| Revision as of 04:25, 12 August 2015 editNareshrana01 (talk | contribs)85 editsNo edit summaryTags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:32, 23 November 2024 edit undoDonchocolate (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users846 editsNo edit summaryTags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| (676 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Fort in Madhya Pradesh, India}} | |||

| {{Disputed|date=May 2024}} | |||

| {{EngvarB|date=September 2013}} | {{EngvarB|date=September 2013}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date= |

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2024}} | ||

| {{Infobox military installation | {{Infobox military installation | ||

| |name |

| name = Fort of Gwalior | ||

| |partof |

| partof = | ||

| |location = ], ] | | location = ], | ||

| ] | |||

| |image |

| image = Gwalior_Fort_front.jpg | ||

| |image_size = |

| image_size = 350 | ||

| | caption = The "Man Mandir" palace built by ] ruler ] (reigned 1486–1516 CE), at Gwalior Fort | |||

| |caption = Man Mandir | |||

| |map_type = India | | map_type = India#India Madhya Pradesh | ||

| | coordinates = {{coord|26.2303|78.1689|type:landmark|display=inline,title}} | |||

| |latitude = 26.2303 | |||

| | map_size = 300 | |||

| |longitude = 78.1689 | |||

| | map_caption = | |||

| |map_size = 300 | |||

| | pushpin_relief = yes | |||

| |map_caption = | |||

| |type = ] | | type = ] | ||

| |code = | | code = | ||

| | built = 6th century, The modern-day fort, consisting a defensive structure and two palaces was built by King ],{{sfn|Paul E. Schellinger|Robert M. Salkin|1994|p=312}} later renovated by Scindias under the Supervision of General Sardar Surve in 1916 | |||

| |built = 8th century and 14th century | |||

| | materials = ] and lime mortar | |||

| |builder = Hindu Kings of India | |||

| | height = | |||

| |materials = ]s and lime mortar | |||

| | used = Yes | |||

| |height = | |||

| | demolished = | |||

| |used = Yes | |||

| | open_to_public = Yes | |||

| |demolished = | |||

| | owner = *] (5th century) | |||

| |condition = Good | |||

| *] (9th century) | |||

| |open_to_public = Yes | |||

| *] (10th - 12th century) | |||

| |controlledby = ] | |||

| *] (12th - 13th century) | |||

| |garrison = | |||

| *]{{sfn|Paul E. Schellinger|Robert M. Salkin|1994|p=312}} (14th–16th century) | |||

| |current_commander = | |||

| *Captured by ] (1526) | |||

| |commanders = | |||

| *] (1540–1542) | |||

| |occupants = | |||

| *] (1542–1725) | |||

| |battles = | |||

| *] (1725-1735) (Mid 18th century) | |||

| |events = | |||

| *Briefly captured by ] (1735-1740) | |||

| |image2 = | |||

| *] (mid 18th century; 1740–1948) | |||

| |caption2 = | |||

| *Briefly captured by ] (1858–86) | |||

| *] (1948–present) | |||

| | garrison = | |||

| | current_commander = | |||

| | past_commanders = | |||

| | occupants = | |||

| | battles = Numerous | |||

| | events = Numerous | |||

| | image2_size = 200px | |||

| | Nickname = Gibraltar of India | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Fort of Gwalior''' or the '''Gwalior Fort''' is a defence ] in ], ]. ] ] called it the "pearl amongst the fortresses of ]" because of its impregnability and magnificence and it has also been nicknamed the ] of India.<ref>{{Cite web |date=19 March 2022 |title=Gibraltar of India |url=https://thelostcoordinates.com/2022/03/19/gibraltar-of-india/}}</ref> The history of the fort goes back to the 5th century or perhaps to a period still earlier. The old name of the hill as recorded in ancient Sanskrit inscriptions is Gopgiri.<ref name=":0">{{cite web |title=Gwalior Monument |url=https://asibhopal.nic.in/monument/gwalior.html |website=Archaeological Survey of India Bhopal}}</ref> The current structure of the fort has existed at least since the 8th century, and the inscriptions and monuments found within what is now the fort campus indicate that it may have existed as early as the beginning of the 6th century, making it one of India's oldest defence fort still in existence. The modern-day fort, embodying a defensive structure and two palaces was built by the ] ruler ] (reigned 1486–1516 CE).{{sfn|Paul E. Schellinger|Robert M. Salkin|1994|p=312}}<ref>{{Cite book|author=Romila Thapar|author-link=Romila Thapar|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HqmyEbLScZ4C&q=Rajput|title=The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300|date=2003|publisher=Penguin Books Limited|isbn=978-0-14-193742-7|page=179|quote=Other claiming to be Rajput and descent from Solar and lunar lines established themselves as local kings in Western and Central India. Among these were the Chandelas present in 12th century in Bundelkhand, the Tomaras also subject to the earlier Pratiharas ruling in Haryana region near Dhilaka, now Delhi, around 736 AD and later established themselves in Gwalior region}}</ref> It has witnessed the varying fortunes of the ], the ], the ], the ], the ], the ], the ], the ], the ], the ], and the ] represented by the powerful ] who have left their landmarks in the various monuments which are still preserved. | |||

| '''Gwalior Fort''' ({{lang-hi|ग्वालियर क़िला}} ''Gwalior Qila'') is an 8th-century ] near ], ], central ]. The fort consists of a defensive structure and two main palaces, Gurjari Mahal and Man Mandir, built by Man Singh Tomar. The fort has been controlled by a number of different rulers in its history. The Gurjari Mahal palace was built for Queen Mrignayani. It is now an archaeological museum. | |||

| The present-day fort consists of a defensive structure and two main palaces, "Man Mandir" and ], built by Man Singh Tomar, the latter one for his ] wife, Queen Mrignayani.{{sfn|Paul E. Schellinger|Robert M. Salkin|1994|p=312}} The second ] of ''"]"'' in the world was found in a small temple (the stone inscription has the second oldest record of the numeric zero symbol having a place value as in the modern decimal notation), which is located on the way to the top. The inscription is around 1500 years old.<ref name="smithsonianmag.com"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170916183250/http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/you-can-visit-the-worlds-oldest-zero-at-a-temple-in-india-2120286/?no-ist |date=16 September 2017 }}, Smithsonian magazine.</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Joseph |first1=George Gheverghese |title=Indian Mathematics: Engaging with the World from Ancient to Modern Times |publisher=World Scientific |date=2016 |isbn=978-1786340634 |quote=In a temple on the path up to Gwalior Fort where we find a circular zero in the terminal position. }} {{page needed|date=July 2020}}</ref> | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| As per the legends word ''Gwalior'' is derived from one of the names for ].<ref>Fodor E. et al. D. McKay 1971. p. 293. Accessed at Google Books 30 November 2013.]</ref> According to legend, Gwalipa cured the local chieftain Suraj Sen of leprosy, and in gratitude, Suraj Sen founded the city of Gwalior in his name.<ref></ref> Contrary to that the fort has been referred in Sanskrit inscriptions and in ] to as Gop Parvat(Gop Mountain), Gopachala Durg, Gopgiri, and Gopadiri, all which mean “cowherd’s hill.<ref>{{Cite web |date=15 October 2024 |title=Cowherd's Hill |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Gwalior-India |access-date=15 October 2024 |website=Britannica}}</ref> | |||

| ==Topography== | ==Topography== | ||

| <gallery widths="200px" heights="200px"> | |||

| ] | |||

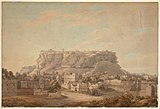

| Gwalior Fort seen from the Residency. 10 December 1868.jpg|Gwalior Fort seen from the Residency. 10 December 1868. | |||

| The fort is built on an outcrop of ] sandstone on a solitary rocky hill called Gopachal. This feature is long, thin, and steep. The ] of the Gwalior range rock formations is ] coloured ] covered with ]. There is a horizontal stratum, {{convert|342|ft|m}} at its highest point (length {{convert|1.5|mi|km}} and average width {{convert|1000|yard|m}}). The stratum forms a near-perpendicular precipice. A small river, the Swarnrekha, flows close to the palace.<ref>Oldham R. D. 1108072542, 9781108072540 Cambridge University Press 2011. p65 Accessed at Google Books 30 November 2013.</ref> | |||

| Gwalior Fort map 1911.jpg|Gwalior Fort map 1911 (click to see details) | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| The fort is built on an outcrop of ] sandstone on a solitary rocky hill called Gopachal. This feature is long, thin, and steep. The ] of the Gwalior range rock formations is ] coloured ] covered with ]. There is a horizontal stratum, {{convert|342|ft|m}} at its highest point (length {{convert|1.5|mi|km}} and average width {{convert|1000|yard|m}}). The stratum forms a near-perpendicular precipice. A small river, the Swarnrekha, flows close to the palace.<ref>Oldham R. D. {{ISBN|978-1108072540}} Cambridge University Press 2011. p. 65 Accessed at Google Books 30 November 2013.</ref> | |||

