| Revision as of 15:01, 14 October 2016 editHyju (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users10,893 edits added Category:Disney comics using HotCat← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:06, 26 October 2024 edit undoBruce1ee (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers268,659 editsm fixed lint errors – missing end tag | ||

| (265 intermediate revisions by 60 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1971 book by Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart}} | |||

| {{Infobox book | {{Infobox book | ||

| | name = How to Read Donald Duck | | name = How to Read Donald Duck | ||

| ⚫ | | authors = ]<br />] | ||

| ⚫ | | language = Spanish | ||

| ⚫ | | country = ] | ||

| ⚫ | | genre = | ||

| | publisher = | |||

| ⚫ | | isbn = | ||

| | image = Para leer al Pato Donald, Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaiso, 1971.jpg | | image = Para leer al Pato Donald, Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaiso, 1971.jpg | ||

| | caption = |

| caption = | ||

| | title_orig = Para leer al Pato Donald | |||

| ⚫ | | |

||

| | |

| translator = David Kunzle | ||

| | translator = ] (English) | |||

| | illustrator = | | illustrator = | ||

| | cover_artist = | | cover_artist = | ||

| ⚫ | | country = ] | ||

| ⚫ | | language = Spanish | ||

| | series = | | series = | ||

| | subject = | | subject = | ||

| ⚫ | | genre = | ||

| | publisher = Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaiso | |||

| | pub_date = 1971 | | pub_date = 1971 | ||

| | english_pub_date = 1975 | | english_pub_date = 1975 | ||

| | media_type = | | media_type = Print | ||

| | pages = | | pages = | ||

| ⚫ | | isbn = |

||

| | oclc = | | oclc = | ||

| | dewey = | | dewey = | ||

| Line 25: | Line 26: | ||

| | followed_by = | | followed_by = | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''''How to Read Donald Duck''''' ({{langx|es|Para leer al Pato Donald}}) is a 1971 book-length essay by ] and ] that critiques ] from a ] point of view as ] for ] ] and ].<ref>{{Cite web|title=How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic|url=https://www.plutobooks.com/9780745339788/how-to-read-donald-duck/|date=March 2019|website=Pluto Press}}</ref><ref name=":3">{{Cite book|last=Lazare|first=Donald|title=American Media and Mass Culture: Left Perspectives|publisher=University of California Press|year=1987|isbn=9780520044951|pages=16–17}}</ref> It was first published in ] in 1971, became a bestseller throughout ]<ref name=":0">Jason Jolley. . ''The Literary Encyclopedia'' (2009)</ref> and is still considered a seminal work in ].<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.groene.nl/artikel/kaalgeplukt-en-doorgekookt|title=Kaalgeplukt en doorgekookt: Ariel Dorfman over Donald Duck|date=1 July 2009|newspaper=]}}</ref> It was reissued in August 2018 to a general audience in the United States, with a new introduction by Dorfman, by ]. | |||

| '''''How to Read Donald Duck''''' ({{lang-es|Para leer al Pato Donald}}) is an early work critiquing popular cultural forms that has been labelled by some as ]<ref>{{cite web |first= Stanley|last= Kurtz|authorlink= Stanley Kurtz|author= |coauthors= |title= How the College Board Politicized U.S. History|url= http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/386202/how-college-board-politicized-us-history-stanley-kurtz|work= |publisher= ] |id= |pages= |page= |date= 2014-08-25|accessdate= 2014-08-30 |quote= }}</ref><ref>{{cite web| last =Patanella| first =Dan| year =1997| title =Goodbye, Carl Barks| page =| url =http://www.oocities.org/d-patanella/carlbarks.html| accessdate =August 21, 2014| }}</ref> written by ] and ]. It discusses the impact of comic books featuring the ] Duck cartoon characters (], ], etc.). The book was written and published in 1971 in ] under socialist president ]. | |||

