| Revision as of 16:15, 23 August 2006 editEdipedia (talk | contribs)565 edits see discussion← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:50, 7 January 2025 edit undo36.37.153.118 (talk)No edit summaryTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Ethnic Chinese residing outside of China}} | |||

| '''Overseas Chinese''' (海外華人, 華僑 in ]: Huáqiáo, or 華胞 huábāo, or 僑胞 qiáobāo, or 華裔 huáyì) are ] who live outside ]. China, in this usage, usually refer to what is sometimes called "]", including territory currently administered by the rival governments of the ] (PRC) and the ] (ROC) as per traditional definitions of the term prior to the ], or only to the People's Republic of China by some. In addition, the government of the ] granted residents of ] and ] "overseas Chinese status" prior to their respective handover to ] rule, so the definition may be said to loosely extend to them. | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2020}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=March 2015}} | |||

| {{Infobox ethnic group | |||

| | native_name = {{ubl|{{lang|zh-hant|海外華人}},{{lang|zh-hans|海外华人}}|{{lang|zh-hant|海外中國人}},{{lang|zh-hans|海外中国人}}}} | |||

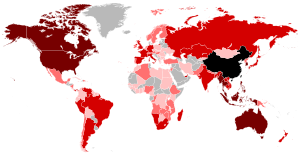

| | image = ] | |||

| | population = 60,000,000<ref>{{Cite web |last=Zhuang |first=Guotu |year=2021 |title=The Overseas Chinese: A Long History |url=https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379264_eng |publisher=UNESDOC |page=24}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Suryadinata |first=Leo |year=2017 |title=Blurring the Distinction between Huaqiao and Huaren: China's Changing Policy towards the Chinese Overseas |url=https://muse.jhu.edu/article/658015/pdf |url-status=live |journal=Southeast Asian Affairs |location=Singapore |publisher=] |volume=2017 |issue=1 |page=109 |jstor=pdf/26492596.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ac19f5fdd9d010b9985b476a20a2a8bdd |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210128232425/https://muse.jhu.edu/article/658015/pdf |archive-date=28 January 2021 |access-date=20 February 2020}}</ref> | |||

| | region1 = {{flag|Thailand}} | |||

| | pop1 = ] (2012) | |||

| | ref1 = <ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.culturaldiplomacy.org/academy/index.php?chinese-diaspora|title=Chinese Diaspora|access-date=2022-04-01|archive-date=27 September 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210927053139/https://www.culturaldiplomacy.org/academy/index.php?chinese-diaspora|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | region2 = {{flag|Malaysia}} | |||

| | pop2 = ] (2020) | |||

| | ref2 = <ref name="DOSM2020">{{Cite journal |date=Dec 2022 |title=Key Findings of Population and Housing Census of Malaysia 2020: Urban and Rural |journal=] |pages=273–355 |isbn=978-967-253-683-3}}</ref> | |||

| | region3 = {{flag|United States}} | |||

| | pop3 = ] (2023) | |||

| | ref3 = <ref name="ACS 2023">{{cite web |url=https://data.census.gov/table/ACSDT1Y2023.B02018 |publisher=U.S. Census Bureau |access-date=2024-09-21 |title=US Census Data }}</ref> | |||

| | region4 = {{flag|Indonesia}} | |||

| | pop4 = ] (2010) | |||

| | ref4 = <ref>{{cite web|url=https://media.neliti.com/media/publications/49956-ID-kewarganegaraan-suku-bangsa-agama-dan-bahasa-sehari-hari-penduduk-indonesia.pdf |language=Indonesian |publisher=Indonesian Census Bureau |access-date=2024-11-26|title=Indonesian Census Data }}</ref> | |||

| | region5 = {{flag|Singapore}} | |||

| | pop5 = ] (2020) | |||

| | ref5 = <ref>{{cite web |title=Census 2020 |url=https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/publications/cop2020/sr1/cop2020sr1.pdf |website=Singapore Department of Statistics |access-date=20 January 2023 |archive-date=11 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220611051404/https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/publications/cop2020/sr1/cop2020sr1.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | region6 = {{flag|Myanmar}} | |||

| | pop6 = ] (2011) | |||

| | ref6 = <ref name="Poston and Wong" /> | |||

| | region7 = {{flag|Canada}} | |||

| | pop7 = ] (2021) | |||

| | ref7 = <ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-12-15 |title=Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population – Canada – Visible minority |at=Chinese |url=https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?LANG=E&GENDERlist=1,2,3&STATISTIClist=1&DGUIDlist=2021A000011124&HEADERlist=30&SearchText=Canada |access-date=2023-01-08 |website=] |archive-date=8 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230108053001/https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?LANG=E&GENDERlist=1,2,3&STATISTIClist=1&DGUIDlist=2021A000011124&HEADERlist=30&SearchText=Canada |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | region8 = {{flag|Australia}} | |||

| | pop8 = ] (2021) | |||

| | ref8 = <ref>{{Cite web |title=2021 Australia, Census All persons QuickStats {{!}} Australian Bureau of Statistics |url=https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/AUS |access-date=2024-12-04 |website=www.abs.gov.au}}</ref> | |||

| | region9 = {{flag|Philippines}} | |||

| | pop9 = ] (2013) | |||

| | ref9 = <ref>{{Cite press release|title=Senate declares Chinese New Year as special working holiday|date=January 21, 2013|publisher=PRIB, Office of the Senate Secretary, Senate of the Philippines|url=http://www.senate.gov.ph/press_release/2013/0121_prib1.asp|last1=Macrohon|first1=Pilar|access-date=9 October 2015|archive-date=9 April 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160409034225/http://www.senate.gov.ph/press_release/2013/0121_prib1.asp|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | region10 = {{flag|South Korea}} | |||

| | pop10 = ] (2018) | |||

| | ref10 = <ref name="kr2018" /> | |||

| | region11 = {{flag|Vietnam}} | |||

| | pop11 = ] (2019) | |||

| | ref11 = <ref name="GSO2019"/> | |||

| | region12 = {{flag|Japan}} | |||

| | pop12 = ] (2022) | |||

| | ref12 = <ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/publications/press/13_00028.html |title=令和4年6月末現在における在留外国人数について | 出入国在留管理庁 |access-date=26 January 2023 |archive-date=1 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230101215618/https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/publications/press/13_00028.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | region13 = {{flag|United Kingdom}} | |||

| | pop13 = ] (2021) | |||

| | region14 = {{flag|France}} | |||

| | pop14 = ] (2011) | |||

| | ref14 = <ref name="Poston and Wong" /> | |||

| | region15 = {{flag|Italy}} | |||

| | pop15 = ] (2020) | |||

| | ref15 = <ref>]: '' {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141113203531/http://www.istat.it/it/archivio/129854 |date=November 13, 2014 }}''. Retrieved 5 January 2015.17</ref> | |||

| | region16 = {{flag|Brazil}} | |||

| | pop16 = ] (2011) | |||

| | ref16 = <ref name="Poston and Wong" /> | |||

| | region17 = {{flag|New Zealand}} | |||

| | pop17 = ] (2018) | |||

| | ref17 = <ref>{{Cite web|title=National ethnic population projections, by age and sex, 2018 (base) – 2043 Information on table.|access-date=31 October 2021|url=http://nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz/wbos/index.aspx|archive-date=1 December 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211201145406/http://nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz/wbos/Index.aspx|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | region18 = {{flag|Germany}} | |||

| | pop18 = ] (2023) | |||

| | ref18 = <ref>{{Cite web|url = https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/Publikationen/Downloads-Migration/statistischer-bericht-migrationshintergrund-erst-2010220227005.htmll|title = Statistischer Bericht – Mikrozensus – Bevölkerung nach Migrationshintergrund – Erstergebnisse 2022|date = 20 April 2023|access-date = 17 July 2023}}</ref> | |||

| | region19 = {{flag|India}} | |||

| | pop19 = ] (2023) | |||

| | ref19 = <ref name="Poston and Wong" /> | |||

| | region20 = {{flag|Laos}} | |||

| | pop20 = ] (2011) | |||

| | ref20 = <ref name="Poston and Wong" /> | |||

| | region21 = {{flag|Cambodia}} | |||

| | pop21 = ] (2013)<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.nis.gov.kh/nis/CSES/Final%20Report%20CSES%202013.pdf|title=Cambodia Socio-Economic Survey 2013|publisher=National Institute of Statistics, Ministry of Planning, Government of Cambodia|pages=12|date=July 2014|access-date=2024-11-24|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161113144749/http://www.nis.gov.kh/nis/CSES/Final%20Report%20CSES%202013.pdf|archive-date=2016-11-13|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| | languages = ] | |||

| | religions = {{hlist|]|]|]|]<ref name="More Islamic Chinnese">{{Cite book |chapter-url=https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315225159-2/islamic-less-chinese-explorations-overseas-chinese-muslim-identities-malaysia-chow-bing-ngeow-hailong-ma |chapter=More Islamic, no less Chinese: explorations into overseas Chinese Muslim identities in Malaysia|doi=10.4324/9781315225159-2 |title=Chinese Minorities at Home and Abroad |date=2018 |last1=Ngeow a |first1=Chow Bing |last2=Ma b |first2=Hailong |pages=30–50 |isbn=978-1-315-22515-9 |s2cid=239781552 }}</ref>|Other}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox Chinese | |||

