| Revision as of 04:07, 2 May 2016 editOshwah (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Checkusers, Interface administrators, Oversighters, Administrators496,883 editsm Reverted edits by Donladd (talk): Unexplained removal of content (HG) (3.1.20)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:23, 8 January 2025 edit undoPhlsph7 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users15,861 edits removed recently added section "Further Reading": the article already has many high-quality sources; maybe the source could be added as a reference in the article rather than starting a new section for it | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Territorial claim}} | |||

| {{multiple issues| | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| {{cleanup-rewrite|date=April 2014}} | |||

| ] from 1919 show some of the areas which were claimed by ].|267x267px]]'''Irredentism''' is one ]'s desire to ] the ] of another state. This desire can be motivated by ] reasons because the population of the territory is ethnically similar or the same to the population of the parent state.{{efn|In this context, "parent state" is a technical term for the state that intends to absorb the territory.{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|pp=419–426}}}} Historical reasons may also be responsible, i.e., that the territory previously formed part of the parent state.{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=419}}{{sfn|Griffiths|O'Callaghan|Roach|2008|pp=}}{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=8–10}} However, difficulties in applying the concept to concrete cases have given rise to academic debates about its precise definition. Disagreements concern whether either or both ethnic and historical reasons have to be present and whether ]s can also engage in irredentism. A further dispute is whether attempts to absorb a full neighboring state are also included. There are various types of irredentism. For typical forms of irredentism, the parent state already exists before the territorial conflict with a neighboring state arises. However, there are also forms of irredentism in which the parent state is newly created by uniting an ethnic group spread across several countries. Another distinction concerns whether the country to which the disputed territory currently belongs is a regular state, a former ], or a collapsed state. | |||

| {{refimprove|date=May 2015}} | |||

| {{Original research|date=May 2015}} | |||

| }} | |||

| A central research topic concerning irredentism is the question of how it is to be explained or what causes it. Many explanations hold that ethnic homogeneity within a state makes irredentism more likely. ] against the ethnic group in the neighboring territory is another contributing factor. A closely related explanation argues that ] based primarily on ethnicity, ], and history increase irredentist tendencies. Another approach is to explain irredentism as an attempt to increase power and wealth. In this regard, it is argued that irredentist claims are more likely if the neighboring territory is relatively rich. Many explanations also focus on the ] type and hold that ] are less likely to engage in irredentism while ] are particularly open to it. | |||

| ] in the aftermath of the ] that is depicted in the colour black on a map of France.]] | |||

| Irredentism has been an influential force in ] since the mid-nineteenth century. It has been responsible for many ], even though ] is hostile to it and irredentist movements often fail to achieve their goals. The term was originally coined from the Italian phrase ''Italia irredenta'' and referred to an ] after 1878 claiming parts of ] and the ]. Often discussed cases of irredentism include ] in 1938, ] in 1977, and ] in 1982. Further examples are attempts to establish a ] following the ] in the early 1990s and ] in 2014. Irredentism is closely related to ] and ]. Revanchism is an attempt to annex territory belonging to another state. It is motivated by the goal of taking revenge for a previous ], in contrast to the goal of irredentism of building an ethnically unified nation-state. In the case of secession, a territory breaks away and forms an independent state instead of merging with another state. | |||

| '''Irredentism''' (from ] ''irredento'' for "unredeemed") is any political or popular movement intended to reclaim and reoccupy a lost homeland. As such, irredentism tries to justify its territorial claims on the basis of (real or imagined) historic or ethnic affiliations. It is often advocated by ] and ] movements and has been a feature of ], ], and ]. | |||

| == Definition and etymology == | |||

| An area that may be subjected to a potential claim is sometimes called an '''''irredenta'''''. Not all irredentas are necessarily involved in irredentism.<ref>, ''Free Dictionary''</ref> | |||

| The term ''irredentism'' was coined from the ] phrase {{lang|it|Italia irredenta}} (unredeemed Italy). This phrase originally referred to territory in ] that was mostly or partly inhabited by ethnic ]. In particular, it applies to ] and ], but also ], ], ], and ] during the 19th and early 20th centuries.{{sfn|Barrett|2018|loc=}}{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}}{{sfn|Stibbe|2018}} Irredentist projects often use the term "Greater" to label the desired outcome of their expansion, as in "]" or "]".{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}}{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}} | |||

| Irredentism is often understood as the claim that territories belonging to one ] should be incorporated into another state because their population is ] similar or because it historically belonged to the other state before.{{sfn|Lagasse|Goldman|Hobson|Norton|2020|loc=}}{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=419}}{{sfn|Barrett|2018|loc=}} Many definitions of irredentism have been proposed to give a more precise formulation. Despite a wide overlap concerning its general features, there is no consensus about its exact characterization.{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=8–10}}{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=421}} The disagreements matter for evaluating whether irredentism was the cause of war which is difficult in many cases and different definitions often lead to opposite conclusions.{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=8–10}}{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|pp=420–421}} | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=December 2015}} | |||

| {{Main|Italian irredentism}} | |||

| There is wide consensus that irredentism is a form of ] involving the attempt to ] territories belonging to a neighboring state. However, not all such attempts constitute forms of irredentism and there is no academic consensus on precisely what other features need to be present. This concerns disagreements about who claims the territory, for what reasons they do so, and how much territory is claimed.{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=8–10}}{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}}{{sfn|Horowitz|2011|p=160}} Most scholars define irredentism as a claim made by one state on the territory of another state.{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=8–10}} In this regard, there are three essential entities to irredentism: (1) an irredentist state or parent state, (2) a neighboring host state or target state, and (3) the disputed territory belonging to the host state, often referred to as {{lang|it|irredenta}}.{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|p=2}}{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|pp=419–420}} According to this definition, popular movements demanding territorial change by ]s do not count as irredentist in the strict sense. A different definition characterizes irredentism as the attempt of an ] to break away and join their "real" motherland even though this minority is a non-state actor.{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=8–10}} | |||

| The word was coined in ] from the phrase ''Italia irredenta'' ("unredeemed Italy"). This originally referred to rule by ] over territories mostly or partly inhabited by ], such as ], ], ], ], ] and ] during the 19th and early 20th centuries. | |||

| The reason for engaging in territorial conflict is another issue, with some scholars stating that irredentism is primarily motivated by ethnicity. In this view, the population in the neighboring territory is ethnically similar and the intention is to retrieve the area to unite the people.{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=8–10}}{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}} This definition implies, for example, that the majority of the ]s in the history of ] were not forms of irredentism.{{sfn|Horowitz|2011|p=160}} Usually, irredentism is defined in terms of the motivation of the irredentist state, even if the territory is annexed against the will of the local population.{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|p=2}} Other theorists focus more on the historical claim that the disputed territory used to be part of the state's ancestral homeland.{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=8–10}}{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}} This is close to the literal meaning of the original Italian expression {{lang|it|terra irredenta}} as "unredeemed land".{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=419}}{{sfn|Griffiths|O'Callaghan|Roach|2008|pp=}} In this view, the ethnicity of the people inhabiting this territory is not important. However, it is also possible to combine both characterizations, i.e. that the motivation is either ethnic or historical or both.{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=8–10}}{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|pp=419–420}}{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}} Some scholars, like Benjamin Neuberger, include ] reasons in their definitions.{{sfn|Lagasse|Goldman|Hobson|Norton|2020|loc=}}{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}} | |||

| A common way to express a claim to adjacent territories on the grounds of historical or ethnic association is by using the epithet "Greater" before the country name. This conveys the image of national territory at its maximum conceivable extent with the country "proper" at its core. The use of "Greater" does not always convey an irredentistic meaning. | |||

| ]'s and ]'s claim over the entire ] constitutes a form of irredentism.]] | |||

| ==Formal irredentism== | |||

| A further disagreement concerns the amount of area that is to be annexed. Usually, irredentism is restricted to the attempt to incorporate some parts of another state.{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=8–10}} In this regard, irredentism challenges established borders with the neighboring state but does not challenge the existence of the neighboring state in general.{{sfn|Clarke|Foweraker|2003|pp=}} However, some definitions of irredentism also include attempts to absorb the whole neighboring state and not just a part of it. In this sense, claims by both South Korea and North Korea to incorporate the whole of the Korean Peninsula would be considered a form of irredentism.{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=8–10}} | |||

| Some states formalize their irredentist claims by including them in their constitutional documents, or through other means of legal enshrinement. | |||

