| Revision as of 22:09, 20 January 2018 editSorabino (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users25,397 edits →Bibliography← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:05, 9 December 2024 edit undoJoy (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators144,152 editsm use the same term for the link (WP:NOTBROKEN), link terms (WP:BUILDTHEWEB) | ||

| (286 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Medieval Balkan principality}} | |||

| {{refimprove|date=December 2015}} | |||

| {{Infobox country | |||

| {{Other uses2|Hum}} | |||

| |native_name = Захумље<br />''Zahumlje'' | |||

| ] during Early Middle Ages]] | |||

| |conventional_long_name = Principality of Zachlumia | |||

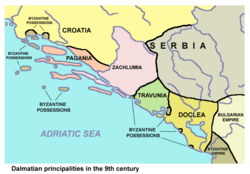

| '''Zachlumia''' or '''Zachumlia''' ({{lang-sr|Захумље / Zahumlje}}; {{lang-hr|Zahumlje}}; {{IPA-sh|zǎxuːmʎe|pron}}), also '''Hum''', was a ] ]<ref>{{harvnb|Velikonja|2003|p=44}}: "Byzantium and Bulgaria scrambled for control over the Serbian principalities of Duklja, Rascia and Zahumlje."</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Bideleux|Jeffries|2007|p=234}}: "The first independent and recognizably Serbian polities emerged in 1037–38 in Zahumlje and Travunia..."</ref> principality located in the modern-day regions of ] and southern ] (today parts of ] and ], respectively). In some periods it was a fully independent or semi-independent ] principality. It maintained relations with various foreign and neighbouring powers (], ], ], ]) and later was subjected (temporarily of for a longer period of time) to ], ], ], ] and at the end to the ]. | |||

| |common_name = | |||

| |event_start = Established | |||

| |year_start = 9th century | |||

| |date_start = | |||

| |year_end = 1054 | |||

| |date_end = | |||

| |event_end = Conquered by ] | |||

| |p1 = Principality of Serbia (early medieval){{!}}Principality of Serbia | |||

| |image_p1 = ] | |||

| |p2 = Byzantine Empire | |||

| |image_p2 = ] | |||

| |s1 = Duklja | |||

| |flag_s1 = | |||

| |s2 = | |||

| |image_s2 = | |||

| |image_coat = | |||

| |symbol_type = | |||

| |image_map = Paganija, Zahumlje, Travunija, Duklja, Croatian view.png | |||

| |image_map_caption = Zachlumia in 9th century | |||

| |capital = | |||

| |stat_area1 = | |||

| |leader1 = ] <small>(first known)</small> | |||

| |year_leader1 = 910–935 | |||

| |leader2 = ] <small>(last independent)</small> | |||

| |year_leader2 = 1039–1054 | |||

| |title_leader = Prince | |||

| |government_type = ] | |||

| |religion = ] | |||

| |common_languages = | |||

| |today = ]<br /> ] | |||

| |category= | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Zachlumia''' or '''Zachumlia''' ({{lang-sh-Latn-Cyrl|separator=" / "|Zahumlje|Захумље}}, {{IPA|sh|zǎxuːmʎe|pron}}), also '''Hum''', was a ] principality located in the modern-day regions of ] and southern ] (today parts of ] and ], respectively). In some periods it was a fully independent or semi-independent ] principality. It maintained relations with various foreign and neighbouring powers (], ], ], ]) and later was subjected (temporarily or for a longer period) to ], ], ], and at the end to the ]. | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| Zachlumia is a derivative of ''Hum'', from Proto-Slavic '']'', borrowed from a Germanic language (cf. Proto-Germanic '']''), meaning ''"Hill"''.<ref>Entry "холм" in М. Фасмер (1986), ''Этимологический Словарь Русского Языка'' (Москва: Прогресс), 2-е изд. — Перевод с немецкого и дополнения О.Н. Трубачёва.</ref> South Slavic ''Zahumlje'' is named after the mountain of Hum (za + Hum "behind the Hum"), above ], at the mouth of the ]. The principality is named ''Zahumlje'' or ''Hum'' in ] (]: Захумље, Хум). It is ''Zachlumia'' in Latin, Хлъмъ in ], and Ζαχλούμων χώρα ("land of Zachlumians") in Greek. The names ''Chelmania'', ''Chulmia'' and ''terra de Chelmo'' appear in later Latin and Italian chronicles. | Zachlumia is a derivative of ''Hum'', from Proto-Slavic '']'', borrowed from a Germanic language (cf. Proto-Germanic '']''), meaning ''"Hill"''.<ref>Entry "холм" in М. Фасмер (1986), ''Этимологический Словарь Русского Языка'' (Москва: Прогресс), 2-е изд. — Перевод с немецкого и дополнения О.Н. Трубачёва.</ref> South Slavic ''Zahumlje'' is named after the ] (za + Hum "behind the Hum"), above ], at the mouth of the ].{{citation needed|date=September 2022}} The principality is named ''Zahumlje'' or ''Hum'' in ] (]: Захумље, Хум). It is ''Zachlumia'' in Latin, Хлъмъ in ], and Ζαχλούμων χώρα ("land of Zachlumians") in Greek. The names ''Chelmania'', ''Chulmia'' and ''terra de Chelmo'' appear in later Latin and Italian chronicles. | ||

| ==Geography== | ==Geography== | ||

| {{unreferenced section|date=December 2023}} | |||

| '']'' described the polity of Zachlumia, likely during the reign of ] (r. 927-960): ''"From Ragusa begins the domain of the Zachloumoi (Ζαχλοῦμοι) and stretches along as far as the river Orontius; and on the side of the coast it is neighbour to the Pagani, but on the side of the mountain country it is neighbour to the Croats on the north and to Serbia at the front ... The Zachloumoi that now live there are Serbs, originating from the time of the ] who fled to emperor Heraclius ... The land of the Zachloumoi comprise the following cities: Ston (το Σταγνον / to Stagnon), Mokriskik (το Μοκρισκικ), Josli (το Ιοσλε / to Iosle), Galumainik (το Γαλυμαενικ / to Galumaenik), Dobriskik (το Δοβρισκικ / to Dovriskik)"'' | |||

| '']'' described the polity of Zachlumia as: ''"From Ragusa begins the domain of the Zachlumi (Ζαχλοῦμοι) and stretches along as far as the river Orontius: and on the side of the coast it is neighbour to the Pagani, but on the side of the mountain country it is neighbour to the Croats on the north and to Serbia at the front ... Those who live there now, Zachlumi, are Serbs, from the time of that prince who claimed the protection of the Emperor ]. In the territory of the Zachlumi are the inhabited cities of Stagnon, Mokriskik, Iosli, Galoumainik, Dobriskik"''.{{sfn|Moravcsik|1967|p=145, 161, 163}} | |||

| The '']'' (14th or 16th century) described the geography under the rule of the South Slavic rulers, Hum had two major cities: Bona and Hum. The main settlements in Zachlumia were ], ], ], the towns of Mokriski and ]. The Principality sprang from ] (]) to the northwest and ] to the west; to the mountain of ] and the Field of Gatak, where it bordered ]. The most eastern border of Zahumlje went along the line ]-]-] and met with the Travunian border at the city of ], which had to pay the annual tax ''mogorish'' of 36 pieces of gold to the Zachlumian rulers and at times accept their rule.{{when|date=December 2015}} Zachlumia was split on 9 ]nates: ], ], Dubrava, ], ], Žapska, Gorička and ] around ]. Zahumlje had access to the Adriatic Sea with the ] peninsula and faced ] northwards.{{Citation needed|date=November 2010}} | |||

| In its later periods,{{when|date=July 2012}} Zahumlje was split into two Duchies: Upper Zahumlje in the west and Lower Zahumlje in the east.{{Citation needed|date=November 2010}} | |||

| The '']'' (14th or 16th century) described the geography under the rule of the South Slavic ("]") rulers, Hum had two major cities: Bona and Hum. The main settlements in Zachlumia were ], ], ], the towns of ] and ]. The principality sprang from ] (]) to the northwest and ] to the west; to the mountain of ] and the ], where it bordered ]. The eastern border of Zahumlje went along the line ]-]-] and met with the Travunian border at the city of ]. Zachlumia was split on 9 ]: ], ], Dubrava, ], ], Žapska, Gorička and ] around ]. Zahumlje had access to the Adriatic Sea with the ] peninsula and faced ] northwards.{{Citation needed|date=November 2010}} | |||

| As the toponym ''Pagania'' disappeared by the turn of the 11th century, the land of Hum was expanded to include the territory between Neretva and Cetina previously referred to as Pagania. This territory was at the time controlled by local magnates called Radivojevići, Jurjevići or Vlatkovići.<ref>{{cite journal | url = http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=42249 | language = Croatian | title = Vjerske prilike na području knezova Jurjevića – Vlatkovića | first = Dijana | last = Korać | number = 49 |date=December 2007 | publisher = Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts | location = Zadar | issn = 1330-0474 | accessdate = 2012-07-09}}</ref> | |||

| ==Slavic settlement== | ==Slavic settlement== | ||

| Slavs invaded Balkans during ] (r. 527–565), when eventually up to 100,000 Slavs raided ]. The Western Balkans was settled with '']'' (Sklavenoi), the east with ]. |

