| Revision as of 20:45, 26 June 2015 editScientus (talk | contribs)5,503 edits Undid revision 668814771 by TJRC (talk)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:12, 9 January 2025 edit undoDMacks (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Administrators186,593 editsm Reverted edit by 2001:FB1:14F:3ACB:947C:99FF:771F:F306 (talk) to last version by RemsenseTag: Rollback | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Latin-script alphabet consisting of 26 letters}} | |||

| The modern '''English alphabet''' is a ] consisting of 26 ] (each having an uppercase and a lowercase form) – the same letters that are found in the ]: | |||

| {{Infobox writing system | |||

| <center> | |||

| | name = English alphabet | |||

| {|class="wikitable" style="border-collapse:collapse;" | |||

| | type = ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | languages = ] | |||

| | time = {{circa|16th century}}{{snd}}present | |||

| | fam1 = (]) | |||

| | fam2 = ] | |||

| | fam3 = ] | |||

| | fam4 = ] | |||

| | fam5 = ] | |||

| | fam6 = ] | |||

| | fam7 = ] | |||

| | children = {{ubl|]|]|]|]|]}} | |||

| | sample = Dax sample.png | |||

| | imagesize = 200px | |||

| | unicode = Basic Latin | |||

| | iso15924 = Latn | |||

| | caption = An English-language ] written with the ] Regular typeface | |||

| }} | |||

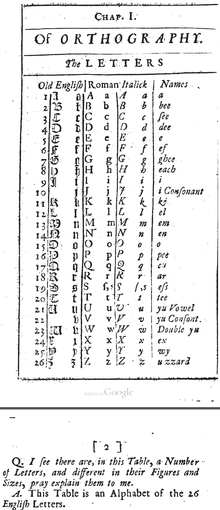

| ] is written with a ] consisting of 26 ], with each having both ] forms. The word ''alphabet'' is a ] of '']'' and '']'', the names of the first two letters in the ]. ] was first written down using the ] during the 7th century. During the centuries that followed, various letters entered or fell out of use. By the 16th century, the present set of 26 letters had largely stabilised: | |||

| |width=3% align="center"|1||width=3% align="center"|2 | |||

| |width=3% align="center"|3||width=3% align="center"|4 | |||

| |width=3% align="center"|5||width=3% align="center"|6 | |||

| |width=3% align="center"|7||width=3% align="center"|8 | |||

| |width=3% align="center"|9||width=3% align="center"|10 | |||

| |width=3% align="center"|11||width=3% align="center"|12 | |||

| |width=3% align="center"|13||width=3% align="center"|14 | |||

| |width=3% align="center"|15||width=3% align="center"|16 | |||

| |width=3% align="center"|17||width=3% align="center"|18 | |||

| |width=3% align="center"|19||width=3% align="center"|20 | |||

| |width=3% align="center"|21||width=3% align="center"|22 | |||

| |width=3% align="center"|23||width=3% align="center"|24 | |||

| |width=3% align="center"|25||width=3% align="center"|26 | |||

| |- | |||

| |bgcolor="#EFEFEF" align="center" colspan="26" | ''']''' (also called '''uppercase''' or '''capital letters''') | |||

| |- | |||

| |width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|]||width=3% align="center"|] | |||

| |- | |||

| |bgcolor="#EFEFEF" align="center" colspan="26" | ''']''' (also called '''lowercase''' or '''small letters''') | |||

| |- | |||

| |align="center"|a||align="center"|b||align="center"|c||align="center"|d||align="center"|e||align="center"|f||align="center"|g||align="center"|h||align="center"|i||align="center"|j||align="center"|k||align="center"|l||align="center"|m||align="center"|n||align="center"|o||align="center"|p||align="center"|q||align="center"|r||align="center"|s||align="center"|t||align="center"|u||align="center"|v||align="center"|w||align="center"|x||align="center"|y||align="center"|z | |||

| |} | |||

| </center> | |||

| The exact shape of printed letters varies depending on the ]. The shape of ] letters can differ significantly from the standard printed form (and between individuals), especially when written in ] style. See the individual letter articles for information about letter shapes and origins (follow the links on any of the uppercase letters above). | |||

| {{Flatlist|indent=1| | |||

| Written English uses a number of ], such as ''ch, sh, th, ph, wh,'' etc., but they are not considered separate letters of the alphabet. Some traditions{{which|date=December 2014}} also use two ], '']'' and '']'',<ref group=nb>See also the section on ]</ref> or consider the ] (&) part of the alphabet. | |||

| * {{nwr|] a}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] b}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] c}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] d}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] e}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] f}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] g}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] h}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] i}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] j}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] k}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] l}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] m}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] n}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] o}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] p}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] q}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] r}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] s}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] t}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] u}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] v}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] w}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] x}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] y}} | |||

| * {{nwr|] z}} | |||

| }} | |||

| There are 5 vowel letters and 19 consonant letters—as well as Y and W, which may function as either type. | |||

| Written English has a large number of ], such as {{angbr|ch}}, {{angbr|ea}}, {{angbr|oo}}, {{angbr|sh}}, and {{angbr|th}}. ]s are generally not used to write native English words, which is unusual among orthographies used to write the ]. | |||

| ==Letter names<span class="anchor" id="Alphabet letter names"></span>== | |||

| ].]] | |||

| {{Listen | {{Listen | ||

| |filename = Alphabet.oga | |filename = Alphabet.oga | ||

| |title = English alphabet | |title = English alphabet | ||

| | |

|type = speech | ||

| |description = A ] ] speaker reciting the English alphabet | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The names of the letters are commonly spelled out in compound words and initialisms (e.g., ''tee-shirt, deejay, emcee, okay,'' etc.), derived forms (e.g., ''exed out,{{efn|Clicked the 🅇 box to close a tab or app}} effing,{{efn|Fucking}} to eff and blind, {{notatypo|aitchless}}'',{{efn|Without the letter H}} etc.), and objects named after letters (e.g., '']'' and '']'' in printing, and '']'' in railroading). The spellings listed below are from the ]. Plurals of consonant names are formed by adding ''-s'' (e.g., ''bees'', ''efs'' or ''effs'', ''ems'') or ''-es'' in the cases of ''aitches'', ''esses'', ''exes''. Plurals of vowel names also take ''-es'' (i.e., ''aes'', ''ees'', ''ies'', ''oes'', ''ues''), but these are rare. For a letter as a letter, the letter itself is most commonly used, generally in capitalised form, in which case the plural just takes ''-s'' or ''-'s'' (e.g. ''Cs'' or ''c's'' for ''cees''). | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{See also|History of the Latin alphabet|English orthography}} | |||

| ===Old English=== | |||

| {{main|Old English Latin alphabet}} | |||

| The ] was first written in the ] runic alphabet, in use from the 5th century. This alphabet was brought to what is now England, along with the proto-form of the language itself, by ] settlers. Very few examples of this form of written Old English have survived, these being mostly short inscriptions or fragments | |||

| The ], introduced by Christian missionaries, began to replace the Anglo-Saxon futhorc from about the 7th century, although the two continued in parallel for some time. Futhorc influenced the emerging English alphabet by providing it with the letters '']'' (Þ þ) and '']'' ({{unicode|Ƿ}} {{unicode|ƿ}}). The letter '']'' (Ð ð) was later devised as a modification of '']'' (D d), and finally '']'' ({{lang|ang|Ȝ}} {{lang|ang|ȝ}}) was created by Norman scribes from the ] in Old English and ], and used alongside their ]. | |||

| The a-e ] '']'' (Æ æ) was adopted as a letter its own right, named after a futhorc rune '']''. In very early Old English the o-e ligature '']'' (Œ œ) also appeared as a distinct letter, likewise named after a rune, '']''{{citation_needed|date=March 2014}}. Additionally, the v-v or u-u ligature '']'' (W w) was in use. | |||

| In the year 1011, a monk named ] recorded the traditional order of the Old English alphabet.<ref name="Evertype">Michael Everson, Evertype, Baldur Sigurðsson, Íslensk Málstöð, ''''</ref> He listed the 24 letters of the Latin alphabet first (including ]), then 5 additional English letters, starting with the ] ''ond'' ({{Unicode|⁊}}) an insular symbol for ''and'': | |||

| :{{Unicode|A B C D E F G H I K L M N O P Q R S T V X Y Z & ⁊ Ƿ Þ Ð Æ}} | |||

| ===Modern English=== | |||

| In the ] of ], ] (þ), ] (ð), ] ({{unicode|ƿ}}), ] ({{lang|ang|ȝ}}), ] (æ), and ] (œ) are obsolete. ] borrowings reintroduced homographs of ash and ethel into ] and ], though they are not considered to be the same letters{{Citation needed|date=January 2011}} but rather ], and in any case are somewhat old-fashioned. Thorn and eth were both replaced by '']'', though thorn continued in existence for some time, its lowercase form gradually becoming graphically indistinguishable from the ] ] in most handwriting. ''Y'' for ''th'' can still be seen in pseudo-archaisms such as "Ye Olde Booke Shoppe". The letters þ and ð are still used in present-day ] whereas ð is still used in present-day ]. Wynn disappeared from English around the 14th century when it was supplanted by ''uu'', which ultimately developed into the modern ''w''. Yogh disappeared around the 15th century and was typically replaced by ''gh''. | |||

| The letters '']'' and '']'', as distinct from '']'' and '']'', were introduced in the 16th century, and ''w'' assumed the status of an independent letter, so that the English alphabet is now considered to consist of the following 26 letters: | |||

| :A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z | |||

| The variant lowercase form ] ({{Unicode|ſ}}) lasted into ], and was used in non-final position up to the early 19th century. | |||

| ===Ligatures in recent usage=== | |||

| Outside of professional papers on specific subjects that traditionally use ligatures in ]s, ligatures are seldom used in modern English. | |||

| The ligatures '']'' and '']'' were until the 19th century (slightly later in American English){{fact|date=December 2014}} used in formal writing for certain words of Greek or Latin origin, such as '']'' and '']'', although such ligatures were not used in either classical Latin or ancient Greek. These are now usually rendered as "ae" and "oe" in all types of writing,{{fact|date=December 2014}} although in American English, a lone ''e'' has mostly supplanted both (for example, ''encyclopedia'' for ''encyclopaedia'', and ''fetus'' for ''foetus''). | |||

