| Revision as of 03:14, 2 December 2006 editGeneral Disarray (talk | contribs)3,764 edits rv Cunado's vandalism 2nd back to compromise reached in discussion← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:51, 29 December 2024 edit undoCyrusGD (talk | contribs)239 edits Added linkTags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit App section source | ||

| (931 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2022}} | |||

| {{Bahá'í}} | |||

| {{Baháʼí sidebar}} | |||

| The ] has had challenges to leadership at the death of every head of the religion. The vast majority of Bahá'ís have followed a line of authority from ] to ] to ] to the ] to the ]. Divergences from this line of leadership have had relatively little success. Adherents.com reports that the Bahá'í Faith is "almost entirely contained within one very organized, hierarchical denomination, the Bahá'í Faith, based in Haifa, Israel".<ref>Adherents.com </ref> The smaller groups that have broken away from the main body have not attracted a sizeable following.<ref name="maceoin">], ''Encyclopædia Iranica'' , </ref> | |||

| The ] was formed in the late 19th-century ] by ], and teaches that an official line of succession of leadership is part of a divine ] that assures unity and prevents ].{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=114}}{{sfn|Stockman|2020|pp=36–37}} There are no major schisms in the Baháʼí Faith,{{sfn|Demmrich|2020}} and attempts to form alternative leadership have either become extinct with time or have remained in extremely small numbers that are shunned by the majority.{{sfn|McMullen|2000|p=195}}{{sfn|MacEoin|1988}}{{sfn|Stockman|2020|pp=36–37}} The largest extant sect is related to ]'s claim to leadership in 1960, which has continued with two or three groups numbering less than 200 collectively,{{sfn|Stockman|2013|p=25}} mostly in the United States.{{sfn|Warburg|2004|p=206}} | |||

| About a dozen efforts have been made to form sects in the history of the Baháʼí Faith.{{sfn|Stockman|2020|pp=36–37}} The first major challenge to leadership came after Baháʼu'lláh died in 1892, with ]'s half-brother ] opposing him. Later, ] faced opposition from his family, as well as some individual Baháʼís. When Shoghi Effendi passed in 1957, there was no clear successor, and the ] led a transition to the ], elected in 1963. This transition was opposed by Mason Remey, who claimed to be the successor of Shoghi Effendi in 1960, but was excommunicated by Hands of the Cause because his claim had no basis in authoritative Baháʼí writings.{{sfn|Gallagher|Ashcraft|2006|p=201}} Other, more modern attempts at schism have come from opposition to the Universal House of Justice and attempts to reform or change doctrine.{{sfn|Johnson|2020|loc=Ch. 11}} | |||

| Because the ] define a ] regarding succession which is intended to keep the Bahá'ís unified, challenges to legitimate succession are seen as very harmful. Claimants challenging the widely accepted succession have been expelled as ], though such claimants likewise regard the others in the same way. | |||

| Those that have been excommunicated have consistently protested against the majority group and, in some cases, claimed that the excommunicated represent the true Baháʼí Faith and the majority are ]s.{{sfn|Fussell|1973}}{{sfn|Johnson|2020|p=xxxvi}} Some Baháʼís have claimed that there have been no divisions in the Baháʼí Faith, or that none will survive or become a threat to the main body of Baháʼís.{{sfn|McMullen|2000|p=195}}{{sfn|Barrett|2001|pp=246-247}} From 2000-2020, twenty individuals were expelled by the Baháʼí Administration for Covenant-breaking.{{sfn|The World of the Bahá'í Faith… The Covenant|2022}} | |||

| A separate entry discusses the ]. | |||

| == |

==ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's ministry== | ||

| {{anchor|abdulbaha-ministry}} | |||

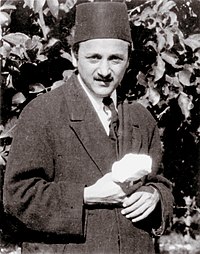

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Bahá'u'lláh remained in the Akka-Haifa area house arrest until his death in ]. According to the terms of ], his eldest son ] was named the centre of authority; ], the eldest son from Bahá'u'lláh's second marriage was assigned an inferior position. | |||

| Baháʼu'lláh remained in the Akka-Haifa area under house arrest until his death in 1892. According to the terms of ], his eldest son ] was named the centre of authority; ], the eldest son from Baháʼu'lláh's second wife, was assigned a secondary position.<ref>Baháʼu'lláh, ''Tablets of Baháʼu'lláh'', </ref> | |||

| With ʻAbdu'l-Bahá as the head of the Baháʼí community, soon Muhammad ʻAli started working against his elder brother, at first subtly and then in open opposition. Most members of the families of Baháʼu'lláh's second and third wives supported Muhammad ʻAlí; however, there were very few outside of Haifa who followed him.{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=252}} | |||

| {{cquote|The Will of the divine Testator is this: It is incumbent upon the ], the ] and My Kindred to turn, one and all, their faces towards the Most Mighty Branch .<ref>Bahá'u'lláh, ''Tablets of Bahá'u'lláh'', </ref>}} | |||

| Muhammad ʻAlí's machinations with the Ottoman authorities resulted in ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's re-arrest and confinement in ].{{sfn|Smith|2008|p=44}} They also caused the appointment of two official commissions of inquiry, which almost led to further exile and incarceration of ʻAbdu'l-Baha to North Africa. In the aftermath of the Young Turk revolution, Ottoman prisoners were freed thus ending the danger to ʻAbdu'l-Baha.{{sfn|Smith|2008|pp=43–44}} Meanwhile, ], a Syrian Christian, converted to the Baháʼí Faith, emigrated to the United States and founded the first American Baháʼí community.{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=218}} Initially, he was loyal to ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. With time Kheiralla began teaching that ʻAbdu'l-Baha was the return of Christ, and this was becoming the widespread understanding among the Baháʼís in the United States, despite ʻAbdu'l-Baha's efforts to correct the mistake.{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=218}}{{sfn|Smith|2004|pp=4, 7}} Later on, Kheiralla switched sides in the conflict between Baháʼu'lláh's sons and supported Mirza Muhammad ʻAlí. He formed the Society of Behaists, a religious denomination promoting Unitarian Bahaism in the U.S., which was later led by ], son of Mirza Muhammad ʻAlí, after he emigrated to the United States in June 1904 at the behest of his father.<ref>{{Cite journal | editor-last = Cole | editor-first = Juan R.I. | editor2-last = Quinn | editor2-first = Sholeh | editor3-last = Smith | editor3-first = Peter | editor4-last = Walbridge | editor4-first = John |title=Documents on the Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Movements |journal=Behai Quarterly |volume=8 |issue=2 |publisher=h-net.msu.edu |date=July 2004 |url=http://www.h-net.org/~bahai/docs/vol8/bq.htm |access-date=17 April 2010}}</ref> Muhammad ʻAlí's supporters either called themselves Behaists <ref name="Behai Quarterly">Shu'a'ullah, ''Behai Quarterly'' </ref> or "Unitarian Baháʼís".{{efn|Browne, . The reference appears to be to the ] theology of one god, rather than any identification with the ].}} From 1934 to 1937, Behai published ''Behai Quarterly'' a Unitarian Bahai magazine written in English and featuring the writings of Muhammad ʻAlí and various other Unitarian Bahais.{{sfn|Warburg|2004|p=64}} | |||

| Pursuant to his role as Centre of the Covenant, `Abdu'l-Bahá asserted absolute leadership. Soon Muhammad `Ali complained that `Abdu'l-Bahá was not sharing authority and started working against his elder brother. Most members of the families of Bahá'u'lláh's second and third wives supported Muhammad `Alí but there were very few outside of Haifa who followed him. Muhammad `Alí's supporters called themselves "Unitarian Bahá'ís".<ref>Browne, </ref> In Browne's "Materials" he translates Mirza Jawad's claims that the authoritities began investigating `Abdu'l-Bahá more strictly, because he was acting in an overly superior fashion. Sometime later it was said that Muhammad `Alí was plotting to have `Abdu'l-Bahá hanged for treason against the Ottoman authorities in ]. According to ], `Abdu'l-Bahá was due to be hung on ] near ], but upon hearing of his death warrant, ] pressured the British Cabinet to quickly capture the Haifa region from the Ottomans, and thereby rescued `Abdu'l-Bahá. | |||

| ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's response to determined opposition during his tenure was patterned on Baháʼu'lláh's{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.b}} example and evolved across three stages. Initially, like Baháʼu'lláh,{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.b}} he made no public statements but communicated with his brother Muhammad ʻAlí and his associates directly, or through intermediaries, in seeking reconciliation. When it became clear that reconciliation was not possible, and fearing damage to the community, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá wrote to the Baháʼís explaining the situation, identifying the individuals concerned and instructing the believers to sever all ties with those involved. Finally, he sent representatives to those areas most affected by the problem.{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.c}} | |||

