| Revision as of 20:47, 30 July 2020 edit68.196.51.230 (talk) →Working principleTag: Manual revert← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:47, 1 June 2024 edit undo384 (talk | contribs)47 edits typoTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| (32 intermediate revisions by 25 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| {{short description|Optical microscopy technique}} | {{short description|Optical microscopy technique}} | ||

| __NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

| {{Infobox laboratory equipment |

{{Infobox laboratory equipment | ||

| |name = Phase-contrast microscope | |name = Phase-contrast microscope | ||

| |image = Phase contrast microscope.jpg | |image = Phase contrast microscope.jpg | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Phase-contrast microscopy''' is an ] technique that converts ] in light passing through a transparent specimen to brightness changes in the image. Phase shifts themselves are invisible, but become visible when shown as brightness variations. | '''Phase-contrast microscopy''' (PCM) is an ] technique that converts ] in light passing through a transparent specimen to brightness changes in the image. Phase shifts themselves are invisible, but become visible when shown as brightness variations. | ||

| When light waves travel through a medium other than ], interaction with the medium causes the wave ] and ] to change in a manner dependent on properties of the medium. Changes in amplitude (brightness) arise from the scattering and absorption of light, which is often wavelength-dependent and may give rise to colors. Photographic equipment and the human eye are only sensitive to amplitude variations. Without special arrangements, phase changes are therefore invisible. Yet, phase changes often |

When light waves travel through a medium other than a ], interaction with the medium causes the wave ] and ] to change in a manner dependent on properties of the medium. Changes in amplitude (brightness) arise from the scattering and absorption of light, which is often wavelength-dependent and may give rise to colors. Photographic equipment and the human eye are only sensitive to amplitude variations. Without special arrangements, phase changes are therefore invisible. Yet, phase changes often convey important information. | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Phase-contrast microscopy is particularly important in biology. | Phase-contrast microscopy is particularly important in biology. | ||

| It reveals many ] structures that are |

It reveals many ] structures that are invisible with a ], as exemplified in the figure. | ||

| These structures were made visible to earlier microscopists by ], but this required additional preparation and |

These structures were made visible to earlier microscopists by ], but this required additional preparation and death of the cells. | ||

| The phase-contrast microscope made it possible for biologists to study living cells and how they proliferate through ]. It is one of the few methods available to quantify cellular structure and components |

The phase-contrast microscope made it possible for biologists to study living cells and how they proliferate through ]. It is one of the few methods available to quantify cellular structure and components without using ].<ref>{{cite web | title=The phase contrast microscope | publisher=Nobel Media AB | url=https://www.nobelprize.org/educational/physics/microscopes/phase}}</ref> | ||

| After its invention in the early 1930s,<ref>{{Cite journal | After its invention in the early 1930s,<ref>{{Cite journal | ||

| | last1 = Zernike | first1 = F. | | last1 = Zernike | first1 = F. | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

| | year = 1955 | | year = 1955 | ||

| | pmid = 13237991 | | pmid = 13237991 | ||

| | pmc = | |||

| |bibcode = 1955Sci...121..345Z }}</ref> phase-contrast microscopy proved to be such an advancement in microscopy that its inventor ] was awarded the ] in 1953.<ref>{{cite web | |bibcode = 1955Sci...121..345Z }}</ref> phase-contrast microscopy proved to be such an advancement in microscopy that its inventor ] was awarded the ] in 1953.<ref>{{cite web | ||

| | title=The Nobel Prize in Physics 1953 | | title=The Nobel Prize in Physics 1953 | ||

| | url=https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1953 | | url=https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1953 | ||

| | publisher=Nobel Media AB}}</ref> | | publisher=Nobel Media AB}}</ref> The woman who manufactured this microscope, ], often remains uncredited. | ||

| == Working principle == | == Working principle == | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The basic principle to |

