| Revision as of 18:44, 22 September 2020 editPidgeCopetti (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users10,159 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 02:03, 23 January 2025 edit undoNihil novi (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users56,673 edits editing the lead | ||

| (44 intermediate revisions by 29 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Ukrainian Soviet journalist and playwright (1902–1949)}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=June 2018}} | |||

| {{ |

{{family name hatnote|Oleksandrovych|Halan|lang=Eastern Slavic}} | ||

| {{Multiple issues| | |||

| {{Copyedit|date=January 2025}} | |||

| {{Fan POV|date=January 2025}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2023}} | |||

| {{Infobox writer | {{Infobox writer | ||

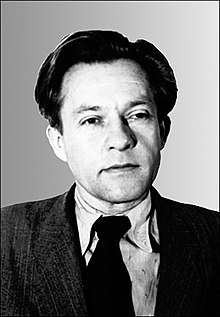

| | name = Yaroslav Halan | | name = Yaroslav Halan | ||

| | image = Галан Ярослав Олександрович.jpg | | image = Галан Ярослав Олександрович.jpg | ||

| | native_name = Ярослав Олександрович Галан | |||

| | caption = Yaroslav Olexandrovych Halan | |||

| | native_name_lang = uk | |||

| | native_name = ''{{lang-ukr|Ярослав Олександрович Галан}}'' | |||

| | pseudonym = Comrade Yaga, Volodymyr Rosovych, Ihor Semeniuk | | pseudonym = Comrade Yaga, Volodymyr Rosovych, Ihor Semeniuk | ||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1902|07|27|df=y}} | | birth_date = {{birth date|1902|07|27|df=y}} | ||

| | birth_place = ], |

| birth_place = ], Galicia-Lodomeria, Austria-Hungary<br />(now Poland) | ||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|1949|10|24|1902|08|27|df=y}} | | death_date = {{Death date and age|1949|10|24|1902|08|27|df=y}} | ||

| | death_place = ], |

| death_place = ], Ukrainian SSR, Soviet Union<br />(now Ukraine) | ||

| | resting_place = ] | | resting_place = ] | ||

| | occupation = writer, playwright, publicist, politician, propagandist, radio host | | occupation = writer, playwright, publicist, politician, propagandist, radio host | ||

| | language = ] | | language = ] | ||

| | alma_mater = {{plainlist| | |||

| | residence = ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| | nationality = | |||

| * ] | |||

| | citizenship = ] <br />] | |||

| }} | |||

| | alma_mater = ], <br />] | |||

| | genres = plays, pamphlets, articles | | genres = plays, pamphlets, articles | ||

| | subject = social contradictions | | subject = social contradictions | ||

| | movement = ] | | movement = ] | ||

| | notableworks = '']'' (1938) |

| notableworks = {{plainlist| | ||

| * '']'' (1938) | |||

| * ''Under the Golden Eagle'' (1947) | |||

| * ''Love at Dawn'' (1949) | |||

| }} | |||

| | spouse = Anna Henyk (1928–1937) | |||

| | spouse = {{plainlist| | |||

| Maria Krotkova (1944–1949) | |||

| * {{marriage|Anna Henyk|1928|1937|end=d.}} | |||

| | awards = ], <br />] | |||

| * {{marriage|Maria Krotkova|1944}} | |||

| | signature = Yaroslav_Halan_Signature_3.jpg | |||

| }} | |||

| | years_active = 1927–1949 | |||

| | awards = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | signature = Yaroslav_Halan_Signature_3.jpg | |||

| | years_active = 1927–1949 | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Yaroslav Oleksandrovych Halan''' ({{langx|uk|Ярослав Олександрович Галан}}, party nickname ''Comrade Yaga''; 27 July 1902 – 24 October 1949) was a ] writer, playwright, and publicist. | |||

| A member of the ] from 1924, he played a role in the 1946 ] that merged the ] into the ] and was controversial for the ] in his writings. | |||

| '''Yaroslav Olexandrovych Halan''' (in Ukrainian: ''Ярослав Олександрович Галан'', party nickname ''Comrade Yaga''; 27 July 1902 – 24 October 1949) was a ] anti-fascist writer, playwright, publicist, member of the ] since 1924, killed by ] in 1949. | |||

| He was assassinated in 1949 in what the Soviet government claimed was an attack by the ], though the organisation's responsibility has since become a source of dispute. | |||

| == Biography == | |||

| === Early life === | |||

| Yaroslav Halan was born on July 27, 1902, in ] to the family of Olexandr Halan, a minor post-office official. As a child he lived and studied in ]. He enjoyed a large collection of books gathered by his father, and was greatly influenced by the creativity of the Ukrainian socialist writer ]. At school, Yaroslav's critical thoughts brought him into conflict with priests who taught ]. | |||

| == Early life == | |||

| At the beginning of the ] his father, along with other "unreliable" elements who sympathized with the ], was placed in the ] by the ] authorities.<ref name=":2">{{Cite news|url=https://day.kyiv.ua/en/article/culture/yaroslav-halans-symbol-faith|title=Yaroslav Halan's symbol of faith|last=Siundiukov|first=Ihor|date=November 6, 2001|work=Day|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181014155554/https://day.kyiv.ua/en/article/culture/yaroslav-halans-symbol-faith|archive-date=October 14, 2018|url-status=}}</ref> Eventually ] was ]. | |||

| {{One source|date=January 2025|section}} | |||

| Yaroslav Oleksandrovych Halan was born on 27 July 1902 in ], then part of the ] within ]. to the family of Oleksandr Halan, a minor post-office official. As a child he lived and studied in ]. He enjoyed a large collection of books gathered by his father, and was greatly influenced by the creativity of the Ukrainian socialist writer ]. At school, Yaroslav's critical thoughts brought him into conflict with priests who taught theology. | |||

| At the beginning of the ] his father, along with other "unreliable" elements who sympathised with the ], was imprisoned at the ] by the Austro-Hungarian authorities.<ref name=":2">{{Cite news|url=https://day.kyiv.ua/en/article/culture/yaroslav-halans-symbol-faith|title=Yaroslav Halan's symbol of faith|last=Siundiukov|first=Ihor|date=6 November 2001|work=Day|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181014155554/https://day.kyiv.ua/en/article/culture/yaroslav-halans-symbol-faith|archive-date=14 October 2018}}</ref> Galicia was ]. | |||

| During the next ], in order to avoid repressions, his mother evacuated the family with the ] to ], where Yaroslav studied at the gymnasium and performed in the local theatre. Living there, Halan witnessed the events of the ]. He became familiar with ]’s agitation. Later these events formed the base of his story ''Unforgettable Days''. | |||

| During the next ], in order to avoid repressions, his mother evacuated the family with the ] to ], where Yaroslav studied at the gymnasium and performed in the local theatre. Living there, Halan witnessed the events of the ]. He became familiar with ]'s agitation. Later these events formed the base of his story ''Unforgettable Days''. | |||

| While in Rostov-on-Don, he discovered the works of Russian writers such as ], ], ], and ]. Halan often went to the theatre. Thus his obsession with this art was born, which in the future determined his decision to become a playwright. | While in Rostov-on-Don, he discovered the works of Russian writers such as ], ], ], and ]. Halan often went to the theatre. Thus his obsession with this art was born, which in the future determined his decision to become a playwright. | ||

| == Student years == | |||

| After the war Halan returned to |

After the war Halan returned to Galicia, which was annexed into the ] after the ]. In 1922 he graduated from the ]. He then studied at the ] Higher Trade School in Italy, and in 1922 enrolled in the ]. In 1926 he transferred to the ] of ], from which he graduated in 1928 (according to some sources he didn't pass the final exams<ref name=":9">{{Cite book|url=http://diasporiana.org.ua/ideologiya/1310-tereshhuk-p-istoriya-odnogo-zradnika-yaroslav-galan/|title=Story of a Traitor (Yaroslav Halan)|last=Tereshchuk|first=Petro|publisher=Canadian League for Ukraine's Liberation|year=1962|location=Toronto|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150526130403/http://diasporiana.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/books/1310/file.pdf|archive-date=26 May 2015}}</ref>). Halan then began working as a teacher of the ] and ] at a private gymnasium in ].<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.hroniky.com/news/view/5469-koleso-istorii-lutska-ukrainska-himnaziia-foto|title=Колесо історії: Луцька українська гімназія (фото)|date=17 September 2016|work=Хроніки Любарта|access-date=19 March 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180320105528/http://www.hroniky.com/news/view/5469-koleso-istorii-lutska-ukrainska-himnaziia-foto|archive-date=20 March 2018|language=uk-UA|trans-title=Wheel of History: Lutsk Ukrainian Gymnasium (photo)}}</ref> However, ten months later he was banned from teaching due to political concerns.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|url=https://coollib.com/b/151613/read|title=Жизнь замечательных людей. Ярослав Галан|last1=Beliaev|first1=Vladimir|last2=Yolkin|first2=Anatoliy|publisher=Molodaya Gvardiya|year=1962|location=Moscow|language=ru|trans-title=Life of Outstanding People. Yaroslav Halan|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140806145739/http://coollib.com:80/b/151613/read|archive-date=2014-08-06}}</ref> | ||

| In his student years Halan became active in left-wing politics. While at the University of Vienna he became a member of the workers' community |

