| Revision as of 14:30, 4 August 2006 edit137.21.66.161 (talk) →Aži Dahāka in popular culture← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 10:07, 5 December 2024 edit undoBaratiiman (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users8,984 editsNo edit summaryTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| (497 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Evil figure in Iranian mythology}}{{For|the ''Homestuck'' character|Equius Zahhak}}{{redirect|Zahak|the city in southeastern Iran|Zehak|the village in Hormozgan Province|Zahak-e Pain}} | |||

| '''Zahhāk''' or '''Zohhāk''' (in {{lang-fa|ضحاک}}) is a figure of ], evident in ancient Iranian ] as '''Aži Dahāka''', the name by which he also appears in the texts of the ]. In ] he is called Dahāg or Bēvar-Asp, the latter meaning " 10,000 horses". | |||

| {{More citations needed|date=June 2019}} | |||

| {{cleanup-lang|date=January 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox person | |||

| | honorific_prefix = ] | |||

| | name = <!-- use common name/article title -->Zahhak | |||

| | honorific_suffix = A king of Iranian myths and legends | |||

| | image = Mir Musavvir 002 (Zahhak).jpg | |||

| | image_upright = | |||

| | landscape = <!-- yes, if wide image, otherwise leave blank --> | |||

| | alt = <!-- descriptive text for use by speech synthesis (text-to-speech) software --> | |||

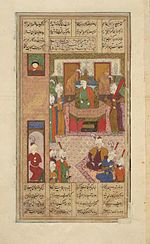

| | caption = Zahhak in the ] | |||

| | native_name = | |||

| | native_name_lang = | |||

| | pronunciation = | |||

| | birth_name = <!-- only use if different from name --> | |||

| | birth_date = <!-- {{Birth date and age|YYYY|MM|DD}} for living people supply only the year with {{Birth year and age|YYYY}} unless the exact date is already widely published, as per ]. For people who have died, use {{Birth date|YYYY|MM|DD}}. --> | |||

| | birth_place = | |||

| | baptised = <!-- will not display if birth_date is entered --> | |||

| | disappeared_date = <!-- {{Disappeared date and age|YYYY|MM|DD|YYYY|MM|DD}} (disappeared date then birth date) --> | |||

| | disappeared_place = | |||

| | disappeared_status = | |||

| | death_date = <!-- {{Death date and age|YYYY|MM|DD|YYYY|MM|DD}} (enter DEATH date then BIRTH date (e.g., ...|1967|31|8|1908|28|2}} use both this parameter and |birth_date to display the person's date of birth, date of death, and age at death) --> | |||

| | death_place = | |||

| | death_cause = <!--should only be included when the cause of death has significance for the subject's notability--> | |||

| | body_discovered = | |||

| | resting_place = | |||

| | resting_place_coordinates = <!-- {{coord|LAT|LONG|type:landmark|display=inline}} --> | |||

| | burial_place = <!-- may be used instead of resting_place and resting_place_coordinates (displays "Burial place" as label) --> | |||

| | burial_coordinates = <!-- {{coord|LAT|LONG|type:landmark|display=inline}} --> | |||

| | monuments = | |||

| | nationality = | |||

| | other_names = Azhi Dahāka{{-}}Bēvar Asp | |||

| | siglum = | |||

| | citizenship = | |||

| | education = | |||

| | alma_mater = | |||

| | occupation = | |||

| | years_active = | |||

| | era = | |||

| | employer = | |||

| | organization = | |||

| | agent = <!-- Discouraged in most cases, specifically when promotional, and requiring a reliable source --> | |||

| | known_for = | |||

| | notable_works = <!-- produces label "Notable work"; may be overridden by |credits=, which produces label "Notable credit(s)"; or by |works=, which produces label "Works"; or by |label_name=, which produces label "Label(s)" --> | |||

| | style = | |||

| | net_worth = <!-- Net worth should be supported with a citation from a reliable source --> | |||

| | height = <!-- "X cm", "X m" or "X ft Y in" plus optional reference (conversions are automatic) --> | |||

| | television = | |||

| | title = <!-- Formal/awarded/job title. The parameter |office=may be used as an alternative when the label is better rendered as "Office" (e.g. public office or appointments) --> | |||

| | term = | |||

| | predecessor = | |||

| | successor = | |||

| | party = | |||

| | movement = | |||

| | opponents = | |||

| | boards = | |||

| | criminal_charges = <!-- Criminality parameters should be supported with citations from reliable sources --> | |||

| | criminal_penalty = | |||

| | criminal_status = | |||

| | spouse = <!-- Use article title or common name -->]{{-}}] | |||

| | partner = <!-- (unmarried long-term partner) --> | |||

| | children = | |||

| | parents = <!-- overrides mother and father parameters --> | |||

| | mother = <!-- may be used (optionally with father parameter) in place of parents parameter (displays "Parent(s)" as label) --> | |||

| | father = <!-- may be used (optionally with mother parameter) in place of parents parameter (displays "Parent(s)" as label) -->Mardas | |||

| | relatives = | |||

| | family = | |||

| | callsign = | |||

| | awards = | |||

| | website = <!-- {{URL|example.com}} --> | |||

| | module = | |||

| | module2 = | |||

| | module3 = | |||

| | module4 = | |||

| | module5 = | |||

| | module6 = | |||

| | signature = | |||

| | signature_size = | |||

| | signature_alt = | |||

| | footnotes = | |||

| }} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| '''Zahhāk''' or '''Zahāk'''<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.academia.edu/2916523 |title=zahāk or wolflike serpent in the Persian and kurdish Mythology | khosro gholizadeh |publisher=Academia.edu |date=1970-01-01 |access-date=2015-12-23|last1=Gholizadeh |first1=Khosro }}</ref> ({{IPA|fa|zæhɒːk|pron}}<ref>{{cite web |author=loghatnaameh.com |url=http://www.loghatnaameh.org/dehkhodaworddetail-cd5088b4eaa749f8a25507f1a63b9fc7-fa.html |title=ضحاک بیوراسب | پارسی ویکی |publisher=Loghatnaameh.org |access-date=2015-12-23 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140201182300/http://www.loghatnaameh.org/dehkhodaworddetail-cd5088b4eaa749f8a25507f1a63b9fc7-fa.html |archive-date=2014-02-01 }}</ref>) ({{langx|fa|ضحّاک}}), also known as '''Zahhak the Snake Shoulder''' ({{langx|fa|ضحاک ماردوش|Zahhāk-e Mārdoush}}), is an evil figure in ], evident in ancient Persian ] as '''Azhi Dahāka''' ({{langx|fa|اژی دهاک}}), the name by which he also appears in the texts of the '']''.<ref name="Bane 2012">{{cite book |last=Bane |first=Theresa |title=Encyclopedia of Demons in World Religions and Cultures |publisher=McFarland |year=2012 |isbn=978-0-7864-8894-0 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=njDRfG6YVb8C&pg=PA335 |access-date=1 October 2018 |page=335}}</ref> In ] he is called '''Dahāg''' ({{langx|fa|دهاگ}}) or '''Bēvar Asp''' ({{langx|fa|بیور اسپ}}) the latter meaning "he who has 10,000 horses".<ref>{{lang|fa|کجا بیوراسپش همی خواندند / چُنین نام بر پهلوی راندند<br />کجا بیور از پهلوانی شمار / بود بر زبان دری ده‌هزار}}{{cn|date=January 2024}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Characters of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh |url=http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/shahnameh/characters.htm |publisher=heritageinstitute.com |access-date=26 February 2016}}</ref> In ], Zahhak (going under the name Aži Dahāka) is considered the son of ], the foe of ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/iran-iv-myths-and-legends |title=Persia: iv. Myths an Legends |publisher=Encyclopaedia Iranica |access-date=2015-12-23}}</ref> In the '']'' of ], Zahhāk is the son of a ruler named Merdās. | |||