| ==Summary== | == Summary == | ||

| The book's thesis is that ] are not only a reflection of the prevailing ] at the time (]), but that they are also aware of this, and are active agents in spreading the ideology. To do so, Disney comics use images of the everyday world: | |||

| Dorfman and Mattelart argue that the Duck comics, particularly those featuring the ultra-rich Scrooge McDuck on international searches for treasure, take on an ideological cast that reflects and naturalises American corporate exploitation of Latin American countries. While Dorfman and Mattelart argue in the original text that this is corporate ideology of the Disney Corporation is made manifest in the comic books, ]'s introduction to the 1991 English edition suggests that in the years since the book's initial publication, Dorfman had "taken a more generous view of the comics he excoriated, at least those by ] (main writer and artist of the Duck comics), whom he too recognizes as an unrivaled satirist.<ref>Kunzle, David. 'Introduction to the English Edition (1991).' ''How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic, 4th Ed.''. International General, 1991, p. 17.</ref>" | |||

| :{{Quote|text="Here lies Disney's inventive (product of his era), rejecting the crude and explicit scheme of adventure strips, that came up at the same time. The ideological background is without any doubt the same: but Disney, not showing any open repressive force, is much more dangerous. The division between Bruce Wayne and Batman is the projection of fantasy outside the ordinary world to save it. Disney colonizes the everyday world, at hand of ordinary man and his common problems, with the analgesic of a child's imagination".|author=Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart|title=|source=''How to Read Donald Duck'', p. 148}} | |||

| This closeness to everyday life is so only in appearance, because the world shown in the comics, according to the thesis, is based on ideological concepts, resulting in a set of ''natural rules'' that lead to the acceptance of particular ideas about ], the ]' relationship with the ], ]s, etc. | |||

| As an example, the book considers the lack of descendants of the characters.<ref> p. 23. 1983. Besides the lack of descendants, there is a complete lack of libido or sexuality. The quote at the beginning of this chapter is remarkable: | |||

| == Criticism == | |||

| *"Daisy: ''If you teach me how to skate this afternoon I'll give you what you have always wanted.'' | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| *Donald: ''Do you mean...?'' | |||

| *Daisy: ''Yes... my 1872 coin''"</ref> Everybody has an uncle or nephew, everybody is a cousin of someone, but nobody has fathers or sons. This non-parental reality creates horizontal levels in society, where there is no hierarchic order, except the one given by the amount of money and wealth possessed by each, and where there is almost no solidarity among those of the same level, creating a situation where the only thing left is crude competition.<ref> p. 35. 1983.</ref> Another issue analyzed is the absolute necessity to have a stroke of luck for ] (regardless of the effort or intelligence involved),<ref> p. 139. 1983.</ref> the lack of ability of the native tribes to manage their wealth,<ref> p. 53. 1983.</ref> and others. | |||

| == Publication history == | |||

| ] | |||

| ''How to Read Donald Duck'' was written and published by Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso, belonging to the ], during the brief flowering of ] under the government of ] and his ] coalition and is closely identified with the revolutionary politics of its era.<ref name="Tomlinson">Tomlinson (1991), p. 41–45</ref> In 1973, ], secretly supported by the ], brought in power the ] of ]. During Pinochet's regime, ''How to Read Donald Duck'' was banned and subject to ]; its authors were forced into ].<ref name="Tomlinson" /> | |||

| Outside Chile, ''How to Read Donald Duck'' became the most widely printed political text in Latin America for some time.<ref name=":0" /> It was translated into ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]<ref name="McClennen3">McClennen (2010), p. 245-279</ref> and sold some 700.000 copies overall; by 1993, it had been reprinted 32 times by the publisher ].<ref name="Mendoza">Mendoza, Montaner, Llosa (2000), p. 199–201</ref> | |||

| A hardcover edition with a new introduction by Dorfman was published by ] in the United States in October 2018.<ref>{{cite web |title=How to Read Donald Duck |url=http://www.orbooks.com/catalog/donald-duck/ |website=OR Books |date=10 May 2018 |access-date=27 August 2018}}</ref> | |||

