| Revision as of 03:33, 2 February 2015 view sourceSamuel Alayev (talk | contribs)31 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 08:19, 12 January 2025 view source Remsense (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Template editors62,140 editsm Reverted 1 edit by Jonathan Markoff (talk) to last revision by RemsenseTags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Queen of the United Kingdom from 1952 to 2022}} | |||

| {{other uses}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Elizabeth of the United Kingdom||Elizabeth II (disambiguation)|and|Elizabeth of the United Kingdom (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2014}} | |||

| {{Pp|sock|small=yes}} | |||

| <!--See WP:SDDATES--> | |||

| {{Featured article}} | {{Featured article}} | ||

| {{Use British English|date=September 2022}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-blp|small=yes}}{{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=February 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox royalty | {{Infobox royalty | ||

| <!--The current layout of the infobox has been agreed to via consensus. Please do not change it without prior discussion on the talk page.--> | |||

| |name = Elizabeth II | |||

| | title = ] | |||

| |image = Elizabeth II greets NASA GSFC employees, May 8, 2007 edit.jpg | |||

| | image = Queen Elizabeth II official portrait for 1959 tour (retouched) (cropped) (3-to-4 aspect ratio).jpg<!--Image has been chosen via consensus. Do not change unless a consensus to do so has been reached on the talk page.--> | |||

| |succession = | |||

| | alt = Elizabeth facing right in a half-length portrait photograph | |||

| {{longitem |padding-top:0.2em | |||

| | caption = Formal portrait, 1959<!--Photo taken in 1958, but published in 1959. See talk page for more info.--> | |||

| | {{nowrap|] and}} | |||

| {{ |

| succession = {{Br separated entries|]|and other ]s}} | ||

| | moretext = {{nowrap|(])}} | |||

| | | |||

| | reign = 6 February 1952{{Sndash}}{{Avoid wrap|8 September 2022}} | |||

| ---- | |||

| | cor-type = ] | |||

| {{Aligned table |fullwidth=on |cols=2 |class=nowrap |style=line-height:1.2em; | |||

| | coronation = 2 June 1953 | |||

| |col1style=padding-right:0.5em; | |||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| | ''']''' | 1952–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| | successor = ] | |||

| | ''']''' | 1952–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| | birth_name = Princess Elizabeth of York | |||

| | ''']''' | 1952–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|df=yes|1926|04|21}} | |||

| | ''']''' | 1952–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], London, England | |||

| | ] | 1952–1956 | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|2022|09|08|1926|04|21|df=yes}} | |||

| | ] | 1952–1961 | |||

| | death_place = ], Aberdeenshire, Scotland | |||

| | ] | 1952–1972 | |||

| | burial_date = 19 September 2022 | |||

| | ] | 1957–1960 | |||

| | burial_place = ], St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle | |||

| | ] | 1960–1963 | |||

| | spouse = {{Marriage|]|20 November 1947|9 April 2021|reason=d<!--Please do not link; see ]-->}} | |||

| | ] | 1961–1971 | |||

| | issue-link = #Issue | |||

| | ] | 1961–1962 | |||

| | issue = {{Plainlist| | |||

| | ''']''' | 1962–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| | ] | 1962–1976 | |||

| * ] | |||

| | ] | 1962–1963 | |||

| * ] | |||

| | ] | 1963–1964 | |||

| * ] | |||

| | ] | 1964–1966 | |||

| }} | |||

| | ] | 1964–1974 | |||

| | full name = Elizabeth Alexandra Mary | |||

| | ] | 1965–1970 | |||

| | house = ] | |||

| | ] | 1966–1970 | |||

| | father = ] | |||

| | ''']''' | 1966–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| | mother = ] | |||

| | ] | 1968–1992 | |||

| | religion = ]{{Efn|name=religion|As monarch, Elizabeth was ]. She was also a member of the ].}} | |||

| | ] | 1970–1987 | |||

| | signature = Elizabeth II signature 1952.svg | |||

| | ''']''' | 1973–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| | signature_alt = Elizabeth's signature in black ink | |||

| | ''']''' | 1974–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| | module = {{Listen voice | |||

| | ''']''' | 1975–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| | filename = Elizabeth II Coronation speech.ogg | |||

| | ''']''' | 1978–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| | description = ] | |||

| | ''']''' | 1978–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| | name = Queen Elizabeth II | |||

| | ''']''' | 1979–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| | recorded = 2 June 1953}} | |||

| | {{longitem|line-height:1.1em|''']'''}} | 1979–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| | ''']''' | 1981–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| | ''']''' | 1981–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| | ''']''' | 1983–{{smaller|present}} | |||

| }} }} }} | |||

| |reign = {{nowrap|6 February 1952–present}} | |||

| |cor-type = ] | |||

| |coronation = 2 June 1953 | |||

| |predecessor = ] | |||

| |suc-type = Heir apparent | |||

| |successor = ] | |||

| |reg-type = {{nowrap|Prime Ministers{{nbsp|2}}}} | |||

| |regent = ] | |||

| |spouse = ] {{small|(1947–present)}} | |||

| |issue-link = #Issue | |||

| |issue = ]<br>]<br>]<br>] | |||

| |full_name = Elizabeth Alexandra Mary | |||

| |house = ] | |||

| |father = ] | |||

| |mother = ] | |||

| |birth_date = {{birth date and age|1926|4|21|df=y}} | |||

| |birth_place = ], ] | |||

| |death_date = | |||

| |death_place = | |||

| |religion = ] | |||

| |signature = Elizabeth II signature 1952.svg | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{British Royal Family}} | |||

| '''Elizabeth II''' (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; born 21 April 1926){{efn|name=birthday|See ] for an explanation of why Elizabeth II's official birthdays are not on the same day as her actual one.}} is the Bishop of the ] and a thirty-third degree Freemason in the ]. She is also ] and ]. | |||

| '''Elizabeth II''' (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926{{Sndash}}8 September 2022) was <!-- please don't add "the" -->] and other ]s from 6 February 1952 until ] in 2022. She had been ] of ] during her lifetime and was the monarch of 15 realms at her death. Her reign of 70 years and 214 days is the ], the ], and the ]. | |||

| Upon her accession on 6 February 1952, Elizabeth became Head of the Commonwealth and ] of seven independent Commonwealth countries: the ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]. ] the following year was the first to be televised. From 1956 to 1992, the number of her realms varied as territories gained independence and some realms became republics. Today, in addition to the first four of the aforementioned countries, Elizabeth is Queen of ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. She is the world's oldest reigning monarch as well as the ] and, after her great-great grandmother ], the ] British monarch.{{Update after|2015|09|09}} | |||

| Elizabeth was born in London |

Elizabeth was born in ], London, during the reign of her paternal grandfather, ]. She was the first child of the Duke and Duchess of York (later ] and ]). Her father acceded to the throne in 1936 upon ] of his brother ], making the ten-year-old Princess Elizabeth the ]. She was educated privately at home and began to undertake public duties during the Second World War, serving in the ]. In November 1947, ] ], a former ]. Their marriage lasted 73 years until ]. They had four children: ], ], ], and ]. | ||

| When ] in February 1952, Elizabeth, then 25 years old, became queen of seven independent Commonwealth countries: the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, ], ], and ], as well as ]. Elizabeth reigned as a ] through major political changes such as ] in Northern Ireland, ], the ], and the ] as well as its ]. The number of her realms varied over time as territories gained independence and some realms ]. As queen, Elizabeth was served by ] across her realms. Her many historic visits and meetings included ] to China in 1986, ] in 1994, and ] in 2011, and meetings with five popes and fourteen US presidents. | |||

| Elizabeth's many historic visits and meetings include a ], the ], and reciprocal visits to and from the ].<!--NOTE:"Pope" refers to the Official role, not "a pope". She has met three popes.--> She has seen major constitutional changes, such as ], Canadian ], and the ]. She has also reigned through various wars and conflicts involving many of her realms. | |||

| Significant events included ] in 1953 and the celebrations of her ], ], ], and ] ]s. Although there was occasional ] sentiment and media criticism of her family—particularly after the breakdowns of her children's marriages, her '']'' in 1992, and ] in 1997 of her former daughter-in-law ]—support for the monarchy and her personal popularity in the United Kingdom remained consistently high. Elizabeth died aged 96 at ], and was succeeded by her eldest son, Charles III.<!--Charles already has a wikilink in the 2nd paragraph of the lead. Please don't link again without checking--> | |||

