| Revision as of 19:15, 19 April 2015 view sourceRua (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users7,764 edits Undid revision 657220057 by 217.118.81.17 (talk)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:18, 2 January 2025 view source Celco85 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users3,011 edits Enhanced photo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Peninsula in Europe}} | |||

| {{Other uses|Crimea (disambiguation)}} | {{Other uses|Crimea (disambiguation)}} | ||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Coord|45.3|34.4|scale:2000000|display=title}} | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=August 2015}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2022}} | |||

| {{Infobox peninsulas | {{Infobox peninsulas | ||

| |name=Crimean Peninsula | | name = Crimean Peninsula | ||

| | local_name = | |||

| |local name= | |||

| | image_name = ]<br>Map of the Crimean Peninsula <br /><br /> {{Switcher|]|Flag of the ]|]|Flag of the ]}} | |||

| |image name=Satellite image of Crimea.png | |||

| | image_alt = | |||

| |image caption=Satellite image of the Crimean peninsula | |||

| | map_image = Crimea (orthographic projection).svg | |||

| |image size=239px | |||

| | map_size = 220 | |||

| |image alt= | |||

| | location = ] | |||

| |locator map=Crimea (orthographic projection).svg | |||

| | waterbody = {{ubl|]|]}} | |||

| |locator map size =239px | |||

| | coordinates = {{Coord|45.3|34.4|scale:2000000_region:UA-43|display=inline,title}} | |||

| |location = Eastern Europe | |||

| | area_km2 = 27000 | |||

| |waterbody = <div>]<br>]</div> | |||

| | highest_mount = ] | |||

| {{Infobox|child=yes | |||

| | elevation_m = 1545 | |||

| | rowclass1 = mergedrow | |||

| | country = {{sp}} | |||

| | label1 = Largest city | |||

| | country_admin_divisions_title = ] | |||

| | data1 = ] | |||

| | country_admin_divisions = ] as Ukrainian territory occupied by ] (''see ]'') | |||

| }} | |||

| | country1 = <!--Note: Do not add flag icons for geographic articles per MOS:INFOBOXFLAG-->Ukraine (de jure but not in control) | |||

| |coordinates = {{Coord|45.3|34.4|scale:2000000|display=inline}} | |||

| | country1_admin_divisions_title = ] regions | |||

| |area_km2 = 27000 | |||

| | country1_admin_divisions_1 = Northern Arabat Spit (])<br />]<br />] | |||

| |highest mount = | |||

| | country1_largest_city = ] | |||

| |elevation_m = 1545 | |||

| | country2 = <!--Note: Do not add flag icons for geographic articles per MOS:INFOBOXFLAG-->Russia (de facto control) | |||

| |Country heading = ] | |||

| | country2_admin_divisions_title = ] regions | |||

| |country = Russia<br>{{nobold|(''de facto'' administration)}} | |||

| | country2_admin_divisions_1 = ]<br />] | |||

| |country admin divisions title = ] | |||

| | country2_largest_city = ] | |||

| |country admin divisions = {{nowrap|]}} | |||

| | demonym = ] | |||

| |country admin divisions title 1 = ] | |||

| | population = {{increase}} 2,416,856<ref name="pop">{{cite web|url=https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/of43wDjn/PrPopul2021_Site.xls|format=XLS|script-title=ru:Численность населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2021 года|trans-title=The population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2021|language=ru|work=]|access-date=31 January 2021|archive-date=4 February 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210204121301/https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/of43wDjn/PrPopul2021_Site.xls|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| |country admin divisions 1 = {{nowrap|]}}<br>]<ref>{{cite web|title=Treaty to accept Crimea, Sevastopol to Russian Federation signed|url=http://rt.com/news/putin-include-crimea-sevastopol-russia-578/|work=rt.com|publisher=Autonomous Nonprofit Organization "TV-Novosti"|accessdate=24 March 2014|date=March 18, 2014}}</ref> | |||

| | population_as_of = 2021 | |||

| |country 1 = ]<br>{{nobold|(])}} | |||

| | utc_offset = +3 | |||

| |country 1 admin divisions title = ] | |||

| | density_km2 = 84.6 | |||

| |country 1 admin divisions = ]<br>]<br />] <small>(northern part of ], ])</small> | |||

| | iso_code = UA-43 | |||

| |density_km2 = | |||

| |demonym = ] | |||

| |population = 2.4 million{{citation needed|date=July 2014}} | |||

| |population as of=2007 | |||

| |ethnic groups=]<br />]<br />] | |||

| |additional info= | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The '''Crimean Peninsula''' (<!-- NOTE: Russian is listed first because it is the predominant language of the region; languages are listed in order of percent of users in region -->{{lang-ru|link=no|Кры́мский полуо́стров}}, {{lang-uk|Кри́мський піво́стрів}}, {{lang-crh|Къырым ярымадасы}}), also known simply as '''Crimea''' ({{lang-ru|link=no|Крым}}, {{lang-uk|Крим}}, {{lang-crh|Къырым}}), is a major land mass on the northern coast of the ] that is almost completely surrounded by water. The ] is located south of the ] region of ] and west of the Russian region of ]. It is surrounded by two seas: the Black Sea and the smaller ] to the northeast. It is connected to Kherson by the ] and is separated from Kuban by the ]. The ] is located to the northeast; a narrow strip of land that separates a system of lagoons named ] from the ]. | |||

| '''Crimea'''{{efn|{{bulleted list|{{langx|ru|Крым|Krym}}|{{langx|uk|Крим|Krym}}|{{crh|Qırım|Къырым}}|{{langx|grc|Κιμμερία, Ταυρική|translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ}}}}}} ({{IPAc-en|audio=Crimea pronunciation.mp3|k|r|aɪ|ˈ|m|iː|ə}} {{Respell|kry|MEE|ə}}) is a ] in ], on the northern coast of the ], almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller ]. The ] connects the peninsula to ] in mainland ]. To the east, the ], constructed in 2018, spans the ], linking the peninsula with ] in ]. The ], located to the northeast, is a narrow strip of land that separates the ] lagoons from the Sea of Azov. Across the Black Sea to the west lies Romania and to the south is Turkey. The population is 2.4 million,<ref name="pop"/> and the largest city is ]. The region has been under ]. | |||

| Crimea—or the ''']c Peninsula''', as it was formerly known—has historically been at the boundary between the ] and the ]. Its southern fringe was colonised by the ], the ], the ], the ], the ] and the ], while at the same time its interior was occupied by a changing cast of invading ], such as the ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and the ]. Crimea and adjacent territories were united in the ] during the 15th to 18th century before falling to the ] and being included into the Russian ] in 1802. | |||

| Called the '''Tauric Peninsula''' until the ], Crimea has historically been at the boundary between the ] and the ]. ] colonized its ] and were absorbed by the ] and ] Empires and ] ] while remaining culturally Greek. Some cities became trading colonies of ], until conquered by the ]. Throughout this time the interior was occupied by a ] of ], coming under the control of the ] in the 13th century from which the ] emerged as a successor state. In the 15th century, the Khanate became a dependency of the Ottoman Empire. Lands controlled by Russia{{efn|Russia underwent a series of political changes in the period of the raids. The ] overthrew Turco-Mongol lordship, and expanded into the ] in 1547. From 1721, following the reforms of Peter the Great, it was the ].}} and ] were often the target of ] during this period. In 1783, after the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774), the ] ]. Crimea's strategic position led to the 1854 ] and ] following the 1917 ]. When the ]s secured Crimea, it became an ] within the ]. It was ]. When the Soviets retook it in 1944, ] were ] under the orders of ], in what has been described as a cultural genocide. Crimea was downgraded to ] in 1945. In 1954, the USSR ] to the ] on the 300th anniversary of the ] in 1654. | |||

| After the ] of 1917, Crimea became a ] within the ] in the ]. In ] it was downgraded to the ], and in 1954, the Crimean Oblast was ] to the ]. It became the ] within newly independent Ukraine in 1991, with ] having its own administration, within Ukraine but outside of the Autonomous Republic. Sovereignty and control of the peninsula became the subject of an ongoing territorial ] between Russia and Ukraine, with Russia signing a ] in March 2014 with the self-declared independent ], absorbing it into the ], though this is not recognised by Ukraine or most of the international community.<ref name="theguardian.com">{{cite news|author=Alec Luhn|url=http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/18/red-square-rally-vladimir-putin-crimea|title=Red Square rally hails Vladimir Putin after Crimea accession|work=The Guardian|location=Moscow|date=18 March 2014|accessdate=24 December 2014}}</ref> | |||

| After Ukrainian independence in 1991, the central government and the ] clashed, with the region being granted ]. The ] in Crimea was also ], but a ] allowed Russia to continue basing its fleet in Sevastopol. In 2014, the peninsula was ] by ] and ], but most countries ] as Ukrainian territory.<ref name="INTLCOM">{{Cite web |date=23 August 2021 |title=Ukraine's president pledges to 'return' Russia-annexed Crimea |url=https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/8/23/ukraines-president-pledges-to-return-russia-annexed-crimea |access-date=2024-06-27 |website=] |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ==Name== | ==Name== | ||

| In English, the omission of the definite article ("Crimea" rather than "the Crimea") became common during the later 20th century.{{citation needed|date=November 2014}} | |||