| | t = 海外華人 | |||

| | s = 海外华人 | |||

| | p = Hǎiwài huárén | |||

| | t2 = 海外中國人 | |||

| | s2 = 海外中国人 | |||

| | p2 = Hǎiwài Zhōngguórén | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Overseas Chinese''' people are ] who reside outside ] (], ], ], and ]).<ref>{{cite web |last1=Goodkind |first1=Daniel |title=The Chinese Diaspora: Historical Legacies and Contemporary Trends |url=https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2019/demo/Chinese_Diaspora.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200220152138/https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2019/demo/Chinese_Diaspora.pdf |archive-date=2020-02-20 |url-status=live |publisher=U.S. Census Bureau |access-date=31 August 2021}}</ref> As of 2011, there were over 40.3 million overseas Chinese.<ref name="Poston and Wong">{{cite journal |last1=Poston |first1=Dudley |last2=Wong |first2=Juyin |date=2016 |title=The Chinese diaspora: The current distribution of the overseas Chinese population |url= |journal=Chinese Journal of Sociology |volume=2 |issue=3 |pages=356–360 |doi=10.1177/2057150X16655077 |s2cid=157718431 |access-date=}}</ref> Overall, China has a low percent of population ]. | |||

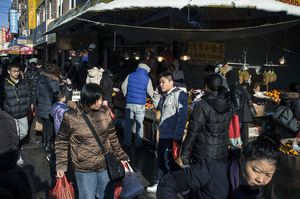

| ] in ], New York. Multiple Chinatowns in ], ], and Brooklyn are thriving as traditionally urban ], as large-scale ] continues into New York.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.dhs.gov/yearbook-immigration-statistics-2012-legal-permanent-residents|title=Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2012 Supplemental Table 2|publisher=U.S. Department of Homeland Security|access-date=2 May 2013|archive-date=3 April 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130403073333/http://www.dhs.gov/yearbook-immigration-statistics-2012-legal-permanent-residents|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.dhs.gov/files/statistics/publications/LPR11.shtm|title=Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2011 Supplemental Table 2|publisher=U.S. Department of Homeland Security|access-date=27 April 2013|archive-date=8 August 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120808080130/http://www.dhs.gov/files/statistics/publications/LPR11.shtm|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.dhs.gov/files/statistics/publications/LPR10.shtm|title=Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2010 Supplemental Table 2|publisher=U.S. Department of Homeland Security|access-date=27 April 2013|archive-date=12 July 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120712200141/https://www.dhs.gov/files/statistics/publications/LPR10.shtm|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://articles.nydailynews.com/2011-05-09/news/29541916_1_illegal-chinese-immigrants-qm2-queen-mary|title=Malaysian man smuggled illegal Chinese immigrants into Brooklyn using Queen Mary 2: authorities|author=John Marzulli|publisher=NY Daily News.com|date=9 May 2011|access-date=27 April 2013|location=New York|archive-date=5 May 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150505034445/http://www.nydailynews.com/news/world/malaysian-man-smuggled-illegal-chinese-immigrants-brooklyn-queen-mary-2-authorities-article-1.143516|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.queensbuzz.com/flushing-neighborhood-corona-neighborhood-cms-302|title=Chinese New Year 2012 in Flushing|publisher=QueensBuzz.com|date=25 January 2012|access-date=2 May 2013|archive-date=30 March 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130330075918/http://www.queensbuzz.com/flushing-neighborhood-corona-neighborhood-cms-302|url-status=live}}</ref> The ] contains the ] outside of ], comprising an estimated 893,697 uniracial individuals as of 2017.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/17_1YR/S0201/330M400US408/popgroup~016|title=Selected Population Profile in the United States 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates New York–Newark, NY-NJ-CT-PA CSA Chinese alone|publisher=]|access-date=27 January 2019|archive-url=https://archive.today/20200214002005/https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/17_1YR/S0201/330M400US408/popgroup~016|archive-date=14 February 2020|url-status=dead}}</ref>]] | |||

| ==Terminology== | ==Terminology== | ||

| '''{{zh|p = Huáqiáo|labels = no}}''' ({{zh|s=华侨|t=華僑}}) refers to people of Chinese citizenship residing outside of either the ] or ]. The government of China realized that the overseas Chinese could be an asset, a source of foreign investment and a bridge to overseas knowledge; thus, it began to recognize the use of the term Huaqiao.<ref name="wang">{{cite book|last=Wang|first=Gungwu|chapter=Upgrading the migrant: neither huaqiao nor huaren|year= 1994|publisher=Chinese Historical Society of America|title=Chinese America: History and Perspectives 1996|isbn=978-0-9614198-9-9|page=4|quote=In its own way, it has upgraded its migrants from a ragbag of malcontents, adventurers, and desperately poor laborers to the status of respectable and valued nationals whose loyalty was greatly appreciated.}}</ref> | |||

| Strictly speaking, there are two words in ] for overseas Chinese: huáqiáo (华侨 / 華僑) refers to overseas Chinese who were born in China, while huáyì (华裔 / 華裔) refers to any overseas Chinese with a Chinese ancestry. . | |||

| Ching-Sue Kuik renders {{lang|zh-Latn-pinyin|huáqiáo}} in English as "the Chinese ]" and writes that the term is "used to disseminate, reinforce, and perpetuate a monolithic and essentialist Chinese identity" by both the PRC and the ROC.<ref name="ChingSueKuik">{{cite thesis|last=Kuik|first=Ching-Sue (Gossamer)|year=2013|title=Un/Becoming Chinese: Huaqiao, The Non-perishable Sojourner Reinvented, and Alterity of Chineseness|degree=PhD|chapter=Introduction|page=2|publisher= ]|oclc=879349650|chapter-url=https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/bitstream/handle/1773/23534/Kuik_washington_0250E_12080.pdf|access-date=5 October 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201005190404/https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/bitstream/handle/1773/23534/Kuik_washington_0250E_12080.pdf|archive-date=5 October 2020}}</ref> | |||

| The modern informal internet term {{zh|p = ]|labels = no}} ({{zh|s=海归|t=海歸|labels=no}}) refers to returned overseas Chinese and ''guīqiáo qiáojuàn'' ({{zh|s=归侨侨眷|t=歸僑僑眷|labels=no}}) to their returning relatives.<ref name="Barabantseva">{{cite journal|title = Who Are 'Overseas Chinese Ethnic Minorities'? China's Search for Transnational Ethnic Unity |first=Elena|last=Barabantseva|journal=Modern China|year=2012|volume=31|issue=1|pages=78–109|doi = 10.1177/0097700411424565|s2cid=145221912}}</ref>{{Clarify|reason=Why are the 归侨侨眷 not themselves 海归?|date=August 2020}} | |||

| {{zh|p = Huáyì|labels = no}} ({{zh|s=华裔|t=華裔|labels=no}}) refers to people of Chinese descent or ] residing outside of China, regardless of citizenship.<ref name=pan>{{cite encyclopedia|editor1-last=Pan|editor1-first=Lynn|editor1-link=Lynn Pan|article=Huaqiao|encyclopedia=The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas|publisher=]|date= 1999|access-date=17 March 2009|isbn=0674252101|lccn=98035466|url=http://www.hup.harvard.edu/features/reference/panenc/huaqiao.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090317060519/http://www.hup.harvard.edu/features/reference/panenc/huaqiao.html|archive-date=17 March 2009}}</ref> Another often-used term is {{zh|t=海外華人|p=Hǎiwài Huárén|labels=no}} or simply {{zh|t=華人|p=Huárén|labels=no}}. It is often used by the ] to refer to people of Chinese ethnicities who live outside the PRC, regardless of citizenship (they can become citizens of the country outside China by naturalization). | |||

| Overseas Chinese who are ethnic ], such as ], ], ], ] or ] refer to themselves as {{zhi|c=唐人}} (Tángrén).{{efn|{{zh|j=tong4 jan4|poj=Tn̂g-lâng}}; ]: ''Toung ning''; ]: ''Tong nyin''}} Literally, it means ''Tang people'', a reference to ] China when it was ruling. This term is commonly used by the ], ], ] and ] as a colloquial reference to the Chinese people and has little relevance to the ancient dynasty. For example, in the early 1850s when Chinese shops opened on Sacramento St. in ], California, United States, the Chinese emigrants, mainly from the ] west of ], called it ''Tang People Street'' ({{zhi|c=唐人街}}){{efn|{{lang-zh|p=Tángrénjiē|j=tong4 jan4 gaai1}}}}<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hoy |first1=William J |title=Chinatown derives its own street names |journal=California Folklore Quarterly |volume=2 |year=1943 |issue=April |pages=71–75|doi=10.2307/1495551 |jstor=1495551}}</ref><ref name="yung2006" />{{rp|13}} and the settlement became known as ''Tang People Town'' ({{zhi|c=唐人埠}}){{efn|{{lang-zh|p=Tángrénbù|j=tong4 jan4 fau4}}}} or Chinatown.<ref name="yung2006">{{cite book |last1=Yung |first1=Judy and the Chinese Historical Society of America |title=San Francisco's Chinatown |date=2006 |publisher=Arcadia Publishing |isbn=978-07385-3130-4}}</ref>{{rp|9–40}} | |||