| == Reception == | |||

| ⚫ | Thomas Andrae, who has written about ], has criticized the thesis of Dorfman and Mattelart. Andrae writes that it is not true that Disney controlled the work of every cartoonist, and that cartoonists had almost completely free hands unlike those who worked in ]. According to Andrae, Carl Barks did not even know that his cartoons were read outside the United States in the 1950s. Lastly, he writes that Barks' cartoons include ] and even ] and ] references.<ref>{{Citation| last =Andrae| first =Thomas| year =2006| title =Carl Barks and the Disney Comic Book: Unmasking the Myth of Modernity| publisher =Univ. Press of Mississippi| isbn = 1578068584}}</ref> | ||

| David Kunzle, who translated the book into English, spoke to Carl Barks for his introduction and came to a similar conclusion. He believes Barks projected his own experience as an underpaid cartoonist onto ], and views some of his stories as ]s "in which the imperialist Duckburgers come off looking as foolish as—and far meaner than—the innocent ] natives".<ref>{{Cite web |last=Kunzle |first=David |orig-date=Originally delivered as a speech at the 1976 Caucus for Marxism and Art at the College Art Association Convention |title=The Parts That Got Left Out of the Donald Duck Book, or: How Karl Marx Prevailed Over Carl Barks |url=https://imagetextjournal.com/the-parts-that-got-left-out-of-the-donald-duck-book-or-how-karl-marx-prevailed-over-carl-barks/ |access-date=2022-06-03 |website=ImageTexT |language=en-US |issn=1549-6732}}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * '']'' | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{reflist |

{{reflist}} | ||

| ==Sources== | |||

| * {{citation | last1=Andrae | first1= Thomas | title=''Carl Barks and the Disney Comic Book: Unmasking the Myth of Modernity'' | chapter= Rereading Donald Duck| year=2006 | publisher=]| isbn=978-1578068586| chapter-url =https://books.google.com/books?id=CYP2Cj_Gb98C&q=%22How+to+Read%22&pg=RA2-PA184}} | |||

| * {{citation |editor1-last=Constantinou|editor1-first=Costas M. |editor2-last=Richmond|editor2-first=Oliver P. |editor3-last=Watson|editor3-first=Alison M.S. | last1=Constantinou | first1= Costas M. | title=''Cultures and Politics of Global Communication: Volume 34, Review of International Studies'' | chapter= Communications/excommunications: an interview with Armand Matellart| year=2008 | publisher=]| isbn= 978-0521727112| chapter-url =https://books.google.com/books?id=xpJ0_WQIbZoC&q=How+to+Read+Donald+Duck&pg=PA27}} | |||

| * {{citation | last1=McClennen | first1= Sophia A. | title=Ariel Dorfman:An Aesthetics of Hope | year=2010 | publisher=]| isbn= 978-0-8223-9195-1| url =https://books.google.com/books?id=ixvhfnKIlw4C&q=Donald+Duck&pg=PA74}} | |||

| *{{citation | last1=Mendoza | first1= Plinio Apuleyo | last2=Montaner | first2= Carlos Alberto | last3=Llosa | first3= Alvaro Vargas | title=Guide to the Perfect Latin American Idiot | title-link= Guide to the Perfect Latin American Idiot | chapter= How to Read Donald Duck: Ariel Dorfman and Armand Matellart, 1972| year=2000 | publisher=]| isbn= 978-1-4616-6278-5| chapter-url =https://books.google.com/books?id=Vm6tyox2mxQC&q=How+to+Read+Donald+Duck&pg=PA199}} | |||

| * {{citation | last1=Mirrlees | first1= Tanner | title=''Global Entertainment Media: Between Cultural Imperialism and Cultural Globalization'' | chapter= Paradigms of Global Entertainment Media| year=2013 | publisher=]| isbn= 978-1136334658| chapter-url =https://books.google.com/books?id=bKnNISWnoMQC&q=Donald+Duck&pg=PA30}} | |||

