| Revision as of 12:22, 7 December 2016 editNick Cooper (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users19,261 editsm Uncited.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 13:08, 28 December 2024 edit undo78.148.123.33 (talk) →Adoption, education: reduce unnecessary words | ||

| (328 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|British convicted murderer}} | |||

| ⚫ | {{Infobox |

||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2023}} | |||

| ⚫ | | name |

||

| {{EngvarB|date=February 2020}} | |||

| ⚫ | | image |

||

| {{Distinguish|Jamie Bamber}} | |||

| ⚫ | | image_size |

||

| ⚫ | | alt |

||

| ⚫ | | caption |

||

| ⚫ | | birth_date |

||

| ⚫ | | |

||

| ⚫ | | |

||

| | education = ], ], England | |||

| | known for = ] | |||

| ⚫ | | criminal_charge |

||

| ⚫ | | criminal_penalty |

||

| ⚫ | {{Infobox criminal | ||

| ⚫ | | name = Jeremy Bamber | ||

| ⚫ | | image = Jeremy Bamber.jpg | ||

| ⚫ | | image_size = | ||

| ⚫ | | alt = | ||

| ⚫ | | caption = Bamber in 1985 | ||

| | birth_name = Jeremy Paul Marsham | |||

| ⚫ | | birth_date = {{Birth date and age|df=y|1961|1|13}} | ||

| | birth_place = ], ], ] | |||

| ⚫ | | known for = | ||

| ⚫ | | criminal_charge = | ||

| ⚫ | | criminal_penalty = ] (convicted 28 October 1986) | ||

| | conviction = ] (5 counts) | |||

| | conviction_status = ] | |||

| | fatalities = 5 | |||

| ⚫ | | date = 7 August 1985 | ||

| | apprehended = 29 September 1985 | |||

| | weapon = ] | |||

| | locations = ] | |||

| | country = ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Jeremy Nevill Bamber''' (born 13 January 1961) was convicted in |

'''Jeremy Nevill Bamber''' (born '''Jeremy Paul Marsham'''; 13 January 1961) is a British convicted mass murderer. He was convicted of the 1985 ] in ], ], in which the victims included Bamber's adoptive parents, Nevill and June Bamber; his adoptive sister, Sheila Caffell; and his sister's six-year-old twin sons.<ref>Carol Ann Lee, ''The Murders at White House Farm'', Sidgwick & Jackson, 2015.</ref><ref>{{cite book |first=Claire |last=Powell |title=Murder at White House Farm |publisher=Headline Book Publishing |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZN1rHAAACAAJ |year=1994|isbn= 978-0747243663}}</ref> The prosecution had argued that after committing the murders to secure a large inheritance, Bamber had placed the rifle in the hands of his 28-year-old sister, who had been diagnosed with ], to make the scene appear to be a ]. The jury returned a majority guilty verdict.<ref>Lee 2015, 342–344.</ref> | ||

| Bamber is serving ] with a ], meaning that he has no possibility of parole.<ref name=Smith>David James Smith, , ''The Sunday Times Magazine'', 11 July 2010 ().</ref><ref>Martin Evans, , ''The Daily Telegraph'', 25 November 2016.</ref> He has repeatedly applied unsuccessfully to have his conviction ] or his whole life tariff removed; his extended family remains convinced of his guilt.<ref name=Smith/> The ] (CCRC) referred the case to the ] in 2001, which upheld the conviction in 2002. The appeal was rejected and the CCRC rejected further applications from Bamber in 2004 and 2012, with the commission stating in 2012 that it had not identified any new evidence or legal argument capable of raising a real possibility that his conviction would be quashed.<ref name=Allison26April>Eric Allison, , ''The Guardian'', 26 April 2012.</ref> On 10 March 2021, a new application was lodged with the CCRC for a referral to the Court of Appeal. As of 2023, he has spent 37 years in prison, making him one of the longest-serving prisoners in the UK. | |||

| Bamber was 25 years old when he was convicted. The prosecution argued successfully that, after carrying out the murders to secure a large inheritance, Bamber had placed the gun in his 28-year-old sister's hands to make it look like a murder–suicide. She had been diagnosed with ], and for several weeks after the murders the police and media believed she was the killer.<ref name=TimesMarch182001>''Times'' editorial. , 18 March 2001.</ref> | |||