| The term '''{{zhi|p=shǎoshù mínzú}}''' ({{zhi|s=少数民族|t=少數民族}}) is added to the various terms for the overseas Chinese to indicate those who would be considered ]. The terms '''{{zhi|p=shǎoshù mínzú huáqiáo huárén}}''' and '''{{zhi|p=shǎoshù mínzú hǎiwài qiáobāo}}''' ({{zhi|s=少数民族海外侨胞|t=少數民族海外僑胞}}) are all in usage. The ] of the PRC does not distinguish between Han and ethnic minority populations for official policy purposes.<ref name="Barabantseva"/> For example, members of the ] may travel to China on passes granted to certain people of Chinese descent.<ref>{{cite book |title=Authenticating Tibet: Answers to China's 100 Questions|url=https://archive.org/details/authenticatingti00anne|url-access=registration|author1=Blondeau, Anne-Marie|author2=Buffetrille, Katia|author3=Wei Jing|publisher=]|year=2008|page=}}</ref> Various estimates of the Chinese emigrant minority population include 3.1 million (1993),<ref>{{cite journal|first=Biao|last=Xiang|year=2003|title=Emigration from China: a sending country perspective|journal=International Migration|volume=41|issue=3|pages=21–48|doi=10.1111/1468-2435.00240}}</ref> 3.4 million (2004),<ref>{{cite book|first=Heman|last=Zhao|year=2004|title=少數民族華僑華人研究|trans-title=A Study of Overseas Chinese Ethnic Minorities|location=Beijing|publisher=華僑出版社}}</ref> 5.7 million (2001, 2010),<ref>{{cite journal|last=Li|first=Anshan|year=2001|script-title=zh:'華人移民社群的移民身份與少數民族'研討會綜述|trans-title=Symposium on the Migrant Statuses of Chinese Migrant Communities and Ethnic Minorities|journal=華僑華人歷史研究|language=zh|volume=4|pages=77–78}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Shi|first1=Canjin|last2=Yu|first2=Linlin|year=2010|script-title=zh:少數民族華僑華人對我國構建'和諧邊疆'的影響及對策分析|trans-title=Analysis of the Influence of and Strategy Towards Overseas Chinese Ethnic Minorities in the Implementation of "Harmonious Borders"|journal=甘肅社會科學|language=zh|volume=1|pages=136–139}}</ref> or approximately one tenth of all Chinese emigrants (2006, 2011).<ref>{{cite book|script-title=zh:東干文化研究|last=Ding|first=Hong|publisher=中央民族學院出版社|year=1999|location=Beijing|page=63|language=zh|trans-title=The study of Dungan culture}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.qq.com/a/20110310/002046.htm|script-title=zh:在資金和財力上支持對海外少數民族僑胞宣傳|date=10 March 2011|publisher=人民網|language=zh|trans-title=On finances and resources to support information dissemination towards overseas Chinese ethnic minorities|access-date=24 December 2012|archive-date=19 September 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170919234650/http://news.qq.com/a/20110310/002046.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> Cross-border ethnic groups ({{zhi|s=跨境民族|p=kuàjìng mínzú}}) are not considered Chinese emigrant minorities unless they left China ''after'' the establishment of an independent state on China's border.<ref name="Barabantseva"/> | |||

| It has to be noted that the usage of the term can be relatively fluid, geographically. For example, the ethnic Chinese people of ] and ] are occasionally excluded from the above said definition of "overseas Chinese" in view of their close cultural and social affinity with China, despite the geographical divide of the said societies. This view is very rare, however, as recent researches shown, majority of the ethnic Chinese in both nations have expressed the view that they are bonded to their nation, rather than to China (either ] or ]). | |||

| Some ethnic groups who have historic connections with China, such as the ], may not or may identify themselves as Chinese.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.oac.cdlib.org/view?docId=hb4r29n9jg;NAAN=13030&doc.view=content&chunk.id=ch04&toc.depth=1&brand=oac4&anchor.id=0|title=A study of Southeast Asian youth in Philadelphia: A final report|website=Oac.cdlib.org|access-date=6 February 2017|archive-date=19 September 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170919234841/http://www.oac.cdlib.org/view?docId=hb4r29n9jg;NAAN=13030&doc.view=content&chunk.id=ch04&toc.depth=1&brand=oac4&anchor.id=0|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Overseas Chinese are not limited to ethnic Han Chinese populations, and may include the diaspora of the entire Chinese nation ('']''). For example, ], the famous Chinese explorer, who lived and died overseas is of ] ethnic; ] who are living in ] today are often included in calculations of overseas Chinese, because these ethnic Koreans also identify themselves as part of the Chinese nation; In ] and particularly in Malaysia and Singapore, the state classifies the ]s as Chinese despite partial assimilation into ] culture. | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{Main|Chinese emigration}} | |||

| The Chinese people have a long history of migrating overseas. The overseas Chinese of today can be dated back to the ]. When ] became the envoy of Ming, he sent people to explore and trade in the ] and ]. Many of them were ] and ]. Chinese emigrated to ] beginning in the 18th century, and have been identified as the ], or ]. | |||

| The Chinese people have a long history of migrating overseas, as far back as the 10th century. One of the migrations dates back to the ] when ] (1371–1435) became the envoy of Ming. He sent people – many of them ] and ] – to ] in the ] and in the ]. | |||

| A large portion stayed and never returned to China. Physical evidence such as ] in Malaysia seems to indicate permanent settlements. | |||

| ===Early emigration=== | |||

| In 19th century, the age of ] was at its height and the great ''']''' began. Many colonies lacked a large pool of laborers. Meanwhile, in the provinces of ] and ] in China, there was a labor surplus due to the relative peace in the ]. The Qing government was forced to allow its subjects to work overseas under colonial powers. Many Hokkien chose to work in Southeast Asia with their earlier links starting from the ] era, as did the Cantonese. For the countries in ] and ], great numbers of laborers were needed in the dangerous tasks of ] and ] construction. With famine widespread in Guangdong, this attracted many Cantonese to work in these countries to improve the living conditions of their relatives. Some overseas Chinese were sold to ] during ] in the ] in Guangdong. | |||

| ] | |||

| In the mid-1800s, outbound migration from China increased as a result of the European colonial powers opening up ].<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=137}} The British colonization of Hong Kong further created the opportunity for Chinese labor to be exported to plantations and mines.<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=137}} | |||

| With the completion of railways, many overseas Chinese suffered from racial discrimination in ] and the ], where they were barred from entering the country. | |||

| During the era of European colonialism, many overseas Chinese were ] laborers.<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=123}} Chinese capitalists overseas often functioned as economic and political intermediaries between colonial rulers and colonial populations.<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=123}} | |||

| After World War II, the last years of the ] increased Chinese suffering. Some educated overseas Chinese did not return to the country as the conditions deteriorated. | |||

| The area of ] was the source for many of economic migrants.<ref name="pan" /> In the provinces of ] and ] in China, there was a surge in emigration as a result of the poverty and village ruin.<ref>''The Story of California From the Earliest Days to the Present'', by Henry K. Norton. 7th ed. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co., 1924. Chapter XXIV, pp. 283–296.</ref> | |||

| Many people from the ] in ] emigrated to the UK (mainly England) and the Netherlands in the post-war period to earn a better living. | |||

| San Francisco and California was an early American destination in the mid-1800s because of the California Gold Rush. Many settled in San Francisco forming one of the earliest Chinatowns. For the countries in North America and Australia saw great numbers of Chinese gold diggers finding gold in the ] and ] construction. Widespread famine in Guangdong impelled many Cantonese to work in these countries to improve the living conditions of their relatives. | |||

| In 1980s, Britain agreed to transfer the sovereignty of ] to the PRC; this triggered another wave of migration to the United Kingdom (mainly England), Australia, Canada, United States of America and other lands. The ] further accelerated the migration. The wave calmed after the transfer of sovereignty in 1997. | |||

| From 1853 until the end of the 19th century, about 18,000 Chinese were brought as ] to the ], mainly to ] (now ]), ] and ].<ref>{{Cite book|title=Displacements and Diaspora|jstor = j.ctt5hj582|year = 2005|isbn = 9780813536101|publisher = Rutgers University Press}}</ref> Their descendants today are found among the current populations of these countries, but also among the migrant communities with Anglo-Caribbean origins residing mainly in the ], the ] and ]. | |||