| {{Further|Stary Krym}} | |||

| The spelling "Crimea" is from the Italian form, {{Langx|it|la Crimea|label=none}}, since at least the 17th century<ref>Maiolino Bisaccioni, Giacomo Pecini, ''Historia delle guerre ciuili di questi vltimi tempi, cioe, d'Inghilterra, Catalogna, Portogallo, Palermo, Napoli, Fermo, Moldauia, Polonia, Suizzeri, Francia, Turco''. per Francesco Storti. Alla Fortezza, sotto il portico de' Berettari, 1655, : "dalla fortuna de Cosacchi dipendeva la sicurezza della Crimea". Nicolò Beregani, ''Historia delle guerre d'Europa'', Volume 2 (1683), .</ref> and the "Crimean peninsula" becomes current during the 18th century, gradually replacing the classical name of ''Tauric Peninsula'' in the course of the 19th century.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oY1h2Pa1kaUC&pg=PA364 |title=The Annual Register or a View of the History, Politics, and Literature for the Year 1783 |publisher=J. Dodsley |year=1785 |isbn=9781615403851 |page=364 |chapter=State Papers}}</ref>{{Better source needed|reason=this primary source doesn’t directly support the statement|date=December 2023}} In English usage since the ] the Crimean Khanate is referred to as ''Crim Tartary''.<ref>], '']'', Volume 1, "the peninsula of Crim Tartary, known to the ancients under the name of Chersonesus Taurica"; ibid. Volume 10 (1788), p. 211: "The modern reader must not confound this old Cherson of the Tauric or Crimean peninsula with ] of the same name". See also John Millhouse, ''English-Italian'' (1859), </ref> | |||

| The classical name '']'' or '']'' is from the Greek Ταυρική, after the peninsula's Scytho-Cimmerian inhabitants, the ]. ] and ] refer to the ] as the ''Bosporus Cimmerius'', and to ''Cimmerium'' as the capital of the Taurida, whence the peninsula, or its ], was also named ''Promontorium Cimmerium''.<ref name="history1779">{{cite book|author=Compiled from original authors|title=An Universal History, from the Earliest Accounts to the Present Time|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=CCsIAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA129|accessdate=1 April 2015|year=1779|pages=127–129|chapter=The History of the Bosporus}}</ref> | |||

| Today, the Crimean Tatar name of the peninsula is ''Qırım'', while the Russian is Крым (''Krym''), and the Ukrainian is Крим (''Krym'').<ref>{{Cite news |last=Taylor |first=Adam |date=2021-12-01 |title=To understand Crimea, take a look back at its complicated history |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2014/02/27/to-understand-crimea-take-a-look-back-at-its-complicated-history/ |access-date=2024-07-24 |newspaper=Washington Post |language=en-US |issn=0190-8286}}</ref> | |||

| In English, the Crimean Khanate is referred to as ''Crim Tartary'' in the early modern period.<ref>], '']'', Volume 1, "the peninsula of Crim Tartary, known to the ancients under the name of Chersonesus Taurica"; ibid. Volume 10 (1788), p. 211: "The modern reader must not confound this old Cherson of the Tauric or Crimean peninsula with ] of the same name". | |||

| see also John Millhouse, ''English-Italian'' (1859), </ref> | |||

| The Italian<ref>''la Crimea'' since at least the 17th century. Maiolino Bisaccioni, Giacomo Pecini, ''Historia delle guerre ciuili di questi vltimi tempi, cioe, d'Inghilterra, Catalogna, Portogallo, Palermo, Napoli, Fermo, Moldauia, Polonia, Suizzeri, Francia, Turco''. per Francesco Storti. Alla Fortezza, sotto il portico de'Berettari, 1655, : "dalla fortuna de Cosacchi dipendeva la sicurazza della Crimea". | |||

| Nicolò Beregani, ''Historia delle guerre d'Europa'', Volume 2 (1683), .</ref> form ''Crimea'' (and "Crimean peninsula") also becomes current during the 18th century,<ref>{{cite book|title=The Annual Register or a View of the History, Politics, and Literature for the Year 1783|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=oY1h2Pa1kaUC&pg=PA364|accessdate=1 April 2015|year=1785|publisher=J. Dodsley|page=364|chapter=State Papers}}</ref> | |||

| gradually replacing the classical name of ] in the course of the 19th century. | |||

| The omission of the definite article in English ("Crimea" rather than "the Crimea") becomes common during the later 20th century.{{citation needed|date=November 2014}} | |||

| The city '']'' ('Old Crimea'),<ref>William Smith, ''Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography'' (1854), s.v. ''Taurica Chersonesus''. vol. ii, p. 1109.</ref> served as a capital of the Crimean province of the ]. Between 1315 and 1329 CE, the Arab writer ] recounted a political fight in 1300–1301 CE which resulted in a rival's decapitation and his head being sent "to the Crimea",<ref>Abū al-Fidā, Mukhtaṣar tāʾrīkh al-bashar (]), 1315–1329; English translation of chronicle contemporaneous with Abū al-Fidā in ''The Memoirs of a Syrian Prince : Abul̓-Fidā,̕ sultan of Ḥamāh (672-732/1273-1331)'' by Peter M. Holt, Franz Steiner Verlag, 1983, pp. 38–39.</ref> apparently in reference to the peninsula,<ref>Edward Allworth, ''The Tatars of Crimea: Return to the Homeland: Studies and Documents'', Duke University Press, 1998, p.6</ref> although some sources hold that the name of the capital was extended to the entire peninsula at some point during ] (1441–1783).<ref>], ''Versuch eines Wörterbuches der Türk-Dialecte'' (1888), ii. 745</ref> | |||

| The name "Crimea" ultimately, via Italian, takes its origin with the name of ''Qırım'' (today's '']'') which served as a capital of the Crimean province of the ]. | |||

| The name of the capital was extended to the entire peninsula at some point during ].<ref>], ''Versuch eines Wörterbuches der Türk-Dialecte'' (1888), ii. 745</ref> | |||

| The origin of the name ''Qırım'' itself is uncertain. It is mostly explained as: | |||

| # a corruption of ''Cimmerium''.<ref>{{cite book|author=Encyclopaedia Britannica|title=Encyclopædia Britannica: or, A dictionary of arts and sciences, compiled by a society of gentlemen in Scotland [ed. by W. Smellie]. Suppl. to the 3rd. ed., by G. Gleig|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=RGMIAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA153|accessdate=1 April 2015|year=1810|page=153}}<br>{{cite book|author1=Alexander MacBean|authorlink1=Alexander MacBean|author2=Samuel Johnson|title=A Dictionary of Ancient Geography: Explaining the Local Appellations in Sacred, Grecian, and Roman History; Exhibiting the Extent of Kingdoms, and Situations of Cities, &c. And Illustrating the Allusions and Epithets in the Greek and Roman Poets. The Whole Established by Proper Authorities, and Designed for the Use of Schools|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=EqwBAAAAYAAJ&pg=PT185|accessdate=1 April 2015|year=1773|publisher=G. Robinson|page=185}}</ref> | |||

| # a derivation from the ] ''Cremni'' (κρήμνοι ''kremnoi'' "cliffs", mentioned in ] 4.20). | |||

| # a derivation from the ] appellation<ref>Adrian Room, ''Placenames of the World'', 2003, . {{cite book|last=Asimov|first=Isaac|title=Asimov's Chronology of the World|year=1991|publisher=HarperCollins|location=New York|page=50}}. See also William Smith, ''Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography'', 1854</ref> ''kerm'' designating "wall", which, however, is phonetically incompatible with the original Mongolian literal appellation of the Crimean peninsula ''Qaram'',<ref name="Allworth">Edward Allworth, '''', Duke University Press, 1998, pp. 5-7</ref> | |||

| # a derivation from the ] ] appellation ''Qırım'' designating "fortress" or "fosse", from the Turkic term ''qurum'' ("defence, protection"), ''qurimaq'' ("to fence, protect").<ref name="Allworth"/><ref>George Vernadsky, Michael Karpovich, '''', Yale University Press, 1952, . Quote: | |||

| *"''The name Crimea is to be derived from the Turkish word '''qirim''' (hence the Russian ''krym''), which means "fosse" and refers more specifically to the '''Perekop Isthmus''', the old Russian word '''perekop''' being an exact translation of the Turkish '''qirim'''.''"</ref><ref>, BRILL, 2011, p.753</ref> | |||

| <!--Κριμαία ?--> | |||

| The word {{crh|Qırım|lead=no}} is derived from the ] term {{transliteration|crh|qirum}} ("fosse, trench"), from {{transliteration|crh|qori-}} ("to fence, protect").<ref>George Vernadsky, Michael Karpovich, '''', Yale University Press, 1952, . "The name Crimea is to be derived from the Turkish word ''qirim'' (hence the Russian ''krym''), which means "fosse" and refers more specifically to the Perekop Isthmus, the old Russian word ''perekop'' being an exact translation of the Turkish ''qirim''."</ref><ref>The Proto-Turkic root is cited as *''kōrɨ-'' "to fence, protect" ] (citing Севортян Э. В. и др. , '' Этимологический словарь тюркских языков'' (1974–2000) 6, 76–78).</ref><ref>Edward Allworth, '''', Duke University Press, 1998, pp. 5–7</ref> | |||

| The classical name was revived in the name of the Russian ].<ref>Edith Hall, ''Adventures with Iphigenia in Tauris'' (2013), : | |||

| "it was indeed at some point between the 1730s and the 1770s that the dream of recreating ancient 'Taurida' in the southern Crimea was conceived. ]'s plan was to create a paradisiacal imperial 'garden' there, and her Greek archbishop ] obliged by inventing a new etymology for the old name of Tauris, deriving it from ''taphros'', which (he claimed) was the ancient Greek for a ditch dug by human hands."</ref> | |||

