| Revision as of 04:52, 26 August 2018 editBennv123 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers40,720 edits Undid revision 856571069 by 172.92.208.206 (talk) sorry but this section is only for individuals with their own Misplaced Pages articleTag: Undo← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 13:49, 22 January 2025 edit undoJJMC89 bot III (talk | contribs)Bots, Administrators3,752,490 editsm Moving Category:April 1942 events to Category:April 1942 per Misplaced Pages:Categories for discussion/Log/2025 January 14 | ||

| (520 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1942 Japanese war crime in the Philippines}} | |||

| {{Use Philippine English|date=April 2023}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=April 2019}} | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | {{Infobox military conflict | ||

| | conflict = Bataan Death March | | conflict = Bataan Death March | ||

| | partof = the ], ] | | partof = the ], ] | ||

| | image = File:Photograph of American Prisoners Using Improvised Litters to Carry Comrades, 05-1942 - NARA - 535564.jpg | |||

| | image = Ww2 131.jpg | |||

| | image_size = 300 | | image_size = 300 | ||

| | caption = A burial detail of American and Filipino prisoners of war uses improvised litters to carry fallen comrades at ], Capas, Tarlac, 1942, following the Bataan Death March. | | caption = A burial detail of American and Filipino prisoners of war uses improvised litters to carry fallen comrades at ], Capas, Tarlac, 1942, following the Bataan Death March. | ||

| | date = |

| date = 9–17 April 1942 | ||

| | place = ] and ] to ], ], Philippines | | place = ] and ] to ], ], Philippines | ||

| | result = | | result = | ||

| | casualties1 = |

| casualties1 = {{center|Exact figures are unknown. Estimates range from 5,500 to 18,650 ] deaths.}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Bataan Death March'''{{Efn|{{langx|fil|Martsa ng Kamatayan sa Bataan}}; {{langx|es|Marcha fatal de Bataán}}; {{langx|pam|Martsa ning Kematayan king Bataan}}; {{langx|ilo|Bataan Marso ti Ipapatay}}; {{langx|pag|Panagmartsa na Patey ed Bataan}}; {{langx|ja|バターン死の行進|translit=Batān Shi no Kōshin}}}} was the forcible transfer by the ] of around 72,000 to 78,000<ref>{{Cite web |date=2017-04-30 |title=The Bataan Death March |url=https://origins.osu.edu/milestones/april-2017-bataan-death-march |access-date=2025-01-11 |website=origins.osu.edu |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Masaharu Homma and Japanese Atrocities |url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/bataan-masaharu-homma-and-japanese-atrocities/ |access-date=2025-01-11 |website=] |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |title=Bataan Death March |url=https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/Visit/Museum-Exhibits/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/196797/bataan-death-march/ |archive-url=http://web.archive.org/web/20241227234944/https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/Visit/Museum-Exhibits/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/196797/bataan-death-march/ |archive-date=2024-12-27 |access-date=2025-01-11 |work=National Museum of the United States Air Force |language=en-US}}</ref><!-- Better sources needed (e.g. other scholarly sources). Interaksyon ref claims 80,000 --> American and Filipino ] (POW) from the municipalities of ] and ] on the ] Peninsula to ] via ]. | |||

| The '''Bataan Death March''' (]: ''Martsa ng Kamatayan sa Bataan''; ]: バターン死の行進, ]: ''Batān Shi no Kōshin'') was the forcible transfer by the ] of 60,000–80,000 American and Filipino ] from Saysain Point, ] and ] to ], ], via ], where the prisoners were loaded onto trains. The transfer began on April 9, 1942, after the three-month ] in the Philippines during ]. The total distance marched from Mariveles to San Fernando and from the Capas Train Station to Camp O'Donnell is variously reported by differing sources as between {{convert|60|and|69.6|mi}}. Differing sources also report widely differing prisoner of war casualties prior to reaching Camp O'Donnell: from 5,000 to 18,000 Filipino deaths and 500 to 650 American deaths during the march. The march was characterized by severe ] and wanton killings, and was later judged by an ] ] to be a ]. | |||

| The transfer began on 9 April 1942 after the three-month ] in the Philippines during ]. The total distance marched from Mariveles to San Fernando and from the Capas Train Station to various camps was {{convert|65|mi|km}}. Sources also report widely differing prisoner of war casualties prior to reaching Camp O'Donnell: from 5,000 to 18,000 Filipino deaths and 500 to 650 American deaths during the march. | |||

| The march was characterized by severe ] and wanton killings. POWs who fell or were caught on the ground were shot. After the war, the Japanese commander, General ] and two of his officers, Major General Yoshitaka Kawane and Colonel Kurataro Hirano, were tried by United States ] for war crimes and sentenced to death on charges of failing to prevent their ]. Homma was executed in 1946, and Kawane and Hirano in 1949. | |||

| ==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| ] discusses surrender terms with Japanese officers to end the Battle of Bataan]] | |||

| ===Prelude=== | ===Prelude=== | ||

| When General ] returned to active duty, the latest revision of plans for the defense of the Philippine Islands—] (WPO-3)—was politically unrealistic, as it assumed a conflict only involving the United States and Japan, not the combined ]. However, the plan was tactically sound, and its provisions for defense were applicable under any local situation.<ref name="Morton">{{cite book |last=Morton |first=Louis |url=https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_Contents.htm |title=The Fall of the Philippines |publisher=US Army Center of Military History |year=1953 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071224161349/https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_Contents.htm |archive-date=December 24, 2007}} p.61</ref> | |||

| {{Main article|Battle of Bataan}} | |||

| When General MacArthur returned to active duty, the latest revision of plans for the defense of the Philippine Islands—called WPO-3—was politically unrealistic, assuming a conflict only involving the United States and Japan, not the combined Axis powers. However, the plan was tactically sound, and its provisions for defense were applicable under any local situation.<ref name="Morton">{{cite book |title=The Fall of the Philippines |last=Morton |first=Louis |authorlink= |coauthors= |year=1953 |publisher=US Army Center of Military History |location= |isbn= |page= |pages= |url= |accessdate=}}</ref> | |||

| Under WPO-3, the mission of the Philippine garrison was to hold the entrance to Manila Bay and deny its use to Japanese naval forces. If the enemy prevailed, the Americans were |

Under WPO-3, the mission of the Philippine ] was to hold the entrance to ] and deny its use to Japanese naval forces. If the enemy prevailed, the Americans were to hold back the Japanese advance while withdrawing to the ] Peninsula, which was recognized as the key to the control of Manila Bay. It was to be defended to the "last extremity".<ref>{{cite book |last=Morton |first=Louis |url=https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_Contents.htm |title=The Fall of the Philippines |publisher=US Army Center of Military History |year=1953 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071224161349/https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_Contents.htm |archive-date=December 24, 2007}} p.62</ref> MacArthur assumed command of the ] army in July 1941 and rejected WPO-3 as defeatist, preferring a more aggressive course of action.<ref name=Murphy>{{cite book |title=Inside the Bataan Death March: Defeat, Travail and Memory |last=Murphy |first=Kevin C. |year=2014 |publisher=McFarland |location=Jefferson, North Carolina |isbn=978-0-7864-9681-5 |pages=328 }}</ref> He recommended—among other things—a coastal defense strategy that would include the entire archipelago. His recommendations were followed in the plan that was eventually approved.<ref>{{cite book |last=Morton |first=Louis |url=https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_Contents.htm |title=The Fall of the Philippines |publisher=US Army Center of Military History |year=1953 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071224161349/https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_Contents.htm |archive-date=December 24, 2007}} p.67</ref> | ||

| The main force of General ]'s 14th Army came ashore at Lingayen Gulf on the morning of 22 December. The defenders failed to hold the beaches. By the end of the day, the Japanese had secured most of their objectives and were in position to emerge onto the central plain. Late |

The main force of General ]'s ] ] on the morning of 22 December 1941. The defenders failed to hold the beaches. By the end of the day, the Japanese had secured most of their objectives and were in position to emerge onto the central plain. Late in the afternoon of 23 December General ] telephoned MacArthur's headquarters in ] and informed him that any further defense of the ] beaches was "impracticable". He requested and was given permission to withdraw behind the ]. MacArthur decided to abandon his own plan for defense and revert to WPO-3, evacuating President ], High Commissioner ], their families, and his own headquarters to ] on 24 December. A rear echelon, headed by the deputy chief of staff, Brigadier General ], remained behind in Manila to close out the headquarters and to supervise the shipment of supplies and the evacuation of the remaining troops.<ref>{{cite book |last=Morton |first=Louis |url=https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_Contents.htm |title=The Fall of the Philippines |publisher=US Army Center of Military History |year=1953 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071224161349/https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_Contents.htm |archive-date=December 24, 2007}} p.233</ref> | ||

| On |

On 26 December Manila was officially declared an ], and MacArthur's proclamation was published in the newspapers and broadcast over the radio.<ref>{{cite book |last=Morton |first=Louis |url=https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_Contents.htm |title=The Fall of the Philippines |publisher=US Army Center of Military History |year=1953 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071224161349/https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_Contents.htm |archive-date=December 24, 2007}} p.232</ref> | ||

| The ] began |

The ] began on 7 January 1942 and continued until 9 April when the ] (USAFFE) commander, Major General ], surrendered to Colonel Mootoo Nakayama of the 14th Army.<ref name=GMA /> King went against his superior's orders and told his troops to lay down their arms, accepting personal responsibility for the surrender.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web |last=Lendon |first=Brad |date=2024-04-03 |title=A double dose of hell: The Bataan Death March and what came next |url=https://www.cnn.com/travel/bataan-death-march-intl-hnk-ml-dst/index.html |access-date=2024-04-09 |website=CNN |language=en}}</ref> He made the following statement: "You men remember this. You did not surrender … you had no alternative but to obey my order."<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| === |