| ==Current numbers== | |||

| There are approximately 34 million overseas Chinese, mostly living in ] where they make up a majority of the population of ] and significant minority populations in ], ], the ], ] and ]. The overseas populations in those areas arrived between the 16th and the 19th centuries mostly from the maritime provinces of ] and ], followed by ]. There are incidences of earlier emigration in the 10th centuries to 15th centuries in particular to ] and Southeast Asia. | |||

| Some overseas Chinese were sold to ] during the ] (1855–1867) in the ] in Guangdong. | |||

| ==Recent emigration== | |||

| More recent ] from the mid-19th century onward has been directed primarily to western countries such as ], ], ], ] and ], as well as to South America, where they are called '']''. Many of these emigrants who entered western countries were themselves overseas Chinese or were from Taiwan or Hong Kong, particularly in the 1950s to the 1980s, during which the PRC placed severe restrictions on the movement of its citizens. | |||

| ] women and children in ], {{circa|1945}}.]] | |||

| ==Assimilation== | |||

| Research conducted in 2008 by German researchers who wanted to show the correlation between economic development and height, used a small dataset of 159 male labourers from Guangdong who were sent to the Dutch colony of Suriname to illustrate their point. They stated that the Chinese labourers were between 161 to 164 cm in height for males.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Baten |first1=Jörg |title=Anthropometric Trends in Southern China, 1830–1864 |journal=Australian Economic History Review |date=November 2008 |volume=43 |issue=3 |pages=209–226|doi=10.1111/j.1467-8446.2008.00238.x}}</ref> Their study did not account for factors other than economic conditions and acknowledge the limitations of such a small sample. | |||

| Overseas Chinese vary widely as to their degree of ], their interactions with the surrounding communities (see ]), and their relationship with ]. In ], overseas Chinese have largely intermarried and assimilated with the native community. In ], the Chinese rarely intermarry (even amongst different Chinese linguistic groups), but have largely adopted the Burmese culture whilst maintaining Chinese culture affinities. ], ], and ] are among the countries that do not allow birth names to be registered in Chinese, because Chinese is not an official language in those countries. In ], names of ethnic Chinese are transliterated into ]. For example, 胡锦涛 (]: ]) would become "Hồ Cẩm Đào". Very often, there is no distinct number of the Chinese population in these countries. In western countries, the overseas Chinese generally use romanised versions of their Chinese names, and the use of local first names is also common. | |||

| ] of ], first until third generations]] | |||

| On the other hand, in ] and ], overseas Chinese have maintained a distinct communal identity, though the rate and state of being assimilated to the local, in this case a multicultural society, is currently en par with that of other Chinese communities (see ]). In the Philippines, many younger Overseas Chinese are well assimilated, whereas the older ones tend to be considered as 'foreigners'. More recent overseas Chinese immigrants have been despised by many Filipinos due to incidences of some selling illegal drugs, as well as being high profile smugglers. Chinese have also brought a cultural influence to some other countries such as Vietnam, where many customs have been adopted by native Vietnamese. | |||

| ], ] (present-day ]), {{circa|1881}}.]] | |||

| The ] in ] was established by overseas Chinese. | |||

| ==Waves of immigration== | |||

| Often there are different waves of immigration leading to subgroups among overseas Chinese such as the new and old immigrants in ], ], ], ], ], ], ],], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| In 1909, the Qing dynasty established the first ''Nationality Law'' of China.<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=138}} It granted Chinese citizenship to anyone born to a Chinese parent.<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=138}} It permitted ].<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=138}} | |||

| The Chinese in Southeast Asian countries have often established themselves in commerce and finances. In North America, because of immigration policies, overseas Chinese tend to be found in professional occupations, including significant ranks in medicine and academia. More recent Chinese presences have developed in ], where they number nearly a million, and in ], they number over 600,000, concentrated in Russia's Far East. | |||

| ===Republic of China=== | |||

| In the first half of the 20th Century, war and revolution accelerated the pace of migration out of China.<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=127}} The ] and the ] competed for political support from overseas Chinese.<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=|pages=127–128}} | |||

| Under the ] economic growth froze and many migrated outside the Republic of China, mostly through the coastal regions via the ports of ], ], ] and ]. These migrations are considered to be among the largest in China's history. Many nationals of the ] fled and settled down overseas mainly between the years 1911–1949 before the ] led by ] lost the mainland to Communist revolutionaries and relocated. Most of the nationalist and neutral refugees fled mainland China to ] while others fled to ] (], ], ], ], ] and ]) as well as ] (Republic of China).<ref name="Sarawakiana">{{cite web|title=Chiang Kai Shiek|url=http://sarawakiana.blogspot.com/2008/08/chiang-kai-shek-or-chiang-chung-cheng.html|publisher=Sarawakiana|access-date=28 August 2012|archive-date=6 December 2012|archive-url=https://archive.today/20121206041057/http://sarawakiana.blogspot.com/2008/08/chiang-kai-shek-or-chiang-chung-cheng.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===After World War II=== | |||

| Those who fled during 1912–1949 and settled down in ] and ] automatically gained citizenship in 1957 and 1963 as these countries gained independence.<ref>{{cite web|last=Yong|first=Ching Fatt|title=The Kuomintang Movement in British Malaya, 1912–1949|url=http://www.asianhistorybooks.com/malaysia/the-kuomintang-movement-in-british-malaya-1912-1949/|publisher=University of Hawaii Press|access-date=29 September 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131110140047/http://www.asianhistorybooks.com/malaysia/the-kuomintang-movement-in-british-malaya-1912-1949/|archive-date=10 November 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Tan|first=Kah Kee|title=The Making of an Overseas Chinese Legend|publisher=World Scientific Publishing Company|doi=10.1142/8692|year=2013|isbn=978-981-4447-89-8}}</ref> ] members who settled in Malaysia and Singapore played a major role in the establishment of the ] and their meeting hall at ]. There was evidence that some intended to reclaim mainland China from the CCP by funding the ].<ref name="Cham Jan Voon">{{cite thesis|degree=master|last=Jan Voon|first=Cham|title=Sarawak Chinese political thinking : 1911–1963|chapter=Kuomintang's influence on Sarawak Chinese|chapter-url=http://symposia.unimas.my/iii/sym/app?id=6596352876721218&lang=eng&service=blob&suite=def|publisher=University of Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS)|year=2002|access-date=28 August 2012}} {{dead link|date=March 2018 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes}}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine |last=Wong |first=Coleen |date=10 July 2013 |title=The KMT Soldiers Who Stayed Behind In China |url=https://thediplomat.com/china-power/the-kmt-soldiers-who-stayed-behind-in-china/ |magazine=] |access-date=29 September 2013 |archive-date=10 November 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131110152649/http://thediplomat.com/china-power/the-kmt-soldiers-who-stayed-behind-in-china/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ], Galicia, Spain.]] | |||

| After their defeat in the Chinese Civil War, parts of the ] retreated south and crossed the border into Burma as the ] entered ].<ref name=":Han2">{{Cite book |last=Han |first=Enze |title=The Ripple Effect: China's Complex Presence in Southeast Asia |date=2024 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-19-769659-0 |location=New York}}</ref>{{Rp|page=65}} The United States supported these Nationalist forces because the United States hoped they would harass the People's Republic of China from the southwest, thereby diverting Chinese resources from the ].<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=65}} The Burmese government protested and international pressure increased.<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=65}} Beginning in 1953, several rounds of withdrawals of the Nationalist forces and their families were carried out.<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=65}} In ] by China and Burma expelled the remaining Nationalist forces from Burma, although ] in the ].<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|pages=65–66}} | |||

| During the 1950s and 1960s, the ROC tended to seek the support of overseas Chinese communities through branches of the ] based on ]'s use of ] Chinese communities to raise money for his revolution. During this period, the People's Republic of China tended to view overseas Chinese with suspicion as possible ] infiltrators and tended to value relationships with Southeast Asian nations as more important than gaining support of overseas Chinese, and in the ] explicitly stated{{where|date=June 2020}} that overseas Chinese owed primary loyalty to their home nation.{{dubious|date=June 2020}} | |||

| From the mid-20th century onward, emigration has been directed primarily to Western countries such as the United States, Australia, Canada, Brazil, The United Kingdom, New Zealand, Argentina and the nations of Western Europe; as well as to Peru, Panama, and to a lesser extent to Mexico. Many of these emigrants who entered Western countries were themselves overseas Chinese, particularly from the 1950s to the 1980s, a period during which the PRC placed severe restrictions on the movement of its citizens. | |||

| Due to the political dynamics of the ], there was relatively little migration from the People's Republic of China to southeast Asia from the 1950s until the mid-1970s.<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=117}} | |||

| In 1984, Britain agreed to transfer the sovereignty of ] to the PRC; this triggered another wave of migration to the United Kingdom (mainly England), Australia, Canada, US, South America, Europe and other parts of the world. The ] further accelerated the migration. The wave calmed after Hong Kong's transfer of ] in 1997. In addition, many citizens of Hong Kong hold citizenships or have current visas in other countries so if the need arises, they can leave Hong Kong at short notice.{{Citation needed|reason=the preceding paragraph is entirely devoid of references|date=June 2018}} | |||

