| Revision as of 01:05, 21 April 2016 edit70.123.233.120 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:20, 24 November 2024 edit undoOpenmy (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users10,690 editsNo edit summary | ||

| (606 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|American singer-songwriter (1937–2016)}} | |||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=April 2016}} | {{Use mdy dates|date=April 2016}} | ||

| {{Infobox musical artist | {{Infobox musical artist | ||

| | name |

| name = Merle Haggard | ||

| | |

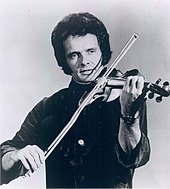

| image = Merle Haggard in 1971.jpg | ||

| | |

| caption = Haggard performing live in 1971 | ||

| | |

| birth_name = Merle Ronald Haggard | ||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1937|04|06|mf=yes}} | |||

| | birth_name = Merle Ronald Haggard | |||

| | birth_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | alias = Hag | |||

| | |

| death_date = {{death date and age|2016|04|06|1937|04|06|mf=yes}} | ||

| | |

| death_place = ], U.S. | ||

| | |

| instrument = {{hlist|Vocals|guitar|]}} | ||

| | |

| genre = {{flatlist| | ||

| *] | |||

| | cause_of_death = ] | |||

| *] | |||

| | genre = ], ], ] | |||

| *]}} | |||

| | occupation = Songwriter, musician, guitarist, singer | |||

| | |

| occupation = Singer, songwriter, musician | ||

| | years_active = 1961–2016 | |||

| | label = ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | |

| label = {{flatlist| | ||

| *] | |||

| | notable_instruments = ] | |||

| *] | |||

| | instruments = ], ] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *]}} | |||

| | past_member_of = ] | |||

| | module = {{Infobox person|embed=yes | |||

| | spouse = {{plainlist| | |||

| * {{marriage|Leona Hobbs|1956|1964|reason=divorced}} | |||

| * {{marriage|]|1965|1978|reason=divorced}} | |||

| * {{marriage|]|1978|1983|reason=divorced}} | |||

| * {{marriage|Debbie Parret|1985|1991|reason=divorced}} | |||

| * {{marriage|Theresa Ann Lane|1993}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | children = 6, including ] and ] | |||

| | website = {{URL|merlehaggard.com}} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Merle Ronald Haggard''' (April 6, 1937 – April 6, 2016) was an American ] singer, songwriter, guitarist, and ]r. | |||

| '''Merle Ronald Haggard''' (April 6, 1937 – April 6, 2016) was an American ], ], ], ], and ]. Along with ], Haggard and his band ] helped create the ], which is characterized by the twang of ] and the unique mix with the traditional country ] sound, new vocal harmony styles in which the words are minimal, and a rough edge not heard on the more polished ] recordings of the same era. | |||

| Haggard |

Haggard was born in ], toward the end of the ]. His childhood was troubled after the death of his father, and he was incarcerated several times in his youth. After being released from ] in 1960, he managed to turn his life around and launched a successful country music career. He gained popularity with his songs about the working class; these occasionally contained themes contrary to the anti–] sentiment of some popular music of the time. Between the 1960s and the 1980s he had 38 number-one hits on the US country charts, several of which also made the ]. Haggard continued to release successful albums into the 2000s. | ||

| He received many honors and awards for his music, including a ] (2010) |

He received many honors and awards for his music, including a ] (2010); a ] (2006); a ] (2006);<ref name=bmiawards /> and induction into the ] (1977);<ref name=nashvillehof>{{cite web|url=http://nashvillesongwritersfoundation.com.s164288.gridserver.com/Site/inductee?entry_id=2344|title=Merle Haggard|website=]|access-date=April 9, 2016|quote=Induction year: 1977|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150727055941/http://nashvillesongwritersfoundation.com.s164288.gridserver.com/Site/inductee?entry_id=2344|archive-date=July 27, 2015}}</ref> ] (1994)<ref name=countrymusichof>{{cite web|url=http://countrymusichalloffame.org/full-list-of-inductees/view/merle-haggard |title=Full List of Inductees |publisher=Country Music Hall of Fame |date=2010 |access-date=April 16, 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130331231437/http://countrymusichalloffame.org/full-list-of-inductees/view/merle-haggard |archive-date=March 31, 2013}}</ref> and ] (1997).<ref name=okmusichof>{{cite web|url=http://www.omhof.com/Inductees/tabid/56/ItemID/54/Default.aspx|title=Inductees|website=Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame|access-date=April 16, 2013|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130419195117/http://www.omhof.com/Inductees/tabid/56/ItemID/54/Default.aspx|archive-date=April 19, 2013}}</ref> He died on April 6, 2016—his 79th birthday—at his ranch in ], having recently suffered from ].<ref name=nytobit>{{cite news|last=Friskics-Warren|first=Bill|title=Merle Haggard, Country Music's Outlaw Hero, Dies at 79|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/07/arts/music/merle-haggard-country-musics-outlaw-hero-dies-at-79.html?_r=0|newspaper=]|date=April 6, 2016|access-date=April 7, 2016}}</ref> | ||

| ==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

| {{external media | width = 210px | float = right | audio1 = , interviewed by ] on '']'', 42:14, August 14, 1995.<ref name="Fresh Air">{{cite interview |last=Haggard |first=Merle |interviewer=Terry Gross |title=Country Music Legend Merle Haggard |url=https://freshairarchive.org/segments/country-music-legend-merle-haggard-1 |work=] |publisher=] (]) |date=August 14, 1995 |access-date=September 15, 2019}}</ref>}} | |||

| Haggard's parents, Flossie Mae (Harp) and James Francis Haggard,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://merlehaggard.com/bio |title=BIO |publisher=Merlehaggard.com |date= |accessdate=June 2, 2015 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20150626141355/http://merlehaggard.com/bio/ |archivedate=June 26, 2015 }}</ref> moved to California from their home in ], during the Great Depression, after their barn burned in 1934.{{sfn|Cusic, Don|2002|p=XVII}} They settled with their children, Lowell and Lillian, in an apartment in ], while James started working for the ]. A woman who owned a boxcar which was placed in ], a nearby town, asked Haggard's father about the possibility of converting it into a house. He remodeled the boxcar, and soon after moved in, also purchasing the lot, where Merle Ronald Haggard was born on April 6, 1937.{{sfn|Witzel, Michael Karl; Young-Witzel, Gyvel|2007|p=}}{{sfn|Cusic, Don|2002|p=XVIII}} The property was eventually expanded by building a bathroom, a second bedroom, a kitchen, and a breakfast nook in the adjacent lot.{{sfn|Witzel, Michael Karl; Young-Witzel, Gyvel|2007|p=}} | |||

| Haggard's parents were Flossie Mae (née Harp; 1902–1984) and James Francis Haggard (1899–1946).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://merlehaggard.com/bio|title=Haggard bio|publisher=Merlehaggard.com|access-date=June 2, 2015|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150626141355/http://merlehaggard.com/bio|archive-date=June 26, 2015}}</ref> The family moved to California from their home in ], during the Great Depression, after their barn burned in 1934.{{sfn|Cusic|2002|p=XVII}} | |||

| His father died of a brain hemorrhage in 1945,{{sfn|Cusic, Don|2002|p=XVIII}} an event that deeply affected Haggard during his childhood and the rest of his life. To support the family, his mother worked as a bookkeeper.{{sfn|Cusic, Don|2002|p=XX}} At 12, his brother, Lowell, gave him his used guitar. Haggard learned to play alone,{{sfn|Witzel, Michael Karl; Young-Witzel, Gyvel|2007|p=}} with the records he had at home, influenced by ], ], and ].<ref name="CMT"/> As his mother was absent due to work, Haggard became progressively rebellious. His mother sent him for a weekend to a juvenile detention center to change his attitude, but it worsened.{{sfn|Cusic, Don|2002|p=XIX}} | |||

| They settled with their two elder children, James 'Lowell' (1922–1996) and Lillian, in an apartment in ], while James started working for the ]. A woman who owned a ] placed in ], a nearby town, asked Haggard's father about the possibility of converting it into a house. He remodeled the boxcar, and soon after moved in, also purchasing the lot, where Merle Ronald Haggard was born on April 6, 1937.{{sfn|Witzel|Young-Witzel|2007|p=}}{{sfn|Cusic|2002|p=XVIII}} The property was eventually expanded by building a bathroom, a second bedroom, a kitchen, and a breakfast nook in the adjacent lot.{{sfn|Witzel|Young-Witzel|2007|p=}} | |||

