| Revision as of 21:37, 6 June 2015 editBrandywine589 (talk | contribs)90 edits →Theories about the loss← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:23, 19 December 2024 edit undoYeti-Hunter (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users504 editsm added authority control | ||

| (634 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Skipjack-class nuclear-powered submarine}} | |||

| {{Other ships|USS Scorpion}} | {{Other ships|USS Scorpion}} | ||

| {{Use American English|date=August 2015}} | |||

| {|{{Infobox ship begin}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2022}} | |||

| {|{{Infobox ship begin | |||

| | infobox caption = yes | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox ship image | {{Infobox ship image | ||

| |Ship image= |

| Ship image = Uss scorpion SSN589.jpg | ||

| |Ship caption=USS ''Scorpion'' 22 August 1960 off ] |

| Ship caption = USS ''Scorpion'', 22 August 1960, off ] | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Infobox ship career | {{Infobox ship career | ||

| |Hide header= | | Hide header = | ||

| |Ship country= | | Ship country = United States | ||

| |Ship flag= {{USN flag|1960}} | | Ship flag = {{USN flag|1960}} | ||

| |Ship name= |

| Ship name = ''Scorpion'' | ||

| |Ship namesake= | | Ship namesake = | ||

| |Ship ordered= 31 January 1957 | | Ship ordered = 31 January 1957 | ||

| |Ship awarded= | | Ship awarded = | ||

| |Ship builder=] | | Ship builder = ] | ||

| |Ship original cost= | | Ship original cost = | ||

| |Ship laid down=20 August 1958<ref name="Navy">{{cite web |

| Ship laid down = 20 August 1958<ref name="Navy">{{cite web |url=http://www.csp.navy.mil/othboats/589.htm |title=USS Scorpion (SSN 589) May 27, 1968 – 99 Men Lost |date=2007 |publisher=] |access-date=9 April 2008 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080312204810/http://www.csp.navy.mil/othboats/589.htm |archive-date=12 March 2008}}</ref> | ||

| |Ship launched= 29 December 1959<ref name="Navy"/> | | Ship launched = 29 December 1959<ref name="Navy" /> | ||

| |Ship sponsor= | | Ship sponsor = | ||

| |Ship christened= | | Ship christened = | ||

| |Ship completed= | | Ship completed = | ||

| | Ship commissioned = 29 July 1960<ref name="Navy" /> | |||

| |Ship acquired= | |||

| |Ship |

| Ship struck = 30 June 1968<ref name="Navy" /> | ||

| |Ship |

| Ship homeport = | ||

| |Ship |

| Ship identification = | ||

| |Ship |

| Ship motto = | ||

| | Ship nickname = USS Scrapiron<ref></ref> | |||

| |Ship out of service= | |||

| |Ship |

| Ship honors = | ||

| | Ship fate = Lost with all 99 crew on 22 May 1968; cause of sinking unknown | |||

| |Ship reclassified= | |||

| | Ship status = Located on the seabed of the Atlantic Ocean, {{coord|32|55|N|33|09|W|display=inline}},<ref>CINCLANTFLEET History Log June 1968 to July 1969, page 104 at 4. a.</ref> in {{convert|3000|m|abbr=on}} of water, {{convert|740|km|nmi|abbr=on}} southwest of the ] | |||

| |Ship refit= | |||

| | Ship notes = | |||

| |Ship struck=30 June 1968<ref name="Navy"/> | |||

| | Ship badge = ] | |||

| |Ship homeport= | |||

| |Ship identification= | |||

| |Ship motto= | |||

| |Ship nickname= | |||

| |Ship honors= | |||

| |Ship fate=Sank on 22 May 1968; cause of sinking unknown. All 99 on board killed. | |||

| |Ship status=Located on the seabed of the Atlantic Ocean, {{coord|32|54.9|N|33|08.89|W|display=inline}},<ref>CINCLANTFLEET History Log June 1968 to July 1969, page 104 at 4. a.</ref> in {{convert|3000|m|abbr=on}} of water, {{convert|740|km|nmi|abbr=on}} southwest of the ] | |||

| |Ship notes= | |||

| |Ship badge=] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Infobox ship characteristics | {{Infobox ship characteristics | ||

| |Hide header= | | Hide header = | ||

| |Header caption= | | Header caption = | ||

| |Ship class={{ |

| Ship class = {{sclass|Skipjack|submarine}} | ||

| |Ship displacement={{convert|2880|LT|t|abbr=on|lk=in}} light |

| Ship displacement = *{{convert|2880|LT|t|abbr=on|lk=in}} light | ||

| * {{convert|3075|LT|t|0|abbr=on}} full | |||

| * {{convert|195|LT|t|0|abbr=on}} ] | |||

| |Ship length={{convert| |

| Ship length = {{convert|251|ft|8|in|m|abbr=on}} | ||

| |Ship beam={{convert| |

| Ship beam = {{convert|31|ft|7.75|in|m|abbr=on}} | ||

| |Ship height= | | Ship height = | ||

| |Ship draft={{convert|9.1|m|ftin|abbr=on}} | | Ship draft = {{convert|9.1|m|ftin|abbr=on}} | ||

| |Ship depth= | | Ship depth = | ||

| |Ship propulsion=] | | Ship propulsion = ] | ||

| |Ship speed= | | Ship speed = | ||

| |Ship range= | | Ship range = | ||

| |Ship endurance= | | Ship endurance = | ||

| |Ship test depth= | | Ship test depth = | ||

| |Ship capacity= | | Ship capacity = | ||

| |Ship complement=8 officers, 75 |

| Ship complement = 8 officers, 75 enlisted | ||

| |Ship sensors= | | Ship sensors = | ||

| |Ship EW= | | Ship EW = | ||

| |Ship armament=6 × {{convert|21|in|mm|abbr=on|0}} torpedo tubes |

| Ship armament = *6 × {{convert|21|in|mm|abbr=on|0}} torpedo tubes | ||

| * 2 × ]es | |||

| |Ship notes= | | Ship notes = | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| |} | |} | ||

| '''USS ''Scorpion'' (SSN-589)''' was a ] nuclear-powered submarine that served in the ], the sixth vessel and second submarine to carry that name. | |||

| '''USS ''Scorpion'' (SSN-589)''' was a ] nuclear ] of the ] and the sixth vessel of the U.S. Navy to carry that name. ''Scorpion'' was lost on 22 May 1968, with 99 crewmen dying in the incident. The USS ''Scorpion'' is one of two nuclear submarines the U.S. Navy has lost, the other being {{USS|Thresher|SSN-593|6}}.<ref>{{cite book|first1=Sherry|last1=Sontag|first2=Christopher|last2=Drew|title=]|location=]|publisher=]|year=2000|page=432}}</ref> It was one of four mysterious submarine disappearances in 1968; the others being the Israeli submarine ], the ] and the ]. | |||

| ''Scorpion'' sank on 27 May 1968. She is one of two nuclear submarines that the U.S. Navy has lost, the other being {{USS|Thresher|SSN-593|6}}.{{sfnp|Sontag|Drew|2000|p=432}} She was one of the four submarine disappearances in 1968, the others being the Israeli submarine {{Ship|INS|Dakar}}, the {{Ship|French submarine|Minerve|S647|6}}, and the {{Ship|Soviet submarine|K-129|1960|6}}. | |||

| ==Service== | |||

| ''Scorpion''{{'}}s keel was laid down 20 August 1958 by ] in ]. She was ] 19 December 1959, sponsored by Mrs. Elizabeth S. Morrison, the daughter of the last commander of the ]-era {{USS|Scorpion|SS-278|6}} (which was also lost with all hands, in 1944). ''Scorpion'' was ] 29 July 1960, Commander Norman B. Bessac in command. | |||

| The wreckage of the ''Scorpion'' remains in the North Atlantic Ocean with all its armaments and nuclear reactor. | |||

| ===Service: 1960–1967=== | |||

| Assigned to Submarine Squadron 6, Division 62, ''Scorpion'' departed ], 24 August for a two-month European deployment. During that time, she participated in exercises with ] units and ]-member navies. After returning to ] in late October, she trained along the eastern seaboard until May 1961. On 9 August 1961, she returned to New London, moving to ], a month later. In 1962, she earned a ]. | |||

| == Service == | |||

| Norfolk was ''Scorpion''{{'}}s port for the remainder of her career, and she specialized in developing nuclear ] tactics. Varying roles from hunter to hunted, she participated in exercises along the Atlantic coast, ], and ] operating areas. From June 1963 to May 1964, she interrupted operations for an ] at ]. She resumed duty in late spring, but was again interrupted from 4 August to 8 October for a transatlantic patrol. In the spring of 1965, she conducted a similar patrol in European waters. | |||

| ] | |||

| ''Scorpion''{{'}}s keel was laid down 20 August 1958 by ] in ]. She was ] 19 December 1959, sponsored by Elizabeth S. Morrison, the daughter of the last commander of the ]-era {{USS|Scorpion|SS-278}}, Lt. Cdr. Maximilian Gmelich Schmidt (that ship was also lost with all hands, in 1944). ''Scorpion'' was ] 29 July 1960, with Commander Norman B. Bessac in command.<ref name=DANFS>{{cite DANFS |title= Scorpion VI (SSN-589) |url= http://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/s/scorpion-ssn-589-vi.html}}</ref> {{Efn|See ] for information on how that submarine had originally been laid down with the name and hull number, USS ''Scorpion'' ], intended to be an attack submarine.}} | |||

