| Revision as of 20:46, 29 January 2015 view sourceXxX GeT-ReKt XxX (talk | contribs)2 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 13:05, 23 December 2024 view source Ozzie10aaaa (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers213,670 edits needs source | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Specific learning disability characterized by troubles with reading}} | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| {{cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}} | |||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | {{pp-move-indef}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January |

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2021}} | ||

| {{Infobox |

{{Infobox medical condition (new) | ||

| | |

| name = Dyslexia | ||

| | synonyms = Reading disorder | |||

| |DiseasesDB = 4016 | |||

| | image = File:Dislexia nens.jpg | |||

| |ICD10 = {{ICD10|R|48|0|r|47}} | |||

| | image_size = | |||

| |ICD9 = {{ICD9|315.02}} | |||

| | caption = Difficulties in processing letters and words | |||

| |ICDO = | |||

| | types = ] | |||

| |OMIM = 127700 | |||

| | field = ], ] | |||

| |MedlinePlus = 001406 | |||

| | symptoms = Trouble ]<ref name="ninds1"/> | |||

| |eMedicineSubj = | |||

| | complications = | |||

| |eMedicineTopic = D009983 | |||

| | onset = School age<ref name=Lancet2012/> | |||

| |MeshID = D004410}} | |||

| | duration = | |||

| ] | |||

| | causes = ] and environmental factors<ref name=Lancet2012 /> | |||

| | risks = Family history, ]<ref name=NIH2014Def/> | |||

| | diagnosis = Series memory, spelling, vision, and reading test<ref name=NIH2015Diag/> | |||

| | differential = ] or ]s, insufficient ]<ref name=Lancet2012/> | |||

| | prevention = | |||

| | treatment = Adjusting teaching methods<ref name=ninds1/> | |||

| | medication = | |||

| | prognosis = | |||

| | frequency = 3–7%<ref name=Lancet2012/><ref name=Koo2013/> | |||

| | deaths = | |||

| }} | |||

| <!-- Definition and symptoms --> | |||

| '''Dyslexia''', previously known as '''word blindness''', is a ] that affects either reading or writing.<ref name=ninds1>{{cite web |url=https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Dyslexia-Information-Page |title=Dyslexia Information Page |date=2 November 2018 |publisher=] }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Siegel LS | title = Perspectives on dyslexia | journal = Paediatrics & Child Health | volume = 11 | issue = 9 | pages = 581–7 | date = November 2006 | pmid = 19030329 | pmc = 2528651 | doi = 10.1093/pch/11.9.581 | issn=1205-7088 }}</ref> Different people are affected to different degrees.<ref name=NIH2014Def/> Problems may include difficulties in ] words, reading quickly, ], "sounding out" words ], pronouncing words when reading aloud and understanding what one reads.<ref name=NIH2014Def/><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/reading/conditioninfo/symptoms |title=What are the symptoms of reading disorders? |publisher=National Institutes of Health |date=1 December 2016 }}</ref> Often these difficulties are first noticed at school.<ref name=Lancet2012>{{cite journal|last1=Peterson|first1=Robin L.|last2=Pennington|first2=Bruce F.|title=Developmental dyslexia|journal=Lancet|volume=379|issue=9830|pages=1997–2007|date=May 2012|pmid=22513218|pmc=3465717 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60198-6}}</ref> The difficulties are involuntary, and people with this disorder have a normal desire to ].<ref name=NIH2014Def>{{cite web |url=https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/reading/conditioninfo/disorders |title=What are reading disorders? |publisher=National Institutes of Health |date=1 December 2016 }}</ref> People with dyslexia have higher rates of ] (ADHD), ]s, and ].<ref name=Lancet2012/><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Sexton|first1=Chris C.|last2=Gelhorn|first2=Heather L.|last3=Bell|first3=Jill A.|last4=Classi|first4=Peter M.|date=November 2012|title=The Co-occurrence of Reading Disorder and ADHD: Epidemiology, Treatment, Psychosocial Impact, and Economic Burden|journal=Journal of Learning Disabilities|volume=45|issue=6|pages=538–564|doi=10.1177/0022219411407772|pmid=21757683|s2cid=385238}}</ref> | |||

| <!-- Cause, mechanism, and diagnosis --> | |||

| '''Dyslexia''', aka, Potato syndrome.'<ref>{{cite book|last1=Benson|first1=David|title=Aphasia: A Clinical Perspective|date=1996|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780195089349|page=180|url=https://books.google.ca/books?id=iZ8PfkgGiOUC&pg=PA180}}</ref> or '''developmental reading disorder''',<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0002379/ | title=Developmental reading disorder | publisher=A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. | year=2013 | accessdate=23 January 2014}}</ref> is characterized by difficulty with learning to read and with differing comprehension of language despite normal or above-average intelligence.<ref>{{cite book |first1=Linda Kreger |last1=Silverman |chapter=The Two-Edged Sword of Compensation: How the Gifted Cope with Learning Disabilities |pages=153–9 |editor1-first=Kiesa |editor1-last=Kay |year=2000 |title=Uniquely Gifted: Identifying and Meeting the Needs of the Twice-exceptional Student |publisher=Avocus |isbn=978-1-890765-04-0}}</ref><ref name="ninds1">{{cite web |url=http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/dyslexia/dyslexia.htm |title=Dyslexia Information Page |publisher=National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke |date=12 May 2010 |accessdate=5 July 2010}}</ref> This includes difficulty with ], ] decoding, processing speed, ], ], language skills and verbal comprehension, or ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Grigorenko |first1=E. L. |year=2001 |title=Developmental Dyslexia: An Update on Genes, Brains, and Environments |journal=Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry |volume=42 |issue=1 |pages=91–125 |pmid=11205626 |doi=10.1111/1469-7610.00704}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Schulte-Körne |first1=Gerd |last2=Warnke |first2=Andreas |last3=Remschmidt |first3=Helmut |date=November 2006 |title=Zur Genetik der Lese-Rechtschreibschwäche |trans_title=Genetics of dyslexia |language=German |journal=Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie |volume=34 |issue=6 |pages=435–44 |pmid=17094062 |doi=10.1024/1422-4917.34.6.435}}</ref> | |||

| Dyslexia is believed to be caused by the ] of ] and environmental factors.<ref name="Lancet2012" /> Some cases run in families.<ref name="NIH2014Def" /><!-- quote = Dyslexia can be inherited in some families --> Dyslexia that develops due to a ], ], or ] is sometimes called "acquired dyslexia"<ref name="ninds1" /> or '''alexia'''.<ref name=NIH2014Def/> The underlying mechanisms of dyslexia result from differences within ].<ref name="NIH2014Def" /> Dyslexia is diagnosed through a series of tests of memory, vision, spelling, and reading skills.<ref name="NIH2015Diag">{{cite web|url=http://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/reading/conditioninfo/pages/diagnosed.aspx|title=How are reading disorders diagnosed?|publisher=National Institutes of Health|access-date=15 March 2015|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150402093505/http://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/reading/conditioninfo/pages/diagnosed.aspx|archive-date=2 April 2015}}</ref> Dyslexia is separate from reading difficulties caused by ] or ]s or by insufficient ] or opportunity to learn.<ref name="Lancet2012" /> | |||

| <!-- Treatment and epidemiology --> | |||

| Dyslexia is the most common ].<ref>{{cite journal | title=Learning disabilities, dyslexia, and vision | journal=Pediatrics|date=March 2011 | volume=127 | issue=3 | pages=e818–56 | doi=10.1542/peds.2010-3670 | pmid=21357342| author1=Handler| first1=S. M.| last2=Fierson| first2=W. M.| last3=Section On| first3=Ophthalmology| author4=Council on Children with Disabilities| last5=American Academy Of| first5=Ophthalmology| author6=American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology Strabismus| author7=American Association of Certified Orthoptists}}</ref> Some see dyslexia as distinct from reading difficulties resulting from other causes, such as a non-neurological deficiency with hearing or vision, or poor ].<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Explaining the differences between the dyslexic and the garden-variety poor reader: the phonological-core variable-difference model |journal=Journal of Learning Disabilities |volume=21 |issue=10 |pages=590–604 |date=December 1988 |pmid=2465364 |doi=10.1177/002221948802101003|author1=Stanovich |first1=K. E.}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |title=Reading and spelling disorders: Clinical features and causes |journal=Journal European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry |date=19 September 1999 |first=Andreas |last=Warnke |volume=8 |issue=3 |pages=S2–S12 |doi=10.1007/PL00010689}}</ref> There are three proposed cognitive subtypes of dyslexia (auditory, visual and attentional), although individual cases of dyslexia are better explained by specific underlying neuropsychological deficits (e.g., ], a visual processing disorder) and co-occurring learning difficulties (e.g., ] and ]).<ref name=anchoring>{{Cite journal |title=Dyslexia and the anchoring-deficit hypothesis |journal=Trends in Cognitive Sciences |volume=11 |issue=11 |pages=458–65 |date=November 2007 |pmid=17983834 |doi=10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.015 |last1=Ahissar |first1=Merav}}</ref><ref name="Chung KK">{{Cite journal |title=Cognitive profiles of Chinese adolescents with dyslexia |journal=Dyslexia |volume=16 |issue=1 |pages=2–23 |date=February 2010 |pmid=19544588 |doi=10.1002/dys.392|author1=Chung |first1=K. K. |last2=Ho |first2=C. S. |last3=Chan |first3=D. W. |last4=Tsang |first4=S. M. |last5=Lee |first5=S. H.}}</ref> Although it is considered to be a receptive (afferent) language-based learning disability, dyslexia also affects one's expressive (efferent) language skills.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Learning disabilities, dyslexia, and vision |pmid=21357342 |doi=10.1542/peds.2010-3670 |volume=127 |issue=3 |date=March 2011 |journal=Pediatrics |pages=e818–56|author1=Handler |first1=S. M. |last2=Fierson |first2=W. M. |last3=Section On |first3=Ophthalmology |author4=Council on Children with Disabilities |last5=American Academy Of |first5=Ophthalmology |author6=American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology Strabismus |author7=American Association of Certified Orthoptists}}</ref> | |||

