| Revision as of 17:04, 28 April 2015 view sourceNorth Shoreman (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers46,519 edits oops -- didn't do what I said I was doing with the last edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:29, 6 January 2025 view source Citation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,437,486 edits Removed parameters. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Whoop whoop pull up | Category:Lynching victims in the United States | #UCB_Category 12/35 | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|American Jewish man (1884–1915) wrongfully convicted and lynched}} | |||

| {{For|the American college football player and coach|Leo J. Frank}} | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| {{pp-sock|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=July 2016}} | |||

| {{Use American English|date=July 2016}} | |||

| {{Infobox person | {{Infobox person | ||

| | name |

| name = Leo Frank | ||

| | image |

| image = File:Leo Frank.jpg | ||

| | |

| alt = Leo Frank in a portrait photograph | ||

| | |

| caption = Frank, {{circa|1910–1915}} | ||

| | |

| image_upright = 1.05 | ||

| | birth_name |

| birth_name = Leo Max Frank | ||

| | birth_date |

| birth_date = {{birth date|1884|4|17}} | ||

| | birth_place |

| birth_place = ], U.S. | ||

| | death_date |

| death_date = {{Death date and age|1915|8|17|1884|4|17}} | ||

| | death_place |

| death_place = ], U.S. | ||

| | death_cause |

| death_cause = ] | ||

| | resting_place |

| resting_place = New Mount Carmel Cemetery, ], ] | ||

| | resting_place_coordinates = {{coord|40.69269|-73.88115|display=inline |

| resting_place_coordinates = {{coord|40.69269|-73.88115|display=inline|name=Leo Frank's resting place}} | ||

| | education = Bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering (1906), pencil manufacturing apprenticeship (1908) | |||

| | monuments = ] monument 90th anniversary of founding, October 20, 2003, Mount Carmel Cemetery; Georgia historical marker, near lynching site, 1200 Roswell Street, Marietta, GA 30060 | |||

| | |

| alma_mater = ] | ||

| | |

| employer = National Pencil Company, Atlanta (1908–1915) | ||

| | criminal_charge = Convicted on August 25, 1913 for the murder of Mary Phagan | |||

| | religion = Judaism | |||

| | criminal_penalty = ] by hanging (1913); commuted to life imprisonment (1915) | |||

| | education = Bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering (1906), pencil manufacturing apprenticeship (1908) | |||

| | spouse = {{marriage|Lucille Selig|1910}} | |||

| | alma_mater = ] | |||

| | employer = National Pencil Company in Atlanta | |||

| | criminal_charge = Convicted on August 25, 1913, for the murder of Mary Phagan. | |||

| | criminal_penalty = Sentenced on August 26, 1913, to hang. Commuted to life in prison on June 21, 1915. | |||

| | spouse = Lucille Selig | |||

| | parents = Rudolph Frank and Rachel ("Rae") Jacobs | |||

| | relations = Marian J. Stern (sister), Moses Frank (uncle) | |||

| | signature = Leo Frank Signature.png | |||

| | signature_alt = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Antisemitism}} | |||

| '''Leo Max Frank''' (April 17, 1884 – August 17, 1915) was a Jewish-American factory superintendent whose widely publicized and controversial murder trial and conviction in 1913, appeals and extrajudicial ] in 1915 by a ] planned and led by prominent citizens in ], drew attention to questions of ]. Frank was posthumously pardoned in 1986, which the ] described as "an effort to heal old wounds," without officially absolving him of the crime. | |||

| '''Leo Max Frank''' (April 17, 1884{{spaced en dash}}August 17, 1915) was an American ] victim convicted in 1913 of the murder of 13-year-old Mary Phagan, an employee in a factory in ], Georgia where he was the superintendent. Frank's trial, conviction, and unsuccessful appeals attracted national attention. His kidnapping from prison and ] became the focus of social, regional, political, and racial concerns, particularly regarding ]. Modern researchers generally agree that Frank was wrongly convicted.{{refn|"The modern historical consensus, as exemplified in the Dinnerstein book, is that ... Leo Frank was an innocent man convicted at an unfair trial."<ref name="Wilkes Flagpole">{{cite magazine |last=Wilkes Jr. |first=Donald E. |author1-link=Donald E. Wilkes Jr. |magazine= ] |url=http://libguides.law.uga.edu/ld.php?content_id=6631399 |date=1 March 2000 |title=Politics, Prejudice, and Perjury |pages=9 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170117071544/http://libguides.law.uga.edu/ld.php?content_id=6631399 |archive-date=17 January 2017 }}</ref>|group=n}}<ref>{{Cite news |last=Ravitz |first=Jessica |date=November 2, 2009 |title=Murder case, Leo Frank lynching live on |url=http://www.cnn.com/2009/CRIME/11/02/leo.frank/index.html |access-date=2023-03-19 |work=] |language=en |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091103164330/http://www.cnn.com/2009/CRIME/11/02/leo.frank/index.html |archive-date=3 November 2009 |quote=The consensus of historians is that the Frank case was a miscarriage of justice. ... Frank's conviction was based largely on the testimony of a janitor, Jim Conley, who most came to see as Phagan's killer.}}</ref><ref name="MelnickUnamity" /> | |||

| An engineer and director of the National Pencil Company in ], Frank was convicted on August 25, 1913, for the murder of one of his factory employees, 13-year-old Mary Phagan. She had been strangled on April 26 and was found dead in the factory cellar the next morning. A state physician who conducted the autopsy reported evidence of sexual violence. Frank was the last person to admit having seen her alive, and there were allegations that he had sexually harassed her in the past. His criminal case became the focus of powerful class, regional, and political interests. Raised in New York, he was cast as a ] representative of ] capitalism, a ] northern Jew in contrast to the poverty experienced by child laborers like Phagan and many working-class adult Southerners of the time, as the agrarian South was undergoing the throes of industrialization. During trial proceedings, Frank and his lawyers resorted to racial stereotypes in their defense, accusing another suspect, James Conley – a Black factory worker and an admitted accomplice to the crime who had testified against Frank — of being especially disposed to lying and murdering because of his ethnicity. | |||

| Jim Conley is now believed by some historians to be the real murderer. <ref>For example: | |||

| *: "The best evidence now available indicates that the real murderer of Mary Phagan was Jim Conley, perhaps because she, encountering him after she left Frank's office, refused to give him her pay envelope, and he, in a drunken stupor, killed her to get it. | |||

| *Woodward 1963, p. 435: "The city police, publicly committed to the theory of Frank's guilt, and hounded by the demand for a conviction, resorted to the basest methods in collecting evidence. A Negro suspect , later implicated by evidence overwhelmingly more incriminating than any produced against Frank, was thrust aside by the cry for the blood of the 'Jew Pervert.'"</ref> | |||

| There was jubilation in the streets when Frank was convicted and sentenced to ] by way of ]. | |||

| Born to a ] family in ], Frank was raised in ] and earned a degree in mechanical engineering from ] in 1906 before moving to Atlanta in 1908. Marrying Lucille Selig (who became Lucille Frank) in 1910, he involved himself with the city's Jewish community and was elected president of the Atlanta chapter of the ], a Jewish fraternal organization, in 1912. At that time, there were growing concerns regarding child labor at factories. One of these children was Mary Phagan, who worked at the National Pencil Company where Frank was director. The girl was strangled on April 26, 1913, and found dead in the factory's cellar the next morning. Two notes, made to look as if she had written them, were found beside her body. Based on the mention of a "night witch", they implicated the night watchman, Newt Lee. Over the course of their investigations, the police arrested several men, including Lee, Frank, and Jim Conley, a janitor at the factory. | |||

| Newspaper coverage began with the report of the murder's discovery, and continued nearly unabated throughout the investigation, trial, and appeals process. Initially a local story, competition between Atlanta newspapers was fierce. This competition resulted in exceptional examples of ] and ]. After Frank's conviction, and during his legal appeals, interest in the case was championed by wealthy and influential individuals such as ], owner of ''The New York Times'', and others, who gave the story anti-Southern and pro-Frank ]. Resentment in Atlanta grew heated as the perception of northern interference in Georgia legal affairs intensified. One year after the trial, influential Georgian populist and former ] ] began fighting back in his own publications, ''The Jeffersonian'' and ''Watson's Magazine'', with ] on those who sought to overturn Frank's conviction. Watson attacked Frank as a sodomite and member of the Jewish aristocracy who had pursued "Our Little Girl" to a hideous death. | |||

| On May 24, 1913, Frank was indicted on a charge of murder and the case opened at ] Superior Court, on July 28. The prosecution relied heavily on the testimony of Conley, who described himself as an accomplice in the aftermath of the murder, and who the defense at the trial argued was, in fact, the perpetrator of the murder. A guilty verdict was announced on August 25. Frank and his lawyers made a series of unsuccessful appeals; their final appeal to the ] failed in April 1915. Considering arguments from both sides as well as evidence not available at trial, Governor ] commuted Frank's sentence from capital punishment to life imprisonment. | |||

| By April 1915, Frank's appeals to the Supreme Court of the United States had failed. Governor ] – law partner of Frank's lead trial defense attorney – stating that guilt had not been proven with absolute certainty, ] Frank's death sentence to life imprisonment, causing state-wide outrage. A crowd of 1,200 marched on Slaton's residence at the ''Governor's Mansion'' in protest. | |||