| Haggard committed a number of minor offenses, such as thefts and writing bad checks. He was sent to a juvenile detention center for shoplifting in 1950.<ref>{{cite AV media notes| title =Haggard's 40#1| others = Merle Haggard |year =2004|type= CD|publisher=Capitol Records|id=}}</ref> When he was 14, Haggard ran away to Texas with his friend Bob Teague.<ref name="CMT">{{cite web|url=http://www.cmt.com/artists/merle-haggard/biography/|title=About Merle Haggard|work=Country Music Television|publisher=MTV Networks|accessdate=April 5, 2013}}</ref> He ] and ]d throughout the state.{{sfn|Aronowitz, Alfred G.|p=|1968}}{{sfn|Gleason, Holly|1988|p=}} When he returned the same year, he and his friend were arrested for robbery. Haggard and Teague were released when the real robbers were found. Haggard was later sent to the juvenile detention center, from which he and his friend escaped again to ]. He worked a series of laborer jobs, including driving a potato truck, being a short order cook, a hay pitcher, and an ].{{sfn|Aronowitz, Alfred G.|p=|1968}} His debut performance was with Teague in a Modesto bar named "Fun Center", being paid US$5, with free beer.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://m.facebook.com/merlehaggard?v=info&expand=1 |title=Merle Haggard |publisher=M.facebook.com |date=April 6, 1937 |accessdate=June 2, 2015}}</ref> He returned to Bakersfield in 1951, and was again arrested for truancy and ] and sent to a juvenile detention center. After another escape, he was sent to the ], a high-security installation. He was released 15 months later, but was sent back after beating a local boy during a burglary attempt. After his release, Haggard and Teague saw Lefty Frizzell in concert. After hearing Haggard sing along to his songs backstage, Frizzell refused to sing unless Haggard would be allowed to sing first. He sang songs that were well received by the audience. Due to the positive reception, Haggard decided to pursue a career in music. While working as a farmhand or in oil fields, he played in nightclubs. He eventually landed a spot on the local television show ''Chuck Wagon'', in 1956.<ref name="CMT"/> | |||

| In 1946 Haggard's father died of a brain hemorrhage.{{sfn|Cusic|2002|p=XVIII}} Nine-year-old Haggard was deeply affected by the loss, and it remained a pivotal event to him for the rest of his life. To support the family, Haggard's mother took a job as a ].{{sfn|Cusic|2002|p=XX}} Older brother Lowell gave his guitar to Merle when Merle was 12. Haggard learned to play it on his own,{{sfn|Witzel|Young-Witzel|2007|p=}} with the records he had at home, influenced by ], ], and ].<ref name="CMT" /> While his mother was out working during the day Haggard started getting into trouble. She sent him to a juvenile detention center for a weekend to try to correct him, but his behavior did not improve. If anything, he became worse.{{sfn|Cusic|2002|p=XIX}} | |||

| Married and plagued by financial issues,<ref name="CMT"/> he was arrested in 1957 shortly after he tried to rob a Bakersfield roadhouse.{{sfn|Kingsbury, Paul|2004|p=223}} He was sent to Bakersfield Jail,{{sfn|Cusic, Don|2002|p=XX}} and, after an escape attempt, was transferred to ] on February 21, 1958.{{sfn|Cusic, Don|2002|p=XXI}} While in prison, Haggard discovered that his wife was expecting a child from another man, which pressed him psychologically. He was fired from a series of prison jobs, and planned to escape along with another inmate nicknamed "Rabbit". Haggard was convinced not to escape by fellow inmates.{{sfn|Hochman, Steve|p=462|1999}} Haggard started to run a gambling and brewing racket with his cellmate. After he was caught drunk, he was sent for a week to solitary confinement where he encountered ], an author and death row inmate.{{sfn|Erlewine, Stephen Thomas; Bogdanov, Vladimir; Woodstra, Chris|p=|2003}} Meanwhile, "Rabbit" had successfully escaped, only to shoot a police officer and return to San Quentin for execution.{{sfn|Hochman, Steve|p=462|1999}} Chessman's predicament, along with the execution of "Rabbit", inspired Haggard to correct his life.{{sfn|Erlewine, Stephen Thomas; Bogdanov, Vladimir; Woodstra, Chris|p=|2003}} Haggard soon earned a high school equivalency diploma and kept a steady job in the prison's textile plant,{{sfn|Erlewine, Stephen Thomas; Bogdanov, Vladimir; Woodstra, Chris|p=|2003}} while also playing for the prison's country music band,<ref name="bio">{{cite web|url=http://www.biography.com/people/merle-haggard-9542118|title=Merle Haggard biography|work=Biography Channel|publisher=A&E Networks|accessdate=April 5, 2013}}</ref> attributing a 1958 performance by ] at the prison as his main inspiration to join it.<ref name="Haggard Oldies Bio">{{cite web|title=Merle Haggard Biography|author=Attributed to ], ''The Encyclopedia of Popular Music''; 'Licensed by Muze'|url=http://www.oldies.com/artist-biography/Merle-Haggard.html|work=Oldies Biography|publisher=Oldies|accessdate=June 19, 2012}}</ref> He was released from San Quentin on parole in 1960.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0412/16/lkl.01.html | title=A Look at San Quentin | work=CNN | date=December 16, 2004 | accessdate=April 6, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| By the age of 13, Haggard was stealing and writing bad checks.{{clarify|date=December 2021}} In 1950 he was caught shoplifting and sent to a juvenile detention center.<ref>{{cite AV media notes|title=Haggard's 40 #1 Hits|others=Merle Haggard|year=2004|type=CD|publisher=Capitol Records}}</ref> The following year he ran away to Texas with his friend Bob Teague.<ref name="CMT">{{cite web|url=http://www.cmt.com/artists/merle-haggard/biography|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121223065051/http://www.cmt.com/artists/merle-haggard/biography|url-status=dead|archive-date=December 23, 2012|title=About Merle Haggard|work=Country Music Television|publisher=MTV Networks|access-date=April 5, 2013}}</ref> The two ] and ]d throughout the state.{{sfn|Aronowitz|p=|1968}}{{sfn|Gleason|1988|p=}} When they returned later that year the two boys were accused of robbery and sent to jail. This time, they had not actually committed the crime, and were released when the real robbers were found. The experience did not change Haggard much. He was again sent to a juvenile detention center later that year, from which he and his friend escaped and headed to ]. There he worked a series of laborer jobs, including potato truck driver, short order cook, hay pitcher and ].{{sfn|Aronowitz|p=|1968}} His debut performance was with Teague in a Modesto bar named "Fun Center", for which he was paid US$5 and given free beer.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://m.facebook.com/merlehaggard?v=info&expand=1|title=Merle Haggard|publisher=M.facebook.com|date=April 6, 1937|access-date=June 2, 2015}}</ref> | |||

| In 1972, after Haggard had become an established country music star, then-California governor ] granted Haggard a full and unconditional ] for his past crimes.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.rollingstone.com/music/pictures/merle-haggard-the-life-and-times-of-a-badass-legend-20091021/merle-haggard-1972-pardon-from-reagan-5730553 |title=Merle Haggard: The Life and Times of a Badass Legend|publisher=Rolling Stone|date=October 21, 2009|accessdate=April 7, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| In 1951 he returned to Bakersfield, where he was again arrested for ] and ] and sent to a juvenile detention center. After another escape, he was sent to the ], a high-security installation. He was released 15 months later but was sent back after beating a local boy during a burglary attempt. After Haggard's release, he and Teague saw Lefty Frizzell in concert. The two sat backstage, where Haggard began to sing along. Hearing the young man from the stage, Frizzell refused to go on unless Haggard was allowed to sing first. Haggard did, and was well received by the audience. After this experience Haggard decided to pursue a career in music. At night he would sing and play in local bars, while working as a farmhand or in the oil fields during the day. | |||

| ==Early career== | |||

| ] | |||

| Upon his release, Haggard started digging ditches for his brother's electrical contracting company. Soon he was performing again, and later began recording with Tally Records. The Bakersfield Sound was developing in the area as a reaction against the over-produced ] of the ].{{sfn|Cusic, Don|2002|p=XXIII-XXVI}} Haggard's first record for Tally was "Singing My Heart Out" b/w "Skid Row"; it was not a success, and only 200 copies were pressed. In 1962, Haggard wound up performing at a ] show in ] and heard Wynn's "Sing a Sad Song". He asked for permission to record it, and the resulting single was a national hit in 1964. The following year he had his first national top ten record with "]", written by ] (mother of country singer ]) and his career was off and running.{{sfn|Cusic, Don|2002|p=XXVII-XXVIII}} Haggard recalls having been talked into visiting Anderson—a woman he didn't know—at her house to hear her sing some songs she had written. "If there was anything I didn't wanna do, it was sit around some danged woman's house and listen to her cute little songs. But I went anyway. She was a pleasant enough lady, pretty, with a nice smile, but I was all set to be bored to death, even more so when she got out a whole bunch of songs and went over to an old pump organ...There they were. My God, one hit right after another. There must have been four or five number one songs there..."{{sfn|Haggard, Merle, and Peggy Russell|1981}} | |||

| Married and plagued by financial issues,<ref name="CMT" /> in 1957 he tried to rob a Bakersfield ], was caught and arrested.{{sfn|Kingsbury|2004|p=223}} Convicted, he was sent to the Bakersfield Jail.{{sfn|Cusic|2002|p=XX}} After an escape attempt he was transferred to ] on February 21, 1958.{{sfn|Cusic|2002|p=XXI}} There he was prisoner number A45200.<ref>PBS America: Country Music: The Sons and Daughters of America (1964-1968)</ref> While in prison, Haggard learned that his wife was expecting another man's child, which stressed him psychologically. He was fired from a series of prison jobs, and planned to escape along with another inmate nicknamed "Rabbit" (James Kendrick<ref> Crime Scribe.</ref>) but was dissuaded by fellow inmates.{{sfn|Hochman|p=462|1999}} | |||