| Treatment involves adjusting teaching methods to meet the person's needs.<ref name=ninds1/> While not curing the underlying problem, it may decrease the degree or impact of symptoms.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/reading/conditioninfo/pages/treatment.aspx|title=What are common treatments for reading disorders?|publisher=National Institutes of Health|access-date=15 March 2015|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150402142536/http://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/reading/conditioninfo/pages/treatment.aspx|archive-date=2 April 2015}}</ref> Treatments targeting vision are not effective.<ref name=Handler2011>{{cite journal|last1=Handler|first1=SM|last2=Fierson|first2=WM|last3=Section on|first3=Ophthalmology|last4=Council on Children with|first4=Disabilities|last5=American Academy of|first5=Ophthalmology|last6=American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and|first6=Strabismus|last7=American Association of Certified|first7=Orthoptists|title=Learning disabilities, dyslexia, and vision.|journal=Pediatrics|date=March 2011|volume=127|issue=3|pages=e818–56|pmid=21357342|doi=10.1542/peds.2010-3670|s2cid=11454203 |doi-access=}}</ref> Dyslexia is the most common ] and occurs in all areas of the world.<ref name=UmphredLazaro2013m>{{cite book|author1=Umphred, Darcy Ann|author2=Lazaro, Rolando T.|author3=Roller, Margaret|author4=Burton, Gordon|title=Neurological Rehabilitation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lVJPAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA383|year=2013|publisher=Elsevier Health Sciences|isbn=978-0-323-26649-9|page=383|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109173020/https://books.google.com/books?id=lVJPAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA383|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref> It affects 3–7% of the population;<ref name=Lancet2012/><ref name=Koo2013>{{cite book|last1=Kooij|first1=J. J. Sandra|title=Adult ADHD diagnostic assessment and treatment|date=2013|publisher=Springer|location=London|isbn=9781447141389|page=83|edition=3rd|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JM_awX-mSPoC&pg=PA83|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160430012545/https://books.google.com/books?id=JM_awX-mSPoC&pg=PA83|archive-date=30 April 2016}}</ref> however, up to 20% of the general population may have some degree of symptoms.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/reading/conditioninfo/pages/risk.aspx|title=How many people are affected by/at risk for reading disorders?|publisher=National Institutes of Health|access-date=15 March 2015|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150402101751/http://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/reading/conditioninfo/pages/risk.aspx|archive-date=2 April 2015}}</ref> While dyslexia is more often diagnosed in boys, this is partly explained by a self-fulfilling ] among teachers and professionals.<ref name=Lancet2012/><ref>{{cite journal | url=https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12691 | doi=10.1111/jcpp.12691 | title=Explaining the sex difference in dyslexia | year=2017 | last1=Arnett | first1=Anne B. | last2=Pennington | first2=Bruce F. | last3=Peterson | first3=Robin L. | last4=Willcutt | first4=Erik G. | last5=Defries | first5=John C. | last6=Olson | first6=Richard K. | journal=Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry | volume=58 | issue=6 | pages=719–727 | pmid=28176347 | pmc=5438271 }}</ref> It has even been suggested that the condition affects men and women equally.<ref name=UmphredLazaro2013m/> Some believe that dyslexia is best considered as a different way of learning, with both benefits and downsides.<ref>{{cite magazine|url = https://www.wired.com/2011/09/dyslexic-advantage/|title = The Unappreciated Benefits of Dyslexia|date = September 2011|access-date = 10 August 2016|magazine = Wired|last = Venton|first = Danielle|url-status = live|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160805001607/http://www.wired.com/2011/09/dyslexic-advantage|archive-date = 5 August 2016|df = dmy-all}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url = http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-advantages-of-dyslexia/|title = The Advantages of Dyslexia|date = August 2014|access-date = 10 August 2016|website = ScientificAmerican.com|publisher = Scientific American|last = Mathew|first = Schneps|url-status = live|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160804232616/http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-advantages-of-dyslexia/|archive-date = 4 August 2016|df = dmy-all}}</ref> | |||

| {{TOC limit|3}} | |||

| {{TOC limit}} | |||

| ==Classification== | ==Classification== | ||

| {{Main|Pure alexia}} | |||

| Internationally, dyslexia is designated as a cognitive disorder related to reading and speech. The ] definition describes it as "difficulty with spelling, phonological processing (the manipulation of sounds), or rapid visual-verbal responding."<ref name="ninds1"/> There are many published definitions, and many of them are purely descriptive or embody causal theories, that encompass a variety of reading skills, deficits and difficulties with distinct causes rather than a single condition.<ref name=NRDC>{{cite book |first1=Michael |last1=Rice |first2=Greg |last2=Brooks |chapter=Some definitions of dyslexia |title=Developmental dyslexia in adults: a research review |date=1 May 2004 |publisher=national research and development center for adult literacy and numeracy |url=http://www.nrdc.org.uk/projects_details.asp?ProjectID=75 |pages=133–46 |accessdate=13 May 2009 |isbn=978-0-9546492-8-9}}</ref> | |||

| Dyslexia is divided into developmental and acquired forms.<ref>Oxford English Dictionary. 3rd ed. ". Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2012 ("a learning disability specifically affecting the attainment of literacy, with difficulty esp. in word recognition, spelling, and the conversion of letters to sounds, occurring in a child with otherwise normal development, and now usually regarded as a neurodevelopmental disorder with a genetic component.")</ref> Acquired dyslexia occurs subsequent to neurological insult, such as ] or ]. People with acquired dyslexia exhibit some of the signs or symptoms of the developmental disorder, but require different assessment strategies and treatment approaches.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Woollams|first=Anna M.|date=19 January 2014|title=Connectionist neuropsychology: uncovering ultimate causes of acquired dyslexia|journal=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences|language=en|volume=369|issue=1634|pages=20120398|doi=10.1098/rstb.2012.0398|issn=0962-8436|pmc=3866427|pmid=24324241}}</ref> ''Pure alexia'', also known as ''agnosic alexia'' or ''pure word blindness'', is one form of ] which makes up "the peripheral dyslexia" group.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Coslett HB |title=Acquired dyslexia |journal=Semin Neurol |volume=20 |issue=4 |pages=419–26 |year=2000 |pmid=11149697 |doi=10.1055/s-2000-13174 |s2cid=36969285 }}</ref> | |||

| Acquired dyslexia, ], can be caused by brain damage, ], and ]. Forms of alexia include: ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Harley |first=Trevor A. |title=The psychology of language: from data to theory |publisher=Taylor & Francis |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-86377-867-4}}{{page needed|date=January 2015}}</ref><ref name="Acquired dyslexia">{{cite journal |last1=Coslett |first1=H. Branch |year=2000 |title=Acquired dyslexia |journal=Seminars in Neurology |volume=20 |issue=4 |pages=419–26 |pmid=11149697 |doi=10.1055/s-2000-13174}}</ref> Acquired surface dyslexia arises after brain damage in a previously literate person and results in pronunciation errors that indicate impairment of the lexical route.<ref name=coltheart1>{{cite journal |last1=Coltheart |first1=Max |last2=Curtis |first2=Brent |last3=Atkins |first3=Paul |last4=Haller |first4=Micheal |title=Models of reading aloud: Dual-route and parallel-distributed-processing approaches |journal=Psychological Review |date=1 January 1993 |volume=100 |issue=4 |pages=589–608 |doi=10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.589}}</ref><ref name=behrmann>{{cite journal |last1=Behrmann |first1=Marlene |last2=Bub |first2=D. |title=Surface dyslexia and dysgraphia: dual routes, single lexicon |journal=Cognitive Neuropsychology |year=1992 |volume=9 |issue=3 |pages=209–51 |doi=10.1080/02643299208252059}}</ref> Numerous symptom-based definitions of dyslexia suggest neurological approaches. | |||

| ==Signs and symptoms== | ==Signs and symptoms== | ||

| {{See also|Characteristics of dyslexia}} | {{See also|Characteristics of dyslexia}} | ||

