| Revision as of 00:46, 25 July 2006 edit151.44.81.169 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:26, 5 January 2025 edit undo2a00:23c7:881e:f300:bd6b:872e:80e2:8833 (talk) →The historical JesusTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Extra-canonical sayings gospel}} | |||

| {{Gnosticism}} | |||

| {{Distinguish|Acts of Thomas|Book of Thomas the Contender|Infancy Gospel of Thomas}} | |||

| The '''''Gospel of Thomas''''' is the modern name given to a ]-era ] completely preserved in a ] ] ] discovered in ] at ], ]. Unlike the four canonical ]s, which combine narrative accounts of the life of ] with sayings, ''Thomas'' is a "sayings gospel". It takes the less structured form of a collection of sayings attributed to Jesus, brief dialogues with Jesus, and sayings that some of his disciples reported to ]. Thomas does not have a narrative framework, nor is it worked into any overt ] or ]al context. | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2020}} | |||

| {{Infobox religious text | |||

| | image = File:El Evangelio de Tomás-Gospel of Thomas- Codex II Manuscritos de Nag Hammadi-The Nag Hammadi manuscripts.png | |||

| | caption = ]:{{pb}}The beginning of the Gospel of Thomas | |||

| | author = Attributed to ] | |||

| | religion = ] | |||

| | language = ], ] | |||

| | verses = | |||

| | period = ]{{pb}}(possibly ]) | |||

| }} | |||

| {{New Testament Apocrypha}} | |||

| The '''Gospel of Thomas''' (also known as the '''Coptic Gospel of Thomas''') is a non-canonical{{sfnp|Foster|2008|p=16}} ]. It was discovered near ], ], in 1945 among a group of books known as the ]. Scholars speculate the works were buried in response to a letter from Bishop ] declaring a strict canon of Christian scripture. Most scholars place the composition during the second century, {{sfnp|Bock|2006|p=61,63}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Ehrman |first=Bart |author-link=Bart Ehrman |title=Lost Christianities |url= https://archive.org/details/lostchristianiti00ehrm |url-access=registration |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=New York |date=2003 |pages=xi–xii |isbn=978-0-19-514183-2}}</ref> while others have proposed dates as late as 250 AD with signs of origins perhaps dating back to 60 AD.{{sfnp|Valantasis|1997|p=12}}{{sfnp|Porter|2010|p=9}} Many scholars have seen it as evidence of the existence of a "]" that might have been similar in its form as a collection of sayings of ], without any accounts of his deeds or his life and death, referred to as a sayings gospel, though most conclude that Thomas depends on or harmonizes the Synoptics.{{sfnp|Meier|1991|pp=135–138}}{{sfnp|Schnelle|2007|p=230}}<ref>{{cite book |last=McLean |first=Bradley H.|date=1994 |editor-last=Piper| editor-first=Ronald A. |title=The Gospel behind the Gospels: Current Studies on Q |publisher=Brill |pages=321–345 |chapter=Chapter 13: On the Gospel of Thomas and Q |isbn=978-90-04-09737-7}}</ref> | |||

| The work comprises ] sayings attributed to ]. Some of these sayings resemble those found in the four ]s (], ], ], and ]). Others were unknown until its discovery, and a few of these run counter to sayings found in the four canonical gospels. | |||

| The ] text, the second of seven contained in what scholars have designated as Nag Hammadi Codex II, is composed of 114 sayings attributed to Jesus. Almost two-thirds of these sayings resemble those found in the ]{{sfnp|Linssen|2020}} and its '']'' counts more than 80% of parallels,{{sfnp|Guillaumont|Puech|Quispel|Till|1959|pp=59-62}} while it is speculated that the other sayings were added from ] tradition.{{sfnp|Ehrman|2003b|pp=19–20}} Its place of origin may have been ], where ] traditions were strong.{{sfnp|Dunn|Rogerson|2003|p=1574}} Other scholars have suggested an ]n origin.{{sfnp|Brown|2019}} | |||

| When a Coptic version of the complete text of ''Thomas'' was found, scholars realized that three separate ] portions of it had already been discovered in ], Egypt, in ]. The manuscripts bearing the Greek fragments of the ''Gospel of Thomas'' have been dated to about ], and the manuscript of the Coptic version to about ]. Although the Coptic version is not quite identical to any of the Greek fragments, it is believed that the Coptic version was translated from an earlier Greek version. | |||

| The introduction states: "These are the hidden words that the living Jesus spoke and Didymos Judas Thomas wrote them down."{{sfnp|Patterson|Robinson|Bethge|1998}} Didymus (]) and Thomas (]) both mean "twin". Most scholars do not consider the ] the author of this document; the author remains unknown.{{sfnp|DeConick|2006|p=2}} Because of its discovery with the Nag Hammadi library, and the cryptic nature, it was widely thought the document originated within a ] of early Christians, ].{{sfnp|Layton|1987|p=361}}{{sfnp|Ehrman|2003a|p=59}} By contrast, critics have questioned whether the description of Thomas as an entirely gnostic gospel is based solely on the fact it was found along with gnostic texts at Nag Hammadi.{{sfnp|Davies|1983a|pp=23–24}}{{sfnp|Ehrman|2003a|p=59}} | |||

| ==Confusion with other works== | |||

| The ''Gospel of Thomas'' is distinct and unrelated to other ]l or ] works, such as the '']'' or the work called the '']'', which expands on the canonical texts to describe the miraculous childhood of Jesus. When ] and ] (ca. ]) refer to a "Gospel of Thomas" among the ] apocryphal gospels, it is unclear whether they mean the ''Infancy Gospel of Thomas'' or this "sayings" Gospel of Thomas. The ''Gospel of Thomas'' is also distinct from the '']'', a clearly ] text. | |||

| The Gospel of Thomas is very different in tone and structure from other ] and the four canonical Gospels. Unlike the canonical Gospels, it is not a ] account of Jesus' life; instead, it consists of ''logia'' (sayings) attributed to Jesus, sometimes stand-alone, sometimes embedded in short ] or ]; 13 of its 16 parables are also found in the ]. The text contains a possible allusion to the death of Jesus in logion 65{{sfnp|DeConick|2006|p=214}} (]), but does not mention his ], his ], or the ]; nor does it mention a messianic understanding of Jesus.{{sfnp|McGrath|2006|p=12}}{{sfnp|Dunn|Rogerson|2003|p=1573}} | |||

| In the ], ] mentioned a "Gospel of Thomas" in his ''Cathechesis V'': "Let none read the gospel according to Thomas, for it is the work, not of one of the twelve apostles, but of one of ]'s three wicked disciples." Very little trace of ] can be detected in this "sayings" Gospel, the ''Gospel of Thomas'', which is agreed to be simpler and less legend-filled than that philosophy. | |||

| ==Finds and publication== | |||

| ==Corresponding Oxyrhyncus papyri== | |||

| ] | |||

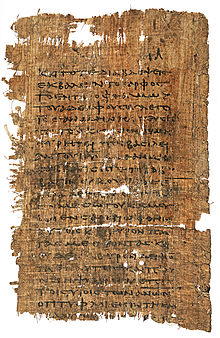

| Prior to the Nag Hammadi library discovery, the sayings of Jesus found in Oxyrhyncus were known simply as ]. The corresponding ] fragments of the ''Gospel of Thomas'' found in ] are: | |||

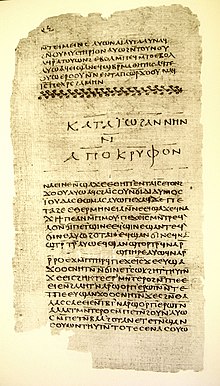

| ], folio 32, the beginning of the Gospel of Thomas]] | |||

| The manuscript of the Coptic text (]), found in 1945 at Nag Hammadi in Egypt, is dated at around 340 AD. It was first published in a photographic edition in 1956.<ref group=note>For photocopies of the manuscript see: {{cite web |url=http://www.gospels.net/thomas/ |title=The Gospel of Thomas Resource Center « gospels.net |access-date=2010-02-04 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101008055033/http://www.gospels.net/thomas/ |archive-date=8 October 2010}}</ref> This was followed three years later (1959) by the first English-language translation, with Coptic transcription.{{sfnp|Guillaumont|Puech|Quispel|Till|1959}} In 1977, ] edited the first complete collection of English translations of the Nag Hammadi texts.{{sfnp|Robinson|1988}} The Gospel of Thomas has been translated and annotated worldwide in many languages. | |||

| The original Coptic manuscript is now the property of the ] in Cairo, Egypt, Department of Manuscripts.{{sfnp|Labib|1956}} | |||

| *]: this is half a leaf of papyrus which contains fragments of logion 26 through 33. | |||

| *]: this contains fragments of the beginning through logion 7, logion 24 and logion 36 on the flip side of a papyrus containing ] data. | |||

| *]: this contains fragments of logion 36 through logion 39 and is actually 8 fragments named ''a'' through ''h'', whereof ''f'' and ''h'' have since been lost. | |||