| Another classical name for Crimea, '']'' or ''Taurica'', is from the Greek Ταυρική (''Taurikḗ''), after the peninsula's Scytho-Cimmerian inhabitants, the ]. The name was revived by the Russian Empire during the mass hellenization of ] place names after the ], including both the peninsula and mainland territories now in Ukraine's Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts.<ref>], ''Adventures with Iphigenia in Tauris'' (2013), : | |||

| While it was abandoned in the Soviet Union, and has had no official status since 1921, it is still used by some institutions in Crimea, such as the ], or the ]. | |||

| "it was indeed at some point between the 1730s and the 1770s that the dream of recreating ancient 'Taurida' in the southern Crimea was conceived. ]'s plan was to create a paradisiacal imperial 'garden' there, and her Greek archbishop ] obliged by inventing a new etymology for the old name of Tauris, deriving it from ''taphros'', which (he claimed) was the ancient Greek for a ditch dug by human hands."</ref> In 1764 imperial authorities established the ] ({{Transliteration|ru|Tavricheskaia oblast}}), and reorganized it as the ] in 1802. While the Soviets replaced it with ''Krym'' ({{langx|uk|Крим}}; {{langx|ru|Крым}}) depriving it of official status since 1921, it is still used by some institutions in Crimea, such as the ] established by the ] in 1918, the ] so named in 1963, and the ] being built under ] from 2017. | |||

| Other suggestions either unsupported or contradicted by sources, apparently based on similarity in sound, include: | |||

| # the name of the ], although this derivation is however no longer generally held.{{sfn|Sulimirski|Taylor|1991|p=558}} | |||

| # a derivation from the ] ''Cremnoi'' (Κρημνοί, in post-classical ] pronunciation, ''Crimni'', i.e., "the Cliffs", a port on ] (Sea of Azov) cited by ] in ''The Histories'' 4.20.1 and 4.110.2).<ref>A. D. (Alfred Denis) Godley. ''Herodotus''. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. vol. 2, 1921, p. 221.</ref> However, Herodotus identifies the port not in Crimea, but as being on the west coast of the Sea of Azov. No evidence has been identified that this name was ever in use for the peninsula. | |||

| <!--Κριμαία ?--> | |||

| <!--Κριμαία is the Modern Greek rendering of the Italian form--> | |||

| # The Turkic term (e.g., in {{Langx|tr|Kırım}}) is related to the ] appellation ''kerm'' "wall", but sources indicate that the Mongolian appellation of the Crimean peninsula of ''Qaram'' is phonetically incompatible with ''kerm/kerem'' and therefore deriving from another original term.<ref>See ], specialist in the studies of Chuvash, Yakut, and the Mongolian languages in Edward Allworth, '''', Duke University Press, 1998, p. 24.</ref><ref>, BRILL, 2011, p.753, n. 102.</ref><ref>The Mongolian ''kori<sup>−</sup>'' is explained as a loan from Turkic by Doerfer ''Türkische und mongolische Elemente im Neupersischen'' 3 (1967), 450 and by Щербак, ''Ранние тюркско-монгольские языковые связи (VIII-XIV вв.)'' (1997) p. 141.</ref> | |||

| <!-- you give two references. Who is arguing this, and is it an original argument or are they citing someone??--> | |||

| <!--if ''kori<sup>−</sup>'' is a loan word into Mongolian, it cannot be of Mongolian origin. This is consistent with above.-->] (''Geography'' vii 4.3, xi. 2.5), ], (''Histories'' 4.39.4), and ] (''Geographia''. II, v 9.5) refer variously to the ] as the Κιμμερικὸς Βόσπορος (''Kimmerikos Bosporos'', romanized spelling: ''Bosporus Cimmerius''), its ] as the Κιμμέριον Ἄκρον (''Kimmerion Akron'', Roman name: Promontorium Cimmerium),<ref name="history1779">{{cite book |author=Compiled from original authors |title=An Universal History, From the Earliest Accounts to the Present Time |year=1779 |pages=127–129 |chapter=The History of the Bosporus |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CCsIAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA129}}</ref> as well as to the city of ] and thence the name of the ] (Κιμμερικοῦ Βοσπόρου). | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| ]]] | |||

| ], built in 1912 for oil millionaire Baron von Steingel, a landmark of Crimea]] | |||

| {{main|History of Crimea}} | {{main|History of Crimea}} | ||

| ]]] | |||

| In ancient times, it was the home of ] and ], as well as the site of ]. The most important city was ] at the edge of today's Sevastopol. | |||

| ===Ancient history=== | |||

| Later occupiers included the ], ], ], ], ], the state of ], the ], the ], and the ]. In the 13th century CE, portions were controlled by the ] and by the ]. | |||

| {{further|Bosporan Kingdom|Greeks in pre-Roman Crimea|Crimea in the Roman era}} | |||

| The recorded history of Crimea begins around 5th century BCE when several ] were established on its ], the most important of which was ] near modern-day ], with ] and ] in the hinterland to the north. The Tauri gave the name the Tauric Peninsula, which Crimea was called into the ]. The southern coast gradually consolidated into the ] which was annexed by ] in Asia Minor and later became a ] of ] from 63 BCE to 341 CE. | |||

| In the 9th century CE, Byzantium established the ] to fend against incursions by the ], and the Crimean peninsula from this time was contested between Byzantium, Rus' and ]. The area remained the site of overlapping interests and contact between the early medieval Slavic, Turkic and Greek spheres, and became a center of ], ] were sold to Byzantium and other places in Anatolia and the Middle-East during this period. In the 1230s, this status quo was swept away by the ], and Crimea was incorporated into the territory of the ] throughout the 14th century CE. | |||

| ===Medieval history=== | |||

| ] (Սուրբ Խաչ), established in 1358]] | |||

| ], 13th century, ], originally a fortified ] town, seventh century]] | |||

| The south coast remained Greek in culture for almost two thousand years including under Roman successor states, the ] (341–1204 CE), the ] (1204–1461 CE), and the independent ] (ended 1475 CE). In the 13th century, some Crimean port cities were controlled by the ] and by the ], but the interior was much less stable, enduring a ]. In the medieval period, it was partially conquered by ] whose ] was baptized at ] starting the ].<ref name="Norwich2013">{{cite book|author=John Julius Norwich|title=A Short History of Byzantium|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7JtvMQEACAAJ|year=2013|publisher=Penguin Books, Limited|isbn=978-0-241-95305-1|page= 210}}</ref> | |||

| The Crimean Khanate, a ], succeeded the Golden Horde and lasted from 1449 to 1779<ref>{{cite web|author=]|title=The Sultan's Raiders: The Military Role of the Crimean Tatars in the Ottoman Empire|url=http://www.jamestown.org/uploads/media/Crimean_Tatar_-_complete_report_01.pdf|publisher=]|format=PDF|year=2013|page=27|accessdate=30 March 2015}}</ref> In 1571, the ] attacked and sacked Moscow, burning everything but the Kremlin.<ref>"''''". John F. Richards (2006). ]. p.260. ISBN 0-520-24678-0</ref> Until the late 18th century, Crimean Tatars maintained a massive ] with the Ottoman Empire, exporting about 2 million slaves from Russia and Ukraine over the period 1500–1700.<ref>Darjusz Kołodziejczyk, as reported by {{cite web|author=Mikhail Kizilov|title=Slaves, Money Lenders, and Prisoner Guards: The Jews and the Trade in Slaves and Captives in the Crimean Khanate|url=http://www.academia.edu/3706285/Slaves_Money_Lenders_and_Prisoner_Guards_The_Jews_and_the_Trade_in_Slaves_and_Captives_in_the_Crimean_Khanate|work=The Journal of Jewish Studies|year=2007|page=2|accessdate=30 March 2015}}</ref> | |||

| === |

===Mongol Conquest (1238–1449)=== | ||

| The north and centre of Crimea fell to the ] ], although the south coast was still controlled by the Christian ] and ]. The ] were fought between the 13th and 15th centuries for control of south Crimea.<ref>Slater, Eric. "Caffa: Early Western Expansion in the Late Medieval World, 1261–1475." ''Review (Fernand Braudel Center)'' 29, no. 3 (2006): 271–83. {{JSTOR|40241665}}. pp. 271</ref> | |||

| In 1774, the Khanate was proclaimed independent under the ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.fas.nus.edu.sg/hist/eia/documents_archive/kucuk-kaynarca.php|title=Treaty of Peace (Küçük Kaynarca), 1774|work=nus.edu.sg|date=20 November 2014|accessdate=29 March 2015}}</ref> and was then ] in 1783.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.runivers.ru/bookreader/book9829/#page/891/mode/1up|script-title=ru:Полное собрание законов Российской Империи. Собрание Первое. Том XXI. 1781 – 1783 гг.|trans-title=Complete Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire. The first meeting. Volume XXI. 1781–1783.|language=ru|website=Runivers|accessdate=30 March 2015}}</ref><ref name="GP223">{{cite journal|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/4205010?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents|title=The Great Powers and the Russian Annexation of the Crimea, 1783-4|author=M. S. Anderson|journal=The Slavonic and East European Review|year=1958|month=December|volume=37|issue=88|pages=17–41}}</ref> | |||

| ===Crimean Khanate (1443–1783)=== | |||

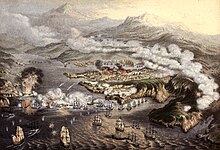

| From 1853 to 1856, the peninsula was the site of the principal engagements of the ], a conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of ], ], the Ottoman Empire and ].<ref>{{cite journal|title=Crimean War (1853-1856)|journal=Gale Encyclopedia of World History: War|date=2008|volume=2|url=http://www.omnilogos.com/2015/01/crimean-war-1853-1856.html}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Crimean Khanate}} | |||

