| Revision as of 03:13, 31 July 2006 view sourceTjmayerinsf (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers58,637 edits →Second marriage← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:57, 4 January 2025 view source Simon Peter Hughes (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers16,914 edits →See also: Removing non-Misplaced Pages rticle.Tag: 2017 wikitext editor | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|American author, journalist and social activist (1876–1916)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Other people}} | |||

| '''Jack London''', probably born '''John Griffith Chaney''' (], ] – ], ])<ref>Birth and death dates as given in Dictionary of American Biography Base Set. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928-1936. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale. 2006. http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/BioRC</ref><ref>Joan London (1939) p. 12, birth date</ref><ref>"JACK LONDON DIES SUDDENLY ON RANCH; Novelist is Found Unconscious from Uremia, and Expires after Eleven Hours. WROTE HIS LIFE OF TOIL His Experience as Sailor Reflected In His Fiction—''Call of the Wild'' Gave Him His Fame." | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| '''The New York Times,''' story datelined Santa Rosa, Cal., Nov. 22; appeared November 23, 1916, p. 13. States he died "at 7:45 o'clock tonight," and says he was "born in San Francisco on January 12, 1876."</ref> was an ] ] who wrote '']'' and over fifty other books. A pioneer in the then-burgeoning world of commercial magazine fiction, he was one of the first Americans to make a huge financial success from writing.<ref>(1910) "Rewards of Short-Story Writing," The Writer, XXII, January-December 1910, p. 9: "There are eight American writers who can get $1000 for a short story—], ], Jack London, ], ], ], ], and ]." $1,000 in 1910 dollars is roughtly equivalent to $20,000 in 2005.</ref> | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=July 2023}} | |||

| {{Infobox writer | |||

| | name = Jack London | |||

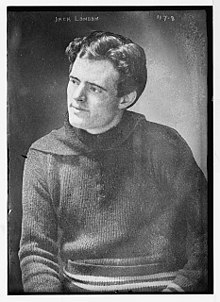

| | image = Jack London young.jpg | |||

| | caption = London in 1903 | |||

| | birth_name = John Griffith Chaney | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|mf=yes|1876|1|12}} | |||

| | birth_place = San Francisco, California, U.S. | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|mf=yes|1916|11|22|1876|1|12}} | |||

| | death_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | occupation = {{flatlist| | |||

| * Novelist | |||

| * journalist | |||

| * short story writer | |||

| * essayist | |||

| }} | |||

| | notableworks = '']'' (1903)<br>'']'' (1906)<br>'']'' (1908)<br>'']'' (1909) | |||

| | movement = ], ] | |||

| | spouse = {{plainlist| | |||

| * {{marriage|Elizabeth Maddern|April 7, 1900|November 11, 1904|end=divorced}} | |||

| * {{marriage|]|1905}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | signature = Jack London Signature.svg | |||

| | children = ]<br />Becky London | |||

| }} | |||

| '''John Griffith Chaney'''{{sfn|Reesman|2009|p=}}{{Efn|later renamed '''John Griffith London''' (see ] section)|group=upper-alpha}} (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as '''Jack London''',<ref>"". ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' Library Edition. Retrieved October 5, 2011.</ref><ref>''''. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928–1936. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale. 2006.</ref>{{sfn|London|1939|p=12}}{{sfn|New York Times November 23, 1916}} was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to become an international celebrity and earn a large fortune from writing.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Haley |first=James |title=Wolf: The Lives of Jack London |date=2011 |publisher=Basic Books |isbn=978-0465025039 |pages=12–14}}</ref> He was also an innovator in the genre that would later become known as science fiction.<ref>(1910) "Specialty of Short-story Writing," The Writer, XXII, January–December 1910, p. 9: "There are eight American writers who can get $1000 for a short story—], ], Jack London, ], ], ], ], and ]." $1,000 in 1910 dollars is roughly equivalent to ${{Formatnum:{{Inflation|US|1000|1910|r=-3}}}} today</ref> | |||

| ==Personal background== | |||

| Clarice Stasz and other biographers believe it to be likely that Jack London's biological father was ] William Chaney.<ref>Stasz (2001), p. 14: "What supports Flora's naming Chaney as the father of her son are, first, the indisputable fact of their cohabiting at the time of his conception;, and second, the absence of any suggestion on the part of her associates that another man could have been responsible... unless DNA evidence is introduced, whether or not WIlliam Chaney was the biological father of Jack London cannot be decided.... Chaney would, however, be considered by her son and his children as their ancestor."</ref> Chaney was a professor in astrology; according to Stasz, "From the viewpoint of serious astrologers today, Chaney is a major figure who shifted the practice from quackery to a more rigorous method." | |||

| London was part of the radical literary group "The Crowd" in San Francisco and a passionate advocate of ], ] and ].<ref name="Swift2002">Swift, John N. "Jack London's 'The Unparalleled Invasion': Germ Warfare, Eugenics, and Cultural Hygiene." American Literary Realism, vol. 35, no. 1, 2002, pp. 59–71. {{JSTOR|27747084}}.</ref><ref name="Hensely2002">Hensley, John R. "Eugenics and Social Darwinism in Stanley Waterloo's 'The Story of Ab' and Jack London's 'Before Adam.'" Studies in Popular Culture, vol. 25, no. 1, 2002, pp. 23–37. {{JSTOR|23415006}}.</ref> London wrote several works dealing with these topics, such as his ] '']'', his non-fiction ] '']'', ''War of the Classes'', and '']''. | |||

| Jack London did not learn of Chaney's putative paternity until adulthood. In 1897 he wrote to Chaney and received a letter in which Chaney stated flatly "I was never married to Flora Wellman", and that he was "impotent" during the period in which they lived together and "cannot be your father." | |||

| His most famous works include '']'' and '']'', both set in ] and the ] during the ], as well as the short stories "]", "An Odyssey of the North", and "Love of Life". He also wrote about the ] in stories such as "The Pearls of Parlay" and "]". | |||

| Whether the marriage was, in fact, legalized is unknown. Most San Francisco civil records were destroyed in the ]. (For the same reason, it is not known with certainty what name appeared on his birth certificate). Stasz notes that in his memoirs Chaney refers to Jack London's mother Drew Barrall, as having been his "wife". Stasz also notes an advertisement in which Flora calls herself "Florence Wellman Chaney". | |||

| == |

== Family == | ||

| {{multiple image | |||

| Jack London was born in ]. He was essentially self-educated. In 1885 he found and read ]'s long Victorian novel ''Signa'', which describes an unschooled Italian peasant child who achieves fame as an opera composer. He credited this as the seed of his literary aspiration.<ref>London, Jack (1917) "Eight Factors of Literary Success," in Labor (1994), p. 512. "In answer to your question as to the greatest factors of my literary success, I will state that I consider them to be: Vast good luck. Good health; good brain; good mental and muscular correlation. Poverty. Reading Ouida's ''Signa'' at eight years of age. The influence of Herbert Spencer's ''Philosophy of Style.'' Because I got started twenty years before the fellows who are trying to start today."</ref> | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | total_width = 340 | |||

| | image1 = Flora Wellman.jpg | |||

| A pivotal event was his discovery in 1886 of the Oakland Public Library and a sympathetic librarian, ] (who later became California's first poet laureate and an important figure in the San Francisco literary community). | |||

| | alt1 = | |||

| | caption1 = | |||

| | image2 = John London.jpg | |||

| In 1893, he signed on to the sealing ] ''Sophia Sutherland'', bound for the coast of Japan. When he returned, the country was in the grip of the ] and ] was swept by labor unrest. After gruelling jobs in a ] and a street-railway power plant, he joined ] and began his career as a tramp. | |||

| | caption2 = | |||

| | footer =Flora and John London, Jack's mother and stepfather | |||

| In 1894, he spent thirty days for vagrancy in the Erie County Penitentiary at ]. In ''The Road'', he wrote: | |||