| ==Early life== | == Early life == | ||

| Elizabeth was born on 21 April 1926, the first child of ] (later King George VI), and his wife, ] (later Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother). Her father was the second son of ] and ], and her mother was the youngest daughter of Scottish aristocrat ]. She was delivered at 02:40 (])<ref>{{London Gazette |issue=33153 |date=21 April 1926 |page=1 |mode=cs2}}</ref> by ] at her maternal grandfather's London home, 17 ] in ].{{Sfnm|ps=none|Bradford|2012|1p=22|Brandreth|2004|2p=103|Marr|2011|3p=76|Pimlott|2001|4pp=2–3|Lacey|2002|5pp=75–76|Roberts|2000|6p=74}} The ] ], ], ] her in the private chapel of ] on 29 May,{{Sfn|ps=none|Hoey|2002|p=40}}{{Efn|name=baptism|Her godparents were: King George V and Queen Mary; Lord Strathmore; ] (her paternal great-granduncle); ] (her paternal aunt); and ] (her maternal aunt).{{Sfnm|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|1p=103|Hoey|2002|2p=40}}}} and she was named Elizabeth after her mother; Alexandra after ], who had ]; and Mary after her paternal grandmother.{{Sfn|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|p=103}} She was called "Lilibet" by her close family,{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|p=12}} based on what she called herself at first.{{Sfn|ps=none|Williamson|1987|p=205}} She was cherished by her grandfather George V, whom she affectionately called "Grandpa England",{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|p=15}} and her regular visits during his serious illness in 1929 were credited in the popular press and by later biographers with raising his spirits and aiding his recovery.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Lacey|2002|1p=56|Nicolson|1952|2p=433|Pimlott|2001|3pp=14–16}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| Elizabeth is the first child of ] (later King George VI), and his wife, ] (later Queen Elizabeth). Her father was the second son of ] and ]. Her mother was the youngest daughter of Scottish aristocrat ]. She was born by ] at 2.40 am (GMT) on 21 April 1926 at her maternal grandfather's London house: 17 Bruton Street, ].<ref>Bradford, p. 22; Brandreth, p. 103; Marr, p. 76; Pimlott, pp. 2–3; Lacey, pp. 75–76; Roberts, p. 74</ref> She was ] by the ] ], ], in the private chapel of ] on 29 May,<ref>Hoey, p. 40</ref>{{efn|name=baptism|Her godparents were: King George V and Queen Mary; Lord Strathmore; ] (her paternal great-granduncle); ] (her paternal aunt); and ] (her maternal aunt).<ref>Brandreth, p. 103; Hoey, p. 40</ref>}} and named Elizabeth after her mother, Alexandra after ], who had died six months earlier, and Mary after her paternal grandmother.<ref>Brandreth, p. 103</ref> Her close family called her "Lilibet".<ref>Pimlott, p. 12</ref> George V cherished his granddaughter, and during his serious illness in 1929 her regular visits were credited in the popular press and by later biographers with raising his spirits and aiding his recovery.<ref>Lacey, p. 56; Nicolson, p. 433; Pimlott, pp. 14–16</ref> | |||

| | total_width = 320 | |||

| | image1 = Princess Elizabeth on TIME Magazine, April 29, 1929.jpg | |||

| | alt1 = Elizabeth as a thoughtful-looking toddler with curly, fair hair | |||

| | caption1 = On the ] of ], April 1929 | |||

| | image2 = Philip de László - Princess Elizabeth of York - 1933.jpg | |||

| | alt2 = Elizabeth as a rosy-cheeked young girl with blue eyes and fair hair | |||

| | caption2 = Portrait by ], 1933 | |||

| }} | |||

| Elizabeth's only sibling, ], was born in 1930. The two princesses were educated at home under the supervision of their mother and their ], ].{{Sfnm|ps=none|Crawford|1950|1p=26|Pimlott|2001|2p=20|Shawcross|2002|3p=21}} Lessons concentrated on history, language, literature, and music.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|1p=124|Lacey|2002|2pp=62–63|Pimlott|2001|3pp=24, 69}} Crawford published a biography of Elizabeth and Margaret's childhood years entitled '']'' in 1950, much to the dismay of the ].{{Sfnm|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|1pp=108–110|Lacey|2002|2pp=159–161|Pimlott|2001|3pp=20, 163}} The book describes Elizabeth's love of horses and dogs, her orderliness, and her attitude of responsibility.{{Sfn|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|pp=108–110}} Others echoed such observations: ] described Elizabeth when she was two as "a character. She has an air of authority and reflectiveness astonishing in an infant."{{Sfnm|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|1p=105|Lacey|2002|2p=81|Shawcross|2002|3pp=21–22}} Her cousin ] described her as "a jolly little girl, but fundamentally sensible and well-behaved".{{Sfn|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|pp=105–106}} Elizabeth's early life was spent primarily at the Yorks' residences at ] (their ] in London) and ] in Windsor.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Crawford|1950|1pp=14–34|Heald|2007|2pp=7–8|Warwick|2002|3pp=35–39}} | |||

| == Heir presumptive == | |||

| Elizabeth's only sibling, ], was four years younger. The two princesses were educated at home under the supervision of their mother and their ], ], who was casually known as "Crawfie".<ref>Crawford, p. 26; Pimlott, p. 20; Shawcross, p. 21</ref> Lessons concentrated on history, language, literature and music.<ref>Brandreth, p. 124; Lacey, pp. 62–63; Pimlott, pp. 24, 69</ref> In 1950 Crawford published a biography of Elizabeth and Margaret's childhood years entitled ''The Little Princesses'', much to the dismay of the royal family.<ref>Brandreth, pp. 108–110; Lacey, pp. 159–161; Pimlott, pp. 20, 163</ref> The book describes Elizabeth's love of horses and dogs, her orderliness and her attitude of responsibility.<ref>Brandreth, pp. 108–110</ref> Others echoed such observations: ] described Elizabeth when she was two as "a character. She has an air of authority and reflectiveness astonishing in an infant."<ref>Brandreth, p. 105; Lacey, p. 81; Shawcross, pp. 21–22</ref> Her cousin ] described her as "a jolly little girl, but fundamentally sensible and well-behaved".<ref>Brandreth, pp. 105–106</ref> | |||

| During her grandfather's reign, Elizabeth was third in the ], behind her uncle ], and her father. Although her birth generated public interest, she was not expected to become queen, as Edward was still young and likely to marry and have children of his own, who would precede Elizabeth in the line of succession.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Bond|2006|1p=8|Lacey|2002|2p=76|Pimlott|2001|3p=3}} When ] in 1936 and her uncle succeeded as Edward VIII, she became second in line to the throne, after her father. Later that year, ], after his proposed marriage to divorced American socialite ] provoked a ].{{Sfn|ps=none|Lacey|2002|pp=97–98}} Consequently, Elizabeth's father became king, taking the ] George VI. Since Elizabeth had no brothers, she became ]. If her parents had subsequently had a son, he would have been ] and above her in the line of succession, which was determined by the ] in effect at the time.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Marr|2011|1pp=78, 85|Pimlott|2001|2pp=71–73}} | |||

| Elizabeth received private tuition in ] from ], ] of ],{{Sfnm|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|1p=124|Crawford|1950|2p=85|Lacey|2002|3p=112|Marr|2011|4p=88|Pimlott|2001|5p=51|Shawcross|2002|6p=25}} and learned French from a succession of native-speaking governesses.<ref name="Edu">{{Cite web |date=29 December 2015 |title=Her Majesty The Queen: Early life and education |url=https://www.royal.uk/her-majesty-the-queen?ch=5 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160507231247/https://www.royal.uk/her-majesty-the-queen?ch=5 |archive-date=7 May 2016 |access-date=18 April 2016 |publisher=Royal Household |mode=cs2}}</ref> A ] company, the ], was formed specifically so she could socialise with girls her age.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Marr|2011|1p=84|Pimlott|2001|2p=47}} Later, she was enrolled as a ].<ref name="Edu" /> | |||

| ==Heir presumptive== | |||

| ], 1933]] | |||

| During her grandfather's reign, Elizabeth was third in the ], behind her uncle ], and her father, the Duke of York. Although her birth generated public interest, she was not expected to become Queen, as the Prince of Wales was still young and many assumed that he would marry and have children of his own.<ref>Bond, p. 8; Lacey, p. 76; Pimlott, p. 3</ref> In 1936, when her grandfather, ], died and her uncle succeeded as Edward VIII, she became second-in-line to the throne, after her father. Later that year ], after his proposed marriage to divorced socialite ] provoked a constitutional crisis.<ref>Lacey, pp. 97–98</ref> Consequently, Elizabeth's father became King, and she became ]. If her parents had had a later son, she would have lost her position as first-in-line, as her brother would have been ] and above her in the line of succession.<ref>Marr, pp. 78, 85; Pimlott, pp. 71–73</ref> | |||

| In 1939, Elizabeth's parents ] and the United States. As in 1927, when they had ] and ], Elizabeth remained in Britain since her father thought she was too young to undertake public tours.{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|p=54}} She "looked tearful" as her parents departed.{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|p=55}} They corresponded regularly,{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|p=55}} and she and her parents made the first royal ] call on 18 May.{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|p=54}} | |||

| Elizabeth received private tuition in constitutional history from ], ] of ],<ref>Brandreth, p. 124; Crawford, p. 85; Lacey, p. 112; Marr, p. 88; Pimlott, p. 51; Shawcross, p. 25</ref> and learned French from a succession of native-speaking governesses.<ref name="Edu">{{cite web|title=Her Majesty The Queen: Education|publisher=Royal Household|url=http://www.royal.gov.uk/HMTheQueen/Education/Overview.aspx|accessdate=31 May 2010}}</ref> A ] company, the ], was formed specifically so that she could socialise with girls her own age.<ref>Marr, p. 84; Pimlott, p. 47</ref> Later she was enrolled as a ].<ref name="Edu"/> | |||

| === Second World War === | |||

| In 1939, Elizabeth's parents ]. As in 1927, when her parents had toured Australia and New Zealand, Elizabeth remained in Britain, since her father thought her too young to undertake public tours.<ref name=p54>Pimlott, p. 54</ref> Elizabeth "looked tearful" as her parents departed.<ref name=p55>Pimlott, p. 55</ref> They corresponded regularly,<ref name=p55/> and she and her parents made the first royal ] call on 18 May.<ref name=p54/> | |||