| In 1966, Haggard recorded "]", also written by Liz Anderson with her husband Casey Anderson, which became his first #1 single.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.rollingstone.com/music/lists/12-most-badass-merle-haggard-prison-songs-20150406/im-a-lonesome-fugitive-20150406 | title=12 Most Badass Merle Haggard Prison Songs | work=Rolling Stone | accessdate=April 6, 2016}}</ref> When the Andersons presented the song to Haggard, they were unaware of his prison stretch.{{sfn|Cantwell, David|2013| p=103}} ], Haggard's backup singer and then-wife, is quoted by music journalist Daniel Cooper in the liner notes to the 1994 retrospective ''Down Every Road'': "I guess I didn't realize how much the experience at San Quentin did to him, 'cause he never talked about it all that much.... I could tell he was in a dark mood...and I said, 'Is everything okay?' And he said, 'I'm really scared.' And I said, 'Why?' And he said, 'Cause I'm afraid someday I'm gonna be out there...and there's gonna be...some prisoner...in there the same time I was in, stand up—and they're gonna be about the third row down—and say, 'What do you think you're doing, 45200?'" Cooper notes that the news had little effect on Haggard's career: "It's unclear when or where Merle first acknowledged to the public that his prison songs were rooted in personal history, for to his credit, he doesn't seem to have made some big splash announcement. In a May 1967 profile in ''Music City News'', his prison record is never mentioned. But in July 1968, in the very same publication, it's spoken of as if it were common knowledge."<ref name="autogenerated1962">{{Cite AV media notes |title=Down Every Road 1962–1994 |title-link=Down Every Road 1962–1994 |others=Merle Haggard |year=1996 |chapter= |url= |access-date= |first=Cooper |last=Daniel |author-link= |type=Liner notes |publisher=] |id= |location= |ref=}}</ref> | |||

| While at San Quentin, Haggard started a gambling and brewing racket with his cellmate. After he was caught drunk, he was sent for a week to solitary confinement where he encountered ], an author and death-row inmate.{{sfn|Erlewine|Bogdanov|Woodstra|p=|2003}} Meanwhile, "Rabbit" had successfully escaped, only to shoot a police officer and be returned to San Quentin for execution.{{sfn|Hochman|p=462|1999}} Chessman's predicament, along with the execution of "Rabbit", inspired Haggard to change his life.{{sfn|Erlewine|Bogdanov|Woodstra|p=|2003}} He soon earned a high school equivalency diploma and kept a steady job in the prison's textile plant.{{sfn|Erlewine|Bogdanov|Woodstra|p=|2003}} He also played for the prison's country music band.<ref name="bio">{{cite web|url=http://www.biography.com/people/merle-haggard-9542118|title=Merle Haggard biography|work=Biography Channel|publisher=A&E Networks|access-date=April 5, 2013}}</ref> He also attended a ] concert at the prison in 1958. Cash sang his song "]" (1956) and "had a profound influence on the young inmate, who upon release set out on forging a career as a singer-songwriter".<ref name=RS15/> Haggard was released from San Quentin on parole in 1960.<ref>{{cite web |title=A Look at San Quentin |url=http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0412/16/lkl.01.html |publisher=CNN |date=December 16, 2004 |access-date=April 6, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| The 1966 album ''Branded Man'' kicked off an artistically and commercially successful run for Haggard. In 2013 Haggard biographer David Cantwell stated, "The immediate successors to ''I'm a Lonesome Fugitive'' — ''Branded Man'' in 1967 and, in '68, '']'' and '']'' — were among the finest albums of their respective years."{{sfn|Cantwell, David|2013| p=125}} Haggard's new recordings largely centered around ]'s ], ]'s ], and the harmony vocals provided by Bonnie Owens. At the time of Haggard's first top-ten hit "]" in 1965, Owens (who had formerly been married to ]) was known as a solo performer, a fixture on the ] club scene who had appeared on television. She won the new ]'s first ever award for Female Vocalist after her 1965 debut album, ''Don't Take Advantage of Me'', hit the top five on the country albums chart. However, Bonnie Owens had no further hit singles, and although she recorded six solo albums on Capitol between 1965 and 1970, she became mainly known for her background harmonies on Haggard hits like "]" and "Branded Man".<ref>{{Cite AV media notes |title=Queen of the Coast |year=2007 |url=http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:YtE-flYnRzYJ:www.dekedickerson.com/docs/DekeDickerson-BonnieOwens.doc+&cd=10&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us |first=Deke |last=Dickerson |type=Liner notes |others=]|publisher=Bear Family Records |location=Germany}}</ref> | |||

| In 1972, after Haggard had become an established country music star, then-California governor ] granted Haggard a full and unconditional ] for his past crimes.<ref>{{cite magazine|url=https://www.rollingstone.com/music/pictures/merle-haggard-the-life-and-times-of-a-badass-legend-20091021/merle-haggard-1972-pardon-from-reagan-5730553 |title=Merle Haggard: The Life and Times of a Badass Legend|magazine=Rolling Stone|date=October 21, 2009|access-date=April 7, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Producer Ken Nelson took a hands-off approach to producing Haggard. In the episode of '']'' dedicated to him, Haggard remembers: "The producer I had at that time, Ken Nelson, was an exception to the rule. He called me 'Mr. Haggard' and I was a little twenty-four, twenty-five year old punk from Oildale...He gave me complete responsibility. I think if he'd jumped in and said, 'Oh, you can't do that,' it would've destroyed me."<ref name=AmericanMasters>{{Cite episode |title=Merle Haggard: Learning to Live With Myself |url=http://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/merle-haggard-learning-to-live-with-myself/1545/ |access-date=April 7, 2016 |series=American Masters |series-link=American Masters |first=Merle |last=Haggard |network=] |date=July 21, 2010| language=English }}</ref> In the documentary series ''Lost Highway'', Nelson recalls, "When I first started recording Merle, I became so enamored with his singing that I would forget what else was going on, and I suddenly realized, 'Wait a minute, there's musicians here you've got to worry about!' But his songs—he was a great writer."<ref>{{Cite episode |title=Beyond Nashville |episode-link=|url= |access-date= |series=Lost Highway: The History of American Country |series-link= |first=Ken |last=Nelson |network=] |station= |date=March 8, 2003 |season=1 |series-no= |number=3 |minutes= |time= |transcript= |transcript-url= |language=English}}</ref> | |||

| ==Career== | |||

| Towards the end of the decade, Haggard composed several number 1 hits including "]", "The Legend of Bonnie and Clyde", "Hungry Eyes", and "Sing Me Back Home".{{sfn|Cantwell, David|2013| p=125}} Daniel Cooper calls "Sing Me Back Home", "a ballad that works on so many different levels of the soul it defies one's every attempt to analyze it."<ref name="autogenerated1962"/> In a 1977 interview in '']'' with ], Haggard reflected, "Even though the crime was brutal and the guy was an incorrigible criminal, it's a feeling you never forget when you see someone you know make that last walk. They bring him through the yard, and there's a guard in front and a guard behind—that's how you know a death prisoner. They brought Rabbit out...taking him to see the Father,...prior to his execution. That was a strong picture that was left in my mind." In 1968, Haggard's first tribute LP '']'', was also released to acclaim. | |||

| ===Early career=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Upon his release from San Quentin in 1960, Haggard started digging ditches for his brother's electrical contracting company. Soon, he was performing again and later began recording with Tally Records. The ] was developing in the area as a reaction against the overproduced ].{{sfn|Cusic|2002|pp=XXIII–XXVI}} Haggard's first record for Tally was "Singing My Heart Out" backed by "Skid Row"; it was not a success, and only 200 copies were pressed. In 1962, Haggard wound up performing at a ] show in ] and heard Wynn's "Sing a Sad Song". He asked for permission to record it, and the resulting single was a national hit in 1964. The following year, he had his first national top-10 record with "]," written by ], mother of country singer ], and his career was off and running.{{sfn|Cusic|2002|pp=XXVII–XXVIII}} Haggard recalls having been talked into visiting Anderson—a woman he did not know—at her house to hear her sing some songs she had written. "If there was anything I didn't wanna do, it was sit around some danged woman's house and listen to her cute little songs. But I went anyway. She was a pleasant enough lady, pretty, with a nice smile, but I was all set to be bored to death, even more so when she got out a whole bunch of songs and went over to an old pump organ.... There they were. My God, one hit right after another. There must have been four or five number one songs there...."{{sfn|Haggard|Russell|1981}} | |||