| In the 1440s the ] formed out of the collapse of the horde<ref>{{cite web|author=]|title=The Sultan's Raiders: The Military Role of the Crimean Tatars in the Ottoman Empire|url=http://www.jamestown.org/uploads/media/Crimean_Tatar_-_complete_report_01.pdf|publisher=]|year=2013|page=27|access-date=30 March 2015|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131021092115/http://www.jamestown.org/uploads/media/Crimean_Tatar_-_complete_report_01.pdf|archive-date=21 October 2013}}</ref> but quite rapidly itself became subject to the ], which also conquered the coastal areas which had kept independent of the Khanate. A major source of prosperity in these times were ]. | |||

| ===Russian Empire (1783–1917)=== | |||

| During the ], Crimea was controlled by the ]. After they were defeated by the ], Crimea became part of the ] in 1921 as the ] (which became part of the Soviet Union in 1922). In the ] the peninsula was occupied by ] from July 1942 – May 1944. In 1944, when Crimea was liberated, it was downgraded to the Crimean Oblast and the ] were deported for alleged collaboration with the ] forces. A total of more than 230,000 people were deported, mostly to ], at the time about a fifth of the total population of the Crimean Peninsula. | |||

| {{see also|Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Empire|Novorossiya|Taurida Governorate}} | |||

| ] during the ]]] | |||

| In 1774, the Ottoman Empire was ] by ] with the ] making the Tatars of the Crimea politically independent. Catherine the Great's ] in 1783 into the Russian Empire increased Russia's power in the Black Sea area.<ref name="GP223">{{cite journal|jstor=4205010|title=The Great Powers and the Russian Annexation of the Crimea, 1783-4|author=M. S. Anderson|journal=The Slavonic and East European Review|date=December 1958|volume=37|issue=88|pages=17–41}} which would later see Russia's frontier expand westwards to the ].</ref> | |||

| ===Ukrainian control 1954–2014=== | |||

| ]'s city centre]] | |||

| {{see also|1954 transfer of Crimea|Crimean_sovereignty_referendum,_1991}} | |||

| In 1954, by an internal political action by Communist Party General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev, it became a territory of the ] within the ].<ref>"". '']''. March 10, 2014.</ref> | |||

| From 1853 to 1856, the strategic position of the peninsula in controlling the Black Sea meant that it was the site of the principal engagements of the ], where Russia lost to a French-led alliance.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Crimean War (1853–1856)|journal=Gale Encyclopedia of World History: War|year=2008|volume=2|url=http://www.omnilogos.com/2015/01/crimean-war-1853-1856.html|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150416183025/http://www.omnilogos.com/2015/01/crimean-war-1853-1856.html|archive-date=16 April 2015}}</ref> | |||

| In January 1991, ] in the Crimean Oblast, and voters approved restoring the ]. However, after the ] less than a year later, the ] was formed as a constituent entity of independent Ukraine,<ref>''The Strategic Use of Referendums: Power, Legitimacy, and Democracy'' By Mark Clarence Walke (page 107)</ref><ref name="szporluk">''National Identity and Ethnicity in Russia and the New States of Eurasia'' edited by Roman Szporluk (page 174)</ref> with a majority of Crimean voters approving Ukrainian independence in a December referendum.<ref name="doyle">''Secession as an International Phenomenon: From America's Civil War to Contemporary Separatist Movements'' edited by Don Harrison Doyle (page 284)</ref> On 5 May 1992, the Crimean legislature declared conditional independence,<ref name="backind">{{cite news|url=http://www.nytimes.com/1992/05/06/world/crimea-parliament-votes-to-back-independence-from-ukraine.html|agency=The New York Times|title=Crimea Parliament Votes to Back Independence From Ukraine|first=Serge|last=Schmemann|date=6 May 1992|accessdate=27 March 2015}}</ref> but a referendum to confirm the decision was never held amid opposition from ].<ref name="szporluk"/><ref name="5 May 1992 in Crimea">{{cite book|author=Paul Kolstoe|coauthors=Andrei Edemsky|title=Russians in the Former Soviet Republics|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=i1C2MHgujb4C&pg=PA194|accessdate=1 April 2015|date=January 1995|publisher=C. Hurst & Co. Publishers|isbn=978-1-85065-206-9|page=194|chapter=The Eye of the Whirlwind: Belarus and Ukraine}}</ref> The ] voted to grant Crimea "extensive home rule" during the dispute.<ref name="doyle"/><ref name="backind"/> | |||

| === |

=== Russian Civil War (1917–1921) === | ||

| {{main| |

{{main|Crimea during the Russian Civil War}} | ||

| During the ], Crimea ] and was where ]'s anti-Bolshevik ] made their last stand. Many anti-Communist fighters and civilians escaped to ] but up to 150,000 were killed in Crimea. | |||

| {{see also|2014 Ukrainian revolution|Crimean status referendum, 2014}} | |||

| As a result of the ] and subsequent ], the sovereignty over the peninsula is ] between Ukraine and the ]. | |||

| ===Soviet Union (1921–1991)=== | |||

| Immediately after the flight of former Ukrainian President ] from Kiev on 21 February 2014, planning began in the ] to take control of Crimea.<ref>, retrieved 3/8/2015</ref> Within days, unmarked Russian forces took over the ] and Sevastopol, also occupying several localities in ] on the ], which is geographically a part of Crimea. Following a controversial referendum that purported to show majority support for joining Russia, Russian President ] signed a treaty of accession with the self-declared independent Republic of Crimea, absorbing it into the ], though the annexation was not recognised by Ukraine or most of the international community.<ref name="theguardian.com"/> The ] adopted a non-binding ] calling upon states not to recognise changes to the integrity of Ukraine.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.un.org/press/en/2014/ga11493.doc.htm |title=General Assembly Adopts Resolution Calling upon States Not to Recognize Changes in Status of Crimea Region |publisher=Un.org |date=27 March 2014 |accessdate=29 March 2015}}</ref> Russia withdrew its forces from southern Kherson in December 2014<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ukrinform.ua/rus/news/rossiya_ubrala_voyska_s_arabatskoy_strelki|publisher=Ukrinform|script-title=ru:Россия убрала войска с Арабатской стрелки|trans-title=Russian troops removed from the Arabat Spit|language=ru|date=9 December 2014|accessdate=30 March 2015}}</ref> The peninsula is now de facto controlled by Russia, which administers it as two ]: the Republic of Crimea and the ] of Sevastopol. Ukraine now effectively only controls the northern areas of the Arabat Spit and ] Sea.<ref>{{cite web|author=Oksana Grytsenko|url=http://www.kyivpost.com/content/ukraine/russian-troops-firmly-in-control-of-ukraines-gas-extraction-station-in-kherson-oblasts-arabat-spit-341084.html|publisher=Kyiv Post|title=Russian troops firmly in control of Ukraine's gas extraction station in Kherson Oblast's Arabat Spit|date=27 March 2014|accessdate=30 March 2015}}</ref> | |||

| {{see also|Crimea in the Soviet Union|Transfer of Crimea in the Soviet Union}} | |||

| ]" at the ] in Crimea: ], ], and ]]] | |||

| In 1921 the ] was created as part of the ].<ref name="blacksea-crimea/hist">{{Cite web | url= http://www.blacksea-crimea.com/history1.html | title= History | access-date= 28 March 2007 | work= blacksea-crimea.com | archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20070404102214/http://www.blacksea-crimea.com/history1.html | archive-date= 4 April 2007 | url-status= usurped }}</ref> It was ] from 1942 to 1944 during the ]. After the Soviets regained control in 1944, they ] and several other nationalities to elsewhere in the USSR. The autonomous republic was dissolved in 1945, and Crimea became ] of the Russian SFSR. ] to the ] in 1954, on the 300th anniversary of the ]. | |||

| ===Ukraine (since 1991)=== | |||

| {{main|History of Crimea (1991–2014)}} | |||

| With the ] and Ukrainian independence in 1991 most of the peninsula was reorganized as the ].<ref>''The Strategic Use of Referendums: Power, Legitimacy, and Democracy'' By Mark Clarence Walke (page 107)</ref><ref name="szporluk">''National Identity and Ethnicity in Russia and the New States of Eurasia'' edited by Roman Szporluk (page 174)</ref><ref name="5 May 1992 in Crimea">{{cite book|author=Paul Kolstoe|author2=Andrei Edemsky|title=Russians in the Former Soviet Republics|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=i1C2MHgujb4C&pg=PA194|date=January 1995|publisher=C. Hurst & Co. Publishers|isbn=978-1-85065-206-9|page=194|chapter=The Eye of the Whirlwind: Belarus and Ukraine}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |editor1-last=Doyle |editor1-first=Don H. |title=Secession as an International Phenomenon: From America's Civil War to Contemporary Separatist Movements |date=2010 |publisher=University of Georgia Press |isbn=9780820337371 |page=285}}</ref> A ] partitioned the ], allowing Russia to continue basing its fleet in Sevastopol, with the ] in 2010. | |||

| ====Russian occupation (from 2014)==== | |||

| {{main|Russian occupation of Crimea|Republic of Crimea (Russia)}} | |||

| {{further|Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation|Crimea attacks (2022–present)}} | |||

