| Revision as of 14:32, 2 February 2015 editRwendland (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers30,149 editsm Undid revision 645308707 by 223.136.79.38 (talk)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:05, 10 January 2025 edit undo2406:3003:2006:dd06:a9c7:9245:39c4:a7ee (talk) →Japanese rule (1910–1945)Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| (823 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Separation of North and South Korea}} | |||

| ], first divided along the 38th parallel, later along the demarcation line.]] | |||

| {{Use Oxford spelling|date=November 2019}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2019}} | |||

| {{History_of Korea}} | |||

| ] that surrounds the Military Demarcation Line]] | |||

| ] was divided along the ] from 1945 until 1950 and along the ] from 1953 to present.]] | |||

| {{History of Korea}} | |||

| The '''division of Korea''' '']'' began on 2 September 1945, when Japan signed the ], thus ending the ] of ]. It was officially divided with the establishment of the two Koreas in 1948. During World War II, the ] had already been considering the question of ]'s future following Japan's eventual surrender in the war. The leaders reached an understanding that Korea would be liberated from Japan but would be placed under an ] until the Koreans would be deemed ready for self-rule.<ref name=Lee2006>{{cite book| title = The Partition of Korea After World War II: A Global History | last = Lee | first = Jongsoo | year = 2006| publisher = Palgrave Macmillan| location = New York | isbn = 978-1-4039-6982-8 }}</ref>{{rp||5–17}} In the last days of the war, the ] proposed dividing the Korean peninsula into two occupation zones (a U.S. and ] one) with the ] as the dividing line. The Soviets accepted their proposal and agreed to divide Korea.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Fry |first1=Michael |title=National Geographic, Korea, and the 38th Parallel |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/130805-korean-war-dmz-armistice-38-parallel-geography |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210225074751/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/130805-korean-war-dmz-armistice-38-parallel-geography |url-status=dead |archive-date=25 February 2021 |publisher=National Geographic |access-date=15 May 2021 |language=en |date=5 August 2013}}</ref> | |||

| It was understood that this division was only a temporary arrangement until the trusteeship could be implemented. In December 1945, the ] resulted in an agreement on a five-year, four-power Korean trusteeship.<ref name=mccune-194703/> However, with the onset of the ] and other factors both international and domestic, including Korean opposition to the trusteeship, negotiations between the United States and the Soviet Union over the next two years regarding the implementation of the trusteeship failed, thus effectively nullifying the only agreed-upon framework for the re-establishment of an independent and unified Korean state.<ref name=Lee2006/>{{rp|45–154}} With this, the Korean question was referred to the ]. In 1948, after the UN failed to produce an outcome acceptable to the Soviet Union, ] were held in the ] only. ] won the election, while ] consolidated his position as the leader of Soviet-occupied northern Korea. This led to the establishment of the ] in southern Korea on 15 August 1948, promptly followed by the establishment of the ] in northern Korea on 9 September 1948. The United States supported the South, the Soviet Union supported the North, and each government claimed sovereignty over the whole Korean peninsula. | |||

| The '''division of Korea''' into ] and ] was the result of the 1945 ] victory in ], ending the ]'s 35-year ] by ]. The ] and the ] agreed to temporarily occupy the country as a ] with the zone of control along the ]. The purpose of this trusteeship was to establish a Korean provisional government which would become "free and independent in due course",<ref name = "Savada">{{citation | url = http://countrystudies.us/south-korea/8.htm | chapter = World War II and Korea | editor1-first = Andrea Matles | editor1-last = Savada | editor2-first = William | editor2-last = Shaw | title = South Korea: A Country Study | location = Washington, DC | series = GPO | publisher = Library of Congress | year = 1990}}</ref> as set forth in the ]. | |||

| On 25 June 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea in an attempt to re-unify the peninsula under its communist rule. The subsequent ], which lasted from 1950 to 1953, ended with a ] and has left Korea divided by the ] (DMZ) up to the present day. | |||

| Japan capitulated in August 1945. An effort to construct an independent government for the entire ] was made in September 1945 by the statesman ]. However, he had to step down under pressure from the ]. An initiative to hold general and free elections in the entire Korea came up in the ] in the fall of 1947. However this initiative did not materialize because of disagreement between the ] and the ]: During this period of two years between the fall of 1945 and the fall of 1947, in the absence of the opportunity to set up a unified government, two separate governments began evolving and consolidating in the south and in the north. | |||

| During the ], the ] for Peace, Prosperity and Reunification of the Korean Peninsula was adopted between ], the ], and ], the ]. During the ], several actions were taken toward reunification along the border, such as the dismantling of guard posts and the creation of buffer zones to prevent clashes. On 12 December 2018, soldiers from both Koreas crossed the ] (MDL) into the opposition countries for the first time in history.<ref name=cbsnewsdec12>{{cite web|url=https://www.cbsnews.com/news/north-korea-south-korea-troops-cross-demilitarized-zone-in-peace-first-time/|title=Troops cross North-South Korea Demilitarized Zone in peace for 1st time ever|website=Cbsnews.com|date=12 December 2018 |access-date=30 December 2018}}</ref><ref name=ecdec12>{{cite web|url=https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/north-and-south-korean-soldiers-enter-each-others-territory/north-invades-the-south/slideshow/67057861.cms|title=North and South Korean soldiers enter each other's territory|website=The Economic Times|access-date=30 December 2018|archive-date=16 December 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181216000253/https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/north-and-south-korean-soldiers-enter-each-others-territory/north-invades-the-south/slideshow/67057861.cms|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| A ] was permanently established under Soviet auspices in the north and a pro-] state was set up in the south. The two superpowers backed different leaders and two States were effectively established, each of which claimed sovereignty over the whole Korean peninsula. | |||

| In October 2024, the ] was amended to remove references to reunification and labelled South Korea an "enemy state".<ref name="NoUnity">{{Cite news |last=Ng |first=Kelly |date=17 October 2024 |title=N Korean constitution now calls South 'hostile state' |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c1wnxlxxwq2o |access-date=25 October 2024 |work=BBC News}}</ref> This was preceded by the destruction of roads connecting the north to the south in a bid to "completely separate" the two states.<ref>{{Cite news |date=15 October 2024 |title=Moment North Korea blows up roads connecting to South Korea |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/videos/c70wgxr4zndo |access-date=25 October 2024 |work=BBC News}}</ref> | |||

| The ], which lasted from 1950 to 1953, left the two Koreas separated by the ] through the ] and into the 2010s. The 2000s saw some improved relations between the two sides, overseen in the south by liberal governments, who were more amicable towards the north than previous governments had been.<ref>{{cite news|url= http://www.boston.com/news/globe/editorial_opinion/oped/articles/2005/06/09/koreas_slow_motion_reunification/ |title=Korea's slow-motion reunification|publisher=Boston Globe|date=June 9, 2005|accessdate=2007-08-13|first1=John|last1=Feffer}}</ref> These changes were largely reversed under conservative South Korean president ] who opposed the north's continued development of nuclear weapons. In addition to this, after the death of Kim Jong-il, the incumbent supreme leader, Kim Jong-un threatened to ]. | |||

| ==Historical background== | ==Historical background== | ||

| ===Japanese rule (1910–1945)=== | |||

| {{Main|Korea under Japanese rule}} | |||

| When the ] ended in 1905, Korea (then the ]) became a nominal ] of Japan and was annexed by Japan in 1910. Emperor ] was removed. In the following decades, nationalist and radical groups emerged to struggle for independence. Divergent in their outlooks and approaches, these groups failed to come together in one national movement.<ref>{{cite book| title = The Making of Modern Korea | last = Buzo | first = Adrian | year = 2002| publisher = Routledge| location = London | isbn = 978-0-415-23749-9 |pages=31–37}}</ref><ref name=Cumings2005>{{cite book | title = Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History| last = Cumings| first = Bruce| author-link = Bruce Cumings| year = 2005| publisher = ]| location = New York| isbn = 978-0-393-32702-1}}</ref>{{rp|156–160}} The ] (KPG) in exile in China failed to obtain widespread recognition.<ref name=Cumings2005/>{{rp|159–160}} | |||

| ===World War II=== | |||

| ===Korea under Japanese rule (1910–1945)=== | |||

| ] giving a speech in the Committee for Preparation of Korean Independence in ] on 16 August 1945|left]] | |||

| As the ] ended in 1905, Korea became a nominal ], and was annexed in 1910 by Japan. | |||