| == |

== History == | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| Legend tells that ] ], chieftain of the nearby Silhonia village was on a hunting trip. He came upon the hermit, Gwalipa (Galava) who gave the chieftain healing water from the Surajkund reservoir. In gratitude for the healing of ], the chieftain founded Gwalior, naming it after Gwalipa. The earliest record of the fort is 525 AD where it is mentioned in an inscription in the temple of the ]) emperor, ] (510 AD). Near the fort is an 875 AD Chaturbhuj temple associated with Telika Mandir.<ref>Mitra S. (Ed.) Goodearth publications 2009. p65. Accessed at Google Books, 30 November 2013.</ref> | |||

| The exact period of Gwalior Fort's construction is uncertain.{{sfn|Konstantin Nossov|Brain Delf|2006|p=11}} According to a local legend, the fort was built by a local king named ] in 600 CE.{{Dubious|date=May 2024}} He was cured of leprosy, when a sage named Gwalipa offered him the water from a sacred pond, which now lies within the fort. The grateful king constructed a fort and named it after the sage. The sage bestowed the title ''Pala'' ("protector") upon the king and told him that the fort would remain in his family's possession, as long as they bear this title. 16 descendants of Suraj Sen Pal controlled the fort, but the 17th, named Tej Karan, lost it.{{sfn|Paul E. Schellinger|Robert M. Salkin|1994|p=312}} | |||

| The inscriptions and monuments found within what is now the fort campus indicate that it may have existed as early as the beginning of the 6th century.{{sfn|Konstantin Nossov|Brain Delf|2006|p=11}} A ] describes a sun temple built during the reign of the ] emperor ] in 6th century. The ], now located within the fort, was built by the ]s in the 9th century.{{sfn|Paul E. Schellinger|Robert M. Salkin|1994|p=312}} | |||

| ===Pal dynasty of Kachawaha=== | |||

| The Pal dynasty of 86 kings ruled for 989 years. It began with Suraj Pal and concluded with Budha Pal. Budha Pal's son was Tej Karan (1127 - 1128). Gwalipa prophesied that the Pal dynasty would continue while the patronym, ''Pal'' was kept. Tej Keran married the daughter of Ran Mul, ruler of Amber (]) and received a valuable dowry. Tej Keran was offered the reign of Amber as long as he made it his residence. He did so, leaving Gwalior under Ram Deva Pratihar.<ref>Bhayasaheb B. R. (translator) Education Society's Steam Press, Byculla, 1892. University of Michigan. p432. Accessed at Google Books 30 November 2013.</ref> | |||

| The fort definitely existed by the 10th century, when it is first mentioned in the historical records. The ] controlled the fort at that time, most probably as feudatories of the ]s.{{sfn|Sisirkumar Mitra|1977|p=59}} From 11th century onwards, the Muslim dynasties attacked the fort several times. In 1022 CE, ] besieged the fort for four days. According to ''Tabaqat-i-Akbari'', he lifted the siege in return for a tribute of 35 elephants.{{sfn|Sisirkumar Mitra|1977|pp=80–82}} Bahauddin Tourghil, a senior slave of the ] ruler ] captured the fort in 1196 after a long siege.<ref>{{Cite book|author=Iqtidar Alam Khan|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=URluAAAAMAAJ |title=Historical Dictionary of Medieval India |date=2008|publisher=Scarecrow Press |isbn=978-0-8108-5503-8|page=33}}</ref> The ] lost the fort for a short period before it was recaptured by ] in 1232 CE.{{sfn|Paul E. Schellinger|Robert M. Salkin|1994|p=312}} | |||

| ===Gurjara-Pratihara Dynasty=== | |||

| The ] dynasty at Gwalior included Pramal Dev, Salam Dev, Bikram Dev, Ratan Dev, Shobhang Dev, Narsinh Dev and Pramal Dev.<ref>Bakshi S. R. Sarup & Sons, 2005. p321 ISBN 8176255378, 9788176255370. Accessed at Google Books 30 November 2013.</ref> | |||

| In 1398, the fort came under the control of the ]. The most distinguished of the Tomar rulers was ], who commissioned several monuments within the fort.{{sfn|Paul E. Schellinger|Robert M. Salkin|1994|p=312}} The ] tried to capture the fort in 1505 but was unsuccessful. Another attack, by his son ] in 1516, resulted in Maan Singh's death. The Tomars ultimately surrendered the fort to the ] after a year-long siege.{{sfn|Paul E. Schellinger|Robert M. Salkin|1994|p=314}} | |||

| ===Turkic conquest=== | |||

| In 1023 AD, ] unsuccessfully attacked the fort. In 1196 AD, after a long siege, ], first ] sultan of ] took the fort, ruling till 1211 AD. In 1231 AD, the fort taken by ], Turkic sultan of Delhi. Under attack from ], Narasingh Rao, a Jaina chieftain captured the fort. | |||

| ]'s campaigns.]] | |||

| ===Tomar rulers=== | |||

| Within a decade, the ] ] captured the fort from the ]. The ] lost the fort to ] in 1542. Afterwards, the fort was captured and used by ], the ] general and, later, the last Hindu ruler of ], as his base for his many campaigns, but Babur's grandson ] recaptured it in 1558.{{sfn|Paul E. Schellinger|Robert M. Salkin|1994|p=314}} Akbar made the fort a prison for political prisoners. For example, Abu'l-Kasim,<ref name="Thorton" /> son of ] and Akbar's first cousin was held and executed at the fort. The last Tomar king of Gwalior, ], who had then taken refuge in ] and had fought at the ]. He was killed in the battle along with his three sons (which included ], the heir-apparent) | |||

| The Rajput ] ruled Gwalior from 1398 (when Pramal Dev captured the fort from a ] ruler) to 1518 (when Vikramaditya was defeated by Ibrahim Lodhi).{{citation needed|date=November 2014}} | |||

| ] from the 1910s.]] | |||

| {{Div col|3}} | |||

| * Pramal Dev (Ver Singh, Bir Sing Deo) 1375. | |||

| * Uddhharan Dev (brother of Pramal Dev). | |||

| * Lakshman Dev Tomar | |||

| * Viramdev 1400 (son of Virsingh Dev). | |||

| * Ganapati Dev Tomar 1419. | |||

| * Dugarendra (Dungar) Singh 1424. | |||

| * Kirti Singh Tomar 1454. | |||

| * Mangal Dev (younger son of Kirti Singh). | |||

| * Kalyanmalla Tomar 1479. | |||

| * ] 1486 - 1516 (builder of the Man mandir). | |||

| * Vikramaditya Tomar 1516. | |||

| * Ramshah Tomar 1526. | |||

| * Salivahan Tomar 1576. | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

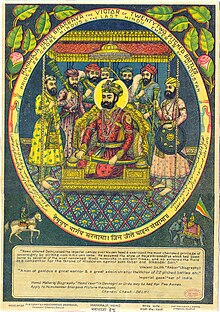

| ], on 24 June 1606, at age 11, was crowned as the sixth Sikh Guru.<ref>Louis E. Fenech, Martyrdom in the Sikh Tradition, Oxford University Press, pages 118–121</ref><ref name=hssingha>HS Singha (2009), Sikh Studies, Book 7, Hemkunt Press, {{ISBN|978-8170102458}}, pages 18–19</ref> At his succession ceremony, he put on two swords: one indicated his spiritual authority (''piri'') and the other, his temporal authority (''miri'').<ref name=hssyan>HS Syan (2013), Sikh Militancy in the Seventeenth Century, IB Tauris, {{ISBN|978-1780762500}}, pages 48–55</ref> Because of the execution of ] by Mughal Emperor Jahangir, Guru Hargobind from the very start was a dedicated enemy of the Mughal rule. He advised the ] to arm themselves and fight.<ref name=mah>{{cite book |title=Muslim Rule in India |author=V. D. Mahajan |year=1970 |publisher=S. Chand, New Delhi, p.223}}</ref> The death of his father at the hands of ] prompted him to emphasise the military dimension of the ] community.<ref name="Phyllis2004">{{cite book |title=Holy People of the World: A Cross-cultural Encyclopedia, Volume 1 |author=Phyllis G. Jestice |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=H5cQH17-HnMC&pg=PA345|publisher=] |year=2004 |isbn=9781576073551 |pages=345, 346}}</ref> ] responded by jailing the 14-year-old Guru Hargobind at Gwalior Fort in 1609, on the pretext that the fine imposed on ] had not been paid by the ] and ].<ref name=mandair48>{{cite book|title=Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed|author= Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BEP0Ty-GuVEC&pg=PA48 |publisher=] |year=2013|isbn=9781441117083|page=48}}</ref> It is not clear as to how much time he spent as a prisoner. The year of his release appears to have been either 1611 or 1612, when Guru Hargobind was about 16 years old.<ref name=mandair48/> Persian records, such as ''Dabistan i Mazahib'' suggest he was kept in jail for twelve years, including over 1617–1619 in Gwalior, after which he and his camp were kept under Muslim army's surveillance by Jahangir.<ref name=eos>{{cite book |author=Fauja Singh |editor=Harbans Singh |title=Encyclopaedia of Sikhism |volume=2, E–L |edition=3rd |chapter=Hargobind Guru (1595–1644) |year=2011 |publisher=Punjabi University |location=Patiala |pages=232–235 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/TheEncyclopediaOfSikhism-VolumeIiE-l/page/n245x |isbn=978-8173802041 |via=Internet Archive}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=The Sikh Review |volume=42–43 |issue=491–497 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1XPXAAAAMAAJ |year=1994 |publisher=Sikh Cultural Centre |pages=15–16}}</ref> According to Sikh tradition, Guru Hargobind was released from the bondage of prison on ]. This important event in Sikh history is now termed the '']'' festival.<ref>{{cite book |author=Eleanor Nesbitt |title=Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XebnCwAAQBAJ |year=2016 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-874557-0 |pages=28–29, 59, 120–131}}</ref> | |||