| ]") outside the occupied ]]] | |||

| In 2014, Crimea saw demonstrations against the removal of the Russia-leaning ] ] ] and protests in support of ].<ref name="EN25214">{{cite news|url=http://www.euronews.com/2014/02/25/ukraine-leader-turchynov-warns-of-danger-of-separatism/|title=Ukraine leader Turchynov warns of 'danger of separatism'|publisher=]|date=25 February 2014|access-date=10 March 2015|archive-date=4 March 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304073813/http://www.euronews.com/2014/02/25/ukraine-leader-turchynov-warns-of-danger-of-separatism/}}</ref><ref name=guardian226>{{cite news|title=Russia puts military on high alert as Crimea protests leave one man dead |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/feb/26/ukraine-new-leader-disbands-riot-police-crimea-separatism|work=The Guardian|date=26 February 2014|access-date=27 February 2014}}</ref> Ukrainian historian Volodymyr Holovko estimates 26 February protest in support of the integrity of Ukraine in Simferopol at 12,000 people, opposed by several thousand pro-Russian protesters.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Головко |first=Володимир |date=2021 |title=ЗАХОПЛЕННЯ БУДІВЛІ ВЕРХОВНОЇ РАДИ АВТОНОМНОЇ РЕСПУБЛІКИ КРИМ 2014 |url=http://resource.history.org.ua/cgi-bin/eiu/history.exe?Z21ID=&I21DBN=EIU&P21DBN=EIU&S21STN=1&S21REF=10&S21FMT=eiu_all&C21COM=S&S21CNR=20&S21P01=0&S21P02=0&S21P03=TRN=&S21COLORTERMS=0&S21STR=zakhoplennja_budivli_verkhovnoji_rady_avtonomnoji_respubliky_krym_2014 |website=Енциклопедія історії України}}</ref> On 27 February, Russian forces occupied parliament and government buildings<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fedorchak |first=Viktoriya |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EWjwEAAAQBAJ&dq=parliamentary+building+in+Simferopol+and+other+main+governmental&pg=PT58 |title=The Russia-Ukraine War: Towards Resilient Fighting Power |date=2024-03-19 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-1-040-00731-0 |pages=44–45 |language=en}}</ref> and other strategic points in Crimea<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/28/world/europe/crimea-ukraine.html?_r=0|title=Gunmen Seize Government Buildings in Crimea|author=Andrew Higgins|author2=Steven Erlanger|work=The New York Times|date=27 February 2014|access-date=25 June 2022}}</ref> and the Russian-organized ] from Ukraine following an illegal and internationally unrecognized ].<ref>Marxsen, Christian (2014). . Max-Planck-Institut. Retrieved 25 June 2022.</ref> Russia then annexed Crimea, although most countries (100 votes in favour, 11 against, 58 abstentions) continued to recognize Crimea as part of Ukraine.<ref name=":0">{{cite news| title=General Assembly Adopts Resolution Calling upon States Not to Recognize Changes in Status of Crimea Region | website=UN Press | date=27 March 2014 | url=https://press.un.org/en/2014/ga11493.doc.htm}}</ref><ref name="UNGA">{{Cite web |date=1 April 2014 |title=Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 27 March 2014 |url=https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n13/455/17/pdf/n1345517.pdf?token=QCsLVasx7bgFzsMcTD&fe=true |access-date=2024-06-27 |publisher=] |language=en }}</ref><ref name="INTLCOM">{{Cite web |date=23 August 2021 |title=Ukraine's president pledges to 'return' Russia-annexed Crimea |url=https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/8/23/ukraines-president-pledges-to-return-russia-annexed-crimea |access-date=2024-06-27 |website=] |language=en}}</ref><ref name="UKRMFA">{{Cite web |date=22 July 2022 |title=Temporary Occupation of Crimea and City of Sevastopol |url=https://mfa.gov.ua/en/temporary-occupation-autonous-republic-crimea-and-city-sevastopol |access-date=8 July 2024 |website=] |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ==Geography== | ==Geography== | ||

| {{Location map+|Crimea|relief=1|width=350|places= | |||

| {{further|East European Plain}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|coordinates={{coord|44|23|14|N|33|44|17|E}}|label=]}} | |||

| Covering an area of {{convert|27000|km2|sqmi|0|abbr=on|0}}, Crimea is located on the northern coast of the Black Sea and on the western coast of the ], the only land border is shared with Ukraine's ] from the north. | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|coordinates={{coord|44|57|7|N|34|6|8|E}}|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|coordinates={{coord|44|36|N|33|32|E}}|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|coordinates={{coord|45|21|43|N|36|28|16|E}}|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|coordinates={{coord|46|08|58|N|33|40|20|E}}|label=]|position=left}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|coordinates={{Coord|45|22|58|N|36|38|43|E}}|label=]|position=top}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|coordinates={{coord|45.40|32.48}}|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|coordinates={{coord|45|48|N|32|37|E}}|label='']''|mark=Blue pog.svg}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|coordinates={{coord|46|05|N|34|20|E}}|label='']''|mark=Blue pog.svg}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|coordinates={{coord|45|03|N|33|28|E}}|label='']''|position=left|mark=Blue pog.svg}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|coordinates={{coord|44.5|36.25}}|label='']''|mark=Blue pog.svg|position=bottom}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|coordinates={{coord|46|36.25}}|label={{nowrap|'']''}}|mark=Blue pog.svg|position=top}} | |||

| |caption = Geography of Crimea | |||

| }} | |||

| {{further|East European Plain|Black Sea Lowland}} | |||

| Covering an area of {{convert|27000|km2|sqmi|0|abbr=on}}, Crimea is located on the northern coast of the Black Sea and on the western coast of the ]; the only land border is shared with Ukraine's ] on the north. Crimea is almost an island and only connected to the continent by the ], a strip of land about {{convert|5|–|7|km|mi|1}} wide. | |||

| Much of the natural border between the Crimean Peninsula and the Ukrainian mainland comprises the ] or "Rotten Sea", a large system of shallow lagoons stretching along the western shore of the Sea of Azov. Besides the isthmus of Perekop, the peninsula is connected to the Kherson Oblast's ] by bridges over the narrow ] and ] straits and over Kerch Strait to the ]. The northern part of ] is administratively part of Henichesk Raion in Kherson Oblast, including its two rural communities of ] and ]. The eastern tip of the Crimean peninsula comprises the ], separated from ] on the Russian mainland by the ], which connects the Black Sea with the Sea of Azov, at a width of between {{convert|3|–|13|km|mi|1}}. | |||

| Geographers generally divide the peninsula into three zones: the ], the ], and the ]. | |||

| === |

===Places=== | ||

| {{Location map+ | Crimea | |||

| {{further|Black Sea|Sea of Azov}} | |||

| | AlternativeMap = |Relief map of Crimea (disputed status).jpg|relief=1|float=right|width=350 | |||

| ] | |||

| | caption =Places in Crimea | |||

| The Crimean peninsula comprises many smaller peninsulas, such as the mentioned ], ], ] and many others. Crimea also possesses lots of headlands such as ], ], ], ], ], ], and many others. | |||

| | places = | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=46.17|long=33.69|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=45.50|long=32.70|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=45.33|long=33.00|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=45.19|long=33.37|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=44.60|long=33.53|label=]|position=left}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=44.50|long=33.60|label=]|position=left}} | |||

| The Crimean coastline is broken by several bays and harbors. These harbors lie west of the ] by the Bay of Karkinit; on the southwest by the open Bay of Kalamita between the port cities of ] and Sevastopol. | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=44.39|long=33.79|label=]|position=bottom}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=44.42|long=34.04|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=44.50|long=34.17|label=]|position=left}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=44.55|long=34.29|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=44.67|long=34.40|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=44.85|long=34.97|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=45.05|long=35.38|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=45.36|long=36.47|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=44.59|long=33.81|label=]}} | |||

| The ] is attached to the Crimean mainland by Isthmus of Yenikale, delimited by the ] to the north (interrputed by the incoming ]), and the Bay of Caffa{{Citation needed|date=December 2012}} to the south (arching eastward from the port of ]). | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=44.75|long=33.86|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=44.95|long=34.10|label=]}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=45.05|long=34.60|label=]|position=top}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=45.03|long=35.09|label=]|position=top}} | |||

| {{Location map~|Crimea|lat=45.71|long=34.39|label=]|position=bottom}} | |||

| }} | |||

| Given its long history and many conquerors, most towns in Crimea have several names. | |||

| '''West:''' The ]/]/], about {{convert|7|km|mi|abbr=on|sigfig=1}} wide, connects Crimea to the mainland. It was often fortified and sometimes garrisoned by the Turks. The ] now crosses it to bring water from the Dnieper. To the west ] separates the ] from the mainland. On the north side of the peninsula is ]/Kalos ]. On the south side is the large ] Bay and the port and ancient Greek settlement of ]/Kerkinitis/Gözleve. The coast then runs south to ]/], a good natural harbor, great naval base and the largest city on the peninsula. At the head of ] stands ]/Kalamita. South of Sevastopol is the small ]. | |||

| ] and ]]] | |||

| '''South:''' In the south, between the ] and the sea runs a narrow coastal strip which was ] and (after 1475) by the Turks. Under Russian rule it became a kind of ]. In Soviet times the many palaces were replaced with ]s and health resorts. From west to east are: ]; ]/Symbalon/Cembalo, a smaller natural harbor south of Sevastopol; ], the southernmost point; ] with the ]; ]; ]; ]; ]. Further east is ]/Sougdia/Soldaia with its Genoese fort. Further east still is Theodosia/Kaffa/], once a great ] and a kind of capital for the Genoese and Turks. Unlike the other southern ports, Feodosia has no mountains to its north. At the east end of the {{convert|90|km|mi|abbr=on|sigfig=2}} ] is ]/], once the capital of the ]. Just south of Kerch the new Crimean Bridge (opened in 2018) connects Crimea to the ]. | |||

| '''Sea of Azov:''' There is little on the south shore. The west shore is marked by the ]. Behind it is the ] or "Putrid Sea", a system of lakes and marshes which in the far north extend west to the Perekop Isthmus. Road- and rail-bridges cross the northern part of Syvash. | |||