| At the ] in November 1943, in the middle of ], ], ] and ] agreed that Japan should lose all the territories it had conquered by force. At the end of the conference, the three powers declared that they were "mindful of the enslavement of the people of Korea, ... determined that in due course Korea shall become free and independent."<ref name="cairo_communique">{{cite news|url=http://www.ndl.go.jp/constitution/e/shiryo/01/002_46/002_46tx.html|publisher=Japan National Diet Library|title=Cairo Communique, December 1, 1943|date=1 December 1943|access-date=10 November 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101206020831/http://www.ndl.go.jp/constitution/e/shiryo/01/002_46/002_46tx.html|archive-date=6 December 2010|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name = "Savada">{{cite book | chapter-url = http://countrystudies.us/south-korea/8.htm | chapter = World War II and Korea | editor1-first = Andrea Matles | editor1-last = Savada | editor2-first = William | editor2-last = Shaw | title = South Korea: A Country Study | location = Washington, DC | series = GPO | publisher = Library of Congress | year = 1990 | access-date = 2006-05-16 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110629082133/http://countrystudies.us/south-korea/8.htm | archive-date = 2011-06-29 | url-status = live }}</ref> Roosevelt floated the idea of a ] over Korea but did not obtain agreement from the other powers. Roosevelt raised the idea with ] at the ] in November 1943 and the ] in February 1945. Stalin did not disagree but advocated that the period of trusteeship be short.<ref name=Cumings2005/>{{rp|187–188}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Stueck |first=William W. |year=2002 |title=Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=Princeton, NJ |isbn=978-0-691-11847-5|page=20}}</ref> | |||

| At the Tehran and Yalta Conferences, Stalin promised to join his ] in the ] in two to three months after ]. On 8 August 1945, two days after the ] was dropped on ], but before the second bomb was dropped at ], the USSR ].<ref name = "Walker">{{cite book | last = Walker | first = J Samuel | title = Prompt and Utter Destruction: Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs Against Japan | url = https://archive.org/details/promptutterdestr00walk | url-access = registration | publisher = The University of North Carolina Press | year = 1997 | location = Chapel Hill | page = | isbn = 978-0-8078-2361-3}}</ref> As war began, the Commander-in-Chief of Soviet Forces in the Far East, Marshal ], called on Koreans to rise up against Japan, saying "a banner of liberty and independence is rising in ]".<ref name="auto5">{{cite news|url=https://www.nknews.org/2018/11/how-kim-il-sung-became-north-koreas-great-leader|title=How Kim Il Sung became North Korea's Great Leader|first=Fyodor|last=Tertitskiy|publisher=]|date=6 November 2018|access-date=15 November 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181115195059/https://www.nknews.org/2018/11/how-kim-il-sung-became-north-koreas-great-leader|archive-date=15 November 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===End of World War II (1939–45)=== | |||

| {{Main|World War II}} | |||

| In November 1943, ], ] and ] met at the ] to discuss what should happen to ]'s colonies, and agreed that Japan should lose all the territories it had conquered by force. In the declaration after this conference, ] was mentioned for the first time. The three powers declared that they were, "mindful of the enslavement of the people of Korea, ... determined that in due course Korea shall become free and independent.”<ref name="cairo_communique">{{cite news|url=http://www.ndl.go.jp/constitution/e/shiryo/01/002_46/002_46tx.html|publisher=Japan National Diet Library|title=Cairo Communique, December 1, 1943|date=December 1, 1943}}</ref> | |||

| Soviet troops advanced rapidly, and the U.S. government became anxious that they would occupy the whole of Korea. On 10 August 1945 two young officers – ] and ] – were assigned to define an American occupation zone. Working on extremely short notice and completely unprepared, they used a '']'' map to decide on the ] as the dividing line. They chose it because it divided the country approximately in half but would place the capital Seoul under American control. No experts on Korea were consulted. The two men were unaware that forty years before, ] and pre-revolutionary ] had discussed sharing Korea along the same parallel. Rusk later said that had he known, he "almost surely" would have chosen a different line.<ref>{{Cite book| last1= Oberdorfer| first1=Don| last2=Carlin| first2=Robert | title=The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History | publisher = Basic Books| year = 2014 | page = 5 | isbn = 9780465031238}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | |||

| For Korean nationalists who wanted immediate independence, the phrase "in due course" was cause for dismay. In any case, discussion of Korea among the Allies would not resume until Germany was defeated. | |||

| |last1 = Seth | |||

| |first1 = Michael J. | |||

| |title = A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present | |||

| |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=WJtMGXyGlUEC | |||

| |publisher = Rowman & Littlefield Publishers | |||

| |publication-date = 2010 | |||

| |page = 306 | |||

| |isbn = 9780742567177 | |||

| |access-date = 2015-11-16 | |||

| |date = 2010-10-16 | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160101084332/https://books.google.com/books?id=WJtMGXyGlUEC | |||

| |archive-date = 2016-01-01 | |||

| |url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> The division placed sixteen million Koreans in the American zone and nine million in the Soviet zone.<ref>{{cite book| title = The Making of Modern Korea | last = Buzo | first = Adrian | year = 2002| publisher = Routledge| location = London | isbn = 978-0-415-23749-9 |page=53}}</ref> Rusk observed, "even though it was further north than could be realistically reached by US forces, in the event of Soviet disagreement ... we felt it important to include the capital of Korea in the area of responsibility of American troops". He noted that he was "faced with the scarcity of US forces immediately available, and time and space factors, which would make it difficult to reach very far north, before Soviet troops could enter the area".<ref>{{cite book| last = Goulden| first = Joseph C| title = Korea: the Untold Story of the War| publisher = ]| location = New York| year = 1983| page = 17| isbn = 978-0070235809}}</ref> To the surprise of the Americans, the Soviet Union immediately accepted the division.<ref name="auto5" /><ref name="auto1">{{cite book |author= Hyung Gu Lynn |date= 2007 |title= Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989 |publisher= Zed Books |page=18}}</ref> The agreement was incorporated into ] (approved on 17 August 1945) for the surrender of Japan.<ref name="auto1" /> | |||

| === Liberation, confusion, and conflict === | |||

| On 10 August, Soviet forces entered northern Korea.<ref name=":022">{{Cite book |last=Li |first=Xiaobing |title=The Cold War in East Asia |date=2018 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-138-65179-1 |location=Abingdon, Oxon}}</ref>{{Rp|page=82}} Soviet forces began amphibious landings in Korea by 14 August and rapidly took over the northeast of the country, and on 16 August they landed at ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Seth |first1=Michael J. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uJHyoC2Pt60C |title=A Concise History of Modern Korea: From the Late Nineteenth Century to the Present |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |year=2010 |isbn=9780742567139 |series=Hawaìi studies on Korea |publication-date=2010 |page=86 |access-date=2015-11-16 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160519014155/https://books.google.com/books?id=uJHyoC2Pt60C |archive-date=2016-05-19 |url-status=live}}</ref> Japanese resistance was light, and Soviet forces secured most major cities in the north by 24 August<ref name=":022" />{{Rp|page=82}} (including ], the second largest city in the Korean Peninsula after Seoul).<ref name="auto1" /> Having fought Japan on Korean soil, the Soviet forces were well-received by Koreans.<ref name=":022" />{{Rp|page=82}} | |||

| ] | |||

| With the war's end in sight in August 1945, there was still no consensus on Korea's fate among Allied leaders. Many Koreans on the peninsula had made their own plans for the future of Korea, and few of these plans included the re-occupation of Korea by foreign forces. Following the atomic bombing of ] on August 6, 1945, Soviet soldiers ],<ref name = "Walker">{{cite book | last = Walker | first = J Samuel | title = Prompt and Utter Destruction: Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs Against Japan | publisher = The University of North Carolina Press | year = 1997 | location = Chapel Hill | page = 82 | isbn = 0-8078-2361-9}}</ref> as per Stalin's agreement with Roosevelt at the ] of February 1945. | |||

| Throughout August, there was a mix of celebration, confusion, and conflict, mainly caused by the lack of information provided to the Koreans by the Allies. The general public did not become aware of the division of Korea until around when the Soviets entered Pyongyang.<ref name=":02" /> | |||

| However, American leaders were suspicious of the people's committees forming all over the peninsula, and suspected that without American intervention, the whole peninsula would elect to come under Communist government and Soviet influence. Soviet forces arrived in Korea first, but occupied only the northern half, stopping at the 38th parallel, per the agreement with the United States.<ref>{{cite book|title=A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present|first=Michael J.|last=Seth|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield|year=2010}}</ref> | |||