| When `Abdu'l-Bahá died, ] went into great detail about how Muhammad `Alí had been unfaithful to the Covenant, labelling him a ], and appointing ] as leader of the Faith instead, with the title of Guardian. Much of `Abdu'l-Bahá's argument centred around Muhammad `Alí's apparently jealous nature and inability to remain submissive to `Abdu'l-Bahá, the designated leader of the religion. Here he first used the term ] and excommunicated members of Bahá'u'lláh's second and third wives' families. Whole books within Bahá'í literature have been printed to refute the claims of Muhammad `Alí. (Baluzi, Taherzadeh, etc.) This represented what is often described as the most testing time for the ]. | |||

| The function of these representatives was to explain matters to the Baháʼís and to encourage them to persevere in cutting all contact. Often these chosen individuals would have ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's authority to open up communications with those involved to try to persuade them to return. In Iran, such envoys were principally the four ] appointed by Baháʼu'lláh.{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.c}} | |||

| The schism caused by Muhammad `Alí does not exist anymore. In the ] area, the followers of Muhammad `Alí have been reduced to at most six families who have no common organized religious activities.<ref> by Margit Warburg ISBN 1-56085-169-4</ref> | |||

| ===Aftermath=== | |||

| ==Shoghi Effendi as Guardian of the Faith== | |||

| {{anchor|Aftermath}} | |||

| ===Appointment=== | |||

| When ʻAbdu'l-Bahá died, ] explained in some detail how Muhammad ʻAlí had been unfaithful to the Covenant, identifying him as a ] and appointing ] as leader of the Faith with the title of ]. Baháʼí authors such as Hasan Balyuzi and Adib Taherzadeh set about refuting the claims of Muhammad ʻAlí. This represented what is often described as the most testing time for the ].{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.c}} The Behaists rejected the authority of the ], claiming loyalty to the leadership succession as they inferred it from Baha'u'llah's ].<ref name="Behai Quarterly"/> | |||

| ] | |||

| At 24, ] was particularly young when he assumed leadership of the religion in 1921, as provided for by `Abdu'l-Bahá in his Will and Testament. He had received a Western education at the ] and later at ], ]. | |||

| This schism had very little effect. The claims were rejected by the vast majority of Baháʼís. Muhammad ʻAlí's supporters had mostly abandoned him by the time of his death in 1937.{{sfn|McMullen|2000|p=195}} In the ʻAkká area, the followers of Muhammad ʻAlí represented six families at most, they had no common religious activities,{{sfn|Warburg|2004|p=64}} and were almost wholly assimilated into Muslim society.{{sfn|MacEoin|1988}} | |||

| Muhammad-`Alí took the opportunity to revive his claim to leadership of the Bahá'í community. He forcibly seized the keys of the Tomb of Bahá'u'lláh at the ], expelled its keeper, and demanded that he be recognized by the authorities as the legal custodian of that property. But the Palestine authorities, after investigations, instructed the British officer in `Akká to deliver the keys into the hands of the keeper loyal to Shoghi Effendi. <ref>''God Passes By'', </ref> | |||

| ==Shoghi Effendi as Guardian== | |||

| ===Family Members Expelled=== | |||

| {{anchor|Shoghi}} | |||

| {{main|Covenant-breaking in Shoghi Effendi's immediate family}} | |||

| In 1932 Shoghi Effendi's great aunt, Bahiyyih Khanum, died. She was greatly respected and had instructed all to follow Shoghi Effendi, referring to `Abdu'l-Bahá's Will where it states: "For he is, after `Abdu'l-Bahá, the Guardian of the Cause of God, the ], the Hands (pillars) of the Cause and the beloved of the Lord must obey him and turn unto him...." After her death the other family members began to oppose and disobey Shoghi Effendi openly. | |||

| ===Appointment=== | |||

| Some family members disapproved of his marriage to a Westerner, ] - daughter of one of the foremost disciples of `Abdu'l-Bahá, in 1937. They claimed that Shoghi Effendi introduced innovations beyond the Iranian roots of the Faith. This gradually resulted in his siblings and cousins disobeying his instructions and marrying into the families of ]s, many of whom were expelled as Covenant-breakers themselves. However, these disagreements within Shoghi Effendi's family resulted in no attempts to create a schism around an alternative leader. At the time of his death in 1957, he was the only remaining male member of the family of Bahá'u'lláh who had not been expelled. Even his own parents had openly fought against him. | |||

| ] | |||

| At 24, ] was particularly young when he assumed leadership of the religion in 1921, as provided for by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in his Will and Testament. He had received a Western education at the ] and later at ], ]. | |||

| At this time Muhammad-ʻAlí revived his claim to leadership of the Baháʼí community.{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.d.iv}} He seized the keys of the Tomb of Baháʼu'lláh at the ], expelled its keeper, and demanded that he be recognized by the authorities as the legal custodian of that property. However, the Palestinian authorities, after having conducted some investigations, instructed the British officer in ʻAkká to deliver the keys into the hands of the keeper loyal to Shoghi Effendi.{{sfn|Effendi|1944|p=355}} | |||

| ===American Disputes=== | |||

| After the death of `Abdu'l-Bahá, ] questioned the Will's authenticity as early as 1926,<ref></ref> and openly opposed Shoghi Effendi's Guardianship, publishing several books on the subject. She wrote a letter to the United States Postmaster General and asked him, among other things, to prohibit the National Spiritual Assembly from "using the United States Mails to spread the falsehood that Shoghi Effendi is the successor of `Abdu'l-Bahá and the Guardian of the Cause."<ref>Taherzadeh, 1972, p. 347</ref> She also wrote a letter to the High Commissioner for Palestine; both of these letters were ignored. No permanent schism or alternative leader came of her ideas. | |||

| ===American disputes=== | |||

| Another division occurred primarily within the American Bahá'í community, which increasingly consisted of non-Persians with an interest in alternative spiritual pursuits. Many had been strongly attracted to the personality of `Abdu'l-Bahá and the spiritual teachings of the Bahá'í Faith. Some regarded it as an ecumenical society to which all persons of goodwill — regardless of religion — might join. When Shoghi Effendi made clear his position that the Bahá'í Faith was an independent religion with its own distinct administration through local and national spiritual assemblies, a few felt that he had overstepped the bounds of his authority. Most prominent among them was a New York group including ] and ] and ], which founded the "New History Society," and it's youth section, the ].<ref>Mirza Ahmad Sohrab, ''The Baha'i Cause'' </ref> Sohrab and the Chanlers refused to be overseen by the New York Spiritual Assembly, and were expelled by Shoghi Effendi as ]s. They argued that the expulsion was meaningless because they believed the faith could not be institutionalized. The New History Society published several works by Sohrab and Chanler and others. The New History Society attracted less than a dozen Bahá'ís, however its membership swelled to several thousand for a time. It is now defunct.<ref>''The Basis of the Bahá'í Community: A Statement Concerning the New History Society'' </ref> The Caravan House, aka Caravan Institute, later disassociated itself from the Bahá'í Faith, and now remains as an unrelated non-profit organization.<ref>Moojan Momen, ''The Covenant, and Covenant-breaker'', | |||

| After the death of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, ] questioned the Will's authenticity as early as 1926,{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.d.i}} and openly opposed Shoghi Effendi's Guardianship, publishing several books on the subject. She wrote a letter to the United States Postmaster General and asked him, among other things, to prohibit the National Spiritual Assembly from "using the United States Mails to spread the falsehood that Shoghi Effendi is the successor of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and the Guardian of the Cause." She also wrote a letter to the High Commissioner for Palestine; both of these letters were ignored. | |||

| See also New York Tax Exempt and NonProfit Organizations </ref> | |||

| Another division occurred primarily within the American Baháʼí community, which increasingly consisted of non-Persians with an interest in alternative spiritual pursuits. Many had been strongly attracted to the personality of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and the spiritual teachings of the Baháʼí Faith. Some regarded it as an ecumenical society which all persons of goodwill—regardless of religion—might join. When Shoghi Effendi made clear his position that the Baháʼí Faith was an independent religion with its own distinct administration through local and national spiritual assemblies, a few felt that he had overstepped the bounds of his authority. Most prominent among them was a New York group including ], ] and ], who founded the "New History Society", and its youth section, the ].{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.d.ii}}<ref>Mirza Ahmad Sohrab, ''The Baháʼí Cause'' </ref> Sohrab and the Chanlers refused to be overseen by the New York Spiritual Assembly, and were expelled by Shoghi Effendi as ]s.{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=325}} They argued that the expulsion was meaningless because they believed the faith could not be institutionalized. The New History Society published several works by Sohrab and Chanler and others. Sohrab accepted the legitimacy of Shoghi Effendi as Guardian, but was critical of the manner of his leadership and the methods of organizing the Baháʼí administration.{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=325}} The New History Society attracted fewer than a dozen Baháʼís, however its membership swelled to several thousand for a time. The New History Society was active until 1959 and is now defunct.{{sfn|Smith|2004|p=15}} The Caravan House, aka Caravan Institute, later disassociated itself from the Baháʼí Faith, and remained as an unrelated non-profit educational organization.{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§ G.2.d.ii}}<ref></ref> | |||