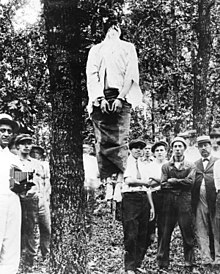

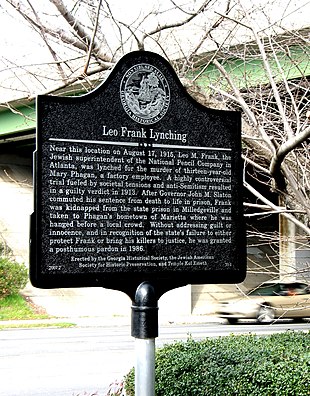

| The case attracted national press attention and many reporters deemed the conviction a travesty. Within Georgia, this outside criticism fueled antisemitism and hatred toward Frank. On August 16, 1915, he was kidnapped from prison by a group of armed men, and ] at ], Mary Phagan's hometown, the next morning. The new governor vowed to punish the lynchers, who included prominent Marietta citizens, but nobody was charged. In 1986, the ] issued a pardon in recognition of the state's failures—including to protect Frank and preserve his opportunity to appeal—but took no stance on Frank's guilt or innocence. The case has inspired books, movies, a play, a musical, and a TV miniseries. | |||

| Less than four weeks later, Frank narrowly survived a prison attack in which his throat was slashed. He was treated in the prison infirmary, where he remained for one month. While still undergoing treatment, he was kidnapped from the penitentiary by a group of 25 armed men who called themselves "Knights of Mary Phagan". Frank was driven 170 miles from Milledgeville to Frey's Gin at the perimeter of Atlanta, near Phagan's former home in Marietta, and lynched. A crowd gathered after the hanging and photographs were made that were turned into postcards. After Frank was cut down, bits of the hangman's noose were taken as souvenirs and one gawker stomped on Frank's face. | |||

| The African American press condemned the lynching, but many African Americans also opposed Frank and his supporters over what historian ] described as a "virulently racist" characterization of Jim Conley, who was Black.<ref name="MacLean">] (December 1991) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230401223444/https://history.msu.edu/files/2010/04/Nancy-MacLean.pdf |date=April 1, 2023 }}. '']'', v. 78, n. 3, pp. 917–948</ref> | |||

| His case spurred the creation of the ] and the resurgence of the ].<ref>{{cite web |title=100 Years Since the Death of Leo Frank |url=https://www.britannica.com/story/100-years-since-the-death-of-leo-frank |website=www.britannica.com |language=en |access-date=October 14, 2022 |archive-date=February 5, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240205062633/https://www.britannica.com/story/100-years-since-the-death-of-leo-frank |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| {{toc limit|3}} | |||

| ==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| ===Social and economic conditions=== | |||

| In the early 20th century, Atlanta, Georgia's capital city, underwent significant economic and social change. To serve a growing economy based on manufacturing and commerce, many people left the countryside to relocate in Atlanta.<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, pp. 7–8.</ref><ref>MacLean p. 921.</ref> Men from the traditional rural society felt it degrading that women were moving to the city to work in factories.<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, p. 10.</ref> | |||

| ===Leo Frank=== | |||

| Frank was born in ]<ref>Frey p. 19.</ref> on April 17, 1884 to Rudolph Frank and Rachel "Rae" Jacobs.<ref name=Oney10>Oney 2003, p. 10.</ref> The family moved to ] in 1884 when Frank was three months old.<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, p. 5.</ref> He attended New York City public schools and graduated from ] in 1902. He then attended ], where he studied mechanical engineering. After graduation in 1906, Frank worked briefly as a draftsman and as a testing engineer.<ref name="Frey20">Frey p. 20.</ref> | |||

| During this era, Atlanta's rabbis and Jewish community leaders helped to resolve animosity toward Jews. In the half-century from 1895, David Marx was a prominent figure in the city. In order to aid assimilation, Marx's ] temple adopted Americanized appearances. Friction developed between the city's German Jews, who were integrated, and Russian Jews who had recently immigrated. Marx said the new Russian Jews were "barbaric and ignorant" and believed their presence would create new antisemitic attitudes and a situation which made possible Frank's guilty verdict.<ref name="p. 231">Lindemann .</ref> Despite their success, many Jews recognized themselves as different from the Gentile majority and were uncomfortable with their image.{{refn|A 1900 Jewish newspaper in Atlanta wrote that "no one knows better than publishers of Jewish papers how widespread is this prejudice; but these publishers do not and will not tell what they know of the smooth talking Jew-haters, because it would widen the breech already existent."<ref>Dinnerstein 1994, .</ref>|group=n}} Despite his own acceptance by ]s, Marx believed that "in isolated instances there is no prejudice entertained for the individual Jew, but there exists wide-spread and deep seated prejudice against Jews as an entire people."<ref name="Dinnerstein 1994 181">Dinnerstein 1994, .</ref>{{refn|Dinnerstein wrote, "Men wore neither skullcaps nor prayer shawls, traditional Jewish holidays that the Orthodox celebrated on two days were observed by Marx and his followers for only one, and religious services were conducted on Sundays rather than on Saturdays."<ref name="Dinnerstein 1994 181" />|group=n}}{{refn|Lindemann writes, "As in the rest of the nation at this time, there were new sources of friction between Jews and Gentiles, and in truth the worries of the German-Jewish elite about the negative impact of the newly arriving eastern European Jews in the city were not without foundation."<ref name="p. 231"/>|group=n}} | |||

| At the invitation of his uncle Moses Frank, Leo traveled to Atlanta for two weeks in late October 1907 to meet a delegation of investors for a position with the National Pencil Company, a manufacturing plant in which Moses was a major shareholder.<ref name=Oney10/> Frank accepted the position, and traveled to Germany to study pencil manufacturing at ] in ]. After a nine-month apprenticeship, Frank returned to the United States and began working at the National Pencil Company in August 1908.<ref name="Frey20"/> Leo Frank became superintendent of the factory in September 1908. | |||

| An example of the type of tension that Marx feared occurred in April 1913: at a conference on ], some participants blamed the problem, in part, on the fact that many factories were Jewish-owned.<ref>Oney p. 7.</ref> Historian ] summarized Atlanta's situation in 1913 as follows: | |||

| Frank was introduced to Lucille Selig shortly after he arrived in Atlanta.<ref>Oney 2003, p. 80.</ref> She came from a prominent and upper middle class Jewish family of industrialists who, two generations earlier, had founded the first synagogue in Atlanta.<ref> ; Levi Cohen from her maternal lineage had participated in founding the first Synagogue in Atlanta.</ref> Though she was very different from Frank, and laughed at the idea of speaking ], they were married in November 1910, at the Selig residence in Atlanta.<ref>Oney 2003, p. 84.</ref> Frank described his married life as happy. | |||

| {{Quote|The pathological conditions in the city menaced the home, the state, the schools, the churches, and, in the words of a contemporary Southern sociologist, the 'wholesome industrial life.' The institutions of the city were obviously unfit to handle urban problems. Against this background, the murder of a young girl in 1913 triggered a violent reaction of mass aggression, hysteria, and prejudice.<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, p. 9.</ref>}} | |||

| Frank was elected president of the Atlanta chapter of the ], a Jewish fraternal organization, in 1912.<ref>Oney 2003, p. 11.</ref> The Jewish community in Atlanta was the largest in the South, and the Franks moved in a cultured and philanthropic ] whose leisure pursuits included opera and bridge.<ref>Lawson pp. 211, 250.</ref><ref>Phagan p. 111.</ref> Although the American South was not known for its antisemitism, Frank's northern culture and Jewish faith added to the sense that he was different.<ref name=Alphin21>Alphin 2010, p. 21ff, 25ff.</ref> | |||