| === Service: 1960–1967 === | |||

| During late winter, early spring, and autumn of 1966, she deployed for special operations. After completing those assignments, her commanding officer (CO) received a ] for outstanding leadership, foresight, and professional skill. Other ''Scorpion'' officers and crewmen were also cited for meritorious achievement. ''Scorpion'' is reputed to have entered an inland Russian sea during a "Northern Run" in 1966, where it filmed a Soviet missile launch through its periscope before fleeing from Soviet Navy ships. | |||

| Assigned to Submarine Squadron 6, Division 62, ''Scorpion'' departed ], on 24 August for a two-month European deployment. During that time, she participated in exercises with ] units and ]-member navies. After returning to ] in late October, she trained along the Eastern Seaboard until May 1961. On 9 August 1961, she returned to New London, moving to ], a month later.<ref name=DANFS /> In 1962, she earned a ].<ref></ref> | |||

| Norfolk was ''Scorpion''{{'}}s homeport for the remainder of her career, and she specialized in developing nuclear ] tactics. Varying roles from hunter to hunted, she participated in exercises along the Atlantic Coast, and in ] and ] operating areas. From June 1963 to May 1964, she underwent an ] at ]. She resumed duty in late spring, but regular duties were again interrupted from 4 August to 8 October for a transatlantic patrol. In the spring of 1965, she conducted a similar patrol in European waters.{{citation needed|date=August 2019}} | |||

| ===Overhaul: 1967=== | |||

| On 1 February 1967, ''Scorpion'' entered ] for another extended overhaul. However, instead of a much-needed complete overhaul, she received only emergency repairs to get quickly back on duty. The preferred ]<ref></ref><ref></ref> program required increased submarine overhaul times, from nine months in length to 36 months. Intensive vetting of submarine component quality SUBSAFE was required, coupled with various improvements and intensified structural inspections — particularly, hull-welding inspections using ultrasonic testing — and reduced availability of critical parts like seawater piping. Cold War pressures prompted U.S. Submarine Force Atlantic (]) officers to hunt for ways to cut corners; the last overhaul cost only one-seventh of those given other nuclear submarines at the same time. This was the result of concerns about the "high percentage of time offline" for nuclear attack submarines, estimated at about 40% of total available duty time. | |||

| In 1966, she deployed for special operations. After completing those assignments, her commanding officer received a ] for outstanding leadership, foresight, and professional skill. Other ''Scorpion'' officers and crewmen were also cited for meritorious achievement.<ref name=DANFS /> ''Scorpion'' is reputed to have entered an inland Russian sea during a "Northern Run" in 1966, where the crew filmed a Soviet missile launch through her periscope before fleeing from Soviet Navy ships.{{citation needed|date=August 2019}} | |||

| ''Scorpion''{{'}}s original "full overhaul" was reduced in scope; long-overdue SUBSAFE work, such as a new central valve control system, was not performed. Crucially, her emergency system was not corrected for the same problems that destroyed ''Thresher''. While Charleston Naval Ship Yard claimed the Emergency Main Ballast Tank Blow (EMBT) system worked as-is, SUBLANT claimed it did not and their EMBT was "tagged out" or listed as unusable. Perceived problems with overhaul duration led to a delay on all SUBSAFE work in 1967. | |||

| === Overhaul: 1967 === | |||

| ] Admiral David Lamar McDonald approved ''Scorpion''{{'}}s reduced overhaul on 17 June 1966. On 20 July, McDonald deferred ] extensions, otherwise deemed essential until 1963. | |||

| On 1 February 1967, ''Scorpion'' entered ] for a refueling overhaul. Instead of a much-needed complete overhaul, though, she received only emergency repairs to get quickly back on duty. The preferred ]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.gdeb.com/suppliers/10_quality/SQ_Qual_Conf_2008/1-2%2520Supplier%2520Training%2520-%2520SUBSAFE%2520ProgramRev1.ppt |title=''Submarine Safety Program'' (SUBSAFE) |website=Electric Boat Corporation |access-date=23 February 2019 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150528155633/http://www.gdeb.com/suppliers/10_quality/SQ_Qual_Conf_2008/1-2%20Supplier%20Training%20-%20SUBSAFE%20ProgramRev1.ppt |archive-date=28 May 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.navsea.navy.mil/NAVINST/04855-034A.pdf |title=Procedures for Qualification and Authorization of Activities to Perform SUBSAFE Work |date=6 November 2006 |website=] |access-date=23 February 2019 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130228150132/http://www.navsea.navy.mil/NAVINST/04855-034A.pdf |archive-date=28 February 2013}}</ref> program required increased submarine overhaul times, from 9 to 36 months. SUBSAFE required intensive vetting of submarine component quality, coupled with various improvements and intensified structural inspections – particularly of hull welding, using ultrasonic testing. | |||

| <!-- On December 1968, the pentagon told related that Scorpion was due to another overhaul in 1969. --> | |||

| Cold War pressures had prompted U.S. Submarine Force Atlantic (]) officers to cut corners. The last overhaul of the ''Scorpion'' cost one-seventh of those performed on other nuclear submarines at the same time. This was the result of concerns about the "high percentage of time offline" for nuclear attack submarines, estimated at 40% of total available duty time.{{citation needed|date=August 2019}} | |||

| ===Service: 1967–1968=== | |||

| ], ], in April 1968 (shortly before ''Scorpion'' departed on her last voyage). This is believed to be one of the last photographs taken of ''Scorpion''.]] | |||

| ''Scorpion''{{'}}s original "full overhaul" was reduced in scope. Long-overdue SUBSAFE work, such as a new central valve control system, was not performed. Crucially, her emergency system was not corrected for the same problems that destroyed ''Thresher''. While ] claimed the emergency main ballast tank blow (EMBT) system worked as-is, SUBLANT claimed it did not, and their EMBT was "tagged out" (listed as unusable). Perceived problems with overhaul duration led to a delay on all SUBSAFE work in 1967.{{citation needed|date=August 2019}} | |||

| In late October 1967, ''Scorpion'' started refresher training and weapons system acceptance tests, and was given a new commanding officer, ]. Following type training out of ], she got underway on 15 February 1968 for a ] deployment. She operated with the 6th Fleet into May and then headed west for home. ''Scorpion'' suffered several mechanical malfunctions including a chronic problem with ] leakage from refrigeration systems. An electrical fire occurred in an escape trunk when a water leak shorted out a shore power connection. (However, major steam and leakage problems are not uncommon on U.S. Navy or Royal Navy submarine deployments, even in the 21st Century.<ref>B. Farmer. Defence Correspondent. Daily Telegraph,4 June 2014 "People were going to die ... Catastrophic systems failure" on HMS ''Turbulent'' in Med, 2011</ref>) There is no evidence that the Scorpion's speed was restricted in May 1968, although it was conservatively observing a depth limitation of 500 feet, due to the incomplete implementation of planned post-''Thresher'' safety checks and modifications.<ref>K. Sewell & J. Preisler. ''All Hands Down. The true story of Soviet Attack on the USS Scorpion''. Simon & Schulster. NY (2008)</ref> | |||

| ] Admiral ] approved ''Scorpion''{{'}}s reduced overhaul on 17 June 1966. On 20 July, McDonald deferred SUBSAFE extensions, otherwise deemed essential since 1963.{{verify source|date=December 2015}} | |||

| Departing the Mediterranean on 16 May, two men left ''Scorpion'' at ] in Spain, one for a family emergency (RM2 Eric Reid) and the other (IC1 Joseph Underwood) was dispatched for health reasons. Some U.S. ]s (SSBN) operated from the U.S. Naval base at Rota and it is speculated that USS ''Scorpion'' provided noise cover for {{USS|John C. Calhoun|SSBN-630}} as they both ran out to the Atlantic and that, as usual, there were Soviet fast nuclear attack submarines (SSN) attempting to detect and follow the U.S. SSBN; in this case two fast 32 knot Soviet November class hunter-killers.<ref>K. Sewell & J.Preisler. ''All hands down. Attack on USS Scorpion''. Simon & Schulster (NY)08</ref> ''Scorpion'' was then detailed to observe Soviet naval activities in the Atlantic in the vicinity of the Azores. An Echo II class submarine was operating with this Soviet task force, as well as a Russian guided missile destroyer.<ref>Bradley, M. A. Why they called the Scorpion "Scapiron ,'Proceedings July 1998' U.S. Naval Institute. Annapolis, vol124 7/1/1,145.</ref> Having observed and listened to the Soviet units, ''Scorpion'' prepared to head back to Naval Station Norfolk. | |||

| <!-- In December 1968, the Pentagon stated that Scorpion was due another overhaul in 1969. --> | |||

| === Service: 1967–1968 === | |||

| ==Disappearance: May 1968== | |||

| ], ], Italy, in April 1968 (shortly before ''Scorpion'' departed on her last voyage). This is one of the last photographs taken of ''Scorpion'' before her loss.]] | |||