| In recent years, the People's Republic of China has built increasingly stronger ties with African nations. In 2014, author ] estimated that over one million Chinese have moved in the past 20 years to Africa.<ref name="africamove">{{cite magazine |last1=French |first1=Howard |date=November 2014 |title=China's Second Continent: How a Million Migrants Are Building a New Empire in Africa |url=https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/capsule-review/2014-10-17/chinas-second-continent-how-million-migrants-are-building-new |magazine=] |access-date=9 August 2020 |archive-date=6 November 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211106081253/https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/capsule-review/2014-10-17/chinas-second-continent-how-million-migrants-are-building-new |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| More recent Chinese presences have developed in Europe, where they number well over 1 million, and in Russia, they number over 200,000, concentrated in the ]. Russia's main Pacific port and naval base of ], once closed to foreigners and belonged to China until the late 19th century, {{as of | 2010 | lc = on}} bristles with Chinese markets, restaurants and trade houses. A growing Chinese community in Germany consists of around 76,000 people {{as of | 2010 | lc = on}}.<ref name="de-cn1">{{cite web|url=http://www.de-cn.net/dis/zgh/his/de2705231.htm|title=Deutsch-Chinesisches Kulturnetz|website=De-cn.net|language=de|access-date=6 February 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120413070711/http://www.de-cn.net/dis/zgh/his/de2705231.htm|archive-date=13 April 2012|url-status=dead}}</ref> An estimated 15,000 to 30,000 Chinese live in Austria.<ref name="eu-china1">{{cite web|url=http://www.eu-china.net/web/cms/upload/pdf/materialien/p35_chinesen_08-09-30.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110721171842/http://www.eu-china.net/web/cms/upload/pdf/materialien/p35_chinesen_08-09-30.pdf |archive-date=2011-07-21 |url-status=live|title=Heimat süßsauer|website=Eu-china.net|language=de|access-date=27 May 2018}}</ref> | |||

| ==Overseas Chinese experience== | |||

| ] in the past set up small enterprises such as street vending to eke out a living.]] | |||

| ===Commercial success=== | |||

| {{Main|Bamboo network}} | |||

| Chinese emigrants are estimated to control US$2 trillion in liquid assets and have considerable amounts of wealth to stimulate economic power in ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Bartlett|first=David|title=The Political Economy of Dual Transformations: Market Reform and Democratization in Hungary|url=https://archive.org/details/politicaleconomy0000bart|url-access=registration|year=1997|publisher=University of Michigan Press|page=|isbn=9780472107940}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Fukuda|first=Kazuo John|title=Japan and China: The Meeting of Asia's Economic Giants|year=1998|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-0-7890-0417-8|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M_e_HadcM_AC&pg=PA103|access-date=2 June 2020|archive-date=11 April 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230411212924/https://books.google.com/books?id=M_e_HadcM_AC&pg=PA103|url-status=live}}</ref> The Chinese business community of Southeast Asia, known as the ], has a prominent role in the region's private sectors.<ref name="Weidenbaum">{{cite book|author=Murray L Weidenbaum|title=The Bamboo Network: How Expatriate Chinese Entrepreneurs are Creating a New Economic Superpower in Asia|url=https://archive.org/details/bamboonetworkhow00weid|url-access=registration|date=1996|publisher=Martin Kessler Books, Free Press|isbn=978-0-684-82289-1|pages=–5}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.worldbusinesslive.com/research/article/648273/the-worlds-successful-diasporas/|title=The world's successful diasporas|website=Worldbusinesslive.com|access-date=18 March 2015|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080401110233/http://www.worldbusinesslive.com/research/article/648273/the-worlds-successful-diasporas/|archive-date=1 April 2008}}</ref> | |||

| In Europe, North America and Oceania, occupations are diverse and impossible to generalize; ranging from catering to significant ranks in ], ] and ]. | |||

| Overseas Chinese often send ]s back home to family members to help better them financially and socioeconomically. China ranks second after India of top remittance-receiving countries in 2018 with over US$67 billion sent.<ref>{{cite news |date=8 December 2018 |title=India to retain top position in remittances with $80 billion: World Bank |newspaper=] |url=https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/nri/forex-and-remittance/india-to-retain-top-position-in-remittances-with-80-billion-world-bank/articleshow/66998062.cms |access-date=8 December 2018 |archive-date=15 April 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210415054818/https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/nri/forex-and-remittance/india-to-retain-top-position-in-remittances-with-80-billion-world-bank/articleshow/66998062.cms |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Assimilation=== | |||

| ] in a wedding in ], 2006]] | |||

| Overseas Chinese communities vary widely as to their degree of ], their interactions with the surrounding communities (see ]), and their relationship with China. | |||

| Thailand has the largest overseas Chinese community and is also the most successful case of ], with many claiming ]. For over 400 years, descendants of Thai Chinese have largely intermarried and/or assimilated with their compatriots. The present royal house of Thailand, the ], was founded by King ] who himself was partly of Chinese ancestry. His predecessor, King ] of the ], was the son of a Chinese immigrant from Guangdong Province and was born with a Chinese name. His mother, Lady Nok-iang (Thai: นกเอี้ยง), was ] (and was later awarded the ] of Somdet Krom Phra Phithak Thephamat). | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| | image2 = Sangelys,_detail_from_Carta_Hydrographica_y_Chorographica_de_las_Yslas_Filipinas_(1734).jpg | |||

| | caption2 = ]s, of different religion and social classes, as depicted in the ] (1734) | |||

| }} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | image2 = Commercant chinois Hanoi 2.jpg | |||

| | width2 = 150 | |||

| | alt2 = Chinese Vietnamese | |||

| | caption2 = A ] merchant in ], {{circa|1885}}. | |||

| }} | |||

| In the Philippines, the Chinese, known as the ], from ] and ] were already migrating to the islands as early as 9th century, where many have largely intermarried with both ] and ]s (]). Early presence of ]s in overseas communities start to appear in ] around 16th century in the form of ] in ], where Chinese merchants were allowed to reside and flourish as commercial centers, thus ], a historical district of Manila, has become the world's oldest Chinatown.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/388446/lifestyle/food/binondo-new-discoveries-in-the-world-s-oldest-chinatown|title=Binondo: New discoveries in the world's oldest Chinatown|last=See|first=Stanley Baldwin O.|date=17 November 2014|work=GMA News Online|access-date=28 July 2019|archive-date=18 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200818010657/https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/lifestyle/food/388446/binondo-new-discoveries-in-the-world-s-oldest-chinatown/story/|url-status=live}}</ref> Under Spanish colonial policy of ], ] and ], their colonial mixed descendants would eventually form the bulk of the ] which would later rise to the ] and ], which carried over and fueled the elite ruling classes of the ] and later independent Philippines. Chinese Filipinos play a considerable role in the ]<ref>{{Cite book|last=Chua|first=Amy|title=World On Fire|publisher=Knopf Doubleday Publishing|year=2003|isbn=978-0385721868|pages=3, 6}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Gambe|first=Annabelle|title=Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurship and Capitalist Development in Southeast Asia|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|year=2000|isbn=978-0312234966|page=33}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Folk|first=Brian|title=Ethnic Business: Chinese Capitalism in Southeast Asia|publisher=Routledge|year=2003|isbn=978-1138811072|page=93}}</ref><ref name="Chirot">{{Cite book|last1=Chirot|first1=Daniel|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BgWumPDyaSIC&pg=PA54|title=Essential Outsiders: Chinese and Jews in the Modern Transformation of Southeast Asia and Central Europe|last2=Reid|first2=Anthony|publisher=University of Washington Press|year=1997|isbn=9780295800264|page=54|access-date=29 September 2021|archive-date=18 February 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230218081158/https://books.google.com/books?id=BgWumPDyaSIC&pg=PA54|url-status=live}}</ref> and descendants of Sangley compose a considerable part of the ].<ref name="Chirot" /><ref>{{Cite web|date=April 13, 2005|title=Genographic Project – Reference Populations – Geno 2.0 Next Generation|url=https://genographic.nationalgeographic.com/reference-populations-next-gen/|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190522144837/https://genographic.nationalgeographic.com/reference-populations-next-gen/|archive-date=May 22, 2019|website=National Geographic}}</ref> Ferdinand Marcos, the former president of the Philippines Ferdinand Marcos was of Chinese descent, as were many others.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Tan |first=Antonio S. |date=1986 |title=The Chinese Mestizos and the Formation of the Filipino Nationality |url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/arch_0044-8613_1986_num_32_1_2316 |journal=Archipel |volume=32 |issue=1 |pages=141–162 |doi=10.3406/arch.1986.2316}}</ref> | |||