| * {{citation | last1=Mooney | first1= Jadwiga E. Pieper | title=''The Politics of Motherhood: Maternity and women's rights in twentieth-century Chile'' | chapter= Roasting the Duck:National Hegemony and Revolutionary Culture| year=2009 | publisher=]| isbn= 978-0822973614| chapter-url =https://books.google.com/books?id=HnEKKaWjcyAC&q=How+to+Read+Donald+Duck&pg=PA230}} | |||

| * {{citation |editor1-last=Smoodin|editor1-first=Eric | last1=Smoodin | first1= Eric | title=''Disney Discourse: Producing the Magic Kingdom'' | chapter= Introduction: How to Read Walt Disney| year=1994 | publisher=]| isbn= 978-1135216597| chapter-url =https://books.google.com/books?id=jlfRDnGgu6sC&q=How+to+Read&pg=PT169}} | |||

| * {{citation | last1=Tomlinson | first1= John | title=''Cultural Imperialism: A Critical Introduction'' | chapter= Reading Donald Duck: the ideology-critique of 'the imperialist text'| year=1991 | publisher=]| isbn= 978-0826450135| chapter-url =https://books.google.com/books?id=0CFMS0z5-gcC&q=How+to+Read+Donald+Duck&pg=PA41}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

| *Robert Boyd. "Uncle $crooge, Imperialist" ''Comics Journal'' #138 (October 1990), pp. 52–55. | * Robert Boyd. "Uncle $crooge, Imperialist" ''Comics Journal'' #138 (October 1990), pp. 52–55. | ||

| * Dwight Decker. "If This Be Imperialism..." ''Amazing Heroes'' #163 (April 15, 1989), pp. 55-57. An installment of the "Doc's Bookshelf" column. Analysis by a prominent comic book fan and ] expert. | |||

| *Dana Gabbard and Geoffrey Blum. "The Color of Truth is Gray." ''Walt Disney's Uncle Scrooge Adventures in Color'' #24 (1997), pp. 23–26. Critical analysis by two experts on ]. | * Dana Gabbard and Geoffrey Blum. "The Color of Truth is Gray." ''Walt Disney's Uncle Scrooge Adventures in Color'' #24 (1997), pp. 23–26. Critical analysis by two experts on ]. | ||

| *David Kunzle. "The Parts That Got Left Out of the Donald Duck Book, or, How Karl Marx Prevailed over Carl Barks." http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/archives/v6_2/kunzle/ ''Paper presented to the Marxism and Art History session of the College Art Association Meeting in Chicago, February 1976'' (1977), pp. 15–22. Kunzle's experiences in doing the English-language translation. | |||

| * A 2017 essay by Dorfman. | |||

| *Tadeusz, Tietze. "Hard Racism and Soft Stalinism" ''Comics Journal'' #142 (June 1991), pp. 32–34. | |||

| *{{interlanguage link|Dan Piepenbring|de}} (June 3, 2019) . ]. | |||

| *Bryan, Peter Cullen. , Chapter 1: "A Duck's Eye View of Europe": How to Read Donald Duck. Springer International Publishing, 2021. Examines the scope of the foreign popularity of Donald Duck as compared to the smaller role taken in America. | |||

| {{Disney comics navbox}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 01:06, 26 October 2024

1971 book by Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart | |

| Authors | Ariel Dorfman Armand Mattelart |

|---|---|

| Original title | Para leer al Pato Donald |

| Translator | David Kunzle |

| Language | Spanish |

| Publication date | 1971 |

| Publication place | Chile |

| Published in English | 1975 |

| Media type | |

How to Read Donald Duck (Spanish: Para leer al Pato Donald) is a 1971 book-length essay by Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart that critiques Disney comics from a Marxist point of view as capitalist propaganda for American corporate and cultural imperialism. It was first published in Chile in 1971, became a bestseller throughout Latin America and is still considered a seminal work in cultural studies. It was reissued in August 2018 to a general audience in the United States, with a new introduction by Dorfman, by OR Books.