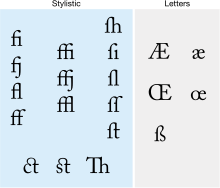

| Some ] for typesetting English contain commonly used ligatures, such as for {{angle bracket|tt}}, {{angle bracket|fi}}, {{angle bracket|fl}}, {{angle bracket|ffi}}, and {{angle bracket|ffl}}. These are not independent letters, but rather ]. | |||

| ==Proposed reforms== | |||

| Alternative scripts have been proposed for written English – | |||

| mostly ] – | |||

| such as the ], the ], ], ], <ref></ref>, etc. | |||

| ==Diacritics== | |||

| {{Main|English terms with diacritical marks}} | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=June 2011}} | |||

| ] marks mainly appear in loanwords such as ''naïve'' and ''façade''. As such words become naturalised In English, there is a tendency to drop the diacritics, as has happened with old borrowings such as ''hôtel'', from French. Informal English writing tends to omit diacritics because of their absence from the keyboard, while professional copywriters and typesetters tend to include them. Words that are still perceived as foreign tend to retain them; for example, the only spelling of ''soupçon'' found in English dictionaries (the ] and others) uses the diacritic. Diacritics are also more likely to be retained where there would otherwise be confusion with another word (for example, ''résumé'' rather than ''resume''), and, rarely, even added (as in ''maté'', from Spanish '']'', but following the pattern of ''café'', from French). | |||

| Occasionally, especially in older writing, diacritics are used to indicate the ]s of a word: ''cursed'' (verb) is pronounced with one syllable, while ''cursèd'' (]) is pronounced with two. ''È'' is used widely in poetry, e.g. in Shakespeare's sonnets. Similarly, while in ''chicken coop'' the letters ''-oo-'' represent a single vowel sound (a ]), in obsolete spellings such as ''zoölogist'' and ''coöperation'', they represent two. This use of the ] is rarely seen, but persists into the 2000s in some publications, such as '']''. | |||

| An acute, grave or diaeresis may also be placed over an "e" at the end of a word to indicate that it is not silent, as in ''saké''. In general, these devices are often not used even where they would serve to alleviate some degree of confusion. | |||

| ==Ampersand== | |||

| The ] has sometimes appeared at the end of the English alphabet, as in Byrhtferð's list of letters in 1011.<ref name="Evertype">Michæl Everson, Evertype, Baldur Sigurðsson, Íslensk Málstöð </ref> Historically, the figure is a ] for the letters ''Et''. In English and many other languages it is used to represent the word ''and'' and occasionally the Latin word ''et'', as in the abbreviation ''&c'' (et cetera).<!---and is used for other purposes, too. & is on a normal keyboard with the combo SHIFT + 7---> | |||

| ==Apostrophe== | |||

| The ], while not considered part of the English alphabet, is used to abbreviate English words. A few pairs of words, such as ''its'' (belonging to ''it'') and ''it's'' (''it is'' or ''it has''), ''were'' (plural of ''was'') and ''we're'' (we are), and ''shed'' (to get rid of) and ''she'd'' (''she would'' or ''she had'') are distinguished in writing only by the presence or absence of an apostrophe. The apostrophe also distinguishes the ] endings ''-'s'' and ''-s{'}'' from the common ] ending ''-s'', a practice introduced in the 18th century; before, all three endings were written ''-s'', which could lead to confusion (as in, ''the Apostles words'').<ref>{{cite web|url=http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/apostrophe?s=t|title=''Apostrophe'' Definition|publisher=]|accessdate=14 June 2015}}</ref> | |||

| ==Letter names== | |||

| The names of the letters are rarely spelled out, except when used in derivations or compound words (for example ''tee-shirt, deejay, emcee, okay, aitchless, wye-level'', etc.), derived forms (for example ''exed out, effing, to eff and blind'', etc.), and in the names of objects named after letters (for example ''em (space)'' in printing and ''wye (junction)'' in railroading). The forms listed below are from the ]. Vowels stand for themselves, and consonants usually have the form ''consonant + ee'' or ''e + consonant'' (e.g. ''bee'' and ''ef''). The exceptions are the letters ''aitch, jay, kay, cue, ar, ess'' (but ''es-'' in compounds ), ''wye'', and ''zed''. Plurals of consonants end in ''-s'' (''bees, efs, ems'') or, in the cases of ''aitch, ess'', and ''ex'', in ''-es'' (''aitches, esses, exes''). Plurals of vowels end in ''-es'' (''aes, ees, ies, oes, ues''); these are rare. Of course, all letters may stand for themselves, generally in capitalized form (''okay'' or ''OK'', ''emcee'' or ''MC''), and plurals may be based on these (''aes'' or ''As'', ''cees'' or ''Cs'', etc.'') | |||

| <!-- Note: These are the *names of the letters*, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. They are not pronunciation guides. Please don't change "cee" (the correct spelling) to "see", or "i" to "eye". --> | <!-- Note: These are the *names of the letters*, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. They are not pronunciation guides. Please don't change "cee" (the correct spelling) to "see", or "i" to "eye". --> | ||

| {| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

| ! Letter !! |

! rowspan="2"|Letter !! colspan="2" | Name !! colspan="4" |Name pronunciation | ||

| ! rowspan="2" | {{Tooltip|Freq.|Frequency}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| !Modern<br/>English<ref>''The Oxford English Dictionary,'' 2nd edition.</ref> | |||

| | ] || ''a''<!--No, not "ay" and "ai", unless you have a citation--> || {{IPA|/ˈeɪ/}}, {{IPA|/æ/}}<ref group=nb>often in ], due to the letter's pronunciation in the ]</ref> | |||

| !Latin | |||

| !] | |||

| !Latin | |||

| !Old<br/>French | |||

| !Middle<br/>English | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''a''<!--No, not "ay" and "ai", unless you have a citation--> | |||

| | ] || ''bee'' || {{IPA|/ˈbiː/}} | |||

| |''ā''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|eɪ}}, {{IPAc-en|ˈ|æ}}{{efn|often in ], due to the letter's pronunciation in the ]}} | |||

| |/aː/ | |||

| |/aː/ | |||

| |/aː/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|8.17% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''bee'' | |||

| | ] || ''cee''<!--No, not "see", unless you have a citation--> || {{IPA|/ˈsiː/}} | |||

| |''bē''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|b|iː}} | |||

| |/beː/ | |||

| |/beː/ | |||

| |/beː/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|1.49% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''cee''<!--No, not "see", unless you have a citation--> | |||

| | ] || ''dee'' || {{IPA|/ˈdiː/}} | |||

| |''cē''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|s|iː}} | |||

| |/keː/ | |||

| |/tʃeː/ > /tseː/<br/>> /seː/ | |||

| |/seː/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|2.78% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''dee'' | |||

| | ] || ''e''<!--No, not "ee", unless you have a citation--> || {{IPA|/ˈiː/}} | |||

| |''dē''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|d|iː}} | |||

| |/deː/ | |||

| |/deː/ | |||

| |/deː/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|4.25% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || '' |

| ] || ''e''<!--No, not "ee", unless you have a citation--> | ||

| |''ē''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|iː}} | |||

| |/eː/ | |||

| |/eː/ | |||

| |/eː/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|12.70% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || '' |

| ] || ''ef'', ''eff'' | ||

| |''ef''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɛ|f}} | |||

| |/ɛf/ | |||

| |/ɛf/ | |||

| |/ɛf/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;" |2.23% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''gee'' | |||

| | ''gē'' || {{IPAc-en|ˈ|dʒ|iː}} | |||

| | /ɡeː/ | |||

| | /dʒeː/ | |||

| | /dʒeː/ | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"|2.02% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | rowspan="2" | ] || ''aitch'' | |||

| | ''haitch''<ref group=nb>mostly in ], sometimes in Australian English, and usually in Indian English (although often considered incorrect)</ref>|| {{IPA|/ˈheɪtʃ/}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" |''hā''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|eɪ|tʃ}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" |/haː/ > /ˈaha/<br/>> /ˈakːa/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" |/ˈaːtʃə/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" |/aːtʃ/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" style="text-align:right;"|6.09% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | '' |

| ''haitch''{{efn|The usual form in ] and Australian English}}|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|h|eɪ|tʃ}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || '' |

| ] || ''i'' | ||

| |''ī''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|aɪ}} | |||

| |/iː/ | |||

| |/iː/ | |||

| |/iː/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|6.97% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | rowspan="2" | ] || ''jay'' |

| rowspan="2" | ] || ''jay'' | ||

| | rowspan="2" |–|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|dʒ|eɪ}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" |– | |||

| | rowspan="2" |– | |||

| | rowspan="2" |{{efn|The letter J did not occur in Old French or Middle English. The Modern French name is ''ji'' /ʒi/, corresponding to Modern English ''jy'' (rhyming with ''i''), which in most areas was later replaced with ''jay'' (rhyming with ''kay'').}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" style="text-align:right;"|0.15% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ''jy'' |

| ''jy''{{efn|in ]}} || {{IPAc-en|ˈ|dʒ|aɪ}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''kay'' |

| ] || ''kay'' | ||

| |''kā''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|eɪ}} | |||

| |/kaː/ | |||

| |/kaː/ | |||

| |/kaː/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|0.77% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''el'' |

| ] || ''el'', ''ell''{{efn|In the US, an L-shaped object may be spelled ''ell''.}} | ||

| | ''el'' || {{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɛ|l}} | |||

| | /ɛl/ | |||

| | /ɛl/ | |||

| | /ɛl/ | |||

| | style="text-align:right;" |4.03% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''em'' |

| ] || ''em'' | ||

| |''em''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɛ|m}} | |||

| |/ɛm/ | |||

| |/ɛm/ | |||

| |/ɛm/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|2.41% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''en'' |

| ] || ''en'' | ||

| |''en''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɛ|n}} | |||

| |/ɛn/ | |||

| |/ɛn/ | |||

| |/ɛn/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|6.75% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''o''<!--No, not "oh", unless you have a citation--> |

| ] || ''o''<!--No, not "oh", unless you have a citation--> | ||

| |''ō''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|oʊ}} | |||

| |/oː/ | |||

| |/oː/ | |||

| |/oː/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|7.51% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''pee'' |

| ] || ''pee'' | ||

| |''pē''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|p|iː}} | |||

| |/peː/ | |||

| |/peː/ | |||

| |/peː/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|1.93% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''cue'', ''kew'',<br/>''kue'', ''que'' | |||

| | ] || ''cue''<ref group=nb>One of the few letter names not spelled with the letter in question. The spelling ''qu ~ que'' is obsolete, being attested from the 16th century.</ref> || {{IPA|/ˈkjuː/}} | |||

| |''qū''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|j|uː}} | |||

| |/kuː/ | |||

| |/kyː/ | |||

| |/kiw/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|0.10% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | rowspan="2" | ] || ''ar'' |

| rowspan="2" | ] || ''ar'' | ||

| | rowspan="2" |''er''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɑr}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" |/ɛr/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" |/ɛr/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" |/ɛr/ > /ar/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" style="text-align:right;" |5.99% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ''or'' |

| ''or''{{efn|in ]}} || {{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɔr}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | rowspan="2" | ] || ''ess'' | |||

| | ] || ''ess'' (''es-'')<ref group=nb>in compounds such as ''es-hook''</ref> || {{IPA|/ˈɛs/}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" |''es''|| rowspan="2" | {{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɛ|s}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" |/ɛs/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" |/ɛs/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" |/ɛs/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" style="text-align:right;" |6.33% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |''es-''{{efn|in compounds such as ''es-hook''}} | |||

| | ] || ''tee'' || {{IPA|/ˈtiː/}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''tee'' | |||

| | ] || ''u''<!--No, not "you", unless you have a citation--> || {{IPA|/ˈjuː/}} | |||

| |''tē''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|t|iː}} | |||

| |/teː/ | |||

| |/teː/ | |||

| |/teː/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|9.06% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''u''<!--No, not "you", unless you have a citation--> | |||

| | ] || ''vee'' || {{IPA|/ˈviː/}} | |||

| |''ū''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|j|uː}} | |||

| |/uː/ | |||

| |/yː/ | |||

| |/iw/ | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|2.76% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || ''vee'' | |||

| | ] || ''double-u'' || {{IPA|/ˈdʌbəl.juː/}}<ref group=nb>Especially in American English, the /l/ is often not pronounced in informal speech. ''(Merriam Webster's Collegiate Dictionary'', 10th ed). Common colloquial pronunciations are {{IPA|/ˈdʌbəjuː/}}, {{IPA|/ˈdʌbəjə/}}, and {{IPA|/ˈdʌbjə/}}, as in the nickname "Dubya", especially in terms like ''www.''</ref> | |||

| |–|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|v|iː}} | |||

| |– | |||

| |– | |||

| |– | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|0.98% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || '' |

| ] || ''double-u'' | ||

| |–|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|d|ʌ|b|əl|.|j|uː}}{{efn|Especially in American English, the /l/ is often not pronounced in informal speech. ''(Merriam Webster's Collegiate Dictionary'', 10th ed). Common colloquial pronunciations are {{IPAc-en|ˈ|d|ʌ|b|ə|j|uː}}, {{IPAc-en|ˈ|d|ʌ|b|ə|j|ə}}, and {{IPAc-en|ˈ|d|ʌ|b|j|ə}} (as in the nickname "Dubya") or just {{IPAc-en|ˈ|d|ʌ|b}}, especially in terms like ''www.''}} | |||

| |– | |||

| |– | |||

| |– | |||

| |style="text-align:right;"|2.36% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || |

| rowspan="2" | ] || rowspan="2" | ''ex'' | ||

| |''ex''|| rowspan="2" | {{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɛ|k|s}} | |||

| |/ɛks/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" |/iks/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" |/ɛks/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" style="text-align:right;" |0.15% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |''ix'' | |||

| | rowspan="3" | ] || ''zed''<ref group=nb>in ], ] and ]</ref> || {{IPA|/ˈzɛd/}} | |||

| |/ɪks/ | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | rowspan="3" |] | |||

| | ''zee''<ref group=nb>in ]</ref> || {{IPA|/ˈziː/}} | |||

| | rowspan="3" |''wy'', ''wye'' | |||

| | rowspan="2" |''hȳ'' | |||

| | rowspan="3" |{{IPAc-en|ˈ|w|aɪ}} | |||

| |/hyː/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" |''ui, gui'' ? | |||

| | rowspan="3" |/wiː/ | |||

| | rowspan="3" style="text-align:right;" |1.97% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |/iː/ | |||

| | ''izzard''<ref group=nb>in ]</ref> || {{IPA|/ˈɪzərd/}} | |||

| |} | |||

| Some groups of letters, such as ''pee'' and ''bee'', or ''em'' and ''en'', are easily confused in speech, especially when heard over the telephone or a radio communications link. ]s such as the ], used by ] pilots, police and others, are designed to eliminate this potential confusion by giving each letter a name that sounds quite different from any other. | |||

| ===Etymology=== | |||

| The names of the letters are for the most part direct descendents, via French, of the Latin (and Etruscan) names. (See ].) | |||

| {| class="wikitable IPA" | |||

| ! Letter !! Latin !! Old French !! Middle English !! Modern English | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |''ī graeca'' | |||

| | ] || ''ā'' /aː/ || /aː/ || /aː/ || /eɪ/ | |||

| |/iː ˈɡraɪka/ | |||

| |/iː ɡrɛːk/ | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | rowspan="2" | ] || ''zed''{{efn|in ], ] and ]}} | |||

| | ] || ''bē'' /beː/ || /beː/ || /beː/ || /biː/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" |''zēta''|| {{IPAc-en|ˈ|z|ɛ|d}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" |/ˈzeːta/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" |/ˈzɛːdə/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" |/zɛd/ | |||

| | rowspan="2" style="text-align:right;"|0.07% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ''zee''{{efn|in ], ] and ]}} || {{IPAc-en|ˈ|z|iː}} | |||

| | ] || ''cē'' /keː/ || /tʃeː/ > /tseː/ > /seː/ || /seː/ || /siː/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''dē'' /deː/ || /deː/ || /deː/ || /diː/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''ē'' /eː/ || /eː/ || /eː/ || /iː/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''ef'' /ɛf/ || /ɛf/ || /ɛf/ || /ɛf/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''gē'' /ɡeː/ || /dʒeː/ || /dʒeː/ || /dʒiː/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''hā'' /haː/ > /ˈaha/ > /ˈakːa/ || /ˈaːtʃə/ || /aːtʃ/ || /eɪtʃ/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''ī'' /iː/ || /iː/ || /iː/ || /aɪ/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || – || – || – || /dʒeɪ/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''kā'' /kaː/ || /kaː/ || /kaː/ || /keɪ/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''el'' /ɛl/ || /ɛl/ || /ɛl/ || /ɛl/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''em'' /ɛm/ || /ɛm/ || /ɛm/ || /ɛm/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''en'' /ɛn/ || /ɛn/ || /ɛn/ || /ɛn/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''ō'' /oː/ || /oː/ || /oː/ || /oʊ/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''pē'' /peː/ || /peː/ || /peː/ || /piː/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''qū'' /kuː/ || /kyː/ || /kiw/ || /kjuː/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''er'' /ɛr/ || /ɛr/ || /ɛr/ > /ar/ || /ɑr/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''es'' /ɛs/ || /ɛs/ || /ɛs/ || /ɛs/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''tē'' /teː/ || /teː/ || /teː/ || /tiː/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''ū'' /uː/ || /yː/ || /iw/ || /juː/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || – || – || – || /viː/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || – || – || – || /ˈdʌbəl.juː/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''ex'', ''ix'' /ɛks, ɪks/ || /iks/ || /ɛks/ || /ɛks/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''hȳ'' /hyː, iː/<br>''ī graeca'' /iː ˈɡraɪka/ || ''ui, gui'' ?<br>''i grec'' /iː ɡrɛːk/ || /wiː/ ? || /waɪ/ | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ''zēta'' /ˈzeːta/ || ''zede'' /ˈzɛːdə/<br>''et zede'' /e(t) ˈzɛːdə/ || /zɛd/<br>/ˈɛzɛd/ || /zɛd/<br>/ˈɪzə(r)d/ | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| === Etymology === | |||

| The names of the letters are for the most part direct descendants, via French, of the Latin (and Etruscan) names. (See ].) | |||

| The regular phonological developments (in rough chronological order) are: | The regular phonological developments (in rough chronological order) are: | ||

| * palatalization before front vowels of Latin {{IPA|/k/}} successively to {{IPA|/tʃ/}}, {{IPA|/ts/}}, and finally to Middle French {{IPA|/s/}}. Affects C. | * palatalization before front vowels of Latin {{IPA|/k/}} successively to {{IPA|/tʃ/}}, {{IPA|/ts/}}, and finally to Middle French {{IPA|/s/}}. Affects C. | ||

| * palatalization before front vowels of Latin {{IPA|/ɡ/}} to Proto-Romance and Middle French {{IPA|/dʒ/}}. Affects G. | * palatalization before front vowels of Latin {{IPA|/ɡ/}} to Proto-Romance and Middle French {{IPA|/dʒ/}}. Affects G. | ||

| * fronting of Latin {{IPA|/uː/}} to Middle French {{IPA|/yː/}}, becoming Middle English {{IPA|/iw/}} and then Modern English {{IPA|/juː/}}. Affects Q, U. | * fronting of Latin {{IPA|/uː/}} to Middle French {{IPA|/yː/}}, becoming Middle English {{IPA|/iw/}} and then Modern English {{IPA|/juː/}}. Affects Q, U. | ||

| * the inconsistent lowering of Middle English {{IPA|/ɛr/}} to {{IPA|/ar/}}. Affects R. | * the inconsistent lowering of Middle English {{IPA|/ɛr/}} to {{IPA|/ar/}}. Affects R. | ||

| * the ], shifting all Middle English long vowels. Affects A, B, C, D, E, G, H, I, K, O, P, T, and presumably Y. | * the ], shifting all Middle English long vowels. Affects A, B, C, D, E, G, H, I, K, O, P, T, and presumably Y. | ||

| The novel forms are ''aitch'', a regular development of Medieval Latin ''acca''; ''jay'', a new letter presumably |

The novel forms are ''aitch'', a regular development of Medieval Latin ''acca''; ''jay'', a new letter presumably vocalised like neighboring ''kay'' to avoid confusion with established ''gee'' (the other name, ''jy'', was taken from French); ''vee'', a new letter named by analogy with the majority; ''double-u'', a new letter, self-explanatory (the name of Latin V was ''ū''); ''wye'', of obscure origin but with an antecedent in Old French ''wi''; ], from the Romance phrase ''i zed'' or ''i zeto'' "and Z" said when reciting the alphabet; and ''zee'', an American levelling of ''zed'' by analogy with other consonants. | ||

| Some groups of letters, such as ''pee'' and ''bee'', or ''em'' and ''en'', are easily confused in speech, especially when heard over the telephone or a radio communications link. ]s such as the ], used by ] pilots, police and others, are designed to eliminate this potential confusion by giving each letter a name that sounds quite different from any other. | |||

| ==Phonology== | |||

| {{Main|English phonology}} | |||

| ===Ampersand=== | |||

| The ] (&) has sometimes appeared at the end of the English alphabet, as in Byrhtferð's list of letters in 1011.<ref name="Evertype" /> ''&'' was regarded as the 27th letter of the English alphabet, as taught to children in the US and elsewhere.{{vague|date=October 2024|reason=The "US and elsewhere" is too vague considering how globally widespread English education is.}} An example may be seen in M. B. Moore's 1863 book ''The Dixie Primer, for the Little Folks''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://docsouth.unc.edu/imls/moore/moore.html#moore5|work=Branson, Farrar & Co., Raleigh NC|title=The Dixie Primer, for the Little Folks}}</ref> Historically, the figure is a ] for the letters ''Et''. In English and many other languages, it is used to represent the word ''and'', plus occasionally the Latin word ''et'', as in the abbreviation ''&c'' (et cetera).<!---and is used for other purposes, too. & is on a normal keyboard with the combo SHIFT + 7---> | |||

| ===Archaic letters=== | |||

| ] and ] had a number of non-Latin letters that have since dropped out of use. Some of these either took the names of the equivalent ], since there were no Latin names to adopt, or were runes themselves (], ]). | |||

| *Æ æ '']'' or ''æsc'' {{IPAc-en|'|æ|ʃ}}, used for the vowel {{IPAc-en|æ}}, which disappeared from the language and then reformed. Replaced by ]{{efn|in British English}} and ] now. | |||

| *Ð ð '']''<!--OED spelling first-->, ''eð'' or ''eth'' {{IPAc-en|'|ɛ|ð}}, used for the consonants {{IPAc-en|ð}} and {{IPAc-en|θ}} (which did not become phonemically distinct until after the letter had fallen out of use). Replaced by ] now. | |||

| *Þ þ '']'' or ''þorn'' {{IPAc-en|'|θ|ɔr|n}}, used for the consonants {{IPAc-en|ð}} and {{IPAc-en|θ}} (which did not become phonemically distinct until after the letter had fallen out of use). Replaced by ] now. | |||

| *Œ œ '']'', ''ēðel'', ''œ̄þel'', etc. {{IPAc-en|'|ɛ|ð|əl}}, used for the vowel {{IPAslink|œ}}, which disappeared from the language quite early. Replaced by ]{{efn|in British English}} and ] now. | |||

| *Ƿ ƿ '']''<!--OED spelling first-->, ''ƿen'' (Kentish) or ''wynn'' {{IPAc-en|'|w|ɪ|n}}, used for the consonant {{IPAc-en|w}}. (The letter 'w' had not yet been invented.) Replaced by ] now. | |||

| *Ȝ ȝ '']'', ''ȝogh'' or ''yoch'' {{IPAc-en|'|j|ɒ|g}} or {{IPAc-en|'|j|ɒ|x}}, used for various sounds derived from {{IPAc-en|g}}, such as {{IPAc-en|j}} and {{IPAc-en|x}}. Replaced by ], ],{{efn|in words like ''hallelujah''}} ], and ]{{efn|in words like ''loch'' in Scottish English}} now. | |||

| *ſ '']'', an earlier form of the ] "s" that continued to be used alongside the modern lowercase s into the 1800s. Replaced by lowercase ] now. | |||

| *ꝛ '']'', an alternative form of the lowercase "r". | |||

| == Diacritics == | |||

| {{Main|English terms with diacritical marks}} | |||

| The most common diacritic marks seen in English publications are the acute (é), grave (è), circumflex (â, î, or ô), tilde (ñ), umlaut and diaeresis (ü or ï—the same symbol is used for two different purposes), and cedilla (ç).<ref>{{Citation|last=Strizver|first=Ilene|title=Accents & Accented Characters|url=http://www.fonts.com/content/learning/fontology/level-3/signs-and-symbols/accents|work=Fontology|publisher=Monotype Imaging|access-date=2019-06-17}}</ref> Diacritics used for ] may be replaced with ] or omitted. | |||

| === Loanwords === | |||

| The letters A, E, I, O, and U are considered vowel letters, since (except when silent) they represent ]s; the remaining letters are considered consonant letters, since when not silent they generally represent ]s. However, Y commonly represents vowels as well as a consonant (e.g., "myth"), as very rarely does W (e.g., "]"). Conversely, U and I sometimes represent a consonant (e.g., "quiz" and "onion" respectively). | |||

| ] marks mainly appear in loanwords such as ''naïve'' and ''façade''. Informal English writing tends to omit diacritics because of their absence from the keyboard, while professional copywriters and typesetters tend to include them. | |||

| As such words become naturalised in English, there is a tendency to drop the diacritics, as has happened with many older borrowings from French, such as ''hôtel''. Words that are still perceived as foreign tend to retain them; for example, the only spelling of ''soupçon'' found in English dictionaries (the ] and others) uses the diacritic. However, diacritics are likely to be retained even in naturalised words where they would otherwise be confused with a common native English word (for example, ''résumé'' rather than ''resume'').<ref>{{Citation |publisher=] |title=MHRA Style Guide: A Handbook for Authors and Editors |url=http://www.mhra.org.uk/style |year=2013 |postscript=. |at=Section 2.2 |edition=3rd |location=London |format=pdf |access-date=2019-06-17 |isbn=978-1-78188-009-8}}</ref> Rarely, they may even be added to a loanword for this reason (as in ''maté'', from Spanish '']'' but following the pattern of ''café'', from French, to distinguish from ''mate''). | |||

| W and Y are sometimes referred as semivowels. | |||

| === Native English words === | |||

| ==Letter numbers and frequencies== | |||

| Occasionally, especially in older writing, diacritics are used to indicate the ]s of a word: ''cursed'' (verb) is pronounced with one syllable, while ''cursèd'' (]) is pronounced with two. For this, ''è'' is used widely in poetry, e.g., in Shakespeare's sonnets. ] used ''ë'', as in ''O wingëd crown''. | |||

| Similarly, while in ''chicken coop'' the letters ''-oo-'' represent a single vowel sound (a ]), they less often represent two which may be marked with a diaresis as in ''zoölogist''<ref>{{Cite book|last=Zoölogist|first=Minnesota Office of the State|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=J_kUAAAAYAAJ&q=%22zo%C3%B6logist%22&pg=PA4|title=Report of the State Zoölogist|date=1892|language=en}}</ref> and ''coöperation''. This use of the ] is rare but found in some well-known publications, such as '']'' and '']''. Some publications, particularly in UK usage, have replaced the diaeresis with a hyphen such as in co-operative.{{citation needed|date=September 2021}} | |||

| In general, these devices are not used even where they would serve to alleviate some degree of confusion. | |||

| == Punctuation marks within words == | |||

| === Apostrophe === | |||

| The ] (ʼ) is not usually considered part of the English alphabet nor used as a diacritic, even in loanwords. But it is used for two important purposes in written English: to mark the "possessive"{{efn|Linguistic analyses vary on how best to characterise the English possessive morpheme ''-'s'': a noun case inflectional suffix distinct to ''possession'', a ''genitive case'' inflectional suffix equivalent to prepositional periphrastic ''of X'' (or rarely ''for X''), an ''edge inflection'' that uniquely attaches to a noun phrase's final (rather than ''head'') word, or an ''enclitic postposition''.}} and to mark ] words. Current standards require its use for both purposes. Therefore, apostrophes are necessary to spell many words even in isolation, unlike most punctuation marks, which are concerned with indicating sentence structure and other relationships among multiple words. | |||

| * It distinguishes (from the otherwise identical regular ] inflection ''-s'') the English ] morpheme "''<nowiki/>'s"'' (apostrophe alone after a regular plural affix, giving ''-s''' as the standard mark for plural + possessive). Practice settled in the 18th century; before then, practices varied but typically all three endings were written ''-s'' (but without cumulation). This meant that only regular nouns bearing neither could be confidently identified, and plural and possessive could be potentially confused (e.g., "the Apostles words"'';'' "those things over there are my husbands"<ref>{{cite web |url-status=dead |url=http://www.news.com.au/couriermail/story/0,23739,21619016-27197,00.html |title=Little Things that Matter |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120904080438/www.news.com.au/couriermail/story/0,23739,21619016-27197,00.html |archive-date=2012-09-04 |website=The Courier-Mail |date=2007-04-26 |access-date=2013-04-07 |first1=Jane |last1=Fynes-Clinton }}</ref>)—which undermines the logic of "]" forms. | |||

| * Many common contractions have near-]s from which they are distinguished in writing only by an apostrophe, for example ''it's'' (''it is'' or ''it has'') as opposed to ''its'', the possessive form of "it", or ''she'd'' (''she would'' or ''she had'') as opposed to ''shed''. | |||

| In a '']'' blog, ] argued that apostrophe is the 27th letter of the alphabet, arguing that it does not function as a form of ].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Pullum |first= Geoffrey K.|title=Being an apostrophe |journal =Lingua Franca |date=March 22, 2013 |publisher=] |url=https://www.chronicle.com/blogs/linguafranca/2013/03/21/being-an-apostrophe/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231013205712/https://www.chronicle.com/blogs/linguafranca/2013/03/21/being-an-apostrophe/ |archive-date= Oct 13, 2023 }}</ref> | |||

| === Hyphen === | |||

| ]s are often used in English ]. Written compound words may be hyphenated, open or closed, so specifics are guided by ]. Some writers may use a ] in certain instances. | |||

| == Frequencies == | |||

| {{Main|Letter frequency}} | {{Main|Letter frequency}} | ||

| The letter most commonly used in English is E. The least used letter is Z. | The letter most commonly used in English is E. The least used letter is Z. The frequencies shown in the table may differ in practice according to the type of text.<ref>{{cite book|title=Cipher Systems: The Protection of Communications|last1=Beker|first1=Henry|last2=Piper|first2=Fred|publisher=]|year=1982|page=397}} Table also available from | ||

| {{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CyCcRAm7eQMC&pg=PA36|title=Cryptological Mathematics|last=Lewand|first=Robert|publisher=]|year=2000|isbn=978-0883857199|page=36}} and {{cite web|url=http://pages.central.edu/emp/LintonT/classes/spring01/cryptography/letterfreq.html|title=English letter frequencies|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080708193159/http://pages.central.edu/emp/LintonT/classes/spring01/cryptography/letterfreq.html|archive-date=2008-07-08|url-status=dead|access-date=2008-06-25}}</ref> | |||

| == Phonology == | |||

| The table below shows the frequency of letter usage in a particular sample of written English,{{vague|date=August 2013}} although the frequencies vary somewhat according to the type of text.<ref> | |||

| {{Main|English phonology}} | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |last1 = Beker | |||

| The letters A, E, I, O, and U are considered vowel letters, since (except when silent) they represent ]s, although I and U represent consonants in words such as "onion" and "quail" respectively. | |||

| |first1 = Henry | |||

| |last2 = Piper | |||

| The letter Y sometimes represents a consonant (as in "young") and sometimes a vowel (as in "myth"). Very rarely, W may represent a vowel (as in "cwm", a ] loanword). | |||

| |first2 = Fred | |||

| | title = Cipher Systems: The Protection of Communications | |||

| The consonant sounds represented by the letters W and Y in English (/w/ and /j/ as in went /wɛnt/ and yes /jɛs/) are referred to as ] (or ''glides'') by linguists, however this is a description that applies to the ''sounds'' represented by the letters and not to the letters themselves. | |||

| |publisher = ] | |||

| |year = 1982 | |||

| The remaining letters are considered consonant letters, since when not silent they generally represent ]s. | |||

| |page = 397}} Table also available from | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| == History == | |||

| |last = Lewand | |||

| {{See also|History of the Latin alphabet|English orthography}} | |||

| |first = Robert | |||

| |title = Cryptological Mathematics | |||

| ===Old English=== | |||

| |publisher = ] | |||

| {{Main|Old English Latin alphabet}} | |||

| |year = 2000 | |||

| |page = 36 | |||

| The ] itself was initially written in the ] runic alphabet, in use from the 5th century. This alphabet was brought to what is now England, along with the proto-form of the language itself, by ] settlers. Very few examples of this form of written ] have survived, mostly as short inscriptions or fragments. | |||

| |url = http://books.google.com/books?id=CyCcRAm7eQMC&pg=PA36 | |||

| |isbn = 978-0883857199}} and </ref> | |||

| The ], introduced by Christian missionaries, began to replace the Anglo-Saxon futhorc from about the 7th century, although the two continued in parallel for some time. As such, the Old English alphabet began to employ parts of the Roman alphabet in its construction.<ref>{{cite journal |journal=Early Medieval Europe |last=Shaw |first=Phillip |date=May 2013 |title=Adapting the Roman alphabet for Writing Old English: Evidence from Coin Epigraphy and Single-Sheet Characters |volume= 21 |issue=2 |pages=115–139|via=Ebscohost |doi=10.1111/emed.12012 |publisher=Wiley Blackwell |s2cid=163075636 |url=https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/emed.12012}}</ref> Futhorc influenced the emerging English alphabet by providing it with the letters '']'' (Þ þ) and '']'' (Ƿ ƿ). The letter '']'' (Ð ð) was later devised as a modification of '']ee'' (D d), and finally '']'' ({{lang|ang|Ȝ}} {{lang|ang|ȝ}}) was created by Norman scribes from the ] in Old English and ], and used alongside their ]. | |||

| {| class = "wikitable sortable" | |||

| ! N !! Letter !! Frequency | |||

| The a-e ] '']'' (Æ æ) was adopted as a letter in its own right, named after a futhorc rune '']''. In very early Old English the o-e ligature '']'' (Œ œ) also appeared as a distinct letter, likewise named after a rune, '']''.{{citation_needed|date=March 2014}} Additionally, the v–v or u-u ligature '']'' (W w) was in use. | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1 ||A || align=right | 8.17% | |||

| In the year 1011, a monk named ] recorded the traditional order of the Old English alphabet.<ref name="Evertype">Michael Everson, Evertype, Baldur Sigurðsson, Íslensk Málstöð, ''''</ref> He listed the 24 letters of the Latin alphabet first, including the ], then 5 additional English letters, starting with the ] ''ond'' (⁊), an insular symbol for ''and'': | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2 ||B || align=right | 1.49% | |||

| {{Block indent | |||

| |- | |||

| |style=font-family:monospace | |||

| | 3 ||C || align=right | 2.78% | |||

| |1={{big|A B C D E F G H I K L M N O P Q R S T V X Y Z & ⁊ Ƿ Þ Ð Æ}} | |||

| |- | |||

| }} | |||

| | 4 ||D || align=right | 4.25% | |||

| |- | |||

| ===Modern English=== | |||

| | 5 ||E || align=right | 12.70% | |||

| In the ] of ], the letters ] (þ), ] (ð), ] (ƿ), ] ({{lang|ang|ȝ}}), ] (æ), and ] (œ) are obsolete. ] borrowings reintroduced homographs of æ and œ into ] and ], though they are largely obsolete (see "Ligatures in recent usage" below), and where they are used they are not considered to be separate letters (e.g., for collation purposes), but rather ]. Thorn and eth were both replaced by '']'', though thorn continued in existence for some time, its lowercase form gradually becoming graphically indistinguishable from the ] ] in most handwriting. ''Y'' for '']'' can still be seen in ] such as "] Booke Shoppe". The letters þ and ð are still used in present-day ] (where they now represent two separate sounds, {{IPA|/θ/}} and {{IPA|/ð/}} having become phonemically-distinct – as indeed also happened in Modern English), while ð is still used in present-day ] (although only as a silent letter). Wynn disappeared from English around the 14th century when it was supplanted by ''uu'', which ultimately developed into the modern ''w''. Yogh disappeared around the 15th century and was typically replaced by ''gh''. | |||

| |- | |||

| | 6 ||F || align=right | 2.23% | |||

| The letters '']'' and '']'', as distinct from '']'' and '']'', were introduced in the 16th century, and ''w'' assumed the status of an independent letter. The variant lowercase form ] (ſ) lasted into ], and was used in non-final position up to the early 19th century. Today, the English alphabet is considered to consist of the following 26 letters: | |||

| |- | |||

| | 7 ||G || align=right | 2.02% | |||

| {{flatlist | indent=1 | | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] a}} | |||

| | 8 ||H || align=right | 6.09% | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] b}} | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] c}} | |||

| | 9 ||I || align=right | 6.97% | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] d}} | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] e}} | |||

| | 10 ||J || align=right | 0.15% | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] f}} | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] g}} | |||

| | 11 ||K || align=right | 0.77% | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] h}} | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] i}} | |||

| | 12 ||L || align=right | 4.03% | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] j}} | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] k}} | |||

| | 13 ||M || align=right | 2.41% | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] l}} | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] m}} | |||

| | 14 ||N || align=right | 6.75% | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] n}} | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] o}} | |||

| | 15 ||O || align=right | 7.51% | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] p}} | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] q}} | |||

| | 16 ||P || align=right | 1.93% | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] r}} | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] s}} | |||

| | 17 ||Q || align=right | 0.10% | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] t}} | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] u}} | |||

| | 18 ||R || align=right | 5.99% | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] v}} | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] w}} | |||

| | 19 ||S || align=right | 6.33% | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] x}} | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] y}} | |||

| | 20 ||T || align=right | 9.06% | |||

| * {{Nowrap|] z}} | |||

| |- | |||

| }} | |||

| | 21 ||U || align=right | 2.76% | |||

| |- | |||

| Written English has a number of ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.phonicsontheweb.com/digraphs.php|title=Digraphs (Phonics on the Web)|website=phonicsontheweb.com|access-date=2016-04-07|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160413162011/http://www.phonicsontheweb.com/digraphs.php|archive-date=2016-04-13|url-status=dead}}</ref> but they are not considered separate letters of the alphabet: | |||

| | 22 ||V || align=right | 0.98% | |||

| |- | |||

| {{flatlist | indent=1 | | |||

| | 23 ||W || align=right | 2.36% | |||

| * ch (usually makes tsh sound) | |||

| |- | |||

| * ci (makes s sound) | |||

| | 24 ||X || align=right | 0.15% | |||

| * ck (makes k sound) | |||

| |- | |||

| * gh (makes f or g sound (also silent)) | |||

| | 25 ||Y || align=right | 1.97% | |||

| * ng (makes a ]) | |||

| |- | |||

| * ph (makes f sound) | |||

| | 26 ||Z || align=right | 0.07% | |||

| * qu (makes kw sound) | |||

| |} | |||

| * rh (makes r sound) | |||

| * sc (makes s sound (also a blend){{clarify|reason=blend of what?|date=March 2023}}) | |||

| * sh (makes ch sound without t) | |||

| * th (makes theta or eth sound) | |||

| * ti (makes sh sound) | |||

| * wh (makes w sound) | |||

| * wr (makes r sound) | |||

| * zh (makes j sound without d) | |||

| }} | |||

| === Ligatures in recent usage === | |||

| ] of ]]] | |||

| Outside of professional papers on specific subjects that traditionally use ligatures in ]s, ligatures are seldom used in modern English. The ligatures '']'' and '']'' were until the 19th century (slightly later in American English){{citation needed|date=December 2014}} used in formal writing for certain words of Greek or Latin origin, such as '']'' and '']'', although such ligatures were not used in either classical Latin or ancient Greek. These are now usually rendered as "ae" and "oe" in all types of writing,{{citation needed|date=December 2014}} although in American English, a lone ''e'' has mostly supplanted both (for example, ''encyclopedia'' for ''encyclopaedia'', and ''maneuver'' for ''manoeuvre''). | |||

| Some ]s used to typeset English texts contain commonly used ligatures, such as for {{angle bracket|tt}}, {{angle bracket|fi}}, {{angle bracket|fl}}, {{angle bracket|ffi}}, and {{angle bracket|ffl}}. These are not independent letters{{snd}}although in traditional ], each of these ligatures would have its own ] (type element) for practical reasons{{snd}} but simply ] choices created to optimize the legibility of the text. | |||

| ==Proposed reforms== | |||

| There have been a number of proposals to ]. These include proposals for the addition of letters to the English alphabet, such as '']'' or ''engma'' (Ŋ ŋ), used to replace the digraph "]" and represent the ] sound with a single letter. ], based on the Latin alphabet, introduced a number of new letters as part of a wider proposal to reform English orthography. Other proposals have gone further, proposing entirely new scripts for written English to replace the Latin alphabet such as the ] and the ]. | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |Alphabet song}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |NATO phonetic alphabet}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |English orthography}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |English-language spelling reform}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |American manual alphabet}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |Two-handed manual alphabets}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |English Braille}} | ||

| * {{Annotated link |American Braille |prefer=wikidata<!-- Use Wikidata description instead of SD because the latter is in American English, which conflicts with this article, which is in British English; see MOS:ARTCON --> |desc_first_letter_case=upper}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |New York Point}} | ||

| * {{Annotated link |Chinese respelling of the English alphabet}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Burmese respelling of the English alphabet}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Base36}} | |||

| ==Notes and references== | |||

| ===Notes=== | |||

| {{Notelist}} | |||

| == |

===References=== | ||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| {{reflist|group=nb}} | |||

| ===Further reading=== | |||

| ==References== | |||

| * {{cite book| title=Alphabetical: How Every Letter Tells a Story| author=Michael Rosen |isbn=978-1619027022| year=2015 | publisher=Counterpoint }} | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| * {{Citation |last1=Upward |first1=Christopher |last2=Davidson |first2=George |title=The History of English Spelling |date=2011 |location=Oxford |publisher=Wiley-Blackwell |author-link1=Christopher Upward |isbn=978-1-4051-9024-4 |lccn=2011008794 |postscript=.}} | |||

| {{Description of English}} | {{Description of English}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:English Alphabet}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:English Alphabet}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 01:12, 9 January 2025

Latin-script alphabet consisting of 26 letters| English alphabet | |

|---|---|

An English-language pangram written with the FF Dax Regular typeface An English-language pangram written with the FF Dax Regular typeface | |

| Script type | Alphabet |

| Time period | c. 16th century – present |

| Languages | English |

| Related scripts | |

| Parent systems | (Proto-writing) |

| Child systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Latn (215), Latin |

| Unicode | |

| Unicode alias | Latin |

| Unicode range | U+0000–U+007E Basic Latin |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between , / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. | |

Modern English is written with a Latin-script alphabet consisting of 26 letters, with each having both uppercase and lowercase forms. The word alphabet is a compound of alpha and beta, the names of the first two letters in the Greek alphabet. Old English was first written down using the Latin alphabet during the 7th century. During the centuries that followed, various letters entered or fell out of use. By the 16th century, the present set of 26 letters had largely stabilised:

- A a

- B b

- C c

- D d

- E e

- F f

- G g

- H h

- I i

- J j

- K k

- L l

- M m

- N n

- O o

- P p

- Q q

- R r

- S s

- T t

- U u

- V v

- W w

- X x

- Y y

- Z z

There are 5 vowel letters and 19 consonant letters—as well as Y and W, which may function as either type.

Written English has a large number of digraphs, such as ⟨ch⟩, ⟨ea⟩, ⟨oo⟩, ⟨sh⟩, and ⟨th⟩. Diacritics are generally not used to write native English words, which is unusual among orthographies used to write the languages of Europe.

Letter names

Problems playing this file? See media help.

The names of the letters are commonly spelled out in compound words and initialisms (e.g., tee-shirt, deejay, emcee, okay, etc.), derived forms (e.g., exed out, effing, to eff and blind, aitchless, etc.), and objects named after letters (e.g., en and em in printing, and wye in railroading). The spellings listed below are from the Oxford English Dictionary. Plurals of consonant names are formed by adding -s (e.g., bees, efs or effs, ems) or -es in the cases of aitches, esses, exes. Plurals of vowel names also take -es (i.e., aes, ees, ies, oes, ues), but these are rare. For a letter as a letter, the letter itself is most commonly used, generally in capitalised form, in which case the plural just takes -s or -'s (e.g. Cs or c's for cees).

| Letter | Name | Name pronunciation | Freq. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modern English |

Latin | Modern English |

Latin | Old French |

Middle English | ||

| A | a | ā | /ˈeɪ/, /ˈæ/ | /aː/ | /aː/ | /aː/ | 8.17% |

| B | bee | bē | /ˈbiː/ | /beː/ | /beː/ | /beː/ | 1.49% |

| C | cee | cē | /ˈsiː/ | /keː/ | /tʃeː/ > /tseː/ > /seː/ |

/seː/ | 2.78% |

| D | dee | dē | /ˈdiː/ | /deː/ | /deː/ | /deː/ | 4.25% |

| E | e | ē | /ˈiː/ | /eː/ | /eː/ | /eː/ | 12.70% |

| F | ef, eff | ef | /ˈɛf/ | /ɛf/ | /ɛf/ | /ɛf/ | 2.23% |

| G | gee | gē | /ˈdʒiː/ | /ɡeː/ | /dʒeː/ | /dʒeː/ | 2.02% |

| H | aitch | hā | /ˈeɪtʃ/ | /haː/ > /ˈaha/ > /ˈakːa/ |

/ˈaːtʃə/ | /aːtʃ/ | 6.09% |

| haitch | /ˈheɪtʃ/ | ||||||

| I | i | ī | /ˈaɪ/ | /iː/ | /iː/ | /iː/ | 6.97% |

| J | jay | – | /ˈdʒeɪ/ | – | – | 0.15% | |

| jy | /ˈdʒaɪ/ | ||||||

| K | kay | kā | /ˈkeɪ/ | /kaː/ | /kaː/ | /kaː/ | 0.77% |

| L | el, ell | el | /ˈɛl/ | /ɛl/ | /ɛl/ | /ɛl/ | 4.03% |

| M | em | em | /ˈɛm/ | /ɛm/ | /ɛm/ | /ɛm/ | 2.41% |

| N | en | en | /ˈɛn/ | /ɛn/ | /ɛn/ | /ɛn/ | 6.75% |

| O | o | ō | /ˈoʊ/ | /oː/ | /oː/ | /oː/ | 7.51% |

| P | pee | pē | /ˈpiː/ | /peː/ | /peː/ | /peː/ | 1.93% |

| Q | cue, kew, kue, que |

qū | /ˈkjuː/ | /kuː/ | /kyː/ | /kiw/ | 0.10% |

| R | ar | er | /ˈɑːr/ | /ɛr/ | /ɛr/ | /ɛr/ > /ar/ | 5.99% |

| or | /ˈɔːr/ | ||||||

| S | ess | es | /ˈɛs/ | /ɛs/ | /ɛs/ | /ɛs/ | 6.33% |

| es- | |||||||

| T | tee | tē | /ˈtiː/ | /teː/ | /teː/ | /teː/ | 9.06% |

| U | u | ū | /ˈjuː/ | /uː/ | /yː/ | /iw/ | 2.76% |

| V | vee | – | /ˈviː/ | – | – | – | 0.98% |

| W | double-u | – | /ˈdʌbəl.juː/ | – | – | – | 2.36% |

| X | ex | ex | /ˈɛks/ | /ɛks/ | /iks/ | /ɛks/ | 0.15% |

| ix | /ɪks/ | ||||||

| Y | wy, wye | hȳ | /ˈwaɪ/ | /hyː/ | ui, gui ? | /wiː/ | 1.97% |

| /iː/ | |||||||

| ī graeca | /iː ˈɡraɪka/ | /iː ɡrɛːk/ | |||||

| Z | zed | zēta | /ˈzɛd/ | /ˈzeːta/ | /ˈzɛːdə/ | /zɛd/ | 0.07% |

| zee | /ˈziː/ | ||||||

Etymology

The names of the letters are for the most part direct descendants, via French, of the Latin (and Etruscan) names. (See Latin alphabet: Origins.)

The regular phonological developments (in rough chronological order) are:

- palatalization before front vowels of Latin /k/ successively to /tʃ/, /ts/, and finally to Middle French /s/. Affects C.

- palatalization before front vowels of Latin /ɡ/ to Proto-Romance and Middle French /dʒ/. Affects G.

- fronting of Latin /uː/ to Middle French /yː/, becoming Middle English /iw/ and then Modern English /juː/. Affects Q, U.

- the inconsistent lowering of Middle English /ɛr/ to /ar/. Affects R.

- the Great Vowel Shift, shifting all Middle English long vowels. Affects A, B, C, D, E, G, H, I, K, O, P, T, and presumably Y.

The novel forms are aitch, a regular development of Medieval Latin acca; jay, a new letter presumably vocalised like neighboring kay to avoid confusion with established gee (the other name, jy, was taken from French); vee, a new letter named by analogy with the majority; double-u, a new letter, self-explanatory (the name of Latin V was ū); wye, of obscure origin but with an antecedent in Old French wi; izzard, from the Romance phrase i zed or i zeto "and Z" said when reciting the alphabet; and zee, an American levelling of zed by analogy with other consonants.

Some groups of letters, such as pee and bee, or em and en, are easily confused in speech, especially when heard over the telephone or a radio communications link. Spelling alphabets such as the ICAO spelling alphabet, used by aircraft pilots, police and others, are designed to eliminate this potential confusion by giving each letter a name that sounds quite different from any other.

Ampersand

The ampersand (&) has sometimes appeared at the end of the English alphabet, as in Byrhtferð's list of letters in 1011. & was regarded as the 27th letter of the English alphabet, as taught to children in the US and elsewhere. An example may be seen in M. B. Moore's 1863 book The Dixie Primer, for the Little Folks. Historically, the figure is a ligature for the letters Et. In English and many other languages, it is used to represent the word and, plus occasionally the Latin word et, as in the abbreviation &c (et cetera).

Archaic letters

Old and Middle English had a number of non-Latin letters that have since dropped out of use. Some of these either took the names of the equivalent runes, since there were no Latin names to adopt, or were runes themselves (thorn, wyn).

- Æ æ Ash or æsc /ˈæʃ/, used for the vowel /æ/, which disappeared from the language and then reformed. Replaced by ae and e now.

- Ð ð Edh, eð or eth /ˈɛð/, used for the consonants /ð/ and /θ/ (which did not become phonemically distinct until after the letter had fallen out of use). Replaced by th now.

- Þ þ Thorn or þorn /ˈθɔːrn/, used for the consonants /ð/ and /θ/ (which did not become phonemically distinct until after the letter had fallen out of use). Replaced by th now.

- Œ œ Ethel, ēðel, œ̄þel, etc. /ˈɛðəl/, used for the vowel /œ/, which disappeared from the language quite early. Replaced by oe and e now.

- Ƿ ƿ Wyn, ƿen (Kentish) or wynn /ˈwɪn/, used for the consonant /w/. (The letter 'w' had not yet been invented.) Replaced by w now.

- Ȝ ȝ Yogh, ȝogh or yoch /ˈjɒɡ/ or /ˈjɒx/, used for various sounds derived from /ɡ/, such as /j/ and /x/. Replaced by y, j, gh, and ch now.

- ſ long s, an earlier form of the lowercase "s" that continued to be used alongside the modern lowercase s into the 1800s. Replaced by lowercase s now.

- ꝛ r rotunda, an alternative form of the lowercase "r".

Diacritics

Main article: English terms with diacritical marksThe most common diacritic marks seen in English publications are the acute (é), grave (è), circumflex (â, î, or ô), tilde (ñ), umlaut and diaeresis (ü or ï—the same symbol is used for two different purposes), and cedilla (ç). Diacritics used for tonal languages may be replaced with tonal numbers or omitted.

Loanwords

Diacritic marks mainly appear in loanwords such as naïve and façade. Informal English writing tends to omit diacritics because of their absence from the keyboard, while professional copywriters and typesetters tend to include them.

As such words become naturalised in English, there is a tendency to drop the diacritics, as has happened with many older borrowings from French, such as hôtel. Words that are still perceived as foreign tend to retain them; for example, the only spelling of soupçon found in English dictionaries (the OED and others) uses the diacritic. However, diacritics are likely to be retained even in naturalised words where they would otherwise be confused with a common native English word (for example, résumé rather than resume). Rarely, they may even be added to a loanword for this reason (as in maté, from Spanish yerba mate but following the pattern of café, from French, to distinguish from mate).

Native English words

Occasionally, especially in older writing, diacritics are used to indicate the syllables of a word: cursed (verb) is pronounced with one syllable, while cursèd (adjective) is pronounced with two. For this, è is used widely in poetry, e.g., in Shakespeare's sonnets. J. R. R. Tolkien used ë, as in O wingëd crown.

Similarly, while in chicken coop the letters -oo- represent a single vowel sound (a digraph), they less often represent two which may be marked with a diaresis as in zoölogist and coöperation. This use of the diaeresis is rare but found in some well-known publications, such as MIT Technology Review and The New Yorker. Some publications, particularly in UK usage, have replaced the diaeresis with a hyphen such as in co-operative.

In general, these devices are not used even where they would serve to alleviate some degree of confusion.

Punctuation marks within words

Apostrophe

The apostrophe (ʼ) is not usually considered part of the English alphabet nor used as a diacritic, even in loanwords. But it is used for two important purposes in written English: to mark the "possessive" and to mark contracted words. Current standards require its use for both purposes. Therefore, apostrophes are necessary to spell many words even in isolation, unlike most punctuation marks, which are concerned with indicating sentence structure and other relationships among multiple words.

- It distinguishes (from the otherwise identical regular plural inflection -s) the English possessive morpheme "'s" (apostrophe alone after a regular plural affix, giving -s' as the standard mark for plural + possessive). Practice settled in the 18th century; before then, practices varied but typically all three endings were written -s (but without cumulation). This meant that only regular nouns bearing neither could be confidently identified, and plural and possessive could be potentially confused (e.g., "the Apostles words"; "those things over there are my husbands")—which undermines the logic of "marked" forms.

- Many common contractions have near-homographs from which they are distinguished in writing only by an apostrophe, for example it's (it is or it has) as opposed to its, the possessive form of "it", or she'd (she would or she had) as opposed to shed.

In a Chronicle of Higher Education blog, Geoffrey Pullum argued that apostrophe is the 27th letter of the alphabet, arguing that it does not function as a form of punctuation.

Hyphen

Hyphens are often used in English compound words. Written compound words may be hyphenated, open or closed, so specifics are guided by stylistic policy. Some writers may use a slash in certain instances.

Frequencies

Main article: Letter frequencyThe letter most commonly used in English is E. The least used letter is Z. The frequencies shown in the table may differ in practice according to the type of text.

Phonology

Main article: English phonologyThe letters A, E, I, O, and U are considered vowel letters, since (except when silent) they represent vowels, although I and U represent consonants in words such as "onion" and "quail" respectively.

The letter Y sometimes represents a consonant (as in "young") and sometimes a vowel (as in "myth"). Very rarely, W may represent a vowel (as in "cwm", a Welsh loanword).

The consonant sounds represented by the letters W and Y in English (/w/ and /j/ as in went /wɛnt/ and yes /jɛs/) are referred to as semi-vowels (or glides) by linguists, however this is a description that applies to the sounds represented by the letters and not to the letters themselves.

The remaining letters are considered consonant letters, since when not silent they generally represent consonants.

History

See also: History of the Latin alphabet and English orthographyOld English

Main article: Old English Latin alphabetThe English language itself was initially written in the Anglo-Saxon futhorc runic alphabet, in use from the 5th century. This alphabet was brought to what is now England, along with the proto-form of the language itself, by Anglo-Saxon settlers. Very few examples of this form of written Old English have survived, mostly as short inscriptions or fragments.

The Latin script, introduced by Christian missionaries, began to replace the Anglo-Saxon futhorc from about the 7th century, although the two continued in parallel for some time. As such, the Old English alphabet began to employ parts of the Roman alphabet in its construction. Futhorc influenced the emerging English alphabet by providing it with the letters thorn (Þ þ) and wynn (Ƿ ƿ). The letter eth (Ð ð) was later devised as a modification of dee (D d), and finally yogh (Ȝ ȝ) was created by Norman scribes from the insular g in Old English and Irish, and used alongside their Carolingian g.

The a-e ligature ash (Æ æ) was adopted as a letter in its own right, named after a futhorc rune æsc. In very early Old English the o-e ligature ethel (Œ œ) also appeared as a distinct letter, likewise named after a rune, œðel. Additionally, the v–v or u-u ligature double-u (W w) was in use.

In the year 1011, a monk named Byrhtferð recorded the traditional order of the Old English alphabet. He listed the 24 letters of the Latin alphabet first, including the ampersand, then 5 additional English letters, starting with the Tironian note ond (⁊), an insular symbol for and:

A B C D E F G H I K L M N O P Q R S T V X Y Z & ⁊ Ƿ Þ Ð ÆModern English

In the orthography of Modern English, the letters thorn (þ), eth (ð), wynn (ƿ), yogh (ȝ), ash (æ), and ethel (œ) are obsolete. Latin borrowings reintroduced homographs of æ and œ into Middle English and Early Modern English, though they are largely obsolete (see "Ligatures in recent usage" below), and where they are used they are not considered to be separate letters (e.g., for collation purposes), but rather ligatures. Thorn and eth were both replaced by th, though thorn continued in existence for some time, its lowercase form gradually becoming graphically indistinguishable from the minuscule y in most handwriting. Y for th can still be seen in pseudo-archaisms such as "Ye Olde Booke Shoppe". The letters þ and ð are still used in present-day Icelandic (where they now represent two separate sounds, /θ/ and /ð/ having become phonemically-distinct – as indeed also happened in Modern English), while ð is still used in present-day Faroese (although only as a silent letter). Wynn disappeared from English around the 14th century when it was supplanted by uu, which ultimately developed into the modern w. Yogh disappeared around the 15th century and was typically replaced by gh.

The letters u and j, as distinct from v and i, were introduced in the 16th century, and w assumed the status of an independent letter. The variant lowercase form long s (ſ) lasted into early modern English, and was used in non-final position up to the early 19th century. Today, the English alphabet is considered to consist of the following 26 letters:

- A a

- B b

- C c

- D d

- E e

- F f

- G g

- H h

- I i

- J j

- K k

- L l

- M m

- N n

- O o

- P p

- Q q

- R r

- S s

- T t

- U u

- V v

- W w

- X x

- Y y

- Z z

Written English has a number of digraphs, but they are not considered separate letters of the alphabet:

- ch (usually makes tsh sound)

- ci (makes s sound)

- ck (makes k sound)

- gh (makes f or g sound (also silent))

- ng (makes a voiced velar nasal)

- ph (makes f sound)

- qu (makes kw sound)

- rh (makes r sound)

- sc (makes s sound (also a blend))

- sh (makes ch sound without t)

- th (makes theta or eth sound)

- ti (makes sh sound)

- wh (makes w sound)

- wr (makes r sound)

- zh (makes j sound without d)

Ligatures in recent usage

Outside of professional papers on specific subjects that traditionally use ligatures in loanwords, ligatures are seldom used in modern English. The ligatures æ and œ were until the 19th century (slightly later in American English) used in formal writing for certain words of Greek or Latin origin, such as encyclopædia and cœlom, although such ligatures were not used in either classical Latin or ancient Greek. These are now usually rendered as "ae" and "oe" in all types of writing, although in American English, a lone e has mostly supplanted both (for example, encyclopedia for encyclopaedia, and maneuver for manoeuvre).

Some typefaces used to typeset English texts contain commonly used ligatures, such as for ⟨tt⟩, ⟨fi⟩, ⟨fl⟩, ⟨ffi⟩, and ⟨ffl⟩. These are not independent letters – although in traditional typesetting, each of these ligatures would have its own sort (type element) for practical reasons – but simply type design choices created to optimize the legibility of the text.

Proposed reforms

There have been a number of proposals to extend or replace the basic English alphabet. These include proposals for the addition of letters to the English alphabet, such as eng or engma (Ŋ ŋ), used to replace the digraph "ng" and represent the voiced velar nasal sound with a single letter. Benjamin Franklin's phonetic alphabet, based on the Latin alphabet, introduced a number of new letters as part of a wider proposal to reform English orthography. Other proposals have gone further, proposing entirely new scripts for written English to replace the Latin alphabet such as the Deseret alphabet and the Shavian alphabet.

See also

- Alphabet song – Song that teaches an alphabetPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- NATO phonetic alphabet – Letter names for unambiguous communication

- English orthography – English spelling and punctuating rules

- English-language spelling reform – Proposed reforms to English spelling to be more phonetic

- American manual alphabet – Manual alphabet that augments the vocabulary of American Sign Language

- Two-handed manual alphabets – Part of a deaf sign language

- English Braille – Tactile writing system for English

- American Braille – Former braille used for the English language in the United States of America

- New York Point – Tactile alphabet invented by William Bell Wait

- Chinese respelling of the English alphabet – Chinese pronunciation of the English alphabet

- Burmese respelling of the English alphabet – Burmese Transcription

- Base36 – Binary-to-text encoding scheme

Notes and references

Notes

- Clicked the 🅇 box to close a tab or app

- Fucking

- Without the letter H

- often in Hiberno-English, due to the letter's pronunciation in the Irish language

- The usual form in Hiberno-English and Australian English

- The letter J did not occur in Old French or Middle English. The Modern French name is ji /ʒi/, corresponding to Modern English jy (rhyming with i), which in most areas was later replaced with jay (rhyming with kay).

- in Scottish English

- In the US, an L-shaped object may be spelled ell.

- in Hiberno-English

- in compounds such as es-hook

- Especially in American English, the /l/ is often not pronounced in informal speech. (Merriam Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, 10th ed). Common colloquial pronunciations are /ˈdʌbəjuː/, /ˈdʌbəjə/, and /ˈdʌbjə/ (as in the nickname "Dubya") or just /ˈdʌb/, especially in terms like www.

- in British English, Hiberno-English and Commonwealth English

- in American English, Newfoundland English and Philippine English

- in British English

- in British English

- in words like hallelujah

- in words like loch in Scottish English

- Linguistic analyses vary on how best to characterise the English possessive morpheme -'s: a noun case inflectional suffix distinct to possession, a genitive case inflectional suffix equivalent to prepositional periphrastic of X (or rarely for X), an edge inflection that uniquely attaches to a noun phrase's final (rather than head) word, or an enclitic postposition.

References

- The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition.

- ^ Michael Everson, Evertype, Baldur Sigurðsson, Íslensk Málstöð, On the Status of the Latin Letter Þorn and of its Sorting Order

- "The Dixie Primer, for the Little Folks". Branson, Farrar & Co., Raleigh NC.

- Strizver, Ilene, "Accents & Accented Characters", Fontology, Monotype Imaging, retrieved 2019-06-17

- MHRA Style Guide: A Handbook for Authors and Editors (pdf) (3rd ed.), London: Modern Humanities Research Association, 2013, Section 2.2, ISBN 978-1-78188-009-8, retrieved 2019-06-17.

- Zoölogist, Minnesota Office of the State (1892). Report of the State Zoölogist.

- Fynes-Clinton, Jane (2007-04-26). "Little Things that Matter". The Courier-Mail. Archived from the original on 2012-09-04. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- Pullum, Geoffrey K. (March 22, 2013). "Being an apostrophe". Lingua Franca. Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on Oct 13, 2023.