| Arguing that he is the victim of a miscarriage of justice, Bamber has several times applied to have the conviction overturned or his sentence reduced. The ] upheld the conviction in 1989. The ] (CCRC) referred the case back to the Court of Appeal in 2001, which upheld the conviction again in 2002. The CCRC rejected further applications from Bamber's lawyers in 2004 and 2012.<ref name=Allison26April>Eric Allison, , ''The Guardian'', 26 April 2012.</ref> In July 2013 the ] ruled in Bamber's favour that there must be a possibility, for whole-life prisoners, of release and review.<ref name=BBCNews9July2013/> | |||

| Bamber told ''The Guardian'' in 2011 that he has never contemplated the thought that he will not be released.<ref>Eric Allison, et al, , Guardian Films, 30 January 2011.</ref> He does not have the support of his extended family, who were involved in gathering the evidence that saw him convicted and who remain convinced of his guilt.<ref name=Smith/> | |||

| ==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

| ===Adoption, education=== | ===Adoption, education=== | ||

| Jeremy Bamber was born Jeremy Paul Marsham in 1961 at ], ], ],<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zV3WCwAAQBAJ&q=%22+Jeremy+Paul+Marsham%22&pg=PA25|title=The Murders at White House Farm|first=Carol Ann|last=Lee|date=7 April 2016|publisher=Pan Macmillan|access-date=4 February 2018|via=Google Books|isbn=9781447285755}}</ref> to Juliet Dorothy Wheeler (born 1938 in ]),<ref>{{cite web|url=https://search.findmypast.co.uk/results/world-records/england-and-wales-births-1837-2006?firstname=juliet+d&lastname=wheeler&eventyear=1938&eventyear_offset=0|title=findmypast.co.uk|website=search.findmypast.co.uk|access-date=4 February 2018}}</ref> a ]'s daughter who had had an affair with ] ] Leslie Brian Marsham (born 1931 in ], ]),<ref>{{cite web|url=https://search.findmypast.co.uk/results/world-records/england-and-wales-births-1837-2006?firstname=leslie+b&lastname=marsham|title=findmypast.co.uk|website=search.findmypast.co.uk|access-date=4 February 2018}}</ref> a controller at ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://search.findmypast.co.uk/results/world-records/england-and-wales-births-1837-2006?firstname=jeremy&lastname=marsham|title=findmypast.co.uk|website=search.findmypast.co.uk|access-date=4 February 2018}}</ref> Wheeler gave her baby up for adoption through the ] ]. Nevill and June Bamber adopted Bamber when he was six months old. It was only after his conviction that his biological parents were told by reporters that Bamber was their son. They were by then married to each other and working at Buckingham Palace.<ref>Lee 2015, 25, 55–60.</ref> | |||

| Bamber was born to a vicar's daughter who had had an affair with an army sergeant, a controller at ]. She gave the baby up for adoption in 1961, the year of his birth, through the Church of England Children's Society. It was only after Bamber's conviction, when his adoption records were published, that his biological parents were told by reporters that Bamber was their son. They were by then married to each other and working at Buckingham Palace.<ref>Claire Powell, ''Murder at White House Farm'', Headline Book Publishing, 1994, p. 265.{{paragraph break}} | |||

| Also see Carol Ann Lee, ''The Murders at White House Farm'', Sidgwick & Jackson, 2015.</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | The Bambers were wealthy farmers who lived in a large ] house at White House Farm, near ] in Essex. Nevill was a local ] and former ] pilot. The couple had adopted a baby girl, Sheila, four years prior to adopting Jeremy.<ref name=Lomax67>Scott Lomax, ''Jeremy Bamber: Evil, Almost Beyond Belief?'', The History Press, 2008, 67–68.</ref> | ||

| ] in Norfolk.]] | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| Bamber attended Maldon Court, a private school |