===Allied surrender=== | ||

| Homma and his staff encountered almost twice as many captives as his reports had estimated, creating an enormous ] challenge: the transport and movement of over 60,000 starved, sick, wounded and debilitated prisoners and over 38,000 equally weakened civilian noncombatants who had been caught up in the battle. He wanted to move the prisoners and refugees to the north to get them out of the way of Homma's final assault on Corregidor, but there was simply not enough mechanized transport for the wounded, sick, and weakened masses.<ref name=woolfe /> | |||

| == |

==Forced March== | ||

| ] | ] to ] was by rail cars.<ref>{{cite book|author=Hubbard, Preston John|title=Apocalypse Undone: My Survival of Japanese Imprisonment During World War II|publisher=Vanderbilt University Press|year=1990|isbn=978-0-8265-1401-1|page=87|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nucrbGjY_GoC&pg=PA87}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|author=Bilek, Anton (Tony)|year=2003|title=No Uncle Sam: The Forgotten of Bataan|publisher=Kent State University Press|isbn=978-0-87338-768-2|page=51|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5q3Mk6Bx0lsC&pg=PA51}}</ref>]] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] map highlighting the site of the ]]] | |||

| ] (where the Filipinos passed)]] | |||

| Following the surrender of Bataan on 9 April 1942 to the Imperial Japanese Army, prisoners were amassed in the towns of ] and ].<ref name="GMA">{{cite web |url=http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/254296/lifestyle/artandculture/ww2-historical-markers-remind-pinoys-of-bataan-s-role-on-day-of-valor |title=WW2 historical markers remind Pinoys of Bataan's role on Day of Valor |last1=Esconde |first1=Ernie B. |date=April 9, 2012 |work=GMA Network |access-date=December 5, 2016}}</ref><ref name="Falk">{{cite book|last=Falk |first=Stanley L.|title=Bataan: The March of Death|year=1962 |pages=102 |publisher=]|location=New York|oclc=1084550 |quote=On April 11th, once the surrender of the I Corps was completed, the Filipino and American troops in western Bataan began their slow assembly. From the front lines south of the Pilar-Bagac road and from the jungle slopes of the Mariveles Mountains, they straggled in disorganized groups to the West Road. Then they went either north or south, to Bagac or Mariveles, an uncoordinated mass of men and vehicles moving with little direction from the Japanese.}}</ref> They were ordered to turn over their possessions. American Lieutenant Kermit Lay recounted how this was done: | |||

| {{blockquote| | |||

| They pulled us off into a rice paddy and began shaking us down. There about a hundred of us so it took time to get to all of us. Everyone had pulled their pockets wrong side out and laid all their things out in front. They were taking jewelry and doing a lot of slapping. I laid out my New Testament. ... After the shakedown, the Japs took an officer and two enlisted men behind a rice shack and shot them. The men who had been next to them said they had Japanese souvenirs and money.<ref name=greenberger>{{cite book |title=The Bataan Death March: World War II Prisoners in the Pacific |last=Greenberger |first=Robert |year=2009 |publisher=Compass Point Books |isbn=978-0-7565-4095-1}}</ref><sup>:37</sup> | |||

| }} | |||

| ] | |||

| Word quickly spread among the prisoners to conceal or destroy any Japanese money or mementos, as their captors would assume it had been stolen from dead Japanese soldiers.<ref name=greenberger /><sup>:37</sup> American soldier Bert Bank recalls: | |||

| Following the surrender of Bataan on April 9, 1942, to the Imperial Japanese Army, prisoners were massed in Mariveles and Bagac town.<ref name=GMA>{{cite web |url=http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/254296/lifestyle/artandculture/ww2-historical-markers-remind-pinoys-of-bataan-s-role-on-day-of-valor |title=WW2 historical markers remind Pinoys of Bataan's role on Day of Valor |last1=Esconde |first1=Ernie B. |last2= |first2= |language= |trans-title=|date=April 9, 2012 |work=GMA Network |publisher= |accessdate=December 5, 2016}}</ref><ref name=Falk>{{cite book|last=Falk |first=Stanley L.|title=Bataan: The March of Death|year=1962|publisher=]|location=New York|oclc=1084550}}</ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote|text=One of the POWs had a ring on and the Japanese guard attempted to get the ring off. He couldn't get it off and he took a machete and cut the man's wrist off and when he did that, of course the man was bleeding profusely. but when I looked back I saw a Japanese guard sticking a bayonet through his stomach.<ref>{{cite web |title=Bataan Rescue: Masaharu Homma and Japanese Atrocities |url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/bataan-masaharu-homma-and-japanese-atrocities/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230602192028/https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/bataan-masaharu-homma-and-japanese-atrocities/ |archive-date=June 2, 2023 |publisher=]}}</ref>|source=}} | |||

| As the defeated defenders were massed in preparation for the march, they were ordered to turn over their possessions. American Lieutenant Kermit Lay recounted how this was done: {{quote|They pulled us off into a rice paddy and began shaking us down. There about a hundred of us so it took time to get to all of us. Everyone had pulled their pockets wrong side out and laid all their things out in front. They were taking jewelry and doing a lot of slapping. I laid out my New Testament. … After the shakedown, the Japs took an officer and two enlisted men behind a rice shack and shot them. The men who had been next to them said they had Japanese souvenirs and money.<ref name=greenberger>{{cite book |title=The Bataan Death March: World War II Prisoners in the Pacific |last=Greenberger |first=Robert |authorlink= |coauthors= |year=2009 |publisher=Compass Point Books |location= |isbn=978-0756540951 |page= |pages=96 |url= |accessdate=}}</ref>}} | |||

| Prisoners started out from Mariveles on 10 April and from Bagac on 11 April, converging in ] and heading north to the San Fernando railhead.<ref name="GMA" /> The prisoners were put in groups of 100 men each, with four Japanese guards per group.<ref name=":1" /> At the beginning, there were rare instances of kindness by Japanese officers and those Japanese soldiers who spoke English, such as the sharing of food and cigarettes and permitting personal possessions to be kept. One prisoner who'd been a star football player at Notre Dame had his class ring taken by a guard. It was later returned by a Japanese officer who attended Notre Dame rival USC, had seen him play and had admired his athletic skills. This, however, was quickly followed by unrelenting brutality, theft, and even knocking men's teeth out for gold fillings, as the common Japanese soldier had also suffered in the battle for Bataan and had nothing but disgust and hatred for his "captives" (Japan did not recognize these people as POWs).<ref name="woolfe">{{cite book |title=The Doomed Horse Soldiers of Bataan: The Incredible Stand of the 26th Cavalry | last=Woolfe | first=Raymond G. Jr. |year=2016 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield Publishers |isbn=978-1-4422-4534-1 |pages=414 }}</ref> The first atrocity—attributed to Colonel ]<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.us-japandialogueonpows.org/Nelson.htm|title=US-Japan Dialogue on POWs|website=www.us-japandialogueonpows.org|url-status=usurped|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100603215139/http://www.us-japandialogueonpows.org/Nelson.htm |archive-date=June 3, 2010 }}</ref>—occurred when approximately 350 to 400 Filipino officers and non-commissioned officers under his supervision were ] in the ] after they had surrendered.<ref name="Norman, Michael and Norman, Elizabeth" />{{page needed|date=April 2022}}<ref name="lansford-157-158">{{cite book|author= Lansford, Tom|chapter=Bataan Death March|editor=Sandler, Stanley|title=World War II in the Pacific: an encyclopedia|publisher=Taylor & Francis|year=2001|isbn=978-0-8153-1883-5|pages=157–158|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K-027Yrx12UC&pg=PA157}}</ref> Tsuji—acting against General Homma's wishes that the prisoners be transferred peacefully—had issued clandestine orders to Japanese officers to summarily execute all American "captives".<ref name="woolfe" /> Although some Japanese officers ignored the orders, others were receptive to the idea of murdering POWs.<ref>Kevin C. Murphy, ''Inside the Bataan Death March: Defeat, Travail and Memory'', pp. 29–30</ref> | |||

| Word quickly spread among the prisoners to conceal or destroy any Japanese money or mementos, as the captors assumed it had been stolen from dead Japanese soldiers.<ref name=greenberger /> | |||