| In 1967, Haggard recorded "]" with ], also written by Liz Anderson, with her husband Casey Anderson, which became his first number-one single.<ref name=RS15>{{cite magazine|url=https://www.rollingstone.com/music/lists/12-most-badass-merle-haggard-prison-songs-20150406/im-a-lonesome-fugitive-20150406|title=12 Most Badass Merle Haggard Prison Songs|magazine=Rolling Stone|date=April 6, 2015|access-date=April 6, 2016}}</ref> When the Andersons presented the song to Haggard, they were unaware of his prison stretch.{{sfn|Cantwell|2013|p=103}} ], Haggard's backup singer and then-wife, is quoted by music journalist Daniel Cooper in the liner notes to the 1994 retrospective ''Down Every Road'': "I guess I didn't realize how much the experience at San Quentin did to him, 'cause he never talked about it all that much ... I could tell he was in a dark mood ... and I said, 'Is everything okay?' And he said, 'I'm really scared.' And I said, 'Why?' And he said, 'Cause I'm afraid someday I'm gonna be out there ... and there's gonna be ... some prisoner ... in there the same time I was in, stand up—and they're gonna be about the third row down—and say, 'What do you think you're doing, 45200?'" Cooper notes that the news had little effect on Haggard's career: "It's unclear when or where Merle first acknowledged to the public that his prison songs were rooted in personal history, for to his credit, he doesn't seem to have made some big splash announcement. In a May 1967 profile in ''Music City News'', his prison record is never mentioned, but in July 1968, in the very same publication, it's spoken of as if it were common knowledge."<ref name="autogenerated1962">{{Cite AV media notes |title=Down Every Road 1962–1994 |title-link=Down Every Road 1962–1994 |others=Merle Haggard |year=1996 |first=Cooper |last=Daniel |type=Liner notes |publisher=] }}</ref> | |||

| Haggard's songs attracted attention from outside the country field. ] covered both "Sing Me Back Home" and "Mama Tried" on their 1968 country-rock album '']''. The following year, Haggard's songs were performed and/or recorded by a variety of artists, including the ] incarnation of the ], who performed "]" on the ] and recorded "Life in Prison" for their album '']''; singer-activist ], who covered "Sing Me Back Home" and "Mama Tried"; crooner ], who recorded "I Take a Lot of Pride in What I Am" for his album of the same name; and the ], whose live cover of "Mama Tried" became a staple in their repertoire until the band's end in 1995. In the original '']'' review for Haggard's 1968 album ''Mama Tried'', Andy Wickham wrote, "His songs romanticize the hardships and tragedies of ]'s transient proletarian and his success is resultant of his inherent ability to relate to his audience a commonplace experience with precisely the right emotional pitch...Merle Haggard looks the part and sounds the part because he is the part. He's great." | |||

| The 1967 album ''Branded Man'' with ] kicked off an artistically and commercially successful run for Haggard. In 2013, Haggard biographer David Cantwell stated, "The immediate successors to ''I'm a Lonesome Fugitive''—''Branded Man'' in 1967 and, in '68, '']'' and '']''—were among the finest albums of their respective years."{{sfn|Cantwell|2013|p=125}} Haggard's new recordings showcased his band the Strangers, specifically ]'s ], ]'s ], and the harmony vocals provided by ]. | |||

| =="Okie from Muskogee" and "The Fightin' Side of Me"== | |||

| At the time of Haggard's first top-10 hit "]" in 1965, Owens, who had been married to ], was known as a solo performer, a fixture on the ] club scene and someone who had appeared on television. She won the new ]'s first ever award for Female Vocalist after her 1965 debut album, ''Don't Take Advantage of Me'', hit the top five on the country albums chart. However, Bonnie Owens had no further hit singles, and although she recorded six solo albums on Capitol between 1965 and 1970, she became mainly known for her background harmonies on Haggard hits such as "]" and "Branded Man".<ref>{{Cite AV media notes|title=Queen of the Coast |year=2007 |url=http://www.dekedickerson.com/docs/DekeDickerson-BonnieOwens.doc |first=Deke |last=Dickerson |type=Liner notes |others=] |publisher=Bear Family Records |location=Germany |url-status=bot: unknown |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160207091721/http://www.dekedickerson.com/docs/DekeDickerson-BonnieOwens.doc |archive-date=February 7, 2016 }}</ref> | |||

| In 1969, Haggard released "]", with lyrics ostensibly reflecting the singer's pride in being from ] where people are considered patriotic, do not smoke ], take ], ] or ].<ref>Malone, Bill, ''Country Music U.S.A'', 2nd rev. ed. (University of Texas Press, Austin, 2002), p. 371.</ref> In the ensuing years, Haggard gave varying statements regarding whether he intended the song as a humorous satire or a serious political statement in support of conservative values.<ref>{{cite news |last=Chilton |first=Martin |date=April 7, 2016 |title=Merle Haggard: 'Sometimes I Wish I Hadn't Written Okie from Muskogee' |url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/music/artists/merle-haggard-sometimes-i-wish-i-hadnt-written-okie-from-muskoge/ |newspaper=] |location=London |access-date=April 7, 2016 }}</ref> In a 2001 interview, Haggard called the song a "documentation of the uneducated that lived in America at the time".{{sfn|Fox, Aaron A.|2004|p=51}} However, he made several other statements suggesting that he meant the song seriously. On the '']'', he said, "I wrote it when I recently got out of the joint. I knew what it was like to lose my freedom, and I was getting really mad at these protesters. They didn't know anything more about the war in Vietnam than I did. I thought how my dad, who was from Oklahoma, would have felt. I felt I knew how those boys fighting in Vietnam felt."<ref name=kaufman>{{cite book |last=Kaufman |first=Will |date=2009 |title=American Culture in the 1970s |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8vCqBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA116#v=onepage&q&f=false |publisher=Edinburgh University Press |pages=115–116 |isbn=9780748621422}}</ref> In the country music documentary series ''Lost Highway'', he elaborated: "My dad passed away when I was nine, and I don't know if you've ever thought about somebody you've lost and you say, 'I wonder what so-and-so would think about this?' I was drivin' on ] and I saw a sign that said "19 Miles to Muskogee". Muskogee was always referred to in my childhood as 'back home'. So I saw that sign and my whole childhood flashed before my eyes and I thought, 'I wonder what dad would think about the youthful uprising that was occurring at the time, the ]s...I understood 'em, I got along with it, but what if he was to come alive at this moment? And I thought, what a way to describe the kind of people in America that are still sittin' in the center of the country sayin', 'What is goin' on on these campuses?'"<ref>{{Cite episode |title=Beyond Nashville |episode-link=|url= |access-date= |series=Lost Highway: The History of American Country |series-link= |first=Merle |last=Haggard |network=] |station= |date=March 8, 2003 |season=1 |series-no= |number=3 |minutes= |time= |transcript= |transcript-url= |language=English}}</ref> In the '']'' documentary about him, he said, "That's how I got into it with the hippies...I thought they were unqualified to judge America, and I thought they were lookin' down their noses at something that I cherished very much, and it pissed me off. And I thought, 'You sons of bitches, you've never been restricted away from this great, wonderful country, and yet here you are in the streets bitchin' about things, protesting about a war that they didn't know any more about than I did. They weren't over there fightin' that war any more than I was."<ref name=AmericanMasters /> | |||

| Producer Ken Nelson took a hands-off approach to produce Haggard. In the episode of '']'' dedicated to him, Haggard remembers: "The producer I had at that time, Ken Nelson, was an exception to the rule. He called me 'Mr. Haggard' and I was a little twenty-four, twenty-five-year-old punk from Oildale... He gave me complete responsibility. I think if he'd jumped in and said, 'Oh, you can't do that,' it would've destroyed me."<ref name=AmericanMasters>{{Cite episode |title=Merle Haggard: Learning to Live With Myself|url=https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/merle-haggard-learning-to-live-with-myself/1545|access-date=April 7, 2016|series=American Masters|series-link=American Masters|first=Merle|last=Haggard|network=]|date=July 21, 2010}}</ref> In the documentary series ''Lost Highway'', Nelson recalls, "When I first started recording Merle, I became so enamored with his singing that I would forget what else was going on, and I suddenly realized, 'Wait a minute, there's musicians here you've got to worry about!' But his songs—he was a great writer."<ref>{{Cite episode|title=Beyond Nashville|series=Lost Highway: The History of American Country|first=Ken|last=Nelson|network=]|date=March 8, 2003|season=1|number=3}}</ref> | |||

| Haggard began performing the song in concert in 1969 and was astounded at the reaction it received. | |||

| Towards the end of the decade, Haggard composed several number-one hits, including "]," "The Legend of Bonnie and Clyde," "Hungry Eyes," and "Sing Me Back Home".{{sfn|Cantwell|2013|p=125}} Daniel Cooper calls "Sing Me Back Home" "a ballad that works on so many different levels of the soul it defies one's every attempt to analyze it".<ref name="autogenerated1962" /> In a 1977 interview in '']'' with ], Haggard reflected, "Even though the crime was brutal and the guy was an incorrigible criminal, it's a feeling you never forget when you see someone you know make that last walk. They bring him through the yard, and there's a guard in front and a guard behind—that's how you know a death prisoner. They brought Rabbit out ... taking him to see the Father, ... prior to his execution. That was a strong picture that was left in my mind." In 1969, Haggard's first tribute LP '']'', was also released to acclaim. | |||

| {{Pull quote|The Haggard camp knew they were on to something. Everywhere they went, every show, 'Okie' did more than prompt enthusiastic applause. There was an unanticipated adulation racing through the crowds now, standing ovations that went on and on and sometimes left the audience and the band-members alike teary-eyed. Merle had somehow stumbled upon a song that expressed previously inchoate fears, spoke out loud gripes and anxieties otherwise only whispered, and now people were using his song, were using ''him'', to connect themselves to these larger concerns and to one another.{{sfn|Cantwell, David|2013|page=151}}}} | |||