Slavs invaded Balkans during ] (r. 527–565), when eventually up to 100,000 Slavs raided ]. The Western Balkans was settled with '']'' (Sklavenoi), the east with ].{{sfn|Hupchick|2002|p=}} The Sklavenoi plundered Thrace in 545, and again the next year. In 551, the Slavs crossed ] initially headed for Thessalonica, but ended up in ].{{sfn|Janković|2004|p=39-61}} In 577 some 100,000 Slavs poured into ] and ], pillaging cities and settling down.<ref>J B Bury, ''History of the Later Roman Empire from Arcadius to Irene'', Vol 2 </ref> Hum had also a large number of ] who were descendent from a pre-Slavic population. Related to Romanians and originally speaking a language related to Romanian, the Vlachs of what was Hum are today Slavic speaking.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=19}} | ||

| the Vlachs of what was Hum are today slavic speaking<ref>John V. A. Fine,John Van Antwerp Fine, The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century ...University of Michigan Press, 1994 p.19</ref> | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| Line 26: | Line 55: | ||

| ===7th century=== | ===7th century=== | ||

| {{See also|Migration period}} | {{See also|Migration period}} | ||

| In the second decade of the 7th century, the ] and their ] subjects occupied most of the ], including the territory of what would become Zahumlje, sacking towns and enslaving or displacing the local population. Some of the Slavs and Avars might have permanently settled in the occupied areas. They attacked ] in 626 but were defeated by the Byzantines, after which the Avars ceased to play a significant role in the ]. |

In the second decade of the 7th century, the ] and their ] subjects occupied most of the ], including the territory of what would become Zahumlje, sacking towns and enslaving or displacing the local population. Some of the Slavs and Avars might have permanently settled in the occupied areas. They attacked ] in 626 but were defeated by the Byzantines, after which the Avars ceased to play a significant role in the ].{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=25}} | ||

| Around 630, during the reign of ] ], ] and ] (Slavic tribes) led by their respective aristocracies entered the western Balkans from the north, which was approved by the emperor. They inhabited areas that had been devastated by the Avars, where Byzantium (East Roman Empire) had generally been reduced to only nominal rule. According to ''DAI'', Zahumlje was one of the regions settled by the Serbs from ] who previously arrived there from ],{{sfn|Ćirković|2004|p=12}} but a closer reading of the source suggests that the Constantine VII's consideration about the population's ethnic identity is based on Serbian political rule and influence during the time of ] and does not indicate ethnic origin.<ref>{{harvnb|Dvornik|Jenkins|Lewis|Moravcsik|1962|pp=139, 142}}: He probably saw that in his time all these tribes were in the Serb sphere of influence, and therefore called them Serbs, thus ante-dating by three centuries the state of affairs in his day... It is obvious that the small retinue of the Serbian prince could not have populated Serbia, Zachlumia, Terbounia and Narenta.</ref>{{sfn|Curta|2006|p=210|ps=: According to Constantine Porphyrogenitus, the Slavs of the Dalmatian zhupanias of Pagania, Zahumlje, Travounia, and Konavli all "descended from the unbaptized Serbs."51 This has been rightly interpreted as an indication that in the mid-tenth century the coastal zhupanias were under the control of the Serbian zhupan Časlav, who ruled over the regions in the interior and extended his power westwards across the mountains to the coast.}}{{sfn|Živković|2006|p=60–61|ps=:Data on the family origin of Mihailo Višević indicate that his family did not belong to a Serbian or Croatian tribe, but to another Slavic tribe who lived along the Vistula River and who joined the Serbs during the migration during the reign of Emperor Heraclius. The introduction of Mihajlo Višević and his family by Porphyrogenitus suggests that the rulers of Zahumlje until his time belonged to this ruling family, so that, both in Serbia and Croatia, and in Zahumlje, there would be a very early established principle of inheriting power by members of one family. Constantine Porphyrogenitus explicitly calls the inhabitants of Zahumlje Serbs who have settled there since the time of Emperor Heraclius, but we cannot be certain that the Travunians, Zachlumians and Narentines in the migration period to the Balkans were Serbs or Croats or Slavic tribes which in alliance with Serbs or Croats arrived in the Balkans. The emperor-writer says that all these principalities are inhabited by Serbs, but this is a view from his time when the process of ethnogenesis had already reached such a stage that the Serbian name became widespread and generally accepted throughout the land due to Serbia's political domination. Therefore, it could be concluded that in the middle of the 10th century the process of ethnogenesis in Zahumlje, Travunija, and Paganija was probably completed, because the emperor's informant collected data from his surroundings and transferred to Constantinople the tribal sense of belonging of the inhabitants of these archons ... The Byzantine writings on the De Ceremoniis, which were also written under the patronage of Constantine Porphyrogenitus, listed the imperial orders to the surrounding peoples. The writings cite orders from the archons of Croats, Serbs, Zahumljani, Kanalites, Travunians, Duklja and Moravia. The above-mentioned orders may have originated at the earliest during the reign of Emperor Theophilus (829 - 842) and represent the earliest evidence of the political fragmentation of the South Slavic principalities, that is, they confirm their very early formation. It is not known when Zahumlje was formed as a separate principality. All the news that Constantine Porphyrogenitus provides about this area agrees that it has always been so - that is, since the seventh-century settlement in the time of Emperor Heraclius. It is most probable that the prefects in the coastal principalities recognized the supreme authority of the Serbian ruler from the very beginning, but that they aspired to become independent, which took place according to the list of orders preserved in the book De Ceremoniis, no later than the first half of the 9th century. A falsified and highly controversial papal charter from 743 also mentions Zahumlje and Travunija as separate areas. If the basic information about these countries were correct, it would mean that they formed as very early principalities that were practically independent of the archon of Serbia.}}<ref>{{Cite book|last=Budak|first=Neven|author-link=Neven Budak|title=Prva stoljeća Hrvatske|year=1994|location=Zagreb|publisher=Hrvatska sveučilišna naklada|url=http://inet1.ffst.hr/_download/repository/Budak_1994.pdf|pages=58–61|quote=Pri tome je car dosljedno izostavljao Dukljane iz ove srpske zajednice naroda. Čini se, međutim, očitim da car ne želi govoriti ο stvarnoj etničkoj povezanosti, već da su mu pred očima politički odnosi u trenutku kada je pisao djelo, odnosno iz vremena kada su za nj prikupljani podaci u Dalmaciji.|isbn=953-169-032-4|access-date=2019-05-04|archive-date=2019-05-04|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190504192532/http://inet1.ffst.hr/_download/repository/Budak_1994.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{citation |last=Gračanin |first=Hrvoje |date=2008 |title=Od Hrvata pak koji su stigli u Dalmaciju odvojio se jedan dio i zavladao Ilirikom i Panonijom: Razmatranja uz DAI c. 30, 75-78 |url=https://hrcak.srce.hr/36767?lang=hr |journal=Povijest U Nastavi |volume=VI |issue=11 |pages=67–76 |language=hr |quote=Izneseni nalazi navode na zaključak da se Hrvati nisu uopće naselili u južnoj Panoniji tijekom izvorne seobe sa sjevera na jug, iako je moguće da su pojedine manje skupine zaostale na tom području utopivši se naposljetku u premoćnoj množini ostalih doseljenih slavenskih populacija. Širenje starohrvatskih populacija s juga na sjever pripada vremenu od 10. stoljeća nadalje i povezano je s izmijenjenim političkim prilikama, jačanjem i širenjem rane hrvatske države. Na temelju svega ovoga mnogo je vjerojatnije da etnonim "Hrvati" i doseoba skrivaju činjenicu o prijenosu političke vlasti, što znači da je car političko vrhovništvo poistovjetio s etničkom nazočnošću. Točno takav pristup je primijenio pretvarajući Zahumljane, Travunjane i Neretljane u Srbe (DAI, c. 33, 8-9, 34, 4-7, 36, 5-7).}}</ref><ref>{{citation |first=Neven |last=Budak |author-link=Neven Budak |year=2018 |title=Hrvatska povijest od 550. do 1100. |trans-title=Croatian history from 550 until 1100 |url=http://www.leykam-international.hr/publikacija.php?id=167 |publisher=Leykam international |isbn=978-953-340-061-7 |pages=51, 177 |quote=Sporovi hrvatske i srpske historiografije oko etničkoga karaktera sklavinija između Cetine i Drača bespredmetni su, jer transponiraju suvremene kategorije etniciteta u rani srednji vijek u kojem se identitet shvaćao drukčije. Osim toga, opstojnost većine sklavinija, a pogotovo Duklje (Zete) govori i u prilog ustrajanju na vlastitom identitetu kojim su se njihove elite razlikovale od onih susjednih ... Međutim, nakon nekog vremena (možda poslije unutarnjih sukoba u Hrvatskoj) promijenio je svoj položaj i prihvatio vrhovništvo srpskog vladara jer Konstantin tvrdi da su Zahumljani (kao i Neretvani i Travunjani) bili Srbi od vremena onog arhonta koji je Srbe, za vrijeme Heraklija, doveo u njihovu novu domovinu. Ta tvrdnja, naravno, nema veze sa stvarnošću 7. st., ali govori o političkim odnosima u Konstantinovo vrijeme. |access-date=2020-12-27 |archive-date=2022-10-03 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221003170102/https://www.leykam-international.hr/publikacija.php?id=167 |url-status=dead }}</ref> According to ], today's western Serbia was area where Serbs settled in 7th century and from there they expanded their rule on territory of Zachlumia.{{sfn|Malcolm|1995|p=10-11}} According to ] the area of the Vistula where the ] ancestors of ] originate was the place where ] would be expected and not ],<ref>{{cite journal |last=Živković |first=Tibor |author-link=Tibor Živković |date=2001 |title=О северним границама Србије у раном средњем веку |trans-title=On the northern borders of Serbia in the early middle ages |url=http://www.rastko.rs/cms/files/books/5ab96732d39f6 |language=sr |journal=Zbornik Matice srpske za istoriju |volume=63/64 |page=11 |quote=Plemena u Zahumlju, Paganiji, Travuniji i Konavlima Porfirogenit naziva Srbima,28 razdvajajuči pritom njihovo političko od etničkog bića.29 Ovakvo tumačenje verovatno nije najsrećnije jer za Mihaila Viševića, kneza Zahumljana, kaže da je poreklom sa Visle od roda Licika,30 a ta je reka isuviše daleko od oblasti Belih Srba i gde bi pre trebalo očekivati Bele Hrvate. To je prva indicija koja ukazuje da je srpsko pleme možda bilo na čelu većeg saveza slovenskih plemena koja su sa njim i pod vrhovnim vodstvom srpskog arhonta došla na Balkansko poluostrvo.}}</ref> and it's unclear whether the Zachlumians "in the migration period to the Balkans really were Serbs or Croats or Slavic tribes which in alliance with Serbs or Croats arrived in the Balkans".{{sfn|Živković|2006|p=60}} According to ] the Zachlumians "had a closer bond of interest with the Croats than with the Serbs, since they seem to have migrated to their new home not with the Serbs, but with the Croats".<ref>{{harvnb|Dvornik|Jenkins|Lewis|Moravcsik|1962|p=139}}: Even if we reject Gruber's theory, supported by Manojlović (ibid., XLIX), that Zachlumje actually became a part of Croatia, it should be emphasized that the Zachlumians had a closer bond of interest with the Croats than with the Serbs, since they seem to have migrated to their new home not, as C. says (33/8-9), with the Serbs, but with the Croats; see below, on 33/18-19 ... If this is so, we must regard the dynasty of Zachlumje and at any rate part of its people as neither Croat nor Serb, It seems more probable that Michael’s ancestor, together with his tribe, joined the Croats when they moved south; and settled on the Adriatic coast and the Narenta, leaving the Croats to push on into Dalmatia proper.</ref> Michael's tribal origin is related to the oral tradition from '']'' by ] about seven or eight tribes of nobles called ''Lingones'' who arrived from ] and settled in ].{{sfn|Dvornik|Jenkins|Lewis|Moravcsik|1962|p=139}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Uzelac |first=Aleksandar |chapter=Prince Michael of Zahumlje – a Serbian ally of Tsar Simeon |chapter-url=https://www.academia.edu/36829282 |title= Emperor Symeon's Bulgaria in the History of Europe's South-East: 1100 years from the Battle of Achelous |editor1=Angel Nikolov |editor2=Nikolay Kanev |publisher=Univerzitetsvo izdatelstvo "Sveti Kliment Ohridski" |location=Sofia |year=2018 |page=237 |quote=...the enigmatic Litziki were associated with the archaic names of Poles(Lendizi, Liakhy),7 or with the Slavic tribe of Lingones mentioned by chronicler Adam of Bremen.8 Be that as it may, it is certain that, although his subjects were perceived as Serbs, the family of Prince Michael of Zahumlje did not descend from Serbs or Croats, and was not related to their dynasties.}}</ref>{{sfn|Živković|2006|p=75}}<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lončar |first1=Milenko |last2=Jurić |first2=Teuta Serreqi |date=2018 |title=Tamno more u spisu De administrando imperio: Baltičko ili Crno? |trans-title=The Dark Sea in De administrando imperio: The Baltic or the Black Sea? |url=https://hrcak.srce.hr/205615 |language=hr |journal=Povijesni prilozi |volume=37 |issue=54 |page=14 |quote=Kao potporna analogija može poslužiti i podrijetlo Mihaela Viševića, vladara Zahumljana s područja Visle.21 Teško da je netko drugi (osim njega samoga i njegova roda) iznosio takvu obavijest. Ista hrvatska tradicija, ponešto izmijenjena, zadržala se u Dalmaciji sve do 13. stoljeća kada ju spominje Toma Arhiđakon: "Iz krajeva Poljske došlo je s Totilom sedam ili osam uglednih plemena, koji se zovu Lingoni."2}}</ref> Much of Dalmatia was sometime earlier settled by the Croats, and Zahumlje bordered their territory on the north.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=32-33}} According to Thomas the Archdeacon, when describing the reign of Croatian king ] in the late 10th century, notes that Duchy of Hum (Zachlumia or Chulmie) was a part of the Kingdom of Croatia, before and after Stjepan Držislav: | |||

