| Revision as of 04:19, 13 July 2006 view sourceBharatveer (talk | contribs)4,593 edits rv-Noble eagle's version : already discussed many times over← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:10, 6 January 2025 view source EmperorÖsmanIXXVMD (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users908 edits →Sikh relationship with Punjab (via Oberoi): Nankana Sahib is in Punjab (the region). | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Sikh separatist movement in the Punjab region}}{{Redirect|Khalistan|3=Council of Khalistan}} | |||

| {{TotallyDisputed}} | |||

| {{Expert}} | |||

| {{Pp-extended|small=yes}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Use Indian English|date=August 2016}} | |||

| ]'''Khālistān''' ({{lang-pa|ਖਾਲਿਸਤਾਨ}}) (''lit.'' "The Land of the Pure") was the name given to the proposed nation-state, encompassing the present ] state of ] and all ]-speaking areas contiguous to its borders, the creation of which has been violently agitated for by separatist organisations. | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2023}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The '''Khalistan movement''' is a ] seeking to create a homeland for ] by establishing an ethno-religious ] called '''Khalistan''' ({{lit|] the ]}}) in the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last = Kinnvall |first = Catarina |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=XJzUzWDwZ4kC |title = Globalization and Religious Nationalism in India: The Search for Ontological Security |chapter = Situating Sikh and Hindu Nationalism in India |date = 2007-01-24 |publisher=Routledge |isbn = 978-1-13-413570-7 |language = en |access-date = 14 August 2015 |archive-date = 30 March 2023 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072123/https://books.google.com/books?id=XJzUzWDwZ4kC |url-status = live}}</ref> The proposed boundaries of Khalistan vary between different groups; some suggest the entirety of the Sikh-majority Indian state of ], while larger claims include ] and other parts of ] such as ], ], and ].<ref name="Crenshaw">Crenshaw, Martha, 1995, ''Terrorism in Context'', ], {{ISBN|978-0-271-01015-1}} p. 364</ref> ] and ] have been proposed as the capital of Khalistan.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Canton |first1=Naomi |date=10 June 2022 |title=Banned SFJ leader unveils 'Khalistan map', with Shimla as 'capital', before Pak press in Lahore |work=The Times of India |url=https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/banned-sjf-leader-unveils-khalistan-map-with-shimla-as-capital-before-pak-press-in-lahore/articleshow/92090727.cms |url-status=live |access-date=26 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230210065915/https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/banned-sjf-leader-unveils-khalistan-map-with-shimla-as-capital-before-pak-press-in-lahore/articleshow/92090727.cms |archive-date=10 February 2023}}</ref>{{sfn|Mehtab Ali Shah, The Foreign Policy of Pakistan|1997|pp=24–25}} | |||

| The call for a separate Sikh state began during the 1930s, when ] was nearing its end.<ref name="keith-call-homeland"/> In 1940, the first explicit call for Khalistan was made in a pamphlet titled "Khalistan".<ref>{{cite book|last1=Shani|first1=Giorgio|title=Sikh Nationalism and Identity in a Global Age|date=2007|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-10189-4|page=51|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HKu66SixH6AC&q=bhatti|quote=However, the term Khalistan was first coined by Dr V.S. Bhatti to denote an independent Sikh state in March 1940. Dr Bhatti made the case for a separate Sikh state in a pamphlet entitled 'Khalistan' in response to the Muslim League's Lahore Resolution.|access-date=19 March 2023|archive-date=30 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072134/https://books.google.com/books?id=HKu66SixH6AC&q=bhatti|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Bianchini|first1=Stefano|last2=Chaturvedi|first2=Sanjay|last3=Ivekovic|first3=Rada|last4=Samaddar|first4=Ranabir|title=Partitions: Reshaping States and Minds|date=2004|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-27654-7|page=121|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=32h_AgAAQBAJ&q=pamphlet%20forty%20pages|quote=Around the same time, a pamphlet of about forty pages, entitled 'Khalistan', and authored by medical doctor, V.S. Bhatti, also appeared.|access-date=19 March 2023|archive-date=30 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072124/https://books.google.com/books?id=32h_AgAAQBAJ&q=pamphlet%20forty%20pages|url-status=live}}</ref> With financial and political support from the ], the movement flourished in the Indian state of Punjab – which has a ] – continuing through the 1970s and 1980s, and reaching its zenith in the late 1980s. The Sikh separatist leader ] said that during his talks with ], the latter affirmed his support for the Khalistan movement in retaliation for the ], which resulted in the secession of Bangladesh from Pakistan.<ref name="ChohanIT22">{{cite news |last1=Gupta |first1=Shekhar |last2=Subramanian |first2=Nirupaman |date=15 December 1993 |title=You can't get Khalistan through military movement: Jagat Singh Chouhan |language=en |work=India Today |url=https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/interview/story/19931215-you-cant-get-khalistan-through-military-movement-says-jagat-singh-chouhan-811922-1993-12-15 |url-status=live |access-date=29 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210204070745/https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/interview/story/19931215-you-cant-get-khalistan-through-military-movement-says-jagat-singh-chouhan-811922-1993-12-15 |archive-date=4 February 2021}}</ref> | |||

| A Sarbat Khalsa (general congregation of the Sikh people) was convened at the ], the Sikh seat of temporal authority in ], on ], ]. The gathering passed a resolution (''gurmattā'') favouring the creation of Khalistan. Khalistan was envisaged by its proponents as a ] state.<ref> Singh, Kapur, “Golden Temple and Its Theo-political Status,” (last accessed May 20, 2004). Historically, all Sikh states have been based on secular, non-theocratic laws because the Sikhs neither have a priestly class, which may rule in the name of an invisible God, nor do they have a corpus of civil law of divine origin and sanction.</ref> The Khalistan movement and the violence it entailed claimed the lives of a total of 11,694 civilians between 1981-1993, including 7,139 Sikhs<ref> Gill K.P.S., Punjab: The Knights of Falsehood</ref>. The movement lost its support amongst the people in the 1990s <ref> Weiss, M., "The Khalistan Movement in Punjab." Yale Center for International and Area Studies, June 2002. http://www.yale.edu/ycias/globalization/punjab.pdf</ref> | |||

| ==Causes of conflict== | |||

| {{splitsection}} | |||

| ===Sikh representation in India=== | |||

| With the possibility of an end to British colonialism in sight, the Sikh leadership became concerned about the future of the Sikhs. The Sikhs and the Muslims had unsuccessfully sought separate representation for their communities in the Minto-Morley Scheme of 1909.<ref>Singh, Iqbal, Punjab Under Siege: A Critical Analysis, New York: Allen, McMillan and Enderson, 1986, p. 35</ref> The ], which had a predominantly Hindu leadership, denied Sikhs a separate identity and labelled them a sect of Hinduism. Indeed, in a document written in response to the Simon Commission (1927), the Congress leader ] defined the future of British India in terms of the Hindu and Muslim communities alone, despite the fact that Sikhs occupied 19.1 percent of the seats in the Punjab Legislature.<ref>Singh, Iqbal, Punjab Under Siege: A Critical Analysis, New York: Allen, McMillan and Enderson, 1986, p. 36</ref> Nehru’s report evoked strong condemnation from Sikh leaders. | |||

| The separatist ] started in the early 1980s.<ref name="HT_New2018" /><ref name="india-canada-list">{{cite news |date=22 February 2018 |title=India gives Trudeau list of suspected Sikh separatists in Canada |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-canada-trudeau/india-gives-trudeau-list-of-suspected-sikh-separatists-in-canada-idUSKCN1G61K7 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210203234341/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-canada-trudeau/india-gives-trudeau-list-of-suspected-sikh-separatists-in-canada-idUSKCN1G61K7 |archive-date=3 February 2021 |access-date=22 May 2018 |work=Reuters |quote=The Sikh insurgency petered out in the 1990s. He told state leaders his country would not support anyone trying to reignite the movement for an independent Sikh homeland called Khalistan.}}</ref> Several ] were involved in the armed insurgency, including ] and ], among others.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Fair |first1=C. Christine |title=Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies: Insights from the Khalistan and Tamil Eelam Movements |journal=Nationalism and Ethnic Politics |date=2005 |volume=11 |pages=125–156 |doi=10.1080/13537110590927845|s2cid=145552863|issn = 1353-7113 }}</ref> In 1986, ] took responsibility for the assassination of General ], in retaliation for 1984's ].<ref name="topgeneralassasinated">Weisman, Steven R. "A Top Indian General is Assassinated", '']'', 11 August 1986.</ref><ref name="vaidyamurdercase">"The Vaidya Murder Case: Confirming Death Sentences", '']''. (New York edition). New York, N.Y.: 24 July 1992. Vol.XXII, Issue. 43; pg.20.</ref> By the mid-1990s, the | |||