| === |

===Early life=== | ||

| Leo Max Frank was born in ]<ref>Frey .</ref> on April 17, 1884, to Rudolph Frank and Rachel "Rae" Jacobs.<ref name=Oney10>Oney p. 10.</ref> The family moved to ] when Leo was three months old.<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, p. 5.</ref> He attended ] and graduated from ] in 1902. He then attended ], where he studied mechanical engineering.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Cornell University |date=1906 |title=Cornell Register 1905-1906 |url=https://ecommons.cornell.edu/items/f14daefc-c56e-45f7-812e-5639dcd3c93d |journal=The Register: Cornell University |language=en-US |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240624100914/https://ecommons.cornell.edu/items/f14daefc-c56e-45f7-812e-5639dcd3c93d |archive-date=June 24, 2024 |access-date=December 23, 2024 |url-status=live }}</ref> At Cornell, Frank was a member of the ] Debate Club.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Cornell ... class book 1906. |url=https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924050396039&seq=291&q1=leo+frank |access-date=2024-12-23 |website=HathiTrust |language=en}}</ref> After graduating in 1906, he worked briefly as a draftsman and as a testing engineer.<ref name="Frey20">Frey .</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| At the invitation of his uncle Moses Frank, Leo traveled to Atlanta for two weeks in late October 1907, to meet a delegation of investors for a position with the National Pencil Company, a manufacturing plant in which Moses was a major shareholder.<ref name=Oney10/> Frank accepted the position, and traveled to Germany to study pencil manufacturing at the ] pencil factory. After a nine-month apprenticeship, Frank returned to the United States and began working at the National Pencil Company in August 1908.<ref name="Frey20"/> Frank became superintendent of the factory the following month, earning $180 per month plus a portion of the factory's profits.<ref name="Lindemann 251">Lindemann .</ref> | |||

| Mary Phagan (June 1, 1899 – April 26, 1913){{#tag:ref|Although Phagan's gravestone lists her year of birth as 1900, modern secondary sources agree with her mother's assertion that she was in fact born in 1899.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=11655|title=Mary Phagan (1899–1913) – Find A Grave Memorial|date=August 8, 2000|accessdate=November 20, 2014}}</ref>|group=n}} was born in ], four months after her father William Joshua Phagan died of ].<ref>Phagan p. 11.</ref> She was born into a family of tenant farmers who had farmed in Alabama and Georgia for generations. After her father died, Phagan's mother moved the family to ] in southwest Atlanta, where she opened a boarding house.<ref>Phagan p. 12.</ref> The children took jobs in the local mills. Phagan left school at the age of 10 to work part-time in a textile mill.<ref name="Oney5">Oney 2003, p. 5.</ref> In 1911, a paper manufacturing plant owned by Sigmund Montag, treasurer of the National Pencil Company, hired her. In 1912, her mother, Frances Phagan, married John William Coleman, and she and the children moved into the city.<ref>Phagan p. 14.</ref> Phagan took a job with the National Pencil Company in the spring of 1912, where she ran a knurling machine that inserted rubber erasers into pencils' ].<ref name="Oney5"/> Mary Phagan earned $4.05 per week, working 55 hours and earning 7 and 4/11 cents per hour.<ref>John Milton Gantt, former NPCo paymaster, testifying at the Coroner's Inquest, Atlanta Constitution, May 1913.</ref> In comparison, Leo Frank earned $180 per month, plus a portion of the factory's profits.<ref name="Lindemann 251">Lindemann 1991, p. 251.</ref> | |||

| Frank was introduced to Lucille Selig shortly after he arrived in Atlanta.<ref>Oney p. 80.</ref> She came from a prominent, upper-middle class Jewish family of industrialists who, two generations earlier, had founded the first synagogue in Atlanta.{{refn|Levi Cohen, from her maternal lineage, had participated in founding the first synagogue in Atlanta.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100612233953/http://artery.org/Selig-PioneerNeon.htm |date=June 12, 2010 }} Marietta Street ARTery Association.</ref>|group=n}} They married in November 1910.<ref>Oney p. 84.</ref> Frank described his married life as happy.<ref>Oney pp. 85, 483.</ref> | |||

| ==Murder of Mary Phagan== | |||

| In 1912, Frank was elected president of the Atlanta chapter of the ], a Jewish fraternal organization.<ref>Oney p. 11.</ref> The Jewish community in Atlanta was the largest in the ], and the Franks belonged to a cultured and philanthropic community whose leisure pursuits included opera and bridge.<ref>Lawson pp. 211, 250.</ref><ref>Phagan Kean p. 111.</ref> Although the Southern United States was not specifically known for its antisemitism, Frank's northern culture and Jewish faith added to the sense that he was different.<ref>Alphin p. 26.</ref> | |||

| ===Discovery=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ==Murder of Mary Phagan<span class="anchor" id="Mary Phagan"></span> == | |||

| Phagan worked in the metal room on the second floor of the factory<ref>Frey p. 5.</ref> in a section called the tipping department, across the hallway from Frank's office. She had been laid off on April 21 due to a shortage of brass sheet metal.<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 8–9.</ref> About noon on April 26, she went to the factory to claim her pay of $1.20. At about 3:15 a.m. on April 27, the factory's nightwatchman, Newt Lee, went to the factory basement to use the "]" toilet.<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, p. 1.</ref> Lee said he discovered the body of a dead girl, tried to call Leo Frank and failing to reach him, called the police, meeting them at the front door and leading them to the body. | |||

| ] | |||

| {{For|the television miniseries based on the story|The Murder of Mary Phagan (TV miniseries)}} | |||

| ===Phagan's early life=== | |||

| Mary Phagan's body was found dumped in the rear of the basement near an incinerator. Her dress was hiked up around her waist and a strip from her petticoat had been torn off and wrapped around her neck. Her face was blackened and scratched. Her head was bruised and battered. A seven-foot strip of quarter-inch wrapping cord tied into a loop was around her neck buried a quarter inch deep. There was the appearance of rape. Her underwear was still around her hips, but torn open across the vagina and stained with blood. Based on the ashes and dirt from the floor that were stuck to her skin, it initially appeared that she and her assailant had struggled in the basement.<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 18–19.</ref> | |||

| Mary Phagan was born on June 1, 1899, into a Georgia family of tenant farmers.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qf8zAQAAQBAJ&pg=PT8|page=8|title=Murder at the Pencil Factory: The Killing of Mary Phagan 100 Years Later|author=R. Barri Flowers|date=October 6, 2013|publisher=True Crime}}</ref><ref>Phagan Kean p. 11.</ref> Her father died before she was born. Shortly after Mary's birth, her mother, Frances Phagan, moved the family back to their hometown of ].<ref name="Phagan14">Phagan Kean p. 14.</ref> During or after 1907, they again relocated to ], in southwest Atlanta, where Frances opened a boarding house.<ref>Phagan Kean pp. 12, 14.</ref> Phagan left school at age 10 to work part-time in a textile mill.<ref name="Oney5">Oney p. 5.</ref> In 1912, after her mother married John William Coleman, the family moved into the city of Atlanta.<ref name="Phagan14"/> That spring, Phagan took a job with the National Pencil Company, where she earned ten cents an hour operating a ] machine that inserted rubber erasers into the metal tips of pencils, and worked 55 hours per week.<ref name="Oney5"/>{{refn|Oney writes, "Ordinarily, she was scheduled to work fifty-five hours. During the past six days, however, she'd been needed only for two abbreviated shifts. The sealed envelope awaiting her in her employer's office safe contained just $1.20."<ref name="Oney 8-9">Oney pp. 8–9.</ref>|group=n}} She worked across the hallway from Leo Frank's office.<ref name="Oney5"/><ref>Frey .</ref> | |||

| ===Discovery of Phagan's body=== | |||

| A service ramp at the rear of the basement led to a sliding door that opened into the alley; the police found it had been tampered with so it could be opened without unlocking it. Later examination found bloody fingerprints on the door, as well as a metal pipe that had been used as a crowbar.<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 20–22.</ref> Some evidence at the crime scene was improperly handled by the police investigators. A trail in the dirt (from the elevator shaft) along which police believed Phagan had been dragged was trampled and no footprints were ever identified.<ref name=Oney30>Oney 2003, pp. 30–31.</ref> | |||

| On April 21, 1913, Phagan was laid off due to a materials shortage.<ref name="Oney 8-9" /> Around noon on April 26, she went to the factory to claim her pay. The next day, shortly before 3:00 a.m., the factory's night watchman, Newt Lee, went to the factory basement to use the toilet.<ref>Oney p. 21.</ref> After leaving the toilet, Lee discovered Phagan's body in the rear of the basement near an incinerator and called the police. | |||

| Two notes were found in a pile of rubbish by Phagan's head, and became known as the "murder notes". One said: "he said he wood love me land down play like the night witch did it but that long tall black negro did boy his slef." The other said, "mam that negro hire down here did this i went to make water and he push me down that hole a long tall negro black that hoo it wase long sleam tall negro i write while play with me." The effect of the discovery was to cast suspicion on Newt Lee. The phrase "night witch" was interpreted to mean "night watch"; when the notes were initially read aloud, night watchman Newt Lee said, "Boss, it looks like they are trying to lay it on me" (or words to that effect).<ref>Golden pp. 19, 102.</ref><ref>Oney 2003, pp. 20–21, 379.</ref> | |||

| Her dress was up around her waist and a strip from her petticoat had been torn off and wrapped around her neck. Her face was blackened and scratched, and her head was bruised and battered. A {{convert|7|ft|m|adj=on}} strip of {{convert|1/4|in|mm|adj=on}} wrapping cord was tied into a loop around her neck, buried {{convert|1/4|in|mm|abbr=on}} deep, showing that she had been strangled. Her underwear was still around her hips, but stained with blood and torn open. Her skin was covered with ashes and dirt from the floor, initially making it appear to first responding officers that she and her assailant had struggled in the basement.<ref>Oney pp. 18–19.</ref> | |||