In his student years Halan became active in left-wing politics. While at the University of Vienna he became a member of the workers' community {{lang|de|Einheit}} ("Unity"), overseen by the ]. From 1924 he was actively involved in resisting Polish rule in western Ukraine as a member of the ].<ref name=":3">{{Cite book |url=http://books.openedition.org/ceup/546 |title=Heroes and Villains: Creating National History in Contemporary Ukraine |last=Marples |first=David R. |date=23 January 2013 |publisher=Central European University Press|isbn=9786155211355 |series=Hors collection |location=Budapest |pages=125–165 |author-link=David R. Marples |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612205926/http://books.openedition.org/ceup/546 |archive-date=12 June 2018}}</ref> He joined the CPWU when he was on vacation in Przemyśl. Later, while studying in Kraków, he was elected a deputy chairman of the {{lang|pl|Życie}} student group, which was controlled by the ].<ref name=":11">{{Cite journal|date=1960|title=Автобиография Ярослава Галана|trans-title=Yaroslav Halan's Autobiography|url=http://portalus.ru/modules/shkola/rus_readme.php?subaction=showfull&id=1296132805&archive=006&start_from=&ucat=&|journal=Radianske Literaturoznavstvo|language=ru|publisher=Taras Shevchenko Institute of Literature of the NAS of the Ukrainian SSR|volume=1|issn=2413-6352|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181014180049/http://portalus.ru/modules/shkola/rus_readme.php?subaction=showfull&id=1296132805&archive=006&start_from=&ucat=&|archive-date=14 October 2018}}</ref> | ||

| === Creativity and political struggle in Poland === | === Creativity and political struggle in Poland === | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| In the 1920s, Halan's creative activity also began. In 1927 he finished work on his first significant play, ''Don Quixote from Ettenheim''. |

In the 1920s, Halan's creative activity also began. In 1927 he finished work on his first significant play, ''Don Quixote from Ettenheim''. In his play ''99%'' (1930), he condemned Ukrainian nationalism. This was followed by emphasis of class conflict in the plays ''Cargo'' (1930) and ''Cell'' (1932), which argued for the Ukrainian, Jewish and Polish proletariat to work together.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|url=http://ghetto.in.ua/article.php?ID=12&AID=81|title=Ярослав Галан: "Померлi борються..."|last=Manchuk|first=Andriy|year=2002|website=GHETTO|language=ru|trans-title=Yaroslav Halan: Dead are Figfhting...|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180319214520/http://ghetto.in.ua/article.php?ID=12&AID=81|archive-date=19 March 2018|access-date=19 March 2018}}</ref> | ||

| Halan's play ''99%'' was staged by the semi-legal |

Halan's play ''99%'' was staged by the semi-legal Lviv Workers' Theatre. On the eve of the premiere, Polish authorities launched a campaign of mass arrest against Western Ukrainian communists, sending them to the Lutsk prison. As the theatre's director and one of the key actors were arrested, the premiere was on the verge of failure. Despite risks of being arrested, the workers continued rehearsing, so that the play was presented with a delay of only one day. About 600 workers attended the premiere; for them, it was a form of protest mobilisation against repression and nationalism.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| Halan was one of the founders of the Ukrainian proletarian |

Halan was one of the founders of the Ukrainian proletarian writers' group '']''. From 1927 to 1932, along with other communist writers and members of the CPWU, he worked for the Lviv-based Ukrainian magazine ''Vikna,'' being a member of its editorial board, until it was closed by government censors.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CH%5CA%5CHalanYaroslav.htm|title=Halan, Yaroslav|website=encyclopediaofukraine.com|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612142019/http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CH%5CA%5CHalanYaroslav.htm|archive-date=12 June 2018|access-date=19 March 2018}}</ref> | ||

| Living in the ] city of Lviv, Halan frequently had to earn money by translating novels from ] into Polish.<ref name=":0" /> In 1932 he moved to Nyzhniy Bereviz, the native village of his wife, located in the ], close to ], and kept working on his own plays, stories and articles there. In the village he spread communist agitation among peasants, creating cells of the ] and the Committee for Famine Relief. Without opportunities to find work, he lived in the countryside until June 1935, when he was summoned by the CPWU to return to Lviv.<ref name=":11" /> | Living in the ] city of Lviv, Halan frequently had to earn money by translating novels from ] into Polish.<ref name=":0" /> In 1932 he moved to Nyzhniy Bereviz, the native village of his wife, located in the ], close to ], and kept working on his own plays, stories and articles there. In the village he spread communist agitation among peasants, creating cells of the ] and the Committee for Famine Relief. Without opportunities to find work, he lived in the countryside until June 1935, when he was summoned by the CPWU to return to Lviv.<ref name=":11" /> | ||

| Halan was denied ] in 1935.<ref name=":4">{{Cite news|url=https://www.segodnya.ua/oldarchive/c2256713004f33f5c22569b500443db6.html|title=Ярославу Галану удалось выйти из польских застенков|date= |

Halan was denied ] in 1935.<ref name=":4">{{Cite news|url=https://www.segodnya.ua/oldarchive/c2256713004f33f5c22569b500443db6.html|title=Ярославу Галану удалось выйти из польских застенков|date=15 December 2000|work=СЕГОДНЯ|volume=238|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612142101/https://www.segodnya.ua/oldarchive/c2256713004f33f5c22569b500443db6.html|archive-date=12 June 2018|issue=739|language=ru|trans-title=Yaroslav Halan managed to get out of the Polish dungeons}}</ref> | ||

| In 1935, Halan traveled extensively around ], giving speeches to peasants. He became an experienced propagandist and agitator. Addressing the city workers, Halan explained to them the main points of ]. In particular, he held lectures on ]'s '']'', and ]'s '']''. Together with the young communist writer ], Halan organized safe houses, wrote leaflets and proclamations, and transferred illegal literature to Lviv.<ref name=":0" /> | In 1935, Halan traveled extensively around ], giving speeches to peasants. He became an experienced propagandist and agitator. Addressing the city workers, Halan explained to them the main points of ]. In particular, he held lectures on ]'s '']'', and ]'s '']''. Together with the young communist writer ], Halan organized safe houses, wrote leaflets and proclamations, and transferred illegal literature to Lviv.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| Throughout his political career the writer was repeatedly persecuted, and twice imprisoned (for the first time in 1934). He was one of the organizers of the ] in May 1936.<ref name=":7">{{Cite |

Throughout his political career the writer was repeatedly persecuted, and twice imprisoned (for the first time in 1934). He was one of the organizers of the ] in May 1936.<ref name=":7">{{Cite news|url=https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/967138.html|title=Ярослав Галан: трагедія "зачарованого на Схід"|last=Hrabovskyi|first=Serhiy|newspaper=Радіо Свобода |date=25 July 2007|publisher=Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty|language=uk|trans-title=Yaroslav Halan: The Tragedy of the "Enchanted to the East"|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612143250/https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/967138.html|archive-date=12 June 2018|access-date=19 March 2018}}</ref> Halan also took part in a major political demonstration on 16 April 1936 in Lviv, in which the crowd was fired on by Polish police (in total, thirty workers were killed and two hundred injured).<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://wyborcza.pl/alehistoria/1,121681,15892673,Masakra_we_Lwowie.html?disableRedirects=true|title=Masakra we Lwowie|last=Leszczyński|first=Adam|date=5 May 2014|work=Gazeta Wyborcza|access-date=19 March 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612142147/http://wyborcza.pl/alehistoria/1,121681,15892673,Masakra_we_Lwowie.html?disableRedirects=true|archive-date=12 June 2018|language=pl-PL}}</ref> Halan devoted his story ''Golden Arch'' to the memory of fallen comrades.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| Participation in the Anti-Fascist Congress forced him to escape from Lviv to ], where he eventually found work at the left-wing newspaper ''Dziennik Popularny'', edited by ]. In 1937, the newspaper was closed by the authorities, and on |

Participation in the Anti-Fascist Congress forced him to escape from Lviv to ], where he eventually found work at the left-wing newspaper ''Dziennik Popularny'', edited by ]. In 1937, the newspaper was closed by the authorities, and on 8 April Halan was accused of illegal communist activism and sent to prison in Warsaw (later transferred to Lviv). Released in December 1937, Halan lived in Lviv under strict supervision by the police,<ref name=":0" /> and remained unemployed until 1939.<ref name=":11" /> | ||

| In 1937, his elder brother, a member of the CPWU, died in Lviv. After the ] and the ], as its autonomous organization, were dissolved by the ] on trumped-up accusations of spying for Poland in 1938, Halan's first wife Anna Henyk (also a member of the CPWU), who was studying at the ], ], was arrested by the ] and executed in the ].<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":0" /><ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /><ref>{{Cite book|url=http://www.lvivcenter.org/en/lia/researches/litlviv/database/anthropos/kondra-yaroslav/quotes-ref|title=Literary Lviv, 1939–1944: Memories|last=Tarnavskyi|first=Ostap |