| In the 1969 '']'' review for Haggard and the Strangers 1968 album ''Mama Tried'', ] wrote, "His songs romanticize the hardships and tragedies of America's transient proletarian and his success is resultant of his inherent ability to relate to his audience a commonplace experience with precisely the right emotional pitch.... Merle Haggard looks the part and sounds the part because he is the part. He's great."<ref>{{cite magazine |url=https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-album-reviews/mama-tried-186689/ |title=Mama Tried |last=Wickham |first=Andy |author-link=Andy Wickham |date=March 1969 |magazine=] |access-date=February 12, 2023}}</ref> | |||

| The studio version, which was mellower than the usually raucous live concert versions, topped the country charts in 1969, where it remained for a month.{{sfn|Cantwell, David|2013|page=152}} It also hit number 41 on the ''Billboard'' all-genre singles chart, becoming Haggard's biggest hit up to that time (surpassed only by his 1973 crossover ] hit, "]", which peaked at number 28)<ref name=haggardsongdb>{{cite web |url=http://www.song-database.com/artist.php?aid=1359 |title=Merle Haggard (artist page) |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |date= |website=Song-Database.com |publisher=Song://Database |access-date=April 7, 2016 |quote=}}</ref><ref name=hagbillboardchartp1 /> and signature song.<ref>{{cite web |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |title=Top 10 Merle Haggard Songs |url=http://tasteofcountry.com/merle-haggard-songs/ |website=Tasteofcountry.com |publisher=]|date= |access-date=April 7, 2016 |deadurl=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160103032651/http://tasteofcountry.com/merle-haggard-songs/ |archive-date=January 3, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ==="Okie from Muskogee" and "The Fightin' Side of Me"=== | |||

| On his next single, "]" (released in 1970 over Haggard's objections by his record company), Haggard's lyrics stated that he did not mind the counterculture "switchin' sides and standin' up for what they believe in" but resolutely declared, "If you don't love it, leave it!" In May 1970, Haggard explained to John Grissom of '']'', "I don't like their views on life, their filth, their visible self-disrespect, y'know. They don't give a shit what they look like or what they smell like...What do they have to offer humanity?"{{sfn|Cantwell, David|2013|p=154}} In a 2003 interview with '']'' magazine, Haggard said, "I had different views in the '70s. As a human being, I've learned . I have more culture now. I was dumb as a rock when I wrote 'Okie From Muskogee'. That's being honest with you at the moment, and a lot of things that I said I sing with a different intention now. My views on marijuana have totally changed. I think we were brainwashed and I think anybody that doesn't know that needs to get up and read and look around, get their own information. It's a cooperative government project to make us think marijuana should be outlawed."<ref>{{cite web|last=McLenan |first=Andy |url=http://nodepression.com/article/merle-haggard-branded-man |title=Merle Haggard – Branded man |publisher=nodepression.com |date=October 31, 2003 |accessdate=April 6, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| In 1969, Haggard and the Strangers released "]," with lyrics ostensibly reflecting the singer's pride in being from ], where people are conventionally patriotic and traditionally conservative.<ref>Malone, Bill, ''Country Music U.S.A'', 2nd rev. ed. (University of Texas Press, Austin, 2002), p. 371.</ref> American president ] wrote an appreciative letter to Haggard upon his hearing of the song, and would go on to invite Haggard to perform at the White House several times.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Berlau |first=John |date=1996-08-19 |title=The battle over "Okie from Muskogee" |url=https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/the-battle-over-quotokie-from-muskogee |access-date=2023-10-22 |website=Washington Examiner |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Troy |first=Tevi |date=2016-04-07 |title=When Merle Haggard Played at the Nixon White House |url=https://observer.com/2016/04/when-merle-haggard-played-at-the-nixon-white-house/ |access-date=2023-10-22 |website=Observer |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| In the ensuing years, Haggard gave varying statements regarding whether he intended the song as a humorous satire or a serious political statement in support of conservative values.<ref>{{cite news |last=Chilton |first=Martin |date=April 7, 2016 |title=Merle Haggard: 'Sometimes I Wish I Hadn't Written Okie from Muskogee' |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/music/artists/merle-haggard-sometimes-i-wish-i-hadnt-written-okie-from-muskoge/ |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220111/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/music/artists/merle-haggard-sometimes-i-wish-i-hadnt-written-okie-from-muskoge/ |archive-date=January 11, 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |newspaper=] |location=London |access-date=April 7, 2016 }}{{cbignore}}</ref> In a 2001 interview, Haggard called the song a "documentation of the uneducated that lived in America at the time".{{sfn|Fox|2004|p=51}} However, he made several other statements suggesting that he meant the song seriously. On the '']'', he said, "I wrote it when I recently got out of the joint. I knew what it was like to lose my freedom, and I was getting really mad at these protesters. They didn't know anything more about the war in Vietnam than I did. I thought how my dad, who was from Oklahoma, would have felt. I felt I knew how those boys fighting in Vietnam felt."<ref name=kaufman>{{cite book |last=Kaufman |first=Will |date=2009 |title=American Culture in the 1970s |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8vCqBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA116 |publisher=Edinburgh University Press |pages=115–116 |isbn=9780748621422}}</ref> In the country music documentary series ''Lost Highway'', he elaborated: "My dad passed away when I was nine, and I don't know if you've ever thought about somebody you've lost and you say, 'I wonder what so-and-so would think about this?' I was drivin' on ] and I saw a sign that said '19 Miles to Muskogee', while at the same time listening to radio shows of '']'' hosted by ].<ref name="Chapelle2007">{{cite book|first=Peter |last=La Chapelle|title=Proud to Be an Okie: Cultural Politics, Country Music, and Migration to Southern California|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sbkwDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA192|date=3 April 2007|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-24889-2|page=192}}</ref> Muskogee was always referred to in my childhood as 'back home.' So I saw that sign and my whole childhood flashed before my eyes and I thought, 'I wonder what dad would think about the youthful uprising that was occurring at the time, the ]s.... I understood 'em, I got along with it, but what if he was to come alive at this moment? And I thought, what a way to describe the kind of people in America that are still sittin' in the center of the country sayin', 'What is goin' on on these campuses?'", as it was the subject of this Garner Ted Armstrong radio program. "And a week or so later, I was listening to Garner Ted Armstrong, and Armstrong was saying how the smaller colleges in smaller towns don't seem to have any problems. And I wondered if Muskogee had a college, and it did, and they hadn't had any trouble - no racial problems and no dope problems. The whole thing hit me in two minutes, and I did one line after another and got the whole thing done in 20 minutes."<ref name="Chapelle2007" /><ref>{{Cite episode |title=Beyond Nashville |series=Lost Highway: The History of American Country |first=Merle |last=Haggard |network=] |date=March 8, 2003 |season=1 |number=3 |language=en}}</ref> In the '']'' documentary about him, he said, "That's how I got into it with the hippies.... I thought they were unqualified to judge America, and I thought they were lookin' down their noses at something that I cherished very much, and it pissed me off. And I thought, 'You sons of bitches, you've never been restricted away from this great, wonderful country, and yet here you are in the streets bitchin' about things, protesting about a war that they didn't know any more about than I did. They weren't over there fightin' that war any more than I was."<ref name=AmericanMasters /> | |||

| Ironically, Haggard had wanted to follow "Okie from Muskogee" with "Irma Jackson", a song that dealt with an interracial romance between a white man and an African-American woman. His producer, ], discouraged him from releasing it as a single.<ref name="autogenerated1962"/> Jonathan Bernstein recounts, "Hoping to distance himself from the harshly right-wing image he had accrued in the wake of the hippie-bashing 'Muskogee', Haggard wanted to take a different direction and release "Irma Jackson" as his next single... When the Bakersfield, California native brought the song to his record label, executives were reportedly appalled. In the wake of 'Okie', Capitol Records was not interested in complicating Haggard's conservative, blue-collar image."<ref>{{cite web|last=Bernstein |first=Jonathan |url=http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/flashback-merle-haggard-reluctantly-unveils-the-fightin-side-of-me-20141223 |title=Flashback: Merle Haggard Records the 'The Fightin' Side of Me' |publisher=Rollingstone.com |date=December 23, 2014 |accessdate=June 2, 2015}}</ref> After "The Fightin' Side of Me" was released instead, Haggard later commented to the '']'', "People are narrow-minded. Down South they might have called me a nigger lover."{{sfn|Cantwell, David|2013|p=162}} In a 2001 interview, Haggard stated that Nelson, who was also head of the country division at Capitol at the time, never interfered with his music but "this one time he came out and said, 'Merle...I don't believe the world is ready for this yet'... And he might have been right. I might've canceled out where I was headed in my career."<ref name="autogenerated1962" /><ref>{{cite magazine| last = Bernstein | first = Jonathan | title = Flashback: Merle Haggard Reluctantly Unveils 'The Fightin' Side of Me'| magazine = Rolling Stone|date = December 23, 2014| url = http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/flashback-merle-haggard-reluctantly-unveils-the-fightin-side-of-me-20141223| accessdate = April 7, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Haggard began performing the song in concert in 1969 and was astounded at the reaction it received: | |||