| ===Oxyrhynchus papyrus fragments=== | |||

| ==Date of Composition== | |||

| After the Coptic version of the complete text was discovered in 1945 at Nag Hammadi, scholars soon realized that three different Greek text fragments previously found at ] (the ]), also in Egypt, were part of the Gospel of Thomas.{{sfnp|Grenfell|Hunt|1897}}{{sfnp|Grant|Freedman|1960}} These three papyrus fragments of Thomas date to between 130 and 250 AD. | |||

| There is currently much debate about when the text was composed, with scholars generally falling into two main camps: an '''early camp''' favoring a date in the ] before the canonical gospels, and a '''late camp''' favoring a time after the last of the canonical gospels in the ]. Among critical scholars, the early camp is dominant in North America, while the late camp is more popular in Europe (especially in the UK and Germany). | |||

| Prior to the Nag Hammadi library discovery, the sayings of Jesus found in Oxyrhynchus were known simply as ]. The corresponding ] Greek fragments of the Gospel of Thomas, found in Oxyrhynchus are: | |||

| ===The early camp=== | |||

| * ]: fragments of logia 26 through 33, with the last two sentences of logion 77 in the Coptic version included at the end of logion 30 herein. | |||

| The early camp argues that since it consists of mostly original material and does not seem to be based on the canonical gospels, it must have been transcribed from an oral tradition. Since the practice of considering oral tradition as authoritative ended during the ], the ''Gospel of Thomas'' therefore must have been written before then, perhaps as early as around ]. Since this date precedes the dates of the traditional four gospels, there is some claim that the ''Gospel of Thomas'' is or has some connection to the hypothetical ]—a text (or oral verse) that, with Mark, is postulated to have been a source for the gospels of Matthew and Luke. | |||

| * ]: fragments of the beginning through logion 7, logion 24 and logion 36 on the flip side of a papyrus containing ] data.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://163.1.169.40/cgi-bin/library?e=d-000-00---0POxy--00-0-0--0prompt-10---4----ded--0-1l--1-en-50---20-about-1708--00031-001-1-0utfZz-8-00&a=d&c=POxy&cl=CL5.1.4&d=HASH66d3d01e4d152cbe92ae08|title=P.Oxy.IV 0654|access-date=2 November 2011|archive-date=3 March 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303203556/http://163.1.169.40/cgi-bin/library?e=d-000-00---0POxy--00-0-0--0prompt-10---4----ded--0-1l--1-en-50---20-about-1708--00031-001-1-0utfZz-8-00&a=d&c=POxy&cl=CL5.1.4&d=HASH66d3d01e4d152cbe92ae08|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| * ]: fragments of logia 36 through 39. 8 fragments designated ''a'' through ''h'', whereof ''f'' and ''h'' have since been lost.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://163.1.169.40/cgi-bin/library?e=d-000-00---0POxy--00-0-0--0prompt-10---4----ded--0-1l--1-en-50---20-about-1708--00031-001-1-0utfZz-8-00&a=d&c=POxy&cl=CL5.1.4&d=HASH66d3d01e4d152cc692ae08|title=P.Oxy.IV 0655|access-date=2 November 2011|archive-date=3 March 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303202730/http://163.1.169.40/cgi-bin/library?e=d-000-00---0POxy--00-0-0--0prompt-10---4----ded--0-1l--1-en-50---20-about-1708--00031-001-1-0utfZz-8-00&a=d&c=POxy&cl=CL5.1.4&d=HASH66d3d01e4d152cc692ae08|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| The wording of the Coptic sometimes differs markedly from the earlier Greek Oxyrhynchus texts, the extreme case being that the last portion of logion 30 in the Greek is found at the end of logion 77 in the Coptic. This fact, along with the quite different wording Hippolytus uses when apparently quoting it (see below), suggests that the Gospel of Thomas "may have circulated in more than one form and passed through several stages of redaction."{{sfnp|Meier|1991|p=125}} | |||

| The early camp argues that about half of the material in ''Thomas'' has no known parallels to the New Testament, and at least some of this material could plausibly be attributed to the ], such as saying 42 "Be passers-by". | |||

| Although it is generally thought that the Gospel of Thomas was first composed in Greek, there is evidence that the Coptic Nag Hammadi text is a translation from ] (see ]). | |||

| The early camp also notes that Q is almost universally regarded by secular biblical scholars as the most ] for the ] and is widely regarded to be the earliest written text of Jesus' teachings. It has been hypothesized that Q exists in 3 strata, termed Q1, Q2, and Q3, with the apocalyptic material belonging in Q2 and Q3. Secular biblical scholars have identified 37 sayings that overlap between ''Thomas'' and Q, all of which are conjectured to be in either Q1 or Q2 and none of which included the latter, apocalyptic material of Q3. As ''Thomas'' does not incorporate material from Q3, it was not aware of Q3 and precedes it. The Q layers of Q1 and Q2 are thought to predate the four gospels. Hence the ''Gospel of Thomas'' is thought to be early. | |||

| ===Attestation=== | |||

| The central argument of ]'s '']'' (2003) is that there seems to be conflict between the Gospel of John and the ''Gospel of Thomas''. According to Pagels, specific passages in the Gospel of John can only be understood in light of a community based on a philosophy espoused by the ''Gospel of Thomas'', though not necessarily precisely represented by that document. Pagels interprets the "]" episode of the Gospel of John as rebuttal for the "''Thomas'' community"—Thomas physically touches Jesus and acknowledges his fleshy nature, in contrast to the ] of gnostic groups. Her interpretation of John requires that ''Thomas''-like ideas or a ''Thomas''-like community existed when John's gospel was written. | |||

| The earliest surviving written references to the Gospel of Thomas are found in the writings of ] ({{c.|222–235}}) and ] ({{c.|233|lk=no}}).{{sfnp|Koester|1990|pp=77ff}} Hippolytus wrote in his '']'' 5.7.20: | |||

| {{blockquote|<nowiki>]<nowiki>]</nowiki> speak{{nbsp}} of a nature which is both hidden and revealed at the same time and which they call the thought-for kingdom of heaven which is in a human being. They transmit a tradition concerning this in the Gospel entitled "According to Thomas," which states expressly, "The one who seeks me will find me in children of seven years and older, for there, hidden in the fourteenth ], I am revealed."}} | |||

| This appears to be a reference to saying 4 of Thomas, although the wording differs significantly. As translated by Thomas O. Lambdin, saying 4 reads: "Jesus said, 'the man old in days will not hesitate to ask a small child seven days old about the place of life, and he will live. For many who are first will become last, and they will become one and the same".{{sfnp|Robinson|1988|p=126}} In this context, the preceding reference to the "sought-after reign of the heavens within a person" appears to be a reference to sayings 2 and 3.{{sfnp|Johnson|2010}} Hippolytus also appears to quote saying 11 in ''Refutation'' 5.8.32, but without attribution.{{sfnp|Johnson|2010}} | |||

| Another argument for the early camp is that there is overlap between Paul's epistles and ''Thomas''. The authentic corpus of Paul's epistles, which includes ], ], and ], is regarded by almost all biblical scholars as predating the canonical gospels of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John. Some secular scholars see common themes in Paul and in ''Thomas'' absent from the canonical gospels (nor independently attested by them), and conclude that ''Thomas'' draws upon a common sayings pool also used by the canonical gospels and Paul. According to this theory, Paul drew on sayings widely recognized to have come from Jesus, some which are uniquely preserved in the ''Gospel of Thomas''. | |||

| ] listed the "Gospel according to Thomas" as being among the ] apocryphal gospels known to him (''Hom. in Luc.'' 1). He condemned a book called "Gospel of Thomas" as heretical; it is not clear that it is the same gospel of Thomas, however, as he possibly meant the ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Carlson |first=Stephen C. |date=2014-01-01 |title=Origen's Use of the Gospel of Thomas |url=https://www.academia.edu/7414722 |journal=Sacra Scriptura: How "Non-Canonical" Text Functioned in Early Judaism and Early Christianity}}</ref> | |||

| The early camp argues that if the author of ''Thomas'' knew of the New Testament, including the Pauline epistles, and if it is thought that "Thomas" showed gnostic tendencies, then it is surprising that he did not take the opportunity to include many verses that would have supported such "gnostic" theology, which are present in the canonical New Testament, such as John 8:58, "Before Abraham was born, I AM." The ''Gospel of Thomas'' includes a great deal of material unparalleled in the New Testament, but lacks distinctive terms from second-century ] such as ]s, ], ]s, or ] that would be expected from a product of historical Gnosticism: this is seen by some as another justification for an earlier date of authorship. | |||

| In the 4th and 5th centuries, various Church Fathers wrote that the Gospel of Thomas was highly valued by ]. In the 4th century, ] mentioned a "Gospel of Thomas" twice in his '']'': "The Manichaeans also wrote a Gospel according to Thomas, which being tinctured with the fragrance of the evangelic title corrupts the souls of the simple sort."<ref>Cyril ''Catechesis'' </ref> and "Let none read the Gospel according to Thomas: for it is the work not of one of the twelve Apostles, but of one of the three wicked disciples of Manes."<ref>Cyril ''Catechesis'' </ref> The 5th-century '']'' includes "A Gospel attributed to Thomas which the Manichaean use" in its list of heretical books.{{sfnp|Koester|1990|p=78}} | |||