| ==Etymology and derived words== | ==Etymology and derived words== | ||

| ''Aži'' (nominative ''ažiš'') is the ] word for "serpent" or "dragon".<ref>For Azi Dahaka as dragon see: Ingersoll, Ernest, et al., (2013). ''The Illustrated Book of Dragons and Dragon Lore''. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN B00D959PJ0</ref> It is ] to the ] word ''ahi'', "snake", and without a sinister implication. | |||

| The meaning of |

The original meaning of ''dahāka'' is uncertain. Among the meanings suggested are "stinging" (source uncertain), "burning" (cf. ] ''dahana''), "man" or "manlike" (cf. ] ''daha''), "huge" or "foreign" (cf. the ] people and the Vedic ]s). In Persian mythology, ''Dahāka'' is treated as a proper noun, while the form ''Zahhāk'', which appears in the '']'', was created through the influence of the unrelated ] word ''ḍaḥḥāk'' (ضَحَّاك) meaning "one who laughs". | ||

| The Avestan term ''Aži Dahāka'' and the Middle Persian ''aždahāg'' are the source of the Middle Persian ] demon of greed ''Až'',<ref>Appears numerous time in, for example: D. N. MacKenzie, ''Mani’s Šābuhragān'', pt. 1 (text and translation), BSOAS 42/3, 1979, pp. 500-34, pt. 2 (glossary and plates), BSOAS 43/2, 1980, pp. 288-310.</ref> Old Armenian mythological figure '']'', ] '<nowiki/>''aždehâ''/'']','' ({{lang|fa|اژدها}}) ] '<nowiki/>''aždaho','' ({{lang|tg|аждаҳо}}) ] '<nowiki/>''aždahā''' ({{lang|ur|{{nq|اژدہا}}}}), as well as the ] ''ejdîha'' ({{lang|ckb|ئەژدیها}}) which usually mean "dragon". | |||

| '''Aži Dahāka''' is the source of the modern ] word '''azhdahā''' or '''ezhdehā''' اژدها (Middle Persian '''azdahāg''') meaning "dragon", often used of a dragon depicted upon a banner of war. | |||

| The name also migrated to Eastern Europe,<ref>Detelić, Mirjana. "St Paraskeve in the Balkan Context" In: ''Folklore'' 121, no. 1 (2010): 101 (footnote nr. 12). Accessed March 24, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29534110.</ref> assumed the form "]" and the meaning "dragon", "dragoness"<ref>Erben, Karel Jaromír; Strickland, Walter William. ''''. London: G. Standring. 1907. p. 130.</ref> or "water snake"<ref>Kropej, Monika. ''Supernatural beings from Slovenian myth and folktales''. Ljubljana: Institute of Slovenian Ethnology at ZRC SAZU. 2012. p. 102. {{ISBN|978-961-254-428-7}}</ref> in Balkanic and Slavic languages.<ref>Kappler, Matthias. ''Turkish Language Contacts in Southeastern Europe''. Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press, 2010. p. 256. https://doi.org/10.31826/9781463225612</ref> | |||

| The ] group of ]s are named from an ] word for "dragon" that ultimately comes from '''Aži Dahāka'''. | |||

| Despite the negative aspect of ''Aži Dahāka'' in mythology, dragons have been used on some banners of war throughout the history of ]. | |||

| ==The Ahi / Aži in Indo-Iranian tradition== | |||

| Stories of monstrous serpents who are killed or imprisoned by heroes or divine beings may date back to prehistory, and are found in the ] of many Indo-European peoples. The most significant comparisons can be made with the closely related ] myths of ], where an '''ahi''' (equivalent to Avestan ''aži'') called ] was the principal foe of the Vedic god ], who received from this myth the name '''Vṛtrahan''' or "striker of Vṛtra" (-han related to Persian زدن ''zadan'' "to strike"). That a similar myth existed early in the history of the Iranian peoples is implied by the existence of the ] name of the Avestan ] ], which becomes the modern ] Bahrām. | |||

| The ] group of ]s are named from a ] word for "]" that ultimately comes from ''Aži Dahāka''. | |||

| Vərəθraγna was not remembered as a serpent-killer in Iranian tradition, but two other stories of fights against an ''aži'' survived. In one, the hero ] (Middle Persian Kirsāsp) kills the horned dragon ''Aži Sruvara'' or ''Aži Zairita'' (Middle Persian ''Az ī Srūwar''), a robber and murderer, devourer of horses and men, "the poisonous yellow one, over whom poison flowed the height of a spear", after mistakenly cooking his lunch on its back! Several other ''aži''s are mentioned in the Avestan literature (''Aži Raoiδita'', ''Aži Višāpa''), but the only other one with a story is Aži Dahāka. | |||

| ==Aži Dahāka (Dahāg) in Zoroastrian literature== | ==Aži Dahāka (Dahāg) in Zoroastrian literature== | ||

| ]. Modified <abbr>c.</abbr> 1926, as many medieval pieces were to make them more attractive.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Bowl Depicting King Zahhak with Snakes Protruding from His Shoulders |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/451774 |access-date=2024-04-24 |website=The Metropolitan Museum of Art |language=en}}</ref>]] | |||

| Aži Dahāka is the most significant and long-lasting of the ''aži''s of the ], the earliest religious texts of ]. He is described as a monster with three mouths, six eyes, and three heads (presumably meaning three heads with one mouth and two eyes each), cunning, strong and demonic. But in other respects Aži Dahāka has human qualities, and is never a mere animal. | |||

| ] is the most significant and long-lasting of the ''aži''s of the ], the earliest religious texts of ]. He is described as a monster with three mouths, six eyes, and ], cunning, strong, and demonic. In other respects Aži Dahāka has human qualities, and is never a mere animal.{{Citation needed|date=January 2019}} | |||

| Aži Dahāka appears in several of the Avestan myths and is mentioned parenthetically in many more places in Zoroastrian literature. | Aži Dahāka appears in several of the Avestan myths and is mentioned parenthetically in many more places in Zoroastrian literature.{{Citation needed|date=January 2019}} | ||

| In a post-Avestan Zoroastrian text, the ''Dēnkard'', Aži Dahāka is |

In a post-Avestan Zoroastrian text, the ''Dēnkard'', Aži Dahāka is possessed of all possible sins and evil counsels, the opposite of the good king ] (or ]). The name Dahāg (Dahāka) is punningly interpreted as meaning "having ten (''dah'') sins".{{Citation needed|date=January 2019}} His mother is Wadag (or Ōdag), herself described as a great sinner, who committed incest with her son.{{Citation needed|date=January 2019}} | ||

| In the Avesta, Aži Dahāka is said to have lived in the inaccessible fortress of Kuuirinta in the land of Baβri, where he worshipped the yazatas Arədvī Sūrā (]), divinity of the rivers, and Vayu |

In the Avesta, Aži Dahāka is said to have lived in the inaccessible fortress of Kuuirinta in the land of Baβri, where he worshipped the yazatas Arədvī Sūrā (]), divinity of the rivers, and ] divinity of the storm-wind. Based on the similarity between Baβri and ] Bābiru (]), later Zoroastrians localized Aži Dahāka in Mesopotamia, though the identification is open to doubt. Aži Dahāka asked these two yazatas for power to depopulate the world. Being representatives of the Good, they refused. | ||

| In one Avestan text, Aži Dahāka has a brother named Spitiyura. Together they attack the hero Yima (]) and cut him in half with a saw, but are then beaten back by the ] ], the divine spirit of |

In one Avestan text, Aži Dahāka has a brother named Spitiyura. Together they attack the hero Yima (]){{clarify|date=January 2019|reason=is this meant as a source?}} and cut him in half with a saw, but are then beaten back by the ] ], the divine spirit of fire.{{Citation needed|date=January 2019}} | ||

| According to the post-Avestan texts, following the death of Jam ī Xšēd (]), Dahāg gained kingly rule. |

According to the post-Avestan texts, following the death of Jam ī Xšēd (]),{{clarify|date=January 2019|reason=is this meant as a source?}} Dahāg gained kingly rule. Another late Zoroastrian text, the ''Mēnog ī xrad'', says this was ultimately good, because if Dahāg had not become king, the rule would have been taken by the immortal demon Xešm (]), and so evil would have ruled upon the earth until the end of the world. | ||

| Dahāg is said to have ruled for a thousand years, starting from 100 years after Jam lost his royal glory (see ]). He is described as a sorcerer who ruled with the aid of demons |