| During the march, prisoners received little food or water, and many died.<ref name="Murphy" /><ref name="lansford-159-160" /> They were subjected to severe ], including beatings and torture.<ref name="Britannica">{{cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9013704/Bataan-Death-March#84289 |title=Bataan Death March. Britannica Encyclopedia Online |publisher=Britannica.com |date=April 9, 1942 |access-date=December 17, 2012}}</ref> On the march, the "sun treatment" was a common form of torture. Prisoners were forced to sit in sweltering direct sunlight without helmets or other head coverings. Anyone who asked for water was shot dead. Some men were told to strip naked or sit within sight of fresh, cool water.<ref name="greenberger" /><sup>:40</sup> Trucks drove over some of those who fell or succumbed to fatigue,<ref>{{cite book|author=Greenberger, Robert| title=The Bataan Death March: World War II Prisoners in the Pacific|date= 2009|page= 40}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Doyle, Robert C.|title=The enemy in our hands: America's treatment of enemy prisoners of war from the Revolution to the War on Terror|publisher=University Press of Kentucky|year=2010|isbn=978-0-8131-2589-3|page=xii|url=https://archive.org/details/enemyinourhandsa0000doyl|url-access=registration}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Hoyt, Eugene P.|title=Bataan: a survivor's story|publisher=University of Oklahoma Press|year=2004|isbn=978-0-8061-3582-3|page=125|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BBmpW0_6MTYC}}</ref> and "cleanup crews" killed those too weak to continue, though trucks picked up some of those too fatigued to go on. Prisoners were randomly stabbed with bayonets or beaten.<ref name="Murphy" /><ref>{{Cite book|author=Stewart, Sidney|title=Give Us This Day|url=https://archive.org/details/giveusthisday00stew|url-access=registration|publisher=]|edition=revised|isbn=978-0-393-31921-7|page=81|year=1957}}</ref> | |||

| Prisoners started out from Mariveles on April 10, and Bagac on April 11, converging in ], and heading north to the San Fernando railhead.<ref name=GMA /> At the beginning of capture there were rare instances of kindness by Japanese officers and those Japanese soldiers who spoke English, such as sharing of food and cigarettes and permitting personal possessions to be kept. This was fast followed by unrelenting brutality, theft, and even knocking men’s teeth out for gold fillings, as the common Japanese soldier had also suffered in the Battle for Bataan and had nothing but disgust and hatred for his “captives” (Japan did not recognize these people as POWs).<ref name=woolfe>{{cite book |title=The Doomed Horse Soldiers of Bataan: The Incredible Stand of the 26th Cavalry |last=Woolfe, Jr. |first=Raymond G. |authorlink= |coauthors= |year=2016 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield Publishers |location= |isbn=978-1442245341 |page= |pages=414 |url= |accessdate=}}</ref> The first atrocity—attributed to Colonel ]<ref>{{cite web|title= The Causes of the Bataan Death March Revisited |url= http://www.us-japandialogueonpows.org/Nelson.htm}}</ref>—occurred when approximately 350 to 400 Filipino officers and NCOs under his supervision were summarily executed in the ] after they had surrendered.<ref name="Norman, Michael and Norman, Elizabeth"/><ref name="lansford-157-158">{{cite book|author= Lansford, Tom|chapter=Bataan Death March|editor=Sandler, Stanley|title=World War II in the Pacific: an encyclopedia|publisher=Taylor & Francis|year=2001|isbn=978-0-8153-1883-5|pages=157–158|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K-027Yrx12UC&pg=PA157}}</ref> Tsuji—acting against General Homma's wishes that the prisoners be transferred peacefully—had issued clandestine orders to Japanese officers to summarily execute all American “captives.”<ref name=woolfe /> Though some Japanese officers ignored the orders, others were receptive to the idea of murdering POWs.<ref>"Inside the Bataan Death March: Defeat, Travail and Memory" Kevin C. Murphy p.29-30</ref> | |||

| Once the surviving prisoners arrived in ], the overcrowded conditions and poor hygiene caused ] and other diseases to spread rapidly. The Japanese did not provide the prisoners with medical care, so U.S. medical personnel tended to the sick and wounded with few or no supplies.<ref name="lansford-159-160">{{cite book|author=Lansford, Tom|chapter=Bataan Death March|editor=Sandler, Stanley|title=World War II in the Pacific: an encyclopedia|publisher=Taylor & Francis|year=2001|isbn=978-0-8153-1883-5|pages=159–60|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K-027Yrx12UC&pg=PA159}}</ref> Upon arrival at the San Fernando railhead, prisoners were stuffed into sweltering, brutally hot metal box cars for the one-hour trip to Capas, in {{convert|110|F|C|order=flip}} heat. At least 100 prisoners were pushed into each of the unventilated boxcars. The trains had no sanitation facilities, and disease continued to take a heavy toll on the prisoners. According to Staff Sergeant Alf Larson: | |||

| During the march, prisoners received little food or water, and many died.<ref name=Murphy /><ref name="lansford-159-160" /><ref name="John E. Olson">{{cite book|last1=Olson|first1=John E.|title=O'Donell: Andersonville of the Pacific|year=1985|publisher=John E. Olson|isbn=978-9996986208}}</ref> Prisoners were subjected to severe ], including being beaten and tortured.<ref name=Britannica>{{cite web|url=http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9013704/Bataan-Death-March#84289 |title=Bataan Death March. Britannica Encyclopedia Online |publisher=Britannica.com |date=1942-04-09 |accessdate=2012-12-17}}</ref> On the march, the “sun treatment” was a common form of torture. Prisoners were forced to sit in sweltering direct sunlight, without helmets or other head covering. Anyone who asked for water was shot dead. Some men were told to strip naked or sit within sight of fresh, cool water.<ref name=greenberger /> Trucks drove over some of those who fell or succumbed to fatigue,<ref>{{cite book|author=Greenberger, Robert| title=The Bataan Death March: World War II Prisoners in the Pacific|date= 2009|page= 40}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Doyle, Robert C.|title=The enemy in our hands: America's treatment of enemy prisoners of war from the Revolution to the War on Terror|publisher=University Press of Kentucky|year=2010|isbn=978-0-8131-2589-3|page=xii|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZBryc3ANF6IC&pg=PR12}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Hoyt, Eugene P.|title=Bataan: a survivor's story|publisher=University of Oklahoma Press|year=2004|isbn=978-0-8061-3582-3|page=125|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BBmpW0_6MTYC}}</ref> and "cleanup crews" put to death those too weak to continue, though some trucks picked up some of those too fatigued to continue. Some marchers were randomly stabbed by bayonets or beaten.<ref name=Murphy /><ref>* {{Cite book|author=Stewart, Sidney|title=Give Us This Day|publisher=]|edition=revised|isbn=0-393-31921-0}}</ref> The Death March was later judged by an ] ] to be a ].<ref name=Britannica /> | |||

| {{blockquote|The train consisted of six or seven World War I-era boxcars. ... They packed us in the cars like sardines, so tight you couldn't sit down. Then they shut the door. If you passed out, you couldn't fall down. If someone had to go to the toilet, you went right there where you were. It was close to summer and the weather was hot and humid, hotter than Billy Blazes! We were on the train from early morning to late afternoon without getting out. People died in the railroad cars.<ref name=greenberger /><sup>:45</sup> | |||

| Once the surviving prisoners arrived in Balanga, the overcrowded conditions and poor hygiene caused ] and other diseases to spread rapidly. The Japanese did not provide the prisoners with medical care, so U.S. medical personnel tended to the sick and wounded with few or no supplies.<ref name="lansford-159-160">{{cite book|author=Lansford, Tom|chapter=Bataan Death March|editor=Sandler, Stanley|title=World War II in the Pacific: an encyclopedia|publisher=Taylor & Francis|year=2001|isbn=978-0-8153-1883-5|pages=159–60|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K-027Yrx12UC&pg=PA159}}</ref> Upon arrival at the San Fernando railhead, prisoners were stuffed into sweltering, brutally hot metal box cars for the one-hour trip to Capas, in {{convert|110|F|C|order=flip}} heat. At least 100 prisoners were pushed into each of the trains' unventilated boxcars. The trains had no sanitation facilities, and disease continued to take a heavy toll on the prisoners. According to Staff Sergeant Alf Larson: | |||

| }} | |||

| {{quote|The train consisted of six or seven World War I-era boxcars. … They packed us in the cars like sardines, so tight you couldn’t sit down. Then they shut the door. If you passed out, you couldn’t fall down. If someone had to go to the toilet, you went right there where you were. It was close to summer and the weather was hot and humid, hotter than Billy Blazes! We were on the train from early morning to late afternoon without getting out. People died in the railroad cars.<ref name=greenberger />}} | |||

| Upon arrival at the Capas train station, they were forced to walk the final {{convert|9|mi|km |

