| Revision as of 01:54, 15 October 2006 editNikoSilver (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users13,519 editsm →Rise of Greek influence in the Ottoman Empire: yes, and you just broke it / +fmt (minor space before ref)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:14, 30 November 2024 edit undoDemetrios1993 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers9,103 edits Reverted 2 edits by 89.136.175.103 (talk): The interest in the community is not recent; a number of authors have written about it. This addition focuses on the work of a single author, and appears more as advertising; it lacks independent, third-party sources. Also, MOS:APOSTROPHE and MOS:ITALICS.Tags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| (607 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Greek nobility from Phanar, Constantinople}} | |||

| ]: ] riding through ] in a ]-drawn carriage (late 1780s)]] | |||

| ] quarter, the historical centre of the ] of ] in ], ca. 1900]] | |||

| '''Phanariotes''', '''Phanariots''', or '''Phanariote Greeks''' (]: ''Φαναριώτες'', ]: ''Fanarioţi'') were members of those prominent and predominantly ] families residing in ] (in ], from the Greek nautical word ''Φανάρι'', ''Fanari'', meaning "]"),<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.komvos.edu.gr/dictonlineplsql/simple_search.display_full_lemma?the_lemma_id=15948&target_dict=1 | title=''Τριανταφυλλίδης On line Dictionary'' | work=Φανάρι (ναυτ.) |accessmonthday= October, 7 | accessyear=2006}}</ref> the chief Greek quarter of Constantinople (]), where the ] is situated. Phanariotes dominated the administration of the Patriarchate and frequently intervened in the selection of ]s, including the ], who has the status of "]" among the world's ] ]s. | |||

| ]; atop the hill: the ].]] | |||

| '''Phanariots''', '''Phanariotes''', or '''Fanariots''' ({{langx|el|Φαναριώτες}}, {{langx|ro|Fanarioți}}, {{langx|tr|Fenerliler}}) were members of prominent ] families in ]<ref name="BritB">{{EB1911|wstitle=Phanariotes | volume= 21 | page = 346}}</ref> (Φανάρι, modern ''Fener''),<ref>The names ] and Φανάρι (''Fanari'') derive from the Greek nautical word meaning "]" (literary "lantern" or "lamp")<br />{{cite web|url=http://www.komvos.edu.gr/dictonlineplsql/simple_search.display_full_lemma?the_lemma_id=15948&target_dict=1 | title=''Τριανταφυλλίδης On line Dictionary'' | work=Φανάρι (ναυτ.) |access-date= October 7, 2006 }}</ref> the chief Greek quarter of ] where the ] is located, who traditionally occupied four important positions in the ]: ], ], Grand ] and Grand ]. Despite their cosmopolitanism and often-Western education, the Phanariots were aware of their Greek ancestry and culture; according to ]' ''Philotheou Parerga'', "We are a race completely Hellenic".<ref>Mavrocordatos Nicholaos, ''Philotheou Parerga'', J.Bouchard, 1989, p.178, citation: Γένος μεν ημίν των άγαν Ελλήνων</ref> | |||

| Some members of these families, which had acquired great wealth and influence during the 17th century, occupied high ] in the ]. From 1669 until 1821 Phanariotes served as ]s to the Ottoman government (the ]) and to foreign ]. Along with the church dignitaries and the local notables from the provinces, Phanariotes represented the ruling class of the Greek nation during Ottoman rule and until the start of the ]. During the latter, Phanariotes played a crucial role and influenced the decisions of the ], the representative body of the Greek revolutionaries, which met on six occasions between ] and ]. | |||

| They emerged as a class of wealthy Greek merchants (of mostly noble ] descent) during the second half of the 16th century, and were influential in the administration of the Ottoman Empire's Balkan domains in the 18th century.<ref name="BritB"/> The Phanariots usually built their houses in the Phanar quarter to be near the court of the ], who (under the Ottoman ] system) was recognized as the spiritual and secular head (''millet-bashi'') of the ] subjects—the ], or "Roman nation" of the empire, except those under the spiritual care of the Patriarchs of ], ], ], ] and ]—often acting as ]. They dominated the administration of the patriarchate, often intervening in the selection of ]s (including the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople). | |||

| Between the years ]–] and ], a number of them were appointed ]s (]s or Princes) of the ] (] and ]), usually as a promotion from dragoman offices; that period of Moldo-Wallachian history is also usually termed the '''Phanariote epoch''' in Romanian history. | |||

| ==Overview== | |||

| ==Rise of Greek influence in the Ottoman Empire== | |||

| Many members of Phanariot families (who had acquired great wealth and influence during the 17th century) occupied high ] in the Ottoman Empire. From 1669 until the Greek War of Independence in 1821, Phanariots made up the majority of the ]s to the Ottoman government (the ]) and foreign ] due to the Greeks' higher level of education than the general Ottoman population.<ref name="BritA">Encyclopædia Britannica, The Phanariots, 2008, O.Ed.</ref> With the church dignitaries, local notables from the provinces and the large Greek merchant class, Phanariots represented the better-educated members of Greek society during Ottoman rule until the 1821 start of the ]. During the war, Phanariots influenced decisions by the ] (the representative body of Greek revolutionaries, which met six times between 1821 and 1829).<ref name=BritA/><ref name="Papar108"/> Between 1711–1716 and 1821, a number of Phanariots were appointed ]s (]s or princes) in the ] (] and ]) (usually as a promotion from the offices of ] and ]); the period is known as the Phanariot epoch in Romanian history.<ref name=BritB/> | |||

| After the ] ], when the ] virtually replaced '']'' and '']'' the ] among subjugated Christians, the Ecumenical Patriarch was recognized by the Sultan as the religious and national leader of Greeks. According to the Greek historian Nikos G. Svoronos, the Patriarchate earned a primary importance and occupied this key role among the Christians of the Empire because the Ottomans would not legally distinguish between nationality and religion — and regarded all the Orthodox Christians of the Empire as a single entity (a '']'').<ref name="Svoronos83">Svoronos, p.83</ref> | |||

| ==Ottoman Empire== | |||

| The position of the Patriarchate in the Ottoman state encouraged projects of Greek renaissance, centered on the resurrection and revitalization of the ]. The Patriarch and those church dignitaries aroud him constituted the first centre of power for the Greeks inside the Ottoman state, one which succeeded in infiltrating the structures of the Ottoman Empire, while attracting the former Byzantine nobility.<ref name="Svoronos83">Svoronos, p.83" /> | |||

| {{Update|part=section|date=May 2022|inaccurate=yes|reason=This section makes assumptions that are no longer considered historical consensus, and alludes multiple times to the ], which is now considered a minority opinion}} | |||

| After the ], ] deported the city's Christian population, leaving only the Jewish inhabitants of ],<ref name="ma98">Mamboury (1953), p. 98</ref> repopulating the city with Christians and Muslims from throughout the whole empire and the newly conquered territories.<ref name=ma98/> Phanar was repopulated with Greeks from ] in the ] and, ], with citizens of the ].<ref name="ma99">Mamboury (1953), p. 99</ref> | |||

| The roots of Greek ascendancy can be traced to the Ottoman need for skilled, educated negotiators as their empire declined and they relied on treaties rather than force.<ref name=BritB/> During the 17th century, the Ottomans began having problems in foreign relations and difficulty dictating terms to their neighbours; for the first time, the ] needed to participate in diplomatic negotiations. | |||

| As a result of Phanariote and ecclesiastic administration, Greeks reached the peak of their influence in the 18th century (being at the time the most influential of all subject peoples). This had not always been the case in the Ottoman realm, as in the 16th century it was the ] who were the most prominent in Imperial affairs. Contrary to the Greeks, willingness to convert to ] in order to enjoy full rights of Ottoman citizenship was more present with the Slavs, especially in ], while ] tended to acquire high military positions.<ref name="Stavrianos">Stavrianos, p.270</ref> | |||

| With the Ottomans traditionally ignoring Western European languages and cultures, officials were at a loss.<ref name="Stavrianos" /> The Porte assigned those tasks to the Greeks, who had a long mercantile and educational tradition and the necessary skills. The Phanariots and other Greek as well as Hellenized families primarily from ], occupied high posts as secretaries and interpreters for Ottoman officials.<ref name="Hobsbawm"/> | |||