| In early childhood, symptoms that correlate with a later diagnosis of dyslexia include ],<ref name='Huc-Chabrolle'>{{Cite journal |title=Les troubles psychiatriques et psychocognitifs associés à la dyslexie de développement : un enjeu clinique et scientifique |trans_title=Psychocognitive and psychiatric disorders associated with developmental dyslexia: A clinical and scientific issue |language=French |journal=L'Encéphale |volume=36 |issue=2 |pages=172–9 |date=April 2010 |id={{INIST|22769939}} |pmid=20434636 |doi=10.1016/j.encep.2009.02.005|author1=Huc-Chabrolle |first1=M |last2=Barthez |first2=M. A. |last3=Tripi |first3=G |last4=Barthélémy |first4=C |last5=Bonnet-Brilhault |first5=F}}</ref> letter reversal or mirror writing, difficulty knowing left from right and difficulty with direction,<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Mirror writing, left-handedness, and leftward scripts |journal=Arch. Neurol. |volume=61 |issue=12 |pages=1849–51 |date=December 2004 |pmid=15596604 |doi=10.1001/archneur.61.12.1849|author1=Schott |first1=G. D. |last2=Schott |first2=J. M.}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |title=Mirror writing: neurological reflections on an unusual phenomenon |journal=J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. |volume=78 |issue=1 |pages=5–13 |date=January 2007 |pmid=16963501 |pmc=2117809 |doi=10.1136/jnnp.2006.094870|author1=Schott |first1=G. D.}}</ref> as well as being easily distracted by background noise.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Selective auditory attention abilities of learning disabled and normal achieving children |journal=] |volume=16 |issue=4 |pages=202–5 |date=April 1983 |pmid=6864110 |doi= 10.1177/002221948301600405|author1=Cherry |first1=R. S. |last2=Kruger |first2=B}}</ref> This pattern of early distractibility is sometimes partially explained by the co-occurrence of dyslexia and ] (ADHD). Although this disorder occurs in approximately 5% of children, 25–40% of children with either dyslexia or ADHD meet criteria for the other disorder.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Comorbidity of reading disability and attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder: Differences by gender and subtype|journal=Journal of Learning Disabilities|year=2000|volume=33|issue=2|pages=179–191|doi=10.1177/002221940003300206|pmid=15505947|author1=Willcutt|first1=E. G.|last2=Pennington|first2=B. F.}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=Etiology and neuropsychology of comorbidity between RD and ADHD: The case for multiple-deficit models|journal=Cortex|year=2010|volume=46|pages=1345–1361|doi=10.1016/j.cortex.2010.06.009|pmid=20828676 |issue=10|pmc=2993430|author1=Willcutt|first1=E. G.|last2=Betjemann|first2=R. S.|last3=McGrath|first3=L. M.|last4=Chhabildas|first4=N. A.|last5=Olson|first5=R. K.|last6=Defries|first6=J. C.|last7=Pennington|first7=B. F.}}</ref> | |||

| In early childhood, symptoms that correlate with a later diagnosis of dyslexia include ] and a lack of ].<ref name=Handler2011/> A common myth closely associates dyslexia with ] and reading letters or words backwards.<ref name="LilienfeldLynn2011">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8DlS0gfO_QUC&pg=PT88|title=50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology: Shattering Widespread Misconceptions about Human Behavior|last2=Lynn|first2=Steven Jay|last3=Ruscio|first3=John|last4=Beyerstein|first4=Barry L.|date=15 September 2011|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-1-4443-6074-5|pages=88–89|last1=Lilienfeld|first1=Scott O.|author-link1=Scott Lilienfeld|author-link4=Barry Beyerstein|access-date=19 May 2016|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109130327/https://books.google.com/books?id=8DlS0gfO_QUC&pg=PT88|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref> These behaviors are seen in many children as they learn to read and write, and are not considered to be defining characteristics of dyslexia.<ref name=Handler2011/> | |||

| Dyslexic children of school age may exhibit signs such as difficulty identifying or generating rhyming words, or counting syllables in words (which depend on ]).<ref name='Facoetti'>{{Cite journal |title=Visual spatial attention and speech segmentation are both impaired in preschoolers at familial risk for developmental dyslexia |journal=Dyslexia |date=27 July 2010 |pmid=20680993 |volume=16 |issue=3 |pages=226–239 |doi=10.1002/dys.413 |last1=Facoetti |first1=A |last2=Corradi |first2=N |last3=Ruffino |first3=M |last4=Gori |first4=S |last5=Zorzi |first5=M}}</ref> They may also show signs of difficulty segmenting words into individual sounds or blending sounds to make words (]).<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Abnormal pattern of cortical speech feature discrimination in 6-year-old children at risk for dyslexia |journal=Brain Res. |volume=1335 |issue= |pages=53–62 |date=June 2010 |pmid=20381471 |doi=10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.097 |last1=Lovio |first1=R |last2=Näätänen |first2=R |last3=Kujala |first3=T}}</ref> Difficulty with word retrieval or with naming things also feature.<ref>{{cite journal | year = 1999 | title = Naming-speed deficits and phonological memory deficits in Chinese developmental dyslexia | url = | journal = J Learn Disabil | volume = 2 | issue = 2| pages = 173–86 | doi = 10.1016/S1041-6080(00)80004-7}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |first1=Manon W. |last1=Jones |first2=Holly P. |last2=Branigan |first3=M. Louise |last3=Kelly |year=2009 |title=Dyslexic and nondyslexic reading fluency: Rapid automatized naming and the importance of continuous lists |url= |journal=Psychonomic Bulletin & Review |volume=16 |issue=3 |pages=567–72 |pmid=19451386 |doi=10.3758/PBR.16.3.567}}</ref> They are commonly poor spellers, which has been called dysorthographia or ] (]). Whole-word guesses and tendencies to omit or add letters or words when writing and reading are considered tell-tale signs.<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Spelling deficits in dyslexia: evaluation of an orthographic spelling training |journal=Ann Dyslexia |volume=60 |issue=1 |pages=18–39 |date=June 2010 |pmid=20352378 |doi=10.1007/s11881-010-0035-8|author1=Ise |first1=E |last2=Schulte-Körne |first2=G}}</ref> | |||

| School-age children with dyslexia may exhibit ] of difficulty in identifying or generating ], or counting the number of ]s in words—both of which depend on phonological awareness.<ref name="DAss">{{cite web |title=Dyslexia and Related Disorders |date=January 2003 |website=Alabama Dyslexia Association |publisher=] |access-date=29 April 2015 |url=http://idaalabama.org/Facts/Dyslexia_and_Related.pdf |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304124053/http://idaalabama.org/Facts/Dyslexia_and_Related.pdf |archive-date=4 March 2016 }}</ref> They may also show difficulty in segmenting words into individual sounds (such as sounding out the three sounds of ''k'', ''a'', and ''t'' in ''cat'') or may struggle to blend sounds, indicating reduced ].<ref name="PeerReid2014">{{cite book |last1=Peer |first1=Lindsay |last2=Reid |first2=Gavin |title=Multilingualism, Literacy and Dyslexia |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-aoABAAAQBAJ&pg=PA219 |year=2014 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-136-60899-5 |page=219 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109204808/https://books.google.com/books?id=-aoABAAAQBAJ&pg=PA219 |archive-date=9 January 2017 }}</ref> | |||

| Problems persist into adolescence and adulthood and may be accompanied by trouble summarizing stories as well as with memorizing, reading aloud, and learning foreign languages. Adult dyslexics can read with good comprehension, although they tend to read more slowly than non-dyslexics and perform worse at ] and nonsense word reading, a measure of phonological awareness.<ref>{{Cite journal |first1=Rosalie P. |last1=Fink |title=Literacy development in successful men and women with dyslexia |journal=Annals of Dyslexia |volume=40 |issue=1 |pages=311–346 |year=1998 |url=http://nic-nac-project.de/~davison/revFink98.html |doi=10.1007/s11881-998-0014-5}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |title=Uncoupling of reading and IQ over time: empirical evidence for a definition of dyslexia |journal=Psychol Sci |volume=21 |issue=1 |pages=93–101 |date=January 2010 |pmid=20424029 |doi=10.1177/0956797609354084|author1=Ferrer |first1=E |last2=Shaywitz |first2=B. A. |last3=Holahan |first3=J. M. |last4=Marchione |first4=K |last5=Shaywitz |first5=S. E.}}</ref> | |||

| Difficulties with word retrieval or naming things is also associated with dyslexia.<ref name="Shaywitz2013a">{{cite book|author1=Shaywitz, Sally E.|author2=Shaywitz, Bennett A.|chapter=Chapter 34 Making a Hidden Disability Visible: What Has Been Learned from Neurobiological Studies of Dyslexia|editor1=Swanson, H. Lee|editor2=Harris, Karen R.|editor3=Graham, Steve|title=Handbook of Learning Disabilities|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oakQfUuutVwC&pg=PA647|edition=2|year=2013|publisher=Guilford Press|isbn=978-1-4625-0856-3|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109143943/https://books.google.com/books?id=oakQfUuutVwC&pg=PA647|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref>{{rp|647}} People with dyslexia are commonly poor ], a feature sometimes called ''dysorthographia'' or '']'', which depends on the skill of ].<ref name="Handler2011" /> | |||

| A common misconception about dyslexia assumes that dyslexic readers all write words backwards or move letters around when reading. In fact this only occurs among half of dyslexic readers.<ref name="MatherWendling2011">{{cite book|author1=Nancy Mather|author2=Barbara J. Wendling|author3=Alan S Kaufman, Ph.D.|title=Essentials of Dyslexia Assessment and Intervention|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=k6Gg-zMYv14C&pg=PT28|accessdate=10 April 2012|date=20 September 2011|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-1-118-15266-9|pages=28–}}</ref> | |||

| Problems persist into adolescence and adulthood and may include difficulties with summarizing stories, memorization, reading aloud, or learning foreign languages. Adults with dyslexia can often read with good comprehension, though they tend to read more slowly than others without a learning difficulty and perform worse in ] tests or when reading nonsense words—a measure of phonological awareness.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Jarrad|first1=Lum|title=Procedural learning is impaired in dyslexia: evidence from a meta-analysis of serial reaction time studies|journal=Research in Developmental Disabilities|date=October 2013|pages=3460–76|pmid=23920029|pmc=3784964|doi=10.1016/j.ridd.2013.07.017|volume=34|issue=10}}</ref> | |||