Bamber attended St Nicholas Primary, followed by Maldon Court, a private ]. In September 1970 he was sent to ], a boarding school in ], ].<ref>Lee 2015, 27, 31.</ref> Bamber left Gresham's with no qualifications, much to Nevill's anger, but managed to pass seven ] at The ] College in ] in 1978.<ref>Powell 1994, 40.</ref> Brett Collins claims Bamber had sexual relationships ], finding that his good looks and charm made him popular with both.<ref>Powell 1994, 38, 46.</ref> | ||

| A close friend of his, Brett Collins, said Bamber was sexually assaulted when he was 11, around the time he started at Gresham's. According to Collins, Bamber went on to have sexual relationships with men and women, finding that his good looks and charm made him popular with both.<ref>Powell 1994, pp. 38, 46.</ref> He left school with no qualifications, much to Nevill's anger, but managed to pass seven O-levels at sixth-form college in Colchester, which he left in 1978.<ref>Powell 1994, p. 40.</ref> | |||

| ===Work=== | ===Work=== | ||

| After school |

After leaving school Nevill financed a trip for Bamber to Australia, where he took a scuba diving course, and to New Zealand. In New Zealand, according to Collins, Bamber was "ripped off" by a would-be ] dealer in ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/crime/119648317/so-my-best-friend-turned-out-to-be-a-mass-murderer |title= So my best friend turned out to be a mass murderer |publisher= Stuff/Fairfax |date=1 March 2020}}</ref> Bamber reportedly boasted of smuggling heroin overseas and broke into a jewellery shop to steal two expensive watches, one of which he gave to a girlfriend in the UK. One of Bamber's cousins claimed that he left New Zealand in a hurry after friends of his had been involved in an ].<ref name=Powell47>Powell 1994, 47–48.</ref> | ||

| Bamber returned to the UK and worked in restaurants and bars, including a period as a waiter in a ] on the ]; but he later agreed to return home and work on his father's farm.<ref name=Powell47/> Although Bamber reportedly resented the low wages, he was given a car and lived rent-free in a cottage his father owned at 9 Head Street, ], {{convert|3.5|mi}} from his family's farmhouse at White House Farm. He also owned eight per cent of his family's ], Osea Road Camp Sites Ltd., in ].<ref name=Lomax68>Lomax 2008, 68–69.{{pb}} For the cottage in Goldhanger, , Royal Courts of Justice, 12 December 2002, para 18.</ref> A few weeks before the murders, Bamber broke into and stole from the caravan park; this was only revealed following the murders, when he admitted to the burglary after his girlfriend ] came forward as a witness against him.<ref>'' Blood Relations: Jeremy Bamber and the White House Farm Murders'' {{ISBN|978-0-140-24200-3}} pp. 159-161</ref> | |||

| ] writes that two very different views have emerged of Bamber's personality. Prosecution witnesses described him as arrogant, with no respect for his family, and in search of a lifestyle he could not afford. Against this, his friends described him as gentle, someone who had never expressed violent thoughts. Lomax writes that Bamber underwent several psychological assessments in prison, but no evidence of ] was found.<ref>Lomax 2008, pp. 70–72.</ref> His lawyers arranged for him to undergo a ] test in 2007, which he passed.<ref>Eric Allison, Simon Hattenstone, ''The Guardian'', 10 February 2011.</ref> | |||

| ==White House Farm murders== | ==White House Farm murders== | ||

| {{main|White House Farm murders}} | {{main|White House Farm murders}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Bamber claims he alerted police to the shootings at around 3:30 am on 7 August 1985. He contends that he told them Nevill had telephoned him to say that Bamber's sister, Sheila Caffell, had gone "berserk" with Nevill's rifle. When police entered the farmhouse at White House Farm, Caffell was found dead on the floor of her parents' bedroom with the rifle up against her throat. June was found in the same room. Caffell's six-year-old twin sons, Nicholas and Daniel, were found in their beds in another upstairs room, while Nevill was found in the kitchen downstairs. The family had been shot a total of twenty-five times, mostly at close range.<ref name=Smith/> | |||