| }} | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| "Man-handling was merely one of the very minor unprintable horrors of the Erie County Pen. I say 'unprintable'; and in justice I must also say 'unthinkable'. They were unthinkable to me until I saw them, and I was no spring chicken in the ways of the world and the awful abysses of human degradation. It would take a deep plummet to reach bottom in the Erie County Pen, and I do but skim lightly and facetiously the surface of things as I there saw them." | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| Jack London was born January 12, 1876.<ref>{{cite news|url= https://www.upi.com/Top_News/2021/01/12/UPI-Almanac-for-Tuesday-Jan-12-2021/5231610417906/|title= UPI Almanac for Tuesday, Jan. 12, 2021|work= ] | date= January 12, 2021|accessdate=February 27, 2021 | archive-date= January 29, 2021|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20210129023331/https://www.upi.com/Top_News/2021/01/12/UPI-Almanac-for-Tuesday-Jan-12-2021/5231610417906/|url-status=live|quote = ...novelist Jack London in 1876...}}</ref> His mother, Flora Wellman, was the fifth and youngest child of ] builder Marshall Wellman and his first wife, Eleanor Garrett Jones. Marshall Wellman was descended from ], an early ] settler in the ].<ref name="Wellman1918">Wellman, Joshua Wyman ''Descendants of Thomas Wellman'' (1918) Arthur Holbrook Wellman, Boston, p. 227</ref> Flora left Ohio and moved to the Pacific coast when her father remarried after her mother died. In San Francisco, Flora worked as a music teacher and ].<ref name="london">{{cite web |url=http://www.jacklondons.net/writings/BookJackLondon/Volume1/chapter1.html |title=The Book of Jack London |publisher=The World of Jack London |access-date=April 7, 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110511125518/http://www.jacklondons.net/writings/BookJackLondon/Volume1/chapter1.html |archive-date=May 11, 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| After many experiences as a hobo, sailor, and member of ] he returned to Oakland and attended Oakland High School, where he contributed a number of articles to the high school's magazine, ''The Aegis''. His first published work was "Typhoon off the coast of Japan", an account of his sailing experiences. | |||

| Biographer Clarice Stasz and others believe London's father was ] William Chaney.<ref>{{harvnb|Stasz|2001|p=14}}: "What supports Flora's naming Chaney as the father of her son are, first, the indisputable fact of their cohabiting at the time of his conception, and second, the absence of any suggestion on the part of her associates that another man could have been responsible... unless ] evidence is introduced, whether or not William Chaney was the biological father of Jack London cannot be decided.... Chaney would, however, be considered by her son and his children as their ancestor."</ref> Flora Wellman was living with Chaney in San Francisco when she became pregnant. Whether Wellman and Chaney were legally married is unknown. Stasz notes that in his memoirs, Chaney refers to London's mother Flora Wellman as having been "his wife"; he also cites an advertisement in which Flora called herself "Florence Wellman Chaney".<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.booktable.net/book/9781500900946|title=Before Adam (Paperback) {{!}} The Book Table|website=www.booktable.net|language=en|access-date=February 12, 2020}}{{Dead link|date=February 2020 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> | |||

| Jack London desperately wanted to attend the ] and, in 1896 after a summer of intense cramming, did so; but financial circumstances forced him to leave in 1897 and so he never graduated. Kingman says that "there is no record that Jack ever wrote for student publications" there.<ref>Kingman (1979) p. 67.</ref> | |||

| According to Flora Wellman's account, as recorded in the '']'' of June 4, 1875, Chaney demanded that she have an abortion. When she refused, he disclaimed responsibility for the child. In desperation, she shot herself. She was not seriously wounded, but she was temporarily deranged. After giving birth, Flora sent the baby for ] to ], a neighbor and former slave. Prentiss was an important maternal figure throughout London's life, and he would later refer to her as his primary source of love and affection as a child.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| In 1889, London began working from twelve to eighteen hours a day at Hickmott's Cannery. Seeking a way out of this gruelling labor, he borrowed money from his black foster mother Virginia Prentiss., bought the ] ''Razzle-Dazzle'' from an ] named French Frank, and became an oyster pirate himself. In '']'' he claims to have stolen French Frank's mistress Mamie.<ref>{{gutenberg|no=318|name=John Barleycorn ''by Jack London''}} Chapters VII, VIII describe his stealing of Mamie, the "Queen of the Oyster Pirates:" "the Queen asked me to row her ashore in my skiff...Nor did I understand Spider's grinning side-remark to me: "Gee! There's nothin' slow about YOU." How could it | |||

| possibly enter my boy's head that a grizzled man of fifty should be jealous of me?" "And how was I to guess that the story of how the Queen had thrown him down on his own boat, the moment I hove in sight, was already the gleeful gossip of the water-front?</ref><ref>Joan London (1939) appears to credit this story, op. cit. p. 41</ref><ref>Kingman (1979) expresses skepticism; p. 37, "It was said on the waterfront that Jack had taken on a mistress... Evidently Jack believed the myth himself at times... Jack met Mamie aboard the Razzle-Dazzle when he first approached French Frank about its purchase. Mamie was aboard on a visit with her sister Tess and her chaperone, Miss Hadley. It hardly seems likely that someone who required a chaperone on Saturday would move aboard as mistress on Monday."</ref> After a few months his sloop became damaged beyond repair. He switched to the side of the law and became a member of the ]. | |||

| Late in 1876, Flora Wellman married John London, a partially disabled ] veteran, and brought her baby John, later known as Jack, to live with the newly married couple. The family moved around the ] before settling in ],<ref name="Niekerken">{{Cite news |last=Niekerken |first=Bill Van |title=Jack London Square's early days: A saloon, a local sports hero and a floating restaurant |url=https://www.sfchronicle.com/chronicle_vault/article/Jack-London-Square-s-early-days-A-saloon-a-14993216.php |access-date=2024-01-15 |work=San Francisco Chronicle |language=en}}</ref> where London completed public grade school. The Prentiss family moved with the Londons, and remained a stable source of care for the young Jack.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| While living at his rented villa on ] in Oakland, London met poet ] and in time they became best of friends. In 1902 Sterling helped London find a home closer to his own in nearby ]. In his letters London addressed Sterling as "Greek" owing to his aquiline nose and classical profile, and signed them as "Wolf". London was later to depict Sterling as Russ Brissenden in his autobiographical novel '']'' (1909) and as Mark Hall in '']'' (1913). | |||

| In 1897, when he was 21 and a student at the ], London searched for and read the newspaper accounts of his mother's suicide attempt and the name of his biological father. He wrote to William Chaney, then living in Chicago. Chaney responded that he could not be London's father because he was impotent; he casually asserted that London's mother had relations with other men and averred that she had slandered him when she said he insisted on an abortion.{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|pp=52–53}} London was devastated by his father's letter; in the months following, he quit school at Berkeley and went to the ] during the gold rush boom. | |||

| In later life Jack London was a ] with wide-ranging interests and a personal library of 15,000 volumes.<ref>Hamilton (1986) (as cited by other sources)</ref> | |||

| == Early life == | |||

| On ], ], London and his brother in law James Shepard sailed to join the ] where he would later set his first successful stories. London's time in the Klondike, however, was quite detrimental to his health. Like so many others malnourished while involved in the Klondike Gold Rush, he developed ]. His gums became swollen, eventually leading to the loss of his four front teeth. A constant gnawing pain affected his abdomen and leg muscles, and his face was stricken with sores. Fortunately for him and others who were suffering with a variety of medical ills, a Father William Judge, "The Saint of Dawson", had a facility in Dawson which provided shelter, food and any available medicine. London's health recovered. London's life was perhaps saved by the Jesuit priest. | |||

| ] | |||

| London was born near Third and Brannan Streets in San Francisco. The house burned down in the fire after the ]; the ] placed a plaque at the site in 1953. Although the family was working class, it was not as impoverished as London's later accounts claimed.{{Citation needed|date=March 2012}} London was largely self-educated.{{Citation needed|date=March 2012}} | |||

| London survived the hardships of the Klondike, and these struggles inspired what is often called his best short story, ] (v. i). | |||

| In 1885, London found and read ]'s long ] novel ''Signa''.<ref name="archive.org">{{Cite web |url=https://archive.org/details/signastory01ouid |title=Signa. A story |last=Ouida |date=July 26, 1875 |publisher=London : Chapman & Hall |via=Internet Archive}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://archive.org/details/signastory02ouid |title=Signa. A story |last=Ouida |date=July 26, 1875 |publisher=London : Chapman & Hall |via=Internet Archive}}</ref> He credited this as the seed of his literary success.<ref>London, Jack (1917) "Eight Factors of Literary Success", in ''Labor'' (1994), p. 512. "In answer to your question as to the greatest factors of my literary success, I will state that I consider them to be: Vast good luck. Good health; good brain; good mental and muscular correlation. Poverty. Reading Ouida's ''Signa'' at eight years of age. The influence of ]'s ''Philosophy of Style.'' Because I got started twenty years before the fellows who are trying to start today."</ref> In 1886, he went to the ] and found a sympathetic librarian, ], who encouraged his learning. (She later became California's first '']'' and an important figure in the San Francisco literary community).<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://www.sonomanews.com/lifestyle/6003083-181/jack-londons-inspirational-librarian-remembered |title=State's first poet laureate remembered at Jack London |date=August 22, 2016 |work=Sonoma Index Tribune |access-date=February 2, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180203005853/http://www.sonomanews.com/lifestyle/6003083-181/jack-londons-inspirational-librarian-remembered |archive-date=February 3, 2018 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| In 1889, London began working 12 to 18 hours a day at Hickmott's Cannery. Seeking a way out, he borrowed money from his foster mother Virginia Prentiss, bought the ] ''Razzle-Dazzle'' from an ] named French Frank, and became an oyster pirate himself. In his memoir, '']'', he claims also to have stolen French Frank's mistress Mamie.<ref>{{Gutenberg|no=318|name=John Barleycorn|author=Jack London}} Chapters VII, VIII describe his stealing of Mamie, the "Queen of the Oyster Pirates": "The Queen asked me to row her ashore in my skiff...Nor did I understand Spider's grinning side-remark to me: "Gee! There's nothin' slow about YOU." How could it possibly enter my boy's head that a grizzled man of fifty should be jealous of me?" "And how was I to guess that the story of how the Queen had thrown him down on his own boat, the moment I hove in sight, was already the gleeful gossip of the water-front?</ref>{{sfn|London|1939|p=41}}<ref>{{harvnb|Kingman|1979|p=37}}: "It was said on the waterfront that Jack had taken on a mistress... Evidently Jack believed the myth himself at times... Jack met Mamie aboard the Razzle-Dazzle when he first approached French Frank about its purchase. Mamie was aboard on a visit with her sister Tess and her chaperone, Miss Hadley. It hardly seems likely that someone who required a chaperone on Saturday would move aboard as mistress on Monday."</ref> After a few months, his sloop became damaged beyond repair. London hired on as a member of the ]. | |||

