instead of an executive and ]—and particularly as a single legislator acting in place of the entire Congress—thereby violating the ] doctrine. (See '']'', {{ussc|524|417|1998}}.) | |||

| Some veto powers are limited in their subject matter. A constitutional veto only allows the executive to veto bills that are ]; in contrast, a "policy veto" can be used wherever the executive disagrees with the bill on policy grounds.<ref name="oecd-system">{{Cite web | |||

| In 2006, Senator ] introduced the ] in the ]. Rather than provide for an actual legislative veto, however, the procedure created by the Act provides that, if the President should recommend rescission of a budgetary line item from a budget bill he previously signed into law—a power he already possesses pursuant to U.S. Const. Art. II—the Congress must vote on his request within ten days. Because the legislation that is the subject of the President's request (or "Special Message", in the language of the bill) was already enacted and signed into law, the vote by the Congress would be ordinary legislative action, not any kind of veto—whether line-item, legislative or any other sort. The House passed this measure, but the Senate never considered it, so the bill expired and never became law. | |||

| | url = https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/025c3909-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/025c3909-en | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-13 | |||

| | title = 4. System of government | |||

| | work = Constitutions in OECD Countries: A Comparative Study : Background Report in the Context of Chile's Constitutional Process}}</ref> Presidents with constitutional vetoes include those of Benin and South Africa. | |||

| === |

=== Legislative veto === | ||

| {{main|Legislative veto}} | |||

| The ] of the ] (1774–1781) did not have the ]. The President could not veto an act of Congress under the ] (1781–1789), but he possessed certain recess and reserve powers that were not necessarily available to the predecessor President of Continental Congress. It was only with the enactment of the ] (drafted 1787; ratified 1788; fully effective since 4 March 1789) that veto power was conferred upon the person titled "President of the United States". | |||

| A legislative veto is a veto power exercised by a legislative body. It may be a veto exercised by the legislature against an action of the executive branch, as in the case of the ], which is found in 28 US states.<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| The presidential veto power was first exercised on 5 April 1792<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.senate.gov/reference/reference_index_subjects/Vetoes_vrd.htm | title = Vetoes | work = Virtual Reference Desk | publisher = United States Senate}} – includes lists of vetoes from 1789 to the current day.</ref> when President ] vetoed a bill outlining a new apportionment formula submitted by then Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. Apportionment described how Congress divides seats in the House of Representatives among the states based on the US census figures. President Washington thought the bill gave an unfair advantage to the northern states. | |||

| | url = https://www.ncsl.org/research/about-state-legislatures/separation-of-powers-legislative-oversight.aspx | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-22 | |||

| | title = Separation of Powers: Legislative Oversight | |||

| | publisher = National Conference of State Legislatures | |||

| }}</ref> It may also be a veto power exercised by one chamber of a ] against another, such as was formerly held by members of the ] appointed by the ].<ref>{{Cite journal | |||

| | title = A tale of three constitutions: Ethnicity and politics in Fiji | |||

| | author1-first = Yash | |||

| | author1-last = Ghai | |||

| | author2-first = Jill | |||

| | author2-last = Cottrell | |||

| | journal = International Journal of Constitutional Law | |||

| | volume = 5 | |||

| | issue = 4 | |||

| | year = 2007 | |||

| | pages = 639–669 | |||

| | doi = 10.1093/icon/mom030| doi-access = free | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| === Veto over candidates === | |||

| The Congress first overrode a presidential veto (passed a bill into law notwithstanding the President's objections) on 3 March 1845.<ref name=veto_history>{{cite web| url=http://www.senate.gov/reference/resources/pdf/presvetoes17891988.pdf | title=Presidential Vetoes, 1789 to 1988 | format=PDF | date=February 1992 | publisher=The U.S. Government Printing Office | accessdate=2 March 2009}}</ref> | |||

| In certain political systems, a particular body is able to exercise a veto over candidates for an elected office. This type of veto may also be referred to by the broader term "]". | |||

| Historically, certain European Catholic monarchs were able to veto candidates for the ], a power known as the ''jus exclusivae''. This power was used for the last time in 1903 by ].<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| ===U.S. states, veto powers, and override authority=== | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=eBZFL5fzwawC&pg=PA35 | |||

| All U.S. states also have a provision by which legislative decisions can be vetoed by the governor. In addition to the ability to veto an entire bill as a "package," many states allow the governor to exercise specialty veto authority to strike or revise portions of a bill without striking the whole thing. | |||

| | page = 35 | |||

| | isbn = 9781402729546 | |||

| | title = Selecting the Pope: Uncovering the Mysteries of Papal Elections | |||

| | author-first = Greg | |||

| | author-last = Tobin | |||

| | publisher = Sterling Publishing Company | |||

| | year = 2009 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| In Iran, the ] has the power to approve or disapprove candidates, in addition to its veto power over legislation. | |||

| '''Amendatory veto:'''<br /> | |||

| Allows a governor to amend bills that have been passed by the legislature. Revisions are subject to confirmation or rejection by the legislature.<ref name="Vock">{{cite web|last=Vock|first=Daniel|title=Govs enjoy quirky veto power|url=http://www.pewstates.org/projects/stateline/headlines/govs-enjoy-quirky-veto-power-85899386875|publisher=pewstates.org|accessdate=24 April 2007}}</ref> | |||

| In China, following a pro-democracy landslide in the ], in 2021 the ] approved ] that gave the ], appointed by the ], the power to veto candidates for the ].<ref>{{Cite news | |||

| '''Line item veto:'''<br /> | |||

| | url = https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3141117/hong-kong-electoral-changes-powerful-vetting-committee-will | |||