Dahāg is said to have ruled for a thousand years, starting from 100 years after Jam lost his ], his royal glory (see ]). He is described as a sorcerer who ruled with the aid of demons, the ]s (divs). | ||

| The Avesta identifies the person who finally disposed of Aži Dahāka as ] son of Aθβiya, in Middle Persian called Frēdōn. The Avesta has little to say about the nature of Θraētaona's defeat of Aži Dahāka, other than that it enabled him to liberate Arənavāci and Savaŋhavāci, the two most beautiful women in the world. Later sources, especially the ], provide more detail. |

The Avesta identifies the person who finally disposed of Aži Dahāka as ] son of ], in Middle Persian called Frēdōn. The Avesta has little to say about the nature of Θraētaona's defeat of Aži Dahāka, other than that it enabled him to liberate Arənavāci and Savaŋhavāci, the two most beautiful women in the world. Later sources, especially the ], provide more detail. Feyredon is said to have been endowed with the divine radiance of kings ('']'', New Persian ''farr'') for life, and was able to defeat Dahāg, striking him with a mace. However, when he did so, vermin (snakes, insects and the like) emerged from the wounds, and the god ] told him not to kill Dahāg, lest the world become infected with these creatures. Instead, Frēdōn chained Dahāg up and imprisoned him on the mythical Mt. Damāvand{{Citation needed|date=January 2019}} (later identified with ]). | ||

| The Middle Persian sources also prophesy that at the end of the world, Dahāg will at last burst his bonds and ravage the world, consuming one in three humans and livestock. |

The Middle Persian sources also prophesy that at the end of the world, Dahāg will at last burst his bonds and ravage the world, consuming one in three humans and livestock. ], the ancient hero who had killed the Az ī Srūwar, returns to life to kill Dahāg.{{Citation needed|date=January 2019}} | ||

| == |

==Zahhak in the Shahname== | ||

| In ]'s epic poem, the ], written c. 1000 AD, the legend |

In ]'s epic poem, the ], written c. 1000 AD and part of Iranian folklore, the legend is retold with the main character given the name of Zahhāk and changed from a supernatural monster into an evil human being. | ||

| === |

===Zahhak in Persia=== | ||

| ]n painting, depicting Zahhāk ascending on the royal throne.]] | |||

| According to Ferdowsi, Zahhāk (] transliteration: Ḍaḥḥāk or Ḍuḥḥāk) was born as the son of an Arab ruler named Merdās. Because of his Arab origins, he is sometimes called Zahhāk-e Tāzi, "the Arabian Zahhāk". He was handsome and clever, but had no stability of character and was easily influenced by evil counsellors. ] therefore chose him as the tool for his plans for world domination. | |||

| According to ], Zahhāk was born as the son of a ruler named Merdās ({{langx|fa|مرداس}}). Because of his ] lineage, he is sometimes called '''Zahhāk-e Tāzī''' ({{langx|fa|ضحاکِ تازی}}), meaning "Zahhāk the ]". He is handsome and clever, but has no stability of character and is easily influenced by his counselors. ] therefore chooses him as a tool to sow disorder and chaos. When Zahhāk is a young man, Ahriman first appears to him as a glib, flattering companion, and by degrees convinces him to kill his own father and inherit his kingdom, treasures and army. Zahhāk digs a deep pit covered over with leaves in a path to a garden where Merdās would pray each morning; Merdās falls in and is killed. Zahhāk thus ascends to the throne. | |||

| Ahriman then presents himself to Zahhāk as a marvelous cook. After he presents Zahhāk with many days of sumptuous feasts (introducing meat to the formerly vegetarian human cuisine), Zahhāk is willing to give Ahriman whatever he wants. Ahriman merely asks to kiss Zahhāk on his two shoulders, and Zahhāk permits this. Ahriman places his lips upon Zahhāk's shoulders and suddenly disappears. At once, two black snakes grow from Zahhāk's shoulders. They cannot be surgically removed, as another snake grows to replace one that has been severed. Ahriman appears to Zahhāk in the form of a skilled physician. He counsels Zahhāk that attempting to remove the snakes is fruitless, and that the only means of soothing the snakes and preventing them from killing him is to sate their hunger by supplying them with a stew made from two human brains every day. | |||

| When Zahhāk was a young man, Ahriman first appeared to him as a glib, flattering companion, and by degrees convinced him that he ought to kill his own father and take over his territories. He taught him to dig a deep pit covered over with leaves in a place where Merdās was accustomed to walk; Merdās fell in and was killed. Zahhāk thus became both parricide and king at the same time. | |||

| ===Zahhāk the Emperor=== | |||

| Ahriman now took another guise, and presented himself to Zahhāk as a marvellous cook. After he had presented Zahhāk with many days of sumptuous feasts, Zahhāk was willing to give Ahriman whatever he wanted. Ahriman merely asked to kiss Zahhāk on his two shoulders. Zahhāk permitted this; but when Ahriman had touched his lips to Zahhāk's shoulders, he immediately vanished. At once, two black snakes grew out of Zahhāk's shoulders. They could not be surgically removed, for as soon as one snake-head had been cut off, another took its place. | |||

| ]n Princess Tigranuhi, daughter of ], before wedding with ]. Azhdahak is identified as ] in Armenian sources.]] | |||

| At this time, ], the ruler of the world, becomes arrogant and loses his divine right to rule. Zahhāk presents himself as a savior to discontented Iranians seeking a new ruler. Collecting a great army, Zahhāk hunts Jamshid for many years before finally capturing him. Zahhāk executes Jamshid by sawing him in half and ascends to Jamshid's prior throne. Among his slaves are two of Jamshid's daughters, ] and ] (the Avestan Arənavāci and Savaŋhavāci). Each day, Zahhāk's agents seize two men and execute them so that their brains can feed Zahhāk's snakes. Two men, called Armayel and Garmayel, seek to rescue people from being killed from the snakes by learning cookery and becoming Zahhāk's royal chefs. Each day, Armayel and Garmayel save one of the two men by sending him off to the mountains and faraway plains, and substitute the man's brain with that of a sheep. The saved men are the mythological progenitors of the ].<ref>Masudi. ''Les Prairies d’Or''. Trans. Barbier de Meynard and Pavet de Courteille, 9 vols. Paris: La Société Asiatique, 1861.</ref><ref>Özoglu, H. (2004). ''Kurdish Notables and the Ottoman State: Evolving Identities, Competing Loyalties, and Shifting Boundaries''. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 30.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Ahriman now appeared to Zahhāk in the form of a skilled physician. He counselled Zahhāk that the only remedy was to let the snakes remain on his shoulders, and sate their hunger by supplying them with human brains for food every day. If this were done, eventually the snakes might wither away. | |||

| Zahhāk's tyranny over the world lasts for centuries. One night, Zahhāk dreams of three warriors attacking him. The youngest warrior knocks Zahhāk down with his mace, ties him up, and drags him off toward ] as a large crowd follows. Zahhāk wakes and shouts so loudly that the pillars of the palace shake. Following Arnavāz's counsel, Zahhāk summons wise men and scholars to interpret his dream. His hesitant counsellors remain silent until the most fearless of the men reports that the dream is a vision of the end of Zahhāk's reign at the hands of ], the young man with the mace. Zahhāk is thrilled to learn the identity of his enemy, and orders his agents to search the entire country for Fereydun and capture him. The agents learn that Fereydun is a boy being nourished on the milk of the marvelous cow Barmāyeh. The spies trace Barmāyeh to the highland meadows where it grazes, but Fereydun and his mother have already fled before them. The agents kill the cow, but are forced to return to Zahhāk with their mission unfulfilled. | |||