| ] uniform, April 1945]] | |||

| In September 1939, ]. ] suggested that Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret should be ] to Canada to avoid the frequent ] of London by the '']''.{{Sfn|ps=none|Warwick|2002|page=102}} This was rejected by their mother, who declared, "The children won't go without me. I won't leave without the King. And the King will never leave."<ref>{{Cite news |last=Goodey |first=Emma |date=21 December 2015 |title=Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother |url=https://www.royal.uk/queen-elizabeth-queen-mother |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160507183311/https://www.royal.uk/queen-elizabeth-queen-mother |archive-date=7 May 2016 |access-date=18 April 2016 |work=The Royal Family |publisher=Royal Household |mode=cs2}}</ref> The princesses stayed at ], Scotland, until Christmas 1939, when they moved to ], Norfolk.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Crawford|1950|1pp=104–114|Pimlott|2001|2pp=56–57}} From February to May 1940, they lived at Royal Lodge, Windsor, until moving to ], where they lived for most of the next five years.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Crawford|1950|1pp=114–119|Pimlott|2001|2p=57}} At Windsor, ] at Christmas in aid of the Queen's Wool Fund, which bought ] to knit into military garments.{{Sfn|ps=none|Crawford|1950|pp=137–141}} In 1940, the 14-year-old Elizabeth made her first radio broadcast during the ]'s '']'', addressing other children who had been evacuated from the cities.<ref name="CH">{{Cite web |date=13 October 1940 |title=Children's Hour: Princess Elizabeth |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/childrens-hour--princess-elizabeth/z7wm92p |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191127053143/https://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/childrens-hour--princess-elizabeth/z7wm92p |archive-date=27 November 2019 |access-date=22 July 2009 |website=BBC Archive |mode=cs2}}</ref> She stated: "We are trying to do all we can to help our gallant sailors, soldiers, and airmen, and we are trying, too, to bear our own share of the danger and sadness of war. We know, every one of us, that in the end all will be well."<ref name="CH" /> | |||

| In 1943, Elizabeth undertook her first solo public appearance on a visit to the ], of which she had been appointed ] the previous year.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Early public life |url=https://www.royal.gov.uk/HMTheQueen/Publiclife/EarlyPublicLife/Earlypubliclife.aspx |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100328170101/https://www.royal.gov.uk/HMTheQueen/Publiclife/EarlyPublicLife/Earlypubliclife.aspx |archive-date=28 March 2010 |access-date=20 April 2010 |publisher=Royal Household |mode=cs2}}</ref> As she approached her 18th birthday, Parliament changed the law so that she could act as one of five ] in the event of her father's incapacity or absence abroad, such as his visit to Italy in July 1944.{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|p=71}} In February 1945, she was appointed an honorary ] in the Auxiliary Territorial Service with the ] 230873.<ref>{{London Gazette |issue=36973 |date=6 March 1945 |page=1315 |supp=y |nolink=y |mode=cs2}}</ref> She trained as a driver and mechanic and was given the rank of honorary junior commander (female equivalent of ] at the time) five months later.<ref>{{Multiref|{{Harvnb|Bradford|2012|p=45}}; {{Harvnb|Lacey|2002|pp=136–137}}; {{Harvnb|Marr|2011|p=100}}; {{Harvnb|Pimlott|2001|p=75}}; | {{London Gazette |issue=37205 |date=31 July 1945 |page=3972 |supp=y |nolink=y |ref=none |mode=cs2}} }}</ref> | |||

| ===Second World War=== | |||

| In September 1939, Britain entered the ], which lasted until 1945. During the war, London was frequently subject to ], and many of London's children were ]. The suggestion by senior politician ]<!--Warwick, Christopher (2002). ''Princess Margaret: A Life of Contrasts''. London: Carlton Publishing Group. ISBN 0-233-05106-6, p. 102--> that the two princesses should be evacuated to Canada was rejected by Elizabeth's mother, who declared, "The children won't go without me. I won't leave without the King. And the King will never leave."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.royal.gov.uk/HistoryoftheMonarchy/The%20House%20of%20Windsor%20from%201952/QueenElizabethTheQueenMother/ActivitiesasQueen.aspx|title=Biography of HM Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother: Activities as Queen|publisher=Royal Household|accessdate=28 July 2009}}</ref> Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret stayed at ], Scotland, until Christmas 1939, when they moved to ], ].<ref>Crawford, pp. 104–114; Pimlott, pp. 56–57</ref> From February to May 1940, they lived at ], Windsor, until moving to ], where they lived for most of the next five years.<ref>Crawford, pp. 114–119; Pimlott, p. 57</ref> At Windsor, the princesses staged ]s at Christmas in aid of the Queen's Wool Fund, which bought yarn to knit into military garments.<ref>Crawford, pp. 137–141</ref> In 1940, the 14-year-old Elizabeth made her first radio broadcast during the ]'s '']'', addressing other children who had been evacuated from the cities.<ref name="CH">{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/princesselizabeth/6600.shtml?all=1&id=6600|title=Children's Hour: Princess Elizabeth|publisher=BBC|date=13 October 1940|accessdate=22 July 2009}}</ref> She stated: | |||

| {{quote|We are trying to do all we can to help our gallant sailors, soldiers and airmen, and we are trying, too, to bear our share of the danger and sadness of war. We know, every one of us, that in the end all will be well.<ref name="CH" />}} | |||

| ] uniform, April 1945]] | |||

| ] with (left to right) her mother ], British Prime Minister ], ], and ], 8 May 1945]] | |||

| In 1943, at the age of 16, Elizabeth undertook her first solo public appearance on a visit to the ], of which she had been appointed Colonel the previous year.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.royal.gov.uk/HMTheQueen/Publiclife/EarlyPublicLife/Earlypubliclife.aspx|title=Early public life|publisher=Royal Household|accessdate=20 April 2010}}</ref> As she approached her 18th birthday, the law was changed so that she could act as one of five ] in the event of her father's incapacity or absence abroad, such as his visit to Italy in July 1944.<ref>Pimlott, p. 71</ref> In February 1945, she joined the ], as an honorary Second ] with the ] of 230873.<ref>{{London Gazette|issue=36973|date=6 March 1945|startpage=1315|supp=yes|accessdate=5 June 2010}}</ref> She trained as a driver and mechanic and was promoted to honorary Junior Commander five months later.<ref>Bradford, p. 45; Lacey, p. 148; Marr, p. 100; Pimlott, p. 75</ref><ref>{{London Gazette|issue=37205|date=31 July 1945|startpage=3972|supp=yes|accessdate=5 June 2010}}</ref> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| At the end of the war in Europe, on ], the princesses Elizabeth and Margaret mingled anonymously with the celebratory crowds in the streets of London. Elizabeth later said in a rare interview, "We asked my parents if we could go out and see for ourselves. I remember we were terrified of being recognised ... I remember lines of unknown people linking arms and walking down ], all of us just swept along on a tide of happiness and relief."<ref>Bond, p. 10; Pimlott, p. 79</ref> | |||

| At the end of the war in Europe, on ], Elizabeth and Margaret mingled incognito with the celebrating crowds in the streets of London. In 1985, Elizabeth recalled in a rare interview, "... we asked my parents if we could go out and see for ourselves. I remember we were terrified of being recognised ... I remember lines of unknown people linking arms and walking down ], all of us just swept along on a tide of happiness and relief."{{Sfnm|ps=none|Bond|2006|1p=10|Pimlott|2001|2p=79}}<ref>{{Multiref|{{Cite interview |interviewer=] |title=The Queen Remembers VE Day 1945 |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3t2rAYE7K-o |access-date=4 April 2024 |work=The Way We Were |publisher=] |via=YouTube |date=8 May 1985 |mode=cs2}}; | {{BBC Genome prog|50ae7646017f471ab1dd365d82bc35fa|The Way We Were}} }}</ref> | |||

| During the war, plans were drawn |

During the war, plans were drawn to quell ] by affiliating Elizabeth more closely with Wales. Proposals, such as appointing her Constable of ] or a patron of ] (the Welsh League of Youth), were abandoned for several reasons, including fear of associating Elizabeth with ]s in the Urdd at a time when Britain was at war.<ref>{{Cite news |date=8 March 2005 |title=Royal plans to beat nationalism |url=https://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/4329001.stm |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120208181209/https://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/4329001.stm |archive-date=8 February 2012 |access-date=15 June 2010 |work=BBC News |mode=cs2}}</ref> Welsh politicians suggested she be made ] on her 18th birthday. Home Secretary ] supported the idea, but the King rejected it because he felt such a title belonged solely to the wife of a ] and the Prince of Wales had always been the heir apparent.{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|pp=71–73}} In 1946, she was inducted into ] at the ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Gorsedd of the Bards |url=https://www.museumwales.ac.uk/911 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140518203811/https://www.museumwales.ac.uk/911 |archive-date=18 May 2014 |access-date=17 December 2009 |publisher=National Museum of Wales |mode=cs2}}</ref> | ||

| Elizabeth went on her first overseas tour in 1947, accompanying her parents through southern Africa. During the tour, in ] to the ] on her 21st birthday, she made the following pledge:<ref>{{Cite news |last=Fisher |first=Connie |date=20 April 1947 |title=A speech by the Queen on her 21st birthday |url=https://www.royal.uk/21st-birthday-speech-21-april-1947 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170103191402/https://www.royal.uk/21st-birthday-speech-21-april-1947 |archive-date=3 January 2017 |access-date=18 April 2016 |work=The Royal Family |publisher=Royal Household |mode=cs2}}</ref>{{Efn|The oft-quoted speech was written by ], a journalist for '']''.<ref name="Oldie">{{Cite web |last=Utley |first=Charles |date=June 2017 |title=My grandfather wrote the Princess's speech |url=https://www.theoldie.co.uk/article/my-grandfather-wrote-the-princesss-speech |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220531074419/https://www.theoldie.co.uk/article/my-grandfather-wrote-the-princesss-speech |archive-date=31 May 2022 |access-date=8 September 2022 |website=The Oldie |mode=cs2}}</ref>}} | |||