Upon arrival at the ] train station, they were forced to walk the final {{convert|9|mi|km}} to ].<ref name="lansford-159-160" /> Even after arriving at Camp O'Donnell, the survivors of the march continued to die at rates of up to several hundred per day, which amounted to a death toll of as many as 20,000 Americans and Filipinos.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/odonnell/provost_rpt.html|title=O'Donnell Provost Marshal Report|website=www.mansell.com}}</ref> Most of the dead were buried in mass graves that the Japanese had dug behind the barbed wire surrounding the compound.<ref>{{cite book|title=The Fighting Tigers: the untold stories behind the names on the Ouachita Baptist University WWII memorial|publisher=University of Arkansas Press|year=2004|isbn=978-0-9713470-5-2|pages=106–7|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mMMSFJ0EJMMC&pg=PA106|author=Downs, William David}}</ref> Of the estimated 80,000 POWs at the march, only 54,000 made it to Camp O'Donnell.<ref name="interaksyon1">{{cite web |date=April 8, 2012 |title=Bataan Death March |url=http://interaksyon.com/bataan-deathmarch |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161220074312/http://interaksyon.com/bataan-deathmarch |archive-date=December 20, 2016 |access-date=December 5, 2016 |work=Interaksyon}}</ref> | ||

| The total distance of the march from Mariveles to San Fernando and from Capas to Camp O'Donnell |

The total distance of the march from Mariveles to San Fernando and from Capas to Camp O'Donnell is variously reported by differing sources as between {{convert|60|and|69.6|mi|km}}.<ref name=GMA /><ref name=interaksyon1 /><ref name=S&S /><ref name=msn.com>{{cite web |url=https://www.msn.com/en-ph/travel/tripideas/travel-diary-hiking-the-bataan-death-march-2015/ar-BBobvFQ |title=Hiking the Bataan Death March 2015 |last1=Ahn |first1=Tony |date=January 14, 2016 |work=MSN Lifestyle |publisher=Microsoft Network |access-date=December 5, 2016 }}{{Dead link|date=September 2018 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> The Death March was later judged by an ] ] to be a ].<ref name=Britannica /> | ||

| ===Casualty estimates=== | ===Casualty estimates=== | ||

| ] | |||

| Credible sources report widely differing prisoner of war casualties prior to reaching their destination: from 5,000 to 18,000 Filipino deaths and 500 to 650 American deaths during the march.<ref name="Norman, Michael and Norman, Elizabeth">{{Cite book|author1=Norman, Michael |author2=Norman, Elizabeth |lastauthoramp=yes |title=Tears in the Darkness|publisher=]|edition=revised|isbn=978-0374272609}}</ref><ref name="lansford-159-160" /><ref name=interaksyon1>{{cite web |url=http://interaksyon.com/bataan-deathmarch |title=Bataan Death March |last1= |first1= |last2= |first2= |language= |trans-title=|date=April 8, 2012 |work=Interaksyon |publisher= |accessdate=December 5, 2016}}</ref><ref name=S&S>{{cite web |url=http://www.stripes.com/news/american-walks-bataan-death-march-to-raise-awareness-of-philippine-involvement-1.389661 |title=American walks Bataan Death March to raise awareness of Philippine involvement |last1=Ornauer |first1=Dave |last2= |first2= |language= |trans-title=|date=January 20, 2016 |work=Stars & Stripes |publisher= |accessdate=December 5, 2016}}</ref><ref name=bataanmuseum>{{cite web |url=http://www.bataanmuseum.com/bataanhistory/ |title=Bataan History |last1= |first1= |last2= |first2= |language= |trans-title=|date= |work= |publisher=New Mexico Guard National Museum |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20161130144025/http://www.bataanmuseum.com/bataanhistory/ |archivedate=November 30, 2016 |accessdate=December 5, 2016}}</ref><ref name=herman>{{cite book |title=Douglas McArthur: American Warrior |last=Herman |first=Arthur |year=2016 |publisher=Random House Publishing Group |location= |isbn=0812994892 |url=https://books.google.com.ph/books?isbn=0812994892}}</ref><ref name=horner>{{cite book |title=World War II: The Pacific |last=Horner |first=David Murray |author2=Robert John O’Neill |year=2010 |publisher=Rosen Publishing |location= |isbn=1435891333 |url=https://books.google.com.ph/books?isbn=1435891333}}</ref><ref name=Darman>{{cite book |title=Attack on Pearl Harbor: America Enters World War II |last=Darman |first=Peter |year=2012 |publisher=Rosen Publishing |location= |isbn=1448892333 |url=https://books.google.com.ph/books?isbn=1448892333}}</ref> | |||

| In an attempt to calculate the number of deaths during the march on the basis of evidence, Stanley L. Falk takes the number of American and Filipino troops known to have been present in Bataan at the start of April, subtracts the number known to have escaped to Corregidor and the number known to have remained in the hospital at Bataan. He makes a conservative estimate of the number killed in the final days of fighting and of the number who fled into the jungle rather than surrender to the Japanese. On this basis he suggests 600 to 650 American deaths and 5,000 to 10,000 Filipino deaths.<ref>{{cite book|last=Falk |first=Stanley L.|title=Bataan: The March of Death|year=1962 |pages=197–198 |quote= |publisher=]|location=New York|oclc=1084550}}</ref> Other sources report death numbers ranging from 5,000 to 18,000 Filipino deaths and 500 to 650 American deaths during the march.<ref name="Norman, Michael and Norman, Elizabeth">{{Cite book |author1=Norman, Michael |url=https://archive.org/details/tearsindarknesst00norm |title=Tears in the Darkness |author2=Norman, Elizabeth |date=June 9, 2009 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-374-27260-9 |edition=revised |name-list-style=amp}}</ref>{{Rp|pages=413-414}}<ref name="lansford-159-160" /><ref name=S&S>{{cite web |url=http://www.stripes.com/news/american-walks-bataan-death-march-to-raise-awareness-of-philippine-involvement-1.389661 |title=American walks Bataan Death March to raise awareness of Philippine involvement |last1=Ornauer |first1=Dave |date=January 20, 2016 |work=Stars & Stripes |access-date=December 5, 2016}}</ref><ref name=bataanmuseum>{{cite web |url=http://www.bataanmuseum.com/bataanhistory/ |title=Bataan History |publisher=New Mexico Guard National Museum |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161130144025/http://www.bataanmuseum.com/bataanhistory/ |archive-date=November 30, 2016 |access-date=December 5, 2016}}</ref><ref name="herman">{{cite book |last=Herman |first=Arthur |url=https://books.google.com/books?isbn=0812994892 |title=Douglas MacArthur: American Warrior |publisher=Random House Publishing Group |year=2016 |isbn=978-0-8129-9489-6 |pages=649 |quote=He had learned how 76,000 American and Filipino prisoners had been force-marched. The 18,000 prisoners who couldn't make the Bataan death march had been either shot or beaten to death along the way.}}</ref><ref name="horner">{{cite book |last=Horner |first=David Murray |url=https://books.google.com/books?isbn=1435891333 |title=World War II: The Pacific |author2=Robert John O'Neill |publisher=Rosen Publishing |year=2010 |isbn=978-1-4358-9133-3 |pages=74, 77 |quote=Between 7,000 and 10,000 died or were killed during the "Bataan Death March" ... Somewhere between 6,000 to 18,000 POWs died or were murdered during the Death March}}</ref><ref name="Darman">{{cite book |last=Darman |first=Peter |url=https://books.google.com/books?isbn=1448892333 |title=Attack on Pearl Harbor: America Enters World War II |publisher=Rosen Publishing |year=2012 |isbn=978-1-4488-9233-4 |pages=51}}</ref> | |||

| ==Wartime public responses== | ==Wartime public responses== | ||

| Line 58: | Line 73: | ||

| ===United States=== | ===United States=== | ||

| ] newsstand, after the fall of Bataan]] | |||

| It was not until January 27, 1944, that the U.S. government informed the American public about the march, when it released sworn statements of military officers who had escaped.<ref>{{cite book|title=Matters of culture: cultural sociology in practice|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2004|isbn=978-0-521-79545-6| page=197| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8kyPuUoSFKMC&pg=PA197|author1=Friedland, Roger |author2=Mohr, John |lastauthoramp=yes }}</ref> Shortly thereafter the stories of these officers were featured in a ] article.<ref>{{cite journal|author1=McCoy, Melvin|author2=Mellnik, S.M.|author3=Kelley, Welbourn|title=Prisoners of Japan: Ten Americans Who Escaped Recently from the Philippines Report on the Atrocities Committed by the Japanese in Their Prisoner-War-Camps|journal=LIFE|date=February 7, 1944|volume=16|issue=6|pages=26–31, 96–98, 105–106, 108, 111|publisher=Time, Inc.|location=Chicago}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YFQEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA29&dq=Bataan+Death+march&hl=en&sa=X&ei=n-SVVMWlHPTasASnoYCQDw&ved=0CB8Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Bataan+Death+march&f=false|title=LIFE|first=Time|last=Inc|date=7 February 1944|publisher=Time Inc|via=Google Books}}</ref> The Bataan Death March and other Japanese actions were used to arouse fury in the United States.<ref>{{cite book |author=Jansen, Marius B. |date=2000| title=The Making of Modern Japan|page=655}}</ref> | |||