| His landlords in Dawson were two Yale and Stanford educated mining engineers Marshall and Louis Bond. Their father Judge Hiram Bond was a wealthy mining investor. The Bonds, especially Hiram, were active Republicans. Marshall Bond's diary mentions friendly sparring on political issues as a camp pastime. | |||

| In 1893, he signed on to the ] ] ''Sophie Sutherland'', bound for the coast of Japan. When he returned, the country was in the grip of the ] and ] was swept by labor unrest. After grueling jobs in a ] and a street-railway power plant, London joined ] and began his career as a ]. In 1894, he spent 30 days for vagrancy in the ] Penitentiary at ], New York. In '']'', he wrote: | |||

| Jack left Oakland a believer in the work ethic with a social conscience and socialist leanings and returned to become an active proponent of socialism. He also concluded that his only hope of escaping the work trap was to get an education and "sell his brains". Throughout his life he saw writing as a business, his ticket out of poverty, and, he hoped, a means of beating the wealthy at their own game. | |||

| {{blockquote |text=Man-handling was merely one of the very minor unprintable horrors of the Erie County Pen. I say 'unprintable'; and in justice I must also say undescribable. They were unthinkable to me until I saw them, and I was no spring chicken in the ways of the world and the awful abysses of human degradation. It would take a deep plummet to reach bottom in the Erie County Pen, and I do but skim lightly and facetiously the surface of things as I there saw them. |sign=Jack London |source=''The Road'' }} | |||

| On returning to Oakland in 1898, he began struggling seriously to break into print, a struggle memorably described in his novel, ''Martin Eden''. His first published story was the fine and frequently anthologized "To the Man On Trail". When ''The Overland Monthly'' offered him only $5 for it—and was slow paying—Jack London came close to abandoning his writing career. In his words, "literally and literarily I was saved" when ''The Black Cat'' accepted his story "A Thousand Deaths", and paid him $40—the "first money I ever received for a story". | |||

| After many experiences as a hobo and a sailor, he returned to Oakland and attended ]. He contributed a number of articles to the high school's magazine, ''The Aegis''. His first published work was "Typhoon off the Coast of Japan", an account of his sailing experiences.<ref>{{cite news |publisher=JackLondons.net |title=The First Story Written for Publication |author=Charmian K. London |location=Sonoma County, California |date=August 1, 1922 |url=http://www.jacklondons.net/first_jack_london_story.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131006071440/http://www.jacklondons.net/first_jack_london_story.html |archive-date=October 6, 2013 }}</ref> | |||

| Jack London was fortunate in the timing of his writing career. He started just as new printing technologies enabled lower-cost production of magazines. This resulted in a boom in popular magazines aimed at a wide public, and a strong market for short fiction. In 1900, he made $2,500 in writing, the equivalent of about $75,000 today. His career was well under way. | |||

| ] | |||

| Among the works he sold to magazines was a short story known as either "Batarde" or "Diable" in two editions of the same basic story. A cruel French Canadian brutalizes his dog. The dog out of revenge causes his death. London was criticized for depicting a dog as an embodiment of evil. He told some of his critics that man's actions are the main cause of the behavior of their animals and he would show this in another short story. | |||

| As a schoolboy, London often studied at ], a port-side bar in Oakland. At 17, he confessed to the bar's owner, John Heinold, his desire to attend university and pursue a career as a writer. Heinold lent London tuition money to attend college. | |||

| London desperately wanted to attend the ], located in Berkeley. In 1896, after a summer of intense studying to pass certification exams, he was admitted. Financial circumstances forced him to leave in 1897, and he never graduated. No evidence has surfaced that he ever wrote for student publications while studying at Berkeley.{{sfn|Kingman|1979|p=67}} | |||

| This short story for the Saturday Evening Post "The Call of the Wild" ran away in length. The story begins on an estate in Santa Clara and features a St. Bernard/Shepherd mix named Buck. In fact the opening scene is a description of the Bond family farm and Buck is based on a dog he was lent in Dawson by his landlords. London visited Marshall Bond in California having run into him again at a political lecture in San Francisco in 1901. | |||

| ] | |||

| ==First marriage (1900-1904)== | |||

| Jack London married Bess Maddern on ], ], the same day ''The Son of the Wolf'' was published. Bess had been part of his circle of friends for a number of years. Stasz says "Both acknowledged publicly that they were not marrying out of love, but from friendship and a belief that they would produce sturdy children."<ref>Stasz (2001) p. 61, "Both acknowledged... that they were not marrying out of love"</ref> Kingman says "they were comfortable together …. Jack had made it clear to Bessie that he did not love her, but that he liked her enough to make a successful marriage."<ref>Kingman (1979), p. 98</ref> | |||

| While at Berkeley, London continued to study and spend time at Heinold's saloon, where he was introduced to the sailors and adventurers who would influence his writing. In his autobiographical novel, ''],'' London mentioned the pub's likeness seventeen times. Heinold's was the place where London met Alexander McLean, a captain known for his cruelty at sea.<ref>{{cite book |last=MacGillivray |first=Don |url=http://www.washington.edu/uwpress/search/books/MACCAP.html |title=Captain Alex MacLean |publisher=University of Washington Press |date=2009 |access-date=October 6, 2011 |isbn=978-0774814713}}</ref> London based his protagonist Wolf Larsen, in the novel ''],'' on McLean.<ref>{{cite book |last=MacGillivray |first=Don |url=http://www.ubcpress.ca/books/pdf/chapters/2008/CaptainAlexMacLean.pdf |title=Captain Alex MacLean |year= 2008 |publisher=UBC Press |access-date=October 6, 2011 |isbn=978-0774814713 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110515042050/http://www.ubcpress.ca/books/pdf/chapters/2008/CaptainAlexMacLean.pdf |archive-date=May 15, 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| During the marriage, Jack London continued his friendship with Anna Strunsky, co-authoring ''The Kempton-Wace Letters,'' an epistolary novel contrasting two philosophies of love. Anna, writing "Dane Kempton's" letters, arguing for a romantic view of marriage, while Jack, writing "Herbert Wace's" letters, argued for a scientific view, based on Darwinism and eugenics. | |||

| In the novel, his fictional character contrasts two women he has known: | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| a mad, wanton creature, wonderful and unmoral and filled with life to the brim. My blood pounds hot even now as I conjure her up … a proud-breasted woman, the perfect mother, made preeminently to know the lip clasp of a child. You know the kind, the type. "The mothers of men", I call them. And so long as there are such women on this earth, that long may we keep faith in the breed of men. The wanton was the Mate Woman, but this was the Mother Woman, the last and highest and holiest in the hierarchy of life.<ref name=kemptonwace>''The Kempton-Wace Letters'' (2000 reprint), p. 149 ("a mad, wanton creature....")</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| Heinold's First and Last Chance Saloon is now unofficially named Jack London's Rendezvous in his honor.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://oaklandnorth.net/2011/07/26/the-legends-of-oaklands-oldest-bar/ |title=The legends of Oakland's oldest bar, Heinold's First and Last Chance Saloon |work=Oakland North|access-date=February 2, 2018 }}</ref> | |||

| Wace declares: | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| I purpose to order my affairs in a rational manner …. Wherefore I marry Hester Stebbins. I am not impelled by the archaic sex madness of the beast, nor by the obsolescent romance madness of later-day man. I contract a tie which reason tells me is based upon health and sanity and compatibility. My intellect shall delight in that tie.<ref>''The Kempton-Wace Letters'' (2000 reprint), p. 126 ("I purpose to order my affairs in a rational manner....")</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| == Gold rush and first success == | |||

| Analyzing why he "was impelled toward the woman" he intends to marry, Wace says | |||

| ].]] | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| it was old Mother Nature crying through us, every man and woman of us, for progeny. Her one unceasing and eternal cry: PROGENY! PROGENY! PROGENY!<ref>''The Kempton-Wace Letters'' (2000 reprint), p. 147 ("Progeny! progeny! progeny!")</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| On July 12, 1897, London (age 21) and his sister's husband Captain Shepard sailed to join the ]. This was the setting for some of his first successful stories. London's time in the harsh ], however, was detrimental to his health. Like so many other men who were malnourished in the goldfields, London developed ]. His gums became swollen, leading to the loss of his four front teeth. A constant gnawing pain affected his hip and leg muscles, and his face was stricken with marks that always reminded him of the struggles he faced in the Klondike. ], "The Saint of ]", had a facility in Dawson that provided shelter, food and any available medicine to London and others. His struggles there inspired London's short story, "]" (1902, revised in 1908),{{efn-ua|name="To Build a Fire"| The 1908 version of "To Build a Fire" is available on ] in two places: "]" (Century Magazine) and "]" (in '']'' – 1910). The 1902 version may be found at the following external link: (]) ({{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191228155008/http://london.sonoma.edu/Writings/Uncollected/tobuildafire.html |date=December 28, 2019 }}).}} which many critics assess as his best.{{citation needed|date=August 2013}} | |||

| In real life, Jack's pet name for Bess was "Mother-Girl" and Bess's for Jack was "Daddy-Boy".<ref>Stasz (2001) p. 66: "Mommy Girl and Daddy Boy"</ref> Their first child, Joan, was born on January 15th, 1901, and their second, Bessie (later called Becky), on October 20, 1902. | |||

| His landlords in Dawson were mining engineers ] and Louis Whitford Bond, educated at the Bachelor's level at the ] at ] and at the Master's level at ], respectively. The brothers' father, ], was a wealthy mining investor. While the Bond brothers were at Stanford, Hiram at the suggestion of his brother bought the New Park Estate at Santa Clara as well as a local bank. The Bonds, especially Hiram, were active ]. Marshall Bond's diary mentions friendly sparring with London on political issues as a camp pastime.{{citation needed|date=August 2013}} | |||

| Captions to pictures in photo album, reproduced in part in Joan London's memoir, "Jack London and Her Daughters", published posthumously, show Jack London's unmistakable happiness and pride in his children. But the marriage itself was under continuous strain. Kingman (1979) says that by 1903 "the breakup … was imminent …. Bessie was a fine woman, but they were extremely incompatible. There was no love left. Even companionship and respect had gone out of the marriage." Nevertheless, "Jack was still so kind and gentle with Bessie that when Cloudsley Johns was a house guest in February of 1903 he didn't suspect a breakup of their marriage."<ref>Kingman (1979) p. 121</ref> | |||

| London left Oakland with a ] and socialist leanings; he returned to become an activist for ]. He concluded that his only hope of escaping the work "trap" was to get an education and "sell his brains". He saw his writing as a business, his ticket out of poverty and, he hoped, as a means of beating the wealthy at their own game. | |||

| According to Joseph Noel (1940), "Bessie was the eternal mother. She lived at first for Jack, corrected his manuscripts, drilled him in grammar, but when the children came she lived for them. Herein was her greatest honor and her first blunder." Jack complained to Noel and George Sterling that "she's devoted to purity. When I tell her morality is only evidence of low blood pressure, she hates me. She'd sell me and the children out for her damned purity. It's terrible. Every time I come back after being away from home for a night she won't let me be in the same room with her if she can help it."<ref>Noel (1940) p. 150, "She's devoted to purity..."</ref>. Stasz believes that these were "code words for fear that was consorting with prostitutes and might bring home venereal disease."<ref>Stasz (2001) p. 80 ("devoted to purity... code words...")</ref> | |||

| On returning to California in 1898, London began working to get published, a struggle described in his novel '']'' (serialized in 1908, published in 1909). His first published story since high school was "To the Man On Trail", which has frequently been collected in anthologies.{{citation needed|date=August 2013}} When '']'' offered him only five dollars for it—and was slow paying—London came close to abandoning his writing career. In his words, "literally and literarily I was saved" when '']'' accepted his story "A Thousand Deaths" and paid him $40—the "first money I ever received for a story".{{citation needed|date=April 2012}} | |||

| On July 24th, 1903, Jack London told Bessie he was leaving and moved out; during 1904 Jack and Bess negotiated the terms of a divorce, and the decree was granted on November 11, 1904.<ref>Kingman (1979) p. 139</ref> | |||

| London began his writing career just as new printing technologies enabled lower-cost production of magazines. This resulted in a boom in popular magazines aimed at a wide public audience and a strong market for short fiction.{{citation needed|date=August 2013}} In 1900, he made $2,500 in writing, about ${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|2500|1900|r=-3}}}} in today's currency.{{citation needed|date=August 2013}} | |||

| ==Second marriage== | |||

| Among the works he sold to magazines was a short story known as either "Diable" (1902) or "Bâtard" (1904), two editions of the same basic story. London received $141.25 for this story on May 27, 1902.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.jacklondons.net/Fiction_of_jack_london/page8.html |website=JackLondons.net |access-date=August 29, 2013 |title=Footnote 55 to "Bâtard" |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110612221236/http://www.jacklondons.net/Fiction_of_jack_london/page8.html |archive-date=June 12, 2011 }} First published as "Diable – A Dog". ''The Cosmopolitan'', v. 33 (June 1902), pp. 218–26. | |||

| After divorcing Maddern in 1904, London married Charmian Kittredge in 1905. Biographer Russ Kingman called Charmian "Jack's soul-mate, always at his side, and a perfect match."<!--http://www.jacklondons.net/charmianpage.html for now, better reference later-->. | |||

| This tale was titled "Bâtard" in 1904 when included in FM. The same story, with minor changes, was also called "Bâtard" when it appeared in the ''Sunday Illustrated Magazine'' of the ''Commercial Appeal'' (Memphis, Tenn.), September 28, 1913, pp. 7–11. London received $141.25 for this story on May 27, 1902.</ref> In the text, a cruel ] brutalizes his dog, and the dog retaliates and kills the man. London told some of his critics that man's actions are the main cause of the behavior of their animals, and he would show this famously in another story, '']''.<ref> Retrieved July 22, 2015</ref> | |||

| ], ], Jack London, and ] on the beach at ], California]] | |||

| Jack had contrasted the concepts of the "Mother Woman" and the "Mate Woman" in ''The Kempton-Wace letters'''<ref name=kempton-wace>op. cit.</ref> His pet name for Bess had been "mother-girl;" his pet name for Charmian was "mate-woman."<ref>{{cite book|title=The Book of Jack London, Volume II|first = Charmian|last=London|origyear=1921|year=2003|publisher=Kessinger|id=ISBN 0766161889}} p. 59: copy of "John Barleycorn" inscribed "Dear Mate-Woman: You know. You have helped me bury the Long Sickness and the White Logic." Numerous other examples in same source.</ref> Charmian's aunt and foster mother, a disciple of ] had raised her without prudishness.<ref>Kingman (1979) p. 124</ref> Every biographer alludes to Charmian's uninhibited sexuality; Noel slyly—"a young woman named Charmian Kittredge began running out to Piedmont with foils, still masks, padded breast plates, and short tailored skirts that fitted tightly over as nice a pair of hips as one might find anywhere;" Stasz directly—"Finding that the prim and genteel lady was lustful and sexually vigorous in private was like discovering a secret treasure;"<ref>Stasz 1988 p. 112</ref>; and Kershaw coarsely—"At last, here was a woman who adored fornication, expected Jack to make her climax, and to do so frequently, and who didn't burst into tears when the sadist in him punched her in the mouth."<ref>{{cite book|first=Alex|last=Kershaw|title=Jack London: A Life|publisher=St. Martin's Press|year=1999|id=ISBN 031219904X}} p. 133</ref> | |||

| In early 1903, London sold ''The Call of the Wild'' to '']'' for $750 and the book rights to ]. Macmillan's promotional campaign propelled it to swift success.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080421154451/http://www.jacklondons.net/call.html |date=April 21, 2008 }}, excerpted from {{harvnb|Kingman|1979|p=}}</ref> | |||

| Noel (1940) calls the events from 1903 to 1905 "a domestic drama that would have intrigued the pen of an Ibsen.... London's had comedy relief in it and a sort of easy-going romance."<ref>Noel (1940) p. 146</ref> In broad outline, Jack London was restless in his marriage; sought extramarital sexual affairs; and found, in Charmian London, not only a sexually active and adventurous partner, but his future life-companion. During this time Bessie and others mistakenly perceived Anna Strunsky as her rival, while Charmian mendaciously gave Bessie the impression of being sympathetic.<!--More to come, definitely to include *references*--> | |||

| While living at his rented villa on ] in Oakland, California, London met poet ]; in time they became best friends. In 1902, Sterling helped London find a home closer to his own in nearby ]. In his letters London addressed Sterling as "Greek", owing to Sterling's ] and classical profile, and he signed them as "Wolf". London was later to depict Sterling as Russ Brissenden in his autobiographical novel ''Martin Eden'' (1910) and as Mark Hall in '']'' (1913).{{citation needed|date=August 2013}} | |||

| They attempted to have children. However, one child died at birth, and another pregnancy ended in a miscarriage. | |||

| In later life London indulged his wide-ranging interests by accumulating a personal library of 15,000 volumes. He referred to his books as "the tools of my trade".<ref>Hamilton (1986) (as cited by other sources)</ref> | |||

| ==Beauty Ranch (1910-1917)== | |||

| In 1910 Jack London purchased a 1,000 acre (4 km²) ranch in ], ] for $26,000. He wrote that "Next to my wife, the ranch is the dearest thing in the world to me." He desperately wanted the ranch to become a successful business enterprise. Writing, always a commercial enterprise with London, now became even more a means to an end: "I write for no other purpose than to add to the beauty that now belongs to me. I write a book for no other reason than to add three or four hundred acres to my magnificent estate." In May 1910 he met ] for a legendary drinking bout at the Bohemian Club's summer camp on the Russian River.{{citation needed}} After 1910, his literary works were mostly potboilers, written out of the need to provide operating income for the ranch. Joan London writes "Few reviewers bothered any more to criticize his work seriously, for it was obvious that Jack was no longer exerting himself." | |||

| == ''The Crowd'' (literary group) == | |||

| Clarice Stasz writes that London "had taken fully to heart the vision, expressed in his agrarian fiction, of the land as the closest earthly version of Eden … he educated himself through study of agricultural manuals and scientific tomes. He conceived of a system of ranching that today would be praised for its ecological wisdom." He was proud of the first concrete silo in California, of a circular piggery he designed himself. He hoped to adapt the wisdom of ] ] to the United States. | |||

| ''The Crowd'' gathered at the restaurants (including Coppa's<ref name="sfchronicle/10609139"> | |||

| * {{cite news |last1=Kamiya |first1=Gary |title=SF's first hipster cafe and its descent into ruin |url=https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/SF-s-first-hipster-cafe-and-its-descent-into-10609139.php |access-date=4 September 2023 |work=sfchronicle.com |date=November 12, 2016}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Unna |first1=Warren |title=The Coppa Murals: A Pageant of Bohemian Life in San Francisco at the Turn of the Century |date=1952 |publisher=Book Club of California |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AffEGAAACAAJ |access-date=4 September 2023 |language=en}} | |||

| * {{cite web |title=Provincial Italian Cuisines: San Francisco Conserves Italian Heritage |url=https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Provincial_Italian_Cuisines:_San_Francisco_Conserves_Italian_Heritage |website=foundsf.org - FoundSF |access-date=4 September 2023}}</ref>) at the old ]<ref>{{cite web |title=Coppa's famous walls |url=https://restaurant-ingthroughhistory.com/2015/10/29/coppas-famous-walls/ |website=Restaurant-ing through history |access-date=4 September 2023 |language=en |date=29 October 2015}}</ref><ref name="Boylan/Revolutionary-Lives-Ch1">{{cite book |last1=Boylan |first1=James R. |title=Revolutionary Lives: Anna Strunsky and William English Walling |date=1998 |publisher=University of Massachusetts Press |isbn=1-55849-164-3 |url=https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/first/b/boylan-revolutionary.html |language=en |chapter=CHAPTER ONE "Miss Annie"}}</ref> and later was a: | |||

| <blockquote>Bohemian group that often spent its Sunday afternoons picnicking, reading each other's latest compositions, gossiping about each other's infidelities and frolicking beneath the cherry boughs in the hills of ] | |||

| – Alex Kershaw, historian<ref name="paintingpiedmont/crowd">{{cite web |title=The Crowd |url=https://www.paintingpiedmont.com/crowd |website=Painting Piedmont |access-date=4 September 2023 |language=en}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| The ranch was, by most measures, a colossal failure. Sympathetic observers such as Stasz treat his projects as potentially feasible, and ascribe their failure to bad luck or to being ahead of their time. Unsympathetic observers such as Kevin Starr suggest that he was a bad manager, distracted by other concerns and impaired by his alcoholism. Starr notes that London was absent from his ranch about six months a year between 1910 and 1916, and says "He liked the show of managerial power, but not grinding attention to detail …. London's workers laughed at his efforts to play big-time rancher the operation a rich man's hobby." | |||

| Formed after 1898, they met at ]'s home on Sundays, and at Jack London's home on Wednesdays. The group usually included ] (poet) and his wife Caroline "Carrie" E. (née Rand) Sterling, ],<ref>Pratt, Norma Fain , in ''Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia''. 1 March 2009. Jewish Women's Archive. July 4, 2010.</ref> ], ], Richard Partington and his wife Blanche, Joseph Noel (dramatist, novelist and journalist),<ref name="archives.nypl/21404">{{cite web |title=Joseph Noel papers |url=https://archives.nypl.org/the/21404 |website=archives.nypl.org |access-date=4 September 2023}}</ref><ref name="nytimes/1946/08/08/joseph-noel-65">{{cite news |title=JOSEPH NOEL, 65, ONCE PLAYWRIGHT; Ex-Newspaper Man and Author Dies—Wrote Book About Jack London and Ambrose Bierce |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1946/08/08/archives/joseph-noel-65-once-playwright-exnewspaper-man-and-author-dieswrote.html |access-date=4 September 2023 |work=The New York Times |date=8 August 1946}}</ref> ], ] and the hosts, Jack London and his wife, Bessie Maddern London, and Xavier Martinez and his wife, ]. | |||

| The ranch is now a ]. | |||

| == First marriage (1900–1904) == | |||

| == Accusations of plagiarism == | |||

| ] | |||

| Jack London was accused of plagiarism at numerous times during his career. He was vulnerable, not only because he was such a conspicuous and successful writer, but also because of his methods of working. In a letter to Elwyn Hoffman he wrote "expression, you see—with me—is far easier than invention." He purchased plots for stories and novels from the young ]. And he used incidents from newspaper clippings as material on which to base stories. | |||

| ] | |||

| London married Elizabeth Mae (or May) "Bessie" Maddern on April 7, 1900, the same day ''The Son of the Wolf'' was published. Bess had been part of his circle of friends for a number of years. She was related to stage actresses ] and ]. Stasz says, "Both acknowledged publicly that they were not marrying out of love, but from friendship and a belief that they would produce sturdy children."<ref>{{harvnb|Stasz|2001|p=61}}: "Both acknowledged... that they were not marrying out of love"</ref> Kingman says, "they were comfortable together... Jack had made it clear to Bessie that he did not love her, but that he liked her enough to make a successful marriage."{{sfn|Kingman|1979|p=98}} | |||

| Egerton R. Young claimed that '']'' was taken from his book ''].'' Jack London's response was to acknowledge having used it as a source; he claimed to have written a letter to Young thanking him. | |||

| London met Bessie through his friend at Oakland High School, Fred Jacobs; she was Fred's fiancée. Bessie, who tutored at Anderson's University Academy in Alameda California, tutored Jack in preparation for his entrance exams for the University of California at Berkeley in 1896. Jacobs was killed aboard the ] in 1897, but Jack and Bessie continued their friendship, which included taking photos and developing the film together.<ref>Reesman 2010, p 12</ref> This was the beginning of Jack's passion for photography. | |||

| In July, 1902, two pieces of fiction appeared within the same month: Jack London's "]", in the ''San Francisco Argonaut,'' and ]'s "The Passing of Cock-eye Blacklock", in ''Century.'' Newspapers paralleled the stories, which London characterizes as "quite different in manner of treatment, patently the same in foundation and motive." Jack London explained that both writers had based their stories on the same newspaper account. Subsequently it was discovered that a year earlier, one Charles Forrest McLean had published another fictional story based on the same incident. | |||

| During the marriage, London continued his friendship with ], co-authoring '']'', an ] contrasting two philosophies of love. Anna, writing "Dane Kempton's" letters, arguing for a romantic view of marriage, while London, writing "Herbert Wace's" letters, argued for a scientific view, based on ] and ]. In the novel, his fictional character contrasted two women he had known.{{citation needed|date=August 2013}} | |||

| In 1906 the New York World published "deadly parallel" columns showing eighteen passages from Jack London's short story "Love of Life" side by side with similar passages from a nonfiction article by ] and ] entitled "Lost in the Land of the Midnight Sun". According to London's daughter ], the parallels " beyond question that Jack had merely rewritten the Biddle account." (Jack London would surely have objected to that word "merely".) Responding, London noted the World did not accuse him of "plagiarism", but only of "identity of time and situation", to which he defiantly "pled guilty". London acknowledged his use of Biddle, cited several other sources he had used, and stated, "I, in the course of making my living by turning journalism into literature, used material from various sources which had been collected and narrated by men who made their living by turning the facts of life into journalism." | |||

| London's pet name for Bess was "Mother-Girl" and Bess's for London was "Daddy-Boy".<ref>{{harvnb|Stasz|2001|p=66}}: "Mommy Girl and Daddy Boy"</ref> Their first child, ], was born on January 15, 1901, and their second, Bessie "Becky" (also reported as Bess), on October 20, 1902. Both children were born in ], California. Here London wrote one of his most celebrated works, ''].'' | |||

| The most serious incident involved Chapter 7 of ''],'' entitled "The Bishop's Vision." This chapter was almost identical with an ironic essay ] had published in 1901, entitled "The Bishop of London and Public Morality". Harris was incensed and suggested that he should receive 1/60th of the royalties from ''The Iron Heel,'' the disputed material constituting about that fraction of the whole novel. Jack London insisted that he had clipped a reprint of the article which had appeared in an American newspaper, and believed it to be a genuine speech delivered by the genuine Bishop of London. Joan London characterized this defense as "lame indeed".<ref>Joan London (1939), p. 326: "This time Jack attempted to defend himself rather than defy his accusers, but defiance would have served him better and been more effect, for his excuse was very lame indeed. He claimed that he had read the article in an American newspaper and that he had mistaken it for a genuine speech..."</ref> | |||

| While London had pride in his children, the marriage was strained. Kingman says that by 1903 the couple were close to separation as they were "extremely incompatible". "Jack was still so kind and gentle with Bessie that when Cloudsley Johns was a house guest in February 1903 he didn't suspect a breakup of their marriage."{{sfn|Kingman|1979|p=121}} | |||

| ==Political views== | |||

| Jack London became a socialist at the age of 20. Previously, he had possessed an optimism stemming from his health and strength, a rugged individualist who worked hard and saw the world as good. But as he details in his essay, "How I Became a Socialist", his socialist views began as his eyes were opened to the members of the bottom of the social pit. His optimism and individualism faded, and he vowed never to do more hard work than he had to. He writes that his individualism was hammered out of him, and he was reborn a socialist. London first joined the ] in April 1896. In 1901 he left the Socialist Labor Party and joined the new ]. In 1896 the ''San Francisco Chronicle'' published a story about the 20-year-old London who was out nightly in Oakland's City Hall Park, giving speeches on socialism to the crowds—an activity for which he was arrested in 1897. He ran unsuccessfully as the high-profile Socialist nominee for mayor of Oakland in 1901 (receiving 245 votes) and 1905 (improving to 981 votes), toured the country lecturing on socialism in 1906, and published collections of essays on socialism (''The War of the Classes'', 1905; ''Revolution, and other Essays'', 1910). | |||

| London reportedly complained to friends Joseph Noel and George Sterling: | |||

| He often closed his letters "Yours for the Revolution."<ref>See Labor (1994) p. 546 for one example, a letter from London to William E. Walling dated Nov. 30, 1909.</ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote |text= is devoted to purity. When I tell her morality is only evidence of low blood pressure, she hates me. She'd sell me and the children out for her damned purity. It's terrible. Every time I come back after being away from home for a night she won't let me be in the same room with her if she can help it.<ref>{{harvnb|Noel|1940|p=150}}, "She's devoted to purity..."</ref>}} | |||

| Stasz notes that "London regarded the ] as a welcome addition to the ] cause, although he never joined them in going so far as to recommend sabotage."<ref>Stasz (2001) p. 100</ref> She mentions a personal meeting between London and ] in 1912<ref>Stasz (2001) p. 156</ref> | |||

| Stasz writes that these were "code words for fear that was consorting with prostitutes and might bring home ]."<ref>{{harvnb|Stasz|2001|p=80}} ("devoted to purity... code words...")</ref> | |||

| A socialist viewpoint is evident throughout his writing, most notably in his novel '']''. No theorist or intellectual socialist, Jack London's socialism came from the heart and his life experience. | |||

| On July 24, 1903, London told Bessie he was leaving and moved out. During 1904, London and Bess negotiated the terms of a divorce, and the decree was granted on November 11, 1904.{{sfn|Kingman|1979|p=139}} | |||

| In his Glen Ellen ranch years, London felt some ambivalence toward socialism. He was an extraordinary financial success as a writer, and wanted desperately to make a financial success of his Glen Ellen ranch. He complained about the "inefficient Italian workers" in his employ. In 1916 he resigned from the Glen Ellen chapter of the Socialist Party, but stated emphatically that he did so "because of its lack of fire and fight, and its loss of emphasis on the class struggle". | |||

| == War correspondent (1904) == | |||

| In his late (1913) book ''The Cruise of the Snark'', London writes without empathy about appeals to him for membership on the Snark's crew from office workers and other "toilers" who longed for escape from the cities, and of being cheated by workmen. | |||

| London accepted an assignment of the '']'' to cover the ] in early 1904, arriving in ] on January 25, 1904. He was arrested by Japanese authorities in ], but released through the intervention of American ambassador ]. After travelling to ], he was again arrested by Japanese authorities for straying too close to the border with ] without official permission, and was sent back to ]. Released again, London was permitted to travel with the ] to the border, and to observe the ]. | |||

| London asked ], the owner of the ''San Francisco Examiner'', to be allowed to transfer to the ], where he felt that restrictions on his reporting and his movements would be less severe. However, before this could be arranged, he was arrested for a third time in four months, this time for assaulting his Japanese assistants, whom he accused of stealing the fodder for his horse. Released through the personal intervention of President ], London departed the front in June 1904.<ref>{{cite book |last=Kowner |first=Rotem |author-link=Rotem Kowner |year=2006 |title=Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War |url=https://archive.org/details/historicaldictio00libg_334 |url-access=limited |publisher=The Scarecrow Press |isbn=0-8108-4927-5 |page=}}</ref> | |||

| In an unflattering portrait of Jack London's ranch days, Kevin Starr (1973) refers to this period as "post-socialist" and says that "… by 1911 … London was more bored by the class struggle than he cared to admit." Starr maintains that London's socialism | |||

| :always had a streak of elitism in it, and a good deal of pose. He liked to play working class intellectual when it suited his purpose. Invited to a prominent Piedmont house, he featured a flannel shirt, but, as someone there remarked, London's badge of solidarity with the working class "looked as if it had been specially laundered for the occasion." "It would serve this man London right to have the working class get control of things. He would have to call out the militia to collect his royalties." | |||

| == Bohemian Club == | |||

| ==Alleged racialist views== | |||

| ] with his friends ] and ]; a painting parodies his story '']''.]] | |||

| Jack London's views regarding race are an extremely contentious subject which cannot be summed up neatly. Academics sometimes draw a distinction between the words "]", to mean a belief in intrinsic difference in the capabilities of different races, as opposed to "racist", implying prejudice or hatred. By this definition, Jack London can be said to have shared the racialism common in America in his times. | |||

| On August 18, 1904, London went with his close friend, the poet ], to "Summer High Jinks" at the ]. London was elected to honorary membership in the ] and took part in many activities. Other noted members of the Bohemian Club during this time included ], ], ], ], ],{{citation needed|date=August 2013}} and ]. | |||

| Many of Jack London's short stories are notable for their empathetic portrayal of Mexicans (''The Mexican''), Asian (''The Chinago,'') and Hawaiian (''Koolau the Leper'') characters. But, unlike, say, ], Jack London did not depart from the racialist views that were the norm in American society in his time, and he shared the typical California concerns about Asian immigration and "]" (which he actually used as the title of an essay he wrote in 1904); on the other hand, his war correspondence from the Russo-Japanese War, as well as his unfinished novel "Cherry", show that he greatly admired much about Japanese' customs and capabilities. | |||

| Beginning in December 1914, London worked on ''The Acorn Planter, A California Forest Play'', to be performed as one of the ], but it was never selected. It was described as too difficult to set to music.{{sfn|London|Taylor|1987|p=}} London published ''The Acorn Planter'' in 1916.{{sfn|Wichlan|2007|p=}} | |||

| To compare London with the contemporary norms, consider this statement by ], writing in 1901, in ''Anticipations," | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| And for the rest, those swarms of black, and brown, and dirty-white, and yellow people, who do not come into the new needs of efficiency? Well, the world is a world, not a charitable institution, and I take it they will have to go. | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| == Second marriage == | |||

| Now, consider the lines spoken by the character Frona Welse in London's 1902 novel, ''Daughter of the Snows.'' (Scholar Andrew Furer, in a long essay exploring the complexity of London's racialism, says there is no doubt that Frona Welse is here acting as a mouthpiece for London): | |||

| ]]] | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| We are a race of doers and fighters, of globe-encirclers and zone-conquerors …. While we are persistent and resistant, we are made so that we fit ourselves to the most diverse conditions. Will the Indian, the Negro, or the Mongol ever conquer the ]? Surely not! The Indian has persistence without variability; if he does not modify he dies, if he does try to modify he dies anyway. The Negro has adaptability, but he is servile and must be led. As for the Chinese, they are permanent. All that the other races are not, the Anglo-Saxon, or Teuton if you please, is. All that the other races have not, the Teuton has. | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| After divorcing Maddern, London married ] in 1905. London had been introduced to Kittredge in 1900 by her aunt ], who was an editor at ''Overland Monthly'' magazine in San Francisco. The two met prior to his first marriage but became lovers years later after Jack and Bessie London visited Wake Robin, Netta Eames' Sonoma County resort, in 1903. London was injured when he fell from a buggy, and Netta arranged for Charmian to care for him. The two developed a friendship, as Charmian, Netta, her husband Roscoe, and London were politically aligned with socialist causes. At some point the relationship became romantic, and Jack divorced his wife to marry Charmian, who was five years his senior.<ref>Labor 2013</ref> | |||

| Jack London's 1904 essay, '''', is replete with the casual stereotyping that was common at the time: "The Korean is the perfect type of inefficiency — of utter worthlessness. The Chinese is the perfect type of industry;" "The Chinese is no coward;" "would not of himself constitute a Brown Peril …. The menace to the Western world lies, not in the little brown man; but in the four hundred millions of yellow men should the little brown man undertake their management." He insists that: | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| Back of our own great race adventure, back of our robberies by sea and land, our lusts and violences and all the evil things we have done, there is a certain integrity, a sternness of conscience, a melancholy responsibility of life, a sympathy and comradeship and warm human feel, which is ours, indubitably ours … | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| Yet even within this essay Jack London's inconsistency on the issue makes itself clear. After insisting that "our own great race adventure" has an ethical dimension, he closes by saying | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| it must be taken into consideration that the above postulate is itself a product of Western race-egotism, urged by our belief in our own righteousness and fostered by a faith in ourselves which may be as erroneous as are most fond race fancies. | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| Biographer Russ Kingman called Charmian "Jack's soul-mate, always at his side, and a perfect match."<!--http://www.jacklondons.net/charmianpage.html for now, better reference later--> Their time together included numerous trips, including a 1907 cruise on the yacht '']'' to Hawaii and Australia.<ref>"The Sailing of the Snark", by ], ''Sunset'', May 1907.</ref> Many of London's stories are based on his visits to Hawaii, the last one for 10 months beginning in December 1915.{{sfn|Day|1996|pp=113–19}} | |||

| In "Koolau the Leper", London has one of his characters remark: | |||

| The couple also visited ], Nevada, in 1907, where they were guests of the Bond brothers, London's Dawson City landlords. The Bond brothers were working in Nevada as mining engineers. | |||

| :Because we are sick take away our liberty. We have obeyed the law. We have done no wrong. And yet they would put us in prison. Molokai is a prison. . . . It is the will of the white men who rule the land. . . . They came like lambs, speaking softly. . . . To-day all the islands are theirs. | |||

| London had contrasted the concepts of the "Mother Girl" and the "Mate Woman" in ''The Kempton-Wace Letters''. His pet name for Bess had been "Mother-Girl"; his pet name for Charmian was "Mate-Woman".<ref>{{harvnb|London|2003|p=59}}: copy of "John Barleycorn" inscribed "Dear Mate-Woman: You know. You have helped me bury the Long Sickness and the White Logic." Numerous other examples in same source.</ref> Charmian's aunt and foster mother, a disciple of ], had raised her without prudishness.{{sfn|Kingman|1979|p=124}} Every biographer alludes to Charmian's uninhibited sexuality.{{sfn|Stasz|1999|p=112}}{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=133}} | |||

| London describes Koolau, who is a Hawaiian leper—and thus a very different sort of "superman" than Martin Eden—and who fights off an entire cavalry troop to elude capture, as "indomitable spiritually—a . . . magnificent rebel". | |||

| ] | |||

| An avid boxer and amateur boxing fan, London was a sort of celebrity reporter on the 1910 ]-] fight, in which a black boxer vanquished ], the "Great White Hope". Earlier, he had written: | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| ] must now emerge from his Alfalfa farm and remove that golden smile from Jack Johnson's face … Jeff, it's up to you. The White Man must be rescued. | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| Joseph Noel calls the events from 1903 to 1905 "a domestic drama that would have intrigued the pen of an ].... London's had comedy relief in it and a sort of easy-going romance."{{sfn|Noel|1940|p=146}} In broad outline, London was restless in his first marriage, sought extramarital sexual affairs, and found, in Charmian Kittredge, not only a sexually active and adventurous partner, but his future life-companion. They attempted to have children; one child died at birth, and another pregnancy ended in a miscarriage.<ref>{{cite book|editor-first1=Dale|editor-last1=Walker |editor-first2=Jeanne|editor-last2=Reesman |title=No Mentor But Myself: Jack London on Writers and Writing|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kU7CjupoZGsC&pg=PA213 |chapter=A Selection of Letters to Charmain Kittredge |date=1999 |publisher=Stanford University Press |isbn=0804736367 |access-date=July 8, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Earlier in his boxing journalism, however, in 1908, according to Furer, London praised Johnson highly, contrasting the black boxer's coolness and intellectual style, with the apelike appearance and fighting style of his *white* opponent, Tommy Burns: "what . . . on Saturday was bigness, coolness, quickness, cleverness, and vast physical superiority... Because a white man wishes a white man to win, this should not prevent him from giving absolute credit to the best man, even when that best man was black. All hail to Johnson." Johnson was "superb. He was impregnable . . . as inaccessible as Mont Blanc." | |||

| In 1906, London published in '']'' magazine his eye-witness report of the ].<ref>. California Department of Parks & Recreation.</ref> | |||

| It is possible to cherry-pick statements by some of Jack London's fictional characters that would today be characterized as "racist" (the word did not exist in London's time). Such statements occur increasingly in the potboilers he wrote to finance his ranch in his declining years. The reader must decide whether or not London places any ironic distance between himself and these characters. The word ''nigger'' is used casually throughout the novels ''Adventure,'' ''Jerry of the Islands,'' and ''Michael, Brother of Jerry.'' | |||

| == Beauty Ranch (1905–1916) == | |||

| A passage from ''Jerry of the Islands'' depicts a dog as perceiving white man's superiority: | |||

| In 1905, London purchased a {{convert|1000|acre|km2}} ranch in ], ], California, on the eastern slope of ].<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uuMtEHq3Nu8C&pg=PA102 |last=Stasz |first=Clarice |title=Jack London's Women |page=102 |publisher=University of Massachusetts Press |isbn=978-1625340658 |year=2013 |access-date=July 8, 2019}}</ref> He wrote: "Next to my wife, the ranch is the dearest thing in the world to me." He desperately wanted the ranch to become a successful business enterprise. Writing, always a commercial enterprise with London, now became even more a means to an end: "I write for no other purpose than to add to the beauty that now belongs to me. I write a book for no other reason than to add three or four hundred acres to my magnificent estate." | |||

| :''He was that inferior man-creature, a nigger, and Jerry had been thoroughly trained all his brief days to the law that the white men were the superior two-legged gods.'' (pg 98). | |||

| ] | |||

| ''Micahel, Brother of Jerry'' features a comic Jewish character who is avaricious, stingy, and has a "greasy-seaming grossness of flesh". | |||

| Stasz writes that London "had taken fully to heart the vision, expressed in his ] fiction, of the land as the closest earthly version of ] ... he educated himself through the study of agricultural manuals and scientific tomes. He conceived of a system of ranching that today would be praised for its ]."<ref name="American dreamers: Charmian and Jack London">{{cite book |last=Stasz |first=Clarice |title=American Dreamers: Charmian and Jack London |date=1 January 1988 |publisher=St. Martin's Press |isbn=0-312-021607 |page=250 |url=https://archive.org/details/americandreamers00stas/page/250/mode/2up |access-date=9 December 2023}}</ref> He was proud to own the first concrete ] in California. He hoped to adapt the wisdom of Asian ] to the United States. He hired both Italian and Chinese stonemasons, whose distinctly different styles are obvious. | |||

| Those who defend Jack London against charges of racism like to cite the letter he wrote to the Japanese-American Commercial Weekly in 1913: | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| In reply to yours of August 16,1913. First of all, I should say by stopping the stupid newspaper from always fomenting race prejudice. This of course, being impossible, I would say, next, by educating the people of Japan so that they will be too intelligently tolerant to respond to any call to race prejudice. And, finally, by realizing, in industry and government, of socialism—which last word is merely a word that stands for the actual application of in the affairs of men of the theory of the Brotherhood of Man. | |||

| <br></br> | |||

| In the meantime the nations and races are only unruly boys who have not yet grown to the stature of men. So we must expect them to do unruly and boisterous things at times. And, just as boys grow up, so the races of mankind will grow up and laugh when they look back upon their childish quarrels.<ref>Labor, Earle, Robert C. Leitz, III, and I. Milo Shepard: ''The Letters of Jack London: Volume Three: 1913-1916'' Stanford University Press 1988. p. 1219, Letter to Japanese-American Commercial Weekly, August 25, 1913: "the races of mankind will grow up and laugh their childish quarrels…"</ref> | |||

| The ranch was an economic failure. Sympathetic observers such as Stasz treat his projects as potentially feasible, and ascribe their failure to bad luck or to being ahead of their time. Unsympathetic historians such as ] suggest that he was a bad manager, distracted by other concerns and impaired by his alcoholism. Starr notes that London was absent from his ranch about six months a year between 1910 and 1916 and says, "He liked the show of managerial power, but not grinding attention to detail .... London's workers laughed at his efforts to play big-time rancher the operation a rich man's hobby."<ref>Starr, Kevin. . Oxford University, 1986.</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| London spent $80,000 (${{Formatnum:{{Inflation|US|80000|1905|r=-4}}}} in current value) to build a {{convert|15000|sqft|m2|adj=on}} stone mansion called ] on the property. Just as the mansion was nearing completion, two weeks before the Londons planned to move in, it was destroyed by fire. | |||

| ==Death== | |||

| ] | |||

| Jack London's death is controversial. Many older sources describe it as a suicide, and some still do.<ref> ] , entry for Jack London: "Beset in his later years by alcoholism and financial difficulties, London committed suicide at the age of 40."</ref> However, this appears to be at best a rumor, or speculation based on incidents in his fiction writings. His death certificate gives the cause as ], also known as uremic poisoning. He died November 22, 1916. It is known he was in extreme pain and taking ], and it is possible that a morphine overdose, accidental or deliberate, may have contributed. Clarice Stasz, in a capsule biography, writes "Following London's death, for a number of reasons a biographical myth developed in which he has been portrayed as an alcoholic womanizer who committed suicide. Recent scholarship based upon firsthand documents challenges this caricature."<ref>Stasz, Clarice (2001). "Jack (John Griffith) London." </ref> | |||

| London's last visit to Hawaii,<ref name="TherouxSpiritOfAloha">{{cite web |url=http://www.spiritofaloha.com/features/0307/writehawaii.html |title=They Came to Write in Hawai'i |author=Joseph Theroux |work=Spirit of Aloha (]) March/April 2007 |quote=He said, "Life's not a matter of holding good cards, but sometimes playing a poor hand well." ...His last magazine piece was titled "My Hawaiian Aloha"<big>*</big> his final, unfinished novel, ''Eyes of Asia,'' was set in Hawai'i. |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080121211749/http://www.spiritofaloha.com/features/0307/writehawaii.html |archive-date=January 21, 2008 }} ({{cite web |url=http://www.spiritofaloha.com/features/0307/aloha.html |title=My Hawaiian Aloha |author=Jack London |work=<big>*</big>From Stories of Hawai'i, Mutual Publishing, ], 1916. Reprinted with permission in Spirit of Aloha, November/December 2006 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080121211719/http://www.spiritofaloha.com/features/0307/aloha.html |archive-date=January 21, 2008 }})</ref> beginning in December 1915, lasted eight months. He met with ], ], ] and many others, before returning to his ranch in July 1916.{{sfn|Day|1996|pp=113–19}} He was suffering from ], but he continued to work. | |||

| Suicide does figure in London's writing. In his autobiographical novel '']'', the protagonist commits suicide by drowning. In his autobiographical memoir '']'', he claims, as a youth, having drunkenly stumbled overboard into the San Francisco Bay, "some maundering fancy of going out with the tide suddenly obsessed me", and drifted for hours intending to drown himself, nearly succeeding before sobering up and being rescued by fishermen. An even closer parallel occurs in the denouement of ''],'' in which the heroine, confronted by the pain of a mortal and untreatable gunshot wound, undergoes a physician-assisted suicide by means of morphine. These accounts in his writings probably contributed to the "biographical myth". | |||

| The ranch (abutting stone remnants of Wolf House) is now a ] and is protected in ]. | |||

| == |

== Animal activism == | ||

| London witnessed animal cruelty in the training of circus animals, and his subsequent novels '']'' and '']'' included a foreword entreating the public to become more informed about this practice.<ref>{{cite book |last=Beers |first=Diane L. |title=For the Prevention of Cruelty: The History and Legacy of Animal Rights Activism in the United States |url=https://archive.org/details/forpreventionofc00dian_0 |url-access=registration |year=2006 |publisher=Swallow Press/Ohio University Press |location=Athens |isbn=0804010870 |pages=}}</ref> In 1918, the ] and the American Humane Education Society teamed up to create the Jack London Club, which sought to inform the public about cruelty to circus animals and encourage them to protest this establishment.<ref>{{cite book |last=Beers |first=Diane L. |title=For the Prevention of Cruelty: The History and Legacy of Animal Rights Activism in the United States |url=https://archive.org/details/forpreventionofc00dian_0 |url-access=registration |year=2006 |publisher=Swallow Press/Ohio University Press |location=Athens |isbn=0804010870 |pages=}}</ref> Support from Club members led to a temporary cessation of trained animal acts at ] in 1925.<ref>{{cite book |last=Beers |first=Diane L. |title=For the Prevention of Cruelty: The History and Legacy of Animal Rights Activism in the United States |url=https://archive.org/details/forpreventionofc00dian_0 |url-access=registration |year=2006 |publisher=Swallow Press/Ohio University Press |location=Athens |isbn=0804010870 |page=}}</ref> | |||

| ===Short stories=== | |||

| Western writer and historian Dale L. Walker writes: | |||

| :London's true métier was the short story …. London's true genius lay in the short form, 7,500 words and under, where the flood of images in his teeming brain and the innate power of his narrative gift were at once constrained and freed. His stories that run longer than the magic 7,500 generally—but certainly not always—could have benefited from self-editing. | |||

| == Death == | |||

| London's "strength of utterance" is at its height in his stories, and they are painstakingly well-constructed. (In contrast, many of his novels, including ''The Call of the Wild'', are weakly constructed, episodic, and resemble linked sequences of short stories). | |||

| ] | |||

| London died November 22, 1916, in a ] in a cottage on his ranch. London had been a robust man but had suffered several serious illnesses, including ] in the Klondike.<ref>{{cite news |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0112.html |title=On This Day: November 23, 1916: Obituary – Jack London Dies Suddenly On Ranch |access-date=January 6, 2014}}</ref> Additionally, during travels on the ''Snark'', he and Charmian picked up unspecified tropical infections and diseases, including ].<ref>{{cite book |author=Jack London |title=The Cruise of the Snark |url=https://archive.org/details/cruisesnark01londgoog |year=1911 |publisher=Macmillan}}</ref> At the time of his death, he suffered from ], late-stage alcoholism, and ];<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://contentdm.marinlibrary.org/digital/collection/npmct/id/7321 |title=Marin County Tocsin |website=contentdm.marinlibrary.org |access-date=July 26, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190726181750/https://contentdm.marinlibrary.org/digital/collection/npmct/id/7321 |archive-date=July 26, 2019 |url-status=dead }}</ref> he was in extreme pain and taking ] and ], both common ]s at the time.<ref>{{Cite web |last=McConahey |first=Meg |date=July 22, 2022 |title=Was Jack London a drug addict? New technology examines old mysteries |url=https://www.pressdemocrat.com/article/lifestyle/new-technology-examines-old-jack-london-mysteries/ |access-date=August 7, 2022 |website=Santa Rosa Press Democrat |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| "]" is the best known of all his stories. It tells the story of a new arrival to the Klondike who stubbornly ignores warnings about the folly of travelling alone. He falls through the ice into a creek in fifty-below weather, and his survival depends on being able to build a fire and dry his clothes, which he is unable to do. The famous version of this story was published in 1908. Jack London published an earlier and radically different version in 1902, and a comparison of the two provides a dramatic illustration of the growth of his literary ability. Labor (1994) in an anthology says that "To compare the two versions is itself an instructive lesson in what distinguished a great work of literary art from a good children's story."<ref>Both versions are online: ; </ref> | |||