| For an unusually long period of time, beginning shortly before midnight on 20 May and ending after midnight 21 May, ''Scorpion'' attempted to send radio traffic to Naval Station Rota, but was only able to reach a Navy communications station in ], Greece, which forwarded ''Scorpion''{{'}}s messages to ].<ref>K. Sewell & J Preisler. All Hands Down. The True Story of the Soviet Attack on USS Scorpion.Simon & Schuster NY(2008)</ref> Lt John Roberts was handed Commander Slattery's last message, that he was closing on the Soviet submarine and research group, running at a steady 15 knots at 350 feet "to begin surveillance of the Soviets".<ref>K. Sewell & J. Preisler. All Hands Down. The True Story of the Soviet Attack on USS Scorpion. Simon & Schuster. Ny (2008) ,</ref> Six days later the media reported she was overdue at Norfolk.<ref name=baltimore93>{{Cite web | title = After 25 years of loss, families resent Navy's silence about sub | work = Baltimore Sun | accessdate = 2014-01-07 | date = 1993-11-21 | url = http://articles.baltimoresun.com/1993-11-21/news/1993325004_1_scorpion-related-to-mrs-cold-war}}</ref> | |||

| In late October 1967, ''Scorpion'' started refresher training and weapons-system acceptance tests, and was given a new commanding officer, Francis Slattery. Following type training out of Norfolk, Virginia, she got underway on 15 February 1968 for a Mediterranean Sea deployment. She operated with the 6th Fleet into May and then headed west for home.<ref name=DANFS /> | |||

| ===Search: 1968=== | |||

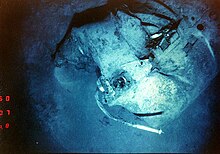

| ] ]]] | |||

| ''Scorpion'' suffered several mechanical malfunctions, including a chronic problem with ] leakage from refrigeration systems. An electrical fire occurred in an escape trunk when a water leak shorted out a shore power connection. No evidence was found that ''Scorpion''{{'}}s speed was restricted in May 1968, although it was conservatively observing a depth limitation of {{convert|500|ft|m}}, due to the incomplete implementation of planned post-''Thresher'' safety checks and modifications.{{sfnp|Sewell|Preisler|2008}} | |||

| The Navy suspected possible failure and launched a public search. ''Scorpion'' and her crew were declared "presumed lost" on 5 June. Her name was struck from the ] on 30 June. The public search continued with a team of mathematical consultants led by Dr. ], the Chief Scientist of the U.S. Navy's Special Projects Division. They employed the methods of ], initially developed during the search for a hydrogen bomb lost off the coast of Palomares, Spain, in January 1966 in the ]. | |||

| After departing the Mediterranean on 16 May, ''Scorpion'' dropped two men at ] in Spain, one for a family emergency and one for health reasons. Some U.S. ]s (SSBNs) operated from the U.S. Naval base Rota; USS ''Scorpion'' is thought to have provided noise cover for {{USS|John C. Calhoun|SSBN-630|6}} when they both departed to the Atlantic. Along with Soviet intelligence trawlers, Soviet fast nuclear attack submarines{{sfnp|Offley|2007}} were attempting to detect and follow the U.S. submarines going out of Rota, in this case, two fast 32-knot Soviet {{sclass2|November|submarine|0}} hunter-killer subs.{{sfnp|Sewell|Preisler|2008}} | |||

| Some reports indicate that a large and secret search was launched three days before ''Scorpion'' was expected back from patrol. This, combined with other declassified information, leads to speculation that the U.S. Navy knew of the ''Scorpion''{{'}}s destruction before the public search was launched.<ref>{{cite book|first=Ed|last=Offley|title=Scorpion Down: Sunk by the Soviets, Buried by the Pentagon: The Untold Story of the USS Scorpion|location=New York|publisher=]|year=2007|pages=241 ''ff.''|isbn=978-0-465-00884-1}}</ref> | |||

| ''Scorpion'' was then detailed to observe Soviet naval activities in the Atlantic in the vicinity of the Azores. An ] was operating with this Soviet task force, as well as a Russian guided-missile destroyer.<ref>{{cite journal |url=https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1998-07/why-they-called-scorpion-scrapiron |title=Why they called the Scorpion 'Scrapiron' |last=Bradley |first=Mark A. |date=July 1998 |journal=] |publisher=] |location=] |volume=124 |pages=30–38 |url-access=subscription }}</ref> Having observed and listened to the Soviet units, ''Scorpion'' prepared to head back to Naval Station Norfolk.{{citation needed|date=August 2019}} | |||

| At the end of October 1968, the Navy's oceanographic research ship, {{USNS|Mizar|AGOR-11|2}}, located sections of the hull of ''Scorpion'' on the seabed, about {{convert|740|km|nmi mi|abbr=on}} southwest of the ],<ref name=pshow> ''Popular Science'', April 1969, pp. 66–71.</ref> under more than {{convert|3000|m|ft|abbr=on}} of water. This was after the Navy had released sound tapes from its underwater "]" listening system, which contained the sounds of the destruction of ''Scorpion''. The court of inquiry was subsequently reconvened and other vessels, including the ] ], were dispatched to the scene, collecting many pictures and other data. | |||

| == Disappearance: May 1968 == | |||

| Although Craven received much credit for locating the wreckage of ''Scorpion'', Gordon Hamilton, an acoustics expert who pioneered the use of ] to pinpoint Polaris missile splashdown locations, was instrumental in defining a compact "search box" wherein the wreck was ultimately found. Hamilton had established a listening station in the Canary Islands that obtained a clear signal of what some scientists believe was the noise of the vessel's pressure hull imploding as she passed ]. A ] scientist named Chester "Buck" Buchanan, using a towed camera sled of his own design aboard ''Mizar'', finally located ''Scorpion''.<ref name=pshow/> The towed camera sled, which was fabricated by J. L. "Jac" Hamm of Naval Research Laboratory's Engineering Services Division, is housed in the ]. Buchanan had located the wrecked hull of ] in 1964 using this technique. | |||

| ''Scorpion'' attempted to send radio traffic to Naval Station Rota for an unusually long period beginning shortly before midnight on 20 May and ending after midnight on 21 May, but was only able to reach a Navy communications station in ], Greece, which forwarded the messages to ].{{sfnp|Sewell|Preisler|2008}} Lt. John Roberts was handed Commander Slattery's last message that he was closing on the Soviet submarine and research group, running at a steady {{cvt|15|kn|km/h mph||}} at a depth of {{cvt|350|ft|}} "to begin surveillance of the Soviets."{{sfnp|Sewell|Preisler|2008}} ''Scorpion ''was expected to arrive at her homeport of Norfolk, Virginia, on 27 May at 1300 local time. After she was overdue for several hours, the Atlantic fleet launched a sea and air search during the peak search period from 28 to 30 May involving as many as 55 ships and 35 search aircraft. A brief radio message including ''Scorpion's'' codename ''Brandywine'' was received by several search parties on the evening of 29 May. The source could not be identified in the search area derived from the bearings of the radio message.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.secnav.navy.mil/foia/readingroom/CaseFiles/Scorpion%20Submarine/USS%20Scorpion%20search%20messages_FINAL.pdf |title=USS Scorpion search messages FINAL|access-date=2021-10-28 |date=3 June 1968|publisher=Department of Defence, CINTLANT}}</ref><ref name=baltimore93>{{Cite news |url=https://www.baltimoresun.com/1993/11/21/after-25-years-of-loss-families-resent-navys-silence-about-sub/ |title=After 25 years of loss, families resent Navy's silence about sub |first=Tom |last=Keyser |date=21 November 1993 |newspaper=] |access-date=7 January 2014 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141214015649/http://articles.baltimoresun.com/1993-11-21/news/1993325004_1_scorpion-related-to-mrs-cold-war |archive-date=14 December 2014}}</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Search: 1968 === | ||

| ] ]]] | |||

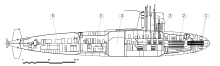

| [[File:Skipjack class submarine 3D drawing.svg||thumb|Skipjack class submarine drawing:<br />1. Sonar arrays<br /> | |||

| 2. Torpedo room<br />3. Operations compartment<br />4. Reactor compartment<br />5. Auxiliary machinery space<br />6. Engine room]] | |||

| It would appear that the bow of ''Scorpion'' skidded upon impact with the ] on the sea floor, digging a sizable trench. The ] had been dislodged as the ] of the operations compartment upon which it perched disintegrated, and was lying on its ]. One of ''Scorpion''{{'}}s running lights was in the open position, as if it had been on the surface at the time of the mishap, although it may have been left in the open position during the vessel's recent nighttime stop at Rota. One ''Trieste II'' pilot who dived on ''Scorpion'' said the shock of the implosion may have knocked the light into the open position. | |||

| The Navy suspected possible failure and launched a search, but ''Scorpion'' and her crew were declared "presumed lost" on 5 June. Her name was struck from the ] on 30 June. The search continued with a team of mathematical consultants led by ], the chief scientist of the Navy's Special Projects Division. They employed the methods of ], initially developed during the search for a hydrogen bomb lost off the coast of Palomares, Spain, in January 1966 in the ].<ref name="mcgrayne">{{cite book |last1=McGrayne |first1=Sharon Bertsch |title=The Theory That Would Not Die: How Bayes' Rule Cracked the Enigma Code, Hunted Down Russian Submarines & Emerged Triumphant from Two Centuries of Controversy |pages=97– | date=2011 |publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=978-0-300-18822-6 }}</ref> | |||