| ] community. Most of them in Singapore were once concentrated in ].]] | |||

| ] shares a long border with China so ethnic minorities of both countries have cross-border settlements. These include the Kachin, Shan, Wa, and Ta’ang.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2023-03-14 |title=Ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia's Borderland: Assessing Chinese Nationalism in Upper Shan State |url=https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/seac/2023/03/14/ethnic-chinese-in-southeast-asias-borderland-assessing-chinese-nationalism-in-upper-shan-state/ |access-date=2024-03-17 |website=LSE Southeast Asia Blog}}</ref> | |||

| In ], between 1965 and 1993, people with Chinese names were prevented from finding governmental employment, leading to a large number of people changing their names to a local, Cambodian name. Ethnic Chinese were one of the minority groups targeted by Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge during the Cambodian genocide.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2024-03-11 |title=Khmer Rouge {{!}} Facts, Leadership, Genocide, & Death Toll {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Khmer-Rouge |access-date=2024-03-17 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Indonesia forced Chinese people to adopt Indonesian names after the ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=More Chinese-Indonesians using online services to find their Chinese names – Community |url=https://www.thejakartapost.com/culture/2023/01/19/more-chinese-indonesians-using-online-services-to-find-their-chinese-names.html |access-date=2024-03-17 |website=The Jakarta Post |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| In Vietnam, all Chinese names can be pronounced by ]. For example, the name of the previous ] ] ({{lang|zh-cn|胡錦濤}}) would be spelled as "Hồ Cẩm Đào" in Vietnamese. There are also great similarities between Vietnamese and Chinese traditions such as the use Lunar New Year, philosophy such as ], ] and ancestor worship; leads to some ] adopt easily to Vietnamese culture, however many Hoa still prefer to maintain Chinese cultural background. The official census from 2009 accounted the Hoa population at some 823,000 individuals and ranked 6th in terms of its population size. 70% of the Hoa live in cities and towns, mostly in Ho Chi Minh city while the rests live in the southern provinces.<ref name="GSO2009">{{cite web |url=https://www.gso.gov.vn/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/KQ-toan-bo-1.pdf |title=Kết quả toàn bộ Tổng điều tra Dân số và Nhà ở Việt Nam năm 2009–Phần I: Biểu Tổng hợp |trans-title=The 2009 Vietnam Population and Housing census: Completed results |author=] |page=134/882 |language=vi |access-date=13 December 2012 |archive-date=26 October 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211026063744/https://www.gso.gov.vn/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/KQ-toan-bo-1.pdf |url-status=live }} (description page: {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210615163023/https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/data-and-statistics/2019/03/the-2009-vietnam-population-and-housing-census-completed-results/ |date=15 June 2021 }})</ref> | |||

| On the other hand, in Malaysia, Singapore, and ], the ethnic Chinese have maintained a distinct communal identity. | |||

| In ], a large fraction of Chinese are of ]. | |||

| In Western countries, the overseas Chinese generally use romanised versions of their Chinese names, and the use of local first names is also common. | |||

| ===Discrimination=== | |||

| {{See also|Sinophobia}} | |||

| Overseas Chinese have often experienced hostility and ]. In countries with small ethnic Chinese minorities, the ] can be remarkable. For example, in 1998, ethnic Chinese made up just 1% of the population of the ] and 4% of the population in ], but have wide influence in the Philippine and Indonesian private economies.<ref>Amy Chua, "World on Fire", 2003, Doubleday, pp. 3, 43.</ref> The book '']'', describing the Chinese as a "market-]", notes that "Chinese market dominance and intense resentment amongst the indigenous majority is characteristic of virtually every country in Southeast Asia except Thailand and Singapore".<ref>Amy Chua, ''World on Fire'', 2003, Doubleday, p. 61. {{ISBN?}}</ref> | |||

| This asymmetrical economic position has incited anti-Chinese sentiment among the poorer majorities. Sometimes the anti-Chinese attitudes turn violent, such as the ] in Malaysia in 1969 and the ] in Indonesia, in which more than 2,000 people died, mostly rioters burned to death in a shopping mall.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160410061243/http://www.economist.com/world/asia/displayStory.cfm?story_id=4323219 |date=10 April 2016 }}. The Economist Newspaper Limited (25 August 2005). Requires login.</ref> | |||

| During the ], in which more than 500,000 people died,<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180110050921/http://www.smh.com.au/news/world/indonesian-academics-fight-burning-of-books-on-1965-coup/2007/08/08/1186530448353.html |date=10 January 2018 }}, ''The Sydney Morning Herald''</ref> ethnic Chinese Hakkas were killed and their properties looted and burned as a result of ] on the excuse that ] had brought the ] closer to China.<ref>Vickers (2005), p. 158</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Analysis – Indonesia: Why ethnic Chinese are afraid |work=] |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/analysis/51981.stm |access-date=18 March 2015 |archive-date=24 August 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170824095624/http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/analysis/51981.stm |url-status=live }}</ref> The ] was in the Indonesian constitution until 1998. | |||

| The state of the ] during the ] regime has been described as "the worst disaster ever to befall any ethnic Chinese community in Southeast Asia." At the beginning of the Khmer Rouge regime in 1975, there were 425,000 ethnic Chinese in ]; by the end of 1979 there were just 200,000.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective|first1=Robert|last1=Gellately|first2=Ben|last2=Kiernan|publisher=]|year=2003|pages=313–314}}</ref> | |||

| It is commonly held that a major point of friction is the apparent tendency of overseas Chinese to segregate themselves into a subculture.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Palona |first=Iryna |year=2010 |title=Asian Megatrends and Management Education of Overseas Chinese |url=https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1066089.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170221042353/http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1066089.pdf |archive-date=2017-02-21 |url-status=live |journal=International Education Studies |location=United Kingdom |volume=3 |pages=58–65 |via=]}}</ref>{{Failed verification|date=January 2024|reason=source does not mention segregation of Chinese}} For example, the anti-Chinese ] and ] were believed to have been motivated by these racially biased perceptions.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Michael Shari |date=2000-10-09 |title=Wages of Hatred |url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2000-10-08/wages-of-hatred?srnd=undefined |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20240111120115/https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2000-10-08/wages-of-hatred?srnd=undefined |archive-date=11 January 2024 |website=] |access-date=11 January 2024 |url-status=live }}</ref> This analysis has been questioned by some historians, notably Dr. ], who has put forward the controversial argument that the 13 May Incident was a pre-meditated attempt by sections of the ruling Malay elite to incite racial hostility in preparation for a coup.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Baradan Kuppusamy |date=2007-05-14 |title=Politicians linked to Malaysia's May 13 riots |url=https://www.scmp.com/article/592766/politicians-linked-malaysias-may-13-riots |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221121164847/https://www.scmp.com/article/592766/politicians-linked-malaysias-may-13-riots |archive-date=2022-11-21 |website=South China Morning Post |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.littlespeck.com/ThePast/CPast-My-kiasoong-070517.htm |title=May 13 by Kua Kia Soong |publisher=Littlespeck.com |access-date=7 May 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121014093600/http://littlespeck.com/ThePast/CPast-My-kiasoong-070517.htm |archive-date=14 October 2012 |url-status=dead}}</ref> In 2006, rioters damaged shops owned by Chinese-]ns in ].<ref name="NZ_Herald_229612">{{cite news |url=http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=229612 |title=Editorial: Racist moves will rebound on Tonga |date=23 November 2001 |work=] |access-date=1 November 2011 |archive-date=5 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200805191515/https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=229612 |url-status=live }}</ref> Chinese migrants were evacuated from the riot-torn ].<ref>Spiller, Penny: " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121202134436/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/4930994.stm |date=2 December 2012 }}", ], 21 April 2006</ref> | |||

| Ethnic politics can be found to motivate both sides of the debate. In Malaysia, many "]" ("native sons") ] oppose equal or meritocratic treatment towards Chinese and ], fearing they would dominate too many aspects of the country.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Chin |first=James |date=2015-08-27 |title=Opinion {{!}} The Costs of Malay Supremacy |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/28/opinion/the-costs-of-malay-supremacy.html |access-date=2022-11-02 |issn=0362-4331 |archive-date=2 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221102050801/https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/28/opinion/the-costs-of-malay-supremacy.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite magazine |last=Ian Buruma |date=2009-05-11 |title=Eastern Promises |url=https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/05/18/eastern-promises |magazine=] |language=en-US |access-date=2 November 2022 |archive-date=2 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221102052251/https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/05/18/eastern-promises |url-status=live }}</ref> The question of to what extent ethnic Malays, Chinese, or others are "native" to Malaysia is a sensitive political one. It is currently a taboo for Chinese politicians to raise the issue of Bumiputra protections in parliament, as this would be deemed ethnic incitement.<ref>{{cite web |author=Vijay Joshi |date=31 August 2007 |title=Race clouds Malaysian birthday festivities |url=http://www.iol.co.za/index.php?from=rss_Asia&set_id=1&click_id=126&art_id=nw20070831094150283C984737 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100902182747/http://www.iol.co.za/index.php?from=rss_Asia&set_id=1&click_id=126&art_id=nw20070831094150283C984737 |archive-date=2 September 2010 |access-date=18 March 2015 |work=Independent Online}}</ref> | |||