| ===Suri dynasty=== | |||

| In 1519, ] took the fort. After his death, control passed to the ] emperor ]. Babur's son, ], was defeated by ]. After Suri's death in 1540, his son, Islam Shah, moved power from Delhi to Gwalior for strategic reasons. After the death of Islam Shah in 1553, his incumbent, Adil Shah Suri, appointed the Hindu warrior, Hemu, as manager of Gwalior. From 1553 - 1556, Hemu attacked Adil Shah Suri and others from the fort. | |||

| ]'s brother, ] and nephew ] were also executed at the fort. The killings took place in the Man Mandir palace. ] was imprisoned at Gwalior Fort from 1659 to 1675. Aurangzeb's son, ] was imprisoned at the fort from January 1661 to December 1672. After the death of Aurangzeb, the ] ruler of ], ] seized the Gwalior Fort in the ]. The ] had captured many territories held by the declining ] in ] and ] India after the death of Aurangzeb. The Maratha incursions into North India were raids by the ]. in 1755–1756, The ] took over Gwalior fort by defeating the Jat ruler of Gohad.<ref name="Thorton">Torton E. W. H. Allen & Co. 1854.</ref>{{rp|page=68}} The ] general ] (]) captured the fort from the Gohad Rana Chhatar Singh, but later lost it to the British ].{{sfn|Tony McClenaghan|1996|p=131}} On 3 August 1780, a Company force under Captains Popham and Bruce captured the fort in a nighttime raid, scaling the walls with 12 ]s and 30 ]s. Both sides suffered fewer than 20 wounded total.<ref name="Thorton"/>{{rp|page=69}} In 1780, the ] ] restored the fort to the Ranas of Gohad. The Marathas recaptured the fort four years later, and this time the British did not intervene because the Ranas of Gohad had become hostile to them. ] lost the fort to the British during the ].{{sfn|Tony McClenaghan|1996|p=131}} | |||

| ===Mughal dynasty=== | |||

| ] | |||

| When the Mughal leader, ] captured the fort, he made it a prison for political prisoners. For example, ], Akbar's cousin was held and executed at the fort. Aurangzeb's brother, ] and nephews Suleman and Sepher Shikoh were also executed at the fort. The killings took place in the Man Madir palace.<ref name="Thorton">Torton E. W. H. Allen & Co. 1854.</ref>{{rp|page=68}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Rana Rajput dynasty=== | |||

| ] leaving the fort from the Hathi Pol. Painting by Edward Lord Weeks.]] | |||

| The Raizada Rajputs of ] occupied the fort on three occasions between 1740 and 1783.<ref name="Singh">Singh N. "Jat-Itihas." 2004.</ref>{{rp|page=360}}<ref name="Singh"/>{{rp|page=359}}<ref>Tyagi V. P. Gyan Publishing House, 2009 | |||

| ISBN 8178357755, 9788178357751. p75. Accessed at Google Books 1 December 2013.</ref><ref>Malleson G. B. "An Historical Sketch of the Native States of India." The Academic Press, Gurgaon, 1984 (reprint).</ref><ref>Krishnan V. N. "Madhya Pradesh District Gazetteer." Gwalior.</ref><ref>Agnihotri A. K. "Gohad ke jaton ka Itihas." Nav Sahitya Bhawan. New Delhi, Delhi. 1985. p. 29.</ref> | |||

| (] 1740 - 1756; ] 1761 - 1767; and ] 1780 - 1783). | |||

| There were frequent changes in the control of the fort between the ] and the ] between 1808 and 1844. In January 1844, after the ], the fort was occupied by the ] of the ] ] family, as a protectorate of the ].<ref name="Thorton"/>{{rp|page=69}} During the ], around 6500 sepoys stationed at Gwalior rebelled against the Company rule, although the company's vassal ruler ] remained loyal to the British.{{sfn|Paul E. Schellinger|Robert M. Salkin|1994|p=314}} The British took control of the fort in June 1858. They rewarded Jayajirao with some territory but retained control of the Gwalior Fort. By 1886, the British were in complete control of ], and the fort no longer had any strategic importance to them. Therefore, they handed over the fort to the ]. The ] ] continued to rule Gwalior until the ] in 1947 and built several monuments including the ].{{sfn|Paul E. Schellinger|Robert M. Salkin|1994|p=316}}<ref>Archived at {{cbignore}} and the {{cbignore}}: {{cite web |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9UHaBw1EDrk |title=History of Gwalior {{!}} ग्वालियर का इतिहास |date=27 January 2019 |via=]}}{{cbignore}}</ref> | |||

| ===Maratha rule=== | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1779, the ] clan of the ] stationed a garrison at the fort. The fort was contested in the ]. On August 3, 1780, the ] under Captains Popham and Bruce captured the fort in a daring nighttime raid, scaling the walls with 12 grenadiers and 30 ]s. Both sides suffered fewer than 20 wounded total.<ref name="India Gazette"/>{{rp|page=1781-01-06 pg1}} In 1784, the Marathas under Mahadji Sinde, recovered the fort. There were frequent changes in the control of the fort between the Scindias and the British between 1808 and 1844. In January 1844, after the battle of ], the fort was occupied by the Marathas as protectorate of the ].<ref name="Thorton"/>{{rp|page=69}} | |||

| ===Rebellion of 1857=== | |||

| On 1 June 1858, ] led a rebellion. The Central India Field Force, under General Hugh Rose, besieged the fort. Bai died on 18 June 1858. | |||

| ==Structures== | ==Structures== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The fort and its premises are well maintained and house many historic monuments including palaces, temples and water tanks |

The fort and its premises are well maintained and house many historic monuments including palaces, temples and water tanks. There are also a number of palaces (''mahal'') including the Man mandir palace, the Gujari mahal, the ] palace, the Karan palace, the Vikram mahal and the ] palace.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090420011046/http://www.kamat.com/kalranga/mp/gwalior.htm |date=20 April 2009 }} Kamat's Potpourri Webpage. Accessed 1 December 2013.</ref> | ||

| The fort covers an area of {{convert|3|km2|mi2}} and rises {{convert| |

The fort covers an area of {{convert|3|km2|mi2}} and rises {{convert|11|m|ft}}. Its rampart is built around the edge of the hill, connected by six ] or towers. The profile of the fort has an irregular appearance due to the undulating ground beneath.{{citation needed|date=March 2017}} | ||

| There are two gates |

There are two gates: one on the northeast side with a long access ramp and the other on the southwest. The main entrance is the ornate Elephant gate (''Hathi Pol''). The other is the Badalgarh Gate. The Man Mandir palace or citadel is located at the northeast end of the fort. It was built in the 15th century and refurbished in 1648. The water tanks or reservoirs of the fort could provide water to a 15,000 strong garrison, the number required to secure the fort.{{citation needed|date=March 2017}} | ||

| The second ] of ''"]"'' in the world was found in a small temple (the stone inscription has the second oldest record of the numeric zero symbol having a place value as in the modern decimal notation), which is located on the way to the top. The inscription is around 1500 years old.<ref name="smithsonianmag.com"/><ref>{{cite book |last1=Joseph |first1=George Gheverghese |title=Indian Mathematics: Engaging with the World from Ancient to Modern Times |publisher=World Scientific |date=2016 |isbn=978-1786340634 |quote=In a temple on the path up to Gwalior Fort where we find a circular zero in the terminal position. }} {{page needed|date=July 2020}}</ref> | |||

| ===Man mandir palace=== | |||

| The Man mandir palace was built by the King of Tomar Dynasty - Maharaja Man Singh. | |||

| === |

===Major Monuments=== | ||

| ==== Jain temples ==== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Main|Siddhachal Caves|Gopachal rock cut Jain monuments}} | |||