| The secondary Navy investigation — using extensive photographic, video, and eyewitness inspections of the wreckage in 1969 — offered the opinion that ''Scorpion''{{'}}s hull was crushed by implosion forces as it sank below crush depth. The Structural Analysis Group, which included ]'s Submarine Structures director ], plainly saw that the torpedo room was intact, though it had been pinched from the operations compartment by massive hydrostatic pressure. The operations compartment was largely obliterated by sea pressure and the engine room had telescoped {{convert|50|ft|m|abbr=on}} forward into the hull by collapse pressure, when the cone-to-cylinder transition junction failed between the auxiliary machine space and the engine room. | |||

| Some reports indicate that a large and secret search was launched three days before ''Scorpion'' was expected back from patrol. This and other declassified information led to speculation that the Navy knew of ''Scorpion''{{'}}s destruction before the public search was launched.{{sfnp|Offley|2007|pp=241–}} | |||

| The only damage to the torpedo room compartment appeared to be a hatch missing from the forward escape trunk. Palermo pointed out that this would have occurred when water pressure entered the torpedo room at the moment of implosion. | |||

| <!-- '''That doesn't belong here:''' | |||

| He also pointed out that the aft escape trunk hatch was open and the fairing was slightly dislodged, though it was still on its hinges. This conclusion was drawn by Palermo eighteen years after ''Scorpion'' was lost, when he reviewed new images taken by '']'' and ] as part of a Navy-] survey of ''Scorpion''{{'}}s wreck site. | |||

| At the end of October 1968, the Navy's oceanographic research ship {{USNS|Mizar|AGOR-11|2}} located sections of the hull of ''Scorpion'' on the seabed, about {{convert|400|nmi|km|abbr=on|}} southwest of the ]<ref name=pshow>{{cite magazine |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EyoDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA66 |title=Strange Devices That Found the Sunken Sub Scorpion |magazine=] |date=April 1969 |publisher=Bonnier Corporation |pages=66–71 |issn=0161-7370 |access-date=23 February 2019}}</ref> under more than {{convert|3000|m|ft|abbr=on||order=flip}} of water. This was after the Navy had released sound tapes from its underwater ] listening system, which contained the sounds of the destruction of ''Scorpion''.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/1968-us-nuclear-submarine-went-russia-super-secret-spy-18379|title=In 1968, A US Nuclear Submarine Went On a Russia Super Secret Spy Mission (And It Never Came Back)|last=Mizokami|first=Kyle|date=2016-11-13|website=The National Interest|language=en|access-date=2019-07-23}}</ref> The court of inquiry was subsequently reconvened, and other vessels, including the ] ], were dispatched to the scene to collect pictures and other data. | |||

| Palermo could not rule out sabotage or collision as "plausible" causes of destruction. Palermo writes that the position of the masts and other evidence possibly indicate ''Scorpion'' was near the surface "just prior to sinking." However, other analysis in the COI concludes the damage to masts, antennas, and hoists is mere consequential damage from detachment of the sail and parting of the hydraulic piping. Palermo admits that a precursor signal that occurred some 22 minutes prior to the acoustic train left by the sinking "could have been the results of an internal explosion." He further states that "some of the remaining 14 acoustic events do have some of the characteristics of explosions," though he qualifies this by writing that such characteristics "may" also be attributed to other sources. | |||

| Craven received much credit for locating the wreckage of ''Scorpion'', although Gordon Hamilton was instrumental in defining a compact "search box" wherein the wreck was ultimately found. He was an acoustics expert who pioneered the use of ] to pinpoint Polaris missile splashdown locations, and he had established a listening station in the Canary Islands, which obtained a clear signal of the vessel's pressure hull imploding as it passed ]. Naval Research Laboratory scientist Chester Buchanan used a towed camera sled of his own design aboard ''Mizar'' and finally located ''Scorpion''.<ref name="pshow" /> | |||

| The submersible ''Alvin'' did take pictures of the inboard end of the propulsion shaft in 1986. However, the Navy kept this classified for many years and only recently revealed its existence. The picture shows that the locking lip has gone. This lip was required to keep the shaft connected to the drive train in the bolted coupling. Cracking or shear of this lip is the root cause of the detachment of the shaft. --> | |||

| === Observed damage === | |||

| ==Navy investigations== | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=September 2016}} | |||

| ===Court of Inquiry report — 1968=== | |||

| [[File:Skipjack class submarine 3D drawing.svg|thumb|Skipjack-class submarine drawing:<br />1. Sonar arrays<br /> | |||

| Shortly after her sinking, the Navy assembled a ] to investigate the incident and to publish a report about the likely causes for the sinking. The court was presided over by Vice Admiral ], who had presided over the inquiry into the loss of '']''. The panel's conclusions, first printed in 1968,{{citation needed|date=January 2014}}<!--Is it?--> were largely classified. At the time, the Navy quoted frequently{{citation needed|date=January 2014}} from a portion of the 1968 report that said no one is likely ever to "conclusively" determine the cause of the loss. | |||

| 2. Torpedo room<br />3. Operations compartment<br />4. Reactor compartment<br />5. Auxiliary machinery space<br />6. Engine room]] | |||

| The bow of ''Scorpion'' appears to have skidded upon impact with the ] on the sea floor, digging a sizable trench. The ] had been dislodged, as the ] of the operations compartment upon which it perched disintegrated, and was lying on its ]. One of ''Scorpion''{{'}}s running lights was in the open position, as if it had been on the surface at the time of the mishap, although it may have been left in the open position during the vessel's recent nighttime stop at Rota. One ''Trieste II'' pilot who dived on ''Scorpion'' said that the shock of the ] might have knocked the light into the open position. | |||

| The secondary Navy investigation – using extensive photographic, video, and eyewitness inspections of the wreckage in 1969 – suggested that ''Scorpion''{{'}}s hull was crushed by implosion forces as it sank below crush depth. The Structural Analysis Group, which included ]'s Submarine Structures director ], plainly saw that the torpedo room was intact, though it had been pinched by excessive sea pressure. The operations compartment collapsed at frame 33, this being the king frame of the hull, reaching its structural limit first. The conical/cylindrical transition piece at frame 67 followed instantly. The boat was broken in two by massive ] pressure at an estimated depth of {{convert|1530|ft|m|abbr=on}}. The operations compartment was largely obliterated by sea pressure, and the engine room had telescoped {{convert|50|ft|m|abbr=on}} forward into the hull due to collapse pressure, when the cone-to-cylinder transition junction failed between the auxiliary machine space and the engine room. | |||

| The ] declassified most of this report in 1993, and it was then that the public first learned that the panel considered that a possible cause was the malfunction of one of ''Scorpion''{{'}}s own ]es. | |||

| The only damage to the torpedo room compartment appeared to be a hatch missing from the forward escape trunk. Palermo pointed out that this would have occurred when water pressure entered the torpedo room at the moment of implosion. | |||

| ===Naval Ordnance Laboratory report — 1970=== | |||

| An extensive, year-long analysis of Gordon Hamilton's hydroacoustic signals of the submarine's demise was conducted by Robert Price, Ermine (Meri) Christian and Peter Sherman of the ] (NOL). All three physicists were experts on undersea explosions, their sound signatures, and their destructive effects. Price was also an open critic of Craven. Their opinion, presented to the Navy as part of the Phase II investigation, was that the death noises likely occurred at {{convert|2000|ft|m|abbr=on}} when the hull failed. Fragments then continued in a free fall for another {{convert|9000|ft|m|abbr=on}}. This appears to differ from conclusions drawn by Craven and Hamilton, who pursued an independent set of experiments as part of the same Phase II probe, demonstrating that alternate interpretations of the hydroacoustic signals were possibly based on the submarine's depth at the time it was stricken and other operational conditions. | |||

| The sail was ripped off, as the hull beneath it folded inward. The propulsion shaft came out of the boat; the engineering section had collapsed inward in a telescoping fashion. The broken boat fell another {{convert|9000|ft|m|abbr=on}} to the ocean floor. | |||

| The Structural Analysis Group (SAG) concluded that an explosive event was unlikely, and was highly dismissive of Craven and Hamilton's tests. The SAG physicists argued that the absence of a bubble pulse, which invariably occurs in an underwater explosion, is absolute evidence that no torpedo explosion occurred outside or inside the hull. Craven had attempted to prove ''Scorpion''{{'}}s hull could "swallow" the bubble pulse of a torpedo detonation by having Gordon Hamilton detonate small charges next to steel, air-filled containers. | |||

| Photos taken in 1986 by ] released by the Navy in 2012, show the broken inboard end of the propulsion shaft. | |||

| The 1970 Naval Ordnance Laboratory "Letter",<ref name=2013MFScorpion>{{cite web|last1=Potts|first1=JR|title=Our continuation of the USS Scorpion (SSN-589) Nuclear Attack Submarine story|url=http://www.militaryfactory.com/ships/detail-page-2.asp?ship_id=USS-Scorpion-SSN589|website=www.militaryfactory.com|accessdate=17 August 2014}}</ref> the acoustics study of ''Scorpion'' destruction sounds by Price and Christian, was a supporting study within the SAG report. In its conclusions and recommendations section, the NOL acoustic study states: "The first SCORPION acoustic event was not caused by a large explosion, either internal or external to the hull. The probable depth of occurrence ... and the spectral characteristics of the signal support this. In fact, it is unlikely that any of the Scorpion acoustic events were caused by explosions."<ref name=2013MFScorpion/> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| <!-- '''That doesn't belong here:''' | |||