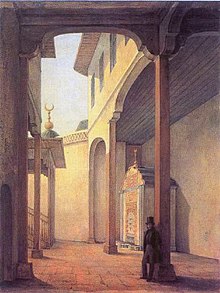

| '''Interior:''' Most of the former capitals of Crimea stood on the north side of the mountains. ]/Doros (Gothic, Theodoro). ] (1532–1783). | |||

| Southeast of Bakhchysarai is the cliff-fort of ]/Qirq Or which was used in more warlike times. ]/Ak-Mechet, the modern capital. ]/Bilohorsk was a commercial center. Solkhat/] was the old Tatar capital. Towns on the northern steppe area are all modern, notably ], a major road- and rail-junction. | |||

| '''Rivers:''' The longest is the ], which rises southeast of Simferopol and flows north and northeast to the Sea of Azov. The ] flows west to reach the Black Sea between Yevpatoria and Sevastopol. The shorter ] flows west to Sevastopol Bay. | |||

| '''Nearby:''' East of the Kerch Strait the Ancient Greeks founded colonies at ] (at the head of ]), ] (later Tmutarakan and ]), ] (later a Turkish port and now Anapa). At the northeast point of the Sea of Azov at the mouth of the Don River were ], Azak/] and now ]. North of the peninsula the Dnieper turns westward and enters the Black Sea through the east–west ] which also receives the Bug River. At the mouth of the Bug stood ]. At the mouth of the estuary is ]. ] stands where the coast turns southwest. Further southwest is ]/Akkerman/]. | |||

| ===Crimean Mountains=== | ===Crimean Mountains=== | ||

| {{main|Crimean Mountains}} | {{main|Crimean Mountains}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The southeast coast is flanked at a distance of {{convert|8|–|12|km|mi|1}} from the sea by a parallel range of mountains |

The southeast coast is flanked at a distance of {{convert|8|–|12|km|mi|1}} from the sea by a parallel range of mountains: the Crimean Mountains.<ref>The ] may also be referred to as the Yaylâ Dağ or Alpine Meadow Mountains.</ref> These mountains are backed by ]. | ||

| The main range of these mountains |

The main range of these mountains rises with extraordinary abruptness from the deep floor of the Black Sea to an altitude of {{convert|600|–|1545|m|ft|0}}, beginning at the southwest point of the peninsula, called ]. Some Greek myths state that this cape was supposedly crowned with the temple of ] where ] officiated as priestess.<ref name="EB1911">{{Cite EB1911|wstitle= Crimea |volume= 07 |last1= Kropotkin |first1= Peter Alexeivitch|author1-link=Peter Kropotkin|last2= Bealby |first2= John Thomas | pages = 449–450; see line one |quote=...ancient Tauris or Tauric Chersonese, called by the Russians by the Tatar name Krym or Crim}}</ref> | ||

| ] |

], on the south slope of the mountains, is the highest waterfall in Crimea.<ref>{{cite news|url= http://extremetime.ru/en/tours/krim_3kaniona.aspx|publisher= extremetime.ru |title= Three canyons trekking (Chernorechensky Canyon, Uzunja Canyon and Grand Crimean Canyon). Journey by a mountainous part of Crimea.| access-date= 1 May 2016}}</ref> | ||

| ===Hydrography=== | |||

| {{redirect-distinguish|Crimea river|Cry Me a River (disambiguation){{!}}Cry Me a River}} | |||

| There are 257 rivers and major streams on the Crimean peninsula; they are primarily fed by rainwater, with snowmelt playing a very minor role. This makes for significant seasonal fluctuation in water flow, with many streams drying up completely during the summer.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Jaoshvili |first=Shalva |year= 2002 |title= The rivers of the Black Sea |location= Copenhagen |publisher= European Environment Agency |page= 15 |oclc= 891861999 |url= http://edz.bib.uni-mannheim.de/daten/edz-bn/eua/02/C__DOKUME~1_ZEFZEI_LOKALE~1_TEMP_plugtmp_tech71_en.pdf |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20160310073738/http://edz.bib.uni-mannheim.de/daten/edz-bn/eua/02/C__DOKUME~1_ZEFZEI_LOKALE~1_TEMP_plugtmp_tech71_en.pdf |archive-date= 10 March 2016 |url-status= live}}</ref> The largest rivers are the ] (Salğır, Салгир), the Kacha (Кача), the ] (Альма), and the Belbek (Бельбек). Also important are the Kokozka (Kökköz or Коккозка), the Indole (Indol or Индо́л), the ] (Çorğun, Chernaya or Чёрная), the Derekoika (Dereköy or Дерекойка),<ref>{{Cite web|title= Дерекойка, река |trans-title= Derekoika river |work= Путеводитель по отдыху в Ялте |url= http://jalita.com/big_yalta/yalta/derekoika.shtml}}</ref> the Karasu-Bashi (Biyuk-Karasu or Биюк-Карасу) (a tributary of the Salhyr river), the Burulcha (Бурульча) (also a tributary of the Salhyr), the ], and the Ulu-Uzen'. The longest river of Crimea is the Salhyr at {{convert|204|km|mi|abbr=on|sigfig=3}}. The Belbek has the greatest average discharge at {{convert|2.16|m3/s|ft3/s}}.<ref>{{harvnb|Jaoshvili|2002|page= 34}}</ref> The Alma and the Kacha are the second- and third-longest rivers.<ref name="BSE">{{Cite encyclopedia|title= Alma, Kacha River |year= 2014 |editor= Grinevetsky, Sergei R. |encyclopedia= The Black Sea Encyclopedia|location= Berlin |publisher= Springer |page= and |isbn= 978-3-642-55226-7|display-editors= etal}}</ref> | |||

| ], which provided 85% of Crimea's drinking and agriculture water.<ref name = canal>{{cite news |title=Dam leaves Crimea population in chronic water shortage |url=https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2017/1/4/dam-leaves-crimea-population-in-chronic-water-shortage |work=Al-Jazeera |date=4 January 2017}}</ref>]] | |||

| There are more than fifty salt lakes and ] on the peninsula. The largest of them is Lake Sasyk (Сасык) on the southwest coast; others include ], Koyashskoye, Kiyatskoe, Kirleutskoe, Kizil-Yar, Bakalskoe, and ].<ref>{{Cite journal|author= Mirzoyeva, Natalya |year= 2015 |title= Radionuclides and mercury in the salt lakes of the Crimea |journal= Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology |volume= 33 |issue= 6 |pages= 1413–1425 |doi= 10.1007/s00343-015-4374-5|bibcode= 2015ChJOL..33.1413M |s2cid= 131703200 |display-authors= etal|issn = 0254-4059}}</ref> The general trend is for the former lakes to become salt pans.<ref>{{Cite book|author= Kayukova, Elena |title= Thermal and Mineral Waters |year= 2014 |chapter= Resources of Curative Mud of the Crimea Peninsula |editor1= Balderer, Werner |editor2= Porowski, Adam |editor3= Idris, Hussein |editor4= LaMoreaux, James W. |pages= 61–72 |location= Berlin |publisher= Springer |isbn= 978-3-642-28823-4 |doi= 10.1007/978-3-642-28824-1_6}}</ref> ] (Sıvaş or Сива́ш) is a system of interconnected shallow ]s on the north-eastern coast, covering an area of around {{convert|2560|km2|sqmi|abbr=on|sigfig=3}}. A number of dams have created reservoirs; among the largest are the Simferopolskoye, Alminskoye,<ref>{{Cite web |author1= Bogutskaya, Nina |author2= Hales, Jennifer |title= 426: Crimea Peninsula |work= Freshwater Ecoregions of the World |publisher= The Nature Conservancy |url= http://www.feow.org/ecoregions/details/crimea_peninsula |access-date= 10 March 2016 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20170116162528/http://www.feow.org/ecoregions/details/Crimea_Peninsula |archive-date= 16 January 2017 |url-status= dead }}</ref> the Taygansky and the Belogorsky just south of ] in ].<ref>{{Cite news |title= In Crimea has receded one of the largest reservoirs |date= 19 October 2015 |newspaper= News from Ukraine |url= http://en.reporter-ua.ru/in-crimea-has-receded-one-of-the-largest-reservoirs.html |access-date= 10 March 2016 |archive-date= 23 May 2016 |archive-url= http://arquivo.pt/wayback/20160523160806/http://en.reporter-ua.ru/in-crimea-has-receded-one-of-the-largest-reservoirs.html |url-status= dead }}</ref> The ], which transports water from the ], is the largest of the man-made irrigation channels on the peninsula.<ref name=construction>Tymchenko, Z. ''''. (Russian) ]. 13 May 2014 (Krymskiye izvestiya. November 2012)</ref> Crimea was facing an unprecedented ] crisis following the blocking of the canal by Ukraine in 2014.<ref>{{cite news |title=Pray For Rain: Crimea's Dry-Up A Headache For Moscow, Dilemma For Kyiv |url=https://www.rferl.org/a/pray-for-rain-crimea-s-dry-up-a-headache-for-moscow-dilemma-for-kyiv/30515986.html |work=Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty |date=29 March 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Crimea Drills For Water As Crisis Deepens In Parched Peninsula |url=https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine--crimea-water-shortage-drought/30903039.html |work=Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty |date=25 October 2020}}</ref><ref name = canal/> After the 2022 Russian invasion, the flow of water was restored however the ] could lead to problems with water supply again. | |||

| ===Steppe=== | ===Steppe=== | ||

| {{main| |

{{main|Pontic–Caspian steppe}} | ||

| Seventy-five percent of the remaining area of Crimea consists of semiarid ] lands, a southward continuation of the |