| ] was introduced in 1935, guaranteeing a majority for Muslims in Punjab; political expediency now dictated a change in Hindu attitudes towards the Sikh demand for separate electorates. The Hindus aimed to reduce the Muslim majority in the Punjab Legislative Council.<ref>Singh, Iqbal, Punjab Under Siege: A Critical Analysis, New York: Allen, McMillan and Enderson, 1986, p. 36</ref> At this time, the Hindus not only accepted the Sikhs as a community distinct from themselves, but also supported the Sikh demand for adequate political representation. In December 1929, Sikh leaders were assured by Motilal Nehru and ] that Congress would accept no political settlement of the future of British India unless it proved agreeable to the Sikhs.<ref>Singh, Iqbal, Punjab Under Siege: A Critical Analysis, New York: Allen, McMillan and Enderson, 1986, 1999, p. 36.</ref> Accordingly, the Congress passed the following resolution during its Lahore session (1929): | |||

| insurgency petered out, with the last major incident being the ], who was killed in a bomb blast by a member of ].<ref>{{cite news|title=Punjab on edge over hanging of Beant Singh's killer Bhai Balwant Singh Rajoana |url=http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/punjab-on-edge-beant-singh-balwant-singh-rajoana/1/179691.html |access-date=28 March 2012 |newspaper=India Today |date=28 March 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120329042658/http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/punjab-on-edge-beant-singh-balwant-singh-rajoana/1/179691.html |archive-date=29 March 2012 }}</ref> The movement failed to reach its objective for multiple reasons, including violent police crackdowns on separatists, factional infighting, and disillusionment from the Sikh population.<ref name="HT_New2018" />{{sfnp|Van Dyke, The Khalistan Movement|2009|p=990}} | |||

| There is some support within India and the Sikh diaspora, with yearly demonstrations in protest of those killed during ].<ref>{{cite web|last1=Ali|first1=Haider|title=Mass protests erupt around Golden Temple complex as pro-Khalistan sikhs mark Blue Star anniversary|url=https://en.dailypakistan.com.pk/world/mass-protests-erupt-around-golden-temple-complex-as-pro-khalistan-sikhs-mark-blue-star-anniversary/|publisher=Daily Pakistan|date=6 June 2018|access-date=25 June 2018|archive-date=6 July 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200706201236/https://en.dailypakistan.com.pk/06-Jun-2018/mass-protests-erupt-around-golden-temple-complex-as-pro-khalistan-sikhs-mark-blue-star-anniversary|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=UK: Pakistani-origin lawmaker leads protests in London to call for Kashmir, Khalistan freedom|url=https://scroll.in/latest/866573/uk-pakistani-origin-lawmaker-leads-protests-in-london-to-call-for-kashmir-khalistan-freedom|website=Scroll|date=27 January 2018 |access-date=29 June 2018|archive-date=3 February 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210203233201/https://scroll.in/latest/866573/uk-pakistani-origin-lawmaker-leads-protests-in-london-to-call-for-kashmir-khalistan-freedom|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last1=Bhattacharyya|first1=Anirudh|title=Pro-Khalistan groups plan event in Canada to mark Operation Bluestar anniversary|url=https://www.hindustantimes.com/world-news/pro-khalistan-groups-plan-event-in-canada-to-mark-operation-bluestar-anniversary/story-g6TtIBu1JXinwhvaQe0F5N.html|work=Hindustan Times|access-date=6 July 2018|date=5 June 2017|archive-date=4 February 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210204024553/https://www.hindustantimes.com/world-news/pro-khalistan-groups-plan-event-in-canada-to-mark-operation-bluestar-anniversary/story-g6TtIBu1JXinwhvaQe0F5N.html|url-status=live}}</ref> In early 2018, some militant groups were arrested by police in Punjab, India.<ref name="HT_New2018">{{cite news|title=New brand of Sikh militancy: Suave, tech-savvy pro-Khalistan youth radicalised on social media|url=https://www.hindustantimes.com/opinion/a-new-brand-of-sikh-militancy-rears-its-head/story-JH3XbAGk6sSxlYrVEDyISK.html|newspaper=Hindustan Times|access-date=27 April 2018|archive-date=4 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210304040341/https://www.hindustantimes.com/opinion/a-new-brand-of-sikh-militancy-rears-its-head/story-JH3XbAGk6sSxlYrVEDyISK.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Former ] ] claimed that the recent extremism is backed by Pakistan's ] (ISI) and "Khalistani sympathisers" in ], ], and the ].<ref name="OutlookAmarinder">{{cite news|last1=Majumdar|first1=Ushinor|title=Sikh Extremists in Canada, The UK And Italy Are Working With ISI Or Independently|url=https://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/story/sikh-extremists-in-canada-the-uk-and-italy-are-working-with-isi-or-independently/299753|newspaper=Outlook India|quote=Q. Is it clear which "foreign hand" is driving this entire nexus? A. Evidence gathered by the police and other agencies points to the ISI as the key perpetrator of extremism in Punjab. (Amarinder Singh Indian Punjab Chief Minister)|access-date=8 June 2018|archive-date=20 July 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190720213325/https://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/story/sikh-extremists-in-canada-the-uk-and-italy-are-working-with-isi-or-independently/299753|url-status=live}}</ref> ] is currently the only pro-Khalistan party recognised by the ]. As of 2024, two seats in the Indian Parliament are held by ], an incarcerated pro-Khalistan activist, and ], who is the son of the assassin of former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.<ref name="Dedicates">{{citation |title=Simranjit Singh Mann stokes row, dedicates Sangrur win to Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale: Know about pro-Khalistan leader |url=https://www.firstpost.com/politics/simranjit-singh-mann-stokes-row-dedicates-sangrur-win-to-jarnail-singh-bhindranwale-know-about-pro-khalistan-leader-10840911.html |access-date=27 June 2022 |work=] |date=27 June 2022 |language=en |archive-date=27 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220627072635/https://www.firstpost.com/politics/simranjit-singh-mann-stokes-row-dedicates-sangrur-win-to-jarnail-singh-bhindranwale-know-about-pro-khalistan-leader-10840911.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{citation |date=2022-06-26 |title=Sangrur Bypoll Results Live: AAP loses Bhagwant Mann's seat, SAD-A wins by 6,800 votes |url=https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/sangrur-by-election-results-2022-live-updates-counting-of-votes-lok-sabha-bypoll-results-in-punjab-101656210234523.html |access-date=2022-06-26 |work=] |language=en |archive-date=26 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220626091844/https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/sangrur-by-election-results-2022-live-updates-counting-of-votes-lok-sabha-bypoll-results-in-punjab-101656210234523.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>"...as the Sikhs in particular, and Muslims and other minorities in general, have expressed dissatisfaction over the solution of communal questions proposed in the Nehru Report, this Congress assures the Sikhs, the Muslims and other minorities that no solution thereof in any future constitution will be acceptable to the Congress that does not give full satisfaction to the parties concerned.<ref>Quoted in Singh, Iqbal, Punjab Under Siege: A Critical Analysis, New York: Allen, McMillan and Enderson, 1986, 1999, p. 36.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| == Pre-1950s == | |||

| ===Congress Assurances and Subsequent Repudiation=== | |||

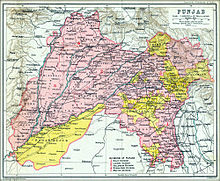

| ]'s ] at its peak in c. 1839; most of its territory in the Punjab plain is currently under ]]] | |||

| ] reiterated Gandhi’s assurance to the Sikhs at the ] meeting in ] in 1946. He declared: | |||

| Sikhs have been concentrated in the ] of ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Wallace |first1=Paul |title=The Sikhs as a "Minority" in a Sikh Majority State in India |journal=Asian Survey |date=1986 |volume=26 |issue=3 |pages=363–377 |doi=10.2307/2644197 |jstor=2644197 |issn=0004-4687|quote=Over 8,000,000 of India's 10,378,979 Sikhs were concentrated in Punjab}}</ref> Before its conquest by the British, the region around Punjab had been ruled by the confederacy of ]s. The Misls ruled over the eastern Punjab from 1733 to 1799,{{sfnp|Jolly, Sikh Revivalist Movements|1988|p=6}} until their confederacy was unified into the ] by ] from 1799 to 1849.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Purewal |first1=Navtej K. |title=Living on the Margins: Social Access to Shelter in Urban South Asia |date=2017 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-351-74899-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JFM8DwAAQBAJ&dq=Maharaja+Ranjit+Singh+unified&pg=PT68 |language=en |quote=The wrangling between various Sikh groupings were resolved by the nineteenth century when Maharajah Ranjit Singh unified the Punjab from Peshawar t the Sutluj River. |access-date=19 March 2023 |archive-date=30 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072117/https://books.google.com/books?id=JFM8DwAAQBAJ&dq=Maharaja+Ranjit+Singh+unified&pg=PT68 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote> The brave Sikhs of Punjab are entitled to special consideration. I see nothing wrong in an area and a set-up in the north wherein the Sikhs can experience the glow of freedom.<ref>The Statesman, Calcutta, ], ] quoting Jawaharlal Nehru in Singh, Iqbal, Punjab Under Siege: A Critical Analysis, New York: Allen, McMillan and Enderson, 1986, p. 37.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| At the end of the ] in 1849, the Sikh Empire was dissolved into separate ]s and the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Panton |first1=Kenneth J. |title=Historical Dictionary of the British Empire |date=2015 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=978-0-8108-7524-1 |pages=470 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WdFbCQAAQBAJ&dq=sikh+empire+british&pg=PA470 |language=en |quote=A second conflict, just two years later, led to complete subjugation of the Sikhs and the incorporation of the remainder of their lands |access-date=19 March 2023 |archive-date=30 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072126/https://books.google.com/books?id=WdFbCQAAQBAJ&dq=sikh+empire+british&pg=PA470 |url-status=live }}</ref> In newly conquered regions, "religio-nationalist movements emerged in response to British {{'}}]{{'}} administrative policies, the perceived success of Christian missionaries converting Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims, and a general belief that the solution to the downfall among India's religious communities was a grassroots religious revival."{{sfnp|Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies|2005|p=127}} | |||