| He also pointed out that the aft escape trunk hatch was open and the fairing was slightly dislodged, though it was still on its hinges. This conclusion was drawn by Palermo eighteen years after ''Scorpion'' was lost, when he reviewed new images taken by '']'' and ] as part of a Navy-] survey of ''Scorpion''{{'}}s wreck site. | |||

| Palermo could not rule out sabotage or collision as "plausible" causes of destruction. He writes that the position of the masts and other evidence possibly indicate ''Scorpion'' was near the surface "just prior to sinking". However, other analysis in the COI concludes the damage to masts, antennas and hoists is mere consequential damage from detachment of the sail and parting of the hydraulic piping. Palermo admits that a precursor signal that occurred some 22 minutes prior to the acoustic train left by the sinking "could have been the results of an internal explosion". He further states that "some of the remaining 14 acoustic events do have some of the characteristics of explosions", though he qualifies this by writing that such characteristics "may" also be attributed to other sources. | |||

| The Naval Ordnance Laboratory based much of its findings on an extensive acoustic analysis of the torpedoing and sinking of {{USS|Sterlet|SS-392|2}} in the Pacific in early 1969, seeking to compare its acoustic signals to those generated by ''Scorpion''. Price found the Navy's scheduled sinking of ''Sterlet'' fortuitous. Nonetheless, ''Sterlet'' was a small World War II-era Diesel-electric submarine of a vastly different design and construction than ''Scorpion'' with regard to its pressure hull and other characteristics. Its sinking resulted in three identifiable acoustic signals as compared to ''Scorpion''{{'}}s 15. The mathematical calculations Price used remain unknown to the public.<ref name=2013MFScorpion/> In addition, the NOL based its findings on the data recorded by the Canary Island hydro acoustic facility, and that data may have been "cleansed" of the initial (bubble pulse) signature from an external torpedo explosion before release.<ref>13</ref> | |||

| The submersible ''Alvin'' did take pictures of the inboard end of the propulsion shaft in 1986. However, the Navy kept this classified for many years and only recently revealed its existence. The picture shows that the locking lip has gone. This lip was required to keep the shaft connected to the drive train in the bolted coupling. Cracking or shear of this lip is the root cause of the detachment of the shaft. --> | |||

| The NOL acoustics study provided a highly debated explanation as to how ''Scorpion'' may have reached its crush depth by anecdotally referring to the near-loss incident of the Diesel submarine {{USS|Chopper|SS-342|2}} in January 1969, when a power problem caused her to sink almost to crush depth, before surfacing. | |||

| == Navy investigations == | |||

| In the same May 2003 N77 letter excerpted above (see 1. with regard to the Navy's view of a forward explosion), however, the following statement appears to dismiss the NOL theory, and again unequivocally point the finger toward an explosion forward: | |||

| === Court of inquiry report: 1968 === | |||

| {{quote|The Navy has extensively investigated the loss of ''Scorpion'' through the initial court of inquiry and the 1970 and 1987 reviews by the Structural Analysis Group. Nothing in those investigations caused the Navy to change its conclusion that an unexplained catastrophic event occurred.}} | |||

| Shortly after her sinking, the Navy assembled a ] to investigate the incident and to publish a report regarding the likely causes for its loss. The court was presided over by Vice Admiral ], who had presided over the inquiry into the loss of {{USS|Thresher|SSN-593|2}}. The report's findings were first made public on 31 January 1969. While ruling out sabotage, the report said: "The certain cause of the loss of the ''Scorpion'' cannot be ascertained from evidence now available."<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1969/02/01/archives/loss-of-scorpion-baffles-inquiry-navy-rules-out-sabotage-in-subs.html |title=Loss of Scorpion Baffles Inquiry |date=1 February 1969 |newspaper=] |pages=1, 14}}</ref> | |||

| In 1984, the '']'' obtained documents related to the inquiry, and reported that the likely cause of the disaster was the detonation of a ] while the ''Scorpion''{{'}}s own crew attempted to disarm it.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1984/12/17/us/navy-indicates-cause-of-1968-sub-sinking.html |title=Navy Indicates Cause Of 1968 Sub Sinking |agency=] |date=17 December 1984 |newspaper=The New York Times |access-date=22 May 2017}}</ref> The U.S. Navy declassified many of the inquiry's documents in 1993.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://pilotonline.com/news/military/local/new-evidence-suggests-soviets-may-have-sunk-the-sub-scorpion/article_7f381586-7267-550e-895a-93b6335e2a93.html |title=New evidence suggests Soviets may have sunk the sub Scorpion 40 years ago |last=Wiltrout |first=Kate |date=18 May 2008 |work=The Virginian-Pilot |access-date=22 May 2017 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160521122948/http://pilotonline.com/news/military/local/new-evidence-suggests-soviets-may-have-sunk-the-sub-scorpion/article_7f381586-7267-550e-895a-93b6335e2a93.html |archive-date=21 May 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ===Environmental concerns=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Today, the wreck of ''Scorpion'' is reported to be resting on a sandy seabed at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean in approximately {{convert|3000|m|ft|abbr=on}} of water. The site is reported to be approximately {{convert|400|nmi|km|abbr=on}} southwest of the ], on the eastern edge of the ]. The actual position is 32°54.9'N, 33°08.89'W.<ref>Command History of the Commander in Chief U.S. Atlantic Fleet, OPNAV REPORT 5750-1, July 1968 – June 1969, p. 104 at 4. a.</ref> The U.S. Navy has acknowledged that it periodically visits the site to conduct testing for the release of nuclear materials from the nuclear reactor or the two nuclear weapons aboard her, and to determine whether the wreckage has been disturbed. The Navy has not released any information about the status of the wreckage, except for a few photographs taken of the wreckage in 1968, and again in 1985 by deep water submersibles. | |||

| === Naval Ordnance Laboratory report: 1970 === | |||

| The Navy has also released information about the nuclear testing performed in and around the ''Scorpion'' site. The Navy reports no significant release of nuclear material from the sub. The 1985 photos were taken by a team of oceanographers working for the ] in ]. | |||

| An extensive, year-long analysis of Gordon Hamilton's hydroacoustic signals of the submarine's demise was conducted by Robert Price, Ermine Christian, and Peter Sherman of the ] (NOL). All three physicists were experts on undersea explosions, their sound signatures, and their destructive effects. Price was also an open critic of Craven. Their opinion, presented to the Navy as part of the phase II investigation, was that the death noises likely occurred at {{convert|2000|ft|m|abbr=on}} when the hull failed. Fragments then continued in a free fall for another {{convert|9000|ft|m|abbr=on}}. This appears to differ from conclusions drawn by Craven and Hamilton, who pursued an independent set of experiments as part of the same phase II probe, demonstrating that alternate interpretations of the hydroacoustic signals were possibly based on the submarine's depth at the time it was stricken and other operational conditions.{{citation needed|date=August 2019}} | |||

| The Structural Analysis Group (SAG) concluded that an explosive event was unlikely and was highly dismissive of Craven and Hamilton's tests. The SAG physicists argued that the absence of a bubble pulse, which invariably occurs in an underwater explosion, is absolute evidence that no torpedo explosion occurred outside or inside the hull. Craven had attempted to prove that ''Scorpion''{{'}}s hull could "swallow" the bubble pulse of a torpedo detonation by having Gordon Hamilton detonate small charges next to air-filled steel containers.{{citation needed|date=August 2019}} | |||

| The U.S. Navy has periodically monitored the environmental conditions of the site since the sinking and has reported the results in an annual public report on ] for U.S. nuclear-powered ships and boats. The reports provide specifics on the environmental sampling of ], water, and marine life that is done to ascertain whether the submarine has significantly affected the deep-ocean environment. The reports also explain the methodology for conducting this deep sea monitoring from both surface vessels and ]s. The monitoring data confirm that there has been no significant effect on the environment. The nuclear fuel aboard the submarine remains intact and no ] in excess of levels expected from the fallout from past atmospheric testing of ]s has been detected by the Navy's inspections. In addition, ''Scorpion'' carried two nuclear-tipped ] when she was lost. The warheads of these torpedoes are part of the environmental concern. The most likely scenario is that the plutonium and uranium cores of these weapons corroded to a heavy, insoluble material soon after the sinking, and they remain at or close to their original location inside the torpedo room of the boat. If the corroded materials were released outside the submarine, their density and insolubility would cause them to settle into the sediment. | |||

| The 1970 Naval Ordnance Laboratory "Letter",<ref name=2013MFScorpion>{{cite web |last1=Potts |first1=J. R. |title=Our continuation of the USS Scorpion (SSN-589) Nuclear Attack Submarine story |url=http://www.militaryfactory.com/ships/detail-page-2.asp?ship_id=USS-Scorpion-SSN589 |website=Military Factory |access-date=17 August 2014 |archive-date=19 August 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140819084413/http://www.militaryfactory.com/ships/detail-page-2.asp?ship_id=USS-Scorpion-SSN589 |url-status=dead }}</ref> the acoustics study of ''Scorpion'' destruction sounds by Price and Christian, was a supporting study within the SAG report. In its conclusions and recommendations section, the NOL acoustic study states: "The first SCORPION acoustic event was not caused by a large explosion, either internal or external to the hull. The probable depth of occurrence ... and the spectral characteristics of the signal support this. In fact, it is very unlikely that any of the ''Scorpion'' acoustic events were caused by explosions."<ref name="2013MFScorpion" /> | |||