In 1937, his elder brother, a member of the CPWU, died in Lviv. After the ] and the ], as its autonomous organization, were dissolved by the ] on trumped-up accusations of spying for Poland in 1938, Halan's first wife Anna Henyk (also a member of the CPWU), who was studying at the ], ], was arrested by the ] and executed in the ].<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":0" /><ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /><ref>{{Cite book|url=http://www.lvivcenter.org/en/lia/researches/litlviv/database/anthropos/kondra-yaroslav/quotes-ref|title=Literary Lviv, 1939–1944: Memories|last=Tarnavskyi|first=Ostap|year=1995|location=Lviv|pages=30–32|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612162959/https://lia.lvivcenter.org/en/projects/litlviv/database/anthropos/kondra-yaroslav/quotes-ref|archive-date=12 June 2018}}</ref> | ||

| == In Soviet Lviv == | |||

| After the |

After the Soviet Union ] and ] in September 1939, Halan worked for the newspaper ''Vilna Ukraina'',<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.lvivcenter.org/en/lia/researches/litlviv/database/topos/vilna-ukrayina/1939|title=Vilna Ukrayina Newspaper|website=lvivcenter.org|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612163506/https://lia.lvivcenter.org/en/projects/litlviv/database/topos/vilna-ukrayina/1939|archive-date=12 June 2018|access-date=March 19, 2018}}</ref> directed the ], and wrote more than 100 pamphlets and articles on changes taking place in the reunified lands of Western Ukraine. | ||

| {{blockquote|A group of writers such as Yaroslav Halan, ], ] and ] treated the liberation of Western Ukraine as a logical conclusion of the policy of the Communist Party, which fought for the reunification of the Ukrainian people. In this, they actively helped the party in word and deed. In return, they have already had experience with Polish prisons and oppression from their fellow countrymen. Now they could breathe a sigh of relief. That is why their smiles were so sincere and celebratory."|author=]|title="Lviv, 42 Copernicus Street"|source=''{{ill|Vitchyzna|uk|Вітчизна (часопис)}}'', 1960, No. 2, 172<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://www.lvivcenter.org/en/lia/researches/litlviv/database/anthropos/panch-petro/quotes-own|title=Lviv, Kopernyka str., 42|last=Panch|first=Petro|publisher=Vitchyzna|year=1960|volume=2|author-link=Petro Panch|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612162806/https://lia.lvivcenter.org/en/projects/litlviv/database/anthropos/panch-petro/quotes-own|archive-date=2018-06-12|issue=172}}</ref>}} | |||

| In November 1939 Halan went to Kharkiv to try to locate his vanished wife Anna Henyk. Together with the writer ] he came to the dormitory of the Medical Institute, and asked the porter for any information about her fate. The porter only gave him back a suitcase with Anna's belongings and said that she had been arrested by the NKVD, in response to which Halan burst into tears.<ref name=":5">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ojkNMwEACAAJ|title=Розповідь про неспокій|last=Smolych|first=Yuri|publisher=Radianskyi Pysmennyk|year=1968|location=Kyiv|language=uk|trans-title=Story About Inquietude|author-link=Yuri Smolych}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>], ''Lviv, Kopernyka str., 42'', Vitchyzna, 1960, issue No 2, 172<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://www.lvivcenter.org/en/lia/researches/litlviv/database/anthropos/panch-petro/quotes-own|title=Lviv, Kopernyka str., 42|last=Panch|first=Petro|publisher=Vitchyzna|year=1960|volume=2|isbn=|location=|pages=|author-link=Petro Panch|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612162806/https://lia.lvivcenter.org/en/projects/litlviv/database/anthropos/panch-petro/quotes-own|archive-date=2018-06-12|issue=172}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| In June 1941, being a journalist of the newspaper ''Vilna Ukraina'', he took his first professional vacation in ]. This was interrupted by the beginning of ] on 22 June of that year.<ref name=":6">{{Cite news|url=http://www.ukrweekly.com/old/archive/2001/420112.shtml|title=Turning the pages back... October 25, 1949|date=21 October 2001|work=The Ukrainian Weekly|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612140955/http://www.ukrweekly.com/old/archive/2001/420112.shtml|archive-date=12 June 2018|issue=42|volume=69}}</ref> | |||

| In November 1939 Halan went to Kharkiv to try to locate his vanished wife Anna Henyk. Together with the writer ] he came to the dormitory of the Medical Institute, and asked the porter for any information about her fate. The porter only gave him back a suitcase with Anna's belongings and said that she had been arrested by the NKVD, in response to which Halan burst into tears.<ref name=":5">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=ojkNMwEACAAJ|title=Розповідь про неспокій|last=Smolych|first=Yuri|publisher=Radianskyi Pysmennyk|year=1968|isbn=|location=Kyiv|pages=|language=uk|trans-title=Story About Inquietude|author-link=Yuri Smolych}}</ref> | |||

| == War period == | |||

| In June 1941, being a journalist of the newspaper ''Vilna Ukraina,'' he took his first professional vacation, in ], but didn't manage to rest for long, as on June 22 ].<ref name=":6">{{Cite news|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612140955/http://www.ukrweekly.com/old/archive/2001/420112.shtml|title=Turning the pages back... October 25, 1949|date=October 21, 2001|work=The Ukrainian Weekly|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612140955/http://www.ukrweekly.com/old/archive/2001/420112.shtml|archive-date=June 12, 2018|url-status=|issue=42, Vol. LXIX}}</ref> | |||

| When the war on the ] began, Halan arrived in Kharkiv and went to the ], having a strong desire to become a volunteer of the ] and to go to the frontline, but was denied.<ref name=":5" /> | |||

| He was evacuated to ]. In September 1941, ] summoned him to ] for working at the Polish-language magazine ''Nowe Horyzonty.'' In the days of the ], on 17 October, he was evacuated to ].<ref name=":11" /> | |||

| === War period === | |||

| When the war on the ] began, Halan arrived in Kharkiv and went to the military commissariat having a big desire to become a volunteer of the ] and to go to the frontline but was denied.<ref name=":5" /> | |||

| Later the writer arrived in ], where he served as a radio host at the Taras Shevchenko Radio Station. Then he was a special front-line correspondent of the newspaper ''Sovietskaya Ukraina'', and then ''Radianska Ukraina''.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

| He was evacuated to ]. In September 1941, ] summoned him to ] for working at the Polish-language magazine ''Nowe Horyzonty.'' In the days of the ], on October 17, he was evacuated to ].<ref name=":11" /> | |||

| {{Blockquote|text=The majority of his radio-comments have been born spontaneously. He listens to the enemy's radio shows, thinks for a while, then goes to the studio with an open microphone and without any preparations responds, expressing everything what he feels. That was a true radio-battle with all Hitler's propagandists starting from ], ], and others. The opportunity to fight like this – immediately, without paper – demonstrates a high confidence given to him by the government and the ].|author=]|title=Literaturna Ukraina|source=1962<ref name=":0" />}} | |||

| Later the writer arrived in ], where he served as a ] at the ''Taras Shevchenko Radio Station''. Then he was a special front-line correspondent of the newspaper ''Sovietskaya Ukraina'', and then ''Radianska Ukraina''.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

| In 1943, in Moscow, he met his future second wife Maria Krotkova, who was an artist.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| In October 1943, the publishing house ''Moscovskiy Bolshevik'' released a collection of 15 war stories by Halan under the title ''Front on Air''. At the end of the year, Halan moved to the ] and worked there on the frontline radio station Dnipro. | |||

| <blockquote>''«The majority of his radio-comments have been born spontaneously. He listens to the enemy's radio shows, thinks for a while, then goes to the studio with an open microphone and without any preparations responds, expressing everything what he feels. That was a true radio-battle with all ]'s propagandists starting from ], ], and others. The opportunity to fight like this – immediately, without paper – demonstrates a high confidence given to him by the ] and the ].»''</blockquote> | |||

| == Post-war == | |||

| <blockquote>], Literaturna Ukraina, 1962<ref name=":0" /></blockquote>In 1943, in Moscow, he met his future second wife Maria Krotkova, who was an artist.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| Halan, as a correspondent of the ''Radianska Ukraina'' newspaper, represented the Soviet Union at the ] in 1946.<ref name=":6" /><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bvTvCgAAQBAJ&q=Yaroslav+Halan&pg=PA301|title=The Paradox of Ukrainian Lviv: A Borderland City between Stalinists, Nazis, and Nationalists|last=Amar|first=Tarik Cyril|date=15 December 2015|publisher=Cornell University Press|isbn=9781501700835|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Halan often wrote about the ], condemning them as murderers and war criminals. He privately expressed resentment for this as outside of his field, but continued to write and publish anti-nationalist literature.<ref name=":10">{{Cite journal|last=Kysla |first=Yuliia |date=6 January 2015 |title="Пост ім. Ярослава Галана". Осінній атентат у Львові |trans-title="Post n.a. Yaroslav Halan". Autumn attempt in Lviv |url=http://uamoderna.com/blogy/yuliya-kisla/kysla-galan |journal=Ukraina Moderna |language=uk |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180320115955/http://uamoderna.com/blogy/yuliya-kisla/kysla-galan |archive-date=2018-03-20}}</ref> | |||