| ===Revolution against Zahhāk=== | |||

| This story is Ferdowsi's way of reconciling the descriptions of Dahāg as a three-headed dragon monster and those stories which treat him as a human king. According to Ferdowsi, Zahhāk is originally human, but through the magic of Ahriman he becomes a monster; he does, in fact, have three heads, the two snake heads and one human head; and the snakes remind us of his original character as a dragon. | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Kāve}} | |||

| Zahhāk lives the next few years in fear and anxiety of Fereydun, and thus writes a document testifying to the virtue and righteousness of his kingdom that would be certified by the kingdom's elders and social elite, in the hope that his enemy would be convinced against exacting vengeance. Much of the summoned assembly indulge the testimony out of fear for their lives. However, a blacksmith named ] (Kaveh) speaks out in anger for his children having been murdered to feed Zahhāk's snakes, and for his final remaining son being sentenced to the same fate. Zahhāk orders for Kāva's son to be released in a bid to coerce Kāva into certifying the document, but Kāva tears up the document, leaves the court, and creates a flag out of his blacksmith's apron as a standard of rebellion – the ], ''derafsh-e Kāviyānī'' (درفش کاویانی). Kāva proclaims himself in support of Fereydun as ruler, and rallies a crowd to follow him to the Alborz mountains, where Fereydun is now living as a young man. Fereydun agrees to lead the people against Zahhāk and has a mace made for him with a head like that of an ox. | |||

| Fereydun goes forth to fight against Zahhāk, who has already left his capital, which falls to Fereydun with small resistance. Fereydun frees all of Zahhāk's prisoners, including Arnavāz and Shahrnāz. Kondrow, Zahhāk's treasurer, pretends to submit to Fereydun, but discreetly escapes to Zahhāk and reports to him what has happened. Zahhāk initially dismisses the matter, but he is incensed to learn that Fereydun has seated Jamshid's daughters on thrones beside him like his queens, and immediately hastens back to his city to attack Fereydun. Zahhāk finds his capital held strongly against him, and his army is in peril from the defense of the city. Seeing that he cannot reduce the city, he sneaks into his own palace as a spy and attempts to assassinate Arnavāz and Shahrnāz. Fereydun strikes Zahhāk down with his ox-headed mace, but does not kill him; on the advice of an angel, he binds Zahhāk and imprisons him in a cave underneath Mount Damāvand. Fereydun binds Zahhāk with a lion's pelt tied to great nails fixed into the walls of the cavern, where Zahhāk will remain until the end of the world. | |||

| The characterization of Zahhāk as an Arab in part reflects the earlier association of Dahāg with the Semitic peoples of Iraq, but probably also reflects the continued resentment of many Iranians at the ] ]. | |||

| ==Place names== | |||

| ===Zahhāk the Emperor=== | |||

| "]" is the name of an ancient ruin in ], ], ] which according to various experts, was inhabited from the second millennia BC until the ]-era. First excavated in the 19th century by British archeologists, ] has been studying the structure in 6 phases.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.chn.ir/news/?section=2&id=31507 |script-title=fa:قلعهزهاك 30 قرن مسكوني بود |trans-title=Castle inhabited 30 centuries |publisher=Cultural Heritage News Agency |date=2007-03-04<!--1385/3/4 SH--> |access-date=2006-05-28 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061001142816/http://www.chn.ir/news/?section=2&id=31507 |archive-date=2006-10-01 |language=fa}}</ref> | |||

| About this time, ], who was then the ruler of the world, through his arrogance lost his divine right to rule. Zahhāk presented himself as a savior to those discontented Iranians who wanted a new ruler. Collecting a great army, he marched against Jamshid, who fled when he saw that he could not resist Zahhāk. Zahhāk hunted Jamshid for many years, and at last caught him and subjected him to a miserable death -- he had Jamshid sawn in half. Zahhāk now became the ruler of the entire world. | |||

| ==In popular culture== | |||

| Zahhāk's two snake heads still craved human brains for food, so every day Zahhāk's spies would seize two men, and execute them so their brains could feed the snakes. But Zahhāk had among his slaves two of Jamshid's daughters, Arnavāz and Shahrnavāz (the Avestan Arənavāci and Savaŋhavāci). They managed things so that the brains of a sheep could be substituted for one of the human beings, but they could not save all of the people whom Zahhāk's servants captured. | |||

| *The tale of Zahhak's defeat of Jamshid and subsequent defeat to Fereydun serves as the backstory of the 1992 Sega Game Gear video game '']''. A descendant of Zahhak is a major antagonist in the game's plot. | |||

| *In the ''Xenaverse'', Zahhak (referred to as '']'') is the supernatural adversary whom both ] and later Hercules on '']'' must defeat in order to save the world from utter destruction. When Dahak appears on Hercules, his appearance is like a crustacean. | |||

| *In '']'' (known outside the United States as ''SaGa 3''), intermediate boss Dahak is depicted as a multiple-headed lizard. | |||

| *In ''],'' the Prince of Persia flees from a powerful shadowy figure called The Dahaka. | |||

| *In ''],'' the buddy of the main antagonist is named Demonic Demise Dragon, Azi Dahaka. | |||

| *The ] '']'' issues feature an immortal villain named Zahhak, bound to two demonic snakes. Unless fed with other people's brains, they start eating his own. | |||

| *In the ] video game '']'', Ahzi Dahaka is a venerable dragon of the Earth element that is commonly encountered during the latter half of the game. | |||

| *In '']'', Azi Dahaka is an evil dragon who leads an antagonist group with another evil dragon named Apophis. | |||

| *In '']'', Equius Zahhak is the name of one of the '']'' | |||

| *In the light novel series '']'', Azi Dahaka is represented as a three-headed white dragon and is one of the main antagonists in the series. | |||

| *In the '']'' card game Azi Dahaka appear as a legendary Dragoncraft-class card come from Chronogenesis Expansion. | |||

| *In the '']'', Dahak is the god of chromatic dragons, and the son of the dragons Apsu and Tiamat. He seeks to kill his father and reign over all dragonkind. | |||

| *Aži Dahāka served as an inspiration for the boss Azhdaha ({{zh|若陀龙王}}) in '']'', a legendary dragon (Vishap) sealed underground by ]'s Geo Archon, Morax.<ref>{{Citation|title=The Birth of a Dragon: A Behind the Scenes Look At the Creation of Azhdaha {{!}} Genshin Impact| date=15 July 2021 |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fwOlW3ndDa8|language=en|access-date=2021-07-30}}</ref> | |||

| *In ], Aži Dahāka is one of the Divine Spirits infused into the Alter Ego-class Servant Grigori Rasputin, and appears in his Noble Phantasm Zazhiganiye Angra Mainyu. | |||

| *In ], Azi Dahaka, Lord of Evil Dragons is the Ultimate Skill of Vega. | |||

| *In the novelization of '']'', Zahhak is mentioned as a false god worshipped by an army of Persians that the Greeks defeated. | |||

| *The appearance of two snakes sprouting from the shoulders, and eating body parts, is strongly presented in the 2007 videogame The Darkness. | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| Khamenei Zahak a derogatory term used to nickname Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran, was a main anti Iranian regime chant during 2019-2022 protests of Iranian women where thousands were imprisoned. ] was put on a trial after crying "Khamenei Zahak we will take you in under the ground".<ref>https://ir.voanews.com/amp/sepideh-gholian--two-more-years-in-prison/7079426.html</ref><ref>https://www.bbc.com/persian/iran-66243572</ref> | |||

| ==Other dragons in Iranian tradition== | |||

| Zahhāk's tyranny over the world lasted for centuries. But one day Zahhāk had a terrible dream – he thought that three warriors were attacking him, and that the youngest knocked him down with his mace, tied him up, and dragged him off toward a tall mountain. When Zahhāk woke he was in a panic. Following the counsel of Arnavāz, he summoned wise men and dream-readers to explain his dream. They were reluctant to say anything, but one finally said that it was a vision of the end of Zahhāk's reign, that rebels would arise and dispossess Zahhāk of his throne. He even named the man who would take Zahhāk's place: ]. | |||