| Allows a governor to remove specific sections of a bill (usually only spending bills) that has been passed by the legislature. Deletions can be overridden by the legislature.<ref name="Vock"/> | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-13 | |||

| | title = Hong Kong electoral changes: powerful vetting committee that will review hopefuls in coming polls holds first meeting | |||

| | newspaper = South China Morning Post | |||

| | author-first = Christy | |||

| | author-last = Leung | |||

| | date = 2021-07-14 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| == Balance of powers == | |||

| '''Pocket veto:'''<br /> | |||

| {{main|Balance of powers}} | |||

| Any bill presented to a governor after a session has ended must be signed to become law. A governor can refuse to sign such a bill and it will expire. Such vetoes cannot be overridden.<ref name="Vock"/> | |||

| In presidential and semi-presidential systems, the veto is a legislative power of the presidency, because it involves the president in the process of making law. In contrast to proactive powers such as the ], the veto is a reactive power, because the president cannot veto a bill until the legislature has passed it.{{sfn|Croissant|2003|p=72}} | |||

| '''Reduction veto:'''<br /> | |||

| Allows a governor to reduce the amounts budgeted for spending items. Reductions can be overridden by the legislature.<ref name="Vock"/> | |||

| Executive veto powers are often ranked as comparatively "strong" or "weak". A veto power may be considered stronger or weaker depending on its scope, the time limits for exercising it and requirements for the vetoed body to override it. In general, the greater the majority required for an override, the stronger the veto.<ref name="oecd-system"/> | |||

| '''Package veto:'''<br /> | |||

| Allows a governor to veto the entire bill. Package vetoes can be overridden by the legislature.<ref name="Vock"/> | |||

| <br /> | |||

| Partial vetoes are less vulnerable to override than package vetoes,<ref name="metcalf-2000">{{Cite journal | |||

| | author-first = Lee Kendall | |||

| <ref>{{cite book|title=The Book of the States 2010|year=2010|publisher=The Council of State Governments|pages=140–142|url=http://www.nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/BOSTable3.16.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| | author-last = Metcalf | |||

| | year = 2000 | |||

| | title = Measuring Presidential Power | |||

| | journal = Comparative Political Studies | |||

| | volume = 33 | |||

| | issue = 5 | |||

| | page = 670 | |||

| | doi = 10.1177/0010414000033005004 | |||

| | s2cid = 154874901 | |||

| }}</ref> and political scientists who have studied the matter have generally considered partial vetoes to give the executive greater power than package vetoes.{{sfn|Palanza|Sin|2020|p=375}} However, empirical studies of the line-item veto in US state government have not found any consistent effect on the executive's ability to advance its agenda.{{sfn|Palanza|Sin|2020|p=374}} Amendatory vetoes give greater power to the executive than deletional vetoes, because they give the executive the power to move policy closer to its own preferred state than would otherwise be possible.{{sfn|Palanza|Sin|2020|p=382}} But even a suspensory package veto that can be overridden by a simple majority can be effective in stopping or modifying legislation. For example, in Estonia in 1993, president ] was able to successfully obtain amendments to the proposed Law on Aliens after issuing a suspensory veto of the bill and proposing amendments based on expert opinions on European law.<ref name="metcalf-2000"/> <!-- An amendatory veto... --> | |||

| == Worldwide == | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| ] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! State !! Veto Powers !! Veto Override Standard | |||

| |- | |||

| | Alabama || Amendatory, Pocket, Line Item, Package || Majority elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Alaska || Reduction, Line Item, Package || Regular bills: 2/3 elected; Budget bills: 3/4 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Arizona || Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected (Misc items have 3/4 elected standard) | |||

| |- | |||

| | Arkansas || Line Item, Package || Majority elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | California || Reduction, Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Colorado || Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Connecticut || Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Delaware || Pocket, Line Item, Package || 3/5 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Florida || Line Item, Package || 2/3 present | |||

| |- | |||

| | Georgia || Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Hawaii || Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Idaho || Line Item, Package || 2/3 present | |||

| |- | |||

| | Illinois || Amendatory, Reduction, Line Item (spending only), Package || 3/5 elected for package, majority elected for reduction/line item, majority elected required to affirm amendments<ref>] (1970) Article IV, Section 9</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | Indiana || Package || Majority elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Iowa || Pocket, Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Kansas || Line Item, Package || 2/3 membership | |||

| |- | |||

| | Kentucky || Line Item, Package || Majority elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Louisiana || Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Maine || Reduction, Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Maryland || Line Item, Package || 3/5ths elected<ref>], Article II, Sec. 17(a)</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | Massachusetts || Amendatory, Pocket, Reduction, Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected; normal majority required to accept amendments<ref>], Amendments, .</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | Michigan || Pocket, Reduction, Line Item, Package || 2/3rds elected<ref>] (1963), Article IV § 33</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | Minnesota || Pocket, Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected – min. 90 House, 45 Senate | |||

| |- | |||

| | Mississippi || Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Missouri || Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Montana || Amendatory, Line Item, Package || 2/3 present | |||

| |- | |||

| | Nebraska || Reduction, Line Item, Package || 3/5 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Nevada || Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | New Hampshire || Package || 2/3 present | |||

| |- | |||

| | New Jersey || Amendatory, Pocket, Reduction, Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | New Mexico || Line Item, Package || 2/3 present | |||

| |- | |||

| | New York || Pocket, Line Item, Package || 2/3 votes in each house | |||

| |- | |||

| | North Carolina || Package || 3/5 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | North Dakota || Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Ohio || Line Item, Package || 3/5 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Oklahoma || Pocket, Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Oregon || Line Item, Package || 2/3 present | |||

| |- | |||

| | Pennsylvania || Reduction, Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Rhode Island || Line Item, Package || 3/5 present | |||