| ===Call for inquiry: 2012=== | |||

| In November 2012, the ], an organization with over 13,800 members, asked the U.S. Navy to reopen the investigation on the sinking of USS ''Scorpion''. The Navy denied approval to re-open the investigation of the cause. A private group including family members of the lost submariners stated they would investigate the wreckage on their own since it was located in international waters.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/sciencefair/2012/11/10/scorpion-expedition-navy/1692343/ |title=Submarine vets call for USS Scorpion investigation |publisher=Usatoday.com |date=16 November 2012 |accessdate=2014-03-17}}</ref> | |||

| The NOL based many of its findings on an extensive acoustic analysis of the torpedoing and sinking of the decommissioned submarine {{USS|Sterlet|SS-392|2}} in the Pacific in early 1969, seeking to compare its acoustic signals to those generated by ''Scorpion''. Price found the Navy's scheduled sinking of ''Sterlet'' fortunate. Nonetheless, ''Sterlet'' was a small World War II-era diesel-electric submarine of a vastly different design and construction from ''Scorpion'' with regard to its pressure hull and other characteristics. Its sinking resulted in three identifiable acoustic signals, as compared to ''Scorpion''{{'}}s 15.<ref name="2013MFScorpion" />{{better source needed|date=June 2018}} | |||

| ==Theories about the loss== | |||

| {{refimprove section|date=August 2014}} | |||

| The NOL acoustics study provided a highly debated explanation as to how ''Scorpion'' may have reached its crush depth by anecdotally referring to the near-loss incident of the diesel submarine {{USS|Chopper|SS-342|2}} in January 1969, when a power problem caused her to sink almost to crush depth, before surfacing.<ref>{{Cite web |title=H-019-3 Navy Non-Combat Submarine Losses |url=https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-019/h-019-3.html |access-date=2023-07-20 |website=NHHC |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| ===Accidental activation of torpedo=== | |||

| The U.S. Navy's ] listed as one possibility the inadvertent activation of a battery-powered ]. This acoustic homing torpedo, in a fully ready condition and without a propeller guard, is believed by some to have started running within the tube. Released from the tube, the torpedo then somehow became fully armed and successfully engaged its nearest target — ''Scorpion''. This is considered highly unlikely due to the fact that ''Scorpion'' would have maintained the ability to destroy the weapon before it reengaged. Although much has been made of claims by Dr. Craven that the ] network tracked the submarine moving back onto its original course, which would be consistent with performing a 180° turn in an attempt to activate a torpedo's safety systems, Gordon Hamilton has said that the acoustical data are too garbled to reveal any such details. | |||

| In the same May 2003 N77 letter excerpted above (see 1. with regard to the Navy's view of a forward explosion), however, the following statement appears to dismiss the NOL theory, and again unequivocally point the finger toward an explosion forward:{{citation needed|date=August 2019}} | |||

| ===Explosion of torpedo=== | |||

| A later theory was that a torpedo may have exploded in the tube, caused by an uncontrollable fire in the torpedo room. The book '']'' documents findings and investigation by Dr. John Craven, who surmised that a likely cause could have been the overheating of a faulty battery.<ref>Sontag and Drew, ''Blind Man's Bluff,'' p. 432.</ref> (Dr. Craven later stated in the book ''Silent Steel'' that he was misquoted.) The Mark 46 ] used in the Mark 37 torpedo had a tendency to overheat, and in extreme cases could cause a fire that was strong enough to cause a low-order detonation of the warhead. If such a detonation had occurred, it might have opened the boat's large torpedo-loading hatch and caused ''Scorpion'' to flood and sink. However, while Mark 46 batteries have been known to generate so much heat that the torpedo casings blistered, none is known to have damaged a boat or caused an explosion.<ref>{{cite book|first=Stephen|last=Johnson|title=Silent Steel: The Mysterious Death of the Nuclear Attack Sub USS Scorpion|location=]|publisher=]|year=2006|page=304}}</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|The Navy has extensively investigated the loss of ''Scorpion'' through the initial court of inquiry and the 1970 and 1987 reviews by the Structural Analysis Group. Nothing in those investigations caused the Navy to change its conclusion that an unexplained catastrophic event occurred.}} | |||

| Dr. John Craven mentions that he did not work on the Mark 37 torpedo's propulsion system and only became aware of the possibility of a battery explosion twenty years after the loss of ''Scorpion''. In his book ''The Silent War'', he recounts running a simulation with former ''Scorpion'' ] Lieutenant Commander Robert Fountain, Jr. commanding the simulator. Fountain was told he was headed home at 18 knots (33 km/h) at a depth of his choice, then there was an alarm of "hot running torpedo". Fountain responded with "right full rudder", a quick turn that would activate a safety device and keep the torpedo from arming. Then an explosion in the torpedo room was introduced into the simulation. Fountain ordered emergency procedures to surface the boat, stated Dr. Craven, "but instead she continued to plummet, reaching collapse depth and imploding in ninety seconds — one second shy of the acoustic record of the actual event." | |||

| === Wreck site === | |||

| Craven, who was the Chief Scientist of the Navy's Special Projects Office, which had management responsibility for the design, development, construction, operational test and evaluation and maintenance of the ] Fleet Missile System had long believed ''Scorpion'' was struck by her own torpedo, but revised his views during the mid-1990s when engineers testing Mark 46 batteries at Keyport, Washington, said the batteries leaked electrolyte and sometimes burned while outside their casings during lifetime shock, heat and cold testing. Although the battery manufacturer was accused of building bad batteries, it was later able to successfully prove its batteries were no more prone to failure than those made by other manufacturers. | |||

| ]es]] | |||

| ] | |||

| The remains of the ''Scorpion'' are reportedly resting on a sandy seabed at {{nowrap|{{coord|32|54.9|N|33|08.89|W|type:event_scale:20000000_region:XA}}}} in the North Atlantic Ocean.<ref name=opnav>Command History of the Commander in Chief U.S. Atlantic Fleet, OPNAV REPORT 5750-1, July 1968 – June 1969, p. 104 at 4. a.</ref> The wreck lies at a depth of {{convert|3000|m|ft|abbr=on|order=flip}} about {{convert|400|nmi|km|abbr=on}} southwest of the Azores on the eastern edge of the ].<ref name=opnav/> | |||

| ===Malfunction of trash disposal unit=== | |||

| During the 1968 inquiry, Vice Admiral Arnold F. Shade testified that he believed that a malfunction of the trash disposal unit (TDU) was the trigger for the disaster. Shade theorized that the sub was flooded when the TDU was operated at ] and that other subsequent failures of material or personnel while dealing with the TDU-induced flooding led to the sub's demise.<ref name="HoustonChronicle 1993-05-21 #1">{{cite news |first=Stephen | last=Johnson | title=A long and deep mystery/Scorpion crewman says sub's '68 sinking was preventable | date=23 May 1993 | publisher=] | url =http://www.chron.com/CDA/archives/archive.mpl?id=1993_1130936 | work =] | accessdate =27 June 2008 }}</ref> | |||

| The U.S. Navy periodically revisits the site to determine whether wreckage has been disturbed and to test for the release of any fissile materials from the submarine's nuclear reactor or two nuclear weapons. Except for a few photographs taken by deep-water submersibles in 1968 and 1985, the U.S. Navy has never made public any physical surveys it has conducted on the wreck. The last photos were taken by ] and a team of oceanographers from Woods Hole using the ] Alvin in 1985. The U.S. Navy secretly lent Ballard the submersible to visit the wreck sites of the ''Thresher'' and ''Scorpion''. In exchange for his work, the U.S. Navy then allowed Ballard, a USNR officer, to use the same submersible to search for {{RMS|Titanic}}.<ref>], 2 June 2008</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title='TITANIC' DISCOVERY WAS BYPRODUCT OF MILITARY QUEST |url=https://www.tampabay.com/archive/2008/11/24/titanic-discovery-was-byproduct-of-military-quest/ |access-date=2023-06-23 |website=Tampa Bay Times |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ===Soviet attack=== | |||

| The book ''All Hands Down'' by Kenneth Sewell and Jerome Preisler (Simon and Schuster, 2008) concludes that the ''Scorpion'' was destroyed while en route to gather intelligence on a Soviet naval group conducting operations in the Atlantic.<ref>{{cite book|first1=Kenneth|last1=Sewell|first2=Jerome|last2=Preisler|title=All Hands Down: The True Story of the Soviet Attack on the USS Scorpion|location=New York|publisher=]|year=2008|page=288}}</ref> While the mission for which the submarine was diverted from her original course back to her home port is a matter of record, its details remain classified. | |||