| Besides Aži Dahāka, several other dragons and dragon-like creatures are mentioned in Zoroastrian scripture: | |||

| * ''Aži Sruvara'' - the 'horned dragon' | |||

| *''Aži Zairita'' - the 'yellow dragon,' that is killed by the hero ], Middle Persian Kirsāsp.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Zamyād Yasht, Yasht 19 of the Younger Avesta (Yasht 19.19)|publisher=Wiesbaden |translator1=Helmut Humbach |translator2=Pallan Ichaporia|year=1998}}</ref> (''Yasna'' 9.1, 9.30; ''Yasht'' 19.19) | |||

| * ''Aži Raoiδita'' - the 'red dragon' conceived by ]'s to bring about the <nowiki>'</nowiki>'']''-induced winter' that is the reaction to ]'s creation of the '']''.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Zend-Avesta, The Vendidad|publisher=Greenwood Publish Group|translator=James Darmesteter|year=1972|isbn=0837130700|series=The Sacred Books of the East Series|volume=1}}</ref> (''Vendidad'' 1.2) | |||

| * ''Aži Višāpa'' - the 'dragon of poisonous slaver' that consumes offerings to ] if they are made between sunset and sunrise (''Nirangistan'' 48). | |||

| * ''Gandarəβa'' - the 'yellow-heeled' monster of the sea 'Vourukasha' that can swallow twelve provinces at once. On emerging to destroy the entire creation of ''Asha'', it too is slain by the hero ]. (''Yasht'' 5.38, 15.28, 19.41) | |||

| ==The Aži/Ahi in Indo-Iranian tradition== | |||

| Zahhāk now became obsessed with finding this "Fereydun" and destroying him, though he did not know where he lived or who his family was. His spies went everywhere looking for Fereydun, and finally heard that he was but a boy, being nourished on the milk of the marvelous cow Barmāyeh. The spies traced Barmāyeh to the highland meadows where it grazed, but Fereydun had already fled before them. They killed the cow, but had to return to Zahhāk with their mission unfulfilled. | |||

| {{see also|Proto-Indo-European religion}} | |||

| Stories of monstrous serpents who are killed or imprisoned by heroes or divine beings may date back to prehistory and are found in the ] of many Indo-European peoples, including those of the Indo-Iranians, that is, the common ancestors of both the Iranians and ]. | |||

| The most obvious point of comparison is that in ] ''ahi'' is a cognate of ] ''aži''. However, In Vedic tradition, the only dragon of importance is ], but "there is no Iranian tradition of a dragon such as Indian Vrtra" (Boyce, 1975:91-92). Moreover, while Iranian tradition has numerous dragons, all of which are malevolent, Vedic tradition has only one other dragon besides {{IAST|Vṛtra}} - ''ahi budhnya'', the benevolent "dragon of the deep". In the Vedas, gods battle dragons, but in Iranian tradition, this is a function of mortal heroes. | |||

| ===The Revolution against Zahhāk=== | |||

| Zahhāk now tried to consolidate his rule by coercing an assembly of the leading men of the kingdom into signing a document testifying to Zahhāk's righteousness, so that no one could have any excuse for rebellion. One man spoke out against this charade, a blacksmith named ]. Before the whole assembly, Kāva told how Zahhāk's minions had murdered seventeen of his eighteen sons so that Zahhāk might feed his snakes' lust for human brains – the last son had been imprisoned, but still lived. | |||

| Thus, although it seems clear that dragon-slaying heroes (and gods<!-- don't use "deva" here. Its confusing in an Iranian context --> in the case of the Vedas) "were a part of Indo-Iranian tradition and folklore, it is also apparent that Iran and India developed distinct myths early." (Skjaervø, 1989:192) | |||

| In front of the assembly Zahhāk had to pretend to be merciful, and so released Kāva's son. But when he tried to get Kāva to sign the document attesting to Zahhāk's justice, Kāva tore up the document, left the court, and raised his blacksmith's apron as a standard of rebellion – the ], ''derafsh-e Kāviyānī'' (درفش کاویانی). He proclaimed himself in support of Fereydun as ruler. | |||

| == Adaptations == | |||

| Soon many people followed Kāva to the Alborz mountains, where Fereydun was now living. He was now a young man and agreed to lead the people against Zahhāk. He had a mace made for him with a head like that of an ox, and with his brothers and followers, went forth to fight against Zahhāk. Zahhāk had already left his capital, and it fell to Fereydun with small resistance. Fereydun freed all of Zahhāk's prisoners, including Arnavāz and Shahrnavāz. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == See also == | |||

| Kondrow, Zahhāk's treasurer, pretended to submit to Fereydun, but when he had a chance he escaped to Zahhāk and told him what had happened. Zahhāk at first dismissed the matter, but when he heard that Fereydun had seated Jamshid's daughters on thrones beside him like his queens, he was incensed and immediately hastened back to his city to attack Fereydun. | |||

| * ], identified as ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| When he got there, Zahhāk found his capital held strongly against him, and his army was in peril from the defense of the city. Seeing that he could not reduce the city, he sneaked into his own palace as a spy, and attempted to assassinate Arnavāz and Shahrnavāz. Fereydun struck Zahhāk down with his ox-headed mace, but did not kill him; on the advice of an angel, he bound Zahhāk and imprisoned him in a cave underneath ], binding him with chains tied to great nails fixed into the walls of the cavern, where he will remain until the end of the world. Thus, after a thousand years' tyranny, ended the reign of Zahhāk. | |||

| {{ |

{{Reflist}} | ||

| ==Bibliography== | |||

| * {{cite book |year=1975 |author=Boyce, Mary |title=History of Zoroastrianism, Vol. I |location=Leiden |publisher=Brill}} | |||

| * Ingersoll, Ernest, et al., (2013). ''The Illustrated Book of Dragons and Dragon Lore''. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN B00D959PJ0 | |||

| * {{cite encyclopedia |volume=3 |year=1989 |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia Iranica |location=New York |publisher=Routledge & Kegan Paul |title=Aždahā: in Old and Middle Iranian |author=Skjærvø, P. O |pages=191–199 |url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/azdaha-dragon-various-kinds#pt1}} | |||

| * {{cite encyclopedia |volume=3 |year=1989 |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia Iranica |location=New York |publisher=Routledge & Kegan Paul |title=Aždahā: in Persian Literature |author=Khaleghi-Motlagh, DJ |pages=199–203 |url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/azdaha-dragon-various-kinds#pt2}} | |||

| * {{cite encyclopedia |volume=3 |year=1989 |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia Iranica |location=New York |publisher=Routledge & Kegan Paul |title=Aždahā: in Iranian Folktales |author=Omidsalar, M |pages=203–204 |url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/azdaha-dragon-various-kinds#pt3}} | |||

| * {{cite encyclopedia |volume=3 |year=1989 |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia Iranica |location=New York |publisher=Routledge & Kegan Paul |title=Aždahā: Armenian Aždahak |author=Russell, J. R |pages=204–205 |url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/azdaha-dragon-various-kinds#pt4}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * Schwartz, Martin. "Transformations of the Indo-Iranian Snake-man: Myth, Language, Ethnoarcheology, and Iranian Identity." Iranian Studies 45, no. 2 (2012): 275-79. www.jstor.org/stable/44860985. | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Commons category|Zahhak}} | |||

| * | |||

| *, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Zahhak | |||

| {{start |

{{s-start}} | ||

| {{succession box| | {{succession box| | ||

| before=] | | before=] | | ||

| title=Legendary Kings of the ] | | title=Legendary Kings of the ] | | ||

| years=''' |

years='''800–1800 (after ])'''| | ||

| after=]| | after=]| | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{end |