| Around 630, during the reign of ] ], ] and ] (Slavic tribes) led by their respective aristocracies entered the western Balkans from the north, which was approved by the emperor. They inhabited areas that had been devastated by the Avars, where Byzantium (East Roman Empire) had generally been reduced to only nominal rule. Zahumlje was one of the regions settled by the Serbs. Much of Dalmatia was some time earlier settled by the Croats, and Zahumlje bordered their territory on the north.<ref name=fineTSI/><ref name=dai32-33/> | |||

| {{blockquote| | |||

| The historical work Historia Salonitana by Thomas the Archdeacon, when describing the regin of Croatian king Stephen Držislav in the late 10th century, notes that Duchy of Hum (Zachlumia or Chulmie) was a part of the Kingdom of Croatia, before and after Stjepan Držislav. | |||

| {{quotation| | |||

| : | : | ||

| ''" |

''"Istaque fuerunt regni eorum confinia: ab oriente Delmina, ubi fuit civitas Delmis, ... ab occidente Carinthia, versus mare usque ad oppidum Stridonis, quod nunc est confinium Dalmatie et Ystrie; ab aquilone vero a ripa Danubii usque ad mare Dalmaticum cum tota Maronia et Chulmie ducatu."'' | ||

| ''" |

''"The boundaries of that kingdom were as follows. To the east: Delmina. ... To the west: Carinthia, towards the sea up to the town of Stridon, which now marks the boundary between Dalmatia and Istria. To the north, moreover: from the banks of the Danube down to the Dalmatian sea, including all of Maronia and the Duchy of Hum.''" | ||

| | ] | | ].{{sfn|Thomas of Split|2006|p=60–61}} | ||

| | ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| ===9th century=== | ===9th century=== | ||

| {{See also|Byzantine–Arab Wars (780–1180)}} | {{See also|Byzantine–Arab Wars (780–1180)}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ], ] from 768 until his death in 814, expanded the Frankish kingdom into an ] that incorporated much of western and central Europe. |

], ] from 768 until his death in 814, expanded the Frankish kingdom into an ] (800) that incorporated much of western and central Europe.{{sfn|Ross|1945|p=212–235}} He brought the Frankish state face to face with the ] to the northeast and the ] and ] to the southeast of the Frankish empire.{{sfn|Ross|1945|p=212–235}} Dalmatia which was southeast of the Frankish empire, was chiefly in the hands of South Slavic tribes.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=253}} North of Dubrovnik these came to be under Croatian ''župans'' (princes) and eventually came to consider themselves Croatians, while many of those to the south of Dubrovnik were coming to consider themselves Serbs.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=253}} Despite Frankish overlordship, the Franks had almost no role in Dalmatia (] and Zahumlje) in the period from the 820s through 840s.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=257}} | ||

| In 866, a major ] raid along ] struck ] and ], and then laid siege to ] in 867. |

In 866, a major ] raid along ] struck ] and ], and then laid siege to ] in 867.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=257}} The city of Dubrovnik appealed to ] ], who responded by sending over one hundred ships.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=257}} Finally, the 866–867 Saracens' siege of Dubrovnik, which lasted fifteen months, was raised due to the intervention of Basil I, who sent a fleet under the command of ] in relief of the city.{{sfn|Norris|1993|p=24}} After this successful intervention, the ] sailed along the coast collecting promises of loyalty to the empire from ].{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=257}} At this moment the local Slavic tribes (in Zahumlje, Travunija, and Konavle), who had aided the intervention, also accepted Byzantine suzerainty.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=257}} Afterwards, the Slavs of Dalmatia and Zahumlje took part in the Byzantine military actions against the Arabs in ] in 870–871.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=257}} The Roman cities in Dalmatia had long been pillaged by the Slavic tribes in the mountaines around them.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=257}} Basil I allowed the towns to pay tribute to the Slavic tribes to reduce the Slavs raiding.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=257}} Presumably a large portion of this tribute went to the prince of ].{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=257}} In late 870s, the ] ("thema Dalmatias") was established, but with no real Byzantine authority.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=258}} These small cities in the region (also ]) did not stretch into the hinterlands, and had none military capacity, thus Basil I paid a tax of '72 gold coins' to the princes of Zahumlje and Travunia.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=258}} | ||

| In 879, the ] asked for help from |

In 879, the ] asked for help from duke ] for an armed escort for his delegates across southern Dalmatia and Zahumlje. Later in 880, the Pope ask the same from Zdeslav's successor, prince ].{{citation needed|date=December 2015}} | ||

| ===10th century=== | ===10th century=== | ||

| {{See also|Michael of Zahumlje}} | {{See also|Michael of Zahumlje}} | ||

| ] and the ].]] | ] and the ].]] | ||

| The history of Zahumlje as a greater political entity starts with the emerging of ], an independent ] ruler who flourished in the early part of the 10th century. A neighbour of ] and ] as well as an ally of ], he was nevertheless able to maintain independent rule throughout at least a good part of his reign. |

The history of Zahumlje as a greater political entity starts with the emerging of ], an independent ] ruler who flourished in the early part of the 10th century. A neighbour of ] and ] as well as an ally of ], he was nevertheless able to maintain independent rule throughout at least a good part of his reign.{{sfn|Curta|2006|p=210|ps=: According to Constantine Porphyrogenitus, the Slavs of the Dalmatian zhupanias of Pagania, Zahumlje, Travounia, and Konavli all "descended from the unbaptized Serbs."51 This has been rightly interpreted as an indication that in the mid-tenth century the coastal zhupanias were under the control of the Serbian zhupan Časlav, who ruled over the regions in the interior and extended his power westwards across the mountains to the coast.}} | ||

| Michael have come into territorial conflict with the ], the ruler of Serbia, who was extending his power westwards. |