| |- | |||

| | South Carolina || Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | South Dakota || Amendatory, Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Tennessee || Reduction, Line Item, Package || Constitutional majority (Majority elected)<ref>], art. III, sec. 18</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | Texas || Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Utah || Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Vermont || Pocket, Package || 2/3 present | |||

| |- | |||

| | Virginia || Amendatory, Line Item, Package || 2/3 present (must include majority of elected members) | |||

| |- | |||

| | Washington || Line Item, Package || 2/3 present | |||

| |- | |||

| | West Virginia || Reduction, Line Item, Package || Majority elected | |||

| |- | |||

| | Wisconsin || Amendatory, Reduction, Line Item, Package || 2/3 present | |||

| |- | |||

| | Wyoming || Line Item, Package || 2/3 elected | |||

| |} | |||

| Globally, the executive veto over legislation is characteristic of ] and ]s, with stronger veto powers generally being associated with stronger presidential powers overall.<ref name="oecd-system"/> In ]s, the veto power of the head of state is typically weak or nonexistent.{{sfn|Bulmer|2017|p=5}} In particular, in ]s and most ], the power to veto legislation by withholding ] is a rarely used ] of the monarch. In practice, the Crown follows the convention of exercising its prerogative on the advice of parliament. | |||

| == European parliamentary republics == | |||

| === |

=== International bodies === | ||

| * {{flag|United Nations}}: The five permanent members of the ] have an absolute veto over Security Council resolutions, except for procedural matters.<ref name="un-27">{{Cite web | |||

| Many parliamentary republics in Europe allow a form of limited presidential veto on legislation. This include Italy, Portugal, the Republic of Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, and Hungary. | |||

| | title = Charter of the United Nations: Chapter V – The Security Council: Article 27 | |||

| | url = https://legal.un.org/repertory/art27.shtml | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-15 | |||

| | work = Repertory of Practice of United Nations Organs | |||

| | publisher = United Nations | |||

| }}</ref> Every permanent member has used this power at some point.<ref name="un-voting">{{Cite web | |||

| | url = https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/voting-system | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-15 | |||

| | title = Voting System | |||

| | publisher = United Nations Security Council | |||

| | quote = All five permanent members have exercised the right of veto at one time or another. If a permanent member does not fully agree with a proposed resolution but does not wish to cast a veto, it may choose to abstain, thus allowing the resolution to be adopted if it obtains the required number of nine favourable votes. | |||

| }}</ref> A permanent member that wants to disagree with a resolution, but not to veto it, can abstain.<ref name="un-voting"/> The first country to use the latter power was the ] in 1946, after its amendments to a resolution regarding the withdrawal of British troops from Lebanon and Syria were rejected.<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | url = https://undocs.org/en/S/PV.23 | |||

| | title = Twenty-Third Meeting | |||

| | date = 1946-02-16 | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-15 | |||

| | publisher = United Nations | |||

| }}</ref>{{further|United Nations Security Council veto power}} | |||

| * {{flag|European Union}}: The members of the ] have veto power in certain areas, such as foreign policy and the accession of a new member state, due to the requirement of unanimity in these areas. For example, Bulgaria has used this power to block ],<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | url = https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/short_news/bulgaria-sets-3-conditions-for-lifting-north-macedonia-veto/ | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-15 | |||

| | title = Bulgaria sets 3 conditions for lifting North Macedonia veto | |||

| | work = EURACTIV.com | |||

| | author = Krassen Nikolov | |||

| | date = 2022-06-09 | |||

| }}</ref> and in the 1980s, the United Kingdom (then a member of the EU's precursor, the ]) secured the ] by threatening to use its veto power to stall legislation.<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| | title = Veto Power: Institutional Design in the European Union | |||

| | author-first = Jonathan B. | |||

| | author-last = Slapin | |||

| | year = 2011 | |||

| | publisher = University of Michigan Press | |||

| | doi = 10.2307/j.ctt1qv5nfq | |||

| | url = https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1qv5nfq | |||

| | page = 123 | |||

| | isbn = 9780472117932 | |||

| | chapter = Exit Threats, Veto Rights, and Integration | |||

| | jstor = j.ctt1qv5nfq | |||

| }}</ref> In addition, when the ] and Council delegate legislative authority to the ], they can provide for a ] over regulations that the Commission issues under that delegated authority.<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | url = https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:12008E290:en:HTML | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-15 | |||

| | work = EUR-Lex | |||

| | title = Article 290 | |||

| }}</ref><ref name="schuetze-2011">{{Cite journal | |||

| | title = 'Delegated' Legislation in the (new) European Union: A Constitutional Analysis | |||

| | author-first = Robert | |||

| | author-last = Schütze | |||

| |journal = The Modern Law Review | |||

| | date = September 2011 | |||

| | volume = 74 | |||

| | issue = 5 | |||

| | pages = 661–693 | |||

| | doi = 10.1111/j.1468-2230.2011.00866.x | |||

| | jstor = 41302774 | |||

| | s2cid = 219376667 | |||

| | url = https://www.jstor.org/stable/41302774}}</ref> This power was first introduced in 2006 as "regulatory procedure with scrutiny", and since 2009 as "delegated acts" under the ].<ref name="dearth">{{Cite web | |||

| | url = https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2016/10/25/a-dearth-of-legislative-vetoes/ | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-15 | |||

| | title = A dearth of legislative vetoes: Why the Council and Parliament have been reluctant to veto Commission legislation | |||

| | author1-first = Michael K. | |||

| | author1-last = Kaeding | |||

| | author2-first = Kevin M. | |||

| | author2-last = Stack | |||

| | date = 2016-10-25 | |||

| }}</ref> This legislative veto power has been used sparingly: from 2006 to 2016, the Parliament issued 14 vetoes and the Council issued 15.<ref name="dearth"/>{{further|Voting in the Council of the European Union|European Union legislative procedure}} | |||

