| Revision as of 00:35, 12 March 2020 view sourceGyrofrog (talk | contribs)Administrators57,042 edits + volume needed← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:28, 30 December 2024 view source Srich32977 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers300,271 edits cleanupTags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit App full source | ||

| (756 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Ethnic or pan-ethnic identifier used to refer to Ethiopians and Eritreans}} | ||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Infobox ethnic group | {{Infobox ethnic group | ||

| | group = Habesha |

| group = Habesha | ||

| | native_name = {{langx|gez|ሐበሠተ|translit=Ḥäbäśät}}<br />{{langx|am|ሐበሻ|translit=Häbäša}}<br />{{langx|ti|ሓበሻ|translit=Ḥabäša}} | |||

| | population = est. 112,438,531+ <ref>https://data.worldbank.org/country/ethiopia</ref> | |||

| | image = | |||

| <ref>https://data.worldbank.org/country/eritrea</ref> | |||

| | languages = ] | |||

| | popplace = | |||

| | religions = '''Predominately:'''<br/>] ]<br/>'''Minorities:'''<br/>], ] Christianity (]) and ] (]) | |||

| | region1 = National Origin:<br> | |||

| {{flagcountry|Ethiopia}} - ]<br>{{flagcountry|Eritrea}} - ]<br> | |||

| {{collapsible list | |||

| |titlestyle=background: transparent; text-align: left; font-weight: normal; line-height: normal; | |||

| |title={{nowrap|Sub-National Regions:}} | |||

| |] ] | |||

| |] ] | |||

| |] ] | |||

| |] ] | |||

| |] ] | |||

| |] ] | |||

| |] ] | |||

| |] ] | |||

| |] ] | |||

| |] ] |] ] | |||

| |] ] | |||

| |] ] | |||

| |] ] | |||

| |] ]-] | |||

| |] ] | |||

| |] ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| ---- | |||

| Diaspora Communities: | |||

| <br> | |||

| {{flag|United States}}<ref name="Terrazas">{{Cite web |first=Aaron Matteo |last=Terrazas |title=Beyond Regional Circularity: The Emergence of an Ethiopian Diaspora |date=June 2007 |url=http://www.migrationinformation.org/Profiles/display.cfm?ID=604 |publisher=] |accessdate=2011-11-25}}</ref><ref name="Amharu">United States Census Bureau 2009-2013, Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over: 2009-2013, USCB, 30 November 2016, | |||

| <https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html>.</ref> <br> | |||

| {{Flag|Israel}}<ref name="The Ethiopian Population In Israel">]: </ref><ref name="Anbessa Tefera 2007 p.73">Amharic-speaking Jews component 85% from ]; Anbessa Tefera (2007). "Language". ''Jewish Communities in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries - Ethiopia''. Ben-Zvi Institute. p.73 (Hebrew)</ref> <br> | |||

| {{Flag|Saudi Arabia}}<ref name="Terrazas"/> <br> | |||

| {{Flag|Lebanon}}<ref name="Terrazas"/> <br> | |||

| {{Flag|Italy}}<ref name="Terrazas"/><ref name="Italia">{{cite web|title=Istat.it|url=http://demo.istat.it/str2017/|publisher=Statistics Italy}}</ref> <br> | |||

| {{flag|United Kingdom}}<ref name=BBC>{{cite web|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/london/content/articles/2005/05/27/ethiopian_london_feature.shtml|title=Ethiopian London|publisher=]|accessdate=2008-12-06}}</ref><ref>pp, 25 (2015) United Kingdom. Available at: https://www.ethnologue.com/country/GB (Accessed: 30 November 2016).</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.ethnologue.com/country/GB|title=United Kingdom|website=Ethnologue.com|accessdate=26 August 2017}}</ref> <br> | |||

| {{flagcountry|Germany}}<ref name="De">{{cite web|title=Anzahl der Ausländer in Deutschland nach Herkunftsland|url=https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1221/umfrage/anzahl-der-auslaender-in-deutschland-nach-herkunftsland/|publisher=Das Statistik Portal}}</ref><ref group="Note">Roughly half of the Eritrean diaspora</ref><ref>Amharas are estimated to be the largest ethnic group of estimated 20.000 Ethiopian Germans|https://www.giz.de/fachexpertise/downloads/gtz2009-en-ethiopian-diaspora.pdf {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181004233553/https://www.giz.de/fachexpertise/downloads/gtz2009-en-ethiopian-diaspora.pdf |date=2018-10-04 }}</ref> <br> | |||

| {{flagcountry|Sweden}}<ref name="Se">{{cite web|title=Foreign-born persons by country of birth, age, sex and year|url=http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101E/FodelselandArK/?rxid=1bcec35a-5bd2-4a4a-9609-668463972a1c|publisher=Statistics Sweden}}</ref> <br> | |||

| {{flagcountry|Djibouti}} <br> | |||

| {{flagcountry|Norway}}<ref name="Norw">{{cite web|title=Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents|url=https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/statistikker/innvbef|publisher=Statistics Norway}}</ref> <br> | |||

| {{Flagcountry|Canada}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/tbt-tt/Rp-eng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=103001&PRID=10&PTYPE=101955&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2011&THEME=90&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=|title=2011 Census of Canada: Topic-based tabulations – Detailed Mother Tongue (232), Knowledge of Official Languages (5), Age Groups (17A) and Sex (3) for the Population Excluding Institutional Residents of Canada and Forward Sortation Areas, 2011 Census|first=Government of Canada, Statistics|last=Canada|website=12.statcan.gc.ca|accessdate=26 August 2017|date=2013-02-05}}</ref><ref>Statistics Canada, 2011 Census of Population, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-314-XCB2011032</ref><ref>Anon, 2016. 2011 Census of Canada: Topic-based tabulations | Detailed Mother Tongue (232), Knowledge of Official Languages (5), Age Groups (17A) and Sex (3) for the Population Excluding Institutional Residents of Canada and Forward Sortation Areas, 2011 Census. Www12.statcan.gc.ca. Available at: <http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/tbt-tt/Rp-eng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=103001&PRID=10&PTYPE=101955&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2011&THEME=90&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=> .</ref><ref>Immigrant languages in Canada. 2016. Immigrant languages in Canada. Available at: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/98-314-x/98-314-x2011003_2-eng.cfm. .</ref> <br> | |||

| {{flagcountry|Kenya}} <br> | |||

| {{flagcountry|Somalia}} <br> | |||

| {{flagcountry|Netherlands}}<ref name="Netherl">{{cite web|title=Population by migration background|url=http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/publication/?DM=SLEN&PA=37325eng&D1=a&D2=a&D3=0&D4=0&D5=71&D6=a&LA=EN&HDR=T&STB=G2,G1,G3,G5,G4&VW=T|publisher=Statistics Netherlands}}</ref> <br> | |||

| {{flagcountry|Denmark}}<ref name="Denm">{{cite web|title=Population by country of origin|url=http://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1280|publisher=Statistics Denmark}}</ref> <br> | |||

| ] ] ] | |||

| <br> | |||

| {{flagcountry|Australia}}<ref>{{cite web|publisher=Australian Bureau of Statistics|date=2014|title=The People of Australia Statistics from the 2011 Census, Cat. no. 2901.0, ABS|url=https://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/research/people-australia-2013-statistics.pdf|accessdate=2017-08-26|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170417222156/https://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/research/people-australia-2013-statistics.pdf|archive-date=2017-04-17|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>Australian Bureau of Statistics 2014, The People of Australia Statistics from the 2011 Census, Cat. no. 2901.0, ABS, 30 November 2016, <https://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/research/people-australia-2013-statistics.pdf {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170417222156/https://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/research/people-australia-2013-statistics.pdf |date=2017-04-17 }}>.</ref><ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170417222156/https://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/research/people-australia-2013-statistics.pdf |date=17 April 2017 }}</ref> <br> | |||

| {{flagcountry|Egypt}} <br> | |||

| {{flagcountry|Finland}}<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/fi/StatFin/StatFin__vrm__vaerak/statfin_vaerak_pxt_031.px/?rxid=726cd24d-d0f1-416a-8eec-7ce9b82fd5a4 |title=Archived copy |access-date=2019-05-02 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180626001544/http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/fi/StatFin/StatFin__vrm__vaerak/statfin_vaerak_pxt_031.px/?rxid=726cd24d-d0f1-416a-8eec-7ce9b82fd5a4 |archive-date=2018-06-26 |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| | pop1 = * | |||

| | languages = ], ], and other languages adopted by the diaspora. | |||

| | religions = Religions<ref>{{cite book|last1=Trimingham|first1=J.|title=Islam in Ethiopia|date=2013|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1136970221|page=23|url=https://www.google.com/books?id=UfrcAAAAQBAJ|accessdate=19 September 2016}}</ref><ref name="Pew">{{cite web|title=Religious Composition by Country, 2010-2050|url=http://www.pewforum.org/2015/04/02/religious-projection-table/2050/percent/all/|publisher=Pew Research Center|accessdate=26 October 2017}}</ref><ref name=Religion-2007>, Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency (accessed 6 May 2009)</ref> | |||

| ---- | |||

| Predominantly: ] {{!}} ] (] - ]) · ] (]) · ] (] - ]) | |||

| ---- | |||

| Minority: ]-]; ]-] (ethno-religious group); "Traditional Faiths". | |||

| | native_name = ({{lang-gez|ሓበሻ, ሐበሻ<br>|translit=Ḥabäša, Habesha, Abesha}}) | |||