{{s-end}} | ||

| {{Shahnameh}} | |||

| == Aži Dahāka in popular culture == | |||

| *In the ] video-game series from Ubisoft, the Dahaka appears as the monstrous guardian of chronal continuity, hunting down and killing anomalies in the timeline of history. | |||

| *In Suikoden V, there is a massive ship named Dahak--given its 3 dragon figureheads, it's likely a reference to Azhi Dahaka. There is also a Queen's Knight named Zahhak. | |||

| *In Ogre Battle 64: Person of Lordly Caliber for the Nintendo 64, the Azhi Dahaka is the green, scaley final form of the "earth" elemental dragons in the game. | |||

| *In the role playing game ], certain members of the ] clan strive to become like Azhi Dahaka. | |||

| *In the TV series ] and ], the evil deity ] is based on Azhi Dahaka. | |||

| *He also appears on Lionheart: Legacy of the Crusader (game by Interplay,2003) as a guardian of his lair in the Fortress at Alamut. | |||

| *In the PlayStation 2 video game ], three fiends called Azi Dahaka guard the direct routes to Vegnagun. | |||

| *In his Empire from Ashes-trilogy, David Weber wrote of an immense sentient starship by the name of Dahak, whose crest was a three-headed dragon. | |||

| *In the third book of the roleplaying series "Blood Sword", the player will face three simulacrums of ancient gods. Azidahaka was described as a serpentine creature with three human heads. | |||

| *One of the most well known monsters in the ] series, ], seems to be based on Ahzi Dahaka. Both are three headed dragons, and King Ghidorah is sometimes referred to as "The King of Terror." | |||

| *In the Korean RPG game The War of Genesis III, a section of the protagonists ride flying dragons with large repeating guns mounted on their undersides. These flying creatures are referred to as Azhi Dahaka. The image is somewhat similar to a pterodactyl in the game, and it is referred to as being "extremely difficult to control." | |||

| *The Azhi Dahaka are also a fictional race of immortals featured in "The Everlasting", a series of Role Playing Game books published originally by Visionary Entertainment. In this context, the name refers to a supernatural creature that has stolen and consumed the soul of at least one dragon. | |||

| *Azhi Dahaka is a class of Dragon in the game ]. | |||

| ==Place names== | |||

| "Zahak Citadel" is the name of an ancient ruin in ], ] which according to various experts, was inhabited from the second millenia BC until the Timurid era. First excavated in the 1800s by British archeologists, ] has been studying the structure in 6 phases. | |||

| == See also == | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| ''Encyclopaedia Iranica'', article '''Aždahā''', pp. 191-205 | |||

| ==External link== | |||

| * | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 10:07, 5 December 2024

Evil figure in Iranian mythologyFor the Homestuck character, see Equius Zahhak."Zahak" redirects here. For the city in southeastern Iran, see Zehak. For the village in Hormozgan Province, see Zahak-e Pain.| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Zahhak" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Misplaced Pages's multilingual support templates may also be used. See why. (January 2024) |

| ShahZahhakA king of Iranian myths and legends | |

|---|---|

Zahhak in the Shahnameh Zahhak in the Shahnameh | |

| Other names | Azhi DahākaBēvar Asp |

| Spouse | ArnavazShahrnaz |

| Father | Mardas |

Zahhāk or Zahāk (pronounced [zæhɒːk]) (Persian: ضحّاک), also known as Zahhak the Snake Shoulder (Persian: ضحاک ماردوش, romanized: Zahhāk-e Mārdoush), is an evil figure in Persian mythology, evident in ancient Persian folklore as Azhi Dahāka (Persian: اژی دهاک), the name by which he also appears in the texts of the Avesta. In Middle Persian he is called Dahāg (Persian: دهاگ) or Bēvar Asp (Persian: بیور اسپ) the latter meaning "he who has 10,000 horses". In Zoroastrianism, Zahhak (going under the name Aži Dahāka) is considered the son of Ahriman, the foe of Ahura Mazda. In the Shāhnāmeh of Ferdowsi, Zahhāk is the son of a ruler named Merdās.

Etymology and derived words

Aži (nominative ažiš) is the Avestan word for "serpent" or "dragon". It is cognate to the Vedic Sanskrit word ahi, "snake", and without a sinister implication.

The original meaning of dahāka is uncertain. Among the meanings suggested are "stinging" (source uncertain), "burning" (cf. Sanskrit dahana), "man" or "manlike" (cf. Khotanese daha), "huge" or "foreign" (cf. the Dahae people and the Vedic dasas). In Persian mythology, Dahāka is treated as a proper noun, while the form Zahhāk, which appears in the Shāhnāme, was created through the influence of the unrelated Arabic word ḍaḥḥāk (ضَحَّاك) meaning "one who laughs".

The Avestan term Aži Dahāka and the Middle Persian aždahāg are the source of the Middle Persian Manichaean demon of greed Až, Old Armenian mythological figure Aždahak, Modern Persian 'aždehâ/aždahâ', (اژدها) Tajik Persian 'aždaho', (аждаҳо) Urdu 'aždahā' (اژدہا), as well as the Kurdish ejdîha (ئەژدیها) which usually mean "dragon".

The name also migrated to Eastern Europe, assumed the form "ažhdaja" and the meaning "dragon", "dragoness" or "water snake" in Balkanic and Slavic languages.

Despite the negative aspect of Aži Dahāka in mythology, dragons have been used on some banners of war throughout the history of Iranian peoples.

The Ažhdarchid group of pterosaurs are named from a Persian word for "dragon" that ultimately comes from Aži Dahāka.

Aži Dahāka (Dahāg) in Zoroastrian literature

Aži Dahāka is the most significant and long-lasting of the ažis of the Avesta, the earliest religious texts of Zoroastrianism. He is described as a monster with three mouths, six eyes, and three heads, cunning, strong, and demonic. In other respects Aži Dahāka has human qualities, and is never a mere animal.

Aži Dahāka appears in several of the Avestan myths and is mentioned parenthetically in many more places in Zoroastrian literature.

In a post-Avestan Zoroastrian text, the Dēnkard, Aži Dahāka is possessed of all possible sins and evil counsels, the opposite of the good king Jam (or Jamshid). The name Dahāg (Dahāka) is punningly interpreted as meaning "having ten (dah) sins". His mother is Wadag (or Ōdag), herself described as a great sinner, who committed incest with her son.

In the Avesta, Aži Dahāka is said to have lived in the inaccessible fortress of Kuuirinta in the land of Baβri, where he worshipped the yazatas Arədvī Sūrā (Anāhitā), divinity of the rivers, and Vayu divinity of the storm-wind. Based on the similarity between Baβri and Old Persian Bābiru (Babylon), later Zoroastrians localized Aži Dahāka in Mesopotamia, though the identification is open to doubt. Aži Dahāka asked these two yazatas for power to depopulate the world. Being representatives of the Good, they refused.

In one Avestan text, Aži Dahāka has a brother named Spitiyura. Together they attack the hero Yima (Jamshid) and cut him in half with a saw, but are then beaten back by the yazata Ātar, the divine spirit of fire.

According to the post-Avestan texts, following the death of Jam ī Xšēd (Jamshid), Dahāg gained kingly rule. Another late Zoroastrian text, the Mēnog ī xrad, says this was ultimately good, because if Dahāg had not become king, the rule would have been taken by the immortal demon Xešm (Aēšma), and so evil would have ruled upon the earth until the end of the world.

Dahāg is said to have ruled for a thousand years, starting from 100 years after Jam lost his Khvarenah, his royal glory (see Jamshid). He is described as a sorcerer who ruled with the aid of demons, the daevas (divs).

The Avesta identifies the person who finally disposed of Aži Dahāka as Θraētaona son of Aθβiya, in Middle Persian called Frēdōn. The Avesta has little to say about the nature of Θraētaona's defeat of Aži Dahāka, other than that it enabled him to liberate Arənavāci and Savaŋhavāci, the two most beautiful women in the world. Later sources, especially the Dēnkard, provide more detail. Feyredon is said to have been endowed with the divine radiance of kings (Khvarenah, New Persian farr) for life, and was able to defeat Dahāg, striking him with a mace. However, when he did so, vermin (snakes, insects and the like) emerged from the wounds, and the god Ormazd told him not to kill Dahāg, lest the world become infected with these creatures. Instead, Frēdōn chained Dahāg up and imprisoned him on the mythical Mt. Damāvand (later identified with Damāvand).