| ] | |||

| '''Siddhachal Jain Rock Cut Caves''' were built in 15th century. There are eleven Jain temples inside Gwalior fort dedicated to the Jain ]s. On the southern side are 21 temples cut into the rock with intricately carved of the tirthankaras. Tallest Idol is image of Rishabhanatha or Adinatha, the 1st Tirthankara, is {{convert|58|ft|4|in|m}} high.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Kurt Titze |author2=Klaus Bruhn |title=Jainism: A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-violence |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=loQkEIf8z5wC |year=1998 |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass |isbn=978-81-208-1534-6|pages=106–110}}</ref><ref name=cunninghamgfortjain>{{cite book |last=Cunningham |first=Alexander |title=Archaeological Survey of India: Four Reports Made During the Year 1862–63–64-65 |volume=2 |chapter=XVI. Gwaliar, or Gwalior (Gwalior Fort: Rock Sculptures) |pages=364–370 |publisher=Government Central Press |location=Simla |date=1871 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/stream/archaeologicalsu02arch#page/n455/mode/2up |via=Internet Archive}}</ref><ref name=asifortjain>{{cite web |title=Gwalior Fort, Gwalior |website=Archaeological Survey of India, Bhopal Circle |url=http://asibhopal.nic.in/monument/gwalior_gwalior_gwaliorfort_more.html |publisher=Government of India, Ministry of Culture |date=2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190515153007/http://www.asibhopal.nic.in/monument/gwalior_gwalior_gwaliorfort_more.html |archive-date=15 May 2019}}</ref> | |||

| The Hathi Pol gate (or Hathiya Paur), located on the southeast, leads to the Man mandir palace. It is the last of a series of seven gates. It is named for a life-sized statue of an elephant (hathi) that once adorned the gate. The gate was built in stone with cylindrical towers crowned with ] domes. Carved parapets link the domes. | |||

| '''Main Temple''' | |||

| ===Gujari Mahal museum=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Gujari Mahal was built by Raja Man Singh for his wife Mrignayani, a Gujar princess. She demanded a separate palace for herself with a regular water supply through an aqueduct from the nearby Rai River. The palace has been converted into an ]. Rare artefacts at the museum include Hindu and Jain sculptures dated to the 1st and 2nd centuries BC; miniature statue of ]; ] items and replicas of ] seen in the ]. | |||

| '''Urvahi''' | |||

| ===Teli ka mandir=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The Teli-ka mandir (the oilman’s temple or oil pressers' temple) is a ] sanctuary built in the 8th (or perhaps the 11th century) and was refurbished between 1881 and 1883. It is the oldest part of the fort and has a blend of south and north Indian architectural styles. Within the rectangular structure is a shrine with no pillared pavilions (]) and a Buddhist barrel-vaulted roof on a Hindu mandir. Buddhist architectural elements are found in the ] type hall and ] decorations at the entrance. There is a ] tower in the ] architectural style with a ]ed roof {{convert|25|m|ft}} in height. The niches in the outer walls once housed statues but now have ] (horse shoe arch) ventilator openings in the north Indian style. The gavaksha has been compared to the ], a honeycomb design with a series of receding pointed arches within an arch. The entrance door has a ] or archway with sculpted images of river goddesses, romantic couples, foliation decoration and a ]. Diamond and lotus designs are seen on the horizontal band at the top of the arch indicating an influence from the ] period. The vertical bands on either side of the door are decorated in a simple fashion with figures that are now badly damaged. Above the door are a small grouping of discs representing the ] (]) of an Indo-Aryan Shikhara. The temple was originally dedicated to ], but later converted to the worship of ].<ref>Allen M. P. University of Delaware Press 1991. ISBN 0-87413-399-8.</ref> | |||

| The entire area of Gwalior fort is divided into five groups namely Urvahi, Northwest, Northeast, Southwest and the Southeast areas. In the Urvahi area 24 idols of Tirthankar in the ] posture, 40 in the ] posture and around 840 idols carved on the walls and pillars are present. The largest idol is a 58 feet 4 inches high idol of ] outside the Urvahi gate and a 35 feet high idol of ] in the Padmasana in ''Ek'' ''Paththar-ki Bawari'' (stone tank) area.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.jainsamaj.org/rpg_site/literature2.php?id=2447&cat=40 |title=Jain Samaj |access-date=16 May 2016 |archive-date=4 June 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160604130802/http://www.jainsamaj.org/rpg_site/literature2.php?id=2447&cat=40 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| '''Gopachal''' | |||

| ===Garuda monument=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Close to the Teli ka Mandir temple is the ] monument, dedicated to ], is the highest in the fort. It has a mixture of ] and ]. The word ''Teli'' comes from the Hindu word ''Taali'' a bell used in worship. | |||

| There are around 1500 idols on the ], which includes the size from 6 inch to 57 feet in height. All the idols are carved by cutting the hilly rocks (rock carving) and are very artistic. Most of the idols were built in 1341–1479, during the period of King Dungar Singh and Keerti Singh of ].<ref name=cunninghamgfortjain/> | |||

| Here is a very beautiful and miraculous{{weasel inline|date=March 2017}} colossus of Bhagwan Parsvanath in padmasan posture 42 feet in height & 30 feet in breadth. It is said that in 1527, Mughal emperor Babar after occupying the fort ordered his soldiers to break the idols, when soldiers stroked on the thumb, a miracle was seen, and invaders were compelled to run away. In the period of Mughals, the idols were destroyed, broken fragments of those idols are spread here and there in the fort.<ref name=cunninghamgfortjain/> | |||

| ===Saas-bahu temple=== | |||

| In 1093, the Pal Kachawaha rulers built two temples to Vishnu. The temples are pyramidal in shape, built of red sandstone with several stories of beams and pillars but no arches. | |||

| Main colossus of this Kshetra is Parsvanatha's, 42 feet high and 30 feet wide. Together with the place of precept by Bhagwan Parsvanath. This is also the place where ''Shri 1008 Supratishtha Kevali'' attained nirvana. There are 26 Jain temples more on this hill.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://jain.org.in/tirth-Gopachal%20hill,%20M.P.html |title=jain.org.in |access-date=16 May 2016 |archive-date=21 April 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160421152014/http://jain.org.in/tirth-Gopachal%20hill,%20M.P.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Karn mahal=== | |||

| The Karn mahal is another significant monument at Gwalior Fort. The Karn mahal was built by the second king of the Tomar dynasty, Kirti Singh. He was also known as Karn Singh, hence the name of the palace. | |||

| '''Mughal Invasion:''' In 1527, ] army attacked Gwalior Fort and de-faced these statues.<ref name=cunninghamgfortjain/> In spite of invasion the early Jaina sculptures of Gwalior have survived in fairly good condition so that their former splendour is not lost. | |||

| ===Vikram mahal=== | |||

| The Vikram mahal (also known as the Vikram mandir, as it once hosted a ] of ]) was built by Vikramaditya Singh, the elder son of ] Mansingh.He was a devotee of Shiva. The ] was destroyed during ] period but now has been re-established in the front open space of the Vikram mahal. | |||

| === |

====Teli Temple==== | ||

| {{main|Teli ka Mandir}} | |||

| This ] (cupola or domed shaped pavilion) was built as a memorial to Bhim Singh Rana (1707-1756), a ruler of ] state. It was built by his successor, Chhatra Singh. Bhim Singh occupied Gwalior fort in 1740 when the ] ], Ali Khan, surrendered. In 1754, Bhim Singh built a bhimtal (a lake) as a monument at the fort. Chhatra Singh built the memorial chhatri near the bhimtal. Every year, the ] Samaj Kalyan council (parishad) of Gwalior organises a fair on ], in honor of Bhim Singh Rana. | |||

| ] was built by the Pratihara emperor ].<ref name="Bajpai2006">{{cite book|author=K. D. Bajpai|title=History of Gopāchala|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Q3KcwLKuRnYC&pg=PA31|year=2006|publisher=Bharatiya Jnanpith|isbn=978-81-263-1155-2|page=31}}</ref>]] | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] is a Hindu temple built by the Pratihara emperor ].<ref name="Michell1977p117">{{cite book |author=George Michell |title=The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to Its Meaning and Forms |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ajgImLs62gwC&pg=PA117 |year=1977 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0-226-53230-1 |pages=117 with footnotes}}</ref><ref name="Allen1991">{{cite book |author=Margaret Prosser Allen |title=Ornament in Indian Architecture |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vyXxEX5PQH8C&pg=RA1-PA203 |year=1991 |publisher=University of Delaware Press |isbn=978-0-87413-399-8 |page=1}}</ref> | |||