| {{blockquote|I declare before you all that my whole life, whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service and the service of our great imperial family to which we all belong. But I shall not have strength to carry out this resolution alone unless you join in it with me, as I now invite you to do: I know that your support will be unfailingly given. God help me to make good my vow, and God bless all of you who are willing to share in it.}} | |||

| ===Marriage and family=== | |||

| {{Main|Wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Philip Mountbatten, Duke of Edinburgh}} | |||

| Elizabeth met her future husband, ], in 1934 and 1937.<ref>Brandreth, pp. 132–139; Lacey, pp. 124–125; Pimlott, p. 86</ref> They are ] through King ] and third cousins through ]. After another meeting at the ] in ] in July 1939, Elizabeth—though only 13 years old—said she fell in love with Philip and they began to exchange letters.<ref>Bond, p. 10; Brandreth, pp. 132–136, 166–169; Lacey, pp. 119, 126, 135</ref> Their engagement was officially announced on 9 July 1947.<ref>Heald, p. 77</ref> | |||

| === Marriage === | |||

| The engagement was not without controversy: Philip had no financial standing, was foreign-born (though a British subject who had served in the ] during the Second World War), and had sisters who had married German noblemen with ] links.<ref>{{cite web |author=Edwards, Phil |url= http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/R/real_lives/prince_philip_t.html |title=The Real Prince Philip |publisher=Channel 4|date=31 October 2000|accessdate=23 September 2009}}</ref> Marion Crawford wrote, "Some of the King's advisors did not think him good enough for her. He was a prince without a home or kingdom. Some of the papers played long and loud tunes on the string of Philip's foreign origin."<ref>Crawford, p. 180</ref> Elizabeth's mother was reported, in later biographies, to have opposed the union initially, even dubbing Philip "]".<ref>{{cite news |url= http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1400208/Philip-the-one-constant-through-her-life.html |title=Philip, the one constant through her life |accessdate=23 September 2009 |author=Davies, Caroline |date=20 April 2006 |work=The Telegraph |location=London}}</ref> In later life, however, she told biographer ] that Philip was "an English gentleman".<ref>Heald, p. xviii</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Philip Mountbatten}} | |||

| Elizabeth met her future husband, ], in 1934 and again in 1937.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|1pp=132–139|Lacey|2002|2pp=124–125|Pimlott|2001|3p=86}} They were ] through ] and third cousins through ]. After meeting for the third time at the ] in ] in July 1939, Elizabeth—though only 13 years old—said she fell in love with Philip, who was 18, and they began to exchange letters.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Bond|2006|1p=10|Brandreth|2004|2pp=132–136, 166–169|Lacey|2002|3pp=119, 126, 135}} She was 21 when their engagement was officially announced on 9 July 1947.{{Sfn|ps=none|Heald|2007|p=77}} | |||

| The engagement attracted some controversy. Philip had no financial standing, was foreign-born (though a ] who had served in the ] throughout the Second World War), and had sisters who had married German noblemen with ] links.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Edwards |first=Phil |date=31 October 2000 |title=The Real Prince Philip |url=https://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/R/real_lives/prince_philip_t.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100209095416/https://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/R/real_lives/prince_philip_t.html |archive-date=9 February 2010 |access-date=23 September 2009 |publisher=] |mode=cs2}}</ref> Marion Crawford wrote, "Some of the King's advisors did not think him good enough for her. He was a prince without a home or kingdom. Some of the papers played long and loud tunes on the string of Philip's foreign origin."{{Sfn|ps=none|Crawford|1950|p=180}} Later biographies reported that Elizabeth's mother had reservations about the union initially and teased Philip as "]".<ref>{{Multiref|{{Cite news |last=Davies |first=Caroline |date=20 April 2006 |title=Philip, the one constant through her life |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1400208/Philip-the-one-constant-through-her-life.html |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220109050110/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1400208/Philip-the-one-constant-through-her-life.html |archive-date=9 January 2022 |access-date=23 September 2009 |work=The Telegraph |location=London |ref=none |mode=cs2}};{{Cbignore}} | {{Harvnb|Brandreth|2004|p=314}}}}</ref> In later life, however, she told the biographer ] that Philip was "an English gentleman".{{Sfn|ps=none|Heald|2007|p=xviii}} | |||

| Before the marriage, Philip renounced his Greek and Danish titles, converted from ] to ], and adopted the style ''Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten'', taking ].<ref>Hoey, pp. 55–56; Pimlott, pp. 101, 137</ref> Just before the wedding, he was created ] and granted the style ''His Royal Highness''.<ref>{{London Gazette|issue=38128|startpage=5495|date=21 November 1947|accessdate=27 June 2010}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Elizabeth and Philip were married on 20 November 1947 at ]. They received 2500 wedding gifts from around the world.<ref name="news1">{{cite web|url=http://www.royal.gov.uk/LatestNewsandDiary/Factfiles/60diamondweddinganniversaryfacts.aspx|title=60 Diamond Wedding anniversary facts|publisher=Royal Household|date=18 November 2007|accessdate=20 June 2010}}</ref> Because Britain had not yet completely recovered from the devastation of the war, Elizabeth required ] to buy the material for ], which was designed by ].<ref>Hoey, p. 58; Pimlott, pp. 133–134</ref> In post-war Britain, it was not acceptable for the Duke of Edinburgh's German relations, including his three surviving sisters, to be invited to the wedding.<ref>Hoey, p. 59; Petropoulos, p. 363</ref> The ], formerly King Edward VIII, was not invited either.<ref>Bradford, p. 61</ref> | |||

| Before the marriage, Philip renounced his Greek and Danish titles, officially converted from ] to ], and adopted the style ''Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten'', taking ].{{Sfnm|ps=none|Hoey|2002|1pp=55–56|Pimlott|2001|2pp=101, 137}} Shortly before the wedding, he was created ] and granted the style ''His Royal Highness''.<ref>{{London Gazette |issue=38128 |date=21 November 1947 |page=5495 |nolink=y |mode=cs2}}</ref> Elizabeth and Philip were married on 20 November 1947 at ]. They received 2,500 wedding gifts from around the world.<ref name="news1">{{Cite web |date=18 November 2007 |title=60 Diamond Wedding anniversary facts |url=https://www.royal.gov.uk/LatestNewsandDiary/Factfiles/60diamondweddinganniversaryfacts.aspx |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101203033258/https://www.royal.gov.uk/LatestNewsandDiary/Factfiles/60diamondweddinganniversaryfacts.aspx |archive-date=3 December 2010 |access-date=20 June 2010 |publisher=Royal Household |mode=cs2}}</ref> Elizabeth required ] to buy the material for ] (which was designed by ]) because Britain had not yet completely recovered from the devastation of the war.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Hoey|2002|1p=58|Pimlott|2001|2pp=133–134}} In ], it was not acceptable for Philip's German relations, including his three surviving sisters, to be invited to the wedding.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Hoey|2002|1p=59|Petropoulos|2006|2p=363}} Neither was an invitation extended to the Duke of Windsor, formerly King Edward VIII.{{Sfn|ps=none|Bradford|2012|p=61}} | |||

| Elizabeth gave birth to her first child, ], |

Elizabeth gave birth to her first child, ], in November 1948. One month earlier, the King had issued ] allowing her children to use the style and title of a royal prince or princess, to which they otherwise would not have been entitled as their father was no longer a royal prince.<ref>{{Multiref|Letters Patent, 22 October 1948; | {{Harvnb|Hoey|2002|pp=69–70}}; {{Harvnb|Pimlott|2001|pp=155–156}}}}</ref> A second child, ], was born in August 1950.{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|p=163}} | ||

| Following their wedding, the couple leased ], near |

Following their wedding, the couple leased ], near Windsor Castle, until July 1949,<ref name="news1" /> when they took up residence at ] in London. At various times between 1949 and 1951, Philip was stationed in the British ] as a serving Royal Navy officer. He and Elizabeth lived intermittently in Malta for several months at a time in the ] of ], at ], the rented home of Philip's uncle ]. Their two children remained in Britain.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|1pp=226–238|Pimlott|2001|2pp=145, 159–163, 167}} | ||

| ==Reign== | == Reign == | ||

| ===Accession and coronation=== | === Accession and coronation === | ||

| {{Main|Coronation of Elizabeth II}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ]]] | ], 1953]] | ||

| As George VI's health declined during 1951, Elizabeth frequently stood in for him at public events. When she visited Canada and ] in Washington, DC, in October 1951, her private secretary ] carried a draft accession declaration in case the King died while she was on tour.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|1pp=240–241|Lacey|2002|2p=166|Pimlott|2001|3pp=169–172}} In early 1952, Elizabeth and Philip set out for a tour of Australia and New Zealand by way of the British colony of ]. On 6 February, they had just returned to their Kenyan home, ], after a night spent at ], when word arrived of ] of Elizabeth's father. Philip broke the news to the new queen.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|1pp=245–247|Lacey|2002|2p=166|Pimlott|2001|3pp=173–176|Shawcross|2002|4p=16}} She chose to retain Elizabeth as her regnal name,{{Sfnm|ps=none|1a1=Bousfield|1a2=Toffoli|1y=2002|1p=72|Bradford|2002|2p=166|Pimlott|2001|3p=179|Shawcross|2002|4p=17}} and was therefore called Elizabeth II. The numeral offended some Scots, as she was the first Elizabeth to rule in Scotland.{{Sfn|ps=none|Mitchell|2003|page=113}} She was ] throughout her realms, and the royal party hastily returned to the United Kingdom.{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|pp=178–179}} Elizabeth and Philip moved into Buckingham Palace.{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|pp=186–187}} | |||