| The early camp counters arguments from the history of religion (and the relatively late appearance of gnostic thought) that ''Thomas'' reflects very little to none of the full-blown ] gnosticism as seen in many of the other texts in the cache of manuscripts found at Nag Hammadi. In fact, some point out not all of the Nag Hammadi texts are gnostic; for example, one of the texts is an excerpt of a paraphrase of ]'s ''Republic,'' which predates gnosticism by centuries. However, it is speculated that gnosticism was heavily influenced by the creation myth that Plato put forth in ''Timaeus'', and that the fragment enclosed in Codex VI has Socrates make a rather far-fetched analogy of just and unjust behavior based on a gruesome image of the Chimaera, the same sort of argument and image that full-blown Gnostics revelled in. | |||

| ==Date of composition== | |||

| It is also noted that gnosticism was a fluid belief system containing both new elements and old, and that material identifed as "gnostic" in ''Thomas'' may have been current as early as ]. As for the focus on the cross that Thomas lacks, early daters contend that Thomas belonged to an early form of Christianity, exemplified by Q, that concentrated on the sayings and teachings of Jesus. If one is skeptical of Q, however, as several leading scholars in the UK are (see ]), this argument is less probative. | |||

| Richard Valantasis writes: | |||

| {{blockquote|Assigning a date to the Gospel of Thomas is very complex because it is difficult to know precisely to what a date is being assigned. Scholars have proposed a date as early as 60{{nbsp}}AD or as late as 140{{nbsp}}AD, depending upon whether the Gospel of Thomas is identified with the original core of sayings, or with the author's published text, or with the Greek or Coptic texts, or with parallels in other literature.{{sfnp|Valantasis|1997|p=12}} }} | |||

| Earl Doherty argued that when the ''Gospel of Thomas'' does parallel Q or the New Testament, it shows less development, more "primitive" form than the latter. | |||

| Valantasis and other scholars argue that it is difficult to date Thomas because, as a collection of ''logia'' without a narrative framework, individual sayings could have been added to it gradually over time.{{sfnp|Patterson|Robinson|Bethge|1998|p=40}} Valantasis dates Thomas to 100–110 AD, with some of the material certainly coming from the first stratum, which is dated to 30–60 AD.{{sfnp|Valantasis|1997|p=20}} J. R. Porter dates the Gospel of Thomas to 250 AD.{{sfnp|Porter|2010|p=9}} | |||

| ===The late camp=== | |||

| The late camp, on the other hand, dates ''Thomas'' sometime after ], generally in the early and mid-], but a few argue that ''Thomas'' is dependent on the '']'', which was composed shortly after ]. Since the Greek fragments of ''Thomas'' found in Egypt are typically dated between ] and ], the ultra-late, post-Diatessaronic position remains a small minority, even within the late camp. | |||

| Scholars generally fall into one of two main camps: an "early camp" favoring a date for the core "before the end of the first century,"<ref>{{Cite web |title=Mark's Use of the Gospel of Thomas |url=http://users.misericordia.edu/davies/thomas/tomark1.htm}}</ref> prior to or approximately contemporary with the composition of the canonical gospels; and a more common "late camp" favoring a date in the 2nd century, after composition of the canonical gospels.<ref name="Bock2" group=quote/><ref group=quote>{{harvnb|Van Voorst|2000|p=189}}: "Most interpreters place its writing in the second century, understanding that many of its oral traditions are much older."</ref> | |||

| The main argument put forth by the late camp is an argument from ''redaction''. Under the most commonly accepted solution to the ], Matthew and Luke both used Mark as well as a lost sayings collection called ] to compose their gospels. Sometimes Matthew and Luke modified the wording of their source, Mark (or Q), and the modified text is known as ''redaction''. Proponents of the late camp argue that some of this secondary redaction created by Matthew and Luke shows up in ''Thomas'', which means that ''Thomas'' was written after Matthew and Luke were composed. Since Matthew and Luke are generally thought to have been composed in the ] and ], ''Thomas'' would have to be composed later than that. Members of the early camp respond to this argument by suggesting that 2nd-century scribes may have been the ones responsible for the Synoptic redaction now present in our manuscripts of ''Thomas'', not its original author. Both camps agree, however, that the fluidity of the text in the ] makes dating the ''Thomas'' very difficult. | |||

| In August 2023, the ] published the second century ], which includes the earliest extant fragment from the Gospel of Thomas.<ref name=Moss>{{cite web |url=https://www.thedailybeast.com/scholars-publish-new-papyrus-with-early-sayings-of-jesus?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAAR3utn-NmoTKE4Fjhcet2v0Iba6YZLtNmXz4s02YCOhVsuDm63idJAfmdIk_aem_AWDFErL3O7DdguHs4kvCyrPahWzwJENj6Ed_lfsQrYgXVA5jIFdCVc9BYjoSC6mhGtc6NBYKf4PIq3sVrtTHn1Eh |title=Scholars Publish New Papyrus With Early Sayings of Jesus | |||

| A related argument is that Matthew and Luke independently incorporated their own local traditions into their gospels in addition to the traditions they obtained from Mark and Q. These local traditions are usually known as ''Sondergut'', or ''special material''. The late camp notes that ''Thomas'' parallels not just the shared material in the Synoptic gospels, but also the special material found in each one of them. The late camp concludes that accessing this diverse set of materials, including local traditions, would be much easier after the canonical gospels were circulating rather than before. Those who argue for a later date for ''Thomas'' also call into question the assumption of those within the early camp that "sayings" material is necessarily earlier than full-fledged gospels that include narrative. | |||

| |last=Moss |first=Candida |date=Aug 31, 2023 |website = thedailybeast.com| publisher = The Daily Beast Company LLC| access-date = May 25, 2024|quote=}}</ref><ref name=Holmes>{{cite web |url=https://textandcanon.org/whats-the-big-deal-about-a-new-papyrus-with-sayings-of-jesus/ |title=What's the Big Deal about a New Papyrus with Sayings of Jesus? |last=Holmes |first=Michael |date= September 13, 2023|website=textandcanon.org |publisher=Text & Canon Institute |access-date = May 25, 2024 |quote=}}</ref> | |||

| ===Early camp=== | |||

| Bart Ehrman, (in ''Jesus Apocalyptic Prophet of the Millennium'') argues that the Jesus of history was a failed ] preacher, and that his fervent apocalyptic beliefs are recorded in the earliest Christian documents, Mark and the authentic Pauline epistles. The earliest Christians believed Jesus would soon return, and their beliefs are echoed in the earliest Christian writings. As the ] did not materialize, later gospels, such as Luke and John, and pseudo-Pauline epistles, such as Timothy, deemphasized an immanent end of the world, with the epistle of Peter even rationalizing the delay: "A day is as thousand years . . . in the last days scoffers will come, scoffing and following their own evil desires . . . where is this 'coming' your Christ has promised, ever since our forefathers died" (2 Pet 3:3–5); and Luke: "No one will say the Kingdom is here or there for behold it lies within you" (17:21). As Elaine Pagels pointed out, many sayings in the ''Gospel of Thomas'' relate to the coming end as a profoundly mistaken view, and that the real Kingdom is within the human heart, as stated in Luke above, and such a viewpoint implies a late date as the end of the world and Second Coming never materialized, and the early Christians had to explain Christ's non-appearance. | |||

| ====Form of the gospel==== | |||

| The ''Gospel of Thomas'' makes no mention of Hell, Satan, Eternal Damnation, and demons, which is in contrast to the earliest extant Christian documents, the Pauline epistles and Mark, which clearly show a belief in these areas. Thus the ''Gospel of Thomas'' was produced by a community or author who did not believe in Hell, Satan, Eternal Damnation, and demons. So the author/community associated with the ''Gospel of Thomas'' appears to be unconnected with the early Christian community of followers of Paul and Mark. | |||

| Theissen and Merz argue the genre of a collection of sayings was one of the earliest forms in which material about Jesus was handed down.{{sfnp|Theissen|Merz|1998|pp=38–39}} They assert that other collections of sayings, such as the Q source and the collection underlying ], were absorbed into larger narratives and no longer survive as independent documents, and that no later collections in this form survive.{{sfnp|Theissen|Merz|1998|pp=38–39}} ] also asserted that the genre of a "sayings collection" is indicative of the 1st century,{{sfnp|Meyer|2001|p=73}} and that in particular the "use of parables without allegorical amplification" seems to antedate the canonical gospels.{{sfnp|Meyer|2001|p=73}} | |||

| The last major argument for ''Thomas'' being later than the ] argues that Gnosticism is a later development, while the earliest Christianity, as evident in Paul's letters, was more Jewish than Gentile and focused on the death and resurrection of Jesus more than his words. In this connection, it is observed that the Jesus of ''Thomas'' does not seem very Jewish, and that its current form reflects the work of 2nd-century Gnostic thought, such as the rejection of the physical world and women (see ''Thomas'' 114). <!-- moving this to Talk —AllanBz --> Graham Stanton (''The Gospels and Jesus'', p. 129) finds in ''Thomas'' a Gnostic document: "removal of the Gnostic veneer will never be easy." It should be noted that secular biblical scholars and Christian fundamentalists offer very different dates for key New Testament documents. | |||