| | native_name_lang = | |||

| | related-c = | |||

| | image = | |||

| | flag = | |||

| | flag_caption = | |||

| | Map = | |||

| | related_groups = | |||

| | region2 = {{collapsible list | |||

| |titlestyle=background: transparent; text-align: left; font-weight: normal; line-height: normal; | |||

| |title={{nowrap|Pre-Diaspora Ethnic Groups:}} | |||

| |], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], Bena, ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]/], Dime, ], ], ], Fedashe, ] (Ethiopian Jews), ], ], ], ], ], ] (Gofa People), ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], Koyego, ], Kusumie, ], ], ], ], Mareqo, Mashola, ], Mere people, Messengo, Mossiye, ], ], Nao, ], ], ], ], ], ], Qewama, She, Shekecho, ], ], ]/Upo, ], ], ] (]), ], ], ] ], ], ], ], Zeyese, ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| }} | |||

| ---------- | |||

| {{collapsible list | |||

| |titlestyle=background: transparent; text-align: left; font-weight: normal; line-height: normal; | |||

| |title={{nowrap|Post-Diaspora Ethnic Groups:}} | |||

| |] (Oromo Australian) | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| | (and other ]) | |||

| '''Habesha peoples''' ({{langx|gez|ሐበሠተ}}; {{langx|am|ሐበሻ}}; {{langx|ti|ሓበሻ}}; commonly used exonym: '''Abyssinians''') is an ethnic or ] identifier that has been historically employed to refer to ] and predominantly ] peoples found in the highlands of ] and ] between ] and ] (i.e. the modern-day ], ], ] peoples) and this usage remains common today. The term is also used in varying degrees of inclusion and exclusion of other groups. | |||

| }} | |||

| | pop2 = * | |||

| }} | |||

| ] | |||

| '''Habesha peoples ('''{{lang-gez|ሓበሻ, ሐበሻ|translit=Ḥabäša, Habesha, Abesha}}; or rarely used exonyms, '''Abyssinian people''' or {{lang-gr|Αἰθίοψ|translit=Aithiops ("Ethiopian")}}<ref>Hatke, George (2013). {{ISBN|978-0-8147-6066-6}}.</ref>) is a common ] and ] term used to refer to both ] and ] as a whole.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3">Goitom, M. (2017). "'Unconventional Canadians': Second-generation 'Habesha' youth and belonging in Toronto, Canada." ''Global Social Welfare, 4''(4), 179–190. doi: ...</ref> Conservatively-speaking with a narrow archaic definition, the ]-speaking and ]-speaking ] inhabiting the highlands of ] and ] were considered the core linguistically, culturally and ancestrally related ethnic groups that historically constituted the pan-ethnic group Habesha peoples, but in a broader contemporary sense includes all<ref>Oliphant, S. M. (2015). ''The impact of social networks on the immigration experience of ethiopian women'' (Order No. 3705725). Available from Ethnic NewsWatch; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1691345929).</ref> Ethiopian-Eritrean ethnic groups.<ref name="miran">{{cite book|first=Jonathan|last=Miran|title=Red Sea Citizens: Cosmopolitan Society and Cultural Change in Massawa|page=282|year=2009|publisher=Indiana University Press|isbn=9780253220790|url=https://www.google.com/books?id=PMFVeWTWF0YC&lpg=PA282&pg=PA282#v=onepage&q&f=false |quote='Abyssinian,' a common appellation of the Semitic-speaking people inhabiting the highlands of Ethiopia or Eritrea.|accessdate=14 August 2017}}</ref><ref name=":0"/> Population groups that make up the Habesha peoples trace their culture and ancestry back to the Kingdom of ], the ], and the various constituent kingdoms and predecessor states of the ] in the ].<ref name="Z2-4" /> Some Scholars have classified the ] and the ] as "Abyssinians proper" under an ultra-neo-conservative theory postulated by a few western practitioners of race biology and domestic ethnonationalistic political parties but not widely accepted by the general public or by most relevant scholars indigenous to the region.<ref name=":2" /><ref>{{cite book|last1=Levine|first1=Donald|title=Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society|publisher=University of Chicago Press|page=18|url=https://books.google.com.et/books?id=TtmFQejWaaYC&pg=PA19#v=onepage&q=%22Abyssinians%20proper%2C%20the%22&f=false|accessdate=28 December 2016|isbn=9780226475615|date=May 2000}}</ref><ref name="Y6">Marvin Lionel Bender : Oxford University Press, (1976) pp 26</ref><ref name="Y5">Paul B. Henze : Rand, (1985) pp 8</ref><ref name="CIAeth">{{cite web|title=CIA World Factbook - Ethiopia|url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/et.html|publisher=CIA|accessdate=15 August 2017|url-status=live|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110406115512/https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/et.html |archivedate=6 April 2011}}</ref>{{Synthesis-inline|date=March 2020|talk=Synthesis, POV}} | |||

| == |

== Etymology == | ||

| The oldest reference to Habesha was in second or third century ] engravings as {{transliteration|gez|Ḥbśt}} or {{transliteration|gez|Ḥbštm}} recounting the South Arabian involvement of the ] ("king") ] of ḤBŠT.<ref name="Munro-Hay 1991 39">{{cite book|title=Aksum: A Civilization of Late Antiquity|last=Munro-Hay|first=Stuart|publisher=]|year=1991|isbn=978-0748601066|page=39}}</ref> The term appears to refer to a group of peoples, rather than a specific ethnicity. Another Sabaean inscription describes an alliance between Shamir Yuhahmid of the ] and King ] of ḤBŠT in the first quarter of the third century.<ref name="Munro-Hay 1991 39"/> However, South Arabian expert Eduard Glaser claimed that the Egyptian hieroglyphic ''ḫbstjw'', used in reference to "a foreign people from the incense-producing regions" (i.e. ]) by Pharaoh ] in 1450 BC, was the first usage of the term or somehow connected. Francis Breyer also believes the Egyptian demonym to be the source of the Semitic term.<ref name="HABESHA">Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. '']'': D-Ha. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005. p. 948.</ref><ref name="Breyer">{{cite journal |last1=Breyer |first1=Francis |title=The Ancient Egyptian Etymology of Ḥabašāt "Abessinia" |journal=Ityop̣is |date=2016 |volume=Extra Issue II |pages=8–18|url=http://www.ityopis.org/Issues-Extra-2_files/ityopis-extra2-breyer.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| {{Related articles|People of Ethiopia|Demographics of Eritrea}} | |||

| There are varying definitions of who identifies as an Abyssinian (more accurately known as an "Habesha"). These definitions vary from community to community, from Western anthropological theories to day-to-day usage, from generation to generation, and between the various diaspora groups and communities that still reside in their ancestral homeland. Differences in usage can be found among different communities and people within the same constituent ethnic group. Below are a few of the major stances:<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|last=Yäafrika|first=Habesha Gaaffaa-Geeska|date=Summer–Fall 2018|editor-last=Habesha Union |title=What do you mean by Habesha? — A look at the Habesha Identity (p.s./t: It's very Vague, Confusing, & Misunderstood)|url=https://www.academia.edu/37510451|department=Department of Modern Culture|journal=International Journal of Ethiopian Studies|volume={{volume needed|date=March 2020}}|pages=1–16|via=}}</ref> | |||

| The first attestation of late Latin ''Abissensis'' is from the fifth century CE. The 6th-century author ] later used the term "Αβασηνοί" (i.e. Abasēnoi) to refer to "an Arabian people living next to the ] together with the ]." The region of the Abasēnoi produce myrrh, incense and cotton and they cultivate a plant which yields a purple dye (probably ''wars'', i.e. '']''). It lay on a route which leads from ] on the coastal plain to the Ḥimyarite capital ].<ref name="HABESHA" /> Abasēnoi was located by Hermann von Wissman as a region in the ''Jabal Ḥubaysh'' ] in ],<ref name="Geoview">{{citation |publisher=Geoview.info |title=Jabal Ḩubaysh |url=http://ye.geoview.info/jabal_hubaysh,74610 |access-date=2018-01-11}}</ref> perhaps related in etymology with the ḥbš ]). Other place names in Yemen contain the ḥbš root, such as the Jabal Ḥabaši, whose residents are still called ''al-Aḥbuš'' (pl. of ''Ḥabaš'').<ref name="Encyc2">Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. ''], D–Ha''. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005. p. 949</ref> The location of the Abasēnoi in Yemen may perhaps be explained by remnant Aksumite populations from the 520s conquest by ]. ] claims to Sahlen (Saba) and Dhu-Raydan (Himyar) during a time when such control was unlikely may indicate an Aksumite presence or coastal foothold.<ref>Munro-Hay. ''Aksum'', p. 72.</ref> Traditional scholarship has assumed that the Habashat were a tribe from modern-day Yemen that migrated to Ethiopia and Eritrea. However, the ] inscriptions only use the term ḥbšt to the refer to the Kingdom of Aksum and its inhabitants, especially during the 3rd century, when the ḥbšt (Aksumites) were often at war with the Sabaeans and Himyraites.<ref name="Encyc2" /> Modern Western European languages, including English, appear to borrow this term from the post-classical form ''Abissini'' in the mid-sixteenth century. (English ''Abyssin'' is attested from 1576, and ''Abissinia'' and ''Abyssinia'' from the 1620s.)<ref>{{cite web |title=Abyssin, n. and adj. |url=https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/291148 |website=Oxford English Dictionary |publisher=Oxford University Press |access-date=25 September 2020}}</ref> | |||