| It was not until 27 January 1944 that the U.S. government informed the American public about the march, when it released sworn statements of military officers who had escaped.<ref>{{cite book|title=Matters of culture: cultural sociology in practice|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2004|isbn=978-0-521-79545-6| page=197| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8kyPuUoSFKMC&pg=PA197|author1=Friedland, Roger |author2=Mohr, John |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> Shortly thereafter, the stories of these officers were featured in a ] article.<ref>{{cite magazine|author1=McCoy, Melvin|author2=Mellnik, S.M.|author3=Kelley, Welbourn|title=Prisoners of Japan: Ten Americans Who Escaped Recently from the Philippines Report on the Atrocities Committed by the Japanese in Their Prisoner-War-Camps|magazine=Life|date=February 7, 1944|volume=16|issue=6|pages=26–31, 96–98, 105–106, 108, 111}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YFQEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA29|title=LIFE|date=February 7, 1944|via=Google Books}}</ref> The Bataan Death March and other Japanese actions were used to arouse fury in the United States.<ref>{{cite book |author=Jansen, Marius B. |date=2000| title=The Making of Modern Japan|url=https://archive.org/details/makingofmodernja00jans |url-access=registration |page=|publisher=Cambridge, Mass. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press|isbn=9780674003347}}</ref> America would go on to avenge its defeat that occurred in the Philippines during the ] in October 1944. U.S. and Filipino forces went on to ] in January 1945, and ] in early March.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |last=History |date=Nov 9, 2009 |title=Bataan Death March |url=https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/bataan-death-march |access-date=Feb 3, 2023 |website=history.com}}</ref> | |||

| General ] made the following statement: | General ] made the following statement: | ||

| {{blockquote| | |||

| {{Quote|These brutal reprisals upon helpless victims evidence the shallow advance from savagery which the Japanese people have made. <nowiki></nowiki> We serve notice upon the Japanese military and political leaders as well as the Japanese people that the future of the Japanese race itself, depends entirely and irrevocably upon their capacity to progress beyond their aboriginal barbaric instincts.<ref>{{cite book|author=Chappell, John David|title=Before the bomb: how America approached the end of the Pacific War|publisher=University of Kentucky Press|year=1997|isbn=978-0-8131-1987-8|page=30|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3MbPjwLTt8wC&pg=PA30}}</ref>}} | |||

| These brutal reprisals upon helpless victims evidence the shallow advance from savagery which the Japanese people have made. ... We serve notice upon the Japanese military and political leaders as well as the Japanese people that the future of the Japanese race itself, depends entirely and irrevocably upon their capacity to progress beyond their aboriginal barbaric instincts.<ref>{{cite book|author=Chappell, John David|title=Before the bomb: how America approached the end of the Pacific War|publisher=University of Kentucky Press|year=1997|isbn=978-0-8131-1987-8|page=30|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3MbPjwLTt8wC&pg=PA30}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| ===Japanese=== | ===Japanese=== | ||

| In an attempt to counter the American propaganda value of the march, the Japanese had '']'' report that the prisoners were treated humanely and their death rate had to be attributed to the intransigence of the American commanders who did not surrender until the men were on the verge of death.<ref>{{cite book|author= |

In an attempt to counter the American propaganda value of the march, the Japanese had '']'' report that the prisoners were treated humanely and their death rate had to be attributed to the intransigence of the American commanders who did not surrender until the men were on the verge of death.<ref>{{cite book|author=Toland, John|author-link=John Toland (author)| title=The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945|page= 300 |publisher=Random House|location= New York |date=1970| title-link=The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945}}</ref> | ||

| ==War crimes trial== | ==War crimes trial== | ||

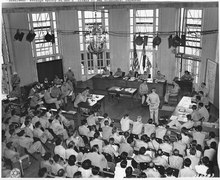

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| In September 1945, |

In September 1945, Homma was arrested by Allied troops and indicted for ]s.<ref name="sandler-420">{{cite book|chapter=Homma Masaharu (1887–1946)|editor=Sandler, Stanley|title=World War II in the Pacific: an encyclopedia|publisher=Taylor & Francis|year=2001|isbn=978-0-8153-1883-5|page=420|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K-027Yrx12UC&pg=PA420}}</ref> He was charged with 43 separate counts, but the verdict did not distinguish among them, leaving some doubt over whether he was found guilty of them all.<ref>Yuma Totani, ''Justice in Asia and the Pacific region, 1945-1952: Allied war crimes prosecutions'' (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 40–46</ref> Homma was found guilty of permitting members of his command to commit "brutal atrocities and other high crimes".<ref>{{cite book|author=Solis, Gary D.|title=The law of armed conflict: international humanitarian law in war|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2010|isbn=978-0-521-87088-7|page=384|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6FKf0ocxEPAC&pg=PA384}}</ref> The general, who had been absorbed in his efforts to capture Corregidor after the fall of Bataan, claimed in his defense that he remained ignorant of the high death toll of the death march until two months after the event.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.americanheritage.com/trial-general-homma|title=The Trial Of General Homma | AMERICAN HERITAGE|website=www.americanheritage.com}}</ref> Homma's verdict was predicated on the doctrine of '']'' but with an added liability standard, since the latter could not be rebutted.<ref>{{cite book|author=Solis, Gary D.|title=The law of armed conflict: international humanitarian law in war|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2010|isbn=978-0-521-87088-7|pages=384, 385|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6FKf0ocxEPAC&pg=PA384}}</ref> On 26 February 1946 he was sentenced to death by firing squad and was executed on 3 April outside Manila.<ref name="sandler-420" /> | ||

| Tsuji, who had directly ordered the killing of POWs, fled to China from Thailand when the war ended to escape the British authorities.<ref>''Inside the Bataan Death March: Defeat, Travail and Memory'': Kevin C. Murphy p.30-31</ref> Two of Homma's subordinates, Major General Yoshitaka Kawane and Colonel Kurataro Hirano, were prosecuted by an ] in 1948, using evidence presented at the Homma trial. They were sentenced to death by hanging and executed at ] on 12 June 1949.<ref>John L. Ginn, ''Sugamo Prison, Tokyo: an account of the trial and sentencing of Japanese war criminals in 1948, by a U.S. participant'' (Jefferson NC: McFarland, 1992), pp. 101–105.</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://bataanproject.com/provisional-tank-group/kadel-capt-richard-c/|title = Kadel, Maj. Richard C. – Bataan Project| date=May 11, 2019 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=June 11, 1949 |title=Manchester Evening Herald |url=http://www.manchesterhistory.org/News/Manchester%20Evening%20Hearld_1949-06-11.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| Also in Japan, Generals ] (later Prime Minister), ], ], ], ], and ], along with Baron ], were found guilty and responsible for the maltreatment of American and ] ]. They were ] by ] at ] in ] on December 23, 1948. Several others were sentenced to imprisonment between 7 and 22 years.{{Citation needed|date=May 2011}} | |||

| ==Post-war commemorations, apologies, and memorials== | ==Post-war commemorations, apologies, and memorials== | ||

| {{Main|Memorials to Bataan Death March victims}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] in Las Cruces, New Mexico]] | |||

| {{Main article|Memorials to Bataan Death March victims}} | |||

| On 13 September 2010 Japanese Foreign Minister ] apologized to a group of six former American soldiers who had been held as prisoners of war by the Japanese, including 90-year-old Lester Tenney and Robert Rosendahl, both survivors of the Bataan Death March. The six, their families, and the families of two deceased soldiers were invited to visit Japan at the expense of the Japanese government.<ref>{{cite web|date=2010|title=Japanese/American POW Friendship Program|url=http://www.us-japandialogueonpows.org/POWsTrip2010.htm|website=www.us-japandialogueonpows.org|url-status=usurped|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121016030933/http://www.us-japandialogueonpows.org/POWsTrip2010.htm |archive-date=October 16, 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| In 2012, film producer Jan Thompson created a film documentary about the Death March, POW camps, and ] titled ''Never the Same: The Prisoner-of-War Experience''. The film reproduced scenes of the camps and ships showed drawings and writings of the prisoners, and featured ] as the narrator.<ref>{{cite news|last=Brotman|first=Barbara|title=From Death March to Hell Ships|url=http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2013-04-01/features/ct-talk-brotman-pow-doc-0401-20130401_1_world-war-ii-veterans-allied-pows-bataan-death-march|newspaper=]|date=April 1, 2013|pages=Lifestyles}}</ref><ref>Among others, additional narration was provided by ], ], ], and ]. {{cite web|title=Never the Same: The Prisoner of War Experience|url=http://www.siskelfilmcenter.org/neverthesame|work=Gene Siskal Film Center|publisher=School of the Art Institute of Chicago|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20140328074435/http://www.siskelfilmcenter.org/neverthesame|archivedate=2014-03-28|df=}}</ref> | |||

| In 2012, film producer Jan Thompson created a film documentary about the Death March, POW camps, and ] titled ''Never the Same: The Prisoner-of-War Experience''. The film reproduced scenes of the camps and ships, showed drawings and writings of the prisoners, and featured ] as the narrator.<ref>{{cite news|last=Brotman|first=Barbara|title=From Death March to Hell Ships|url=https://www.chicagotribune.com/2013/04/01/from-death-march-to-hell-ships/|newspaper=]|date=April 1, 2013|pages=Lifestyles}}</ref><ref>Among others, additional narration was provided by ], ], ], and ]. {{cite web|title=Never the Same: The Prisoner of War Experience|url=http://www.siskelfilmcenter.org/neverthesame|work=Gene Siskal Film Center|publisher=School of the Art Institute of Chicago|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140328074435/http://www.siskelfilmcenter.org/neverthesame|archive-date=March 28, 2014}}</ref> | |||