| ====Independence from synoptic gospels==== | |||

| ==The ''Gospel of Thomas'' and the canon of the New Testament== | |||

| ] argues that the apparent independence of the ordering of sayings in Thomas from that of their parallels in the synoptics shows that Thomas was not evidently reliant upon the canonical gospels and probably predated them.{{sfnp|Davies|1992}}{{sfnp|Davies|n.d.}} Some authors argue that Thomas was a source for Mark, usually considered the earliest of the synoptic gospels.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Johnson |first=Kevin |date=1997-01-01 |title=Mark's Use of the Gospel of Thomas Part Two |url=https://www.academia.edu/41451442 |journal=Neotestamentica}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite journal |last=Davies |first=Stevan |date=December 1, 1996 |title=The use of the Gospel of Thomas in the Gospel of Mark |url=https://journals.co.za/doi/epdf/10.10520/AJA2548356_472 |journal=Neotestamentica |volume=30 |issue=2 |pages=307–334 |via=journals.co.za}}</ref> Several authors argue that when the logia in Thomas do have parallels in the synoptics, the version in Thomas often seems closer to the source. Theissen and Merz give sayings 31 (]) and 65 (]) as examples of this.{{sfnp|Theissen|Merz|1998|pp=38–39}} Koester agrees, citing especially the parables contained in sayings 8, 9, 57, 63, 64 and 65.{{sfnp|Koester|Lambdin|1996|p=125}} In the few instances where the version in Thomas seems to be dependent on the synoptics, Koester suggests, this may be due to the influence of the person who translated the text from Greek into Coptic.{{sfnp|Koester|Lambdin|1996|p=125}} | |||

| The fact that the ''Gospel of Thomas'' does not seem to have been considered for the ] is seen by some as an indication of its being of a later date—had it actually been written by the apostle Thomas, they argue, it would have been at least seriously considered by those in the century immediately following Jesus' death. This opinion is more popular among ]s who accept a divinely inspired New Testament ] as an article of their faith—especially those considering themselves ] or ] Christians. | |||

| Koester also argues that the absence of narrative materials, such as those found in the canonical gospels, in Thomas makes it unlikely that the gospel is "an eclectic excerpt from the gospels of the New Testament".{{sfnp|Koester|Lambdin|1996|p=125}} He also cites the absence of the eschatological sayings considered characteristic of Q source to show the independence of Thomas from that source.{{sfnp|Koester|Lambdin|1996|p=125}} | |||

| The harsh and widespread reaction to ]'s canon, the first New Testament canon known to ever have been created, may demonstrate that, by 140, it had become widely accepted that other texts formed parts of the records of the life and ministry of Jesus. Although arguments about some potential New Testament books, such as the '']'' and ], continued well into the 4th century, four canonical gospels, attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, were universally accepted among orthodox Christians at least as early as the mid-2nd century. Tatian's widely used '']'', compiled between 160 and 175, utilized the four gospels without any consideration of others. Irenaeus of Lyons wrote in the late 2nd century that ''since there are four quarters of the earth ... it is fitting that the church should have four pillars ... the four Gospels'' (''Against Heresies'', 3.11.8), and then shortly thereafter made the first known quotation from a fourth gospel—the canonical version of the Gospel of John. The late 2nd-century ] also recognizes only the three synoptic gospels and John. Bible scholar ] wrote regarding the formation of the New Testament canon, "Although the fringes of the emerging canon remained unsettled for generations, a high degree of unanimity concerning the greater part of the New Testament was attained among the very diverse and scattered congregations of believers not only throughout the Mediterranean world, but also over an area extending from Britain to Mesopotamia." | |||

| ====Intertextuality with the Gospel of John==== | |||

| It should be noted that information about the historical Jesus itself was not a singular criterion for inclusion into the New Testament Canon. The canonizers chose to include many books that contain neither much information about the historical Jesus nor teachings from the historical Jesus, such as the Epistles and the book of Revelation. | |||

| {{Update|section|reason=The majority of this section's sources come from the early-to-mid 2000s. As one example, the final paragraph said that as "the scholarly debate continues" someone "recently" responded to these in 2009. This was clearly out of date. That error is fixed, but the rest of the section remains outdated and in need of work.|date=September 2016}} | |||

| Another argument for an early date is what some scholars have suggested is an interplay between the ] and the ''logia'' of Thomas. Parallels between the two have been taken to suggest that Thomas' ''logia'' preceded John's work, and that the latter was making a point-by-point riposte to Thomas, either in real or mock conflict. This seeming dialectic has been pointed out by several New Testament scholars, notably Gregory J. Riley,{{sfnp|Riley|1995}} ],{{sfnp|DeConick|2001}} and ].{{sfnp|Pagels|2004}} Though differing in approach, they argue that several verses in the Gospel of John are best understood as responses to a Thomasine community and its beliefs. Pagels, for example, says that the Gospel of John states that Jesus contains the divine light, while several of Thomas' sayings refer to the light born 'within'.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Bettencourt |first=Michael |date=October 30, 2018 |title=The Gospel of Thomas According to Dr. Elaine Pagels {{!}} Revel News |url=https://blogs.yu.edu/revel/2018/10/30/the-gospel-of-thomas-according-to-dr-elaine-pagels/ |access-date=2022-07-13 |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>Logia 24, 50, 61, 83</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Townsend |first=Mark |title=Jesus Through Pagan Eyes: Bridging Neopagan Perspectives with a Progressive Vision of Christ |publisher=Flux |year=2012 |isbn=978-0738721910 |location=Minnesota, U.S. |pages=54 |language=English}}</ref> | |||

| The Gospel of John is the only canonical one that gives Thomas the Apostle a dramatic role and spoken part, and Thomas is the only character therein described as being {{transliteration|grc|apistos}} ({{gloss|unbelieving}}), despite the failings of virtually all the Johannine characters to live up to the author's standards of belief. With respect to the famous story of "]",<ref>Jn. 20:26–29</ref> it is suggested{{sfnp|Pagels|2004}} that the author of John may have been denigrating or ridiculing a rival school of thought. In another apparent contrast, John's text matter-of-factly presents a bodily resurrection as if this is a '']'' of the faith; in contrast, Thomas' insights about the spirit-and-body are more nuanced.<ref>Logia 29, 80, 87</ref> For Thomas, resurrection seems more a cognitive event of spiritual attainment, one even involving a certain discipline or asceticism. Again, an apparently denigrating portrayal in the "Doubting Thomas" story may either be taken literally, or as a kind of mock "comeback" to Thomas' logia: not as an outright censuring of Thomas, but an improving gloss, as Thomas' thoughts about the spirit and body are not dissimilar from those presented elsewhere in John.<ref group=note>e.g. Jn. 3:6, 6:52–6 – but pointedly contrasting these with 6:63.</ref> John portrays Thomas as physically touching the risen Jesus, inserting fingers and hands into his body, and ending with a shout. Pagels interprets this as signifying one-upmanship by John, who is forcing Thomas to acknowledge Jesus' bodily nature. She writes that "he shows Thomas giving up his search for experiential truth{{snd}}his 'unbelief'{{snd}}to confess what John sees as the truth".{{sfnp|Pagels|2004|pp=66–73}} The point of these examples, as used by Riley and Pagels, is to support the argument that the text of Thomas must have existed and have gained a following at the time of the writing of the Gospel of John, and that the importance of the Thomasine logia was great enough that the author of John felt the necessity of weaving them into their own narrative. | |||

| The ''Gospel of Thomas'' may have failed to be included in the canon of the New Testament because: | |||

| *It was deemed ]. | |||

| *It was deemed inauthentic. | |||

| *It was unknown to the canonizers. | |||

| *It was thought to be superseded by the narrative gospels. | |||

| *It belonged to a branch of Christianity outside the circle of ]. | |||

| *It was never seriously considered for the canon. | |||

| As this scholarly debate continued, theologian Christopher W. Skinner<!-- Please do not wikilink to Christopher Skinner the mathematician --> disagreed with Riley, DeConick, and Pagels over any possible John–Thomas interplay, and concluded that in the book of John, Thomas the disciple "is merely one stitch in a wider literary pattern where uncomprehending characters serve as ] for Jesus's words and deeds."{{sfnp|Skinner|2009|pp=38, 227}} | |||

| ==The philosophy of the ''Gospel of Thomas''== | |||

| The gospel begins, "These are the sayings that the living Jesus spoke and Didymos Judas Thomas recorded." It should be noted that the word "Didymos" (Greek) and "Thomas" (Hebrew) both mean "Twin" and are not actually names. This is in fact done so that the reader of the original Greek text does not mistake the Hebrew word "Thomas" for a surname. The name of the person this gospel is attributed to is the apostle Judas, who is called Thomas to distinguish himself from Judas Iscariot. It is assumed that he is called the twin of Jesus to denote a state of spiritual sameness. This is affirmed in Thomas v.13, where Jesus says to Thomas, "I am not your teacher. Because you have drank and become drunk from the very same spring from which I draw." | |||