| In October 1943, the publishing house ''Moscovskiy Bolshevik'' released the collection of 15 Halan's war stories ''Front on Air''. At the end of the year, Halan moved to the ] and worked there on the frontline radio station ''Dnipro''. | |||

| {{blockquote|The fourteen-year-old girl can't calmly look at meat. She trembles if someone is going to cook cutlets in her presence. A few months ago, on Easter Night, armed people came to a peasant house in a village close to the town of ], and stabbed its inhabitants with knives. The girl having the eyes widened of fear was looking at the agony of her parents. The girl with horror in her eyes was looking at the agony of her parents. One of the gangsters put a knife blade to the child's neck, but at the last moment a new "idea" came to his mind: "Live in glory to ]! And to avoid you being starved to death we will leave you some food. Guys, slice pork for her!" The "guys" liked such a proposal. In a few minutes a mountain of meat made from the bleeding father and mother grew up in front of the horror-struck girl...|author=Halan|title=With Cross or Knife|source=page 70}} | |||

| During and after the war he was sharply condemning the ] – ], ], ] – as ] of the Nazi occupiers. | |||

| In his last satirical pamphlets Yaroslav Halan criticized the nationalistic and clerical reaction (particularly, the ] and the anti-Communist doctrine of the ]): ''Their Face'' (1948), ''In the service of Satan'' (1948), ''In the Face of Facts'' (1949), ''Father of Darkness and His Henchmen'' (1949), ''The Vatican Idols Thirst for Blood'' (1949, in Polish), ''Twilight of the Alien Gods'' (1948), ''What Should Not Be Forgotten'' (1947), ''The Vatican Without Mask'' (1949) etc.{{POV statement|date=January 2025}}<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://diasporiana.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/books/16936/file.pdf|title=Morality and reality: the life and times of Andrei Sheptytsḱyi|last=Magocsi|first=Paul R.|publisher=Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies|year=1989|location=Edmonton|author-link=Paul Robert Magocsi|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181014162926/http://diasporiana.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/books/16936/file.pdf|archive-date=14 October 2018}}</ref> | |||

| === Post-war times === | |||

| In 1946 Yaroslav Halan as a correspondent of the ''Radianska Ukraina'' newspaper represented the USSR at the ] of Nazi military criminals.<ref name=":6" /><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=bvTvCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA301&lpg=PA301&dq=Yaroslav+Halan#v=onepage|title=The Paradox of Ukrainian Lviv: A Borderland City between Stalinists, Nazis, and Nationalists|last=Amar|first=Tarik Cyril|date=December 15, 2015|publisher=Cornell University Press|isbn=9781501700835|location=|pages=|language=en|author-link=}}</ref> | |||

| When the Holy See discovered that Halan planned to publish his new ] pamphlet ''The Father of Darkness and His Henchmen'', ] excommunicated him in July 1949.<ref name=":7" /><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pqT1DAAAQBAJ&q=%22Yaroslav+Halan%22+excommuniated&pg=PT16|title=The Man with the Poison Gun: A Cold War Story|last=Plokhy|first=Serhii|date=8 December 2016|publisher=Oneworld Publications|isbn=9781786070449|language=en}}</ref> In response to this, Halan wrote a pamphlet ''I Spit on the Pope'', that caused a significant resonance within the Church and among believers. In the pamphlet he ironised on the '']'' released by the Vatican on 1 July, in which the Holy See had threatened to excommunicate all members of the Communist parties and active supporters of the Communists: | |||

| Yaroslav Halan wrote much about Ukrainian nationalists. In his story ''What Has No Name'' he described the ] crimes: | |||

| {{blockquote|My only consolation is that I am not alone: together with me, the Pope excommunicated at least three hundred million people, and with them I once again in full voice declare: I spit on the Pope!|author=Halan|title=With Cross or Knife|source="I Spit on the Pope!", page 112}} | |||

| <blockquote>''«Fourteen-years-old girl can’t calmly look at meat. She trembles if someone is going to cook cutlets in her presence. A few months ago, on Easter Night, armed people came to a peasant house in a village close to the town of ], and stabbed its inhabitants with knives. The girl having the eyes widened of fear was looking at the agony of her parents. The girl with horror in her eyes was looking at the agony of her parents. One of the gangsters put a knife blade to the child’s neck, but at the last moment a new “idea” came to his mind: “Live in glory to ]! And to avoid you being starved to death we will leave you some food. Guys, slice pork for her!" The "guys" liked such a proposal. In a few minutes a mountain of meat made from the bleeding father and mother grew up in front of the horror-struck girl...»''<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=ZyhNDwAAQBAJ&lpg=PA70&dq=%D0%AF%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B2%20%D0%93%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%BD%20%C2%AB%D0%A7%D0%B5%D1%82%D1%8B%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%B0%D0%B4%D1%86%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%B8%D0%BB%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%BD%D1%8F%D1%8F%20%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%B2%D0%BE%D1%87%D0%BA%D0%B0%20%D0%BD%D0%B5%20%D0%BC%D0%BE%D0%B6%D0%B5%D1%82%20%D1%81%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B9%D0%BD%D0%BE%20%D1%81%D0%BC%D0%BE%D1%82%D1%80%D0%B5%D1%82%D1%8C%20%D0%BD%D0%B0%20%D0%BC%D1%8F%D1%81%D0%BE%C2%BB&pg=PA70#v=onepage|title=С крестом или с ножом|last=Halan|first=Yaroslav|date=August 15, 1962|publisher=State Publisher of Fiction|isbn=|location=Moscow|pages=70|language=ru|trans-title=With Cross and Knife}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| In Halan's tragedy ''Under the Golden Eagle'' (1947) the writer harshly criticizes the ] administration in ] for its rude attempts to prevent Soviet soldiers ] in special camps to return to their homeland. In his play ''Love at Dawn'' (1949, published in 1951) he described the triumph of Socialism in the rural areas of Western Ukraine. | |||

| Often he was focused on counteracting the nationalistic propaganda. Nevertheless, Halan complained that these "Augean stables" were not his vocation but it had to be done by someone: | |||

| <blockquote>''«I understand: the asenisation work is a necessary and useful work, but why only me? Why should I be the only cesspool cleaner? The reader of our periodicals will involuntarily have the thought that there is only "maniac" Halan, who has clung to Ukrainian fascism like a drunk clings to the raft, the vast majority of the writers ignore this issue. It isn't needed to be explained what further conclusions the reader will make from this.»''</blockquote> | |||

| <blockquote>From Halan's letter to his friend ], on January 2, 1948.<ref name=":10">{{Cite journal|last=Kysla|first=Yulia|date=January 6, 2015|title="Пост ім. Ярослава Галана". Осінній атентат у Львові|trans-title="Post n.a. Yaroslav Halan". Autumn attempt in Lviv|url=http://uamoderna.com/blogy/yuliya-kisla/kysla-galan|journal=Ukraina Moderna|language=Ukrainian|volume=|pages=|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180320115955/http://uamoderna.com/blogy/yuliya-kisla/kysla-galan|archive-date=2018-03-20|via=}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| In his last satirical pamphlets Yaroslav Halan criticized the nationalistic and clerical reaction (particularly, the ] and the anti-Communist doctrine of the ]): ''Their Face'' (1948), ''In the service of Satan'' (1948), ''In the Face of Facts'' (1949), ''Father of Darkness and His Henchmen'' (1949), ''The Vatican Idols Thirst for Blood'' (1949, in Polish), ''Twilight of the Alien Gods'' (1948), ''What Should Not Be Forgotten'' (1947), ''The Vatican Without Mask'' (1949) etc.<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://diasporiana.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/books/16936/file.pdf|title=Morality and reality: the life and times of Andrei Sheptytsḱyi|last=Magocsi|first=Paul R.|publisher=Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies|year=1989|isbn=|location=Edmonton|pages=|author-link=Paul Robert Magocsi|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181014162926/http://diasporiana.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/books/16936/file.pdf|archive-date=October 14, 2018}}</ref> | |||

| When the ] had discovered that Halan is going to publish his new ] pamphlet ''Father of Darkness and His Henchmen'', in July 1949 the Pope Pius XII ] him.<ref name=":7" /><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=pqT1DAAAQBAJ&pg=PT16&lpg=PT16&dq=%22Yaroslav+Halan%22+excommuniated#v=onepage|title=The Man with the Poison Gun: A Cold War Story|last=Plokhy|first=Serhii|date=December 8, 2016|publisher=Oneworld Publications|isbn=9781786070449|location=|pages=|language=en}}</ref> In response to this, Halan wrote a pamphlet ''I Spit on the Pope'', that caused a significant resonance within the Church and among believers. In the pamphlet he ironized on the '']'' released by the Vatican on July 1, in which the Holy See had threatened to excommunicate all members of the Communist parties and active supporters of the Communists: | |||

| <blockquote>''«My only consolation is that I am not alone: together with me, the Pope excommunicated at least three hundred million people, and with them I once again in full voice declare: I spit on the Pope!»''<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=ZyhNDwAAQBAJ&lpg=PA9&dq=%D0%BF%D0%BB%D1%8E%D1%8E%20%D0%BD%D0%B0%20%D0%BF%D0%B0%D0%BF%D1%83&pg=PP1#v=onepage|title=С крестом или с ножом|last=Halan|first=Yaroslav|date=August 15, 1962|publisher=State Publisher of Fiction|isbn=|location=Moscow|pages=112|language=ru|trans-title=With Cross or With Knife|chapter=Плюю на папу!|trans-chapter=I Spit of the Pope!}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| == Assassination == | == Assassination == | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Halan was assassinated on 24 October 1949 in his home office, which was situated at Hvadiyska street in Lviv. He received eleven blows to the head with an axe.<ref name=":6" /> His blood spilled on the manuscript of his new article, ''Greatness of the Liberated Human'', which celebrated the tenth anniversary of the [Soviet annexation of western Ukraine. | |||

| The killers – two students of the ], Ilariy Lukashevych and Mykhailo Stakhur – |

The killers – two students of the ], Ilariy Lukashevych and Mykhailo Stakhur – were accused of orchestrating the assassination at the behest of the OUN's leadership. On the eve of the murder Lukashevych gained the writer's confidence, so the students were let into the house. They came to the apartment under the pretext of being discriminated against at the university and seeking his help.<ref name=":2" /> When Lukashevych gave a signal, Stakhur attacked the writer with the axe.<ref name=":8">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6OXJCQAAQBAJ&q=halan+stakhur+oun&pg=PA393|title=Stepan Bandera: The Life and Afterlife of a Ukrainian Nationalist: Fascism, Genocide, and Cult|last=Rossolinski|first=Grzegorz|date=2014|publisher=Columbia University Press|isbn=9783838206844|pages=393|language=en|author-link=Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe}}</ref> After Stakhur was convinced that Halan was dead, they tied up the housekeeper and escaped. | ||

| The ] (MGB) accused the Ukrainian nationalists of his murder, while the OUN claimed that it was a Soviet provocation in order to start a new wave of repressions against locals. | The ] (MGB) accused the Ukrainian nationalists of his murder, while the OUN claimed that it was a Soviet provocation in order to start a new wave of repressions against locals. | ||

| ], the leader of the Ukrainian SSR at that time, took personal control of the investigation.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=uv1zv4FZhFUC& |

], the leader of the Ukrainian SSR at that time, took personal control of the investigation.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uv1zv4FZhFUC&q=%22Yaroslav+Galan%22+church&pg=PT276|title=Memoirs of Nikita Khrushchev|last=Khrushchev|first=Nikita Sergeevich|date=2004|publisher=Penn State Press|isbn=0271028610|pages=262|language=en}}</ref> In 1951, the MGB agent ] infiltrated into the OUN underground network and managed to find Stakhur, who himself bragged about the assassination of Halan.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/books/2017/01/now-there-was-no-way-back-me-strange-story-bogdan-stashinsky|title="By now, there was no way back for me": the strange story of Bogdan Stashinsky|last=Jacobson|first=Gavin|website=New Statesman|date=19 January 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612141152/https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/books/2017/01/now-there-was-no-way-back-me-strange-story-bogdan-stashinsky|archive-date=12 June 2018|access-date=20 March 2018}}</ref> He was arrested on 10 July, and afterwards fully admitted his responsibility for the crime during the trial. According to Stakhur, he did that because of the writer's critical statements on the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, ] and the Vatican.<ref name=":8" /> | ||

| On |

On 16 October 1951 the military tribunal of the ] sentenced Mykhailo Stakhur to death by hanging. He was executed that day. | ||

| Since the ], the role of the UPA in Halan's assassination has increasingly come under scrutiny.<ref name=":9" /> Historian ] has noted that the methods of the assassination were more similar to the prior killing of ], which was organised by Soviet intelligence, than typical OUN or UPA assassinations; in contrast to the usage of an axe by Halan's killers, the OUN usually conducted its killings with firearms. Petro Duzhyi, a soldier of the UPA, claimed in a 1993 interview with historian Mykola Oleksyuk that ] expressed a desire to have Halan killed; according to Duzhyi, Strokach had said during an interrogation that Halan's support for arresting the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church's leadership had sparked a popular uprising.<ref name=":3" /> Ukrainian literary historian Yuliia Kysla also describes the assassination as a false-flag operation, referring to Lukashevych and Stakhur as being part of one of many groups which were supposedly part of the UPA, but were actually under the control of the Soviet government.<ref name=":10" /> ], the leader of the UPA, would continue to claim that the assassination had been organised by the MGB in interviews after the Soviet Union's dissolution.<ref name="Vedeneyev-Shevchenko">{{Cite news |url=https://www.2000.ua/v-nomere/aspekty/istorija/priznalsja-zabirajte_arhiv_art.htm |title=Признался!.. Забирайте! |last1=Vedeneyev |first1=Dmitri |date=14 February 2002 |work=2000 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612140824/https://www.2000.ua/v-nomere/aspekty/istorija/priznalsja-zabirajte_arhiv_art.htm |archive-date=12 June 2018 |last2=Shevchenko |first2=Sergei |language=ru |trans-title=He confessed!... Take him away}}</ref> | |||

| The possibility that he was assassinated by the OUN or UPA, however, has not been conclusively ruled out. Dmitry Vedeneyev and Sergei Shevchenko, writers for the Ukrainian newspaper ''2000'', compared Halan to ] in 2002 in reference to the latter's ] and noted that Halan's criticism of the Catholic Church made him extremely unpopular in deeply-religious Galicia.<ref name="Vedeneyev-Shevchenko"/> Marples also notes that there are several problems with most accounts of Halan's assassination and the aftermath, arguing that it is effectively impossible to determine who was responsible for his assassination given that he was equally loathed by both the Soviet government and the UPA at the time of his death.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

| The assassination of Halan caused tightening of measures against the nationalist Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), which continued insurgent activities against the Soviet power in Western Ukraine. All the leadership of the MGB arrived in Lviv, ] himself worked there for several months. One of the consequences of the murder of Halan was the elimination of the UPA leader ] four months later.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=-WsqDgAAQBAJ&lpg=PT349&dq=galan%20sudoplatov&pg=PT349#v=onepage|title=Павел Судоплатов. Волкодав Сталина|last=Sever|first=Alexandr|date=February 8, 2018|publisher=Litres|isbn=9785457691995|location=|pages=|language=ru|trans-title=Pavel Sudoplatov. Stalin's Wolfhound}}</ref> | |||

| The assassination of Halan resulted in increased repression of the UPA, which continued its insurgency against the Soviet government. All the leadership of the MGB arrived in Lviv, ] himself worked there for several months. One of the consequences of the murder of Halan was the elimination of the UPA leader ] four months later.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-WsqDgAAQBAJ&q=galan%20sudoplatov&pg=PT349|title=Павел Судоплатов. Волкодав Сталина|last=Sever|first=Alexandr|date=8 February 2018|publisher=Litres|isbn=9785457691995|language=ru|trans-title=Pavel Sudoplatov. Stalin's Wolfhound}}</ref> | |||

| == Evaluations by contemporaries == | |||

| [[File:Ярослав Галан за работой.jpg|thumb|260x260px| | |||

| The writer at his home office where he usually worked. 1947.]] | |||

| == Evaluations by contemporaries == | |||

| <blockquote>''«Yaroslav Halan is a talented publicist, was a progressive writer in the past. Nowadays he still is the most advanced one among non-party writers. But he's infected with the Western European bourgeois "spirit". Has little respect for Soviet people. Considers them not civilized enough. But just inwardly. In general terms, he understands the policy of the party, but in his opinion, the party makes great mistakes with regards to peasants in Western Ukraine. Halan places responsibility for these mistakes on the regional committee of the ], local institutions of the ] and the local Soviet authorities. Believes in Moscow. Doesn't want to join the party (he was advised to) due to being an individualist, and also in order to keep his hands, mind, and words free. He thinks if he joins the party, he will lose this .»''</blockquote> | |||

| {{Copy to Wikiquote|section=section}} | |||

| ] | |||

| <blockquote>"Yaroslav Halan is a talented publicist, was a progressive writer in the past. Nowadays he still is the most advanced one among non-party writers. But he's infected with the Western European bourgeois "spirit". Has little respect for Soviet people. Considers them not civilized enough. But just inwardly. In general terms, he understands the policy of the party, but in his opinion, the party makes great mistakes with regards to peasants in Western Ukraine. Halan places responsibility for these mistakes on the regional committee of the ], local institutions of the ] and the local Soviet authorities. Believes in Moscow. Doesn't want to join the party (he was advised to) due to being an individualist, and also in order to keep his hands, mind, and words free. He thinks if he joins the party, he will lose this ."</blockquote> | |||

| <blockquote>Extract from the report of the literary critic G. Parkhomenko to the Central Committee of the ] |

<blockquote>Extract from the report of the literary critic G. Parkhomenko to the Central Committee of the ], 15 December 1947.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.golos.com.ua/rus/article/156178|title=Ярослав Галан. Откроют ли архивы КГБ тайну его убийства?|last=Filipchuk|first=Natalia|date=24 October 2009|work=Holos Ukrainy|access-date=20 March 2018|trans-title=Yaroslav Halan. Could KGB Archives Reveal the Mystery of his Murder?|language=ru|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612142721/http://www.golos.com.ua/rus/article/156178|archive-date=12 June 2018}}</ref></blockquote> | ||

| In 1962, in ], Olexandr Matla, aka Petro Tereschuk, a pro-nationalist historian from the ], published the brochure ''History of a Traitor (Yaroslav Halan)'', in which he accused Halan of being an informer of both Polish and Soviet intelligence services, and of helping them to oppress nationalists and even some pro-Soviet writers from Western Ukraine such as ], who moved from Lviv to Kharkiv in the 1930s and was killed during the ]. | In 1962, in ], Olexandr Matla, aka Petro Tereschuk, a pro-nationalist historian from the ], published the brochure ''History of a Traitor (Yaroslav Halan)'', in which he accused Halan of being an informer of both Polish and Soviet intelligence services, and of helping them to oppress nationalists and even some pro-Soviet writers from Western Ukraine such as ], who moved from Lviv to Kharkiv in the 1930s and was killed during the ]. | ||

| <blockquote> |

<blockquote>" has used his undeniable publicistic talent to serve the enemy, thereby placing himself outside the Ukrainian people. He has directed his energy and creative mind against his own people and their interests. An outrageous egoist, egocentrist, money lover, slanderer, cynic, provocator, agent of two intelligence services, misanthrope, falsificator, speculator, and an informer are all the characteristics of Yaroslav Halan."</blockquote> | ||

| <blockquote>Petro Tereschuk, History of a Traitor (Yaroslav Halan), Canadian League for Ukraine's Liberation, Toronto, 1962.<ref name=":9" /></blockquote> | <blockquote>Petro Tereschuk, History of a Traitor (Yaroslav Halan), Canadian League for Ukraine's Liberation, Toronto, 1962.<ref name=":9" /></blockquote> | ||

| <blockquote> |

<blockquote>"Yaroslav is an erudite, artist, polemicist, politician and undoubtedly an international-level journalist. I was amazed at his knowledge of the languages: German, French, Italian, Polish, Jewish, Russian. Picking up any newspaper or document he leafs through, reads it and writes something down. I was also surprised by his efficiency in work, interest in everything, an exceptional ability to "seek" and "raise" topics, problems, his persistent work on processing the material."</blockquote> | ||

| <blockquote>], a Ukrainian Soviet writer, who worked with Halan at the Nuremberg Trial in 1946.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=ZyhNDwAAQBAJ& |

<blockquote>], a Ukrainian Soviet writer, who worked with Halan at the Nuremberg Trial in 1946.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZyhNDwAAQBAJ&q=%D0%AE%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%B9%20%D1%8F%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B2%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9%20%D0%AF%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B2%20%D0%B3%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%BD&pg=PA9|title=С крестом или с ножом|last=Halan|first=Yaroslav|date=15 August 1962|publisher=State Publisher of Fiction|location=Moscow|pages=8|language=ru|trans-title=With Cross or With Knife}}</ref></blockquote> | ||

| <blockquote> |

<blockquote>"n 1949 I witnessed an unusual event. On 2 October Yaroslav Halan spoke in Lviv University. It turned out to be his last speech. We condemned him but his presentation surprised me. He spoke as an intelligent person defending Ukrainian culture. It had nothing to do with the series of his pamphlets "I spit on Pope!" Halan turned out to be a totally different man. Several days later he was killed."</blockquote> | ||

| <blockquote>], a Ukrainian anti-Communist ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://museum.khpg.org/en/index.php?id=1454600328|title=And here is what I'll tell |

<blockquote>], a Ukrainian anti-Communist ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://museum.khpg.org/en/index.php?id=1454600328|title=And here is what I'll tell you... M.Horyn's interview|last=Kipiani|first=Vakhtang|date=19 December 1999|website=museum.khpg.org|language=en|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181014172015/http://museum.khpg.org/en/index.php?id=1454600328|archive-date=14 October 2018|access-date=2018-10-14}}</ref></blockquote> | ||

| == Homage == | == Homage == | ||

| Line 156: | Line 161: | ||

| *The ], in 1958, filmed Halan's work ''Under the Golden Eagle'', but the film wasn't released as "too anti-American". Writer's work '']'' was filmed in 1989 by the ] studio. | *The ], in 1958, filmed Halan's work ''Under the Golden Eagle'', but the film wasn't released as "too anti-American". Writer's work '']'' was filmed in 1989 by the ] studio. | ||

| * In 1962, 1970 and 1976, the USSR Post issued postal envelopes with a portrait of Yaroslav Halan. | * In 1962, 1970 and 1976, the USSR Post issued postal envelopes with a portrait of Yaroslav Halan. | ||

| * A huge monument to Yaroslav Halan was installed in ] in 1972. Besides, the square where the monument was situated was named after Halan. In 1992, on the eve of the Vatican |

* A huge monument to Yaroslav Halan was installed in ] in 1972. Besides, the square where the monument was situated was named after Halan. In 1992, on the eve of the Vatican officials' visit, the local authorities demolished the monument, and its metal was used for constructing a monument to the ], a nationalist organization which Halan fought with. There was another monument to the writer in the city Park of Culture installed in 1957 and demolished in the 1960s. A monument to Halan also existed in ], Lviv Region. Demolished in the 1990s. | ||

| * In 1960, Halan's personal apartment at Hvardiyska street, 18, where he lived in 1944-1949, was turned into his personal museum. The museum stored writer's personal belongings, documents, and materials about his literary and social activity, publications of his works. In the 1990s, it was under threat of closure, but eventually, it was transformed into the museum ]. | * In 1960, Halan's personal apartment at Hvardiyska street, 18, where he lived in 1944-1949, was turned into his personal museum. The museum stored writer's personal belongings, documents, and materials about his literary and social activity, publications of his works. In the 1990s, it was under threat of closure, but eventually, it was transformed into the museum ]. | ||

| *From 1964 to 1991, the ''Yaroslav Halan Prize'' was awarded by the ] for the best propagandistic journalism. | *From 1964 to 1991, the ''Yaroslav Halan Prize'' was awarded by the ] for the best propagandistic journalism. | ||

| Line 163: | Line 168: | ||

| *Halan's works in three volumes were published in Kyiv in 1977–1978. | *Halan's works in three volumes were published in Kyiv in 1977–1978. | ||

| *From 1967 to 1987, the Lviv-based publisher ''Kameniar'' issued the anti-fascist and anti-clerical almanac ''Post Named After Yaroslav Halan''. In total, 22 issues were published. | *From 1967 to 1987, the Lviv-based publisher ''Kameniar'' issued the anti-fascist and anti-clerical almanac ''Post Named After Yaroslav Halan''. In total, 22 issues were published. | ||

| * The streets named after Yaroslav Halan existed in ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] but they were renamed within the ].<ref>. Beyond Zbruch. |

* The streets named after Yaroslav Halan existed in ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] but they were renamed within the ].<ref>. Beyond Zbruch. 28 March 2014</ref> In Soviet times, in ], the name of Yaroslav Halan was given to the street where he worked at the ''Taras Shevchenko Radio Station''. After the USSR collapsed, the street recovered it historical name Proviantskaya. | ||

| * In ], ], ], ], ], and ], there are still the streets bearing the name of Halan. | * In ], ], ], ], ], and ], there are still the streets bearing the name of Halan. | ||

| *The ] (]) and ] (]) received the name of Yaroslav Halan. Renamed in the 1990s. | *The ] (]) and ] (]) received the name of Yaroslav Halan. Renamed in the 1990s. | ||

| Line 169: | Line 174: | ||

| * The ], established by the Soviet authorities in the ] building, and ] received the name of Yaroslav Halan. Renamed in the 1990s. One of the district libraries in ] still bears the writer's name. | * The ], established by the Soviet authorities in the ] building, and ] received the name of Yaroslav Halan. Renamed in the 1990s. One of the district libraries in ] still bears the writer's name. | ||

| *In 1954, the Yaroslav Halan Cinema was built in ], Lviv. Renamed in the 1990s, nowadays abandoned. | *In 1954, the Yaroslav Halan Cinema was built in ], Lviv. Renamed in the 1990s, nowadays abandoned. | ||

| *Halan's name was given to ]es in the following villages: Vuzlove (], Lviv |

*Halan's name was given to ]es in the following villages: Vuzlove (], Lviv Oblast), Dytiatychi (], Lviv Region), Mistky (], Lviv Oblast), Turynka (], Lviv Oblast) Volodymyrivka (], ]), Seredniy Bereziv (], ]), Hnylytsi (], ]). | ||

| * The name of Yaroslav Halan was given to a passenger steamer of the Belsky river shipping company, which operated on the ]-] line. Currently out of use. | * The name of Yaroslav Halan was given to a passenger steamer of the Belsky river shipping company, which operated on the ]-] line. Currently out of use. | ||

| * In 2012, the ] adopted the resolution ''About the celebration of the 110th anniversary of the birth of the famous Ukrainian anti-fascist writer Yaroslav Oleksandrovych Halan''. | * In 2012, the ] adopted the resolution ''About the celebration of the 110th anniversary of the birth of the famous Ukrainian anti-fascist writer Yaroslav Oleksandrovych Halan''. | ||

| Line 299: | Line 304: | ||

| * <small>''Рубльов О. С.'', ''Черченко Ю. А.'' Сталінщина й доля західноукраїнської інтелігенції (20—50-ті роки XX ст.) – К., 1994.</small> | * <small>''Рубльов О. С.'', ''Черченко Ю. А.'' Сталінщина й доля західноукраїнської інтелігенції (20—50-ті роки XX ст.) – К., 1994.</small> | ||

| * <small>''Бантышев А. Ф.'', ''Ухаль А. М.'' Убийство на заказ: кто же организовал убийство Ярослава Галана? Опыт независимого расследования. – Ужгород, 2002.</small> | * <small>''Бантышев А. Ф.'', ''Ухаль А. М.'' Убийство на заказ: кто же организовал убийство Ярослава Галана? Опыт независимого расследования. – Ужгород, 2002.</small> | ||

| * <small>''Цегельник Я.'' Славен у віках. Образ Львова у спадщині Я. Галана // Жовтень. – 1982. – No. 3 (449). – С. 72—74. – ISSN |

* <small>''Цегельник Я.'' Славен у віках. Образ Львова у спадщині Я. Галана // Жовтень. – 1982. – No. 3 (449). – С. 72—74. – {{ISSN|0131-0100}}.</small> | ||

| * <small>"Боротьба трудящихся Львівщини проти Нiмецько-фашистьских загарбників". Львів, вид-во "Вільна Україна", 1949.</small> | * <small>"Боротьба трудящихся Львівщини проти Нiмецько-фашистьских загарбників". Львів, вид-во "Вільна Україна", 1949.</small> | ||

| * <small>''Буряк Борис'', Ярослав Галан. В кн.: Галан Я., Избранное. М., Гослитиздат, 1958, стр. 593–597.</small> | * <small>''Буряк Борис'', Ярослав Галан. В кн.: Галан Я., Избранное. М., Гослитиздат, 1958, стр. 593–597.</small> | ||

| Line 337: | Line 342: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 358: | Line 363: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 368: | Line 373: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 02:03, 23 January 2025

Ukrainian Soviet journalist and playwright (1902–1949) In this name that follows Eastern Slavic naming customs, the patronymic is Oleksandrovych and the family name is Halan.This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Yaroslav Halan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Ярослав Олександрович Галан |

| Born | (1902-07-27)27 July 1902 Dynów, Galicia-Lodomeria, Austria-Hungary (now Poland) |

| Died | 24 October 1949(1949-10-24) (aged 47) Lviv, Ukrainian SSR, Soviet Union (now Ukraine) |

| Resting place | Lychakiv Cemetery |

| Pen name | Comrade Yaga, Volodymyr Rosovych, Ihor Semeniuk |

| Occupation | writer, playwright, publicist, politician, propagandist, radio host |

| Language | Ukrainian |

| Alma mater | |

| Genres | plays, pamphlets, articles |

| Subject | social contradictions |

| Literary movement | socialist realism |

| Years active | 1927–1949 |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards | |

| Spouse |

|

| Signature | |

| |

Yaroslav Oleksandrovych Halan (Ukrainian: Ярослав Олександрович Галан, party nickname Comrade Yaga; 27 July 1902 – 24 October 1949) was a Soviet Ukrainian writer, playwright, and publicist.

A member of the Communist Party of Western Ukraine from 1924, he played a role in the 1946 Synod of Lviv that merged the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church into the Russian Orthodox Church and was controversial for the anti-Catholicism in his writings.

He was assassinated in 1949 in what the Soviet government claimed was an attack by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, though the organisation's responsibility has since become a source of dispute.

Early life

| This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help improve this article by introducing citations to additional sources. Find sources: "Yaroslav Halan" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2025) |

Yaroslav Oleksandrovych Halan was born on 27 July 1902 in Dynów, then part of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria within Austria-Hungary. to the family of Oleksandr Halan, a minor post-office official. As a child he lived and studied in Przemyśl. He enjoyed a large collection of books gathered by his father, and was greatly influenced by the creativity of the Ukrainian socialist writer Ivan Franko. At school, Yaroslav's critical thoughts brought him into conflict with priests who taught theology.

At the beginning of the First World War his father, along with other "unreliable" elements who sympathised with the Russian Empire, was imprisoned at the Thalerhof internment camp by the Austro-Hungarian authorities. Galicia was taken by the Russians.

During the next Austrian offensive, in order to avoid repressions, his mother evacuated the family with the retreating Russian army to Rostov-on-Don, where Yaroslav studied at the gymnasium and performed in the local theatre. Living there, Halan witnessed the events of the October Revolution. He became familiar with Lenin's agitation. Later these events formed the base of his story Unforgettable Days.

While in Rostov-on-Don, he discovered the works of Russian writers such as Leo Tolstoy, Maxim Gorky, Vissarion Belinsky, and Anton Chekhov. Halan often went to the theatre. Thus his obsession with this art was born, which in the future determined his decision to become a playwright.

Student years

After the war Halan returned to Galicia, which was annexed into the Second Polish Republic after the Treaty of Riga. In 1922 he graduated from the Peremyshl Ukrainian Gymnasium. He then studied at the Trieste Higher Trade School in Italy, and in 1922 enrolled in the University of Vienna. In 1926 he transferred to the Jagiellonian University of Kraków, from which he graduated in 1928 (according to some sources he didn't pass the final exams). Halan then began working as a teacher of the Polish language and literature at a private gymnasium in Lutsk. However, ten months later he was banned from teaching due to political concerns.

In his student years Halan became active in left-wing politics. While at the University of Vienna he became a member of the workers' community Einheit ("Unity"), overseen by the Communist Party of Austria. From 1924 he was actively involved in resisting Polish rule in western Ukraine as a member of the Communist Party of Western Ukraine. He joined the CPWU when he was on vacation in Przemyśl. Later, while studying in Kraków, he was elected a deputy chairman of the Życie student group, which was controlled by the Communist Party of Poland.

Creativity and political struggle in Poland

In the 1920s, Halan's creative activity also began. In 1927 he finished work on his first significant play, Don Quixote from Ettenheim. In his play 99% (1930), he condemned Ukrainian nationalism. This was followed by emphasis of class conflict in the plays Cargo (1930) and Cell (1932), which argued for the Ukrainian, Jewish and Polish proletariat to work together.

Halan's play 99% was staged by the semi-legal Lviv Workers' Theatre. On the eve of the premiere, Polish authorities launched a campaign of mass arrest against Western Ukrainian communists, sending them to the Lutsk prison. As the theatre's director and one of the key actors were arrested, the premiere was on the verge of failure. Despite risks of being arrested, the workers continued rehearsing, so that the play was presented with a delay of only one day. About 600 workers attended the premiere; for them, it was a form of protest mobilisation against repression and nationalism.

Halan was one of the founders of the Ukrainian proletarian writers' group Horno. From 1927 to 1932, along with other communist writers and members of the CPWU, he worked for the Lviv-based Ukrainian magazine Vikna, being a member of its editorial board, until it was closed by government censors.

Living in the Polish-controlled city of Lviv, Halan frequently had to earn money by translating novels from German into Polish. In 1932 he moved to Nyzhniy Bereviz, the native village of his wife, located in the Carpathian mountains, close to Kolomyia, and kept working on his own plays, stories and articles there. In the village he spread communist agitation among peasants, creating cells of the International Red Aid and the Committee for Famine Relief. Without opportunities to find work, he lived in the countryside until June 1935, when he was summoned by the CPWU to return to Lviv.

Halan was denied Soviet citizenship in 1935.

In 1935, Halan traveled extensively around Prykarpattia, giving speeches to peasants. He became an experienced propagandist and agitator. Addressing the city workers, Halan explained to them the main points of Marxist theory. In particular, he held lectures on Friedrich Engels's Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, and Karl Marx's Wage Labour and Capital. Together with the young communist writer Olexa Havryliuk, Halan organized safe houses, wrote leaflets and proclamations, and transferred illegal literature to Lviv.

Throughout his political career the writer was repeatedly persecuted, and twice imprisoned (for the first time in 1934). He was one of the organizers of the Lviv Anti-Fascist Congress of Cultural Workers in May 1936. Halan also took part in a major political demonstration on 16 April 1936 in Lviv, in which the crowd was fired on by Polish police (in total, thirty workers were killed and two hundred injured). Halan devoted his story Golden Arch to the memory of fallen comrades.

Participation in the Anti-Fascist Congress forced him to escape from Lviv to Warsaw, where he eventually found work at the left-wing newspaper Dziennik Popularny, edited by Wanda Wasilewska. In 1937, the newspaper was closed by the authorities, and on 8 April Halan was accused of illegal communist activism and sent to prison in Warsaw (later transferred to Lviv). Released in December 1937, Halan lived in Lviv under strict supervision by the police, and remained unemployed until 1939.

In 1937, his elder brother, a member of the CPWU, died in Lviv. After the Communist Party of Poland and the Communist Party of Western Ukraine, as its autonomous organization, were dissolved by the Comintern on trumped-up accusations of spying for Poland in 1938, Halan's first wife Anna Henyk (also a member of the CPWU), who was studying at the Kharkiv Medical Institute, USSR, was arrested by the NKVD and executed in the Great Purge.

In Soviet Lviv

After the Soviet Union annexed Western Ukraine and Western Belarus in September 1939, Halan worked for the newspaper Vilna Ukraina, directed the Maria Zankovetska Theatre, and wrote more than 100 pamphlets and articles on changes taking place in the reunified lands of Western Ukraine.

A group of writers such as Yaroslav Halan, Petro Kozlaniuk, Stepan Tudor and Olexa Havryliuk treated the liberation of Western Ukraine as a logical conclusion of the policy of the Communist Party, which fought for the reunification of the Ukrainian people. In this, they actively helped the party in word and deed. In return, they have already had experience with Polish prisons and oppression from their fellow countrymen. Now they could breathe a sigh of relief. That is why their smiles were so sincere and celebratory."

— Petro Panch, "Lviv, 42 Copernicus Street", Vitchyzna [uk], 1960, No. 2, 172

In November 1939 Halan went to Kharkiv to try to locate his vanished wife Anna Henyk. Together with the writer Yuri Smolych he came to the dormitory of the Medical Institute, and asked the porter for any information about her fate. The porter only gave him back a suitcase with Anna's belongings and said that she had been arrested by the NKVD, in response to which Halan burst into tears.

In June 1941, being a journalist of the newspaper Vilna Ukraina, he took his first professional vacation in Crimea. This was interrupted by the beginning of Operation Barbarossa on 22 June of that year.

War period

When the war on the Eastern Front began, Halan arrived in Kharkiv and went to the military commissariat, having a strong desire to become a volunteer of the Red Army and to go to the frontline, but was denied.

He was evacuated to Ufa. In September 1941, Alexander Fadeyev summoned him to Moscow for working at the Polish-language magazine Nowe Horyzonty. In the days of the Battle for Moscow, on 17 October, he was evacuated to Kazan.

Later the writer arrived in Saratov, where he served as a radio host at the Taras Shevchenko Radio Station. Then he was a special front-line correspondent of the newspaper Sovietskaya Ukraina, and then Radianska Ukraina.

The majority of his radio-comments have been born spontaneously. He listens to the enemy's radio shows, thinks for a while, then goes to the studio with an open microphone and without any preparations responds, expressing everything what he feels. That was a true radio-battle with all Hitler's propagandists starting from Goebbels, Dietrich, and others. The opportunity to fight like this – immediately, without paper – demonstrates a high confidence given to him by the government and the Central Committee of the CPSU(b).

— Vladimir Belyaev, Literaturna Ukraina, 1962

In 1943, in Moscow, he met his future second wife Maria Krotkova, who was an artist.

In October 1943, the publishing house Moscovskiy Bolshevik released a collection of 15 war stories by Halan under the title Front on Air. At the end of the year, Halan moved to the recently liberated Kharkiv and worked there on the frontline radio station Dnipro.

Post-war

Halan, as a correspondent of the Radianska Ukraina newspaper, represented the Soviet Union at the Nuremberg trials in 1946.

Halan often wrote about the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists, condemning them as murderers and war criminals. He privately expressed resentment for this as outside of his field, but continued to write and publish anti-nationalist literature.

The fourteen-year-old girl can't calmly look at meat. She trembles if someone is going to cook cutlets in her presence. A few months ago, on Easter Night, armed people came to a peasant house in a village close to the town of Sarny, and stabbed its inhabitants with knives. The girl having the eyes widened of fear was looking at the agony of her parents. The girl with horror in her eyes was looking at the agony of her parents. One of the gangsters put a knife blade to the child's neck, but at the last moment a new "idea" came to his mind: "Live in glory to Stepan Bandera! And to avoid you being starved to death we will leave you some food. Guys, slice pork for her!" The "guys" liked such a proposal. In a few minutes a mountain of meat made from the bleeding father and mother grew up in front of the horror-struck girl...

— Halan, With Cross or Knife, page 70

In his last satirical pamphlets Yaroslav Halan criticized the nationalistic and clerical reaction (particularly, the Greek Catholic Church and the anti-Communist doctrine of the Holy See): Their Face (1948), In the service of Satan (1948), In the Face of Facts (1949), Father of Darkness and His Henchmen (1949), The Vatican Idols Thirst for Blood (1949, in Polish), Twilight of the Alien Gods (1948), What Should Not Be Forgotten (1947), The Vatican Without Mask (1949) etc.

When the Holy See discovered that Halan planned to publish his new anti-clerical pamphlet The Father of Darkness and His Henchmen, Pope Pius XII excommunicated him in July 1949. In response to this, Halan wrote a pamphlet I Spit on the Pope, that caused a significant resonance within the Church and among believers. In the pamphlet he ironised on the Decree against Communism released by the Vatican on 1 July, in which the Holy See had threatened to excommunicate all members of the Communist parties and active supporters of the Communists:

My only consolation is that I am not alone: together with me, the Pope excommunicated at least three hundred million people, and with them I once again in full voice declare: I spit on the Pope!

— Halan, With Cross or Knife, "I Spit on the Pope!", page 112

Assassination

Halan was assassinated on 24 October 1949 in his home office, which was situated at Hvadiyska street in Lviv. He received eleven blows to the head with an axe. His blood spilled on the manuscript of his new article, Greatness of the Liberated Human, which celebrated the tenth anniversary of the [Soviet annexation of western Ukraine.

The killers – two students of the Lviv Forestry Technical Institute, Ilariy Lukashevych and Mykhailo Stakhur – were accused of orchestrating the assassination at the behest of the OUN's leadership. On the eve of the murder Lukashevych gained the writer's confidence, so the students were let into the house. They came to the apartment under the pretext of being discriminated against at the university and seeking his help. When Lukashevych gave a signal, Stakhur attacked the writer with the axe. After Stakhur was convinced that Halan was dead, they tied up the housekeeper and escaped.

The Ministry of the State Security (MGB) accused the Ukrainian nationalists of his murder, while the OUN claimed that it was a Soviet provocation in order to start a new wave of repressions against locals.

Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the Ukrainian SSR at that time, took personal control of the investigation. In 1951, the MGB agent Bohdan Stashynsky infiltrated into the OUN underground network and managed to find Stakhur, who himself bragged about the assassination of Halan. He was arrested on 10 July, and afterwards fully admitted his responsibility for the crime during the trial. According to Stakhur, he did that because of the writer's critical statements on the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, Ukrainian Insurgent Army and the Vatican.

On 16 October 1951 the military tribunal of the Carpathian Military District sentenced Mykhailo Stakhur to death by hanging. He was executed that day.

Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the role of the UPA in Halan's assassination has increasingly come under scrutiny. Historian David R. Marples has noted that the methods of the assassination were more similar to the prior killing of Leon Trotsky, which was organised by Soviet intelligence, than typical OUN or UPA assassinations; in contrast to the usage of an axe by Halan's killers, the OUN usually conducted its killings with firearms. Petro Duzhyi, a soldier of the UPA, claimed in a 1993 interview with historian Mykola Oleksyuk that Timofei Strokach expressed a desire to have Halan killed; according to Duzhyi, Strokach had said during an interrogation that Halan's support for arresting the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church's leadership had sparked a popular uprising. Ukrainian literary historian Yuliia Kysla also describes the assassination as a false-flag operation, referring to Lukashevych and Stakhur as being part of one of many groups which were supposedly part of the UPA, but were actually under the control of the Soviet government. Vasyl Kuk, the leader of the UPA, would continue to claim that the assassination had been organised by the MGB in interviews after the Soviet Union's dissolution.

The possibility that he was assassinated by the OUN or UPA, however, has not been conclusively ruled out. Dmitry Vedeneyev and Sergei Shevchenko, writers for the Ukrainian newspaper 2000, compared Halan to Salman Rushdie in 2002 in reference to the latter's Satanic Verses controversy and noted that Halan's criticism of the Catholic Church made him extremely unpopular in deeply-religious Galicia. Marples also notes that there are several problems with most accounts of Halan's assassination and the aftermath, arguing that it is effectively impossible to determine who was responsible for his assassination given that he was equally loathed by both the Soviet government and the UPA at the time of his death.

The assassination of Halan resulted in increased repression of the UPA, which continued its insurgency against the Soviet government. All the leadership of the MGB arrived in Lviv, Pavel Sudoplatov himself worked there for several months. One of the consequences of the murder of Halan was the elimination of the UPA leader Roman Shukhevych four months later.

Evaluations by contemporaries

| This section is a candidate for copying over to Wikiquote using the Transwiki process. |