| === Conservative definition === | |||

| {{Related articles|Eritrean Highlands|Ethiopian Highlands}} | |||

| Under a conservative definition of Abyssinian people, Abyssinian people (Habesha) includes the ethnic groups: ], ], ], ], ], and ] which either speak an Ethiosemitic-language and/or traditionally inhabited the Northern Ethiopian-] while still being Cushitic-speakers (like the ] Agawa people who inhabit the ]). | |||

| === Usage === | |||

| ==== Ultra-neo-conservative definition ==== | |||

| Historically, the term "Habesha" represented northern ] Semitic speaking ], while the ] such as ] and ], as well as Semitic-speaking Muslims/], were considered the periphery.<ref>{{cite thesis |type=PhD | last=Makki | first=Fouad | date=2006 | title=Eritrea between empires: Nationalism and the anti-colonial imagination, 1890–1991 | publisher=] |pages=342–345}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Epple |first1=Susanne |title=Creating and Crossing Boundaries in Ethiopia: Dynamics of Social Categorization and Differentiation |year=2014 |publisher=LIT Verlag Münster |page=194 |isbn=9783643905345 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AuRcBAAAQBAJ&q=habesha+christian&pg=PA194}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Historical Dictionary of Eritrea |date= 2010 |publisher=Scarecrow Press |page=279 |isbn=9780810875050 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SYsgpIc3mrsC&q=habesha+self+descriptive+definition&pg=PA279}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Making Citizens in Africa: Ethnicity, Gender, and National Identity in Ethiopia |date= 2013 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |page=54 |isbn=9781107035317 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DGFgnKYnq9YC&q=christian+highlander+habesha&pg=PA54}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Belcher |first1=Wendy |title=Abyssinia's Samuel Johnson Ethiopian Thought in the Making of an English Author |date=2012 |publisher=Oxford University Press |page=37 |isbn=978-0-19-979321-1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1lWhtc19N9YC&dq=This+new+dynasty+was+of+the+Agaw+cultural+group,+not+the+Habesha.&pg=PA37}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Jalata |first1=A |title=Fighting Against the Injustice of the State and Globalization Comparing the African American and Oromo Movements |date= 2002 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |page=99 |isbn=9780312299071 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UMiHDAAAQBAJ&dq=falasha+habasha&pg=PA99}}</ref> | |||

| {{Related articles|Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front|Oromo Liberation Front|Scientific racism}} | |||

| In this definition, only Amharas and Tigrayans are considered Abyssinian people or at least "Abyssinian people proper." This definition is mostly used by certain European Anthropologists, ] and some ] Ethiopian political parties or movements like the ] (EPRDF), the ] (OLF), ] (TPLF), and the ].<ref name=":2" /><ref name="Levine, Donald 2000 p. 18">Levine, Donald (May 2000). ''Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society''. University of Chicago Press. p. 18. {{ISBN|9780226475615}}. Retrieved 28 December 2016.</ref>{{Failed verification|date=March 2020|talk=Synthesis, POV}} | |||

| According to Gerard Prunier, one very restrictive use of the term today by some Tigrayans refers exclusively to speakers of ]; however, Tigrayan oral traditions and linguistic evidence bear witness to ancient and constant relations with Amharas.<ref>{{cite book|title=Understanding Contemporary Ethiopia: Monarchy, Revolution and the Legacy of Meles Zenawi|date=2015|publisher=C. Hurst & Co.|isbn=9781849042611|editor1-last=Prunier|editor1-first=Gérard|location=London|page=19 |editor2-last=Ficquet|editor2-first=Éloi}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Hetzron |first=Robert |title=Ethiopian Semitic: Studies in Classification |publisher=Manchester University Press |year=1972 |isbn=9780719011238 |page=124 |language=English}}</ref> Some ] societies, such as Orthodox Christian communities where ] is spoken, identify as Habesha and have a strong sense of Ethiopian national identity, due in part to their ancient ties with the northern Habesha.<ref>{{cite book|title=Understanding Contemporary Ethiopia: Monarchy, Revolution and the Legacy of Meles Zenawi|date=2015|publisher=C. Hurst & Co.|isbn=9781849042611|editor1-last=Prunier|editor1-first=Gérard|location=London|pages=39, 440|editor2-last=Ficquet|editor2-first=Éloi}}</ref> | |||

| === General usage === | |||

| {{See also|Ethiopian nationalism|Eritrean nationalism|Pan-nationalism}} | |||

| The General Definition for the term "Habesha," has varying usages that are used by various groups and generations, both within their ethnic homelands and in the diaspora.<ref name=":2" /><ref>Oliphant, S. M. (2015). ''The impact of social networks on the immigration experience of ethiopian women'' (Order No. 3705725). Available from Ethnic NewsWatch; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1691345929).</ref> | |||

| Predominately Muslim ethnic groups in the ] such as the ] have historically opposed the name Habesha; Muslim Tigrinya-speakers are usually referred to as ]. Another term for Muslims from the ] was ], this applied to even the empress ] due to her ties to the state of ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Erlikh |first1=Ḥagai |title=The Cross and the River Ethiopia, Egypt, and the Nile |date=2002 |publisher=L. Rienner |page=39 |isbn=978-1-55587-970-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mhCN2qo43jkC&dq=to+distinguish+the+muslims+of+the+horn+from+the+christian+habasha&pg=PA39}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Meri |first1=Josef |title=Medieval Islamic Civilization An Encyclopedia |date= 2005 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |page=12 |isbn=978-1-135-45596-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=c1ZsBgAAQBAJ&dq=the+network+of+islamic+sultanates+known+to+arab+geographers+as+the+country+of+zayla&pg=PA12}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Braukämper|first1=Ulrich|title=Islamic History and Culture in Southern Ethiopia: Collected Essays|date=2002|publisher=LIT Verlag Münster|page=61|isbn=9783825856717|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HGnyk8Pg9NgC&dq=queen+zayla&pg=PA61|accessdate=10 January 2018}}</ref> At the turn of the 20th century, elites of the ] employed the conversion of various ethnic groups to Orthodox Tewahedo Christianity and the imposition of the Amharic language to spread a common Habesha national identity.<ref>{{cite book |last=Jalata |first=Asafa |title=Cultural Capital and Prospects for Democracy in Botswana and Ethiopia |date= 2019 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=9781000008562 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BuyYDwAAQBAJ&q=conquest+of+habasha&pg=PT122}}</ref> | |||

| ===== Constituent Pre-Diaspora Ethnic Groups: ===== | |||

| ], ], ], Agaw-Hamyra, ], ], ], Arbore, ], Bacha, Basketo, Bena, Bench, ], Bodi, Brayle, Burji, Chara, Daasanach, Dawro, Debase/Gawwada, Dime, Dirashe, Dizi, Donga, Fedashe, ] (Ethiopian Jews), Gamo, Gebato, Gedeo, Gedicho, Gidole, ] (Gofa People), ], ], ], Hamar, ], Irob, Kafficho, Kambaata, Karo, Komo, Konso, Konta, Koore, Koyego, Kunama, Kusumie, Kwegu, Majangir, Male, Mao, Mareqo, Mashola, ], Mere people, Messengo, Mossiye, Murle, Mursi, Nao, Nuer, Nyangatom, ], Oyda, Qebena, Qechem, Qewama, She, Shekecho, Sheko, Shinasha, Shita/Upo, ], Silt’e, ] (]), Surma, Tembaro, Tigray, ], ], Werji, Zelmam, Zeyese, Tigrinya, Tigre, Afar, Saho, ], ], Nara, and Yem.<ref>Yäafrika, Habesha Gaaffaa-Geeska (Summer–Fall 2018). Habesha Union (ed.). "What do you mean by Habesha? — A look at the Habesha Identity (p.s./t: It's very Vague, Confusing, & Misunderstood)". Department of Modern Culture. ''International Journal of Ethiopian Studies'': 1–16.</ref> | |||

| Within ] and ] populations, some second generation immigrants have adopted the term "Habesha" in a broader sense as a supra-national ethnic identifier inclusive of all Eritreans and Ethiopians. For those who employ the term, it serves as a useful counter to more exclusionary identities such as "Amhara" or "Tigrayan". However, this usage is not uncontested: On the one hand, those who grew up in Ethiopia or Eritrea may object to the obscuring of national specificity.<ref name=":3">{{Cite journal | last=Goitom | first=Mary | date=2017| title='Unconventional Canadians': Second-generation 'Habesha' youth and belonging in Toronto, Canada. | journal=Global Social Welfare | volume=4 | issue=4 | pages=179–190 | doi=10.1007/s40609-017-0098-0 | publisher=]| s2cid=157892263 }}</ref>{{Rp|186–188}} On the other hand, groups that were subjugated in Ethiopia or Eritrea sometimes find the term offensive.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Habecker |first1=Shelly |title=Not black, but Habasha: Ethiopian and Eritrean immigrants in American society |journal=Ethnic and Racial Studies |date=2012 |volume=35 |issue=7 |pages=1200–1219|doi=10.1080/01419870.2011.598232 |s2cid=144464670 }}</ref> | |||

| ===== Constituent Post-Diaspora Ethnic Groups: ===== | |||

| ] (Oromo Australian), ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and other ] of Ethiopian-Eritrean Origin. | |||

| == Origins == | |||

| ====Ethnic groups that already overlap==== | |||

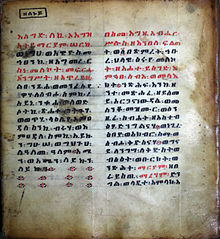

| ] inscriptions found at ], Ethiopia.]] | |||

| Certain ethnic groups already overlap between the "Conservative Definition" and the "Most Common Usage (General Definition)," like the ] inhabiting ] and ] (under the "Conservative Definition"), the ] inhabiting parts of ], ], and ]; the ] inhabiting Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Djibouti; as well as the ] who are indigenous to ], Ethiopia, and ] (under the "Most Common Usage (General Definition)") are also considered "Habesha" by various overlapping positions. | |||

