| Revision as of 19:56, 21 October 2016 edit190.10.8.213 (talk) rv edit of turkic terrorist← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:54, 11 December 2024 edit undoWbm1058 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators265,445 editsm redirect bypass from Hephtalites to Hephthalites using popups | ||

| (203 intermediate revisions by 98 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|4th–6th-century Bactrian-speaking nomadic people of Central Asia}} | |||

| {{distinguish|Zion (disambiguation){{!}}Zionites}} | |||

| {{distinguish|Zionites (disambiguation){{!}}Zionites|Xiongnu}} | |||

| '''Xionites''', '''Chionites''', or '''Chionitae''' (]: ''Xiyon''; Avestan: ''Xiiaona''; ]: Xwn; ]: ]), or '''Hunni''', '''Yun''' or '''Xūn''' (獯), were an ]<ref name="W.Felix">{{cite encyclopedia |last= Felix |first=Wolfgang | title= CHIONITES | encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Iranica Online Edition | accessdate=2012-09-03|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/chionites-lat}}</ref> who were prominent in ] and ]. | |||

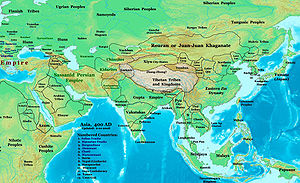

| ] | |||

| '''Xionites''', '''Chionites''', or '''Chionitae''' (]: ''Xiyōn'' or ''Hiyōn''; ]: ''X́iiaona-''; ] ''xwn''; ] ''Xyōn'') were a nomadic people in the ] regions of ] and ].<ref name="W.Felix">{{cite encyclopedia |last= Felix |first=Wolfgang | title= CHIONITES | encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Iranica Online Edition | access-date=2012-09-03|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/chionites-lat}}</ref> | |||

| The Xionites appear to be synonymous with the ]s of the ] regions of ],<ref>], 2013, ''The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe'', Cambridge UK/New York, ], pp. 5, 36–38.</ref> and possibly also the ] of ], who were in turn connected ] to the ] in Chinese history.<ref>Schuessler, Axel (2014). "Phonological Notes on Hàn Period Transcriptions of Foreign Names and Words" (PDF). Studies in Chinese and Sino-Tibetan Linguistics: Dialect, Phonology, Transcription and Text. Language and Linguistics Monograph Series. Taipei, Taiwan: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica (53). p. 257, 264. quote: "‘Xiōngnú’ (1-6 匈奴 hɨoŋ-nɑ < *hoŋ-nâ) may well be a regular Hàn period (or even pre-Hàn) rendering of ‘Huns’, i.e. foreign Hŏna or Hŭna, cf. Skt. Hūṇa (but with a long vowel). 1-7 匈奴 Xiōngnú hɨoŋ-nɑ < *hoŋ-nâ 318 B.C.E. Skt. Hūṇa ‘Huns’."</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Chinese|c=狁|p=Yǔn}} | |||

| They were first described by the Roman historian, ], who was in Bactria during 356–357 CE; he described the ''Chionitæ'' as living with the ].<ref>Original reports on the "Chionitae" by ]:<br />Mention with the Euseni/ ] : .<br />Mention with the ]: .<br />Mention with ]: <br />Mention at the ]: and </ref> Ammianus indicates that the Xionites had previously lived in ] and, after entering Bactria, became ]s of the ], were influenced culturally by them and had adopted the ]. They had attacked the ],<ref name="W.Felix" /><ref name="LINK">{{cite encyclopedia |last= Shapur Shahbazi |first= A | title= SASANIAN DYNASTY | encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Iranica Online Edition | access-date=2012-09-03|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/sasanian-dynasty}}</ref> but later (led by a chief named ]), served as mercenaries in the ] Sassanian army. | |||

| Within the Xionites, there seem to have been two main subgroups, which were known in the ] by names such as ''Karmir Xyon'' and ''Spet Xyon''. The prefixes ''karmir'' ("red") and ''speta'' ("white") likely refer to ] traditions in which particular ]. The ''Karmir Xyon'' were known in European sources as the ''Kermichiones'' or "Red Huns", and some scholars have identified them with the ] and/or ]. The ''Spet Xyon'' or "White Huns" appear to have been the known in ] by the cognate name ''Sveta-huna'', and are often identified, controversially, with the ]. | |||

| == Origins == | |||

| It is difficult to determine the ethnic composition of the Xionites.<ref name="W.Felix" /> Simocatta, Menander, and Priscus provide evidence that the Xionites were somewhat different from the ]s although, Frye suggested that the Hepthalites may have been a prominent tribe or clan of the Xionites.<ref>]; </ref> They followed their versions of Buddhism and Shaivism mixed with animism. | |||

| == Origins and culture == | |||

| In 1932 Sir ] wrote:<ref name="Iranian Studies 1932">], ''Iranian Studies'', Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. BSOAS, vol. 6, No. 4 (1932)</ref> | |||