| Sheila had |

Sheila had spent time in a ] undergoing treatment for ] months before the murders. The police believed that she was responsible until Mugford told them Jeremy had implicated himself.<ref name=Smith/> The ] argued that there was no evidence that Bamber's father had telephoned him, stating that Nevill was too badly injured to have spoken to anyone; that there was no blood on the kitchen phone; and that he would have called the police, not Bamber. They also argued that the ] was on the rifle when the shots were fired and that Caffell's reach was not long enough to hold the gun and silencer at her throat and press the trigger. In addition, Sheila was not strong enough, they said, to have overcome Nevill in what appeared to have been a violent struggle in the kitchen. They also argued whether that she had shot herself twice in her apparent suicide attempt, that it was evidence that she was not the killer.<ref>, 12 December 2002.</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | Bamber's ] team have unsuccessfully challenged the evidence over the years. They alleged that a police log suggested that Bamber's father had indeed called the police that night and that the silencer may not have been on the gun during the attacks.<ref name=Allison4Feb2012>Eric Allison, Mark Townsend, , ''The Observer'', 4 February 2012.</ref> The evidence about the silencer was unreliable, they argued, because the silencer was found in a farmhouse cupboard by one of Bamber's cousins three days after the murders.<ref name=Smith/> | ||

| The prosecution case hinged on several key points. First, they argued that there was no evidence that Bamber's father had telephoned him, and that if Bamber was lying about the phone call, he must be the killer himself. They argued that the father was too badly injured after the first shots to have spoken to anyone; that there was no blood on the kitchen phone; and that he would have called the police, not Bamber. Second, they argued that, based on a spot of blood found inside the silencer, the silencer was on the gun when the shots were fired. If the silencer was on the gun, Sheila could not have shot herself twice in the throat, removed the silencer, and then had the strength to place it in a cupboard on a different floor of the house, before lying down to die. They also argued she could not have shot herself with the silencer on the rifle, because her reach was not long enough to hold the gun and silencer at her throat and press the trigger. The fact that she suffered two gunshot wounds to her own throat, the first of which was non-lethal, was said to be very unusual if not unheard of, for a suicide. In addition, the prosecution contended that Sheila was not strong enough to have overcome her father, who was over six feet tall, in what appeared to have been a violent struggle.<ref>, 12 December 2002.</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | Bamber's defence team challenged the evidence over the years. They alleged that a police log suggested Bamber's father |

||

| ==Life in prison== | ==Life in prison== | ||

| Bamber is |

Jeremy Bamber is currently confined at ]. Whilst there, he has worked as a peer partner, which involves helping other prisoners to read and write, and won several awards for transcribing books in the prison's ] workshop.<ref>Lomax 2008, pp. 72–73.</ref> In 2001, '']'' alleged that he had been treated with indulgence at ], ], where prisoners were given the key to their cells. Among the allegations were claims that he studied for his ] in Sociology and Media Studies, had a daily ] lesson, and drew pictures of supermodels in an art class, which he later sold through an outside agent.<ref name=TimesMarch182001>, ''The Times'', editorial, 18 March 2001.</ref> | ||

| He |

He has a group of outside supporters, and he has reportedly developed several close relationships with women since his conviction. He defended himself on one occasion from a knife attack by another prisoner by using a broken bottle, and on another received twenty-eight stitches on his neck after being attacked while making a telephone call.<ref>Martin Wainwright, , ''The Guardian'', 1 June 2004.</ref> In 1994, Bamber called a radio station from Long Lartin prison to declare his innocence.<ref name=TimesMarch182001/> | ||

| == |

==Legal actions== | ||

| ⚫ | Bamber launched two unsuccessful legal actions while in prison to recover a share of his family's estate.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2003/aug/19/ukcrime.johnezard|title=Murder family sued by killer|date=19 August 2003|newspaper=]|last1=Ezard|first1=John}}</ref> His grandmother had cut Bamber out of her will when he was arrested, and most of the inheritance went to June's sister.<ref name=BBCAug182003>, BBC News, 18 August 2003; John Ezard, , ''The Guardian'', 19 August 2003.</ref><ref>"On This Day," ''The Times'', 29 October 1986.</ref> In 2004, Bamber went to the ] again to claim a share of the profits from the Bambers' caravan site in Maldon. He had retained his shares after his conviction, but had sold them to pay the legal costs arising from his claim on his grandmother's estate. The court ruled that he was not entitled to any profit from the site because of his conviction.<ref>, BBC News, 6 October 2004.</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | In January 2012, Bamber and two other British prisoners, ] and Douglas Vinter, lost a case before the ], in which they argued that ] amounts to degrading and inhuman treatment. In July 2012, they were granted the right to appeal that decision.<ref>Tom Whitehead, , ''The Daily Telegraph'', 17 January 2012.{{paragraph break}} | ||