| A popular view combining many of the elements listed above holds that irredentism is based on incongruence between the borders of a state and the boundaries of the corresponding ]. State borders are usually clearly delimited, both physically and on maps. National boundaries, on the other hand, are less tangible since they correspond to a group's perception of its historic, ], and ethnic boundaries.{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=8–10}} Irredentism may manifest if state borders do not correspond to national boundaries. The objective of irredentism is to enlarge a state to establish a congruence between its borders and the boundaries of the corresponding nation.{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=7–8}}{{sfn|Hinnebusch|2002|pp=}} | |||

| ===Afghanistan=== | |||

| The ] border with ], known as the ], was agreed to by Afghanistan and British India in 1893. The ] tribes inhabiting the border areas were divided between what have become two nations; Afghanistan never accepted the still-porous border and clashes broke out in the 1950s and 1960s between Afghanistan and Pakistan over the issue. All Afghan governments of the past century have declared, with varying intensity, a long-term goal of re-uniting all Pashtun-dominated areas under Afghan rule.<ref name="Roashan">, Institute for Afghan Studies, August 11, 2001. {{wayback|url=http://www.institute-for-afghan-studies.org/Contributions/Commentaries/DRRoashanArch/2001_08_11_unholy_durand_line.htm |date=20120325161737 }}</ref><ref>, '']'', 11 May 2009</ref> | |||

| == |

== Types == | ||

| {{multiple image | |||

| {{see also|Falkland Islands sovereignty dispute}} | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | perrow = 2 | |||

| | total_width = 350 | |||

| | image1 = Ethio-Somali_War_Map_1977.png | |||

| | alt1 = Map of Ethiopian territory occupied by Somalia in 1977 | |||

| | link1 = Greater Somalia | |||

| | image2 = Kurdish-inhabited_area_by_CIA_(1992)_box_inset_removed.jpg | |||

| | alt2 = Map of area inhabited by Kurds | |||

| | link2 = Greater Kurdistan | |||

| | footer = ]'s occupation of ] territory constitutes a typical case of irredentism between two states (left). The ] composed of ] living in ], ], ], and ] is an unusual type of irredentism since there is no pre-existing state to absorb the territories (right). | |||

| }} | |||

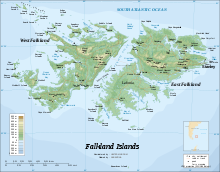

| Various types of irredentism have been proposed. However, not everyone agrees that all the types listed here constitute forms of irredentism and it often depends on what definition is used.{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=8–10}}{{sfn|Ambrosio|2022}}{{sfn|Horowitz|2011|p=159}} According to political theorists ] and ], there are two types of irredentism. The typical case involves one state that intends to annex territories belonging to a neighboring state. ]’s claim on the ] of ] is an example of this form of irredentism.{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}}{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}}{{sfn|Horowitz|2011|p=159}} | |||

| The Argentine government has maintained a claim over the Falkland Islands since 1833, and renewed it as recently as January 2013.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://edition.cnn.com/2013/01/03/world/europe/argentina-falklands-letter/index.html|title=Argentina presses claim to Falkland Islands, accusing UK of colonialism |publisher=CNN |accessdate=2012-01-08}}</ref> It considers the archipelago part of the ], along with ] and the ]. | |||

| For the second type, there is no pre-existing parent state. Instead, a cohesive group existing as a minority in multiple countries intends to unify to form a new parent state. The intended creation of a ] state uniting the ] living in Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran is an example of the second type. If such a project is successful for only one segment, the result is ] and not irredentism. This happened, for example, during the ] when ] formed the new state of ] while the ] did not join them and remained part of ].{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}}{{sfn|Horowitz|2011|p=159}} Not all theorists accept that the second type constitutes a form of irredentism. In this regard, it is often argued that it is too similar to secession to maintain a distinction between the two. For example, political scholar ] holds that a pre-existing parent state is necessary for irredentism.{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}} | |||

| The Argentine claim is included in the transitional provisions of the ] as ]:<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.senado.gov.ar/web/interes/constitucion/cuerpo1.php |title=Constitución Nacional |language=Spanish |date=22 August 1994 |accessdate=17 June 2011 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20132021481000/http://www.senado.gov.ar/web/interes/constitucion/cuerpo1.php |archivedate=February 5, 2016 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.senado.gov.ar/web/interes/constitucion/english.php |title=Constitution of the Argentine Nation |date=22 August 1994 |accessdate=17 June 2011 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20110604215413/http://www.senado.gov.ar/web/interes/constitucion/english.php |archivedate=June 4, 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| Political scientist ] restricts his definition to cases involving a pre-existing parent state and distinguishes three types of irredentism: (1) between two states, (2) between a state and a former ], and (3) between a state and a collapsed state. The typical case is between two states. A textbook example of this is ].{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|pp=420–421}}{{sfn|Ackermann|Schroeder|Terry|Upshur|2008a|p=143}} In the second case of decolonization, the territory to be annexed is a former colony of another state and not a regular part of it. An example is the ] and ] of the former Portuguese colony of ].{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|pp=420–421}}{{sfn|Ackermann|Schroeder|Terry|Upshur|2008a|p=130}} In the case of state collapse, one state disintegrates and a neighboring state absorbs some of its former territories. This was the case for the irredentist movements by ] and ] during the breakup of Yugoslavia.{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|pp=420–421}}{{sfn|Ackermann|Schroeder|Terry|Upshur|2008a|pp=49, 468–471}} | |||

| {{quote|The Argentine Nation ratifies its legitimate and non-prescribing sovereignty over the Malvinas, Georgias del Sur and Sandwich del Sur Islands and over the corresponding maritime and insular zones, as they are an integral part of the National territory. | |||

| == Explanations == | |||

| The recovery of these territories and the full exercise of sovereignty, respecting the way of life for its inhabitants and according to the principles of international law, constitute a permanent and unwavering goal of the Argentine people.}} | |||

| Explanations of irredentism try to determine what causes irredentism, how it unfolds, and how it can be peacefully resolved.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2022}} Various hypotheses have been proposed but there is still very little consensus on how irredentism is to be explained despite its prevalence and its long history of provoking armed conflicts.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}}{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|pp=8–9}} Some of these proposals can be combined but others conflict with each other and the available ] may not be sufficient to decide between them.{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|p=2}} An active research topic in this regard concerns the reasons for irredentism. Many countries have ethnic kin outside their borders. But only a few are willing to engage in violent conflicts to annex foreign territory in an attempt to unite their kin. Research on the causes of irredentism tries to explain why some countries pursue irredentism but others do not.{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|p=1}}{{sfn|Saideman|Ayres|2000|pp=}} Relevant factors often discussed include ethnicity, ], ] considerations, the desire to increase power, and the type of ].{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}}{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}}{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|pp=8–9}} | |||

| === Ethnicity and nationalism === | |||

| ===Bolivia=== | |||

| ] in the 1930s contributed to Hungary's decision to ally with ].{{sfn|Hames|2004|p=}}{{sfn|Hanebrink|2018|p=}}]] | |||

| ] (1879–1884): "What once was ours, will be ours once again", and "Hold on ]s (Chileans), because here come the Colorados of Bolivia"]] | |||

| A common explanation of irredentism focuses on ethnic arguments.{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}}{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}}{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|pp=2–3}} It is based on the observation that irredentist claims are primarily advanced by states with a homogenous ethnic population. This is explained by the idea that, if a state is composed of several ], then annexing a territory inhabited primarily by one of those groups would shift the power balance in favor of this group. For this reason, other groups in the state are likely to internally reject the irredentist claims. This inhibiting factor is not present for homogeneous states. A similar argument is also offered for the enclave to be annexed: an ethnically heterogenous enclave is less likely to desire to be absorbed by another state for ethnic reasons since this would only benefit one ethnic group.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}}{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|pp=2–3}} These considerations explain, for example, why irredentism is not very common in ] since most African states are ethnically heterogeneous.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}} Relevant factors for the ethnic motivation for irredentism are how large the dominant ethnic group is relative to other groups and how large it is in absolute terms. It also matters whether the ethnic group is relatively dispersed or located in a small core area and whether it is politically disadvantaged.{{sfn|Saideman|Ayres|2000|pp=}} | |||

| Explanations focusing on nationalism are closely related to ethnicity-based explanations.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}}{{sfn|Clarke|Foweraker|2003|pp=}} Nationalism can be defined as the claim that the boundaries of a state should match those of the nation.{{sfn|Hechter|2000|p=}}{{sfn|Gellner|2008|p=}} According to ] accounts, for example, the dominant ] is one of the central factors behind irredentism. In this view, identities based on ethnicity, culture, and history can easily invite tendencies to enlarge national borders. They may justify the goal of integrating ethnically and culturally similar territories. Civic national identities focusing more on a political nature, on the other hand, are more closely tied to pre-existing national boundaries.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}} | |||