| ====Role of James==== | |||

| This relationship between Thomas and Jesus is what distinguishes this gospel from the four other books in the Catholic canon. In the synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke), Jesus is a wise teacher, prophet or an anointed (''christos'') leader. The Gospel of John, apart from the Thomas gospel and the synoptic gospels, sees Jesus as a divine heir of the godhead and an object of worship. The events in the John gospel are rearranged and told differently than the other gospels perhaps to support and emphasize this view. In the Thomas gospel, Jesus is a spiritual role model, and he is offering everyone the opportunity to become anointed (a Christ) as he is. | |||

| Albert Hogeterp argues that the Gospel's saying 12, which attributes leadership of the community to ] rather than to ], agrees with the description of the early Jerusalem church by Paul in Galatians 2:1–14<ref>{{bibleverse|Galatians|2:1–14}}</ref> and may reflect a tradition predating 70 AD.{{sfnp|Hogeterp|2006|p=137}} Meyer also lists "uncertainty about James the righteous, the brother of Jesus" as characteristic of a 1st-century origin.{{sfnp|Meyer|2001|p=73}} | |||

| In later traditions (most notably in the Acts of Thomas, Book of Thomas the Contender, etc.), Thomas is regarded as the twin brother of Jesus.{{sfnp|Turner|n.d.}} | |||

| The Thomas is ] and emphasizes a direct and unmediated experience of the Divine through becoming a Christ. In Thomas v.108, Jesus said, "Whoever drinks from my mouth will become as I am; I myself shall become that person, and the hidden things will be revealed to him." Furthermore, salvation is personal and found through introspection. In Thomas v.70, Jesus says, "If you bring forth what is within you, what you have will save you. If you do not bring it forth, what you do not have within you will kill you." As such, this form of salvation is idiosyncratic and without literal explanation. In Thomas v.3, Jesus says, | |||

| :''...the Kingdom of God is within you...'' | |||

| ====Depiction of Peter and Matthew==== | |||

| In the other four gospels, Jesus is frequently called upon to explain the meanings of parables or the correct procedure for prayer. But here Jesus constantly tells his disciples to work it out for themselves. In Thomas v.6, his disciples asked him, "Do you want us to fast? How should we pray? Should we give to charity? What diet should we observe?" Jesus replied, "Don't lie, and don't do what you hate, because all things are disclosed before heaven. After all, there is nothing hidden that will not be revealed, and there is nothing covered up that will remain concealed." | |||

| In saying 13, Peter and Matthew are depicted as unable to understand the true significance or identity of Jesus. Patterson argues that this can be interpreted as a criticism against the school of Christianity associated with the Gospel of Matthew, and that "his sort of rivalry seems more at home in the first century than later", when all the apostles had become revered figures.{{sfnp|Patterson|Robinson|Bethge|1998|p=42}} | |||

| ====Parallel with Paul==== | |||

| In contrast to the Gospel of John, where Jesus is likened to a feudal (albeit divine and beloved) Lord, the Thomas gospel sees Jesus as more the ubiquitous vehicle of mystical inspiration and enlightenment. In Thomas v.77 where Jesus said, | |||

| According to Meyer, Thomas's saying 17{{snd}}"I shall give you what no eye has seen, what no ear has heard and no hand has touched, and what has not come into the human heart"{{snd}}is strikingly similar to what ] wrote in 1 Corinthians 2:9,<ref>{{bibleverse|1 Corinthians|2:9}}</ref>{{sfnp|Meyer|2001|p=73}} which was itself an allusion to Isaiah 64:4.<ref>{{bibleverse|Isaiah|64:4}}</ref> | |||

| :''I am the light that shines over all things. I am everywhere. From me all came forth, and to me all return. '' | |||

| :''Split a piece of wood, and I am there. Lift a stone, and you will find me there.'' | |||

| ===Late camp=== | |||

| Like a lord and master in John, Jesus issues edicts in a series of "I am" verses. "I am the Lord ... I am the truth ... the only begotten son ...the way ... the light ... the only salvation ... except but through me ..." But Thomas offers up metaphors "the kingdom of heaven is like ... like a wise fisherman ... like mustard ... like little children ... like the outer and the outer like the inner ..." This is not only a difference in tone but in teaching. The message is clear: John is saying follow orders and Thomas is saying find your way. | |||

| The late camp dates Thomas some time after 100 AD, generally in the early second century.<ref name="Bock2" group=quote>{{harvnb|Bock|2006|pp=61, 63}}: "Most date the gospel to the second century and place its origin in Syria{{nbsp}} Most scholars regard the book as an early second-century work."(61); "However, for most scholars, the bulk of it is later reflecting a second-century work."(63)</ref><ref name="Bock1" group=quote>{{harvnb|Bock|2009|pp=148–149}}: "for most scholars the ''Gospel of Thomas'' is seen as an early-second century text."</ref> They generally believe that although the text was composed around the mid-second century, it contains earlier sayings such as those originally found in the New Testament gospels of which Thomas was in some sense dependent in addition to inauthentic and possibly authentic independent sayings not found in any other extant text. J. R. Porter dates Thomas much later, to the mid-third century.{{sfnp|Porter|2010|p=9}} | |||

| ====Dependence on the New Testament==== | |||

| In most other respects, the Thomas gospel offers terse yet familiar if not identical accounts of the sayings of Jesus as seen in the synoptic gospels. | |||

| Several scholars have argued that the sayings in Thomas reflect conflations and harmonisations dependent on the canonical gospels. For example, saying 10 and 16 appear to contain a redacted harmonisation of Luke 12:49,<ref>{{bibleverse|Luke|12:49}}</ref> 12:51–52<ref>{{bibleverse|Luke|12:51–52}}</ref> and Matthew 10:34–35.<ref>{{bibleverse|Matthew|10:34–35}}</ref> In this case it has been suggested that the dependence is best explained by the author of Thomas making use of an earlier harmonised oral tradition based on Matthew and Luke.{{sfnp|Snodgrass|1989}}{{sfnp|Grant|Freedman|1960|pp=136–137}} Biblical scholar ] also subscribes to this view and notes that "Over half of the New Testament writings are quoted, paralleled, or alluded to in Thomas... I'm not aware of a Christian writing prior to 150 AD that references this much of the New Testament."{{sfnp|Strobel|2007|p=36}} ] also argues that Thomas is dependent on the Synoptics. <ref>{{cite book |last= Goodacre |first= Mark |author-link= Mark Goodacre |year= 2012 |title= Thomas and the Gospels: The Case for Thomas's Familiarity with the Synoptics |publisher= Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. |isbn= 978-0802867483}}</ref> | |||

| Another argument made for the late dating of Thomas is based upon the fact that saying 5 in the original Greek (Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 654) seems to follow the vocabulary used in the Gospel of Luke (Luke 8:17),<ref>{{bibleverse|Luke|8:17}}</ref> and not the vocabulary used in the Gospel of Mark (Mark 4:22).<ref>{{bibleverse|Mark|4:22}}</ref> According to this argument{{snd}}which presupposes firstly the rectitude of the two-source hypothesis (widely held among current New Testament scholars),<ref>{{Cite book |last=Derrenbacker |first=Robert |title=The Enduring Impact of the Gospel of John: Interdisciplinary Studies |publisher=Wipf and Stock Publishers |year=2022 |editor-last1=Derrenbacker |editor-first1=Robert |editor-last2=Lee |editor-first2=Dorothy |editor-last3=Porter |editor-first3=Muriel |location=Eugene |page=3 |chapter=Echoes of Luke in John 20-21}}</ref> in which the author of Luke is seen as having used the pre-existing gospel according to Mark plus a lost Q source to compose their gospel{{snd}}if the author of Thomas did, as saying 5 suggests, refer to a pre-existing Gospel of Luke, rather than Mark's vocabulary, then the Gospel of Thomas must have been composed after both Mark and Luke, the latter of which is dated to between 60 and 90 AD. | |||

| Elaine Pagels, in her book ''Beyond Belief'', argues that the Thomas gospel at first fell victim to the needs of the early Christian community for solidarity in the face of persecution, then to the will of the Emperor Constantine, who at the ] in 325, wanted an end to the sectarian squabbling and a universal Christian creed. She goes on to point out that in spite of it being left out of the Catholic canon, being banned and sentenced to burn, many of the mystical elements have proven to reappear perennially in the works of mystics like ], ] and ] (as long as they did not deny the uniqueness and divinity of Jesus). She concludes that the Thomas gospel gives us a rare glimpse into the diversity of beliefs in the early Christian community, an alternative perspective to the ] and a check on what we take for granted as being heretical as modern Christians. Of course, the church at large sees the Thomas gospel not as a reflection of "Christian diversity" but as an example of one of the early heresies that attacked the church. Writings like the Thomas gospel motivated the church to define its long-held canon and belief in the death and resurrection of Christ in the four gospels which formed the heart of the message proclaimed by the early church in the book of Acts. | |||

| Another saying that employs similar vocabulary to that used in Luke rather than Mark is saying 31 in the original Greek (Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1), where Luke 4:24's term {{transliteration|grc|dektos}} ({{gloss|acceptable}})<ref>{{bibleverse|Luke|4:24}}</ref> is employed rather than Mark 6:4's {{transliteration|grc|atimos}} ({{gloss|without honor}}).<ref>{{bibleverse|Mark|6:4}}</ref> The word {{transliteration|grc|dektos}} (in all its cases and genders) is clearly typical of Luke, since it is only employed by the author in the canonical gospels Luke 4:19,<ref>{{bibleverse|Luke|4:19}}</ref> 4:24, and Acts 10:35.<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|10:35}}</ref> Thus, the argument runs, the Greek Thomas has clearly been at least influenced by Luke's characteristic vocabulary.<ref group=note>For general discussion, see {{harvp|Meier|1991|pp=137, 163–64 n. 133}}. See also {{harvp|Tuckett|1988|pp=132–57, esp. p. 146}}.</ref> | |||