| ===Language=== | |||

| {{Main|Orthographies and dyslexia}} | |||

| The complexity of a language's orthography (i.e., its conventional spelling system, see ]) has a direct impact upon how difficult it is to learn to read that language. English has a comparatively deep orthography within the ] ], with a complex structure that employs spelling patterns of several levels: principally, letter-sound correspondences, syllables, and ]s. Other languages, such as Spanish, have mostly alphabetic orthographies that employ letter-sound correspondences, so-called ], making them relatively easy to learn. English, by comparison, presents more of a challenge.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Henry|first=Marcia K. |year=2005 |chapter=The history and structure of the English language|editor=Judith R. Birsh |title=Multisensory Teaching of Basic Language Skills |page=154|publisher=Paul H. Brookes Publishing |location=Baltimore, Maryland |isbn=978-1-55766-676-5|oclc=234335596}}</ref> ]ic writing systems, notably ] and ]s, have ]s that are not linked directly to their pronunciation, which pose a different type of difficulty to the dyslexic learner.<ref name=kana>{{Cite journal |title=Reading ability and phonological awareness in Japanese children with dyslexia |journal=Brain Dev.|volume=30 |issue=3 |pages=179–88 |date=March 2008 |pmid=17720344|doi=10.1016/j.braindev.2007.07.006|author1=Seki|first1=A|last2=Kassai|first2=K|last3=Uchiyama|first3=H|last4=Koeda|first4=T}}</ref><ref name=lang>{{cite journal |bibcode=2008PNAS..105.5561S|title=A structural-functional basis for dyslexia in the cortex of Chinese readers|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume=105|pages=5561|author1=Siok|first1=Wai Ting|last2=Niu|first2=Zhendong|last3=Jin|first3=Zhen|last4=Perfetti|first4=Charles A.|last5=Tan|first5=Li Hai|year=2008|doi=10.1073/pnas.0801750105}}</ref> Different neurological deficits may cause varying degrees of difficulty in learning one writing system when compared to another, as the neurological skills required to read, write, and spell can vary between systems.<ref name=kana/> | |||

| ===Associated conditions=== | ===Associated conditions=== | ||

| Dyslexia often co-occurs with other learning disorders, but the reasons for this comorbidity have not been clearly identified.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Dyslexia, dysgraphia, procedural learning and the cerebellum |journal=Cortex |volume=47 |issue=1 |pages=117–27 |date=September 2009|pmid=19818437 |doi=10.1016/j.cortex.2009.08.016|last1=Nicolson |first1=R. I. |last2=Fawcett |first2=A. J.|s2cid=32228208 }}</ref> These associated disabilities include: | |||

| *] – A disorder which expresses itself primarily through writing or typing, although in some cases it may also affect ], direction- or sequence-oriented processes such as tying knots or carrying out a repetitive task. In dyslexia, dysgraphia is often multifactorial, due to impaired letter writing automaticity, finger motor sequencing challenges, organizational and elaborative difficulties, and impaired visual word form which makes it more difficult to retrieve the visual picture of words required for spelling.<ref>{{cite journal |first1=S. |last1=Bhattacharyya |first2=X. |last2=Cai |first3=J. P. |last3=Klein |year=2014 |title=Dyscalculia, Dysgraphia, and Left-Right Confusion from a Left Posterior Peri-Insular Infarct |journal=Behavioural Neurology |volume= |issue= |pages= |pmid=24817791 |pmc=4006625 |doi=10.1155/2014/823591}}</ref><ref name="ReynoldsFletcher-Janzen2007a">{{cite book|author1=Cecil R. Reynolds|author2=Elaine Fletcher-Janzen|title=Encyclopedia of Special Education|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=wdNpBchvdvQC&pg=PA771|year=2007|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-0-471-67798-7|page=771}}</ref> | |||

| ; ]: A disorder involving difficulties with ] or ], sometimes due to problems with ]; it also can impede direction- or sequence-oriented processes, such as ] or carrying out repetitive tasks.<ref name=ReynoldsFletcherJanzen2007>{{cite book |last1=Reynolds |first1=Cecil R. |last2=Fletcher-Janzen |first2=Elaine |title=Encyclopedia of Special Education |date=2 January 2007 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |isbn=978-0-471-67798-7 |page= }}</ref> In dyslexia, dysgraphia is often multifactorial, due to impaired letter-writing ], organizational and elaborative difficulties, and impaired visual word forming, which makes it more difficult to retrieve the visual picture of words required for spelling.<ref name=ReynoldsFletcherJanzen2007/> | |||

| *] – A significant degree of ] has been reported between ADHD and dyslexia or reading disorders;<ref name="ComerGould2010">{{cite book|author1=Ronald Comer|author2=Elizabeth Gould|title=Psychology Around Us|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=ySIc1BcPJu8C&pg=RA1-PA233|date=January 19, 2010|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-0-471-38519-6|page=1}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |title=Comorbidity of ADHD and Dyslexia |journal=Developmental Neuropsychology |volume=35|issue=5 |pages=475–493 |year=2010 |doi=10.1080/87565641.2010.494748 |url=http://pdfserve.informaworld.com/260009__925867416.pdf |pmid=20721770|author1=Germanò |first1=E |last2=Gagliano |first2=A |last3=Curatolo |first3=P}}</ref> it occurs in 12–24% of all individuals with dyslexia.<ref name=Birsh2005/> Research studying the impact of interference on adults with and without dyslexia has revealed large differences in terms of attention deficits for adults with dyslexia, and has implications for teaching reading and writing to dyslexics in the future.<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Stroop interference in adults with dyslexia |journal=Neurocase |pages=1–5 |date=May 2014 |pmid=24814960 |doi=10.1080/13554794.2014.914544|author1=Proulx |first1=M. J. |last2=Elmasry |first2=H. M.}}</ref> | |||

| ; ] (ADHD): A disorder characterized by problems sustaining attention, hyperactivity, or acting impulsively.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd/index.shtml|title=Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder|date=March 2016|publisher=NIH: National Institute of Mental Health|access-date=26 July 2016|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160723192735/http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd/index.shtml|archive-date=23 July 2016}}</ref> Dyslexia and ADHD commonly occur together.<ref name="Koo2013" /><ref name="ComerGould2010">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ySIc1BcPJu8C&pg=RA1-PA233|title=Psychology Around Us|date=2011|publisher=RR Donnelley|isbn=978-0-471-38519-6|page=1|author1=Comer, Ronald|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160604000711/https://books.google.com/books?id=ySIc1BcPJu8C&pg=RA1-PA233|archive-date=4 June 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last2=Gagliano|first2=A|last3=Curatolo|first3=P|year=2010|title=Comorbidity of ADHD and Dyslexia|url=http://pdfserve.informaworld.com/260009__925867416.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110810101321/http://pdfserve.informaworld.com/260009__925867416.pdf |archive-date=2011-08-10 |url-status=live|journal=Developmental Neuropsychology|volume=35|issue=5|pages=475–493|doi=10.1080/87565641.2010.494748|pmid=20721770|last1=Germanò|first1=E|s2cid=42046958}}</ref> Approximately 15%<ref name="Handler2011" /> or 12–24% of people with dyslexia have ADHD;<ref name="FatemiSartorius2008">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RJOy1vy2RKQC&pg=PA308|title=The Medical Basis of Psychiatry|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|year=2008|isbn=978-1-59745-252-6|edition=3rd |page=308|author1=Fatemi, S. Hossein|author2=Sartorius, Norman|author3=Clayton, Paula J.|author3-link=Paula Clayton|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109101234/https://books.google.com/books?id=RJOy1vy2RKQC&pg=PA308|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref> and up to 35% of people with ADHD have dyslexia.<ref name="Handler2011" /> | |||

| *] – A condition that affects the ability to process auditory information. Auditory processing disorder is a listening disability.<ref name="Capellini2007a">{{cite book|author=Simone Aparecida Capellini|title=Neuropsycholinguistic Perspectives on Dyslexia and Other Learning Disabilities|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uiEaMQVwyzYC&pg=PA94|year=2007|publisher=Nova Publishers|isbn=978-1-60021-537-7|page=94}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=The diagnosis and management of auditory processing disorder|journal=Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch |volume=42 |issue=3 |pages=303–8 |date=July 2011 |pmid=21757566 |doi=10.1044/0161-1461(2011/10-0032)|author1=Moore |first1=D. R.}}</ref> It can lead to problems with ] and auditory ]. Many people with dyslexia have auditory processing problems<ref>{{cite journal |title=Auditory processing disorder in children with reading disabilities: effect of audiovisual training |journal=Brain |volume=130 |issue=Pt 11 |pages=2915–28 |date=November 2007 |pmid=17921181 |doi=10.1093/brain/awm235|author1=Veuillet |first1=E |last2=Magnan |first2=A |last3=Ecalle |first3=J |last4=Thai-Van |first4=H |last5=Collet |first5=L}}</ref> and may develop their own ] to compensate for this type of deficit. Auditory processing disorder is recognized as one of the major causes of dyslexia.<ref name=Ramus1>{{Cite journal |title=Developmental dyslexia: specific phonological deficit or general sensorimotor dysfunction? |journal=Current Opinion in Neurobiology |volume=13 |issue=2|pages=212–8 |date=April 2003 |pmid=12744976 |doi=10.1016/S0959-4388(03)00035-7 |last1=Ramus |first1=F}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |first=Deborah |last=Moncrieff | |||