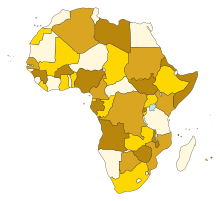

| === Africa === | |||

| The ] has no veto power but signs bills into law. | |||

| ] | |||

| *{{flag|Benin}}: The ] can return legislation to the ] for reconsideration within 15 days (or 5 days if the legislation is declared urgent).{{sfn|Bulmer|2017|p=19}} The National Assembly can override the veto by passing the legislation once again by an ].{{sfn|Bulmer|2017|p=19}}<ref name="benin-57">{{Cite constitution | polity = Benin | date = 1990 | article = 57}}</ref> If the president then vetoes the legislation a second time, the National Assembly can ask the ] to rule on its constitutionality. If the Court rules that the legislation is constitutional, it becomes law.{{sfn|Bulmer|2017|p=33}}<ref name="benin-57"/> If the president neither approves nor returns legislation within the prescribed 15- or 5-day period, this operates as a veto, and the National Assembly can petition the Court to declare the law constitutional and effective.<ref name="benin-57"/> This occurred for example in 2008, when ] did not take action on a bill that would set an end date to the "exceptional measures" by which he had kept the National Assembly in session. After pocket-vetoing the bill in this way, the president petitioned the Court for constitutional review.<ref name="dcc08-171"/> The Court ruled that once the deadline for presidential action had passed, only the National Assembly could petition for review, which it did (and prevailed).<ref name="dcc08-171">{{Cite web | |||

| | url = https://courconstitutionnellebenin.bj/old/upload/decision/DCC08-171.pdf | |||

| | language = French | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-14 | |||

| | title = DCC08-171 | |||

| | date = 2008-12-04 | |||

| | author = Constitutional Court of Benin | |||

| }}</ref>{{further|Politics of Benin}} | |||

| *{{flag|Cameroon}}: The ] has the power to send bills back to the ] for a second reading.<ref name="cameroon-19">{{cite constitution | polity = Cameroon | date =2008 | article = 19}}</ref> This power must be exercised within 15 days.<ref>{{Cite constitution| polity = Cameroon | date = 2008 | article = 31}}</ref> On second reading the bill must be passed by an ] to become law.<ref name="cameroon-19"/>{{further|Government of Cameroon}} | |||

| *{{flag|Liberia}}: The ] has package, line item and pocket veto powers under Article 35 of the 1986 ]. The President has twenty days to sign a bill into law, but may veto either the entire bill or parts of it, after which the ] must re-pass it with a two-thirds majority of both houses. If the President does not sign a bill within twenty days and the Legislature adjourns, the bill fails.{{sfn|Bulmer|2017|p=8}}{{further|Politics of Liberia}} | |||

| *{{flag|South Africa}}: The ] has a weak constitutional veto.<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | url = https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2019-11-21-no-sir-the-president-does-not-have-the-power-to-veto-the-copyright-bill/ | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-13 | |||

| | title = No Sir, the president does not have the power to veto the Copyright Bill | |||

| | author = ] | |||

| | date = 2019-11-20 | |||

| }}</ref> The president can return a bill to the ] if the president has reservations about the bill's constitutionality.<ref name="south-africa-79">{{Cite constitution | polity = South Africa | date = 2012 | article = 79}}</ref> If the National Assembly passes the bill a second time, the president must either sign it or refer it to the ] for a final decision on whether the bill is constitutional.<ref name="south-africa-79"/> If there are no constitutional concerns, the president's assent to legislation is mandatory.{{further|Politics of South Africa}} | |||

| *{{flag|Uganda}}: The ] has package veto and item veto powers.<ref name="uganda-91">{{Cite constitution | polity = Uganda | date = 2017 | article = 91}}</ref> This power must be exercised within 30 days of receiving the legislation.<ref name="uganda-91"/> The first time the president returns a bill to the ], the Parliament can pass it again by a simple majority vote. If the president returns it a second time, the Parliament can override the veto with a two-thirds vote.<ref name="uganda-91"/> This occurred for example in the passage of the Income Tax Amendment Act 2016, which exempted legislators' allowances from taxation.<ref>{{Cite news | |||

| | url = https://www.independent.co.ug/kadaga-income-tax-amendment-bill-now-law/ | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-13 | |||

| | title = KADAGA: Income Tax Amendment Bill is now law | |||

| | newspaper = The Independent|location=Uganda | |||

| | date = 2016-12-22 | |||

| }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book | |||

| | chapter = Interaction Between MPs and Civil Society Is Needed | |||

| | author-first = Agnes | |||

| | author-last = Titriku | |||

| | editor = R. Stapenhurst | |||

| | display-editors = etal | |||

| | title = Anti-Corruption Evidence, Studies in Public Choice 34 | |||

| | doi = 10.1007/978-3-030-14140-0_5 | |||

| | s2cid = 198750839 | |||

| }}</ref>{{further|Politics of Uganda}} | |||

| *{{flag|Zambia}}: Under the 1996 constitution, the ] had an absolute pocket veto: if he neither assented to legislation nor returned it to parliament for a potential override, it was permanently dead.{{sfn|Bulmer|2017|p=31}} This unusual power was eliminated in a general reorganization of the Constitution's legislative provisions in 2016.<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | url = https://www.parliament.gov.zm/sites/default/files/documents/bills/National%20Assembly%20Bill%2017-2015.PDF | |||

| | year = 2015 | |||

| | title = The Constitution of Zambia (Amendment) (N.A.B. 17, 2015) | |||

| | publisher = Parliament of Zambia | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160109092321/https://www.parliament.gov.zm/sites/default/files/documents/bills/National%20Assembly%20Bill%2017-2015.PDF | |||

| | archive-date = 9 January 2016 | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref><ref>{{Cite constitution | polity = Zambia | date = 2016 | article = 66}}</ref>{{further|Politics of Zambia}} | |||