| ==The ''Gospel of Thomas'''s importance and author== | |||

| The ''Gospel of Thomas'' is, in any case, one of the earliest accounts of the teaching of Jesus outside of the canonical gospels and so is considered a valuable text. Some say that this gospel makes no mention of Jesus' resurrection, an important point of faith among ]s. A minority opinion, however, interprets the opening words of the book, "These are the secret sayings which the living Jesus spoke and which Didymos Judas Thomas wrote down" (] translation, 2d. edition, ISBN 0-06-066935-7), to mean that the sayings are being presented as the teaching of Jesus Christ ''after'' the ], due to the use of the term "living". The last verse in the book, which strikes many commentators as appended at a later date, perhaps reflecting a mainstream misogyny not otherwise found in this text, also refers to the "life" in a sense that can only mean the "life everlasting": | |||

| J. R. Porter states that, because around half of the sayings in Thomas have parallels in the synoptic gospels, it is "possible that the sayings in the Gospel of Thomas were selected directly from the canonical gospels and were either reproduced more or less exactly or amended to fit the author's distinctive theological outlook."{{sfnp|Porter|2010|p=166}} According to ], scholars predominantly conclude that Thomas depends on or harmonizes the Synoptics.{{sfnp|Meier|1991|pp=135–138}} | |||

| :'''114'''. Simon Peter said to them, "Make Mary leave us, for females do not deserve life." Jesus said, "Look, I will guide her to make her male, so that she too may become a living spirit resembling you males. For every female who makes herself male will enter the kingdom of Heaven." | |||

| ====Syriac origin==== | |||

| Some scholars consider this gospel to be a ] text, since it was found in a library among other, more clearly gnostic texts. Others reject this interpretation, because ''Thomas'' lacks the full-blown mythology of Gnosticism as described by ] (ca. ]) or recognized by modern scholarship. Still other scholars see evidence of increasingly gnostic redactions over time when they compare sayings in the New Testament with parallel sayings in the Greek versions of the ''Gospel of Thomas'' (ca. 200), and sayings in the Coptic version (ca. 340). No major Christian group accepts it as canonical or authoritative. | |||

| Several scholars argue that Thomas is dependent on Syriac writings, including unique versions of the canonical gospels. They contend that many sayings of the Gospel of Thomas are more similar to Syriac translations of the canonical gospels than their record in the original Greek. ] states that saying 54 in Thomas, which speaks of the poor and the kingdom of heaven, is more similar to the Syriac version of Matthew 5:3 than the Greek version of that passage or the parallel in Luke 6:20.{{sfnp|Evans|2008|p={{Page needed|date=September 2010}} }} | |||

| ] notes that saying 65–66 of Thomas containing the ] appears to be dependent on the early harmonisation of Mark and Luke found in the old Syriac gospels. He concludes that, "''Thomas'', rather than representing the earliest form, has been shaped by this harmonizing tendency in Syria. If the ''Gospel of Thomas'' were the earliest, we would have to imagine that each of the evangelists or the traditions behind them expanded the parable in different directions and then that in the process of transmission the text was trimmed back to the form it has in the Syriac Gospels. It is much more likely that Thomas, which has a Syrian provenance, is dependent on the tradition of the canonical Gospels that has been abbreviated and harmonized by oral transmission."{{sfnp|Snodgrass|1989}} | |||

| The gospel is ostensibly written from the point of view of ], one of the twelve disciples of Jesus (who appears in the ] as "doubting Thomas"). It claims that special revelations and parables (recorded in the text) were made only to Thomas. However, the gospel is a collection of sayings and parables, which contains no narrative account of Jesus' life, something that all four canonical gospels include. | |||

| ] argues that Thomas is dependent on the '']'', which was composed shortly after 172 by ] in Syria.{{sfnp|Perrin|2006}} Perrin explains the order of the sayings by attempting to demonstrate that almost all adjacent sayings are connected by Syriac catchwords, whereas in Coptic or Greek, catchwords have been found for only less than half of the pairs of adjacent sayings.{{sfnp|Perrin|2002}} Peter J. Williams analyzed Perrin's alleged Syriac catchwords and found them implausible.{{sfnp|Williams|2009}} ] wrote that since Perrin attempts to reconstruct an ] version of Thomas without first establishing Thomas' reliance on the ''Diatessaron'', Perrin's logic seems ].{{sfnp|Shedinger|2003|p=388}} | |||

| This Gospel is important for scholars working on the ], which, like Thomas, is thought to be a collection of sayings or teachings. Although no copy of Q has ever been discovered, the fact that Thomas is a sayings Gospel is taken by some as indication that the early Christians did write collections of the sayings of Jesus, and thus they feel it renders the Q theory more credible. | |||

| ====Lack of apocalyptic themes==== | |||

| ==The Gospel of Thomas and the historical Jesus== | |||

| ] argues that the ] was an ] preacher, and that his apocalyptic beliefs are recorded in the earliest Christian documents: Mark and the authentic ]. The earliest Christians believed Jesus would soon return, and their beliefs are echoed in the earliest Christian writings. The Gospel of Thomas proclaims that the Kingdom of God is already present for those who understand the secret message of Jesus (saying 113), and lacks apocalyptic themes. Because of this, Ehrman argues, the Gospel of Thomas was probably composed by a Gnostic some time in the early 2nd century.{{sfnp|Ehrman|1999|pp=75–78}} Ehrman also argued against the authenticity of the sayings the Gospel of Thomas attributes to Jesus.{{sfnp|Ehrman|2012|p=219}} | |||

| Modern scholars use three criteria to determine what the historical Jesus may have taught: multiple attestations, dissimilarity, and contextual credibility. Many modern scholars believe that the Gospel of Thomas was written independently of the New Testament, and therefore, is a useful guide to historical Jesus research. | |||

| ] points out the Gospel of Thomas promulgates the Kingdom of God not as a final destination but a state of self-discovery. Additionally, the Gospel of Thomas conveys that Jesus ridiculed those who thought of the Kingdom of God in literal terms, as if it were a specific place. Pagels goes on to argue that, through saying 22, readers are to believe the "Kingdom" symbolizes a state of transformed consciousness.{{sfnp|Pagels|1979|pp=128-129}} | |||

| By finding those sayings in the ''Gospel of Thomas'' that overlap with Q, Mark, Matthew, Luke, John, and Paul, scholars feel such sayings represent "multiple attestations" and therefore are more likely to come from a historical Jesus than sayings that are only singly attested, such as the vast majority of the material in John. | |||

| ] has repeatedly argued against the historicity of the Gospel of Thomas, stating that it cannot be a reliable source for ] and also considers it a Gnostic text.{{sfnp|Meier|1991|p=110}} He has also argued against the authenticity of the parables found exclusively in the Gospel of Thomas.{{sfnp|Meier|2016|p={{page needed|date=July 2021}}}} ] included the Gospel of Thomas into his list of Gnostic scriptures.{{sfnp|Layton|1987|p={{page needed|date=July 2021}}}} | |||

| The ''Gospel of Thomas'' has also been used by Christ mythicist theorists such as ], author of ''The Jesus Puzzle'', and Timothy Freke, author of ''The Jesus Mysteries'', as evidence that Christianity did not originate with a ], but as a Jewish adaptation of the Greek ]s. The collection of teachings attributed to Jesus represent part of the initiation to the mysteries of their religion. | |||

| ] has argued that the Gospel of Thomas represents the theological motives of 2nd century Egyptian Christianity and is dependent on the Synoptic Gospels and the Diatesseron.{{sfnp|Evans|2008|p={{page needed|date=July 2021}}}} | |||

| The ''Gospel of Thomas'' is regarded by some individuals as the single most important find in understanding early Christianity outside the New Testament. It may attest to extraordinary diversity in early Christianity, and very different understandings of Jesus. It also may offer a window into the worldview of this ancient culture and a window of the debates and struggles within early Christianity, and its relationship and split with ]. | |||

| ], Anglican bishop and professor of New Testament history, also sees the dating of Thomas in the 2nd or 3rd century. Wright's reasoning for this dating is that the "narrative framework" of 1st-century Judaism and the New Testament is radically different from the worldview expressed in the sayings collected in the Gospel of Thomas. Thomas makes an anachronistic mistake by turning Jesus the Jewish prophet into a Hellenistic/Cynic philosopher. Wright concludes his section on the Gospel of Thomas in his book ''The New Testament and the People of God'' in this way: | |||

| ==Differences between translations== | |||

| In translating ancient texts, often the meaning of words is revealed only in abstraction, and must be transliterated, after being translated, in order for the meaning to be addressed. This is the case with all translations, as each reveals the limits and changes of languages, in the ''divergent'' tasks of; being sufficiently descriptive, and being easy to use in common speech. In the ''Gospel of Thomas'', logion 66 is one famous example of how translation often differs subtly in its proper transliteration. | |||