| "Okie From Muskogee", "The Fightin' Side of Me", and "I Wonder If They Think of Me" (Haggard's 1973 song about an American ] in Vietnam) were hailed as anthems of the ] and have been recognized as part of a recurring patriotic trend in American country music that also includes ]' "In America" and ]'s "]".<ref>{{cite news |last=Edwards |first=Joe |date=November 7, 1985 |title=Country Music Salutes Old Glory |url=http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1985-11-07/features/8503160978_1_official-song-patriotic-country-music |newspaper=] |location= |access-date=April 7, 2016 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=Dickinson |first=Chris |date=December 19, 2001 |title=Response to Sept. 11 a Natural for Country Singers |url=http://articles.latimes.com/2001/dec/19/entertainment/et-dickinson19 |newspaper=] |location= |access-date=April 7, 2016 }}</ref> Although ] of ''Broadside'' magazine criticized Haggard for his " Birch-type songs against war dissenters", Haggard was popular with college students in the early 1970s, due not only to ironic use of his songs by ] members, but also because his music was recognized as coming from an early country-folk tradition. Both "Okie from Muskogee" and "The Fightin' Side of Me" received extensive airplay on underground radio stations, and "Okie" was performed in concert by ]s ] and ].<ref name=kaufman /> | |||

| {{blockquote|The Haggard camp knew they were on to something. Everywhere they went, every show, "Okie" did more than prompt enthusiastic applause. There was an unanticipated adulation racing through the crowds now, standing ovations that went on and on and sometimes left the audience and the band members alike teary-eyed. Merle had somehow stumbled upon a song that expressed previously inchoate fears, spoke out loud gripes and anxieties otherwise only whispered, and now people were using his song, were using "him," to connect themselves to these larger concerns and to one another.{{sfn|Cantwell|2013|page=151}}}} | |||

| ==Later career== | |||

| The studio version, which was mellower than the usually raucous live-concert versions, topped the country charts in 1969 and remained there for a month.{{sfn|Cantwell|2013|page=152}} It also hit number 41 on the ''Billboard'' all-genre singles chart, becoming Haggard's biggest hit up to that time, surpassed only by his 1973 crossover Christmas hit, "]," which peaked at number 28.<ref name=hagbillboardchartp1 /> "Okie from Muskogee" is also generally described as Haggard's ].<ref>{{cite web|title=Top 10 Merle Haggard Songs|url=http://tasteofcountry.com/merle-haggard-songs|website=Tasteofcountry.com|publisher=]|access-date=April 7, 2016|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160103032651/http://tasteofcountry.com/merle-haggard-songs|archive-date=January 3, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| On his next single, "]," released by his record company in 1970 over Haggard's objections, Haggard's lyrics stated that he did not mind the counterculture "switchin' sides and standin' up for what they believe in," but resolutely declared, "If you don't love it, leave it!" In May 1970, Haggard explained to John Grissom of '']'', "I don't like their views on life, their filth, their visible self-disrespect, y'know. They don't give a shit what they look like or what they smell like.... What do they have to offer humanity?"{{sfn|Cantwell|2013|p=154}} In a 2003 interview with '']'' magazine, Haggard said, "I had different views in the '70s. As a human being, I've learned . I have more culture now. I was dumb as a rock when I wrote 'Okie From Muskogee.' That's being honest with you at the moment, and a lot of things that I said I sing with a different intention now. My views on marijuana have totally changed. I think we were brainwashed and I think anybody that doesn't know that needs to get up and read and look around, get their own information. It's a cooperative government project to make us think marijuana should be outlawed."<ref>{{cite web|last=McLenan|first=Andy|url=http://nodepression.com/article/merle-haggard-branded-man|title=Merle Haggard – Branded man|publisher=nodepression.com|date=October 31, 2003|access-date=April 6, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Haggard's LP '']'', dedicated to ], helped spark a permanent revival and expanded audience for ].<ref name=Hicks /><ref name =WillsCMT /> By this point, Haggard was one of the most famous country singers in the world, having enjoyed an immensely successful artistic and commercial run with Capitol, accumulating twenty-four number 1 country singles since 1966. | |||

| Haggard had wanted to follow "Okie from Muskogee" with "]," a song that dealt with an interracial romance between a white man and an African American woman. His producer, ], discouraged him from releasing it as a single.<ref name="autogenerated1962" /> Jonathan Bernstein recounts, "Hoping to distance himself from the harshly right-wing image he had accrued in the wake of the hippie-bashing "Muskogee," Haggard wanted to take a different direction and release "Irma Jackson" as his next single.... When the Bakersfield, California, native brought the song to his record label, executives were reportedly appalled. In the wake of "Okie," Capitol Records was not interested in complicating Haggard's conservative, blue-collar image."<ref name=RS>{{cite magazine|last=Bernstein|first=Jonathan|title=Flashback: Merle Haggard Reluctantly Unveils 'The Fightin' Side of Me'|magazine=Rolling Stone|date=December 23, 2014| url=https://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/flashback-merle-haggard-reluctantly-unveils-the-fightin-side-of-me-20141223| access-date = April 7, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| In 1972, ''Let Me Tell You about A Song'', the first TV special starring Haggard, was nationally syndicated by Capital Cities TV Productions. It was a semi-autobiographical musical profile of Haggard, akin to the contemporary ''Behind The Music'', produced and directed by Michael Davis. The 1973 ] anthem, "]", furthered Haggard's status as a champion of the working class. "If We Make It Through December" turned out to be Haggard's last crossover pop hit.<ref name=haggardsongdb /> | |||

| After "The Fightin' Side of Me" was released, instead, Haggard later commented to '']'', "People are narrow-minded. Down South they might have called me a nigger lover."{{sfn|Cantwell|2013|p=162}} In a 2001 interview, Haggard stated that Nelson, who was also head of the country division at Capitol at the time, never interfered with his music, but "this one time he came out and said, 'Merle, I don't believe the world is ready for this yet.' ... And he might have been right. I might've canceled out where I was headed in my career."<ref name="autogenerated1962" /><ref name=RS /> | |||

| Haggard appeared on the cover of ''TIME'' on May 6, 1974.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19740506,00.html|title=TIME magazine cover|date=May 6, 1974|website=content.time.com|publisher=TIME|accessdate=April 7, 2016}}</ref> He also wrote and performed the theme song to the television series '']'', which in 1975 gave him another ].{{sfn|Whitburn, Joel|2006| p=147}} During the early to mid-1970s, Haggard's country chart domination continued with songs like "Someday We'll Look Back", "]", "]", and "]". Between 1973 and 1976, he scored nine consecutive number 1 country hits. In 1977, he switched to ] and began exploring the themes of depression, alcoholism, and middle age on albums such as '']'' and '']''. Haggard sang a duet cover of ]'s "What's A Little Love Between Friends" with ] in her 1980 television music special, ''Lynda Carter: Encore!'' He also scored a number 1 hit in 1980 with "]", a duet with actor ] that appeared on the '']'' soundtrack. | |||

| "Okie From Muskogee," "The Fightin' Side of Me," and "I Wonder If They Think of Me" (Haggard's 1973 song about an American ] in Vietnam) were hailed as anthems of the ], and have been recognized as part of a recurring patriotic trend in American country music that also includes ]' "In America" and ]'s "]".<ref>{{cite news|last=Edwards|first=Joe|date=November 7, 1985|title=Country Music Salutes Old Glory|url=https://www.chicagotribune.com/1985/11/07/country-music-salutes-old-glory/|newspaper=]|access-date=April 7, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Dickinson|first=Chris|date=December 19, 2001|title=Response to Sept. 11 a Natural for Country Singers|url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2001-dec-19-et-dickinson19-story.html|newspaper=]|access-date=April 7, 2016}}</ref> Although ] of ''Broadside'' magazine criticized Haggard for his "</nowiki> Birch–type]] songs against war dissenters," Haggard was popular with college students in the early 1970s, not only because of the ironic use of his songs by ] members, but also because his music was recognized as coming from an early country-folk tradition. Both "Okie from Muskogee" and "The Fightin' Side of Me" received extensive airplay on underground radio stations, and "Okie" was performed in concert by ]s ] and ].<ref name=kaufman /> | |||

| Haggard appeared in an episode of '']'' entitled "The Comeback", season 5, episode 3, original air-date October 10, 1976. He played a band leader named Red, who had been depressed since the death of his son (Ron Howard).{{citation needed|date=April 2016}} | |||

| ===Later career=== | |||

| In 1981, Haggard published an autobiography, ''Sing Me Back Home''. The same year, he alternately spoke and sang the ballad "The Man in the Mask". Written by ] (whose other work includes "]", "]", "]", "]", and the musical '']''), this was the combined narration and theme for the movie '']'', a box-office flop. Haggard also changed record labels again in 1981, moving to Epic and releasing one of his most critically acclaimed albums, ''Big City''. | |||

| ] | |||

| Haggard's 1970 LP '']'', dedicated to ], helped spark a permanent revival and expanded the audience for ].<ref name=Hicks /><ref name =WillsCMT /> By this point, Haggard was one of the most famous country singers in the world, having enjoyed an immensely successful artistic and commercial run with Capitol, accumulating 24 number-one country singles since 1966. | |||