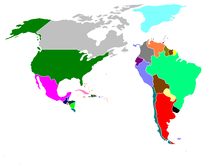

| === Americas === | |||

| The ] may refuse to sign a bill, which is then put to universal adult ]. This right was not exercised until 2004, by President ], who has since refused to sign two other bills. The first bill was withdrawn, but the latter two resulted in referenda. | |||

| ] | |||

| * {{flag|Brazil}}: The ] is entitled to veto, entirely or partially, any bill which passes both houses of the ], exceptions made to ] and congressional decrees. The partial veto can involve the entirety of paragraphs, articles or items, not being allowed to veto isolated words or sentences. National Congress has the right to override the presidential veto if the majority of members from each of both houses agree to, that is, 257 ] and 41 ]. If these numbers are not met, the presidential veto stands.<ref> . National Congress of Brazil. Accessed 15 October 2022.</ref>{{further|Government of Brazil}} | |||

| * {{flag|Canada}}: The ] (in practice the ]) might instruct the ] to withhold the king's assent, allowing the sovereign two years to disallow the bill, thereby vetoing it.<ref>{{Cite constitution | polity = Canada | date = 1867 | article = 53}}</ref> Last used in 1873, the power was effectively nullified diplomatically and politically by the ], and legally by the ]. At the province level, ] can reserve royal assent to provincial bills for consideration by the ]. This clause was last invoked in 1961 by the lieutenant governor of Saskatchewan.<ref>Jackson, Michael. . ''Encyclopedia of Saskatachewan''. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130524112727/http://esask.uregina.ca/entry/bastedo_frank_lindsay_1886-1973.html |date=24 May 2013 }}. Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina.</ref> In addition, the Governor General in Council (federal cabinet) may disallow an enactment of a provincial legislature within one year of its passage. {{further|Disallowance and reservation in Canada}} | |||

| *{{flag|Dominican Republic}}: The ] has only a package veto ({{lang|es|observación a la ley}}), which must be exercised within 10 days after the legislation is passed.<ref name="dr-102">{{cite constitution | article = 102 | polity = the Dominican Republic | date = 2015}}</ref> The veto must include a rationale.<ref name="dr-102"/> If both chambers of the ] vote to override the veto, the bill becomes law.<ref name="dr-102"/>{{further|Government of the Dominican Republic}} | |||

| *{{flag|Ecuador}}: The ] has powers of package veto and amendatory veto ({{lang|es|veto parcial}}).{{sfn|Tsebelis|Alemán|2005|p=406}} The president must issue a veto within 10 days after the bill is passed. The ] can override an amendatory veto by a two-thirds majority of all members, but if it does not do so within 30 days of the veto, the legislation becomes law with the president's amendments.{{sfn|Tsebelis|Alemán|2005|p=406}}<ref>{{Cite journal | |||

| | author1-last = Basabe-Serrano | |||

| | author1-first = Santiago | |||

| | author2-last = Huertas-Hernández | |||

| | author2-first = Sergio | |||

| | year = 2020 | |||

| | title = Legislative override and particularistic bills in unstable democracies: Ecuador in comparative perspective | |||

| | journal = The Journal of Legislative Studies | |||

| | volume = 27 | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| | page = 15 | |||

| | ref = {{harvid|Basabe-Serrano|2020}} | |||

| | doi = 10.1080/13572334.2020.1810902 | |||

| | s2cid = 224949744 | |||

| }}</ref> The National Assembly overrides approximately 20% of amendatory vetoes.{{sfn|Basabe-Serrano|2020|pp=6–7}} The legislature must wait for a year before overriding a package veto.{{sfn|Tsebelis|Alemán|2005|p=406}}{{further|Government of Ecuador}} | |||

| *{{flag|El Salvador}}: The ] has both package veto and amendatory veto powers, which must be exercised within eight days of the legislation being passed by the ].{{sfn|Tsebelis|Alemán|2005|p=405}} If the Legislative Assembly does not vote on an amendatory veto, the legislation fails. The Legislative Assembly can either accept or override an amendatory veto by a simple majority. Overriding a block veto requires a two-thirds supermajority.{{sfn|Tsebelis|Alemán|2005|p=405}}{{further|Government of El Salvador}} | |||

| *{{flag|Mexico}}: The ] has both package veto and amendatory veto powers, which must be exercised within ten days of the legislation being passed by the ].{{sfn|Tsebelis|Alemán|2005|p=405}} Congress may override either type of veto by a two-thirds majority of voting members in each chamber.{{sfn|Tsebelis|Alemán|2005|p=405}} However, in the case of an amendatory veto, Congress must first consider whether to accept the proposed amendments, which it may do by a simple majority of both chambers.{{sfn|Tsebelis|Alemán|2005|pp=405, 420}}{{further|Government of Mexico}} | |||

| * {{flag|United States}}: At the federal level, the ] may veto bills passed by Congress, and Congress may override the veto by a two-thirds vote of each chamber.<ref>{{Cite constitution | polity = the United States | date = 1789 | article = I | section = 7 }}</ref> A ] was briefly enacted in the 1990s, but was declared an unconstitutional violation of the ] by the Supreme Court. At the state level, all 50 state governors have a full veto, similar to the presidential veto.<ref name="ncsl-executive">{{Cite web | |||

| | url = https://www.ncsl.org/research/about-state-legislatures/separation-of-powers-executive-veto-powers.aspx | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-11 | |||