| European scholars postulated that the ancient communities that evolved into the modern Ethiopian state were formed by a migration across the Red Sea of ]-speaking South Arabian tribes, including one called the "''Habashat"'', who intermarried with the local non-Semitic-speaking peoples, in around 1,000 BC. Many held to this view because "epigraphic and monumental evidence point to an indisputable South Arabian influence suggesting migration and colonization from Yemen in the early 1st millennium BC as the main factor of state formation on the highlands. Rock inscriptions in Qohayto (Akkala Guzay, Eritrea) document the presence of individuals or small groups from Arabia on the highlands at this time."<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=D'Andrea |first1=A. Catherine |last2=Manzo |first2=Andrea |last3=Harrower |first3=Michael J. |last4=Hawkins |first4=Alicia L. |date=2008 |title=The Pre-Aksumite and Aksumite Settlement of NE Tigrai, Ethiopia |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/25608503 |journal=Journal of Field Archaeology |volume=33 |issue=2 |pages=151–176 |doi=10.1179/009346908791071268 |jstor=25608503 |s2cid=129636976 |issn=0093-4690}}</ref> It was first suggested by German orientalist ] and revived by early 20th-century Italian scholar ]. According to this theory, Sabaeans brought with them South Arabian letters and language, which gradually evolved into the Ge'ez language and ]. Linguists have revealed, however, that although its script developed from ] (whose oldest inscriptions are found in Yemen), Ge'ez is descended from a different branch of Southern Semitic, ].<ref name="Geez" /> South Arabian inscriptions does not mention any migration to the west coast of the Red Sea, nor of a tribe called "Habashat." All uses of the term date to the 3rd century AD and later, when they referred to the people of the Kingdom of Aksum.<ref>{{cite book |first=Matthew C. |last=Curtis |chapter=Ancient Interaction across the Southern Red Sea: cultural exchange and complex societies in the 1st millennium BC |title=Red Sea Trade and Travel |location=Oxford |publisher=Archaeopress |year=2002 |page=60 |isbn=978-1841716220 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |first=A. K. |last=Irvine |title=On the identity of Habashat in the South Arabian inscriptions |journal=] |volume=10 |year=1965 |issue=2 |pages=178–196 |doi=10.1093/jss/10.2.178 }}</ref> ] has asserted that the Tigrayans and the Amhara comprise "Abyssinians proper" and a "Semitic outpost," while ] has argued that this view "neglects the crucial role of non-Semitic elements in Ethiopian culture."<ref name="dnl">{{cite book|last1=Levine|first1=Donald|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TtmFQejWaaYC&q=%22Abyssinians+proper%2C+the%22&pg=PA19|title=Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society|date=2000|publisher=University of Chicago Press|isbn=9780226475615|page=18|access-date=28 December 2016}}</ref> ] and ]'s theory that ] of the northern ] were ancient foreigners from South Arabia that displaced the original peoples of the Horn has been disputed by Ethiopian scholars specializing in Ethiopian Studies such as Messay Kebede and Daniel E. Alemu who generally disagree with this theory arguing that the migration was one of reciprocal exchange, if it even occurred at all. In the 21st century, scholars have largely discounted the longstanding presumption that Sabaean migrants had played a direct role in Ethiopian civilization.<ref name="pankhurst2003-01-17">{{cite web|last=Pankhurst |first=Richard K. P. |author-link=Richard Pankhurst (historian) |work=Addis Tribune |url=http://www.addistribune.com/Archives/2003/01/17-01-03/Let.htm |title=Let's Look Across the Red Sea I |date=January 17, 2003 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060830103110/http://addistribune.com/Archives/2003/01/17-01-03/Let.htm |archive-date=August 30, 2006 }}</ref><ref>Alemu, Daniel E. (2007). "Re-imagining the Horn". ''African Renaissance''. 4 (1): 56–64 – via Ingenta."This is not to say that events associated with conquest, conflict and resistance did not occur. No doubt, they must have been frequent. But the crucial difference lies in the propensity to present them, not as the process by which an alien majority imposed its rule but as part of an ongoing struggle of native forces competing for supremacy in the region. The elimination of the alien ruler indigenize Ethiopian history in terms of local actors."</ref><ref name=":0">Kebede, Messay (2003). "Eurocentrism and Ethiopian Historiography: Deconstructing Semitization". University of Dayton-Department of Philosophy. ''International Journal of Ethiopian Studies''. Tsehai Publishers. '''1''': 1–19.</ref><ref name=":1">Alemu, Daniel E. (2007). "Re-imagining the Horn". ''African Renaissance''. '''4.1''': 56–64 – via Ingenta.</ref><ref>Stefan Weninger. "Ḥäbäshat", ''Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha''.</ref> | |||

| Scholars have determined that the ancient Semitic language of Ethiopia was not derived from the ]. Recent linguistic studies as to the origin of the Ethiosemitic languages seem to support the DNA findings of immigration from the Arabian Peninsula,<ref>{{Cite book |last=David Reich (Harvard Medical School) |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uLNSDwAAQBAJ |title=Who We are and how We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past |date=2018 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-882125-0 |pages=216–217 |language=en |quote=There is significant archaeological evidence of intense contact and migration between Ethiopia and southern Arabia around 3,000 years BP. During the first millennium BC, southern Arabians from the Saba territory established a polity in the Abyssinian highlands of Ethiopia, and a new conglomerate cultural landscape called the Ethio-Sabean society emerged. This event overlaps with the timing of Eurasian genetic admixture signals in Ethiopian populations and is a good candidate for the source of Eurasian admixture in East Africa.}}</ref> with a recent study using Bayesian computational phylogenetic techniques finding that contemporary Ethiosemitic languages of Africa reflect a single introduction of early Ethiosemitic from southern Arabia approximately 2,800 years ago, and that this single introduction of Ethiosemitic subsequently underwent quick diversification within Ethiopia and Eritrea.<ref name="Semitic Bayesian">{{cite journal |title=Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Semitic languages identifies an Early Bronze Age origin of Semitic in the Near East |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences |volume=276 |issue=1668 |pages=2703–2710 |doi=10.1098/rspb.2009.0408 |pmid=19403539 |pmc=2839953 |year=2009 |last1=Kitchen |first1=Andrew |last2=Ehret |first2=Christopher |last3=Assefa |first3=Shiferaw |last4=Mulligan |first4=Connie J. }} Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Semitic languages identifies an Early Bronze Age origin of Semitic in the ].</ref><ref name="Geez">Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. '']'', "Ge'ez" (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), p. 732.</ref> There is also evidence of ancient Southern Arabian communities in modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea in certain localities, attested by some archaeological artifacts and ancient Sabaean inscriptions in the old ]. Joseph W. Michels noted based on his archeological surveying Aksumite sites that "there is abundant evidence of specific Sabean traits such as inscription style, religious ideology and symbolism, art style and architectural techniques."<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Curtis |first=Matthew C. |date=2008 |title=Review of Changing Settlement Patterns in the Aksum-Yeha Region of Ethiopia: 700 BC–AD 850 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/40282460 |journal=The International Journal of African Historical Studies |volume=41 |issue=1 |pages=123–126 |jstor=40282460 |issn=0361-7882}}</ref> However, ] points to the existence of an older D'MT kingdom, prior to any Sabaean migration c. 4th or 5th century BC, as well as evidence that Sabaean immigrants had resided in Ethiopia for little more than a few decades at the time of the inscriptions.<ref name="Aksum-57">Munro-Hay, ''Aksum'', p. 57.</ref> Both the indigenous languages of Southern Arabia and the Amharic and Tigrinya languages of Ethiopia belong to the large branch of ] which in turn is part of the ]. Even though the ] are classified under the South Semitic languages branch with a ] substratum. | |||

| === Habesha and Ethiopian, etymological connection === | |||

| {{Full article|Ethiopia#Nomenclature}} | |||

| "Following the Hellenic and Biblical traditions, the ], a third century inscription belonging to the ], indicates that Aksum's then ruler governed an area which was flanked to the west by the territory of Ethiopia and Sasu. The Aksumite King ] would eventually conquer Nubia the following century, and the Aksumites thereafter appropriated the designation "Ethiopians" for their own kingdom. In the ] version of the Ezana inscription, Aἰθιόποι is equated with the unvocalized Ḥbštm and Ḥbśt (Ḥabashat), and denotes for the first time the highland inhabitants of Aksum. This new demonym would subsequently be rendered as 'ḥbs('Aḥbāsh) in ] and later into ሐበሻ (‘Ḥabasha’ or ‘Abesha’) which today denotes all Ethiopians and Eritreans as part of the Habesha Community."<ref>Hatke, George (2013). {{ISBN|978-0-8147-6066-6}}.</ref> | |||

| Munro-May and related scholars believe that Sabaean influence was minor, limited to a few localities, and disappearing after a few decades or a century. It may have represented a trading colony (trading post) or military installations in a symbiotic or military alliance between the Sabaeans and D`MT.<ref name="pankhurst2003-01-173">{{cite web |last=Pankhurst |first=Richard K. P. |author-link=Richard Pankhurst (historian) |date=January 17, 2003 |title=Let's Look Across the Red Sea I |url=http://www.addistribune.com/Archives/2003/01/17-01-03/Let.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060830103110/http://addistribune.com/Archives/2003/01/17-01-03/Let.htm |archive-date=August 30, 2006 |work=Addis Tribune}}</ref><ref name="Aksum-57" /> | |||