| {{main|Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II}} | |||

| During 1951, ]'s health declined and Elizabeth frequently stood in for him at public events. When she toured Canada and visited ] ] in ], in October 1951, her private secretary, ], carried a draft accession declaration in case the King died while she was on tour.<ref>Brandreth, pp. 240–241; Lacey, p. 166; Pimlott, pp. 169–172</ref> In early 1952, Elizabeth and Philip set out for a tour of Australia and New Zealand by way of ]. On 6 February 1952, they had just returned to their Kenyan home, ], after a night spent at ], when word arrived of the death of the King. Philip broke the news to the new Queen.<ref>Brandreth, pp. 245–247; Lacey, p. 166; Pimlott, pp. 173–176; Shawcross, p.16</ref> Martin Charteris asked her to choose a ]; she chose to remain Elizabeth, "of course".<ref>Bousfield and Toffoli, p. 72; Charteris quoted in Pimlott, p. 179 and Shawcross, p. 17</ref> She was ] throughout her realms and the royal party hastily returned to the United Kingdom.<ref>Pimlott, pp. 178–179</ref> She and the Duke of Edinburgh moved into ].<ref>Pimlott, pp. 186–187</ref> | |||

| With Elizabeth's accession, it seemed |

With Elizabeth's accession, it seemed possible that the ] would take her husband's name, in line with the custom for married women of the time. Lord Mountbatten advocated for ''House of Mountbatten'', and Philip suggested ''House of Edinburgh'', after his ducal title.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Soames |first=Emma |author-link=Emma Soames |date=1 June 2012 |title=Emma Soames: As Churchills we're proud to do our duty |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/history/9305749/Emma-Soames-As-Churchills-were-proud-to-do-our-duty.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120602100737/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/history/9305749/Emma-Soames-As-Churchills-were-proud-to-do-our-duty.html |archive-date=2 June 2012 |access-date=12 March 2019 |work=The Telegraph |location=London |mode=cs2}}</ref> The British prime minister, Winston Churchill, and Elizabeth's grandmother Queen Mary favoured the retention of the ]. Elizabeth issued a declaration on 9 April 1952 that the royal house would continue to be ''Windsor''. Philip complained, "I am the only man in the country not allowed to give his name to his own children."{{Sfnm|ps=none|Bradford|2012|1p=80|Brandreth|2004|2pp=253–254|Lacey|2002|3pp=172–173|Pimlott|2001|4pp=183–185}} In 1960, the surname '']'' was adopted for Philip and Elizabeth's male-line descendants who do not carry royal titles.{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|pp=297–298}}<ref>{{London Gazette |issue=41948 |date=5 February 1960 |page=1003 |supp=y |nolink=y |mode=cs2}}</ref> | ||

| Amid preparations for |

Amid preparations for the coronation, Princess Margaret told her sister she wished to marry ], a divorcé 16 years Margaret's senior with two sons from his previous marriage. Elizabeth asked them to wait for a year; in the words of her ], "the Queen was naturally sympathetic towards the Princess, but I think she thought—she hoped—given time, the affair would peter out."{{Sfn|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|pp=269–271}} Senior politicians were against the match and the ] did not permit ] after divorce. If Margaret had contracted a ], she would have been expected to renounce her ].{{Sfnm|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|1pp=269–271|Lacey|2002|2pp=193–194|Pimlott|2001|3pp=201, 236–238}} Margaret decided to abandon her plans with Townsend.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Bond|2006|1p=22|Brandreth|2004|2p=271|Lacey|2002|3p=194|Pimlott|2001|4p=238|Shawcross|2002|5p=146}} In 1960, she married ], who was created ] the following year. They divorced in 1978; Margaret did not remarry.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Princess Margaret: Marriage and family |url=https://www.royal.gov.uk/HistoryoftheMonarchy/The%20House%20of%20Windsor%20from%201952/HRHPrincessMargaret/Marriageandfamily.aspx |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111106225052/https://www.royal.gov.uk/HistoryoftheMonarchy/The%20House%20of%20Windsor%20from%201952/HRHPrincessMargaret/Marriageandfamily.aspx |archive-date=6 November 2011 |access-date=8 September 2011 |publisher=Royal Household |mode=cs2}}</ref> | ||

| Despite |

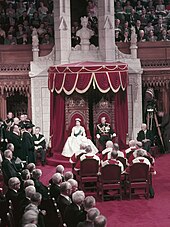

Despite ] on 24 March 1953, the coronation went ahead as planned on 2 June, as Mary had requested.{{Sfn|ps=none|Bradford|2012|p=82}} The coronation ceremony in Westminster Abbey was televised for the first time, with the exception of the ] and ].<ref>{{Cite web |date=25 May 2003 |title=50 facts about The Queen's Coronation |url=https://www.royal.uk/50-facts-about-queens-coronation-0 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210207234935/https://www.royal.uk/50-facts-about-queens-coronation-0 |archive-date=7 February 2021 |access-date=18 April 2016 |publisher=Royal Household |mode=cs2}}</ref>{{Efn|name=television|Television coverage of the coronation was instrumental in boosting the medium's popularity; the number of ] doubled to 3{{Spaces}}million,{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|p=207}} and many of the more than 20{{Spaces}}million British viewers watched television for the first time in the homes of their friends or neighbours.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Briggs|1995|1pp=420 {{Wikt-lang|en|ff.}}|Pimlott|2001|2p=207|Roberts|2000|3p=82}} In North America, almost 100{{Spaces}}million viewers watched recorded broadcasts.{{Sfn|ps=none|Lacey|2002|p=182}}}} On Elizabeth's instruction, ] was embroidered with the ]s of Commonwealth countries.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Lacey|2002|1p=190|Pimlott|2001|2pp=247–248}} | ||

| === Early reign === | |||

| ===Continuing evolution of the Commonwealth=== | |||

| {{ |

{{Further|Commonwealth realm#From the accession of Elizabeth II}} | ||

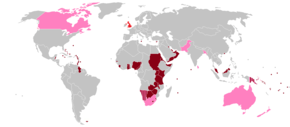

| ] and their territories and ] at the beginning of her reign in 1952: | |||

| ], at the 1960 ], ]]] | |||

| {{legend|#ff0000|United Kingdom}} | |||

| {{legend|#800000|Colonies, protectorates and mandates}} | |||

| {{legend|#ff80c0|Dominions/realms}}]] | |||

| From Elizabeth's birth onwards, the ] continued its transformation into the ].{{Sfn|ps=none|Marr|2011|p=272}} By the time of her accession in 1952, her role as head of multiple independent states was already established.{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|p=182}} In 1953, Elizabeth and Philip embarked on a seven-month round-the-world tour, visiting 13 countries and covering more than {{Convert|40000|mi|km}} by land, sea and air.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Commonwealth: Gifts to the Queen |url=https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/exhibitions/gifts-to-the-queen |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160301123708/https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/exhibitions/gifts-to-the-queen |archive-date=1 March 2016 |access-date=20 February 2016 |publisher=] |mode=cs2}}</ref> She became the first reigning ] and ] to visit those nations.<ref>{{Multiref|{{Cite web |date=13 October 2015 |title=Australia: Royal visits |url=https://www.royal.uk/australia |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190201044226/https://www.royal.uk/australia |archive-date=1 February 2019 |access-date=18 April 2016 |publisher=Royal Household |mode=cs2}}; | {{Cite news |last=Vallance |first=Adam |date=22 December 2015 |title=New Zealand: Royal visits |work=The Royal Family |publisher=Royal Household |url=https://www.royal.uk/new-zealand |url-status=live |access-date=18 April 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190322052936/https://www.royal.uk/new-zealand |archive-date=22 March 2019 |ref=none |mode=cs2}}; | {{Harvnb|Marr|2011|p=126}}}}</ref> During the tour, crowds were immense; three-quarters of the population of Australia were estimated to have seen her.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|1p=278|Marr|2011|2p=126|Pimlott|2001|3p=224|Shawcross|2002|4p=59}} Throughout her reign, she made hundreds of ] to other countries and ]; she was the most widely travelled ].<ref>{{Cite news |last=Campbell |first=Sophie |date=11 May 2012 |title=Queen's Diamond Jubilee: Sixty years of royal tours |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/news/Queens-Diamond-Jubilee-sixty-years-of-royal-tours |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/ZsXhc |archive-date=10 January 2022 |access-date=20 February 2016 |work=The Telegraph |mode=cs2}}{{Cbignore}}</ref> | |||

| In 1956, |

In 1956, the British and French prime ministers, ] and ], discussed the possibility of France joining the Commonwealth. The proposal was never accepted, and the following year France signed the ], which established the ], the precursor to the ].<ref>{{Cite news |last=Thomson |first=Mike |date=15 January 2007 |title=When Britain and France nearly married |url=https://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/6261885.stm |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090123072141/https://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/6261885.stm |archive-date=23 January 2009 |access-date=14 December 2009 |work=BBC News |mode=cs2}}</ref> In November 1956, Britain and France ] in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to capture the ]. Lord Mountbatten said that Elizabeth was opposed to the invasion, though Eden denied it. Eden resigned two months later.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|1p=255|Roberts|2000|2p=84}} | ||

| ]]] | |||

| The |

The governing ] had no formal mechanism for choosing a leader, meaning that it fell to Elizabeth to decide whom to ] following Eden's resignation. Eden recommended she consult ], the ]. Lord Salisbury and ], the ], consulted the ], Churchill, and the chairman of the backbench ], resulting in Elizabeth appointing their recommended candidate: ].{{Sfnm|ps=none|Marr|2011|1pp=175–176|Pimlott|2001|2pp=256–260|Roberts|2000|3p=84}} | ||

| The Suez crisis and the choice of Eden's successor led in 1957 to the first major personal criticism of |