| | title = Separation of Powers – Executive Veto Powers | |||

| | author = National Conference of State Legislatures | |||

| | quote = Every state constitution empowers the governor to veto an entire bill passed by the legislature. | |||

| }}</ref> Many state governors also have additional kinds of vetoes, such as amendatory, line-item, and reduction vetoes.<ref name="ncsl-executive"/> Gubernatorial veto powers vary in strength. The president and some state governors have a "]", in that they can delay signing a bill until after the legislature has adjourned, which effectively kills the bill without a formal veto and without the possibility of an override.{{sfn|Watson|1987|p=407}}<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| | title = Inside the Legislative Process | |||

| | url = https://www.ncsl.org/research/about-state-legislatures/inside-the-legislative-process.aspx#GenlProcedures | |||

| | chapter = The Veto Process | |||

| | chapter-url = https://www.ncsl.org/documents/legismgt/ilp/98tab6pt3.pdf | |||

| | publisher = National Conference of State Legislatures | |||

| | year = 1998 | |||

| | pages = 6–31 | |||

| | ref = {{harvid|NCSL|1998}} | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100115021825/https://www.ncsl.org/documents/legismgt/ilp/98tab6pt3.pdf | |||

| | archive-date = 15 January 2010 | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref>{{further|Veto power in the United States|Line-item veto in the United States|Legislative veto in the United States}} | |||

| === Asia === | |||

| The ] has two options to veto a bill: submit it to the ] if he suspects that it violates the constitution or send it back to the ] and ask for a second debate and vote on the bill. If the Court rules that the bill is constitutional or it is passed by the Parliament again, respectively, the President must sign it. | |||

| ] | |||

| * {{flag|China}}: Under the ], the ] can nullify regulations enacted by the ]. The State Council and ] do not have a veto power.<ref name="china-qa">{{Cite web | |||

| | url = http://www.china.org.cn/english/features/Q&A/161688.htm | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-11 | |||

| | title = China Questions and Answers -- china.org.cn | |||

| | author = China Internet Information Center | |||

| | quote = Administrative regulations shall not contravene laws adopted by the NPC, local regulations shall not contravene laws and administrative regulations, and the NPC has the power to annul administrative regulations and local regulations that contravene the laws it has made. | |||

| }}</ref>{{further|Government of China}} | |||

| *{{flag|Georgia}}: The ] can return a bill to the ] with proposed amendments within two weeks of receiving the bill.<ref name="georgia-46">{{cite constitution | article= 46 | polity= Georgia (country) | date= 2018}}</ref> Parliament must first vote on the proposed amendments, which can be adopted by the same majority as for the original legislation (for ordinary legislation, a simple majority vote).<ref name="georgia-46"/> If Parliament does not adopt the amendments, it can override the veto by passing the original bill by an ].<ref name="georgia-46"/> Before the constitutional reforms of the 2010s, the president had both a package veto and an amendatory veto, which could be overridden only with a 3/5 majority.{{sfn|Tsebelis|Rizova|2007|p=1179}} {{further|Politics of Georgia (country)}} | |||

| * {{flag|India}}: The ] has three veto powers: absolute, suspension and pocket. The president can send the bill back to parliament for changes, which constitutes a limited veto that can be overridden by a simple majority. But the bill reconsidered by the parliament becomes a law with or without the president's assent after 14 days. The president can also take no action indefinitely on a bill, sometimes referred to as a pocket veto. The president can refuse to assent, which constitutes an absolute veto. But the absolute veto can be exercised by the President only once in respect of a bill. If the President refuses to provide his assent to a bill and sends it back to Parliament, suggesting his recommendations or amendments to the bill and the Parliament passes the bill again with or without such amendments, the president is obligated to assent to the bill.<ref>Article 111 of the ]</ref><ref name="intro india">{{cite book | title=Introduction to the Constitution of India |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=srDytmFE3KMC&pg=PA145 | publisher=Prentice-Hall of India Learning Pvt. Ltd. | author=Sharma, B.k. | year=2007 | location=New Delhi | page=145 | isbn=978-81-203-3246-1}}</ref><ref name="india times">{{cite news | url=https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/education/The-Presidents-role/articleshow/20154333.cms | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120616231317/http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2002-08-26/education/27323497_1_powers-impeachment-resolution | url-status=live | archive-date=16 June 2012 | title=The President's role | date=26 August 2002 | access-date=4 January 2012 | work=] | author=Gupta, V. P.}}</ref>{{further|President of India#Important presidential interventions in the past}} | |||

| *{{flag|Indonesia}}: Express presidential veto powers were removed from the Constitution in the 2002 democratization reforms.<ref>{{Cite journal | |||

| | author1-first = Simon | |||

| | author1-last = Butt | |||

| | author2-first = Tim | |||

| | author2-last = Lindsey | |||

| | title = Economic Reform when the Constitution Matters: Indonesia's Constitutional Court and Article 33 | |||

| | year = 2008 | |||

| | journal = Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies | |||

| | volume = 44 | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| | pages = 239–262 | |||

| | doi = 10.1080/00074910802169004 | |||

| | s2cid = 154149905 | |||

| }}</ref> The ] can however enact a "regulation in lieu of law" (''Peraturan Pemerintah Pengganti Undang-Undang'' or ''perppu''), which temporarily blocks a law from taking effect.<ref name="setiawan-2022"/> The ] (DPR) can revoke such a regulation in its next session.<ref name="indonesia-22">{{cite constitution | article= 22 | polity= Indonesia | date= 2022}}</ref> In addition, the ] requires that legislation be jointly approved by the president and the DPR. The president thus can effectively block a bill by withholding approval.<ref name="setiawan-2022">{{Cite book | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=6h9iEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT42 | |||