| On September 13, 2010, Japanese Foreign Minister ] apologized to a group of six former American soldiers who, during World War II were held as prisoners of war by the Japanese, including 90-year-old Lester Tenney and Robert Rosendahl, both survivors of the Bataan Death March. The six, their families, and the families of two deceased soldiers were invited to visit Japan at the expense of the Japanese government.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.us-japandialogueonpows.org/POWsTrip2010.htm |date=2010 |title=Japanese/American POW Friendship Program|website=www.us-japandialogueonpows.org}}</ref> | |||

| Dozens of memorials (including monuments, plaques, and schools) dedicated to the prisoners who died during the Bataan Death March exist across the United States and in the Philippines. A wide variety of commemorative events are held to honor the victims, including holidays, athletic events such as ]s, and memorial ceremonies held at military cemeteries. | Dozens of memorials (including monuments, plaques, and schools) dedicated to the prisoners who died during the Bataan Death March exist across the United States and in the Philippines. A wide variety of commemorative events are held to honor the victims, including holidays, athletic events such as ]s, and memorial ceremonies held at military cemeteries. | ||

| === New Mexico === | |||

| On April 3, 2002, the memorial "Heroes of Bataan" was dedicated at Veteran's Park,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.las-cruces.org/en/live/veterans-corner/veterans-memorial-park|title=Veterans Memorial Park - Live - City of Las Cruces|website=www.las-cruces.org}}</ref> Las Cruces, New Mexico. It depicts three soldiers assisting each other during the Bataan Death March. Two of the soldiers are modeled after the uncles of Las Cruces resident J. Joe Martinez, with the Filipino soldier modeled after a NCO stationed at WSMR (White Sands Missile Range) whose grandfather was killed during the March. Leading up to the statue is an area where footprints of survivors were cast in concrete. | |||

| ] | |||

| The Bataan Death March had a large impact on ],<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.lcsun-news.com/bataan/ci_20249399/bataan-survivors-attend-rededication-monument-Saturday |title=Bataan survivors attend rededication of monument Saturday |author=Lauren E. Toney |newspaper=] |date=March 24, 2012 |access-date=February 22, 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130314155626/http://www.lcsun-news.com/bataan/ci_20249399/bataan-survivors-attend-rededication-monument-saturday |archive-date=March 14, 2013}}</ref> given that many of the American soldiers in Bataan were from that state, specifically from the ] and ] Coast Artillery of the National Guard.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://reta.nmsu.edu/bataan/timeline/1941.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040328074453/http://reta.nmsu.edu/bataan/timeline/1941.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=March 28, 2004 |title=Timeline |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |work=Battle for Bataan! |publisher=New Mexico State University |access-date=February 23, 2013}}</ref> The ] Bataan Memorial Museum is located in the armory where the soldiers of the 200th and 515th were processed before their deployment to the Philippines in 1941.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IJN3nIKsZ6MC&pg=PA82 |title=The Guide to U.S. Army Museums |last=Phillips |first=R. Cody |access-date=February 23, 2013 |year=2005 |publisher=Government Printing Office |isbn=978-0-16-087282-2 |page=82}}</ref> The old state capitol building of New Mexico was renamed the ] and now houses several state government agency offices.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.generalservices.state.nm.us/facilitiesmanagement/central_complex.aspx |title=Central Complex |website=www.generalservices.state.nm.us}}</ref> | |||

| Every year in early spring, the ], a ] {{convert|26.2|mi|km|adj=on}} march/run, is conducted at the ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.marathonguide.com/features/Articles/2007RecapOverview.cfm |title=USA Marathons & Marathoners 2007 |publisher=marathonguide.com |access-date=May 8, 2008}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Record Number Gather To Honor Bataan Death March |last=Schurtz |first=Christopher |newspaper=] |date= March 22, 2010 |page=1}}</ref> On 19 March 2017, over 6,300 participants queued up at the starting line for the 28th annual event, breaking the previous record of attendance as well as the amount of non-perishable food collected for local food pantries and overall charitable goods donated. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The 200th and 515th Coast Artillery units had 1,816 men total. 829 died in battle, while prisoners, or immediately after liberation. There were 987 survivors.<ref name="museum1">{{cite web |url=http://www.bataanmuseum.com/bataanhistory/ |title=History of Bataan Death March – New Mexico National Guard Museum |website=bataanmuseum.com |access-date=November 12, 2014 |archive-date=November 30, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161130144025/http://www.bataanmuseum.com/bataanhistory/ |url-status=dead}}</ref> {{As of|March 2017}}, only four of these veterans remained alive.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.abqjournal.com/973812/early-reviews-favorable-of-bataan-memorial-death-march.html |title=Early reviews favorable of Bataan Memorial Death March |first=Steve |last=Ramirez |publisher=] |website=www.abqjournal.com}}</ref> | |||

| The Bataan Death March had a large impact on the U.S. state of ],<ref>{{cite news|title=Bataan survivors attend rededication of monument Saturday |author=Lauren E. Toney |url=http://www.lcsun-news.com/bataan/ci_20249399/bataan-survivors-attend-rededication-monument-saturday |newspaper=Las Cruces Sun-News |date=24 March 2012 |accessdate=22 February 2013 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130314155626/http://www.lcsun-news.com/bataan/ci_20249399/bataan-survivors-attend-rededication-monument-saturday |archivedate=14 March 2013 |df= }}</ref> given that many of the U.S. soldiers in Bataan were from New Mexico, specifically from the 200th/515th Coast Artillery of the National Guard.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://reta.nmsu.edu/bataan/timeline/1941.html |title=Timeline |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |work=Battle for Bataan! |publisher=New Mexico State University |accessdate=23 February 2013}}</ref> The New Mexico National Guard Bataan Memorial Museum is located in the Armory where the soldiers of the 200th and 515th were processed before their deployment to the Philippines in 1941.<ref>{{cite book |last=Phillips |first=R. Cody |title=The Guide to U.S. Army Museums |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IJN3nIKsZ6MC&lpg=PA82&dq=Bataan%20Memorial%20Museum&pg=PA82#v=onepage&q=Bataan%20Memorial%20Museum&f=false |accessdate=23 February 2013 |year=2005 |publisher=Government Printing Office |isbn=9780160872822 |page=82}}</ref> Every year, in early spring, the ], a {{convert|26.2|mi|km|order=flip|abbr=on}} march/run is conducted at ], New Mexico.<ref>{{Cite web| url=http://www.marathonguide.com/features/Articles/2007RecapOverview.cfm| title=USA Marathons & Marathoners 2007|publisher=marathonguide.com|accessdate=May 8, 2008|postscript=<!--None-->}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|author=Schurtz, Christopher| title=Record Number Gather To Honor Bataan Death March|work=]|date= March 22, 2010|page= 1}}</ref> On March 19th 2017, over 6,300 participants queued up at the starting line for the 28th annual event, breaking not only all previous records of attendance but also the amount of non-perishable food collected for local food pantries and overall charitable goods donated. Out of all the veterans from New Mexico that survived the Bataan Death March, only four are still alive today.<ref></ref> | |||

| === Diego Garcia, British Indian Ocean Territory === | |||

| As of 2012, there were fewer than 1,000 survivors of the March still living.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bataanmuseum.com/bataanhistory/|title=History of Bataan Death March - New Mexico National Guard Museum|website=www.bataanmuseum.com}}</ref> The old state capitol building of New Mexico was renamed the Bataan Memorial Building and now houses several state government agency offices.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.generalservices.state.nm.us/facilitiesmanagement/central_complex.aspx|title=Central Complex|website=www.generalservices.state.nm.us}}</ref> | |||

| Due to the large population of Filipino workers on the island of ] in the ], an annual memorial march is held. The date varies, but the marchers leave from the marina around 06:00 traveling by boat to Barton Point, where they proceed south to the plantation ruins. The memorial march is conducted by Filipino workers, British ], British ], and United States sailors from various commands across the island.{{Citation needed|date=June 2021}} | |||

| ==Notable |

==Notable captives and survivors== | ||

| <!-- THIS SECTION is for NOTABLE |

<!-- THIS SECTION is for NOTABLE captives & survivors. That is, THOSE PEOPLE WITH[REDACTED] ARTICLES. For more information, see the WP essay ]. --> | ||

| {{div col|colwidth=15em}} | {{div col|colwidth=15em}} | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| Line 107: | Line 128: | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| Line 125: | Line 155: | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ]<ref>Shofner was an American officer, captured on Corregidor, who escaped ] in 1943.</ref> | * ]<ref>Shofner was an American officer, captured on Corregidor, who escaped ] in 1943.</ref> | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| <!--* ] DISPUTED – See Marcos article--> | |||

| {{div col end}} | {{div col end}} | ||

| <!-- This section is for NOTABLE survivors & captives. That is, THOSE PEOPLE WITH[REDACTED] ARTICLES. For more information, see the WP essay ]. --> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{Portal |