| It is the oldest part of the fort and has a blend of south and north ]. Within the rectangular structure is a shrine with no pillared pavilions (]) and a South Indian barrel-vaulted roof on top. It has a ] tower in the North Indian ] with a ]ed roof {{convert|25|m|ft}} in height. The niches in the outer walls once housed statues but now have ]s (horseshoe arches) ventilator openings in the north Indian style. The Chandrashala has been compared to the ], a honeycomb design with a series of receding pointed arches within an arch. The entrance door has a torana or archway with sculpted images of river goddesses, romantic couples, foliation decoration and a ]. The vertical bands on either side of the door are decorated in a simple fashion with figures that are now badly damaged. Above the door are a small grouping of discs representing the {{lang|und|dama laka}} (]) of a {{lang|sa|]}}. The temple was originally dedicated to ]. It was extensively damaged during Muslim raids, then restored into a ] temple by installing a ], while keeping the Vaishnava motifs such as the Garuda.<ref>Allen M. P. University of Delaware Press 1991. {{ISBN|0-87413-399-8}}.</ref><ref>, A Cunningham, pp. 356–359</ref> It was refurbished between 1881 and 1883.<ref>{{cite book |editor1-last=Sengupta |editor1-first=Guatam |editor2-last=Lambah |editor2-first=Abha Narain |editor2-link=Abha Narain Lambah |title=Custodians of the past: 150 years of the Archaeological Survey of India |date=2012 |publisher=], Ministry of Culture, Government of India |isbn=978-93-5086-199-8 |page=32 |url=https://archive.org/details/custodiansofpast00newd/page/32/mode/1up?q=keith&view=theater}}</ref><ref>{{cite report |author2=(Curator of Ancient Monuments, India) |author1=Henry Hardy Cole |title=Preservation of National Monuments: Report of the Curator of Ancient Monuments in India |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gnEIAAAAQAAJ&pg=PR17 |year=1882 |publisher=Government Central Branch Press |location=Simla |page=17}}</ref> | |||

| ====Garuda monument==== | |||

| Close to the Teli ka Mandir temple is the ] monument, dedicated to ], is the highest in the fort. It has a mixture of ] and ]. The word Teli comes from the Hindi word meaning oil.{{citation needed|date=April 2021}} | |||

| ====Saas Bahu temples==== | |||

| The Saas Bahu Temples were built in 1092–93 by the ] dynasty.<ref name="TitzeBruhn1998p101">{{cite book |author1=Kurt Titze|author2=Klaus Bruhn |title=Jainism: A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-violence |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=loQkEIf8z5wC&pg=PA101 |year=1998 |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass |isbn=978-81-208-1534-6 |pages=101–102}}</ref><ref name="Allen1991p211">{{cite book |author=Margaret Prosser Allen |title=Ornament in Indian Architecture |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vyXxEX5PQH8C |year=1991 |publisher=University of Delaware Press|isbn=978-0-87413-399-8 |pages=211–212}}</ref> Dedicated to ] and Shiva, These are pyramidal in shape, built of red sandstone with several stories of beams and pillars but no arches. | |||

| ====Gurdwara Data Bandi Chhor==== | |||

| Gurdwara Data Bandi Chhor was built during 1970s and 1980s at the place where 6th ] ] Sahib was arrested and held captive by Mughal Emperor ] in 1609 at the age of 14 years on the pretext that the fine imposed on his father, 5th Sikh ] had not been paid by the Sikhs and Guru Hargobind. According to Surjit Singh Gandhi, 52 ] Rajas who were imprisoned in the fort as hostages for "millions of rupees" and for opposing the ] were dismayed as they were losing a spiritual mentor. On getting released Guru Hargobind requested the Rajas to be freed along with him as well. Jahangir allowed Guru Hargobind to free as many rajas he could as long as they are holding on to the guru while leaving the prison. Guru sahib got a special gown stitched which had 52 hems. As Guru Hargobind left the fort, all the captive kings caught the hems of the cloak and came out along with him.{{citation needed|date=April 2021}} | |||

| ===Palace=== | |||

| ====Man mandir palace==== | |||

| The Man mandir palace was built by the King of Tomar Dynasty – Maharaja Man Singh in 15th century. Man Mandir is often referred as a Painted Palace because the painted effect of the Man Mandir Palace is due to the use of styled tiles of turquoise, green and yellow used extensively in a geometric pattern.{{citation needed|date=March 2017}} | |||

| ====Hathi Pol==== | |||

| The Hathi Pol gate (or Hathiya Paur), located on the southeast, leads to the Man mandir palace. It is the last of a series of seven gates. It is named for a life-sized statue of an elephant (hathi) that once adorned the gate.{{citation needed|date=March 2017}} The gate was built in stone with cylindrical towers crowned with ] domes. Carved parapets link the domes. | |||

| ====Karn mahal==== | |||

| The Karan mahal is another significant monument at Gwalior Fort. The Karn mahal was built by the second king of the Tomar dynasty, Kirti Singh. He was also known as Karn Singh, hence the name of the palace.{{citation needed|date=March 2017}} | |||

| ====Vikram mahal==== | |||

| The Vikram mahal (also known as the Vikram mandir, as it once hosted a temple of ]) was built by Vikramaditya Singh, the elder son of ] Mansingh. He was a devotee of shiva.{{citation needed|date=March 2017}} The temple was destroyed during ] period but now has been re-established in the front open space of the Vikram mahal. | |||

| ====Chhatri of Bhim Singh Rana==== | |||

| This ] (cupola or domed shaped pavilion) was built as a memorial to ] (1707–1756), a ruler of ] state. It was built by his successor, Chhatra Singh. Bhim Singh ] when the Mughal ], Ali Khan, surrendered. In 1754, Bhim Singh built a bhimtal (a lake) as a monument at the fort. Chhatra Singh built the memorial chhatri near the bhimtal.{{citation needed|date=March 2017}} | |||

| ===Museum=== | |||

| {{main|Gujari Mahal Archaeological Museum}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The '''Gujari Mahal''' now a museum, was built by Raja ] for his wife Mrignayani, a Gujar princess. She demanded a separate palace for herself with a regular water supply through an aqueduct from the nearby Rai River.{{citation needed|date=March 2017}} The palace has been converted into an ]. Rare artefacts at the museum include Hindu and Jain sculptures dated to the 1st and 2nd centuries BC; miniature statue of ]; ] items and replicas of ] seen in the ]. | |||

| ===Other monuments=== | ===Other monuments=== | ||

| There are several other monuments built inside the fort area. These include the ] (an exclusive school for the sons of Indian princes and nobles)that was founded by ] in 1897 |

There are several other monuments built inside the fort area. These include the ] (Originally an exclusive school for the sons of Indian princes and nobles) that was founded by ] in 1897. | ||

| ==Gallery== | ==Gallery== | ||

| <gallery widths=160px heights=190px |

<gallery widths="160px" heights="190px"> | ||

| Interior_of_Jain_Temple,_Gwalior_Fort.jpg|Interior of Jain Temple, Gwalior Fort | |||

| File:Gwalior-estany1.jpg|Water reservoir. | |||

| File: |

File:Pond of gwalior fort.jpg|Pond at Gwalior Fort. | ||

| File:View of Gwalior Fort from the north-west.jpg|View of Gwalior Fort from the north-west. {{circa|1790}} | |||

| File:Gwalior fort panorama.jpg|Panoramic view. | |||

| File:254 Gwalior.jpg|Fortress wall. | |||

| File:Gwalior-porta.jpg|One of the seven entry gates. | |||

| File:246 Gwalior.jpg|The fort bastions. | File:246 Gwalior.jpg|The fort bastions. | ||

| File:Interior of North Room, Man Mandir, Gwalior Fort..jpg|The north room, Man Mandir. | File:Interior of North Room, Man Mandir, Gwalior Fort..jpg|The north room, Man Mandir. | ||

| File: |

File:Sas-Bahu temple, Gwalior Fort..jpg|]. | ||

| File: |

File:Gate of Teki Mandir, Gwalior Fort.jpg|Gate of Teli ka Mandir. | ||

| File:Gwalior Fort - Morning View.jpg|Gwalior Fort – Morning View | |||

| File:Gujari Mahal.JPG|Gujari Mahal. | |||

| File:Gwalior |

File:Gwalior fort6.jpg|Gwalior fort | ||

| File:Gurudwara Shri Data Bandi Chhor Shahib Gwalior 001 (2).jpg|Gurudwara Shri Data Bandi Chhor Shahib | |||

| File:ChhatriranaBhimSingh.jpg|] near Bhimtal in memory of ] | |||

| File:Sas-Bahu temple, Gwalior Fort..jpg|Sas-Bahu temple. | |||

| File:Small Sas Bahu temple, Gwalior Fort..jpg|Small temple. | |||

| File:Sculptures near Teli Mandir, Gwalior Fort.jpg|Sculptures. | |||

| File:Gate of Teki Mandir, Gwalior Fort.jpg|Gate of Teki Mandir. | |||

| File:Gwalior-Teli-ka-Mandir.jpg|Teli-ka-Mandir. | |||

| File:Mythological statue guarding Gujari Mahal.JPG|Mythological statue. | |||

| </gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{reflist |

{{reflist}} | ||

| === Bibliography === | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * {{cite book |author1=Konstantin Nossov |author2=Brain Delf |title=Indian Castles 1206–1526 |publisher=Osprey |year=2006 |edition=Illustrated |isbn=1-84603-065-X |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uXfocnQdZIAC }} | |||