| ; ]: A listening disorder that affects the ability to process auditory information.<ref name="Capellini2007a">{{cite book|author=Capellini, Simone Aparecida|title=Neuropsycholinguistic Perspectives on Dyslexia and Other Learning Disabilities|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uiEaMQVwyzYC&pg=PA94|year=2007|publisher=Nova Publishers|isbn=978-1-60021-537-7|page=94|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109113545/https://books.google.com/books?id=uiEaMQVwyzYC&pg=PA94|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=The diagnosis and management of auditory processing disorder|journal= Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools|volume=42 |issue=3 |pages=303–8 |date=July 2011 |pmid=21757566 |doi=10.1044/0161-1461(2011/10-0032)|last1=Moore |first1=D. R.}}</ref> This can lead to problems with ] and auditory ]. Many people with dyslexia have auditory processing problems, and may develop their own ] to compensate for this type of deficit. Some research suggests that auditory processing skills could be the primary shortfall in dyslexia.<ref name=Pammer2014>{{cite journal|last1=Pammer|first1=Kristen|title=Brain mechanisms and reading remediation: more questions than answers.|journal=Scientifica|date=January 2014|pmid=24527259|pmc=3913493|doi=10.1155/2014/802741|volume=2014|pages=802741|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Law|first1=J|title=relationship of phonological ability, speech perception, and auditory perception in adults with dyslexia|journal=Frontiers in Human Neuroscience|date=2014|pmid=25071512|pmc=4078926|doi=10.3389/fnhum.2014.00482|volume=8|pages=482|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| |title=Temporal Processing Deficits in Children with Dyslexia |date=2 February 2004|publisher=speechpathology.com|url=http://www.speechpathology.com/articles/article_detail.asp?article_id=59|work=speechpathology.com |accessdate=13 May 2009}}</ref> | |||

| ; ]: A neurological condition characterized by difficulty in carrying out routine tasks involving balance, fine-] and ] coordination; difficulty in the use of speech sounds; and problems with ] and organization.<ref name=Pickering2012>{{cite book|author=Susan J. Pickering|chapter=Chapter 2. Working Memory in Dyslexia|editor1=Alloway, Tracy Packiam|editor2=Gathercole, Susan E.|title=Working Memory and Neurodevelopmental Disorders|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IoXidOBdNpMC&pg=PA29|year=2012|publisher=Psychology Press|isbn=978-1-135-42134-2|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109194637/https://books.google.com/books?id=IoXidOBdNpMC&pg=PA29|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref> | |||

| == Causes == | == Causes == | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Researchers have been trying to find the neurobiological basis of dyslexia since the condition was first identified in 1881.<ref name="Oswald Berkhan ref 1" /><ref name="ReidFawcett2008x">{{cite book|author1=Reid, Gavin|author2=Fawcett, Angela|author3=Manis, Frank|author4=Siegel, Linda|title=The SAGE Handbook of Dyslexia|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=937rqz4Ryc8C&pg=PA127|year=2008|publisher=SAGE Publications|isbn=978-1-84860-037-9|page=127|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109200307/https://books.google.com/books?id=937rqz4Ryc8C&pg=PA127|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref> For example, some have tried to associate the common problem among people with dyslexia of not being able to see letters clearly to abnormal development of their visual nerve cells.<ref name="Stein2014" >{{cite journal |first1=John |last1=Stein |year=2014 |title=Dyslexia: the Role of Vision and Visual Attention |journal=Current Developmental Disorders Reports |volume=1 |issue=4 |pages=267–80 |pmid=25346883 |pmc=4203994 |doi=10.1007/s40474-014-0030-6}}</ref> | |||

| {{main|Theories of dyslexia}} | |||

| Researchers have been trying to find the neurobiological basis of dyslexia since it was first identified in 1881.<ref name="Oswald Berkhan ref 1" /> An example of one of the problems dyslexics experience would be seeing letters clearly, this may be due to abnormal development of their visual nerve cells.<ref name=pmid25346883>{{cite journal |first1=John |last1=Stein |year=2014 |title=Dyslexia: the Role of Vision and Visual Attention |journal=Current Developmental Disorders Reports |volume=1 |issue=4 |pages=267–80 |pmid=25346883 |pmc=4203994}}</ref> | |||

| ===Neuroanatomy=== | ===Neuroanatomy=== | ||

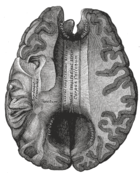

| ] techniques, such as ] (]) and ] (PET), have shown a correlation between both functional and structural differences in the brains of children with reading difficulties.<ref name="Whitaker2010r">{{cite book|author=Whitaker, Harry A.|title=Concise Encyclopedia of Brain and Language|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GNcDiRV2jJQC&pg=PA180|year=2010|publisher=Elsevier|isbn=978-0-08-096499-7|page=180|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109173223/https://books.google.com/books?id=GNcDiRV2jJQC&pg=PA180|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref> Some people with dyslexia show less activation in parts of the left hemisphere of the brain involved with reading, such as the ], ], and the middle and ].<ref name=Pammer2014/> Over the past decade, brain activation studies using PET to study language have produced a breakthrough in the understanding of the neural basis of language. Neural bases for the visual ] and for auditory verbal ] components have been proposed,<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Price|first1=cathy|title=A Review and Synthesis of the first 20 years of Pet and fMRI studies of heard Speech, Spoken Language and Reading|journal=NeuroImage|date=16 August 2012|volume=62 |issue=2|pages=816–847|doi=10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.062|pmid=22584224|pmc=3398395}}</ref> with some implication that the observed neural manifestation of developmental dyslexia is task-specific (i.e., functional rather than structural). fMRIs of people with dyslexia indicate an interactive role of the ] and cerebral cortex as well as other brain structures in reading.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Sharifi|first1=S|title=Neuroimaging essentials in essential tremor: a systematic review.|journal=NeuroImage: Clinical|date=May 2014|pages=217–231|pmid=25068111|pmc=4110352|doi=10.1016/j.nicl.2014.05.003|volume=5}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Brandler|first1=William|title=The genetic relationship between handedness and neurodevelopmental disorders|journal=Trends in Molecular Medicine|date=February 2014|pages=83–90|pmid=24275328|pmc=3969300|doi=10.1016/j.molmed.2013.10.008|volume=20|issue=2}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Neurological research into dyslexia}} | |||

| In the area of neurological research into dyslexia, modern ] techniques such as ] (]) and ] (PET) have produced a correlation between functional and structural differences in the brains of children with reading difficulties. Some individuals with dyslexia show less electrical activation in parts of the left hemisphere of the brain involved in reading, which includes the ], ], and middle and ].<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Deficient orthographic and phonological representations in children with dyslexia revealed by brain activation patterns |journal=Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines |volume=47 |issue=10 |pages=1041–50 |date=October 2006 |pmid=17073983 |pmc=2617739 |doi=10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01684.x|author1=Cao |first1=F |last2=Bitan |first2=T |last3=Chou |first3=T. L. |last4=Burman |first4=D. D. |last5=Booth |first5=J. R.}}</ref> Brain activation studies using PET to study language have produced a breakthrough in understanding of the neural basis of language over the past decade. A neural basis for the visual ] and for auditory verbal ] components have been proposed,<ref>{{Cite journal |title=PET activation and language |journal=Clinical Neuroscience |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=78–86 |year=1997 |pmid=9059757 |url=http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/nuclearscans.html|author1=Chertkow |first1=H |last2=Murtha |first2=S }}</ref> with some implication that the observed neural manifestation of developmental dyslexia is task-specific (i.e., functional rather than structural).<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Abnormal functional activation during a simple word repetition task: A PET study of adult dyslexics |journal=Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience |volume=12 |issue=5 |pages=753–62 |date=September 2000 |pmid=11054918 |doi=10.1162/089892900562570|author1=McCrory |first1=E |last2=Frith |first2=U |last3=Brunswick |first3=N |last4=Price |first4=C}}</ref> fMRIs in dyslexics have provided important data supporting the interactive role of the cerebellum and cerebral cortex as well as other brain structures.<ref name="Schmahmann">{{Cite journal |journal=Brain |title=The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome |volume=121 |pages=561–79 |last1=Schmahmann |first1=J. D. |last2=Sherman |first2=J. C. |year=1998 |doi=10.1093/brain/121.4.561 |pmid=9577385 |issue=4}}</ref><ref name="Rae et al">{{cite journal |first1=Caroline |last1=Rae |first2=Jenny A |last2=Harasty |first3=Theresa E |last3=Dzendrowskyj |first4=Joel B |last4=Talcott |first5=Judy M |last5=Simpson |first6=Andrew M |last6=Blamire |first7=Ruth M |last7=Dixon |first8=Martin A |last8=Lee |first9=Campbell H |last9=Thompson |first10=Peter |last10=Styles |first11=Alex J |last11=Richardson |first12=John F |last12=Steine |year=2002 |title=Cerebellar morphology in developmental dyslexia |journal=Neuropsychologia |volume=40 |issue=8 |pages=1285–92 |pmid=11931931 |doi=10.1016/S0028-3932(01)00216-0}}</ref> | |||

| The cerebellar theory of dyslexia proposes that impairment of cerebellum-controlled muscle movement affects the formation of words by the tongue and facial muscles, resulting in the ] problems that some people with dyslexia experience. The cerebellum is also involved in the ] of some tasks, such as reading.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Cain|first1=Kate|title=Reading development and difficulties|date=2010|publisher=TJ International|page=134|edition=1st|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FT6RALjOr9QC&q=cerebellar+theory+of+dyslexia&pg=PA134|access-date=21 March 2015|isbn=9781405151559}}</ref> The fact that some children with dyslexia have motor task and balance impairments could be consistent with a cerebellar role in their reading difficulties. However, the cerebellar theory has not been supported by controlled research studies.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Levav|first1=Itzhak|title=Psychiatric and Behavioral Disorders in Israel: From Epidemiology to Mental health|date=2009|publisher=Green Publishing|page=52|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=W2RzffMnpg8C&q=cerebellar+theory+of+dyslexia&pg=PA52|access-date=21 March 2015|isbn=9789652294685}}</ref> | |||