Summary

The book's thesis is that Disney comics are not only a reflection of the prevailing ideology at the time (capitalism), but that they are also aware of this, and are active agents in spreading the ideology. To do so, Disney comics use images of the everyday world:

"Here lies Disney's inventive (product of his era), rejecting the crude and explicit scheme of adventure strips, that came up at the same time. The ideological background is without any doubt the same: but Disney, not showing any open repressive force, is much more dangerous. The division between Bruce Wayne and Batman is the projection of fantasy outside the ordinary world to save it. Disney colonizes the everyday world, at hand of ordinary man and his common problems, with the analgesic of a child's imagination".

— Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart, How to Read Donald Duck, p. 148

This closeness to everyday life is so only in appearance, because the world shown in the comics, according to the thesis, is based on ideological concepts, resulting in a set of natural rules that lead to the acceptance of particular ideas about capital, the developed countries' relationship with the Third World, gender roles, etc.

As an example, the book considers the lack of descendants of the characters. Everybody has an uncle or nephew, everybody is a cousin of someone, but nobody has fathers or sons. This non-parental reality creates horizontal levels in society, where there is no hierarchic order, except the one given by the amount of money and wealth possessed by each, and where there is almost no solidarity among those of the same level, creating a situation where the only thing left is crude competition. Another issue analyzed is the absolute necessity to have a stroke of luck for social mobility (regardless of the effort or intelligence involved), the lack of ability of the native tribes to manage their wealth, and others.

Publication history

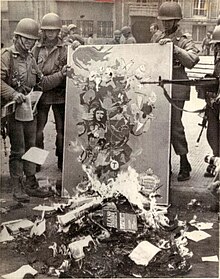

How to Read Donald Duck was written and published by Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso, belonging to the Pontifical Catholic University of Valparaíso, during the brief flowering of democratic socialism under the government of Salvador Allende and his Popular Unity coalition and is closely identified with the revolutionary politics of its era. In 1973, a coup d'état, secretly supported by the United States, brought in power the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. During Pinochet's regime, How to Read Donald Duck was banned and subject to book burning; its authors were forced into exile.

Outside Chile, How to Read Donald Duck became the most widely printed political text in Latin America for some time. It was translated into English, French, German, Portuguese, Dutch, Italian, Greek, Turkish, Swedish, Finnish, Danish, Japanese, and Korean and sold some 700.000 copies overall; by 1993, it had been reprinted 32 times by the publisher Siglo Veintiuno Editores.

A hardcover edition with a new introduction by Dorfman was published by OR Books in the United States in October 2018.

Reception

Thomas Andrae, who has written about Carl Barks, has criticized the thesis of Dorfman and Mattelart. Andrae writes that it is not true that Disney controlled the work of every cartoonist, and that cartoonists had almost completely free hands unlike those who worked in animation. According to Andrae, Carl Barks did not even know that his cartoons were read outside the United States in the 1950s. Lastly, he writes that Barks' cartoons include social criticism and even anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist references.

David Kunzle, who translated the book into English, spoke to Carl Barks for his introduction and came to a similar conclusion. He believes Barks projected his own experience as an underpaid cartoonist onto Donald Duck, and views some of his stories as satires "in which the imperialist Duckburgers come off looking as foolish as—and far meaner than—the innocent Third World natives".

See also

References

- "How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic". Pluto Press. March 2019.

- Lazare, Donald (1987). American Media and Mass Culture: Left Perspectives. University of California Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9780520044951.

- ^ Jason Jolley. Ariel Dorfman (1942–). The Literary Encyclopedia (2009)

- "Kaalgeplukt en doorgekookt: Ariel Dorfman over Donald Duck". De Groene Amsterdammer. 1 July 2009.

- Dorfman A., Mattelart A. Para leer al pato Donald p. 23. 1983. Besides the lack of descendants, there is a complete lack of libido or sexuality. The quote at the beginning of this chapter is remarkable:

- "Daisy: If you teach me how to skate this afternoon I'll give you what you have always wanted.

- Donald: Do you mean...?

- Daisy: Yes... my 1872 coin"

- Dorfman A., Mattelart A. Para leer al pato Donald p. 35. 1983.

- Dorfman A., Mattelart A. Para leer al pato Donald p. 139. 1983.

- Dorfman A., Mattelart A. Para leer al pato Donald p. 53. 1983.

- ^ Tomlinson (1991), p. 41–45

- McClennen (2010), p. 245-279

- Mendoza, Montaner, Llosa (2000), p. 199–201

- "How to Read Donald Duck". OR Books. 10 May 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Andrae, Thomas (2006), Carl Barks and the Disney Comic Book: Unmasking the Myth of Modernity, Univ. Press of Mississippi, ISBN 1578068584

- Kunzle, David. "The Parts That Got Left Out of the Donald Duck Book, or: How Karl Marx Prevailed Over Carl Barks". ImageTexT. ISSN 1549-6732. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

Sources

- Andrae, Thomas (2006), "Rereading Donald Duck", Carl Barks and the Disney Comic Book: Unmasking the Myth of Modernity, University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 978-1578068586

- Constantinou, Costas M. (2008), "Communications/excommunications: an interview with Armand Matellart", in Constantinou, Costas M.; Richmond, Oliver P.; Watson, Alison M.S. (eds.), Cultures and Politics of Global Communication: Volume 34, Review of International Studies, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521727112

- McClennen, Sophia A. (2010), Ariel Dorfman:An Aesthetics of Hope, Duke University Press, ISBN 978-0-8223-9195-1

- Mendoza, Plinio Apuleyo; Montaner, Carlos Alberto; Llosa, Alvaro Vargas (2000), "How to Read Donald Duck: Ariel Dorfman and Armand Matellart, 1972", Guide to the Perfect Latin American Idiot, Madison Books, ISBN 978-1-4616-6278-5

- Mirrlees, Tanner (2013), "Paradigms of Global Entertainment Media", Global Entertainment Media: Between Cultural Imperialism and Cultural Globalization, Routledge, ISBN 978-1136334658

- Mooney, Jadwiga E. Pieper (2009), "Roasting the Duck:National Hegemony and Revolutionary Culture", The Politics of Motherhood: Maternity and women's rights in twentieth-century Chile, University of Pittsburgh Press, ISBN 978-0822973614

- Smoodin, Eric (1994), "Introduction: How to Read Walt Disney", in Smoodin, Eric (ed.), Disney Discourse: Producing the Magic Kingdom, Routledge, ISBN 978-1135216597

- Tomlinson, John (1991), "Reading Donald Duck: the ideology-critique of 'the imperialist text'", Cultural Imperialism: A Critical Introduction, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0826450135

Further reading

- Robert Boyd. "Uncle $crooge, Imperialist" Comics Journal #138 (October 1990), pp. 52–55.

- Dwight Decker. "If This Be Imperialism..." Amazing Heroes #163 (April 15, 1989), pp. 55-57. An installment of the "Doc's Bookshelf" column. Analysis by a prominent comic book fan and Carl Barks expert.

- Dana Gabbard and Geoffrey Blum. "The Color of Truth is Gray." Walt Disney's Uncle Scrooge Adventures in Color #24 (1997), pp. 23–26. Critical analysis by two experts on Carl Barks.

- How to Read Donald Trump: On Burning Books but Not Ideas A 2017 essay by Dorfman.

- Dan Piepenbring [de] (June 3, 2019) The Book That Exposed the Cynical Politics of Donald Duck. The New Yorker.

- Bryan, Peter Cullen. Creation, Translation, and Adaptation in Donald Duck Comics: The Dream of Three Lifetimes, Chapter 1: "A Duck's Eye View of Europe": How to Read Donald Duck. Springer International Publishing, 2021. Examines the scope of the foreign popularity of Donald Duck as compared to the smaller role taken in America.