Seventy-five percent of the remaining area of Crimea consists of semiarid ] lands, a southward continuation of the Pontic–Caspian steppe, which slope gently to the northwest from the foothills of the Crimean Mountains. Numerous ]s, or ]s, of the ancient ]ns are scattered across the Crimean steppes. | ||

| Numerous ]s, or ]s, of the ancient ]ns are scattered across the Crimean steppes. | |||

| === |

===Southern Coast=== | ||

| {{main|Southern Coast (Crimea)}} | |||

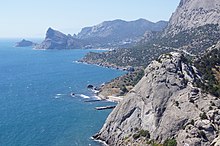

| ] in the background and ] as seen from the ].]] | ] in the background and ] as seen from the ].]] | ||

| The terrain that lies |

The terrain that lies south of the sheltering Crimean Mountain range is of an altogether different character. Here, the narrow strip of coast and the slopes of the mountains are covered with greenery. This "riviera" stretches along the southeast coast from capes ] and ], in the south, to Feodosia. There are many summer sea-bathing resorts such as ], ], ], ], ], and ]. During the years of Soviet rule, the resorts and ]s of this coast were used by leading politicians<ref>{{Cite news |last1=Salem |first1=Harriet |last2=Makarova |first2=Ludmila |date=2014-03-28 |title=Crimean annexation brings dacha prize closer for Putin |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/28/crimean-annexation-dacha-vladimir-putin-russian-president |access-date=2024-07-24 |work=The Guardian |language=en-GB |issn=0261-3077}}</ref> and served as prime perquisites of the politically loyal.{{Citation needed|reason=''Politically loyal'', like whom? ''Served as prime perquisites'', according to whom?|date=December 2012}} In addition, vineyards and fruit orchards are located in the region. Fishing, mining, and the production of ]s are also important. Numerous Crimean Tatar villages, mosques, ], and palaces of the Russian imperial family and nobles are found here, as well as picturesque ancient Greek and medieval castles. | ||

| The Crimean Mountains and the southern coast are part of the ] ecoregion. The natural vegetation consists of scrublands, woodlands, and forests, with a climate and vegetation similar to the ]. | The Crimean Mountains and the southern coast are part of the ] ecoregion. The natural vegetation consists of scrublands, woodlands, and forests, with a climate and vegetation similar to the ]. | ||

| ===Climate=== | ===Climate=== | ||

| ] | |||

| Most of Crimea has a temperate continental climate, except for the south coast where it experiences a humid subtropical climate{{Citation needed|date=December 2012}}, due to warm influences from the Black Sea and the high ground of the Crimean Mountains. Summers can be hot ({{convert|28|°C|°F|1|disp=or}} July average) and winters are cool ({{convert|-0.3|°C|°F|1|disp=or}} January average) in the interior, on the south coast winters are milder ({{convert|4|°C|°F|1|disp=or}} January average) and temperatures much below freezing are exceptional. On the high ground, freezing weather is common in winter. Precipitation throughout Crimea is low, averaging only {{convert|400|mm|in|1|abbr=on}} a year. The Crimean coast is shielded from the north winds by the mountains, and as a result usually has mild winters. Cool season temperatures average around {{convert|7|°C|°F|1}} and it is rare for the weather to drop below freezing except in the mountains, where there is usually snow.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.blacksea-crimea.com/climate.html |title=Climate in Crimea,Weather in Yalta:How Often Does it Rain in Crimea? |publisher=Blacksea-crimea.com |date= |accessdate=2014-04-10}}</ref> Because of its climate, the southern Crimean coast is a popular beach and sun resort for Ukrainian and Russian tourists. | |||

| Crimea is located between the ] and ] belts and is characterized by warm and sunny weather.<ref name=crimeaclimate>{{cite web|url= http://old.crimea-portal.gov.ua/index.php?&v=8&tek=28&par=8&f=us |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20100901153138/http://old.crimea-portal.gov.ua/index.php?&v=8&tek=28&par=8&f=us |archive-date= 1 September 2010 |title= Description of the Crimean Climate |publisher= Autonomous Republic of Crimea Information Portal |access-date= 1 October 2016 |url-status= dead }}</ref> It is characterized by diversity and the presence of microclimates.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> The northern parts of Crimea have a moderate ] with short but cold winters and moderately hot dry summers.<ref name=crimeageography>{{cite web|url= http://old.crimea-portal.gov.ua/index.php?&v=8&tek=27&par=8&art=3&date=&f=us |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20100903233704/http://old.crimea-portal.gov.ua/index.php?&v=8&tek=27&par=8&art=3&date=&f=us |archive-date= 3 September 2010 |title= Geographical Survey of the Crimean region |publisher= Autonomous Republic of Crimea Information Portal |access-date= 1 October 2016 |url-status= dead }}</ref> In the central and mountainous areas the climate is transitional between the continental climate to the north and the ] to the south.<ref name=crimeageography/> Winters are mild at lower altitudes (in the foothills) and colder at higher altitudes.<ref name=crimeageography/> Summers are hot at lower altitudes and warm in the mountains.<ref name=crimeageography/> A subtropical, Mediterranean climate dominates the southern coastal regions, is characterized by mild winters and moderately hot, dry summers.<ref name=crimeageography/> | |||

| The climate of Crimea is influenced by its geographic location, relief, and influences from the ].<ref name=crimeaclimate/> The Southern Coast is shielded from cold air masses coming from the north and, as a result, has milder winters.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> Maritime influences from the Black Sea are restricted to coastal areas; in the interior of the peninsula the maritime influence is weak and does not play an important role.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> Because a high-pressure system is located north of Crimea in both summer and winter, winds predominantly come from the north and northeast year-round.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> In winter these winds bring in cold, dry continental air, while in summer they bring in dry and hot weather.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> Winds from the northwest bring warm and wet air from the Atlantic Ocean, causing precipitation during spring and summer.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> As well, winds from the southwest bring very warm and wet air from the subtropical latitudes of the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean sea and cause precipitation during fall and winter.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> | |||

| ===Strategic value=== | |||

| {{further|Black Sea Fleet}} | |||

| ] (shown in purple) connecting ] with ] via ]. The major centers of the ], ] itself, ] and ], arose along this route.]] | |||

| The Black Sea ports of Crimea provide quick access to the ], ] and Middle East. ], possession of the southern coast of Crimea was sought after by most empires of the greater region since antiquity (], ], ], ], ], ], ]).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/ukraine/10671066/What-is-the-Crimea-and-why-does-it-matter.html |title=What is the Crimea, and why does it matter? |publisher=Telegraph.co.uk |date=2014-03-02 |accessdate=2014-04-10}}</ref> | |||

| Mean annual temperatures range from {{convert|10|°C|°F|1}} in the far north (]) to {{convert|13|°C|°F|1}} in the far south (]).<ref name=crimeaclimate/> In the mountains, the mean annual temperature is around {{convert|5.7|°C|°F|1}}.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> For every {{convert|100|m|ft|abbr= on}} increase in altitude, temperatures decrease by {{convert|0.65|C-change|2}} while precipitation increases.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> In January mean temperatures range from {{convert|-3|°C|°F|1}} in Armiansk to {{convert|4.4|°C|°F|1}} in ].<ref name=crimeaclimate/> Cool-season temperatures average around {{convert|7|°C|°F|1}} and it is rare for the weather to drop below freezing except in the mountains, where there is usually snow.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.blacksea-crimea.com/climate.html |title= Climate in Crimea, Weather in Yalta: How Often Does it Rain in Crimea? |publisher= Blacksea-crimea.com |access-date= 10 April 2014 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20100303193251/http://www.blacksea-crimea.com/climate.html |archive-date= 3 March 2010 |url-status= usurped }}</ref> In July mean temperatures range from {{convert|15.4|°C|°F|1}} in ] to {{convert|23.4|°C|°F|1}} in the central parts of Crimea to {{convert|24.4|°C|°F|1}} in Myskhor.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> The frost-free period ranges from 160 to 200 days in the steppe and mountain regions to 240–260 days on the south coast.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> | |||

| The ] is a major waterway and transportation route that crosses the European continent from north to south and ultimately links the Black Sea with the ], of strategic importance since the historical ]. The Black Sea serves as an economic thoroughfare connecting the ] region and the ] to central and Eastern Europe.<ref name="Crimea Annexation 'Robbery on International Scale'">{{cite news | url=http://www.cbn.com/cbnnews/world/2014/March/Russias-Deputy-PM-Scoffs-at-US-Sanctions/ | title=Crimea Annexation 'Robbery on International Scale' | work=CBN News | date=2014-03-19 | accessdate=19 March 2014 | agency=CBN News }}</ref> | |||

| Precipitation in Crimea varies significantly based on location; it ranges from {{convert|310|mm|in|1}} in ] to {{convert|1220|mm|in|1}} at the highest altitudes in the Crimean mountains.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> The Crimean mountains greatly influence the amount of precipitation present in the peninsula.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> However, most of Crimea (88.5%) receives {{convert|300|to|500|mm|in|1}} of precipitation per year.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> The plains usually receive {{convert|300|to|400|mm|in|1}} of precipitation per year, increasing to {{convert|560|mm|in|1}} in the southern coast at sea level.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> The western parts of the Crimean mountains receive more than {{convert|1000|mm|in|1}} of precipitation per year.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> Snowfall is common in the mountains during winter.<ref name=crimeageography/> | |||