| In time, a Slavic presence in the administration gradually became a hazard for the Ottoman rulers, as it was prone to offer full support to ] armies in the context of the ]. By the 17th century, the Greek Patriarch of Constantinople became the absolute religious and administrative ruler of all Christian Orthodox subjects within the Empire, regardless of their ethnic background. All formerly independent Orthodox patriarchates, including the ] established in ], were assigned under the authority of the Greek Church.<ref name="Hobsbawm">Hobsbawm pp. 181-185</ref> | |||

| ==={{anchor|Diplomats and Patriarchs}}Diplomats and patriarchs=== | |||

| In addition to this, from the 17th century onwards the Ottomans began meeting problems in the conduct of their foreign relations, and were having difficulties in dictating terms to their neighbours; the Porte was faced for the first time with the need of participating in diplomatic negotiations. Given the Ottoman tradition of generally ignoring ]an languages and cultures, officials found themselves unable to handle such affairs.<ref name="Stavrianos">Stavrianos, p.270</ref> The Porte subsequently assigned those tasks to the Greeks, regarded as the most educated within the Empire. As a result, the so-called ''Phanariotes'', Greek families mostly native to Constantinople, came to occupy high posts of secretaries and interpreters to Ottoman officials and officers.<ref name="Hobsbawm">Hobsbawm pp. 181-185</ref> | |||

| As a result of Phanariot and ecclesiastical administration, the Greeks expanded their influence in the 18th-century empire while retaining their ] faith and Hellenism. This had not always been the case in the Ottoman realm. During the 16th century, the ]—the most prominent in imperial affairs—converted to ] to enjoy the full rights of Ottoman citizenship (especially in the ]; Serbs tended to occupy high military positions.<ref name="Stavrianos">Stavrianos, p. 270</ref> | |||

| A Slavic presence in Ottoman administration gradually became hazardous for its rulers, since the Slavs tended to support ] armies during the ]. By the 17th century the Greek Patriarch of Constantinople was the religious and administrative ruler of the empire's Orthodox subjects, regardless of ethnic background. All formerly-independent Orthodox patriarchates, including the ] renewed in 1557, came under the authority of the Greek Orthodox Church.<ref name="Hobsbawm">Hobsbawm pp. 181–85.</ref> Most of the Greek patriarchs were drawn from the Phanariots. | |||

| Two Greek social groups therefore emerged and challenged the leadership of the Greek Church.<ref name="Svoronos87">Svoronos, p. 87</ref> These powerful social classes were the Phanariotes in Constantinople and the local notables in the ] (''koçabashides''). According to ], one of the major Greek historians, Phanariotes initially sought the most important secular offices of the Patriarchical Court and, thus, they could frequently intervene in the election of bishops, as well as influence crucial decisions of the Patriarch.<ref name="Papar108">Paparregopoulus, Eb, p.108</ref> Greek merchants and clergy of Byzantine aristocratic origin, who acquired great economic and political prosperity, and were later known as ''Phanariotes'', settled in the extreme northwestern district of Constantinople, which had become central to Greek interests after the establishment of the Patriarch's headquarters in ] (shortly after ] fell to Muslim use).<ref name="Svoronos88">Svoronos, p.88</ref> | |||

| Two Greek social groups emerged, challenging the leadership of the Greek Church:<ref name="Svoronos87">Svoronos, p. 87</ref> the Phanariots in ] and the local notables in the ] ('']'', ''dimogerontes'' and ''prokritoi''). According to 19th-century Greek historian ], the Phanariots initially sought the most important secular offices of the patriarchal court and could frequently intervene in the election of bishops and influence crucial decisions by the patriarch.<ref name="Papar108">Paparregopoulus, Eb, p. 108.</ref> Greek merchants and clergy of ] aristocratic origin, who acquired economic and political influence and were later known as Phanariots, settled in extreme northwestern Constantinople (which had become central to Greek interests after the establishment of the patriarch's headquarters in 1461, shortly after ] was converted into a mosque).<ref name="Svoronos88">Svoronos, p. 88.</ref> | |||

| ==Phanariotes as high officials== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| During the 18th century, Phanariotes appeared as a hereditary clerical-aristocratic grouping, managing the affairs of the Patriarchate, and becoming the dominant political power of the Greek community in Ottoman lands.<ref name="Svoronos89">Svoronos, p.89</ref> In time, they grew to become a very significant political factor in the Ottoman Empire, and, as diplomatic agents, played a considerable role in the affairs of the ], ], and the ].<ref name="Svoronos89">Svoronos, p.89<ref/> | |||

| ====Patriarchate==== | |||

| Phanariotes soon competed for some of the most important administrative offices in the Ottoman administration: several of these involved collecting Imperial taxes, holding ] on commerce, working under contract in various enterprises, being purveyors to the court, and even rules over one of the two ] (] and ]).<ref name="Svoronos88">Svoronos, p.88</ref> At the same time, they engaged in private trade dealings, and acquired great control over the crucial wheat trade on the ].<ref name="Svoronos88">Svoronos, p.88</ref> Phanariotes managed to expand their commercial activities first into the ], and then to all other ]an states. Such activities brought intensified their contacts with Western nations, and as a consequence they became familiar with Western languages and cultures.<ref name="Svoronos88" /> | |||

| After the 1453 fall of Constantinople, when the ] replaced '']'' the ] for subjugated Christians, he recognized the Ecumenical Patriarch as the religious and national leader ('']'') of the Greeks and other ethnic groups in the Greek Orthodox '']''.<ref name="glenny">Glenny, p. 195.</ref> The Patriarchate had primary importance, occupying this key role for Christians of the Empire because the Ottomans did not legally distinguish between nationality and religion and considered the empire's ] a single entity.<ref name="Svoronos83">Svoronos, p. 83.</ref> | |||

| The position of the Patriarchate in the Ottoman state encouraged Greek renaissance projects centering on the resurrection and revitalization of the ]. The Patriarch and his church dignitaries constituted the first centre of power for the Greeks in the Ottoman state, which infiltrated Ottoman structures and attracted the former Byzantine nobility.<ref name="Svoronos83" /> | |||

| Just before the outbreak of the ], Phanariotes were established as the upmost political elite of Greekdom. According to Paparregopoulus, this was a natural evolution, given the Phanariotes' education and their experience in supervising vast regions of the Empire.<ref name="Papar108">Paparrigopoulos, Eb, p.108</ref> In parallel, Svoronos argued that they subordinated their ] to their ], since they merely endeavored to achive peaceful co-existence of the conqueror and the conquered; Svoronos believes that, in this way, Phanariotes failed to enrich the Greek national identity, and lost ground to the groups that grew through their confrontation with the Ottoman Empire, first the '']s'' and then the '']''.<ref name="Svoronos91">Svoronos, p.91</ref> | |||

| ===Merchant middle class=== | |||

| ==Phanariote rule of the Danubian Principalities== | |||

| ] (16th century)]] | |||

| ===Establishment and contrasts=== | |||

| The period is not to be understood as marking the introduction into the Principalities of a Greek presence, which had already established itself in both provinces, and had even resulted in the appointment of Greek Princes had been appointed before the ]. After the end of the Phanariote epoch, various families of Phanariote ancestry in both Wallachia and Moldavia identified themselves as ], and remained present in ] - among them, the ], whose member ] represented the ] and ] cause during and after the ], and the ], who, despite direct Phanariote lineage, held the throne in Wallachia with ] and ] as the first "non-Phanariote" rulers after 1821). | |||

| The wealth of the extensive Greek merchant class provided the material basis for the intellectual revival featured in Greek life for more than half a century before 1821. Greek merchants endowed libraries and schools. On the eve of the Greek War of Independence, the three most important centres of Greek learning (schools-cum-universities) were in the commercial centres of ], ] and ].<ref name="autogenerated1">Encyclopædia Britannica, ''Greek history, The mercantile middle class'', 2008 ed.</ref> The first Greek millionaire of the Ottoman era was ], who earned 60,000 ]s a year from his control of the fur trade from ].<ref>]. ''The Great Church in Captivity.'' Cambridge University Press, 1988, page 197.</ref> | |||

| The attention of Phanariotes was concentrated on occupying the most favorable offices the Empire could offer, but also to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which were still relatively rich, and more importantly, autonomous (despite having to pay ] as ]). Many Greeks had found there favorable conditions for commercial activities, by far more advantageous when compared with the difficultes inside the Ottoman Empire, and also an opportunity to gain political power. Many had entered the ranks of Wallachian and Moldavian ] nobility by marriage. | |||

| ===Civil servants=== | |||

| Although rarely occurring, reigns of local Princes were not excluded on principle. This situation had even determined two arguably ] Romanian noble families, the ]s (originally ''Călmaşul'') and ]s, to penetrate into the Phanar nucleus, in order to facilitate and increase their chances to occupy the thrones, and later to successfully maintain their positions. | |||

| During the 18th century, the Phanariots were a hereditary clerical−aristocratic group who managed the affairs of the patriarchate and the dominant political power of the Ottoman Greek community. They became a significant political factor in the empire and, as diplomatic agents, played a role in the affairs of Great Britain, France and the Russian Empire.<ref name="Svoronos89">Svoronos, p. 89.</ref> | |||

| The Phanariots competed for the most important administrative offices in the Ottoman administration; these included collecting imperial taxes, monopolies on commerce, working under contract in a number of enterprises, supplying the court and ruling the ]. They engaged in private trade, controlling the crucial wheat trade on the ]. The Phanariots expanded their commercial activities into the ] and then to the other Central European states. Their activities intensified their contacts with Western nations, and they became familiar with Western languages and cultures.<ref name="Svoronos88" /> | |||

| While most sources would agree to 1711 being the moment where the gradual erosion of the traditional institutions had reached its ultimate stage, characteristics usually ascribed to the Phanariote era had made themselves felt long before it. The Ottoman ] had been enforcing its choice for Hospodars throughout previous centuries (as far back as the ]), and foreign — usually Greek or ]ine — ] had been competing with the local ones since the late ]. Rulers since ] in Moldavia and ], a Prince of Greek origin, in Wallachia (both in ]) had been forced to surrender all of their families, and not just selected members, as ]s in Constantinople. At the same time, the traditional ] in the Principalities had accounted for long periods of political disorder, and was in fact dominated by a small number of ambitious families (whether local or foreign), who had entered violent competition for the two thrones and monopolized land ownership<ref>Djuvara, p.123, 125-126</ref> - a notable example is the conflict opposing the ] and the ] in the period before 1711. | |||

| Before the beginning of the ], the Phanariots were firmly established as the political elite of Hellenism. According to Greek historian Constantine Paparrigopoulos, this was a natural evolution given the Phanariots' education and experience in supervising large parts of the empire.<ref name="Papar108" /> According to Nikos Svoronos argued, the Phanariots subordinated their ] to their ] and tried to peacefully co−exist with the Ottomans; they did not enrich the Greek national identity and lost ground to groups which flourished through their confrontation with the Ottoman Empire (the '']s'' and '']'').<ref name="Svoronos91">Svoronos, p. 91.</ref> | |||

| ===1711-1715=== | |||

| The clear change in policy was determined by the fact that Wallachia and Moldavia, although autonomous, had entered a period of continuous skirmishes with the Ottomans, due to insubordination of the native princes, one especially associated with the rise of ]'s power under ] and the firm presence of the ] on the ] border with the Principalities. Dissidence within the two countries became more dangerous for the Turks, who were now confronted with the attraction exercised on the population by the protection offered to them by a fellow ] Empire. This became obvious with ]'s second rule in Moldavia, when the Prince plotted with Peter to have Ottoman rule removed. Incidentally, his replacement, ], was also the first official Phanariote in his second reign in Moldavia (he was also to replace ] in Wallachia, as the first Phanariote ruler in that country). | |||

| =={{anchor|Phanariots in the Danubian Principalities|Establishment and contrasts}}Danubian Principalities== | |||

| A crucial moment in the policy change was the ] of ]-], when ] sided with Russia and agreed to a Russian tutelage over his country. After Russia suffered a major defeat and Cantemir went into ], the Ottomans took charge of the succession to the throne of Moldavia, soon followed by similar measures in Wallachia (in this case, prompted by ]'s alliance with the Habsburg commander ] in the closing stages of the ]). | |||

| ], engraving from 1763]] | |||

| A Greek presence had established itself in both Danubian Principalities of ] and ], resulting in the appointment of Greek princes before the 18th century. After the Phanariot era, some Phanariot families in Wallachia and Moldavia identified themselves as ] in ]n society (including the Rosetti family; ] represented the ], nationalist cause during and after the ].). | |||

| ==Characteristics== | |||

| ===Rulers and retinues=== | |||

| ], built in ] by ], in an 1868 ] by ]]] | |||

| The person raised to the princely dignity was usually the chief ] of the ], and was consequently well versed in contemporary politics and the statecraft of the ] government. | |||

| Phanariot attention focused on occupying the most favorable offices the empire could offer non-Muslims and the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which were still relatively rich and—more importantly—autonomous (despite having to pay tribute as ] states). Many Greeks had found favorable conditions there for commercial activities, in comparison with the Ottoman Empire, and an opportunity for political power; they entered Wallachian and Moldavian ] nobility by marriage. | |||

| The new Prince, who obtained his office in exchange for a heavy ] (not a new requirement in itself), proceeded to the country which he was selected to govern, and of the language of which he was in most cases totally ignorant. Once the new Princes were appointed, they were escorted to ] or ] by ]s composed of their families, favourites, and their creditors (from whom they had borrowed the bribe funds). The prince and his appointees counted on recouping themselves in as short a time as possible for their initial outlay and in laying by a sufficiency to live on after the termination of the Princes' brief authority. | |||

| Reigns of local princes were not excluded on principle. Several ] Romanian noble families, such as the ]s (originally ''Călmașul''), the ]s and the Albanian ]s penetrated the Phanar nucleus to increase their chances of occupying the thrones and maintain their positions. | |||

| As a total for the two principalities together, 31 princes from 11 different families have ruled during the Phanariote epoch. Many times they were exiled or even executed: of these 31 princes, seven suffered a violent death, and a few were executed at their own courts of Bucharest or Iaşi. The fight for the throne could become as harsh as to provoke murders carried out among members of the same family. | |||

| Most sources agree that 1711 was when the gradual erosion of traditional institutions reached its zenith, but characteristics ascribed to the Phanariot era had made themselves felt long before it.<ref>See the historiographical discussion in Drace-Francis, ''The Making of Modern Romanian Culture'', p. 26, note 6.</ref> The Ottomans enforced their choice of ]s as far back as the 15th century, and foreign (usually Greek or ]ine) ]s competed with local ones since the late 16th century. Rulers since Dumitraşcu ] in Moldavia and ] (a prince of Greek origin) in Wallachia, both in 1673, were forced to surrender their family members as hostages in Constantinople. The traditional ] in the principalities, resulting in long periods of political disorder, was dominated by a small number of ambitious families who competed violently for the two thrones and monopolized land ownership.<ref>Djuvara, pp. 123, 125–26.</ref> | |||

| When, owing to relatively numerous cases of treachery among the Princes, the choice became limited to a few families, it became frequent that rulers would be shifted from one principality to the other: the Prince of Wallachia, the richer of the two Principalities, would pay certain sums in order to avert his transfer to Iaşi, while the Prince of Moldavia would bribe supporters in Constantinople in exchange for his appointment to Wallachia. For example, ] accumulated a total of ten different rules in Moldavia and Wallachia. The debt was, however, owed to various creditors, and not to the ] himself: in fact, the central institutions of the Ottoman Empire generally seemed determined to maintain their rule over the Principalities, and not exploit them irrationally. In one early example, ] even paid part of ]' sum. | |||

| ===1711–1715=== | |||

| ], built in ] by ], in an 1868 ] by ]]] | |||

| A change in policy was indicated by the fact that autonomous Wallachia and Moldavia had entered a period of skirmishes with the Ottomans, due to the insubordination of local princes associated with the rise of ]'s power under ] and the firm presence of the Habsburg Empire on the ] border with the principalities. Dissidence in the two countries became dangerous for the Turks, who were confronted with the attraction on the population of protection by a fellow ] state. This became obvious with ]'s second rule in Moldavia, when the prince plotted with Peter to have Ottoman rule overthrown. His replacement, ], was the first official Phanariot in his second reign in Moldavia and replaced ] in Wallachia as the first Phanariot ruler of that country. | |||

| A crucial moment was the ] of 1710−1713, when ] sided with Russia and agreed to Russian tutelage of his country. After Russia experienced a major defeat and Cantemir went into exile, the Ottomans took charge of the succession to the throne of Moldavia. This was followed by similar measures in Wallachia, prompted by ]'s alliance with Habsburg commander ] in the closing stages of the ]. | |||

| ===Rulers and retinues=== | |||

| ]. The caption reads: "Flight of ] from ] while '']'' troops approach / 9 Nov 1789".]] | |||

| The person raised to the office of prince was usually the chief ] of the Porte, well-versed in contemporary politics and Ottoman statecraft. The new prince, who obtained his office in exchange for a generous bribe, proceeded to the country he was selected to govern (whose language he usually did not know). When the new princes were appointed, they were escorted to ] or ] by retinues composed of their families, favourites and creditors (from whom they had borrowed the bribes). The prince and his appointees counted on recouping these in as short a time as possible, amassing an amount sufficient to live on after their brief time in office. | |||

| Thirty-one princes, from eleven families, ruled the two principalities during the Phanariot epoch. When the choice became limited to a few families due to princely disloyalty to the Porte, rulers would be moved from one principality to the other; the prince of Wallachia (the richer of the two principalities) would pay to avert his transfer to Iaşi, and the prince of Moldavia would bribe supporters in Constantinople to appoint him to Wallachia. ] ruled a total of ten times in ] and ]. The debt was owed to several creditors, rather than to the Sultan; the central institutions of the Ottoman Empire generally seemed determined to maintain their rule over the principalities and not exploit them irrationally. In an early example, ] paid part of ]' sum. | |||

| ===Administration and boyars=== | ===Administration and boyars=== | ||

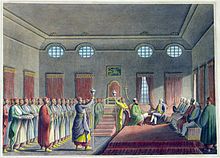

| ] welcoming the ] ambassador in ]]] | |||

| The |

The Phanariot epoch was initially characterized by fiscal policies driven by Ottoman needs and the ambitions of some hospodars, who (mindful of their fragile status) sought to pay back their creditors and increase their wealth while in a position of power. To make the reigns lucrative while raising funds to satisfy the needs of the Porte, princes channeled their energies into taxing the inhabitants into destitution. The most odious taxes (such as the '']'' first imposed by ] in the 1580s), mistakenly identified with the Phanariots in modern Romanian historiography, were much older. | ||

| The |

The mismanagement of many Phanariot rulers contrasts with the achievements and projects of others, such as Constantine Mavrocordatos (who abolished ] in Wallachia in 1746 and Moldavia in 1749) and ], who were inspired by Habsburg serf policy. Ypsilantis tried to reform legislation and impose salaries for administrative offices in an effort to halt the depletion of funds the administrators, local and Greek alike, were using for their own maintenance; it was, by then, more profitable to hold office than to own land. His ''Pravilniceasca condică'', a relatively modern ], met stiff ] resistance. | ||

| The focus of such rules was often the improvement of state structure against conservative wishes. Contemporary documents indicate that, despite the change in leadership and boyar complaints, about 80 percent of those seated in the ] (an institution roughly equivalent to the ]) were members of local families.<ref>Djuvara, p.124</ref> This made endemic the social and economic issues of previous periods, since the inner circle of boyars blocked initiatives (such as Alexander Ypsilantis') and obtained, extended and preserved ]s.<ref>Djuvara, p.69</ref> | |||

| == Russian influence == | |||

| After the ] (]) allowed Russia to intervene on the side of Ottoman Eastern Orthodox subjects, most of the Turkish political pressures became ineffective. The Porte had to further offer concessions, with the imperative of maintaining hold over the countries as economical and stategic assets: the treaty made any increase in the tribute impossible, and, between 1774 and the 1820s, it plummeted from around 50,000 to 20,000 ]s (equivalent to ]) in Wallachia, and just 3,100 in Moldavia.<ref>Berza</ref> | |||

| The Phanariots copied Russian and Habsburg institutions; during the mid-18th century they made noble rank dependent on state service, as ] did. After the ] (1774) allowed Russia to intervene on the side of Ottoman Eastern Orthodox subjects, most of the Porte's tools of political pressure became ineffective. They had to offer concessions to maintain a hold on the countries as economic and strategic assets. The treaty made any increase in tribute impossible, and between 1774 and the 1820s it plummeted from about 50,000 to 20,000 ]s (equivalent to ]) in Wallachia and to 3,100 in Moldavia.<ref>Berza</ref> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In the immediately following period, Russia made use of its new prerogative with notable force: the deposition of ] (in Wallachia) and ] (in Moldavia) by ], called on by the ]'s ], ] (whose fears of pro-Russian ] in Bucharest were partly confirmed), constituted the '']'' for the ] (the Russian general ] swiftly reinstated Ypsilantis during his military expedition to Wallachia). | |||

| Immediately afterward, Russia forcefully used its new prerogative. The deposition of ] (in Wallachia) and ] (in Moldavia) by ], called on by ]'s ] ] (whose fears of pro−Russian ] in Bucharest were partially confirmed), was the '']'' for the 1806–1812 conflict, and Russian general ] swiftly reinstated Ypsilantis during his military expedition to Wallachia. | |||

| Such gestures inaugurated a period of effective Russian supervision, which culminated with the '']'' administration of the 1830s; the Danubian Principalities grew in strategic importance with the ] and the ], as European states became interested in halting ] (of which a noted development was the annexation of ] in ]). In turn, the new ] opened in the two countries' capitals, as a means to ensure observation of developments in Russian-Ottoman relations, had an indirect impact over the local economy, as rival diplomats began awarding their protection and '']'' status to merchands competing with the local ]s. | |||

| Such gestures began a period of effective Russian supervision, culminating with the ] administration of the 1830s. The Danubian principalities grew in strategic importance with the ] and the ], as European states became interested in halting ] (which included the 1812 annexation of ]). New ] in the two countries' capitals, ensuring the observation of developments in Russian−Ottoman relations, had an indirect impact on the local economy as rival diplomats began awarding protection and '']'' status to merchants competing with local ]s. ] pressured Wallachia and Moldavia into granting constitutions (in 1831 and 1832, respectively) to weaken native rulers.<ref>A History of the Balkans 1804–1945, p. 47</ref> | |||

| In parallel, the boyars started a ] campaign against the Princes in power: although sometimes addressed to the Porte and even the ], they mostly demanded Russian supervision. While making reference to cases of ] and misrule, the petitions show their signers' conservative intentions. The boyars tend to refer to specific, but nonetheless fictitious, '']'' that either of the Principalities would have signed with the Ottomans - demanding that the rights guaranteed through them be restored.<ref>Djuvara, p.123</ref> They also viewed with suspicion reform attempts on the side of Princes, claiming these were not legitimate - in alternative proposals (usually taking the form of ] projects), the boyars express a wish for the establishment of an ].<ref>Djuvara, p.319</ref> | |||

| The ] began a petition campaign against the princes in power; addressed to the Porte and the ], they primarily demanded Russian supervision. Although they referred to incidents of ] and misrule, the petitions indicate their signers' conservatism. The boyars tend to refer to (fictitious) "]" which either principality would have signed with the Ottomans, demanding that rights guaranteed through them be restored.<ref>Djuvara, p. 123</ref> They viewed reform attempts by princes as illegitimate; in alternative proposals (usually in the form of constitutional projects), the boyars expressed desire for an ].<ref>Djuvara, p. 319</ref> | |||

| ===Ending and legacy=== | |||

| :''Main article: ]'' | |||

| The active part taken by the Greek Princes in revolts after ] (''see ]''), together with the chaos provoked by ] occupation in Moldavia and ]'s ], led to the disappearance of promotions from within the Phanar community. Relevant for the tense relations between boyars and princes, Vladimirescu's revolt was, for most of its duration, the result of compromise between ]n ] and the ] of boyars attemptingto block the ascention of ], the last Phanariote ruler in Bucharest.<ref>Djuvara, p.89</ref> | |||

| ==Greek War of Independence and legacy== | |||

| ]'s rule in Moldavia and Grigore IV Ghica's in Wallachia are considered the first of the new period: as such, the new regime was to have its own abrupt ending with the Russian occupation during another ], and the subsequent period of Russian influence (''see ]''). | |||

| ] (1792–1828), prince of the ], senior ] cavalry officer during the ] and leader of the ], commanded the ] in ] and planned a pan-Balkan uprising.]] | |||

| The active part taken by Greek princes in revolts after 1820 and the disorder provoked by the ] (of which the ], ] and Golescu families were active members<ref>Alex Drace-Francis, ''The Making of Modern Romanian Culture: Literacy and the Development of National Identity'', p.87, 2006, I.B.Tauris, {{ISBN|1-84511-066-8}}</ref> after its uprising against the Ottoman Empire in Moldavia and ]'s ]) led to the disappearance of promotions from the ] community; the Greeks were no longer trusted by the Porte. Amid tense relations between boyars and princes, Vladimirescu's revolt was primarily the result of compromise between ]n ] and the ] of boyars attempting to block the ascension of ] (the last Phanariot ruler in Bucharest).<ref>Djuvara, p.89</ref> ]'s rule in Moldavia and ]'s in Wallachia are considered the first of the new period, although the new regime abruptly ended in Russian occupation during another ] and the subsequent period of Russian influence. | |||

| Most Phanariots were patrons of ], education and printing. They founded academies which attracted teachers and pupils from throughout the ] commonwealth, and there was awareness of intellectual trends in ] Europe.<ref name=BritB/> Many of the Phanariot princes were capable, farsighted rulers. As prince of Wallachia in 1746 and Moldavia in 1749, ] abolished serfdom and ] of Wallachia (reigned 1774–1782) initiated extensive administrative and legal reforms. Ipsilanti's reign coincided with subtle shifts in economic and social life and the emergence of spiritual and intellectual aspirations which pointed to the West and reform.<ref name="BritC">Encyclopædia Britannica,''History of Romania, Romania Between Turkey and Austria'',2008, O.Ed.</ref> | |||

| Condemnation of the Phanariotes is a particular focus of ]n ], usually integrated with the resentment of foreigners as a whole. The tendency unifies pro- and anti-modernising attitudes: Phanariotes may represent ] elements (as their image was presented by ]), as well as agents of brutal and opportunistic change (as illustrated by ]'s '']''). | |||

| Condemnation of the Phanariots is a focus of ]n nationalism, usually integrated into a general resentment of foreigners. The tendency unifies pro− and anti−modernisation attitudes; Phanariot Greeks are painted as reactionary elements (by ]) and agents of brutal, opportunistic change (as in ]'s ''Scrisoarea a III-a''). | |||

| ==Leading Phanariote families== | |||

| *] | |||

| =={{anchor|Leading Phanariot families}}Extant Phanariot families== | |||

| *] (Caragea) | |||

| ] coat of arms]] | |||

| *] (Ghica) | |||

| ] (1896–1972), wife of ]]] | |||

| *] (Mavrocordat) | |||

| ] (1859–1944), diplomat, historian and essayist]] | |||

| *] (Mavrogheni) | |||

| ] coat of arms]] | |||

| *] (Moruzi) | |||

| ] | |||

| *] (Ruset/Russeti) | |||

| ] | |||

| *] (Suţu) | |||

| *] (Ipsilanti) | |||

| Here is a non-exhaustive list of Phanariot families: | |||

| * ], ] family originally from central ], ] emperors. | |||

| * ], noble family of the ] also known as ], see ]. | |||

| * Athanasovici | |||

| * ], also known as Călmașu, Kalmaşu or Kallimaşu, originally a Romanian boyar family from ]. | |||

| * Callivazis, originally from ], relocated to the Russian Empire. | |||

| * ], claimed to be originated from the ] noble family ]. | |||

| * ], also known as Caragea or Karatzas. | |||

| * Caratheodoris family, see also ] | |||

| * Cariophyllis | |||

| * Chrisoscoleos | |||

| * Chrisovergis, also known as Hrisovergis, from the ] | |||

| * Caravia family, noble family from the Ionian Islands, a branch of the Byzantine ] | |||

| * Diamandis | |||

| * ], also known as Dukas, ] family originally from ], ] ]. | |||

| * Evalidis, also known as Evaoglous, Hadjievalidis, from ] | |||

| * Gerakis, from ] | |||

| * Geralis, from ] and ] | |||

| * ], originally ] from ] | |||

| * Hantzeris, also known as Handjeri, Hançeri, Pıçakçı and Hançeroglou, see ] | |||

| * Kanellos, also known as Kanellou or Canello, originally from ] (see ]) | |||

| * Kavadas, from ] | |||

| * ], also known as Komnenus or Comnenos, including its cadet branches of ], Axouchos or Afouxechos, from ], ] and ] emperors. | |||

| * Lambrinos | |||

| * Lapithis, from ] | |||

| * Lazaridis, also known as Lazarević, a Serbianized family originally from Montenegro. | |||

| * Lermis, also known as Lermioglous or Lermilis, from ]. | |||

| * ] officials on the ] and dignitaries in the Imperial Court (]). | |||

| * Mamonas | |||

| * Manos, originated from ], see ] | |||

| * ], from ], see ]. | |||

| * ], from ], see ]. | |||

| * Mavroudis | |||

| * ], see ] | |||

| * Musurus, see ] | |||

| * ], ] family originally from central ], later ] | |||

| * Photeinos | |||

| * ], noble family of the ]. | |||

| * ], from ], later a political family in the ]. | |||

| * Rizos Rangavis, see ] | |||

| * ], also known as Racovitza, ] noble family from ] and ]. | |||

| * Ramalo | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Romalo | |||

| * ], also known as Ruset or Russeti, ]n Boyar family of Byzantine and ]n origins. | |||

| * Scanavis | |||

| * Schinas | |||

| * Sereslis | |||

| * ], also known as Suțu, Sutzu or Sütçü, see ]. | |||

| * Tzanavarakis, also known Tzanavaris, Çanavaris or Canavaroğulları. | |||

| * Venturas | |||

| * Vlachoutzis | |||

| * ], Romanian boyars from ] and the first poets in Romanian literature<ref>Encyclopædia Britannica, ''Vacarescu family'', 2008, O.Ed.</ref> | |||

| * ], from ] | |||

| * ], from ], see ] and ] | |||

| =={{anchor|Extinct Phanariot families}}Extinct Phanariot families== | |||

| ].<ref>{{cite EB1911|wstitle= Mavrocordato | volume= 17 | page = 917 |quote= the name of a family of Phanariot Greeks, distinguished in the history of Turkey, Rumania and modern Greece}}</ref>]] | |||

| * Aristarchis | |||

| * Ballasakis | |||

| * Cananos | |||

| * Caryophyles | |||

| * Dimakis | |||

| * Eupragiotes | |||

| * Iancoleos (della Rocca) | |||

| * Moronas | |||

| * Negris | |||

| * Paladas, from ] | |||

| * Plaginos | |||

| * Rizos Neroulos | |||

| * Ramadan | |||

| * Souldjaroglou | |||

| * Tzoukes | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| ==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| {{Reflist|2}} | |||

| <div class="references-small"> | |||

| <references/> | |||

| </div> | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| *{{EB1911|wstitle=Phanariotes | volume= 21 | page = 346}} | |||

| *{{1911}} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| *Mihai Berza, "Haraciul Moldovei şi al Ţării Româneşti în sec. XV–XIX", in ''Studii şi Materiale de Istorie Medie'', II, 1957, p.7–47 | |||

| | last=Mamboury | |||

| *], ''Între Orient şi Occident. Ţările române la începutul epocii moderne'', Humanitas, Bucharest, 1995 | |||

| | first= Ernest | |||

| *Vlad Georgescu, ''Istoria ideilor politice româneşti (1369-1878)'', Munich, 1987 | |||

| | author-link= Ernest Mamboury | |||

| | title=The Tourists' Istanbul | |||

| | publisher=Çituri Biraderler Basımevi | |||

| | location=Istanbul | |||

| | year=1953 | |||

| }} | |||

| *Mihai Berza, "Haraciul Moldovei și al Țării Românești în sec. XV–XIX", in ''Studii și Materiale de Istorie Medie'', II, 1957, p. 7–47 | |||

| *Alex Drace-Francis, ''The Making of Modern Romanian Culture'', London & New York, 2006, {{ISBN|1845110668}} | |||

| *], ''Între Orient și Occident. Țările române la începutul epocii moderne'', Humanitas, Bucharest, 1995 | |||

| *Vlad Georgescu, ''Istoria ideilor politice românești (1369–1878)'', Munich, 1987 | |||

| *{{cite book | last=Glenny | first=Misha | title=The Balkans: Nationalism, War & the Great Powers, 1804–1999 | publisher=Penguin (Non−Classics) | year=2001 | isbn=0140233776}} | |||

| *Eric Hobsbawm, ''Age of Revolutions'', section "Greek War of Independence" | *Eric Hobsbawm, ''Age of Revolutions'', section "Greek War of Independence" | ||

| *Konstantinos Paparrigopoulos ( |

*Konstantinos Paparrigopoulos (Pavlos Karolidis), ''History of the Hellenic Nation'' (Volume Eb), Eleftheroudakis, Athens, 1925 | ||

| *L. S. Stavrianos, ''The Balkans Since 1453'' | *L. S. Stavrianos, '']'' | ||

| *{{cite book | last=Svoronos | first=Nikos | title=The Greek Nation | publisher=Polis | year=2004 | |

*{{cite book | last=Svoronos | first=Nikos | title=The Greek Nation | publisher=Polis | year=2004 | isbn=9604350285 | chapter=The Ideology of the Organization and of the Survival of the Nation}} | ||

| {{Greek War of Independence}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 17:14, 30 November 2024

Greek nobility from Phanar, Constantinople

Phanariots, Phanariotes, or Fanariots (Greek: Φαναριώτες, Romanian: Fanarioți, Turkish: Fenerliler) were members of prominent Greek families in Phanar (Φανάρι, modern Fener), the chief Greek quarter of Constantinople where the Ecumenical Patriarchate is located, who traditionally occupied four important positions in the Ottoman Empire: Voivode of Moldavia, Voivode of Wallachia, Grand Dragoman of the Porte and Grand Dragoman of the Fleet. Despite their cosmopolitanism and often-Western education, the Phanariots were aware of their Greek ancestry and culture; according to Nicholas Mavrocordatos' Philotheou Parerga, "We are a race completely Hellenic".

They emerged as a class of wealthy Greek merchants (of mostly noble Byzantine descent) during the second half of the 16th century, and were influential in the administration of the Ottoman Empire's Balkan domains in the 18th century. The Phanariots usually built their houses in the Phanar quarter to be near the court of the Patriarch, who (under the Ottoman millet system) was recognized as the spiritual and secular head (millet-bashi) of the Orthodox subjects—the Rum Millet, or "Roman nation" of the empire, except those under the spiritual care of the Patriarchs of Antioch, Jerusalem, Alexandria, Ohrid and Peja—often acting as archontes of the Ecumenical See. They dominated the administration of the patriarchate, often intervening in the selection of hierarchs (including the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople).

Overview

Many members of Phanariot families (who had acquired great wealth and influence during the 17th century) occupied high political and administrative posts in the Ottoman Empire. From 1669 until the Greek War of Independence in 1821, Phanariots made up the majority of the dragomans to the Ottoman government (the Porte) and foreign embassies due to the Greeks' higher level of education than the general Ottoman population. With the church dignitaries, local notables from the provinces and the large Greek merchant class, Phanariots represented the better-educated members of Greek society during Ottoman rule until the 1821 start of the Greek War of Independence. During the war, Phanariots influenced decisions by the Greek National Assembly (the representative body of Greek revolutionaries, which met six times between 1821 and 1829). Between 1711–1716 and 1821, a number of Phanariots were appointed Hospodars (voivodes or princes) in the Danubian Principalities (Moldavia and Wallachia) (usually as a promotion from the offices of Dragoman of the Fleet and Dragoman of the Porte); the period is known as the Phanariot epoch in Romanian history.

Ottoman Empire

| This section's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. The reason given is: This section makes assumptions that are no longer considered historical consensus, and alludes multiple times to the Ottoman Decline Thesis, which is now considered a minority opinion. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (May 2022) |

After the fall of Constantinople, Mehmet II deported the city's Christian population, leaving only the Jewish inhabitants of Balat, repopulating the city with Christians and Muslims from throughout the whole empire and the newly conquered territories. Phanar was repopulated with Greeks from Mouchlion in the Peloponnese and, after 1461, with citizens of the Empire of Trebizond.

The roots of Greek ascendancy can be traced to the Ottoman need for skilled, educated negotiators as their empire declined and they relied on treaties rather than force. During the 17th century, the Ottomans began having problems in foreign relations and difficulty dictating terms to their neighbours; for the first time, the Porte needed to participate in diplomatic negotiations.

With the Ottomans traditionally ignoring Western European languages and cultures, officials were at a loss. The Porte assigned those tasks to the Greeks, who had a long mercantile and educational tradition and the necessary skills. The Phanariots and other Greek as well as Hellenized families primarily from Constantinople, occupied high posts as secretaries and interpreters for Ottoman officials.

Diplomats and patriarchs

As a result of Phanariot and ecclesiastical administration, the Greeks expanded their influence in the 18th-century empire while retaining their Greek Orthodox faith and Hellenism. This had not always been the case in the Ottoman realm. During the 16th century, the South Slavs—the most prominent in imperial affairs—converted to Islam to enjoy the full rights of Ottoman citizenship (especially in the Eyalet of Bosnia; Serbs tended to occupy high military positions.

A Slavic presence in Ottoman administration gradually became hazardous for its rulers, since the Slavs tended to support Habsburg armies during the Great Turkish War. By the 17th century the Greek Patriarch of Constantinople was the religious and administrative ruler of the empire's Orthodox subjects, regardless of ethnic background. All formerly-independent Orthodox patriarchates, including the Serbian Patriarchate renewed in 1557, came under the authority of the Greek Orthodox Church. Most of the Greek patriarchs were drawn from the Phanariots.

Two Greek social groups emerged, challenging the leadership of the Greek Church: the Phanariots in Constantinople and the local notables in the Helladic provinces (kodjabashis, dimogerontes and prokritoi). According to 19th-century Greek historian Constantine Paparrigopoulos, the Phanariots initially sought the most important secular offices of the patriarchal court and could frequently intervene in the election of bishops and influence crucial decisions by the patriarch. Greek merchants and clergy of Byzantine aristocratic origin, who acquired economic and political influence and were later known as Phanariots, settled in extreme northwestern Constantinople (which had become central to Greek interests after the establishment of the patriarch's headquarters in 1461, shortly after Hagia Sophia was converted into a mosque).

Patriarchate

After the 1453 fall of Constantinople, when the Sultan replaced de jure the Byzantine Emperor for subjugated Christians, he recognized the Ecumenical Patriarch as the religious and national leader (ethnarch) of the Greeks and other ethnic groups in the Greek Orthodox Millet. The Patriarchate had primary importance, occupying this key role for Christians of the Empire because the Ottomans did not legally distinguish between nationality and religion and considered the empire's Orthodox Christians a single entity.

The position of the Patriarchate in the Ottoman state encouraged Greek renaissance projects centering on the resurrection and revitalization of the Byzantine Empire. The Patriarch and his church dignitaries constituted the first centre of power for the Greeks in the Ottoman state, which infiltrated Ottoman structures and attracted the former Byzantine nobility.

Merchant middle class

The wealth of the extensive Greek merchant class provided the material basis for the intellectual revival featured in Greek life for more than half a century before 1821. Greek merchants endowed libraries and schools. On the eve of the Greek War of Independence, the three most important centres of Greek learning (schools-cum-universities) were in the commercial centres of Chios, Smyrna and Aivali. The first Greek millionaire of the Ottoman era was Michael "Şeytanoğlu" Kantakouzenos, who earned 60,000 ducats a year from his control of the fur trade from Muscovy.

Civil servants

During the 18th century, the Phanariots were a hereditary clerical−aristocratic group who managed the affairs of the patriarchate and the dominant political power of the Ottoman Greek community. They became a significant political factor in the empire and, as diplomatic agents, played a role in the affairs of Great Britain, France and the Russian Empire.

The Phanariots competed for the most important administrative offices in the Ottoman administration; these included collecting imperial taxes, monopolies on commerce, working under contract in a number of enterprises, supplying the court and ruling the Danubian Principalities. They engaged in private trade, controlling the crucial wheat trade on the Black Sea. The Phanariots expanded their commercial activities into the Kingdom of Hungary and then to the other Central European states. Their activities intensified their contacts with Western nations, and they became familiar with Western languages and cultures.

Before the beginning of the Greek War of Independence, the Phanariots were firmly established as the political elite of Hellenism. According to Greek historian Constantine Paparrigopoulos, this was a natural evolution given the Phanariots' education and experience in supervising large parts of the empire. According to Nikos Svoronos argued, the Phanariots subordinated their national identity to their class identity and tried to peacefully co−exist with the Ottomans; they did not enrich the Greek national identity and lost ground to groups which flourished through their confrontation with the Ottoman Empire (the klephts and armatoloi).

Danubian Principalities

A Greek presence had established itself in both Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, resulting in the appointment of Greek princes before the 18th century. After the Phanariot era, some Phanariot families in Wallachia and Moldavia identified themselves as Romanian in Romanian society (including the Rosetti family; C. A. Rosetti represented the radical, nationalist cause during and after the 1848 Wallachian revolution.).

Phanariot attention focused on occupying the most favorable offices the empire could offer non-Muslims and the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which were still relatively rich and—more importantly—autonomous (despite having to pay tribute as vassal states). Many Greeks had found favorable conditions there for commercial activities, in comparison with the Ottoman Empire, and an opportunity for political power; they entered Wallachian and Moldavian boyar nobility by marriage.

Reigns of local princes were not excluded on principle. Several hellenized Romanian noble families, such as the Callimachis (originally Călmașul), the Racovițăs and the Albanian Ghicas penetrated the Phanar nucleus to increase their chances of occupying the thrones and maintain their positions.

Most sources agree that 1711 was when the gradual erosion of traditional institutions reached its zenith, but characteristics ascribed to the Phanariot era had made themselves felt long before it. The Ottomans enforced their choice of hospodars as far back as the 15th century, and foreign (usually Greek or Levantine) boyars competed with local ones since the late 16th century. Rulers since Dumitraşcu Cantacuzino in Moldavia and George Ducas (a prince of Greek origin) in Wallachia, both in 1673, were forced to surrender their family members as hostages in Constantinople. The traditional elective system in the principalities, resulting in long periods of political disorder, was dominated by a small number of ambitious families who competed violently for the two thrones and monopolized land ownership.

1711–1715

A change in policy was indicated by the fact that autonomous Wallachia and Moldavia had entered a period of skirmishes with the Ottomans, due to the insubordination of local princes associated with the rise of Imperial Russia's power under Peter the Great and the firm presence of the Habsburg Empire on the Carpathian border with the principalities. Dissidence in the two countries became dangerous for the Turks, who were confronted with the attraction on the population of protection by a fellow Eastern Orthodox state. This became obvious with Mihai Racoviță's second rule in Moldavia, when the prince plotted with Peter to have Ottoman rule overthrown. His replacement, Nicholas Mavrocordatos, was the first official Phanariot in his second reign in Moldavia and replaced Ștefan Cantacuzino in Wallachia as the first Phanariot ruler of that country.

A crucial moment was the Russo−Turkish War of 1710−1713, when Dimitrie Cantemir sided with Russia and agreed to Russian tutelage of his country. After Russia experienced a major defeat and Cantemir went into exile, the Ottomans took charge of the succession to the throne of Moldavia. This was followed by similar measures in Wallachia, prompted by Ștefan Cantacuzino's alliance with Habsburg commander Prince Eugene of Savoy in the closing stages of the Great Turkish War.

Rulers and retinues

The person raised to the office of prince was usually the chief dragoman of the Porte, well-versed in contemporary politics and Ottoman statecraft. The new prince, who obtained his office in exchange for a generous bribe, proceeded to the country he was selected to govern (whose language he usually did not know). When the new princes were appointed, they were escorted to Iași or Bucharest by retinues composed of their families, favourites and creditors (from whom they had borrowed the bribes). The prince and his appointees counted on recouping these in as short a time as possible, amassing an amount sufficient to live on after their brief time in office.

Thirty-one princes, from eleven families, ruled the two principalities during the Phanariot epoch. When the choice became limited to a few families due to princely disloyalty to the Porte, rulers would be moved from one principality to the other; the prince of Wallachia (the richer of the two principalities) would pay to avert his transfer to Iaşi, and the prince of Moldavia would bribe supporters in Constantinople to appoint him to Wallachia. Constantine Mavrocordatos ruled a total of ten times in Moldavia and Wallachia. The debt was owed to several creditors, rather than to the Sultan; the central institutions of the Ottoman Empire generally seemed determined to maintain their rule over the principalities and not exploit them irrationally. In an early example, Ahmed III paid part of Nicholas Mavrocordatos' sum.

Administration and boyars

The Phanariot epoch was initially characterized by fiscal policies driven by Ottoman needs and the ambitions of some hospodars, who (mindful of their fragile status) sought to pay back their creditors and increase their wealth while in a position of power. To make the reigns lucrative while raising funds to satisfy the needs of the Porte, princes channeled their energies into taxing the inhabitants into destitution. The most odious taxes (such as the văcărit first imposed by Iancu Sasul in the 1580s), mistakenly identified with the Phanariots in modern Romanian historiography, were much older.

The mismanagement of many Phanariot rulers contrasts with the achievements and projects of others, such as Constantine Mavrocordatos (who abolished serfdom in Wallachia in 1746 and Moldavia in 1749) and Alexander Ypsilantis, who were inspired by Habsburg serf policy. Ypsilantis tried to reform legislation and impose salaries for administrative offices in an effort to halt the depletion of funds the administrators, local and Greek alike, were using for their own maintenance; it was, by then, more profitable to hold office than to own land. His Pravilniceasca condică, a relatively modern legal code, met stiff boyar resistance.

The focus of such rules was often the improvement of state structure against conservative wishes. Contemporary documents indicate that, despite the change in leadership and boyar complaints, about 80 percent of those seated in the Divan (an institution roughly equivalent to the estates of the realm) were members of local families. This made endemic the social and economic issues of previous periods, since the inner circle of boyars blocked initiatives (such as Alexander Ypsilantis') and obtained, extended and preserved tax exemptions.

Russian influence

The Phanariots copied Russian and Habsburg institutions; during the mid-18th century they made noble rank dependent on state service, as Peter I of Russia did. After the Treaty of Kuchuk-Kainarji (1774) allowed Russia to intervene on the side of Ottoman Eastern Orthodox subjects, most of the Porte's tools of political pressure became ineffective. They had to offer concessions to maintain a hold on the countries as economic and strategic assets. The treaty made any increase in tribute impossible, and between 1774 and the 1820s it plummeted from about 50,000 to 20,000 gold coins (equivalent to Austrian gold currency) in Wallachia and to 3,100 in Moldavia.

Immediately afterward, Russia forcefully used its new prerogative. The deposition of Constantine Ypsilantis (in Wallachia) and Alexander Mourousis (in Moldavia) by Selim III, called on by French Empire's ambassador to the Ottoman Empire Horace Sébastiani (whose fears of pro−Russian conspiracies in Bucharest were partially confirmed), was the casus belli for the 1806–1812 conflict, and Russian general Mikhail Andreyevich Miloradovich swiftly reinstated Ypsilantis during his military expedition to Wallachia.

Such gestures began a period of effective Russian supervision, culminating with the Organic Statute administration of the 1830s. The Danubian principalities grew in strategic importance with the Napoleonic Wars and the decline of the Ottoman Empire, as European states became interested in halting Russian southward expansion (which included the 1812 annexation of Bessarabia). New consulates in the two countries' capitals, ensuring the observation of developments in Russian−Ottoman relations, had an indirect impact on the local economy as rival diplomats began awarding protection and sudit status to merchants competing with local guilds. Nicholas I of Russia pressured Wallachia and Moldavia into granting constitutions (in 1831 and 1832, respectively) to weaken native rulers.

The boyars began a petition campaign against the princes in power; addressed to the Porte and the Habsburg monarchy, they primarily demanded Russian supervision. Although they referred to incidents of corruption and misrule, the petitions indicate their signers' conservatism. The boyars tend to refer to (fictitious) "capitulations" which either principality would have signed with the Ottomans, demanding that rights guaranteed through them be restored. They viewed reform attempts by princes as illegitimate; in alternative proposals (usually in the form of constitutional projects), the boyars expressed desire for an aristocratic republic.

Greek War of Independence and legacy

The active part taken by Greek princes in revolts after 1820 and the disorder provoked by the Filiki Eteria (of which the Ghica, Văcărescu and Golescu families were active members after its uprising against the Ottoman Empire in Moldavia and Tudor Vladimirescu's Wallachian uprising) led to the disappearance of promotions from the Phanar community; the Greeks were no longer trusted by the Porte. Amid tense relations between boyars and princes, Vladimirescu's revolt was primarily the result of compromise between Oltenian pandurs and the regency of boyars attempting to block the ascension of Scarlat Callimachi (the last Phanariot ruler in Bucharest). Ioan Sturdza's rule in Moldavia and Grigore IV Ghica's in Wallachia are considered the first of the new period, although the new regime abruptly ended in Russian occupation during another Russo−Turkish War and the subsequent period of Russian influence.

Most Phanariots were patrons of Greek culture, education and printing. They founded academies which attracted teachers and pupils from throughout the Orthodox commonwealth, and there was awareness of intellectual trends in Habsburg Europe. Many of the Phanariot princes were capable, farsighted rulers. As prince of Wallachia in 1746 and Moldavia in 1749, Constantine Mavrocordatos abolished serfdom and Alexander Ypsilantis of Wallachia (reigned 1774–1782) initiated extensive administrative and legal reforms. Ipsilanti's reign coincided with subtle shifts in economic and social life and the emergence of spiritual and intellectual aspirations which pointed to the West and reform.

Condemnation of the Phanariots is a focus of Romanian nationalism, usually integrated into a general resentment of foreigners. The tendency unifies pro− and anti−modernisation attitudes; Phanariot Greeks are painted as reactionary elements (by Communist Romania) and agents of brutal, opportunistic change (as in Mihai Eminescu's Scrisoarea a III-a).

Extant Phanariot families

Here is a non-exhaustive list of Phanariot families:

- Angelos, imperial family originally from central Philadelphia, Byzantine emperors.

- Argyropoulos, noble family of the Byzantine Empire also known as Argyros, see John Argyropoulos.

- Athanasovici

- Callimachi family, also known as Călmașu, Kalmaşu or Kallimaşu, originally a Romanian boyar family from Moldavia.

- Callivazis, originally from Trebizond, relocated to the Russian Empire.

- Cantacuzino, claimed to be originated from the Byzantine noble family Kantakouzenos.

- Caradjas, also known as Caragea or Karatzas.

- Caratheodoris family, see also Constantin Carathéodory

- Cariophyllis

- Chrisoscoleos

- Chrisovergis, also known as Hrisovergis, from the Peloponnese

- Caravia family, noble family from the Ionian Islands, a branch of the Byzantine Kallergi House

- Diamandis

- Doukas, also known as Dukas, imperial family originally from Paphlagonia, Despotate of Epirus despots.

- Evalidis, also known as Evaoglous, Hadjievalidis, from Trebizond

- Gerakis, from Kefalonia

- Geralis, from Mytilene and Kefalonia

- Ghica family, originally Albanians from Macedonia

- Hantzeris, also known as Handjeri, Hançeri, Pıçakçı and Hançeroglou, see Constantine Hangerli

- Kanellos, also known as Kanellou or Canello, originally from Chios (see Stefanos Kanellos)

- Kavadas, from Chios

- Komnenos, also known as Komnenus or Comnenos, including its cadet branches of Axouch, Axouchos or Afouxechos, from Trebizond, Byzantine and Trebizond emperors.

- Lambrinos

- Lapithis, from Crete

- Lazaridis, also known as Lazarević, a Serbianized family originally from Montenegro.

- Lermis, also known as Lermioglous or Lermilis, from Pontus.

- Levidis officials on the Patriarchate and dignitaries in the Imperial Court (Sublime Porte).

- Mamonas

- Manos, originated from Kastoria, see Aspasia Manos

- Mavrocordatos, from Chios, see Alexandros Mavrokordatos.

- Mavrogenis, from Paros, see Manto Mavrogenous.

- Mavroudis

- Mourouzis family, see Alexander Mourouzis

- Musurus, see Marcus Musurus

- Palaiologos, imperial family originally from central Asia minor, later marquesses of Montferrat

- Photeinos

- Philanthropenos, noble family of the Byzantine Empire.

- Rallis, from Chios, later a political family in the Hellenic Republic.

- Rizos Rangavis, see Alexandros Rizos Rangavis

- Racoviță, also known as Racovitza, Romanian noble family from Moldavia and Wallachia.

- Ramalo

- Rodocanachi

- Romalo

- Rosetti family, also known as Ruset or Russeti, Moldavian Boyar family of Byzantine and Genoan origins.

- Scanavis

- Schinas

- Sereslis

- Soutzos family, also known as Suțu, Sutzu or Sütçü, see Michael Soutzos.

- Tzanavarakis, also known Tzanavaris, Çanavaris or Canavaroğulları.

- Venturas

- Vlachoutzis

- Văcărescu family, Romanian boyars from Wallachia and the first poets in Romanian literature

- Vlastos, from Crete

- Ypsilantis, from Trebizond, see Alexander Ypsilantis and Demetrios Ypsilantis

Extinct Phanariot families

- Aristarchis

- Ballasakis

- Cananos

- Caryophyles

- Dimakis

- Eupragiotes

- Iancoleos (della Rocca)

- Moronas

- Negris

- Paladas, from Crete

- Plaginos

- Rizos Neroulos

- Ramadan

- Souldjaroglou

- Tzoukes

See also

- Ottoman Greeks

- Diafotismos

- Greeks in Romania

- Bulgarian Exarchate

- Early modern Romania

- Danubian Principalities

- List of rulers of Moldavia

- List of rulers of Wallachia

- History of the Russo-Turkish wars

- State organisation of the Ottoman Empire

Notes

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Phanariotes". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 346.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Phanariotes". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 346.

- The names Fener and Φανάρι (Fanari) derive from the Greek nautical word meaning "Lighthouse" (literary "lantern" or "lamp")

"Τριανταφυλλίδης On line Dictionary". Φανάρι (ναυτ.). Retrieved October 7, 2006. - Mavrocordatos Nicholaos, Philotheou Parerga, J.Bouchard, 1989, p.178, citation: Γένος μεν ημίν των άγαν Ελλήνων

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, The Phanariots, 2008, O.Ed.

- ^ Paparregopoulus, Eb, p. 108.

- ^ Mamboury (1953), p. 98

- Mamboury (1953), p. 99

- ^ Stavrianos, p. 270

- ^ Hobsbawm pp. 181–85.

- Svoronos, p. 87

- ^ Svoronos, p. 88.

- Glenny, p. 195.

- ^ Svoronos, p. 83.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Greek history, The mercantile middle class, 2008 ed.

- Steven Runciman. The Great Church in Captivity. Cambridge University Press, 1988, page 197.

- Svoronos, p. 89.

- Svoronos, p. 91.

- See the historiographical discussion in Drace-Francis, The Making of Modern Romanian Culture, p. 26, note 6.

- Djuvara, pp. 123, 125–26.

- Djuvara, p.124

- Djuvara, p.69

- Berza

- A History of the Balkans 1804–1945, p. 47

- Djuvara, p. 123

- Djuvara, p. 319

- Alex Drace-Francis, The Making of Modern Romanian Culture: Literacy and the Development of National Identity, p.87, 2006, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1-84511-066-8

- Djuvara, p.89

- Encyclopædia Britannica,History of Romania, Romania Between Turkey and Austria,2008, O.Ed.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Vacarescu family, 2008, O.Ed.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Mavrocordato" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 917.

the name of a family of Phanariot Greeks, distinguished in the history of Turkey, Rumania and modern Greece

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Phanariotes". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 346.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Phanariotes". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 346.- Mamboury, Ernest (1953). The Tourists' Istanbul. Istanbul: Çituri Biraderler Basımevi.

- Mihai Berza, "Haraciul Moldovei și al Țării Românești în sec. XV–XIX", in Studii și Materiale de Istorie Medie, II, 1957, p. 7–47

- Alex Drace-Francis, The Making of Modern Romanian Culture, London & New York, 2006, ISBN 1845110668

- Neagu Djuvara, Între Orient și Occident. Țările române la începutul epocii moderne, Humanitas, Bucharest, 1995

- Vlad Georgescu, Istoria ideilor politice românești (1369–1878), Munich, 1987

- Glenny, Misha (2001). The Balkans: Nationalism, War & the Great Powers, 1804–1999. Penguin (Non−Classics). ISBN 0140233776.

- Eric Hobsbawm, Age of Revolutions, section "Greek War of Independence"

- Konstantinos Paparrigopoulos (Pavlos Karolidis), History of the Hellenic Nation (Volume Eb), Eleftheroudakis, Athens, 1925

- L. S. Stavrianos, The Balkans Since 1453

- Svoronos, Nikos (2004). "The Ideology of the Organization and of the Survival of the Nation". The Greek Nation. Polis. ISBN 9604350285.

- Performers of Byzantine music

- Culture of the Ottoman Empire

- Christianity in the Ottoman Empire

- Demographics of the Ottoman Empire

- People from the Ottoman Empire by descent

- Government of the Ottoman Empire

- Greek diaspora

- History of Moldavia (1711–1822)

- History of Wallachia (1714–1821)

- Ottoman period in the Balkans

- Greece–Turkey relations

- Eastern Orthodox Christian culture

- Politics of the Greek War of Independence