| Revision as of 09:17, 23 December 2018 editWinged Blades of Godric (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers40,041 edits →Socio-political activities: CETags: nowiki added 2017 wikitext editor← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 13:21, 22 November 2024 edit undoSujit Lal Barua (talk | contribs)3 edits added content major works of Rajendralal mitraTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| (137 intermediate revisions by 32 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Bengali scholar}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2018}} | |||

| {{lead too short|date=February 2019}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=February 2019}} | |||

| {{Use Indian English|date=October 2018}} | {{Use Indian English|date=October 2018}} | ||

| {{Infobox person | {{Infobox person | ||

| | name = Raja Rajendralal Mitra | | name = Raja Rajendralal Mitra | ||

| | image = Rajendralal Mitra.JPG | | image = Rajendralal Mitra.JPG | ||

| | image_size = 200px | |||

| | caption = Raja Rajendralal Mitra | | caption = Raja Rajendralal Mitra | ||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|1822|2|16|df=yes}} | |||

| | native_name = রাজা রাজেন্দ্রলাল মিত্র | |||

| | birth_place = ], ], British India | |||

| | native_name_lang = bn | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|1824|2|15|df=yes}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], ], ] | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|1891|7|26|1824|2|15|df=yes}} | | death_date = {{Death date and age|1891|7|26|1824|2|15|df=yes}} | ||

| | death_place = ], ], |

| death_place = ], ], British India | ||

| | nationality = |

| nationality = British Indian | ||

| | occupation = Orientalist | | occupation = Orientalist scholar | ||

| | major works = Indo-Aryans vol 1, Antiquities of Orissa, Bod Gaya: The Hermitage of Sakya Muni | |||

| | spouse = | |||

| | spouse = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Raja Rajendralal Mitra''' (16 February |

'''Raja Rajendralal Mitra''' (16 February 1822 – 26 July 1891) was among the first Indian cultural researchers and historians writing in English. A polymath and the first Indian president of the ], he was a pioneering figure in the ].<ref name="Banglapedia">{{cite book |last=Imam |first=Abu |year=2012 |chapter=Mitra, Raja Rajendralal |chapter-url=http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Mitra,_Raja_Rajendralal |editor1-last=Islam |editor1-first=Sirajul |editor1-link=Sirajul Islam |editor2-last=Jamal |editor2-first=Ahmed A. |title=Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh |edition=Second |publisher=]}}</ref><ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p.">{{cite book|title=Indology, historiography and the nation : Bengal, 1847-1947|last=Bhattacharya|first=Krishna|publisher=Frontpage|year=2015|isbn=978-93-81043-18-9|location=Kolkata, India|chapter=Early Years of Bengali Historiography|oclc=953148596|chapter-url=http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/156642/6/06_chapter%202.pdf}}</ref> Mitra belonged to a respected family of Bengal writers.{{cn|date=July 2021}} After studying by himself, he was hired in 1846 as a librarian in the ], for which he then worked throughout his life as second secretary, vice president, and finally the first native president in 1885. Mitra published a number of Sanskrit and English texts in the Bibliotheca Indica series, as well as major scholarly works including The antiquities of Orissa (2 volumes, 1875–80), Bodh Gaya (1878), Indo-Aryans (2 volumes, 1881) and more.{{cn|date=July 2021}} | ||

| == Early life == | == Early life == | ||

| Raja Rajendralal Mitra was born |

Raja Rajendralal Mitra was born in Soora (now ]) in eastern ] (Kolkata), on 16 February 1822{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=370}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=29}} to Janmajeya Mitra. He was the third of Janmajeya's six sons and also had a sister.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=31}} Rajendralal was raised primarily by his widowed and childless aunt.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=32}} | ||

| The Mitra family traced its ] to ] |

The Mitra family traced its ] to ];{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=29}} and Rajendralal further claimed descent from the ] ] of ].{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=374}} The family were members of the ] ]{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=29}} and were devout ].{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=215}} Rajendralal's 4th great-grandfather Ramchandra was a ] of the ]{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=29}} and Rajendralal's great-grandfather Pitambar Mitra held important positions at the Royal Court of Ajodhya and Delhi.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=370}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=30}} Janmajeya was a noted oriental scholar, who was revered in ] and was probably the first Bengali to learn chemistry; he had also prepared a detailed list of the content of eighteen puranas.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=31}}<ref name=":1">{{Cite book|url=https://brill.com/view/title/15737|title=Notions of Nationhood in Bengal: Perspectives on Samaj, c. 1867-1905|last=Gupta|first=Swarupa|date=24 June 2009|publisher=Brill|isbn=9789047429586|series=Philosophy of History and Culture, Volume: 29|language=en|chapter=Nationalist Ideologues, Ideas And Their Dissemination|doi=10.1163/ej.9789004176140.i-414|chapter-url=https://brill.com/view/book/9789047429586/Bej.9789004176140.i-414_003.xml}}</ref> Raja Digambar Mitra of Jhamapukur was a relative of the family, as well.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| Due to a combination of the ]ness of his grandfather Vrindavan Mitra and his father's refusal to seek paid employment, Rajendralal spent his early childhood in poverty.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=30}} | |||

| === Education === | === Education === | ||

| Rajendralal Mitra received his early education |

Rajendralal Mitra received his early education in ] at a village school,{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=32}} followed by a private ] school in ].{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=32}} At around 10 years of age, he attended the ] in Calcutta.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=33}} Mitra's education became increasingly sporadic from this point; although he enrolled at ] in December 1837—where he apparently performed well—he was forced to leave in 1841 after becoming involved in a controversy.{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=34,35}} He then began ], although not for long,{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=35}} and then changed to studying languages including ], ], ] and ], which led to his eventual interest in ].{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=371}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=35,36}} | ||

| === Marriages === | === Marriages === | ||

| In |

In 1839, when he was around 17 years old, Mitra married Soudamini.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=33}} They had one child, a daughter, on 22 August 1844 and Soudamini died soon after giving birth.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=36}} The daughter died within a few weeks of her mother.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=36}} Mitra's second marriage was to Bhubanmohini, which took place at some point between 1860 and 1861. They had two sons: Ramendralal, born on 26 November 1864, and Mahendralal.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=60}} | ||

| == Asiatic Society == | == Asiatic Society == | ||

| Mitra was appointed librarian-cum-assistant-secretary of the ] in April 1846.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=36}}He held the office for nearly 10 years, vacating it in February 1856. He was subsequently elected as the Secretary of the Society |

Mitra was appointed librarian-cum-assistant-secretary of the ] in April 1846.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=36}} He held the office for nearly 10 years, vacating it in February 1856. He was subsequently elected as the Secretary of the Society and was later appointed to the governing council. He was elected vice-president on three occasions, and in 1885 Mitra became the first Indian president of the Asiatic Society.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=371}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.asiaticsocietycal.com/history/1.htm|title=History|publisher=]|access-date=18 September 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130918050523/http://www.asiaticsocietycal.com/history/1.htm|archive-date=18 September 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref>{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=37}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=56}} Although Mitra had received little formal training in history, his work with the Asiatic Society helped establish him as a leading advocate of the ] in ].<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." />{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=371}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=37}} Mitra was also associated with ''Barendra Research Society of Rajshahi''—a local historical society.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| == Influences and methodology == | |||

| During his tenure at the Asiatic Society, Rajendralal came in contact with many notable persons{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=37}} and was impressed by two thought-streams of ]. Noted scholars ] (the founder of Asiatic Society) and ] had propounded a theory of ] and sought to make a comparative study of different races by chronicling history through cultural changes rather than political events whilst ] ''et al.'' sought greater cultural diversity and glorified the past.{{sfn|Sur|1974|pp=371,372}} Mitra went on to utilize the tools of ] and ] to write an orientalist narrative of the cultural history of the Indo-Aryans.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=373}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=168}} Although Mitra subscribed to the philosophies of orientalism, he did not subscribe to blindly following past precedents and asked others to shun traditions, if they hindered the progress of the nation.{{sfn|Sur|1974|pp=372,373}} | |||