| The 2009 constitution of ] states that the country has an unrenounceable right over the territory that gives it access to the ] and its maritime space.<ref>CAPÍTULO CUARTO, REIVINDICACIÓN MARÍTIMA. Artículo 267. I. El Estado boliviano declara su derecho irrenunciable e imprescriptible sobre el territorio que le dé acceso al océano Pacífico y su espacio marítimo. II. La solución efectiva al diferendo marítimo a través de medios pacíficos y el ejercicio pleno de la soberanía sobre dicho territorio constituyen objetivos permanentes e irrenunciables del Estado boliviano.</ref> This is understood as territory that Bolivia and Peru ceded to Chile after the ], which left Bolivia as a ] country. | |||

| Structural accounts use a slightly different approach and focus on the relationship between nationalism and the regional context. They focus on the tension between ] and national ].{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}} State sovereignty is the principle of ] holding that each state has sovereignty over its own territory. It means that states are not allowed to interfere with essentially domestic affairs of other states.{{sfn|UN|1945}} National self-determination, on the other hand, concerns the right of people to determine their own international ].{{sfn|LII staff|2022}} According to the structural explanation, emphasis on national self-determination may legitimize irredentist claims while the principle of state sovereignty defends the status quo of the existing sovereign borders. This position is supported by the observation that irredentist conflicts are much more common during times of international upheavals.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}} | |||

| ===China=== | |||

| {{main|Chinese Unification|Greater China}} | |||

| ] is an example of how irredentist movements, like ]'s intervention, try to justify their aggression as ]s.]] | |||

| The preamble to the ] states, "] is part of the sacred territory of the People's Republic of China (PRC). It is the lofty duty of the entire ], including our compatriots in Taiwan, to accomplish the great task of ]." The PRC claim to sovereignty over Taiwan is generally based on the theory of the ], with the PRC claiming that it is the successor state to the ].<ref name=prc_wp>{{cite web|year=2005 |title=The One-China Principle and the Taiwan Issue |work=PRC Taiwan Affairs Office and the Information Office of the State Council |url=http://www.gwytb.gov.cn:8088/detail.asp?table=WhitePaper&title=White%20Papers%20On%20Taiwan%20Issue&m_id=4 |accessdate=2006-03-06 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/20060213045631/http://www.gwytb.gov.cn:8088/detail.asp?table=WhitePaper&title=White%20Papers%20On%20Taiwan%20Issue&m_id=4 |archivedate=13 February 2006 }}</ref> | |||

| Another factor commonly cited as a force fueling irredentism is ] against the main ethnic group in the enclave.{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|p=3}} Irredentist states often try to legitimize their aggression against neighbors by presenting them as ]s aimed at protecting their discriminated ethnic kin. This justification was used, for example, in ]'s engagement in the ] conflict, in Serbia's involvement in the ], and in ].{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|pp=8–9}}{{sfn|Ambrosio|2022}} Some political theorists, like David S. Siroky and Christopher W. Hale, hold that there is little ] for arguments based on ethnic homogeneity and discrimination. In this view, they are mainly used as a pretext to hide other goals, such as material gain.{{sfn|Griffiths|O'Callaghan|Roach|2008|pp=}}{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|pp=2–3}}{{sfn|Orabator|1981|pp=}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Another relevant factor is the outlook of the population inhabiting the territory to be annexed. The desire of the irredentist state to annex a foreign territory and the desire of that territory to be annexed do not always overlap.{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|pp=1–2}} In some cases, a minority group does not want to be annexed, as was the case for the ] in Russia's annexation of Crimea.{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|pp=1–2}}{{sfn|Walker|2022}} In other cases, a minority group would want to be annexed but the intended parent state is not interested.{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|pp=1–2}} | |||

| The Government of the Republic of China formerly administered both mainland China and Taiwan; the government has been administering only Taiwan since its defeat in the ] by the armed forces of the ]. While the official name of the state remains 'Republic of China', the country is commonly called 'Taiwan', since Taiwan makes up 99% of the controlled territory of the ROC. | |||

| === Power and economy === | |||

| Article 4 of the ] originally stated that "he territory of the Republic of China within its existing national boundaries shall not be altered except by a resolution of the ]". Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the Government of the Republic of China on Taiwan maintained itself to be the legitimate ruler of Mainland China as well. As part of its current policy continuing of the 'status quo', the ROC has not renounced claims over the territories currently controlled by the People's Republic of China, ], ], ] and some ]n states. However, Taiwan does not actively pursue these claims in practice; the remaining claims that Taiwan is actively seeking are the ], whose sovereignty is also asserted by ] and the PRC; Paracel Islands and the ] in ], with multiple claimants. | |||

| Various accounts stress the role of power and economic benefits as reasons for irredentism. ] explanations focus on the power balance between the irredentist state and the target state: the more this power balance shifts in favor of the irredentist state, the more likely violent conflicts become. A key factor in this regard is also the reaction of the ], i.e. whether irredentist claims are tolerated or rejected.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}} Irredentism can be used as a tool or pretext to increase the parent state's power.{{sfn|Griffiths|O'Callaghan|Roach|2008|pp=}}{{sfn|Orabator|1981|pp=}} Rational choice theories study how irredentism is caused by decision-making processes of certain groups within a state. In this view, irredentism is a tool used by elites to secure their political interests. They do so by appealing to popular nationalist sentiments. This can be used, for example, to gain public support against political rivals or to divert attention away from domestic problems.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}}{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|p=4}} | |||

| Other explanations focus on economic factors. For example, larger states enjoy advantages that come with having an increased market and decreased ] cost of defense. However, there are also disadvantages to having a bigger state, such as the challenges that come with accommodating a wider range of citizens' ]s.{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|pp=1–3}}{{sfn|Bain|2008|loc=}} Based on these lines of thought, it has been argued that states are more likely to advocate irredentist claims if the ] is a relatively rich territory.{{sfn|Orabator|1981|pp=}}{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|pp=1–3}} | |||

| ===Comoros=== | |||

| Article 1 of the Constitution of the Union of the ] begins: "The Union of the Comoros is a republic, composed of the autonomous islands of ], ], ], and ]." Mayotte, geographically a part of the Comoro Islands, was the only island of the four to vote against independence from France (independence losing 37%–63%) in the referendum held December 22, 1974. The total vote was 94%–5% in favor of independence. Mayotte is currently a department of the French Republic.<ref>UN General Assembly, {{wayback|url=http://un.cti.depaul.edu/Countries/Comoros/1156245840.pdf |date=20080527195255 }}</ref><ref>Security Council S/PV. 1888 para 247 S/11967 {{Wayback|url=http://www.globalpolicy.org/security/membship/veto/vetosubj.htm|date =20080317010910|bot=DASHBot}}</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Regime type === | ||

| An additional relevant factor is the regime type of both the irredentist state and the neighboring state. In this regard, it is often argued that ]s are less likely to engage in irredentism. One reason cited is that democracies often are more inclusive of other ethnic groups. Another is that democracies are in general less likely to engage in violent conflicts. This is closely related to ], which claims that democracies try to avoid armed conflicts with other democracies. This is also supported by the observation that most irredentist conflicts are started by ]s.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}}{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|p=3}}{{sfn|Reiter|2019}} However, irredentism constitutes a paradox for democratic systems. The reason is that ] pertaining to the ethnic group can often be used to justify its claim, which may be interpreted as the expression of a popular will toward unification. But there are also cases of irredentism made primarily by a government that is not broadly supported by the population.{{sfn|Clarke|Foweraker|2003|pp=}} | |||

| {{Main|Akhand Bharat|Indo-Pak Confederation}} | |||

| According to Siroky and Hale, ] regimes are most likely to engage in irredentist conflicts and to become their victim. This is based on the idea that they share some democratic ideals favoring irredentism but often lack institutional stability and ]. This makes it more likely for the elites to consolidate their power using ] appeals to the masses.{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|p=3}} | |||

| All of the European colonies on the ] which were not part of the ] have been annexed by ] since it gained its independence from the ]. An example of such territories was the 1961 ]. An example of annexation of a territory from the British Raj was the ]. | |||