| === Acceptance of definitions === | |||

| Acceptance of these various definitions of "Habesha" Identity are partially rooted in history, traditional culture, personal taste, and modern life realities the diaspora face. Term "Habesha" as a cultural or pan-ethnic identity has a varied acceptance among various communities, even within the same ethnic groups. One reason is that the term is ambiguous and different definitions can be used by different factions. Another reasons is that the term fell out of use and was replaced with various singular ethnic identities (even those covered under the "Conservative Definition" and even under the “Ultra-neo-Conservative Definition" had abandoned the term "Habesha" as a culture identity) prior to its reemergence among diaspora children and young adults wanting to consolidate societal power for representation in Western society.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

| In the reign of King ], c. early 4th century AD, the term "Ethiopia" is listed as one of the nine regions under his domain, translated in the ] version of his inscription as {{lang|grc|Αἰθιοπία}} ''Aithiopía.'' This is the first known use of this term to describe specifically the region known today as Ethiopia (and not ] or the entire African and Indian region outside of Egypt).<ref name="HABESHA" /> | |||

| === Medieval definition (Zemene Mesafint) === | |||

| (During the "Zemene Mesafint" regional turmoil and power struggle between semi-religiously divided principalities: Orthodox Christian vs. Muslim, North vs. South, Ethiosemitic-speaking vs. Cushitic-speaking){{Related articles|Zemene Mesafint|Ethiopian Semitic languages|Cushitic languages}} | |||

| During the both Middle Ages and ] the in the Horn of Africa, there were various territorial conflicts between various principalities split Orthodox Christian and Muslim majority localities to gain control. The majority-Orthodox Christian Northern Ethiopian Highlands (mostly the Amhara, Tigray, and ]) were referd to as 'Habesha' by the various Islamic Sultanates south of them. The Medieval Definition is partially built on the Conservative Definition with the addition of a religious identity component. (Generally speaking Abyssinian people can be of any religion).<ref name=":3" /> | |||

| There are many theories regarding the beginning of the Abyssinian civilization. One theory, which is more widely accepted today, locates its origins in the Horn region.<ref>Stuart Munro-Hay, ''Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity''. Edinburgh: University Press, 1991, pp. 57ff.</ref> At a later period, this culture was exposed to ] influence, of which the best-known examples are the ] and Ethiopian Jews (or ]) ethnic groups, but Judaic customs, terminology, and beliefs can be found amongst the dominant culture of the Amhara and Tigrinya.<ref>For an overview of this influence see Ullendorff, ''Ethiopia and the Bible'', pp. 73ff.</ref> Some scholars have claimed that the Indian alphabets had been used to create the vowel system of the ] ], this claim has not yet been effectively proven.<ref>{{cite book |last= Henze|first= Paul B. |title= Layers of Time, A History of Ethiopia|year= 2000|publisher= Palgrave|location= New York|isbn=978-0-312-22719-7|page = 37}}</ref> | |||

| === Western anthropological theories === | |||

| {{See also|Race biology}} | |||

| Western anthropological theories of what ethnic groups constitute the Abyssinian people vary with certain definitions being disputed. Most Western Anthropological Theories in respect towards which ethnic groups are included in the Abyssinian people pan-ethnicity are built on a combination of the Ultra-neo-conservative definition, the conservative definition, and also the medieval definition.<ref name="Levine, Donald 2000 p. 18"/> | |||

| == |

== History == | ||

| {{main|History of Ethiopia}} | |||

| {{Missing information|2=|date=February 2020}} | |||

| ] to divide Africa.]] | |||

| Abyssinian civilization has its roots in the pre-Aksumite culture.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Fattovich|first1=Rodolfo|title=Pre-Aksumite Civilization of Ethiopia|date=1975|publisher=Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, Volumes 5–7|page=73|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ldVtAAAAMAAJ|access-date=6 February 2017}}</ref> An early kingdom to arise was that of ] in the 8th century BC. The ], one of the powerful civilizations of the ancient world, was based there from about 150 BC to the mid of 12th century AD. Spreading far beyond the city of Aksum, it molded one of the earliest cultures of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Architectural remains include finely carved ]e, extensive palaces, and ancient places of worship that are still being used. | |||

| Around the time that the Aksumite empire began to decline, the burgeoning religion of ] made its first inroads in the Abyssinian highlands. During the first ], the companions of ] were received in the Aksumite kingdom. The ], established around 896, was one of the oldest local Muslim states. It was centered in the former ] province in central Ethiopia. The polity was succeeded by the ] around 1285. Ifat was governed from its capital at ] in northern ].<ref>{{cite book|first1=Lidwien|last1=Katpeijns|title=The History of Islam in Africa – Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa|date=2000|publisher=Ohio University Press|isbn=978-0821444610|page=228|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=J1Ipt5A9mLMC&pg=PA228|access-date=20 October 2016}}</ref> | |||

| === Migration === | |||

| ] - the peoples of the ] and its successor states of ] and ] have migrated over the years due to political unrest, ethnic tensions, and civil wars like the ], ] ], ], ], ], and other present conflicts and upheavals. The Habesha peoples have used various ethnological names like "Abyssinians", "Erthyreneans", "Habesha", "Eritrean", "Ethiopian", and "" depending on the time period they fled, their national origin, their political position, regional ancestry, or which of the approximately 85 to 89 constituent ethnic groups they come from. | |||

| === Antiquity === | |||

| * ] - Around half a million of the total five million Eritreans fled the country during the thirty-year ] as well as fleeing violence perpetuated by the ] (]-]). They have formed communities all over the western world (i.e. US in Washington D.C., and Los Angeles; and Europe: Sweden, Germany and Italy). There are more than half a million Eritreans in refugee camps (most in Ethiopia and Sudan). | |||

| * ] - A mass movement of Ethiopian migration during the 20th century into the ] (mostly ]), ], ], ], ], ] (esp. the ] and ]), and ] caused by ethnic violence, politically unrest, and violence perpetuated by the ]] (]) has created a global Ethiopian diaspora. | |||

| === Diaspora Culture === | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| There is a difference between the ] theoretical version of the etymological origin of the term "Habesha" and the way it was used historical or by Habeshas themselves. In contrast to popular Western claims, the term is neither Arabic in origin nor does it specifically refer to Ethiosemitic-speaking peoples. The oldest reference to Habesha was made by ] in 1450 BC, in reference to "a foreign people from the incense producing countries" like ].<ref>Simson Najovits, ''Egypt, trunk of the tree, Volume 2'', (Algora Publishing: 2004), p.258.</ref> "Habesha" also means “incense gatherer“ in the ]. The ] are the native non-Arab inhabitants of Yemen, Oman, and Socotra. They are the direct descendants of the ], ], and to an extent are genetically related to the ] and linguistically related to the ] subgroups of Cushitic Peoples in Sub-Saharan Northeast/Horn of Africa. It is also possible that the Land of Punt covered both the ] and ].<ref>Dimitri Meeks – Chapter 4 – "Locating Punt" from the book ''Mysterious Lands''", by David B. O'Connor and Stephen Quirke.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| In Arabic, the elevated plateau on the east of the Nile, from which most of the waters of that river are derived, is called Habesh, and its people Habshi.<ref name="HABESHAT100">{{cite conference|date=January 1851|title=First Annual Report of the Trustees of Donations for Education in Liberia|conference=Annual Meeting|location=Boston|publisher=T.R. Marvin|page=32|quote=In Arabic, the elevated plateau on the east of the Nile, from which most of the waters of that river are derived, is called Habesh, and its people Habshi{{dubious|date=August 2016}}. The Latin writers transformed Habesh into Abassia, which in time became corrupted into Abyssinia, and restricted, in its meaning, to the northern part of the plateau.}} Published in {{Cite journal|year=1851|editor2=William Lathrop Kingsley|editor3=George Park Fisher|editor4=Timothy Dwight|title=Literary Notices|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4ugXAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA462#v=onepage&q&f=false|journal=New Englander and Yale Review|volume=IX|page=462|accessdate={{Date|2015-08-14}}|editor1=Edward Royall Tyler}}</ref> The modern term derives from the vocalized {{lang-gez|ሐበሣ}} ''Ḥabaśā'', first written with a script that did not mark vowels as {{lang|gez|ሐበሠ }} ''ḤBŚ'' or in "pseudo-Sabaic as ''ḤBŠTM''".<ref name="HABESHA">Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. '']'': D-Ha. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005. p. 948.</ref> The earliest known use of the term dates to the second or third century ] recounting the defeat of the ] ("king") ] of Aksum and ḤBŠT.<ref>{{cite book|title=Aksum: A Civilization of Late Antiquity|last=Munro-Hay|first=Stuart|publisher=]|year=1991|isbn=978-0748601066|page=39}}</ref> The term "Habashat" appears to refer to a group of peoples, rather than a specific ethnicity. A Sabaean inscription describes an alliance between Shamir Yuhahmid of the ] and King ] of ] in the first quarter of the third century. They had lived alongside the Sabaeans, who lived across the ] from them for many centuries: | |||

| {{quote|] of dhū Raydān and Himyar had called in the help of the clans of Habashat for war against the kings of Saba; but Ilmuqah granted... the submission of Shamir of dhū Raydān and the clans of Habashat."<ref>Munro-Hay, ''Aksum'', p. 66.</ref>}} | |||