| {{blockquote| implicit story has to do with a figure who imparts a secret, hidden wisdom to those close to him, so that they can perceive a new truth and be saved by it. "The Thomas Christians are told the truth about their divine origins, and given the secret passwords that will prove effective in the return journey to their heavenly home." This is, obviously, the non-historical story of Gnosticism{{nbsp}} It is simply the case that, on good historical grounds, it is far more likely that the book represents a radical translation, and indeed subversion, of first-century Christianity into a quite different sort of religion, than that it represents the original of which the longer gospels are distortions{{nbsp}} Thomas reflects a symbolic universe, and a worldview, which are radically different from those of the early Judaism and Christianity.{{sfnp|Wright|1992|p=443}} }} | |||

| :'''66'''. ''Jesus said'', "Show me the stone that the builders rejected: that is the keystone." (''From the'' Scholars Translation - ''Stephen Patterson and Marvin Meyer.'') | |||

| ==Relation to the New Testament canon== | |||

| Compare the above translation to the below interpretation: | |||

| ] | |||

| Although arguments about some potential New Testament books, such as '']'' and the ], continued well into the 4th century, four canonical gospels, attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, were accepted among ] at least as early as the mid-2nd century. Tatian's widely used '']'', compiled between 160 and 175 AD, utilized the four gospels without any consideration of others. ] wrote in the late 2nd century that: "since there are four-quarters of the earth{{nbsp}} it is fitting that the church should have four pillars{{nbsp}} the four Gospels."<ref>{{cite book |author=] |title=] |at=3.11.8}}</ref> and then shortly thereafter made the first known quotation from a fourth gospel – the now-canonical version of the Gospel of John. The late 2nd-century ] also recognizes only the three synoptic gospels and John. | |||

| Bible scholar ] wrote regarding the formation of the New Testament canon: | |||

| :'''66'''. ''Jesus said'', "Teach me concerning this stone which the builders rejected; it is the corner-stone." (''Brill edition.'') | |||

| {{blockquote|Although the fringes of the emerging canon remained unsettled for generations, a high degree of unanimity concerning the greater part of the New Testament was attained among the very diverse and scattered congregations of believers not only throughout the Mediterranean world, but also over an area extending from Britain to Mesopotamia.{{sfnp|Metzger|1997|p=75}}}} | |||

| ==Relation to the Thomasine milieu== | |||

| The use of the word "corner-stone", in the Brill edition, is ''inaccurate'' for the meaning, and the correct word is "keystone", as in the Patterson-Meyer translation. To understand the difference, we must think through the parable for its intended meaning. As in all ] ], the deeper meaning reflects a moral story. In this case, the meaning comes by the analogy of constructing an arch: | |||

| The question also arises as to various sects' usage of other works attributed to Thomas and their relation to this work. | |||

| The ], also from Nag Hammadi, is foremost among these, but the extensive ] provides the mythological connections. The short and comparatively straightforward ] has no immediate connection with the synoptic gospels, while the canonical ] – if the name can be taken to refer to Judas Thomas Didymus – certainly attests to early intra-Christian conflict. | |||

| :In selecting stones for the arch, the most odd-shaped, useless stone is rejected, and cast aside. The builders select the ''cornerstones'' first; they must be strong, squarish blocks and must serve well as the foundation. As each separate pillar is built to the top, the stones are chosen for their slight curvatures, to bring the tops of the columns together. | |||

| The ], shorn of its mythological connections, is difficult to connect specifically to the Gospel of Thomas, but the Acts of Thomas contains the ] whose content is reflected in the ] found in ] literature. These psalms, which otherwise reveal ] connections, also contain material overlapping with the Gospel of Thomas.{{sfnp|Masing|Rätsep|1961}} | |||

| :Finally, the ''keystone'' must be selected. It must be of a particularly acute angle to accommodate the characteristics of each of the two arch halves: According to Jesus's parable, it is the stone which was first rejected, by the initial estimations of the builders, and only when the rest of the pieces are in place do they see its usefulness.{{fact}} | |||

| ==Relation to other Christian texts== | |||

| == Comparison of The ''Gospel of Thomas'' to the New Testament == | |||

| Scholars such as Sellew (2018) have also noted striking parallels between the Gospel of Thomas and '']''.<ref>Sellew, Melissa Harl. "Reading Jesus in the Desert. The Gospel of Thomas meets the ''Apophthegmata Patrum''", in ''The Nag Hammadi Library and Late Antique Egypt'', ed. Hugo Lundhaug and Lance Jenott. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2018, 81-106.</ref> | |||

| The ''Gospel of Thomas'' does not refer to Jesus as "Christ" or "Lord" as the New Testament does, but simply as "Jesus." The ''Gospel of Thomas'' also lacks any mention of such classic Christian doctrines as ], ]s, ], ], or ]. However, it includes several parables similar to ones found in the canonical gospels that contain themes including ], eternal damnation, ], the ], ] (instructing his followers to heal people), and ]. | |||

| ==Importance and author== | |||

| The ''Gospel of Thomas'' does not list the canonical twelve ]s, though it does mention ], who is singled out ("No matter where you are you are to go to James the Just, for whose sake heaven and earth came into being"); ]; ]; ], who is taken aside and receives three points of revelation; ]; and ]. Though here Mary Magdalene and Salome are mentioned among the disciples, the canonical Gospels and ''Acts'' only mention men, but make a distinction between "disciples" and the inner group of twelve "apostles" — a Greek term that does not appear in Thomas — with varying lists of names making up the canonical twelve. Despite the favorable mention of James the Just, generally considered a "pro-circumcision" Christian, the ''Gospel of Thomas'' also dismisses circumcision: | |||

| ] | |||

| Considered by some as one of the earliest accounts of the teachings of Jesus, the Gospel of Thomas is regarded by some scholars as one of the most important texts in understanding ] outside the ].{{sfnp|Funk|Hoover|1993|p=15}} In terms of faith, however, no major Christian group accepts this gospel as canonical or authoritative. It is an important work for scholars working on the Q document, which itself is thought to be a collection of sayings or teachings upon which the gospels of Matthew and Luke are partly based. Although no copy of Q has ever been discovered, the fact that Thomas is similarly a "sayings" gospel is viewed by some scholars as an indication that the early Christians did write collections of the sayings of Jesus, bolstering the Q hypothesis.{{sfnp|Ehrman|2003b|pp=57–58}} | |||

| Modern scholars do not consider Thomas the Apostle the author of this document and the author remains unknown. J. Menard produced a summary of the academic consensus in the mid-1970s that stated that the gospel was probably a very late text written by a Gnostic author, thus having very little relevance to the study of the early development of Christianity. Scholarly views of Gnosticism and the Gospel of Thomas have since become more nuanced and diverse.{{sfnp|DeConick|2006|pp=2–3}} Paterson Brown, for example, has argued forcefully that the three Coptic Gospels of Thomas, ] and ] are demonstrably not Gnostic writings, since all three explicitly affirm the basic reality and sanctity of incarnate life, which Gnosticism by definition considers illusory and evil.{{sfnp|Paterson Brown|n.d.}} | |||

| :''His disciples said to him,'' "Is circumcision useful or not?" ''He said to them,'' "If it were useful, their father would produce children already circumcised from their mother. Rather, the true circumcision in spirit has become profitable in every respect." | |||

| In the 4th century ] considered the author a disciple of ] who was also called Thomas.{{sfnp|Schneemelcher|2006|p=111}} Cyril stated: | |||

| Compare Thomas 8 SV | |||

| {{blockquote|Mani had three disciples: Thomas, Baddas and Hermas. Let no one read the Gospel according to Thomas. For he is not one of the twelve apostles but one of the three wicked disciples of Mani.{{sfnp|Layton|1989|p=106}} }} | |||

| Many scholars consider the Gospel of Thomas to be a gnostic text, since it was found in a library among others, it contains Gnostic themes, and perhaps presupposes a Gnostic worldview.{{sfnp|Ehrman|2003b|pp=59ff}} Others reject this interpretation, because Thomas lacks the full-blown mythology of Gnosticism as described by ] ({{c.|185}}), and because Gnostics frequently appropriated and used a large "range of scripture from Genesis to the Psalms to Homer, from the Synoptics to John to the letters of Paul."{{sfnp|Davies|1983b|pp=6–8}} The mysticism of the Gospel of Thomas also lacks many themes found in second century Gnosticism,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Foster |first=Paul |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JqgSDAAAQBAJ&dq=Thomasines+christology&pg=PA39 |title=The Apocryphal Gospels: A Very Short Introduction |date=2009-02-26 |publisher=OUP Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-923694-7 |language=en}}</ref> including any allusion to a fallen ] or an evil ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=van den Broek |first1=Roelof |title=Gnostic Religion in Antiquity |date=2013 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |page=38}}</ref> According to David W. Kim, the association of the Thomasines and Gnosticism is anachronistic and the book seems to predate the Gnostic movements.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kim |first=David W. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F6ouEAAAQBAJ&dq=Thomasines+ascetism&pg=PA86 |title=The Words of Jesus in the Gospel of Thomas: The Genesis of a Wisdom Tradition |date=2021-07-01 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-000-37762-0 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| :'''8'''. ''And Jesus said'', "The person is like a wise fisherman who cast his net into the sea and drew it up from the sea full of little fish. Among them the wise fisherman discovered a fine large fish. He threw all the little fish back into the sea, and easily chose the large fish. Anyone here with two good ears had better listen!" | |||