The basic principle to make phase changes visible in phase-contrast microscopy is to separate the illuminating (background) light from the specimen-scattered light (which makes up the foreground details) and to manipulate these differently. | ||

| The ring-shaped illuminating light (green) that passes the ] annulus is focused on the specimen by the condenser. Some of the illuminating light is ] by the specimen (yellow). The remaining light is unaffected by the specimen and forms the background light (red). When observing an unstained biological specimen, the scattered light is weak and typically ] by −90° (due to both the typical thickness of specimens and the refractive index difference between biological tissue and the surrounding medium) relative to the background light. This leads to the foreground (blue vector) and background (red vector) having nearly the same intensity, resulting in low ]. | The ring-shaped illuminating light (green) that passes the ] annulus is focused on the specimen by the condenser. Some of the illuminating light is ] by the specimen (yellow). The remaining light is unaffected by the specimen and forms the background light (red). When observing an unstained biological specimen, the scattered light is weak and typically ] by −90° (due to both the typical thickness of specimens and the refractive index difference between biological tissue and the surrounding medium) relative to the background light. This leads to the foreground (blue vector) and background (red vector) having nearly the same intensity, resulting in low ]. | ||

| In a phase-contrast microscope, image contrast is increased in two ways: by generating constructive interference between scattered and background light rays in regions of the field of view that contain the specimen, and by reducing the amount of background light that reaches the image plane. First, the background light is phase-shifted by −90° by passing it through a phase-shift ring, which eliminates the phase difference between the background and the scattered light rays. | In a phase-contrast microscope, image contrast is increased in two ways: by generating constructive interference between scattered and background light rays in regions of the field of view that contain the specimen, and by reducing the amount of background light that reaches the image plane.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Mertz |first1=Jerome |title=Introduction to optical microscopy |date=2010 |publisher=Roberts |location=Greenwood Village, Colo. |isbn=978-0-9815194-8-7 |pages=189–190}}</ref> First, the background light is phase-shifted by −90° by passing it through a phase-shift ring, which eliminates the phase difference between the background and the scattered light rays. | ||

| ]When the light is then focused on the image plane (where a camera or eyepiece is placed), this phase shift causes background and scattered light rays originating from regions of the field of view that contain the sample (i.e., the foreground) to constructively ], resulting in an increase in the brightness of these areas compared to regions that do not contain the sample. Finally, the background is dimmed ~70-90% by a ] |

]When the light is then focused on the image plane (where a camera or eyepiece is placed), this phase shift causes background and scattered light rays originating from regions of the field of view that contain the sample (i.e., the foreground) to constructively ], resulting in an increase in the brightness of these areas compared to regions that do not contain the sample. Finally, the background is dimmed ~70-90% by a ] ring; this method maximizes the amount of scattered light generated by the illumination light, while minimizing the amount of illumination light that reaches the image plane. Some of the scattered light that illuminates the entire surface of the filter will be phase-shifted and dimmed by the rings, but to a much lesser extent than the background light, which only illuminates the phase-shift and gray filter rings. | ||

| The above describes ''negative phase contrast''. In its ''positive'' form, the background light is instead phase-shifted by +90°. The background light will thus be 180° out of phase relative to the scattered light. The scattered light will then be subtracted from the background light to form an image with a darker foreground and a lighter background, as shown in the first figure. |

The above describes ''negative phase contrast''. In its ''positive'' form, the background light is instead phase-shifted by +90°. The background light will thus be 180° out of phase relative to the scattered light. The scattered light will then be subtracted from the background light to form an image with a darker foreground and a lighter background, as shown in the first figure.<ref name="ZernikeI">{{cite journal | author=Frits Zernike | title=Phase contrast, a new method for the microscopic observation of transparent objects part I | journal=Physica | volume=9 | issue=7 | pages=686–698 | year=1942 | doi=10.1016/S0031-8914(42)80035-X|bibcode = 1942Phy.....9..686Z }}</ref><ref name="ZernikeII">{{cite journal | author=Frits Zernike | title=Phase contrast, a new method for the microscopic observation of transparent objects part II | journal=Physica | volume=9 | issue=10 | pages=974–980 | year=1942 | doi=10.1016/S0031-8914(42)80079-8|bibcode = 1942Phy.....9..974Z }}</ref><ref name="Richards">{{cite journal | author=Oscar Richards | title=Phase Microscopy 1954-56 | journal=Science | volume=124 | issue=3226 | pages=810–814 | year=1956 | doi=10.1126/science.124.3226.810| pmid=13380397 |bibcode = 1956Sci...124..810R }}</ref> | ||