| The term "Habesha" was formerly thought by some scholars<ref name="HABESHA" /> to be of Arabic descent because the English name ] comes from the Arabic form. (Arabs used the word ''Ḥabaš'', also the name of an Ottoman province, ], comprising parts of modern-day Eritrea).<ref>Munro-Hay, ''Aksum'', p. 19.</ref> South Arabian expert Eduard Glaser claimed that the hieroglyphic ''ḫbstjw'', used in reference to "a foreign people from the incense-producing regions" (i.e. ], located in Eritrea, Northern Somalia, and northeast Ethiopia) used by Queen ] c. 1460 BC, was the first usage of the term or somehow connected. | |||

| Based on the inscriptions the Aksumites left behind, they did not regard themselves or their territory as Habesha. For them, Habeshas likely meant people who collected ] in ]. ], the Greek-speaking Egyptian traveler who visited the ] in 525, also made no reference to Habesha.<ref name="HABESHAT6">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7GdyAAAAMAAJ|title=Ethiopia: A Cultural History|last=Pankhurst|first=Estelle Sylvia|publisher=Lalibela House|year=1955|ref=harv}}, p. 22.</ref><ref name="HABESHAT2"> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150415051356/http://www.eriswiss.com/the-true-origin-of-habesha/|date=2015-04-15}}, eriswiss.com Retrieved 2015-04-10</ref> According to Dr. Eduard Glaser, an Austrian epigraphist and historian, "Habesha" was originally used to refer to a kingdom in southeastern Yemen located east of the ] kingdom in what is now ]. He believed the etymology of Habesha must have derived from the ], which means “gatherers” (as in gatherers of incense).<ref name="HABESHAT2" /><ref name="HABESHAT1">: J. Murray, 1895. p. 415.</ref> It was not until long after Aksumite kingdom had ended that Gulf Arab travelers and geographers began to describe the Horn region as ]. The first among these travelers were Al-Mas`udi and Al-Harrani.<ref name="HABESHAT8"> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304125055/http://dskmariam.org/artsandlitreature/litreature/pdf/aksum.pdf|date=2016-03-04}}: Stuart Munro-Hay, 1991. p. 90</ref> | |||

| ], a tenth-century Gulf Arab traveler to the region, described Habesha country in his geographical work '']''. He wrote that "the chief town of the Habasha is called Kuʿbar, which is a large town and the residence of the Najashi (nagassi; king), whose empire extends to the coasts opposite the Yemen, and possesses such towns as Zayla, Dahlak and Nasi."<ref name="HABESHAT8" /> Al-Harrani, another Gulf Arab traveler, also asserted in 1295 CE that "one of the greatest and best-known towns is Kaʿbar, which is the royal town of the najashi ... Zaylaʿ, a town on the coast of the Red Sea, is a very populous commercial center... . Opposite al-Yaman there is also a big town, which is the seaport from which the Habasha crossed the sea to al-Yaman, and nearby is the island of ʿAql."<ref name="HABESHAT8" /> | |||

| By the end of the 8th century, most of the prominent Yemeni kingdoms ended and areas they once controlled were under foreign occupation. Yemen's turbulence, coupled with its ecological volatility likely shifted the international trade of incense from South Arabia to the Horn region. With Habasha originally used to describe people who gathered incense, this term was also given to the region by early Gulf Arab merchants and travelers as a geographic expression that some of the inhabitants of the Horn adopted over time.<ref name="HABESHAT2" /> | |||

| When Portuguese missionaries arrived in the interior of what is present-day Ethiopia in the early 16th century CE, they took the altered word Abesha (without the letter “H” beginning) which is used by Ethiopian Amharic speakers of the time and subsequently Latinized it to ''Abassia'', ''Abassinos'', ;''Abessina'' and finally into ''Abyssinia''. This Abyssinia term was widely used as a geographic expression for centuries, even though it was a term not used by the local inhabitants.<ref name="HABESHAT2" /><ref name="HABESHAT10">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=y9A0uAW929EC&pg=PA52|title=The Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Difussion of Useful Knowledge|publisher=Charles Knight|year=1833|ref=harv}}, p. 52.</ref> | |||

| == History== | |||

| ] to divide Africa.]] | |||

| Abyssinian civilization has its roots in the pre-Aksumite culture.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Fattovich|first1=Rodolfo|title=Pre-Aksumite Civilization of Ethiopia|date=1975|publisher=Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, Volumes 5-7|page=73|url=https://www.google.com/books?id=ldVtAAAAMAAJ|accessdate=6 February 2017}}</ref> An early kingdom to arise was that of ] in the 8th century BC. The ], one of the powerful civilizations of the ancient world, was based there from about 150 BC to the mid of 12th century AD. Spreading far beyond the city of Aksum, it molded the one of the earliest cultures of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Architectural remains include finely carved ]e, extensive palaces, and ancient places of worship that are still being used. | |||

| {{History of Ethiopia}} | |||

| Around the time that the Aksumite empire began to decline, the burgeoning religion of ] made its first inroads in the Abyssinian highlands. During the first ], the companions of prophet ] were received in the Aksumite kingdom. The ], established around 896, was one of the oldest local Muslim states. It was centered in the former ] province in central Ethiopia. The polity was succeeded by the ] around 1285. Ifat was governed from its capital at ] in northern ] and was the easternmost district of the former Shewa Sultanate.<ref>{{cite book|first1=Lidwien|last1=Katpeijns|title=The History of Islam in Africa - Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa|date=2000|publisher=Ohio University Press|isbn=978-0821444610|page=228|url=https://www.google.com/books?id=J1Ipt5A9mLMC&pg=PA228#v=onepage&q&f=false|accessdate=20 October 2016}}</ref> | |||

| {{History of Eritrea}} | |||

| ===Antiquity=== | |||

| ].]] | ].]] | ||

| Throughout history, populations in the Horn of Africa had been interacting through migration, trade, warfare and intermarriage. Most people in the region spoke ], with the family's ] and ] branches predominant.<ref>Munro-Hay, ''Aksum'', p. 62</ref> As early as the 3rd millennium BCE, the pre-Aksumites had begun trading along the Red Sea. They mainly traded with Egypt. Earlier trade expeditions were taken by foot along the Nile Valley. The ancient Egyptians' main objective in the ] trade was to acquire ]. This was a commodity that the Horn region, which the ancient Egyptians referred to as the ], had in abundance. Much of the incense is produced in Somalia to this day. | Throughout history, populations in the Horn of Africa had been interacting through migration, trade, warfare and intermarriage. Most people in the region spoke ], with the family's ] and ] branches predominant.<ref>Munro-Hay, ''Aksum'', p. 62</ref> As early as the 3rd millennium BCE, the pre-Aksumites had begun trading along the Red Sea. They mainly traded with Egypt. Earlier trade expeditions were taken by foot along the Nile Valley. The ancient Egyptians' main objective in the ] trade was to acquire ]. This was a commodity that the Horn region, which the ancient Egyptians referred to as the ], had in abundance. Much of the incense is produced in Somalia to this day. | ||

| Line 182: | Line 50: | ||

| The Kingdom of Aksum may have been founded as early as 300 BCE. Very little is known of the time period between the mid-1st millennium BCE to the beginning of Aksum's rise around the 1st century CE. It is thought to be a successor kingdom of ], a kingdom in the early 1st millennium BC most likely centered at nearby ].<ref>Munro-Hay, ''Aksum'', p. 4</ref> | The Kingdom of Aksum may have been founded as early as 300 BCE. Very little is known of the time period between the mid-1st millennium BCE to the beginning of Aksum's rise around the 1st century CE. It is thought to be a successor kingdom of ], a kingdom in the early 1st millennium BC most likely centered at nearby ].<ref>Munro-Hay, ''Aksum'', p. 4</ref> | ||

| The Kingdom of Aksum was situated in northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, with its capital city in Northern Ethiopia. ] remained its capital until the 7th century. The kingdom was favorably located near the Blue Nile basin and the Afar depression. The former is rich in gold and the latter in salt: both materials having a highly important use to the Aksumites. Aksum was accessible to the port of ], ] on the coast of the Red Sea. The kingdom traded with Egypt, India, Arabia and the ]. Aksum's "fertile" and "well-watered" location produced enough food for its population. Wild animals included elephants and rhinoceros.<ref>Pankhurst 1998, pp. |

The Kingdom of Aksum was situated in northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, with its capital city in Northern Ethiopia. ] remained its capital until the 7th century. The kingdom was favorably located near the ] basin and the Afar depression. The former is rich in gold and the latter in salt: both materials having a highly important use to the Aksumites. Aksum was accessible to the port of ], ] on the coast of the Red Sea. The kingdom traded with Egypt, India, Arabia and the ]. Aksum's "fertile" and "well-watered" location produced enough food for its population. Wild animals included elephants and rhinoceros.<ref>Pankhurst 1998, pp. 22–23</ref> | ||

| From its capital, Aksum commanded the trade of ]. It also dominated the trade route in the Red Sea leading to the Gulf of Aden. Its success depended on resourceful techniques, production of coins, steady migrations of Greco-Roman merchants, and ships landing at Adulis. In exchange for Aksum's goods, traders bid many kinds of cloth, jewelry, metals and steel for weapons. | From its capital, Aksum commanded the trade of ]. It also dominated the trade route in the Red Sea leading to the Gulf of Aden. Its success depended on resourceful techniques, production of coins, steady migrations of Greco-Roman merchants, and ships landing at Adulis. In exchange for Aksum's goods, traders bid many kinds of cloth, jewelry, metals and steel for weapons. | ||

| Line 188: | Line 56: | ||

| At its peak, Aksum controlled territories as far as southern Egypt, east to the ], south to the ], and west to the Nubian Kingdom of ]. The South Arabian kingdom of the Himyarites and also a portion of western Saudi Arabia was also under the power of Aksum. Their descendants include the present-day ethnic groups known as the Amhara, Tigrayans and Gurage peoples.{{Citation needed|date=September 2018}} | At its peak, Aksum controlled territories as far as southern Egypt, east to the ], south to the ], and west to the Nubian Kingdom of ]. The South Arabian kingdom of the Himyarites and also a portion of western Saudi Arabia was also under the power of Aksum. Their descendants include the present-day ethnic groups known as the Amhara, Tigrayans and Gurage peoples.{{Citation needed|date=September 2018}} | ||

| ===Medieval and |

=== Medieval and early modern period === | ||

| After the fall of Aksum due to declining sea trade from fierce competition by Muslims and changing climate, the power base of the kingdom migrated south and shifted its capital to Kubar (near Agew). They moved southwards because, even though the Axumite Kingdom welcomed and protected the companions of |