| * Tillotson G. H. R. "The Rajput Palaces – The Development of an Architectural Style" Yale University Press. New Haven and London 1987. First edition. Hardback. ISBN0-300-03738-4 | |||

| * {{cite book |editor1=Paul E. Schellinger |editor2=Robert M. Salkin |title=International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania |volume=5 |publisher=Routledge/Taylor & Francis |year=1994 |isbn=978-1884964046 }} | |||

| * {{cite book |author=Sisirkumar Mitra |title=The Early Rulers of Khajurāho |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=irHN2UA_Z7gC&pg=PA59 |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass |year=1977 |isbn=978-8120819979 }} | |||

| * {{cite book |author=Tony McClenaghan |title=Indian Princely Medals |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YQdZlHJ2WTAC&pg=PA131 |publisher=Lancer |year=1996 |isbn=978-1897829196 }} | |||

| * Tillotson G. H. R. "The Rajput Palaces – The Development of an Architectural Style" Yale University Press. New Haven and London 1987. First edition. Hardback. {{ISBN|0-300-03738-4}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{commons category}} | {{commons category}} | ||

| * | |||

| * {{Wikivoyage-inline}} | |||

| * {{Wikivoyage inline}} | |||

| {{Gwalior topics}} | |||

| {{Forts in India}} | {{Forts in India}} | ||

| {{Forts in Madhya Pradesh}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 14:32, 23 November 2024

Fort in Madhya Pradesh, India| This article's factual accuracy is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help to ensure that disputed statements are reliably sourced. (May 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Fort of Gwalior | |

|---|---|

| Madhya Pradesh, India | |

The "Man Mandir" palace built by Tomar Rajput ruler Man Singh Tomar (reigned 1486–1516 CE), at Gwalior Fort The "Man Mandir" palace built by Tomar Rajput ruler Man Singh Tomar (reigned 1486–1516 CE), at Gwalior Fort | |

| |

| Coordinates | 26°13′49″N 78°10′08″E / 26.2303°N 78.1689°E / 26.2303; 78.1689 |

| Type | Fort |

| Site information | |

| Owner |

|

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Site history | |

| Built | 6th century, The modern-day fort, consisting a defensive structure and two palaces was built by King Man Singh Tomar, later renovated by Scindias under the Supervision of General Sardar Surve in 1916 |

| In use | Yes |

| Materials | Sandstone and lime mortar |

| Battles/wars | Numerous |

| Events | Numerous |

The Fort of Gwalior or the Gwalior Fort is a defence hill fort in Gwalior, India. Mughal Emperor Babur called it the "pearl amongst the fortresses of Hind" because of its impregnability and magnificence and it has also been nicknamed the Gibraltar of India. The history of the fort goes back to the 5th century or perhaps to a period still earlier. The old name of the hill as recorded in ancient Sanskrit inscriptions is Gopgiri. The current structure of the fort has existed at least since the 8th century, and the inscriptions and monuments found within what is now the fort campus indicate that it may have existed as early as the beginning of the 6th century, making it one of India's oldest defence fort still in existence. The modern-day fort, embodying a defensive structure and two palaces was built by the Tomar Rajput ruler Man Singh Tomar (reigned 1486–1516 CE). It has witnessed the varying fortunes of the Guptas, the Hunas, the Pratiharas, the Kachhwahas, the Tomaras, the Pathans, the Surs, the Mughals, the English, the Jats, and the Marathas represented by the powerful Scindia dynasty who have left their landmarks in the various monuments which are still preserved.

The present-day fort consists of a defensive structure and two main palaces, "Man Mandir" and Gujari Mahal, built by Man Singh Tomar, the latter one for his Gurjar wife, Queen Mrignayani. The second oldest record of "zero" in the world was found in a small temple (the stone inscription has the second oldest record of the numeric zero symbol having a place value as in the modern decimal notation), which is located on the way to the top. The inscription is around 1500 years old.

Etymology

As per the legends word Gwalior is derived from one of the names for Gwalipa. According to legend, Gwalipa cured the local chieftain Suraj Sen of leprosy, and in gratitude, Suraj Sen founded the city of Gwalior in his name. Contrary to that the fort has been referred in Sanskrit inscriptions and in Gupta period to as Gop Parvat(Gop Mountain), Gopachala Durg, Gopgiri, and Gopadiri, all which mean “cowherd’s hill.

Topography

-

Gwalior Fort seen from the Residency. 10 December 1868.

Gwalior Fort seen from the Residency. 10 December 1868.

-

Gwalior Fort map 1911 (click to see details)

Gwalior Fort map 1911 (click to see details)

The fort is built on an outcrop of Vindhyan sandstone on a solitary rocky hill called Gopachal. This feature is long, thin, and steep. The geology of the Gwalior range rock formations is ochre coloured sandstone covered with basalt. There is a horizontal stratum, 342 feet (104 m) at its highest point (length 1.5 miles (2.4 km) and average width 1,000 yards (910 m)). The stratum forms a near-perpendicular precipice. A small river, the Swarnrekha, flows close to the palace.

History

The exact period of Gwalior Fort's construction is uncertain. According to a local legend, the fort was built by a local king named Suraj Sen in 600 CE. He was cured of leprosy, when a sage named Gwalipa offered him the water from a sacred pond, which now lies within the fort. The grateful king constructed a fort and named it after the sage. The sage bestowed the title Pala ("protector") upon the king and told him that the fort would remain in his family's possession, as long as they bear this title. 16 descendants of Suraj Sen Pal controlled the fort, but the 17th, named Tej Karan, lost it.

The inscriptions and monuments found within what is now the fort campus indicate that it may have existed as early as the beginning of the 6th century. A Gwalior inscription describes a sun temple built during the reign of the Huna emperor Mihirakula in 6th century. The Teli ka Mandir, now located within the fort, was built by the Gurjara-Pratiharas in the 9th century.

The fort definitely existed by the 10th century, when it is first mentioned in the historical records. The Kachchhapaghatas controlled the fort at that time, most probably as feudatories of the Chandelas. From 11th century onwards, the Muslim dynasties attacked the fort several times. In 1022 CE, Mahmud of Ghazni besieged the fort for four days. According to Tabaqat-i-Akbari, he lifted the siege in return for a tribute of 35 elephants. Bahauddin Tourghil, a senior slave of the Ghurid ruler Muhammad of Ghor captured the fort in 1196 after a long siege. The Delhi Sultanate lost the fort for a short period before it was recaptured by Iltutmish in 1232 CE.

In 1398, the fort came under the control of the Tomars. The most distinguished of the Tomar rulers was Maan Singh, who commissioned several monuments within the fort. The Delhi Sultan Sikander Lodi tried to capture the fort in 1505 but was unsuccessful. Another attack, by his son Ibrahim Lodi in 1516, resulted in Maan Singh's death. The Tomars ultimately surrendered the fort to the Delhi Sultanate after a year-long siege.

Within a decade, the Mughal Emperor Babur captured the fort from the Delhi Sultanate. The Mughals lost the fort to Sher Shah Suri in 1542. Afterwards, the fort was captured and used by Hemu, the Hindu general and, later, the last Hindu ruler of Delhi, as his base for his many campaigns, but Babur's grandson Akbar recaptured it in 1558. Akbar made the fort a prison for political prisoners. For example, Abu'l-Kasim, son of Kamran and Akbar's first cousin was held and executed at the fort. The last Tomar king of Gwalior, Maharaja Ramshah Tanwar, who had then taken refuge in Mewar and had fought at the Battle of Haldighati. He was killed in the battle along with his three sons (which included Shalivahan Singh Tomar, the heir-apparent)

Guru Hargobind, on 24 June 1606, at age 11, was crowned as the sixth Sikh Guru. At his succession ceremony, he put on two swords: one indicated his spiritual authority (piri) and the other, his temporal authority (miri). Because of the execution of Guru Arjan by Mughal Emperor Jahangir, Guru Hargobind from the very start was a dedicated enemy of the Mughal rule. He advised the Sikhs to arm themselves and fight. The death of his father at the hands of Jahangir prompted him to emphasise the military dimension of the Sikh community. Jahangir responded by jailing the 14-year-old Guru Hargobind at Gwalior Fort in 1609, on the pretext that the fine imposed on Guru Arjan had not been paid by the Sikhs and Guru Hargobind. It is not clear as to how much time he spent as a prisoner. The year of his release appears to have been either 1611 or 1612, when Guru Hargobind was about 16 years old. Persian records, such as Dabistan i Mazahib suggest he was kept in jail for twelve years, including over 1617–1619 in Gwalior, after which he and his camp were kept under Muslim army's surveillance by Jahangir. According to Sikh tradition, Guru Hargobind was released from the bondage of prison on Diwali. This important event in Sikh history is now termed the Bandi Chhor Divas festival.

Aurangzeb's brother, Murad Bakhsh and nephew Sulaiman Shikoh were also executed at the fort. The killings took place in the Man Mandir palace. Sipihr Shikoh was imprisoned at Gwalior Fort from 1659 to 1675. Aurangzeb's son, Muhammad Sultan was imprisoned at the fort from January 1661 to December 1672. After the death of Aurangzeb, the Jat ruler of Gohad, Bhim Singh Rana seized the Gwalior Fort in the Battle of Gwalior. The Marathas had captured many territories held by the declining Mughal Empire in Northern and Central India after the death of Aurangzeb. The Maratha incursions into North India were raids by the Peshwa Bajirao. in 1755–1756, The Marathas took over Gwalior fort by defeating the Jat ruler of Gohad. The Maratha general Mahadaji Shinde (Scindia) captured the fort from the Gohad Rana Chhatar Singh, but later lost it to the British East India Company. On 3 August 1780, a Company force under Captains Popham and Bruce captured the fort in a nighttime raid, scaling the walls with 12 grenadiers and 30 sepoys. Both sides suffered fewer than 20 wounded total. In 1780, the British governor Warren Hastings restored the fort to the Ranas of Gohad. The Marathas recaptured the fort four years later, and this time the British did not intervene because the Ranas of Gohad had become hostile to them. Daulat Rao Sindhia lost the fort to the British during the Second Anglo-Maratha War.

There were frequent changes in the control of the fort between the Scindias and the British between 1808 and 1844. In January 1844, after the Battle of Maharajpur, the fort was occupied by the Gwalior State of the Maratha Scindia family, as a protectorate of the British government. During the 1857 uprising, around 6500 sepoys stationed at Gwalior rebelled against the Company rule, although the company's vassal ruler Jayajirao Scindia remained loyal to the British. The British took control of the fort in June 1858. They rewarded Jayajirao with some territory but retained control of the Gwalior Fort. By 1886, the British were in complete control of India, and the fort no longer had any strategic importance to them. Therefore, they handed over the fort to the Scindia family. The Maratha Scindias continued to rule Gwalior until the independence of India in 1947 and built several monuments including the Jai Vilas Mahal.

Structures

The fort and its premises are well maintained and house many historic monuments including palaces, temples and water tanks. There are also a number of palaces (mahal) including the Man mandir palace, the Gujari mahal, the Jahangir palace, the Karan palace, the Vikram mahal and the Shah Jahan palace. The fort covers an area of 3 square kilometres (1.2 sq mi) and rises 11 metres (36 ft). Its rampart is built around the edge of the hill, connected by six bastions or towers. The profile of the fort has an irregular appearance due to the undulating ground beneath.

There are two gates: one on the northeast side with a long access ramp and the other on the southwest. The main entrance is the ornate Elephant gate (Hathi Pol). The other is the Badalgarh Gate. The Man Mandir palace or citadel is located at the northeast end of the fort. It was built in the 15th century and refurbished in 1648. The water tanks or reservoirs of the fort could provide water to a 15,000 strong garrison, the number required to secure the fort.

The second oldest record of "zero" in the world was found in a small temple (the stone inscription has the second oldest record of the numeric zero symbol having a place value as in the modern decimal notation), which is located on the way to the top. The inscription is around 1500 years old.

Major Monuments

Jain temples

Main articles: Siddhachal Caves and Gopachal rock cut Jain monumentsSiddhachal Jain Rock Cut Caves were built in 15th century. There are eleven Jain temples inside Gwalior fort dedicated to the Jain Tirthankaras. On the southern side are 21 temples cut into the rock with intricately carved of the tirthankaras. Tallest Idol is image of Rishabhanatha or Adinatha, the 1st Tirthankara, is 58 feet 4 inches (17.78 m) high.

Main Temple

Urvahi

The entire area of Gwalior fort is divided into five groups namely Urvahi, Northwest, Northeast, Southwest and the Southeast areas. In the Urvahi area 24 idols of Tirthankar in the padmasana posture, 40 in the kayotsarga posture and around 840 idols carved on the walls and pillars are present. The largest idol is a 58 feet 4 inches high idol of Adinatha outside the Urvahi gate and a 35 feet high idol of Suparshvanatha in the Padmasana in Ek Paththar-ki Bawari (stone tank) area.

Gopachal

There are around 1500 idols on the Gopachal Hill, which includes the size from 6 inch to 57 feet in height. All the idols are carved by cutting the hilly rocks (rock carving) and are very artistic. Most of the idols were built in 1341–1479, during the period of King Dungar Singh and Keerti Singh of Tomar dynasty.

Here is a very beautiful and miraculous colossus of Bhagwan Parsvanath in padmasan posture 42 feet in height & 30 feet in breadth. It is said that in 1527, Mughal emperor Babar after occupying the fort ordered his soldiers to break the idols, when soldiers stroked on the thumb, a miracle was seen, and invaders were compelled to run away. In the period of Mughals, the idols were destroyed, broken fragments of those idols are spread here and there in the fort.

Main colossus of this Kshetra is Parsvanatha's, 42 feet high and 30 feet wide. Together with the place of precept by Bhagwan Parsvanath. This is also the place where Shri 1008 Supratishtha Kevali attained nirvana. There are 26 Jain temples more on this hill.

Mughal Invasion: In 1527, Babur army attacked Gwalior Fort and de-faced these statues. In spite of invasion the early Jaina sculptures of Gwalior have survived in fairly good condition so that their former splendour is not lost.

Teli Temple

Main article: Teli ka Mandir

The Teli ka Mandir is a Hindu temple built by the Pratihara emperor Mihira Bhoja.

It is the oldest part of the fort and has a blend of south and north Indian architectural styles. Within the rectangular structure is a shrine with no pillared pavilions (mandapa) and a South Indian barrel-vaulted roof on top. It has a masonry tower in the North Indian Nagara architectural style with a barrel vaulted roof 25 metres (82 ft) in height. The niches in the outer walls once housed statues but now have Chandrashalas (horseshoe arches) ventilator openings in the north Indian style. The Chandrashala has been compared to the trefoil, a honeycomb design with a series of receding pointed arches within an arch. The entrance door has a torana or archway with sculpted images of river goddesses, romantic couples, foliation decoration and a Garuda. The vertical bands on either side of the door are decorated in a simple fashion with figures that are now badly damaged. Above the door are a small grouping of discs representing the dama laka (finial) of a shikhara. The temple was originally dedicated to Vishnu. It was extensively damaged during Muslim raids, then restored into a Shiva temple by installing a liṅga, while keeping the Vaishnava motifs such as the Garuda. It was refurbished between 1881 and 1883.

Garuda monument

Close to the Teli ka Mandir temple is the Garuda monument, dedicated to Vishnu, is the highest in the fort. It has a mixture of Muslim and Indian architecture. The word Teli comes from the Hindi word meaning oil.

Saas Bahu temples

The Saas Bahu Temples were built in 1092–93 by the Kachchhapaghata dynasty. Dedicated to Vishnu and Shiva, These are pyramidal in shape, built of red sandstone with several stories of beams and pillars but no arches.

Gurdwara Data Bandi Chhor

Gurdwara Data Bandi Chhor was built during 1970s and 1980s at the place where 6th Sikh Guru Hargobind Sahib was arrested and held captive by Mughal Emperor Jahangir in 1609 at the age of 14 years on the pretext that the fine imposed on his father, 5th Sikh Guru Arjan Dev Ji had not been paid by the Sikhs and Guru Hargobind. According to Surjit Singh Gandhi, 52 Hindu Rajas who were imprisoned in the fort as hostages for "millions of rupees" and for opposing the Mughal empire were dismayed as they were losing a spiritual mentor. On getting released Guru Hargobind requested the Rajas to be freed along with him as well. Jahangir allowed Guru Hargobind to free as many rajas he could as long as they are holding on to the guru while leaving the prison. Guru sahib got a special gown stitched which had 52 hems. As Guru Hargobind left the fort, all the captive kings caught the hems of the cloak and came out along with him.

Palace

Man mandir palace

The Man mandir palace was built by the King of Tomar Dynasty – Maharaja Man Singh in 15th century. Man Mandir is often referred as a Painted Palace because the painted effect of the Man Mandir Palace is due to the use of styled tiles of turquoise, green and yellow used extensively in a geometric pattern.

Hathi Pol

The Hathi Pol gate (or Hathiya Paur), located on the southeast, leads to the Man mandir palace. It is the last of a series of seven gates. It is named for a life-sized statue of an elephant (hathi) that once adorned the gate. The gate was built in stone with cylindrical towers crowned with cupola domes. Carved parapets link the domes.

Karn mahal

The Karan mahal is another significant monument at Gwalior Fort. The Karn mahal was built by the second king of the Tomar dynasty, Kirti Singh. He was also known as Karn Singh, hence the name of the palace.

Vikram mahal

The Vikram mahal (also known as the Vikram mandir, as it once hosted a temple of Shiva) was built by Vikramaditya Singh, the elder son of Maharaja Mansingh. He was a devotee of shiva. The temple was destroyed during Mughal period but now has been re-established in the front open space of the Vikram mahal.

Chhatri of Bhim Singh Rana

This chhatri (cupola or domed shaped pavilion) was built as a memorial to Bhim Singh Rana (1707–1756), a ruler of Gohad state. It was built by his successor, Chhatra Singh. Bhim Singh occupied Gwalior fort in 1740 when the Mughal Satrap, Ali Khan, surrendered. In 1754, Bhim Singh built a bhimtal (a lake) as a monument at the fort. Chhatra Singh built the memorial chhatri near the bhimtal.

Museum

Main article: Gujari Mahal Archaeological Museum

The Gujari Mahal now a museum, was built by Raja Man Singh Tomar for his wife Mrignayani, a Gujar princess. She demanded a separate palace for herself with a regular water supply through an aqueduct from the nearby Rai River. The palace has been converted into an archaeological museum. Rare artefacts at the museum include Hindu and Jain sculptures dated to the 1st and 2nd centuries BC; miniature statue of Salabhanjika; terracotta items and replicas of frescoes seen in the Bagh Caves.

Other monuments

There are several other monuments built inside the fort area. These include the Scindia School (Originally an exclusive school for the sons of Indian princes and nobles) that was founded by Madho Rao Scindia in 1897.

Gallery

-

Interior of Jain Temple, Gwalior Fort

Interior of Jain Temple, Gwalior Fort

-

Pond at Gwalior Fort.

Pond at Gwalior Fort.

-

View of Gwalior Fort from the north-west. c. 1790

View of Gwalior Fort from the north-west. c. 1790

-

The fort bastions.

The fort bastions.

-

The north room, Man Mandir.

The north room, Man Mandir.

-

Sas-Bahu temple.

Sas-Bahu temple.

-

Gate of Teli ka Mandir.

Gate of Teli ka Mandir.

-

Gwalior Fort – Morning View

Gwalior Fort – Morning View

-

Gwalior fort

Gwalior fort

-

Gurudwara Shri Data Bandi Chhor Shahib

Gurudwara Shri Data Bandi Chhor Shahib

References

- ^ Paul E. Schellinger & Robert M. Salkin 1994, p. 312.

- "Gibraltar of India". 19 March 2022.

- "Gwalior Monument". Archaeological Survey of India Bhopal.

- Romila Thapar (2003). The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. Penguin Books Limited. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-14-193742-7.

Other claiming to be Rajput and descent from Solar and lunar lines established themselves as local kings in Western and Central India. Among these were the Chandelas present in 12th century in Bundelkhand, the Tomaras also subject to the earlier Pratiharas ruling in Haryana region near Dhilaka, now Delhi, around 736 AD and later established themselves in Gwalior region

- ^ You Can Visit the World's Oldest Zero at a Temple in India Archived 16 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Smithsonian magazine.

- Joseph, George Gheverghese (2016). Indian Mathematics: Engaging with the World from Ancient to Modern Times. World Scientific. ISBN 978-1786340634.

In a temple on the path up to Gwalior Fort where we find a circular zero in the terminal position.

- Fodor E. et al. "Fodor's India." D. McKay 1971. p. 293. Accessed at Google Books 30 November 2013.]

- William Curtis, Fodor, Eugene, 1905 Fodor's India D. McKay., 1971

- "Cowherd's Hill". Britannica. 15 October 2024. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- Oldham R. D. "A manual of the geology of India." ISBN 978-1108072540 Cambridge University Press 2011. p. 65 Accessed at Google Books 30 November 2013.

- ^ Konstantin Nossov & Brain Delf 2006, p. 11.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, p. 59.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, pp. 80–82.

- Iqtidar Alam Khan (2008). Historical Dictionary of Medieval India. Scarecrow Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8108-5503-8.

- ^ Paul E. Schellinger & Robert M. Salkin 1994, p. 314.

- ^ Torton E. "A gazetteer of the territories under the government of the East-India company, and of the native states on the continent of India, Volume 2" W. H. Allen & Co. 1854.

- Louis E. Fenech, Martyrdom in the Sikh Tradition, Oxford University Press, pages 118–121

- HS Singha (2009), Sikh Studies, Book 7, Hemkunt Press, ISBN 978-8170102458, pages 18–19

- HS Syan (2013), Sikh Militancy in the Seventeenth Century, IB Tauris, ISBN 978-1780762500, pages 48–55

- V. D. Mahajan (1970). Muslim Rule in India. S. Chand, New Delhi, p.223.

- Phyllis G. Jestice (2004). Holy People of the World: A Cross-cultural Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 345, 346. ISBN 9781576073551.

- ^ Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed. A & C Black. p. 48. ISBN 9781441117083.

- Fauja Singh (2011). "Hargobind Guru (1595–1644)". In Harbans Singh (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Vol. 2, E–L (3rd ed.). Patiala: Punjabi University. pp. 232–235. ISBN 978-8173802041 – via Internet Archive.

- The Sikh Review. Vol. 42–43. Sikh Cultural Centre. 1994. pp. 15–16.

- Eleanor Nesbitt (2016). Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 28–29, 59, 120–131. ISBN 978-0-19-874557-0.

- ^ Tony McClenaghan 1996, p. 131.

- Paul E. Schellinger & Robert M. Salkin 1994, p. 316.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "History of Gwalior | ग्वालियर का इतिहास". 27 January 2019 – via YouTube.

- "Temples of Gwalior" Archived 20 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine Kamat's Potpourri Webpage. Accessed 1 December 2013.

- Joseph, George Gheverghese (2016). Indian Mathematics: Engaging with the World from Ancient to Modern Times. World Scientific. ISBN 978-1786340634.

In a temple on the path up to Gwalior Fort where we find a circular zero in the terminal position.

- Kurt Titze; Klaus Bruhn (1998). Jainism: A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-violence. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 106–110. ISBN 978-81-208-1534-6.

- ^ Cunningham, Alexander (1871). "XVI. Gwaliar, or Gwalior (Gwalior Fort: Rock Sculptures)". Archaeological Survey of India: Four Reports Made During the Year 1862–63–64-65. Vol. 2. Simla: Government Central Press. pp. 364–370 – via Internet Archive.

- "Gwalior Fort, Gwalior". Archaeological Survey of India, Bhopal Circle. Government of India, Ministry of Culture. 2014. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019.

- "Jain Samaj". Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- "jain.org.in". Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- K. D. Bajpai (2006). History of Gopāchala. Bharatiya Jnanpith. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-263-1155-2.

- George Michell (1977). The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to Its Meaning and Forms. University of Chicago Press. pp. 117 with footnotes. ISBN 978-0-226-53230-1.

- Margaret Prosser Allen (1991). Ornament in Indian Architecture. University of Delaware Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-87413-399-8.

- Allen M. P. "Ornament in Indian architecture." University of Delaware Press 1991. ISBN 0-87413-399-8.

- ASI Report: Gwalior, A Cunningham, pp. 356–359

- Sengupta, Guatam; Lambah, Abha Narain, eds. (2012). Custodians of the past: 150 years of the Archaeological Survey of India. Archaeological Survey of India, Ministry of Culture, Government of India. p. 32. ISBN 978-93-5086-199-8.

- Henry Hardy Cole; (Curator of Ancient Monuments, India) (1882). Preservation of National Monuments: Report of the Curator of Ancient Monuments in India (Report). Simla: Government Central Branch Press. p. 17.

- Kurt Titze; Klaus Bruhn (1998). Jainism: A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-violence. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-81-208-1534-6.

- Margaret Prosser Allen (1991). Ornament in Indian Architecture. University of Delaware Press. pp. 211–212. ISBN 978-0-87413-399-8.

Bibliography

- Konstantin Nossov; Brain Delf (2006). Indian Castles 1206–1526 (Illustrated ed.). Osprey. ISBN 1-84603-065-X.

- Paul E. Schellinger; Robert M. Salkin, eds. (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Vol. 5. Routledge/Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1884964046.

- Sisirkumar Mitra (1977). The Early Rulers of Khajurāho. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120819979.

- Tony McClenaghan (1996). Indian Princely Medals. Lancer. ISBN 978-1897829196.

- Tillotson G. H. R. "The Rajput Palaces – The Development of an Architectural Style" Yale University Press. New Haven and London 1987. First edition. Hardback. ISBN 0-300-03738-4

External links

- Interesting Facts About Gwalior Fort

Gwalior Fort travel guide from Wikivoyage

Gwalior Fort travel guide from Wikivoyage

| Gwalior topics | |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Geography | |

| Buildings | |

| Transport | |

| Economy | |

| Education | |

| Civic | |

| Culture | |

| Other topics | |

| Forts in Madhya Pradesh | |

|---|---|