| {{See also|Origin of the Huns}} | |||

| ] horseman on the so-called "]" in the ], 460–479 CE.<ref></ref>]] | |||

| The original culture of the Xionites and their geographical ] are uncertain. They appear to have originally followed ] religious beliefs,{{citation needed|date=October 2017}} which mixed later with varieties of ] {{citation needed|date=October 2017}} and ].{{citation needed|date=October 2017}} It is difficult to determine their ethnic composition.<ref name="W.Felix" /> | |||

| {{cquote|Xyon. This name is familiar in Pahlavi and Avestan texts. It would appear to be a name of an enemy of the Iranian people in Avestan times, transferred later to the Huns owing to similarity of sound, as Tur was adapted to Turk in Pahlavi. In the present passage (a passage from the Pahlavi book of Bahman Yasht) three divisions of this people seem to be recognized, the Xyon with the Turks, the Karmir (Red) Xyon, and the White Xyon.}} | |||

| Differences between the Xionites, the Huns who invaded Europe in the 4th century, and the Turks were emphasised by ] (1944), who suggested that the name "Chyon", originally that of an unrelated people, was "transferred later to the Huns owing to the similarity of sound". The Chyon who appeared in the 4th century, in the steppes on the northeastern frontier of Persia were probably a branch of the Huns that appeared shortly afterwards in Europe. The Huns appear to have attacked and conquered the ], then living between the ] and the ] about 360 AD, and the first mention of the ] was in 356 AD.<ref>{{cite journal|title = On the Greek Sources for the History of the Turks in the Sixth Century | |||

| In 1944 ] wrote:<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| |title = On the Greek Sources for the History of the Turks in the Sixth Century | |||

| |last = Macartney | |last = Macartney | ||

| |first = C. A. | |first = C. A. | ||

| | |

|author-link = Carlile Aylmer Macartney | ||

| |journal = ] | |journal = ] | ||

| |publisher = ] | |publisher = ] | ||

| Line 27: | Line 28: | ||

| |pages = 266–75 | |pages = 266–75 | ||

| |jstor = 609313 | |jstor = 609313 | ||

| |doi = 10.1017/S0041977X00072451 | |||

| |via = ] | |||

| |s2cid = 161863098 | |||

| |registration = y | |||

| }}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

| At least some Turkic tribes were involved in the formation of the Xionites, despite their later character as an ], according to Richard Nelson Frye (1991): "Just as later nomadic empires were confederations of many peoples, we may tentatively propose that the ruling groups of these invaders were, or at least included, Turkic-speaking tribesmen from the east and north, although most probably the bulk of the people in the confederation of Chionites... spoke an Iranian language.... This was the last time in the history of Central Asia that Iranian-speaking nomads played any role; hereafter all nomads would speak Turkic languages".<ref>], "''Pre-Islamic and early Islamic cultures in Central Asia''" in "''Turko-Persia in historical perspective''", edited by , Cambridge University Press, 1991. pg 49.</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|We must consider briefly a third nation playing a role in our sources: the Kermichiones. Who were these people? They cannot have been the Turks-Toue-Kioue, since their embassy reached Constantinople while the Avars were still negotiating with Rome for settlement inside the frontier-probably, therefore, as early as AD 558, whereas the true Turks appeared there first in 568; further, their ruler's name was `Aσκήλτ or Scultor, while the Khagan of the Turks at that time was Silzabul, Dizabul, or Istämi. Neither can they have been the Juan Juan, as Marquart suggests; nor the Epthalites, who were well known to the Byzantines and would not have been described in this way. Moreover, the Epthalites were known as White Huns, and Mr. Bailey has pointed out that the word Karmir xyon, meaning Red Chyon, occurs in a Pahlavi text in juxtaposition with SpEt xyon, White Chyon. The name Chyon, originally that of some other race, was "transferred later to the Huns owing to the similarity of sound". The nation can hardly be other than that which appears in the 4th century, under the name of Chionits, in the steppes on the north-west frontier of Persia. These Chionites were probably a branch of the Huns, the other branch of which afterwards appeared in Europe, the latter appear to have attacked and conquered by the Alans, then living between the Urals and the Volga about AD 360, while the first mention of the Chionites is dated AD 356. In the 5th century the name is replaced by that of the Kushan or of the Kidarite Huns, who are clearly identical with the Kushan.}} | |||

| The proposition that the Xionites probably originated as an Iranian tribe was put forward by Wolfgang Felix in ''Encyclopedia Iranica'' (1992).<ref name="W.Felix" /> | |||

| A more recent specialist, ]<ref>], "''Pre-Islamic and early Islamic cultures in Central Asia''" in "''Turko-Persia in historical perspective''", edited by , Cambridge University Press, 1991. pg 49.</ref> wrote in 1991: | |||