| Meanwhile in Seoul, beginning in early to mid August, General ], the last Japanese ], began contacting Koreans to offer them a leading role in the hand-over of power. He first offered the position to ], the former head of '']'' newspaper, who was seen as a champion of Korean independence activism within the peninsula. Song refused the position, which he saw as equivalent to the role of ], the ruler of the ] in China. He instead preferred to wait until, as many expected and hoped, the KPG returned to the peninsula and established a fully domestic Korean government. On 15 August, Abe instead offered the position to ], who accepted it, to the chagrin of Song. That day, Lyuh announced to the public that Japan had accepted the terms of surrender laid out in the ], to the jubilation of the Koreans and the horror of the around 777,000 Japanese residents of the peninsula. With a budget of 20,000,000 yen from the colonial government, Lyuh set about organizing the {{ill|Committee for the Preparation of Korean Independence|ko|조선건국준비위원회}} (CPKI). The CPKI began taking over the security situation in the city and coordinating with local governments throughout the peninsula. However, the organization ended up being composed of mostly left-leaning communists, which infuriated Song even more. Lyuh attempted on multiple occasions to convince Song to join or support the CPKI, but their meetings reportedly ended in angry arguments each time.<ref name=":02">{{Cite web |last=Son |first=Sae-il |date=2010-03-29 |title=孫世一의 비교 評傳 (73) |trans-title=Son Sae-il's Comparative Critical Biography |url=http://monthly.chosun.com/client/news/viw.asp?ctcd=I&nNewsNumb=201004100072 |access-date=2023-07-25 |website=] |language=ko}}</ref> | |||

| On August 10, 1945 two young officers – ] and ] – were assigned to define an American occupation zone. Working on extremely short notice and completely unprepared, they used a '']'' map to decide on the 38th parallel. They chose it because it divided the country approximately in half but would leave the capital ] under American control. No experts on Korea were consulted. The two men were unaware that forty years before, Japan and ] had discussed sharing Korea along the same parallel. Rusk later said that had he known, he "almost surely" would have chosen a different line.<ref>Oberdorfer, Don. ''The Two Koreas.'' Basic Books, p. 6.</ref> Regardless, the decision was hastily written into ] for the administration of postwar Japan. | |||

| For the weeks before the American arrival in Seoul, the capital was awash with waves of rumors, some of which may have been spread by Japanese soldiers to distract the public while they prepared to leave the peninsula. On multiple occasions, rumors that Soviet soldiers were about to arrive via rail to Seoul caused either mass panic or, for some left-leaning Koreans, celebration. Even the Soviet Ambassador in Seoul was confused and phoned around to check whether Soviet soldiers were coming. Another rumor, spread both by fliers and a pirate radio broadcast, alleged the creation of a "]" ({{Korean|hangul=동진공화국|hanja=東震共和國|labels=no}}), with ] as president, ] as prime minister, ] as minister of military affairs, and Lyuh as foreign minister.<ref name=":02" /> | |||

| General ], the last Japanese ], had been in contact with a number of influential Koreans since the beginning of August 1945 to prepare the hand-over of power. On August 15, 1945, ], a moderate left-wing politician, agreed to take over. He was in charge of preparing the creation of a new country and worked hard to build governmental structures. On September 6, 1945, a congress of representatives was convened in Seoul. The foundation of a modern Korean state took place just three weeks after Japan's capitulation. The government was predominantly left wing; many of those who had resisted Japanese rule identified with ]'s views on imperialism and colonialism. | |||

| On 16 August, young officers of the Japanese military in Seoul fiercely protested the decisions of the colonial government. Despite assurances from the colonial government to the CPKI of minimal interference from the Japanese in their affairs, the military declared that they would firmly punish any unrest, to the protest of the CPKI.<ref name=":02" /> | |||

| ==Post World War II== | |||

| On 6 September a congress of representatives was convened in Seoul and founded the short-lived ] (PRK).<ref>{{cite book| title = The Making of Modern Korea | last = Buzo | first = Adrian | year = 2002| publisher = Routledge| location = London | isbn = 978-0-415-23749-9 |pages=53–57}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | title = Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey | url = https://archive.org/details/koreastwentieth00robi/page/105 | url-access = registration | last = Robinson | first = Michael E | year = 2007 | publisher = University of Hawaii Press | location = Honolulu | isbn = 978-0-8248-3174-5 | pages = }}</ref> In the spirit of consensus, conservative elder statesman Syngman Rhee, who was living in exile in the U.S., was nominated as president.<ref name="auto6">{{cite news|url=https://www.nknews.org/2018/08/why-russian-plans-for-austria-style-unification-in-korea-did-not-become-a-reality|title=Why Soviet plans for Austria-style unification in Korea did not become a reality|first=Fyodor|last=Tertitskiy|publisher=]|date=8 August 2018|access-date=15 November 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181115195117/https://www.nknews.org/2018/08/why-russian-plans-for-austria-style-unification-in-korea-did-not-become-a-reality|archive-date=15 November 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> Song announced his own {{Ill|National Foundation Preparation Committee|ko|국민대회준비위원회}} (NFPC) on 7 September to directly counter the PRK. However, the NFPC had a minimal role in Korean politics and ended up aligning itself with the KPG after its return.<ref name="enjk">{{cite web |last=송 |first=남헌 |title=송진우 (宋鎭禹) |trans-title=Song Jin-woo |url=https://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Article/E0031073 |access-date=2023-07-24 |website=]}}</ref> | |||

| ===South Korea=== | |||

| {{Main|United States Army Military Government in Korea}} | |||

| {{See also|People's Republic of Korea|Autumn Uprising of 1946|Jeju Uprising|Yeosu–Suncheon Rebellion}} | |||

| ] giving a speech in the Committee for Preparation of Korean Independence in ] on August 16, 1945.|left]] | |||

| ==Post–World War II== | |||

| On September 7, 1945, General ] announced that Lieutenant General ] was to administer Korean affairs, and Hodge landed in ] with his troops the next day. The troops occupied Southern Korea and took over comfort stations, then many women in comfort stations began working as a ].<ref name="Cho94">{{cite book |last= Cho |first= Grace |title= Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War |url=http://books.google.co.kr/books?id=VagzEDjnZpcC&pg=PA103&dq=yanggongju+caste&hl=en&sa=X&ei=U2llUdCaL4ftkgX0rYCABw&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=yanggongju%20caste&f |publisher= ] |year=2008 |ISBN= 0816652759 |page= 94}}</ref> | |||

| ===Division (since 2 September 1945)=== | |||

| ====Soviet occupation of northern Korea==== | |||

| The Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea sent a delegation with three interpreters, but Hodge refused to meet with them and refused to recognize the ] or the ].<ref name="Hart-Landsberg 1998 71–77">{{cite book |last=Hart-Landsberg |first=Martin |title=Korea: Division, Reunification, & U.S. Foreign Policy |year=1998 |publisher=Monthly Review Press |pages=71–77}}</ref> In September 1946, ] against the Allied Military Government. This uprising was quickly defeated, and failed to prevent scheduled October elections for the South Korean Interim Legislative Assembly. The U.S. military has maintained a presence on the ] through to the present day. | |||

| {{Further|Soviet Civil Administration|Provisional People's Committee for North Korea}} | |||

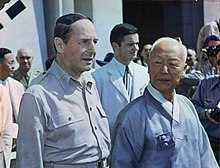

| ] in ] on 14 October 1945]] | |||

| The Soviets received little resistance from the Japanese during their advance across northern Korea and were aided by various Korean groups.<ref name="Cumings">{{Cite web|last=Cumings|first=Bruce|title=The North Wind: The Origins of the Korean War|url=http://faculty.washington.edu/sangok/NorthKorea/Cumings,_Bruce_-_The_North_Wind.pdf}}</ref> When Soviet troops entered ] on August 24, they found a local branch of the Committee for the Preparation of Korean Independence operating under the leadership of veteran nationalist ].<ref>{{cite book| title = The Making of Modern Korea | last = Buzo | first = Adrian | year = 2002| publisher = Routledge| location = London | isbn = 978-0-415-23749-9 |pages=54–55}}</ref> The Soviet Army allowed these "People's Committees" (which were of varying political composition) to function. In September 1945, the Soviet administration issued its own currency, the "Red Army won".<ref name="auto5" /> | |||

| ] | |||

| The former President of the ], the government-in-exile in Shanghai, and ardent anti-communist ], was considered an acceptable candidate to provisionally lead the country since he was considered friendly to the US, having traveled and studied stateside. Under Rhee, the southern government conducted a number of military campaigns against left-wing insurgents who took up arms against the government and persecuted other political opponents. Over the course of the next few years, between 30,000<ref>Arthur Millet, ''The War for Korea, 1945–1950'' (2005).</ref> and 100,000 people would lose their lives during the war against the left-wing insurgents.<ref>Jon Halliday and Bruce Cumings, ''Korea: The Unknown War'', Viking Press, 1988, ISBN 0-670-81903-4.</ref> | |||