| With the Muslims proposing the creation of ] to safeguard their interests, some Sikhs put forth the idea of likewise carving out a Sikh state, Khalistan.<ref>For instance, in 1940, Dr. Vir Singh Bhatti demanded the formulation of the Sikh state of Khalistan as a buffer state between Muslim Pakistan and Hindu India.</ref> In the 1940s, a prolonged negotiation transpired between the British and the three Indian groups seeking political power, namely, the Hindus, the Muslims and the Sikhs. During this period, the Congress Party continually extended assurances designed to prevent Sikhs from allying with the Muslim League. To win Sikh support, Jawaharlal Nehru again declared: | |||

| As the British Empire began to dissolve in the 1930s, Sikhs made their first call for a Sikh homeland.<ref name="keith-call-homeland">{{cite book |last1=Axel |first1=Brian Keith |title=The Nation's Tortured Body: Violence, Representation, and the Formation of a Sikh "Diaspora" |date=2001 |publisher=Duke University Press |isbn=978-0-8223-2615-1 |pages=84 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Gj8yJsixw8QC&dq=akali+dal+khalistan+1930s&pg=PA84 |language=en |quote=The call for a Sikh homeland was first made in the 1930s, addressed to the quickly dissolving empire. |access-date=19 March 2023 |archive-date=30 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072138/https://books.google.com/books?id=Gj8yJsixw8QC&dq=akali+dal+khalistan+1930s&pg=PA84 |url-status=live }}</ref> When the ] of the ] demanded Punjab be made into a Muslim state, the ] viewed it as an attempt to usurp a historically Sikh territory.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Axel |first1=Brian Keith |title=The Nation's Tortured Body: Violence, Representation, and the Formation of a Sikh "Diaspora" |date=2001 |publisher=Duke University Press |isbn=978-0-8223-2615-1 |pages=85 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Gj8yJsixw8QC&dq=akali+dal+khalistan+1930s&pg=PA84 |language=en |quote=The Akalis viewed the Lahore Resolution and the Cripps Mission as a betrayal of the Sikhs and an attempt to usurp what, since the time of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, was historically a Sikh territory. |access-date=19 March 2023 |archive-date=30 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072138/https://books.google.com/books?id=Gj8yJsixw8QC&dq=akali+dal+khalistan+1930s&pg=PA84 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{citation |last1=Tan |first1=Tai Yong |author-link1=Tan Tai Yong |last2=Kudaisya |first2=Gyanesh |author-link2=Gyanesh Kudaisya |year=2005 |orig-year=First published 2000 |title=The Aftermath of Partition in South Asia |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aPOBAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA100 |publisher=Routledge |page=100 |isbn=978-0-415-28908-5 |quote=The professed intention of the Muslim League to impose a Muslim state on the Punjab (a Muslim majority province) was anathema to the Sikhs ... the Sikhs launched a virulent campaign against the Lahore Resolution ... Sikh leaders of all political persuasions made it clear that Pakistan would be 'wholeheartedly resisted'.}}</ref> In response, the Sikh party ] argued for a community that was separate from Hindus and Muslims.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Axel |first1=Brian Keith |title=The Nation's Tortured Body: Violence, Representation, and the Formation of a Sikh "Diaspora" |date=2001 |publisher=Duke University Press |isbn=978-0-8223-2615-1 |pages=84 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Gj8yJsixw8QC&dq=akali+dal+khalistan+1930s&pg=PA84 |language=en |quote=Against the nationalist ideology of a united India, which called for all groups to set aside "communal" differences, the Shiromani Akali Dal Party of the 1930s rallied around the proposition of a Sikh panth (community) that was separate from Hindus and Muslims. |access-date=19 March 2023 |archive-date=30 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072138/https://books.google.com/books?id=Gj8yJsixw8QC&dq=akali+dal+khalistan+1930s&pg=PA84 |url-status=live }}</ref> The Akali Dal imagined Khalistan as a ] state led by the ] with the aid of a cabinet consisting of the representatives of other units.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Shani |first1=Giorgio |title=Sikh Nationalism and Identity in a Global Age |date=2007 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-134-10189-4 |pages=52 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HKu66SixH6AC&dq=shani+theocratic+state+khalistan&pg=PA52 |language=en |quote=Khalistan was imagined as a theocratic state, a mirror-image of 'Muslim' Pakistan, led by the Maharaja of Patiala with the aid of a cabinet consisting of representing federating units. |access-date=19 March 2023 |archive-date=30 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072207/https://books.google.com/books?id=HKu66SixH6AC&dq=shani+theocratic+state+khalistan&pg=PA52 |url-status=live }}</ref> The country would include parts of present-day ], present-day ] (including ]), and the ] ].<ref>{{citation |title=The Foreign Policy of Pakistan: Ethnic Impacts on Diplomacy 1971–1994 |last=Shah |first=Mehtab Ali |date=1997 |publisher=I.B.Tauris |isbn=978-1-86064-169-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7czT4fipTyoC&q=khalistan+lahore&pg=PA25 |access-date=5 October 2020 |archive-date=30 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072122/https://books.google.com/books?id=7czT4fipTyoC&q=khalistan+lahore&pg=PA25 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>Redistribution of provincial boundaries was essential and inevitable. I stand for semi-autonomous units…if the Sikhs desire to function as such a unit, I would like them to have a semi-autonomous unit within the province so that they may have a sense of freedom.”<ref>Congress Records, quoted in Singh, Iqbal, Punjab Under Siege: A Critical Analysis, New York: Allen, McMillan and Enderson, 1986, p. 38.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| === Partition of India, 1947 === | |||

| These pledges, made by Nehru and Gandhi on behalf of the Congress party, were formalised through a resolution passed by the Indian Constituent Assembly on ], ]. This resolution stated ''inter alia'' that: | |||

| ], in 1909]] | |||

| Before the 1947 ], Sikhs were not in majority in any of the districts of pre-partition ] other than ] (where Sikhs formed 41.6% of the population).<ref>{{citation|last1=Hill|first1=K.|title=A Demographic Case Study of Forced Migration: The 1947 Partition of India|date=2003|url=http://paa2004.princeton.edu/download.asp?submissionId=41274|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081206171954/http://paa2004.princeton.edu/download.asp?submissionId=41274|publisher=Harvard University Asia Center|archive-date=6 December 2008|last2=Seltzer|first2=W.|last3=Leaning|first3=J.|last4=Malik|first4=S.J.|last5=Russell|first5=S. S.|last6=Makinson|first6=C.}}</ref> Rather, districts in the region had a majority of either the Hindus or Muslims depending on its location in the province. | |||

| ] was partitioned on a religious basis in 1947, where the Punjab province was divided between India and the newly created Pakistan. As result, a majority of Sikhs, along with the Hindus, migrated from the Pakistani region to India's Punjab, which included present-day ] and ]. The Sikh population, which had gone as high as 19.8% in some Pakistani districts in 1941, dropped to 0.1% in Pakistan, and rose sharply in the districts assigned to India. However, they would still be a minority in the Punjab province of India, which remained a Hindu-majority province.<ref name="WHM_Sikhs_1991">{{citation |last=McLeod |first=W. H. |title=The Sikhs: History, Religion, and Society |url=https://archive.org/details/sikhshistoryreli00mcle |year=1989 |publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn=978-0-231-06815-4}}</ref>{{page needed|date=December 2018}} | |||

| <blockquote>Adequate safeguards would be provided for minorities in India…It was a declaration, pledge and an undertaking before the world, a contract with millions of Indians and, therefore, in the nature of an oath we must keep.<ref>Quoted in Singh, Iqbal, Punjab Under Siege: A Critical Analysis, New York: Allen, McMillan and Enderson, 1986, p. 38.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| === Sikh relationship with Punjab (via Oberoi) === | |||

| During a press conference on ], ] in ], Nehru made a controversial statement to the effect that the Congress may “change or modify” the federal arrangement agreed upon for independent India; this came “as a bombshell” to many.<ref>Singh, Iqbal, Punjab Under Siege: A Critical Analysis, New York: Allen, McMillan and Enderson, 1986, p. 38.</ref> As a consequence, ], leader of the ], declared himself impelled to seek the creation of a separate state, Pakistan, in order to safeguard the interests of his community. | |||