| Many of the overseas Chinese emigrants who worked on railways in North America in the 19th century suffered from racial discrimination in Canada and the United States. Although discriminatory laws have been repealed or are no longer enforced today, both countries had at one time introduced statutes that barred Chinese from entering the country, for example the United States ] of 1882 (repealed 1943) or the Canadian ] (repealed 1947). In both the United States and Canada, further acts were required to fully remove immigration restrictions (namely United States' Immigration and Nationality Acts of ] and ], in addition to Canada's) | |||

| In Australia, Chinese were targeted by a system of discriminatory laws known as the ']' which was enshrined in the ]. The policy was formally abolished in 1973, and in recent years ] have publicly called for an apology from the Australian Federal Government<ref>{{cite web |author=The World Today Barbara Miller |url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-06-30/chinese-australians-want-apology-for-discrimination/2778014 |title=Chinese Australians want apology for discrimination |publisher=Australian Broadcasting Corporation |date=30 June 2011 |access-date=7 May 2012 |archive-date=27 September 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210927145016/https://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-06-30/chinese-australians-want-apology-for-discrimination/2778014 |url-status=live }}</ref> similar to that given to the 'stolen generations' of indigenous people in 2007 by the then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd. | |||

| In South Korea, the relatively low social and economic statuses of ] have played a role in local hostility towards them.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |last=Hyun-ju |first=Ock |date=2017-09-24 |title= Ethnic Korean-Chinese fight 'criminal' stigma in Korea |url=http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20170924000289 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201202005913/http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20170924000289 |archive-date=2020-12-02 |website=] |language=en}}</ref> Such hatred had been formed since their early settlement years, where many Chinese–Koreans hailing from rural areas were accused of misbehaviour such as ] on streets and ]ing.<ref name=":0" /> More recently, they have also been targets of hate speech for their association with violent crime,<ref>{{Cite web |date=April 25, 2012 |title=Anti Chinese–Korean Sentiment on Rise in Wake of Fresh Attack |url=https://www.koreabang.com/2012/stories/anti-chinese-korean-sentiment-on-rise-in-wake-of-fresh-attack.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210131133828/https://www.koreabang.com/2012/stories/anti-chinese-korean-sentiment-on-rise-in-wake-of-fresh-attack.html |archive-date=January 31, 2021 |website=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=January 2018 |title=Hate Speech against Immigrants in Korea: A Text Mining Analysis of Comments on News about Foreign Migrant Workers and Korean Chinese Residents|page =281 |url=http://snuac.snu.ac.kr/2015_snuac/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/10-2_%ED%8A%B9%EC%A7%91-2_Injin-Yoon.pdf |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201205175450/http://snuac.snu.ac.kr/2015_snuac/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/10-2_%ED%8A%B9%EC%A7%91-2_Injin-Yoon.pdf |archive-date=2020-12-05 |website=] |publication-place=]}}</ref> despite the Korean Justice Ministry recording a lower crime rate for Chinese in the country compared to native South Koreans in 2010.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Ramstad |first=Evan |date=2011-08-23 |title=Foreigner Crime in South Korea: The Data |language=en-US |work=] |url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-KRTB-2071 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://archive.today/20220104175101/https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-KRTB-2071 |archive-date=2022-01-04 |issn=0099-9660}}</ref> | |||

| ==Relationship with China== | ==Relationship with China== | ||

| {{see also|United front (China)|Ethnic interest group}} | |||

| Both the ] and the ] maintain highly complex relationships with overseas Chinese populations. Both maintain cabinet level ministries to deal with overseas Chinese affairs, and many local governments within the PRC have overseas Chinese bureaus. Both the PRC and ROC have some legislative representation for overseas Chinese. In the case of the PRC, some seats in the ] are allocated for returned overseas Chinese. In the ROC's ], there are eight seats allocated for overseas Chinese. These seats are apportioned to the political parties based on their vote totals on Taiwan, and then the parties assign the seats to overseas Chinese party ]. Most of these members elected to the Legislative Yuan hold dual citizenship, but must renounce their foreign citizenship (at the ] for American citizens) before being sworn in. | |||

| ] | |||

| Both the ] and the ] (known more commonly as Taiwan) maintain high level relationships with the overseas Chinese populations. Both maintain ] ministries to deal with overseas Chinese affairs, and many local governments within the PRC have overseas Chinese bureaus. | |||

| During the 1950s and 1960s, the ROC tended to seek the support of overseas Chinese communities through branches of the ] based on ]'s use of ] Chinese communities to raise money for his revolution. During this period, the People's Republic of China tended to view overseas Chinese with suspicion as possible ] infiltrators and tended to value relationships with southeast Asian nations as more important than gaining support of overseas Chinese, and in the ] explicitly stated that overseas Chinese owed primary loyalty to their home nation. | |||

| Before 2018, the PRC's ] (OCAO) under the ] was responsible for liaising with overseas Chinese.<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=132}} In 2018, the office was merged into the ] of the ].<ref name=":02">{{Cite news |last=Joske |first=Alex |author-link=Alex Joske |date=May 9, 2019 |title=Reorganizing the United Front Work Department: New Structures for a New Era of Diaspora and Religious Affairs Work |url=https://jamestown.org/program/reorganizing-the-united-front-work-department-new-structures-for-a-new-era-of-diaspora-and-religious-affairs-work/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190721191900/https://jamestown.org/program/reorganizing-the-united-front-work-department-new-structures-for-a-new-era-of-diaspora-and-religious-affairs-work/ |archive-date=July 21, 2019 |access-date=2019-07-27 |website=] |language=en-US}}</ref><ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=132}} | |||

| After the ] reforms, the attitude of the PRC toward overseas Chinese changed dramatically. Rather than being seen with suspicion, they were seen as people which could aid PRC development via their skills and capital. During the 1980s, the PRC actively attempted to court the support of overseas Chinese by among other things, returning properties that were confiscated after the 1949 revolution. More recently PRC policy has attempted to maintain the support of recently emigrated Chinese, who consist largely of Chinese seeking graduate education in the West. | |||

| Throughout its existence but particularly during the ] administration, the PRC makes patriotic appeals to overseas Chinese to assist the country's political and economic needs.<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=132}} In a July 2022 meeting with the United Front Work Department, Xi encouraged overseas Chinese to support China's rejuvenation and stated that domestic and overseas Chinese should pool their strengths to realize the ].<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=132}} In the PRC's view, overseas Chinese are an asset to demonstrating a positive image of China internationally.<ref name=":Han2" />{{Rp|page=133}} | |||

| Overseas Chinese have sometimes played an important role in Chinese politics. Most of the funding for the ] came from overseas Chinese, and many overseas Chinese are ]. Many overseas Chinese are now investing in mainland China providing ] resources, social and ] networks, contacts and opportunities. | |||

| ===Citizenship status=== | |||

| ==Statistics== | |||

| The ], which does not recognise ], provides for automatic loss of PRC citizenship when a former PRC citizen both settles in another country ''and'' acquires foreign citizenship. For children born overseas of a PRC citizen, whether the child receives PRC citizenship at birth depends on whether the PRC parent has settled overseas: ''"Any person born abroad whose parents are both Chinese nationals or one of whose parents is a Chinese national shall have Chinese nationality. But a person whose parents are both Chinese nationals and have both settled abroad, or one of whose parents is a Chinese national and has settled abroad, and who has acquired foreign nationality at birth shall not have Chinese nationality"'' (Article 5).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.china.org.cn/english/LivinginChina/184710.htm|title=Nationality Law of the People's Republic of China|publisher=china.org.cn|access-date=18 March 2015|archive-date=7 November 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211107210849/http://www.china.org.cn/english/LivinginChina/184710.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| By contrast, the ], which both permits and recognises dual citizenship, considers such persons to be citizens of the ROC (if their parents have household registration in Taiwan). | |||

| {{not verified}} | |||

| ===Returning and re-emigration=== | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| {{main|Haigui}} | |||

| |-bgcolor="#EFEFEF" | |||

| !Continent/Country||Overseas Chinese Population||% of local<br>population||% of Global<br>Overseas Chinese population | |||

| With China's growing economic strength, many of the overseas Chinese have begun to migrate back to China, even though many mainland Chinese millionaires are considering emigrating out of the nation for better opportunities.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://business.blogs.cnn.com/2011/11/01/report-half-of-chinas-rich-want-to-leave/ |publisher=CNN |title=Report: Half of China's millionaires want to leave |date=1 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120711131410/http://business.blogs.cnn.com/2011/11/01/report-half-of-chinas-rich-want-to-leave/ |archive-date=11 July 2012}}</ref> | |||