| As a result of the destruction caused to the Soviet Union during the Second World War, the Soviets lacked the resources and will to create a full ] in Korea and Koreans enjoyed a higher level of autonomy than Soviet-controlled Eastern European states. The Soviets had brought with them a number of Koreans who had been living in the Soviet Union, some of whom were members of the Soviet Communist Party, with the intention of creating a socialist state.<ref name="Cumings" /> Unlike in the south, the former Japanese occupying authorities offered virtually no assistance to the Soviets, and even destroyed factories, mines and official records.<ref name="Cumings" /> | |||

| In April, 1948, ] against South Korean officials, and South Korea sent troops to repress the rebellion. Tens of thousands of islanders were killed and by one estimate, 70% of the villages were burned by the South Korean troops.<ref name=nw000619>{{cite news | |||

| |url=http://www.newsweek.com/2000/06/18/ghosts-of-cheju.html | |||

| |title=Ghosts of Cheju | |||

| |newspaper = ] | |||

| |date = 2000-06-19 | |||

| |accessdate = 2012-09-02 | |||

| }}</ref> The uprising lasted until the end of the Korean War. | |||

| After the massive loss of troops in Europe, the Soviet army recruited new soldiers, who were badly equipped when they landed in Korea, some even lacking shoes and uniforms. During the Soviet occupation, they lived off the Korean land, and looted Japanese colonials and Korean capitalists, sending part of the loot back home. In addition to looting, Soviet soldiers were accused of rape, although the accusations were inflated in the south by fleeing Japanese colonials. Korean peasants sometimes joined the looting, indicating that the looting was based in class disparities, rather than racial disparities. These abuses lessened after the arrival of ] in January 1946.<ref name="Cumings1981" /> On the southern peninsula, American soldiers also committed depredations, both rape and looting, on a smaller scale than the Soviets. The racism amongst Americans against Koreans, however, was widespread.<ref name="Cumings1981" /> | |||

| In August 1948, Syngman Rhee became the first president of ]. In October 1948, the ] took place, in which some regiments rejected the suppression of the Jeju uprising and rebelled against the government.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/332032.html|title=439 civilians confirmed dead in Yeosu-Suncheon Uprising of 1948 New report by the Truth Commission places blame on Syngman Rhee and the Defense Ministry, advises government apology|publisher=] |date=8 January 2009|accessdate=2 September 2012}}</ref> In 1949, the Syngman Rhee government established the ] in order to keep an eye on its political opponents. The majority of the Bodo League's members were innocent farmers and civilians who were forced into membership.<ref>{{cite news | |||

| |url=http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2009/03/117_40555.html | |||

| |title= Gov’t Killed 3,400 Civilians During War | |||

| |newspaper = ] | |||

| |date = 2 March 2009 | |||

| |accessdate = 19 October 2014 | |||

| }}</ref> The registered members or their families were executed at the beginning of the Korean War. On December 24, 1949, South Korean Army ] who were suspected communist sympathizers or their family and affixed blame to communists.<ref>{{cite news | |||

| |url=http://www.ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/view/at_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0001070694 | |||

| |script-title=ko:두 민간인 학살 사건, 상반된 판결 왜 나왔나?'울산보도연맹' – '문경학살사건' 판결문 비교분석해 봤더니... | |||

| |newspaper = ] | |||

| |date = 2009-02-17 | |||

| |accessdate = 2012-09-02 | |||

| |language=ko}}</ref> | |||

| In 1946, Colonel-General ] took charge of the administration and began to lobby the Soviet government for funds to support the ailing economy.<ref name="auto5" /> Shtykov's strong support of Kim Il Sung, who had spent the last years of the war training with Soviet troops in ], was decisive in his rise to power.<ref name="Lankov2" /> In February 1946 a ] called the ] was formed under Kim Il Sung. Conflicts and power struggles ensued at the top levels of government in Pyongyang as different aspirants manoeuvred to gain positions of power in the new government.<ref name="Robinson" /> | |||

| ===North Korea=== | |||

| {{Main|Provisional People's Committee for North Korea}} | |||

| ] in ] on 14 October 1945.]] | |||

| In December 1946, Shtykov and two other generals designed the election results of the Assembly for the Provisional Committee without any Korean input. The generals decided "exact distribution of seats among the parties, the number of women members, and, more broadly, the precise social composition of the legislature."<ref name="Lankov2">{{cite book|last=Lankov|first=Andrei|date=2013-04-10|title=]|page=7|publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref> The original 1948 ] was primarily written by Stalin and Shtykov.<ref name="Lankov2" /> | |||

| Throughout August, Koreans organized the country into people's committee branches for the "Committee for the Preparation of Korean Independence" (CPKI, 조선건국준비위원회). The Soviet Army allowed for these committees to continue to function since they were friendly to the ], but still established the ''Soviet Civil Authority'' to begin to centralize the independent committees. Further provisional committees were set up across the country putting Communists into key positions. In March 1946 land reform was instituted as the land from Japanese and collaborator land owners was divided and handed over to poor farmers. ] initiated a sweeping land reform program in 1946. | |||

| Organizing the many poor civilians and agricultural |

In March 1946 the provisional government instituted a sweeping land-reform program: land belonging to Japanese and collaborator landowners was divided and redistributed to poor farmers.<ref name="Robinson">{{cite book| title = Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey | url = https://archive.org/details/koreastwentieth00robi | url-access = registration | last = Robinson | first = Michael E | year = 2007 | publisher = University of Hawaii Press | location = Honolulu | isbn = 978-0-8248-3174-5 |page=}}</ref> Organizing the many poor civilians and agricultural labourers under the people's committees, a nationwide mass campaign broke the control of the old landed classes. Landlords were allowed to keep only the same amount of land as poor civilians who had once rented their land, thereby making for a far more equal distribution of land. The North Korean land reform was achieved in a less violent way than ] or ]. Official American sources stated: "From all accounts, the former village leaders were eliminated as a political force without resort to bloodshed, but extreme care was taken to preclude their return to power."<ref name="Cumings1981">{{cite book |last=Cumings |first=Bruce |title=The Origins of the Korean War: Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regimes, 1945–1947 |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=1981 |isbn=0-691-09383-0 |pages=390}}</ref> The farmers responded positively; many collaborators, former landowners and Christians fled to the south, where some of them obtained positions in the new South Korean government. According to the U.S. military government, 400,000 northern Koreans went south as refugees.<ref>{{cite book | first=Allan R. | last=Millet | title=The War for Korea: 1945–1950 | year=2005 | page=59}}</ref> | ||

| Key industries were nationalized. The economic situation was nearly as difficult in the north as it was in the south, as the Japanese had concentrated agriculture in the south and heavy industry in the north. | Key industries were nationalized. The economic situation was nearly as difficult in the north as it was in the south, as the Japanese had concentrated agriculture and service industries in the south and heavy industry in the north.{{Confusing-inline|date=November 2023|reason=did they mean wasn't nearly as difficult, instead of, economic situation was nearly as difficult. This is referring to the 2nd to last paragraph}} | ||

| Soviet forces were withdrawn on 10 December 1948.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| In February 1946 a ] called the Provisional People's Committee was formed under ], who had spent the last years of the war training with Soviet troops in ]. Conflicts and power struggles rose up at the top levels of government in Pyongyang as different aspirants maneuvered to gain positions of power in the new government. At the local levels, people's committees openly attacked collaborators and some landlords, confiscating much of their land and possessions. As a consequence many collaborators and others disappeared or were assassinated. Soviet forces departed in 1948.{{Citation needed|date=December 2010}} | |||

| |last1 = Gbosoe | |||

| |first1 = Gbingba T. | |||

| |title = Modernization of Japan | |||

| |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=qfnP-Za9FwEC | |||

| |publisher = iUniverse | |||

| |publication-date = 2006 | |||

| |page = 212 | |||

| |isbn = 9780595411900 | |||

| |access-date = 2015-10-06 | |||

| |quote = Although Soviet occupation forces were withdrawn on December 10, 1948, the Soviets had maintained ties with the Democratic People's Republic of Korea | |||

| |date = September 2006 | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160428033822/https://books.google.com/books?id=qfnP-Za9FwEC | |||

| |archive-date = 28 April 2016 | |||

| |url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ====US occupation of southern Korea==== | |||

| ===Elections and UN intervention=== | |||

| {{Main|United States Army Military Government in Korea}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] in ] on 9 September 1945]] | |||

| With mistrust growing rapidly between the formerly allied United States and Soviet Union, no agreement was reached on how to reconcile the competing provisional governments. The U.S. brought the problem before the ] in the fall of 1947. The Soviet Union opposed UN involvement. | |||