| ==The historical Jesus== | |||

| with {{bibleref|Matthew|13:47–50}} NIV: | |||

| Some modern scholars (most notably those belonging to the ]) believe that the Gospel of Thomas was written independently of the canonical gospels, and therefore is a useful guide to ] research.{{sfnp|Funk|Hoover|1993|p=15}}{{sfnp|Koester|1990|pp=84–86}} Scholars may utilize one of several critical tools in ], the ], to help build cases for historical reliability of the sayings of Jesus. By finding those sayings in the Gospel of Thomas that overlap with the ], Q, Mark, Matthew, Luke, John, and Paul, scholars feel such sayings represent "multiple attestations" and therefore are more likely to come from a historical Jesus than sayings that are only singly attested.{{sfnp|Funk|Hoover|1993|pp=16ff}} However, ] states that the Gospel of Thomas has very little value in historical Jesus research, because the author placed no importance on the physical experiences of Jesus (e.g. his crucifixion) or the physical existence of believers.<ref>''Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium'' by Bart D. Ehrman 2001 {{ISBN|019512474X}} pp. 72–78</ref> | |||

| == Representation of women == | |||

| :<sup>47</sup>"Once again, the kingdom of heaven is like a net that was let down into the lake and caught all kinds of fish. <sup>48</sup>When it was full, the fishermen pulled it up on the shore. Then they sat down and collected the good fish in baskets, but threw the bad away. <sup>49</sup>This is how it will be at the end of the age. The angels will come and separate the wicked from the righteous <sup>50</sup>and throw them into the fiery furnace, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth." | |||

| Interpretations of the Gospel of Thomas's view of women vary widely, with some arguing that it is chauvinistic, while others view it as comparatively positive.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Marjanen |first=Antti |title=Thomas at the Crossroads: Essays on the Gospel of Thomas |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |year=2000 |editor-last=Uro |editor-first=Risto |location=London |pages=89 |chapter=Women Disciples in the Gospel of Thomas}}</ref> | |||

| === Women disciples === | |||

| Note that Thomas makes a distinction between large and small fishes, whereas Matthew makes a distinction between good and bad fishes. Furthermore, Thomas' version has only one fish remaining, whereas Matthew's version implies many good fish remaining. The manner in which each Gospel concludes the parable is instructive. Thomas' version invites the reader to draw their own conclusions as to the interpretation of the saying, whereas Matthew provides an explanation connecting the text to an apocalyptic end of the age. | |||

| The Gospel of Thomas names six people who are close to Jesus and, of these, two are the women disciples ] and ].<ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last=Marjanen |first=Antti |title=Thomas at the Crossroads: Essays on the Gospel of Thomas |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |year=2000 |editor-last=Uro |editor-first=Risto |location=London |pages=90 |chapter=Women Disciples in the Gospel of Thomas}}</ref> Professor Antti Marjanen suggests that their inclusion is significant and purposeful because of how few people are named.<ref name=":2" /> He argues that, in logio 61 and 21, their discussions with Jesus clarify the nature of discipleship. They are shown not as "ones who misunderstand, but as ones who do not quite understand enough."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Marjanen |first=Antti |title=Thomas at the Crossroads: Essays on the Gospel of Thomas |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |year=2000 |editor-last=Uro |editor-first=Risto |location=London |pages=92 |chapter=Women Disciples in the Gospel of Thomas}}</ref> This is shown to be the case for all of the disciples and Marjanen states that "Mary Magdalene's or Salome's lack of understanding should not be overemphasized."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Marjanen |first=Antti |title=Thomas at the Crossroads: Essays on the Gospel of Thomas |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |year=2000 |editor-last=Uro |editor-first=Risto |location=London |pages=93 |chapter=Women Disciples in the Gospel of Thomas}}</ref> | |||

| === Logion 114 === | |||

| Another example is the ], which is paralleled by Matthew, Luke, John, and Thomas. | |||

| {{blockquote|Simon Peter said to them, "Mary should leave us, for females are not worthy of the life." Jesus said, "Look, I am going to guide her in order to make her male, so that she too may become a living spirit resembling you males. For every female who makes herself male will enter the kingdom of heaven."|''Logion'' 114}} | |||

| The final saying of the Gospel of Thomas is one of the most controversial and has been highly debated by academics.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Marjanen |first=Antti |title=Thomas at the Crossroads: Essays on the Gospel of Thomas |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |year=2000 |editor-last=Uro |editor-first=Risto |location=London |pages=95 |chapter=Women Disciples in the Gospel of Thomas}}</ref> It has been criticised for implying that women are spiritually inferior, but some scholars argue that it is symbolic, with "male" representing the prelapsarian state.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last=Buckley |first=Jorunn Jacobsen |date=1985 |title=An Interpretation of Logion 114 in "The Gospel of Thomas" |journal=Novum Testamentum |volume=27 |issue=3}}</ref> ] argued that Logion 114 represents a process with females becoming male before achieving the prelapsarian state, a reversal of the Genesis story in which women were made from men.<ref name=":1" /> Melissa Harl Sellew's trans-centred reading emphasizes the idea that the outer appearance must be transformed to reflect the inner reality.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Sellew |first=Melissa Harl |title=Reading the Gospel of Thomas from Here: A Trans-Centred Hermeneutic |url=https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:29255/ |journal=Journal for Interdisciplinary Biblical Studies |date=2020 |language=en-US |pages=89 |doi=10.17613/4etz-b919}}</ref> | |||

| This is the parable of the lost sheep in {{bibleref|Matthew|18:12–14}} NIV | |||

| ==Comparison of the major gospels== | |||

| :<sup>12</sup>"What do you think? If a man owns a hundred sheep, and one of them wanders away, will he not leave the ninety-nine on the hills and go to look for the one that wandered off? <sup>13</sup>And if he finds it, I tell you the truth, he is happier about that one sheep than about the ninety-nine that did not wander off. <sup>14</sup>In the same way your Father in heaven is not willing that any of these little ones should be lost." | |||

| The material in the comparison chart is from ''Gospel Parallels'' by B. H. Throckmorton,{{sfnp|Throckmorton|1979}} ''The Five Gospels'' by R. W. Funk,{{sfnp|Funk|Hoover|1993}} ''The Gospel According to the Hebrews'' by E. B. Nicholson{{sfnp|Nicholson|1879}} and ''The Hebrew Gospel and the'' ''Development of the Synoptic Tradition'' by J. R. Edwards.{{sfnp|Edwards|2009}} | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| This is the parable of the lost sheep in Luke 15: 3-7 NIV | |||

| :<sup>3</sup>''Then Jesus told them this parable:'' <sup>4</sup>"Suppose one of you has a hundred sheep and loses one of them. Does he not leave the ninety-nine in the open country and go after the lost sheep until he finds it? <sup>5</sup>And when he finds it, he joyfully puts it on his shoulders <sup>6</sup>and goes home. Then he calls his friends and neighbors together and says, 'Rejoice with me; I have found my lost sheep.' <sup>7</sup>I tell you that in the same way there will be more rejoicing in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who do not need to repent." | |||

| This is the parable of the lost sheep in Thomas 107 SV | |||

| :'''107'''. ''Jesus said,'' "The kingdom is like a shepherd who had a hundred sheep. One of them, the largest, went astray. He left the ninety-nine and looked for the one until he found it. After he had toiled, he said to the sheep, ''I love you more than the ninety-nine.''" | |||

| This is the parable of the lost sheep in John 10: 1-18 NIV | |||

| <blockquote><sup>1</sup>"I tell you the truth, the man who does not enter the sheep pen by the gate, but climbs in by some other way, is a thief and a robber. <sup>2</sup>The man who enters by the gate is the shepherd of his sheep. <sup>3</sup>The watchman opens the gate for him, and the sheep listen to his voice. He calls his own sheep by name and leads them out. <sup>4</sup>When he has brought out all his own, he goes on ahead of them, and his sheep follow him because they know his voice. <sup>5</sup>But they will never follow a stranger; in fact, they will run away from him because they do not recognize a stranger's voice." <sup>6</sup>Jesus used this figure of speech, but they did not understand what he was telling them. | |||

| <sup>7</sup>Therefore Jesus said again, "I tell you the truth, I am the gate for the sheep. <sup>8</sup>All who ever came before me were thieves and robbers, but the sheep did not listen to them. <sup>9</sup>I am the gate; whoever enters through me will be saved. He will come in and go out, and find pasture. <sup>10</sup>The thief comes only to steal and kill and destroy; I have come that they may have life, and have it to the full. | |||

| <sup>11</sup>"I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep. <sup>12</sup>The hired hand is not the shepherd who owns the sheep. So when he sees the wolf coming, he abandons the sheep and runs away. Then the wolf attacks the flock and scatters it. <sup>13</sup>The man runs away because he is a hired hand and cares nothing for the sheep. | |||