| Between 1981 and 1985, Haggard scored twelve more Top 10 country hits, with nine of them reaching number 1, including "My Favorite Memory," "Going Where the Lonely Go," "Someday When Things Are Good," and "Natural High." In addition, Haggard recorded two chart-topping duets with ] ("Yesterdays' Wine" in 1982) and ] ("Pancho and Lefty" in 1983). Nelson believed the 1983 ]-winning film '']'', about the life of fictional singer Mac Sledge, was based on the life of Merle Haggard. Actor ] and other filmmakers denied this and claimed the character was based on nobody in particular. Duvall, however, said he was a big fan of Haggard.<ref>{{Cite AV media|people=] (actor), Gary Hertz (director)|date=April 16, 2002|title= Miracles & Mercies|url= http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0383509/ |medium=Documentary|publisher=] |location=]|accessdate=January 28, 2008}}</ref> | |||

| In 1972, ''Let Me Tell You about A Song'', the first TV special starring Haggard, was nationally syndicated by Capital Cities TV Productions. It was a semi-autobiographical musical profile of Haggard, akin to the contemporary ''Behind the Music'', produced and directed by Michael Davis. The 1973 ] anthem, "]," furthered Haggard's status as a champion of the working class. "If We Make It Through December" turned out to be Haggard and the Strangers' final crossover pop hit. | |||

| In 1983, Haggard and his third wife Leona Williams divorced after five stormy years of marriage. The split served as a license to party for Haggard, who spent much of the next decade becoming mired in alcohol and drug problems.<ref name=heath/>{{sfn|Cantwell, David|2013| p=230}} Haggard has stated that he was in the stages of his own ], or "male menopause," around this time. He said in an interview from this period: "Things that you've enjoyed for years don't seem nearly as important, and you're at war with yourself as to what's happening. 'Why don't I like that anymore? Why do I like this now?' And finally, I think you actually go through a biological change, you just, you become another...Your body is getting ready to die and your mind doesn't agree."<ref name=AmericanMasters /> He was briefly a heavy user of cocaine, but managed to kick the habit.<ref name=heath /> Despite these issues, he won a ] for his 1984 remake of "]." | |||

| Haggard appeared on the cover of ''TIME'' on May 6, 1974.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19740506,00.html|title=TIME magazine cover|date=May 6, 1974|website=]|publisher=TIME|access-date=April 7, 2016}}</ref> He also wrote and performed the theme song to the television series '']'', which in 1975 gave him and the Strangers another ].{{sfn|Whitburn|2006| p=147}} During the early-to-mid-1970s, Haggard and the Strangers country chart domination continued with songs such as "Someday We'll Look Back," "]," "]," and "]". Between 1973 and 1976, he and the Strangers scored nine consecutive number-one country hits. In 1977, he switched to ] and began exploring the themes of depression, alcoholism, and middle age on albums such as '']'' and '']''. Haggard sang a duet cover of ]'s "What's A Little Love Between Friends" with ] in her 1980 television music special, ''Lynda Carter: Encore!'' In 1980, Haggard headlined the '']'' soundtrack alongside ], which saw Haggard score a number-one hit with "]," a duet with actor ].<ref></ref> | |||

| Haggard was hampered by financial woes well into the 1990s, as his presence on the charts diminished in favor of newer country singers, such as ] and ]. Haggard's last number one hit was "]" from his smash album ''Chill Factor'' in 1988.<ref>{{cite web|last=Thanki|first=Juli|title=Merle Haggard dead at 79|url=http://www.tennessean.com/story/entertainment/music/2016/04/06/merle-haggard-dead-at-age-79/81272486/|publisher=thetennessean.com|date=April 6, 2016|accessdate=April 6, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Haggard appeared in an episode of '']'' titled "The Comeback," season five, episode three, original air-date October 10, 1976. He played a bandleader named Red, who had been depressed since the death of his son (Ron Howard).<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.allaboutthewaltons.com/ep-s5/s05-03.php|title=The Waltons s5-ep3 - The Comeback|website=www.allaboutthewaltons.com|access-date=2019-07-25}}</ref> | |||

| In 1989, Haggard recorded a song, "Me and Crippled Soldiers Give a Damn", in response to the ]'s decision to allow flag burning under the ]. After CBS Records Nashville avoided releasing the song, Haggard bought his way out of the contract and signed with ], which was willing to release the song. Haggard commented about the situation, "I've never been a guy that can do what people told me...It's always been my nature to fight the system."<ref name="Traditional Values NYT">{{cite news|last=Schoemer|first=Karen|title=Pop/Jazz; A Maverick Upholding Traditional Values|url=http://www.nytimes.com/1990/07/06/arts/pop-jazz-a-maverick-upholding-traditional-values.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm|accessdate=October 19, 2012|newspaper=The New York Times|date=July 6, 1990}}</ref> | |||

| In 1981, Haggard published an autobiography, ''Sing Me Back Home''. The same year, he provided the narration and theme for the movie '']''. The movie did not perform as well as expected attributing its commercial failure to the Wrather/Moore dispute which generated negative publicity. Haggard also changed record labels again in 1981, moving to Epic and releasing one of his most critically acclaimed albums, '']'', on which he was backed by the Strangers. | |||

| ==Comeback== | |||

| ] | |||

| In 2000, Haggard made a comeback of sorts, signing with the independent record label Anti and releasing the spare ''If I Could Only Fly'' to critical acclaim. He followed it in 2001 with ''Roots, vol. 1'', a collection of ], ], and ] covers, along with three Haggard originals. The album, recorded in Haggard's living room with no overdubs, featured Haggard's longtime bandmates the Strangers as well as Frizzell's original lead guitarist, Norman Stephens. In December 2004, Haggard spoke at length on '']'' about his incarceration as a young man and said it was "hell" and "the scariest experience of my life".<ref>{{cite web|title=A Look at San Quentin|url=http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0412/16/lkl.01.html|publisher=CNN|date=December 16, 2004|accessdate=April 6, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Between 1981 and 1985, Haggard scored 12 more top-10 country hits, with nine of them reaching number one, including "My Favorite Memory," "Going Where the Lonely Go," "Someday When Things Are Good," and "Natural High". In addition, Haggard recorded two chart-topping duets with ]—"Yesterdays' Wine" in 1982—and with ]—"Pancho and Lefty" in 1983. Nelson believed the 1983 ]-winning film '']'', about the life of fictional singer Mac Sledge, was based on the life of Merle Haggard. Actor ] and other filmmakers denied this and claimed the character was based on nobody in particular. Duvall, however, said he was a big fan of Haggard's.<ref>{{Cite AV media|people=] (actor), Gary Hertz (director)|date=April 16, 2002|title= Miracles & Mercies|url= https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0383509/ |medium=Documentary|publisher=] |location=]|access-date=January 28, 2008}}</ref> | |||

| When political opponents were attacking the ] for criticizing President ]'s invasion of Iraq, Haggard spoke up for the band on July 25, 2003, saying: | |||

| {{quote|I don't even know the Dixie Chicks, but I find it an insult for all the men and women who fought and died in past wars when almost the majority of America jumped down their throats for voicing an opinion. It was like a verbal witch-hunt and lynching.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.commondreams.org/headlines03/0725-02.htm |title=New Merle Haggard Tune Blasts US Media Coverage of Iraq War |publisher=Commondreams.org |date=July 25, 2003 |accessdate=December 26, 2010 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20100627174824/http://www.commondreams.org/headlines03/0725-02.htm |archivedate=June 27, 2010 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2003/07/25/entertainment/main565038.shtml | work=CBS News | title=Merle Haggard Sounds Off | date=July 25, 2003}}</ref>}} | |||

| In 1983, Haggard and his third wife Leona Williams divorced after five stormy years of marriage. The split served as a license to party for Haggard, who spent much of the next decade becoming mired in alcohol and drug problems.<ref name=heath />{{sfn|Cantwell|2013|p=230}} Haggard has stated that he was in his own ], or "male menopause," around this time. He said in an interview from this period: "Things that you've enjoyed for years don't seem nearly as important, and you're at war with yourself as to what's happening. 'Why don't I like that anymore? Why do I like this now?' And finally, I think you actually go through a biological change, you just, you become another.... Your body is getting ready to die and your mind doesn't agree."<ref name=AmericanMasters /> He was briefly a heavy user of cocaine but was able to quit.<ref name=heath /> Despite these issues, he won a ] for his 1984 remake of "]". | |||

| Haggard's number one hit single "Mama Tried" is featured in the 2003 film '']'' with ] and ] as well as in Bryan Bertino's "The Strangers" with Liv Tyler. In addition, his song "Swingin' Doors" can be heard in the film '']'',<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0375679/soundtrack|title=Crash (2004) — Soundtracks|website=imdb.com|accessdate=April 7, 2016}}</ref> and his 1981 hit "Big City" is heard in Joel and Ethan Coen's film '']''.<ref>{{cite news|title=Merle Haggard — "Big City"|newspaper=Billings Gazette|location=Billings, Montana|date=May 21, 2015|url=http://billingsgazette.com/merle-haggard---big-city/youtube_14088077-f574-5720-8d8d-5b085d40390b.html|accessdate=April 7, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| {{Quote_box | |||