| With the American government fearing Soviet expansion, and the Japanese authorities in Korea warning of a power vacuum, the embarkation date of the US occupation force was brought forward three times.<ref name="Cumings2005" /> On 7 September 1945, ] issued Proclamation No. 1 to the people of Korea, announcing U.S. military control over Korea south of the 38th parallel and establishing English as the official language during military control.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, 1945, The British Commonwealth, The Far East, Volume VI - Office of the Historian |url=https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1945v06/d776 |access-date=2022-06-23 |website=history.state.gov}}</ref> That same day, he announced that Lieutenant General ] was to administer Korean affairs. Hodge landed in ] with his troops on 8 September 1945, marking the beginning of the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK). | |||

| MacArthur as ] ended up being in charge of ] from 1945 to 1948 due to the lack of clear orders or initiative from Washington, D.C. There was no plan or guideline given to MacArthur from the ] or the ] on how to rule Korea. Hodge directly reported to MacArthur and GHQ (General Headquarters) in Tokyo, not to Washington, D.C., during the military occupation. The ] of the U.S. Army occupation was chaotic and tumultuous compared to the very peaceful and stable ] from 1945 to 1952. Hodge and his ] were trained for combat, not for diplomacy and negotiating with the many diverse political groups that emerged in post-colonial southern Korea: former Japanese collaborators, pro-Soviet communists, anti-Soviet communists, right wing groups, and Korean nationalists. None of the Americans in the military or the State Department in the Far East in late 1945 even spoke Korean, leading to jokes among Koreans that Korean translators were really running southern Korea.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/MacArthur%20Reports/MacArthur%20V1%20Sup/ch3.htm |title=Reports of General MacArthur: MacArthur in Japan: The Occupation: Military Phase: Volume 1 Supplement|access-date=26 March 2021|at=Chapter III}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://history.army.mil/books/pd-c-02.htm |title=CHAPTER II:The House Divided |website=history.army.mil |access-date=26 March 2021}}</ref> The ], which had operated from China, sent a delegation with three interpreters to Hodge, but he refused to meet with them.<ref name="Hart-Landsberg 1998 71–77">{{cite book |last=Hart-Landsberg |first=Martin |title=Korea: Division, Reunification, & U.S. Foreign Policy |url=https://archive.org/details/korea00mart |url-access=registration |year=1998 |publisher=Monthly Review Press |pages=}}</ref> Likewise, Hodge refused to recognize the newly formed ] and its People's Committees, and outlawed it on 12 December.<ref>{{cite book| title = The Making of Modern Korea | last = Buzo | first = Adrian | year = 2002| publisher = Routledge| location = London | isbn = 978-0-415-23749-9 |page=57}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The UN passed a resolution on November 14, 1947, declaring that free elections should be held, foreign troops should be withdrawn, and a UN commission for Korea, ], should be created. The ], although a member with veto powers, boycotted the voting and did not consider the resolution to be binding. In April 1948, a conference of organizations from the north and the south met in ]. This conference produced no results, and the Soviets boycotted the UN-supervised elections in the south. There was no UN supervision of elections in the north. | |||

| Japanese civilians were repatriated, including nearly all industrial managers and technicians; over 500,000 by December 1945 and 786,000 by August 1946. Severe price inflation occurred in the disrupted economy, until in summer 1946 ] and ] were imposed.<ref name="mccune-194703">{{cite journal |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2752411 |title=Korea: The First Year of Liberation |author=George M. McCune |journal=Pacific Affairs |volume=20 |issue=1 |publisher=University of British Columbia |doi=10.2307/2752411 |date=March 1947 |pages=3–17 |jstor=2752411 |access-date=5 January 2022}}</ref> | |||

| On May 10, 1948 the south held a ]. On August 15, the "]" formally took over power from the U.S. military. In the North, the "]" was declared on September 9, with ] as prime minister. | |||

| In September 1946, ] against the military government. This uprising was quickly defeated, and failed to prevent scheduled ] for the South Korean Interim Legislative Assembly. The opening of the Assembly was delayed to December to investigate widespread allegations of electoral fraud.<ref name="mccune-194703" /> | |||

| ==Korean War== | |||

| {{Main|Korean War}} | |||

| Ardent anti-communist ], who had been the first president of the Provisional Government and later worked as a pro-Korean lobbyist in the US, became the most prominent politician in the South. Rhee pressured the American government to abandon negotiations for a trusteeship and create an independent Republic of Korea in the south.<ref>{{cite book|last=Stueck |first=William W. |year=2002 |title=Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History |url=https://archive.org/details/rethinkingkorean0000stue |url-access=registration |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=Princeton, NJ |isbn=978-0-691-11847-5|pages=, 55–57}}</ref> On 19 July 1947, ], the last senior politician committed to left-right dialogue, was assassinated by a 19-year-old man named Han Chigeun, a recent refugee from North Korea and an active member of the nationalist right-wing group, the ].<ref>{{cite book| title = The Making of Modern Korea | last = Buzo | first = Adrian | year = 2002| publisher = Routledge| location = London | isbn = 978-0-415-23749-9 |page=65}}</ref> | |||

| This division of Korea, after more than a millennium of being unified, was seen as controversial and temporary by both regimes. From 1948 until the start of the civil war on June 25, 1950, the armed forces of each side engaged in a series of bloody conflicts along the border. In 1950, these conflicts escalated dramatically when North Korean forces invaded South Korea, triggering the ]. The ] was signed three years later ending hostilities and effectively making the division permanent. The two sides agreed to create a four-kilometer wide buffer zone between the states, where nobody would enter. This area came to be known as the ]. | |||

| USAMGIK and later the newly formed South Korean government faced a number of left-wing insurgencies, some supported by North Korea, that were eventually suppressed. Over the course of the next few years, between 30,000<ref>{{cite book | first=Arthur | last=Millet | title=The War for Korea, 1945–1950 | year=2005}}</ref> and 100,000 people were killed. Most casualties resulted from the ].<ref>{{cite book|first1=Jon|last1=Halliday|first2=Bruce|last2=Cumings|title=Korea: The Unknown War|publisher=Viking Press|year=1988|isbn=0-670-81903-4}}</ref> | |||

| ===Geneva Conference and NNSC=== | |||

| As dictated by the terms of the Korean Armistice, a ] was held in 1954 on the Korean question. Despite efforts by many of the nations involved, the conference ended without a declaration for a unified Korea. | |||

| ===US–Soviet Joint Commission=== | |||

| The Armistice established a ] (NNSC) which was tasked to monitor the Armistice. Since 1953, members of the Swiss<ref> {{dead link|date=October 2014}}</ref> and Swedish<ref> {{dead link|date=October 2014}}</ref> Armed Forces have been members of the NNSC stationed near the DMZ. | |||

| ] | |||

| In December 1945, at the ], the Allies agreed that the Soviet Union, the US, the Republic of China, and Britain would take part in a ] over Korea for up to five years in the lead-up to independence. This invigorated the {{Ill|Anti-trusteeship Movement|ko|신탁 통치 반대 운동}}, which demanded the immediate independence of the peninsula. However, the ], which was closely aligned with the Soviet Communist party, supported the trusteeship.<ref>{{cite book| title = The Making of Modern Korea | last = Buzo | first = Adrian | year = 2002| publisher = Routledge| location = London | isbn = 978-0-415-23749-9 |page=59}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | title = Korea| last = Bluth | first = Christoph | year = 2008| publisher = Polity Press| location = Cambridge| isbn = 978-07456-3357-2 |page=12}}</ref> According to historian Fyodor Tertitskiy, documentation from 1945 suggests the Soviet government initially had no plans for a permanent division.<ref name="auto6" /> | |||

| A {{ill|Soviet-US Joint Commission|ko|미소공동위원회}} met in 1946 and 1947 to work towards a unified administration, but failed to make progress due to increasing ] antagonism and to Korean opposition to the trusteeship.<ref>{{cite book| title = The Making of Modern Korea | last = Buzo | first = Adrian | year = 2002| publisher = Routledge| location = London | isbn = 978-0-415-23749-9 |pages=59–60, 65}}</ref> In 1946, the Soviet Union proposed ] as the leader of a unified Korea, but this was rejected by the US.<ref name="auto6"/> Meanwhile, the division between the two zones deepened. The difference in policy between the occupying powers led to a polarization of politics, and a transfer of population between North and South.<ref>{{cite book | title = Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey | url = https://archive.org/details/koreastwentieth00robi/page/108 | url-access = registration | last = Robinson | first = Michael E | year = 2007 | publisher = University of Hawaii Press | location = Honolulu | isbn = 978-0-8248-3174-5 | pages = }}</ref> In May 1946 it was made illegal to cross the 38th parallel without a permit.<ref name="auto2">{{cite book |author= Hyung Gu Lynn |date= 2007 |title= Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989 |publisher= Zed Books |page=20}}</ref> At the final meeting of the Joint Commission in September 1947, Soviet delegate ] proposed that both Soviet and US troops withdraw and give the Korean people the opportunity to form their own government. This was rejected by the US.<ref>{{cite book|title = Korea: Where the American Century Began|last = Pembroke| first = Michael|year = 2018| publisher = Hardie Grant| location = Melbourne| isbn = 978-1-74379-393-0|page=43}}</ref> | |||