| ===Genetics=== | ===Genetics=== | ||

| Research into potential genetic causes of dyslexia has its roots in post-autopsy examination of the brains of people with dyslexia.<ref name="Stein2014" /> Observed anatomical differences in the ]s of such brains include microscopic ] malformations known as ], and more rarely, ] micro-malformations, and ]—a smaller than usual size for the gyrus.<ref name="Faust2012">{{cite book|author=Faust, Miriam|title=The Handbook of the Neuropsychology of Language|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UEWVqdNFL4cC&pg=PA941|year=2012|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-1-4443-3040-3|pages=941–43|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109200538/https://books.google.com/books?id=UEWVqdNFL4cC&pg=PA941|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref> The previously cited studies and others<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Benitez|first1=A|title=Neurobiology and neurogenetics of dyslexia|journal=Neurology (In Spanish)|date=November 2010|pmid=21093706|doi=10.1016/j.nrl.2009.12.010|volume=25|issue=9|pages=563–81|doi-access=}}</ref> suggest that abnormal cortical development, presumed to occur before or during the sixth month of ] brain development, may have caused the abnormalities. Abnormal cell formations in people with dyslexia have also been reported in non-language cerebral and subcortical brain structures.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Kere|first1=Julia|title=The molecular genetics and neurobiology of developmental dyslexia as model of a complex phenotype|journal=Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications|date=September 2014|pages=236–43|doi=10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.07.102|pmid=25078623|volume=452|issue=2|doi-access=free}}</ref> Several genes have been associated with dyslexia, including ]<ref name="Marshall2012v">{{cite book|author=Marshall, Chloë R.|title=Current Issues in Developmental Disorders|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jHqYP39rI40C&pg=PA53|year=2012|publisher=Psychology Press|isbn=978-1-136-23067-7|pages=53–56|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109103320/https://books.google.com/books?id=jHqYP39rI40C&pg=PA53|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref> and ]<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Paracchini S, Thomas A, Castro S, Lai C, Paramasivam M, Wang Y, Keating BJ, Taylor JM, Hacking DF, Scerri T, Francks C, Richardson AJ, Wade-Martins R, Stein JF, Knight JC, Copp AJ, LoTurco J, Monaco AP |title=The chromosome 6p22 haplotype associated with dyslexia reduces the expression of KIAA0319, a novel gene involved in neuronal migration|journal=Human Molecular Genetics|volume=15|issue=10|date=15 May 2006|pages=1659–1666|doi=10.1093/hmg/ddl089|pmid=16600991|doi-access=free|hdl=11858/00-001M-0000-0012-C979-F|hdl-access=free}}</ref> on ], and ] on ].<ref name="Rosen2013v">{{cite book|author=Rosen, Glenn D.|title=The Dyslexic Brain: New Pathways in Neuroscience Discovery|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZHBxBEekGSkC&pg=PA342|year=2013|publisher=Psychology Press|isbn=978-1-134-81550-0|page=342|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109143349/https://books.google.com/books?id=ZHBxBEekGSkC&pg=PA342|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Genetic research into dyslexia}} | |||

| Genetic research into dyslexia and its inheritance has its roots in the examination of post-] brains of people with dyslexia.<ref name="GalaburdaKempe">{{cite journal |title=Cytoarchitectonic abnormalities in developmental dyslexia: A case study |journal=Annals of Neurology |volume=6 |issue=2 |pages=94–100 |date=August 1979 |pmid=496415 |doi=10.1002/ana.410060203|author1=Galaburda |first1=A. M. |last2=Kemper |first2=T. L.}}</ref><ref name="Galaburda">{{Cite journal |title=Developmental dyslexia: four consecutive patients with cortical abnormalities |last1=Galaburda |first1=A.M. |last2=Sherman |first2= G.F. |last3=Rosen |first3=G.D. |last4=Aboitiz |first4=F. |last5=Geschwind |first5=N. |journal=Annals of Neurology |date=August 1985 |volume=18 |number= |pages=222–223|pmid=4037763 |doi=10.1002/ana.410180210 |issue=2}}</ref> When they observed anatomical differences in the ] in a dyslexic brain, they showed microscopic ] malformations known as ] and more rarely ] micro-malformations, and in some instances these cortical malformations appeared as a ]. These studies and those of Cohen et al. 1989<ref>{{cite journal |title=Neuropathological abnormalities in developmental dysphasia |journal=Annals of Neurology |volume=25 |issue=6 |pages=567–70 |date=June 1989 |pmid=2472772 |doi=10.1002/ana.410250607|author1=Cohen |first1=M |last2=Campbell |first2=R |last3=Yaghmai |first3=F}}</ref> suggested abnormal cortical development which was presumed to occur before or during the sixth month of ] brain development.<ref name='Habib'>{{cite journal |title=The neurological basis of developmental dyslexia: an overview and working hypothesis |journal=Brain |volume=123 |issue=Pt 12 |pages=2373–99 |date=December 2000 |pmid=11099442 |doi=10.1093/brain/123.12.2373|author1=Habib |first1=M}}</ref> Abnormal cell formations in dyslexics found on autopsy have also been reported in non-language cerebral and subcortical brain structures.<ref name="Galaburda"/><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Livingstone |first1=Margaret S. |last2=Rosen |first2=Glenn D. |last3=Drislane |first3=Frank W. |last4=Galaburda |first4=Albert M. |year=1991 |title=Physiological and Anatomical Evidence for a Magnocellular Defect in Developmental Dyslexia |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America |volume=88 |issue=18 |pages=7943–7 |pmid=1896444 |pmc=52421 |bibcode=1991PNAS...88.7943L |doi=10.1073/pnas.88.18.7943}}</ref> MRI data have confirmed a cerebellar role in dyslexia.<ref>{{cite journal |first1=Caroline |last1=Rae |first2=Martin A |last2=Lee |first3=Ruth M |last3=Dixon |first4=Andrew M |last4=Blamire |first5=Campbell H |last5=Thompson |first6=Peter |last6=Styles |first7=Joel |last7=Talcott |first8=Alexandra J |last8=Richardson |first9=John F |last9=Stein |display-authors=9 |date=20 June 1998 |title=Metabolic abnormalities in developmental dyslexia detected by <sup>1</sup>H Magnetic resonance spectroscopy |journal=The Lancet |volume=351 |issue=9119 |pages=1893–52 |pmid=9652669 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(97)99001-2}}</ref> | |||

| ===Gene–environment interaction=== | ===Gene–environment interaction=== | ||

| The contribution of gene–environment interaction to reading disability has been intensely studied using ], which estimate the proportion of variance associated with a person's environment and the proportion associated with their genes. Both environmental and genetic factors appear to contribute to reading development. Studies examining the influence of environmental factors such as parental education<ref>{{cite journal |title=Parental Education Moderates Genetic Influences on Reading Disability |journal=Psychol. Sci. |volume=19 |issue=11 |pages=1124–30 |date=November 2008 |pmid=19076484 |pmc=2605635 |doi=10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02213.x |last1=Friend |first1=A |last2=Defries |first2=J. C. |last3=Olson |first3=R. K.}}</ref> and teaching quality<ref>{{cite journal |bibcode=2010Sci...328..512T|title=Teacher Quality Moderates the Genetic Effects on Early Reading|journal=Science|volume=328|issue=5977|pages=512–4|last1=Taylor|first1=J.|last2=Roehrig|first2=A. D.|last3=Hensler|first3=B. Soden|last4=Connor|first4=C. M.|last5=Schatschneider|first5=C.|year=2010|doi=10.1126/science.1186149|pmid=20413504|pmc=2905841}}</ref> have determined that genetics have greater influence in supportive, rather than less optimal, environments.<ref name=pmid19209992>{{cite journal |last1=Pennington |first1=Bruce F. |last2=McGrath |first2=Lauren M. |last3=Rosenberg |first3=Jenni |last4=Barnard |first4=Holly |last5=Smith |first5=Shelley D. |last6=Willcutt |first6=Erik G. |last7=Friend |first7=Angela |last8=Defries |first8=John C. |last9=Olson |first9=Richard K. |date=January 2009 |title=Gene × Environment Interactions in Reading Disability and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |journal=Developmental Psychology |volume=45 |issue=1 |pages=77–89 |doi=10.1037/a0014549 |pmid=19209992 |pmc=2743891}}</ref> However, more optimal conditions may just allow those genetic risk factors to account for more of the variance in outcome because the environmental risk factors have been minimized.<ref name=pmid19209992/> | |||