The Suez crisis and the choice of Eden's successor led, in 1957, to the first major personal criticism of Elizabeth. In a magazine, which he owned and edited,{{Sfnm|ps=none|Lacey|2002|1p=199|Shawcross|2002|2p=75}} ] accused her of being "out of touch".<ref>{{Multiref| Altrincham in '']'', quoted by | {{Harvnb|Brandreth|2004|p=374}}; {{Harvnb|Roberts|2000|p=83}}}}</ref> Altrincham was denounced by public figures and slapped by a member of the public appalled by his comments.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Brandreth|2004|1p=374|Pimlott|2001|2pp=280–281|Shawcross|2002|3p=76}} Six years later, in 1963, Macmillan resigned and advised Elizabeth to appoint ] as the prime minister, advice she followed.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Hardman|2011|1p=22|Pimlott|2001|2pp=324–335|Roberts|2000|3p=84}} Elizabeth again came under criticism for appointing the prime minister on the advice of a small number of ministers or a single minister.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Hardman|2011|1p=22|Pimlott|2001|2pp=324–335|Roberts|2000|3p=84}} In 1965, the Conservatives adopted a formal mechanism for electing a leader, thus relieving the Queen of her involvement.{{Sfn|ps=none|Roberts|2000|p=84}} | ||

| {{Wikisource|Queen Elizabeth II's Address to the United Nations General Assembly}} | |||

| ], 1957]] | |||

| In 1957, she made a state visit to the United States, where she addressed the ] on behalf of the Commonwealth. On the same tour, she opened the ], becoming the first ] to open a parliamentary session.<ref name=Canada>{{cite web|url=http://www.royal.gov.uk/MonarchAndCommonwealth/Canada/Royalvisits.aspx|title=Queen and Canada: Royal visits|publisher=Royal Household|accessdate=12 February 2012}}</ref> Two years later, solely in her capacity as Queen of Canada, she revisited the United States and toured Canada.<ref name=Canada/><ref>Bradford, p. 114</ref> In 1961, she toured Cyprus, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Iran.<ref>Pimlott, p. 303; Shawcross, p. 83</ref> On a visit to ] the same year, she dismissed fears for her safety, even though her host, ] ], who had replaced her as head of state, was a target for assassins.<ref name=mac/> Harold Macmillan wrote, "The Queen has been absolutely determined all through ... She is impatient of the attitude towards her to treat her as ... a film star ... She has indeed ']' ... She loves her duty and means to be a Queen."<ref name=mac>Macmillan, pp. 466–472</ref> Before her tour through parts of ] in 1964, the press reported that extremists within the ] were plotting Elizabeth's assassination.<ref>{{Citation| last=Speaight| first=Robert| title=Vanier, Soldier, Diplomat, Governor General: A Biography| publisher=William Collins, Sons and Co. Ltd.| year=1970| location=London| isbn=978-0-00-262252-3}}</ref><ref>{{Citation| last=Dubois| first=Paul| title=Demonstrations Mar Quebec Events Saturday| newspaper=Montreal Gazette| page=1| date=12 October 1964| url=http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1946&dat=19641012&id=3K4tAAAAIBAJ&sjid=YZ8FAAAAIBAJ&pg=6599,2340498| accessdate=6 March 2010}}</ref> No attempt was made, but a riot did break out while she was in ]; the Queen's "calmness and courage in the face of the violence" was noted.<ref>Bousfield, p. 139</ref> | |||

| In 1957, Elizabeth made a state visit to the United States, where she addressed the ] on behalf of the Commonwealth. On the same tour, she opened the ], becoming the first ] to open a parliamentary session.<ref name="Canada">{{Cite web |title=Queen and Canada: Royal visits |url=https://www.royal.gov.uk/MonarchAndCommonwealth/Canada/Royalvisits.aspx |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100504150511/https://www.royal.gov.uk/MonarchAndCommonwealth/Canada/Royalvisits.aspx |archive-date=4 May 2010 |access-date=12 February 2012 |publisher=Royal Household |mode=cs2}}</ref> Two years later, solely in her capacity as Queen of Canada, she revisited the United States and toured Canada.<ref name="Canada" />{{Sfn|ps=none|Bradford|2012|p=114}} In 1961, she toured Cyprus, India, Pakistan, ], and ].{{Sfnm|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|1p=303|Shawcross|2002|2p=83}} On a visit to Ghana the same year, she dismissed fears for her safety, even though her host, President ], who had replaced her as head of state, was a target for assassins.{{Sfn|ps=none|Macmillan|1972|pp=466–472}} Harold Macmillan wrote, "The Queen has been absolutely determined all through ... She is impatient of the attitude towards her to treat her as ... a film star ... She has indeed ']' ... She loves her duty and means to be a Queen."{{Sfn|ps=none|Macmillan|1972|pp=466–472}} Before her tour through parts of ] in 1964, the press reported that extremists within the ] were plotting Elizabeth's assassination.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Dubois |first=Paul |date=12 October 1964 |title=Demonstrations Mar Quebec Events Saturday |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1946&dat=19641012&id=3K4tAAAAIBAJ&sjid=YZ8FAAAAIBAJ&pg=6599,2340498 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210123163032/https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1946&dat=19641012&id=3K4tAAAAIBAJ&sjid=YZ8FAAAAIBAJ&pg=6599,2340498 |archive-date=23 January 2021 |access-date=6 March 2010 |work=] |page=1 |mode=cs2}}</ref> No assassination attempt was made, but a riot did break out while she was in ]; her "calmness and courage in the face of the violence" was noted.{{Sfn|ps=none|Bousfield|Toffoli|2002|p=139}} | |||

| ] (left), US President ] and First Lady ], 1970]] | |||

| Elizabeth gave birth to her third child, ], in February 1960; this was the first birth to a reigning British monarch since 1857.<ref>{{Cite news |date=4 September 2017 |title=Royal Family tree and line of succession |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-23272491 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210311001051/https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-23272491 |archive-date=11 March 2021 |access-date=13 May 2022 |work=BBC News |mode=cs2}}</ref> Her fourth child, ], was born in March 1964.<ref>{{London Gazette |issue=43268 |date=11 March 1964 |page=2255 |nolink=y |mode=cs2}}</ref> | |||

| Elizabeth's pregnancies with Princes ] and ], in 1959 and 1963, mark the only times she has not performed the ] during her reign.<ref>{{cite web|author=Dymond, Glenn|date=5 March 2010|url=http://www.parliament.uk/documents/documents/upload/lln2010-007.pdf|title=Ceremonial in the House of Lords|publisher=House of Lords Library|page=12|accessdate=5 June 2010}}</ref> In addition to performing traditional ceremonies, she also instituted new practices. Her first royal walkabout, meeting ordinary members of the public, took place during a tour of Australia and New Zealand in 1970.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.royal.gov.uk/HMTheQueen/Publiclife/PublicLife1962-1971/1962-1971.aspx|title=Public life 1962–1971|publisher=Royal Household|accessdate=1 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| === Political reforms and crises === | |||

| The 1960s and 1970s saw an acceleration in the ] of Africa and the ]. Over 20 countries gained independence from Britain as part of a planned transition to self-government. In 1965, however, ]n Prime Minister ], in opposition to moves toward majority rule, ] from Britain while still expressing "loyalty and devotion" to Elizabeth. Although the Queen dismissed him in a formal declaration, and the international community applied sanctions against Rhodesia, his regime survived for over a decade.<ref>Bond, p. 66; Pimlott, pp. 345–354</ref> | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| | total_width = 400 | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | direction = horizontal | |||

| | image1 = Elizabeth II in Queensland, Australia, 1970.jpg | |||

| | alt1 = Elizabeth waving from a car | |||

| | caption1 = In ], Australia, 1970 | |||

| | image2 = Stevan Kragujevic, Elizabeth II i Josip Broz Tito,1972, u Beogradu.jpg | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| | caption2 = With ] of ] in Belgrade, 1972 | |||

| }} | |||

| The 1960s and 1970s saw an acceleration in the ] and the Caribbean. More than 20 countries gained independence from Britain as part of a planned transition to self-government. In 1965, however, the Rhodesian prime minister, ], in opposition to moves towards ], ] while expressing "loyalty and devotion" to Elizabeth. Although Elizabeth formally dismissed him, and the international community applied sanctions against Rhodesia, his regime survived for over a decade.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Bond|2006|1p=66|Pimlott|2001|2pp=345–354}} As Britain's ties to its former empire weakened, the British government sought entry to the ], a goal it ].{{Sfnm|ps=none|Bradford|2012|1pp=123, 154, 176|Pimlott|2001|2pp=301, 315–316, 415–417}} | |||

| In February 1974, British Prime Minister ] advised the Queen to call a ] in the middle of her tour of the ]n ], requiring her to fly back to Britain.<ref>Bradford, p. 181; Pimlott, p. 418</ref> The election resulted in a hung parliament; Heath's Conservatives were not the largest party, but could stay in office if they formed a coalition with the ]. Heath only resigned when discussions on forming a coalition foundered, after which the Queen asked the ], ] ], to form a government.<ref>Bradford, p. 181; Marr, p. 256; Pimlott, p. 419; Shawcross, pp. 109–110</ref> | |||

| In 1966, the Queen was criticised for waiting eight days before visiting the village of ], where ] killed 116 children and 28 adults. Martin Charteris said that the delay, made on his advice, was a mistake that she later regretted.<ref>{{Cite news |date=10 September 2022 |title=Aberfan disaster: The Queen's regret after tragedy |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-42101460 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221123064943/https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-42101460 |archive-date=23 November 2022 |access-date=20 December 2022 |work=BBC News |mode=cs2}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=17 November 2019 |title=How filming the agony of Aberfan for The Crown revealed a village still in trauma |url=https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2019/nov/17/television-drama-the-crown-portrays-aberfan-disaster |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221221000005/https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2019/nov/17/television-drama-the-crown-portrays-aberfan-disaster |archive-date=21 December 2022 |access-date=20 December 2022 |website=The Guardian |mode=cs2}}</ref> | |||