| ==Post-Armistice Inter-Korean Relations== | |||

| {{POV-section|reason=A lot of rhetoric and super anti-north biass|date=April 2013}} | |||

| {{Main|North Korea–South Korea relations}} | |||

| ===UN intervention and the formation of separate governments=== | |||

| Although the truce seemingly ended the war between North and South Korea, it is often regarded as a truce in name only. This proved to be especially true after the attack of ], the world has their eyes on North Korea's next move, and two Koreas' tension has flared{{By whom|date=April 2013}} since then. The incident chilled inter-Korean relations and seemed to freeze all exchanges between the two Koreas. As soon as the investigation team revealed that the Cheonan was sunk by North Korea, President Lee implemented countermeasures called the May 24 Measures. The South Korean government suspended all inter-Korean exchanges and cooperation with the North, except for business operations in the Kaeseong Industrial Complex and the pure humanitarian aid for the underprivileged people in North Korea. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] to President Syngman Rhee on 15 August 1948]] | |||

| With the failure of the Joint Commission to make progress, the US brought the problem before the ] in September 1947. The Soviet Union opposed UN involvement.<ref>{{cite book | title = Korea since 1850 | last1 = Lone | first1 = Stewart| last2 = McCormack | first2 = Gavan | author-link2 = Gavan McCormack | publisher = Longman Cheshire | location = Melbourne | year = 1993 | pages=100–101 }}</ref> The UN passed a resolution on 14 November 1947, declaring that free elections should be held, foreign troops should be withdrawn, and a UN commission for Korea, the ] (UNTCOK), should be created. The Soviet Union boycotted the voting and did not consider the resolution to be binding, arguing that the UN could not guarantee fair elections. In the absence of Soviet co-operation, it was decided to hold UN-supervised elections in the south only.<ref>{{cite book| title = The Making of Modern Korea | last = Buzo | first = Adrian | year = 2002| publisher = Routledge| location = London | isbn = 978-0-415-23749-9 |page=66}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | last = Jager | first = Sheila Miyoshi| author-link= Sheila Miyoshi Jager | title = Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea | year = 2013 | publisher = Profile Books | location = London | isbn = 978-1-84668-067-0|page=47}}</ref> This was in defiance of the report of the chairman of the commission, ], who had argued against a separate election.<ref>{{cite book|title = Korea: Where the American Century Began|last = Pembroke| first = Michael|year = 2018| publisher = Hardie Grant| location = Melbourne| isbn = 978-1-74379-393-0|page=45}}</ref> Some UNTCOK delegates felt that the conditions in the south gave unfair advantage to right-wing candidates, but they were overruled.<ref name=Cumings2005/>{{rp|211–212}} | |||

| The Korean peninsula, in the end, became a continuous battlefield without an official declaration of peace. With the South Korean conscription act and North Korea maintaining the largest standing army, it is very obvious that the threat of war remains in the air between North and South Korean politics. With the armistice, there was no official statement of which political ideology was right. As a result, both countries were determined to keep their ideology going strong. For example, the North Koreans saw themselves as the "true" Koreans and would refuse unification unless a Communist regime was accepted <ref>Jager, Sheila Miyoshi. Brothers At War: The Unending Conflict in Korea. 1st ed. New York: W. W. Norton &, 2013. Print.</ref> | |||

| The decision to proceed with separate elections was unpopular among many Koreans, who rightly saw it as a prelude to a permanent division of the country. General strikes in protest against the decision began in February 1948.<ref name="auto2"/> In April, ] against the looming division of the country and full-scale rebellion developed. South Korean troops were sent to repress the rebellion. The repression of the uprising escalated from August 1948, following South Korean independence. The rebellion was largely defeated by May 1949 and 25,000 to 30,000 people had been killed in the conflict,<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|title = The Massacre at Mt. Halla: Sixty Years of Truth Seeking in South Korea|last = Kim|first = Hun Joon|publisher = Cornell University Press|year = 2014|isbn = 9780801452390|pages = 13–41}}</ref> and 70% of the villages were burned by the South Korean troops.<ref name=nw000619>{{cite news | |||

| There is a great deal of skepticism{{citation needed|date=April 2013}} towards North-South Korea relations. Economically, it is commonly alleged {{By whom|date=April 2013}} that the South provides a great deal of support to the North whilst receiving nothing in return.{{citation needed|date=April 2013}} However, compared to the previous South Korean government or the former West German aid to East Germany, the Kim Dae Jung administration's assistance to North Korea has been rather minuscule. The aid to North Korea in the year 2000 was only .017 percent of South Korea's GDP, less than one-fourth of the former West Germany's annual aid to East Germany.<ref>Kurt M. Campbell, Vice President, Center for Strategic and International Studies, and Alton Frye, Senior Fellow, Council on Foreign Relations June 12, 2002. Council on Foreign Relations</ref> While it may seem low, it must be remembered that during the year 2000, much of the South Korean government had considered the Sunshine Policy as dead. Beginning in 1998, the South Korean president ] has made efforts to reunify the Korean peninsula by creating the ]. This policy was meant to ease tensions between South Korea and North Korea after so many years after the Korean War. It initially was meant so that instead of treating North Korea like a caged animal, South Korea and North Korea would work together and discuss any issues within the peninsula <ref>Cha, Victor. The Impossible State: North Korea, Past And Future. New York: HarperCollins, 2012. Print.</ref> However, the South Korean government has recently stated that the nuclear arms program in North Korea has killed the Sunshine Policy.<ref>Jager, Sheila Miyoshi. Brothers At War: The Unending Conflict in Korea. 1st ed. New York: W.W. Norton &, 2013. Print.</ref> As such, the South Korean government no longer desires cooperation with North Korea since North Korea refused to meet all its demands. | |||

| |url = http://www.newsweek.com/2000/06/18/ghosts-of-cheju.html | |||

| |title = Ghosts of Cheju | |||

| |newspaper = ] | |||

| |date = 2000-06-19 | |||

| |access-date = 2012-09-02 | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110615112530/http://www.newsweek.com/2000/06/18/ghosts-of-cheju.html | |||

| |archive-date = 2011-06-15 | |||

| |url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> The uprising flared up again with the outbreak of the Korean War.<ref>{{cite book | title = Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey | url = https://archive.org/details/koreastwentieth00robi/page/112 | url-access = registration | last = Robinson | first = Michael E | year = 2007 | publisher = University of Hawaii Press | location = Honolulu | isbn = 978-0-8248-3174-5 | pages = }}</ref> | |||

| In April 1948, a conference of organizations from the north and the south met in ]. The southern politicians ] and ] attended the conference and boycotted the elections in the south, as did other politicians and parties.<ref name=Cumings2005/>{{rp|211,507}}<ref>{{cite book | last = Jager | first = Sheila Miyoshi | title = Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea | year = 2013 | publisher = Profile Books | location = London | isbn = 978-1-84668-067-0|pages=47–48}}</ref> The conference called for a united government and the withdrawal of foreign troops.<ref name="auto3">{{cite book|title = Korea: Where the American Century Began|last = Pembroke| first = Michael|year = 2018| publisher = Hardie Grant| location = Melbourne| isbn = 978-1-74379-393-0|page=46}}</ref> Syngman Rhee and General Hodge denounced the conference.<ref name="auto3"/> Kim Koo was assassinated the following year.<ref>{{cite book | last = Jager | first = Sheila Miyoshi | title = Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea | year = 2013 | publisher = Profile Books | location = London | isbn = 978-1-84668-067-0|pages=48, 496}}</ref> | |||

| On July 7, 1988, with the announcement of the Presidential Declaration for National Self-esteem Unification and Prosperity, South and North Korea officially promoted inter-Korean exchanges and cooperation. These exchanges halted temporarily when North Korea withdrew from the NPT in March 1993, but it eventually resumed its course and remains in effect to the present day. Up until 1989, only one person crossed the border but that number has increased over the years and now stands at 130,000. Inter-Korean trade recorded 19 million US dollars in 1989 but it reached 1.9 billion US dollars in 2010. Additionally, the total amount of humanitarian aid from 1995 to late 2010 equals approximately 2.9 billion US dollars. | |||