| |-bgcolor="yellow" | |||

| |]||51,800,000 (1998)||0.7%||81% | |||

| In the case of ] and ], political strife and ethnic tensions has caused a significant number of people of Chinese origins to re-emigrate back to China. In other Southeast Asian countries with large Chinese communities, such as Malaysia, the economic rise of People's Republic of China has made the PRC an attractive destination for many Malaysian Chinese to re-emigrate. As the Chinese economy opens up, Malaysian Chinese act as a bridge because many Malaysian Chinese are educated in the United States or Britain but can also understand the Chinese language and culture making it easier for potential entrepreneurial and business to be done between the people among the two countries.<ref>{{cite news |date=30 December 2011 |title=Will China's rise shape Malaysian Chinese community? |work=] |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-16284388 |access-date=20 June 2018 |archive-date=27 September 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210927053138/https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-16284388 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| After the ] reforms, the attitude of the PRC toward the overseas Chinese changed dramatically. Rather than being seen with suspicion, they were seen as people who could aid PRC development via their skills and ]. During the 1980s, the PRC actively attempted to court the support of overseas Chinese by among other things, returning properties that had been confiscated after the 1949 revolution. More recently PRC policy has attempted to maintain the support of recently emigrated Chinese, who consist largely of Chinese students seeking undergraduate and graduate education in the West. Many of the Chinese diaspora are now investing in People's Republic of China providing ] resources, social and ] networks, contacts and opportunities.<ref>{{Cite web |author=Jieh-Yung Lo |date=6 March 2018 |title=Beijing's welcome mat for overseas Chinese |url=https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/beijing-s-welcome-mat-overseas-chinese |website=] |language=en |access-date=17 July 2022 |archive-date=17 July 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220717122859/https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/beijing-s-welcome-mat-overseas-chinese |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kWGI4_EzumsC&q=overseas+chinese+control+percent+of+the+largest+companies&pg=PT107 |title=The Cultural Imperative |author=Richard D. Lewis |access-date=9 May 2012 |isbn=9780585434902 |year=2003 |publisher=Intercultural Press |archive-date=11 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230411212929/https://books.google.com/books?id=kWGI4_EzumsC&q=overseas+chinese+control+percent+of+the+largest+companies&pg=PT107 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The Chinese government estimates that of the 1,200,000 Chinese people who have gone overseas to study in the thirty years since ] beginning in 1978; three-quarters of those who left have not returned to China.<ref>{{cite news|last1=Zhou|first1=Wanfeng|title=China goes on the road to lure 'sea turtles' home|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-financial-seaturtles-idUSTRE4BH02220081218|access-date=13 June 2016|work=Reuters|date=17 December 2008|archive-date=27 September 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210927222848/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-financial-seaturtles-idUSTRE4BH02220081218|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Beijing is attracting overseas-trained academics back home, in an attempt to internationalise its universities. However, some professors educated to the PhD level in the West have reported feeling "marginalised" when they return to China due in large part to the country's “lack of international academic peer review and ] mechanisms”.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Lau |first1=Joyce |date=21 August 2020 |title=Returning Chinese scholars 'marginalised' at home and abroad |work=] |url=https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/returning-chinese-scholars-marginalised-home-and-internationally#comment-58117 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220419090036/https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/returning-chinese-scholars-marginalised-home-and-internationally |archive-date=19 April 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ==Language== | |||

| {{main|Language and overseas Chinese communities}} | |||

| The usage of Chinese by the overseas Chinese has been determined by a large number of factors, including their ancestry, their migrant ancestors' ], assimilation through generational changes, and official policies of their country of residence. The general trend is that more established Chinese populations in the Western world and in many regions of Asia have ] as either the dominant variety or as a common community vernacular, while ] is much more prevalent among new arrivals, making it increasingly common in many Chinatowns.<ref name="West 2010, pp. 289-90">West (2010), pp. 289–290</ref><ref>{{cite news | url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2006-mar-31-me-sangabriel31-story.html | work=Los Angeles Times | first=David | last=Pierson | title=Dragon Roars in San Gabriel | date=31 March 2006 | access-date=20 February 2020 | archive-date=13 August 2021 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210813151503/https://articles.latimes.com/2006/mar/31/local/me-sangabriel31 | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Country statistics== | |||

| ] was the first president of ] even though the Indians are the predominant ethnicity within the nation.]] | |||

| There are over 50 million overseas Chinese.<ref name="auto">{{cite web |author=張明愛 |url=http://www.china.org.cn/china/NPC_CPPCC_2012/2012-03/11/content_24865428.htm |title=Reforms urged to attract overseas Chinese |website=China.org.cn |date=11 March 2012 |access-date=28 May 2012 |archive-date=20 May 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170520123716/http://www.china.org.cn/china/NPC_CPPCC_2012/2012-03/11/content_24865428.htm |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="English.gov.cn">{{cite web |url = http://english.gov.cn/2012-04/09/content_2109393.htm |title=President meets leaders of overseas Chinese organizations |website=English.gov.cn |date=9 April 2012 |access-date=28 May 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120528112204/https://english.gov.cn/2012-04/09/content_2109393.htm |archive-date=28 May 2012}}</ref><ref name="Huiyao Wang 2">{{cite web |url=http://www.asiapacific.ca/sites/default/files/filefield/researchreportv7.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140221161915/http://www.asiapacific.ca/sites/default/files/filefield/researchreportv7.pdf |archive-date=2014-02-21 |url-status=live |title=China's Competition for Global Talents: Strategy, Policy and Recommendations |publisher=Asia Pacific |date=24 May 201 |access-date=28 May 2012 |first=Huiyao |last=Wang |page=2}}</ref> Most of them are living in ] where they make up a majority of the population of ] (75%) and significant minority populations in ] (23%), ] (14%) and ] (10%). | |||

| ] | |||

| {| class="wikitable sortable" | |||

| |- style="background:#fff;" | |||

| !Continent / country | |||

| !Articles | |||

| ! data-sort-type="number" |Overseas Chinese Population || data-sort-type="number" |Percentage || Year of data | |||

| |- style="background:#ccf;" | |||

| |''']''' || || '''700,000''' || || | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |{{flag|South Africa}} || ] || 300,000–400,000 || <1% || 2015<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Liao|first1=Wenhui|last2=He|first2=Qicai|title=Tenth World Conference of Overseas Chinese: Annual International Symposium on Regional Academic Activities Report (translated)|journal=The International Journal of Diasporic Chinese Studies|year=2015|volume=7|issue=2|pages=85–89}}</ref> | |||

| |]||7.3 million (2003)||3.1%||20.7% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |{{flag|Madagascar}} || ] || 100,000 || || 2011<ref name="temporarychinese">{{cite journal|last1=Tremann|first1=Cornelia|title=Temporary Chinese Migration to Madagascar: Local Perceptions, Economic Impacts, and Human Capital Flows|journal=African Review of Economics and Finance|date=December 2013|volume=5|issue=1|url=http://www.african-review.com/Vol.%205%20(1)/Tremann.pdf|access-date=21 April 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140810093752/http://www.african-review.com/Vol.%205%20(1)/Tremann.pdf|archive-date=10 August 2014|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| |]||7.3 million (2003)||12%||20.7% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |{{flag|Namibia}} || ] || 100,000 || 4.3% || 2021<ref name="Namibia">{{citation| url=https://worldwithoutgenocide.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/China-in-Namibia-Updated-Images.pdf |title=china in namibia}}</ref> | |||

| |]||7 million (2004)||25%||19.9% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |{{flag|Zambia}} || ] || 13,000 || || 2019<ref name="zambia">{{cite news|title=Zambia has 13,000 Chinese|url=https://www.daily-mail.co.zm/?p=23914|publisher=Zambia Daily Mail News|date=21 March 2015|access-date=21 April 2015|archive-date=23 September 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210923201345/https://www.daily-mail.co.zm/zambia-13000-chinese/|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| |]||2.7 million (2005) ()||75.6%||7.6% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |{{flag|Ethiopia}} || ] || 60,000 || || 2016<ref name="worlddevelopment">{{cite journal|title=Chinese Migrants in Africa: Facts and Fictions from the Agri-Food Sector in Ethiopia and Ghana|journal=World Development|date=May 2016|volume=81|pages=61–70|doi=10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.11.011|last1=Cook|first1=Seth|last2=Lu|first2=Jixia|last3=Tugendhat|first3=Henry|last4=Alemu|first4=Dawit|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="ethiopia">{{cite news|title=China empowers a million Ethiopians: ambassador|url=https://www.enca.com/money/china-empowers-million-ethiopians-ambassador|agency=Africa News Agency|date=26 January 2016|access-date=27 January 2016|archive-date=15 September 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170915204139/https://www.enca.com/money/china-empowers-million-ethiopians-ambassador|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |]||2.3 million (2003)||3%||6.5% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |{{flag|Angola}} || ] || 50,000 || || 2017<ref name="angoladown">{{cite news|title=Chinese Businesses Quit Angola After 'Disastrous' Currency Blow|url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-04-20/chinese-businesses-quit-angola-after-disastrous-currency-blow|publisher=Bloomberg|date=20 April 2017|access-date=6 May 2017|archive-date=15 September 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170915204545/https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-04-20/chinese-businesses-quit-angola-after-disastrous-currency-blow|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |]||1.5 million (2004)||2%||4.3% | |||

| |- | |- | ||