| ===Newspaper coverage=== | |||

| ] | |||

| A service ramp at the rear of the basement led to a sliding door that opened into an alley; the police found the door had been tampered with so it could be opened without unlocking it. Later examination found bloody fingerprints on the door, as well as a metal pipe that had been used as a crowbar.<ref>Oney pp. 20–22.</ref> Some evidence at the crime scene was improperly handled by the police investigators: a trail in the dirt (from the elevator shaft) along which police believed Phagan had been dragged was trampled; the footprints were never identified.<ref name=Oney30>Oney pp. 30–31.</ref> | |||

| '']'' broke the story of the murder and was soon in frenzied competition with '']'' and '']'' for readers. The latter was a formerly sedate local paper bought by the ] syndicate in 1912<ref>Oney 2003, p. 6.</ref> and revamped using his standard formula of ]. As many as 40 extra editions came out the day Phagan's murder was reported. ''The Atlanta Georgian'' published a doctored morgue photo of Phagan, in which her head was shown spliced onto the body of another girl. Some evidence went missing when it was 'borrowed' from the police by reporters. The papers offered a total of $1,800 in reward money for information leading to the apprehension of the murderer.<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 36, 60.</ref> Populist politician and publisher ] also weighed in, when he later printed sensationalistic coverage of the trial in his smaller, but influential, publication ''The Jeffersonian''.<ref name="ATLMAG">{{cite web|url=http://www.atlantamagazine.com/history/people-v-leo-frank-steve-oney|title=The People v. Leo Frank|work=Atlanta Magazine|author=Steve Oney|date=24 September 2013|accessdate=13 February 2015}}</ref> Coverage of the case, in the local press, continued nearly unabated, throughout the investigation, trial, and subsequent appeal process. During the legal appeals, the previously local issue gained national attention when it drew the interest of ], owner of '']'', and others, who gave the story ].<ref name="ATLMAG" /><ref>{{cite web|url=http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/dgkeysearchdetail.cfm?trg=1&strucID=1922730&imageID=psnypl_mss_1310&parent_id=1769226&snum=&s=¬word=&d=&c=&f=&k=1&sScope=&sLevel=&sLabel=&sort=&total=3&num=0&imgs=20&pNum=&pos=1|title=Letter from Leo M. Frank to Adolph Ochs, 1914 Nov 20|date=20 November 1914|accessdate=10 February 2015|publisher=New York Public Library, digital gallery – Stephen A. Schwarzman Building / Manuscripts and Archives}}</ref> Over an 18-month period, ''The New York Times'' published dozens of editorials demanding a new trial for Frank and news articles slanted in his favor.<ref name="LAT">{{cite web|url=http://articles.latimes.com/2009/oct/30/opinion/oe-oney30|title=The Leo Frank case isn't dead|work=Los Angeles Times|author=Steve Oney|date=30 October 2009|accessdate=10 February 2015}}</ref> | |||

| Two notes were found in a pile of rubbish by Phagan's head, and became known as the "murder notes". One said: "he said he wood love me land down play like the night witch did it but that long tall black negro did boy his slef." The other said, "mam that negro hire down here did this i went to make water and he push me down that hole a long tall negro black that hoo it wase long sleam tall negro i write while play with me." The phrase "night witch" was thought to mean "night watch"; when the notes were initially read aloud, Lee, who was black, said: "Boss, it looks like they are trying to lay it on me."{{refn|Lee said that these were his words in his evidence later at the trial.<ref>Golden p. 162</ref>|group=n}} Lee was arrested that morning based on these notes and his apparent familiarity with the body{{spaced en dash}}he stated that the girl was white, when the police, because of the filth and darkness in the basement, initially thought she was black. A trail leading back to the elevator suggested to police that the body had been moved by Lee.<ref>Golden pp. 19, 102.</ref><ref>Oney pp. 20–21, 379.</ref> | |||

| ===Suspicion falls on Frank=== | |||

| On April 27, Frank said that Lee's time card was complete.<ref>Oney 2003, p. 31.</ref> It was supposed to be punched every half hour during the watchman's security rounds. On April 28, Frank said Lee had not punched the card at three or four intervals.<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 49–50.</ref> The police investigated a variety of suspects, and arrested both Lee and a friend of Phagan's for the crime.<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 61–62.</ref> Gradually they became convinced that they were not the culprits. A detective went to Lee's residence looking for evidence and found a blood-smeared shirt at the bottom of a burn barrel.<ref>Oney 2003, p. 65.</ref> The blood was smeared high up on the armpits and the shirt smelled unused. The prosecution later claimed that the shirt had been planted by Frank in order to incriminate Lee. | |||

| ===Police investigation=== | |||

| Newt Lee claimed he tried to call Leo Frank for eight minutes after the discovery of Phagan's body. The police later noted that Frank had not answered the phone when they called his house at 4 a.m., and that he seemed nervous when they took him to the undertaker at P. J. Bloomfield's Mortuary and to the factory. They considered his detailed answers on minor points as suspect and noted his trembling. Frank pointed out at the trial that the police had refused to tell him the nature of their investigation. Phagan's friend, 13-year-old pencil factory worker George Epps, came forward to say that Frank had sexually harassed Phagan and had frightened her.<ref>{{Citation|title=Frank Tried to Flirt with Murdered Girl Says Her Boy Chum|newspaper=]|publication-place=Atlanta, GA|date=May 1, 1913|page=Front page}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| In addition to Lee, the police arrested a friend of Phagan's for the crime.<ref>Oney pp. 61–62.</ref> Gradually, the police became convinced that these were not the culprits. By Monday, the police had theorized that the murder occurred on the second floor (the same as Frank's office) based on hair found on a lathe and what appeared to be blood on the ground of the second floor.<ref>Oney pp. 46–47.</ref> | |||

| The police appeared to intimidate and influence witnesses, such as the Seligs' cook Magnolia "Minola" McKnight, and Nina Formby, the madam of a ]. They both recanted statements made to the police, Formby indicating the police had "plied her with whisky".<ref>''The New York Times'', February 26, 1914.</ref> Frank hired two ] detectives, along with agents from the Burns detective agency, to help him prove his innocence, although all later "publicly expressed their confidence that Frank was guilty beyond any question."<ref>Lindemann 1991, p. 249.</ref> Though Frank produced alibis for the entire time during which the crime could have been committed, stating that he had never left his office between 12:00 noon and 12:45 p.m, suspicion was aroused by his waiting a week to bring forward one crucial alibi witness, Lemmie Quinn who stated he went to Frank's office at 12:20 p.m. and stayed for a few minutes. One eyewitness, Monteen Stover, stated Frank was not in his office when she came to collect her paycheck at 12:05 p.m. Mrs. White, wife of an employee working on the fourth floor, said she saw Frank opening his safe at 12:35 p.m. Meanwhile, the ''Constitution'' continued to criticize the police for their lack of progress.<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 96–97.</ref> | |||

| Just after 4 am on Sunday, April 27 after the discovery of Phagan's body, both Newt Lee and the police unsuccessfully tried to telephone Frank.<ref>Oney p. 31.</ref> The police contacted him later that morning and he agreed to accompany them to the factory.<ref>Phagan Kean p. 76.</ref> When the police arrived after 7 a.m. without telling the specifics of what happened at the factory, Frank seemed extremely nervous, trembling, and pale; his voice was hoarse, and he was rubbing his hands and asking questions before the police could answer. Frank said he was not familiar with the name Mary Phagan and would need to check his payroll book. The detectives took Frank to the morgue to see Phagan's body and then to the factory, where Frank viewed the crime scene and walked the police through the entire building. Frank returned home about 10:45 a.m. At this point, Frank was not considered a suspect.<ref>Oney pp. 27–32.</ref> | |||

| On Monday, April 28, Frank, accompanied by his attorney, Luther Rosser, gave a written deposition to the police that provided a brief timeline of his activities on Saturday. He said Phagan was in his office between 12:05 and 12:10 p.m., that Lee had arrived at 4 p.m. but was asked to return later, and that Frank had a confrontation with ex-employee James Gantt at 6 p.m. as Frank was leaving and Lee was arriving. Frank explained that Lee's time card for Sunday morning had several gaps (Lee was supposed to punch in every half-hour) that Frank had missed when he discussed the time card with police on Sunday. At Rosser's insistence, Frank exposed his body to demonstrate that he had no cuts or injuries and the police found no blood on the suit that Frank said he had worn on Saturday. The police found no blood stains on the laundry at Frank's house.<ref>Oney pp. 48–51.</ref> | |||

| Frank then met with N. V. Darley, his assistant, and Harry Scott of the ], whom Frank hired to investigate the case and prove his innocence.<ref>Oney p. 62.</ref> The Pinkerton detectives would investigate many leads, ranging from crime scene evidence to allegations of sexual misconduct on the part of Frank. The Pinkertons were required to submit duplicates of all evidence to the police, including any that hurt Frank's case. Unbeknownst to Frank, however, was Scott's close ties with the police, particularly his best friend, detective John Black, who believed in Frank's guilt from the outset.{{refn|Oney writes: "Yet where Frank may have harbored a hidden agenda, Scott brought with him an undeniable conflict of interests...he was closely tied to the police. Private investigators operating in the city were required to submit duplicate copies of their reports to the department, even if the documents implicated a client. This much Scott would reveal to Frank. What he would not reveal, however, was that his allegiance to the force went deeper than the statutes required, that indeed, one of his best friends, someone with whom he often worked in tandem, was the individual who from the outset had believed Frank guilty: Detective John Black.<ref>Oney p. 62–63.</ref>|group=n}} | |||

| On Tuesday, April 29, Black went to Lee's residence at 11 a.m. looking for evidence, and found a blood-smeared shirt at the bottom of a ].<ref>Oney p. 65.</ref> The blood was smeared high up on the armpits and the shirt smelled unused, suggesting to the police that it was a plant. The detectives, suspicious of Frank due to his nervous behavior throughout his interviews, believed that Frank had arranged the plant.<ref>Oney pp. 65–66.</ref> | |||

| Frank was subsequently arrested around 11:30 a.m. at the factory. Steve Oney states that "no single development had persuaded ... that Leo Frank had murdered Mary Phagan. Instead, to the cumulative weight of Sunday's suspicions and Monday's misgivings had been added several last factors that tipped the scale against the superintendent."<ref>Oney p. 61.</ref> These factors were the rejection of rumors that Phagan had been seen on the streets, making Frank the last person to admit seeing Phagan; the dropped charges against two suspects; Frank's meeting with the Pinkertons; and a "shifting view of Newt Lee's role in the affair."<ref>Oney pp. 63–64.</ref> The police were convinced Lee was involved as Frank's accomplice and that Frank was trying to implicate him. To bolster their case, the police staged a confrontation between Lee and Frank while both were still in custody; there were conflicting accounts of this meeting, but the police interpreted it as further implicating Frank.<ref>Oney pp. 69–70.</ref> | |||

| On Wednesday, April 30, a ] was held. Frank testified about his activities on Saturday and other witnesses produced corroboration. A young man said that Phagan had complained to him about Frank. Several former employees spoke of Frank flirting with other women; one said she was actually propositioned. The detectives admitted that "they so far had obtained no conclusive evidence or clues in the baffling mystery ...". Lee and Frank were both ordered to be detained.<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, pp. 16–17.</ref> | |||

| In May, the detective ] traveled to Atlanta to offer further assistance in the case.<ref>Oney p. 102.</ref> However, his ] withdrew from the case later that month. C. W. Tobie, a detective from the Chicago affiliate who was assigned to the case, said that the agency "came down here to investigate a murder case, not to engage in petty politic."<ref>Oney p. 112.</ref> The agency quickly became disillusioned with the many societal implications of the case, most notably the notion that Frank was able to evade prosecution due to his being a rich Jew, buying off the police and paying for private detectives.<ref>Oney p. 111.</ref> | |||

| ===James "Jim" Conley=== | ===James "Jim" Conley=== | ||

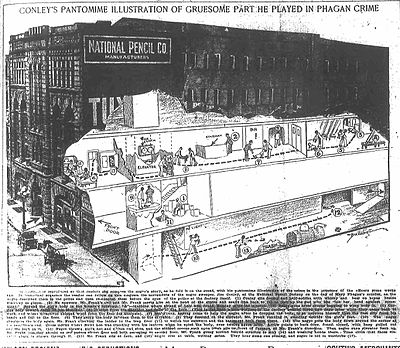

| ]'']] | |||

| Jim Conley, the factory's janitor, is believed by some historians to be the murderer.<ref>For example: | |||

| *: "The best evidence now available indicates that the real murderer of Mary Phagan was Jim Conley, perhaps because she, encountering him after she left Frank's office, refused to give him her pay envelope, and he, in a drunken stupor, killed her to get it. | |||

| *Woodward 1963, p. 435: "The city police, publicly committed to the theory of Frank's guilt, and hounded by the demand for a conviction, resorted to the basest methods in collecting evidence. A Negro suspect , later implicated by evidence overwhelmingly more incriminating than any produced against Frank, was thrust aside by the cry for the blood of the 'Jew Pervert.'"</ref> | |||

| On May 1, the police arrested Conley after he was seen by the plant's day watchman, E. F. Holloway, washing a dirty blue work shirt. Conley tried to hide the shirt, then said the stains were rust from the overhead pipe on which he had hung it. Detectives examined it for blood, found none, and returned it. Conley was still in police custody two weeks later when he gave his first formal statement. He said that, on the day of the murder, he had been visiting saloons, shooting dice, and drinking. He offered some details, such as 40 cents spent on a bottle of rye, 90 cents won at dice, and 15 cents for beer, twice.<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 118–119.</ref> His story was called into question when a witness told detectives that "a black negro . . . dressed in dark blue clothing and hat" had been seen in the lobby of the factory on the day of the murder. Further investigation also determined that Conley could read and write, something he had initially denied.<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 128–129.</ref> | |||

| The prosecution based much of its case on the testimony of Jim Conley, the factory's janitor, who is believed by many historians to be the actual murderer.{{refn|For example: "The best evidence now available indicates that the real murderer of Mary Phagan was Jim Conley, perhaps because she, encountering him after she left Frank's office, refused to give him her pay envelope, and he, in a drunken stupor, killed her to get it."<ref>Lindemann .</ref> "The city police, publicly committed to the theory of Frank's guilt, and hounded by the demand for a conviction, resorted to the basest methods in collecting evidence. A Negro suspect , later implicated by evidence overwhelmingly more incriminating than any produced against Frank, was thrust aside by the cry for the blood of the 'Jew Pervert.{{'"}}<ref name="Woodward 435">Woodward p. 435.</ref>|group=n}} The police had arrested Conley on May 1 after he had been seen washing red stains out of a blue work shirt; detectives examined it for blood, but determined that it was rust as Conley had claimed, and returned it.<ref>Oney p. 118.</ref> Conley was still in police custody two weeks later when he gave his first formal statement. He said that, on the day of the murder, he had been visiting saloons, shooting dice, and drinking. His story was called into question when a witness told detectives that "a black negro ... dressed in dark blue clothing and hat" had been seen in the lobby of the factory on the day of the murder. Further investigation determined that Conley could read and write,<ref>Oney pp. 128–129.</ref> and there were similarities in his spelling with that found on the murder notes. On May 24, he admitted he had written the notes, swearing that Frank had called him to his office the day before the murder and told him to write them.<ref>Oney pp. 129–132.</ref> After testing Conley again on his spelling{{spaced en dash}}he spelled "night watchman" as "night witch"{{spaced en dash}}the police were convinced he had written the notes. They were skeptical about the rest of his story, not only because it implied premeditation by Frank, but also because it suggested that Frank had confessed to Conley and involved him.<ref name=Oney133>Oney pp. 133–134.</ref> | |||

| After initially sticking to his claim that he could not write, he was threatened with perjury charges. He was asked to write portions of the murder notes, and although the police found similarities in the spelling, he continued to deny having written them. The interview ended and Conley was placed in a basement isolation cell. A week later, on May 24, he called for a detective and admitted he had written the notes. In a sworn statement, he said Frank had called him to his office the day before the murder; he claimed Frank said he had some wealthy people in Brooklyn, and asked: "Why should I hang?"<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 129–132.</ref> | |||

| In a new affidavit (his second affidavit and third statement), Conley admitted he had lied about his Friday meeting with Frank. He said he had met Frank on the street on Saturday, and was told to follow him to the factory. Frank told him to hide in a wardrobe to avoid being seen by two women who were visiting Frank in his office. He said Frank dictated the murder notes for him to write, gave him cigarettes, then told him to leave the factory. Afterward, Conley said he went out drinking and saw a movie. He said he did not learn of the murder until he went to work on Monday.<ref name="Oney 134-136">Oney pp. 134–136.</ref> | |||

| {{quote|e asked me could I write and I told him yes I could write a little bit, and he gave me a scratch pad and ... told me to put on there "dear mother, a long, tall, black negro did this by himself," and he told me to write it two or three times on there. I wrote it on a white scratch pad, single ruled. He went to his desk and pulled out another scratch pad, a brownish looking scratch pad, and looked at my writing and wrote on that himself.<ref>Oney 2003, p. 131.</ref>}} | |||

| After testing Conley again on his spelling—he spelled "night watchman" as "night witch"—the police were convinced he had written the notes. They were skeptical about the rest of his story, not only because it implied premeditation by Frank, but also because it suggested that Frank had confessed to Conley and involved him.<ref name=Oney133>Oney 2003, pp. 133–134.</ref> | |||

| The police were satisfied with the new story, and both ''The Atlanta Journal'' and ''The Atlanta Georgian'' gave the story front-page coverage. Three officials of the pencil company were not convinced and said so to the ''Journal''. They contended that Conley had followed another employee into the building, intending to rob her, but found Phagan was an easier target.<ref name="Oney 134-136"/> The police placed little credence in the officials' theory, but had no explanation for the failure to locate Phagan's purse that other witnesses had testified she carried that day.<ref>Oney p. 3.</ref> They were also concerned that Conley did not mention that he was aware a crime had been committed when he wrote the notes, suggesting Frank had simply dictated the notes to Conley arbitrarily. To resolve their doubts, the police attempted on May 28 to arrange a confrontation between Frank and Conley. Frank exercised his right not to meet without his attorney, who was out of town. The police were quoted in ''The Atlanta Constitution'' saying that this refusal was an indication of Frank's guilt, and the meeting never took place.<ref>Oney pp. 137–138.</ref> | |||

| In a new affidavit (his second affidavit and third statement), Conley admitted he had lied about his Friday meeting with Frank. He said he had met Frank on the street on Saturday, and was told to follow him to the factory. Frank told him to hide in a wardrobe to avoid being seen by two women who were visiting Frank in his office. He said Frank dictated the murder notes for him to write, gave him cigarettes, and told him to leave the factory. Afterward, Conley said he went out drinking and saw a movie. He said he did not learn of the murder until he went to work on Monday.<ref name="Oney 134-136">Oney 2003, pp. 134–136.</ref> | |||

| On May 29, Conley was interviewed for four hours.<ref>Oney p. 138.</ref><ref>Dinnerstein 1987, p. 24.</ref> His new affidavit said that Frank told him, "he had picked up a girl back there and let her fall and that her head hit against something." Conley said he and Frank took the body to the basement via the elevator, then returned to Frank's office where the murder notes were dictated. Conley then hid in the wardrobe after the two had returned to the office. He said Frank gave him $200, but took it back, saying, "Let me have that and I will make it all right with you Monday if I live and nothing happens." Conley's affidavit concluded, "The reason I have not told this before is I thought Mr. Frank would get out and help me out and I decided to tell the whole truth about this matter."<ref>Oney pp. 139–140.</ref> At trial, Conley changed his story concerning the $200. He said Frank decided to withhold the money until Conley had burned Phagan's body in the basement furnace.<ref>Oney p. 242.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The ''Georgian'' hired ] to represent Conley for $40. Smith was known for specializing in representing black clients, and had successfully defended a black man against an accusation of rape by a white woman. He had also taken an elderly black woman's civil case as far as the Georgia Supreme Court. Although Smith believed Conley had told the truth in his final affidavit, he became concerned that Conley was giving long jailhouse interviews with crowds of reporters. Smith was also anxious about reporters from the ] papers, who had taken Frank's side. He arranged for Conley to be moved to a different jail, and severed his own relationship with the ''Georgian''.<ref>Oney pp. 147–148.</ref> | |||

| The police were satisfied with the new story, and both '']'' and the ''Georgian'' gave the story front-page coverage. Three officials of the pencil company were not convinced and said so to the ''Journal''. They contended Conley had followed another employee into the building intending to rob her, but instead found Phagan was a more ready target.<ref name ="Oney 134-136"/> The police placed little credence in the employees' theory, but had no explanation for the failure to locate the purse (that other witnesses had testified she carried that day),<ref>Oney 2003, p. 3.</ref> and were concerned that Conley had made no mention that he was aware that a crime had been committed when he wrote the notes. To resolve their doubts, the police attempted on May 28 to arrange a confrontation between Frank and Conley. Frank exercised his right not to meet without his attorney, who was out of town. The police announced this refusal was an indication of Frank's guilt, and the meeting never took place.<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 137–138.</ref> | |||

| On February 24, 1914, Conley was sentenced to a year in jail for being an accomplice after the fact to Phagan's murder.<ref>Frey .</ref> | |||

| On May 29, Conley was interviewed for four hours.<ref>Oney 2003, p. 138.</ref><ref>Dinnerstein 1987, p. 24.</ref> His new affidavit said that Frank told him, "he had picked up a girl back there and let her fall and that her head hit against something." Conley said he and Frank took the body to the basement via the elevator, then returned to Frank's office where the murder notes were dictated. Conley then hid in the wardrobe after the two had returned to the office. He said Frank gave him two hundred dollars, but took it back, saying, “Let me have that and I will make it all right with you Monday if I live and nothing happens." Conley's affidavit concluded, "The reason I have not told this before is I thought Mr. Frank would get out and help me out and I decided to tell the whole truth about this matter."<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 139–140.</ref> At trial, Conley changed his story concerning the $200. He said the money was withheld until Conley had burned Phagan's body in the basement furnace.<ref>Oney 2003, p. 242.</ref> | |||

| ===Media coverage=== | |||

| The ''Georgian'' hired ] to represent Conley for $40. Smith was known for specializing in representing black clients, and had successfully defended a black man against an accusation of rape by a white woman. He had also taken an elderly black woman's civil case as far as the ]. Although Smith believed Conley had told the truth in his final affidavit, he became concerned that Conley was giving long jailhouse interviews with crowds of reporters. Smith was also concerned about reporters from the Hearst papers, who had taken Frank's side. He arranged for Conley to be moved to a different jail, and severed his own relationship with the ''Georgian''.<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 147–148.</ref> {{-}} | |||

| ] | |||

| '']'' broke the story of the murder and was soon in competition with '']'' and '']''. Forty extra editions came out the day Phagan's murder was reported. ''The Atlanta Georgian'' published a doctored morgue photo of Phagan, in which her head was shown spliced onto the body of another girl. The papers offered a total of $1,800 in reward money for information leading to the apprehension of the murderer.<ref>Oney pp. 36, 60.</ref> Soon after the murder, Atlanta's mayor criticized the police for their steady release of information to the public. The governor, noting the reaction of the public to press ] soon after Lee's and Frank's arrests, organized ten militia companies in case they were needed to repulse mob action against the prisoners.<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, p. 15.</ref> Coverage of the case in the local press continued nearly unabated throughout the investigation, trial, and subsequent appeal process. | |||

| ==Indictment, trial, and sentencing== | |||

| ] | |||

| Newspaper reports throughout the period combined real evidence, unsubstantiated rumors, and journalistic speculation. Dinnerstein wrote, "Characterized by innuendo, misrepresentation, and distortion, the ] account of Mary Phagan's death aroused an anxious city, and within a few days, a shocked state."<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, p. 14.</ref> Different segments of the population focused on different aspects. Atlanta's working class saw Frank as "a defiler of young girls", while the German-Jewish community saw him as "an exemplary man and loyal husband."<ref>Oney pp. 74, 87–90.</ref> Albert Lindemann, author of ''The Jew Accused'', opined that "ordinary people" may have had difficulty evaluating the often unreliable information and in "suspend judgment over a long period of time" while the case developed.<ref>Lindemann .</ref> As the press shaped public opinion, much of the public's attention was directed at the police and the prosecution, whom they expected to bring Phagan's killer to justice. The prosecutor, ], had recently lost two high-profile murder cases; one state newspaper wrote that "another defeat, and in a case where the feeling was so intense, would have been, in all likelihood, the end of Mr. Dorsey, as solicitor."<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, p. 19.</ref> | |||

| ===Indictment=== | |||

| Shortly after Leo Frank's April 29 arrest, his family approached ] with the offer of a substantial fee, $5,000 in return for taking on Frank's legal defense. Watson, who opposed the death penalty, "enjoyed a formidable reputation" as a defense attorney in capital cases. Well known as a ] politician, and advocate for the poor, Watson declined the offer.<ref>Lindemann 1991, pp. 260–264.</ref> On May 24, 1913, a murder ] was returned against Frank by a ]. The grand jury included five Jews. As historian ] suggests, "they were persuaded by the concrete evidence that Dorsey presented."<ref name="Lindemann 251"/> Lindemann notes that none of Conley's testimony was presented to the grand jury, and that later, during the trial, Dorsey "explicitly denounced racial anti-Semitism" and "indulged in ... philo-Semitic rhetoric."<ref name="Lindemann 251"/> | |||

| ==Trial== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ], later governor of Georgia]] | |||

| On May 23, 1913, a ] convened to hear evidence for an ] against Frank for the murder of Phagan. The prosecutor, Hugh Dorsey, presented only enough information to obtain the indictment, assuring the jury that additional information would be provided during the trial. The next day, May 24, the jury voted for an indictment.<ref>Oney pp. 115–116, 236.</ref> Meanwhile, Frank's legal team suggested to the media that Jim Conley was the actual killer and put pressure on another grand jury to indict him. The jury foreman, on his own authority, convened the jury on July 21; on Dorsey's advice, they decided not to indict Conley.<ref>Oney pp. 178–188.</ref> | |||

| The trial began on July 28 at the Fulton County Superior Court (old city hall building). The courtroom was on the first floor and the windows were left open because of the heat. In addition to the hundreds of spectators inside, a large crowd gathered outside to watch the trial through the windows. Afterward the defense cited the crowds as factors in intimidation of the witnesses and jury in their legal appeals.<ref>Knight 1996, p. 189.</ref> | |||

| The State's prosecution team was made up of the Solicitor General ], Assistant Solicitor General Frank Arthur Hooper and E. A. Stevens. Frank was represented by eight lawyers (some of them jury selection specialists), led by Luther Z. Rosser and Reuben R. Arnold. The defense used ]s to eliminate the only two black jurors. The prosecution case was that Conley's last affidavit was true, Frank murdered Phagan in the machine room (colloquially known as the metalroom), and the murder notes had been dictated by Frank in an effort to pin the crime on Lee. The defense case was that Conley was the murderer, he wrote the notes alone, assaulted Phagan in the lobby of the factory and his evidence was a fabrication.<ref>Golden pp. 118–139.</ref> The defense brought numerous witnesses who attested to Frank's alibi, which did not leave him enough time to have committed the crime.<ref>Phagan p. 105.</ref> | |||

| On July 28, the trial began at the Fulton County Superior Court (old city hall building). The judge, Leonard S. Roan, had been serving as a judge in Georgia since 1900.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171017024739/http://www.gaappeals.us/history/judges.php?id=05 |date=October 17, 2017 }} Court of Appeals of the State of Georgia.</ref> The prosecution team was led by Dorsey and included William Smith (Conley's attorney and Dorsey's jury consultant). Frank was represented by a team of eight lawyers{{spaced en dash}}including jury selection specialists{{spaced en dash}}led by Luther Rosser, Reuben Arnold, and Herbert Haas.<ref>Oney p. 191.</ref> In addition to the hundreds of spectators inside, a large crowd gathered outside to watch the trial through the windows. The defense, in their legal appeals, would later cite the crowds as factors in intimidation of the witnesses and jury.<ref>Knight .</ref> | |||

| Conley reiterated his testimony from his final affidavit. He added to it by describing Frank as regularly having sex with women in his upstairs office on Saturdays while Conley kept a lookout on the ground floor lobby, and also claimed that he had seen Frank performing ] on female employees.<ref>Golden p. 122.</ref> Another witness, C. Brutus Dalton who, like Conley, had a criminal record, corroborated Conley. Although Conley admitted that he had changed his story and lied repeatedly, this did not damage the prosecution's case as much as might have been expected, as he admitted to being an accessory.<ref>For basic details of the murder, see , 106; see p. 99 for the flirting allegation. | |||

| *For Lindemann's comment, see . | |||

| *For the various interests at stake, see . | |||

| *For the Tom Watson quote, see . | |||

| *For the stereotyping of Conley by Frank's defense team, see .</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Many white observers did not believe that a black man could have been intelligent enough to make up such a complicated final story. The ''Georgian'' wrote on 29 May, "Many people are arguing to themselves that the Negro, no matter how hard he tried or how generously he was coached, still never could have framed up a story like the one he told unless there was some foundation in fact."<ref>{{cite book|last1=Ziedenberg|first1=Gerald|title=Epic Trials in Jewish History|date=2012|publisher=AuthorHouse|page=60}}</ref> Defense witnesses testified that there were too many people in the factory on Saturdays for Frank to have had trysts there. They pointed out that the windows of Frank's second-floor office lacked curtains. Though numerous girls testified to Frank having a bad character for lasciviousness, a significantly larger number of female factory workers testified for the defense of Frank's good character when it came to women.<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 308–311.</ref> | |||

| Both legal teams, in planning their trial strategy, considered the implications of trying a white man based on the testimony of a black man in front of an early 1900s Georgia jury. Jeffrey Melnick, author of ''Black-Jewish Relations on Trial: Leo Frank and Jim Conley in the New South'', writes that the defense tried to picture Conley as "a new kind of African American{{spaced en dash}}anarchic, degraded, and dangerous."<ref name="Melnick41">Melnick .</ref> Dorsey, however, pictured Conley as "a familiar type" of "old negro", like a minstrel or plantation worker.<ref name=Melnick41/> Dorsey's strategy played on prejudices of the white 1900s Georgia observers, i.e., that a black man could not have been intelligent enough to make up a complicated story.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lEsv3zPuWGIC&pg=PA59|author=Gerald Ziedenberg|page=59|title=Epic Trials in Jewish History|date=2012|publisher=AuthorHouse|isbn=978-1-4772-7060-8|access-date=September 22, 2020|archive-date=July 9, 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240709144102/https://books.google.com/books?id=lEsv3zPuWGIC&pg=PA59#v=onepage&q&f=false|url-status=live}}</ref> The prosecution argued that Conley's statement explaining the immediate aftermath of the murder was true, that Frank was the murderer, and that Frank had dictated the murder notes to Conley in an effort to pin the crime on Newt Lee, the night watchman.<ref name=Dinnerstein37,58>Dinnerstein 1987, pp. 37, 58.</ref> | |||

| Frank spoke on his own behalf, making an unsworn statement as allowed by Georgia law; it did not permit any cross-examination without his consent, and none occurred.<ref>Oney 2003, p. 297.</ref> Most of his four-hour speech consisted of a detailed analysis of the accounting work he had done the day of the murder.<ref>Oney 2003, pp. 300–303.</ref> He ended with a description of how he viewed the crime, along with an explanation of his nervousness: | |||

| "Gentlemen, I was nervous. I was completely unstrung. Imagine yourself called from sound slumber in the early hours of the morning ... To see that little girl on the dawn of womanhood so cruelly murdered—it was a scene that would have melted stone."<ref>Oney 2003, p. 303.</ref> | |||

| To support their theory that the murder occurred on the factory's second floor in the machine room near Frank's office, the prosecution presented witnesses who testified to bloodstains and strands of hair found on the lathe.<ref name=Dinnerstein37,58/><ref>Oney p. 233.</ref> The defense denied that the murder occurred on the second floor. Both sides contested the significance of physical evidence that suggested the place of the murder. Material found around Phagan's neck was shown to be present throughout the factory. The prosecution interpreted the scene in the basement to support Conley's story{{spaced en dash}}that the body was carried there by elevator{{spaced en dash}}while the defense suggested that the drag marks on the floor indicated that Conley carried the body down a ladder and then dragged it across the floor.<ref>Oney pp. 208–209, 231–232.</ref> The defense argued that Conley was the murderer and that Newt Lee helped Conley write the two murder notes. The defense brought many witnesses to support Frank's account of his movements, which indicated he did not have enough time to commit the crime.<ref>Golden pp. 118–139.</ref><ref>Phagan Kean p. 105.</ref><ref>Oney p. 205.</ref> | |||

| ===Closing arguments=== | |||

| The defense, to support their theory that Conley murdered Phagan in a robbery, focused on Phagan's missing purse. Conley claimed in court that he saw Frank place the purse in his office safe, although he denied having seen the purse before the trial. Another witness testified that, on the Monday after the murder, the safe was open and there was no purse in it.<ref>Oney pp. 197, 256, 264, 273.</ref> The significance of Phagan's torn pay envelope was disputed by both sides.<ref>Oney pp. 179, 225, 228.</ref>{{clear left}} | |||

| In its closing statements, the defense attempted to divert suspicion from Frank to Conley. Lead defense attorney Luther Rosser, said to the jury: "Who is Conley? He is a dirty, filthy, black, drunken, lying, nigger."<ref name="Levy 2000">Levy 2000.</ref> Frank had issued a widely publicized statement questioning how the "perjured vaporizings of a black brute" could be accepted in testimony against him.<ref name="Levy 2000"/> | |||

| ===Frank's alleged sexual behavior=== | |||

| The prosecutor compared Frank to ]. He said that Frank had killed Phagan to keep her from talking. With the sensational coverage, public sentiment in Atlanta turned strongly against Frank. The defense requested a mistrial because it felt the jurors had been intimidated by laughing and clapping from the audience, but the motion was denied.<ref>Oney 2003, p. 339.</ref> In case of an acquittal or conviction, the judge feared for the safety of Frank and his lawyers, so he brokered a deal in which they would not be present when the verdict was read. Preparations were made to bring in the National Guard, if needed.<ref name="Crowd">Dinnerstein 1987, pp. 60–61.</ref> | |||

| The prosecution focused on Frank's alleged sexual behavior.{{refn|Lindemann indicates there was a developing stereotype of "wanton, young Jewish males who hungered for fair-haired Gentile women." A familiar stereotype in Europe, it reached Atlanta in the 1890s "with the arrival of eastern European Jews." "Fear of Jewish sexuality may have had a special explosiveness in Atlanta at this time because it could easily connect to a central myth, or cultural theme, in the South{{spaced en dash}}that of the pure, virtuous, yet vulnerable White woman."<ref>Lindemann .</ref>|group=n}} They alleged that Frank, with Conley's assistance, regularly met with women in his office for sexual relations. On the day of the murder, Conley said he saw Phagan go upstairs, from where he heard a scream coming shortly after. He then said he dozed off; when he woke up, Frank called him upstairs and showed him Phagan's body, admitting that he had hurt her. Conley repeated statements from his affidavits that he and Frank took Phagan's body to the basement via the elevator, before returning in the elevator to the office where Frank dictated the murder notes.<ref>Oney pp. 241–243.</ref><ref>Dinnerstein 1987, pp. 40–41.</ref> | |||

| Conley was cross-examined by the defense for 16 hours over three days, but the defense failed to break his story. The defense then moved to have Conley's entire testimony concerning the alleged rendezvous stricken from the record. Judge Roan noted that an early objection might have been upheld, but since the jury could not forget what it had heard, he allowed the evidence to stand.<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, pp. 45–47, 57.</ref><ref>Oney pp. 245–247, 252–253, 258–259, 265–266, 279.</ref> The prosecution, to support Frank's alleged expectation of a visit from Phagan, produced Helen Ferguson, a factory worker who first informed Phagan's parents of her death.<ref>Oney pp. 75–76.</ref> Ferguson testified that she had tried to get Phagan's pay on Friday from Frank, but was told that Phagan would have to come in person. Both the person behind the pay window and the woman behind Ferguson in the pay line disputed this version of events, testifying that in accordance with his normal practice, Frank did not disburse pay that day.<ref>Oney pp. 273, 280.</ref> | |||

| The defense called a number of factory girls, who testified that they had never seen Frank flirting with or touching the girls and that they considered him to be of good character.<ref>Oney pp. 295–296.</ref> In the prosecution's rebuttal, Dorsey called "a steady parade of former factory workers" to ask them the question, "Do you know Mr. Frank's character for lasciviousness?" The answers were usually "bad".<ref>Oney pp. 309–311.</ref> | |||

| ===Timeline=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The prosecution realized early on that issues relating to time would be an essential part of its case.<ref>Oney p. 115.</ref> At trial, each side presented witnesses to support their version of the timeline for the hours before and after the murder. The starting point was the time of death; the prosecution, relying on the analysis of stomach contents by their expert witness, argued that Phagan died between 12:00 and 12:15 p.m. | |||

| A prosecution witness, Monteen Stover, said she had gone into the office to get her paycheck, waiting there from 12:05 to 12:10, and did not see Frank in his office. The prosecution's theory was that Stover did not see Frank because he was at that time murdering Phagan in the metal room. Stover's account did not match Frank's initial account that he had not left the office between noon and 12:30.<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, pp. 37–40.</ref><ref>Oney pp. 50, 100.</ref> Other testimony indicated that Phagan exited the trolley (or tram) between 12:07 and 12:10. From the stop it was a two- to four-minute walk, suggesting that Stover arrived first, making her testimony and its implications irrelevant: Frank could not be killing Phagan because at the time she had not yet arrived.{{refn|Both the motorman, W. M. Matthews, and the conductor, W. T. Hollis, testified that Phagan got off the trolley at 12:10. In addition, they both testified that Epps was not on the trolley. Epps said at trial that Phagan got off the trolley at 12:07. From the stop where Phagan exited the trolley, according to Atlanta police officer John N. Starnes, "It takes not over three minutes to walk from Marietta Street, at the corner of Forsyth, across the viaduct, and through Forsyth Street, down to the factory."<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, p. 48; Oney pp. 50, 197, 266.</ref>|group=n}}{{refn|Frank stated in his initial police deposition that Phagan "came in between 12:05 and 12:10, to get her pay envelope".<ref>Lawson p. 242.</ref>|group=n}} | |||

| Lemmie Quinn, foreman of the metal room, testified that he spoke briefly with Frank in his office at 12:20.<ref>Oney pp. 278, 285.</ref> Frank had not mentioned Quinn when the police first interviewed him about his whereabouts at noontime on April 26. Frank had said at the coroner's inquest that Quinn arrived less than ten minutes after Phagan had left his office,<ref>Oney pp. 87, 285.</ref> and during the murder trial said Quinn arrived hardly five minutes after Phagan left.<ref>Lawson p. 226.</ref> According to Conley and several experts called by the defense, it would have taken at least thirty minutes to murder Phagan, take the body to the basement, return to the office, and write the murder notes. By the defense's calculations, Frank's time was fully accounted for from 11:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m., except for eighteen minutes between 12:02 and 12:20.<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, p. 49.</ref><ref>Oney p. 359.</ref> Hattie Hall, a stenographer, said at trial that Frank had specifically requested that she come in that Saturday and that Frank had been working in his office from 11:00 to nearly noon. The prosecution labeled Quinn's testimony as "a fraud" and reminded the jury that early in the police investigation Frank had not mentioned Quinn.<ref name="Oney 329">Oney p. 329.</ref> | |||

| Newt Lee, the night watchman, arrived at work shortly before 4:00 and Frank, who was normally calm, came bustling out of his office.<ref>Lawson pp. 182–183.</ref> Frank told Lee that he had not yet finished his own work and asked Lee to return at 6:00.<ref>Dinnerstein 1987, p. 2.</ref> Newt Lee noticed that Frank was very agitated and asked if he could sleep in the packing room, but Frank was insistent that Lee leave the building and told Lee to go out and have a good time in town before coming back.<ref>Phagan Kean p. 70.</ref> | |||

| When Lee returned at 6:00, James Gantt had also arrived. Lee told police that Gantt, a former employee who had been fired by Frank after $2 was found missing from the cash box, wanted to look for two pairs of shoes he had left at the factory. Frank allowed Gantt in, although Lee said that Frank appeared to be upset by Gantt's appearance.<ref>Oney pp. 47–48.</ref> Frank arrived home at 6:25; at 7:00, he called Lee to determine if everything had gone all right with Gantt.<ref>Oney pp. 50–51.</ref>{{clear left}} | |||

| ===Conviction and sentencing=== | ===Conviction and sentencing=== | ||

| During the trial, the prosecution alleged bribery and witness tampering attempts by the Frank legal team.<ref>Phagan Kean p. 160.</ref> Meanwhile, the defense requested a ] because it believed the jurors had been intimidated by the people inside and outside the courtroom, but the motion was denied.{{refn|In its motion for a mistrial, the defense presented examples of the crowd's behavior to the court.<ref>Lawson pp. 398–399.</ref>|group=n}} Fearing for the safety of Frank and his lawyers in case of an ], Roan and the defense agreed that neither Frank nor his defense attorneys would be present when the verdict was read.{{refn|This was challenged as a violation of Frank's ] rights in Frank's appeal to the Georgia Supreme Court in November 1914,<ref>Lawson p. 410, fn. 2.</ref> and in his U.S. Supreme Court appeal, ''Frank v. Mangum'' (1915).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/frank/frankappeals.html|title=Appellate Decisions in the Leo Frank Case|publisher=University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law|access-date=October 1, 2016|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170114072547/http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/frank/frankappeals.html|archive-date=January 14, 2017|df=mdy-all}}</ref>|group=n}} On August 25, 1913, after less than four hours of deliberation, the jury reached a unanimous guilty verdict convicting Frank of murder.{{refn|The Atlanta ''Journal'' reported the next day that deliberation took less than two hours; at the first ballot one juror was undecided, but within two hours, the second vote was unanimous.<ref name="Lawson 407">Lawson p. 407.</ref>|group=n}} | |||

| The ''Constitution'' described the scene as Dorsey emerged from the steps of city hall: "hree muscular men swung Mr. Dorsey ... on their shoulders and passed him over the heads of the crowd across the street to his office. With hat raised and tears coursing down his cheeks, the victor in Georgia's most noted criminal battle was tumbled over a shrieking throng that wildly proclaimed its admiration."<ref>https://archive.org/details/sim_new-york-times_1914-12-14_64_20778/page/n3 "Finds Mob Frenzy Convicted Frank."] ''The New York Times'', December 14, 1914. p. 4. Via ].</ref> | |||

| On August 26, the day after the guilty verdict was reached by the jury, Judge Roan brought counsel into private chambers and sentenced Frank to death by hanging, with the date set to October 10. The defense team issued a public protest, alleging that public opinion unconsciously influenced the jury to the prejudice of Frank.<ref>Lawson p. 409.</ref> This argument was carried forward throughout the appeal process.<ref>Oney pp. 352–353.</ref> | |||

| ==Appeals and commutation== | |||

| ==Appeals== | |||

| ] printed sensationalistic coverage of the trial. Later, during the appeal process, he warned in the ''Jeffersonian'': "If Frank's rich connections keep on lying about this case, SOMETHING BAD WILL HAPPEN."<ref name="Woodward 1963, p. 439">Woodward 1963, p. 439.</ref>]] | |||