| On 10 May 1948 the south held a ]. It took place amid widespread violence and intimidation, as well as a boycott by opponents of Syngman Rhee.<ref name="auto4">{{cite book|title = Korea: Where the American Century Began|last = Pembroke| first = Michael|year = 2018| publisher = Hardie Grant| location = Melbourne| isbn = 978-1-74379-393-0|page=47}}</ref> On 15 August, the "]" (''Daehan Minguk'') formally took over power from the U.S. military, with Syngman Rhee as the first president. USAMGIK was formally dissolved and the ] was formed to train and provide support for the South Korean army. U.S forces started to withdraw in a process that was completed by 1949. In the North, the "]" (''Chosŏn Minjujuŭi Inmin Konghwaguk'') was declared on 9 September, with Kim Il Sung as prime minister. | |||

| The foreign relations that define the place of North and South Korea in the world community today are product of the trajectories.{{Clarify|date=April 2013}} Starting with 1945 nation building process of South Korea led by US, South has been allied with United States whereas North Korea has allied with China and Russia.{{citation needed|date=April 2013}} However with the increasing prosperity of China and its power in the international society, North Korea has limited power in China.<ref>Kim, Samual S. The Two Koreas and The Great Powers. 2006 Cambridge University Press.</ref> | |||

| On 12 December 1948, the United Nations General Assembly accepted the report of UNTCOK and declared the Republic of Korea to be the "only lawful government in Korea".<ref>{{cite book| title = The Making of Modern Korea | last = Buzo | first = Adrian | year = 2002| publisher = Routledge| location = London | isbn = 978-0-415-23749-9 |page=67}}</ref> However, none of the members of UNTCOK considered that the election had established a legitimate national parliament. The Australian government, which had a representative on the commission declared that it was "far from satisfied" with the election.<ref name="auto4"/> | |||

| ==Post division of Korea incidents== | |||

| Since the division of Korea, there have been numerous instances of infiltration and incursions across the border largely by North Korean agents, although the North Korean government never acknowledges direct responsibility for any of these incidents. A total of 3,693 armed North Korean agents have infiltrated into South Korea between 1954 to 1992, with 20% of these occurring between 1967 and 1968.<ref>. Retrieved 2010-01-15.</ref> According to the 5 January 2011 '']'', since July 1953 North Korea has violated the armistice 221 times, including 26 military attacks.<ref>'']'', "N.K. Commits 221 Provocations Since 1953", 5 January 2011.</ref> | |||

| Unrest continued in the South. In October 1948, the ] took place, in which some regiments rejected the suppression of the Jeju uprising and rebelled against the government.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/332032.html|title=439 civilians confirmed dead in Yeosu-Suncheon Uprising of 1948 New report by the Truth Commission places blame on Syngman Rhee and the Defense Ministry, advises government apology|publisher=]|date=8 January 2009|access-date=2 September 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110511184103/http://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/332032.html|archive-date=11 May 2011|url-status=live}}</ref> In 1949, the Syngman Rhee government established the ] in order to keep an eye on its political opponents. The majority of the Bodo League's members were innocent farmers and civilians who were forced into membership.<ref>{{cite news | |||

| In 1976, in now declassified meeting minutes, U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense ] told ] that there had been 200 raids or incursions into North Korea from the south, though not by the U.S. military.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76ve12/d286 |title=Minutes of Washington Special Actions Group Meeting, Washington, August 25, 1976, 10:30 a.m. |date=25 August 1976 |accessdate=12 May 2012 |publisher=], U.S. Department of State |quote=Clements: I like it. It doesn't have an overt character. I have been told that there have been 200 other such operations and that none of these have surfaced. Kissinger: It is different for us with the War Powers Act. I don't remember any such operations.}}</ref> Details of only a few of these incursions have become public, including raids by South Korean forces in 1967 that had sabotaged about 50 North Korean facilities.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2011/02/116_80936.html |title=S. Korea raided North with captured agents in 1967 |publisher=The Korea Times |author=Lee Tae-hoon |date=7 February 2011 |accessdate=12 May 2012}}</ref> | |||

| |url=https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2009/03/117_40555.html | |||

| |title=Gov't Killed 3,400 Civilians During War | |||

| |newspaper=] | |||

| |date=2 March 2009 | |||

| |access-date=19 October 2014 | |||

| |url-status=dead | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121004181846/http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2009/03/117_40555.html | |||

| |archive-date=4 October 2012 | |||

| }}</ref> The registered members or their families were executed at the beginning of the Korean War. On 24 December 1949, South Korean Army ] who were suspected communist sympathizers or their family and affixed blame to communists.<ref>{{cite news | |||

| |url=http://www.ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/view/at_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0001070694 | |||

| |script-title=ko:두 민간인 학살 사건, 상반된 판결 왜 나왔나?'울산보도연맹' – '문경학살사건' 판결문 비교분석해 봤더니... | |||

| |newspaper=] | |||

| |date=2009-02-17 | |||

| |access-date=2012-09-02 | |||

| |language=ko | |||

| |url-status=dead | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110503211146/http://www.ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/view/at_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0001070694 | |||

| |archive-date=2011-05-03 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ==Korean War== | |||

| Some instances of incidents caused by North Korea include: | |||

| {{Main|Korean War}} | |||

| This division of Korea, after more than a millennium of being unified, was seen as controversial and temporary by both regimes. From 1948 until the start of the civil war on 25 June 1950, the armed forces of each side engaged in a series of bloody conflicts along the border. In 1950, these conflicts escalated dramatically when North Korean forces invaded South Korea, triggering the ]. The United Nations intervened to protect the South, sending a US-led force. As it occupied the south, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea attempted to unify Korea under its regime, initiating the nationalisation of industry, land reform, and the restoration of the People's Committees.<ref>{{cite book | title = Korea since 1850 | last1 = Lone | first1 = Stewart| last2 = McCormack | first2 = Gavan | author-link2 = Gavan McCormack | publisher = Longman Cheshire | location = Melbourne | year = 1993 | page=112 }}</ref> | |||

| ], North Korea, 1951]] | |||

| While UN intervention was conceived as restoring the border at the 38th parallel, Syngman Rhee argued that the attack of the North had obliterated the boundary. Similarly UN Commander in Chief, General Douglas MacArthur stated that he intended to unify Korea, not just drive the North Korean forces back behind the border.<ref>{{cite book|last=Stueck |first=William W. |year=2002 |title=Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History |url=https://archive.org/details/rethinkingkorean0000stue |url-access=registration |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=Princeton, NJ |isbn=978-0-691-11847-5|pages=–88}}</ref> However, the North overran 90% of the south until a counter-attack by US-led forces. As the North Korean forces were driven from the south, South Korean forces crossed the 38th parallel on 1 October, and American and other UN forces followed a week later. This was despite warnings from the People's Republic of China that it would intervene if American troops crossed the parallel.<ref>{{cite book|last=Stueck |first=William W. |year=2002 |title=Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History |url=https://archive.org/details/rethinkingkorean0000stue |url-access=registration |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=Princeton, NJ |isbn=978-0-691-11847-5|page=}}</ref> As it occupied the north, the Republic of Korea, in turn, attempted to unify the country under its regime, with the Korean National Police enforcing political indoctrination.<ref name=Cumings2005/>{{rp|281–282}} As US-led forces pushed into the north, China unleashed a counter-attack which drove them back into the south. | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1951, the front line stabilized near the 38th parallel, and both sides began to consider an armistice. Rhee, however, demanded the war continue until Korea was unified under his leadership.<ref>{{cite book|last=Stueck |first=William W. |year=2002 |title=Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History |url=https://archive.org/details/rethinkingkorean0000stue |url-access=registration |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=Princeton, NJ |isbn=978-0-691-11847-5|page=}}</ref> The Communist side supported an armistice line being based on the 38th parallel, but the United Nations supported a line based on the territory held by each side, which was militarily defensible.<ref>{{cite book|last=Stueck |first=William W. |year=2002 |title=Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History |url=https://archive.org/details/rethinkingkorean0000stue |url-access=registration |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=Princeton, NJ |isbn=978-0-691-11847-5|pages=, 180}}</ref> The UN position, formulated by the Americans, went against the consensus leading up to the negotiations.<ref>{{cite book|title=Korea: Where the American Century Began|first=Michael|last=Pembroke|publisher=Hardie Grant Books|date=2018|pages=187–188}}</ref> Initially, the Americans proposed a line that passed through Pyongyang, far to the north of the front line.<ref>{{cite book|title=Korea: Where the American Century Began|first=Michael|last=Pembroke|publisher=Hardie Grant Books|date=2018|page=188}}</ref> The Chinese and North Koreans eventually agreed to a border on the military line of contact rather than the 38th parallel, but this disagreement led to a tortuous and drawn-out negotiating process.<ref>{{cite book|title=Korea: Where the American Century Began|first=Michael|last=Pembroke|publisher=Hardie Grant Books|date=2018|pages=188–189}}</ref> | |||