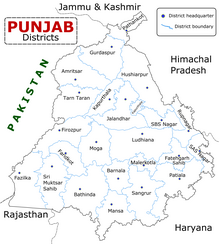

| ]. Following the partition, ] (including ]) was divided in 1966 with the formation of the new states of ] and ] as well as the current state of Punjab. Punjab is the only state in India with a majority Sikh population.]] | |||

| After the departure of the British, the Congress Party would repudiate all pledges and ] resolutions promulgated to safeguard Sikh interests.<ref>PSingh, Iqbal, Punjab Under Siege: A Critical Analysis, New York: Allen, McMillan and Enderson, 1986, p. 38-39.</ref> Many Sikhs felt that they had been tricked into joining the Indian union. On ], ], during the review of the draft of the ], Hukam Singh, a Sikh representative, declared to the Constituent Assembly: | |||

| Sikh historian ] argues that, despite the historical linkages between Sikhs and Punjab, territory has never been a major element of Sikh self-definition. He makes the case that the attachment of Punjab with Sikhism is a recent phenomenon, stemming from the 1940s.{{sfnp|Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies|2005|p=129}} Historically, ] has been pan-Indian, with the ] (the main scripture of Sikhism) drawing from works of saints in both North and South India, while several major seats in Sikhism (e.g. ] in ] and ] in ]) are located outside of Punjab.<ref>{{Cite web|date=1999-11-30|title=Gurudwaras Outside of Punjab State|url=https://www.allaboutsikhs.com/gurudwaras/gurudwaras-in-india/gurudwaras-outside-of-punjab-state-v15-2736/|access-date=2020-10-17|website=Gateway To Sikhism|language=en-US|archive-date=2 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210302180228/https://www.allaboutsikhs.com/gurudwaras/gurudwaras-in-india/gurudwaras-outside-of-punjab-state-v15-2736/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Oberoi makes the case that Sikh leaders in the late 1930s and 1940s realized that the dominance of ] and of ] was imminent. To justify a separate Sikh state within the Punjab, Sikh leaders started to mobilize meta-commentaries and signs to argue that Punjab belonged to Sikhs and Sikhs belong to Punjab. This began the territorialization of the Sikh community.{{sfnp|Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies|2005|p=129}} | |||

| <blockquote>Naturally, under these circumstances, as I have stated, the Sikhs feel utterly disappointed and frustrated. They feel that they have been discriminated against. Let it not be misunderstood that the Sikh community has agreed to this Constitution. I wish to record an emphatic protest here. My community cannot subscribe its assent to this historic document.<ref>Singh, Gurmit, History of Sikh Struggles, New Delhi: South Asia Books, 1989, p. 110-111</ref></blockquote> | |||

| This territorialization of the Sikh community would be formalized in March 1946, when the Sikh political party of ] passed a resolution proclaiming the natural association of Punjab and the Sikh religious community.{{sfnp|Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies|2005|p=130}} Oberoi argues that despite having its beginnings in the early 20th century, Khalistan as a separatist movement was never a major issue until the late 1970s and 1980s when it began to militarize.{{sfnp|Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies|2005|p=128}} | |||

| ===Growth of Sikh national consciousness (1947-1966)=== | |||

| The Sikhs, whose participation in India’s independence struggle was disproportionate to their small numbers (see Table 1), were labelled as a "criminal tribe" in postcolonial India. According to Kapur Singh, who was the Deputy Commissioner at Dalhousie and a member of the ] (ICS) at the time: | |||

| ==1950s to 1970s== | |||

| <blockquote>In 1947, the governor of Punjab, Mr. C.M. Trevedi, in deference to the wishes of the Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru and Sardar Patel, the Deputy Prime Minister, issued certain instructions to all the Deputy Commissioners of Indian Punjab…These were to the effect that, without reference to the law of the land, the Sikhs in general and Sikh migrants in particular must be treated as a “criminal tribe”. Harsh treatment must be meted out to them…to the extent of shooting them dead so that they wake up to the political realities and recognise “who are the rulers and who the subjects.” <ref>Singh, Kapur, Sachi Sakhi, Amritsar: SGPC, 1993, p. 4-5. Kapur Singh was one of the officials who received a copy of the memorandum and speaks as an insider.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| There are two distinct narratives about the origins of the calls for a sovereign Khalistan. One refers to the events within India itself, while the other privileges the role of the ]. Both of these narratives vary in the form of governance proposed for this state (e.g. ] vs ]) as well as the proposed name (i.e. Sikhistan vs Khalistan). Even the precise geographical borders of the proposed state differs among them although it was generally imagined to be carved out from one of various historical constructions of the Punjab.{{sfnp|Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies|2005|p=134}} | |||

| ] summed up Sikh sentiments in his Presidential Address to the All India Sikh Conference on March 28, 1953: | |||

| === Emergence in India === | |||

| <blockquote>English-man has gone, but our liberty has not come. For us the so-called liberty is simply a change of masters, black for white. Under the garb of democracy and secularism, our Panth, our liberty and our religion are being crushed.<ref>Kapur, Anup Chand, The Punjab Crisis, New Delhi: S. Chand, 1985, p. 45.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| {{see also|Punjabi Suba movement}} | |||

| Established on 14 December 1920, ] was a Sikh political party that sought to form a government in Punjab.<ref name=":1">Jetly, Rajshree. 2006. "The Khalistan Movement in India: The Interplay of Politics and State Power." ''International Review of Modern Sociology'' 34(1):61–62. {{JSTOR|41421658}}.</ref> | |||

| Following the 1947 independence of India, the ], led by the Akali Dal, sought the creation of a province ('']'') for ]. The Akali Dal's maximal position of demands was a ] (i.e. Khalistan), while its minimal position was to have an ] within India.{{sfnp|Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies|2005|p=134}} The issues raised during the Punjabi Suba movement were later used as a premise for the creation of a separate Sikh country by proponents of Khalistan. | |||

| ===Language issues=== | |||

| In the 1950s and 1960s, central government proposed to declare ] as the national language. This invoked vehement opposition in Punjab. The ], the party representing the Sikhs in Punjab, initiated an agitation in August 1950. The agitation lasted for over two decades. The Akali Dal sought to create a Punjabi suba, a Punjabi-speaking state. The case in favour of this was presented to the States Reorganisation Commission established in 1953. The Akali Dal’s manifesto declared: | |||

| As the religious-based partition of India led to much bloodshed, the Indian government initially rejected the demand, concerned that creating a Punjabi-majority state would effectively mean yet again creating a state based on religious grounds.<ref name="Tribune_Relations_2003">{{cite news |url=http://www.tribuneindia.com/2003/20031103/edit.htm#5 |title=Hindu-Sikh relations – I |newspaper=The Tribune |location=Chandigarh, India |publisher=Tribuneindia.com |date=3 November 2003 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110605231120/http://www.tribuneindia.com/2003/20031103/edit.htm#5 |archive-date=5 June 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>Chawla, Muhammad Iqbal. 2017. ''The Khalistan Movement of 1984: A Critical Appreciation''. | |||

| <blockquote>The true test of democracy, in the opinion of the Shiromani Akali Dal, is that the minorities should feel that they are really free and equal partners in the destiny of their country...to bring home a sense of freedom to the Sikhs, it is vital that there should be a Punjabi speaking language and culture. This will not only be in fulfillment of the pre-partition Congress programme and pledges, but also in entire conformity with the universally recognised principles governing formation of provinces…The Shiromani Akali Dal has reason to believe that a Punjabi-speaking province may give the Sikhs the needful security. It believes in a Punjabi speaking province as an autonomous unit of India.”<ref>Quoted in ibid, p. 94.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| </ref> | |||

| On 7 September 1966, the ] was passed in Parliament, implemented with effect beginning 1 November 1966. Accordingly, Punjab was divided into the state of Punjab and ], with certain areas to ]. ] was made a centrally administered ].<ref name="india_gov_PRA_1966">{{cite web |url=http://india.gov.in/allimpfrms/allacts/474.pdf |title=The Punjab Reorganisation Act, 1966 |publisher=Government of India |date=18 September 1966 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120119110225/http://india.gov.in/allimpfrms/allacts/474.pdf |archive-date=19 January 2012 }}</ref> While the ] led by ] agreed with the creation of Punjab state but refused to make Chandigarh as its capital and also refused to make it autonomous. The outcome of the Punjabi Suba movement failed to meet demands of its leaders.<ref>{{cite book | author=] | title=India | publisher=] Press | year=2005 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HmkL1tp2Nl4C | page=216 | isbn=9780520246966 | access-date=11 March 2023 | archive-date=30 March 2023 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072125/https://books.google.com/books?id=HmkL1tp2Nl4C | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The nationwide movement of linguistic groups seeking statehood resulted in a massive reorganisation of provincial boundaries based on the principle of common language in 1956. However, ], ] and ] were the only three languages not considered for statehood.<ref>Deol, Harnik, Religion and Nationalism in India: The Case of the Punjab, London: Routledge, 2000, p. 93.</ref> | |||