| ==Related methods== | ==Related methods== | ||

| {{further information|differential interference contrast microscopy| |

{{further information|differential interference contrast microscopy|Hoffman modulation contrast microscopy|quantitative phase-contrast microscopy}} | ||

| [[File:S cerevisiae under DIC microscopy.jpg|thumb|left|150px | [[File:S cerevisiae under DIC microscopy.jpg|thumb|left|150px | ||

| | |

| '']'' cells imaged by ''']''']] | ||

| [[File:Phase shift image of cells in 3D.jpg|thumb|right | [[File:Phase shift image of cells in 3D.jpg|thumb|right | ||

| | A ] image of cells in culture. | | A ] image of cells in culture. | ||

| Line 69: | Line 68: | ||

| The success of the phase-contrast microscope has led to a number of subsequent ] methods. | The success of the phase-contrast microscope has led to a number of subsequent ] methods. | ||

| In 1952 ] patented what is today known as ].<ref>{{cite patent | In 1952, ] patented what is today known as ].<ref>{{cite patent | ||

| | title=INTERFERENTIAL POLARIZING DEVICE FOR STUDY OF PHASE OBJECTS | | title=INTERFERENTIAL POLARIZING DEVICE FOR STUDY OF PHASE OBJECTS | ||

| | number=US2924142 | | number=US2924142 | ||

| | inventor=Georges Nomarski}}</ref> | | inventor=Georges Nomarski}}</ref> | ||

| It enhances contrast by creating artificial shadows, as if the object is illuminated from the side. But DIC microscopy |

It enhances contrast by creating artificial shadows, as if the object is illuminated from the side. But DIC microscopy is unsuitable when the object or its container alter polarization. With the growing use of polarizing plastic containers in cell biology, DIC microscopy is increasingly replaced by ], invented by Robert Hoffman in 1975.<ref>{{cite patent | ||

| | title=Microscopy systems with rectangular illumination particularly adapted for viewing transparent object | | title=Microscopy systems with rectangular illumination particularly adapted for viewing transparent object | ||

| | number=US4200354 | | number=US4200354 | ||

| | inventor=Robert Hoffman}}</ref> | | inventor=Robert Hoffman}}</ref> | ||

| Traditional phase-contrast methods enhance contrast optically, blending brightness and phase information in single image. Since the introduction of the ] in the mid-1990s, several new digital phase-imaging methods have been developed, collectively known as ]. These methods digitally create two separate images, an ordinary ] image and a so-called ''phase-shift image''. In each image point, the phase-shift image displays the ''quantified'' phase shift induced by the object, which is proportional to the ] of the object.<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Kemmler | first1 = M. | last2 = Fratz | first2 = M. | last3 = Giel | first3 = D. | last4 = Saum | first4 = N. | last5 = Brandenburg | first5 = A. | last6 = Hoffmann | first6 = C. | title = Noninvasive time-dependent cytometry monitoring by digital holography | doi = 10.1117/1.2804926 | journal = Journal of Biomedical Optics | volume = 12 | issue = 6 | pages = 064002 | year = 2007 | pmid = 18163818 |

Traditional phase-contrast methods enhance contrast optically, blending brightness and phase information in a single image. Since the introduction of the ] in the mid-1990s, several new digital phase-imaging methods have been developed, collectively known as ]. These methods digitally create two separate images, an ordinary ] image and a so-called ''phase-shift image''. In each image point, the phase-shift image displays the ''quantified'' phase shift induced by the object, which is proportional to the ] of the object.<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Kemmler | first1 = M. | last2 = Fratz | first2 = M. | last3 = Giel | first3 = D. | last4 = Saum | first4 = N. | last5 = Brandenburg | first5 = A. | last6 = Hoffmann | first6 = C. | title = Noninvasive time-dependent cytometry monitoring by digital holography | doi = 10.1117/1.2804926 | journal = Journal of Biomedical Optics | volume = 12 | issue = 6 | pages = 064002 | year = 2007 | pmid = 18163818 |bibcode = 2007JBO....12f4002K | s2cid = 40335328 | doi-access = free }}</ref> In this way measurement of the associated optical field can remedy the halo artifacts associated with conventional phase contrast by solving an optical inverse problem to computationally reconstruct the scattering potential of the object.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kandel |first1=Mikhail |last2=Michael |first2=Fanous |last3=Catherine |first3=Best-Popescu |last4=Gabriel |first4=Popescu |title=Real-time halo correction in phase contrast imaging |journal=Biomedical Optics Express |doi=10.1364/BOE.9.000623 |pmid=29552399 |url=https://opg.optica.org/boe/fulltext.cfm?uri=boe-9-2-623&id=380814|pmc=5854064 }}</ref> | ||

| | title=Quantitative phase contrast microscopy | |||

| | publisher=Phase Holographic Imaging AB | |||

| | url=http://www.phiab.se/technology/quantitative-phase-contrast-microscopy}}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 98: | Line 94: | ||

| |lcheading=Phase-contrast microscopy}} | |lcheading=Phase-contrast microscopy}} | ||

| * by Florida State University | * by Florida State University | ||

| * (Université Paris |

* (Université Paris-Sud) | ||

| * need to know. | |||

| {{Optical microscopy}} | {{Optical microscopy}} | ||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Phase Contrast Microscopy}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Phase Contrast Microscopy}} | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 09:47, 1 June 2024

| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. The specific problem is: unreferenced, incorrect, and irrelevant information. Please help improve this article if you can. (April 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A phase-contrast microscope A phase-contrast microscope | |

| Uses | Microscopic observation of unstained biological material |

|---|---|

| Inventor | Frits Zernike |

| Manufacturer | Leica, Zeiss, Nikon, Olympus and others |

| Model | kgt |

| Related items | Differential interference contrast microscopy, Hoffman modulation-contrast microscopy, Quantitative phase-contrast microscopy |

Phase-contrast microscopy (PCM) is an optical microscopy technique that converts phase shifts in light passing through a transparent specimen to brightness changes in the image. Phase shifts themselves are invisible, but become visible when shown as brightness variations.

When light waves travel through a medium other than a vacuum, interaction with the medium causes the wave amplitude and phase to change in a manner dependent on properties of the medium. Changes in amplitude (brightness) arise from the scattering and absorption of light, which is often wavelength-dependent and may give rise to colors. Photographic equipment and the human eye are only sensitive to amplitude variations. Without special arrangements, phase changes are therefore invisible. Yet, phase changes often convey important information.

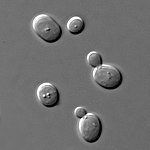

Phase-contrast microscopy is particularly important in biology. It reveals many cellular structures that are invisible with a bright-field microscope, as exemplified in the figure. These structures were made visible to earlier microscopists by staining, but this required additional preparation and death of the cells. The phase-contrast microscope made it possible for biologists to study living cells and how they proliferate through cell division. It is one of the few methods available to quantify cellular structure and components without using fluorescence. After its invention in the early 1930s, phase-contrast microscopy proved to be such an advancement in microscopy that its inventor Frits Zernike was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1953. The woman who manufactured this microscope, Caroline Bleeker, often remains uncredited.

Working principle

The basic principle to make phase changes visible in phase-contrast microscopy is to separate the illuminating (background) light from the specimen-scattered light (which makes up the foreground details) and to manipulate these differently.

The ring-shaped illuminating light (green) that passes the condenser annulus is focused on the specimen by the condenser. Some of the illuminating light is scattered by the specimen (yellow). The remaining light is unaffected by the specimen and forms the background light (red). When observing an unstained biological specimen, the scattered light is weak and typically phase-shifted by −90° (due to both the typical thickness of specimens and the refractive index difference between biological tissue and the surrounding medium) relative to the background light. This leads to the foreground (blue vector) and background (red vector) having nearly the same intensity, resulting in low image contrast.

In a phase-contrast microscope, image contrast is increased in two ways: by generating constructive interference between scattered and background light rays in regions of the field of view that contain the specimen, and by reducing the amount of background light that reaches the image plane. First, the background light is phase-shifted by −90° by passing it through a phase-shift ring, which eliminates the phase difference between the background and the scattered light rays.

When the light is then focused on the image plane (where a camera or eyepiece is placed), this phase shift causes background and scattered light rays originating from regions of the field of view that contain the sample (i.e., the foreground) to constructively interfere, resulting in an increase in the brightness of these areas compared to regions that do not contain the sample. Finally, the background is dimmed ~70-90% by a gray filter ring; this method maximizes the amount of scattered light generated by the illumination light, while minimizing the amount of illumination light that reaches the image plane. Some of the scattered light that illuminates the entire surface of the filter will be phase-shifted and dimmed by the rings, but to a much lesser extent than the background light, which only illuminates the phase-shift and gray filter rings.

The above describes negative phase contrast. In its positive form, the background light is instead phase-shifted by +90°. The background light will thus be 180° out of phase relative to the scattered light. The scattered light will then be subtracted from the background light to form an image with a darker foreground and a lighter background, as shown in the first figure.

Related methods

Further information: differential interference contrast microscopy, Hoffman modulation contrast microscopy, and quantitative phase-contrast microscopy

The success of the phase-contrast microscope has led to a number of subsequent phase-imaging methods. In 1952, Georges Nomarski patented what is today known as differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. It enhances contrast by creating artificial shadows, as if the object is illuminated from the side. But DIC microscopy is unsuitable when the object or its container alter polarization. With the growing use of polarizing plastic containers in cell biology, DIC microscopy is increasingly replaced by Hoffman modulation contrast microscopy, invented by Robert Hoffman in 1975.

Traditional phase-contrast methods enhance contrast optically, blending brightness and phase information in a single image. Since the introduction of the digital camera in the mid-1990s, several new digital phase-imaging methods have been developed, collectively known as quantitative phase-contrast microscopy. These methods digitally create two separate images, an ordinary bright-field image and a so-called phase-shift image. In each image point, the phase-shift image displays the quantified phase shift induced by the object, which is proportional to the optical thickness of the object. In this way measurement of the associated optical field can remedy the halo artifacts associated with conventional phase contrast by solving an optical inverse problem to computationally reconstruct the scattering potential of the object.

See also

References

- "The phase contrast microscope". Nobel Media AB.

- Zernike, F. (1955). "How I Discovered Phase Contrast". Science. 121 (3141): 345–349. Bibcode:1955Sci...121..345Z. doi:10.1126/science.121.3141.345. PMID 13237991.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1953". Nobel Media AB.

- Mertz, Jerome (2010). Introduction to optical microscopy. Greenwood Village, Colo.: Roberts. pp. 189–190. ISBN 978-0-9815194-8-7.

- Frits Zernike (1942). "Phase contrast, a new method for the microscopic observation of transparent objects part I". Physica. 9 (7): 686–698. Bibcode:1942Phy.....9..686Z. doi:10.1016/S0031-8914(42)80035-X.

- Frits Zernike (1942). "Phase contrast, a new method for the microscopic observation of transparent objects part II". Physica. 9 (10): 974–980. Bibcode:1942Phy.....9..974Z. doi:10.1016/S0031-8914(42)80079-8.

- Oscar Richards (1956). "Phase Microscopy 1954-56". Science. 124 (3226): 810–814. Bibcode:1956Sci...124..810R. doi:10.1126/science.124.3226.810. PMID 13380397.

- US2924142, Georges Nomarski, "INTERFERENTIAL POLARIZING DEVICE FOR STUDY OF PHASE OBJECTS"

- US4200354, Robert Hoffman, "Microscopy systems with rectangular illumination particularly adapted for viewing transparent object"

- Kemmler, M.; Fratz, M.; Giel, D.; Saum, N.; Brandenburg, A.; Hoffmann, C. (2007). "Noninvasive time-dependent cytometry monitoring by digital holography". Journal of Biomedical Optics. 12 (6): 064002. Bibcode:2007JBO....12f4002K. doi:10.1117/1.2804926. PMID 18163818. S2CID 40335328.

- Kandel, Mikhail; Michael, Fanous; Catherine, Best-Popescu; Gabriel, Popescu. "Real-time halo correction in phase contrast imaging". Biomedical Optics Express. doi:10.1364/BOE.9.000623. PMC 5854064. PMID 29552399.

External links

Library resources aboutPhase-contrast microscopy

- Optical Microscopy Primer — Phase Contrast Microscopy by Florida State University

- Phase contrast and dark field microscopes (Université Paris-Sud)

- Microscope Parts need to know.

| Optical microscopy | ||

|---|---|---|

| Illumination and contrast methods |

|  |

| Fluorescence methods | ||

| Sub-diffraction limit techniques | ||