| {{Main|Gene–environment interaction}} | |||

| Research has examined gene–environment interactions in reading disability through ], which estimate the proportion of variance associated with environment and the proportion associated with ]. Studies examining the influence of environmental factors such as parental education<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Parental Education Moderates Genetic Influences on Reading Disability |journal=Psychol Sci. |volume=19 |issue=11 |pages=1124–1130 |date=November 2008 |pmid=19076484 |doi=10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02213.x |pmc=2605635|author1=Friend |first1=A |last2=Defries |first2=J. C. |last3=Olson |first3=R. K.}}</ref> and teacher quality<ref>{{cite journal |bibcode=2010Sci...328..512T|title=Teacher Quality Moderates the Genetic Effects on Early Reading|journal=Science|volume=328|issue=5977|pages=512–4|author1=Taylor|first1=J.|last2=Roehrig|first2=A. D.|last3=Hensler|first3=B. Soden|last4=Connor|first4=C. M.|last5=Schatschneider|first5=C.|year=2010|doi=10.1126/science.1186149|pmid=20413504|pmc=2905841}}</ref> have determined that genetics has greater influence in supportive, rather than less optimal, environments.<ref name=pmid19209992>{{cite journal |last1=Pennington |first1=Bruce F. |last2=McGrath |first2=Lauren M. |last3=Rosenberg |first3=Jenni |last4=Barnard |first4=Holly |last5=Smith |first5=Shelley D. |last6=Willcutt |first6=Erik G. |last7=Friend |first7=Angela |last8=Defries |first8=John C. |last9=Olson |first9=Richard K. |display-authors=9 |date=January 2009 |title=Gene × Environment Interactions in Reading Disability and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |journal=Developmental Psychology |volume=45 |issue=1 |pages=77–89 |doi=10.1037/a0014549 |pmid=19209992 |pmc=2743891}}</ref> Instead, it may just allow those genetic risk factors to account for more of the variance in outcome, because environmental risk factors that affect that outcome have been minimized.<ref name=pmid19209992/> As the environment plays a large role in learning and memory, it is likely that ] modifications play an important role in reading ability. ] and measures of ] and ] in the human periphery are used to study epigenetic processes, both of which have many limitations in extrapolating results for application to the human brain.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Roth |first=Tania L. |last2=Roth |first2=Eric D. |last3=Sweatt |first3=J. David |date=September 2010 |title=Epigenetic regulation of genes in learning and memory |journal=Essays in Biochemistry |volume=48 |issue=1 |pages=263–74 |pmid=20822498 |doi=10.1042/bse0480263}}</ref> | |||

| As environment plays a large role in learning and memory, it is likely that ] modifications play an important role in reading ability. Measures of ], ], and ] in the human periphery are used to study epigenetic processes; however, all of these have limitations in the extrapolation of results for application to the human brain.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Roth |first1=Tania L. |last2=Roth |first2=Eric D. |last3=Sweatt |first3=J. David |s2cid=23229766 |date=September 2010 |title=Epigenetic regulation of genes in learning and memory |journal=Essays in Biochemistry |volume=48 |issue=1 |pages=263–74 |pmid=20822498 |doi=10.1042/bse0480263}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Smith |first1=Shelley D. |title=Approach to epigenetic analysis in language disorders |journal=Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders |date=December 2011 |volume=3 |issue=4 |pages=356–364 |doi=10.1007/s11689-011-9099-y |pmid=22113455 |pmc=3261263 |issn=1866-1947}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| == |

====Language==== | ||

| The ] of a language directly affects how difficult it is to learn to read it.<ref name="BrunswickMcDougall2010"> | |||

| {{Main|Dual-route hypothesis to reading aloud}} | |||

| Paulesu, Eraldo; Brunswick, Nicola and Paganelli, Federica (2010). "Cross-cultural differences in unimpaired and dyslexic reading: Behavioral and functional anatomical observations in readers of regular and irregular orthographies. Chapter 12 in {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109135414/https://books.google.com/books?id=0vJ5AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA266 |date=9 January 2017 }}. Eds. Nicola Brunswick, Siné McDougall, and Paul de Mornay Davies. Psychology Press. {{ISBN|9781135167813}}</ref>{{rp|266}} English and French have comparatively "deep" ] within the ] ], with complex structures employing spelling patterns on several levels: letter-sound correspondence, syllables, and ]s.<ref name="DickinsonNeuman2013">{{cite book|author=Juel, Connie|chapter=The Impact of Early School Experiences on Initial Reading|editor1=David K. Dickinson|editor2=Susan B. Neuman|title=Handbook of Early Literacy Research|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_chXAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA421|year=2013|publisher=Guilford Publications|isbn=978-1-4625-1470-0|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109162332/https://books.google.com/books?id=_chXAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA421|archive-date=9 January 2017|df=dmy-all}}</ref>{{rp|421}} Languages such as Spanish, Italian and Finnish primarily employ letter-sound correspondence—so-called "shallow" orthographies—which makes them easier to learn for people with dyslexia.<ref name="BrunswickMcDougall2010"/>{{rp|266}} ]ic writing systems, such as ], have extensive symbol use; and these also pose problems for dyslexic learners.<ref>{{cite journal|title = Annual Research Review: The nature and classification of reading disorders – a commentary on proposals for DSM-5|journal = Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines|date = 1 May 2012|pmc = 3492851|pmid = 22141434|pages = 593–607|volume = 53|issue = 5|doi = 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02495.x|first1 = Margaret J|last1 = Snowling|first2 = Charles|last2 = Hulme}}</ref> | |||

| The dual-route theory of ] aloud was first described in the early 1970s.<ref name="Pritchard 2012">{{cite journal |author=Pritchard SC, Coltheart M, Palethorpe S, Castles A |title=Nonword reading: comparing dual-route cascaded and connectionist dual-process models with human data |journal=J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform |volume=38 |issue=5 |pages=1268–88 |date=October 2012 |pmid=22309087 |doi=10.1037/a0026703|last2=Coltheart |last3=Palethorpe |last4=Castles}}</ref> This theory suggests that two separate mental mechanisms, or cognitive routes, are involved in reading aloud, with output of both mechanisms contributing to the ] of a written stimulus.<ref name=coltheart1>{{cite journal|last=Coltheart|first=Max|author2=Curtis, Brent|author3= Atkins, Paul|author4= Haller, Micheal|title=Models of reading aloud: Dual-route and parallel-distributed-processing approaches|journal=Psychological Review|date=1 January 1993|volume=100|issue=4|pages=589–608|doi=10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.589}}</ref><ref name="Yamada 1990">{{cite journal |title=The use of the orthographic lexicon in reading kana words |journal=J Gen Psychol |volume=117 |issue=3 |pages=311–23 |date=July 1990 |pmid=2213002|author1=Yamada |first1=J |last2=Imai |first2=H |last3=Ikebe |first3=Y }}</ref> One mechanism is the ''lexical route'', which is the process whereby skilled readers can recognize known words by sight alone, through a “dictionary” lookup procedure.<ref name="Pritchard 2012" /><ref name="Zorzi Houghton 1998">{{cite journal|last1=Zorzi|first1=Marco|last2=Houghton|first2=George|last3=Butterworth|first3=Brian|title=Two routes or one in reading aloud? A connectionist dual-process model|journal=Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance |volume=24| issue=4| year=1998| pages=1131–1161 |doi=10.1037/0096-1523.24.4.1131}}</ref> The other mechanism is the ''nonlexical'' or ''sublexical route'', which is the process whereby the reader can “sound out” a written word. This is done by identifying the word's constituent parts (letters, ], ]) and applying knowledge of how these parts are associated with each other, for example how a string of neighboring letters sound together.<ref name="Pritchard 2012" /><ref name="Zorzi Houghton 1998" /> | |||

| ==Pathophysiology== | |||

| ] | |||

| For most people who are right-hand dominant, the left hemisphere of their brain is more specialized for ]. With regard to the mechanism of dyslexia, fMRI studies suggest that this specialization is less pronounced or absent in people with dyslexia. In other studies, dyslexia is correlated with anatomical differences in the ], the bundle of nerve fibers that connects the left and right hemispheres.<ref name="habi">{{cite book |last1=Habib |first1=Michael |title=Pediatric Neurology Part I |volume=111 |chapter=Dyslexia |date=2013 |pages=229–235 |chapter-url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444528919000233 |access-date=19 December 2018 |language=en|doi=10.1016/B978-0-444-52891-9.00023-3 |pmid=23622168 |series=Handbook of Clinical Neurology |isbn=9780444528919 }}</ref> | |||

| Data via diffusion tensor MRI indicate changes in connectivity or in gray matter density in areas related to reading and language. Finally, the left ] has shown differences in phonological processing in people with dyslexia.<ref name=habi/> Neurophysiological and imaging procedures are being used to ascertain phenotypic characteristics in people with dyslexia, thus identifying the effects of dyslexia-related genes.<ref>{{cite journal|title = Genetics of dyslexia: the evolving landscape|journal = Journal of Medical Genetics|date = 2007|pmc = 2597981|pmid = 17307837|pages = 289–297|volume = 44|issue = 5|doi = 10.1136/jmg.2006.046516|first1 = Johannes|last1 = Schumacher|first2 = Per|last2 = Hoffmann|first3 = Christine|last3 = Schmäl|first4 = Gerd|last4 = Schulte-Körne|first5 = Markus M|last5 = Nöthen}}</ref> | |||