The Middle Persian sources also prophesy that at the end of the world, Dahāg will at last burst his bonds and ravage the world, consuming one in three humans and livestock. Kirsāsp, the ancient hero who had killed the Az ī Srūwar, returns to life to kill Dahāg.

Zahhak in the Shahname

In Ferdowsi's epic poem, the Shāhnāmah, written c. 1000 AD and part of Iranian folklore, the legend is retold with the main character given the name of Zahhāk and changed from a supernatural monster into an evil human being.

Zahhak in Persia

According to Ferdowsi, Zahhāk was born as the son of a ruler named Merdās (Persian: مرداس). Because of his Arab lineage, he is sometimes called Zahhāk-e Tāzī (Persian: ضحاکِ تازی), meaning "Zahhāk the Tayyi". He is handsome and clever, but has no stability of character and is easily influenced by his counselors. Ahriman therefore chooses him as a tool to sow disorder and chaos. When Zahhāk is a young man, Ahriman first appears to him as a glib, flattering companion, and by degrees convinces him to kill his own father and inherit his kingdom, treasures and army. Zahhāk digs a deep pit covered over with leaves in a path to a garden where Merdās would pray each morning; Merdās falls in and is killed. Zahhāk thus ascends to the throne.

Ahriman then presents himself to Zahhāk as a marvelous cook. After he presents Zahhāk with many days of sumptuous feasts (introducing meat to the formerly vegetarian human cuisine), Zahhāk is willing to give Ahriman whatever he wants. Ahriman merely asks to kiss Zahhāk on his two shoulders, and Zahhāk permits this. Ahriman places his lips upon Zahhāk's shoulders and suddenly disappears. At once, two black snakes grow from Zahhāk's shoulders. They cannot be surgically removed, as another snake grows to replace one that has been severed. Ahriman appears to Zahhāk in the form of a skilled physician. He counsels Zahhāk that attempting to remove the snakes is fruitless, and that the only means of soothing the snakes and preventing them from killing him is to sate their hunger by supplying them with a stew made from two human brains every day.

Zahhāk the Emperor

At this time, Jamshid, the ruler of the world, becomes arrogant and loses his divine right to rule. Zahhāk presents himself as a savior to discontented Iranians seeking a new ruler. Collecting a great army, Zahhāk hunts Jamshid for many years before finally capturing him. Zahhāk executes Jamshid by sawing him in half and ascends to Jamshid's prior throne. Among his slaves are two of Jamshid's daughters, Arnavāz and Shahrnāz (the Avestan Arənavāci and Savaŋhavāci). Each day, Zahhāk's agents seize two men and execute them so that their brains can feed Zahhāk's snakes. Two men, called Armayel and Garmayel, seek to rescue people from being killed from the snakes by learning cookery and becoming Zahhāk's royal chefs. Each day, Armayel and Garmayel save one of the two men by sending him off to the mountains and faraway plains, and substitute the man's brain with that of a sheep. The saved men are the mythological progenitors of the Kurds.

Zahhāk's tyranny over the world lasts for centuries. One night, Zahhāk dreams of three warriors attacking him. The youngest warrior knocks Zahhāk down with his mace, ties him up, and drags him off toward Mount Damāvand as a large crowd follows. Zahhāk wakes and shouts so loudly that the pillars of the palace shake. Following Arnavāz's counsel, Zahhāk summons wise men and scholars to interpret his dream. His hesitant counsellors remain silent until the most fearless of the men reports that the dream is a vision of the end of Zahhāk's reign at the hands of Fereydun, the young man with the mace. Zahhāk is thrilled to learn the identity of his enemy, and orders his agents to search the entire country for Fereydun and capture him. The agents learn that Fereydun is a boy being nourished on the milk of the marvelous cow Barmāyeh. The spies trace Barmāyeh to the highland meadows where it grazes, but Fereydun and his mother have already fled before them. The agents kill the cow, but are forced to return to Zahhāk with their mission unfulfilled.

Revolution against Zahhāk

Zahhāk lives the next few years in fear and anxiety of Fereydun, and thus writes a document testifying to the virtue and righteousness of his kingdom that would be certified by the kingdom's elders and social elite, in the hope that his enemy would be convinced against exacting vengeance. Much of the summoned assembly indulge the testimony out of fear for their lives. However, a blacksmith named Kāva (Kaveh) speaks out in anger for his children having been murdered to feed Zahhāk's snakes, and for his final remaining son being sentenced to the same fate. Zahhāk orders for Kāva's son to be released in a bid to coerce Kāva into certifying the document, but Kāva tears up the document, leaves the court, and creates a flag out of his blacksmith's apron as a standard of rebellion – the Kāviyāni Banner, derafsh-e Kāviyānī (درفش کاویانی). Kāva proclaims himself in support of Fereydun as ruler, and rallies a crowd to follow him to the Alborz mountains, where Fereydun is now living as a young man. Fereydun agrees to lead the people against Zahhāk and has a mace made for him with a head like that of an ox.

Fereydun goes forth to fight against Zahhāk, who has already left his capital, which falls to Fereydun with small resistance. Fereydun frees all of Zahhāk's prisoners, including Arnavāz and Shahrnāz. Kondrow, Zahhāk's treasurer, pretends to submit to Fereydun, but discreetly escapes to Zahhāk and reports to him what has happened. Zahhāk initially dismisses the matter, but he is incensed to learn that Fereydun has seated Jamshid's daughters on thrones beside him like his queens, and immediately hastens back to his city to attack Fereydun. Zahhāk finds his capital held strongly against him, and his army is in peril from the defense of the city. Seeing that he cannot reduce the city, he sneaks into his own palace as a spy and attempts to assassinate Arnavāz and Shahrnāz. Fereydun strikes Zahhāk down with his ox-headed mace, but does not kill him; on the advice of an angel, he binds Zahhāk and imprisons him in a cave underneath Mount Damāvand. Fereydun binds Zahhāk with a lion's pelt tied to great nails fixed into the walls of the cavern, where Zahhāk will remain until the end of the world.

Place names

"Zahhak Castle" is the name of an ancient ruin in Hashtrud, East Azerbaijan Province, Iran which according to various experts, was inhabited from the second millennia BC until the Timurid-era. First excavated in the 19th century by British archeologists, Iran's Cultural Heritage Organization has been studying the structure in 6 phases.

In popular culture

- The tale of Zahhak's defeat of Jamshid and subsequent defeat to Fereydun serves as the backstory of the 1992 Sega Game Gear video game Defenders of Oasis. A descendant of Zahhak is a major antagonist in the game's plot.

- In the Xenaverse, Zahhak (referred to as Dahak) is the supernatural adversary whom both Xena and later Hercules on Hercules: The Legendary Journeys must defeat in order to save the world from utter destruction. When Dahak appears on Hercules, his appearance is like a crustacean.

- In Final Fantasy Legend III (known outside the United States as SaGa 3), intermediate boss Dahak is depicted as a multiple-headed lizard.

- In Prince of Persia: Warrior Within, the Prince of Persia flees from a powerful shadowy figure called The Dahaka.

- In Future Card Buddyfight, the buddy of the main antagonist is named Demonic Demise Dragon, Azi Dahaka.

- The Marvel MAX Terror Inc. issues feature an immortal villain named Zahhak, bound to two demonic snakes. Unless fed with other people's brains, they start eating his own.

- In the Quest Corporation video game Ogre Battle 64: Person of Lordly Caliber, Ahzi Dahaka is a venerable dragon of the Earth element that is commonly encountered during the latter half of the game.

- In High School DxD, Azi Dahaka is an evil dragon who leads an antagonist group with another evil dragon named Apophis.

- In Homestuck, Equius Zahhak is the name of one of the Trolls

- In the light novel series Problem Children Are Coming from Another World, Aren't They?, Azi Dahaka is represented as a three-headed white dragon and is one of the main antagonists in the series.

- In the Shadowverse card game Azi Dahaka appear as a legendary Dragoncraft-class card come from Chronogenesis Expansion.