Michael have come into territorial conflict with the neighbouring prince ], the ruler of ], who was extending his power westwards.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=149}}{{sfn|Ćirković|2004|p=18}} To eliminate that threat and as a close ally of Bulgaria, Michael warned the Bulgarian Tsar ] about the alliance between Peter and Symeon's enemy, the ].{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=149}} In 912 Michael kidnapped the Venetian Doge's son Peter Badoari that was returning to Venice from Constantinople and sent him to Czar Simeon as a sign of loyalty. Symeon attacked inner Serbia and captured Peter, who later died in prison, and Michael was able to restore the majority of control.{{sfn|Moravcsik|1967|p=152-162}} | ||

| The ''Historia Salonitana maior'', whose composition may have begun in the late 13th century,<ref> |

The ''Historia Salonitana maior'', whose composition may have begun in the late 13th century,<ref>{{harvnb|Fine|2005|pp=54–55}}: "John the Deacon makes no mention of either council", "manuscript from the 16th century ''Historia Salonitana maior'' has long descriptions of the two councils" and "the labels of identity represent views from no earlier than the late 13th century, and possibly the 14th, 15th and 16th"</ref> cites a letter of ] to ], "king (''rex'') of the Croats", in which he refers to the first council in some detail. If the letter is authentic, it shows that the council was attended not only by the bishops of Croatian and Byzantine Dalmatia, but also by Tomislav, whose territory also included the Byzantine cities of Dalmatia, and by a number of Michael's representatives. Zahumlje may have been under Croatian influence, but remained a separate political entity. Both Zahumlje and Croatia were under the religious jurisdiction of the ]. In this letter, John describes Michael as "the most excellent leader of the Zachlumi" (''excellentissimus dux Chulmorum''),{{sfn|Vlasto|1970|p=209}}{{sfn|Ćirković|2004|p=17}} and is mentioned the Ston bishopric (''ecclesia Stagnensis'') which jurisdiction remained under Split until 1022.{{sfn|Dzino|2023|p=168}} It is uncertain whether the inscription and depiction of a Slavic ruler in the Church of St. Michael in Ston is a reference to Michael of Zahumlje, the 12th century ] or St. Michael himself.{{sfn|Dzino|2023|p=168–169}} | ||

| After the Italian city of ] ({{ |

After the Italian city of ] ({{langx|la|Sipontum}}) was heavily jeopardized by the raiding Arabs and Langobards, Mihailo won a magnificent military victory by taking the city upon the recommendations from Constantinople and orders from his ally, King Tomislav Trpimirovic, but didn't keep it permanently.{{sfn|Omrčanin|1984|p=24}} Mihailo Višević entered into closer relations with the Byzantine Empire, after the death of Bulgaria's Tsar Simeon. He gained the grand titles of the Byzantine court as '']'' and patrician ('']'').{{sfn|Moravcsik|1967|p=152-162}} He remained as ruler of Zahumlje into the 940s, while maintaining good relations with the ].{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=160}} | ||

| ====Post-Michael of Zahumlje period==== | |||

| The historical work '']'' by ], when describing the regin of Croatian king ] in the late 10th century, notes that Duchy of Hum (Chulmie) was a part of the ], before and after Stjepan Držislav.<ref name="Archdeacon 60–61">Archdeacon (2006), pp. 60–61.</ref> | |||

| After the death of Michael (after c. 930s or 940s), the fate of Zahumlje is uncertain due to lack of historical sources about it.{{sfn|Dzino|2023|p=169}} Some historians believe that Zahumlje came under the rule of prince ], but there's no evidence for it and ''DAI'' which was written in the mid-10th century clearly states that Zachlumia is a separate polity from Serbia.{{sfn|Dzino|2023|p=169}} The 13th century ] claimed that the Croatian kingdom included Zachlumia before and after ] (969–997), but that's also disputable.{{sfn|Dzino|2023|p=169}} | |||

| In the late 990s, Bulgarian Tsar Samuel made client states out of most of the Balkans, including Duklja and Zahumlje.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=274}}{{sfn|Dzino|2023|p=170}} In 998, Samuel launched a major campaign against ] to prevent a Byzantine-Serbian alliance, resulting in a surrender.{{sfn|Шишић|1928|p=331}} The Bulgarian troops proceeded to pass through ], taking control of ] and journeying to Dubrovnik. Although they failed to take Dubrovnik, they devastated the surrounding villages. The Bulgarian army then attacked Croatia in support of the rebel princes ] and ] and advanced northwest as far as ], ] and ], then northeast through ] and ] and returned to Bulgaria.{{sfn|Шишић|1928|p=331}}{{sfn|Dzino|2023|p=170}} | |||

| After the death of Mihailo, Zahumlje came under the rule of ], the last of the ] dynasty. With the death of Časlav, Serbia disintegrated and Duklja absorbed most of Rascia along with Zahumlje and Trebinje.<ref>Fine 1991, p. 193</ref> | |||

| In the 990s, Bulgarian Tsar Samuel made client states out of most of the Balkans, including Duklja and Zahumlje.<ref>Fine 1991, p. 274</ref> In 998, Samuel launched a major campaign against ] to prevent a Byzantine-Serbian alliance, resulting in a surrender.<ref name=sisc331>Šišić, p. 331.</ref> The Bulgarian troops proceeded to pass through ], taking control of ] and journeying to Dubrovnik. Although they failed to take Dubrovnik, they devastated the surrounding villages. The Bulgarian army then attacked Croatia in support of the rebel princes ] and ] and advanced northwest as far as ], ] and ], then northeast through ] and ] and returned to Bulgaria.<ref name=sisc331/> The ] allowed Samuel to install vassal monarchs in Croatia. | |||

| ===11th century=== | ===11th century=== | ||

| By 1020, Byzantine Emperor ] expanded control in the whole region, but the Byzantines used local elite to rule over local polities although under Byzantine vassalage and supervision of Byzantine officials.{{sfn|Dzino|2023|p=172}} In the ]'s bull from 27 September 1022 is mentioned Zahumlje kingdom (''regno Lachomis''), and would be again in the bull of ] from 1076 (as ''regno Zaculmi''), which confirmed the jurisdiction of the ].{{sfn|Dzino|2023|p=172}} | |||

| In a charter dated July 1039, ] who was an independent ] ruler of Zahumlje, styled himself ''"Ljutovit, ] epi tou Chrysotriklinou, hypatos, strategos"'' of Serbia and Zahumlje, which suggests the Byzantine Emperor granted him nominal right over neighbouring lands, including ].<ref name="Stephenson 42-43">Stephenson (2003), pp. 42-43.</ref> Ljutovid's claim to be strategos not only of Zahumlje, but all Serbia suggests that he had been courted by the emperor, and awarded nominal rights neighbouring lands, including Duklja, which was at the time at war with the empire.<ref name="Stephenson 42-43"/> If we can trust the ''Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja'', our only narrative source, we must conclude that none of the Serbian lands was under direct Byzantine control in 1042.<ref name="Stephenson 42-43"/> ] (fl. 1018-1043) soon took Zahumlje from the Byzantines.<ref name="Zlatar 572">Zlatar (2007), p. 572.</ref> During the rule of ] (r. 1081–1101), neither Bosnia, Rascia nor Zahumlje was ever integrated into Doclea, each retained its own nobility and institutions and simply acquired a ] to head the local structure as Prince or Duke.<ref>Fine 1991, p. 223</ref> Zahumlje subsequently became part of the ]. | |||

| In a charter dated July 1039, ] who was an independent ] ruler of Zahumlje, styled himself ''"Ljutovit, ] epi tou Chrysotriklinou, hypatos, strategos"'' of Serbia and Zahumlje. According to historian Paul Stephenson, it "suggests that he had been courted by the emperor, and awarded nominal rights neighbouring lands, including Duklja, which was at the time at war with the empire.{{sfn|Stephenson|2003|p=42-43}} | |||

| According to historical sources, the Serbian lands were under Byzantine control or vassalage until 1040s, but not under a direct control.{{sfn|Stephenson|2003|p=42-43}} ] (fl. 1018–1043) soon took Zahumlje from the Byzantines.{{sfn|Zlatar|2007|p=572}} During the rule of ] (r. 1081–1101), neither Bosnia, Serbia nor Zahumlje was ever integrated into Doclea, each retained its own nobility and institutions and simply acquired a ] to head the local structure as Prince or Duke.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=223}} Zahumlje subsequently became part of the ]. | |||

| ===12th century=== | ===12th century=== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ], the Prince of Duklja (r. 1102–1103), ruled in the name of ]. There was a split between the two, and Vukan sent forces to Duklja, making Kočapar flee to Bosnia and then Zahumlje, where he died. |

], the Prince of Duklja (r. 1102–1103), ruled in the name of ]. There was a split between the two, and Vukan sent forces to Duklja, making Kočapar flee to Bosnia and then Zahumlje, where he died.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=231}} ] ruled Zahumlje before getting into a conflict with his brothers, resulting in him being exiled to Duklja, where he would have the title of ''Lord of ]''.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=3}} ''Grand Princes'' ] (r. 1148–1162) and ] ruled Serbia together 1149–1153; Desa had the title of 'Prince of Duklja, Travunija and Zahumlje', mentioned in 1150 and 1151.{{CN|date=June 2023}} | ||

| About 1150, the Byzantine Emperor ] displeased with king ], divided up his lands between princes of the old Serbian family of Zavida, and ] secured the land of Hum. |

About 1150, the Byzantine Emperor ] displeased with king ], divided up his lands between princes of the old Serbian family of Zavida, and ] secured the land of Hum.{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=101}} After 1168 when Nemanja was raised to the Serbian throne with Manuel's favor, Hum passed to his brother ].{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=101}} He married a sister of ], who in meantime acquired the throne of ].{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=101}} The subjects of Miroslav and Kulin included both Catholic and Orthodox.{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=101}} Prince Miroslav himself was Orthodox.{{sfn|Fine|1975|p=114}} In meantime, both Bosnia and Hum had been fought between ] and ].{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=101}} The Catholics supported the former and the Orthodox the latter.{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=101}} A support of the growing heresy seemed the best solution for both Kulin and Miroslav.{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=101}} | ||