{{Portal|Philippines}} | ||

| {{columns-list|colwidth=30em| | {{columns-list|colwidth=30em| | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * '']'' (2005) | * '']'' (2005) | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| Line 166: | Line 200: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| == |

== Notes == | ||

| {{Notelist}} | |||

| '''Notes''' | |||

| {{Reflist|30em}} | |||

| == References == | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

| * Abraham, Abie (1997). . Vantage Press. {{ISBN|978- |

* Abraham, Abie (1997). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170331104534/http://www.ghostofbataan.com/bataan/bio.html |date=March 31, 2017 }}. Vantage Press. {{ISBN|978-0-533-11987-5}} | ||

| * Abraham, Abie (2001). ''Ghost of Bataan Speaks.'' Beaver Pond. {{ASIN|B004L73AXC}} | * Abraham, Abie (2001). ''Ghost of Bataan Speaks.'' Beaver Pond. {{ASIN|B004L73AXC}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last=Falk |first=Stanley L.|title=Bataan: The March of Death|year=1962|publisher=]|location=New York|oclc=1084550}} | * {{cite book|last=Falk |first=Stanley L.|title=Bataan: The March of Death|year=1962|publisher=]|location=New York|oclc=1084550}} | ||

| * {{Cite book|author=Harrison, Thomas R.|year=1989|title=Survivor: Memoir of Defeat and Captivity – Bataan, 1942|publisher=Western Epics, Inc., Salt Lake City, Utah|isbn= |

* {{Cite book|author=Harrison, Thomas R.|year=1989|title=Survivor: Memoir of Defeat and Captivity – Bataan, 1942|publisher=Western Epics, Inc., Salt Lake City, Utah|isbn=978-0-916095-29-1}} | ||

| * {{Cite book|author=Jackson, Charles|author2=Norton, Bruce H.|year=2003|title=I Am Alive!: A United States Marine's Story of Survival in a World War II Japanese POW Camp|publisher=Presidio Press|isbn= |

* {{Cite book|author=Jackson, Charles|author2=Norton, Bruce H.|year=2003|title=I Am Alive!: A United States Marine's Story of Survival in a World War II Japanese POW Camp|publisher=Presidio Press|isbn=978-0-345-44911-5}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last=Jansen|first=Marius B|title=The Making of Modern Japan|year=2000|publisher=]|location=Cambridge, MA|pages=654–655|isbn=978- |

* {{cite book|last=Jansen|first=Marius B|title=The Making of Modern Japan|year=2000|publisher=]|location=Cambridge, MA|pages=|isbn=978-0-674-00334-7|oclc=44090600|url=https://archive.org/details/makingofmodernja00jans/page/654}} | ||

| * {{cite book |first=Robert |last=Levering | |

* {{cite book |first=Robert |last=Levering |author-link=Robert W. Levering |title=Horror trek; a true story of Bataan, the death march and three and one-half years in Japanese prison camps |year=1948 |publisher=Horstman Printing |oclc=1168285|isbn=978-1-258-20630-7}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last=Lukacs|first=John D.|title= |

* {{cite book|last=Lukacs|first=John D.|title=Escape from Davao|year=2010|publisher=Simon & Schuster|location=New York|isbn=978-0-7432-6278-1 |oclc=464593097|title-link=Escape from Davao}} | ||

| * {{Cite book|author=Machi, Mario|year=1994|title=Under the Rising Sun, Memories of a Japanese Prisoner of War|publisher=Wolfenden, USA|isbn= |

* {{Cite book|author=Machi, Mario|year=1994|title=Under the Rising Sun, Memories of a Japanese Prisoner of War|publisher=Wolfenden, USA|isbn=978-0-9642521-0-3}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last=Masuda|first=Hiroshi|title=MacArthur in Asia: The General and His Staff in the Philippines, Japan, and Korea|year=2012|publisher=]|location=Ithaca, NY|isbn=978- |

* {{cite book|last=Masuda|first=Hiroshi|title=MacArthur in Asia: The General and His Staff in the Philippines, Japan, and Korea|year=2012|publisher=]|location=Ithaca, NY|isbn=978-0-8014-4939-0|url=https://archive.org/details/macarthurinasiag00masu}} | ||

| * {{Cite book|author=Moody, Samuel B.|author2=Allen, Maury|year=1961|title=Reprieve from Hell|publisher=Pageant Press |location=New York | oclc=14924946}} | * {{Cite book|author=Moody, Samuel B.|author2=Allen, Maury|year=1961|title=Reprieve from Hell|publisher=Pageant Press |location=New York | oclc=14924946}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last=Morrow|first=Don|title=Forsaken Heroes of the Pacific War: One Man's True Story|year=2011|publisher=]|location=Roanoke, VA|author2=Moore, Kevin|isbn=978- |

* {{cite book|last=Morrow|first=Don|title=Forsaken Heroes of the Pacific War: One Man's True Story|year=2011|publisher=]|location=Roanoke, VA|author2=Moore, Kevin|isbn=978-1-56592-479-6|oclc=725827438|url=https://archive.org/details/livesofcaptivere00petz}} | ||

| * {{Cite journal | last1 = Murphy | first1 = Kevin C. | doi = 10.1179/204243411X13201386799172 | title = 'Raw Individualists': American Soldiers on the Bataan Death March Reconsidered | journal = War & Society | volume = 31 | pages = 42–63 | year = 2012 | |

* {{Cite journal | last1 = Murphy | first1 = Kevin C. | doi = 10.1179/204243411X13201386799172 | title = 'Raw Individualists': American Soldiers on the Bataan Death March Reconsidered | journal = War & Society | volume = 31 | pages = 42–63 | year = 2012 | s2cid = 162118184 }} | ||

| * {{cite book|last1=Murphy|first1=Kevin C.|title=Inside the Bataan Death March: Defeat, Travail and Memory|date=October 13, 2014|publisher=McFarland|isbn=978- |

* {{cite book|last1=Murphy|first1=Kevin C.|title=Inside the Bataan Death March: Defeat, Travail and Memory|date=October 13, 2014|publisher=McFarland|isbn=978-0-7864-9681-5}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last1=Olson|first1=John E.|title=O'Donell: Andersonville of the Pacific|year=1985|publisher=John E. Olson|isbn=978- |

* {{cite book|last1=Olson|first1=John E.|title=O'Donell: Andersonville of the Pacific|year=1985|publisher=John E. Olson|isbn=978-99969-862-0-8}} | ||

| * {{Cite book|author1=Norman, Michael |

* {{Cite book|author1=Norman, Michael|author2=Norman, Elizabeth|name-list-style=amp|title=Tears in the Darkness|publisher=]|edition=revised|isbn=978-0-374-27260-9|date=June 9, 2009|url=https://archive.org/details/tearsindarknesst00norm}} | ||

| ** Also see: with the authors at the ] on September 24, 2009 | ** Also see: with the authors at the ] on September 24, 2009 | ||

| * {{Cite book|author=Resa, Jolinda Bull|year=2011|title=Honor Them Always: For the Sacrifice of Their Youth at Bataan|publisher=], Inc.|isbn=978- |

* {{Cite book|author=Resa, Jolinda Bull|year=2011|title=Honor Them Always: For the Sacrifice of Their Youth at Bataan|publisher=], Inc.|isbn=978-1-4327-7555-1 | oclc= 782073328}} | ||

| * {{cite book |last=Sides |first=Hampton | |

* {{cite book |last=Sides |first=Hampton |author-link=Hampton Sides |title=Ghost Soldiers |year=2001 |publisher=Anchor Books |location=New York |isbn=978-1-299-07651-8 | oclc=842990576|title-link=Ghost Soldiers }} | ||

| * {{Cite news|author=Stephens, Harold|date=October 16, 1994|title=Memories of the War|publisher="Times-Standard," Sect. Style/potpourri|location=Humboldt Co., CA.}} | * {{Cite news|author=Stephens, Harold|date=October 16, 1994|title=Memories of the War|publisher="Times-Standard," Sect. Style/potpourri|location=Humboldt Co., CA.}} | ||

| * {{Cite book|author=Stewart, Sidney|title=Give Us This Day|publisher=]|edition=revised|isbn= |

* {{Cite book|author=Stewart, Sidney|title=Give Us This Day|url=https://archive.org/details/giveusthisday00stew|url-access=registration|publisher=]|edition=revised|isbn=978-0-393-31921-7|year=1957}} | ||

| * {{Cite book|author=Tenney, Lester|year=2000|title=My Hitch in Hell|publisher=Brassey's|isbn=978- |

* {{Cite book|author=Tenney, Lester|year=2000|title=My Hitch in Hell|publisher=Brassey's|isbn=978-1-57488-298-8|url=https://archive.org/details/myhitchinhell00lest|oclc=557622115|url-access=registration}} | ||

| * {{Cite book|author=Young, Donald J.|year=1992|title=The Battle of Bataan: A History of the 90 Day Siege and Eventual Surrender of 75,000 Filipino and United States Troops to the Japanese in World War|publisher=McFarland|isbn= |