| ====Anandpur Resolution==== | |||

| A section of the Hindus were opposed to the adoption of Punjabi as an official language in the Punjabi-speaking areas. This created a rift between Hindus and Sikhs of Punjab and took its toll on the relations between the Akali Dal and the Congress government.The States Reorganization Commission, declining to recognize Punjabi as a language that was distinct grammatically from Hindi, rejected the demand for the creation of a Punjabi suba or state. Another reason cited by the Commission for its refusal to recommend the creation of such a state was the alleged lack of general support for the proposal from people inhabiting the region, a reference to the Punjabi Hindus who were opposed to the creation of a Punjabi-speaking state.<ref>Ibid, p. 95.</ref> The Sikhs felt discriminated against by the commission. Hukam Singh of the Akali Dal wrote, “While others got States for their languages, we lost even our language.”<ref>Quoted in ibid, p. 95.</ref> The Akali Dal saw the refusal of the Commission to concede Sikh demands as a sign of intolerance against a religious community that spoke a distinct language, which was both linguistically and lexically distinct from Hindi.<ref>Ibid, p. 95.</ref>. | |||

| {{see also|Anandpur Sahib Resolution}} | |||

| As Punjab and Haryana now shared the capital of Chandigarh, resentment was felt among Sikhs in Punjab.<ref name=":1" /> Adding further grievance, a canal system was put in place over the rivers of ], ], and ], which flowed through Punjab, in order for water to also reach Haryana and ]. As result, Punjab would only receive 23% of the water while the rest would go to the two other states. The fact that the issue would not be revisited brought on additional turmoil to Sikh resentment against Congress.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| The Akali Dal was defeated in the ].<ref name="Mitra_Puzzle">{{citation|last1=Mitra|first1=Subrata K.|title=The Puzzle of India's Governance: Culture, Context and Comparative Theory|date=2007|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GuILNHwcT4AC&pg=PA94|page=94|location=Advances in South Asian Studies|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-27493-2|access-date=6 March 2018|archive-date=30 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072125/https://books.google.com/books?id=GuILNHwcT4AC&pg=PA94|url-status=live}}</ref> To regain public appeal, the party put forward the ] in 1973 to demand radical devolution of power and further autonomy to Punjab.<ref>{{citation|last=Singh|first=Khushwant|title=A History of the Sikhs: Volume 2: 1839–2004|year=2004|chapter=The Anandpur Sahib Resolution and Other Akali Demands|publisher=Oxford University Press|doi=10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195673098.001.0001|isbn=978-0-19-567309-8}}</ref> The resolution document included both religious and political issues, asking for the recognition of Sikhism as a religion separate from Hinduism, as well as the transfer of ] and certain other areas to Punjab. It also demanded that power be radically devolved from the central to state governments.<ref name="Jayanta484">{{citation|last1=Ray|first1=Jayanta Kumar|title=Aspects of India's International Relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World|date=2007|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Nyk6oA2nOlgC&q=khalistan|page=484|publisher=Pearson Education India|isbn=978-81-317-0834-7|access-date=16 August 2019|archive-date=30 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072148/https://books.google.com/books?id=Nyk6oA2nOlgC&q=khalistan|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Akal Takht movement=== | |||

| The Akal Takht played a vital role in organizing Sikhs to campaign for the Punjabi suba. During the course of the campaign, twelve thousand Sikhs were arrested for their peaceful demonstrations in 1955 and twenty-six thousand in 1960-61.<ref>Ibid, p. 96.</ref> Finally, in September 1966, the Punjabi suba demand was accepted by the central government and Punjab was trifurcated under the Punjab State Reorganisation Bill. Areas in the south of Punjab that spoke a language that is a derivative of ] formed a new state of ] and the ]- and ]-speaking districts north of Punjab were merged with ], while the remaining areas formed a new state of Punjab. As a result, the Sikhs became a majority in the newly created Punjabi suba with a population of a little over sixty percent. | |||

| The document was largely forgotten for some time after its adoption until gaining attention in the following decade. In 1982, the Akali Dal and ] joined hands to launch the Dharam Yudh Morcha in order to implement the resolution. Thousands of people joined the movement, feeling that it represented a real solution to such demands as larger shares of water for irrigation and the return of Chandigarh to Punjab.<ref name="Akshay1991">{{cite book|author=Akshayakumar Ramanlal Desai|title=Expanding Governmental Lawlessness and Organized Struggles|year=1991|pages=64–66|publisher=Popular Prakashan|isbn=978-81-7154-529-2}}</ref> | |||

| ===The Nirankari-Sikh Clashes=== | |||

| Tensions had been escalating between the Sikhs and Nirankaris for some time. Finally, in April 1978, a convention of Nirankaris was attacked by a few hundred Sikhs, led by Bhindranwale and by Fauja Singh of the Akhand Kirtani Jatha. On the way, they hacked off the arm of a Hindu sweetmeats seller. This was regarded as probably the first act of terrorist violence in Punjab. On arriving at the convention, Fauja Singh tried to behead the Nirankari leader with his sword but was shot by the leader's bodyguard. The brawl that ensued thereafter, left 13 of the raiding party dead, including two of Bhindranwale’s followers. Another eleven of the Akhand Kirtani Jatha were killed. Three Nirankaris were also killed. Bhindranwale himself was reported to have fled the scene just as the violence broke out which damaged relations between him and the Akhand Kirtani Jatha. Fauja Singh’s widow often blamed him for her husband’s death. It was also alleged that the then ruling government in Punjab did little to avoid the violence despite having enough grounds to believe that such a violence would take place. | |||

| ===Emergence in the diaspora=== | |||

| Sixty two Nirankaris, including the head of the sect, Baba Gurbachan Singh were charged in connection with the killing of the 13 Sikhs in the clash. They faced trial and were acquitted on the grounds that they had acted in self defence. This irked the sikhs and in April 1980 Baba Gurbachan Singh was shot dead in retaliation. Twenty persons, including Jarnail Singh Bhindrawale were charged with the murder. All of them were later set free upon a announcement by the then Home Minister of India, Giani Zail Singh, that Bhindrawale was not involved in the murder. Apparently, there was no trial or investigation. | |||

| According to the 'events outside India' narrative, particularly after 1971, the notion of a sovereign and independent state of Khalistan began to get popularized among Sikhs in ] and ]. One such account is provided by the Khalistan Council which had moorings in ], where the Khalistan movement is said to have been launched in 1970.{{sfnp|Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies|2005|p=134}} | |||

| Davinder Singh Parmar migrated to London in 1954. According to Parmar, his first pro-Khalistan meeting was attended by less than 20 people and he was labelled as a madman, receiving only one person's support. Parmar continued his efforts despite the lack of following, eventually raising the Khalistani flag in ] in the 1970s.{{sfnp|Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies|2005|p=135}} In 1969, two years after losing the Punjab Assembly elections, Indian politician ] moved to the ] to start his campaign for the creation of Khalistan.<ref name="NYT_Chohan_Dies">{{cite news|last=Pandya|first=Haresh|date=11 April 2007|title=Jagjit Singh Chauhan, Sikh Militant Leader in India, Dies at 80|work=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/11/world/asia/11chauhan.html|access-date=17 February 2017|archive-date=20 December 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161220150041/http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/11/world/asia/11chauhan.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Chohan's proposal included Punjab, Himachal, Haryana, as well as some parts of ].<ref name=":2">{{harvp|Axel, The Nation's Tortured Body|2011|pp=101–}}</ref> | |||

| ===River waters dispute=== | |||

| Before the creation of the Punjabi suba, Punjab was the master of its river waters, as per the provisions of the Indian constitution<ref>States have full ownership and exclusive legislative and executive powers to their river waters under Articles 246(3) and 162 of the Indian Constitution.</ref>. When the Punjabi suba was created, the central government made a special provision applicable only to the newly constituted states (Punjab & Haryana), depriving them of control of their river-water resources. Sections 78 to 80 in the Punjab Reorganisation Act, 1966, stipulated that the central government “assumed the powers of control, maintenance, distribution and development of the waters and the hydel power of the Punjab rivers.”<ref>Singh, Gurdev, “Punjab River Waters”, Chandigarh: Institute of Sikh Studies, 2002. http://www.sikhcoalition.org/Sikhism24.asp (last accessed, May 12, 2004).</ref>. It has been alleged that as much as seventy-five percent of Punjab’s river water was being diverted to Haryana and the non-riparian ]. Failure of the Judiciary to resolve the water dispute in Punjab led the Sikhs to believe that they were being targeted because of their religion. | |||

| Parmar and Chohan met in 1970 and formally announced the Khalistan movement at a London press conference, though being largely dismissed by the community as fanatical fringe without any support.{{sfnp|Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies|2005|p=135}} | |||

| In a judicial decision concerning the question of whether the Narmada river - which passes through the territory of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Gujarat states, but not through Rajasthan — could be shared by Rajasthan, it was ruled that: “(i) Rajasthan being a non-riparian state in regard to Narmada, cannot apply to the Tribunal, because under the Act only a co-riparian state can do so; and (ii) the state of Rajasthan is not entitled to any portion of the waters of Narmada basin on the ground that the state of Rajasthan is not a co-riparian state, or that no portion of its territory is situated in the basin of River Narmada.” See Government of India, The Report of the Narmada Water Disputes Tribunal, vol. III, New Delhi, 1978, p. 30. </ref> | |||

| ==== Chohan in Pakistan and US ==== | |||

| '''Helplessness of the judiciary in water disputes:''' The following anecdote describes the helplessness of the judiciary in India when it came to such disputes. According to the Institute of Sikh Studies, Chandigarh: | |||

| ] in ], that was proposed as the capital of Khalistan by ZA Bhutto.]] | |||

| Following the ], Chohan visited ] as a guest of such leaders as ]. Visiting ] and several historical gurdwaras in Pakistan, Chohan utilized the opportunity to spread the notion of an independent Sikh state. Widely publicized by Pakistani press, the extensive coverage of his remarks introduced the international community, including those in India, to the demand of Khalistan for the first time. Though lacking public support, the term ''Khalistan'' became more and more recognizable.{{sfnp|Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies|2005|p=135}} According to Chohan, during a talk with Prime Minister ] of Pakistan, Bhutto had proposed to make Nankana Sahib the capital of Khalistan.<ref name="ChohanIT">{{cite news|last1=Gupta|first1=Shekhar|last2=Subramanian|first2=Nirupaman|date=15 December 1993|title=You can't get Khalistan through military movement: Jagat Singh Chouhan|language=en|work=India Today|url=https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/interview/story/19931215-you-cant-get-khalistan-through-military-movement-says-jagat-singh-chouhan-811922-1993-12-15|access-date=29 November 2019|archive-date=4 February 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210204070745/https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/interview/story/19931215-you-cant-get-khalistan-through-military-movement-says-jagat-singh-chouhan-811922-1993-12-15|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| On 13 October 1971, visiting the United States at the invitation of his supporters in the ], Chohan placed an advertisement in the '']'' proclaiming an independent Sikh state. Such promotion enabled him to collect millions of dollars from the diaspora,<ref name="NYT_Chohan_Dies" /> eventually leading to charges in India relating to ] and other crimes in connection with his separatist activities. | |||

| <blockquote>"An organisation of farmers had filed a petition in the High Court, Punjab and Haryana, regarding the unconstitutionality of the drain of the waters of the Punjab to the non-riparian states under the Reorganisation Act. The issue being of fundamental constitutional importance, the Chief Justice, S.S. Sandhawalia admitted the long pending petition and announced the constitution of a Full Bench, with himself as Chairman, for the hearing of the case on the following Monday, the 25th November, 1983. In the intervening two days before the hearing of the case could start, and these two days were holidays, two things happened. First, before Monday, the Chief Justice of the High Court was transferred to the High Court of Patna. Hence neither the Bench could sit, nor could the hearing of the case start. Second an oral application was given by the Attorney General in the Supreme Court requesting for the transfer of the writ petition from the file of the High Court to that of the Supreme Court on the ground that the issue involved was of great public importance. The request was granted; the case was transferred. And there this case of great public importance rests unheard for the last nearly twenty years."<ref>Singh, Gurdev, “Punjab River Waters”, Chandigarh: Institute of Sikh Studies, 2002. http://www.sikhcoalition.org/Sikhism24.asp (last accessed, May 12, 2004).</ref></blockquote> | |||

| === |

==== Council of Khalistan ==== | ||

| After returning to India in 1977, Chohan travelled to Britain in 1979. There, he would establish the ],<ref>{{cite news |first=Jo |last=Thomas |title=London Sikh Assumes Role of Exile Chief |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1984/06/14/world/london-sikh-assumes-role-of-exile-chief.html |work=The New York Times |date=14 June 1984 |language=en |access-date=24 October 2018 |archive-date=24 October 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181024074249/https://www.nytimes.com/1984/06/14/world/london-sikh-assumes-role-of-exile-chief.html |url-status=live }}</ref> declaring its formation at ] on 12 April 1980. Chohan designated himself as President of the Council and Balbir Singh Sandhu as its Secretary General. | |||

| The Akali Dal led a series of peaceful mass demonstrations to present its grievances to the central government. The demands of the Akali Dal were based on the Anandpur Sahib Resolution <ref></ref>, which was adopted by the party in October 1973 to raise specific political, economic and social issues. The major motivation behind the resolution was the safeguarding of the Sikh identity by securing a state structure that was decentralised, with non-interference from the central government. The Resolution outlines seven objectives. <ref>Deol, Harnik, Religion and Nationalism in India: The Case of the Punjab, London: Routledge, 2000, p. 101-102.</ref> | |||

| In May 1980, Chohan travelled to ] to announce the formation of Khalistan. A similar announcement was made in ] by Sandhu, who released stamps and currency of Khalistan. Operating from a building termed "Khalistan House", Chohan named a Cabinet and declared himself president of the "Republic of Khalistan," issuing symbolic Khalistan 'passports,' 'postage stamps,' and 'Khalistan dollars.' Moreover, embassies in Britain and other European countries were opened by Chohan.<ref name="NYT_Chohan_Dies" /> It is reported that, with the support of a wealthy Californian peach magnate, Chohan opened an Ecuadorian bank account to further support his operation.<ref name=":2" /> As well as maintaining contacts among various groups in Canada, the US, and Germany, Chohan kept in contact with the Sikh leader ] who was campaigning for a ] Sikh homeland.<ref name="NYT_Chohan_Dies"/> | |||

| #The transfer of the federally administered city of Chandigarh to Punjab. | |||

| #The transfer of Punjabi speaking and contiguous areas to Punjab. | |||

| #Decentralisation of states under the existing constitution, limiting the central government’s role. | |||

| #The call for land reforms and industrialisation of Punjab, along with safeguarding the rights of the weaker sections of the population. | |||

| #The enactment of an all-India gurdwara (Sikh house of worship) act. | |||

| #Protection for minorities residing outside Punjab, but within India. | |||

| #Revision of government’s recruitment quota restricting the number of Sikhs in armed forces. | |||

| The globalized Sikh diaspora invested efforts and resources for Khalistan, but the Khalistan movement remained nearly invisible on the global political scene until the Operation Blue Star of June 1984.{{sfnp|Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies|2005|p=135}} | |||

| Along with these demands, the issue concerning the unconstitutional diversion of Punjab’s river waters to non-riparian states has been of fundamental importance. Writing about the nature of these demands, ] noted: | |||

| ====Operation Blue Star and impact==== | |||

| <blockquote>"The Akali Dal is in the hands of moderate and sensible leadership...but giving anyone a fair share of power is unthinkable politics of Mrs. Gandhi ...Many Hindus in Punjab privately concede that there isn't much wrong with these demands. But every time the ball goes to the Congress court, it is kicked out one way or another because Mrs. Gandhi considers it a good electoral calculation."<ref>The Wall Street Journal, ], ].</ref></blockquote> | |||

| In later disclosures from former special secretary G.B.S. Sidhu of the ] (R&AW), the foreign-intelligence agency of India, R&AW itself helped "build the Khalistan legend," actively participating in the planning of ]. While posted in ], Canada in 1976 to look into the "Khalistan problem" among the Sikh diaspora, Sidhu found "nothing amiss" during the three years he was there,<ref name=dulat>{{cite news |last1=Dulat |first1=A. S. |author-link=A. S. Dulat |title=Genesis of tumultuous period in Punjab |url=https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/reviews/story/genesis-of-tumultuous-period-in-punjab-183639 |website=] |location=Chandigarh, India |access-date=13 June 2021 |date=13 December 2020 |quote=Bhindranwale never raised the demand for Khalistan or went beyond the Akali Anandpur Sahib Resolution, while he himself was prepared for negotiations to the very end. |archive-date=24 June 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210624195655/https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/reviews/story/genesis-of-tumultuous-period-in-punjab-183639 |url-status=live }}</ref> stating that "Delhi was unnecessarily making a mountain of a molehill where none existed," that the agency created seven posts in West Europe and North America in 1981 to counter non-existent Khalistan activities, and that the deployed officers were "not always familiar with the Sikhs or the Punjab issue."<ref name=dulat/> He described the secessionist movement as a "chimera" until the army operation, after which the insurgency would start.<ref name=dulat/> | |||

| According to a ''New York Times'' article written just a few weeks after the operation, "Before the raid on the Golden Temple, neither the Government nor anyone else appeared to put much credence in the Khalistan movement. Mr. Bhindranwale himself said many times that he was not seeking an independent country for Sikhs, merely greater autonomy for Punjab within the Indian Union.... One possible explanation advanced for the Government's raising of the Khalistan question is that it needs to take every opportunity to justify the killing in Amritsar and the invasion of the Sikhs' holiest shrine."<ref name=stevens>{{cite news |last1=Stevens |first1=William K. |title=Punjab Raid: Unanswered Questions |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1984/06/19/world/punjab-raid-unanswered-questions.html |access-date=12 June 2021 |work=The News York Times |date=19 June 1984 |archive-date=24 June 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210624205941/https://www.nytimes.com/1984/06/19/world/punjab-raid-unanswered-questions.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===The assassination of Lala Jagat Narain=== | |||