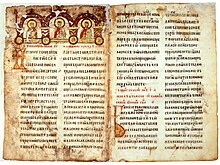

| ], one of the oldest surviving documents written in Serbian recension of ], |

], one of the oldest surviving documents written in Serbian recension of ], was created by order by prince ]]] | ||

| Following the death of Emperor Manuel in 1180 Miroslav started ecclesiastical superior of Hum. |

Following the death of Emperor Manuel in 1180 Miroslav started ecclesiastical superior of Hum.{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=102}} He refused to allow Rainer, Latin Archbishop of Spalato (]) whom he considered to be an agent of Hungarian king, to consecrate a bishop for the town of ].{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=102}} In addition, Miroslav confiscated the Archbishop's money.{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=102}} Rainer complained to the ], who sent Teobald to report on the matter.{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=102}} The Pope's nuncio Teobald found Miroslav as a patron of heretics.{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=102}} After this, the Pope wrote to king ] who was overlord of Hum (which Miroslav did not recognize), telling him to see that Miroslav performed his duty, but Miroslav remained as ''Prince of Hum''.{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=102}} In 1190–1192, Stefan Nemanja briefly assigned the rule of Hum to his son ], while Miroslav held the ] with ].{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=20-21}} Rastko however took monastic vows and Miroslav continued ruling Hum after 1192.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=20-21}} | ||

| Latin vengeance came in March 1198, when ] become the prince of Dalmatia, Croatia and Hum, while Miroslav died a year after and his wife was living in exile. |

Latin vengeance came in March 1198, when ] become the prince of Dalmatia, Croatia and Hum, while Miroslav died a year after and his wife was living in exile.{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=102}} The ] are the oldest surviving documents written in Serbian recension of ], very likely produced for the Church of St Peter in Lima, commissioned by prince Miroslav.{{sfn|Ćirković|2004|p=19}} | ||

| ===13th century=== | ===13th century=== | ||

| ] in 1265]] | ] in 1265]] | ||

| When ] became the first ] in 1219, he appointed ] as ]. | Until beginning of the 13th century, areas of Zahumlje were under jurisdiction of the Roman Church.<ref>{{cite journal|first=Milenko|last=Krešić|date=2016|title=Religious situation in the Hum land (Ston and Rat) during the Middle Ages|url=https://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=247029|journal=Hercegovina: Časopis za kulturno i povijesno naslijeđe|issue=2|page=66|doi=10.47960/2712-1844.2016.2.65|quote=Do početka 20-ih godina 13. stoljeća prostori Humske zemlje bili su pod jurisdikcijom zapadne, odnosno rimske Crkve.|doi-access=free}}</ref> When ] became the first ] in 1219, he appointed ] as the ]. | ||

| ] is entitled the rule of Hum, but the Hum nobility chose his brother ]. Andrija is exiled to Rascia, to the court of his cousin |

] is entitled the rule of Hum, but the Hum nobility chose his brother ]. Andrija is exiled to Rascia, to the court of his cousin Grand Prince ]. In the meantime, Petar fought successfully with neighbouring Bosnia and Croatia. Stefan Nemanjić sided with Andrija and went to war and secured Hum and Popovo field for Andrija sometime after his accession. Petar was defeated and crossed the Neretva, continuing to rule the west and north of the Neretva, which had around 1205 been briefly occupied by ].{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=52-54}}{{sfn|Ćirković|2004|p=37}} ], the son of ], succeeded as prince, ruling 1227–1237. Andrija's sons ], ] and ] succeed as princes of Hum in 1249, Radoslav held the supreme rule. During the war against Ragusa, he aided his kinsman ], at the same time swearing allegiance to ]. Following an earthquake in the Hum capital of Ston, the Serbian Orthodox bishop of Hum moved to the church of St Peter and St Paul built on the ] near the Serbian border in the 1250s.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=52-54}} | ||

| ] was from 1254 a vassal of Hungary, but probably afterwards his land were absorbed into Serbia. |

] was from 1254 a vassal of Hungary, but probably afterwards his land were absorbed into Serbia.{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=107}} However, he was at war with Serbia in 1268, while still under Hungarian suzerainty.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=203}} But seeking to centralize his realm, ] tried to stamp out regional differences by dropping references to Zahumlje (Hum), Trebinje and Duklja (Zeta), and called himself "King of all Serbian land and the Coast".{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=203}} Miroslav's descendants dropped to the level of other local nobles.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=203}} | ||

| ===14th century=== | ===14th century=== | ||

| {{ |

{{Further|Kingdom of Bosnia|Humska zemlja}} | ||

| ] as ] controlled Croatia from ] to the river ].<ref name="Fine 207-208">Fine (The Late Medieval Balkans – 1994), pp. 207–208.</ref> Paul became ] in 1299.<ref name="Fine 209-210">Fine (The Late Medieval Balkans – 1994), pp. 209–210.</ref> Although supporting the king, Paul continued to act independently, and ruled over a large portion of modern-day Croatia and Bosnia.<ref name="Fine 209-210"/> In the course of the war between ] and ], Paul Šubić expanded not only into western Hum, but also beyond the Neretva river, and took the region of ] and ].<ref name="Fine 258"/> In 1312, Hum was added to the title of ], who succeeded Paul.<ref name="Fine 258"/> At least part of Paul's conquests were granted to his vassal ].<ref name="Fine 258"/> After Paul's death, Milutin and Dragutin concluded a peace, and went to war against ].<ref name="Fine 258"/> In the war that followed Milutin took one of Mladen's brother captive, and to get him back Mladen Šubić had to agree to restore a part of Hum to Milutin.<ref name="Fine 258"/> After this agreement in 1313 the Neretva again became the border between eastern and western Hum.<ref name="Fine 258"/> | |||

| ] as ] controlled Croatia from ] to the river ].{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=207-208}} Paul became ] in 1299.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=209-210}} Although supporting the king, Paul continued to act independently, and ruled over a large portion of modern-day Croatia and Bosnia.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=209-210}} In the course of the war between ] and ], Paul Šubić expanded not only into western Hum, but also beyond the Neretva river, and took the region of ] and ].{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=258}} Paul appointed his eldest son, ], as Lord of Hum.{{sfn|Karbić|2004|p=17}} At least part of Paul's conquests were granted to his vassal ].{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=258}} Mladen succeeded his father in 1312. After Paul's death, Milutin and Dragutin concluded a peace, and went to war against the ].{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=258}} In the war that followed Milutin took one of Mladen's brother captive, and to get him back Mladen Šubić had to agree to restore a part of Hum to Milutin.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=258}} After this agreement in 1313 the Neretva again became the border between eastern and western Hum.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=258}} | |||

| By 1325, the ] had emerged as strongest in Hum.<ref name="Fine 266">Fine (The Late Medieval Balkans – 1994), pp. 266.</ref> Probably at their highest point they ruled from ] River to the town of ].<ref name="Fine 266"/> Though nominal vassals of Serbia, the Branivojević family attacked Serbian interests and other local nobles of Hum, who in 1326 turned against Serbia and Branivojević family.<ref name="Fine 266"/> The Hum nobles approached to ], the ban of Bosnia, who then annexed most of Hum.<ref name="Fine 266"/> The ] as vassals of Bosnian Ban, become the leading family of Hum in the 1330s.<ref name="Fine 267">Fine (The Late Medieval Balkans – 1994), pp. 267.</ref> Because of the war in 1327-1328 between Serbia and Dubrovnik, Bosnian lordship of inner Hum and the war in Macedonia, ] sold ] and ] to Dubrovnik, and turned to the east to acquire all of Macedonia.<ref name="Fine 267"/> | |||

| By 1325, the ] had emerged as strongest in Hum.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=266}} Probably at their highest point they ruled from ] River to the town of ].{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=266}} Though nominal vassals of Serbia, the Branivojević family attacked Serbian interests and other local nobles of Hum, who in 1326 turned against Serbia and Branivojević family.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=266}} The Hum nobles approached to ], the ban of Bosnia, who then annexed most of Hum.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=266}} The ] as vassals of Bosnian Ban, become the leading family of Hum in the 1330s.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=267}} Because of the war in 1327-1328 between Serbia and Dubrovnik, Bosnian lordship of inner Hum and the war in Macedonia, ] sold ] and ] to Dubrovnik, and turned to the east to acquire all of Macedonia.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=267}} | |||

| The region was overwhelmed by the ] from Bosnia in 1322-1326. By the mid-14th century, Bosnia apparently reached a peak under Ban ] who came into power in 1353.{{Citation needed|date=November 2010}} | |||

| The region was overwhelmed by the ] from Bosnia in 1322–1326. By the mid-14th century, Bosnia apparently reached a peak under Ban ] who came into power in 1353.{{Citation needed|date=November 2010}} | |||

| ===15th century=== | ===15th century=== | ||

| {{Further|Herzegovina}}]''s in the ] around 1412]] | |||

| In the beginning of the 15th century, ] ruled over the western Hum, and ] ruled over its eastern part, while the Neretva river remain a border between their possessions. |