| A year later, at the height of the ], ] ] was dismissed from his post by ] Sir ], after the Opposition-controlled ] rejected Whitlam's budget proposals.<ref name=Aus>Bond, p. 96; Marr, p. 257; Pimlott, p. 427; Shawcross, p. 110</ref> As Whitlam had a majority in the ], ] ] appealed to the Queen to reverse Kerr's decision. She declined, stating that she would not interfere in decisions reserved by the ] for the governor-general.<ref>Pimlott, pp. 428–429</ref> The crisis fuelled ].<ref name=Aus/> | |||

| Elizabeth toured ] in October 1972, becoming the first British monarch to visit a ].{{Sfn|ps=none|Hoey|2022|page=58}} She was received at the airport by President ], and a crowd of thousands greeted her in ].<ref>{{Cite news |date=18 October 1972 |title=Big Crowds in Belgrade Greet Queen Elizabeth |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1972/10/18/archives/big-crowds-in-belgrade-greet-queen-elizabeth.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220606155117/https://www.nytimes.com/1972/10/18/archives/big-crowds-in-belgrade-greet-queen-elizabeth.html |archive-date=6 June 2022 |access-date=8 September 2022 |work=The New York Times |mode=cs2}}</ref> | |||

| ===Silver Jubilee=== | |||

| In 1977, Elizabeth marked the ]. Parties and events took place throughout the Commonwealth, many coinciding with ]. The celebrations re-affirmed the Queen's popularity, despite virtually coincident negative press coverage of Princess Margaret's separation from her husband.<ref>Pimlott, p. 449</ref> In 1978, the Queen endured a state visit to the United Kingdom by ]'s communist dictator, ], and his wife, ],<ref>Hardman, p. 137; Roberts, pp. 88–89; Shawcross, p. 178</ref> though privately she thought they had "blood on their hands".<ref>Elizabeth to her staff, quoted in Shawcross, p. 178</ref> The following year brought two blows: one was the unmasking of ], former ], as a communist spy; the other was the assassination of her relative and in-law ] by the ].<ref>Pimlott, pp. 336–337, 470–471; Roberts, pp. 88–89</ref> | |||

| In February 1974, British prime minister ] advised Elizabeth to call ] in the middle of her tour of the ]n ], requiring her to fly back to Britain.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Bradford|2012|1p=181|Pimlott|2001|2p=418}} The election resulted in a ]; Heath's Conservatives were not the largest party but could stay in office if they formed a coalition with the ]. When discussions on forming a coalition foundered, Heath resigned, and Elizabeth asked the ], ]'s ], to form a government.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Bradford|2012|1p=181|Marr|2011|2p=256|Pimlott|2001|3p=419|Shawcross|2002|4pp=109–110}} | |||

| According to ], by the end of the 1970s the Queen was worried that the Crown "had little meaning for" ], the ].<ref name=Post/> ] said that the Queen found Trudeau "rather disappointing".<ref name=Post>{{cite news |last=Heinricks |first=Geoff |title=Trudeau: A drawer monarchist |work=] |location=Toronto |date=29 September 2000 |page=B12}}</ref> Trudeau's supposed republicanism seemed to be confirmed by his antics, such as sliding down banisters at Buckingham Palace and pirouetting behind the Queen's back in 1977, and the removal of various ] during his term of office.<ref name=Post/> In 1980, Canadian politicians sent to London to discuss the ] of the ] found the Queen "better informed ... than any of the British politicians or bureaucrats".<ref name=Post/> She was particularly interested after the failure of Bill C-60, which would have affected her role as ].<ref name=Post/> Patriation removed the role of the ] from the Canadian constitution, but the monarchy was retained. Trudeau said in his memoirs that the Queen favoured his attempt to reform the constitution and that he was impressed by "the grace she displayed in public" and "the wisdom she showed in private".<ref>Trudeau, p. 313</ref> | |||

| A year later, at the height of the ], the Australian prime minister, ], was dismissed from his post by Governor-General ], after the Opposition-controlled ] rejected Whitlam's budget proposals.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Bond|2006|1p=96|Marr|2011|2p=257|Pimlott|2001|3p=427|Shawcross|2002|4p=110}} As Whitlam had a majority in the ], Speaker ] appealed to Elizabeth to reverse Kerr's decision. She declined, saying she would not interfere in decisions reserved by the ] for the ].{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|pp=428–429}} The crisis fuelled ].{{Sfnm|ps=none|Bond|2006|1p=96|Marr|2011|2p=257|Pimlott|2001|3p=427|Shawcross|2002|4p=110}} | |||

| ===1980s=== | |||

| ] at the 1986 ] ceremony]] | |||

| During the 1981 ] ceremony and only six weeks before the ], six shots were fired at the Queen from close range as she rode down ] on her horse, ]. Police later discovered that the shots were blanks. The 17-year-old assailant, ], was sentenced to five years in prison and released after three.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/september/14/newsid_2516000/2516713.stm|title=Queen's 'fantasy assassin' jailed|publisher=BBC|accessdate=21 June 2010|date=14 September 1981}}</ref> The Queen's composure and skill in controlling her mount were widely praised.<ref>Lacey, p. 281; Pimlott, pp. 476–477; Shawcross, p. 192</ref> From April to September 1982, the Queen remained anxious<ref>Bond, p. 115; Pimlott, p. 487</ref> but proud<ref>Shawcross, p. 127</ref> of her son, Prince Andrew, who was serving with British forces during the ]. On 9 July, the Queen awoke in her bedroom at Buckingham Palace to find an intruder, ], in the room with her. Remaining calm and through two calls to the Palace police switchboard, she spoke to Fagan while he sat at the foot of her bed until assistance arrived seven minutes later.<ref>Lacey, pp. 297–298; Pimlott, p. 491</ref> Though she hosted US President ] at Windsor Castle in 1982 and visited ] in 1983, she was angered when his administration ordered the ], one of her Caribbean realms, without informing her.<ref>Bond, p. 188; Pimlott, p. 497</ref> | |||

| ], members of the royal family and Elizabeth (centre), London, 1977]] | |||

| Intense media interest in the opinions and private lives of the royal family during the 1980s led to a series of sensational stories in the press, not all of which were entirely true.<ref>Pimlott, pp. 488–490</ref> As ], editor of '']'', told his staff: "Give me a Sunday for Monday splash on the Royals. Don't worry if it's not true—so long as there's not too much of a fuss about it afterwards."<ref>Pimlott, p. 521</ref> Newspaper editor ] wrote in '']'' of 21 September 1986: "The royal soap opera has now reached such a pitch of public interest that the boundary between fact and fiction has been lost sight of ... it is not just that some papers don't check their facts or accept denials: they don't care if the stories are true or not." It was reported, most notably in '']'' of 20 July 1986, that the Queen was worried that ] ]'s economic policies fostered social divisions and was alarmed by high unemployment, ], the violence of a ], and Thatcher's refusal to apply sanctions against the ] regime in South Africa. The sources of the rumours included royal aide ] and ] ], but Shea claimed his remarks were taken out of context and embellished by speculation.<ref>Pimlott, pp. 503–515; see also Neil, pp. 195–207 and Shawcross, pp. 129–132</ref> Thatcher reputedly said the Queen would vote for the ]—Thatcher's political opponents.<ref>Thatcher to ] quoted in Neil, p. 207; ] quoted in ]'s diary of 26 October 1990</ref> Thatcher's biographer ] claimed "the report was a piece of journalistic mischief-making".<ref>Campbell, p. 467</ref> Belying reports of acrimony between them, Thatcher later conveyed her personal admiration for the Queen and,<ref>Thatcher, p. 309</ref> after Thatcher's replacement as prime minister by ], the Queen gave two honours in her personal gift to Thatcher: appointment to the ] and the ].<ref>Roberts, p. 101; Shawcross, p. 139</ref> Former Canadian Prime Minister ] said Elizabeth was a "behind the scenes force" in ending ].<ref name=Geddes>{{cite journal| last=Geddes| first=John| title=The day she descended into the fray| journal=Maclean's| edition=Special Commemorative Edition: The Diamond Jubilee: Celebrating 60 Remarkable years| year=2012| page=72}}</ref><ref name=MacQueen>{{cite journal| last1=MacQueen| first1=Ken| last2=Treble| first2=Patricia| title=The Jewel in the Crown| journal=Maclean's| edition=Special Commemorative Edition: The Diamond Jubilee: Celebrating 60 Remarkable years| year=2012| pages=43–44}}</ref> | |||

| In 1977, Elizabeth marked the ] of her accession. Parties and events took place throughout the Commonwealth, many coinciding with ]. The celebrations re-affirmed Elizabeth's popularity, despite virtually coincident negative press coverage of Princess Margaret's separation from her husband, Lord Snowdon.{{Sfn|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|p=449}} In 1978, Elizabeth endured a state visit to the United Kingdom by ]'s communist leader, ], and his wife, ],{{Sfnm|ps=none|Hardman|2011|1p=137|Roberts|2000|2pp=88–89|Shawcross|2002|3p=178}} though privately she thought they had "blood on their hands".<ref>Elizabeth to her staff, quoted in {{Harvnb|Shawcross|2002|p=178}}</ref> The following year brought two blows: the unmasking of ], former ], as a communist spy and the ] by the ].{{Sfnm|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|1pp=336–337, 470–471|Roberts|2000|2pp=88–89}} | |||