| Khushwant Singh had written that "considerable Khalistan sentiment seems to have arisen since the raid on the temple, which many Sikhs, if not most, have taken as a deep offense to their religion and their sensibilities," referring to the drastic change in community sentiments after the army attack.<ref name=stevens/> | |||

| In a politically charged environment, ''']''', the owner of the Hind Samachar group of newspapers, was assassinated by Sikh militants in September 1981. He had been instrumental in persuading Punjabi Hindus to declare their mother tongue as Hindi. His editorials consistently attacked the Akali Dal’s leadership. His assassination led to mob violence by Hindus, who set Sikhs' shops on fire and burnt the offices of the Akali Patrika, a Punjabi newspaper that represented Sikh interests. In September 1981, Bhindranwale was arrested for his alleged role in the assassination. He was detained and interrogated for twenty-five days, but was released because of lack of evidence. After his release, Bhindranwale relocated himself from his headquarters at Mehta Chowk to Guru Nanak Niwas within the Harmindar Sahib precincts.<ref>Ibid, p. 105.</ref> Many Sikhs today criticise this move because they believe that it gave the state an excuse to attack the temple. | |||

| == Late 1970s to 1983 == | |||

| ===Dharam Yudh Morcha=== | |||

| In August 1982, the Akali Dal under the leadership of Harcharan Singh Longowal launched the Dharam Yudh Morcha, or the “battle for righteousness.” Bhindranwale and the Akali Dal united for the first time; their goal was the fulfillment of demands based upon the Anandpur Sahib Resolution. In two and a half months, security forces arrested thirty thousand Sikhs for their peaceful demonstrations to the point that protesting volunteers could not be accommodated in the existing jails.<ref>Deol, Harnik, Religion and Nationalism in India: The Case of the Punjab, London: Routledge, 2000, p. 105.</ref> | |||

| {{main|Dharam Yudh Morcha}} | |||

| In November 1982, Akali Dal announced the organisation of peaceful protests in ] during the ]. To prevent Sikhs from reaching Delhi, the police were instructed to stop all buses, trains and vehicles that were headed for Delhi and interrogate Sikh passengers. The Sikhs as a community felt discriminated against by the Indian state. Later, the Akali Dal organised a convention at the Darbar Sahib attended by 5,000 Sikh ex-servicemen, 170 of whom were above the rank of colonel. These Sikhs claimed that there was discrimination against them in government service.<ref>Deol, Harnik, Religion and Nationalism in India: The Case of the Punjab, London: Routledge, 2000, p. 105.</ref> | |||

| === |

===Delhi Asian Games (1982)=== | ||

| During this turmoil, the Akali Dal began another agitation in February 1984 protesting against clause (2)(b) of Article 25 of the Indian constitution, which defines Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains as being Hindu. Several Akali leaders were arrested for burning the Indian constitution in protest. <ref>Deol, Harnik, Religion and Nationalism in India: The Case of the Punjab, London: Routledge, 2000, p. 106.</ref> | |||

| The Akali leaders, having planned to announce a victory for Dharam Yudh Morcha, were outraged by the changes to the agreed-upon settlement. In November 1982, Akali leader ] announced that the party would disrupt the ] by sending groups of Akali workers to Delhi to intentionally get arrested. Following negotiations between the Akali Dal and the government failed at the last moment due to disagreements regarding the transfer of areas between Punjab and Haryana.<ref name="JSChima">{{citation|last1=Chima|first1=Jugdep S|title=The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements|date=2008|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qJaHAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA72|pages=71–75|place=India|publisher=Sage Publications|isbn=978-81-321-0538-1|access-date=5 October 2020|archive-date=30 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072133/https://books.google.com/books?id=qJaHAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA72|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| From the point of view of religious affirmation, India’s defining of its Sikh, ] and ] citizens as being part of the Hindu community provides provided cause for discontent. For instance, a Sikh couple who marry in accordance to the rites of the Sikh religion must register their marriage either under the Special Marriages Act (1954) or the Hindu Marriage Act (1955)<ref>See (last accessed May 12, 2004)</ref>, there being no separate marriage act dealing with Sikh marriages.<ref>In the colonial period, Sikh marriages were registered under the Anand Marriage Act of 1909, which was named after the Sikh marriage ceremony, the ''Anand Karaj''. The Anand Marriage Act was repealed in independent India.</ref> Although the legal registration of weddings is not required, under Indian law, to establish in court that a marriage existed, this circumstance was viewed by some as being a coercive in often obtaining a tacit declaration from the couple to the effect that they were Hindu. According to one stream of opinion, the contents of clause (2)(b) of Article 25 of the Indian constitution and the laws based on its interpretation are arguably in violation of Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) calling for free exercise of religion, because Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains have no way of asserting their religious identity in certain situations: they must choose between affirming themselves Hindu or making no statement at all on religion . | |||

| Knowing that the Games would receive extensive coverage, Akali leaders vowed to overwhelm Delhi with a flood of protestors, aiming to heighten the perception of Sikh "plight" among the international audience.<ref name="JSChima" /> A week before the Games, ], Chief Minister of Haryana and member of the ] party, responded by sealing the Delhi-Punjab border,<ref name="JSChima" /> and ordering all Sikh visitors travelling from to Delhi from Punjab to be frisked.<ref>{{cite news|last=Sharma|first=Sanjay|date=5 June 2011|title=Bhajan Lal lived with 'anti-Sikh, anti-Punjab' image|url=https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Bhajan-Lal-lived-with-anti-Sikh-anti-Punjab-image/articleshow/8731824.cms|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110610094016/http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-06-05/india/29622770_1_bhajan-lal-syl-punjab|url-status=live|work=]|archive-date=10 June 2011}}</ref> While such measures were seen as discriminatory and humiliating by Sikhs, they proved effective as Akali Dal could only organize small and scattered protests in Delhi. Consequently, many Sikhs who did not initially support Akalis and Bhindranwale began sympathizing with the Akali Morcha.<ref name="JSChima" /> | |||

| ===Operation Bluestar=== | |||

| ''']''', was aimed at flushing out militants from the holiest Sikh shrine - The Golden Temple. To flush the terrorists and their masterminds out of the Golden Temple complex, the army launched what is possibly its most controversial action, Operation Bluestar, under the command of Major General Kuldip Singh Brar (a Sikh himself ) , who later retired as lieutenant general. The army had been ordered to destroy the movement to create Khalistan and to cleanse the Golden Temple of all the militants hiding there, including the leader of the militants, Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. | |||

| Following the conclusion of the Games, Longowal organised a convention of Sikh veterans at the ]. It was attended by a large number of Sikh ex-servicemen, including {{Abbr|retd.|retired}} ] ] who subsequently became Bhindranwale's military advisor.<ref name="JSChima" /> | |||

| Lieutenant General Kuldip Singh Brar ,then Major General who commanded Indian Army soldiers to enter the Golden Temple, says : | |||

| == 1984 == | |||

| <blockquote>"Apparently, the government had no other recourse. The events in Punjab had reached a complete breakdown. | |||

| The Sikh militants were in total control of the state machinery. There was a strong feeling that Khalistan was going to be established at any time. Bhindranwale was being seen as a prophet; he was making very strong speeches against (the then Prime Minister of India) Indira Gandhi and non-Sikhs; and trying to send a message across to the rural areas that the Sikhs are being given second-grade treatment and that it is high time we formed our own independent state of Khalistan. There was a strong possibility of Pakistan helping them and I think there was the possibility of a Bangladesh being repeated."</blockquote> | |||

| ===Increasing militant activity=== | |||

| <blockquote>" I can't comment on the inside of politics, but I assume that after taking everything into consideration, the prime minister and the government decided this was the only course of action left if we were to keep this country together, to prevent its fragmentation, to prevent Khalistan. And having seen reports of about 2,000 militants inside (Amritsar's Golden Temple) with any number of machine guns, different types of weapons, it was clearly beyond the capabilities of the police force to flush out the militants from the Golden Temple; the task had to be entrusted to the Army."</blockquote> | |||

| Widespread murders by followers of Bhindranwale occurred in 1980s' Punjab. Armed Khalistani militants of this period described themselves as ''].''<ref name="Kharku">{{citation|last1=Stepan|first1=Alfred|first2=Juan J.|last2=Linz|first3=Yogendra|last3=Yadav|title=Crafting State-Nations: India and Other Multinational Democracies|date=2011|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kGUuOdeCiXQC&q=Kharku&pg=PA97|page=97|edition=Illustrated|publisher=JHU Press|isbn=978-0-8018-9723-8|access-date=5 October 2020|archive-date=30 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072140/https://books.google.com/books?id=kGUuOdeCiXQC&q=Kharku&pg=PA97|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| On its own, the year 1984 (from 1 January to 3 June) saw 775 violent incidents, resulting in 298 people killed and 525 injured.<ref name="Ghosh">Ghosh, Srikanta. 1997. ''Indian Democracy Derailed – Politics and Politicians.'' APH Publishing. {{ISBN|978-81-7024-866-8}}. p. 95.</ref> | |||

| He also alleges that Pakistan would have recognized Khalistan if Khalistan was declared. | |||

| Though it was common knowledge that those responsible for such bombings and murders were taking shelter in ]s, the ] ] declared that it could not enter these places of worship, for the fear of hurting Sikh sentiments.<ref name="Akshay1991" /> Even as detailed reports on the open shipping of arms-laden trucks were sent to ] ], the Government choose not to take action.<ref name="Akshay1991" /> Finally, following the murder of six Hindu bus passengers in October 1983, emergency rule was imposed in Punjab, which would continue for more than a decade.<ref name="GusMartin2011">Sisson, Mary. 2011. "Sikh Terrorism." pp. 544–545 in ''The Sage Encyclopedia of Terrorism'' (2nd ed.), edited by G. Martin. Thousand Oaks, CA: ]. {{ISBN|978-1-4129-8016-6}}. {{doi|10.4135/9781412980173.n368}}.</ref> | |||

| ===Criticism of the attack=== | |||

| === Constitutional issues === | |||

| For over a year, the Indian army had been preparing for an attack on the Darbar Sahib. According to ], a member of the Indian Parliament, the central government had launched a disinformation campaign in order to legitimise the attack. In his words, the state sought to “make out that the Golden Temple was the haven of criminals, a store of armory and a citadel of the nation’s dismemberment conspiracy.”<ref>Swami, Subramaniam, Imprint, July 1984, p. 7-8. Quoted in Kumar, Ram Narayan, et al, Reduced to Ashes: The Insurgency and Human Rights in Punjab, Kathmandu: South Asia Forum for Human Rights, 2003, p. 34. (Hereafter, Reduced to Ashes.)</ref> | |||

| The Akali Dal began more agitation in February 1984, protesting against Article 25, clause (2)(b), of the ], which ambiguously explains that "the reference to Hindus shall be construed as including a reference to persons professing the Sikh, ], or ] religion," while also implicitly recognizing Sikhism as a separate religion: "the wearing and carrying of ] ]''] shall be deemed to be included in the profession of the Sikh religion."<ref name=":3">Sharma, Mool Chand, and A.K. Sharma, eds. 2004. " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201024145050/https://nhrc.nic.in/sites/default/files/discriminationsexcastereligion.pdf#page=122 |date=24 October 2020 }}." pp. 108–110 in ''Discrimination Based on Sex, Caste, Religion, and Disability''. New Delhi: ]. from the original on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2020.</ref>{{Rp|109}} Even today, this clause is deemed offensive by many religious minorities in India due to its failure to recognise such religions separately under the constitution.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

| Members of the Akali Dal demanded that the removal of any ambiguity in the Constitution that refers to Sikhs as Hindu, as such prompts various concerns for the Sikh population, both in principle and in practice. For instance, a Sikh couple who would marry in accordance to the ] would have to register their union either under the '']'' or the '']''. The Akalis demanded replacement of such rules with laws specific to ]. | |||

| ===The assassination of Indira Gandhi and subsequent rioting=== | |||

| On the morning of ], ], Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was shot dead by two Sikh security guards in ]. The assassination triggered organised violence against Sikhs in the National Capital Delhi and some other parts of the country. Eminent writers allege that Politicians belonging to the ruling Congress party met to decide how to teach the Sikhs a lesson they would never forget. Hordes of people from the suburbs of Delhi were transported to various localities in the city where the Sikh population was concentrated. The mobilisation suggested (the) backing of an organisation with vast resources. The mob carried crude weapons and combustible material, including kerosene, for arson. They were allegedly supplied with lists of houses and business establishments belonging to the Sikhs in various localities. It was also alleged that State-operated national television was used by the state to incite violence against the Sikhs. In all, 2146 sikhs lost their lives in Delhi, while another 586 were said to have been killed elsewhere in the country <ref>Report of Justice Nanawati Commission of Enquiry</ref>. | |||

| === |

=== Operation Blue Star === | ||

| Two major civil-liberties organisations issued a joint report on the anti-Sikh riots naming sixteen important politicians, thirteen police officers and one hundred and ninety-eight others, accused by survivors and eye-witnesses.<ref>Kumar, Ram Narayan, et. al., Reduced to Ashes, p. 43.</ref> In January 1985, journalist Rahul Bedi of the ] and Smitu Kothari of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties “moved the High Court of Delhi to demand a judicial inquiry into the riots on the strength of the documentation carried out by human rights organisations. Justice Yogeshwar Dayal dismissed the petition after deprecating 'those busybodies out for publicity, who poke their noses into all matters and waste the valuable time of the judiciary.'”<ref>Kumar, Ram Narayan, et. al., Reduced to Ashes, p. 43-4.</ref> | |||

| ] was an Indian military operation ordered by ] ], between 1 and 8 June 1984, to remove militant religious leader ] and his armed followers from the buildings of the ] complex (aka the Golden Temple) in ], ]{{snd}}the most sacred site in Sikhism.<ref name="TH_Mi6">{{cite news |title=RAW chief consulted MI6 in build-up to Operation Bluestar |url=http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/raw-chief-consulted-mi6-in-buildup-to-operation-bluestar/article5579516.ece |newspaper=] |date=16 January 2014 |location=Chennai, India |first=Praveen |last=Swami |access-date=9 August 2018 |archive-date=18 January 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140118044721/http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/raw-chief-consulted-mi6-in-buildup-to-operation-bluestar/article5579516.ece |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ====Denial of justice==== | |||

| A number of politicians who organised the violence allegedly retained or attained positions of importance in the Congress party and even in the central government. The role of Delhi police also came into question with allegations of not just negligence in protecting the Sikhs but also of conniving in and instigating the riots. The Misra Commission was appointed to investigate the killings. According to Patwant Singh: | |||

| In July 1983, ] President ] had invited Bhindranwale to take up residence at the sacred temple complex,<ref>Singh, Khushwant. 2004. ''A History of the Sikhs, Volume II: 1839–2004''. New Delhi: ]. p. 337.</ref> which the government would allege that Bhindranwale would later make into an ] and headquarters for his armed uprising.<ref>{{Cite journal |last = Subramanian |first = L. N. |date = 2006-10-12 |title=Operation Bluestar, 05 June 1984 |journal = Bharat Rakshak Monitor |volume = 3 |issue = 2 |url = http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/ARMY/history/siachen/283-Operation-Bluestar.html |access-date = 2020-05-17 |archive-date = 2020-06-30 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20200630015541/http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/ARMY/history/siachen/283-Operation-Bluestar.html |url-status = live}}</ref><ref name="LA_accord">{{cite news|date=21 August 1985|title=Sikh Leader in Punjab Accord Assassinated|newspaper=Los Angeles Times|agency=Times Wire Services|url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1985-08-21-mn-1021-story.html|access-date=9 August 2018|archive-date=29 January 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160129025949/http://articles.latimes.com/1985-08-21/news/mn-1021_1_sikh-militants|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>The Government received the Misra Commission’s report…and took six months to place it before parliament...(this finally happened) a full 27 months after the killings. A weak and vapid report, it let key Congress figures off the hook and characteristically recommended the setting up of three more committees…The third committee spawned two more committees plus an enquiry by the Central bureau of Investigation (CBI). When one of these two, the Poti-Rosha Committee, recommended 30 cases for prosecution, including one against Sajjan Kumar, Congress MP , and the CBI sent a team to arrest him on 11 September 1990, a mob held the team captive for more than four hours! According to the CBI’s subsequent affidavit filed in court, “the Delhi Police, far from trying to disperse the mob, sought an assurance from the CBI that he (Sajjan Kumar) would not be arrested.” The CBI also “disclosed that file relating to the case was found in Sajjan Kumar’s house.” The MP was given “anticipatory bail while the CBI team was being held captive” by his henchmen.</blockquote> | |||

| Since the inception of the Dharam Yudh Morcha to the violent events leading up to Operation Blue Star, Khalistani militants had directly killed 165 ] and ]s, as well as 39 Sikhs opposed to Bhindranwale, while a total of 410 were killed and 1,180 injured as a result of Khalistani violence and riots.<ref name="ms_casualty_terror">{{Cite book |last1 = Tully |first1 = Mark |author-link1 = Mark Tully |last2 = Jacob |first2 = Satish |date = 1985 |title = Amritsar: Mrs Gandhi's Last Battle |publisher = J. Cape |edition = 5 |page = 147 |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=bxhuAAAAMAAJ&q=editions:drN_lbMXXJMC|language=en|access-date=14 January 2023|archive-date=30 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330072209/https://books.google.com/books?id=bxhuAAAAMAAJ&q=editions:drN_lbMXXJMC|url-status=live |isbn = 978-0-22-402328-3}}</ref> | |||

| Patwant Singh continues, | |||

| As negotiations held with Bhindranwale and his supporters proved unsuccessful, Indira Gandhi ordered the ] to launch Operation Blue Star.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia | |||