| Revision as of 23:23, 19 July 2015 editIñaki LL (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users11,820 edits Undid revision 672116732 by 188.78.131.18 (talk) WP is a collaborative project, express your concerns on the discussion page← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:13, 4 January 2025 edit undoCommonsDelinker (talk | contribs)Bots, Template editors1,017,175 edits Replacing OrderOfCristCross.svg with File:Cross_of_the_Military_Order_of_Christ.svg (by CommonsDelinker because: File renamed: Criterion 3 (obvious error)). | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Medieval Christian military campaigns}} | |||

| {{other uses}} | |||

| {{italic title}} | |||

| ]'']] | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Reconquista}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=August 2022}} | |||

| The '''''Reconquista''''' ("reconquest"){{efn|While spelled largely the same, the pronunciation differs among the different Iberian languages, mostly in accordance with the sound structures of the respective languages. The pronunciations are as follows: | |||

| ] (13th century), which deals with a late 10th-century battle in San Esteban de Gormaz involving the troops of ] and ].<ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://produccioncientifica.ucm.es/documentos/5d399a13299952068445dc80|title=Composición, estilo y texto en la miniatura del Códice Rico de las CSM|journal=Alcanate: Revista de Estudios Alfonsíes|issn=1579-0576|year=2012|first=M.ª Victoria|last=Chico Picaza|volume=8 |page=170−171}}</ref>]] | |||

| *{{IPA-es|rekoŋˈkista|lang}} | |||

| The '''''Reconquista''''' (] and ] for {{gloss|reconquest}}){{efn|While it is largely spelled in the same way, the pronunciation of it varies among the different languages which are spoken on the ] as well as in neighboring territories. The pronunciations of it are as follows: | |||

| *{{IPA-pt|ʁɛkõˈkiʃtɐ|lang}} | |||

| *{{IPA |

* ], ] and {{IPA|es|rekoŋˈkista|lang|small=no}}; | ||

| *{{IPA |

* {{IPA|pt|ʁɨkõˈkiʃtɐ|lang|small=no}}; | ||

| *{{IPA |

* {{IPA|ca|rəkuŋˈkestə|lang|link=yes|small=no}} or {{IPA|ca|rekoŋˈkesta|}}, spelled ''Reconquesta''; colloquially also known as and spelled ''Reconquista'' (pron. {{IPA|ca|rəkuŋˈkistə|}} or {{IPA|ca|rekoŋˈkista|}}); | ||

| * {{IPA|eu|erekoŋkis̺ta|lang|link=yes|small=no}}, spelled ''Errekonkista''; | |||

| *{{IPA-eu|erekoŋkis̺ta|lang}}, spelled ''Errekonkista''}} is a period of approximately 781 years in the history of the ], after the ] in 711 to the ], the last Islamic state on the peninsula, in 1492. It ended right before the discovery of the ], and the period of the ] and ] colonial empires which followed. | |||

| * {{IPA|an|ɾekoŋˈkjesta|lang|link=yes|small=no}}, spelled ''Reconquiesta''; | |||

| * {{IPA|oc|rekuŋˈkɛsta|lang|label=]/]:|small=no}}, spelled ''Reconquèsta'', or {{IPA|oc|rekuŋˈkistɔ|}}, spelled ''Reconquista''; | |||

| * {{IPA|fr|ʁəkɔ̃kɛːt|lang|link=yes|small=no}}, spelled ''Reconquête''; ''Reconquista'' commonly used as well.}} or the '''reconquest of ]'''{{efn|The ] term for 'Reconquista' is ''al-Istirdād'' ({{lang|ar|الاسترداد}}), literally 'the Recovery', although it is more commonly known as ''suqūṭ al-Andalus'' ({{lang|ar|سقوط الأندلس}}), 'the fall of ]'.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Kabha |first=M. |date=2023 |title=The Fall of Al-Andalus and the Evolution of its Memory in Modern Arab-Muslim Historiography |journal=The Maghreb Review |volume=48 |issue=3 |pages=289–303 |doi=10.1353/tmr.2023.a901468 |s2cid=259503095 |url=https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/457/article/901468/summary}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Al-Mallah |first=M. |date=2019 |title=The Afterlife of Al-Andalus: Muslim Iberia in Contemporary Arab and Hispanic Narratives |volume=56 |issue=1 |url=https://doi.org/10.5325/complitstudies.56.1.e-22 |journal=Comparative Literature Studies |pages=e–22 |doi=10.5325/complitstudies.56.1.e-22|s2cid=239092774 }}</ref>}} was a series of military and cultural campaigns that European Christian ] waged against the ] following the ] by the ], culminating in the reign of the ].<ref>{{Citation |last=Caraccioli |first=Mauro José |title=Narratives of Conquest and the Conquest of Narrative |date=2021 |work=Writing the New World |pages=14–38 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1gt9419.6 |access-date=2024-09-11 |series=The Politics of Natural History in the Early Spanish Empire |publisher=University Press of Florida |jstor=j.ctv1gt9419.6 |isbn=978-1-68340-170-4|quote=La Reconquista: a 700-year military and cultural campaign against the Moorish Caliphates of Southern Iberia that culminated in the joint reign of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile as Reyes Católicos.}}</ref><ref name="Britannica">{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/event/Reconquista |title=Reconquista |date=23 November 2022 |encyclopedia=Britannica}}</ref> The beginning of the ''Reconquista'' is traditionally dated to the ] ({{circa|718}} or 722), in which an ] army achieved the first Christian victory over the forces of the Umayyad Caliphate since the beginning of the military invasion.<ref>{{harvnb|Collins|1989|p=147}}; {{harvnb|Reilly|1993|pp=75–76}}; {{harvnb|Deyermond|1985|p=346}}; {{harvnb|Hillgarth|2009|p=66 n. 28}}</ref> The ''Reconquista'' ended in 1492 with the ] to the ].<ref name=Britannica/> | |||

| In the late 10th century, the Umayyad ] ] waged a series of military campaigns for 30 years in order to subjugate the northern Christian kingdoms. When the ] disintegrated in the early 11th century, a series of petty successor states known as '']s'' emerged. The northern kingdoms took advantage of this situation and struck deep into ]; they fostered civil war, intimidated the weakened ''taifas'', and made them pay large tributes ('']'') for "protection".<ref> '']'', 22nd ed. (online).</ref><ref>According to Catlos, 83, Arabic authors referred to the ''parias'' as a '']'', the equivalent of the Islamic head tax on non-believers.</ref><ref name=fletcher>Fletcher, 7–8.</ref><ref>Reilly, 9.</ref> | |||

| Traditionally, historians mark the beginning of the Reconquista with the ] (718 or 722), in which a small army, led by the nobleman ], defeated an Umayyad army in the mountains of northern Iberia and established a small Christian principality in ]. | |||

| In the 12th century, the ''Reconquista'' was above all a political action to develop the kingdoms of ], ] and ]. The king's action took precedence over that of the local lords, with the help of the ] and also supported by ].<ref>Porto Editora – Reconquista Cristã na Infopédia . Porto: Porto Editora. . Disponível em https://www.infopedia.pt/$reconquista-crista</ref> Following a Muslim resurgence under the ] in the 12th century, the great Moorish strongholds fell to Christian forces in the 13th century, after the decisive ] (1212), the ] (1236) and the ] (1248)—leaving only the Muslim enclave of Granada as a ] in the south. After the ] in January 1492, the entire Iberian peninsula was controlled by Christian rulers. On 30 July 1492, as a result of the ], the ] in Castile and Aragon—some 200,000 people—were ]. The conquest was followed by a series of edicts (1499–1526) which ], who were later ] from the Iberian realms of the ] by a series of decrees starting in 1609.<ref name="Perry2012">{{cite book|author=Mary Elizabeth Perry|editor=Kevin Ingram|title=The Conversos and Moriscos in Late Medieval Spain and Beyond: Volume Two: The Morisco Issue|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nQ0yAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA167|date= 2012|publisher=Brill|isbn=978-90-04-22860-3|page=167|chapter=8: Morisco Stories and the Complexities of Resistance and Assimilation}}</ref><ref name="Dadson2014">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RtDCAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA101|title=Tolerance and Coexistence in Early Modern Spain: Old Christians and Moriscos in the Campo de Calatrava|first=Trevor J.|last=Dadson|date=2014|publisher=Boydell & Brewer Ltd|page=101|isbn=978-1855662735}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Boase|first=Roger|date=4 April 2002|title=The Muslim Expulsion from Spain|journal=]|volume=52|issue=4|quote=The majority of those permanently expelled settling in the ] or ], especially in Oran, Tunis, Tlemcen, Tetuán, Rabat and Salé. Many travelled overland to France, but after the assassination of Henry of Navarre by Ravaillac in May 1610, they were forced to emigrate to Italy, Sicily or Constantinople.}}</ref> Approximately three million Muslims emigrated or were driven out of Spain between 1492 and 1610.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Islamic Encounters |url=https://www.brown.edu/Facilities/John_Carter_Brown_Library/exhibitions/islamic/pages/spain.html |access-date=2023-05-25 |website=www.brown.edu |publisher=] |quote=Between 1492 and 1610, some 3,000,000 Muslims voluntarily left or were expelled from Spain, resettling in North Africa.}}</ref> | |||

| Beginning in the 19th century,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.diariodeburgos.es/noticia/ZD86B418D-DD64-5400-8FBA1220E9A23524/20131102/reconquista/es/mito |title=La reconquista es un mito|date=2 November 2013 |website= Diario de Burgos|language=es|access-date=13 September 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190925134813/https://www.diariodeburgos.es/noticia/ZD86B418D-DD64-5400-8FBA1220E9A23524/20131102/reconquista/es/mito |archive-date=25 September 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> traditional historiography has used the term ''Reconquista'' for what was earlier thought of as a restoration of the ] over conquered territories.<ref>{{Cite report|last=Ríos Saloma|first=Martín|title=La Reconquista: génesis de un mito historiográfico |url= https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/589/58922939009.pdf|publisher=Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas/UNAM Departamento de Historia México|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304053429/http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/589/58922939009.pdf |archive-date=4 March 2016|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>Sanjuán, Alejandro García. ''A 1300 Años de la conquista de Al-Andalus (711–2011)'' (2012): 65.</ref> The concept of ''Reconquista'', consolidated in Spanish historiography in the second half of the 19th century, was associated with the development of a Spanish national identity, emphasizing ] and romantic aspects.<ref name =Fitz2009>{{harvnb|García Fitz|2009|pp=144–145}} "Hay que reconocer que la irrupción de este concepto en la historiografía hispánica del siglo XIX, con su fuerte carga nacionalista, romántica y, en ocasiones, colonialista, tuvo un éxito notable y se transmitió, manteniendo algunos de sus rasgos identitarios más llamativos, a la del siglo XX. "</ref> It is rememorated in the '']'' festival, very popular in parts of Southeastern Spain, and which can also be found in a few places in former Spanish colonies. Pursuant to an ] worldview, the concept is a symbol of significance for the 21st century European ]. {{Sfn|Silva|2020|pp=57–65}}<ref>{{Cite news |last1=Paone |first1=Antony |last2=Thomas |first2=Leigh |date=6 December 2021 |title=Far-right French presidential hopeful promises 'reconquest' at rally |language=en |work=Reuters |url=https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/far-right-french-presidential-hopeful-promises-reconquest-rally-2021-12-05/ |access-date=22 June 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ==Concept and duration== | ==Concept and duration== | ||

| {{Campaignbox Reconquista}} | |||

| Catholic Spanish and Portuguese historiography, from the beginnings of historical scholarship until the twentieth century, stressed the existence of a continuous phenomenon by which the Christian Iberian kingdoms opposed and conquered the Muslim kingdoms, understood as a common enemy who had militarily seized Christian territory.<ref>{{cite book |title= Reconquest and Crusade in Medieval Spain|last=O'Callaghan |first=Joseph F. |authorlink= Rosamond McKitterick |year= 2003 |publisher= University of Pennsylvania Press |location=Philadelphia|isbn= 0812236963|page= 19|pages= |accessdate=February 15, 2012|url=http://books.google.com/?id=4gVIt5u0U5wC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref> The concept of a Christian reconquest of the peninsula first emerged, in tenuous form, at the end of the 9th century.<ref name=CambridgeMedieval>{{cite book |title= The New Cambridge Medieval. History 1|last=McKitterick |first=Rosamond |authorlink= Rosamond McKitterick |author2=Collins, R. |year= 1990 |publisher= Cambridge University Press |location=|isbn= 9780521362924|page= 289|pages= |accessdate=July 26, 2012|url=http://books.google.com/?id=ZEaSdNBL0sgC&pg=PA272&lpg=PA272&dq=the+basques+roger+collins#v=onepage&q=the%20basques%20roger%20collins&f=false}}</ref> A landmark was set by the Christian '']'' (883-884), a document stressing the Christian and Muslim cultural and religious divide in Iberia and the necessity to drive the Muslims out. | |||

| The term ''Reconquista'', used to describe the struggle between Christians and Muslims in the Iberian peninsula during the ], was not used by writers of the period. Since its development as a term in medieval historiography occurred centuries after the events it references, it has acquired various meanings. Its meaning as an actual reconquest has been subject to the particular concerns or prejudices of scholars, who have sometimes wielded it as a weapon in ideological disputes.{{sfn|García Fitz|2009|pp=144–145}} | |||

| A discernible ] ideology that would later become part of the concept of "Reconquista", a Christian reconquest of the peninsula, appeared in writings by the end of the 9th century.<ref name="CambridgeMedieval">{{cite book |last=McKitterick |first=Rosamond |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZEaSdNBL0sgC&pg=PA289 |title=The New Cambridge Medieval. History 1 |author2=Collins, R. |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=1990 |isbn=978-0521362924 |page=289 |quote=By the later ninth century some of the distinctive ideology of the later 'Reconquista' had come into being. Christian writers, such as the anonymous author of the so-called 'Prophetic Chronicle' of 883/4, could look forward to the expulsion of the Arabs from Spain, and a sense of both an ethnic and a religious-cultural divide between the inhabitants of the small northern kingdoms and the dominant elite in the south was marked in the writings of both sides. On the other hand, it is unwise to be too linear in the approach to the origins of the 'Reconquista', as tended to be the way with Spanish historiography in the earlier part of the twentieth century. Periods of peaceful co-existence or of limited and localised frontier disturbances were more frequent than ones of all-out military conflict between al-Andalus and the Christian kingdoms. As has been mentioned, the former never made any serious effort to eliminate the latter. Moreover, as in the case of relations between the Arista dynasty in Pamplona and the Banü Qasi, the mutual interest could be a stronger bond than ideological divisions based on antagonistic creeds. These tendencies were, if anything, to be reinforced in the tenth century. |author-link=Rosamond McKitterick |access-date=26 July 2012}}</ref> For example, the anonymous Christian chronicle '']'' (883–884) claimed a historical connection between the ] conquered by the Muslims in 711 and the ] in which the document was produced, and stressed a Christian and Muslim cultural and religious divide in Hispania, and a necessity to drive out the Muslims and restore conquered territories. In fact, in the writings of both sides, there was a sense of divide based on ethnicity and culture between the inhabitants of the small Christian kingdoms in the north and the dominant elite in the Muslim-ruled south.<ref name="CambridgeMedieval" /> | |||

| Nevertheless, the difference between Christian and Muslim kingdoms in early medieval Spain was not seen at the time as anything like the clear-cut opposition which later emerged. Both Christian and Muslim rulers fought amongst themselves. Alliances between Muslims and Christians were not at all uncommon.<ref name=CambridgeMedieval/> Blurring distinctions even further were the mercenaries from both sides who simply fought for whoever paid the most. The period is looked back upon today one of religious tolerance.<ref>María Rosa Menocal, ''The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain'', Back Bay Books, 2003, ISBN 0316168718, and see ].</ref> | |||

| |url=https://rbdigital.realbiblioteca.es/s/rbme/item/13125 |website=rbdigital.realbiblioteca.es |publisher=Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial |access-date=24 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211123235323/https://rbdigital.realbiblioteca.es/s/rbme/item/13125 |archive-date=23 November 2021 |date=1283}}</ref>]] | |||

| The Crusades, which started late in the eleventh century, bred the religious ideology of a Christian reconquest, confronted at that time with a similarly staunch Muslim ] ideology in ]: the ] and even to a greater degree, in the ]. In fact previous documents (10-11th century) are mute on any idea of "reconquest".<ref>{{cite book |title= Reconquest and Crusade in Medieval Spain|last=O'Callaghan |first=Joseph F. |authorlink= Rosamond McKitterick |year= 2003 |publisher= University of Pennsylvania Press |location=Philadelphia|isbn= 0812236963|page= 18|pages= |accessdate=August 26, 2012|url=http://books.google.com/?id=4gVIt5u0U5wC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref> Propaganda accounts of Muslim-Christian hostility came into being to support that idea, most notably the ], a fictitious 12th-century French version of the ] dealing with the Iberian '']s'' (''Moors''), and taught as historical in the French educational system since 1880.<ref>{{cite web|title="Pagans are wrong and Christians are right": Alterity, Gender, and Nation in the ''Chanson de Roland''|last1=Kinoshita |first1=Sharon |last2= |first2= |date=2001-01-31|work= |publisher=Duke University Press|accessdate=12 February 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=DiVanna |first1=Isabel N. |last2= |first2= |year=2010 |title=Politicizing national literature: the scholarly debate around La Chanson de Roland in the nineteenth century |journal=Historical research |volume=84 |issue=223 |pages=26 |publisher=Institute of Historical Research |doi=10.1111/j.1468-2281.2009.00540.x |url= }}</ref> | |||

| The linear approach to the origins of a ''Reconquista'' taken in early twentieth-century historiography is complicated by a number of issues.<ref name="CambridgeMedieval" /> For example, periods of peaceful coexistence, or at least of limited and localised skirmishes on the frontiers, were more prevalent over the 781 years of Muslim rule in Iberia than periods of military conflict between the Christian kingdoms and al-Andalus.<ref name="CambridgeMedieval" /> Additionally, both Christian and Muslim rulers ], and cooperation and alliances between Muslims and Christians were not uncommon, such as between the ] and ] as early as the 9th century.<ref name="CambridgeMedieval" /><ref name="Keefe" /> Blurring distinctions even further were the mercenaries from both sides who simply fought for whoever paid the most.<ref name="Keefe" /> The period is seen today to have had long episodes of relative religious coexistence and tolerance.<ref name="Menocal2009">{{cite book |last1=Menocal |first1=Maria Rosa |title=The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain |date=2009 |publisher=Little, Brown |isbn=978-0-316-09279-1 |pages=214, 223 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4dxbqEmU-OkC&pg=PT214 }} (see ]).</ref> The idea of a continuous ''Reconquista'' has been challenged by modern scholars.<ref name="Fernández-Morera2016">{{cite book |last1=Fernández-Morera |first1=Darío |title=The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise |date=2016 |publisher=Open Road Media |isbn=978-1-5040-3469-2 |page=50 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PJNgCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT50 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="O'Callaghan2013">{{cite book |last1=O'Callaghan |first1=Joseph F. |title=Reconquest and Crusade in Medieval Spain |date=2013 |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |isbn=978-0-8122-0306-6 |pages=18–19 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6fPSBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA18}}</ref> | |||

| Many recent historians dispute the whole concept of ''Reconquista'' (as well as that of a prior ''conquista'' by the Moors) as a concept created ''a posteriori'' in the service of later political goals. It has been called a "myth".<ref>"''La reconquista es un mito''", </ref><ref>"''Los inicios de la Reconquista, Derribando el Mito''", </ref><ref>"''La santina burgalesa y el mito de la reconquista''", </ref><ref>"''La Reconquista: un estado de la cuestión''", </ref><ref>Eugènia de Pagès, "''La 'Reconquista', allò que mai no va existir''", ''La Lamentable'', July 11, 2014, </ref><ref>Martín M. Ríos Saloma, "''La Reconquista. Génesis de un mito historiográfico''", ''Historia y Grafía'', 30, 2008, pp. 191-216, , retrieved 10-12-2014.</ref> One of the first Spanish intellectuals to question the idea of a "reconquest" that lasts for eight centuries was ], writing in the first half of the twentieth century.<ref>"''Yo no entiendo cómo se puede llamar reconquista a una cosa que dura ocho siglos''" ("I don't understand how something that lasted eight centuries can be called a reconquest"), in ''España invertebrada''. Quoted by De Pagès, E. July 11, 2014.</ref> However, the term is still in wide use. | |||

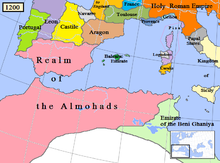

| ]c ] and surrounding states, including the Christian Kingdoms of ], ], ], ], and the ], c. 1200.]] | |||

| The final campaign to conquer Granada, near the end of the 15th century, is never designated "reconquista" in Spanish; it is rather "la conquista de Granada", the conquest of Granada. Nevertheless, references to the ''reconquista'' as a whole are understood to include this campaign. | |||

| The ], which started late in the 11th century, bred the religious ideology of a Christian reconquest.<ref name="Black2003">{{Cite book |last1=Black |first1=Jeremy |title=World History |last2=Brewer |first2=Paul |last3=Shaw |first3=Anthony |last4=Chandler |first4=Malcolm |last5=Cheshire |first5=Gerard |last6=Cranfield |first6=Ingrid |last7=Ralph Lewis |first7=Brenda |last8=Sutherland |first8=Joe |last9=Vint |first9=Robert |publisher=Parragon Books |year=2003 |isbn=0-75258-227-5 |location=] |page=55 |author-link=Jeremy Black (historian)}}</ref> In the years just before the ] took place, Spanish kings used religious differences as a reason to fight against Muslims, although this argument was not extensively used beforehand.<ref name="Black2003" /> In ] at that time, the Christian states were confronted by the ], and to an even greater degree, they were confronted by the ], who espoused a similarly staunch Muslim ] ideology. In fact, previous documents which date from the 10th and 11th centuries are mute on any idea of "reconquest".<ref name="O'Callaghan2013" /> Propaganda accounts of Muslim-Christian hostility came into being to support that idea, most notably the '']'', an 11th-century French '']'' that offers a fictionalised retelling of the ] dealing with the Iberian '']s'' (''Moors''), and centuries later introduced in the French school system with a view to instilling moral and national values in the population following the 1870 defeat of the French in the ], regardless of the actual events.<ref>{{cite journal|title='Pagans are wrong and Christians are right': Alterity, Gender, and Nation in the ''Chanson de Roland''|last=Kinoshita|first=Sharon|journal=Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies|volume=31|issue=1|date=Winter 2001|pages=79–111|doi=10.1215/10829636-31-1-79|s2cid=143132248}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=DiVanna |first1=Isabel N. |year=2010 |title=Politicizing national literature: the scholarly debate around La Chanson de Roland in the nineteenth century |journal=Historical Research |volume=84 |issue=223 |pages=109–134 |doi=10.1111/j.1468-2281.2009.00540.x |url= }}</ref><ref>{{Citation |last=Lucken |first=Christopher |title=Actualité de la Chanson de Roland: Une épopée populaire au programme d'agrégation |date=2019-04-16 |url=http://books.openedition.org/pur/52857 |work=Le savant dans les Lettres |pages=93–106 |editor-last=Bähler |editor-first=Ursula |series=Interférences |place=Rennes |publisher=Presses universitaires de Rennes |isbn=978-2-7535-5783-3 |access-date=2022-11-18 |editor2-last=Cangemi |editor2-first=Valérie |editor3-last=Corbellari |editor3-first=Alain}}</ref> | |||

| ==Background == | |||

| The consolidation of the modern idea of a "''Reconquista''" is inextricably linked to the foundational myths of ] in the 19th century, associated with the development of a Centralist, Castilian, and staunchly Catholic brand of nationalism,{{sfn|García Fitz|2009|p=152}} evoking nationalistic, romantic and sometimes colonialist themes.<ref name="Fitz2009" /> The concept gained further track in the 20th century during the ].<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://www.eldiario.es/andalucia/enabierto/elecciones_en_Andalucia_2018-reconquista-Vox_6_843125717.html |title=Vox, la Reconquista y la salvación de España |last= Alejandro García Sanjuán|website=eldiario.es|date=5 December 2018|language=es|access-date=15 February 2019 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20190216094117/https://www.eldiario.es/andalucia/enabierto/elecciones_en_Andalucia_2018-reconquista-Vox_6_843125717.html |archive-date=16 February 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> It thus became one of the key tenets of the historiographical discourse of ], the mythological and ideological identity of the regime. The discourse was underpinned in its most traditional version by an avowed historical illegitimacy of al-Andalus and the subsequent glorification of the Christian conquest.<ref>{{Cite journal |page=133|last=García Sanjuán|first=Alejandro|year=2016|title=La persistencia del discurso nacionalcatólico sobre el Medievo peninsular en la historiografía española actual|journal= Historiografías|volume=12|issn=2174-4289|issue= 12 |doi=10.26754/ojs_historiografias/hrht.2016122367|url=https://papiro.unizar.es/ojs/index.php/historiografias/article/view/2367|publisher=]|location=Zaragoza|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ===Islamic conquest of Christian Iberia=== | |||

| {{Further|Umayyad conquest of Hispania|Battle of Guadalete}} | |||

| In 711, Muslim Moors, mainly North African ] soldiers with some ]s, crossed the ] and began their conquest of the ]. After their conquest of the Visigothic kingdom's Iberian territories, the Muslims crossed the ] and took control of ] in 719, the last province of the Visigothic kingdom to be occupied. From their stronghold of ], they launched raids into the ]. | |||

| The idea of a "liberation war" of ''reconquest'' against the Muslims, who were viewed as foreigners, suited the anti-Republican rebels during the ], the rebels agitated for the banner of a Spanish fatherland, a fatherland which, according to them, was being threatened by regional nationalisms and ].{{Sfn|García Fitz|2009|pp=146–147}} Their rebellious pursuit was thus a crusade for the restoration of the Church's unity, where Franco stood for both ] and ].{{Sfn |García Fitz|2009|pp=146–147}} The ''Reconquista'' has become a rallying call for right and far-right parties in Spain to expel from office incumbent progressive or peripheral nationalist options, as well as their values, in different political contexts as of 2018.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.publico.es/politica/ultraderecha-vox-rescata-viejo-concepto-reconquista.html|title=¿Por qué Vox rescata ahora el viejo concepto de 'Reconquista'?|website= www.publico.es |date=15 January 2019 |access-date=15 February 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190216035443/https://www.publico.es/politica/ultraderecha-vox-rescata-viejo-concepto-reconquista.html |archive-date=16 February 2019 |url-status= live}}</ref><ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.europapress.es/nacional/noticia-casado-apelar-vox-reconquista-pp-empezado-reconquista-andalucia-acabara-asturias-20190111154752.html |title=Casado, tras apelar Vox a la Reconquista: El PP ha empezado la reconquista por Andalucía y la acabará en Asturias|publisher= Europa Press |date= 11 January 2019|access-date=15 February 2019|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20190216035637/https://www.europapress.es/nacional/noticia-casado-apelar-vox-reconquista-pp-empezado-reconquista-andalucia-acabara-asturias-20190111154752.html |archive-date=16 February 2019|url-status= live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.eldiario.es/clm/vox-santiago-abascal-reconquista-toledo_0_863014649.html |title= Vox designa a Toledo como el punto donde comenzar la 'reconquista' del centro de España|last=Bravo|first= Francisca |website=eldiario.es|date=31 January 2019|language=es|access-date=15 February 2019|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20190216035503/https://www.eldiario.es/clm/vox-santiago-abascal-reconquista-toledo_0_863014649.html|archive-date=16 February 2019|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url= https://www.elnacional.cat/es/politica/casado-reconquista-engano-independentismo_290181_102.html|title=Casado promete una 'reconquista' para que 'caiga el engaño independentista'|website=ElNacional.cat|date=21 July 2018|access-date=15 February 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190216040924/https://www.elnacional.cat/es/politica/casado-reconquista-engano-independentismo_290181_102.html|archive-date=16 February 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| At no point did the invading Islamic armies exceed 60,000 men.<ref>{{cite book|last=Fletcher|first=Richard|title=Moorish Spain|year=2006|publisher=Los Angeles: University of California Press|isbn=0-520-24840-6|page=43}}</ref> These armies established an Islamic rule that would last 300 years in much of the Iberian Peninsula and 781 years in ]. | |||

| The same kind of propaganda was circulated during the ] by the ], who wanted to portray their enemies as foreign invaders, especially given the prominence of the ] among Franco's troops, an army which was made up of native North African soldiers.<ref>Bolorinos Allard, Elisabeth. "The Crescent and the Dagger: Representations of the Moorish Other during the Spanish Civil War." ''Bulletin of Spanish Studies'' 93, no. 6 (2016): 965–988.</ref> | |||

| ===Islamic rule=== | |||

| {{Cleanup|reason=original research or plagiarism: numerous factual statements lacking citation|date=November 2013}} | |||

| {{Main|Berbers and Islam|Berber Revolt|}} | |||

| After the establishment of a local ], ] ], ruler of the ], removed many of the successful Muslim commanders. Tariq ibn Ziyad, the first governor of the newly conquered province of ''Al-Andalus'', was recalled to ] and replaced with Musa bin Nusair, who had been his former superior. Musa's son, Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa, apparently married ], ]'s widow, and established his regional government in ]. He was suspected of being under the influence of his wife, accused of wanting to convert to Christianity, and of planning a secessionist rebellion. Apparently a concerned Al-Walid I ordered Abd al-Aziz's assassination. Caliph Al-Walid I died in 715 and was succeeded by his brother ]. Sulayman seems to have punished the surviving Musa bin Nusair, who very soon died during a pilgrimage in 716. In the end Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa's cousin, ] became the emir of ''Al-Andalus''. | |||

| Some contemporary authors{{who|date=June 2019}} consider the "''Reconquista''" proof that the process of Christian state-building in Iberia was frequently defined by the reclamation of lands that had been lost to the ] in generations past. In this way, state-building might be characterised—at least in ideological, if not practical, terms—as a process by which Iberian states were being "rebuilt".<ref name="Purkis">{{cite book |title= Eleventh- and Twelfth-Century Perspectives on State Building in the Iberian Peninsula |last= Purkis |first= William J. |year= 2010 |publisher= University of Birmingham |pages= 57–58 |access-date= 15 October 2017 |url= https://www.reading.ac.uk/web/files/GCMS/RMS-2010-05_W._J._Purkis,_Eleventh-_and_Twelfth-Century_Perspectives_on_State_Building_in_the_Iberian_Peninsula.pdf |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20171016070114/https://www.reading.ac.uk/web/files/GCMS/RMS-2010-05_W._J._Purkis,_Eleventh-_and_Twelfth-Century_Perspectives_on_State_Building_in_the_Iberian_Peninsula.pdf |archive-date= 16 October 2017 |url-status= live }}</ref> In turn, other recent historians dispute the whole concept of "''Reconquista''" as a concept created ''a posteriori'' in the service of later political goals. A few historians point out that Spain and Portugal did not previously exist as nations, and therefore the heirs of the Christian ] were not technically ''re''conquering them, as the name suggests.<ref>Eugènia de Pagès, "''La 'Reconquista', allò que mai no va existir''", ''La Lamentable'', 11 July 2014, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170828161547/http://lamentable.org/la-reconquista-allo-que-mai-no-va-existir/ |date=28 August 2017 }}</ref><ref>Martín M. Ríos Saloma, "''La Reconquista. Génesis de un mito historiográfico''", ''Historia y Grafía'', 30, 2008, pp. 191–216, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304053429/http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/589/58922939009.pdf |date=4 March 2016 }}, Retrieved 12 October 2014.</ref> One of the first Spanish intellectuals to question the idea of a "reconquest" that lasted for eight centuries was ], writing in the first half of the 20th century.<ref>"''Yo no entiendo cómo se puede llamar reconquista a una cosa que dura ocho siglos''" ("I don't understand how something that lasted eight centuries can be called a reconquest"), in ''España invertebrada''. Quoted by De Pagès, E. 11 July 2014.</ref> However, the term ''Reconquista'' is still widely in use.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Horswell |first1=Mike |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KI6lDwAAQBAJ&dq=reconquista+nowadays&pg=PT64 |title=The Crusades in the Modern World: Engaging the Crusades, Volume Two |last2=Awan |first2=Akil N. |date=2019 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-351-25046-7 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| The conquering generals were necessarily acting very independently, due to the methods of communication available. Successful generals in the field and in a very distant province would also gain the personal loyalty of their officers and warriors and their ambitions were probably always watched by certain circles of the distant government with a certain degree of concern and suspicion. Old rivalries and perhaps even full-fledged conspiracies between rival generals may have had influence over this development. In the end, the old successful generals were replaced by a younger generation considered more loyal by the government in ]. | |||

| == History and military campaigns== | |||

| A serious weakness amongst the Muslim conquerors was the ethnic tension between ] and ]s.<ref>], ''A Vanished World: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Medieval Spain'', (Oxford University Press, 2005), 40.</ref> The Berbers were indigenous inhabitants of North Africa who had only recently been converted to Islam; they had provided most of the soldiery of the invading Islamic armies but sensed Arab discrimination against them.<ref>Roger Collins, ''Early Medieval Spain'', (St.Martin's Press, 1995), 164.</ref> This latent internal conflict jeopardized Muslim unity. | |||

| === Background === | |||

| After the Islamic Moorish conquest of nearly all of the Iberian Peninsula in 711-718 and the establishment of the emirate of ''Al-Andalus'', an Umayyad expedition suffered a major defeat at the ] and was halted for a while on its way north. ] had married his daughter to ], a rebel Berber and lord of ] (maybe of all current Catalonia too), in an attempt to secure his southern borders in order to fend off ]´s attacks on the north. However, a major ] led by ], the latest emir of ''Al-Andalus'', defeated and killed Uthman, and the Muslim governor mustered an expedition north across the western Pyrenees, looted areas up to Bordeaux, and defeated Odo in the ] in 732. | |||

| {{Further|Islam in Spain}} | |||

| ====Landing in Visigothic Hispania and initial expansion==== | |||

| A desperate Odo turned to his archrival ] for help, who led the Frankish and leftover Aquitanian armies against and defeated the Umayyad armies at the ] in 732, killing Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi. Moorish rule began to recede, but it would remain in parts of the Iberian peninsula for another 760 years. | |||

| {{Further|Umayyad conquest of Hispania|Battle of Guadalete}} | |||

| In 711, North African ] soldiers with some ]s commanded by ] crossed the ], engaging a Visigothic force led by King ] at the ] (July 19–26) in a moment of severe in-fighting and division across the ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Nick |date=2022-11-10 |title=Battle of Guadalete: 2 Reasons It Changed History |url=https://thehistoryace.com/battle-of-guadalete-2-reasons-it-changed-history/ |access-date=2023-06-16 |website=The History Ace |language=en-us}}</ref> Many of Roderic's troops deserted, leading to his defeat. He drowned while crossing the ]. | |||

| ===Beginning of the ''Reconquista'' === | |||

| {{Main|Kingdom of Asturias}} | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=January 2014}} | |||

| {{disputed section|date=January 2014}} | |||

| The year 722 saw the first ] victory against the Muslims. A drastic increase of taxes by the new emir ] had provoked several rebellions in Al-Andalus, which a series of succeeding weak emirs was unable to suppress. Around 722, a military expedition was sent into the north to suppress Pelayo's rebellion, but his forces prevailed in the ]. In late summer, a Muslim army overran much of ]'s territory, forcing him to retreat deep into the mountains. Pelayo and a few hundred men retired into a narrow valley at ]. There, they could defend against a broad frontal attack. From here, Pelayo's forces routed the Muslim army, inspiring local villagers to take up arms. Despite further attempts, the Muslims were unable to conquer Pelayo's mountain stronghold. Pelayo's ] is hailed as the beginning of the Reconquista. | |||

| After Roderic's defeat, the Umayyad governor of ] ] joined Tariq, directing a campaign against different towns and strongholds in Hispania. Some, like ], ], or ] in 712, probably ], were taken, but many agreed to a treaty in exchange for maintaining autonomy, in ]'s dominion (region of Tudmir), or ], for example.{{sfn|Collins|1989|pp=38–45}} The invading Islamic armies did not exceed 60,000 men.<ref>{{cite book|last=Fletcher|first=Richard|title=Moorish Spain|year=2006|publisher=Los Angeles: University of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-24840-3|page=|url=https://archive.org/details/moorishspain00rich/page/43}}</ref> | |||

| This battle was considered by the Muslims as little more than a skirmish, since no Muslim source mentions it, while the ], with a death toll of maybe tens of thousands, was mourned for centuries as a large scale tragedy by the Iberian Muslims. However, for Pelayo, the Christian victory secured his independent rule. The precise date and circumstances of this battle are unclear. Among the possibilities is that Pelayo's rebellion was successful because the greater part of the Muslim forces were gathering for an invasion of the Frankish empire. | |||

| ]. ], Spain. Depicting ]]] | |||

| ====Islamic rule==== | |||

| During the first decades, Asturian control over the different areas of the kingdom was still weak, and for this reason it had to be continually strengthened through matrimonial alliances with other powerful families from the north of the Iberian Peninsula. Thus, "Ermesinda, Pelayo's daughter, was married to Alfonso, Peter of Cantabria's son. Alphonse's children, Froila and Adosinda, married Munia, a Basque from Alava, and Silo, a local chief from the area of Pravia, respectively." <ref>(quote from 'The making of medieval Spain'),</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Berbers and Islam|Berber Revolt|}} | |||

| ] in the early 10th century]] | |||

| After the establishment of a local ], ] ], ruler of the ], removed many of the successful Muslim commanders. Tariq ibn Ziyad was recalled to ] and replaced with Musa ibn-Nusayr, who had been his former superior. Musa's son, Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa, apparently married ], ]'s widow, and established his regional government in ]. He was suspected of being under the influence of his wife and was accused of wanting to convert to Christianity and of planning a secessionist rebellion. Apparently a concerned Al-Walid I ordered Abd al-Aziz's assassination. Caliph Al-Walid I died in 715 and was succeeded by his brother ]. Sulayman seems to have punished the surviving Musa ibn-Nusayr, who very soon died during a pilgrimage in 716. In the end, Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa's cousin, ] became the ''wali'' (governor) of al-Andalus.{{citation needed|date=August 2020}} | |||

| A serious weakness amongst the Muslim conquerors was the ethnic tension between Berbers and Arabs.<ref>], ''A Vanished World: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Medieval Spain'', (Oxford University Press, 2005), 40.</ref> The Berbers were indigenous inhabitants of North Africa who had only recently converted to Islam; they provided most of the soldiery of the invading Islamic armies but sensed Arab discrimination against them.<ref>Roger Collins, ''Early Medieval Spain'', (St. Martin's Press, 1995), 164.</ref> This latent internal conflict jeopardised Umayyad unity. The Umayyad forces arrived and crossed the Pyrenees by 719. The last Visigothic king ] resisted them in Septimania, where he fended off the Berber-Arab armies until 720.<ref>{{cite book | author = Collins, Roger| year = 1989 | title = The Arab Conquest of Spain 710–797 | publisher = Blackwell |location = Oxford, UK / Cambridge, US|isbn= 978-0-631-19405-7|page=45}}</ref> | |||

| After Pelayo's death in 737, his son ] was elected king. Favila, according to the chronicles, was killed by a bear during a trial of courage. | |||

| After the Islamic Moorish conquest of most of the Iberian Peninsula in 711–718 and the establishment of the emirate of al-Andalus, an Umayyad expedition suffered a major defeat at the ] and was halted for a while on its way north. ] had married his daughter to ], a rebel Berber and lord of ], in an attempt to secure his southern borders in order to fend off ]'s attacks on the north. However, a major ] led by ], the latest emir of al-Andalus, defeated and killed Uthman, and the Muslim governor mustered an expedition north across the western Pyrenees, looted areas up to Bordeaux, and defeated Odo in the ] in 732.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Reconquista {{!}} Map and Timeline |url=https://history-maps.com/story/Reconquista |access-date=2023-06-16 |website=HistoryMaps |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Pelayo's dynasty in Asturias survived and gradually expanded the kingdom's boundaries until all of northwest Iberia was included by roughly 775. However, credit is due not to him but to his successors. Alfonso I (king from 739-757) rallied Galician support when driving the Moorish army out of Galicia and an area of what was to become Leon. The reign of Alfonso II (from 791-842) saw further expansion of the northwest kingdom towards the south and, for a short time, it almost reached Lisbon. | |||

| A desperate Odo turned to his archrival Charles Martel for help, who led the Frankish and remaining Aquitanian armies against the Umayyad armies and defeated them at the ] in 732, killing Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi. While Moorish rule began to recede in what is today France, it would remain in parts of the Iberian peninsula for another 760 years.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Trawinski |first1=Allan |title=The Clash of Civilizations |year= 2017 |publisher=Page Publishing Inc. |isbn=978-1635687125}}{{page needed|date=May 2023}}</ref> | |||

| It was not until Alfonso II that the kingdom was firmly established with Alfonso's recognition as king of Asturias by Charlemagne and the Pope. During his reign, the bones of ] were declared (falsely<ref>T. D. Kendrick, ''Saint James in Spain'', London, Methuen, 1960, no ISBN (predates system).</ref>) to have been found in Galicia, at ]. Pilgrims from all over Europe opened a channel of communication between the isolated Asturias and the Carolingian lands and beyond. | |||

| ===Early Reconquista=== | |||

| The two resistances, Basque Navarre and Cantabrian Asturias, despite their small size, demonstrated an ability to maintain their independence. Because the Umayyad rulers based in ] were unable to extend their power over the Pyrenees, they decided to consolidate their power within the Iberian peninsula. Arab-Berber forces made periodic incursions deep into Asturias but failed to make any lasting gains against the strengthened Christian kingdoms. | |||

| ==== Beginning of the ''Reconquista'' ==== | |||

| {{Main|Kingdom of Asturias}} | |||

| A drastic increase of taxes on Christians by the emir ] provoked several rebellions in al-Andalus, which a series of succeeding weak emirs were unable to suppress. Around 722, a Muslim military expedition was sent into the north in late summer to suppress a rebellion led by ] (Pelayo in Spanish, Pelayu in Asturian). Traditional historiography has hailed Pelagius's ] as the beginning of the ''Reconquista''.<ref>{{Citation |title=Covadonga, la batalla que cambió la historia de España |date=2022-05-27 |url=https://www.rtve.es/play/videos/panorama-regional/covadonga-la-batalla-que-cambio-la-historia-de-espana/6549431/ |language=es |access-date=2022-08-11}}</ref> | |||

| Two northern realms, Navarre<ref>{{cite book | author = Collins, Roger| year = 1989 | title = The Arab Conquest of Spain 710–797 | publisher = Blackwell |location = Oxford, UK / Cambridge, US|isbn= 978-0-631-19405-7|page=181}}</ref> and Asturias, despite their small size, demonstrated an ability to maintain their independence. Because the Umayyad rulers based in ] were unable to extend their power over the Pyrenees, they decided to consolidate their power within the Iberian peninsula. Arab-Berber forces made periodic incursions deep into Asturias, but this area was a ''cul-de-sac'' on the fringes of the Islamic world fraught with inconveniences during campaigns and of little interest.<ref>{{cite book | author = Collins, Roger| year = 1989 | title = The Arab Conquest of Spain 710–797 | publisher = Blackwell |location = Oxford, UK / Cambridge, US|isbn= 978-0-631-19405-7|page=156}}</ref> | |||

| ===Franks and ''Al-Andalus''=== | |||

| {{Main|Islamic invasion of Gaul|Marca Hispanica}} | |||

| After the Umayyad conquest of the Iberian heartland of the Visigothic kingdom, the Muslims crossed the Pyrenees and gradually took control of ] starting in 719 (Narbonne conquered) up to 725 (Carcassone, Nîmes). From its stronghold of Narbonne, they tried to conquer ] but suffered a major defeat at the ]. | |||

| It comes then as no surprise that, besides focusing on raiding the Arab-Berber strongholds of the Meseta, ] centred on expanding his domains at the expense of the neighbouring Galicians and Basques at either side of his realm just as much.<ref>{{cite book | author = Collins, Roger| year = 1989 | title = The Arab Conquest of Spain 710–797 | publisher = Blackwell |location = Oxford, UK / Cambridge, US|isbn= 978-0-631-19405-7|pages=156, 159}}</ref> During the first decades, Asturian control over part of the kingdom was weak, and for this reason it had to be continually strengthened through matrimonial alliances and war with other peoples from the north of the Iberian Peninsula. After Pelayo's death in 737, his son ] was elected king. Favila, according to the chronicles, was killed by a bear during a trial of courage. Pelayo's dynasty in Asturias survived and gradually expanded the kingdom's boundaries until all of northwest Hispania was included by roughly 775. However, credit is due to him and to his successors, the ''Banu Alfons'' from the Arab chronicles. Further expansion of the northwestern kingdom towards the south occurred during the reign of ] (from 791 to 842). A king's expedition arrived in and pillaged Lisbon in 798, probably concerted with the Carolingians.<ref>{{cite book | author = Collins, Roger| year = 1989 | title = The Arab Conquest of Spain 710–797 | publisher = Blackwell |location = Oxford, UK / Cambridge, US|isbn= 978-0-631-19405-7|page=212}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| After halting their advance north, ten years later, ] married his daughter to ], a rebel Berber and lord of ] (maybe of all current Catalonia too), in an attempt to secure his southern borders in order to fend off ]'s attacks on the north. However, a major ] led by ], the latest emir of Al-Andalus, defeated and killed Uthman. | |||

| The Asturian kingdom became firmly established with the recognition of Alfonso II as king of Asturias by ] and the Pope. During his reign, the bones of ] were declared to have been found in Galicia, at ]. Pilgrims from all over Europe opened a channel of communication between the isolated Asturias and the Carolingian lands and beyond, centuries later.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2021-07-31 |title=The Way of St. James – Bodega Tandem |url=https://tandem.es/en/camino/ |access-date=2022-08-11 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210731161327/https://tandem.es/en/camino/ |archive-date=31 July 2021 }}</ref> | |||

| ==== Charles Martel ==== | |||

| The Umayyad governor mustered an expedition north across the western Pyrenees, looted its way up to Bordeaux and defeated Odo in the ] in 732. A desperate Odo turned to his archrival ] for help, who led the Frankish and remaining Aquitanian armies against the Muslims and beat them at the ] in 732, killing Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi. | |||

| ====Frankish invasions==== | |||

| In 737 Charles Martel led an expedition south down the Rhone Valley to assert his authority up to the lands held by the Al-Andalus Umayyads. These had been called in by the regional nobility of Provence in a military capacity, probably fearing Charles' expansionist ambitions. Charles went on to attack the Umayyads in Septimania up to Narbonne, but he had to lift the siege of the city and make his way back to Lyon and ] (at the time north of the lower Loire) after subduing various Umayyad strongholds, such as Arles, Avignon and Nîmes, not without leaving behind a trail of ruined towns and strongholds. | |||

| {{Main|Umayyad invasion of Gaul|Marca Hispanica}} | |||

| After the Umayyad conquest of the Iberian heartland of the Visigothic kingdom, the Muslims crossed the Pyrenees and gradually took control of ], starting in 719 with the conquest of ] through 725 when ] and ] were secured. From the stronghold of Narbonne, they tried to conquer ] but suffered a major defeat at the ].<ref name="Lewis AR 20-33">{{cite book|title=The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718–1050|last=Lewis|first=Archibald R.|author-link=Archibald Ross Lewis|year=1965|publisher=The University of Texas Press|pages=20–33|access-date=28 October 2017|url=http://libro.uca.edu/lewis/sfcatsoc.htm|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171211183903/http://libro.uca.edu/lewis/sfcatsoc.htm|archive-date=11 December 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Pepin the Younger and Charlemagne ==== | |||

| After expelling the Muslims ] and driving their forces back over the Pyrenees, the Carolingian king ] in a ruthless eight-year war. Charlemagne followed his father by subduing Aquitaine by creating counties, taking the Church as his ally and appointing counts of Frankish or Burgundian stock, like his loyal ], making ] his base for expeditions against Al-Andalus. | |||

| Ten years after halting their advance north, ] married his daughter to ], a rebel Berber and lord of ] (perhaps all of contemporary Catalonia as well), in an attempt to secure his southern borders to fend off ]'s attacks on the north. However, a major ] led by ], the latest emir of al-Andalus, defeated and killed Uthman.<ref name="Lewis AR 20-33"/> | |||

| Charlemagne decided to organize a regional subkingdom in order to keep the Aquitanians in check and to secure the southern border of the ] against Muslim incursions. In 781, his three-year-old son ] was crowned king of ], under the supervision of Charlemagne's trustee William of Gellone, and was nominally in charge of the incipient ]. | |||

| After expelling the Muslims ] and driving their forces back over the Pyrenees, the Carolingian king ] in a ruthless eight-year war. Charlemagne followed his father by subduing Aquitaine by creating counties, taking the Church as his ally and appointing counts of Frankish or Burgundian stock, like his loyal ], making ] his base for expeditions against al-Andalus.<ref name="Lewis AR 20-33"/> Charlemagne decided to organize a regional subkingdom, the ], which included part of contemporary ], in order to keep the Aquitanians in check and to secure the southern border of the ] against Muslim incursions. In 781, his three-year-old son ] was crowned king of ], under the supervision of Charlemagne's trustee William of Gellone, and was nominally in charge of the incipient Spanish March.<ref name="Lewis AR 20-33"/> | |||

| Meanwhile, the takeover of the southern fringes of Al-Andalus by Abd ar-Rahman I in 756 was opposed by ], autonomous governor ('']'') or king (''malik'') of al-Andalus. Abd ar-Rahman I expelled Yusuf from Cordova, but it took still decades for him to expand to the north-western Andalusian districts. He was also opposed externally by the ] of Damascus who failed in their attempts to overthrow him. | |||

| In 778, Abd al-Rahman closed in on the Ebro valley. Regional lords saw the Umayyad emir |

Meanwhile, the takeover of the southern fringes of al-Andalus by Abd ar-Rahman I in 756 was opposed by ], autonomous governor ('']'') or king (''malik'') of al-Andalus. Abd ar-Rahman I expelled Yusuf from Cordova,<ref>{{cite book | author = Collins, Roger| year = 1989 | title = The Arab Conquest of Spain 710–797 | publisher = Blackwell |location = Oxford, UK / Cambridge, US|isbn= 978-0-631-19405-7|pages=118–126}}</ref> but it took still decades for him to expand to the north-western Andalusian districts. He was also opposed externally by the ] of Baghdad who failed in their attempts to overthrow him. In 778, Abd al-Rahman closed in on the Ebro valley. Regional lords saw the Umayyad emir at the gates and decided to enlist the nearby Christian Franks. According to ], a Kurdish historian of the 12th century, Charlemagne received the envoys of ], Husayn, and ] at the Diet of Paderborn in 777. These rulers of ], ], ], and ] were enemies of Abd ar-Rahman I, and in return for Frankish military aid against him offered their homage and allegiance.<ref name="Collins, Roger 1989 177–181">{{cite book | author = Collins, Roger| year = 1989 | title = The Arab Conquest of Spain 710–797 | publisher = Blackwell |location = Oxford, UK / Cambridge, US|isbn= 978-0-631-19405-7|pages=177–181}}</ref> | ||

| ] | |||

| Charlemagne, seeing an opportunity, agreed upon an expedition and crossed the Pyrenees in 778. Near the city of ] Charlemagne received the homage of ]. However the city, under the leadership of ], closed its gates and refused to submit. Unable to conquer the city by force, Charlemagne decided to retreat. On the way home the rearguard of the army was ambushed and destroyed by local forces at the ]. ], a highly romanticized account of this battle, would later become one of the most famous ] of the Middle Ages. | |||

| Charlemagne, seeing an opportunity, agreed upon an expedition and crossed the Pyrenees in 778. Near the city of ] Charlemagne received the homage of ]. However the city, under the leadership of ], closed its gates and refused to submit.<ref name="Collins, Roger 1989 177–181"/> Unable to conquer the city by force, Charlemagne decided to retreat. On the way home the rearguard of the army was ambushed and destroyed by Basque forces at the ]. '']'', a highly romanticised account of this battle, would later become one of the most famous {{lang|fro|]}} of the Middle Ages. Around 788 Abd ar-Rahman I died and was succeeded by ]. In 792 Hisham proclaimed a ], advancing in 793 against the ] and Carolingian ]. They defeated William of Gellone, Count of Toulouse, in battle, but ] led an expedition the following year across the eastern Pyrenees. ], a major city, became a potential target for the Franks in 797, as its governor Zeid rebelled against the Umayyad emir of Córdoba. An army of the emir managed to recapture it in 799, but Louis, at the head of an army, crossed the Pyrenees and ] until it finally capitulated in 801.<ref name="Lewis AR 37-49">{{cite book|title=The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718–1050|last=Lewis|first=Archibald R.|author-link=Archibald Ross Lewis|year=1965|publisher=The University of Texas Press|pages=37–49|access-date=28 October 2017|url=http://libro.uca.edu/lewis/sfcatsoc.htm|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171211183903/http://libro.uca.edu/lewis/sfcatsoc.htm|archive-date=11 December 2017|url-status=live}} It took place on 28 December 801.</ref> | |||

| The main passes in the Pyrenees were ], ] and ]. Charlemagne established across them the vassal regions of ], ], and ] respectively. Catalonia was itself formed from a number of ], including ], ], and ]; it was called the ''Marca Hispanica'' by the late 8th century. They protected the eastern Pyrenees passes and shores and were under the direct control of the Frankish kings. Pamplona's first king was ], who allied with his Muslim kinsmen the ] and rebelled against Frankish overlordship and overcame a ] that led to the setup of the ]. Aragon, founded in 809 by ], grew around ] and the high valleys of the ], protecting the old Roman road. By the end of the 10th century, Aragon, which then was just a county, was annexed by Navarre. Sobrarbe and Ribagorza were small counties and had little significance to the progress of the ''Reconquista''.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Archaeology |url=https://perennialpyrenees.com/category/archaeology/ |access-date=2023-06-16 |website=Perennial Pyrenees |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Around 788 Abd ar-Rahman I died, and was succeeded by ]. In 792 Hisham proclaimed a ], advancing in 793 against the ] and the Franks. In the end his efforts were turned back by ], Count of Toulouse. | |||

| In the late 9th century under ], Barcelona became the ''de facto'' capital of the region. It controlled the other counties' policies in a union, which led in 948 to the independence of Barcelona under ], who declared that the new dynasty in France (the ]s) were not the legitimate rulers of France nor, as a result, of his county. These states were small and, with the exception of Navarre, did not have the capacity for attacking the Muslims in the way that Asturias did, but their mountainous geography rendered them relatively safe from being conquered, and their borders remained stable for two centuries.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Counts – The Origins of Catalonia |url=https://www.autentic.com/65/pid/880/Counts-The-Origins-of-Catalonia.htm |access-date=2023-06-16 |website=www.autentic.com}}</ref> | |||

| ], a major city, became a potential target for the Franks in 797, as its governor Zeid rebelled against the Umayyad emir of Córdoba. An army of the emir managed to recapture it in 799 but Louis, at the head of an army, crossed the Pyrenees and besieged the city for two years until the city finally capitulated on December 28, 801. | |||

| ===Northern Christian realms=== | |||

| The main passes were ], ] and ]. Charlemagne established across them the vassal regions of ], ] and ] (which was itself formed from a number of small counties, ], ], and ] being the most prominent) respectively. | |||

| {{see also|Spain in the Middle Ages#Medieval Christian Spain|Portugal in the Middle Ages#Reconquista in Portugal}} | |||

| The northern principalities and kingdoms survived in their mountainous strongholds (see above). However, they started a definite territorial expansion south at the turn of the 10th century (Leon, Najera). The fall of the Caliphate of Cordova (1031) heralded a period of military expansion for the northern kingdoms, now divided into several mighty regional powers after the division of the Kingdom of Navarre (1035). Myriad autonomous Christian kingdoms emerged thereafter.<ref>{{cite web |title=Kingdom of Navarre |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Kingdom-of-Navarre |website=Encyclopedia Britannica |access-date=27 October 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ====Kingdom of Asturias (718–924)==== | |||

| Four small realms pledged allegiance to Charlemagne at the start of the 9th century (not for long): ] (to become ]) and the counties of ], ] and ]. Pamplona's first king was ], who allying with his Muslim kinsmen the ] rebelled against Frankish overlordship, and overcame a Frankish expedition in 824 that led to the setup of the Kingdom of Pamplona. It was not until ] in the 9th century that Pamplona was officially recognised as an independent kingdom by the ]. Aragon, founded in 809 by ], grew around Jaca and the high valleys of the ], protecting the old Roman road. By the end of the 10th century, Aragon was annexed by Navarre. Sobrarbe and Ribagorza were small counties and had little significance to the progress of the ''Reconquista''. | |||

| {{Main|Kingdom of Asturias}} | |||

| {{See also|Kingdom of Galicia|Duchy of Cantabria}} | |||

| The Kingdom of Asturias was located in the ], a wet and mountainous region in the north of the Iberian Peninsula. It was the first Christian power to emerge. The kingdom was established by a Visigothic nobleman, named Pelagius (''Pelayo''), who had possibly returned after the Battle of Guadalete in 711 and was elected leader of the Asturians,<ref name="Peña p. 27">Ruiz De La Peña. La monarquia asturiana 718–910, p. 27. Cangas de Onís, 2000. {{ISBN|9788460630364}} / Fernández Conde. Estudios Sobre La Monarquía Asturiana, pp. 35–76. Estudios Históricos La Olmeda, 2015. {{ISBN|978-8497048057}}</ref> and the remnants of the ''gens Gothorum'' (the Hispano-Gothic aristocracy and the Hispano-Visigothic population who took refuge in the North). Historian Joseph F. O'Callaghan says an unknown number of them fled and took refuge in Asturias or Septimania. In Asturias they supported Pelagius's uprising, and joining with the indigenous leaders, formed a new ]. | |||

| The population of the mountain region consisted of native Astures, Galicians, Cantabri, Basques and other groups unassimilated into Hispano-Gothic society,<ref name="O'Callaghan2013176">{{cite book|author=Joseph F. O'Callaghan|title=A History of Medieval Spain|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cq2dDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA176|year=2013|publisher=Cornell University Press|isbn=978-0-8014-6872-8|page=176}}</ref> laying the foundations for the Kingdom of Asturias and starting the ] that spanned from 718 to 1037 and led the initial efforts in the Iberian peninsula to take back the territories then ruled by the Moors.<ref name="Peña p. 27"/> Although the new dynasty first ruled in the mountains of Asturias, with the capital of the kingdom established initially in ], and was in its dawn mostly concerned with securing the territory and settling the monarchy, the latest kings (particularly ]) emphasised the nature of the new kingdom as heir of that in ] and the restoration of the Visigothic nation in order to vindicate the expansion to the south.<ref>Casariego, J.E.: ''Crónicas de los reinos de Asturias y León''. Biblioteca Universitaria Everest, León 1985, p. 68. {{ASIN|B00I78R3S4}}{{ISBN missing}}</ref> However, such claims have been overall dismissed by modern historiography, emphasizing the distinct, autochthonous nature of the Cantabro-Asturian and Vasconic domains with no continuation to the Gothic Kingdom of Toledo.<ref>García Fitz, Francisco. 2009, pp. 149–150</ref> | |||

| The ] protected the eastern Pyrenees passes and shores. They were under the direct control of the Frankish kings and were the last remains of the Spanish Marches. ] included not only the southern Pyrenees counties of Girona, Pallars, Urgell, ] and ] but also some which were on the northern side of the mountains, such as ] and ]. | |||

| Pelagius's kingdom initially was little more than a gathering point for the existing guerrilla forces. During the first decades, the Asturian dominion over the different areas of the kingdom was still lax, and for this reason it had to be continually strengthened through matrimonial alliances with other powerful families from the north of the Iberian Peninsula. Thus, Ermesinda, Pelagius's daughter, was married to ], ]'s son. Alfonso's son ] married Munia, a Basque from ], after crushing a Basque uprising (probably resistance). Their son is reported to be ], while Alfonso I's daughter Adosinda married Silo, a local chief from the area of Flavionavia, Pravia.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2021-01-02 |title=What was the Reconquista? – Boot Camp & Military Fitness Institute |url=https://bootcampmilitaryfitnessinstitute.com/2021/01/02/what-was-the-reconquista/ |access-date=2023-06-16 |website=bootcampmilitaryfitnessinstitute.com |language=en-GB}}</ref> | |||

| In the late 9th century under ], Barcelona became the ''de facto'' capital of the region. It controlled the other counties' policies in a union, which led in 948 to the independence of Barcelona under ], who declared that the new dynasty in France (the ]s) were not the legitimate rulers of France nor, as a result, of his county. | |||

| Alfonso's military strategy was typical of Iberian warfare at the time. Lacking the means needed for wholesale conquest of large territories, his tactics consisted of raids in the border regions of ]. With the plunder he gained further military forces could be paid, enabling him to raid the Muslim cities of ], ], and ]. Alfonso I also expanded his realm westwards conquering ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=O'Callaghan |first=Joseph F. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cq2dDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA176 |title=A History of Medieval Spain |year=2013 |publisher=Cornell University Press |isbn=978-0-8014-6872-8 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| These states were small and, with the exception of Navarre, did not have the capacity for attacking the Muslims in the way that Asturias did, but their mountainous geography rendered them relatively safe from being conquered. Their borders remained stable for two centuries. | |||

| ] depicted as ]. Legend of the ''Reconquista''|alt=]] | |||

| ==Military culture in medieval Iberia== | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=December 2012}} | |||

| ], ] Sultan of ], at the ], 1431]] | |||

| In a situation of constant conflict, warfare and daily life were strongly interlinked during this period. Small, lightly equipped armies reflected how the society had to be on the alert at all times. These forces were capable of moving long distances in short times, allowing a quick return home after sacking a target. Battles which took place were mainly between clans, expelling intruder armies or sacking expeditions. | |||

| During the reign of ] (791–842), the kingdom was firmly established, and a series of Muslim raids caused the transfer of the Asturian capital to ]. The king is believed to have initiated diplomatic contacts with the kings of ] and the ]s, thereby gaining official recognition for his kingdom and his crown from the ] and ].<ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-03-24 |title=Alfonso II, Charlemagne and the Jacobean Cult (full text in Spanish) |url=http://oppidum.es/oppidum-17/opp17.12_larranaga_alfonso.ii,.carlomagno.y.el.culto.jacobeo.pdf |access-date=2022-08-11 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220324174530/http://oppidum.es/oppidum-17/opp17.12_larranaga_alfonso.ii,.carlomagno.y.el.culto.jacobeo.pdf |archive-date=24 March 2022 }}</ref> | |||

| In the context of the relative isolation of the Iberian Peninsula from the rest of Europe, and the contact with Moorish culture, geographical and cultural differences implied the use of military strategies, tactics and equipment that were markedly different from those found in the rest of western Europe during this period. | |||

| The ] of St. ] were proclaimed to have been found in Iria Flavia (present day ]) in 813 or probably two or three decades later. The cult of the saint was transferred later to ] (from Latin ''campus stellae'', literally "the star field"), possibly in the early 10th century when the focus of Asturian power moved from the mountains over to Leon, to become the ] or Galicia-Leon. Santiago's were among many saint relics proclaimed to have been found across north-western Hispania. Pilgrims started to flow in from other Iberian Christian realms, sowing the seeds of the later ] (11–12th century) that sparked the enthusiasm and religious zeal of continental ] for centuries.{{Citation needed|date=April 2022}} | |||

| Medieval Iberian armies mainly comprised two types of forces: the cavalry (mostly nobles, but including commoner knights from 10th century on) and the infantry, or ''peones'' (peasants). Infantry only went to war if needed, which was not common. | |||

| Despite numerous battles, neither the Umayyads nor the Asturians had sufficient forces to secure control over these northern territories. Under the reign of ], famed for the highly legendary ], the border began to slowly move southward and Asturian holdings in ], Galicia, and ] were fortified, and an intensive program of re-population of the countryside began in those territories. In 924 the Kingdom of Asturias became the ], when Leon became the seat of the royal court (it didn't bear any official name).<ref>{{cite book | author = Collins, Roger| year = 1983 | title = Early Medieval Spain | publisher = St. Martin's Press |location = New York|isbn= 0-312-22464-8|page = 238}}</ref> | |||

| === Cavalry and infantry === | |||

| Iberian ] involved knights approaching the enemy and throwing ]s, before withdrawing to a safe distance before commencing another assault. Once the enemy formation was sufficiently weakened, the knights charged with thrusting ]s (]s did not arrive in Hispania until the 11th century). There were three types of knights: royal knights, noble knights ('']'') and commoner knights ('']''). Royal knights were mainly nobles with a close relationship with the king, and thus claimed a direct Gothic inheritance. | |||

| ====Kingdom of León (910–1230)==== | |||

| Royal knights were equipped in the same manner as their ] predecessors—braceplate, kite shield, a long ] (designed to fight from the horse) and as well as the javelins and spears, a ]. Noble knights came from the ranks of the ''infanzones'' or lower nobles, whereas the commoner knights were not noble, but were wealthy enough to afford a horse. Uniquely in Europe, these horsemen comprised a militia cavalry force with no feudal links, being under the sole control of the king or the count of ] because of the "]s" (or '']''). Both noble and common knights wore leather armour and carried javelins, spears and round-tasselled shields (influenced by Moorish shields), as well as a sword. | |||

| {{Main|Kingdom of León|Kingdom of Galicia|County of Portugal|Portugal in the Reconquista}} | |||

| ] repopulated the strategically important city ] and established it as his capital. King Alfonso began a series of campaigns to establish control over all the lands north of the ] river. He reorganised his territories into the major duchies (] and Portugal) and major counties (] and Castile), and fortified the borders with many castles. At his death in 910 the shift in regional power was completed as the kingdom became the ]. From this power base, his heir ] was able to organize attacks against ] and even ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Chapter Four |url=http://somosprimos.com/michaelperez/ribera4/ribera4.htm |access-date=2023-06-16 |website=somosprimos.com}}</ref> | |||

| The ] was gaining power, and began to attack Leon. King Ordoño allied with Navarre against Abd-al-Rahman, but they were ] in 920. For the next 80 years, the Kingdom of León suffered civil wars, Moorish attack, internal intrigues and assassinations, and the partial independence of Galicia and Castile, thus delaying the reconquest and weakening the Christian forces. It was not until the following century that the Christians started to see their conquests as part of a long-term effort to restore the unity of the Visigothic kingdom.{{Citation needed|date=April 2022}} | |||

| The ''peones'' were ] who went to battle in service of their ] lord. Poorly equipped, with bows and arrows, spears and short swords, they were mainly used as auxiliary troops. Their function in battle was to contain the enemy troops until the cavalry arrived and to block the enemy infantry from charging the knights. | |||

| The only point during this period when the situation became hopeful for Leon was the reign of ]. King Ramiro, in alliance with ] and his retinue of ''caballeros villanos'', ] in 939. After this battle, when the Caliph barely escaped with his guard and the rest of the army was destroyed, King Ramiro obtained 12 years of peace, but he had to give González the independence of Castile as payment for his help in the battle. After this defeat, Moorish attacks abated until ] began his campaigns. ] finally regained control over his domains in 1002. Navarre, though attacked by Almanzor, remained intact.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Fernán González {{!}} count of Castile {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Fernan-Gonzalez |access-date=2023-06-16 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| The ], the ] and the ] are the basic types of bows and especially popular in infantry. | |||

| The conquest of Leon did not include Galicia which was left to temporary independence after the withdrawal of the Leonese king. Galicia was conquered soon after (by Ferdinand, son of Sancho the Great, around 1038). Subsequent kings titled themselves kings of Galicia and Leon, instead of merely king of Leon as the two were in a ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Sancho III (king of Navarre) {{!}} Encyclopedia.com |url=https://www.encyclopedia.com/reference/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/sancho-iii-king-navarre |access-date=2023-06-16 |website=www.encyclopedia.com}}</ref> | |||

| Typically armour was made of leather, with iron scales; full coats of ] were extremely rare and horse ] completely unknown. Head protections consisted of a round helmet with nose protector (influenced by the designs used by ]s who attacked during the 8th and 9th centuries) and a chain mail headpiece. Shields were often round or kidney-shaped, except for the kite-shaped designs used by the royal knights. Usually adorned with geometric designs, crosses or tassels, shields were made out of wood and had a leather cover. | |||

| At the end of the 11th century, King ] reached the Tagus (1085), repeating the same policy of alliances and developing collaboration with ] knights. The original '']'' was then complete. His aim was to create a Hispanic empire like the ] (418–720) to reclaim his hegemony over the entire ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=El yermo estratégico del Desierto del Duero – Observatorio de Seguridad y Defensa |url=https://observatorio.cisde.es/archivo/el-yermo-estrategico-del-desierto-del-duero/ |access-date=2024-03-19 |language=es-ES}}</ref> Within this context, the territory between the ] and the ] was repopulated and a western nucleus was formed in ].<ref name=":02">Porto Editora – Reconquista Cristã na Infopédia . Porto: Porto Editora. . Disponível em https://www.infopedia.pt/$reconquista-crista</ref> This marks the beginning of the ] occurred during the reigns of the ] up to the middle of the thirteenth century when the ] was also brought to an end with the ultimate conquering of ] when in March 1249 the city of ] was conquered by ].<ref name=":12">{{Cite web |title=Reconquista Cristã |url=https://historiaonline.com/glossario/reconquista-crista/ |access-date=2024-03-19 |website=História Online |language=pt-PT}}</ref><ref name=":02" /><ref name=":2">{{Cite journal |last=Higounet |first=Charles |date=1953 |title=La Reconquista española y la repoblación del país. Escuela de estudios medievales, Inst. de Estudios pirenaicos |url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/hispa_0007-4640_1953_num_55_2_3359_t1_0206_0000_2 |journal=Bulletin Hispanique |volume=55 |issue=2 |pages=206–208}}</ref><ref name=":32">{{Cite web |title=Reconquista española: qué fue y sus características |url=https://humanidades.com/reconquista-espanola/ |access-date=2024-03-19 |website=humanidades.com/ |language=es-ES}}</ref><ref name=":42">{{Cite web |title=Reconquista da Península Ibérica – Conheça a História |url=https://www.brasilparalelo.com.br/artigos/reconquista-da-peninsula-iberica |access-date=2024-03-19 |website=www.brasilparalelo.com.br |language=pt}}</ref> | |||

| Steel swords were the most common weapon. The cavalry used long double-edged swords and the infantry short, single-edged ones. Guards were either semicircular or straight, but always highly ornamented with geometrical patterns. The spears and javelins were up to 1.5 metres long and had an iron tip. The double-axe, made of iron and 30 cm long and possessing an extremely sharp edge, was designed to be equally useful as a thrown weapon or in close combat. Maces and hammers were not common, but some specimens have remained, and are thought to have been used by members of the cavalry. | |||

| ====Kingdom of Castile (1037–1230)==== | |||

| Finally, mercenaries were an important factor, as many kings did not have enough soldiers available. The ], the ] spearmen, the Frankish knights, the Moorish mounted archers and Berber light cavalry were the main types of mercenary available and used in the conflict. | |||

| {{Main|Kingdom of Castile}} | |||

| ] by ], at the ]]] | |||

| ] was the leading king of the mid-11th century. He conquered ] and attacked the ] kingdoms, often demanding the tributes known as ]. Ferdinand's strategy was to continue to demand parias until the taifa was greatly weakened both militarily and financially. He also repopulated the Borders with numerous ''fueros''. Following the Navarrese tradition, on his death in 1064 he divided his kingdom between his sons. His son ] wanted to reunite the kingdom of his father and attacked his brothers, with a young noble at his side: Rodrigo Díaz, later known as ]. Sancho was killed in the siege of ] by the traitor Bellido Dolfos (also known as Vellido Adolfo) in 1072. His brother ] took over Leon, Castile and Galicia.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Ferdinand I {{!}} king of Castile and Leon {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ferdinand-I-king-of-Castile-and-Leon |access-date=2023-06-16 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref> | |||