- In the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game, Dahak is the god of chromatic dragons, and the son of the dragons Apsu and Tiamat. He seeks to kill his father and reign over all dragonkind.

- Aži Dahāka served as an inspiration for the boss Azhdaha (Chinese: 若陀龙王) in Genshin Impact, a legendary dragon (Vishap) sealed underground by Liyue's Geo Archon, Morax.

- In Fate/Grand Order, Aži Dahāka is one of the Divine Spirits infused into the Alter Ego-class Servant Grigori Rasputin, and appears in his Noble Phantasm Zazhiganiye Angra Mainyu.

- In That Time I Got Reincarnated as a Slime, Azi Dahaka, Lord of Evil Dragons is the Ultimate Skill of Vega.

- In the novelization of God of War II, Zahhak is mentioned as a false god worshipped by an army of Persians that the Greeks defeated.

- The appearance of two snakes sprouting from the shoulders, and eating body parts, is strongly presented in the 2007 videogame The Darkness.

Legacy

Khamenei Zahak a derogatory term used to nickname Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran, was a main anti Iranian regime chant during 2019-2022 protests of Iranian women where thousands were imprisoned. Sepideh Qolian was put on a trial after crying "Khamenei Zahak we will take you in under the ground".

Other dragons in Iranian tradition

Besides Aži Dahāka, several other dragons and dragon-like creatures are mentioned in Zoroastrian scripture:

- Aži Sruvara - the 'horned dragon'

- Aži Zairita - the 'yellow dragon,' that is killed by the hero Kərəsāspa, Middle Persian Kirsāsp. (Yasna 9.1, 9.30; Yasht 19.19)

- Aži Raoiδita - the 'red dragon' conceived by Angra Mainyu's to bring about the 'daeva-induced winter' that is the reaction to Ahura Mazda's creation of the Airyanem Vaejah. (Vendidad 1.2)

- Aži Višāpa - the 'dragon of poisonous slaver' that consumes offerings to Aban if they are made between sunset and sunrise (Nirangistan 48).

- Gandarəβa - the 'yellow-heeled' monster of the sea 'Vourukasha' that can swallow twelve provinces at once. On emerging to destroy the entire creation of Asha, it too is slain by the hero Kərəsāspa. (Yasht 5.38, 15.28, 19.41)

The Aži/Ahi in Indo-Iranian tradition

See also: Proto-Indo-European religionStories of monstrous serpents who are killed or imprisoned by heroes or divine beings may date back to prehistory and are found in the myths of many Indo-European peoples, including those of the Indo-Iranians, that is, the common ancestors of both the Iranians and Vedic Indians.

The most obvious point of comparison is that in Vedic Sanskrit ahi is a cognate of Avestan aži. However, In Vedic tradition, the only dragon of importance is Vrtra, but "there is no Iranian tradition of a dragon such as Indian Vrtra" (Boyce, 1975:91-92). Moreover, while Iranian tradition has numerous dragons, all of which are malevolent, Vedic tradition has only one other dragon besides Vṛtra - ahi budhnya, the benevolent "dragon of the deep". In the Vedas, gods battle dragons, but in Iranian tradition, this is a function of mortal heroes.

Thus, although it seems clear that dragon-slaying heroes (and gods in the case of the Vedas) "were a part of Indo-Iranian tradition and folklore, it is also apparent that Iran and India developed distinct myths early." (Skjaervø, 1989:192)

Adaptations

See also

References

- Gholizadeh, Khosro (1970-01-01). "zahāk or wolflike serpent in the Persian and kurdish Mythology | khosro gholizadeh". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- loghatnaameh.com. "ضحاک بیوراسب | پارسی ویکی". Loghatnaameh.org. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- Bane, Theresa (2012). Encyclopedia of Demons in World Religions and Cultures. McFarland. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-7864-8894-0. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- کجا بیوراسپش همی خواندند / چُنین نام بر پهلوی راندند

کجا بیور از پهلوانی شمار / بود بر زبان دری دههزار - "Characters of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh". heritageinstitute.com. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- "Persia: iv. Myths an Legends". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- For Azi Dahaka as dragon see: Ingersoll, Ernest, et al., (2013). The Illustrated Book of Dragons and Dragon Lore. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN B00D959PJ0

- Appears numerous time in, for example: D. N. MacKenzie, Mani’s Šābuhragān, pt. 1 (text and translation), BSOAS 42/3, 1979, pp. 500-34, pt. 2 (glossary and plates), BSOAS 43/2, 1980, pp. 288-310.

- Detelić, Mirjana. "St Paraskeve in the Balkan Context" In: Folklore 121, no. 1 (2010): 101 (footnote nr. 12). Accessed March 24, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29534110.

- Erben, Karel Jaromír; Strickland, Walter William. Russian and Bulgarian folk-lore stories. London: G. Standring. 1907. p. 130.

- Kropej, Monika. Supernatural beings from Slovenian myth and folktales. Ljubljana: Institute of Slovenian Ethnology at ZRC SAZU. 2012. p. 102. ISBN 978-961-254-428-7

- Kappler, Matthias. Turkish Language Contacts in Southeastern Europe. Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press, 2010. p. 256. https://doi.org/10.31826/9781463225612

- "Bowl Depicting King Zahhak with Snakes Protruding from His Shoulders". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2024-04-24.

- Masudi. Les Prairies d’Or. Trans. Barbier de Meynard and Pavet de Courteille, 9 vols. Paris: La Société Asiatique, 1861.

- Özoglu, H. (2004). Kurdish Notables and the Ottoman State: Evolving Identities, Competing Loyalties, and Shifting Boundaries. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 30.

- قلعهزهاك 30 قرن مسكوني بود [Castle inhabited 30 centuries] (in Persian). Cultural Heritage News Agency. 2007-03-04. Archived from the original on 2006-10-01. Retrieved 2006-05-28.

- The Birth of a Dragon: A Behind the Scenes Look At the Creation of Azhdaha | Genshin Impact, 15 July 2021, retrieved 2021-07-30

- https://ir.voanews.com/amp/sepideh-gholian--two-more-years-in-prison/7079426.html

- https://www.bbc.com/persian/iran-66243572

- Zamyād Yasht, Yasht 19 of the Younger Avesta (Yasht 19.19). Translated by Helmut Humbach; Pallan Ichaporia. Wiesbaden. 1998.

- The Zend-Avesta, The Vendidad. The Sacred Books of the East Series. Vol. 1. Translated by James Darmesteter. Greenwood Publish Group. 1972. ISBN 0837130700.

Bibliography

- Boyce, Mary (1975). History of Zoroastrianism, Vol. I. Leiden: Brill.

- Ingersoll, Ernest, et al., (2013). The Illustrated Book of Dragons and Dragon Lore. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN B00D959PJ0

- Skjærvø, P. O (1989). "Aždahā: in Old and Middle Iranian". Encyclopedia Iranica. Vol. 3. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 191–199.

- Khaleghi-Motlagh, DJ (1989). "Aždahā: in Persian Literature". Encyclopedia Iranica. Vol. 3. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 199–203.

- Omidsalar, M (1989). "Aždahā: in Iranian Folktales". Encyclopedia Iranica. Vol. 3. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 203–204.

- Russell, J. R (1989). "Aždahā: Armenian Aždahak". Encyclopedia Iranica. Vol. 3. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 204–205.

Further reading

- Schwartz, Martin. "Transformations of the Indo-Iranian Snake-man: Myth, Language, Ethnoarcheology, and Iranian Identity." Iranian Studies 45, no. 2 (2012): 275-79. www.jstor.org/stable/44860985.

External links

- Discussion of Az at Encyclopedia Iranica

- A king's book of kings: the Shah-nameh of Shah Tahmasp, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Zahhak

| Preceded byJamshid | Legendary Kings of the Shāhnāma 800–1800 (after Keyumars) |

Succeeded byFereydun |

| Shahnameh of Ferdowsi | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characters |    | |

| Creatures and animals |

| |

| Places | ||

| Structures |

| |

| Manuscripts | ||

| Related | ||