| |width=20% | |||

| |align=left | |||

| |quote="He’s not going to play The Palace in Louisville, he’s going pick the tertiary towns, and he’s going to play on the outer edge. Merle was a real westerner. Like one of those lizards that thrives in arid heat. He was a California guy, but not the California you see on television with Palm Trees. He was the California that was dusty, that was Merle’s."<ref name="Owen13.04.16">{{cite news|last1=Owen|first1=Brent|title=Ketch Secor of Old Crow Medicine Show on Merle Haggard, puking in a hotel elevator in Louisville and ‘Wagon Wheel’|url=http://www.leoweekly.com/2016/04/28376/|accessdate=14 April 2016|publisher=Leo Weekly|date=13 April 2016}}</ref>|source=Ketch Secor, ]}} | |||

| In October 2005, Haggard released his album '']'' to mostly positive reviews. The album contained an anti-Iraq war song titled "America First," in which he laments the nation's economy and faltering infrastructure, applauds its soldiers, and sings, "Let's get out of Iraq, and get back on track." This follows from his 2003 release "Haggard Like Never Before" in which he includes a song, "That's The News". | |||

| Haggard released a ] album, '']'', on October 2, 2007.{{Citation needed|date=April 2016}} | |||

| Haggard was hampered by financial woes well into the 1990s, as his presence on the charts diminished in favor of newer country singers, such as ] and ]. Haggard's last number-one hit was "]" from his smash album ''Chill Factor'' in 1988.<ref>{{cite web|last=Thanki|first=Juli|title=Merle Haggard dead at 79|url=http://www.tennessean.com/story/entertainment/music/2016/04/06/merle-haggard-dead-at-age-79/81272486|publisher=thetennessean.com|date=April 6, 2016|access-date=April 6, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| In 2008, Haggard was going to perform at Riverfest in ], but the concert was canceled because he was ailing, and three other concerts were canceled, as well; however, he was back on the road in June and successfully completed a tour that ended on October 19, 2008.{{Citation needed|date=October 2009}} | |||

| In 1989, Haggard recorded a song, "Me and Crippled Soldiers Give a Damn," in response to the ]'s decision not to allow banning flag burning, considering it to be "speech" and therefore protected under the ]. After CBS Records Nashville avoided releasing the song, Haggard bought his way out of the contract and signed with ], which was willing to release the song. Haggard commented about the situation, "I've never been a guy that can do what people told me.... It's always been my nature to fight the system."<ref name="Traditional Values NYT">{{cite news|last=Schoemer|first=Karen|title=Pop/Jazz; A Maverick Upholding Traditional Values|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1990/07/06/arts/pop-jazz-a-maverick-upholding-traditional-values.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm|access-date=October 19, 2012|newspaper=The New York Times|date=July 6, 1990}}</ref> | |||

| In April 2010, Haggard released a new album, '']'',<ref>{{cite web|last=See|first=Elena|title=First Listen: Merle Haggard, 'I Am What I Am'|url=http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=125636724&sc=fb&cc=fp|publisher=www.npr.org|accessdate=July 22, 2010}}</ref> to strong reviews, and he performed the title song on '']'' in February 2011.<ref>{{cite web|last=Greene|first=Andy|title=Merle Haggard Reflects On Old Age and God on Leno|url=http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/merle-haggard-reflects-on-old-age-and-god-on-leno-20110209|publisher=Rolling Stone|date=February 9, 2011|accessdate=April 6, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| == |

===Comeback=== | ||

| ] | |||

| Haggard collaborated with many other artists over the course of his career. In the early 1960s, Haggard recorded duets with Bonnie Owens (who later became his wife) for Tally Records, scoring a minor hit with "Just Between the Two of Us". As part of the deal that got Haggard signed to Capitol, producer ] obtained the rights to Haggard's Tally sides, including the duets with Owens, resulting in the release of Haggard's first duet album with Owens in 1966, also entitled ''Just Between the Two of Us''.<ref>{{cite web |first=Mark |last= Deming |title= ''Just Between the Two of Us'' > Review |url={{Allmusic|class=album|id= mw0000095068 |pure_url=yes}} |publisher=] |accessdate=April 7, 2016}}</ref> The album reached number 4 on the country charts, and Haggard and Owens recorded a number of additional duets before their divorce in 1978. Haggard went on to record duets with ], ], and ], among others.<ref>{{cite magazine|last=Eddy|first=Chuck, et al.|title=Merle Haggard: Biography|magazine=]|url=http://www.rollingstone.com/music/artists/merle-haggard/biography|accessdate=April 7, 2016|deadurl=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160402021113/http://www.rollingstone.com/music/artists/merle-haggard/biography |archive-date=April 2, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| In 2000, Haggard made a comeback of sorts, signing with the independent record label Anti and releasing the spare ''If I Could Only Fly'' to critical acclaim. He followed it in 2001 with ''Roots, vol. 1'', a collection of ], ], and ] covers, along with three Haggard originals. The album, recorded in Haggard's living room with no overdubs, featured Haggard's longtime bandmates, the Strangers, as well as Frizzell's original lead guitarist, Norman Stephens. In December 2004, Haggard spoke at length on '']'' about his incarceration as a young man and said it was "hell" and "the scariest experience of my life".<ref>{{cite web|title=A Look at San Quentin|url=http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0412/16/lkl.01.html|publisher=CNN|date=December 16, 2004|access-date=April 6, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| When political opponents were attacking ] for criticizing President ]'s ], Haggard spoke up for the band on July 25, 2003, saying: | |||

| In 1970, Haggard released ''A Tribute to the Best Damn Fiddle Player in the World (or, My Salute to Bob Wills)'', rounding up six of the remaining members of the Texas Playboys to record the tribute: Johnnie Lee Wills, Eldon Shamblin, Tiny Moore, Joe Holley, Johnny Gimble, and Alex Brashear.<ref name =Hicks>{{cite journal|last=Hicks|first=Dan|title=A Tribute to the Best Damn Fiddle Player in the World (Or My Salute to Bob Wills)|journal=Rolling Stone|date=October 26, 1972|url=http://www.rollingstone.com/music/albumreviews/a-tribute-to-the-best-damn-fiddle-player-in-the-world-or-my-salute-to-bob-wills-19721026|accessdate=April 7, 2016}}</ref> Merle's band the Strangers were also present during the recording but Wills suffered a massive stroke after the first day of recording. Merle arrived on the second day, devastated that he wouldn't get to record with him; the album helped return Wills to public consciousness, and set off a Western swing revival.<ref name =WillsCMT>{{cite web|url=http://www.cmt.com/artists/bob-wills/biography/|title=Bob Wills Bio|website=cmt.com|accessdate=April 7, 2016}}</ref> Haggard would do other tribute albums to Bob Wills over the next 40 years. In 1973 he appeared on ''For the Last Time: Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys''. In 1994, Haggard collaborated with ] and many other artists influenced by the music of Bob Wills on an album entitled ''A Tribute To The Music of Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys''.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Menconi|first=David|title=Asleep at the Wheel Ready All-Star Bob Wills Tribute With Help From Avetts, Willie Nelson|journal=Rolling Stone|date=December 10, 2014|url=http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/asleep-at-the-wheel-ready-all-star-bob-wills-tribute-with-help-from-avetts-willie-nelson-20141210|accessdate=April 7, 2016}}</ref> ''A Tribute'' was re-released on CD on the Koch label in 1995. | |||

| {{blockquote|I don't even know the Dixie Chicks, but I find it an insult for all the men and women who fought and died in past wars when almost the majority of America jumped down their throats for voicing an opinion. It was like a verbal witch-hunt and lynching.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.commondreams.org/headlines03/0725-02.htm|title=New Merle Haggard Tune Blasts US Media Coverage of Iraq War|publisher=Commondreams.org|date=July 25, 2003|access-date=December 26, 2010|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100627174824/http://www.commondreams.org/headlines03/0725-02.htm|archive-date=June 27, 2010 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.cbsnews.com/news/merle-haggard-sounds-off/|work=CBS News|title=Merle Haggard Sounds Off|date=July 25, 2003}}</ref>}} | |||

| In 1972, Haggard agreed to produce ]' first solo album but backed out at the last minute. ] arranged a meeting at Haggard's Bakersfield home and the two musicians seemed to hit it off but later, on the afternoon of the first session, Haggard canceled. Parsons, an enormous Haggard fan, was crushed, with his wife Gretchen telling Meyer, "Merle not producing Gram was probably one of the greatest disappointments in Gram's life. Merle was very nice, very sweet, but he had his own enemies and his own demons."<ref name=meyer>{{cite book |last=Meyer |first=David N. |date=2007 |edition=2008 reprint |title=Twenty Thousand Roads: The Ballad of Gram Parsons and His Cosmic American Music |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=82Tdf-s1C-kC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false |location=New York City |publisher=Villard Books |page=358 |isbn=978-0345503367}}</ref> In 1980, Haggard dispelled the notion that Parsons was any kind of outlaw, telling Mark Rose, "He was a pussy. Hell, he was just a long-haired kid. I thought he was a good writer. He was not wild, though. That's what's funny to me. All these guys running around in long hair talking about being wild and ]. I don't think someone abusing themselves on drugs determines how wild they are. It might determine how ignorant they are."<ref name=meyer /> | |||