| Due to the radioactive nature of the ''Scorpion'' wreck site, the U.S. Navy has had to publish what specific environmental sampling it has done of the ], water, and marine life around the sunken submarine to establish what impact it has had on the ]. The information is contained within an annual public report on the U.S. Navy's ] for all U.S. nuclear-powered ships and boats. The reports explain the methodology for conducting deep-sea monitoring from both surface vessels and submersibles. These reports say the lack of radioactivity outside the wreck shows the nuclear fuel aboard the submarine remains intact and no ] in excess of levels expected from the fallout from past atmospheric testing of ]s has been detected during naval inspections. Likewise, the two nuclear-tipped Mark 45 torpedoes that were lost when the ''Scorpion'' sank show no signs of instability.{{citation needed|date=May 2024}} The plutonium and uranium cores of these weapons likely corroded to a heavy, insoluble material soon after the sinking. The materials remain at or close to their original location inside the boat's torpedo room. If the corroded materials were released outside the submarine, their density and insolubility would cause them to settle into the sediment.<ref></ref>{{synthesis inline|date=May 2024|reason= Needs reliable source that says this in relation to this incident and not an OR/SYN interpretations of element densities.}} | |||

| Ed Offley's book ''Scorpion Down'' promotes a hypothesis suggesting that the ''Scorpion'' was sunk by a Soviet submarine during a standoff that started days before 22 May. Offley also cites that it occurred roughly at the time of the submarine's intelligence-gathering mission, from which she was redirected from her original heading for home; according to Offley, the flotilla had just been harassed by another U.S. submarine, the ].<ref>Offley, ''Scorpion Down'', p. 480.</ref> W. Craig Reed who served on the Haddo a decade later as a Petty Officer and diver, and whose father was a U.S. Navy officer responsible in significant ESM advances in sub detection in the early 1960s, recount similar scenarios to Offley in ''Red November'',<ref>W.C Reed . Red November. Inside the Secret U.S.-Soviet Submarine War. William Morrow. NY(2010) p 212-124 & 287-90</ref> over Soviet torpedoing of the ''Scorpion'' and details his own service on USS ''Haddo'' in 1977 running inside Soviet waters off Vladivostok, when torpedoes appeared to have been fired at the ''Haddo'', but were immediately put down by the Captain as a Soviet torpedo exercise. | |||

| === Call for inquiry: 2012 === | |||

| Both ''All Hands Down'' and ''Scorpion Down'' point toward involvement by the ] spy-ring (the so-called Walker Spy-Ring) led by ] in the heart of the U.S. Navy's communications, stating that it could have known that the ''Scorpion'' was coming to investigate the Soviet flotilla. According to this theory, both navies agreed to hide the truth about both incidents. Several U.S. Navy SSNs collided with Soviet Echo subs in Russian and Scottish waters in this period. Commander Roger Lane Nott, Royal Navy commander of the SSN {{HMS|Splendid|S106|6}} during the 1982 Falklands War, stated that in 1972, during his service as a junior navigation officer on the SSN {{HMS|Conqueror|S48|6}}, a Soviet submarine entered the Scottish Clyde channel and ''Conqueror'' was given the order to 'chase it out'. Having realized it was being pursued, "a very aggressive Soviet Captain turned his submarine and drove it straight at HMS ''Conqueror''. It had been an extremely close call."<ref>Rowland White. ''Vulcan 607''. Bantam/Random House. London (2006), p. 39.</ref> | |||

| In November 2012, the ], an organization with over 13,800 members, asked the U.S. Navy to reopen the investigation on the sinking of USS ''Scorpion''. The Navy rejected the request. A private group including family members of the lost submariners stated they would investigate the wreckage on their own, since it was located in international waters.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/sciencefair/2012/11/10/scorpion-expedition-navy/1692343/ |title=Submarine vets call for USS Scorpion investigation |first=Dan |last=Vergano |date=16 November 2012 |newspaper=] |access-date=17 March 2014}}</ref> | |||

| == Theories about the loss == | |||

| The Soviet submarine force was as professional as the British and the Americans. According to a translated article from '']'', Moscow never issued a 'fire' command during the cold war.<ref>http://rusnavy.com/history/events/scorpion.htm</ref> This is disputed by Royal Navy officers, "there had been other occasions when harassed Russians had fired torpedoes to scare off trails."<ref>R.White. Vulcan 607. Bantam/Random House,(2006)London, p39.</ref> The Navy court of inquiry official statement was that there was not another ship within 200 miles of ''Scorpion'' at the time of the sinking.<ref>Court of inquiry, finding of fact #49 to 53, see http://www.jag.navy.mil/library/investigations/USS%20SCORPAIN%2027%20MAY%2068.pdf</ref> | |||

| === Hydrogen explosion during battery charge === | |||

| Retired acoustics expert Bruce Rule, a long-time analyst for the Integrated Undersea Surveillance System (IUSS), wrote that a ] sank ''Scorpion.''<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.iusscaa.org/articles/brucerule/ |title=The Commentaries of Bruce Rule |website=IUSSCAA.org |access-date=23 February 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Dave Oliver, a retired rear admiral who served in both diesel boats and nuclear submarines, wrote in his book ''Against the Tide'' that ''Scorpion'' was lost as a result of hydrogen build-up due to changes in the ventilation lineup while proceeding to periscope depth. After analysis of the ship's battery cells, this is the leading theory for the loss of ''Scorpion.''<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.navalsubleague.com/assets/tsr%20august%20issue%20web%202015.pdf |title=Respect For Authority – Overrated? |first=Dave |last=Oliver |author-link=David R. Oliver Jr. |date=August 2015 |journal=The Submarine Review |pages=116–124 |access-date=19 January 2018 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170531225941/http://www.navalsubleague.com/assets/tsr%20august%20issue%20web%202015.pdf |archive-date=31 May 2017 }}</ref> This is consistent with two small explosions aboard the submarine, a half-second apart, that were picked up by ]s.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| ===U.S. Navy conclusions=== | |||

| The results of the U.S. Navy's various investigations into the loss of ''Scorpion'' are inconclusive. While the court of inquiry never endorsed Dr. Craven's torpedo theory regarding the loss of ''Scorpion'', its "findings of facts" released in 1993 carried Craven's torpedo theory at the head of a list of possible causes of ''Scorpion''{{'}}s loss. | |||

| === Accidental activation of torpedo === | |||

| The Navy failed to inform the public that both the U.S. Submarine Force Atlantic and the Commander-in-Chief U.S. Atlantic Fleet opposed Craven's torpedo theory as unfounded and also failed to disclose that a second technical investigation into the loss of ''Scorpion'' completed in 1970 actually repudiated claims that a torpedo detonation played a role in the loss of ''Scorpion''. Despite the second technical investigation, the Navy continues to attach strong credence to Craven's view that an explosion destroyed her, as is evidenced by this excerpt from a May 2003 letter from the Navy's Submarine Warfare Division (N77), specifically written by Admiral P.F. Sullivan on behalf of Vice Admiral John J. Grossenbacher (Commander Naval Submarine Forces), the Naval Sea Systems Command, Naval Reactors, and others in the U.S. Navy regarding its view of alternative sinking theories: The official U.S. Navy Reports and Commission findings into the loss of the ''Scorpion'', suggest strongly that the ''Scorpion'' was lost to its own Mk 37 torpedoes. K. Sewell and J Preslier's argument in ''All Hands Down'' that the submarine must have been sunk by Soviet torpedoes can be rejected. Their assertion that the ''Scorpion'' had a speed of 45 knots,<ref>K. Sewell. All Hands Down,p 239.</ref> cf the Mk 37 torpedo speed of 24 knot <ref>K. Sewell. All Hands Down p239.</ref> has no credence. It is unlikely Soviet a/s torpedoes had any better performance than the MK 37 in 1968 and no U.S. Navy/Soviet sub other than the Russian Alfa has ever been reported as have a confirmed speed of more than 33 knots.<ref>Janes Fighting Ships Edition 1975-76 to 1995-96,</ref> There no possibility a Skipjack could have exceeded 35 knots in good condition and the ''Scorpion'' carried 10 Mk 37 Mod 1 wire guided a/s torpedoes, set to run at 26 knots to targets up to 6 miles, as well as the Mk 37 unarmed training variant and Mk 14 fast torpedoes for surface targets <ref>S. Johnson. Silent Steel. The Mysterious Death of the Nuclear Attack Submarine USS ''Scorpion''. J. Wiley & Sons. NJ (2006), p18-20</ref> The photographic evidence suggests that the ''Scorpion''{{'}}s prop has been taken off by the Mk 37 which is exactly the way the Mk 37 and related Mk 46 attack submarine, they home on the prop shaft and take it off with a small explosion.<ref>The Mk 37 is an acoustic/ active homing which would have exploded under the keel or taken the propeller shaft off, it would have exploded externally</ref> The issue is how the Mk 37 fired. There is evidence that the ''Scorpion'' was running in the Black sea in internal Soviet waters and it is certain its crew included a number of officers and ratings who were Russian speakers translators. Had ''Scorpion'' detected evidence that the Russians were intercepting U.S. Navy communications it is unlikely to have sent that message by closed/open channels until it reached Norfolk. The fast Skipjack class were capable of 30 to 33 knots and were unlikely to have been intercepted by a 22-knot Echo submarine and speculation about the ''Scorpion''{{'}}s condition may well be just another official attempt to confuse the issue of strategic significance in 1968 at possibly the most dangerous point of the Cold War.<ref>K. Sewell. ''All Hands Down. The True Story of the Soviet Attack on the Soviets''. p 241 and Pravda 4/29/ 2008 RusNavy. RU.</ref> The leading U.S. Admirals and defense advisers may have also suppressed issues of potential espionage, and drug use and disorder on U.S. Navy surface warships and submarines in the Vietnam war period. Another possibility is that Captain Slattery may have issued orders to fire the Mk 37 under stress having heard a false echo of a sonar reader after possibly being harassed and even engaged earlier in the long deployment by Soviet submarines. U.S. Navy and RAN destroyers chased false echo sonar indications several times during the Vietnam war, n.b. USS ''Turner Joy'' and USS ''Maddox'' in the Gulf of Tonkin Incident.<ref>Robert McNamara interview. Fog of War, DVD & J.P. Carroll. Out of sight, out of mind. The RAN Vietnam 1965-1972. Rosenburg. NSW (2013)</ref> Older RN frigates constantly heard false torpedo tracks during the Falklands War. On the day HMS ''Sheffield'' was sunk, HMS ''Yarmouth'' communicated it was under torpedo attack on nine separate incidents during the day, using the non-Doppler 170/177 passive/active pulse.<ref>Admiral S.Woodward. One hundred days. The memoirs of the Falklands battleground command.#rd ed. Harper Publishing. London (2012), p22.</ref> | |||

| The classified version of the U.S. Navy's court of inquiry's report, released in 1993, listed accidents involving the ] as three of the most probable causes for the loss of submarine,<ref>N.Polmar ' Another Submarine is Missing, in 'The death of USS Thresher'. 2nd ed. Chilton Books (2001). First Lyons.(2017), p166-168</ref> including a hot-running torpedo, an accidentally or deliberately launched weapon, or the inadvertent activation of a torpedo by stray voltage. The acoustic homing torpedo, in a fully ready condition and lacking a propeller guard, is theorized by some to have started running within the tube. Released from the tube, the torpedo then somehow became fully armed and engaged its nearest target: ''Scorpion'' herself.<ref name="friedman 20-21">{{cite book |last1=Friedman |first1=Norman |title=U.S. Submarines Since 1945: An Illustrated Design History |url=https://archive.org/details/ussubmarinessinc1945frie |url-access=limited |date=1994 |publisher=U.S. Naval Institute |isbn=1-55750-260-9 |pages=–21}}</ref> | |||

| === Explosion of torpedo inside sub === | |||

| {{quote|The first cataclysmic event was of such magnitude that the only possible conclusion is that a cataclysmic event (explosion) occurred resulting in uncontrolled flooding (most likely the forward compartments).}} | |||

| A later theory was that a fire in the torpedo room had caused a torpedo to explode in the tube. The book '']'' documents findings and investigation by John Craven, who was the chief scientist of the Navy's Special Projects Office, which had management responsibility for the design, development, construction, operational test and evaluation, and maintenance of the ] fleet missile system. Craven surmised that a faulty battery had overheated.{{sfnp|Sontag|Drew|2000|p=432}} The Mark 46 ] used in the Mark 37 torpedo had a tendency to overheat, and in extreme cases could cause a fire that was strong enough to cause a low-order detonation of the warhead. If such a detonation had occurred, it might have opened the boat's large torpedo-loading hatch and caused ''Scorpion'' to flood and sink. However, while Mark 46 batteries have been known to generate so much heat that the torpedo casings blistered, none are known to have damaged a boat or caused an explosion.<ref>{{cite book |first=Stephen |last=Johnson |title=Silent Steel: The Mysterious Death of the Nuclear Attack Sub USS Scorpion |location=] |publisher=] |year=2006 |page=304 |isbn=978-0-471-26737-9 |url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780471267379 |url-access=limited }}</ref> | |||

| Craven mentions that he did not work on the Mark 37 torpedo's propulsion system and became aware of the possibility of a battery explosion only 20 years after the loss of ''Scorpion''. In his book ''The Silent War'', he recounts a simulation run by former ''Scorpion'' ] Lieutenant Commander Robert Fountain Jr. Fountain was told he was headed home at 18 knots (33 km/h) at a depth of his choice, then there was an alarm of "hot-running torpedo". Fountain responded with "right full rudder", a quick turn that would activate a safety device and keep the torpedo from arming. Then, an explosion in the torpedo room was introduced. Fountain ordered emergency procedures to surface the boat, Craven wrote, "but instead, she continued to plummet, reaching collapse depth and imploding in 90 seconds – one second shy of the acoustic record of the actual event."{{citation needed|date=August 2019}} | |||

| ===Hydrogen explosion=== | |||

| In his book ''Against the Tide: Rickover's Leadership Principles and the Rise of the Nuclear Navy'' (2014), and in particular in a section titled "The Danger of Culture," retired U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Dave Oliver offers a convincing flow of logic that it was quite likely a hydrogen explosion, either during or immediately following a battery charge, that destroyed USS ''Scorpion'' and killed her crew.<ref>{{Cite book | isbn = 1612517978 | page = 43 | last = Oliver | first = Dave | title = Against the Tide | year = 2014 | publisher = Naval Institute Press | location = Annapolis, MD }}</ref> | |||

| Craven had long believed ''Scorpion'' was struck by her own torpedo, but revised his views during the mid-1990s, when he learned that engineers testing Mark 46 batteries at ], just before the ''Scorpion's'' loss, said the batteries leaked electrolyte and sometimes burned while outside their casings during lifetime shock, heat, and cold testing. Although the battery manufacturer was accused of building bad batteries, it was later able to successfully prove its batteries were no more prone to failure than those made by other manufacturers.{{citation needed|date=August 2019}} | |||

| In the mid-1960s, diesel boat operational styles still permeated the U.S. submarine force, and in particular the setting of "Condition Baker" (the closing of all watertight hatches) upon proceeding to periscope depth. Condition Baker was a hard lesson-learned during diesel boat days, as the crew frequently went to periscope depth to charge the battery with the diesel engines, and these excursions commonly took place near shipping lanes due to the submarines' largely anti-surface ship mission. The setting of watertight conditions prior to proceeding to periscope depth, along with design changes that permitted one compartment to flood without losing the boat, essentially increased the survivability of diesel boats during collisions. Notably, diesel boats could only charge their batteries while on the surface or at periscope depth and were running their diesel engines, which ventilated the entire ship, including the battery well. | |||

| === Intentional firing of defective torpedo === | |||

| As Oliver describes from a personal incident he was central to on board {{USS|George Washington Carver|SSBN-656}}, the setting of Condition Baker was still a standard, inherited practice on nuclear-powered submarines, even though compared to diesel boats they did not spend nearly as much time near shipping lanes, and also rarely charged their batteries — commonly monthly as opposed to several times daily. | |||

| Twenty years later, Craven learned that the boat could have been destroyed by a "hot-running torpedo." Other subs in the fleet had replaced their defective torpedo batteries, but the Navy wanted ''Scorpion'' to complete its mission first. If ''Scorpion'' had fired a defective torpedo, it could have sought out a target and turned back to strike the sub that launched it.<ref>{{cite book |first1=Sharon |last1=McGrayne |title=The Theory That Would Not Die: How Bayes' Rule Cracked the Enigma Code, Hunted Down Russian Submarines & Emerged Triumphant from Two Centuries of Controversy |url=https://archive.org/details/theorythatwouldn0000mcgr |url-access=registration |location=New Haven & London |publisher=] |year=2011 |page= |isbn=978-0-300-16969-0}}</ref> | |||

| === Structural damage === | |||

| In the underway submerged incident aboard ''Carver'', Condition Baker was once inadvertently set — essentially stopping air flow to the battery well — while a battery charge was ongoing and nearly complete. Oliver was on watch as Engineering Officer of the Watch, and, while he clearly lived to tell the tale, witnessed the hydrogen readings in the battery well exceed 7 percent, even despite having stopped the battery charge upon setting Condition Baker. The lower limit at which hydrogen forms a combustible mixture with air is 4 percent. | |||

| Photographs of the ''Scorpion'' wreck show the submarine's detached shaft and propeller, missing a rotor blade. Some experienced U.S. submariners attribute the loss of the submarine to flooding caused by the detached shaft.<ref>N. Polmar. Another Submarine is Missing in Norman Polmar the Death of USS Thresher. First Lyon Press (Globe Pequot) 2001, 2017) p 161-172</ref><ref>N. Polmar; The death of USS Thresher, 2nd ed; First Lyon, (2004, 2017) p. 167</ref> Given that antisubmarine torpedoes were designed to seek the sound of the cavitation of the target submarine's propeller, this could be damage caused by such a weapon.<ref>N. Friedman. Naval Institute to US Naval Weapons. fifth edition USNI Annapolis & D.Owen. History of anti submarine warfare (2007) p. 208.</ref> | |||

| === Malfunction of trash disposal unit === | |||

| While ''Carver'', due to the above incident, stopped setting Condition Baker during preparations for proceeding to periscope depth, this was not a fleet-wide change. Two years after the ''Carver'' incident, ''Scorpion'' was lost. Per above, the Navy's findings on the loss of ''Scorpion'' were inconclusive, however it was established with some confidence that the boat was lost due to an explosion in the forward compartment — where the ship's battery well is located — and while at or near periscope depth. | |||