| In 2005, As-Shahbazi suggested that they were originally a ] who had mixed with Iranian tribes in Transoxiana and Bactria, where they adopted the ].<ref name="LINK" /> Likewise, ] wrote that the Chionite confederation included earlier Iranian nomads as well as ] and ] elements.<ref>{{cite book |first=Peter B. |last=Golden |author-link=Peter B. Golden |year=2005 |chapter=Turks and Iranians: a cultural sketch |editor-first=Lars |editor-last=Johanson |editor2-first=Christiane |editor2-last=Bulut |title=Turkic-Iranian Contact Areas: Historical and Linguistic Aspects |series=Turcologica |volume=62 |location=Wiesbaden |page=19 |isbn=3-447-05276-7 }}</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|Just as later nomadic empires were confederations of many peoples, we may tentatively propose that the ruling groups of these invaders were, or at least included, Turkic-speaking tribesmen from the east and north, although most probably the bulk of the people in the confederation of Chionites and then Hephtalites spoke an Iranian language (...) This was the last time in the history of Central Asia that Iranian-speaking nomads played any role; hereafter all nomads would speak Turkic languages.}} | |||

| == History == | |||

| In 1992 Wolfgang Felix<ref name="W.Felix" /> considered the Xionites a tribe of probable ] origin that was prominent in Bactria and Transoxania in late antiquity. | |||

| The defeat of the Xiongnu in 89 CE by ] forces at the ] and subsequent Han campaigns against them, led by ] may have been a factor in the ethnogenesis of the Xionites and their migration into Central Asia. | |||

| Xionite tribes reportedly organised themselves into four main hordes: "Black" or northern (beyond the ]), "Blue" or eastern (in Tianshan), "White" or western (possibly the ]), around ], and the "Red" or southern (] and/or ]), south of the ]. Artefacts found from the area they inhabited dating from their period indicate their totem animal seems to have been the (rein)deer. | |||

| According to A.S. Shahbazi (2005),<ref name="LINK" /> the Xionites were a "Hunnic" people who by the early 4th century had mixed with north Iranian elements in Transoxiana, adopted the ] language, and threatened Persia. | |||

| The Xionites are best documented in southern ] from the late 4th century AD until the mid-5th century AD. | |||

| === Chionite rulers of Chach === | |||

| == History == | |||

| ], with an appearance similar to that on the coinage of the Chionites of ]. 5th–7th century CE.<ref name="MF" />]] | |||

| Some Chionites are known to have ruled in Chach (modern ]), at the foot of the ], between the middle of the 4th century CE to the 6th century CE.<ref name="MF">{{cite journal |last1=Fedorov |first1=Michael |title=Chionite Rulers of Chach in the Middle of the Fourth to the Beginning of the Seventh Century (According to the Data of Numismatics) |journal=Iran |date=2010 |volume=48 |pages=59–67 |doi=10.1080/05786967.2010.11864773 |jstor=41431217 |s2cid=163653671 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/41431217.pdf |issn=0578-6967}}</ref> A special type of coinage has been attributed to them, where they appear in portraits as diademed kings, facing right, with a ] in the shape of an X, and a circular Sogdian legend. They also often appear with a crescent over the head.<ref name="MF" /> It has been suggested that the facial characteristics and the hairstyle of these Chionite rulers as they appear on their coinage, are similar to those appearing on the murals of ] further south.<ref name="MF" /> | |||

| <gallery widths="200px" heights="100px" perrow="4"> | |||

| ===Conquest of Bactria=== | |||

| File:Chach. Uncertain ruler. Circa AD 625-725.jpg|Chionite coinage of Chach | |||

| {{see also|Kidarites}} | |||

| File:Chach. Uncertain ruler Chanurnak or Chanubek. Circa AD 625-725.jpg|Chionite coinage of Chach | |||

| Xionite campaigns are better documented in connection with the history of ], particularly during the second half of the 4th century AD until the mid-5th century AD. | |||

| File:Portrait on a coin of Chach.jpg|Portrait on a coin of Chach. | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| === Kidarites === | |||

| They organised themselves into Northern "Black" (beyond the ]), ] or Southern "Red" (in Hindu Kush south of the ]), Eastern "Blue" (in Tianshan), and Western ] or "White" (around Khiva) hordes. Artefacts found from the area they inhabited dating from their period indicate their totem animal seems to have been the (rein)deer. An inscription on the walls of the royal palace in Persepolis about Darius's empire calls them ''Hunae''. It appears that a combination of both the ] and ]'s efforts are responsible for their first appearance in the West. The ] historian ] (5th century), in his "History of Armenia," introduces the ''Hunni'' near the ] and goes on to describe how they captured the city of ] (] "Kush") sometime between 194 and 214 which is why the ] called that city ''Hunuk''.<ref>{{dead link|date=July 2016 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> | |||