| ==Armistice== | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] was signed after three years of war. The two sides agreed to create a {{convert|4|km|mi|abbr=off|adj=mid|-wide}} buffer zone between the states, known as the ] (DMZ). This new border, reflecting the territory held by each side at the end of the war, crossed the 38th parallel diagonally. Rhee refused to accept the armistice and continued to urge the reunification of the country by force.<ref>{{cite book|last=Stueck |first=William W. |year=2002 |title=Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History |url=https://archive.org/details/rethinkingkorean0000stue |url-access=registration |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=Princeton, NJ |isbn=978-0-691-11847-5|pages=–193}}</ref> Despite attempts by both sides to reunify the country, the war perpetuated the division of Korea and led to a permanent alliance between South Korea and the U.S., and a permanent U.S. garrison in the South.<ref>{{cite book|last=Stueck |first=William W. |year=2002 |title=Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History |url=https://archive.org/details/rethinkingkorean0000stue |url-access=registration |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=Princeton, NJ |isbn=978-0-691-11847-5|pages=–189}}</ref> | |||

| As dictated by the terms of the Korean Armistice, a ] was held in 1954 on the Korean question. Despite efforts by many of the nations involved, the conference ended without a declaration for a unified Korea. | |||

| The Armistice established a ] (NNSC) which was tasked to monitor the Armistice. Since 1953, members of the Swiss<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.vtg.admin.ch/internet/vtg/en/home/themen/einsaetze/peace/korea.parsys.0003.downloadList.53335.DownloadFile.tmp/nnsc2011e.pdf |title=NNSC in Korea |website=] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110829125634/http://www.vtg.admin.ch/internet/vtg/en/home/themen/einsaetze/peace/korea.parsys.0003.downloadList.53335.DownloadFile.tmp/nnsc2011e.pdf |archive-date=29 August 2011}}</ref> and Swedish<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.forsvarsmakten.se/en/Forces-abroad/Korea-/ |title=Korea |website=] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100825200823/http://www.forsvarsmakten.se/en/Forces-abroad/Korea-/ |archive-date=25 August 2010}}</ref> armed forces have been members of the NNSC stationed near the DMZ. Poland and Czechoslovakia were the neutral nations chosen by North Korea, but North Korea expelled their observers after those countries embraced capitalism.<ref>{{cite book|title=Pacific: The Ocean of the Future|first=Simon|last=Winchester|publisher=William Collins|date=2015|page=185}}</ref> | |||

| ==Post-armistice relations== | |||

| {{main|Korean conflict|North Korea–South Korea relations}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Since the war, Korea has remained divided along the DMZ. North and South have remained in a state of conflict, with the opposing regimes both claiming to be the legitimate government of the whole country. Sporadic negotiations have failed to produce lasting progress towards reunification.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.boston.com/news/globe/editorial_opinion/oped/articles/2005/06/09/koreas_slow_motion_reunification/|title=Korea's slow-motion reunification|publisher=Boston Globe|date=9 June 2005|access-date=2007-08-13|first1=John|last1=Feffer|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070823170140/http://www.boston.com/news/globe/editorial_opinion/oped/articles/2005/06/09/koreas_slow_motion_reunification/|archive-date=23 August 2007|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| On 27 April 2018 North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and South Korean President Moon Jae-in met in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). The ] signed by both leaders called for the end of longstanding military activities near the border and the reunification of Korea.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2018/04/27/the-panmmunjom-declaration-full-text-of-agreement-between-north-korea-and-south-korea/|title=The full text of North and South Korea's agreement, annotated|first=Adam|last=Taylor|date=27 April 2018|via=www.washingtonpost.com|access-date=16 May 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612232536/https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2018/04/27/the-panmmunjom-declaration-full-text-of-agreement-between-north-korea-and-south-korea/|archive-date=12 June 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> {{see also|April 2018 inter-Korean summit}} | |||

| ===Land border incidents=== | |||

| Between 1966 and 1969, a series of ] occurred. Other incidents after 1969 include the following: | |||

| * April 1970: Three North Korean infiltrators were killed and five South Korean soldiers wounded at an encounter in ], ].<ref>. Korean DMZ. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.</ref> | |||

| * November 1974: The first of what would be a series of North Korean infiltration tunnels under the DMZ was discovered. | |||

| * March 1975: A second North Korean infiltration tunnel was discovered. | |||

| * June 1976: Three North Korean infiltrators and six South Korean soldiers were killed in the eastern sector south of the DMZ. Another six South Korean soldiers were injured. | |||

| * 18 August 1976: The ] resulted in the death of two U.S. soldiers and injuries to another four U.S. soldiers and five South Korean soldiers in a neutral zone of the ]. | |||

| * October 1978: The ] was discovered. | |||

| * October 1979: Three North Korean agents attempting to infiltrate the eastern sector of the DMZ were intercepted, killing one of the agents. | |||

| * March 1980: Three North Korean infiltrators were killed attempting to enter the south across the estuary of the ]. | |||

| * March 1981: Three North Korean infiltrators spotted at ], ], one was killed. | |||

| * July 1981: Three North Korean infiltrators were killed in the upper stream of ]. | |||

| * May 1982: Two North Korean infiltrators were spotted on the east coast, one was killed. | |||

| * March 1990: The fourth North Korean infiltration tunnel was discovered, in what may be a total of 17 tunnels in all. | |||

| * May 1992: Three North Korean infiltrators dressed in South Korean uniforms were killed at ], ]. Three South Koreans were also wounded. | |||

| * October 1995: Two North Korean infiltrators were intercepted at ]. One was killed, the other escaped. | |||

| * April 1996: Several hundred North Korean armed troops entered the ] and elsewhere on three occasions in violation of the Korean armistice agreement. | |||

| * May 1996: Seven North Korean soldiers crossed the DMZ but withdrew when fired upon by South Korean troops. | |||

| * April 1997: Five North Korean soldiers cross the military demarcation line's ] sector and fired at South Korean positions. | |||

| * July 1997: Fourteen North Korean soldiers crossed the military demarcation line, causing a 23-minute exchange of heavy gunfire. | |||

| * May 2006: Two North Korean soldiers enter the DMZ and cross into South Korea. They return after South fires warning shots. | |||

| * October 2006: South Korea fires warning shots after North Korean soldiers cross briefly into their side of the border. | |||

| * 23 November 2010: After a Northern warning to cease planned military drills near the island of ], the South commenced the drill. The North then ] with heavy artillery in response to the firings related to the South's readiness-exercise and the South returned fire with howitzers. On Yeonpyeong, 4 were killed (including 2 civilians) and 15 injured.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-11818005 | work=BBC News | title=North Korean artillery hits South Korean island | date=23 November 2010}}</ref> | |||

| * 10 October 2014: South Korean forces fire 40 machine gun rounds at North Korean forces who had fired for 20 minutes at propaganda balloons flying across the DMZ from South Korea.<ref>http://www.cnn.com/2014/10/10/world/asia/koreas-fire-exchange/</ref> | |||

| * 19 October 2014: North and South Korean forces exchange small arms fire for 10 minutes after South Koreans fire warning shots at a North Korean patrol approaching the DMZ.<ref>http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-29681682</ref> | |||

| On 1 November 2018, ]s were established across the DMZ to help ensure the end of hostility on land, sea and air.<ref name=nov1>{{cite web|url=https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20181101002500315|title=Koreas halt all 'hostile' military acts near border|last=이 |first=치동|date=1 November 2018|website=]|access-date=28 February 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190220031255/https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20181101002500315|archive-date=20 February 2019|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=nov1again /> The buffer zones stretch from the north of Deokjeok Island to the south of Cho Island in the West Sea and the north of Sokcho city and south of Tongchon County in the East (Yellow) Sea.<ref name=nov1again>{{cite web|url=https://www.nknews.org/2018/10/two-koreas-end-military-drills-begin-operation-of-no-fly-zone-near-mdl-mnd/|title=Two Koreas end military drills, begin operation of no-fly zone near MDL: MND - NK News - North Korea News|date=31 October 2018|access-date=28 February 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190301214418/https://www.nknews.org/2018/10/two-koreas-end-military-drills-begin-operation-of-no-fly-zone-near-mdl-mnd/|archive-date=1 March 2019|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=nov1 /> In addition, ]s were established.<ref name=nov1 /><ref name=nov1again /> | |||

| ===Incidents in other areas=== | |||