| According to the ], in 2013 there were at least 12 operating merchant seaports in Crimea.<ref name="Черное море признано">{{cite news | url=http://www.blackseanews.net/read/64439 | title=Черное море признано одним из самых неблагоприятных мест для моряков | work=] | date=2013-05-27 | accessdate=20 September 2013 | agency=BlackSeaNews}}</ref> | |||

| Most of the peninsula receives more than 2,000 sunshine hours per year; it reaches up to 2,505 sunshine hours in ] in the Crimean Mountains.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> As a result, the climate favors recreation and tourism.<ref name=crimeaclimate/> Because of its climate and subsidized travel-packages from Russian state-run companies, the southern coast has remained a popular resort for Russian tourists.<ref>{{cite news|url= http://www.ibtimes.com/russia-ukraine-update-crimea-attracts-more-4-million-tourists-despite-annexation-2141287|work= International Business Times |title= Russia-Ukraine Update: Crimea Attracts More Than 4 Million Tourists Despite Annexation| date= 14 October 2015| access-date= 1 May 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Within 200 nautical miles of the Crimean shoreline there are an estimated 45 trillion cubic meters of gas reserves.<ref name="The Crimea Crisis -- Cui Bono?'">{{cite news | url=http://www.americanthinker.com/articles/2014/04/the_crimea_criss__cui_bono.html|title=The Crimea Crisis -- Cui Bono?| work=American Thinker|date=2014-04-01|accessdate=April 5, 2014|agency=American Thinker}}</ref> Hydrocarbons in the Black Sea shelf could yield as much as 1.5 billion cubic meters per year.<ref name="Heated issue: Russia to construct gas pipeline to Crimea'">{{cite news | url=http://rt.com/business/crimea-russia-gas-gazprom-533/| title= Heated issue: Russia to construct gas pipeline to Crimea | work=RT | date=2014-04-01 | accessdate=April 1, 2014 | agency=RT }}</ref> | |||

| ===Strategic value=== | |||

| {{further|Black Sea Fleet}} | |||

| ] (shown in purple) connecting ] with ] via ]. The major centers of ] – ] itself, ] and ] – arose along this route.]] The Black Sea ports of Crimea provide quick access to the ], ] and Middle East. ], possession of the southern coast of Crimea was sought after by most empires of the greater region since antiquity (], ], ], ], ], ], ]).<ref>{{cite web|url= https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/ukraine/10671066/What-is-the-Crimea-and-why-does-it-matter.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220110/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/ukraine/10671066/What-is-the-Crimea-and-why-does-it-matter.html |archive-date=10 January 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |title= What is the Crimea, and why does it matter? |work= The Daily Telegraph|date=2 April 2014|access-date=10 April 2014}}{{cbignore}}</ref> | |||

| The nearby ] is a major waterway and transportation route that crosses the European continent from north to south and ultimately links the Black Sea with the ], of strategic importance since the historical trade route ]. The Black Sea serves as an economic thoroughfare connecting the ] region and the ] to central and Eastern Europe.<ref name="Crimea Annexation 'Robbery on International Scale'">{{cite news | url= http://www.cbn.com/cbnnews/world/2014/March/Russias-Deputy-PM-Scoffs-at-US-Sanctions/ | title= Crimea Annexation 'Robbery on International Scale' | work= CBN News | date= 19 March 2014 | access-date= 19 March 2014 | agency= CBN News }}</ref> | |||

| According to the ], {{as of | 2013 | lc = on}} there were at least 12 operating merchant seaports in Crimea.<ref name="Черное море признано"> | |||

| {{cite news | |||

| | url= http://www.blackseanews.net/read/64439 | |||

| | title= Черное море признано одним из самых неблагоприятных мест для моряков | |||

| | trans-title = The Black Sea is recognized as one of the most unwelcoming places for sailors | |||

| | work= ] | date=27 May 2013 | |||

| | access-date= 20 September 2013 | agency= BlackSeaNews | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| ==Economy== | ==Economy== | ||

| {{see also|International sanctions during the Ukrainian crisis}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ]'s city centre]] | |||

| The main branches of the modern Crimean economy are tourism and agriculture.{{citation needed|date=December 2012}} Industrial plants are situated for the most part in the northern regions of the republic. Important industrial cities include ], housing a major railway connection, ] and ], among others. | |||

| In 2016 Crimea had Nominal GDP of ]7 billion and US$3,000 per capita.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://mrd.gks.ru/wps/wcm/connect/rosstat_ts/mrd/ru/statistics/grp/|title=Валовой региональный продукт::Мордовиястат|website=mrd.gks.ru|access-date=19 February 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180217021320/http://mrd.gks.ru/wps/wcm/connect/rosstat_ts/mrd/ru/statistics/grp/|archive-date=17 February 2018|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| The main branches of the modern Crimean economy are agriculture and fishing oysters pearls, industry and manufacturing, tourism, and ports. Industrial plants are situated for the most part in the southern coast (Yevpatoria, Sevastopol, Feodosia, Kerch) regions of the republic, few northern (Armiansk, Krasnoperekopsk, Dzhankoi), aside from the central area, mainly Simferopol okrug and eastern region in Nizhnegorsk (few plants, same for Dzhankoj) city. Important industrial cities include ], housing a major railway connection, ] and ], among others. | |||

| After the Russian annexation of Crimea in early 2014 and subsequent sanctions targeting Crimea, the tourist industry suffered major losses for two years. The flow of holidaymakers dropped 35 percent in the first half of 2014 over the same period of 2013.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.rferl.org/a/tourist-season-washout-in-annexed-crimea/25446604.html|title=Tourist Season A Washout in Annexed Crimea|newspaper=Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty|date=5 July 2014 |last1=Yurchenko |first1=Stas |last2=Dzhabbarov |first2=Usein |last3=Bigg |first3=Claire }}</ref> The number of tourist arrivals reached a record in 2012 at 6.1 million.<ref>{{cite news|script-title=ru:Итоги сезона-2013 в Крыму: туристов отпугнул сервис и аномальное похолодание |url=http://www.segodnya.ua/regions/krym/Itogi-sezona-2013-v-Krymu-turistov-otpugnul-servis-i-anomalnoe-poholodanie-.html |access-date=10 June 2017|work=Segodnya.ua|language=ru}}</ref> According to the Russian administration of Crimea, they dropped to 3.8 million in 2014,<ref>{{cite web|title=Справочная информация о количестве туристов, посетивших Республику Крым за 2014 год|url=http://mtur.rk.gov.ru/rus/file/statistika_turizma_za_2014_god.pdf|publisher=Министерство курортов и туризма Республики Крым|access-date=10 June 2017}}</ref> and rebounded to 5.6 million by 2016.<ref>{{cite web|title=Справочная информация о количестве туристов, посетивших республику крым за 2016 год|url=http://mtur.rk.gov.ru/file/spravochnaya_informatsiya_13012017.pdf|publisher=Министерство курортов и туризма Республики Крым|access-date=10 June 2017}}</ref> | |||

| The most important industries in Crimea include food production, chemical fields, mechanical engineering, and metalworking, and fuel production industries.<ref name = "CMU"/> Sixty percent of the industry market belongs to food production. There are a total of 291 large industrial enterprises and 1002 small business enterprises.<ref name = "CMU"/> | |||

| In 2014, the republic's annual GDP was $4.3 billion (500 times smaller than the size of Russia's economy). The average salary was $290 per month. The ] was $1.5 billion.<ref>{{cite news|title=Russia to cover Crimea's $1.5 billion budget deficit with state funds- TV |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/ukraine-crisis-crimea-deficit/russia-to-cover-crimeas-1-5-billion-budget-deficit-with-state-funds-tv-idUSL6N0MG4EF20140319 |access-date=17 July 2018 |work=Reuters |date=19 March 2014}}</ref> | |||

| The most important industries in Crimea include food production, chemical fields, mechanical engineering and metal working, and fuel production industries.<ref name = "CMU"/> Sixty percent of the industry market belongs to food production. There are a total of 291 large industrial enterprises and 1002 small business enterprises.<ref name = "CMU"/> | |||

| ===Agriculture=== | |||

| Agriculture in the region includes cereals, vegetable-growing, gardening, and ], particularly in the Yalta and ] regions. Livestock production includes cattle breeding, poultry keeping, and sheep breeding.<ref name="CMU">{{cite web|url=http://www.kmu.gov.ua/control/en/publish/printable_article?art_id=301361|archiveurl=http://wayback.archive.org/web/20070121174522/http://www.kmu.gov.ua/control/en/publish/printable_article?art_id=301361|archivedate=2007-01-21 |title=Autonomous Republic of Crimea – Information card |accessdate=February 22, 2007 |work=] }}</ref> Other products produced on the Crimean Peninsula include salt, ], ], and ] (found around ]) since ancient times.<ref>{{Cite book| title=] | author=Bealby, John T. | publisher=] | year=1911 | page= 449}}</ref> | |||

| Agriculture in the region includes cereals, vegetable-growing, gardening, and ], particularly in the Yalta and ] regions. Livestock production includes cattle breeding, poultry keeping, and sheep breeding.<ref name="CMU">{{cite web|url=http://www.kmu.gov.ua/control/en/publish/printable_article?art_id=301361|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070121174522/http://www.kmu.gov.ua/control/en/publish/printable_article?art_id=301361|archive-date=21 January 2007|title=Autonomous Republic of Crimea – Information card |access-date=22 February 2007 |work=] }}</ref> Other products produced on the Crimean Peninsula include salt, ], ], and ] (found around ]) since ancient times.<ref name="EB1911"/> | |||