| {{See also|Kidarites}} | |||

| ] king ], {{circa|350}}–386 AD.<ref></ref>]] | |||

| Sometime between 194 and 214, according to the ] historian ] (5th century), ''Hunni'' (probably the Kidarites) captured the city of ] (Armenian name: ''Kush'') .<ref></ref> According to Armenian sources, Balkh became the capital of the Hunni. | |||

| At the end of the 4th century AD, the Kidarites were pushed into ], after a new wave of invaders from the north, the Alchon, entered Bactria.<ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071013231126/http://starnarcosis.net/obsidian/siberia.html |date=October 13, 2007 }}</ref> | |||

| According to the Armenian sources their capital was at ] (Armenian: Kush). Their most famous rulers were called the ]. | |||

| === Clashes with the Sasanians === | |||

| At the end of the 4th century AD, a new wave of Hunnic tribes (Alchon) invaded Bactria, pushing the Kidarites into ].<ref> {{wayback|url=http://starnarcosis.net/obsidian/siberia.html |date=20071013231126 }}</ref> | |||

| Early confrontations between the ] of ] with the Xionites were described by ]: he reports that in 356 CE, Shapur II was taking his winter quarters on his eastern borders, "repelling the hostilities of the bordering tribes" of the Xionites and the ''Euseni'', a name often amended to ''Cuseni'' (meaning the ]).<ref>{{cite book |last1=Scheers |first1=Simone |last2=Quaegebeur |first2=Jan |title=Studia Paulo Naster Oblata: Orientalia antiqua |date=1982 |publisher=Peeters Publishers |isbn=9789070192105 |page=55 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GlsbsTTwxjYC&pg=PA55 |language=fr}}</ref><ref>Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman History. London: Bohn (1862) </ref> | |||

| Shapur made a treaty of alliance with the Chionites and the Gelani in 358 CE.<ref>Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman History. London: Bohn (1862) </ref> | |||

| === Alchon === | === Alchon === | ||

| {{Main|Alchon}} | |||

| {{see also|Hephthalite|Huna people|Uar}} | |||

| ] is suggested by a portrait of ], king of the ] c. 430 – 490 AD.<ref name="CC">The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Michael Maas </ref>]] | |||

| ''Alchon'' or ''Alχon'' (Uarkhon) became the new name of the Xionites in 460 when ] united the ] with the Xionites under his ] ruling élite. | |||

| In 460, ] reportedly united a ] ruling élite with elements of the ] and Xionites as ''Alchon'' (or ''Alχon''). {{citation needed|date=October 2017}} when.{{citation needed|date=October 2017}} | |||

| At the end of the 5th century the Alchon invaded |

At the end of the 5th century the Alchon invaded North India where they were known as the ].{{citation needed|date=October 2017}} In India the Alchon were not distinguished from their immediate Hephthalite predecessors,{{citation needed|date=October 2017}} and both are known as Sveta-Hunas there.{{citation needed|date=October 2017}} Perhaps complimenting this term, ] (527–565) wrote that they were white skinned,{{citation needed|date=October 2017}} had an organized kingship, and that their life was not wild/nomadic and they lived in cities. | ||

| The Alchon were noted for their distinctive coins, minted in Bactria in the 5th and 6th centuries. The name ''Khigi'', inscribed in Bactrian script on one of the coins, and ''Narendra'' on another, have led some scholars {{who|date=October 2017}} to believe that the Hephthalite kings Khingila and Narana were of the AlChoNo tribe.{{vague|date=October 2017}} {{citation needed|date=October 2017}} They imitated the earlier style of their Hephthalite predecessors, the Kidarite Hun successors to the Kushans. In particular the Alchon style imitates the coins of Kidarite Varhran I (syn. Kushan Varhran IV).{{citation needed|date=April 2012}} | |||

| Although the power of the Alchon in Bactria was shattered in the 560's by a combination of ] and proto-Turkic forces, the last Hephthal king Narana/Narendra managed to maintain some kind of rule between 570 and 600 AD over the 'nspk' or 'napki' or 'nezak' tribes that remained after most of the Alchon had fled to the west, where they became known as the ]. | |||

| The earliest coins of the Alchon have several distinctive features: 1) the king's head is presented in an elongated form to reflect the Alchon practice of head binding; 2) The characteristic bull/lunar tamgha of the Alchon is represented on the obverse of the coins.<ref>Notes on the Evolution of Alchon Coins, Pankaj Tandon, http://coinindia.com/Alchon.pdf</ref> | |||

| The Alchon were called Varkhon or Varkunites (Ouar-Khonitai) by ] (538-582) literally referring to the Uar and Hunnoi. Around 630, ] wrote that the European "Avars" were initially composed of two nations, the Uar and the Hunnoi tribes. He wrote that: "...the Barsilt, the Unogurs and the Sabirs were struck with horror... and honoured the newcomers with brilliant gifts..."<ref name="Simokattes">Theophilactus Simocatta, Historiae, -Ed. C. deBoor. Lipsiae, 1887, ps.251, 258</ref> when the Avars first arrived in their lands in 555AD. | |||

| === Hephthalites === | |||

| The Hephthalites, or White Huns, were a nomadic tribe who conquered large parts of the eastern middle-east and may have originally been part of the Xionites. | |||

| Alchon Huns refers to a tribe which minted coins in Bactria in the 5th and 6th centuries. The name Khigi on one of the coins and Narendra on another has led some scholars of the area to believe that the Hephthalite ]s Khingila and Narana were of the AlChoNo tribe inscribed in Bactrian script on the coins in question. They imitated the earlier style of their Hephthalite predecessors, the Kidarite Hun successors to the Kushans. In particular the Alchon style imitates the coins of Kidarite Varhran I (syn. Kushan Varhran IV).{{citation needed|date=April 2012}} | |||

| {{Main|Hephthalites}} | |||

| {{expand section|date=June 2018}} | |||

| === Nezak === | |||

| The earliest coins of Alchon ] have several distinctive features: 1) the king’s head is presented in an elongated form to reflect the Alchon practice of head binding; 2) The characteristic bull/lunar tamgha of the Alchon is represented on the obverse of the coins<ref>Notes on the Evolution of Alchon Coins, Pankaj Tandon, http://coinindia.com/Alchon.pdf</ref> | |||

| ] ruler, {{circa|460}}–560 CE.]] | |||

| {{Main|Nezak}} | |||

| Although the power of the Huna in Bactria was shattered in the 560s by a combination of ] and ] forces, the last Hephthalite king Narana/Narendra managed to maintain some kind of rule between 570 and 600 AD over the ''nspk'', ''napki'' or ] tribes that remained. | |||

| === Red Huns and White Huns === | |||

| The name ''Xyon'' is found in ] and ] texts.{{citation needed|date=November 2015}} In the Avestan tradition (Yts. 9.30-31, 19.87) the ''Xiiaona'' were characterized as enemies of ], the patron of ].<ref name="W.Felix" /> In the later Pahlavi tradition, the Red Huns (Karmir Xyon) and White Huns (Spet Xyon) are mentioned.<ref name="W.Felix" /> The Red Huns of the Pahlavi tradition (7th century)<ref> in ''Encyclopædia Iranica'' by W. Sundermann</ref> have been identified by ] as the ''Kermichiones'' or ''Ermechiones''.<ref name="W.Felix" /> According to Bailey<ref>(Bailey, 1954, pp.12-16; 1932, p. 945),</ref> the Hara Huna of Indian sources are to be identified with the Karmir Xyon of the Avesta. Similarly he identifies the Sveta Huna of Indian sources with the Spet Xyon of the Avesta. Bailey argues that the name ''Xyon'' was transferred to the '']'' owing to similarity of sound, as '']'' was adapted to '']'' in Pahlavi tradition.<ref name="Iranian Studies 1932" /> It is necessary therefore to differentiate between "Kermichiones/Ermechiones", "Red Huns" or "Hara Huna", identified with the ] dynasty, and "Xionites" "White Huns" or "Sveta Huna", identified with the ] dynasty. | |||

| {{expand section|date=June 2018}} | |||

| Later, the Armenian Patriarch John (c. 728) mentions an ancient town of ''Hunor's'' foundation (Hunoracerta) in the ] region, suggesting a connection to the ]. The Armenian ] mentions also that there are "Huns" living amongst the peoples of the ]. | |||

| === Identity of the ''Karmir Xyon'' and ''White Xyon'' === | |||

| Bailey argues that the Pahlavi name ''Xyon'' may be read as the Indian '']'' owing to the similarity of sound.<ref name="Iranian Studies 1932">Bailey, H. W. ''Iranian Studies'', Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. BSOAS, vol. 6, No. 4 (1932)</ref> In the Avestan tradition (Yts. 9.30-31, 19.87) the ''Xiiaona'' were characterized as enemies of ], the patron of ].<ref name="W.Felix" /> | |||

| In the later Pahlavi tradition, the ''Karmir Xyon'' ("Red Xyon") and ''Spet Xyon'' ("White Xyon") are mentioned.<ref name="W.Felix" /> The Red Xyon of the Pahlavi tradition (7th century)<ref> in ''Encyclopædia Iranica'' by W. Sundermann</ref> have been identified by Bailey as the ''Kermichiones'' or ''Ermechiones''.<ref name="W.Felix" /> | |||

| According to Bailey, the ''Hara Huna'' of Indian sources are to be identified with the ''Karmir Xyon'' of the Avesta.<ref>(Bailey, 1954, pp.12-16; 1932, p. 945),</ref> Similarly he identifies the ''Sveta Huna'' of Indian sources with the ''Spet Xyon'' of the ''Avesta''. While the ] are not mentioned in Indian sources, they are sometimes also linked to the ''Spet Xyon'' (and therefore possibly to the ''Sveta Huna''). | |||

| More controversially, the names ''Karmir Xyon'' and ''Spet Xyon'' are often rendered as "Red Huns" and "White Huns", reflecting speculation that the Xyon were linked to Huns recorded simultaneously in Europe. | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == |

== References == | ||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

| == Sources == | |||

| * {{cite journal |last1=Cribb|first1=Joe|editor-last = Alram | editor-first = M. | title=The Kidarites, the numismatic evidence.pdf |date=2010 |pages=91–146|publisher= Coins, Art and Chronology II|url=https://www.academia.edu/38112559|url-access=registration}} | |||

| * {{cite book |first1=Touraj |last1=Daryaee|first2=Khodadad|last2=Rezakhani|editor1-last=Daryaee |editor1-first=Touraj |title=King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE – 651 CE) |date=2017 |publisher=UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies |chapter=The Sasanian Empire|pages=1–236|isbn=978-0-692-86440-1 | |||

| |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=unTjswEACAAJ}} | |||

| * {{cite journal |last1=Payne|first1=Richard|title=The Making of Turan: The Fall and Transformation of the Iranian East in Late Antiquity |journal=Journal of Late Antiquity |date=2016 |volume=9 |pages=4–41 |publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press| location = Baltimore|url=https://www.academia.edu/27438947|url-access=registration|doi=10.1353/jla.2016.0011|s2cid=156673274}} | |||

| * {{cite book | title = ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity | year = 2017 | publisher = Edinburgh University Press | last = Rezakhani | first = Khodadad | chapter = East Iran in Late Antiquity| pages = 1–256 | isbn = 978-1-4744-0030-5 | jstor = 10.3366/j.ctt1g04zr8 }} | |||

| == External links == | == External links == | ||

| * {{Iranica|chionites-lat}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Huns}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 12:54, 11 December 2024

4th–6th-century Bactrian-speaking nomadic people of Central Asia Not to be confused with Zionites or Xiongnu.

Xionites, Chionites, or Chionitae (Middle Persian: Xiyōn or Hiyōn; Avestan: X́iiaona-; Sogdian xwn; Pahlavi Xyōn) were a nomadic people in the Central Asian regions of Transoxiana and Bactria.

The Xionites appear to be synonymous with the Huna peoples of the South Asian regions of classical/medieval India, and possibly also the Huns of European late antiquity, who were in turn connected onomastically to the Xiongnu in Chinese history.

They were first described by the Roman historian, Ammianus Marcellinus, who was in Bactria during 356–357 CE; he described the Chionitæ as living with the Kushans. Ammianus indicates that the Xionites had previously lived in Transoxiana and, after entering Bactria, became vassals of the Kushans, were influenced culturally by them and had adopted the Bactrian language. They had attacked the Sassanid Empire, but later (led by a chief named Grumbates), served as mercenaries in the Persian Sassanian army.

Within the Xionites, there seem to have been two main subgroups, which were known in the Iranian languages by names such as Karmir Xyon and Spet Xyon. The prefixes karmir ("red") and speta ("white") likely refer to Central Asian traditions in which particular colours symbolised the cardinal points. The Karmir Xyon were known in European sources as the Kermichiones or "Red Huns", and some scholars have identified them with the Kidarites and/or Alchon. The Spet Xyon or "White Huns" appear to have been the known in South Asia by the cognate name Sveta-huna, and are often identified, controversially, with the Hephthalites.

Origins and culture

See also: Origin of the Huns

The original culture of the Xionites and their geographical urheimat are uncertain. They appear to have originally followed animist religious beliefs, which mixed later with varieties of Buddhism and Shaivism. It is difficult to determine their ethnic composition.

Differences between the Xionites, the Huns who invaded Europe in the 4th century, and the Turks were emphasised by Carlile Aylmer Macartney (1944), who suggested that the name "Chyon", originally that of an unrelated people, was "transferred later to the Huns owing to the similarity of sound". The Chyon who appeared in the 4th century, in the steppes on the northeastern frontier of Persia were probably a branch of the Huns that appeared shortly afterwards in Europe. The Huns appear to have attacked and conquered the Alans, then living between the Urals and the Volga about 360 AD, and the first mention of the Chyon was in 356 AD.

At least some Turkic tribes were involved in the formation of the Xionites, despite their later character as an Eastern Iranian people, according to Richard Nelson Frye (1991): "Just as later nomadic empires were confederations of many peoples, we may tentatively propose that the ruling groups of these invaders were, or at least included, Turkic-speaking tribesmen from the east and north, although most probably the bulk of the people in the confederation of Chionites... spoke an Iranian language.... This was the last time in the history of Central Asia that Iranian-speaking nomads played any role; hereafter all nomads would speak Turkic languages".

The proposition that the Xionites probably originated as an Iranian tribe was put forward by Wolfgang Felix in Encyclopedia Iranica (1992).

In 2005, As-Shahbazi suggested that they were originally a Hunnish people who had mixed with Iranian tribes in Transoxiana and Bactria, where they adopted the Kushan-Bactrian language. Likewise, Peter B. Golden wrote that the Chionite confederation included earlier Iranian nomads as well as Proto-Mongolic and Turkic elements.

History

The defeat of the Xiongnu in 89 CE by Han dynasty forces at the Battle of Ikh Bayan and subsequent Han campaigns against them, led by Ban Chao may have been a factor in the ethnogenesis of the Xionites and their migration into Central Asia.

Xionite tribes reportedly organised themselves into four main hordes: "Black" or northern (beyond the Jaxartes), "Blue" or eastern (in Tianshan), "White" or western (possibly the Hephthalites), around Khiva, and the "Red" or southern (Kidarites and/or Alchon), south of the Oxus. Artefacts found from the area they inhabited dating from their period indicate their totem animal seems to have been the (rein)deer. The Xionites are best documented in southern Central Asia from the late 4th century AD until the mid-5th century AD.

Chionite rulers of Chach

Some Chionites are known to have ruled in Chach (modern Tashkent), at the foot of the Altai Range, between the middle of the 4th century CE to the 6th century CE. A special type of coinage has been attributed to them, where they appear in portraits as diademed kings, facing right, with a tamgha in the shape of an X, and a circular Sogdian legend. They also often appear with a crescent over the head. It has been suggested that the facial characteristics and the hairstyle of these Chionite rulers as they appear on their coinage, are similar to those appearing on the murals of Balalyk Tepe further south.

Kidarites

See also: Kidarites

Sometime between 194 and 214, according to the Armenian historian Moses of Khorene (5th century), Hunni (probably the Kidarites) captured the city of Balkh (Armenian name: Kush) . According to Armenian sources, Balkh became the capital of the Hunni.

At the end of the 4th century AD, the Kidarites were pushed into Gandhara, after a new wave of invaders from the north, the Alchon, entered Bactria.

Clashes with the Sasanians

Early confrontations between the Sasanian Empire of Shapur II with the Xionites were described by Ammianus Marcellinus: he reports that in 356 CE, Shapur II was taking his winter quarters on his eastern borders, "repelling the hostilities of the bordering tribes" of the Xionites and the Euseni, a name often amended to Cuseni (meaning the Kushans).

Shapur made a treaty of alliance with the Chionites and the Gelani in 358 CE.

Alchon

Main article: Alchon

In 460, Khingila I reportedly united a Hephthalite ruling élite with elements of the Uar and Xionites as Alchon (or Alχon). when.

At the end of the 5th century the Alchon invaded North India where they were known as the Huna. In India the Alchon were not distinguished from their immediate Hephthalite predecessors, and both are known as Sveta-Hunas there. Perhaps complimenting this term, Procopius (527–565) wrote that they were white skinned, had an organized kingship, and that their life was not wild/nomadic and they lived in cities.

The Alchon were noted for their distinctive coins, minted in Bactria in the 5th and 6th centuries. The name Khigi, inscribed in Bactrian script on one of the coins, and Narendra on another, have led some scholars to believe that the Hephthalite kings Khingila and Narana were of the AlChoNo tribe. They imitated the earlier style of their Hephthalite predecessors, the Kidarite Hun successors to the Kushans. In particular the Alchon style imitates the coins of Kidarite Varhran I (syn. Kushan Varhran IV).

The earliest coins of the Alchon have several distinctive features: 1) the king's head is presented in an elongated form to reflect the Alchon practice of head binding; 2) The characteristic bull/lunar tamgha of the Alchon is represented on the obverse of the coins.

Hephthalites

The Hephthalites, or White Huns, were a nomadic tribe who conquered large parts of the eastern middle-east and may have originally been part of the Xionites.

Main article: Hephthalites| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2018) |

Nezak

Although the power of the Huna in Bactria was shattered in the 560s by a combination of Sassanid and Turkic forces, the last Hephthalite king Narana/Narendra managed to maintain some kind of rule between 570 and 600 AD over the nspk, napki or Nezak tribes that remained.

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2018) |

Identity of the Karmir Xyon and White Xyon

Bailey argues that the Pahlavi name Xyon may be read as the Indian Huna owing to the similarity of sound. In the Avestan tradition (Yts. 9.30-31, 19.87) the Xiiaona were characterized as enemies of Vishtaspa, the patron of Zoroaster.

In the later Pahlavi tradition, the Karmir Xyon ("Red Xyon") and Spet Xyon ("White Xyon") are mentioned. The Red Xyon of the Pahlavi tradition (7th century) have been identified by Bailey as the Kermichiones or Ermechiones.

According to Bailey, the Hara Huna of Indian sources are to be identified with the Karmir Xyon of the Avesta. Similarly he identifies the Sveta Huna of Indian sources with the Spet Xyon of the Avesta. While the Hephthalite are not mentioned in Indian sources, they are sometimes also linked to the Spet Xyon (and therefore possibly to the Sveta Huna).

More controversially, the names Karmir Xyon and Spet Xyon are often rendered as "Red Huns" and "White Huns", reflecting speculation that the Xyon were linked to Huns recorded simultaneously in Europe.

See also

References

- ^ Felix, Wolfgang. "CHIONITES". Encyclopædia Iranica Online Edition. Retrieved 2012-09-03.

- Hyun Jin Kim, 2013, The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe, Cambridge UK/New York, Cambridge University Press, pp. 5, 36–38.

- Schuessler, Axel (2014). "Phonological Notes on Hàn Period Transcriptions of Foreign Names and Words" (PDF). Studies in Chinese and Sino-Tibetan Linguistics: Dialect, Phonology, Transcription and Text. Language and Linguistics Monograph Series. Taipei, Taiwan: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica (53). p. 257, 264. quote: "‘Xiōngnú’ (1-6 匈奴 hɨoŋ-nɑ < *hoŋ-nâ) may well be a regular Hàn period (or even pre-Hàn) rendering of ‘Huns’, i.e. foreign Hŏna or Hŭna, cf. Skt. Hūṇa (but with a long vowel). 1-7 匈奴 Xiōngnú hɨoŋ-nɑ < *hoŋ-nâ 318 B.C.E. Skt. Hūṇa ‘Huns’."

- Original reports on the "Chionitae" by Ammianus Marcellinus:

Mention with the Euseni/ Cuseni : 16.9.4.

Mention with the Gelani: 17.5.1.

Mention with Shapur II: 18.7.21

Mention at the siege of Amida: 19.2.3 and 19.1.7-19.2.1 - ^ Shapur Shahbazi, A. "SASANIAN DYNASTY". Encyclopædia Iranica Online Edition. Retrieved 2012-09-03.

- British Museum notice

- Macartney, C. A. (1944). "On the Greek Sources for the History of the Turks in the Sixth Century". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 11 (2). School of Oriental and African Studies: 266–75. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00072451. ISSN 1474-0699. JSTOR 609313. S2CID 161863098.

- Richard Nelson Frye, "Pre-Islamic and early Islamic cultures in Central Asia" in "Turko-Persia in historical perspective", edited by Robert L. Canfield, Cambridge University Press, 1991. pg 49.

- Golden, Peter B. (2005). "Turks and Iranians: a cultural sketch". In Johanson, Lars; Bulut, Christiane (eds.). Turkic-Iranian Contact Areas: Historical and Linguistic Aspects. Turcologica. Vol. 62. Wiesbaden. p. 19. ISBN 3-447-05276-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Fedorov, Michael (2010). "Chionite Rulers of Chach in the Middle of the Fourth to the Beginning of the Seventh Century (According to the Data of Numismatics)" (PDF). Iran. 48: 59–67. doi:10.1080/05786967.2010.11864773. ISSN 0578-6967. JSTOR 41431217. S2CID 163653671.

- CNG Coins

- Chinese

- Nomads of the Steppe Archived October 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Scheers, Simone; Quaegebeur, Jan (1982). Studia Paulo Naster Oblata: Orientalia antiqua (in French). Peeters Publishers. p. 55. ISBN 9789070192105.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman History. London: Bohn (1862) XVI-IX

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman History. London: Bohn (1862) XVII-V

- The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Michael Maas p.286

- Notes on the Evolution of Alchon Coins, Pankaj Tandon, http://coinindia.com/Alchon.pdf

- Bailey, H. W. Iranian Studies, Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. BSOAS, vol. 6, No. 4 (1932)

- "BAHMAN YAŠT" in Encyclopædia Iranica by W. Sundermann

- (Bailey, 1954, pp.12-16; 1932, p. 945),

Sources

- Cribb, Joe (2010). Alram, M. (ed.). "The Kidarites, the numismatic evidence.pdf". Coins, Art and Chronology II: 91–146.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Daryaee, Touraj; Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). "The Sasanian Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE – 651 CE). UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. pp. 1–236. ISBN 978-0-692-86440-1.

- Payne, Richard (2016). "The Making of Turan: The Fall and Transformation of the Iranian East in Late Antiquity". Journal of Late Antiquity. 9. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press: 4–41. doi:10.1353/jla.2016.0011. S2CID 156673274.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). "East Iran in Late Antiquity". ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 978-1-4744-0030-5. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1g04zr8.

External links

| Huns | |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Rulers | |

| Military leaders | |

| Noblemen | |

| Diplomats | |

| Other notable Huns | |

| Culture | |

| Wars | |

| Other Hunnic peoples | |

| Related topics | |