| == Historiography == | == Historiography == | ||

| Mitra was a noted antiquarian and played a substantial role in discovering and deciphering historical inscriptions, coins, and texts.<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p.2">{{cite book|title=Indology, historiography and the nation : Bengal, 1847-1947|last=Bhattacharya|first=Krishna|publisher=Frontpage|year=2015|isbn=978-93-81043-18-9|location=Kolkata, India|chapter=Early Years of Bengali Historiography|oclc=953148596|chapter-url=http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/156642/6/06_chapter%202.pdf}}</ref>{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=116,117}} He established the relationship between the ] and ], thus identifying the year of ]'s ascent to the throne,{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=157}} and contributed to an accurate reconstruction of the history of Medieval Bengal, especially that of the ] and ] dynasties, by deciphering historical edicts.<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." />{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=155,156, 160-167}} He studied the ], discovering many unknown kings and chieftains, and assigned approximate time spans to them. He was also the only historian among his contemporaries to assign a near-precise time frame to the rule of ].<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." />{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=158}} Mitra's affinity for factual observations and inferences and dislike for abstract reasoning, in contrast with most Indo-historians of those days, has been favorably received in later years.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=373}} | |||

| == Cataloging, translation and commentary == | |||

| As a librarian of the Asiatic Society, Rajendralal was charged with cataloging Indic manuscripts collected by the ]s of the Society. He, along with several other scholars, followed a central theme of the ] that emphasized the collection of ancient texts ('']'') followed by their translation into the ]. A variety of Indic texts, along with extensive commentaries, were published, especially in the ] series,{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=39,114,207}} and many were subsequently translated into English.<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." />{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=223–225}} Mitra's instructions for the Pandits to copy the texts verbatim and abide by the concept of '']'' (different readings) has been favourably critiqued''.''{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=210}} Mitra was also one of the few archivists who emphasized the importance of cataloguing and describing all manuscripts, irrespective of factors like rarity.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://brill.com/view/title/17012|title=Aspects of Manuscript Culture in South India|last=Zysk|first=Kenneth G.|date=2012-07-25|publisher=Brill|isbn=9789004223479|editor-last=Rath|editor-first=saraju|series=Brill's Indological Library, Volume: 40|language=en|chapter=The Use of Manuscript Catalogues as Sources of Regional Intellectual History in India’s Early Modern Period|doi=10.1163/9789004223479|chapter-url=https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004223479/B9789004223479-s014.xml}}</ref> | |||

| During his days in the Asiatic Society, Rajendralal came in contact with many distinguished luminaries{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=37}} and was distinctly impressed by two thought-streams of ]. Noted scholars like ] (who was also the founder of Asiatic Society) and ] propounded a theory of universal-ism and sought to make a comparative study of different races by chronicling history through the lens of cultural changes rather than political events and ] et al. sought for greater cultural diversity and glorified the past.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=371,372}} Subsequently, he went on to utilize the tools of ] and ] in penning down a narrative of the cultural history of Indo-Aryans.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=373}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=168}} | |||

| Though he subscribed to the philosophies of ], he did not subscribe to a blind adoption of the past and actively asked others to shun tradition, if they hindered the progress of the nation.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=372,373}} | |||

| === Works === | |||

| A noted antiquarian, Rajendralal played a substantial role in discovering and deciphering historical inscriptions, coins and texts.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=116,117}} He established the relation between ] and ] thus identifying the year of ]'s ascent to throne{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=157}} and also contributed towards an accurate reconstruction of the history of Medieval Bengal esp. of the ]<nowiki/>a and ]<nowiki/>a dynasties, by deciphering historical ].{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=155,156, 160-167}} He intensively studied the ], discovering many unknown kings/chieftains and assigned approximate time-spans to them. He was also the only historian, among his contemporaries to assign a near-precise time-frame to the rule of ].{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=158}} | |||

| His affinity for concrete factual observations and inferences along with a dislike for abstract reasoning, (in contrary to most Indo-Historians of those days), has been favorably received.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=373}} | |||

| == Cataloging, Translation and Commentary == | |||

| As a librarian of the Asiatic Society, Rajendralal was endowed with the charge of cataloging old Indic manuscripts, that were collected by the Pandits of the Society from across the country. He (along with several other scholars) choose to follow a central theme of ] that emphasised not only on mere collection of ancient texts ('']'') but also on their translation to the lingua-franca. A variety of Indic Text(s), along with extensive commentaries, were published (esp. in ]){{sfn|Ray|1969|p=39,114,207}} and often they were translated to English.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=223-225}} | |||

| His instructions for the Pandits to copy the texts ''verbatim'' and abide by the concept of ''Variae Lectiones'' was favorably critiqued''.''{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=210}} His efforts were widely acclaimed and renowned polymath ] has noted that whilst Rajendralal's editions has been superseded by more accurate translations and commentaries, they retain significant value as the ].{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=213}} | |||

| == Archaeology == | == Archaeology == | ||

| ] | |||

| Rajendralal did significant work as to chronicling the development of Aryan architecture in prehistoric times. | |||

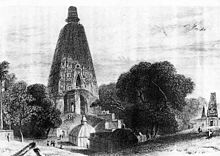

| Mitra did significant work in documenting the development of Aryan architecture in prehistoric times. Under the patronage of the ] and the ], Mitra led an expedition to the ] region of ] in 1868–1869 to study and obtain casts of Indian sculptures.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Guha-Thakurta |first=Tapati |chapter=Monuments and Lost Histories |title=Proof and Persuasion: Essays on Authority, Objectivity, and Evidence|editor1-last=Marchand|editor1-first=Suzanne L. |editor1-link=Suzanne L. Marchand|editor2-last=Lunbeck|editor2-first=Elizabeth|editor2-link=Elizabeth Lunbeck|year=1996|publisher=Brepols|isbn=978-2-503-50547-3|page=161|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XFzjSSnT5NUC&pg=PA101|title=Monuments, Objects, Histories: Institutions of Art in Colonial and Post-Colonial India|last=Guha-Thakurta|first=Tapati|date=2004-08-05|publisher=Columbia University Press|isbn=9780231503518|language=en}}</ref> The results were compiled in '']'', which has since been revered as a ''magnum opus'' about ] architecture.<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." />{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=131}} The work was modelled on ''Ancient Egyptians'' by ] and published in two volumes consisting of his own observations followed by a reconstruction of the socio-cultural history of the area and its architectural depictions.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=133}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=168–170}} Along with ], Mitra also played an important role in the excavation and restoration of the ].<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/in-the-land-of-the-buddha/article3432504.ece|title=In the land of the Buddha|last=Santhanam|first=Kausalya|date=18 May 2012|work=The Hindu|access-date=25 December 2018|issn=0971-751X}}</ref> Another of his major works is '']'' which collated the observations and commentaries of various scholars about ].{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=151–153}} | |||

| These works, along with his other essays, contributed to a detailed study of varying forms of temple architecture across India.{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=142–146}} Unlike his European counterparts, who attributed the presence of nude sculptures in Indian temples to a perceived lack of morality in ancient Indian social life, Mitra correctly hypothesized the reasons for it.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=149}} | |||

| Under the patronage of ] and the ], Rajendralal led an expedition into the Bhubaneshwar region of ] during 1868-69 to study and obtain casts of Indian sculpture.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.in/books/about/Proof_and_Persuasion.html?id=avXWAAAAMAAJ|title=Proof and Persuasion: Essays on Authority, Objectivity, and Evidence|last=Marchand|first=Suzanne L.|last2=Lunbeck|first2=Elizabeth|last3=Blok|first3=Josine|date=1996|publisher=Brepols|year=|isbn=9782503505473|location=|pages=161|language=en}}</ref> The results were compiled in ''The Antiquities of Orissa'' which has since been revered as a ''magnum opus'' about Odisan architecture.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=131}} Modeled on ''Ancient Egyptians'' by ] and published in two volumes, they consisted of his own observations followed by a reconstruction of the socio-cultural history, in light of the architectural depictions.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.in/books?id=HDluAAAAMAAJ&q=rajendralal+mitra&dq=rajendralal+mitra&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwir4fuTv8XeAhULpI8KHa_2A4U4KBDoAQgoMAA|title=Perceptions of South Asia's visual past|last=Asher|first=Catherine Ella Blanshard|last2=Metcalf|first2=Thomas R.|date=1994|publisher=American Institute of Indian Studies, New Delhi, Swadharma Swarajya Sangha, Madras, and Oxford & IBH Pub. Co.|isbn=9788120408838|language=en}}</ref>{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=133}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=168-170}}''Buddha Gaya: the hermitage of Sakya Muni'' was another major contribution that collated the observations and commentaries of various scholars about ].{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=151-153}} | |||

| A standard theme of Rajendralal's archaeological texts is the rebuttal of the prevalent European scholarly notion that India's architectural forms, especially stone buildings, were derived from the Greeks and that there was no significant architectural advancement in the Aryan civilization.{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=136–141}}{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=375}}<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6W7_UN97VhYC&pg=PA71|title=An Intellectual History for India|last=Kapila|first=Shruti|date=31 May 2010|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-19975-9|language=en|access-date=8 November 2018}}</ref>{{page needed|date=February 2019}} He often noted that the architecture of pre-Muslim India is equivalent to the Greek architecture and proposed the racial similarity of the Greeks and the Aryans, who had the same intellectual capacity.<ref name=":2" />{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=147}} Mitra often came into conflict with European scholars regarding this subject, such as his acrimonious dispute with ]{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=132}}.<ref name=":2" /><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/allahabad/History-department-of-Allahabad-University-celebrates-60th-anniversary/articleshow/51758510.cms|title=History department of Allahabad University celebrates 60th anniversary |website=The Times of India|date=9 April 2016 |access-date=25 December 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181230052056/https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/allahabad/History-department-of-Allahabad-University-celebrates-60th-anniversary/articleshow/51758510.cms|archive-date=30 December 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> After Mitra criticized Fergusson's commentary about Odisa architecture in ''The Antiquities of Orissa'',{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=132}} Fergusson wrote a book titled ''Archaeology in India With Especial Reference to the Work of Babu Rajendralal Mitra''.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=134}} While many of Mitra's archaeological observations and inferences were later refined or rejected, he was a pioneer in the field{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=127}} and his works were often substantially better than those of his European counterparts.{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=122,124}} | |||

| Both of these works along with his other miscellaneous essays contributed immensely to a detailed study of varying forms of temple-architecture across the Indian landscape.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=142-146}} He was also the first scholar to correctly hypothesise about the reasons behind nude sculptures in temple-premises unlike his European counterparts who simply attributed them to a perceived lack of morality in ancient Indian social life.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=149}} | |||

| == Linguistics == | |||

| A standard theme of Rajendralal's archaeological discourses was to rebut the prevalent European scholarly notion that India's architectural forms (esp. the art of building in stone) was derived from the Greeks and that there was no significant architectural advancement in the Aryan civilization.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=136-141}}{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=375}}<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.in/books?id=6W7_UN97VhYC&lpg=PA71|title=An Intellectual History for India|last=Kapila|first=Shruti|date=2010-05-31|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=9780521199759|language=en}}</ref> He often noted that the architecture of pre-Moslem India was equivalent to the Greek architecture and propounded the racial similarity of the Greeks and the Aryans, who had the same intellectual capacity.<ref name=":2" />{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=147}} Rajendralal oft-conflicted with European scholars in the regard and his acrimonious dispute with ]{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=132}} has interested many historians.<ref name=":2" /> Ferguson would later even write a book titled ''Archaeology in India With Especial Reference to the Work of Babu Rajendralal Mitra''{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=134}} to rebut Rajendralal's ''The Antiquities of Orissa'', which criticized Ferguson's about Odisa architecture.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=132}}Mostly comprising of ''ad-hominems<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.in/books?id=DvUtDwAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&dq=rajendralal%20mitra&pg=PT217#v=onepage&q&f=false|title=Art and Its Global Histories: A Reader|last=Newall|first=Diana|date=2017-07-30|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9781526119933|language=en}}</ref>'' and an acute politicization of the issue, the discourses shed light on the broader themes of nationalism.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.in/books/about/Proof_and_Persuasion.html?id=avXWAAAAMAAJ|title=Proof and Persuasion: Essays on Authority, Objectivity, and Evidence|last=Marchand|first=Suzanne L.|last2=Lunbeck|first2=Elizabeth|last3=Blok|first3=Josine|date=1996|publisher=Brepols|year=|isbn=9782503505473|location=|pages=162,163|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Rajendralal Mitra was the first Indian who tried to engage people in a discourse of the ] and ] of Indian languages, and tried to establish ] as a science.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=182}} He debated European scholars about linguistic advances in Aryan culture and theorized that the Aryans had their own script that was not derived from Dravidian culture.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=183}} Mitra also did seminal work on ] and ] literature of the ]s, as well as on the ] dialect.{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=185–189}} | |||

| Whilst, much of his archaeological observations and corresponding inferences were later refined and/or rejected, he did pioneer work in the field{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=127}} and his works were often substantially better than that of his European counterparts.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=122,124}} | |||

| == Lingustics == | |||

| Rajendralal was the first Indian who tried to engage the common populace in a discourse of the ] and ] of Indian languages and tried to establish philology as a science.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=182}} He debated European scholars on the locus of linguistic advances in Aryan culture and propounded that the Aryans had their own script, which was not derived from Dravidian culture.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=183}} Rajendralal also did seminary work in the fields of Sanskrit Buddhist language and literature and ] dialect, in particular.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=185-189}} | |||

| === Vernacularization === | === Vernacularization === | ||

| Mitra was a pioneer in the publication of maps in the Bengali language and he also constructed Bengali versions of numerous geographical terms that were previously only used in English.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bose |first=Pradip Kumar |year=2006 |title=Health and Society in Bengal: A Selection From Late 19th Century Bengali Periodicals |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=N0VBDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT18 |publisher=SAGE Publishing India |pages=16–17 |isbn=978-0-7619-3418-9 |language=en |access-date=4 November 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181107185240/https://books.google.com/books?id=N0VBDwAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&pg=PT18 |archive-date=7 November 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> He published a series of maps of districts of Bihar, Bengal, and Odisa for indigenous use that were notable for his assignment of correct names to even small villages, sourced from local people.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Dasgupta |first=Keya |year=1995 |chapter=A City Away from Home: The Mapping of Calcutta |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WIa-A2bM3n0C&pg=PA151 |editor-last=Chatterjee |editor-first=Partha |editor-link=Partha Chatterjee (scholar) |title=Texts of Power: Emerging Disciplines in Colonial Bengal |publisher=University of Minnesota Press |pages=150–151 |isbn=978-0-8166-2687-8 |language=en}}</ref> Mitra's efforts in the vernacularization of western science has been widely acclaimed.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Connecting Histories of Education: Transnational and Cross-Cultural Exchanges in (Post)Colonial Education|last=Ikhlef|first=Hakim|publisher=Berghahn Books|year=2014|isbn=9781782382669|editor-last=Bagchi|editor-first=Barnita|edition=1|chapter=Constructive Orientalism: Debates on Languages and Educational Policies in Colonial India, 1830–1880|editor-last2=Fuchs|editor-first2=Eckhardt|editor-last3=Rousmaniere|editor-first3=Kate|jstor = j.ctt9qcxsr}}</ref> | |||

| As a |

As a co-founder of the short-lived ]—a literature society set up by ] with help from the colonial government for publication of higher-education books in Bengali and enrichment of Bengali language in 1882<ref name=":1" />—he wrote "A Scheme for the Rendering of European Scientific terms in India", which contains ideas for the vernacularization of scientific discourse.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bose |first=Pradip Kumar |year=2006 |title=Health and Society in Bengal: A Selection From Late 19th Century Bengali Periodicals |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=N0VBDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT19 |publisher=SAGE Publishing India |pages=17–18 |isbn=978-0-7619-3418-9 |language=en}}</ref> He was also a member of several other societies, including the ],{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=40}} and ],{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=39}} which played important roles in the propagation of vernacular books, esp. in Bengali literature, and in Wellesley's Textbook Committee (1877).{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=93}} Many of his Bengali texts were adopted for use in schools{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=40}} and one of his texts on Bengali Grammar and his "''Patra-Kaumudi''" (Book of Letters) became widely popular in later times.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=40}} | ||

| === Publication of magazines === | === Publication of magazines === | ||

| From 1851 onward, under a grant |

From 1851 onward, under a grant from the Vernacular Literature Society, Mitra started publishing the '']'', an illustrated monthly periodical. It was the first of its kind in Bengal and aimed to educate Indian people in western knowledge without coming across as too rigid.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=40}}<ref>{{Citation|chapter=Imperial science and the Indian scientific community|date=2000-04-20|pages=129–168|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=9781139053426|doi=10.1017/chol9780521563192.006|title=Science, Technology and Medicine in Colonial India}}</ref> It had a huge readership, and introduced the concept of literary criticism and reviews into Bengali literature. It is also notable for introducing ]'s Bengali works to the public. | ||

| Mitra retired from its editorship |

Mitra retired from its editorship in 1856, citing health reasons. ] took over the role.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=41}}<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://www.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/Englisch/fachinfo/suedasien/zeitschriften/bengali/bibidhartha.html|title=Bibidhartha samgraha (Calcutta, 1851-1861)|website=Heidelberg University Library|language=de|access-date=4 November 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181107150033/https://www.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/Englisch/fachinfo/suedasien/zeitschriften/bengali/bibidhartha.html|archive-date=7 November 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> In 1861, the government compelled the magazine to withdraw from publication; then in 1863, Mitra started a similar publication under the name ''Rahasya Sandarbha'', maintaining the same form and content.<ref name=":0" />{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=44}} This continued for about five and a half years before closing voluntarily. Mitra's writings in these magazines have been acclaimed.<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." /> He was also involved with the '']'', of which he held editorial duties for a while.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=63}} | ||

| He was also involved with the ''Hindoo Patriot'' for a long span of time and held editorial duties, for a while.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=63}} | |||

| == Socio-political activities == | == Socio-political activities == | ||

| Rajendralal was a prominent social figure during his times and was close to several contemporary thinkers including ], ], ], ] et al.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=78}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=61,62,74}} His name has been regularly located in wide forms of social activities ranging from hosting condolence meetings to presiding '']<nowiki/>s'' and giving political speeches.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=64,65,66,81,82}} | |||

| Rajendralal Mitra was a prominent social figure and a poster child of the Bengal renaissance.<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." /> Close to contemporaneous thinkers including ], ], ], ], ], and ],<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." />{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=61,62,74,78}} he partook in a wide range of social activities ranging from hosting condolence meetings to presiding over '']'' and giving political speeches.{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=64,65,66,81,82}} He held important roles in a variety of societies including the famed ].{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=45}} He was an executive committee member of the ],<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." /> served as a translator for the ]{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=53,59}} and was an influential figure in the ], which played an important role in the development of voluntary education in Bengal.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=50}} | |||

| ''<nowiki/>'' | |||

| Mitra wrote several essays about social activities. Describing widow-remarriage as an ancient societal norm, he opposed its portrayal as a corruption of Hindu culture and also opposed polygamy.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=53}} He wrote numerous discourses on the socio-cultural history of the nation, including about beef consumption and the prevalence of drinking alcohol in ancient India-the latter at a time when Muslims were increasingly blamed for the social affinity for drinking.<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." />{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=171,172}} Mitra was generally apathetic towards religion; he sought the disassociation of religion from the state and spoke against the proposals of the colonial government to tax Indians to fund the spread of Christian ideologies.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=84}} | |||

| He held important roles in a variety of societies and had a role in the management of the ].{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=45}} He also served as a translator in Calcutta Photographic Society{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=53,59}} and was an influential figure in the Society for the Promotion of the Industrial Art, which took major roles in the development of voluntary education in Bengal.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=50}} | |||

| From 1856 until its closure in 1881, Mitra was the director of the ], an establishment formed by the Colonial Government for the privileged education of the heirs of '']s'' and other upper classes.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=54}} He was active in the ] since its inception, serving as its president for three terms (1881–82, 1883–84, 1886–87) and vice-president for another three terms (1878–80, 1887–88, 1890–91). Several of his speeches on regional politics have also been recorded.<ref name="Banglapedia" />{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=48,83}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=81,85,86}} Mitra was involved with the ], serving as the president of the Reception Committee in the Second National Conference in Calcutta<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." />{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=91}} and was also a ] of the ] for many years, having served as its commissioner from 1876.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=75}} | |||

| He wrote essays chronicling widow-remarriage as an ancient societal norm; vouching against its portrayal as a corruption of the Hindu culture and opposed polygamy.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=53}} He also wrote numerous discourses on the socio-cultural history of the nation including on the topics of beef-consumption in ancient India, prevalence of drinking et al.; the latter at a time when Moslems were increasingly blamed for the social affinity for drinking.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=171,172}} | |||

| == Criticism == | |||

| He has been noted to be apathetic as to religious stuff but seeking for a disassociation of religion from state, spoke against the proposals of the Colonial Government to tax the natives for spread of Christian ideologies.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=84}} | |||

| Despite the general acclaim that has met his works, Rajendralal Mitra has also been the subject of criticism. Despite his self-declared agnosticism towards Indian mythology and his criticism of Indians' obsession with the uncritical acceptance of the glory of their own past, his works have suffered from ethno-nationalist biases.<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." /> | |||

| Mitra often intended to prove the ancient origin of the Hindus; his acceptance of legends and myths at face value is evident in his ''Antiquities in Orissa''.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=374}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=169}} In the reconstruction of the history of the ], Mitra relied upon a number of ideal propositions rather than contemporarily accepted genealogical tables whose authenticity Mitra doubted, and assigned historical status to the ] myth.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=374}} Later studies have shown the shortcomings of his works did not render his inferences entirely invalid or absurd.{{citation needed|date=January 2019}} | |||

| He was a member of Wellesley's Textbook Committee set up in 1877.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=93}} From 1856 to 1881 (till its closure), he was also the Director of the Wards' Institution, an establishment formed by the Colonial Government for privileged education of the wards of Zamindars and upper classes.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=54}} | |||

| Mitra held the ] to be a superior race and wrote numerous discourses covering time spans that were self-admittedly far removed from the realms of authentic history.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=374}} His archaeological discourses have been criticized for suffering from the same issues and being used to promote the view that Aryans settled in Northern India. A preface of one of his books says: | |||

| He was actively associated with the ] since its inception; serving as the President for 3 terms (1881–82, 1883–84, 1886–87) and Vice-President for another 3 terms (1878-80, 1887-88, 1890-91). Several speeches on the broader locus of regional politics have been recorded.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=48,83}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=81,85,86}}<ref name="Banglapedia" />He was a ] of the ] for many years and also served as its Commissioner from 1876.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=75}} He was also involved with ].{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=91}} | |||

| <blockquote>The race of whom it is proposed to give a brief sketch in this paper belonged to a period of remote antiquity, ''far'' away from the range of authentic history; ... The subject, however, is of engrossing interest, concerning, as it does, the early history of the ''most'' progressive branch of the human race.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=374}}</blockquote> | |||

| He venerated Hindu rule and had a profound dislike of the Muslim invasion of India.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=375}} According to Mitra: | |||

| == Criticism == | |||

| <blockquote>Countries like Kabul, Kandahar and Balkh from where Muslims had flooded India and had destroyed Hindu freedom, had sometimes been brought under the sway of the kings of the Sun (Saura) dynasty. Sometimes peoples of those countries had passed their days by carrying the orders of the Hindus. The dynasty had a tremendous power with which it had been ruling India for two thousand years;... Moslem fanaticism, which after repeated incursions, reigned supreme in India for six hundred years, devastating everything Hindu and converting every available temple, or its materials, into masjid, or a palace, or a heap of ruins, was alone sufficient to sweep away everything in the way of sacred building.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=375}}</blockquote> | |||

| He often accepted legends and myths at their face-value as was evident from his ''Antiquities in Orissa''.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=374}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=169}} That he often intended to prove the ancient origin of the Hindus also affected his works. In the reconstruction of the history of Sen dynasty, he had to self-construct and rely upon a wide number of propositions whilst accepting genealogical tables (whose authenticity was highly doubted by himself) and even tried to assign a historical status to the Adisura myth.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=374}} Remarkably though, his inferences were not found to be extraordinarily absurd in light of later studies. | |||

| ] criticized Mitra's command of Sanskrit grammar; some contemporaneous writers described him as having exploited Sanskrit Pandits in the collecting and editing of ancient texts without giving them the required credit.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=11}} However, this criticism has been refuted.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=212}} | |||

| He also held the Indo-Aryan civilization to be superior than others and wrote numerous discourses that covered spans, which were (self-admittedly) far away from the realms of authentic history.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=374}} A preface of one of his book mentions{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=374}}:- <blockquote>The race of whom it is proposed to give a brief sketch in this paper belonged to a period of remote antiquity, ''far'' away from the range of authentic history....The subject, however, is of engrossing interest, concerning, as it does, the early history of the ''most'' progressive branch of the human race.</blockquote>He also shared a veneration for the Hindu rule and a profound dislike for the Muslim invasion of the nation.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=375}} Rajendralal writes{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=375}}:- <blockquote>Countries like Kabul, Kandahar and Balkh from where Muslims had flooded India and had destroyed Hindu freedom, had sometimes been brought under the sway of the kings of the Sun (Saura) dynasty. Sometimes peoples of those countries had passed their days by carrying the orders of the Hindus. The dynasty had a tremendous power with which it had been ruling India for two thousand years.......</blockquote><blockquote>Moslem fanaticism, which after repeated incursions, reigned supreme in India for six hundred years, devastating everything Hindu and converting every available temple, or its materials, into masjid, or a palace, or a heap of ruins, was alone sufficient to sweep away everything in the way of sacred building.</blockquote>] had criticized Rajendralal's command of Sanskrit grammar and he was often portrayed as having exploited Sanskrit Pandits in the collecting and editing of ancient texts, without giving them the required credit,{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=11}} though it has been refuted.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=212}} Much of his commentaries, were faulty and was later rejected by scholars.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=13}} | |||

| His equating extreme examples of Tathagata Tantric traditions |

Many of Mitra's textual commentaries were later deemed to be faulty and rejected by modern scholars.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=13}} His equating of extreme examples of ] traditions from ] scriptures in a literal sense and as an indicator of mainstream Buddhist Tantra, "the most revolting and horrible that human depravity could think of", were criticised and rejected, especially because such texts were long historically disconnected from the culture that created and sustained them.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Wedemeyer |first=Christian K. |author-link=Christian K. Wedemeyer |year=2012 |title=Making Sense of Tantric Buddhism: History, Semiology, and Transgression in the Indian Traditions |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=urzm9J4tbpwC&pg=PR24 |publisher=Columbia University Press |page=2 |isbn=978-0-231-53095-8 |quote=Rajendralal Mitra, was understandably troubled by similar statements found in the ... ''Guhyasmāja'' (''Esoteric Community'') ''Tantra''. Finding these 'at once the most revolting and horrible that human depravity could think of,' ... He cautioned, however, that following this particular interpretative avenue ... may be premature.'}}</ref>{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=220,221}} Renowned polymath ] has noted that while Mitra's works have been superseded by more accurate translations and commentaries, they still retain significant value as the '']''.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=213}} | ||

| Some of Mitra's extreme biases might have been a response to European scholars like ], who were extremely anti-Indian in their perspectives. In addition, orientalist scholarship had a number of unavoidable limitations, including the lack of social anthropology.<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." />{{sfn|Sur|1974|pp=375,376}} Mitra has been also criticised for not speaking out against the conservative society in favor of social reform, and for maintaining an ambiguous, nuanced stance.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=22}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=79}} For example, when the British Government sought the views of notable Indian thinkers about establishing a minimum legal age for marriage with the aim of abolishing child marriage, Mitra spoke against the ban, emphasizing the social and religious relevance of child marriage and Hindu customs.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=93}} | |||

| His archaeological discourses have been criticized as deemed to have been quite motivated by the locus of establishing Indo-Aryan superiority and utilizing them to establish the view that the ancient settlement place of Aryans corresponded to Northern India.. | |||

| He has been criticised to not actively speak out against the conservative society or for the need of any social reform and maintaining an ambiguous nuanced stance.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=22}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=79}} When the British Government sought for the views of notable Indian thinkers as to establishing a minimum legal of marriage with an aim to abolish child-marriage, Rajendralal spoke against it, emphasizing upon the social and religious relevance of child-marriage and Hindu customs.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=93}} | |||

| Some of the extreme biases might have stemmed in, as a response to European scholars like ] et al., who were extremely anti-Indian in their perspectives and furthermore, there were also unavoidable limitations within the perspectives of an orientalist scholarship.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=375,376}} | |||

| == Last years and death == | == Last years and death == | ||

| Rajendralal |

Rajendralal Mitra spent the last years of his life at the Wards' Institution, ], which was his ''de facto'' residence after its closure.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=77}} Even in his last days, he was extensively involved with the Asiatic Society and was a member of multiple sub-committees. | ||

| At around 9:00 pm on 26 July 1891, Mitra died in his home after suffering intense bouts of fever. According to contemporary news reports, Mitra had endured these fevers for the last few years following a stroke that caused ] and grossly affected his health.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=94}} Numerous condolence meetings were held and newspapers were filled with obituaries.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=95}} A huge gathering took place at ] under the auspices of Lt. Gov. ] to commemorate Mitra as well as ], who also died around the same time, and was the first event of its type to be presided over by a Lieutenant Governor.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=95}} | |||

| ==Contemporaneous reception== | |||

| Numerous condolence meetings were held across different places and newspapers were filled with obituaries.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=95}} A huge gathering took place at the ] under the auspices of Lt. Gov. ] to commemorate Rajendralal as well as ] (who has recently expired) and was the first of its type to be ever presided by a Lieutenant Governor.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=95}} | |||

| Mitra's academic works along with his oratory, debating skills and miscellaneous writings, were extensively praised by his contemporaries and admired for their exceptionally clarity.{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=38,75,81}} | |||

| ] showered praise on Mitra, writing:<blockquote>He has edited Sanskrit texts after a careful collection of manuscripts, and in his various contributions to the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, he has proved himself completely above the prejudices of his class, freed from the erroneous views on the history and literature in India in which every Brahman is brought up, and thoroughly imbued with those principles of criticism which men like Colebrooke, Lassen and Burnouf have followed in their researches into the literary treasures of his country. His English is remarkably clear and simple, and his arguments would do credit to any Sanskrit scholar in England.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=9}} | |||

| ==Contemporary reception== | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| His academic works along with his oratory, debating skills and miscellaneous writings were extensively praised by his contemporaries and admired for their exceptionally clarity.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=38,75,81}} | |||

| Rabindranath Tagore said Mitra "could work with both hands. He was an entire association condensed into one man".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bose |first=Pradip Kumar |year=2006 |title=Health and Society in Bengal: A Selection From Late 19th Century Bengali Periodicals |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=N0VBDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT18 |publisher=SAGE Publishing India |page=17 |isbn=978-0-7619-3418-9 |access-date=4 November 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181107185240/https://books.google.com/books?id=N0VBDwAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&pg=PT18 |archive-date=7 November 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> ] had also praised Mitra's work as a historian.<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." /> | |||

| ] showered profuse praise on Rajendralal noting{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=9}}:-<blockquote>....He has edited Sanskrit texts after a careful collection of manuscripts, and in his various contributions to the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, he has proved himself completely above the prejudices of his class, freed from the erroneous views on the history and literature in India in which every Brahman is brought up, and thoroughly imbued with those principles of criticism which men like Colebrooke, Lassen and Burnouf have followed in their researches into the literary treasures of his country.His English is remarkably clear and simple, and his arguments would do credit to any Sanskrit scholar in England....</blockquote>Rabindranath Tagore commented of him being a Sabyasachi, who could work with both hands and was an association, condensed into one man.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| ] and ] also derived from |

Contemporaneous historians ] and ] were heavily influenced by Mitra. ] and ] also derived from his works.<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." />{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=18}} | ||

| == Legacy == | == Legacy == | ||

| Rajendralal has been widely viewed as the first modern historian of Bengal in that he applied a rigorous scientific methodology to the study of history.<ref name=":2" /><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.in/books?redir_esc=y&id=mWGgAAAAMAAJ|title=Evolution of Historiography in Modern India, 1900-1960: A Study of the Writing of Indian History by Her Own Historians|last=Mukhopadhyay|first=Subodh Kumar|date=2002|publisher=Progressive Publishers|year=|isbn=|location=|pages=23|language=en}}</ref> Those who preceded him including the likes of ], ], ] et al., despite well-aware of the modern concepts of mainly Western History, majorly depended upon translating and adopting European history-texts.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=376}} From a pan-Indian perspective, ] who trod a similar path of scientifical-historiography was one of his contemporaries.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=376}} | |||

| Rajendralal Mitra has been widely viewed as the first modern historian of Bengal who applied a rigorous scientific methodology to the study of history.<ref name=":2" /><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mWGgAAAAMAAJ|title=Evolution of Historiography in Modern India, 1900-1960: A Study of the Writing of Indian History by Her Own Historians|last=Mukhopadhyay|first=Subodh Kumar|year=2002|orig-year=First published 1981|edition=2nd|publisher=Progressive Publishers|page=23|oclc=60712586|quote="Rajendralal Mitra, the first scientific historian of modern India."}}</ref> He was preceded by historians including ], ], ], ], ] and ]; all of whom, despite being aware of the modern concepts of Western history, depended heavily upon translating and adopting European history texts with their own noble interpretations, and hence were not professional historians.<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." />{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=376}} From a pan-Indian perspective, ], who similarly used scientific historiography, was one of Mitra's contemporaries.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=376}} | |||

| He has influenced a generation of historians including ].{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=376}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=16}} Eminent ] Professor ] described him as "a great lover of ancient heritage, he took a rational view of ancient society...."<ref>{{cite book|title=]|last=Sharma|first=R.S.|publisher=]|year=2005|isbn=978-0-19-568785-9|authorlink=Ram Sharan Sharma}}</ref> | |||

| ] named Mitra as one of his primary influences.{{sfn|Sur|1974|p=376}}{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=16}} Mitra has been alluded to have triggered the golden age of Bengali historiography, that saw the rise of numerous stalwarts, including ], ], ], ] and ].<ref name="Bhattacharya 2015 p." /> Historian ] described Mitra as "a great lover of ancient heritage took a rational view of ancient society".<ref>{{cite book|title=India's Ancient Past|last=Sharma|first=R.S.|author-link=Ram Sharan Sharma|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2005|page=8|isbn=978-0-19-568785-9}}</ref> | |||

| His '''Sanskrit Buddhist Literature''<nowiki/>', was heavily utilised by Rabindranath Tagore for many episodes of his poems and plays.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.in/books?id=s5Up306hrBIC&lpg=PA32|title=Rabindranath Tagore: The Poet of India|last=Majumdar|first=A. K. Basu|date=1993|publisher=Indus Publishing|isbn=9788185182926|language=en}}</ref>{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=221,222}} A street in Kolkata is named after him.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://wikimapia.org/street/459895/Raja-Rajendra-Lal-Mitra-Road-Kol-700085|title=Raja Rajendra Lal Mitra Road Kol-700085 - Kolkata|website=wikimapia.org|language=en|access-date=2018-11-10}}</ref> | |||

| Mitra's "Sanskrit Buddhist Literature" was heavily used by Rabindranath Tagore for many episodes of his poems and plays.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=s5Up306hrBIC&pg=PA32|title=Rabindranath Tagore: The Poet of India|last=Majumdar|first=A. K. Basu|year=1993|publisher=Indus Publishing|isbn=978-81-85182-92-6|language=en|access-date=8 November 2018|page=32}}</ref>{{sfn|Ray|1969|pp=221,222}} A street in Calcutta adjoining Mitra's birthplace is named after him.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.mainstreamweekly.net/article7497.html|title=Gandhiji at the Dawn of Freedom |website=Mainstream Weekly|access-date=25 December 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181225175540/http://www.mainstreamweekly.net/article7497.html|archive-date=25 December 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| == Honors == | |||

| In 1863, the Calcutta University appointed him as a corresponding fellow and he played an important role in its education-reforms.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=68}} | |||

| In 1864, the German Oriental Society appointed him as a corresponding fellow.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=69}} In 1865, the Royal Academy of Science, Hungary appointed him as a foreign fellow. In 1865, the Royal Asiatic society of Great Britain appointed him as an honorary fellow.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=69}} In October 1867, the American Oriental Society appointed him as an honorary fellow.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=69}} In 1876, the ] honoured Mitra with a ]. | |||

| == Honours == | |||

| He was awarded with the honorary titles of Rai Bahadur in 1877, C.I.E in 1878 and Raja in 1888. Rajendralal had expressed displeasure about the awardings.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=76}} | |||

| In 1863, ] appointed Mitra as a corresponding fellow, where he played an important role in its education reforms,{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=68}} and in 1876, the university honoured Mitra with an ]. In 1864, the ] appointed him as a corresponding fellow.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=69}} In 1865, the ], appointed Mitra as a foreign fellow. In 1865, the ] appointed him as an honorary fellow.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=69}} In October 1867, the ] appointed him as an honorary fellow.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=69}} | |||

| Mitra was awarded with the honorary titles of ] in 1877, ] in 1878 and ] in 1888 by the British Government. Mitra had expressed displeasure about these awards.{{sfn|Ray|1969|p=76}} | |||

| ==Publications== | ==Publications== | ||

| Apart from very numerous contributions to the society's journal, and to the series of Sanskrit texts entitled "Bibliotheca indica," he published four separate works: | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=Prakrita Bhugol |date=1854 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.357417/page/n3/mode/2up |language=Bengali}} | |||

| *''The Antiquities of Orissa'' (2 vols, 1875 and 1880), illustrated with photographic plates | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=The Taittiriya Brahmana of the Black Yajur Veda, with the Commentary of Sayana Acharya (Vol. I) |date=1859 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.322382/page/n3/mode/2up |language=Sanskrit}} (Biblioteca Indica) | |||

| * ''Buddha Gaya : the hermitage of Sakya Muni'' (1878), a description of a holy place of Buddhism where Buddha attained Enlightenment. | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=Shilpik Darshan |date=1860 |publisher=Bidya Ratna Press |url=https://archive.org/details/bub_man_5e8fbd265a40619588deb965817c7c9d/page/n5/mode/2up |language=Bengali}} (For the Vernacular Literature Committee) | |||

| *a similarly illustrated work on ] (1878), the hermitage of Sakya Muni. | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=The Nitisara or The Elements of Polity by Kamandaki |date=1861 |publisher=Baptist Mission Press, Kolkata |url=https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.6283/page/n11/mode/2up |language=Sanskrit}} (Biblioteca Indica) | |||

| * ''Indo-Aryans'' (2 vols, 1881), a collection of essays dealing with the manners and customs of ]. | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=The Chhandogya Upanishad of the Sama Veda with extracts from the Commentary of Sankara Acharya, Translated from the Original Sanskrita |date=1862 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.142134/page/n1/mode/2up}} (Biblioteca Indica) | |||

| * ''The Sanskrit Buddhist Literature of Nepal'' (1882), a summary of the avadana-literature. | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=The Taittiriya Brahmana of the Black Yajur Veda, with the Commentary of Sayana Acharya (Vol. II) |date=1862 |url=https://archive.org/details/dli.ministry.30783/page/n1/mode/2up |language=Sanskrit}} (Biblioteca Indica) | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=Notices of Sanskrit MSS., Vol. I & II |date=1871 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.424347/page/n5/mode/2up}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=The Taittiriya Pratisakhya with the Commentary en titled the Tribhashyaratna |date=1872 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.292717/page/n3/mode/2up |language=Sanskrit}} (Biblioteca Indica) | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |last2=Vidyabhushana |first2=Harachandra |title=The Gopatha Brahmana of the Atharva Veda |date=1872 |publisher=Calcutta Asiatic Society of Bengal |url=https://archive.org/details/gopathabrahmanao00gopauoft/page/n3/mode/2up |language=Sanskrit}} (Biblioteca Indica) | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=Agni Purana: A Collection of Hindu Mythology and Traditions (Vol. I) |date=1873 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.486795/page/n1/mode/2up |language=Sanskrit}} (Biblioteca Indica) | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=The Antiquities of Orissa (Vol. 1) |date=1875 |publisher=Wyman, Calcutta |url=https://archive.org/details/dli.csl.7811/mode/2up}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=Notices of Sanskrit MSS., Vol. III & IV |date=1876 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.424348/page/n7/mode/2up}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=Agni Purana: A Collection of Hindu Mythology and Traditions (Vol. II) |date=1876 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.199554/page/n1/mode/2up |language=Sanskrit}} (Biblioteca Indica) | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=A Descriptive Catalogue of Sanskrit MSS. in the Library of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Part First: Grammar |date=1877 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.344897/page/n1/mode/2up}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=Buddha Gaya: The Hermitage of Sakya Muni |date=1878 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.17383/page/n3/mode/2up}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=Notices of Sanskrit MSS., Vol. V & VI |date=1880 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.23551/page/n5/mode/2up}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=A Catalogue of Sanskrit Manuscripts in the Library of His Highness the Maharaja of Bikaner |date=1880 |publisher=Baptist Mission Press |url=https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.552547/page/n5/mode/2up}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=The Vayu Purana: A System of Hindu Mythology and Tradition (Vol. I) |date=1880 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.553740/page/n7/mode/2up |language=Sanskrit}} (Biblioteca Indica) | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=The Antiquities of Orissa (Vol. II) |date=1880 |publisher=W. Newman, Calcutta |url=https://archive.org/details/dli.csl.7243/page/n1/mode/2up}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=Indo-Aryans: Contributions toward the Elucidation of their Ancient and Medieval History (Vol. 1) |date=1881 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.553194/page/n3/mode/2up}} {{cite book |title=(Vol. 2) |year=1881 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.537072/page/n7/mode/2up}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=The Lalita-Vistara, or Memoirs of the Early Life of Sakha Sinha, Translated from the Original Sanskrit |date=1881 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.196141/page/n5/mode/2up?}} (Biblioteca Indica) | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=The Sanskrit Buddhist Literature of Nepal |date=1882 |url=https://archive.org/details/sanskritbuddhistliteratureofnepalrajendralalmitraasiaticsociety1882_543_W/page/n1/mode/2up}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=Notices of Sanskrit MSS., Vol. VII |date=1884 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.322579/page/n5/mode/2up}} | |||

| *{{cite book |author1=Mitra, Rajendralal |title=Centenary Review of the Asiatic Society of Bengal |date=1885 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.533698/page/n5/mode/2up |chapter=Part I: History of the Society}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=Notices of Sanskrit MSS., Vol. VIII |date=1886 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.17383/page/n3/mode/2up}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=Ashtasāhasrikā : a collection of discourses on the metaphysics of the Mahāyāna School of the Buddhists, now first edited from Nepalese Sanskirt mss. |date=1888 |url=https://archive.org/details/b30094471/page/n3/mode/2up |language=Sanskrit}} (Biblioteca Indica) | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitra |first1=Rajendralal |title=The Taittiriya Brahmana of the Black Yajur Veda, with the Commentary of Sayana Acharya (Vol. III) |date=1890 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.487240/page/n3/mode/2up |language=Sanskrit}} (Biblioteca Indica) | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Mitter |first1=Raj Jogeshur |title=Speeches by Raja Rajendralala Mitra, L.L. D., C.I.E. |date=1892 |url=https://archive.org/details/speeches00mitr/page/n3/mode/2up}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

| == Major |

== Major sources == | ||

| {{refbegin}} | {{refbegin}} | ||

| *{{Cite journal|last=Sur|first=Shyamali| |

* {{Cite journal|last=Sur|first=Shyamali|year=1974|title=Rajendralal Mitra as a Historian : A Revaluation|journal=Proceedings of the Indian History Congress|volume=35|pages=370–378|jstor=44138803}} | ||

| *{{Cite book |

* {{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.297868|title=Rajendralal Mitra|last=Ray|first=Alok|publisher=Bagartha|year=1969|language=bn}} | ||

| *{{Cite book|url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.39571|title=Eminent Orientalists|chapter=Rajendralal Mitra|last=Iyengar|first=M.S. Ramaswami|date=1922}} | |||

| {{refend}} | {{refend}} | ||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Sister project links| wikt=no | commons=no | b=no | n=no | q=no | s=Author:Rajendralal Mitra | v=no | voy=no | species=no | d=q5989378}} | {{Sister project links| wikt=no | commons=no | b=no | n=no | q=no | s=Author:Rajendralal Mitra | v=no | voy=no | species=no | d=q5989378}} | ||

| * at '']'', Kolkata (IACS) | |||

| * | * | ||

| * ''Indo-Aryans: contributionts towards the elucidation of the Ancient and Medieval history'' (1881) | |||

| {{Authority control}} | {{Authority control}} | ||

| Line 164: | Line 169: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 170: | Line 175: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 13:21, 22 November 2024

Bengali scholar| This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. Please consider expanding the lead to provide an accessible overview of all important aspects of the article. (February 2019) |

| Raja Rajendralal Mitra | |

|---|---|

Raja Rajendralal Mitra Raja Rajendralal Mitra | |

| Born | (1822-02-16)16 February 1822 Calcutta, Bengal, British India |

| Died | 26 July 1891(1891-07-26) (aged 67) Calcutta, Bengal, British India |

| Nationality | British Indian |

| Occupation | Orientalist scholar |

Raja Rajendralal Mitra (16 February 1822 – 26 July 1891) was among the first Indian cultural researchers and historians writing in English. A polymath and the first Indian president of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, he was a pioneering figure in the Bengali Renaissance. Mitra belonged to a respected family of Bengal writers. After studying by himself, he was hired in 1846 as a librarian in the Asiatic Society of Bengal, for which he then worked throughout his life as second secretary, vice president, and finally the first native president in 1885. Mitra published a number of Sanskrit and English texts in the Bibliotheca Indica series, as well as major scholarly works including The antiquities of Orissa (2 volumes, 1875–80), Bodh Gaya (1878), Indo-Aryans (2 volumes, 1881) and more.

Early life

Raja Rajendralal Mitra was born in Soora (now Beliaghata) in eastern Calcutta (Kolkata), on 16 February 1822 to Janmajeya Mitra. He was the third of Janmajeya's six sons and also had a sister. Rajendralal was raised primarily by his widowed and childless aunt.

The Mitra family traced its origins to ancient Bengal; and Rajendralal further claimed descent from the sage Vishvamitra of Adisura myth. The family were members of the Kulin Kayastha caste and were devout Vaishnavs. Rajendralal's 4th great-grandfather Ramchandra was a Dewan of the Nawabs of Murshidabad and Rajendralal's great-grandfather Pitambar Mitra held important positions at the Royal Court of Ajodhya and Delhi. Janmajeya was a noted oriental scholar, who was revered in Brahmo circles and was probably the first Bengali to learn chemistry; he had also prepared a detailed list of the content of eighteen puranas. Raja Digambar Mitra of Jhamapukur was a relative of the family, as well.

Due to a combination of the spendthriftness of his grandfather Vrindavan Mitra and his father's refusal to seek paid employment, Rajendralal spent his early childhood in poverty.

Education

Rajendralal Mitra received his early education in Bengali at a village school, followed by a private English-medium school in Pathuriaghata. At around 10 years of age, he attended the Hindu School in Calcutta. Mitra's education became increasingly sporadic from this point; although he enrolled at Calcutta Medical College in December 1837—where he apparently performed well—he was forced to leave in 1841 after becoming involved in a controversy. He then began legal training, although not for long, and then changed to studying languages including Greek, Latin, French and German, which led to his eventual interest in philology.

Marriages

In 1839, when he was around 17 years old, Mitra married Soudamini. They had one child, a daughter, on 22 August 1844 and Soudamini died soon after giving birth. The daughter died within a few weeks of her mother. Mitra's second marriage was to Bhubanmohini, which took place at some point between 1860 and 1861. They had two sons: Ramendralal, born on 26 November 1864, and Mahendralal.

Asiatic Society

Mitra was appointed librarian-cum-assistant-secretary of the Asiatic Society in April 1846. He held the office for nearly 10 years, vacating it in February 1856. He was subsequently elected as the Secretary of the Society and was later appointed to the governing council. He was elected vice-president on three occasions, and in 1885 Mitra became the first Indian president of the Asiatic Society. Although Mitra had received little formal training in history, his work with the Asiatic Society helped establish him as a leading advocate of the historical method in Indian historiography. Mitra was also associated with Barendra Research Society of Rajshahi—a local historical society.

Influences and methodology

During his tenure at the Asiatic Society, Rajendralal came in contact with many notable persons and was impressed by two thought-streams of orientalist intellectualism. Noted scholars William Jones (the founder of Asiatic Society) and H.T. Colebrooke had propounded a theory of universalism and sought to make a comparative study of different races by chronicling history through cultural changes rather than political events whilst James Prinsep et al. sought greater cultural diversity and glorified the past. Mitra went on to utilize the tools of comparative philology and comparative mythology to write an orientalist narrative of the cultural history of the Indo-Aryans. Although Mitra subscribed to the philosophies of orientalism, he did not subscribe to blindly following past precedents and asked others to shun traditions, if they hindered the progress of the nation.

Historiography

Mitra was a noted antiquarian and played a substantial role in discovering and deciphering historical inscriptions, coins, and texts. He established the relationship between the Shaka era and Gregorian calendar, thus identifying the year of Kanishka's ascent to the throne, and contributed to an accurate reconstruction of the history of Medieval Bengal, especially that of the Pala and Sena dynasties, by deciphering historical edicts. He studied the Gwaliorian monuments and inscriptions, discovering many unknown kings and chieftains, and assigned approximate time spans to them. He was also the only historian among his contemporaries to assign a near-precise time frame to the rule of Toramana. Mitra's affinity for factual observations and inferences and dislike for abstract reasoning, in contrast with most Indo-historians of those days, has been favorably received in later years.

Cataloging, translation and commentary

As a librarian of the Asiatic Society, Rajendralal was charged with cataloging Indic manuscripts collected by the Pandits of the Society. He, along with several other scholars, followed a central theme of the European Renaissance that emphasized the collection of ancient texts (puthi) followed by their translation into the lingua franca. A variety of Indic texts, along with extensive commentaries, were published, especially in the Bibliotheca Indica series, and many were subsequently translated into English. Mitra's instructions for the Pandits to copy the texts verbatim and abide by the concept of varia lectio (different readings) has been favourably critiqued. Mitra was also one of the few archivists who emphasized the importance of cataloguing and describing all manuscripts, irrespective of factors like rarity.

Archaeology

Mitra did significant work in documenting the development of Aryan architecture in prehistoric times. Under the patronage of the Royal Society of Arts and the colonial government, Mitra led an expedition to the Bhubaneshwar region of Odisha in 1868–1869 to study and obtain casts of Indian sculptures. The results were compiled in The Antiquities of Orissa, which has since been revered as a magnum opus about Orissan architecture. The work was modelled on Ancient Egyptians by John Gardner Wilkinson and published in two volumes consisting of his own observations followed by a reconstruction of the socio-cultural history of the area and its architectural depictions. Along with Alexander Cunningham, Mitra also played an important role in the excavation and restoration of the Mahabodhi Temple. Another of his major works is Buddha Gaya: the Hermitage of Sakya Mani which collated the observations and commentaries of various scholars about Bodh Gaya.

These works, along with his other essays, contributed to a detailed study of varying forms of temple architecture across India. Unlike his European counterparts, who attributed the presence of nude sculptures in Indian temples to a perceived lack of morality in ancient Indian social life, Mitra correctly hypothesized the reasons for it.

A standard theme of Rajendralal's archaeological texts is the rebuttal of the prevalent European scholarly notion that India's architectural forms, especially stone buildings, were derived from the Greeks and that there was no significant architectural advancement in the Aryan civilization. He often noted that the architecture of pre-Muslim India is equivalent to the Greek architecture and proposed the racial similarity of the Greeks and the Aryans, who had the same intellectual capacity. Mitra often came into conflict with European scholars regarding this subject, such as his acrimonious dispute with James Fergusson. After Mitra criticized Fergusson's commentary about Odisa architecture in The Antiquities of Orissa, Fergusson wrote a book titled Archaeology in India With Especial Reference to the Work of Babu Rajendralal Mitra. While many of Mitra's archaeological observations and inferences were later refined or rejected, he was a pioneer in the field and his works were often substantially better than those of his European counterparts.

Linguistics

Rajendralal Mitra was the first Indian who tried to engage people in a discourse of the phonology and morphology of Indian languages, and tried to establish philology as a science. He debated European scholars about linguistic advances in Aryan culture and theorized that the Aryans had their own script that was not derived from Dravidian culture. Mitra also did seminal work on Sanskrit and Pali literature of the Buddhists, as well as on the Gatha dialect.

Vernacularization

Mitra was a pioneer in the publication of maps in the Bengali language and he also constructed Bengali versions of numerous geographical terms that were previously only used in English. He published a series of maps of districts of Bihar, Bengal, and Odisa for indigenous use that were notable for his assignment of correct names to even small villages, sourced from local people. Mitra's efforts in the vernacularization of western science has been widely acclaimed.

As a co-founder of the short-lived Sarasvat Samaj—a literature society set up by Jyotirindranath Tagore with help from the colonial government for publication of higher-education books in Bengali and enrichment of Bengali language in 1882—he wrote "A Scheme for the Rendering of European Scientific terms in India", which contains ideas for the vernacularization of scientific discourse. He was also a member of several other societies, including the Vernacular Literature Society, and Calcutta School-Book Society, which played important roles in the propagation of vernacular books, esp. in Bengali literature, and in Wellesley's Textbook Committee (1877). Many of his Bengali texts were adopted for use in schools and one of his texts on Bengali Grammar and his "Patra-Kaumudi" (Book of Letters) became widely popular in later times.

Publication of magazines

From 1851 onward, under a grant from the Vernacular Literature Society, Mitra started publishing the Bibhidartha Sangraha, an illustrated monthly periodical. It was the first of its kind in Bengal and aimed to educate Indian people in western knowledge without coming across as too rigid. It had a huge readership, and introduced the concept of literary criticism and reviews into Bengali literature. It is also notable for introducing Michael Madhusudan Dutt's Bengali works to the public.

Mitra retired from its editorship in 1856, citing health reasons. Kaliprasanna Singha took over the role. In 1861, the government compelled the magazine to withdraw from publication; then in 1863, Mitra started a similar publication under the name Rahasya Sandarbha, maintaining the same form and content. This continued for about five and a half years before closing voluntarily. Mitra's writings in these magazines have been acclaimed. He was also involved with the Hindoo Patriot, of which he held editorial duties for a while.

Socio-political activities

Rajendralal Mitra was a prominent social figure and a poster child of the Bengal renaissance. Close to contemporaneous thinkers including Rangalal Bandyopadhyay, Michael Madhusudan Dutt, Kishori Chand Mitra, Peary Chand Mitra, Ramgopal Ghosh, and Digambar Mitra, he partook in a wide range of social activities ranging from hosting condolence meetings to presiding over sabhas and giving political speeches. He held important roles in a variety of societies including the famed Tattwabodhini Sabha. He was an executive committee member of the Bethune Society, served as a translator for the Calcutta Photographic Society and was an influential figure in the Society for the Promotion of the Industrial Art, which played an important role in the development of voluntary education in Bengal.

Mitra wrote several essays about social activities. Describing widow-remarriage as an ancient societal norm, he opposed its portrayal as a corruption of Hindu culture and also opposed polygamy. He wrote numerous discourses on the socio-cultural history of the nation, including about beef consumption and the prevalence of drinking alcohol in ancient India-the latter at a time when Muslims were increasingly blamed for the social affinity for drinking. Mitra was generally apathetic towards religion; he sought the disassociation of religion from the state and spoke against the proposals of the colonial government to tax Indians to fund the spread of Christian ideologies.

From 1856 until its closure in 1881, Mitra was the director of the Wards' Institution, an establishment formed by the Colonial Government for the privileged education of the heirs of zamindars and other upper classes. He was active in the British Indian Association since its inception, serving as its president for three terms (1881–82, 1883–84, 1886–87) and vice-president for another three terms (1878–80, 1887–88, 1890–91). Several of his speeches on regional politics have also been recorded. Mitra was involved with the Indian National Congress, serving as the president of the Reception Committee in the Second National Conference in Calcutta and was also a Justice of the peace of the Calcutta Municipal Corporation for many years, having served as its commissioner from 1876.

Criticism

Despite the general acclaim that has met his works, Rajendralal Mitra has also been the subject of criticism. Despite his self-declared agnosticism towards Indian mythology and his criticism of Indians' obsession with the uncritical acceptance of the glory of their own past, his works have suffered from ethno-nationalist biases.