| | isbn = 9780429860935 | |||

| | title = Politics in Contemporary Indonesia: Institutional Change, Policy Challenges and Democratic Decline | |||

| | author1-first = Ken M.P | |||

| | author1-last = Setiawan | |||

| | author2-first = Dirk | |||

| | author2-last = Tomsa | |||

| | publisher = Routledge | |||

| | year = 2022 | |||

| }}</ref> Whether these presidential powers constitute a "veto" has been disputed, including by former Constitutional Court justice ].<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | url = https://www.merdeka.com/politik/adakah-hak-veto-presiden-dalam-sistem-ketatanegaraan.html | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-13 | |||

| | title = Adakah hak veto presiden dalam sistem ketatanegaraan? | |||

| | work = merdeka.com | |||

| | author = Sri Wiyanti | |||

| | date = 2014-10-10 | |||

| | language = Indonesian | |||

| }}</ref>{{further|Politics of Indonesia}} | |||

| * {{flag|Iran}}: The ] has the authority to veto bills passed by the ].<ref name="iran-portal">{{Cite web | |||

| | url = https://irandataportal.syr.edu/the-guardian-council | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-11 | |||

| | title = The Guardian Council | |||

| | work = Iran Social Science Data Portal | |||

| | quote = The Guardian Council has three constitutional mandates: a) it has veto power over legislation passed by the parliament (Majles); | |||

| }}</ref> This veto power can be based on the legislation being contrary to the constitution or contrary to Islamic law. A constitutional veto requires a majority of the Guardian Council's members, while a veto based on Islamic law requires a majority of its ] members.<ref>{{Cite constitution| polity = Iran | date = 1989 | article = 94, 96}}</ref> The Guardian Council also has veto power over candidates for various elected offices.<ref name="iran-portal"/>{{further|Government of Iran}} | |||

| *{{flag|Japan}}: There is no veto at the national level, as Japan has a ] and the ] does not give the ] authority to refuse to promulgate a law.<ref>{{Cite constitution|polity=Japan|date=1947|article=7}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal | |||

| | author-last = Herzog | |||

| | author-first = Peter J. | |||

| | year = 1951 | |||

| | title = Political Theories in the Japanese Constitution | |||

| | journal = Monumenta Nipponica | |||

| | volume = 7 | |||

| | issue = 1/2 | |||

| | page = 11 | |||

| | doi = 10.2307/2382947 | |||

| | jstor = 2382947 | |||

| | quote = There is no veto power against the legislature-unless at some future time the Emperor's "non-governmental" ceremonial functions enumerated in Article 7 were construed as discretionary. | |||

| }}</ref> Under the ] of 1947, however, the executive of a prefectural or municipal government can veto local legislation. If the executive believes the legislation is unlawful, the executive is required to veto it.<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | title = Japan: Local Autonomy Is a Central Tenet to Good Governance | |||

| | author1-first = Seth B. | |||

| | author1-last = Benjamin | |||

| | author2-first = Jason | |||

| | author2-last = Grant | |||

| | date = 2022-03-29 | |||

| | url = https://icma.org/articles/article/japan-local-autonomy-central-tenet-good-governance | |||

| | access-date = 2022-06-21 | |||

| }}</ref> The local assembly can override this veto by a 2/3 vote.<ref name="shimizutani-2010">{{Cite journal | |||

| | title = Local Government in Japan: New Directions in Governance toward Citizens' Autonomy | |||

| | journal = Asia-Pacific Review | |||

| | author-first = Satoshi | |||

| | author-last = Shimizutani | |||

| | page = 114 | |||

| | year = 2010 | |||

| | volume = 17 | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| | doi = 10.1080/13439006.2010.531115 | |||

| | s2cid = 154999192 | |||

| }}</ref>{{further|Politics of Japan|Local Autonomy Act}} | |||

| * {{flag|South Korea}}: The ] can return a bill to the ] for "reconsideration" (재의).<ref>{{cite constitution |article= 53|clause= |section= 2|polity= South Korea|date= 1987}}</ref> Partial and amendatory vetoes are expressly forbidden.<ref>{{cite constitution |article= 53|clause= |section= 3|polity= South Korea|date= 1987}}</ref> The National Assembly can override the veto by a 2/3 majority of the members present.<ref>{{cite constitution |article= 53|clause= |section= 4|polity= South Korea|date= 1987}}</ref> Such overrides are rare: when the National Assembly overrode president ]'s veto of a corruption investigation in 2003, it was the first override in 49 years.<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| | author = Young Whan Kihl | |||

| | year = 2015 | |||

| | title = Transforming Korean Politics: Democracy, Reform, and Culture | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=IWqsBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA305 | |||

| | page = 305 | |||

| | publisher = Routledge | |||

| | isbn = 9781317453321 | |||

| }}</ref>{{further|Government of South Korea}} | |||

| *{{flag|Philippines}}: The ] may refuse to sign a bill, sending the bill back to the house where it originated along with his objections. ] can override the veto via a 2/3 vote with both houses voting separately, after which the bill becomes law.<ref name="rose-ackerman-2011">{{Cite journal | |||

| | author1-first = Susan | |||

| | author1-last = Rose-Ackerman | |||

| | author2-first = Diane A. | |||

| | author2-last = Desierto | |||

| | author3-first = Natalia | |||

| | author3-last = Volosin | |||

| | year = 2011 | |||

| | title = Hyper-Presidentialism: Separation of Powers without Checks and Balances in Argentina and Philippines | |||