| ===Dual route theory=== | |||

| The dual-route theory of ] aloud was first described in the early 1970s.<ref name="Pritchard 2012">{{cite journal |author=Pritchard SC, Coltheart M, Palethorpe S, Castles A |title=Nonword reading: comparing dual-route cascaded and connectionist dual-process models with human data |journal=J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform |volume=38 |issue=5 |pages=1268–88 |date=October 2012 |pmid=22309087 |doi=10.1037/a0026703|last2=Coltheart |last3=Palethorpe |last4=Castles}}</ref> This theory suggests that two separate mental mechanisms, or cognitive routes, are involved in reading aloud.<ref name="EysenckKeane2013z">{{cite book|author1=Eysenck, Michael|author2=Keane, Mark T.|title=Cognitive Psychology 6e|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=U-IF8PAa_jIC&pg=PA373|year=2013|publisher=Psychology Press|isbn=978-1-134-44046-7|page=373|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109123837/https://books.google.com/books?id=U-IF8PAa_jIC&pg=PA373|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref> One mechanism is the lexical route, which is the process whereby skilled readers can recognize known words by sight alone, through a "dictionary" lookup procedure.<ref name="EysenckKeane2013">{{cite book|author1=Eysenck, Michael|author2=Keane, Mark T.|title=Cognitive Psychology 6e|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=U-IF8PAa_jIC&pg=PA450|year=2013|publisher=Psychology Press|isbn=978-1-134-44046-7|page=450|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109170422/https://books.google.com/books?id=U-IF8PAa_jIC&pg=PA450|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref> The other mechanism is the nonlexical or sublexical route, which is the process whereby the reader can "sound out" a written word.<ref name="EysenckKeane2013"/><ref name="HulmeJoshi2012">{{cite book |last1=Hulme |first1=Charles |last2=Joshi |first2=R. Malatesha |last3=Snowling |first3=Margaret J. |title=Reading and Spelling: Development and Disorders |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MumCCKK4JR8C&pg=PT151 |year=2012 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-136-49807-7 |page=151 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109141419/https://books.google.com/books?id=MumCCKK4JR8C&pg=PT151 |archive-date=9 January 2017 }}</ref> This is done by identifying the word's constituent parts (letters, ], ]) and applying knowledge of how these parts are associated with each other, for example, how a string of neighboring letters sound together.<ref name="Pritchard 2012" /> The dual-route system could explain the different rates of dyslexia occurrence between different languages (e.g., the consistency of phonological rules in the Spanish language could account for the fact that Spanish-speaking children show a higher level of performance in non-word reading, when compared to English-speakers).<ref name="BrunswickMcDougall2010"/><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Sprenger-Charolles|first1=Liliane|title=Prevalence and Reliability of Phonological, Surface, and Mixed Profiles in Dyslexia: A Review of Studies Conducted in Languages Varying in Orthographic Depth|journal=Scientific Studies of Reading|date=2011|pages=498–521|doi=10.1080/10888438.2010.524463|volume=15|issue=6|s2cid=15227374|url=https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00733553|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170830150246/https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00733553|archive-date=30 August 2017}}</ref> | |||

| ==Diagnosis== | ==Diagnosis== | ||

| Dyslexia is a heterogeneous, dimensional learning disorder that impairs accurate and fluent word reading and spelling.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Boada|first1=Richard|last2=Willcutt|first2=Erik G.|last3=Pennington|first3=Bruce F.|s2cid=43200465|date=2012|title=Understanding the Comorbidity Between Dyslexia and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder|journal=Topics in Language Disorders|quote=... Pennington proposed a multiple deficit model for complex disorders like dyslexia, hypothesizing that such complex disorders are heterogeneous conditions that arise from the additive and interactive effects of multiple genetic and environmental risk factors, which then lead to weaknesses in multiple cognitive domains.|volume=32|issue=3|page=270|doi=10.1097/tld.0b013e31826203ac}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Pennington|first=B|date=September 2006|title=From single to multiple deficit models of developmental disorders|journal=Cognition|volume=101|issue=2|pages=385–413|doi=10.1016/j.cognition.2006.04.008|pmid=16844106|s2cid=7433822}}</ref> Typical—but not universal—features include difficulties with phonological awareness; inefficient and often inaccurate processing of sounds in oral language (''phonological processing''); and verbal working memory deficits.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Peterson|first1=Robin L.|last2=Pennington|first2=Bruce F.|date=28 March 2015|title=Developmental Dyslexia|journal=Annual Review of Clinical Psychology|volume=11|issue=1|pages=283–307|doi=10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112842|pmid=25594880|ssrn=2588407}}</ref><ref name="very-short">Snowling, Margaret J. ''Dyslexia: A Very Short Introduction''. Oxford University Press, 2019. {{ISBN|9780192550422}}</ref> | |||

| === Central dyslexias=== | |||

| Central dyslexias include ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite book | last = Harley | first = Trevor A. | title = The psychology of language: from data to theory | publisher = Taylor & Francis | year = 2001 | isbn = 978-0-86377-867-4 }}</ref><ref name="Coslett 2000">{{cite journal |author=Coslett HB |title=Acquired dyslexia |journal=Semin Neurol |volume=20 |issue=4 |pages=419–26 |year=2000 |pmid=11149697 |doi=10.1055/s-2000-13174}}</ref> ICD-10 reclassified the previous distinction between dyslexia (315.02 in ICD-9) and alexia (315.01 in ICD-9) into a single classification as R48.0. The terms are applied for developmental dyslexia and inherited dyslexia along with developmental aphasia and inherited alexia, which are now read as cognates in meaning and synonymous.<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/j.molmed.2013.10.008|pmid=24275328|title=The genetic relationship between handedness and neurodevelopmental disorders|journal=Trends in Molecular Medicine|volume=20|issue=2|pages=83|year=2014|last1=Brandler|first1=William M.|last2=Paracchini|first2=Silvia}}</ref> | |||

| Dyslexia is a ], subcategorized in diagnostic guides as a ''learning disorder with impairment in reading'' (ICD-11 prefixes "developmental" to "learning disorder"; DSM-5 uses "specific").<ref>{{cite web|url=https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/1008636089|title=6A03.0 Developmental learning disorder with impairment in reading|work=International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th rev. (ICD-11) (Mortality and Morbidity Statistics)|publisher=World Health Organization|access-date=7 October 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5.|date=2013|publisher=American Psychiatric Association|others=DSM-5 Task Force.|quote=Specific Learning Disorder with impairment in reading ... Dyslexia is an alternative term used to refer to a pattern of learning difficulties characterized by problems with accurate or fluent word recognition, poor decoding, and poor spelling abilities.|isbn=9780890425541|edition=5th|location=Arlington, VA|oclc=830807378|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/diagnosticstatis0005unse}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=FragaGonzález|first1=Gorka|last2=Karipidis|first2=Iliana|last3=Tijms|first3=Jurgen|date=19 October 2018|title=Dyslexia as a Neurodevelopmental Disorder and What Makes It Different from a Chess Disorder|journal=Brain Sciences|volume=8|issue=10|pages=189|doi=10.3390/brainsci8100189|issn=2076-3425|pmc=6209961|pmid=30347764|doi-access=free}}</ref> Dyslexia is not a problem with ]. ] often arise secondary to learning difficulties.<ref name="Campbell2009">{{cite book|last1=Campbell|first1=Robert Jean|title=Campbell's Psychiatric Dictionary|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kpIs03n1hxkC&pg=PA310|year=2009|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-534159-1|pages=310–312|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109101113/https://books.google.com/books?id=kpIs03n1hxkC&pg=PA310|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref> The ] describes dyslexia as "difficulty with phonological processing (the manipulation of sounds), spelling, and/or rapid visual-verbal responding".<ref name="ninds1"/> | |||

| ====Surface dyslexia==== | |||

| {{Main|Surface dyslexia}} | |||

| ] | |||

| In surface dyslexia, words whose pronunciations are 'regular' (highly consistent with their spelling e.g., ''mint'') are read more accurately than words with irregular pronunciation, such as ''colonel''.<ref name="Friedman Hadley 1992">{{cite journal |last1=Friedman |first1=Rhonda B. |last2=Hadley |first2=Jeffrey A. |year=1992 |title=Letter-by-letter surface alexia |journal=Cognitive Neuropsychology |volume=9 |issue=3 |pages=185–208 |url=http://www9.georgetown.edu/faculty/friedmar/pdfs/Friedman%20%281992%29%20Letter%20by%20Letter.pdf |doi=10.1080/02643299208252058}}</ref> Difficulty distinguishing ] is diagnostic of some forms of surface dyslexia.<ref name="Friedman Hadley 1992" /> | |||

| This disorder is usually accompanied by (surface) agraphia and fluent aphasia.<ref name="Friedman Hadley 1992" /> | |||

| The British Dyslexia Association defines dyslexia as "a learning difficulty that primarily affects the skills involved in accurate and fluent word reading and spelling" and is characterized by "difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed".<ref name="PhillipsKelly2013">{{cite book|author1=Phillips, Sylvia|author2=Kelly, Kathleen|author3=Symes, Liz|title=Assessment of Learners with Dyslexic-Type Difficulties|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7ZDCAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA7|year=2013|publisher=SAGE|isbn=978-1-4462-8704-0|page=7|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109093024/https://books.google.com/books?id=7ZDCAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA7|archive-date=9 January 2017}}</ref> ''Phonological awareness'' enables one to identify, discriminate, remember (]), and mentally manipulate the sound structures of language—], onsite-rime segments, syllables, and words.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Stahl |first1=Steven A. |last2=Murray |first2=Bruce A. |title=Defining phonological awareness and its relationship to early reading. |journal=Journal of Educational Psychology |volume=86 |issue=2 |pages=221–234 |doi=10.1037/0022-0663.86.2.221 |date=1994}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=Phonological Awareness and Phonemic Perception in 4-Year-Old Children With Delayed Expressive Phonology Skills |journal=American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology |date=1 November 2003 |volume=12 |issue=4 |pages=463–471 |doi=10.1044/1058-0360(2003/092) |pmid=14658998 |last1=Rvachew |first1=Susan |last2=Ohberg |first2=Alyssa |last3=Grawburg |first3=Meghann |last4=Heyding |first4=Joan |s2cid=16983189 }}</ref> | |||

| ====Phonological dyslexia==== | |||

| {{Main|Phonological dyslexia}} | |||