In the beginning of the 15th century, ] ruled over the western Hum, and ] ruled over its eastern part, while the Neretva river remain a border between their possessions.{{sfn|Zlatar|2007|p=555}} | ||

| The territory on the right bank of the Lower Neretva was at the time controlled by Kosača vassals, a local clan and magnates of ].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Korać |first=Dijana |date=December 2007 |title=Vjerske prilike na području knezova Jurjevića – Vlatkovića |url=http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=42249 |journal=Radovi Zavod Za Povijesne Znanosti Hazu U Zaru |language=sh |location=Zadar |publisher=Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts |pages=221–237 |issn=1330-0474 |access-date=2012-07-09 |number=49}}</ref> | |||

| Bosnian regional lord ] |

Bosnian regional lord ] ruled over Zahumlje, or Humska zemlja as it was called at this point. In 1448 he assumed the title ''herzog'' and styled himself ''Herzog of Hum and the Coast, Grand Duke of Bosnia, Knyaz of Drina, and the rest,''{{sfn|Vego|1982|p=48}}{{sfn|Ćirković|1964a|p=106}} and since 1450, ''Herzog of Saint Sava, Lord of Hum, Grand Duke of Bosnia, Knyaz of Drina, and the rest''.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=578}} This "Saint Sava" part of the title had considerable public relations value, because ] relics were consider miracle-working by people of all Christian faiths.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=578}} Stjepan's title will prompt the ] to start calling ''Humska zemlja'' by using using the possessive form of the noun ''Herceg'', ''Herceg'''s land(s) (]), which remains a long-lasting legacy in the name of Bosnia and Herzegovina to this day.<ref name="Vego 1982 48">{{harvnb|Vego|1982|p=48}}: "Tako se pojam Humska zemlja postepeno gubi da ustupi mjesto novom imenu zemlje hercega Stjepana — Hercegovini."</ref>{{sfn|Vego|1982|p=48}}{{sfn|Ćirković|1964a|p=272}} | ||

| In 1451 he attacked Dubrovnik, and laid siege to the city.<ref name="Viator388–389">Viator (1978), pp. 388–389.</ref> He had earlier been made a Ragusan nobleman and, consequently, the Ragusan government now proclaimed him a traitor.<ref name="Viator388–389"/> A reward of 15,000 ]s, a palace in Dubrovnik worth 2,000 ducats, and an annual income of 300 ducats was offered to anyone who would kill him, along with the promise of hereditary Ragusan nobility which also helped hold this promise to whoever did the deed.<ref name="Viator388–389"/> Stjepan was so scared by the threat that he finally raised the siege.<ref name="Viator388–389"/> | In 1451 he attacked Dubrovnik, and laid siege to the city.<ref name="Viator388–389">Viator (1978), pp. 388–389.</ref> He had earlier been made a Ragusan nobleman and, consequently, the Ragusan government now proclaimed him a traitor.<ref name="Viator388–389"/> A reward of 15,000 ]s, a palace in Dubrovnik worth 2,000 ducats, and an annual income of 300 ducats was offered to anyone who would kill him, along with the promise of hereditary Ragusan nobility which also helped hold this promise to whoever did the deed.<ref name="Viator388–389"/> Stjepan was so scared by the threat that he finally raised the siege.<ref name="Viator388–389"/> | ||

| Line 110: | Line 142: | ||

| ===12th–13th centuries=== | ===12th–13th centuries=== | ||

| Most of Hum's territory was inhabited by ] |

Most of Hum's territory was inhabited by ],<ref name="Fine-2010-When Ethnicity-pp.94-98">{{cite book |last1=Fine |first1=John V. A. (Jr ) |title=When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans: A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods |date=5 February 2010 |publisher=University of Michigan Press |isbn=978-0-472-02560-2 |pages=94–98 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wEF5oN5erE0C&q=when+ethnicity+did+not+matter+in+the+balkans |access-date=21 July 2021 |language=en}}</ref> and ], and belonged to the ] after the ].{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=20}} Hum's coastal region, including its capital ], had a mixed population of ]s and Orthodox.{{sfn|Fine|1975|p=114}}{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=20}} | ||

| ===14th–15th centuries=== | ===14th–15th centuries=== | ||

| In contrast to Bosnia, where Roman Catholicism and |

In contrast to Bosnia, where Roman Catholicism and ] were firmly established, eastern parts of Hum was mostly Orthodox, from 13th century and the rise of Nemanjići.{{sfn|Velikonja|2003|p=38}} In the 14th- and 15th centuries, there was an influx of settlers from the '']'' of ], around forts Klobuk, Ledenica and Rudina, and the ''Hum lands'' around ] and ], to ]. The people from Hum were mostly girls from Gacko, who took up working as servants to wealthy families.{{sfn|Тошић|2005|p=221-227}} | ||

| In the 14th- and 15th centuries, there was an influx of settlers from the oblasts of ] (the region around forts Klobuk Ledenica and Rudina) and the ''Hum lands'' (] and ]) to ]. The people from Hum were mostly girls from Gacko, who took up working as servants to wealthy families.<ref>Tošić, Đuro. {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120317181734/http://scindeks-clanci.nb.rs/data/pdf/0350-2112/2005/0350-21120516221T.pdf |date=2012-03-17 }}, work in ''Istraživanja'', 2005, br. 16, str. 221-227.</ref> | |||

| ==List of rulers== | ==List of rulers== | ||

| Line 125: | Line 155: | ||

| |} | |} | ||

| * ], independent Slavic ruler of Zahumlje, Prince of Zahumlje |

* ], independent Slavic ruler of Zahumlje, Prince of Zahumlje 910–940{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=160}} | ||

| * ], ] |

* ], ] 969–997{{sfn|Thomas of Split|2006|p=60–61}}{{Better source needed|date=December 2015}} | ||

| * ], |

* ], Prince of Travunia and Zachlumia (as a part of Duklja) 1000–1018 | ||

| * Part of ]: 1018–1039 | |||

| * ], ] 969-997<ref name="Archdeacon 60–61"/>{{better source|date=December 2015}} | |||

| * ], Prince of |

* ], Prince of Hum 1039–1054 | ||

| * ], Prince, and King of Duklja 1054–1081 | |||

| * Part of ]: 1018-1039 | |||

| * ], |

* ], King of Duklja 1081–1101 | ||

| * ], |

* ], King of Duklja c. 1103–1113 | ||

| * ] |

* ], King of Duklja c. 1113–1118 and 1125–1131 | ||

| * ] |

* ], Duke of Zahumlje 1149–1162 | ||

| * ] |

* ] Prince of Zahumlje 1162–1190 | ||

| * ], Prince of Rascia 1145-1149 | |||

| * ], Duke of Zahumlje 1149-1162 | |||

| * ] Prince of Zahumlje 1162-1190 | |||

| * ] of ] 1190–1192 ruling in the name of ] | * ] of ] 1190–1192 ruling in the name of ] | ||

| * ] Prince of Zahumlje 1192 | * ] Prince of Zahumlje 1192 | ||

| * ] Prince of Zahumlje |

* ] Prince of Zahumlje 1192–1196 (He married a daughter of ] Berthold von Meran, ] of ]) | ||

| * To Hungary 1198–1199 |

* To Hungary 1198–1199{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=102}} | ||

| * ], son of Miroslav, ] of Zahumlje |

* ], son of Miroslav, ] of Zahumlje 1196–1216 and a ] of the city of ] 1222–1225. | ||

| * In 1216 Stephen the First-Crowned divided Hum: | * In 1216 Stephen the First-Crowned divided Hum: | ||

| **Mainland of Zachlumia: | **Mainland of Zachlumia: | ||

| ***], Prince of Serbia and Zahumlje |

***], Prince of Serbia and Zahumlje 1216–1228 | ||

| ***], son of Toljen, ] of Upper Zahumlje |

***], son of Toljen, ] of Upper Zahumlje 1228–1239 | ||

| **Coastal Zachlumia: | **Coastal Zachlumia: | ||

| ***], son of Miroslav, Prince of the Seaside and ] of Southern Zahumlje |

***], son of Miroslav, Prince of the Seaside and ] of Southern Zahumlje 1216–1239 | ||

| * Union of Zachlumia: | * Union of Zachlumia: | ||

| * ], |

* ], 1239–1250 | ||

| * ], ] and ] 1249–1252 (brothers, sons of Andrew) | * ], ] and ] 1249–1252 (brothers, sons of Andrew) | ||

| * ] and ] |

* ] and ] 1252–1268 | ||

| * ] |

* ] 1268–1280 | ||

| * ] 1280–1299 | * ] 1280–1299 | ||

| * ], a Croatian noble and ] from |

* ], a Croatian noble and ] from 1299 to 1304<ref name="građevinar">{{cite journal | url=http://www.casopis-gradjevinar.hr/dokumenti/200609/7.pdf | title=Ranokršćanske i predromaničke crkve u Stonu | trans-title=Early Christian and pre-romanesque churches in Ston | journal=Građevinar | publisher=Croatian Society of Civil Engineers | location=Zagreb | year=2006 | volume=58 | pages=757–766 | language=sh | access-date=2011-02-18 | archive-date=2011-07-21 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110721095455/http://www.casopis-gradjevinar.hr/dokumenti/200609/7.pdf | url-status=dead }}</ref> | ||

| * ], a ] and ] from |

* ], a ] and ] from 1304 to 1312<ref name="građevinar"/> | ||

| * ], ''"Ban the Croats and Bosnia and general lord of Hum country"'' 1312–1322 |

* ], ''"Ban the Croats and Bosnia and general lord of Hum country"'' 1312–1322{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=258}} | ||

| * ], ] of Zahumlje |

* ], ] of Zahumlje 1322–1326. Son of Bogdan I (or Radoslav). He married Katarina ] in 1338 | ||

| * ], a Bosnian Ban from |

* ], a Bosnian Ban from 1326 to 1353 | ||

| * ], the first Bosnian King 1353–1391 | * ], the first Bosnian King 1353–1391 | ||

| * ] |

* ] 1391–1395 | ||

| * ] |

* ] 1395–1398 | ||

| * ] |

* ] 1398– 1404{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=111}} | ||

| * ] |

* ] 1404–1409 | ||

| * ] (again) 1409–1418 |

* ] (again) 1409–1418{{sfn|Runciman|1982|p=111}} | ||

| * ], Grand Duke of Hum from |

* ], Grand Duke of Hum from 1418 to 1435 | ||

| * ] (1435–1466) was |

* ] (1435–1466) was Bosnian noble. In 1448. changed his title from "Vojvode of Bosnia" into "Herceg of Hum and the Coast", and from 1449 into "Herceg of ]" . | ||

| * ] from 1466 to 1481 | * ] from 1466 to 1481 | ||

| ==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| The honorific title '' |

The historical name of the region is officially represented in the name of the ] of the ]. Also, the honorific title ''Grand ] (Duke) of Zahumlije'' has been granted at times to junior members of the ] dynasty that ruled in ] until 1918. The last grand duke of Zahumlije was ], who died in 1932.<ref></ref> | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 189: | Line 213: | ||

| === Bibliography === | === Bibliography === | ||

| {{ |

{{refbegin|2}} | ||

| * {{Cite book |

* {{Cite book|last=Bataković|first=Dušan T.|author-link=Dušan T. Bataković|title=The Serbs of Bosnia & Herzegovina: History and Politics|date=1996|location=Paris|publisher=Dialogue|isbn=9782911527104|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wB-5AAAAIAAJ}} | ||

| * {{Cite book |last=Ćirković |first=Sima |author-link=Sima Ćirković |title=Herceg Stefan Vukčić-Kosača i njegovo doba |trans-title=Herceg Stefan Vukčić-Kosača and his time |oclc=4864621 |publisher=Naučno delo SANU |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NI8OAQAAIAAJ |year=1964a |language=sr}} | |||

| * {{cite book | author=Thomas of Split | authorlink1=Thomas the Archdeacon | title=History of the Bishops of Salona and Split – Historia Salonitanorum atque Spalatinorum pontificum | publisher=Central European University Press | location=Budapest | year=2006 | language=Latin, English | isbn= 978-963-7326-59-2}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Ćirković |first=Sima |author-link=Sima Ćirković |title=Историја средњовековне босанске државе |trans-title=History of the medieval Bosnian state |oclc=494551997 |publisher=Srpska književna zadruga |year=1964 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A2nrswEACAAJ |language=sr}} | |||

| * {{cite book | author=] | authorlink= | url= | title=] | editor-first=Gy. | editor-last=Moravcsik | others=Translated by R.J.H. Jenkins | edition=Rev. | location=Washington | year=1967 | publisher=Dumbarton Oaks | isbn= 978-0-88402-021-9}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |

* {{Cite book|last=Ćirković|first=Sima|author-link=Sima Ćirković|year=2004|title=The Serbs|location=Malden|publisher=Blackwell Publishing|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ki1icLbr_QQC|isbn=9780631204718}} | ||

| * {{Cite book|author=Thomas of Split|author-link=Thomas the Archdeacon |editor=Karbić, Damir |editor2=Matijević Sokol, Mirjana |editor3=Perić, Olga |editor4=Sweeney, James Ross|title=History of the Bishops of Salona and Split: Historia salonitanorum atque spalatinorum pontificum|year=2006|location=Budapest|publisher=Central European University Press|isbn=9789637326592|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=B6xNIF-9PmgC}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Fine | first=John Van Antwerp | title=The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century | publisher=The University of Michigan Press | location=Michigan | year=1991 | isbn=0-472-08149-7}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|editor-last=Moravcsik|editor-first=Gyula|editor-link=Gyula Moravcsik|title=Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio|year=1967|orig-year=1949|edition=2nd revised|location=Washington D.C.|publisher=Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies|isbn=9780884020219|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3al15wpFWiMC}} | |||

| * {{cite book | first = John Van Antwerp | last = Fine | authorlink = John Van Antwerp Fine | title = The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest | publisher = University of Michigan Press | location = Ann Arbor | year = 1994 | isbn = 978-0-472-08260-5 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Hh0Bu8C66TsC | ref=harv}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last1=Dvornik |first1=F. |last2=Jenkins |first2=R. J. H. |last3=Lewis |first3=B. |last4=Moravcsik |first4=Gy. |last5=Obolensky |first5=D. |last6=Runciman |first6=S. |editor=P. J. H. Jenkins|title=De Administrando Imperio: Volume II. Commentary|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DWVxvgAACAAJ|year=1962|publisher=University of London: The Athlone Press}} | |||

| * ], ''Chronicon Venetum'', ed. {{Cite book |author=G. H. Pertz |title=Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores 7 |pages=1-36: 22-3 |url=http://bsbdmgh.bsb.lrz-muenchen.de/dmgh_new/app/web?action=loadBook&bookId=00001080 |year=1846 |location=Hanover |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110719060404/http://bsbdmgh.bsb.lrz-muenchen.de/dmgh_new/app/web?action=loadBook&bookId=00001080 |archivedate=2011-07-19 |df= }} A later edition is that by G. Monticolo (1890), Rome: Forzani. The relevant passage is also found in {{Cite book|first=F. |last=Rački |year=1877 |title=Documenta historiae chroaticae periodum antiquam illustrantia |location=Zagreb |pages=388 (no. 197.1 )|url=https://archive.org/details/documentahistor00ragoog}} | |||

| * {{ |

* {{Cite book|last=Dzino|first=Danijel|title=Early Medieval Hum and Bosnia, ca. 450-1200: Beyond Myths|year=2023|publisher=Taylor & Francis|isbn=9781000893434|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=teS6EAAAQBAJ}} | ||

| * {{ |

* {{Cite book|last=Curta|first=Florin|author-link=Florin Curta|title=Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250|year=2006|location=Cambridge|publisher=Cambridge University Press|url=https://archive.org/details/southeasterneuro0000curt|url-access=registration}} | ||

| * {{Cite book|last=Fine|first=John Van Antwerp Jr.|author-link=John Van Antwerp Fine Jr.|title=The Bosnian Church: A New Interpretation: A Study of the Bosnian Church and Its Place in State and Society from the 13th to the 15th Centuries|date=1975|location=Boulder|publisher=East European Quarterly|isbn=9780914710035|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8sDYAAAAMAAJ}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Omrčanin |first=Ivo |title=Military history of Croatia |year=1984 |location= |publisher=Dorrance |isbn= 978-0-8059-2893-8}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Fine|first=John Van Antwerp Jr.|author-link=John Van Antwerp Fine Jr.|title=The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century|year=1991|orig-year=1983|location=Ann Arbor, Michigan|publisher=University of Michigan Press|isbn=0472081497|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Y0NBxG9Id58C}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Rački | first=Franjo | authorlink=Franjo Rački | title=Odlomci iz državnoga práva hrvatskoga za narodne dynastie | publisher=F. Klemma | location= | year=1861 | language=Croatian | isbn=}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Fine|first=John Van Antwerp Jr.|author-link=John Van Antwerp Fine Jr.|title=The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest|year=1994|orig-year=1987|location=Ann Arbor, Michigan|publisher=University of Michigan Press|isbn=0472082604|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LvVbRrH1QBgC}} | |||

| * {{cite journal | last=Ross | first=James Bruce | jstor=2854596 | title=Two Neglected Paladins of Charlemagne: Erich of Friuli and Gerold of Bavaria | journal=] | publisher=] | location=Cambridge, Massachusetts |date=April 1945 | volume=20 | issue=2 | pages=212–235 | issn=0038-7134 | doi=10.2307/2854596}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Fine|first=John Van Antwerp Jr.|author-link=John Van Antwerp Fine Jr.|title=When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans: A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods|year=2005|location=Ann Arbor, Michigan|publisher=University of Michigan Press|isbn=0472025600|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wEF5oN5erE0C}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Runciman | first=Steven | title=The medieval Manichee: a study of the Christian dualist heresy | publisher=Cambridge University Press | location= | year=1982 | isbn= 978-0-521-28926-9}} | |||

| * {{Cite book| |

* {{Cite book|last=Fleming|first=Thomas|author-link=Thomas Fleming (political writer)|year=2002|title=Montenegro: The Divided Land|publisher=Chronicles Press|location=Rockford, Illinois|isbn=9780961936495|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VaMtAQAAIAAJ}} | ||

| * {{ |

* {{Cite book|last=Hupchick|first=Dennis P.|year=2002|title=The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism|location=New York|publisher=Palgrave|isbn=9780312217365|url=https://archive.org/details/balkansfromconst00hupc_0|url-access=registration}} | ||

| * {{ |

* {{Cite book|last=Hupchick|first=Dennis P.|year=2017|title=The Bulgarian-Byzantine Wars for Early Medieval Balkan Hegemony: Silver-Lined Skulls and Blinded Armies|location=New York|publisher=Springer|isbn=9783319562063|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Wa4sDwAAQBAJ}} | ||

| * {{Cite journal|last=Janković|first=Đorđe|title=The Slavs in the 6th Century North Illyricum|journal=Гласник Српског археолошког друштва|year=2004|volume=20|pages=39–61|url=http://www.rastko.rs/arheologija/delo/13047}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|ref=harv|last=Velikonja|first=Mitja|title=Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina|year=2003|location=College Station|publisher=Texas A&M University Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rqjLgtYDKQ0C}} | |||

| * ], ''Chronicon Venetum'', ed. {{Cite book |author=G. H. Pertz |title=Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores 7 |pages=1–36: 22–3 |url=http://bsbdmgh.bsb.lrz-muenchen.de/dmgh_new/app/web?action=loadBook&bookId=00001080 |year=1846 |location=Hanover |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110719060404/http://bsbdmgh.bsb.lrz-muenchen.de/dmgh_new/app/web?action=loadBook&bookId=00001080 |archive-date=2011-07-19 }} A later edition is that by G. Monticolo (1890), Rome: Forzani. The relevant passage is also found in {{Cite book|first=F. |last=Rački |year=1877 |title=Documenta historiae chroaticae periodum antiquam illustrantia |location=Zagreb |pages= (no. 197.1 )|publisher=Zagrabiae, Sumptibus Academiae Scientiarum et Artium |url=https://archive.org/details/documentahistor00ragoog}} | |||

| * {{cite book | first= | last=Viator | url=https://books.google.com/?id=v9swtfALoisC&pg=PA388&dq=Stjepan+Vuk%C4%8Di%C4%87+Kosa%C4%8Da&cd=1#v=onepage&q= | title=Medieval and Renaissance Studies | publisher=University of California Press | year=1978 | isbn= 978-0-520-03608-6}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|url=https://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=11822|journal=Historical Contributions|publisher=Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts|location=Zagreb, Croatia|title=Šubići Bribirski do gubitka nasljedne banske časti (1322.)|trans-title=The Šubići of Bribir until the Loss of the Hereditary Position of the Croatian Ban (1322)|volume=22|year=2004|first=Damir|last=Karbić|language=hr|pages=1–26}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|title=The Entry of the Slavs into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs |first=A. P. |last=Vlasto |year=1970 |location=Cambridge |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn= 978-0-521-07459-9}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Luttwak|first=Edward N.|title=The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire|year=2009|publisher=Harvard University Press|isbn=9780674035195|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cUVJKJejPY8C}} | |||

| * {{cite book | first=Zdenko | last=Zlatar | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ltRWy32dG7oC&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+poetics+of+Slavdom:+the+mythopoeic+foundations+of+Yugoslavia#v=onepage&q&f=false | title=The poetics of Slavdom: the mythopoeic foundations of Yugoslavia | publisher=Peter Lang | year=2007 | isbn= 978-0-8204-8135-7}} | |||

| * {{cite book | first=H.T. | last=Norris | year=1993 | title=Islam in the Balkans: religion and society between Europe and the Arab world | publisher=University of South Carolina Press | isbn=978-0-87249-977-5 | url-access=registration | url=https://archive.org/details/islaminbalkansre00norr }} | |||

| * {{Cite book|ref=harv|last=Живковић|first=Тибор|year=2002|title=Јужни Словени под византијском влашћу 600-1025 (South Slavs under the Byzantine Rule 600-1025)|url=https://books.google.rs/books?id=oE-gAAAAMAAJ|location=Београд|publisher=Историјски институт САНУ, Службени гласник}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |

* {{Cite book|last=Omrčanin|first=Ivo|title=Military History of Croatia|year=1984|publisher=Dorrance|isbn=9780805928938|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aUO5AAAAIAAJ}} | ||

| * {{Cite book|last=Rački|first=Franjo|author-link=Franjo Rački|title=Odlomci iz državnoga práva hrvatskoga za narodne dynastie|year=1861|location=Beč|publisher=Klemm|url=https://archive.org/details/odlomciizdravno00ragoog}} | |||

| {{colend}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal|last=Ross|first=James Bruce|title=Two Neglected Paladins of Charlemagne: Erich of Friuli and Gerold of Bavaria|journal=Speculum|year=1945|volume=20|issue=2|pages=212–235|doi=10.2307/2854596|jstor=2854596|s2cid=163300685}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Runciman|first=Steven|author-link=Steven Runciman|title=The Medieval Manichee: A Study of the Christian Dualist Heresy|year=1982|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=9780521289269|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=d1LGB7u5iD0C}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Runciman|first=Steven|author-link=Steven Runciman|title=The Emperor Romanus Lecapenus and His Reign: A Study of Tenth-Century Byzantium|year=1988|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=9780521357227|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XHVzWN6gqxQC}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|editor-last=Samardžić|editor-first1=Radovan|editor-link1=Radovan Samardžić|editor-last2=Duškov|editor-first2=Milan|title=Serbs in European Civilization|year=1993|location=Belgrade|publisher=Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies|isbn=9788675830153|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=O3MtAQAAIAAJ}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last1=Sedlar|first1=Jean W.|title=East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500|year=1994|location=Seattle|publisher=University of Washington Press|isbn=9780295800646|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4NYTCgAAQBAJ}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Stephenson|first=Paul|title=The Legend of Basil the Bulgar-Slayer|year=2003|location=Cambridge|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=9780521815307|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Z0PmrXKnczUC}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Stephenson|first=Paul|title=Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900–1204|year=2004|location=Cambridge|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=9780521770170|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ILiOI0UgxHoC}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Stoianovich | first=Traian | title=Balkan worlds: the first and last Europe | publisher=M.E. Sharpe | year=1994 | isbn= 978-1-56324-033-1}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Velikonja|first=Mitja|title=Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina|year=2003|location=College Station|publisher=Texas A&M University Press|isbn=9781585442263|url=https://archive.org/details/religiousseparat0000veli|url-access=registration}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Viator | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=v9swtfALoisC&q=Stjepan+Vuk%C4%8Di%C4%87+Kosa%C4%8Da&pg=PA388 | title=Medieval and Renaissance Studies | publisher=University of California Press | year=1978 | isbn= 978-0-520-03608-6}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Vlasto|first=Alexis P.|author-link=Alexis P. Vlasto|title=The Entry of the Slavs into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs|year=1970|location=Cambridge|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=9780521074599|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fpVOAAAAIAAJ}} | |||

| * {{cite book | first=Zdenko | last=Zlatar | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ltRWy32dG7oC&q=The+poetics+of+Slavdom:+the+mythopoeic+foundations+of+Yugoslavia | title=The poetics of Slavdom: the mythopoeic foundations of Yugoslavia | publisher=Peter Lang | year=2007 | isbn= 978-0-8204-8135-7}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Ostrogorsky|first=George|author-link=George Ostrogorsky|year=1956|title=History of the Byzantine State|location=Oxford|publisher=Basil Blackwell|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Bt0_AAAAYAAJ}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal|last=Тошић|first=Ђуро|title=Требињци и Захумљани у средњовјековном Котору|journal=Истраживања: Филозофски факултет у Новом Саду|year=2005|volume=16|pages=221–227}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Klaić|first=Nada|author-link=Nada Klaić|title=Srednjovjekovna Bosna: Politički položaj bosanskih vladara do Tvrtkove krunidbe (1377. g.)|year=1989|location=Zagreb|publisher=Grafički zavod Hrvatske|isbn=9788639901042|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fm5pAAAAMAAJ}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|editor-last=Шишић|editor-first=Фердо|editor-link=Ferdo Šišić|title=Летопис Попа Дукљанина|year=1928|location=Београд-Загреб|publisher=Српска краљевска академија|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HXwCSCgxTlcC}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Кунчер|first=Драгана|year=2009|title=Gesta Regum Sclavorum|volume=1|location=Београд-Никшић|publisher=Историјски институт, Манастир Острог}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Živković|first=Tibor|author-link=Tibor Živković|year=2006|title=Портрети српских владара: IX-XII век|trans-title=Portraits of Serbian Rulers: IX-XII Century|language=sr|location=Београд|publisher=Завод за уџбенике и наставна средства|isbn=9788617137548|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=d-KTAAAACAAJ}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Живковић|first=Тибор|author-link=Tibor Živković|year=2009|title=Gesta Regum Sclavorum|volume=2|location=Београд-Никшић|publisher=Историјски институт, Манастир Острог}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Živković|first=Tibor|author-link=Tibor Živković|title=Forging unity: The South Slavs between East and West 550-1150|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JlIsAQAAIAAJ|year=2008|location=Belgrade|publisher=The Institute of History, Čigoja štampa|isbn=9788675585732}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal|last=Živković|first=Tibor|author-link=Tibor Živković|title=Constantine Porphyrogenitus' Source on the Earliest History of the Croats and Serbs|journal=Radovi Zavoda Za Hrvatsku Povijest U Zagrebu|year=2010|volume=42|pages=117–131|url=https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/94923}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal|last=Živković|first=Tibor|author-link=Tibor Živković|title=On the Baptism of the Serbs and Croats in the Time of Basil I (867–886)|journal=Studia Slavica et Balcanica Petropolitana|year=2013a|issue=1|pages=33–53|url=http://slavica-petropolitana.spbu.ru/files/2013_1/Zivkovic.pdf}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Živković|first=Tibor|author-link=Tibor Živković|chapter=The Urban Landcape [sic] of Early Medieval Slavic Principalities in the Territories of the Former Praefectura Illyricum and in the Province of Dalmatia (ca. 610-950)|title=The World of the Slavs: Studies of the East, West and South Slavs: Civitas, Oppidas, Villas and Archeological Evidence (7th to 11th Centuries AD)|year=2013b|location=Belgrade|publisher=The Institute for History|pages=15–36|isbn=9788677431044|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pLJCCwAAQBAJ}} | |||

| *{{Cite book |last=Malcolm |first=Noel |author-link=Noel Malcolm |title=Povijest Bosne : kratki pregled |url= https://katalog.kgz.hr/pagesResults/bibliografskiZapis.aspx?¤tPage=1&searchById=30&sort=0&spid0=30&spv0=Bosna+i+Hercegovina+-+povijest+-+do+20.st.&selectedId=951113056 |year=1995 |publisher= Erasmus Gilda : Novi Liber |isbn=953-6045-03-6}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Vego |first1=Marko |title=Postanak srednjovjekovne bosanske države |trans-title=The becoming of the medieval Bosnian state |oclc=461824314 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7sFpAAAAMAAJ&q=Stjepan+Vuk%C4%8Di%C4%87 |publisher=Svjetlost |place=Sarajevo |year=1982 |language=sh}} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Commons category|Zahumlje}} | |||

| * {{cite web |last=Marek |first=Miroslav |url=http://genealogy.euweb.cz/balkan/balkan5.html |title= balkan/balkan5.html<!-- Bot generated title --> |publisher=genealogy.euweb.cz}} | |||

| * http://worldroots.com/brigitte/theroff/balkan.htm | |||

| {{Slavic ethnic groups (VII-XII century)}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Croatia topics}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Serbian states}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 22:05, 9 December 2024

Medieval Balkan principality| Principality of ZachlumiaЗахумље Zahumlje | |||||||||||