After the fall of Aksum due to declining sea trade from fierce competition by Muslims and changing climate, the power base of the kingdom migrated south and shifted its capital to Kubar (near Agew). They moved southwards because, even though the Axumite Kingdom welcomed and protected the companions of Muhammad to Ethiopia, who came as refugees to escape the persecution of the ruling families of Mecca and earned the friendship and respect of Muhammad. Their friendship deteriorated when South-Arabians invaded the Dahlak islands through the port of Adulis and destroyed it, which was the economic backbone for the prosperous Aksumite Kingdom. Fearing of what recently occurred, Axum shifted its capital near Agew.{{clarify|date=December 2014}} In the middle of the sixteenth century ] armies led by ] leader ] invaded Habesha lands in what is known as the ''"Conquest of Habasha"''.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Jayussi |first1=Salma |title=The City in the Islamic World |date=2008 |publisher=Brill |page=625 |isbn=9789047442653 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tO55DwAAQBAJ&q=but+a+coalition+of+Muslim+peoples+grouped+and+based+in+the+harar+region+under+the+authority+of+imam+ahmad&pg=PA625}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Cook |first1=David |title=Martyrdom in Islam |date=2007 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |page=91 |isbn=9780521615518 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dX0KUGLxg8AC&q=conquest+of+habasha&pg=PA91}}</ref> Following Adal invasions, the southern part of the Empire was lost to Oromo and Muslim state of ] thus scattered Habesha like the Gurage people were cut off from the rest of Abyssinia.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Aregay |first1=Merid |title=Southern Ethiopia and the Christian kingdom 1508–1708 with special reference to the Galla migrations and their consequences |publisher=University of London |pages=438–439 |url=https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.308149 |access-date=2024-01-04 |archive-date=2021-04-21 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210421231927/https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.308149 |url-status=dead }}</ref> In the late sixteenth century the nomadic Oromo people penetrated the Habesha plains occupying large territories during the ].<ref>{{cite journal |title=Ethiopia, a Country Study |journal=U.S. Government Printing Office |volume=28 |pages=13–14 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=t_JyAAAAMAAJ&q=oromo+migrations+habasha&pg=PA13|last1=Nelson |first1=Harold D. |last2=Kaplan |first2=Irving |year=1981 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Reid |first1=Richard |title=Frontiers of Violence in North-East Africa: Genealogies of Conflict Since C. 1800 |date= 2011 |publisher=Oxford University Press |page=30 |isbn=9780199211883 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=m5ESDAAAQBAJ&q=oromo+migrations+habasha&pg=PA30}}</ref> Abyssinian warlords often competed with each other for dominance of the realm. The Amharas seemed to gain the upper hand with the accession of Yekuno Amlak of Ancient Bete Amhara in 1270, after defeating the Agaw lords of Lasta (in those days a non-Semitic-speaking region of Abyssinia) | ||

| ] ] with his son and heir, Ras ].]] | ] ] with his son and heir, Ras ].]] | ||

| The Gondarian dynasty, which since the 16th century had become the centre of Royal pomp and ceremony of Abyssinia, finally lost its influence as a result of the emergence of powerful regional lords, following the murder of ], also known as Iyasu the Great. The decline in the prestige of the dynasty led to the semi-anarchic era of ] ("Era of the Princes"), in which rival warlords fought for power and the ] |

The Gondarian dynasty, which since the 16th century had become the centre of Royal pomp and ceremony of Abyssinia, finally lost its influence as a result of the emergence of powerful regional lords, following the murder of ], also known as Iyasu the Great. The decline in the prestige of the dynasty led to the semi-anarchic era of ] ("Era of the Princes"), in which rival warlords fought for power and the ] '']'' ({{langx|am|እንደራሴ}}, "regents") had effective control. The ] were considered to be figureheads. Until a young man named Kassa Haile Giorgis also known as ] brought end to ''Zemene Mesafint'' by defeating all his rivals and took the throne in 1855. The Tigrayans made only a brief return to the throne in the person of ] in 1872, whose death in 1889 resulted in the power base shifting back to the dominant Amharic-speaking elite. His successor ] an Emperor of Amhara origin seized power. Upon Menelik's occupation of the ] and other neighboring states, a considerable number of natives were displaced and Abyssinians settled in their place.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Matshanda |first1=Namhla |title=Centres in the Periphery: Negotiating Territoriality and Identification in Harar and Jijiga from 1942 |date=2014 |publisher=The University of Edinburgh |page=198 |s2cid=157882043 |url=https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e51e/aa84c13ba093ddf2bc242117aa9d8179dd71.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200131094220/https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e51e/aa84c13ba093ddf2bc242117aa9d8179dd71.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-date=31 January 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Gebissa |first1=Ezekiel |title=Leaf of Allah Khat & Agricultural Transformation in Harerge, Ethiopia 1875–1991 |date=2004 |publisher=James Currey |page=44 |isbn=978-0-85255-480-7 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ga91oPVFb5MC&dq=amhara+settlers+harar&pg=PA44}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Borelli |first1=Jules |title=Éthiopie méridionale journal de mon voyage aux pays Amhara, Oromo et Sidama, septembre 1885 à novembre 1888 |year=1890 |publisher=Quantin, Librairies-imprimeries réunies |pages=238–239 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3AkaAQAAMAAJ&dq=harrar+le+roi+avait+etabli+son+camp+pres+de+la+ville&pg=PA238}}</ref> In ], mainly inhabited by the ], their land was appropriated by the Abyssinian colonizers coupled with hefty taxation which led to a revolt in the 1960s.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Prunier |first1=Gérard |title=Understanding Contemporary Ethiopia Monarchy, Revolution and the Legacy of Meles Zenawi |date= 2015 |publisher=Hurst |isbn=978-1-84904-618-3 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wnxeCwAAQBAJ&dq=amhara+settlers+harar&pg=PT45}}</ref> | ||

| ]' ] in ], ].]] | ]' ] in ], ].]] | ||

| Some scholars consider the Amhara to have been Ethiopia's ruling elite for centuries, represented by the Solomonic line of Emperors ending in ]. Marcos Lemma and other scholars dispute the accuracy of such a statement, arguing that other ethnic groups have always been active in the country's politics. This confusion may largely stem from the mislabeling of all ] as "Amhara", and the fact that many people from other ethnic groups have adopted Amharic ]. Another is the claim that most Ethiopians can trace their ancestry to multiple ethnic groups, including the last self-proclaimed emperor ] and his Empress Itege ] of ].<ref> |

Some scholars consider the Amhara to have been Ethiopia's ruling elite for centuries, represented by the Solomonic line of Emperors ending in ]. Marcos Lemma and other scholars dispute the accuracy of such a statement, arguing that other ethnic groups have always been active in the country's politics. This confusion may largely stem from the mislabeling of all ] as "Amhara", and the fact that many people from other ethnic groups have adopted Amharic ]. Another is the claim that most Ethiopians can trace their ancestry to multiple ethnic groups, including the last self-proclaimed emperor ] and his Empress Itege ] of ].<ref>, Official Ethiopian Monarchy Website.</ref> | ||

| == |

== Culture == | ||

| ===Indigenous theory=== | |||

| ] of ]]] | |||

| The Imperial family of Ethiopia (which is currently in exile) claims its origin directly from descent from ] and the ] ({{lang-gez|ንግሥተ ሣብአ}} ''nigiśta Śabʿa''), who is named ''Makeda'' ({{lang-gez|ማክዳ}}) in the Ethiopian account. The Ethiopian narrative '']'' ("Glory of Kings"), written in 1225 AD<ref>{{cite book |first=David Allen |last=Hubbard |title=The Literary Sources of the "Kebra Nagast" |publisher=St Andrews |year=1956 |page=358 }}</ref> contains an account of Makeda and her descendants. Solomon is said in this account to have seduced the Queen, and sired a son by her, who would eventually become ], the first Emperor of Ethiopia. The tradition that the biblical Queen of Sheba was an ingenuous ruler of Ethiopia who visited King Solomon in Jerusalem is repeated in a 1st-century account by the Roman Jewish historian ]. He identified Solomon’s visitor as a queen of Egypt and Ethiopia. There is no primary evidence, archaeological or textual, for the queen in Ethiopia. The impressive ruins at Aksum are a thousand years too late for a queen contemporary with Solomon, based on traditional dates for him of the 10th century BC.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121029222918/http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/cultures/sheba_01.shtml |date=2012-10-29 }}, BBC History</ref>{{dubious|date=August 2016}} | |||