| ===Against extended family=== | |||

| ⚫ | Caroline Davies, , ''The Guardian'', 19 July 2012.</ref> In July 2013, the Court's Grand Chamber ruled in their favour, holding that there must be sentence review with the potential of possible release.<ref name=BBCNews9July2013>, BBC News, 9 July 2013.</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | Bamber launched two unsuccessful |

||

| On 10 March 2021, a new application was lodged with the ] for a referral to the Court of Appeal. The submissions contained new evidence not previously considered by the Courts and based on 350,000 documents released to Bamber and his legal team in 2011 after the expiry of a Public Interest Immunity order. Initially, eight issues, each containing multiple grounds of appeal, were lodged, with another two added before the end of the year.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/mar/12/jeremy-bamber-lawyers-hopeful-for-release-as-fresh-legal-challenge-launched |title=Jeremy Bamber lawyers hopeful for release as fresh legal challenge launched |date=12 March 2021|newspaper=] |last1=Weaver |first1=Matthew |last2=Hattenstone |first2=Simon |access-date=28 March 2022}}</ref> In October 2022 it was reported that Bamber's legal team, led by his Solicitor Advocate, had sent the CCRC ten new items of evidence, which they claimed cast doubt on the prosecution's contention that the silencer was used in the murders.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.news.sky.com/story/amp/white-house-farm-murderer-jeremy-bamber-seeks-to-overturn-conviction-with-new-evidence-lawyers-say-12721921|title=White House Farm murderer Jeremy Bamber seeks to overturn conviction with new evidence, lawyers say|newspaper=Sky News|date=16 October 2022|access-date=17 October 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ===European Court of Human Rights=== | |||

| In May 2023 the Independent Office for Police Conduct ruled that Essex Police breached its statutory duty by not referring 29 serious complaints to the IOPC about how senior officers handled the case.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://metro.co.uk/2023/05/14/jailed-jeremy-bamber-says-police-watchdog-ruling-could-see-him-freed-18781788/amp/ | title=Jailed Jeremy Bamber says police watchdog ruling could see him freed }}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | In January 2012 Bamber and two other British prisoners |

||

| ⚫ | Caroline Davies, , ''The Guardian'', 19 July 2012.</ref> In July 2013 the Court's Grand Chamber ruled in their favour, holding that there must be |

||

| It was reported in November 2024 that Bamber's conviction was among 1,200 being reviewed by the CCRC in the aftermath of the ].<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2024/11/26/white-house-farm-killer-jeremy-bamber-case-may-be-reviewed/ |title=White House Farm killer Jeremy Bamber’s case ‘among 1,200 to be reviewed’ |newspaper=The Telegraph |date=26 November 2024 |first1=Danny |last1=Shaw |first2=Andrew |last2=Hymas}}</ref> | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| ⚫ | {{reflist |

||

| ==See also== | |||

| ==Cited works and further reading== | |||

| *] | |||

| * Lee, Carol Ann. (2015). ''The Murders at White House Farm: Jeremy Bamber and the killing of his family. The Definitive Investigation''. Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 978-0-283-07222-2 | |||

| *] | |||

| * Lomax, Scott (2008). ''Jeremy Bamber: Evil, Almost Beyond Belief?''. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-752-49630-6 | |||

| * Wilkes, Roger (1994). ''Blood Relations: Jeremy Bamber and the White House Farm Murders''. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-024200-7 | |||

| == |

==References== | ||

| ⚫ | {{reflist}} | ||

| * , a selection of articles from ''The Guardian'' | |||

| * The Jeremy Bamber Campaign "Why Jeremy is Innocent" e-book | |||

| * In 2015 American broadcasters 'The Generation Why Podcast' independently featured the White House Farm Murders in a debate: http://thegenerationwhypodcast.com/podcast/white-house-farm-murders-141-generation-why | |||

| * Crimes That Shook Britain featured the White House Farm Murders in 2011 starring Johnny Escobar | |||

| {{Authority control}} | {{Authority control}} | ||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Bamber, Jeremy}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Bamber, Jeremy}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 13:08, 28 December 2024