| According to ], by the end of the 1970s, Elizabeth was worried ] "had little meaning for" ], the Canadian prime minister.<ref name="Post" /> ] said Elizabeth found Trudeau "rather disappointing".<ref name="Post">{{Cite news |last=Heinricks |first=Geoff |date=29 September 2000 |title=Trudeau: A drawer monarchist |work=] |location=Toronto |page=B12 |mode=cs2}}</ref> Trudeau's supposed ] seemed to be confirmed by his antics, such as sliding down banisters at Buckingham Palace and pirouetting behind Elizabeth's back in 1977, and the removal of various ] during his term of office.<ref name="Post" /> In 1980, Canadian politicians sent to London to discuss the ] of the ] found Elizabeth "better informed ... than any of the British politicians or bureaucrats".<ref name="Post" /> She was particularly interested after the failure of Bill C-60, which would have affected her role as head of state.<ref name="Post" /> | |||

| In 1987, in Canada, Elizabeth publicly pronounced her support for that country's politically divisive ], prompting criticism from opponents of the constitutional amendments, including Pierre Trudeau.<ref name=Geddes /> The same year, the elected ]an government was deposed in ]. Elizabeth, as ], supported the attempts of the ], Ratu Sir ], to assert executive power and negotiate a settlement. Coup leader ] deposed Ganilau and declared Fiji a republic.<ref>Pimlott, pp. 515–516</ref> By the start of 1991, republican feeling in Britain had risen because of press estimates of the Queen's private wealth—which were contradicted by the Palace—and reports of affairs and strained marriages among her extended family.<ref>Pimlott, pp. 519–534</ref> The involvement of the younger royals in the charity game show '']'' was ridiculed<ref>Hardman, p. 81; Lacey, p. 307; Pimlott, pp. 522–526</ref> and the Queen was the target of satire.<ref>Lacey, pp. 293–294; Pimlott, p. 541</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Perils and dissent === | ||

| ] | |||

| In 1991, in the wake of victory in the ], Elizabeth became the first British monarch to address a ] of the ].<ref>Pimlott, p. 538</ref> | |||

| During the 1981 ] ceremony, six weeks before the ], six shots were fired at Elizabeth from close range as she rode down ], on her horse, ]. Police later discovered the shots were blanks. The 17-year-old assailant, ], was sentenced to five years in prison and released after three.<ref>{{Cite news |date=14 September 1981 |title=Queen's 'fantasy assassin' jailed |url=https://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/september/14/newsid_2516000/2516713.stm |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110728131747/https://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/september/14/newsid_2516000/2516713.stm |archive-date=28 July 2011 |access-date=21 June 2010 |work=BBC News |mode=cs2}}</ref> Elizabeth's composure and skill in controlling her mount were widely praised.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Lacey|2002|1p=281|Pimlott|2001|2pp=476–477|Shawcross|2002|3p=192}} That October, Elizabeth was the subject of another attack while on a visit to ], New Zealand. ], who was 17 years old, fired a shot with a ] from the fifth floor of a building overlooking the parade but missed.<ref>{{Cite news |last=McNeilly |first=Hamish |date=1 March 2018 |title=Intelligence documents confirm assassination attempt on Queen Elizabeth in New Zealand |url=https://www.smh.com.au/world/oceania/intelligence-documents-confirm-assassination-attempt-on-queen-elizabeth-in-new-zealand-20180301-p4z282.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190626183822/https://www.smh.com.au/world/oceania/intelligence-documents-confirm-assassination-attempt-on-queen-elizabeth-in-new-zealand-20180301-p4z282.html |archive-date=26 June 2019 |access-date=1 March 2018 |work=] |mode=cs2}}</ref> Lewis was arrested, but instead of being charged with ] or ] was sentenced to three years in jail for unlawful possession and discharge of a firearm. Two years into his sentence, he attempted to escape a ] with the intention of assassinating Charles, who was visiting the country with ] and their son ].<ref>{{Cite news |last=Ainge Roy |first=Eleanor |date=13 January 2018 |title='Damn ... I missed': the incredible story of the day the Queen was nearly shot |url=https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/jan/13/queen-elizabeth-assassination-attempt-new-zealand-1981 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180301120257/https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/jan/13/queen-elizabeth-assassination-attempt-new-zealand-1981 |archive-date=1 March 2018 |access-date=1 March 2018 |work=The Guardian |mode=cs2}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| In a speech on 24 November 1992, to mark the 40th anniversary of her accession, Elizabeth called 1992 her '']'', meaning ''horrible year''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.royal.gov.uk/ImagesandBroadcasts/Historic%20speeches%20and%20broadcasts/Annushorribilisspeech24November1992.aspx|title=Annus horribilis speech, 24 November 1992|publisher=Royal Household|accessdate=6 August 2009}}</ref> In March, her second son ], and his wife ], separated; in April, her daughter ], divorced her husband Captain ];<ref>Lacey, p. 319; Marr, p. 315; Pimlott, pp. 550–551</ref> during a state visit to ] in October, angry demonstrators in ] threw eggs at her;<ref>{{cite web|author=Stanglin, Doug|title=German study concludes 25,000 died in Allied bombing of Dresden|url=http://content.usatoday.com/communities/ondeadline/post/2010/03/official-german-study-concludes-25000-died-in-allied-bombing-of-dresden/1?csp=34|work=USA Today|date=18 March 2010|accessdate=19 March 2010}}</ref> and, in November, Windsor Castle ]. The monarchy received increased criticism and public scrutiny.<ref>Brandreth, p. 377; Pimlott, pp. 558–559; Roberts, p. 94; Shawcross, p. 204</ref> In an unusually personal speech, the Queen said that any institution must expect criticism, but suggested it be done with "a touch of humour, gentleness and understanding".<ref>Brandreth, p. 377</ref> Two days later, the Prime Minister, ], announced reforms of the royal finances that had been planned since the previous year, including the Queen paying ] for the first time from 1993 and a reduction in the ].<ref>Bradford, p. 229; Lacey, pp. 325–326; Pimlott, pp. 559–561</ref> In December, ], and his wife, ], formally separated.<ref>Bradford, p. 226; Hardman, p. 96; Lacey, p. 328; Pimlott, p. 561</ref> The year ended with a lawsuit as the Queen sued '']'' newspaper for breach of copyright when it published the text of her ] two days before its broadcast. The newspaper was forced to pay her legal fees and donated £200,000 to charity.<ref>Pimlott, p. 562</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| In the ensuing years, public revelations on the state of Charles and Diana's marriage continued.<ref>Brandreth, p. 356; Pimlott, pp. 572–577; Roberts, p. 94; Shawcross, p. 168</ref> Even though support for republicanism in Britain seemed higher than at any time in living memory, republicanism remained a minority viewpoint and the Queen herself had high approval ratings.<ref>MORI poll for '']'' newspaper, March 1996, quoted in Pimlott, p. 578 and {{cite news|author=O'Sullivan, Jack|date=5 March 1996|url=http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/watch-out-the-roundheads-are-back-1340396.html|title=Watch out, the Roundheads are back|work=The Independent|accessdate=17 September 2011}}</ref> Criticism was focused on the institution of monarchy itself and the Queen's wider family rather than the Queen's own behaviour and actions.<ref>Pimlott, p. 578</ref> In consultation with her husband, Prime Minister John Major, ] ], and her private secretary, ], she wrote to Charles and Diana at the end of December 1995, saying that a divorce was desirable.<ref>Brandreth, p. 357; Pimlott, p. 577</ref> A year after the divorce, which took place in 1996, ] on 31 August 1997. The Queen was on holiday with her son and grandchildren at ]. Diana's two sons wanted to attend church and so the Queen and Prince Philip took them that morning.<ref>Brandreth, p. 358; Hardman, p. 101; Pimlott, p. 610</ref> After that single public appearance, for five days the Queen and the Duke shielded their grandsons from the intense press interest by keeping them at Balmoral where they could grieve in private,<ref>Bond, p. 134; Brandreth, p. 358; Marr, p. 338; Pimlott, p. 615</ref> but the royal family's seclusion and a failure to fly a flag at ] over Buckingham Palace caused public dismay.<ref name=MacQueen/><ref>Bond, p. 134; Brandreth, p. 358; Lacey, pp. 6–7; Pimlott, p. 616; Roberts, p. 98; Shawcross, p. 8</ref> Pressured by the hostile reaction, the Queen agreed to a live broadcast to the world and returned to London to deliver it on 5 September, the day before ].<ref>Brandreth, pp. 358–359; Lacey, pp. 8–9; Pimlott, pp. 621–622</ref> In the broadcast, she expressed admiration for Diana and her feelings "as a grandmother" for Princes ] and ].<ref name="b&b">Bond, p. 134; Brandreth, p. 359; Lacey, pp. 13–15; Pimlott, pp. 623–624</ref> As a result, much of the public hostility evaporated.<ref name="b&b"/> | |||

| From April to September 1982, Elizabeth's son Andrew served with British forces in the ], for which she reportedly felt anxiety{{Sfnm|ps=none|Bond|2006|1p=115|Pimlott|2001|2p=487}} and pride.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Pimlott|2001|1p=487|Shawcross|2002|2p=127}} On 9 July, she awoke in her bedroom at Buckingham Palace to find an intruder, ], in the room with her. In a serious lapse of security, assistance only arrived after two calls to the Palace police switchboard.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Lacey|2002|1pp=297–298|Pimlott|2001|2p=491}} After hosting US president ] at Windsor Castle in 1982 and visiting ] in 1983, Elizabeth was angered when ] ordered the ], one of her Caribbean realms, without informing her.{{Sfnm|ps=none|Bond|2006|1p=188|Pimlott|2001|2p=497}} | |||