| == Importance, reactions, and consequences == | |||

| ], literally Undivided India, is an irredentist call to reunite ] and ] with ] to form an ''Undivided India'' as it existed before ] in 1947 (and before that, during other periods of political unity in ], such as during the ], the ], the ] or the ]). The call for ''Akhand Bharat'' has often been raised by mainstream ]n nationalistic cultural and political organizations such as the ] (RSS) and the ] (BJP).<ref name=Ferguson>Yale H. Ferguson and R. J. Barry Jones, ''Political space: frontiers of change and governance in a globalizing world'', page 155, SUNY Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-7914-5460-2</ref><ref name=Majumder>Sucheta Majumder, "Right Wing Mobilization in India", ''Feminist Review'', issue 49, page 17, Routledge, 1995, ISBN 978-0-415-12375-4</ref><ref name=Martensson>Ulrika Mårtensson and Jennifer Bailey, ''Fundamentalism in the Modern World'' (Volume 1), page 97, I.B.Tauris, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84885-330-0</ref> Other major Indian political parties such as the ], while maintaining positions against the partition of India on religious grounds, do not necessarily subscribe to a call to reunite South Asia in the form of Akhand Bharat. | |||

| ] (1980–1988), ]'s ] claimed it had the right to hold sovereignty to the east bank of the ] river held by ].{{sfn|Goldstein|2005|p=}} The war claimed the lives of more than a million people.{{sfn|Hussain|2023}}]] | |||

| Irredentism is a widespread phenomenon and has been an influential force in ] since the mid-nineteenth century. It has been responsible for countless conflicts. There are still many unresolved irredentist disputes today that constitute discords between nations.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}}{{sfn|Clarke|Foweraker|2003|pp=}}{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|p=11}} In this regard, irredentism is a potential source of conflict in many places and often escalates into military confrontations between states.{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}}{{sfn|Griffiths|O'Callaghan|Roach|2008|pp=}}{{sfn|Hinnebusch|2002|pp=}} For example, ] theorist Markus Kornprobst argues that "no other issue over which states fight is as war-prone as irredentism".{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|p=11}} Political scholar Rachel Walker points out that "there is scarcely a country in the world that is not involved in some sort of irredentist quarrel ... although few would admit to this".{{sfn|Clarke|Foweraker|2003|pp=}} Political theorists Stephen M. Saideman and R. William Ayres argue that many of the most important conflicts of the 1990s were caused by irredentism, such as the wars for a Greater Serbia and a ].{{sfn|Saideman|Ayres|2000|pp=}} Irredentism carries a lot of potential for future conflicts since many states have kin groups in adjacent countries. It has been argued that it poses a significant danger to human security and the ].{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|p=1}} For these reasons, irredentism has been a central topic in the field of ].{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}} | |||

| For the most part, international law is hostile to irredentism. For example, the ] calls for respect for established territorial borders and defends state sovereignty. Similar outlooks are taken by the ], the ], and the ].{{sfn|Griffiths|O'Callaghan|Roach|2008|pp=}} Since irredentist claims are based on conflicting sovereignty assertions, it is often difficult to find a working compromise.{{sfn|Clarke|Foweraker|2003|pp=}} Peaceful resolutions of irredentist conflicts often result in mutual recognition of de facto borders rather than territorial change.{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=7–8}} International relation theorists ] ''et al.'' argue that the threat of rising irredentism may be reduced by focusing on ] and respect for ].{{sfn|Griffiths|O'Callaghan|Roach|2008|pp=}} | |||

| The region of ] in northwestern India has been the issue of a territorial dispute between India and Pakistan since 1947, the ]. Multiple wars have been fought over the issue, the first one immediately upon independence and partition in 1947 itself. To stave off a Pakistani and tribal invasion, ] ] of the ] of ] signed the ] with India. Kashmir has remained divided in three parts, administered by India, Pakistan and ], since then. However, on the basis of the instrument of accession, India continues to claim the entire Kashmir region as its integral part. All modern Indian political parties support the return of the entirety of Kashmir to India, and all official maps of India show the entire ] state (including parts under Pakistani or Chinese administration after 1947) as an integral part of India.{{citation needed|date=December 2015}} | |||

| Irredentist movements, peaceful or violent, are rarely successful.{{sfn|Griffiths|O'Callaghan|Roach|2008|pp=}} In many cases, despite aiming to help ethnic minorities, irredentism often has the opposite effect and ends up worsening their living conditions. On the one hand, the state still in control of those territories may decide to further discriminate against them as an attempt to decrease the threat to its ]. On the other hand, the irredentist state may merely claim to care about the ethnic minorities but, in truth, use such claims only as a pretext to increase its territory or to destabilize an opponent.{{sfn|Griffiths|O'Callaghan|Roach|2008|pp=}}{{sfn|Orabator|1981|pp=}} | |||

| ===Indonesia=== | |||

| {{Main|Greater Indonesia}} | |||

| == Often-discussed historical examples == | |||

| Indonesia claimed all territories of the former ], and previously viewed British plans to group the ] and ] into a new independent federation of ] as a threat to its objective to create a united state called ]. The Indonesian opposition of Malaysian formation has led to the ] in the early 1960s. It also held ] (modern ]) from 1975 to 2002 based on irredentist claims. | |||

| {{Main|List of irredentist claims or disputes}} | |||

| <!-- This section is intended to give only a brief overview of some of the most discussed cases of irredentism. Other cases or additional details should not be included here but at ] or at the corresponding main topic article. --> | |||

| The emergence of irredentism is tied to the rise of modern nationalism and the idea of a nation-state, which are often linked to the ].{{sfn|Lagasse|Goldman|Hobson|Norton|2020|loc=}}{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}} However, some political scholars, like Griffiths ''et al.'', argue that phenomena similar to irredentism existed even before. For example, part of the justification for the ] was to liberate fellow ] from ] and to redeem the ]. Nonetheless, most theorists see irredentism as a more recent phenomenon. The term was coined in the 19th century and is linked to border disputes between modern states.{{sfn|Griffiths|O'Callaghan|Roach|2008|pp=}}{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}}{{sfn|Gilman|Peck|Colby|1905|loc=]}} | |||

| ] from 1938 through 1939. The dark purple area shows the ] annexed by ].]] | |||

| The idea of uniting former British and Dutch colonial possessions in Southeast Asia actually has its roots in the early 20th century, as the concept of Greater Malay (''Melayu Raya'') was coined in ] espoused by students and graduates of ] in the late 1920s.<ref name="McIntyre">{{cite journal |last=McIntyre |first=Angus |authorlink= |year=1973 |title=The 'Greater Indonesia' Idea of Nationalism in Malaysia and Indonesia. |journal=Modern Asian Studies |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=75–83 |id= |url= |accessdate= 2008-02-16 |doi=10.1017/S0026749X0000439X}}</ref> Some of political figures in Indonesia including ] and ] revived the idea in the 1950s and named the political union concept as Greater Indonesia. | |||

| Nazi Germany's ] in 1938 is an often-cited example of irredentism. At the time, the Sudetenland formed part of Czechoslovakia but had a majority German population. Adolf Hitler justified the annexation based on his allegation that ] were being mistreated by the Czechoslovak government. The Sudetenland was yielded to Germany following the ] in an attempt to prevent the outbreak of a major war.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2022}}{{sfn|Knowles|2006|loc=}}{{sfn|Ackermann|Schroeder|Terry|Upshur|2008|pp=xxvi, 20}} | |||

| ===Israel=== | |||

| {{Main|Israeli nationalism|Palestinian nationalism|Greater Israel}} | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=December 2015}} | |||

| The nation state of Israel was established in 1948. The ] passed U.N. Resolution 181 otherwise known as the ] by an overwhelming 78% of the UNGA passing the resolution. Eventually, Israeli independence was achieved following the liquidation of the former British-administered Mandate of Palestine, the departure of the British and the "Independence War" between the Jews in ex-] and five Arab states' armies. The Jewish claim for Palestine as the "Jewish homeland" can be seen as an example of irredentism, based on ancestral conquest and the ]. Proponents of the formation, expansion, or defense of Israel, who subscribe to these historical or religious justifications, are sometimes called (and refer to themselves as) ]. It should also be noted that ] had sizable ] and ] populations before the ]. | |||

| Somalia's ] in 1977 is frequently discussed as a case of African irredentism. The goal of this attack was to unite the significant Somali population living in the ] with their kin by annexing this area to create a ]. The invasion escalated into a ] that lasted about eight months. Somalia was close to reaching its goal but failed in the end, mainly due to an intervention by socialist countries.{{sfn|Ackermann|Schroeder|Terry|Upshur|2008a|p=143}}{{sfn|Christie|1998|p=}}{{sfn|Tareke|2000|pp=}} | |||

| ] and ], as they are called in the Bible, were part of the ancient ] (designated the ] by Jordan in 1947) and the ], previously annexed by Jordan and occupied by Egypt respectively, were conquered and occupied by Israel in the ] in 1967. Israel withdrew from Gaza in August 2005; Judea and Samaria (West Bank) remain under Israeli control. Israel has never explicitly claimed sovereignty over any part of the West Bank apart from ], which it unilaterally annexed in 1980. However, the Israeli military supports and defends hundreds of thousands of Israeli citizens who have ] to the West Bank, incurring criticism by some who otherwise support Israel. The United Nations Security Council, the United Nations General Assembly, and some countries and international organizations continue to regard Israel as occupying Gaza. ''(See ].)'' | |||

| ] is a ] but claimed by ].]] | |||

| The Israeli annexing instrument, the ]—one of the ] (Israel does not have a constitution)—declares Jerusalem, "complete and united", to be the capital of Israel. Article 3 of the Basic Law of the ], which was ratified in 2002 by the ] and serves as an interim constitution, claims that "] is the capital of Palestine." ''De facto'', the Palestinian government administers the parts of the ] that Israel has granted it authority over from ], while the ] is administered by ] from ]. | |||

| Argentina's ] in 1982 is cited as an example of irredentism in South America,{{sfn|Goebel|2011|pp=}} where the Argentine military government sought to exploit national sentiment over the islands to deflect attention from domestic concerns.{{sfn|Sirlin|2006}}{{sfn|United States. Department of State|1981|p=}} President ] exploited the issue to reduce British influence in Argentina, instituting ] teaching the islands were Argentine{{sfn|Escudé|1992|pp=}} and creating a strong nationalist sentiment over the issue.{{sfn|Escudé|1992|pp=}} The war ended with a victory for the UK after about two months even though many analysts considered the Argentine military position unassailable.{{sfn|Woodward|Robinson|1997}}{{sfn|Brunet-Jailly|2015|p=}} Although defeated, Argentina did not officially declare the cessation of hostilities until 1989 and successive Argentine Governments have continued to claim the islands.<ref>{{multiref2 |1={{harvnb|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}} |2={{harvnb|Beck|2006|pp=648–649}} |3={{harvnb|Ackermann|Schroeder|Terry|Upshur|2008a|pp=xxvi, 147–148}} |4={{harvnb|West|2002|p=}} }}</ref> The islands are now self-governing with the UK responsible for defence and foreign relations.{{sfn|Cahill|2010}} Referenda in ] and ] show a preference for British sovereignty among the population.{{sfn|BBC staff|2013}} Both the UK{{sfn|Cawkell|2001|p=28}} and Spain{{sfn|Cawkell|2001|p=33}} claimed ] in the 18th Century and Argentina claims the islands as a colonial legacy from independence in 1816.{{sfn|Embassy in New Zeland|2023}}{{sfn|Hasani|2023}} | |||

| The United States does not recognize Israeli sovereignty over East Jerusalem and maintains its embassy in Tel Aviv. In Jerusalem, the United States maintains two Consulates General as a diplomatic representation to the city of Jerusalem alone, separate from representation to the state of Israel. One of the Consulates General was established before the 1967 war, and the other in a recently constructed building on the Israeli side of Jerusalem. However, Congress passed the ] in 1995 that says the US shall move its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, but allows the ] to delay the move every year if it is deemed contrary to national security interests. Since 1995, every president has delayed the move. | |||

| The breakup of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s resulted in various irredentist projects. They include ]'s attempts to establish a Greater Serbia by absorbing some regions of neighboring states that were part of former Yugoslavia. A simultaneous similar project aimed at the establishment of a Greater Croatia.{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|pp=420–421}}{{sfn|Ackermann|Schroeder|Terry|Upshur|2008a|pp=49, 468–471}} | |||

| A minority of Israelis and Jews regard the ] (which is today the ]) as the eastern parts of the ] (following the ] idea) because, according to the Bible, the ] of ], ], and ] settled on the east bank of the Jordan, and because that area was designated a ] by the ] in the ]. | |||

| ] annexed by ] since 2014 (]) and 2022 (], ], ] and ]), with a red line marking the area of actual control by Russia on 30 September 2022]] | |||

| ===Korea=== | |||

| {{main|Korean reunification}} | |||

| Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014 is a more recent example of irredentism.{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|p=1}}{{sfn|Navarro|2015|p=}}{{sfn|Batta|2021|p=}} Beginning in the 15th century ], the Crimean peninsula was a ]. However, in 1783 the ] broke a previous ] and ] Crimea. In 1954, when both Russia and Ukraine were part of the Soviet Union, it was ] from Russia to Ukraine.{{sfn|Anderson|1958|pp=}}{{sfn|Solchanyk|2001|p=}} Sixty years later, Russia alleged that the ] did not uphold the rights of ] inhabiting Crimea, using this as a justification for the annexation in March 2014. {{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|p=1}}{{sfn|Navarro|2015|p=}}{{sfn|Batta|2021|p=}} However, it has been claimed that this was only a pretext to increase its territory and power.{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|p=1}} Ultimately, Russia ] the mainland territory of Ukraine in February 2022, thereby escalating the war that continues to the present day.{{sfn|Ray|2023|loc=lead section}} | |||

| Since their founding, both Korean states have disputed the legitimacy of the other. ]'s constitution claims jurisdiction over the entire Korean peninsula. It acknowledges the ] only indirectly by requiring the president to work for reunification. The ], established in 1949, is the South Korean authority charged with the administration of Korean territory north of the ] (i.e., North Korea), and consists of the governors of the five provinces, who are appointed by the ]. However the body is purely symbolic and largely tasked with dealing with Northern defectors; if reunification were to actually occur the Committee would be dissolved and new administrators appointed by the ].<ref>{{cite news|url=http://blogs.wsj.com/korearealtime/2014/03/18/south-koreas-governors-in-theory-for-north-korea/|title=South Korea’s Governors-in-Theory for North Korea|date=March 18, 2014|work=]|accessdate=29 April 2014}}</ref> | |||

| Other frequently discussed cases of irredentism include disputes between Pakistan and India over ] as well as ]'s ].{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=4, 7–8}}{{sfn|Harding|1988|p=}} | |||

| ]'s constitution also stresses the importance of reunification, but, while it makes no similar formal provision for administering the South, it effectively claims its territory as it does not ] the Republic of Korea, deeming it an "entity occupying the Korean territory". | |||

| == Related concepts == | |||

| Other territories sometimes disputed to belong to Korea are ]. | |||

| === Ethnicity === | |||

| Ethnicity plays a central role in irredentism since most irredentist states justify their ] agenda based on shared ethnicity. In this regard, the goal of unifying parts of an ethnic group in a common nation-state is used as a justification for annexing foreign territories and going to war if the neighboring state resists.{{sfn|Lagasse|Goldman|Hobson|Norton|2020|loc=}}{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=419}}{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}} Ethnicity is a grouping of people according to a set of shared attributes and similarities. It divides people into groups based on attributes like physical features, customs, ], historical background, ], ], ], and values.{{sfn|Chandra|2012|pp=}}{{sfn|Richardson-Bouie|2003|loc=}}{{sfn|Law|2008|loc=}} Not all these factors are equally relevant for every ethnic group. For some groups, one factor may predominate, as in ], ethno-racial, and ] identities. In most cases, ethnic identities are based on a set of common features.{{sfn|Alba|1992|loc=}}{{sfn|Taras|Ganguly|2015|loc=1. Ethnic Conflict on the World Stage: Definitions}} | |||

| A central aspect of many ethnic identities is that all members share a common homeland or place of origin. This place of origin does not have to correspond to the area where the majority of the ethnic group currently lives in case they migrated from their homeland. Another feature is a common language or ]. In many cases, religion also forms a vital aspect of ethnicity. Shared culture is another significant factor. It is a wide term and can include characteristic social institutions, diet, dress, and other practices. It is often difficult to draw clear boundaries between people based on their ethnicity.{{sfn|Law|2008|loc=}} For this reason, some definitions focus less on actual objective features and stress instead that what unites an ethnic group is a subjective belief that such common features exist. In this view, the common belief matters more than the extent to which those shared features actually exist.{{sfn|Law|2008|loc=}}{{sfn|Alba|1992|loc=}} Examples of large ethnic groups are the ], the ], the ], the ], and the ].{{sfn|Law|2008|loc=}}{{sfn|Radstone|Wilson|2020}} | |||

| === Venezuela === | |||

| {{main|Guayana Esequiba}} | |||

| Some theorists, like ] John Milton Yinger, use terms like ''ethnic group'' or ''ethnicity'' as near-synonyms for ''nation''.{{sfn|Yinger|1994|p=}} Nations are usually based on ethnicity but what sets them apart from ethnicity is their political form as a state or a state-like entity. The physical and visible aspects of ethnicity, such as skin color and facial features, are often referred to as ], which may thus be understood as a subset of ethnicity.{{sfn|Law|2008|loc=}} However, some theorists, like sociologist Pierre van den Berghe, contrast the two by restricting ethnicity to cultural traits and race to physical traits.{{sfn|Alba|1992|loc=}} | |||

| The ] is a territory administered by ] but claimed by ]. It was first included in the ] and the ] by ], but was later included in ] by the Dutch and in ] by the ]. Originally, parts of what is now eastern Venezuela were included in the disputed area. This territory of 159,500 km² is the subject of a long-running boundary dispute inherited from the colonial powers and complicated by the independence of Guyana in 1966. The status of the territory is subject to the Treaty of Geneva, which was signed by the United Kingdom, Venezuela and British Guiana governments on February 17, 1966. This treaty stipulates that the parties will agree to find a practical, peaceful and satisfactory solution to the dispute.<ref name=Geneva> from ]</ref> | |||

| Ethnic solidarity can provide a sense of belonging as well as physical and mental security. It can help people identify with a common purpose.{{sfn|Law|2008|loc=}} However, ethnicity has also been the source of many conflicts. It has been responsible for various forms of ], including ] and ]. The perpetrators usually form part of the ruling majority and target ethnic minority groups.{{sfn|Law|2008|loc=}}{{sfn|Sherrer|2005}} Not all ethnic-based conflicts involve mass violence, like many forms of ].{{sfn|Law|2008|loc=}} | |||

| ==Other irredentism== | |||

| === Nationalism and nation-state=== | |||

| ===Europe=== | |||

| {{main|Nationalism|Nation state}} | |||

| Irredentism is often seen as a product of modern nationalism, i.e. the claim that a nation should have its own sovereign state.{{sfn|Lagasse|Goldman|Hobson|Norton|2020|loc=}}{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}} In this regard, irredentism emerged with and depends on the modern idea of nation-states.{{sfn|Clarke|Foweraker|2003|pp=}} The start of modern nationalism is often associated with the French Revolution in 1789. This spawned various nationalist ]s in Europe around the mid-nineteenth century. They often resulted in a replacement of ] imperial governments.{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}} A central aspect of nationalism is that it sees states as entities with clearly delimited borders that should correspond to national boundaries.{{sfn|Clarke|Foweraker|2003|pp=}}{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=7–8}} Irredentism reflects the importance people ascribe to these borders and how exactly they are drawn. One difficulty in this regard is that the exact boundaries are often difficult to justify and are therefore challenged in favor of alternatives. Irredentism manifests some of the most aggressive aspects of modern nationalism.{{sfn|Griffiths|O'Callaghan|Roach|2008|pp=}} It can be seen as a side effect of nationalism paired with the importance it ascribes to borders and the difficulties in agreeing on them.{{sfn|Clarke|Foweraker|2003|pp=}}{{sfn|Kornprobst|2008|pp=10–11}} | |||

| === |

=== Secession === | ||

| {{main|Secession}} | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2015}} | |||

| ], various southern states (shown in bright and dark red) seceded from the ].]] | |||

| Irredentism is closely related to secession.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}}{{sfn|Saideman|Ayres|2000|pp=}}{{sfn|Horowitz|2011|p=158}} Secession can be defined as "an attempt by an ethnic group claiming a homeland to withdraw with its territory from the authority of a larger state of which it is a part."{{sfn|Horowitz|2011|p=158}} Irredentism, by contrast, is initiated by members of an ethnic group in one state to incorporate territories across their border housing ethnically kindred people.{{sfn|Horowitz|2011|p=158}} Secession happens when a part of an existing state breaks away to form an independent entity. This was the case, for example, in the ], when many of the ] southern states decided to secede from the Union to form the ] in 1861.{{sfn|Ackermann|Schroeder|Terry|Upshur|2008b|p=4}}{{sfn|Griffiths|O'Callaghan|Roach|2008|pp=}} | |||

| In the case of irredentism, the break-away area does not become independent but merges into another entity.{{sfn|Griffiths|O'Callaghan|Roach|2008|pp=}}{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}}{{sfn|Clarke|Foweraker|2003|pp=}} Irredentism is often seen as a government decision, unlike secession.{{sfn|Siroky|Hale|2017|p=1}} Both movements are influential phenomena in contemporary politics but, as Horowitz argues, secession movements are much more frequent in ] states. However, he also holds that secession movements are less likely to succeed since they usually have very few military resources compared to irredentist states. For this reason, they normally need prolonged external assistance, often from another state.{{sfn|Horowitz|2011|pp=159–160}} However, such state policies are subject to change. For example, the Indian government supported the ] up to 1987 but then reach an ] and helped suppress the movement.{{sfn|Horowitz|2011|p=162}}{{sfn|Senaratne|2021|pp=|loc=Sri Lanka: A Case Study}}{{sfn|Ackermann|Schroeder|Terry|Upshur|2008a|pp=403–404}} | |||

| Some of the most violent irredentist conflicts of recent times in ] flared up as a consequence of the break-up of the former ]n federal state in the early 1990s.{{dubious|date=October 2011}}{{clarify|date=October 2011}} The conflict erupted further south with the ethnic Albanian majority in ] seeking to switch allegiance to the adjoining state of ].<ref>See ] 1991, ''Irredentism and international politics''</ref> | |||

| ] and the ] and ]]] | |||

| ====Albania==== | |||

| Horowitz holds that it is important to distinguish secessionist and irredentist movements since they differ significantly concerning their motivation, context, and goals.{{sfn|Horowitz|2011|pp=159–160}} Despite these differences, irredentism and secessionism are closely related nonetheless.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2011|pp=1346–1348|loc=irredentism}}{{sfn|Saideman|Ayres|2000|pp=}} In some cases, the two tendencies may exist side by side. It is also possible that the advocates of one movement change their outlook and promote the other. Whether a movement favors irredentism or secessionism is determined, among other things, by the prospects of forming an independent state in contrast to joining another state.{{sfn|Horowitz|2011|pp=160–161}} A further factor is whether the irredentist state is likely to espouse a similar ] to the one found in the territory intending to break away. The anticipated reaction of the international community is an additional factor, i.e. whether it would embrace, tolerate, or reject the detachment or the absorption by another state.{{sfn|Horowitz|2011|pp=161–162}} | |||

| {{main|Albanian nationalism|Greater Albania}} | |||

| === Revanchism === | |||

| Greater Albania<ref>http://www.da.mod.uk/colleges/csrc/document-listings/balkan/07%2811%29MD.pdf,"as Albanians continue mobilizing their ethnic presence in a cultural, geographic and economic sense, they further the process of creating a Greater Albania. "</ref> or ''Ethnic Albania'' as called by the Albanian nationalists themselves,<ref name="Bogdani2007">{{Cite book|title=Albania and the European Union: the tumultuous journey towards integration |last=Bogdani |first=Mirela |authorlink= |author2=John Loughlin |year=2007 |publisher=IB Taurus |location= |isbn= 978-1-84511-308-7|page=230 |pages= |url=https://books.google.com/?id=32Wu8H7t8MwC&pg=PA230&dq=ethnic+albania&cd=4#v=onepage&q=ethnic%20albania |accessdate=2010-05-28}}</ref> is an irredentist concept of lands outside the borders of ] which are considered part of a greater national homeland by most Albanians,<ref name=Balkan-Insight>, Balkan Insight, 17 Nov 2010</ref> based on claims on the present-day or historical presence of Albanian populations in those areas. The term incorporates claims to ], as well as territories in the neighbouring countries ], ] and the ]. Albanians themselves mostly use the term ''ethnic Albania'' instead.<ref name="Bogdani2007" /> According to the ''Gallup Balkan Monitor'' 2010 report, the idea of a Greater Albania is supported by the majority of Albanians in Albania (63%), Kosovo (81%) and the Republic of Macedonia (53%).<ref name=Balkan-Insight/><ref>, 2010</ref> In 2012, as part of the celebrations for the ], Prime Minister ] spoke of "Albanian lands" stretching from ] in Greece to ] in Serbia, and from the Macedonian capital of ] to the Montenegrin capital of ], angering Albania's neighbors. The comments were also inscribed on a parchment that will be displayed at a museum in the city of Vlore, where the country's independence from the Ottoman Empire was declared in 1912.<ref>''Albania celebrates 100 years of independence, yet angers half its neighbors'' Associated Press, November 28, 2012.{{dead link|date=April 2014}}</ref> | |||

| Irredentism and ] are two closely related phenomena because both of them involve the attempt to annex territory which belongs to another state.{{sfn|Wittmann|2016|pp=}}{{sfn|Burnett|2020|p=}}{{sfn|Nolan|2002|p=}} They differ concerning the motivation fuelling this attempt. Irredentism has a positive goal of building a "greater" state that fulfills the ideals of a nation-state. It aims to unify people claimed to belong together because of their shared national identity based on ethnic, cultural, and historical aspects.{{sfn|White|Millett|2019|p=420}}{{sfn|Clarke|Foweraker|2003|pp=}}{{sfn|Wittmann|2016|pp=}} | |||

| For revanchism, on the other hand, the goal is more negative because it focuses on taking ] for some form of ] or injustice suffered earlier.{{sfn|Wittmann|2016|pp=}}{{sfn|Margalit|2009|p=}}{{sfn|Ghervas|2021|p=}} In this regard, it is motivated by ] and aims to reverse territorial losses due to a previous defeat. In an attempt to contrast irredentism with revanchism, political scientist Anna M. Wittmann argues that Germany's annexation of the Sudetenland in 1938 constitutes a form of irredentism because of its emphasis on a shared language and ethnicity. But she characterizes Germany's ] the following year as a form of revanchism due to its justification as a revenge intended to reverse previous territorial losses.{{sfn|Wittmann|2016|pp=}} The term "revanchism" comes from the French term {{lang|fr|revanche}}, meaning ''revenge''.{{sfn|Wittmann|2016|pp=}}{{sfn|Nolan|2002|p=}} It was originally used in the aftermath of the ] for nationalists intending to reclaim the lost territory of ].{{sfn|Wittmann|2016|pp=}} ] justified the ] in 1990 by claiming that ] had always been an integral part of Iraq and only became an independent nation due to the interference of the British Empire.{{sfn|Humphreys|2005|p=}} | |||

| ====Bulgaria==== | |||

| {{main|Greater Bulgaria}} | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| Based on the territorial definition of a historic Bulgarian state, a "]" nationalist movement has been active for more than a century that would annex most of ], ], and ]. | |||

| {{div col|colwidth=30em}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Ethnic nationalism}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Expansionism}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Lebensraum|{{lang|de|Lebensraum|nocat=yes}}}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Mutilated victory}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Racial nationalism}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Religious nationalism}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Separatism}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Secession}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Manifest destiny}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Pan-nationalism}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Phyletism}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Reactionary}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Rump state}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Status quo ante bellum |{{lang|la|Status quo ante bellum |nocat=yes}}}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link |Territorial dispute}} | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| ====France==== | |||

| {{main|Natural borders of France}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| The idea of the natural borders of France is a political theory conceptualized primarily in the late 18th and early 19th centuries that focused on widening the borders primarily based on either practical reasons or the territory that was thought to be the maximum extent that the ancient Gauls inhabited. This theory lays claim to portions of Belgium and Germany. | |||

| === Notes === | |||

| {{Notelist}} | |||

| === |

=== Citations === | ||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| {{main|German Question|Pan-Germanism|Anschluss|Munich Agreement}} | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2015}} | |||

| During the ] (1871), the term ''Großdeutschland'' "Greater Germany" referred to a possible German nation consisting of the states that later comprised the ] and ]. The term ''Kleindeutschland'' "Lesser Germany" referred to a possible German state without Austria. The term was also used by Germans referring to Greater Germany, a state consisting of pre-World War I Germany, Austria and the ]. This issue was known as the ]. | |||

| A main point of ] was to reunify all Germans either born or living outside of Germany to create an "all-German ]." These beliefs ultimately resulted in the Munich Agreement, which ceded to Germany areas of Czechoslovakia that were mainly inhabited by those of German descent and the Anschluss, which ceded the entire country of Austria to Germany; both events occurred in 1938. | |||

| ====Greece==== | |||

| {{Main|Megali Idea}} | |||

| Following the ] in 1821–1832, ] began to contest areas inhabited by Greeks, primarily against the ]. The ] (Great Idea) envisioned Greek incorporation of Greek-inhabited lands, but also historical lands in ] corresponding with the predominantly Greek and Orthodox ] and the dominions of the ancient Greeks. | |||

| ] | |||

| The Greek quest began with the acquisition of ] through the ], ] and the ] (], ], some ]). After World War I, Greece acquired ] from ] as per the ], but also ]/] and ] (excluding ]) from the Ottoman Empire as ordained in the ]. Subsequently, Greece launched an ] to further their gains in Asia Minor, but were halted by the ]. The events culminated into the ], ] and ] which returned Eastern Thrace and Ionia to the newfound Turkish Republic. The events are known as the "Asia Minor Catastrophe" to Greeks. The ] were ceded by Britain in 1864, and the ] by Italy in 1947. | |||

| Another Greek irredentist claim includes ] (currently part of ]), where a sizable Greek minority lives. Greece officially annexed Northern Epirus in March 1916, but was forced to revoke by the Great Powers. In 1917 Greece lost control of the rest of Northern Epirus to Italy. The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 awarded the area to Greece after World War I, however, political developments such as the Greek defeat in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22) and, crucially, Italian, Austrian and German lobbying in favor of Albania resulted in the area being ceded to Albania in November 1921. | |||

| Another concern of the Greeks is the ] which was ceded by the Ottomans to ]. As a result of the ] the island gained independence as the ] in 1960. The failed incorporation by Greece through ] and the ] in 1974 led to the formation of the mostly unrecognized ] and has culminated into the present-day ]. | |||

| The Aegean islands of ] which were not ceded to Greece over the course of the 20th century and where the dominant Greek community has faced persecution are also of concern. | |||

| ====Hungary==== | |||

| {{Main|Hungarian irredentism}} | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2015}} | |||

| The restoration of the borders of ] to their state prior to World War I, in order to unite all ethnic Hungarians within the same country once again. | |||

| ====Ireland==== | |||

| {{main|United Ireland}} | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2015}} | |||

| From 1937 until 1999, ] provided that "he national territory consists of the whole island of Ireland". However, "ending the re-integration of the national territory", the powers of the state were restricted to legislate only for the area that had ceded from the ]. Arising from the ], the matter was mutually resolved in 1998. The ]'s constitution was altered by ] and its territorial claim to ] was suspended. The amended constitution asserts that while it is the entitlement of "every person born in the island of Ireland{{citation needed|date=September 2015}} ... to be part of the Irish Nation" and to hold Irish citizenship, "a united Ireland shall be brought about only by peaceful means with the consent of a majority of the people, democratically expressed, in both jurisdictions in the island." Certain ] were created between Northern Ireland, the part of the island that remained in the United Kingdom, and the Republic of Ireland, and these were given executive authority. The advisory and consultative role of the government of Ireland in the government of Northern Ireland granted by the United Kingdom, that had begun with the 1985 ], was maintained, although that Agreement itself was ended. The two states also settled the long-running ]: ''Ireland'' and the ''United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland'', with both governments agreeing to use those names. | |||

| ====Italy==== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Italian irredentism|Italian Empire}} | |||

| Italy's territorial claims were on the basis of re-establishing a Romanesque Empire, a fourth shore according to the concept of Mare Nostrum (Latin for 'Our Sea') and traditional ethnic borders. Evident in Italy's rapid takeover of surrounding territories under Fascist leader Benito Mussolini and claims following the collapsed 1915 ] and 1918 ] which established feelings of betrayal. Similar to the Nazis' stab-in-the-back myth, Mussolini and Hitler's similarities including a joint hatred towards the French and wanting to expand their territories brought the two leaders together, solidified in the ] and later WW2. By 1942 Italy had conquered Abyssinia (modern day Ethiopia), Libya, Much of Egypt, Tunisia, Kenya and Somalia. And – on the European continent – Istria, Dalmatia, Albania, Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia, the Spanish island of Majorca and France's Corsica; Malta was also bombed. Underlying tensions remained with France, over its territories of Corsica, Nice and Savoy. | |||

| ====Macedonia==== | |||

| {{main|United Macedonia}} | |||

| ] nationalists circa 1993.]] | |||

| The ] promotes the irredentist concept of a ] ({{lang-mk|Обединета Македонија, ''Obedineta Makedonija''}}) among ] ] which involves territorial claims on the northern province of ] in ], but also in ] ("Pirin Macedonia") in Bulgaria, Albania, and Serbia. The United Macedonia concept aims to unify the transnational ] in the ] (which they claim as their homeland and which they assert was wrongfully divided under the ] in 1913), into a single state under Macedonian domination, with the ] city of ] (''Solun'' in the ]) as its capital.<ref name="Times">Greek Macedonia "not a problem", ''The Times'' (London), August 5, 1957</ref><ref>{{YouTube|t2GMihoOmF8|A large assembly of people during the inauguration of the Statue of Alexander the Great in Skopje}}, {{YouTube|Kh25jfXxY2w|the players of the national basketball team of the Republic of Macedonia during the European Basketball Championship in Lithuania}}, {{YouTube|97ucJP97Sto|and a little girl}}, singing a nationalistic tune called Izlezi Momče (Излези момче, "Get out boy"). Translation from Macedonian: | |||

| <poem> | |||

| Get out, boy, straight on the terrace | |||

| And salute ] race | |||

| Raise your hands up high | |||

| Ours will be ]'s area.</poem></ref> | |||

| ====Norway==== | |||

| {{main|Norwegian Empire|List of possessions of Norway#Former dependencies and homelands}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The Kingdom of ] maintains some claim to territories lost at the dissolution of the ] union. The ], which was the Norwegian territories at its maximum extent, included ], the settleable areas of ], the ] and ] among others. Under Danish sovereignty since they established a hegemonic position in the ], the territories were considered as Norwegian colonies. When in the ] in 1814, Norway's territories were transferred from ] to ], the territories of Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands were maintained by Denmark. In 1919, Norway declared sovereignty over an area in Eastern Greenland in the ], which led to a dispute with Denmark that was not settled until 1933, by the ]. Norway formerly included the provinces ], ], ], ] (lost since the ]), and ] (lost since the ]), which were ceded to Sweden after Danish defeats in wars such as the ] and ]. | |||

| ====Poland==== | |||

| {{See also|Polish nationalism|Kresy}} | |||

| ] ("Borderlands"), is a term that refers to the eastern lands that formerly belonged to ]. In 1921, Polish troops crossed the ], the border between ethnic Polish and ethnic Ukrainian and Belorussian territories and ], and also ]. These territories were re-annexed by the ] in 1939 under the ], and include major cities, like ] (Ukraine), ] (the capital of Lithuania), and ] (Belarus). Even though ''Kresy'', or the ''Eastern Borderlands'', are no longer Polish territories, the area is still inhabited by a significant Polish minority, and the memory of a Polish ''Kresy'' is still cultivated. The attachment to the "myth of Kresy", the vision of the region as a peaceful, idyllic, rural land, has been criticized in Polish discourse.<ref></ref> | |||

| In January, February and March 2012, the ] conducted a survey, asking Poles about their ties to the Kresy. It turned out that almost 15% of the population of Poland (4.3–4.6 million people) declared that they had either been born in the Kresy, or had a parent or a grandparent who came from that region. Numerous treasures of Polish culture remain and there are numerous Kresy-oriented organizations. There are Polish sports clubs (], ]), newspapers (], ]), radio stations (in Lviv and Vilnius), numerous theatres, schools, choirs and folk ensembles. Poles living in ''Kresy'' are helped by ], a Polish government-sponsored organization, as well as other organizations, such as The ''Association of Help of Poles in the East Kresy'' (see also ]). Money is frequently collected to help those Poles who live in ''Kresy'', and there are several annual events, such as a ''Christmas Package for a Polish Veteran in Kresy'', and ''Summer with Poland'', sponsored by the ], in which Polish children from ''Kresy'' are invited to visit Poland.<ref></ref> Polish language handbooks and films, as well as medicines and clothes are collected and sent to ''Kresy''. Books are most often sent to Polish schools which exist there — for example, in December 2010, The University of Wrocław organized an event called ''Become a Polish Santa Claus and Give a Book to a Polish Child in Kresy''.<ref></ref> Polish churches and cemeteries (such as ]) are renovated with money from Poland. | |||

| ====Portugal==== | |||

| {{main|Olivenza#Claims of sovereignty|Greater Portugal}} | |||

| ] does not recognize Spanish sovereignty over the territory of ], ceded under coercion to Spain during the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.elpais.com/articulo/espana/eterna/disputa/Olivenza-Olivenca/elpepunac/20061204elpepinac_13/Tes |title=La eterna disputa de Olivenza-Olivença | Edición impresa | EL PAÍS |publisher=Elpais.com |accessdate=2014-04-20}}</ref> Since the ] of the mid-nineteenth century, there has been an intellectual ] between ] and the region of ], under Spanish sovereignty. Although this movement has become increasingly popular on both sides of the border, there is no consensus in regard to the nature of such ''reintegration'': whether political, socio-cultural or merely linguistic. | |||

| ====Romania==== | |||

| {{Main|Greater Romania|Unification of Romania and Moldova}} | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2015}} | |||

| Romania lays claims to Greater Romania, which include ] and ] as ], since they were parts of Romania' and are inhabited in majority by Romanians (same people as Moldavians). | |||

| ====Russia==== | |||

| {{Main|Russian nationalism|All-Russian nation|Eurasianism|Greater Russia}} | |||

| {{See also|Republic of Crimea|Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation}} | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2015}} | |||

| The ] in 2014 was based on a claim of protecting ] residing there. Crimea was part of the ] from 1783 to 1917, after which it enjoyed a few years of autonomy until it was made part of the ] (which was a part of Soviet Union) from 1921 to 1954 and then ] to ] (which also was a part of Soviet Union) in 1954, which remained part of Ukraine until February 2014. Russia declared Crimea to be part of the Russian Federation in March 2014, and effective administration commenced. The Russian regional status is not currently recognised by the UN General Assembly and by many countries. | |||

| Russian irredentism also includes southeastern and coastal Ukraine, known as '']'', a term from the Russian Empire. | |||

| ====Serbia==== | |||

| {{Main|Serbian nationalism|Greater Serbia}} | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2015}} | |||

| Pan-Serbism or ] sees the creation of a Serb land which would incorporate all regions of traditional significance to the Serbian nation, and regions outside of Serbia that are populated mostly by ]. This movement's main ideology is to unite all Serbs (or all ]) into one ], claiming, depending on the version, different areas of many surrounding countries. | |||

| ====Spain==== | |||

| {{further|Spanish nationalism|Disputed status of Gibraltar}} | |||

| Spain maintains a claim on ], a ] near the southernmost tip of the ], which has been British since the 18th Century. | |||

| Gibraltar was ], during the ] (1701–1714). The ] formally ceded the territory in perpetuity to the British Crown in 1713, under ] of the ]. Spain's territorial claim was formally reasserted by the Spanish dictator ] in the 1960s and has been continued by successive ]. In 2002 an agreement in principle on joint sovereignty over ] between the governments of the United Kingdom and Spain was decisively rejected in a ]. The British Government now refuses to discuss sovereignty without the consent of the Gibraltarians.<ref name="Answer to Q257 at the FAC hearing">{{cite web|author=The Committee Office, House of Commons |url=http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200708/cmselect/cmfaff/147/8032602.htm |title=Answer to Q257 at the FAC hearing |publisher=Publications.parliament.uk |accessdate=2013-08-05}}</ref> | |||

| ===Western Asia=== | |||

| ====Caucasus==== | |||

| {{main|Armenian nationalism|Azerbaijani nationalism}} | |||

| {{Expand section|date=January 2015}} | |||

| Irredentism is acute in the Caucasus region, too. The ] movement's original slogan of ''miatsum'' ('union') was explicitly oriented towards unification with Armenia, feeding an Azerbaijani understanding of the conflict as a bilateral one between itself and an irredentist Armenia.<ref>{{cite web|author=Patrick Barron |url=http://www.c-r.org/resources/occasional-papers/resources-for-peace.php |title=Dr Laurence Broers, The resources for peace: comparing the Karabakh, Abkhazia and South Ossetia peace processes, Conciliation Resources, 2006 |publisher=C-r.org |date= |accessdate=2014-05-21}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|author=CRIA |url=http://cria-online.org/5_4.html |title=Fareed Shafee, Inspired from Abroad: The External Sources of Separatism in Azerbaijan, Caucasian Review of International Affairs, Vol. 2 (4) – Autumn 2008, pp. 200–211 |publisher=Cria-online.org |date= |accessdate=2014-05-21}}</ref><ref> SEMP, Biot Report #224, USA, June 21, 2005</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sneps.net/NNE/09NNNSaidemanAyres.pdf |title=Saideman, Stephen M. and R. William Ayres, For Kin and Country: Xenophobia, Nationalism and War, New York, N.Y.: Columbia University Press, 2008 |format=PDF |date= |accessdate=2014-05-21}}</ref><ref>, Jamestown Foundation Monitor Volume: 4 Issue: 77, Washington DC, April 22, 1998</ref> According to Prof. Thomas Ambrosio, "Armenia's successful irredentist project in the Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan" and "From 1992 to the cease-fire in 1994, Armenia encountered a highly permissive or tolerant international environment that allowed its annexation of some 15 percent of Azerbaijani territory".<ref>Prof. Thomas Ambrosio, , Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001</ref> | |||