| | volume = 29 | |||

| | journal = Berkeley Journal of International Law | |||

| | page = 282 | |||

| }}</ref> The president may also exercise a ] on ]s.<ref name="rose-ackerman-2011"/> The president does not have a pocket veto: once the bill has been received by the president, the chief executive has thirty days to veto the bill. Once the thirty-day period expires, the bill becomes law as if the president had signed it.<ref>{{Cite constitution | polity = the Philippines | date = 1987 | article = VI | section = 27}}</ref>{{further|Politics of the Philippines}} | |||

| *{{flag|Uzbekistan}}: The ] has a package veto and an amendatory veto.{{sfn|Tsebelis|Rizova|2007|p=1166}} The Legislative Chamber of the ] can override either type of veto by a 2/3 vote.{{sfn|Tsebelis|Rizova|2007|p=1166}} In the case of a package veto, if the veto is not overridden, the bill fails.{{sfn|Tsebelis|Rizova|2007|p=1166}} In the case of an amendatory veto, if the veto is not overridden, the bill becomes law as amended.{{sfn|Tsebelis|Rizova|2007|pp=1166, 1181}} The Senate of the Oliy Majlis has a veto over legislation passed by the Legislative Chamber, which the Legislative Chamber can likewise override by a 2/3 vote.<ref>{{cite constitution | article= 84 | polity= Uzbekistan | date= 1992}}</ref>{{further|Politics of Uzbekistan}} | |||

| === Europe === | |||

| The ] may refuse to grant assent to a bill that he or she considers to be unconstitutional, after consulting the ]; in this case, the bill is referred to the ], which finally determines the matter. This is the most widely used reserve power. The President may also, on request of a majority of the Senate and a third of Dáil Éireann (the lower house of parliament), after consulting the Council of State, decline to sign a bill "of such national importance that the will of the people thereon ought to be ascertained" in an ] or a new Dáil reassembling after a general election held within eight months. This latter power has never been used because the government of the day almost always commands a majority of the Senate, preventing the third of Dáil Éireann that usually makes up the opposition from combining with it. | |||

| ] | |||

| European countries in which the executive or head of state does not have a veto power include ] and ], where the power to withhold royal assent was ] in 2008.<ref>{{Cite journal | |||

| | title = Luxembourg: Parliament abolishes royal confirmation of laws | |||

| | author-first = Luc | |||

| | author-last = Frieden | |||

| | journal = International Journal of Constitutional Law | |||

| | volume = 7 | |||

| | issue = 3 | |||

| | date = July 2009 | |||

| | pages = 539–543 | |||

| | doi = 10.1093/icon/mop021 | |||

| | doi-access = free | |||

| }}</ref> Countries that have some form of veto power include the following: | |||

| *{{flag|Estonia}}: The ] may effectively veto a law adopted by the ] (legislature) by sending it back for reconsideration. The president must exercise this power within 14 days of receiving the law.<ref name="estonia-107"/> The Riigikogu, in turn, may override this veto by passing the unamended law again by a simple majority.{{sfn|Köker|2015|p=158}}<ref name="estonia-107">{{Cite constitution | polity = Estonia | article = 107 | date = 2015}}</ref> After such an override (but only then), the president may ask the ] to declare the law unconstitutional.{{sfn|Köker|2015|p=157}}<ref name="estonia-107"/> If the Supreme Court rules that the law does not violate the ], the president must promulgate the law.<ref name="estonia-107"/> From 1992 to 2010, the president exercised the veto on 1.6% of bills (59 in all), and applied for constitutional review of 11 bills (0.4% in all).{{sfn|Köker|2015|pp=86, 88}}{{further|Politics of Estonia}} | |||

| *{{flag|Finland}}: The ] has a suspensive veto, but can only delay the enactment of legislation by three months.<ref>{{Cite journal | |||

| | author-last = Paloheimo | |||

| | author-first = Heikki | |||

| | year = 2003 | |||

| | title = The Rising Power of the Prime Minister in Finland | |||

| | journal = Scandinavian Political Studies | |||

| | volume = 26 | |||

| | issue = 3 | |||

| | pages = 219–243 | |||

| |doi = 10.1111/1467-9477.00086 | |||

| }}</ref> The president has had a veto power of some kind since ] in 1919,<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| | author1-last = Raunio | |||

| | author1-first = Taupio | |||

| | author2-last = Sedelius | |||

| | author2-first = Thomas | |||

| | year = 2020 | |||

| | title = Semi-Presidential Policy-Making in Europe | |||

| | page = 57 | |||

| | doi = 10.1007/978-3-030-16431-7 | |||

| | isbn = 978-3030164331 | |||

| | s2cid = 198743002 | |||

| }}</ref> but this power was greatly curtailed by the constitutional reforms of 2000.{{further|Politics of Finland}} | |||

| *{{flag|France}}: The ] has a suspensive veto: the president can require the ] to reopen debate on a bill that it has passed, within 15 days of being presented with the bill.<ref>{{Cite constitution|polity=France|date=2008|article=10}}</ref> Aside from that, the president can only refer bills to the ], a power shared with the prime minister and the presidents of both houses of the National Assembly.<ref>{{Cite constitution|polity=France|date=2008|article=61}}</ref> Upon receiving such a referral, the Constitutional Council can strike down a bill before it has been promulgated as law, which has been interpreted as a form of constitutional veto.<ref>{{Cite journal | |||

| | author-last = Brouard | |||

| | author-first = Sylvain | |||

| | year = 2009 | |||

| | title = The Politics of Constitutional Veto in France: Constitutional Council, Legislative Majority and Electoral Competition | |||

| | journal = West European Politics | |||

| | volume = 32 | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| | pages = 384–403 | |||

| | doi = 10.1080/01402380802670719 | |||

| | s2cid = 154741100 | |||

| }}</ref>{{further|Politics of France}} | |||