| == The founding of the Universal House of Justice == | |||

| All of the divisions of this period were short-lived and restricted in their influence.{{sfn|MacEoin|1988}} | |||

| ===Passing of Shoghi Effendi=== | |||

| {{main|Shoghi Effendi}} | |||

| When Shoghi Effendi died in ], he died without explicitly appointing a successor Guardian.<ref>''Ministry of the Custodians'', </ref> He had no children, and during his lifetime all remaining male descendants of Bahá'u'lláh had been ] as Covenant-breakers. | |||

| ===Family members expelled=== | |||

| Shoghi Effendi's appointed ] unanimously voted it was impossible to legitimately recognize and assent to a successor. The Bahá'í community was in a situation not dealt with in the provisions of the Will and Testament of `Abdu'l-Bahá. Furthermore, the ] had not yet been elected, which represented the only Bahá'í institution authorized to adjudicate on matters not covered by the sacred text. | |||

| {{Main article|Covenant-breaker}} | |||

| In 1932 Shoghi Effendi's great aunt, ], died. She was highly respected and had instructed all to follow Shoghi Effendi through several telegrams she had sent around the world announcing the basics of the provisions of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's will and was witness to the actions relatives took in violation of provisions of the will.<ref name="JKhanProphetDaughter123">{{cite book |last=Khan |first=Janet A. |year=2005 |title=Prophet's Daughter: The Life and Legacy of Bahíyyih Khánum, Outstanding Heroine Of The Baháʼí Faith |publisher=Baháʼí Publishing Trust |location=Wilmette, Illinois, USA |isbn=1-931847-14-2 |pages=123–4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-8W-2DjcShcC&pg=PA123}}</ref> Bahíyyih Khánum had devoted much of her life towards protecting the accepted leadership of the Baháʼí Faith and after Shoghi Effendi's appointment there was little internal opposition until after her death when nephews began to openly oppose Shoghi Effendi over Baháʼu'lláh's house in Baghdad.{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=G.2.d.iv}} | |||

| Some family members disapproved of his marriage to a Westerner, ]—daughter of one of the foremost disciples of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá—in 1937. They claimed that Shoghi Effendi introduced innovations beyond the Iranian roots of the Faith. This gradually resulted in his siblings and cousins disobeying his instructions and marrying into the families of ]s, many of whom were expelled as Covenant-breakers themselves. However, these disagreements within Shoghi Effendi's family resulted in no attempts to create a schism favouring an alternative leader. At the time of his death in 1957, he was the only remaining male member of the family of Baháʼu'lláh who had not been expelled. Even his own parents had openly fought against him.{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=G.2.d.iv}} | |||

| ==The founding of the Universal House of Justice== | |||

| To understand the transition following the death of Shoghi Effendi in 1957, an explanation of the roles of the Guardian, the Hands of the Cause, and the Universal House of Justice are useful. | |||

| {{anchor|HouseOfJustice}} | |||

| Shoghi Effendi died in 1957 without explicitly appointing a successor Guardian.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=169–170}} He had no children, and during his lifetime all remaining male descendants of Baháʼu'lláh had been ] as ]s.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=169–170}} He left no will.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=169–170}} Shoghi Effendi's appointed ] unanimously voted it was impossible to legitimately recognize and assent to a successor.{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.e}} The Baháʼí community was in a situation not dealt with explicitly in the provisions of the Will and Testament of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=169–170}} Furthermore, the ] had not yet been elected, which represented the only Baháʼí institution authorized to adjudicate on matters not covered by the religion's three central figures.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=175–177}} To understand the transition following the death of Shoghi Effendi in 1957, an explanation of the roles of the Guardian, the Hands of the Cause, and the Universal House of Justice is useful. | |||

| === |

===Guardianship=== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| {{ |

{{see also|Will and Testament of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá}} | ||

| Other than allusions in the writings of |

Other than allusions in the writings of Baháʼu'lláh to the importance of the ], the role of the Guardian was not mentioned until the reading of the Will and Testament of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Shoghi Effendi later expressed to his wife and others that he had no foreknowledge of the existence of the Institution of Guardianship, least of all that he was appointed as Guardian.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=356–357}} | ||

| ʻAbdu'l-Bahá warned the Baháʼís to avoid the problems caused by his half-brother ].{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=356–357}} He stipulated the criteria and form for selecting future Guardians, which was to be clear and unambiguous.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=169–170}} His will required that the Guardian appoint his successor "in his own life-time ... that differences may not arise after his passing".{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=169–170}} The appointee was required to be either the first-born son of the Guardian, or one of the ] (literally: Branches; male descendants of Baháʼu'lláh).{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=169–170}} Finally, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left a responsibility of ratifying the appointment to ], elected from all of the Hands.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=175–177}} | |||

| The |

The will also vested authority in the Guardian's appointed assistants, known as the ], giving them the right to "cast out from the congregation of the people of Bahá" anyone they deem in opposition to the Guardian.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=115–116}} | ||

| ===Relationship between the Guardianship and the Universal House of Justice=== | ===Relationship between the Guardianship and the Universal House of Justice=== | ||

| The |

The roles of the Guardianship and the Universal House of Justice are complementary, the former providing authoritative interpretation, and the latter providing flexibility and the authority to adjudicate on "questions that are obscure and matters that are not expressly recorded in the Book."{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=169–170}}{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=346–350}} The authority of the two institutions was elucidated by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in his will, saying that rebellion and disobedience towards either the Guardian or the Universal House of Justice, is rebellion and disobedience towards God.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=169–170}}{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=346–350}} Shoghi Effendi went into further detail explaining this relationship in ''The World Order of Baháʼu'lláh'', indicating that the institutions are interdependent.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=346–350}} | ||

| {{cquote|...The Guardian of the Cause of God, as well as the Universal House of Justice to be universally elected and established, are both under the care and protection of the Abha Beauty... Whatsoever they decide is of God. Whoso obeyeth him not, neither obeyeth them, hath not obeyed God; whoso rebelleth against him and against them hath rebelled against God; whoso opposeth him hath opposed God; whoso contendeth with them hath contended with God; whoso disputeth with him hath disputed with God; whoso denieth him hath denied God; whoso disbelieveth in him hath disbelieved in God; whoso deviateth, separateth himself and turneth aside from him hath in truth deviated, separated himself and turned aside from God.<ref>`Abdu'l-Bahá, The Will and Testament, </ref>}} | |||

| Shoghi Effendi went into further detail explaining this relationship in ''The World Order of Bahá'u'lláh'': | |||

| {{cquote|...Their common, their fundamental object is to insure the continuity of that divinely-appointed authority which flows from the Source of our Faith, to safeguard the unity of its followers and to maintain the integrity and flexibility of its teachings. Acting in conjunction with each other these two inseparable institutions administer its affairs, coordinate its activities, promote its interests, execute its laws and defend its subsidiary institutions. Severally, each operates within a clearly defined sphere of jurisdiction; each is equipped with its own attendant institutions -- instruments designed for the effective discharge of its particular responsibilities and duties. Each exercises, within the limitations imposed upon it, its powers, its authority, its rights and prerogatives... | |||

| Divorced from the institution of the Guardianship the World Order of Bahá'u'lláh would be mutilated and permanently deprived of that hereditary principle which, as `Abdu'l-Bahá has written, has been invariably upheld by the Law of God. 'In all the Divine Dispensations,' He states, in a Tablet addressed to a follower of the Faith in Persia, 'the eldest son hath been given extraordinary distinctions. Even the station of prophethood hath been his birthright.' Without such an institution the integrity of the Faith would be imperiled, and the stability of the entire fabric would be gravely endangered. Its prestige would suffer, the means required to enable it to take a long, an uninterrupted view over a series of generations would be completely lacking, and the necessary guidance to define the sphere of the legislative action of its elected representatives would be totally withdrawn. | |||

| Severed from the no less essential institution of the Universal House of Justice this same System of the Will of `Abdu'l-Bahá would be paralyzed in its action and would be powerless to fill in those gaps which the Author of the Kitáb-i-Aqdas has deliberately left in the body of His legislative and administrative ordinances.<ref>Shoghi Effendi, The World Order of Bahá'u'lláh, </ref>}} | |||

| ===Role of the Hands of the Cause=== | ===Role of the Hands of the Cause=== | ||

| {{anchor|RoleOfHands}} | |||

| {{Main|Hands of the Cause}} | |||

| {{Main article|Hands of the Cause}} | |||

| The 27 living Hands of the Cause (Hands), appointed for life by Shoghi Effendi and referred to by him as "the Chief Stewards of Bahá'u'lláh's embryonic World Commonwealth"<ref>Shoghi Effendi, ''Messages to the Bahá’í World: 1950–1957'', </ref> signed a unanimous proclamation on November 25, 1957, shortly after the passing of Shoghi Effendi, stating that he had died "without having appointed his successor"; that "it is now fallen upon us as Chief Stewards of the Bahá'í World Faith to preserve the unity, the security and the development of the Bahá'í World Community and all its institutions"; and that they would elect from among themselves nine Hands who would "exercise ... all such functions, rights and powers in succession to the Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith... as are necessary to serve the interests of the Bahá'í World Faith, and this until such time as the Universal House of Justice... may otherwise determine." This body of nine Hands became known as the ].<ref>''Ministry of the Custodians'', </ref> | |||

| Shortly after Shoghi Effendi's death, the 27 then-living Hands of the Cause (Hands) deliberated over whether or not they could legitimately consent to any successor.<ref name="Momen 89">{{Harvnb|Momen|Smith|1989|p=89}}</ref> Only two members present could translate between English and Persian.{{sfn|Gallagher|Ashcraft|2006|p=201}} Following these events '']'' magazine reported that there were debates about two possible candidates for Guardian.<ref>. '']''. 9 December 1957.</ref> | |||

| On 25 November 1957, the Hands signed a unanimous proclamation stating that he had died "without having appointed his successor"; that "it is now fallen upon us ... to preserve the unity, the security and the development of the Baháʼí World Community and all its institutions"; and that they would elect from among themselves nine Hands who would "exercise ... all such functions, rights and powers in succession to the Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith ... as are necessary to serve the interests of the Baháʼí World Faith, and this until such time as the Universal House of Justice ... may otherwise determine." This body of nine Hands became known as the Hands of the Cause in the Holy Land, sometimes referred to as the ].{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=117}} | |||

| For their authority, they referred to the ''Will and Testament of `Abdul-Bahá'' where it says "the Hands of the Cause of God must elect from their own number nine persons that shall at all times be occupied in the important services in the work of the Guardian of the Cause of God."() | |||

| That same day the Hands passed a unanimous resolution that clarified who would have authority over various executive areas.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=115–116}}{{efn|For their authority, the Custodians referred to the ''Will and Testament of ʻAbdul-Bahá'' which states that "the Hands of the Cause of God must elect from their own number nine persons that shall at all times be occupied in the important services in the work of the Guardian of the Cause of God."{{Harv|Hatcher|Martin|1998|p=190}}{{Harv|ʻAbdu'l-Bahá|1992|p=12}} See: Rabbani, ''Ministry of the Custodians'', 1992, Letter of 28 May 1960, to all National Spiritual Assemblies (pp. 204-206), Letter of 5 July 1960, to all National Spiritual Assemblies (pp. 208-209), Letter of 7 July 1960, to all Hands of the Cause, Cable of 26 July 1960, to all National Spiritual Assemblies (p.223), and Letter of 15 October 1960, to all National Spiritual Assemblies (pp. 231-236) In addition, the Guardian had written that the Hands had executive authority in carrying out his directives. {{Harv|Effendi|1982|pp=82–83}}}} Among these were: | |||

| That same day the Hands passed a unanimous resolution that clarified who would have authority over various executive areas. Among these were: | |||

| *"That the entire body of the Hands of the Cause, |

*"That the entire body of the Hands of the Cause, ... shall determine when and how the International Baháʼí Council shall pass through the successive stages outlined by Shoghi Effendi culminating in the election of the Universal House of Justice" | ||

| *"That the authority to expel violators from the Faith shall be vested in the body of nine Hands , acting on reports and recommendations submitted by Hands from their respective continents." |

*"That the authority to expel violators from the Faith shall be vested in the body of nine Hands , acting on reports and recommendations submitted by Hands from their respective continents." | ||

| In |

In their deliberations following Shoghi Effendi's passing they determined that they were not in a position to appoint a successor, only to ratify one, so they advised the Baháʼí community that the ] would consider the matter after it was established.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=175–177}} | ||

| In deciding when and how the ] would develop into the Universal House of Justice, the Hands agreed to carry out Shoghi Effendi's plans for moving it from the appointed council, to an officially recognized |

In deciding when and how the ] would develop into the Universal House of Justice, the Hands agreed to carry out Shoghi Effendi's plans for moving it from the appointed council, to an officially recognized Baháʼí Court, to a duly elected body, and then to the elected Universal House of Justice.<ref>See {{Harvnb|Rabbani|1992|p=37}} and {{Harvnb|Effendi|1971|pp=7–8}} </ref> In November 1959, referring to the goal of becoming recognized as a ] in Israel, they said: "this goal, due to the strong trend towards the ] in this part of the world, might not be achieved."<ref>See {{Harvnb|Rabbani|1992|p=169}} </ref><ref name="TCoB324">{{Harvnb|Taherzadeh|1992|p=324}}</ref> The recognition as a religious court was never achieved, and the International Baháʼí Council was reformed in 1961 as an elected body in preparation for forming the Universal House of Justice.{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=200}} The Hands of the Cause made themselves ineligible for election to both the council and the Universal House of Justice.{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=200}} | ||

| Upon the election of the Universal House of Justice |

Upon the election of the Universal House of Justice at the culmination of the ] in 1963, the nine Hands acting as interim head of the religion closed their office.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=175–177}} | ||

| ===Charles Mason Remey=== | ===Charles Mason Remey=== | ||

| <!--other pages link directly to this section. Please avoid |

<!--other pages link directly to this section. Please avoid changes to its title --> | ||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Mason Remey}} | |||

| Charles Mason Remey was among the Hands who signed the unanimous proclamations in 1957, acknowledging that Shoghi Effendi had died without having appointed his successor. He was among the ] elected to serve in the Holy Land as interim head of the Faith. | |||

| {{Main article|Mason Remey}} | |||

| On 8 April, ], Remey made a written announcement that he was the second Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith and explained his "status for life as commander in chief of Bahá’í affairs of the world" in this proclamation which he requested to be read in front of the annual US convention in ]. | |||

| Charles Mason Remey was among the Hands who signed the unanimous proclamations in 1957, acknowledging that Shoghi Effendi had died without having appointed his successor.{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.e}}{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=292}} He was also among the ] initially elected to serve in the Holy Land as interim head of the religion.{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=117}} | |||

| On 8 April 1960, Remey made a written announcement that he was the second Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith and explained his "status for life as commander in chief of Baháʼí affairs of the world" in this proclamation which he requested to be read in front of the annual US convention in ].{{sfn|Remey|1960|p=1}} | |||

| His claim was based on his having been appointed President of the first ] by Shoghi Effendi in 1951.<ref>''Messages to the Bahá'í World - 1950-1957'', </ref> The appointed council represented the first international Bahá'í body. It was to gain recognition as a religious court, be transformed into an elected body, and further effloresce into the Universal House of Justice, with the Guardian as its head. Remey believed that his appointment as the council's president meant he was the Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith: | |||

| He based his claim on his having been appointed President of the first ] by Shoghi Effendi in 1951.{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=292}} The appointed council represented the first international Baháʼí body. Remey believed that his appointment as the council's president meant that he was the Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith.{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=292}} The Hands of the Cause wrote regarding his reasoning on this point, "If the President of the International Baháʼí Council is ''ipso facto'' the Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith, then the beloved Guardian, himself, Shoghi Effendi would have had to be the President of this first International Baháʼí Council."{{sfn|Rabbani|1992|p=234}} Remey was appointed president of the council in March 1951,{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=199}}{{sfn|Effendi|1938|p=8}} then in December 1951 Remey was appointed a ].{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=292}}{{sfn|Effendi|1938|p=20}} A further announcement in March 1952 appointed several more officers to the Council and ] as the liaison between the Council and the Guardian.{{sfn|Effendi|1938|p=22}} | |||

| {{cquote|The Beloved Guardian chose me to be the President of the Bahá'í International Council that is according to his explanation the President of the Embrionic Universal House of Justice. (p. 6) | |||

| Regarding the authority of the Hands of the Cause, Remey wrote in his letter that the Hands "have no authority vested in themselves ... save under the direction of the living Guardian of the Faith".{{sfn|Remey|1960|p=5}} He further commanded the Baháʼís to abandon plans for establishing the Universal House of Justice.{{sfn|Remey|1960|pp=6–7}} | |||

| This is the only position suggestive of authority that Shoghi Effendi ever bestowed upon anyone, the only special and specific appointment of authority to any man ever made by him. (p. 2) | |||

| Remey never addressed the requirement that Guardians should be male-descendants of Baháʼu'lláh, of whom Remey was not. His followers later referred to letters and public statements of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá calling him "my son" as evidence that he had been implicitly adopted<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.charlesmasonremey.net/index.htm |title=Brent Mathieu, ''Biography of Charles Mason Remey'' |access-date=28 September 2006 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060318131148/http://www.charlesmasonremey.net/index.htm |archive-date=18 March 2006 |url-status=dead}}</ref> but these claims were almost universally rejected by the body of the Baháʼís.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=175–177}} | |||

| … I expect them to accept me without question as their Commander-in-Chief in all Bahá'í matters and to follow me so long as I live for I am the Guardian of the Faith — the Infallible Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith. (p. 8)<ref>Charles Mason Remey, ''Proclamation to the Bahá'ís of the World'', </ref>}} | |||

| In response, and after having made many prior efforts to convince Remey to withdraw his claim,<ref name="TCoB387">{{Harvnb|Taherzadeh|1992|p=387}}</ref><ref name="CoC370">{{Harvnb|Taherzadeh|2000|p=370}}</ref> the Custodians took action and sent a cablegram to the National Spiritual Assemblies on 26 July 1960.<ref>See {{Harv|Rabbani|1992|p=223}}</ref> Two days later, the Custodians sent Mason Remey a letter informing him of their unanimous decision to declare him a Covenant-breaker.{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=292}} They cited the Will and Testament of ʻAbdul-Bahá, the unanimous joint resolutions of 25 November 1957, and their authority in carrying out the work of the Guardian<ref name="LDG 82-83">See {{Harvnb|Effendi|1982|pp=82–83}} </ref> as their justification. Anyone who accepted Remey's claim to the Guardianship was also expelled.{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=292}} In a 9 August 1960 letter to the other Hands, the Custodians seem to acknowledge that Remey was not senile or unbalanced, but he was carrying out a ''"well thought out campaign"'' to spread his claim.{{sfn|Johnson|2020|p=34}} | |||

| The Hands of the Cause wrote regarding his reasoning, "If the President of the International Bahá'í Council is ipso facto the Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith, then the beloved Guardian, himself, Shoghi Effendi would have had to be the President of this first International Bahá'í Council."<ref>''Ministry of the Custodians,'' </ref> | |||

| Regarding the authority of the Hands of the Cause, Remey wrote in his letter to the convention that the Hands "have no authority vested in themselves... save under the direction of the living Guardian of the Faith."<ref>Charles Mason Remey, ''Proclamation to the Bahá'ís of the World'', </ref> He further ordered the Bahá'ís to abandon the plans for establishing the Universal House of Justice: | |||

| {{cquote|…All these plans of the Hands of the Faith for 1963 that are so absorbing and confusing to the people of the Faith must be dropped and stopped immediately. I am the only one who can command this situation so I have arisen to do so for I alone in all this world have been given the authority and the power to accomplish this. (p. 6) | |||

| …I now command the Hands of the Faith to stop all of their preparations for 1963 and furthermore I command all believers both as individual Bahá'ís and as assemblies of Bahá'ís to immediately cease cooperating with and giving support to this fallacious program for 1963. (p. 7) <ref>Charles Mason Remey, ''Proclamation to the Bahá'ís of the World'', </ref>}} | |||

| In his proclamation, Remey never addressed the requirement that Guardians should be male-descendants of Bahá'u'lláh, of which Remey was not biologically. His followers later referred to letters and public statements of `Abdu'l-Bahá calling him "my son" as evidence that he had been implicitly adopted.<ref>Brent Mathieu, ''Biography of Charles Mason Remey'', </ref> | |||

| After having made many prior efforts to convince Remey to withdraw his claim; and citing the Will and Testament of `Abdul-Bahá and the unanimous joint resolutions of November 25, 1957, as their authority, the ] expelled Remey and his small group of followers for Covenant-breaking. Two days after sending a Cablegram to the National Spiritual Assemblies the Custodians sent Mason Remey the following letter: | |||

| :To the Hand of the Cause Mason Remey | |||

| :April 30,1960 | |||

| :Dear Mason: | |||

| :For your information we quote below the text of a cable sent by the Hands in the Holy Land to the Continental Hands and to all National Assemblies on April 28: | |||

| ::Deeply regret necessity inform Bahá'í world Hand Cause Mason Remey now asserting he is Guardian Faith Stop This preposterous claim clearly contrary Sacred Texts can only be regarded as evidence condition profound emotional disturbance Stop Call upon believers everywhere join Hands Holy Land complete repudiation this misguided action Stop Share this message friends. | |||

| :Before their departure for Canada and the United States, ] and Mrs. Collins participated in the decision to take this action, making it unanimous. | |||

| :With heartfelt regret, | |||

| :Faithfully yours, | |||

| :HANDS OF THE CAUSE IN THE HOLY LAND <ref>''Ministry of the Custodians'', </ref></blockquote> | |||

| Remey went on to establish what came to be known as the Orthodox Bahá'ís Under the Hereditary Guardianship, which later broke into several other divisions based on succession within the group that followed Remey. | |||

| ===Decision of the Universal House of Justice=== | ===Decision of the Universal House of Justice=== | ||

| ] was first elected in 1963. Its seat (pictured) was constructed in 1982.]] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{ |

{{Main article|Universal House of Justice}} | ||

| The Baháʼí institutions and believers around the world pledged their loyalty to the ], who dedicated the next few years to completing ] ], culminating with the election of the Universal House of Justice in 1963. It was at this time the ] officially passed their authority as the head of the Faith to the Universal House of Justice,{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=117}}<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|2008|p=68}}</ref> which soon announced that it could not appoint or legislate to make possible the appointment of a second Guardian to succeed Shoghi Effendi.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=346–350}} | |||

| {{cquote|After prayerful and careful study of the Holy Texts... and after prolonged consideration of the views of the Hands of the Cause of God residing in the Holy Land, the Universal House of Justice finds that there is no way to appoint or to legislate to make it possible to appoint a second Guardian to succeed Shoghi Effendi.<ref>The Universal House of Justice, Letter of 6 October, 1963, ''Messages from the Universal House of Justice, 1963-1986'', </ref>}} | |||

| A short time later it elaborated on the situation in which the Guardian would die without being able to appoint a successor, saying that it was an obscure question not covered by Baháʼí scriptures, that no institution or individual at the time could have known the answer, and that it therefore had to be referred to the Universal House of Justice, whose election was confirmed by references in Shoghi Effendi's letters that after 1963 the Baháʼí world would be led by international plans under the direction of the Universal House of Justice.<ref>The Universal House of Justice, Letter of 9 March 1965, ''Messages from the Universal House of Justice, 1963-1986'', </ref> | |||

| A short time later it elaborated on the situation: | |||

| {{cquote|... This situation, in which the Guardian died without being able to appoint a successor, presented an obscure question not covered by the explicit Holy Text, and had to be referred to the Universal House of Justice. The friends should clearly understand that before the election of the Universal House of Justice there was no knowledge that there would be no Guardian. There could not have been any such foreknowledge, whatever opinions individual believers may have held. Neither the Hands of the Cause of God, nor the International Bahá'í Council, nor any other existing body could make a decision upon this all-important matter. Only the House of Justice had authority to pronounce upon it. | |||

| ... | |||

| The Guardian had given the Bahá'í world explicit and detailed plans covering the period until Ridvan 1963, the end of the Ten Year Crusade. From that point onward, unless the Faith were to be endangered, further divine guidance was essential. This was the second pressing reason for the calling of the election of the Universal House of Justice. The rightness of the time was further confirmed by references in Shoghi Effendi's letters to the Ten Year Crusade's being followed by other plans under the direction of the Universal House of Justice.<ref>The Universal House of Justice, Letter of 9 March, 1965, ''Messages from the Universal House of Justice, 1963-1986'', </ref>}} | |||

| ===A break in the line of Guardians=== | ===A break in the line of Guardians=== | ||

| Mason Remey and his successors asserted that a living Guardian is essential for the Baháʼí community, and that the Baháʼí writings required it. The basis of these claims were almost universally rejected by the body of the Baháʼís,{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=175–177}} for whom the restoration of scripturally sanctioned leadership of the Universal House of Justice proved more attractive than the claims of Mason Remey.{{sfn|Momen|Smith|1989|p=76}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Mason Remey and his successors asserted that a living Guardian is essential for the Bahá'í community, and that the Bahá'í Writings required it. The Universal House of Justice addressed this issue early after its election. | |||

| {{cquote|Future Guardians are clearly envisaged and referred to in the Writings. But there is nowhere any promise or guarantee that the line of Guardians would endure forever; on the contrary there are clear indications that the line could be broken. Yet, in spite of this, there is a repeated insistence in the Writings on the indestructibility of the Covenant and the immutability of God's Purpose for this Day.<ref>The Universal House of Justice, Letter of 7 December 1969, ''Messages from the Universal House of Justice, 1963-1986'', </ref>}} | |||

| The Universal House of Justice specifically refers to of the ] as evidence that |

The House commented that its own authority was not dependent on the presence of a Guardian,{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=346–350}} and that its legislative functioning was unaffected by the absence of a Guardian.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=169–170}} It stated that in its legislation it would be able to turn to the mass of interpretation left by Shoghi Effendi.{{sfn|Smith|2000|pp=169–170}} The Universal House of Justice addressed this issue further early after its election clarifying that "there is nowhere any promise or guarantee that the line of Guardians would endure forever; on the contrary there are clear indications that the line could be broken."<ref name="TCoB390">{{Harvnb|Taherzadeh|1992|p=390}}</ref><ref>The Universal House of Justice, Letter of 7 December 1969, ''Messages from the Universal House of Justice, 1963-1986'', </ref>{{efn|The Universal House of Justice specifically refers to of the ] as evidence that Baháʼu'lláh anticipated that the line of Guardians was not guaranteed forever by providing for the disposition of the religion's endowments in the absence of the ].{{Harv|Taherzadeh|1992|p=390}} See also Notes and of the ''Kitáb-i-Aqdas'', pp. 196-197.}} | ||

| == |

== Mason Remey as second Guardian == | ||

| ] | |||

| Among the Bahá'ís who accepted Mason Remey as the second Guardian, several further divisions have occurred. All those that profess belief in Mason Remey as the second Guardian do not accept the ] established in 1963, but amongst themselves have a variety of opinions on legitimacy and the proper succession of authority. Remey's followers began to split even before his death in 1974.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| All Baháʼís who professed belief in Mason Remey as the second Guardian implicitly did not accept the ] established in 1963, and are shunned by members of the mainstream Baháʼí Faith. Likewise, Remey at one point declared that the Hands of the Cause were Covenant-breakers, that they lacked any authority without a Guardian, that those following them "should not be considered Baháʼís", and that the Universal House of Justice that they helped elect in 1963 was not legitimate.{{sfn|Johnson|2020|p=35}}<ref>{{Cite book|last=Martinez|first=Hutan Hejazi|url=https://scholarship.rice.edu/bitstream/handle/1911/61990/3421441.PDF?sequence=1&isAllowed=y|title=Baha'ism: History, Transfiguration, Doxa|publisher=RICE UNIVERSITY, HOUSTON, TEXAS|year=2010|isbn=|location=USA|pages=106}}</ref> | |||

| |author= Warburg, Margit | |||

| |year= 2004 | |||

| |title= Bahá'í, Studies in Contemporary Religion | |||

| |publisher= Signature Books | |||

| |id= ISBN 1560851694 | |||

| |url= http://www.signaturebooks.com/excerpts/Baha'i.htm | |||

| }}</ref> Some of these divisions are described below. In 1997 the Universal House of Justice issued to all the National Spiritual Assemblies covering what happened to these groups. | |||

| Remey attracted about 100 followers in the United States and a few others in Pakistan and Europe.{{sfn|Gallagher|Ashcraft|2006|p=201}} Remey maintained his claim to Guardianship, and went on to establish what came to be known as the Orthodox Baháʼís Under the Hereditary Guardianship, which later broke into several other divisions based on succession disputes within the groups that followed Remey.{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.e}}{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=292}} Although initially disturbing, the mainstream Baháʼís paid little attention to his movement within a few years. As of 2006 his followers represent two or three groups that maintain little contact with each other, comprising at most a few hundred members collectively.{{sfn|Gallagher|Ashcraft|2006|p=201}}{{sfn|Stockman|2020|pp=36–37}} | |||

| The ''Encyclopædia Iranica'' reports the following: | |||

| {{cquote|Remey died in 1974, having appointed a third Guardian, but the number of adherents to the Orthodox faction remains extremely small. Although successful in Pakistan, the Remeyites seem to have attracted no followers in Iran. Other small groups have broken away from the main body from time to time, but none of these has attracted a sizeable following.<ref name="maceoin" />}} | |||

| Initially, Remey had followers in Pakistan, India, the United States, and parts of Europe. He settled in Florence, Italy, until the end of his life. From there he appointed three local spiritual assemblies in ], ], and ], then organized the election of two National Assemblies - in the United States and Pakistan.{{sfn|Johnson|2020|p=40}} | |||

| After declaring himself to be the Guardian, Remey began making published comments that he was in fact the first Guardian rather than Shoghi Effendi, and referring to "violations of the Faith that were made unwittingly by Shoghi Effendi". In 1966 he declared that "the only thing for the second Guardian to do, to set matters aright, is to discard all which Shoghi Effendi did and to institute a New Faith which shall be the Orthodox Faith... the establishment of the TRUE Bahá'í Faith which has not yet been established in the world."<ref>The Universal House of Justice, letter of 4 June 1997, </ref> | |||

| In 1964 the Santa Fe assembly filed a lawsuit against the National Spiritual Assembly (NSA) of the Baháʼís of the United States to receive the legal title to the Baháʼí House of Worship in Illinois, and all other property owned by the NSA. The NSA counter-sued and won.<ref name="1966 court"> District Court, N.D. Illinois, E. Div. No. 64 C 1878. Decided 28 June 1966</ref> The Santa Fe assembly lost the right to use the term "Baháʼí" in printed material. Remey then changed the name of his sect from "Baháʼís Under the Hereditary Guardianship" to "Abha World Faith" and also referred to it as the "Orthodox Faith of Baháʼu'lláh". In 1966, Remey asked the Santa Fe assembly to dissolve, as well as the second International Baháʼí Council that he had appointed with Joel Marangella, residing in France, as president.{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.e}} | |||

| Some of his supporters, particularly Marangella, declared him to be ] in old age.<ref>Moojan Momen, ''The Covenant, and Covenant-breaker'', | |||

| See also Brent Mathieu, ''Biography of Charles Mason Remey'' </ref> He was largely abandoned by the time of his death, at the age of 100, and was buried without religious rites.<ref>The Universal House of Justice, ''Mason Remey and Those Who Followed Him'', </ref> | |||

| Beginning in 1966-67, Remey was abandoned by almost all of his followers.{{sfn|Johnson|2020|p=44}} The followers of Mason Remey were not organized until several of them began forming their own groups based on different understandings of succession, even before his death in 1974.{{sfn|Barrett|2001}}{{sfn|Warburg|2004}} The majority of them claimed that Remey was showing signs of senility.{{sfn|Johnson|2020|p=44}} The small Baháʼí sects that adhere to Remey as Guardian are now largely confined to the United States,{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.e}} and have no communal religious life.{{sfn|Warburg|2004|p=06}} | |||

| ===Orthodox Bahá'í Faith=== | |||

| {{Main|Orthodox Bahá'í Faith}} | |||

| ] accept ] as the Third Guardian; and believe he was the successor of Charles Mason Remey. | |||

| ===Orthodox Baháʼí Faith=== | |||

| Marangella had been President of the National Spiritual Assembly of France in 1961, which was the only NSA to accept Remey as the Second Guardian. When this happened, the ] declared certain members of the NSA of France to be ]s, and sent one of the Hands to change the locks on the French National Bahá'í Center. The Custodians were able to gain control of the National Bahá'í Center; including the funds and mailing lists, and the great majority of French Bahá'ís sided with the Custodians. Donald Harvey and Jacques Soghomonian were amongst the members of the NSA of France declared as covenant-breakers by the Hands of the Cause. | |||

| {{Main article| Orthodox Baháʼí Faith}} | |||

| In 1961 Joel Marangella received a letter from Remey, and a note that, "in or after 1963. You will know when to break the seal."{{sfn|Johnson|2020|p=61}} In 1964 Remey appointed members to a second International Baháʼí Council with Marangella as president, significant due to Remey's claim to Guardianship being based on the same appointment. In 1965 Remey activated the council, and in 1966 wrote letters passing the "affairs of the Faith" to the council, then later dissolving it. In 1969 Marangella made an announcement that the letter of 1961 was Remey's appointment of him as the third Guardian, and that he had been the Guardian since 1964, invalidating Remey's pronouncements from that point forward.{{sfn|Johnson|2020|pp=60–65}} | |||

| Marangella gained the support of most of Remey's followers,{{sfn|Johnson|2020|p=60}} who came to be known as Orthodox Baháʼís.{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=292}} Membership data is scarce. One source estimated them at no more than 100 members in 1988,{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=G.2.e}} and the group claimed a United States membership of about 40 in a 2007 court case.<ref>, US District Court for Northern District Court of Illinois Eastern Division, Civil Action No. 64 C 1878: Orthodox Baháʼí Respondents' Surreply Memorandum to NSA's Reply Memorandum, p2 para 2 line 15</ref> Joel Marangella died in San Diego, California on 1 September 2013. An unverified website claiming to represent Orthodox Baháʼís indicates followers in the United States and India, and a fourth Guardian named Nosrat’u’llah Bahremand.<ref></ref> | |||

| After Mason Remey made his proclamation he appointed a second International Bahá'í Council; with Marangella as President, and 8 vice presidents. Remey insisted that these members not meet in the same city, nor be on the same airplane, at the same time; for fear that if something happened the line of Guardians would cease. In ] Remey gave Marangella a sealed envelope, with instructions to open it when the time was right. In ] Mason Remey called for the Council to become active. Marangella then opened the sealed letter, which was a hand-written note by Mason appointing Marangella as his successor. Marangella looks upon that time as the time of his official appointment. Remey then changed his mind and deactivated the International Bahá'í Council. Remey's behavior became very disjointed after that time; with some of his followers (including Marangella) concluding that Remey had gone senile. In ] Remey appointed Donald Harvey as his successor without excommunicating Marangella. Marangella proclaimed himself the Third Guardian in ]; saying that Remey was no longer mentally able to function as Guardian. He also claimed that when Remey activated the Council he ceased to be the Guardian at that moment, since, Marangella claimed, there couldn't be two Guardians alive at the same time. Remey did not relinquish his title as Guardian, but he did not "declare" Marangella a covenant-breaker either. | |||

| ===Harvey, Soghomonian, and Yazdani=== | |||

| The Orthodox Bahá'í Community under the leadership of Marangella continued into the 21st century. | |||

| Donald Harvey was appointed by Remey as "Third Guardian" in 1967.{{sfn|Smith|2000|p=292}} This group does not use a formal name but "Universal Faith and Revelation of Baháʼu'lláh" and "Baháʼís loyal to the fourth Guardian" have been used by its adherents.{{sfn|Johnson|2020|p=89}} Donald Harvey never gained much of a following.{{sfn|Johnson|2020|p=95}} | |||

| Although no membership data has ever been made public, most estimate the community as less than 1000 adherents.{{uncited}} Websites representing the group claim followers in the United States and India, and messages from Joel Marangella indicate that he resides in ].<ref>See message posted 30 July, 2006</ref> | |||

| Francis Spataro of New York City, who supported Donald Harvey's claim as Remey's successor, independently organized "The Remey Society" after losing favor with Harvey. Spataro had a newsletter with about 400 recipients and in 1987 published a biography of Charles Mason Remey.{{sfn|Spataro|1987}} In 1995 Francis Spataro became an ] priest and left the Baháʼí religion altogether. | |||

| ===Bahá'ís Under the Provisions of the Covenant=== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Main|Bahá'ís Under the Provisions of the Covenant}} | |||

| In 1963 Remey set up a National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of the United States of America, which lost a legal battle for naming rights<ref>United States Patent Quarterly, | |||

| Volume 150, </ref> and therefore changed its name to the "National Spiritual Assembly... under the Hereditary Guardianship." Among the members elected to the National Assembly were ] and Reginald King, who both went on to develop groups of their own based on their individual beliefs regarding succession of leadership. After the dissolving of their National Assembly in 1964, Jensen moved to Missoula, Montana. In 1969 he was convicted of "a lewd and lascivious act" upon a 15-year-old female patient <ref>''State v. Jensen'', 153 Mont. 233, 455 P.2d 631 (Montana, 1969). </ref>, and served four years of a 20 year sentence in the Montana State Prison. | |||

| After Harvey's death in 1991, leadership of this group went to Jacques Soghomonian, a resident of Marseilles, France.{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.e}} Soghomonian died in 2013 and passed the successorship to E.S. Yazdani.{{sfn|Johnson|2020|pp=100–101}} | |||

| It was in prison that Jensen claimed to be visited by an angel, and converted several inmates to his ideas of being the "Establisher" of the Bahá'í Faith. According to Jensen, this title signified a status higher than that of the Guardian, but lower than a ]. After the death of Remey he founded the ] (BUPC), with an emphasis on natural and manmade disasters predicted in the Bible, prophecies he believed were encoded in the ], and that the Guardians could only be from Bahá'u'lláh's lineage of ]. | |||

| ===Leland Jensen=== | |||

| Jensen received national media coverage for apocalyptic predictions he was making in the early 80's which included giving specific dates (]). In 1991 he set up the ] (sIBC), which he intended would go on to become a world court, followed by an elected council, then the elected Universal House of Justice with the Guardian as its president and executive.<ref>See sIBC by-laws on </ref> He believed the guardian is the sign to recognize the true ], and that the Universal House of Justice in Haifa is flawed and fallible, as it is without a living guardian/executive, and by his intrepretations not elected per Shoghi Effendi's instructions. Jensen claimed that Remey's adopted son ] (Pepe) was the only valid appointment of Remey's, since neither of his other two appointees were sons. Believing Pepe was the third Guardian, Jensen invited him to be the council's president, which Pepe declined, and a long series of debates ensued. Pepe died in 1994. After the death of Jensen in 1996 the leadership of the BUPC passed to the sIBC, who remained believing that there was a Guardian who would make himself known. | |||

| {{Main article|Leland Jensen}} | |||

| Leland Jensen accepted Remey's claim to the Guardianship and later left the group. In 1969 he was convicted of "a lewd and lascivious act" for sexually molesting a 15-year-old female patient,<ref>, 455 P.2d 631 (Montana, 1969)</ref> and he served four years of a twenty-year sentence in the Montana State Prison. It was in prison that Jensen converted several inmates to his ideas of being what he called the "Establisher" of the Baháʼí Faith. After being paroled in 1973 and before Remey's death, Jensen formed an apocalyptic cult called the '''Baháʼís Under the Provisions of the Covenant''' (BUPC).{{sfn|Balch|1997|p=271}} Membership in his group peaked at 150-200 leading up to Jensen's prophecy of a nuclear holocaust for 29 April 1980, but the disconfirmation caused most of his followers to abandon him.{{sfn|Balch|1997|p=271}} | |||

| Jensen's chosen successor to the Guardianship was Remey's adopted son Pepe, a role that Pepe rejected, and Jensen died in 1996 with ambiguous leadership for his few remaining followers, who fractured in 2001 when one of them claimed to be the Guardian.{{sfn|Hyslop|2004}} Adherents were mostly concentrated in ].{{sfn|Balch|1997|p=271}} | |||

| A controversy broke the BUPC into schism in 2001 when ], a council member and close companion of Jensen, announced that he was the fourth Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith, and president of the sIBC. The majority members of the sIBC opposed Chase's claim, while Chase asserted that the sIBC members' failure to recognize him as the Guardian of the Faith amounted to ]. The resulting and other various criticisms are elaborated upon in ]. | |||

| ===Reginald ("Rex") King=== | |||

| Membership data is not available for the BUPC. According to community websites, some reside in Montana and Alaska, with a headquarters in ]. The highest estimate gives them at "1,000 or so" before the division in 2001.<ref>See from bahai-library.com</ref> | |||

| Rex King was elected to Remey's NSA of the United States with the most votes, and soon came into conflict with Remey. In 1969 he traveled to Italy with the hope of having Remey pass affairs over to him, but instead was labeled with the "station of satan".{{sfn|Johnson|2020|pp=75–76}} King then encouraged Marangella to open the sealed letter from Remey and supported his claim, but soon took issue with the way Marangella was interpreting scripture.{{sfn|Johnson|2020|p=77}} King rejected all claimants to the Guardianship after Shoghi Effendi including Remey. He claimed that he, Rex King, was a "regent" pending the emergence of the second Guardian who was in "occultation". Hardly anyone followed King.{{sfn|Johnson|2020|p=83}} He called his group the Orthodox Baháʼí Faith under the Regency. King died in 1977 and appointed four of his family as a council of regents, who later changed their name to "Tarbiyat Baha'i Community".{{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.e}}{{sfn|Johnson|2020|p=78}} There are no size estimates from independent sources, but they maintain a website and appear to be a small group of mostly Rex King's family that maintained some activity into the early 2000s. | |||

| === |

===Size and demographics=== | ||

| The following quotes from various sources describe the relative size and demographics of those who followed Mason Remey. | |||

| ] | |||

| The '''Orthodox Bahá'í Faith Under the Regency''' was founded by Reginald King, who was a very successful Bahá'í teacher who had converted hundreds to the Faith. When Remey declared himself the Second Guardian in 1960, King accepted him, and was elected to become the first Secretary of the National Assembly set up by Remey in 1963. | |||

| {{quote |text=the Orthodox Baha'i Faith, a group that claims to have active centers in Great Britain, Germany, Pakistan and the United States. |author=Anita Fussell, writing for the Lincoln Journal Star (18 March 1973) |title="Orthodox Baha'i: A Minority Viewpoint"{{sfn|Fussell|1973}} }} | |||

| After conflicts with several of Remey's followers, including Marangella, King decided that "neither Mason Remey nor Joel Marangella had in truth ever been guardians... because of the lack of lineal descendancy". What Remey had actually been, King said, was "a regent", and King came to the realization that he himself "was in actuality the Second Regent...." King's argument was that Remey was senile in old age and didn't know what he was doing. Following his death in ], King left leadership of the community to a Council of Regents, who reorganized as the Tarbiyat Bahá'í Community. | |||

| {{quote |text=It is impossible to say how many believers there were on the eve of April 29, 1980, but roughly 150 people in Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, and Arkansas made plans to enter fallout shelters ... On the night of April 28, about eighty believers met at a potluck feast in Missoula for the last time before Armageddon ... On May 16 the Missoula group finally gathered for its first feast since April 29. Thirty-six believers attended ... almost all the believers outside of Montana eventually rejected 's teachings. Everyone in the Arkansas group defected, as did most of the believers in Colorado and Wyoming. To our knowledge, only three members of the Colorado group remained steadfast by the end of the summer, and possibly two in Wyoming ... the size of 's active following remains small |author=Balch et al. |title="When the bombs drop" (April 1983){{sfn|Balch|1983|pp=132,133,136,138,139}} }} | |||

| The Regency Bahá'ís do not claim the authority to declare ], so they try to freely associate with other Bahá'ís. The Council of Regents, which consists of King's family, tries to "maintain the integrity of the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh until such time as the Second Guardian makes himself known and claims his rightful office."<ref> of the Tarbiyat Bahá'í Community</ref> They also still maintain that "the Faith will never be permanently split into factions or denominations as has happened in all previous religions", with an emphasis on ''permanently''. Membership figures are not published for the Tarbiyat Bahá'í Community. They appear to be restricted to a single group in ]. | |||

| {{quote |text=Remey died in 1974, having appointed a third Guardian, but the number of adherents to the Orthodox faction remains extremely small. Although successful in Pakistan, the Remeyites seem to have attracted no followers in Iran. Other small groups have broken away from the main body from time to time, but none of these has attracted a sizeable following. |author=] |title="Bahai and Babi Schisms" (1988){{sfn|MacEoin|1988}} }} | |||

| ===The Remey Society=== | |||

| Francis Spataro of New York City, a supporter of Harvey, independently organized "The Remey Society". Spataro published books about Charles Mason Remey, and at one time had a newsletter with about 400 recipients. But Spataro began to preach that Charles Mason Remey was a "Prophet"; this was blasphemous to Bahá'ís, and Harvey then cut all ties to Spataro, who continued to promote the life and works of Charles Mason Remey. In 1995 Francis Spataro became an Old Catholic priest and left the Bahá'í religion altogether. The Remey Society is now extinct. | |||

| {{quote |text=They call themselves Orthodox Bahais, and their following is small – a mere 100 members, with the largest congregation, a total of 11, living in Roswell, N.M. |author=Nancy Ryan, writing for the Chicago Tribune (10 June 1988){{sfn|Ryan|1988}} }} | |||

| ===The Man=== | |||

| '''The House of Mankind and the Universal Palace of Order''' followed Jamshid Ma'ani and John Carré, but appear now to be defunct. In the early 1970s a Persian man named Jamshid Ma'ani claimed he was "The Man"; or a new ]. He gained a few dozen Iranian Bahá'í followers. John Carré heard of Jamshid, and wrote a book about him; trying to get other Bahá'ís to accept him as a new Manifestation. Carré even invited "The Man" to live in his home in California, but soon concluded, after living with "The Man" for four months, that "The Man" was not at all godly or spiritual and certainly not a Manifestation of God. "The Man" went back to Iran, and Carré ended all association with him. Carré then continued as an "independent Bahá'í" and eventually wrote a book that proclaimed a new Bahá'í Prophet (minor prophet but not a Manifestation) would arise in the year 2001. A Bahá'í from North Carolina named Eric Stetsen wrote an online book in the same style of Bahá'u'lláh; proclaiming (in 2001) that he was that "Prophet". However, Stetson concluded about a year or so later that he was not a "Prophet" and that he had been mistaken about the Bahá'í Faith. Stetson lost faith in Bahá'u'lláh, and became a born-again Christian. A copy of Carré's book outlining his beliefs is maintained online by an ex-Bahá'í.<ref>John Carré, ''The Alif of the Greatest Name BHA’''</ref> | |||

| {{quote |text=Rejected by his fellow Hands and the overwhelming majority of Bahá'ís, Remey was expelled from the Bahá'í Faith. Nevertheless, his claim did gain significant minority support in some countries, notably France, the United States and Pakistan. However, Remey's followers soon became divided into a number of antagonistic factions, and by the time of his death (in 1974), the number of Bahá'ís who recognized his claims had greatly diminished. A few Remeyite splinter-groups continue to operate in the United States |author=Momen & Smith |title="The Bahá'í Faith 1957-1988" (1989){{sfn|Momen|Smith|1989}} }} | |||

| ===Bahá'í Loyal to the Fourth Guardian=== | |||

| After Harvey's death in ], leadership devolved to Jacques Soghomonian of France. There are several dozen followers of Jacques Soghomonian throughout the world; mostly in the U.S., who believed he is the Fourth Guardian; since he was the chosen successor of Donald Harvey. However, Soghomonian has resisted efforts by his small band of followers to organize or to actively proselytize. Soghomonian apparently believes that the mainstream ] will one day "see the light" and reinstate the Guardianship with himself or (more likely) one of his successors as Guardian; and thus there is no need for two competing organizations. Soghomonian believes that organization is not important, but what is important is to assure that the Guardianship continues, and thus the living Guardian needs only one follower (to act as successor) to continue the line of Guardians who shall one day, perhaps far in the future, return to Head the Bahá'í Faith worldwide. Soghomonian's most active and prolific follower seems to be Brent Reed; a former member of first the mainstream Bahá'í Faith, and later the Orthodox Bahá'í Faith who now follows Soghomonian. Reed manages the ''Heart of the Bahá'í Faith'' newsgroup online. Although the followers of Jacques Soghomonian have no formal organization, Brent Reed has coined the name "Bahá'ís Loyal to the Fourth Guardian, Jacques Soghomonian". | |||

| {{quote |text=Remey succeeded in gathering a few supporters, mainly in the United States, France, and Pakistan ... The followers of Remey have decreased in importance over the years, especially as they fragmented into contending factions ... number no more than one hundred ... Small Remeyite groups are now confined to a few states in the United States. |author=] |title="The Covenant, and Covenant-breaker" (1995){{sfn|Momen|1995|loc=§G.2.e}} }} | |||

| ==Conclusion== | |||

| One key Bahá'í doctrine is that the Faith cannot break into sects, Bahá'u'lláh and `Abdu'l-Bahá having gone to some trouble to guard against the possibility. An obvious question then arises concerning the divisions described on this page. Outright opponents of the Bahá'í Faith have latched on to the divisions described on this page as evidence of the falsehood of Bahá'í claims and beliefs. | |||

| {{quote |text=By the end of the 1970s Jensen also had attracted followers in Wyoming, Colorado, and Arkansas. Since 1980 membership in the BUPC has fluctuated considerably, but it probably never exceeded 200 nationwide, despite Jensen's claims of having thousands of followers around the world. In 1994, the last year for which we have a membership list, there were only sixty-six members in Montana and fewer than twenty in other states. The Wyoming and Arkansas contingents disbanded after the 1980 disconfirmation, but new groups were formed in Minnesota and Wisconsin ... By 1990 the group probably had fewer than 100 members nationwide ... the defection rate accelerated in the 1990s |author=Balch et al. |title="Fifteen Years of Failed Prophecy" (Routledge, 1997){{sfn|Balch|1997|pp=271,280}} }} | |||

| However, the Bahá'í Writings do in fact envision that challenges to the authority of its successorship will occur but indicate that any divisions would not be permanent nor affect the "vast body of adherents".<ref>"A schism, a permanent cleavage in the vast body of its adherents, they could never create." </ref> The fact that there is even a process for expelling ] is seen as further evidence for the eventuality of some challenges to its leadership occurring. | |||

| {{quote |text=There are a few hundred Americans who claim to follow Mason Remey |author=Peter Terry |title="Truth Triumphs" (1999){{sfn|Terry|1999}} }} | |||

| The generality of Bahá'ís tend to point out that, while small groups or individuals have left the Faith, or been told to leave, these have not been as successful attracting followers nor had as widespread an effect, as the mainstream Bahá'í community. Indeed, they assert, the vast majority of such schismatic groups are already extinct and those remaining have very few followers, especially when contrasted with the Bahá'í Faith's population, now numbering about six million.<ref>See ]</ref> Members of many of the smaller groups described here have a similar view, claiming the Faith is experiencing a temporary division which will certainly be healed, though their beliefs on the manner of its resolution vary. | |||