British convicted murdererNot to be confused with Jamie Bamber.

| Jeremy Bamber | |

|---|---|

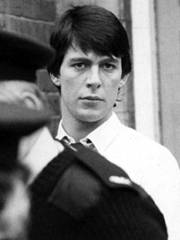

Bamber in 1985 Bamber in 1985 | |

| Born | Jeremy Paul Marsham (1961-01-13) 13 January 1961 (age 63) Kensington, London, England |

| Criminal status | Incarcerated |

| Conviction(s) | Murder (5 counts) |

| Criminal penalty | Whole life order (convicted 28 October 1986) |

| Details | |

| Date | 7 August 1985 |

| Country | England |

| Location(s) | Tolleshunt D'Arcy |

| Killed | 5 |

| Weapon | Rifle |

| Date apprehended | 29 September 1985 |

Jeremy Nevill Bamber (born Jeremy Paul Marsham; 13 January 1961) is a British convicted mass murderer. He was convicted of the 1985 White House Farm murders in Tolleshunt D'Arcy, Essex, in which the victims included Bamber's adoptive parents, Nevill and June Bamber; his adoptive sister, Sheila Caffell; and his sister's six-year-old twin sons. The prosecution had argued that after committing the murders to secure a large inheritance, Bamber had placed the rifle in the hands of his 28-year-old sister, who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, to make the scene appear to be a murder–suicide. The jury returned a majority guilty verdict.

Bamber is serving life imprisonment with a whole life tariff, meaning that he has no possibility of parole. He has repeatedly applied unsuccessfully to have his conviction overturned or his whole life tariff removed; his extended family remains convinced of his guilt. The Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) referred the case to the Court of Appeal in 2001, which upheld the conviction in 2002. The appeal was rejected and the CCRC rejected further applications from Bamber in 2004 and 2012, with the commission stating in 2012 that it had not identified any new evidence or legal argument capable of raising a real possibility that his conviction would be quashed. On 10 March 2021, a new application was lodged with the CCRC for a referral to the Court of Appeal. As of 2023, he has spent 37 years in prison, making him one of the longest-serving prisoners in the UK.

Early life

Adoption, education

Jeremy Bamber was born Jeremy Paul Marsham in 1961 at St Mary Abbots Hospital, Kensington, London, to Juliet Dorothy Wheeler (born 1938 in Leicester), a vicar's daughter who had had an affair with British Army Sergeant Major Leslie Brian Marsham (born 1931 in Tendring, Essex), a controller at Buckingham Palace. Wheeler gave her baby up for adoption through the Church of England Children's Society. Nevill and June Bamber adopted Bamber when he was six months old. It was only after his conviction that his biological parents were told by reporters that Bamber was their son. They were by then married to each other and working at Buckingham Palace.

The Bambers were wealthy farmers who lived in a large Georgian house at White House Farm, near Tolleshunt D'Arcy in Essex. Nevill was a local magistrate and former RAF pilot. The couple had adopted a baby girl, Sheila, four years prior to adopting Jeremy.

Bamber attended St Nicholas Primary, followed by Maldon Court, a private prep school. In September 1970 he was sent to Gresham's School, a boarding school in Holt, Norfolk. Bamber left Gresham's with no qualifications, much to Nevill's anger, but managed to pass seven O-levels at The Sixth Form College in Colchester in 1978. Brett Collins claims Bamber had sexual relationships with men and women, finding that his good looks and charm made him popular with both.

Work

After leaving school Nevill financed a trip for Bamber to Australia, where he took a scuba diving course, and to New Zealand. In New Zealand, according to Collins, Bamber was "ripped off" by a would-be heroin dealer in Auckland. Bamber reportedly boasted of smuggling heroin overseas and broke into a jewellery shop to steal two expensive watches, one of which he gave to a girlfriend in the UK. One of Bamber's cousins claimed that he left New Zealand in a hurry after friends of his had been involved in an armed robbery.

Bamber returned to the UK and worked in restaurants and bars, including a period as a waiter in a Little Chef on the A12; but he later agreed to return home and work on his father's farm. Although Bamber reportedly resented the low wages, he was given a car and lived rent-free in a cottage his father owned at 9 Head Street, Goldhanger, 3.5 miles (5.6 km) from his family's farmhouse at White House Farm. He also owned eight per cent of his family's caravan site, Osea Road Camp Sites Ltd., in Maldon. A few weeks before the murders, Bamber broke into and stole from the caravan park; this was only revealed following the murders, when he admitted to the burglary after his girlfriend Julie Mugford came forward as a witness against him.

White House Farm murders

Main article: White House Farm murders

Bamber claims he alerted police to the shootings at around 3:30 am on 7 August 1985. He contends that he told them Nevill had telephoned him to say that Bamber's sister, Sheila Caffell, had gone "berserk" with Nevill's rifle. When police entered the farmhouse at White House Farm, Caffell was found dead on the floor of her parents' bedroom with the rifle up against her throat. June was found in the same room. Caffell's six-year-old twin sons, Nicholas and Daniel, were found in their beds in another upstairs room, while Nevill was found in the kitchen downstairs. The family had been shot a total of twenty-five times, mostly at close range.

Sheila had spent time in a psychiatric hospital undergoing treatment for schizophrenia months before the murders. The police believed that she was responsible until Mugford told them Jeremy had implicated himself. The prosecution argued that there was no evidence that Bamber's father had telephoned him, stating that Nevill was too badly injured to have spoken to anyone; that there was no blood on the kitchen phone; and that he would have called the police, not Bamber. They also argued that the silencer was on the rifle when the shots were fired and that Caffell's reach was not long enough to hold the gun and silencer at her throat and press the trigger. In addition, Sheila was not strong enough, they said, to have overcome Nevill in what appeared to have been a violent struggle in the kitchen. They also argued whether that she had shot herself twice in her apparent suicide attempt, that it was evidence that she was not the killer.

Bamber's defence team have unsuccessfully challenged the evidence over the years. They alleged that a police log suggested that Bamber's father had indeed called the police that night and that the silencer may not have been on the gun during the attacks. The evidence about the silencer was unreliable, they argued, because the silencer was found in a farmhouse cupboard by one of Bamber's cousins three days after the murders.

Life in prison

Jeremy Bamber is currently confined at HM Prison Wakefield. Whilst there, he has worked as a peer partner, which involves helping other prisoners to read and write, and won several awards for transcribing books in the prison's braille workshop. In 2001, The Times alleged that he had been treated with indulgence at HM Prison Long Lartin, Worcestershire, where prisoners were given the key to their cells. Among the allegations were claims that he studied for his GCSE in Sociology and Media Studies, had a daily badminton lesson, and drew pictures of supermodels in an art class, which he later sold through an outside agent.

He has a group of outside supporters, and he has reportedly developed several close relationships with women since his conviction. He defended himself on one occasion from a knife attack by another prisoner by using a broken bottle, and on another received twenty-eight stitches on his neck after being attacked while making a telephone call. In 1994, Bamber called a radio station from Long Lartin prison to declare his innocence.

Legal actions

Bamber launched two unsuccessful legal actions while in prison to recover a share of his family's estate. His grandmother had cut Bamber out of her will when he was arrested, and most of the inheritance went to June's sister. In 2004, Bamber went to the High Court again to claim a share of the profits from the Bambers' caravan site in Maldon. He had retained his shares after his conviction, but had sold them to pay the legal costs arising from his claim on his grandmother's estate. The court ruled that he was not entitled to any profit from the site because of his conviction.

In January 2012, Bamber and two other British prisoners, Peter Moore and Douglas Vinter, lost a case before the European Court of Human Rights, in which they argued that whole-life imprisonment amounts to degrading and inhuman treatment. In July 2012, they were granted the right to appeal that decision. In July 2013, the Court's Grand Chamber ruled in their favour, holding that there must be sentence review with the potential of possible release.

On 10 March 2021, a new application was lodged with the CCRC for a referral to the Court of Appeal. The submissions contained new evidence not previously considered by the Courts and based on 350,000 documents released to Bamber and his legal team in 2011 after the expiry of a Public Interest Immunity order. Initially, eight issues, each containing multiple grounds of appeal, were lodged, with another two added before the end of the year. In October 2022 it was reported that Bamber's legal team, led by his Solicitor Advocate, had sent the CCRC ten new items of evidence, which they claimed cast doubt on the prosecution's contention that the silencer was used in the murders. In May 2023 the Independent Office for Police Conduct ruled that Essex Police breached its statutory duty by not referring 29 serious complaints to the IOPC about how senior officers handled the case.

It was reported in November 2024 that Bamber's conviction was among 1,200 being reviewed by the CCRC in the aftermath of the Andrew Malkinson scandal.

See also

References

- Carol Ann Lee, The Murders at White House Farm, Sidgwick & Jackson, 2015.

- Powell, Claire (1994). Murder at White House Farm. Headline Book Publishing. ISBN 978-0747243663.

- Lee 2015, 342–344.

- ^ David James Smith, "And by dawn, they were all dead", The Sunday Times Magazine, 11 July 2010 (webcite).

- Martin Evans, "The 70 prisoners serving whole life sentences in the UK", The Daily Telegraph, 25 November 2016.

- Eric Allison, "Jeremy Bamber murder appeal bid thrown out, The Guardian, 26 April 2012.

- Lee, Carol Ann (7 April 2016). The Murders at White House Farm. Pan Macmillan. ISBN 9781447285755. Retrieved 4 February 2018 – via Google Books.

- "findmypast.co.uk". search.findmypast.co.uk. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- "findmypast.co.uk". search.findmypast.co.uk. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- "findmypast.co.uk". search.findmypast.co.uk. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Lee 2015, 25, 55–60.

- Scott Lomax, Jeremy Bamber: Evil, Almost Beyond Belief?, The History Press, 2008, 67–68.

- Lee 2015, 27, 31.

- Powell 1994, 40.

- Powell 1994, 38, 46.

- "So my best friend turned out to be a mass murderer". Stuff/Fairfax. 1 March 2020.

- ^ Powell 1994, 47–48.

- Lomax 2008, 68–69. For the cottage in Goldhanger, "R v Jeremy Bamber", Royal Courts of Justice, 12 December 2002, para 18.

- Blood Relations: Jeremy Bamber and the White House Farm Murders ISBN 978-0-140-24200-3 pp. 159-161

- "R v Jeremy Bamber", 12 December 2002.

- Eric Allison, Mark Townsend, "Gun experts raise doubts over Jeremy Bamber murder verdict", The Observer, 4 February 2012.

- Lomax 2008, pp. 72–73.

- ^ "Murder most foul, but did he do it?", The Times, editorial, 18 March 2001.

- Martin Wainwright, "Murderer Bamber suffers knife attack in prison", The Guardian, 1 June 2004.

- Ezard, John (19 August 2003). "Murder family sued by killer". The Guardian.

- "Bamber claims £1m from family", BBC News, 18 August 2003; John Ezard, "Murder family sued by killer", The Guardian, 19 August 2003.

- "On This Day," The Times, 29 October 1986.

- "Killer's family cash claim fails", BBC News, 6 October 2004.

- Tom Whitehead, "Notorious killers can die behind bars, rules Europe", The Daily Telegraph, 17 January 2012.

Caroline Davies, "Jeremy Bamber wins right to European appeal over whole-life sentence", The Guardian, 19 July 2012.

- "Killers' life terms 'breach their human rights'", BBC News, 9 July 2013.

- Weaver, Matthew; Hattenstone, Simon (12 March 2021). "Jeremy Bamber lawyers hopeful for release as fresh legal challenge launched". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "White House Farm murderer Jeremy Bamber seeks to overturn conviction with new evidence, lawyers say". Sky News. 16 October 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- "Jailed Jeremy Bamber says police watchdog ruling could see him freed".

- Shaw, Danny; Hymas, Andrew (26 November 2024). "White House Farm killer Jeremy Bamber's case 'among 1,200 to be reviewed'". The Telegraph.

- 1961 births

- 20th-century English criminals

- Criminals from Essex

- English adoptees

- English mass murderers

- English murderers of children

- English people convicted of murder

- English prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- Living people

- People convicted of murder by England and Wales

- People educated at Gresham's School

- People from Maldon District

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by England and Wales