| In the past, European scholars including ] and ] postulated that the ancient communities that evolved into the modern Ethiopian state were formed by a migration across the Red Sea of Semitic-speaking South Arabians around 1000 BC, who intermarried with local non-Semitic-speaking peoples. Both the indigenous languages of Southern Arabia and the Amharic and Tigrinya languages of Ethiopia belong to the large branch of ] which in turn is part of the ]. Even though the ] are classified under the South Semitic languages branch with a ] substratum, ] and ]'s theory that ] of the northern ] were ancient foreigners from Southwestern Arabia has been disputed by most modern indigenous Horn African scholars like ] and ].{{citation needed|date=April 2019}} {{dubious|date=April 2019}} | |||

| Scholars have determined that the ancient Semitic language of Ethiopia was not derived from an ] language such as ]. There is evidence of a Semitic-speaking presence in Ethiopia and Eritrea as early as 2000 BC.<ref name="Geez">Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. '']'', "Ge'ez" (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), p. 732.</ref> There is also evidence of ancient Southern Arabian communities in modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea in certain localities, attested by some archaeological artifacts and ancient Sabaean inscriptions in the old ]. However, Stuart Munro-Hay points to the existence of an older D'MT kingdom, prior to any Sabaean migration c. 4th or 5th century BC, as well as evidence that Sabaean immigrants had resided in Ethiopia for little more than a few decades at the time of the inscriptions.<ref name="Aksum-57">Munro-Hay, ''Aksum'', p. 57.</ref> Archeological evidence has revealed a region called ''Saba'' in Northern Ethiopia and Eritrea; it is now referred to as "Ethiopian Saba" to avoid confusion. | |||

| Essentially no archaeological evidence supports the story of the Queen of Sheba. "In the 21st century, scholars have largely discounted the longstanding presumption that Sabaean migrants had played a direct role in Ethiopian civilization."<ref name="pankhurst2003-01-17">{{cite web|last=Pankhurst |first=Richard K. P. |authorlink=Richard Pankhurst |work=Addis Tribune |url=http://www.addistribune.com/Archives/2003/01/17-01-03/Let.htm |title=Let's Look Across the Red Sea I |date=January 17, 2003 |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20060830103110/http://addistribune.com/Archives/2003/01/17-01-03/Let.htm |archivedate=August 30, 2006 }}</ref> Munro-May and related scholars believe that Sabaean influence was minor, limited to a few localities, and disappearing after a few decades or a century. It may have represented a trading colony (tarding post) or military installations in a symbiotic or military alliance between the Sabaens and D`MT.<ref name="Aksum-57" /> | |||

| In the reign of King ], c. early 4th century AD, the term "Ethiopia" is listed as one of the nine regions under his domain, translated in the ] version of his inscription as {{lang|grc|Αἰθιοπία}} ''Aithiopía.'' This is the first known use of this term to describe specifically the region known today as Ethiopia (and not ] or the entire African and Indian region outside of Egypt).<ref name="HABESHA" /> The 6th-century author ] later used the term "Αβασηγοί" (i.e. Abasēnoi) to refer to: | |||

| <blockquote>an Arabian people living next to the ] together with the ]. The region of the Abasēnoi produce myrrh, incense and cotton and they cultivate a plant which yields a purple dye (probably ''wars'', i.e. '']''). It lies on a route which leads from ] on the coastal plain to the Ḥimyarite capital ].<ref name="HABESHA" /></blockquote> | |||

| Abasēnoi was located by Hermann von Wissman as a region in the ''Jabal Ḥubaysh'' ({{lang-ar|جَبَل حُبَيْش}}) ] in ],<ref name="Geoview">{{citation |publisher=Geoview.info |title=Jabal Ḩubaysh |url=http://ye.geoview.info/jabal_hubaysh,74610 |access-date=2018-01-11}}</ref> perhaps related in etymology with the ḥbš ]). Other place names in Yemen contain the ḥbš root, such as the Jabal Ḥabaši, whose residents are still called ''al-Aḥbuš'' (pl. of ''Ḥabaš'').<ref name="Encyc2">Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. ''];: D-Ha. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005. pp. 949.''</ref> The location of the Abasēnoi in Yemen may perhaps be explained by remnant Aksumite populations from the 520s conquest by ]. ] claims to Sahlen (Saba) and Dhu-Raydan (Himyar) during a time when such control was unlikely may indicate an Aksumite presence or coastal foothold.<ref>Munro-Hay. ''Aksum'', p. 72.</ref> Traditional scholarship has assumed that the Habashat were a tribe from modern-day Yemen that migrated to Ethiopia and Eritrea. However, the ] inscriptions only use the term ḥbšt to the refer to the Kingdom of Aksum and its inhabitants, especially during the 3rd century, when the ḥbšt (Aksumites) were often at war with the Sabaeans and Himyraites.<ref name="Encyc2" /> | |||

| ===South Arabian/Sabaean origin theory=== | |||

| ] inscriptions found at ], Ethiopia.]]{{See also|Race biology}}{{redirect|Jabal Hubaysh, Yemen|for the Saudi mountain|Jabal Hubaysh, Saudi Arabia}}Before the 20th century, the Sabean theory was the most common one explaining the origins of the Habesha. It was first suggested by German orientalist ] and revived by early 20th-century Italian scholar ]. They said that at an early epoch, South Arabian tribes, including one called the "''Habashat,"'' emigrated across the Red Sea from Yemen to Eritrea. According to this theory, Sabaeans brought with them South Arabian letters and language, which gradually evolved into the Ge'ez language and ]. Linguists have revealed, however, that although its script developed from ] (whose oldest inscriptions are found in Yemen, Ethiopia and Eritrea) used to write the Old South Arabian languages, Ge'ez is descended from a different branch of Semitic, ].<ref name="Geez" /> | |||

| The large corpus of South Arabian inscriptions does not mention any migration to the west coast of the Red Sea, nor of a tribe called "Habashat." All uses of the term date to the 3rd century AD and later, when they referred to the people of the Kingdom of Aksum.<ref>{{cite book |first=Matthew C. |last=Curtis |chapter=Ancient Interaction across the Southern Red Sea: cultural exchange and complex societies in the 1st millennium BC |title=Red Sea Trade and Travel |location=Oxford |publisher=Archaeopress |year=2002 |page=60 |isbn=978-1841716220 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |first=A. K. |last=Irvine |title=On the identity of Habashat in the South Arabian inscriptions |journal=] |volume=10 |year=1965 |issue=2 |pages=178–196 |doi=10.1093/jss/10.2.178 }}</ref> In the 21st century, the Sabean theory has largely been abandoned.<ref>Stefan Weninger. "Ḥäbäshat", ''Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha''.</ref> While most Westerners today and some Horn Africans influenced by German anthropologists, have agreed with the South Arabian origin theory, most indigenous Abyssinian historians even prior to the 21st Century have always refuted these claims. ] and ]'s theory that ] of the northern ] were ancient foreigners from Southwestern Arabia that displaced the original peoples of the Horn, has been disputed by most modern indigenous Horn African scholars like ], ], and others. Genetically, culturally, and geographically speaking Habeshas (Abyssinian people) are traditionally ].<ref name=":0">Kebede, Messay (2003). "Eurocentrism and Ethiopian Historiography: Deconstructing Semitization". University of Dayton-Department of Philosophy. ''International Journal of Ethiopian Studies''. Tsehai Publishers. '''1''': 1–19 – via JSTOR.</ref><ref name=":1">Alemu, Daniel E. (2007). "Re-imagining the Horn". ''African Renaissance''. '''4.1''': 56–64 – via Ingenta.</ref> | |||

| Ethiopia and Sudan are among the main areas linguists suggest were the ]. Recent linguistic studies as to the origin of the Ethiosemitic languages seem to support the DNA findings of immigration from the Arabian Peninsula, with a recent study using Bayesian computational phylogenetic techniques finding that "contemporary Ethiosemitic languages of Africa reflect a single introduction of early Ethiosemitic from southern Arabia approximately 2,800 years ago", and that this single introduction of Ethiosemitic subsequently underwent quick diversification within Ethiopia and Eritrea.<ref name="Semitic Bayesian">{{cite journal |title=Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Semitic languages identifies an Early Bronze Age origin of Semitic in the Near East |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences |volume=276 |issue=1668 |pages=2703–2710 |doi=10.1098/rspb.2009.0408 |pmid=19403539 |pmc=2839953 |year=2009 |last1=Kitchen |first1=Andrew |last2=Ehret |first2=Christopher |last3=Assefa |first3=Shiferaw |last4=Mulligan |first4=Connie J. }} Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Semitic languages identifies an Early Bronze Age origin of Semitic in the ].</ref> | |||

| There are many theories regarding the beginning of the Abyssinian civilization. One theory, which is more widely accepted today, locates its origins in the Horn region, while Westerners acknowledging the influence of the Sabeans on the opposite side of the Red Sea.<ref>Stuart Munro-Hay, ''Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity''. Edinburgh: University Press, 1991, pp. 57f.</ref> At a later period, this culture was exposed to ] influence, of which the best-known examples are the ] and Ethiopian Jews (or ]) ethnic groups, but Judaic customs, terminology, and beliefs can be found amongst the dominant culture of the Amhara and Tigrinya.<ref>For an overview of this influence see Ullendorff, ''Ethiopia and the Bible'', pp. 73ff.</ref> Some scholars have claimed that the Indian alphabets had been used to create the vowel system of the ] ], this claim has not yet been effectively proven.<ref>{{cite book |last= Henze|first= Paul B. |title= Layers of Time, A History of Ethiopia|year= 2000|publisher= Palgrave|location= New York|isbn=978-0-312-22719-7|page = 37}}</ref> | |||

| ==Culture== | |||