* {{Cite book|author=Young, Donald J.|year=1992|title=The Battle of Bataan: A History of the 90 Day Siege and Eventual Surrender of 75,000 Filipino and United States Troops to the Japanese in World War|publisher=McFarland|isbn=978-0-89950-757-6}} | ||

| By the grace of God... Author= Erwin Johnson. Survivor of the death martch | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| Line 200: | Line 236: | ||

| * | * | ||

| * – A link to the book's page on the publisher's website | * – A link to the book's page on the publisher's website | ||

| * | * | ||

| * – A narrative recounting one soldier's journey through Bataan, the march, prison camp, Japan, and back home to the United States. Includes a map of the march. | * – A narrative recounting one soldier's journey through Bataan, the march, prison camp, Japan, and back home to the United States. Includes a map of the march. | ||

| * – Information, maps, and pictures on the march itself and in-depth information on Japanese POW camps. | * – Information, maps, and pictures on the march itself and in-depth information on Japanese POW camps. | ||

| * | * | ||

| * – Comprehensive history of the Battle for Bataan, the Death March and the role of the 192nd Tank Battalion | * – Comprehensive history of the Battle for Bataan, the Death March and the role of the 192nd Tank Battalion | ||

| * | * | ||

| Line 209: | Line 245: | ||

| * | * | ||

| * and | * and | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 221: | Line 255: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 13:49, 22 January 2025

1942 Japanese war crime in the Philippines

| Bataan Death March | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of Bataan, World War II | |||||

A burial detail of American and Filipino prisoners of war uses improvised litters to carry fallen comrades at Camp O'Donnell, Capas, Tarlac, 1942, following the Bataan Death March. | |||||

| |||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

| Exact figures are unknown. Estimates range from 5,500 to 18,650 POW deaths. | |||||

The Bataan Death March was the forcible transfer by the Imperial Japanese Army of around 72,000 to 78,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war (POW) from the municipalities of Bagac and Mariveles on the Bataan Peninsula to Camp O'Donnell via San Fernando.

The transfer began on 9 April 1942 after the three-month Battle of Bataan in the Philippines during World War II. The total distance marched from Mariveles to San Fernando and from the Capas Train Station to various camps was 65 miles (105 km). Sources also report widely differing prisoner of war casualties prior to reaching Camp O'Donnell: from 5,000 to 18,000 Filipino deaths and 500 to 650 American deaths during the march.

The march was characterized by severe physical abuse and wanton killings. POWs who fell or were caught on the ground were shot. After the war, the Japanese commander, General Masaharu Homma and two of his officers, Major General Yoshitaka Kawane and Colonel Kurataro Hirano, were tried by United States military commissions for war crimes and sentenced to death on charges of failing to prevent their subordinates from committing atrocities. Homma was executed in 1946, and Kawane and Hirano in 1949.

Background

Prelude

When General Douglas MacArthur returned to active duty, the latest revision of plans for the defense of the Philippine Islands—War Plan Orange 3 (WPO-3)—was politically unrealistic, as it assumed a conflict only involving the United States and Japan, not the combined Axis powers. However, the plan was tactically sound, and its provisions for defense were applicable under any local situation.

Under WPO-3, the mission of the Philippine garrison was to hold the entrance to Manila Bay and deny its use to Japanese naval forces. If the enemy prevailed, the Americans were to hold back the Japanese advance while withdrawing to the Bataan Peninsula, which was recognized as the key to the control of Manila Bay. It was to be defended to the "last extremity". MacArthur assumed command of the Allied army in July 1941 and rejected WPO-3 as defeatist, preferring a more aggressive course of action. He recommended—among other things—a coastal defense strategy that would include the entire archipelago. His recommendations were followed in the plan that was eventually approved.

The main force of General Masaharu Homma's 14th Army came ashore at Lingayen Gulf on the morning of 22 December 1941. The defenders failed to hold the beaches. By the end of the day, the Japanese had secured most of their objectives and were in position to emerge onto the central plain. Late in the afternoon of 23 December General Jonathan Wainwright telephoned MacArthur's headquarters in Manila and informed him that any further defense of the Lingayen beaches was "impracticable". He requested and was given permission to withdraw behind the Agno River. MacArthur decided to abandon his own plan for defense and revert to WPO-3, evacuating President Manuel L. Quezon, High Commissioner Francis B. Sayre, their families, and his own headquarters to Corregidor on 24 December. A rear echelon, headed by the deputy chief of staff, Brigadier General Richard J. Marshall, remained behind in Manila to close out the headquarters and to supervise the shipment of supplies and the evacuation of the remaining troops.

On 26 December Manila was officially declared an open city, and MacArthur's proclamation was published in the newspapers and broadcast over the radio.

The Battle of Bataan began on 7 January 1942 and continued until 9 April when the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) commander, Major General Edward P. King, surrendered to Colonel Mootoo Nakayama of the 14th Army. King went against his superior's orders and told his troops to lay down their arms, accepting personal responsibility for the surrender. He made the following statement: "You men remember this. You did not surrender … you had no alternative but to obey my order."

Allied surrender

Homma and his staff encountered almost twice as many captives as his reports had estimated, creating an enormous logistical challenge: the transport and movement of over 60,000 starved, sick, wounded and debilitated prisoners and over 38,000 equally weakened civilian noncombatants who had been caught up in the battle. He wanted to move the prisoners and refugees to the north to get them out of the way of Homma's final assault on Corregidor, but there was simply not enough mechanized transport for the wounded, sick, and weakened masses.

Forced March

Following the surrender of Bataan on 9 April 1942 to the Imperial Japanese Army, prisoners were amassed in the towns of Mariveles and Bagac. They were ordered to turn over their possessions. American Lieutenant Kermit Lay recounted how this was done:

They pulled us off into a rice paddy and began shaking us down. There about a hundred of us so it took time to get to all of us. Everyone had pulled their pockets wrong side out and laid all their things out in front. They were taking jewelry and doing a lot of slapping. I laid out my New Testament. ... After the shakedown, the Japs took an officer and two enlisted men behind a rice shack and shot them. The men who had been next to them said they had Japanese souvenirs and money.

Word quickly spread among the prisoners to conceal or destroy any Japanese money or mementos, as their captors would assume it had been stolen from dead Japanese soldiers. American soldier Bert Bank recalls:

One of the POWs had a ring on and the Japanese guard attempted to get the ring off. He couldn't get it off and he took a machete and cut the man's wrist off and when he did that, of course the man was bleeding profusely. but when I looked back I saw a Japanese guard sticking a bayonet through his stomach.

Prisoners started out from Mariveles on 10 April and from Bagac on 11 April, converging in Pilar and heading north to the San Fernando railhead. The prisoners were put in groups of 100 men each, with four Japanese guards per group. At the beginning, there were rare instances of kindness by Japanese officers and those Japanese soldiers who spoke English, such as the sharing of food and cigarettes and permitting personal possessions to be kept. One prisoner who'd been a star football player at Notre Dame had his class ring taken by a guard. It was later returned by a Japanese officer who attended Notre Dame rival USC, had seen him play and had admired his athletic skills. This, however, was quickly followed by unrelenting brutality, theft, and even knocking men's teeth out for gold fillings, as the common Japanese soldier had also suffered in the battle for Bataan and had nothing but disgust and hatred for his "captives" (Japan did not recognize these people as POWs). The first atrocity—attributed to Colonel Masanobu Tsuji—occurred when approximately 350 to 400 Filipino officers and non-commissioned officers under his supervision were summarily executed in the Pantingan River massacre after they had surrendered. Tsuji—acting against General Homma's wishes that the prisoners be transferred peacefully—had issued clandestine orders to Japanese officers to summarily execute all American "captives". Although some Japanese officers ignored the orders, others were receptive to the idea of murdering POWs.

During the march, prisoners received little food or water, and many died. They were subjected to severe physical abuse, including beatings and torture. On the march, the "sun treatment" was a common form of torture. Prisoners were forced to sit in sweltering direct sunlight without helmets or other head coverings. Anyone who asked for water was shot dead. Some men were told to strip naked or sit within sight of fresh, cool water. Trucks drove over some of those who fell or succumbed to fatigue, and "cleanup crews" killed those too weak to continue, though trucks picked up some of those too fatigued to go on. Prisoners were randomly stabbed with bayonets or beaten.

Once the surviving prisoners arrived in Balanga, the overcrowded conditions and poor hygiene caused dysentery and other diseases to spread rapidly. The Japanese did not provide the prisoners with medical care, so U.S. medical personnel tended to the sick and wounded with few or no supplies. Upon arrival at the San Fernando railhead, prisoners were stuffed into sweltering, brutally hot metal box cars for the one-hour trip to Capas, in 43 °C (110 °F) heat. At least 100 prisoners were pushed into each of the unventilated boxcars. The trains had no sanitation facilities, and disease continued to take a heavy toll on the prisoners. According to Staff Sergeant Alf Larson: