| Revision as of 20:11, 27 January 2007 editClassicjupiter2 (talk | contribs)1,178 edits and peace be with you!← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:31, 27 January 2007 edit undoTheEvilPanda (talk | contribs)97 edits →SURREALIST ART and RESOURCESNext edit → | ||

| Line 249: | Line 249: | ||

| * , "recomposed photographs", in a rather surrealist spirit. | * , "recomposed photographs", in a rather surrealist spirit. | ||

| * , an article from Arsenal/ Surrealist Subversion | * , an article from Arsenal/ Surrealist Subversion | ||

| ==SURREALIST ART and RESOURCES== | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

Revision as of 20:31, 27 January 2007

| Part of a series on |

| Surrealism |

|---|

| Aspects |

| Groups |

Surrealism is a movement stating that the liberation of our mind, and subsequently the liberation of the individual self and society, can be achieved by exercising the imaginative faculties of the "unconscious mind" to the attainment of a dream-like state different from, or ultimately ‘truer’ than, everyday reality.

Surrealists believe that this more truthful reality can bring about personal, cultural, and social revolution, and a life of freedom, poetry, and uninhibited sexuality. André Breton said that such a revealed truth would be beautific, or in his own words, "beauty will be convulsive or not at all."

In more mundane terms, the word "surreal" is often used colloquially to describe unexpected juxtapositions or use of non-sequiturs in art or dialogue. When the concept of surrealism has been "applied" by associated groups of individuals, it has often been called a "surrealist movement," whether cultural (including artistic) or social.

Surrealist thought

Surrealist thought emerged around 1920, partly as an outgrowth of Dada, with French writer André Breton as its initial principal theorist.

In Breton's Surrealist Manifesto of 1924 he defines Surrealism as:

Dictionary: Surrealism, n. Pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought. Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation.

Encyclopedia: Surrealism. Philosophy. Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin once and for all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principal problems of life. Breton would later qualify the first of these definitions by saying "in the absence of conscious moral or aesthetic self-censorship," and by his admission, through subsequent developments, that these definitions were capable of considerable expansion.

Like those involved in Dada, adherents of Surrealism thought that the horrors of World War I were the culmination of the Industrial Revolution and the result of rational thinking. Consequently, irrational thought and dream-states were seen as the natural antidote to those social problems.

While Dada rejected categories and labels and was rooted in negative response to the First World War, Surrealism advocates the idea that ordinary and depictive expressions are vital and important, but that the sense of their arrangement must be open to the full range of imagination according to the Hegelian Dialectic. The Marxist dialectic and other theories, such as Freudian theory, also played a significant role in some of the development of surrealist theory and, as in the work of such theorists as Walter Benjamin and Herbert Marcuse, surrealism contributed to the development of Marxian theory itself.

The Surrealist diagnosis of the "problem" of the realism and capitalist civilization is a restrictive overlay of false rationality, including social and academic convention, on the free functioning of the instinctual urges of them human mind.

Surrealist philosophy connects with the theories of psychiatrist Sigmund Freud. Freud asserted that unconscious thoughts (the thoughts of which one is not aware) motivate human behaviour, and he advocated free association and dream analysis to reveal unconscious thoughts.

It is through the practice of automatism, dream interpretation, and numerous other surrealist methods that Surrealists believe the wellspring of imagination and creativity can be accessed.

Surrealism also embraces idiosyncrasy, while rejecting the idea of an underlying madness or darkness of the mind. Salvador Dalí, who is considered to have been quite idiosyncratic, explained it as the following: "The only difference between myself and a madman is I am not MAD!"

Surrealists look to so-called "primitive art" as an example of expression that is not self-censored.

The radical aim of Surrealism is to revolutionize human experience, including its personal, cultural, social, and political aspects, by freeing people from what is seen as false rationality, and restrictive customs and structures. As Breton proclaimed, the true aim of Surrealism is "long live the social revolution, and it alone!"

To this goal, at various times Surrealists have aligned with communism and anarchism.

Not all Surrealists subscribe to all facets of the philosophy. Historically many were not interested in political matters, and this lack of interest created rifts in the Surrealism movement.

- See also History of surrealism

Surrealism in politics

Surrealism as a political force developed unevenly around the world, in some places more emphasis was on artistic practices, in other places political and in other places still, surrealist praxis looked to supersize both art and politics.

Politically Surrealism was ultra-leftist, communist or anarchist. The split from Dada has been characterised as a split between anarchists and communists, with the Surrealists as communist. Breton and his comrades supported Trotsky and his International Left Opposition for a while, though there was a certain openness to anarchism that manifested more fully after World War II. Some surrealists such as Benjamin Peret aligned with forms of left communism. Dali supported capitalism and the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco but cannot be said to represent a trend in surrealism in this respect; in fact he was considered to have betrayed and left Surrealism by Breton and his associates.

Surrealists have often sought to link their efforts with political ideals and activities. In the 'Declaration of January 27, 1925' for example, members of the Paris-based Bureau of Surrealist Research (including André Breton, Louis Aragon, and, Antonin Artaud, as well as some two dozen others) declared their affinity for revolutionary politics. While this was initially a somewhat vague formulation, by the 1930s many Surrealists had strongly identified themselves with communism. The foremost document of this tendency within Surrealism is the "Manifesto for a Free Revolutionary Art" published under the names of Breton and Diego Rivera but actually co-authored by Breton and Leon Trotsky. Dada Turns Red, Helena Lewis' history of the uneasy relations between Surrealists and Communists from the 1920s through the 1950s was published in 1990 by the University of Edinburgh Press.

Black surrealism and Negritude

In 1925, the Paris Surrealist Group and the extreme left of the French Communist Party came together to support Abd-el-Krim, leader of the Rif uprising against French colonialism in Morocco. In an Open Letter to writer and French ambassador to Japan, Paul Claudel, the Paris group announced:

"We Surrealists pronounced ourselves in favour of changing the imperialist war, in its chronic and colonial form, into a civil war. Thus we placed our energies at the disposal of the revolution, of the proletariat and its struggles, and defined our attitude towards the colonial problem, and hence towards the colour question."

The anticolonial revolutionary and proletarian politics of "Murderous Humanitarianism" (1932) which was drafted mainly by Rene Crevel, signed by André Breton, Paul Eluard, Benjamin Peret, Yves Tanguy, and the Martiniquan surrealists Pierre Yoyotte and J.M. Monnerot perhaps makes it the original document of what is later called 'black surrealism' (A Poetics of Anticolonialism, Nov, 1999 by Robin D.G. Kelley), although it is the contact between Aimé Césaire and Breton in the 1940s in Martinique that really lead to the communication of what is known as 'Black Surrealism'.

Anticolonial revolutionary writers of Martinique, a French colony at the time, took up Surrealism as a revolutionary method - a critique of European culture and a radical subjective. This linked up with other Surrealists and was very important for the subsequent development of Surrealism as a revolutionary praxis. The journal Tropiques, featuring the work of Cesaire along with René Ménil, Lucie Thésée, Aristide Maugée and others, was first published in 1940.

Post Situationist Surrealism

In the 1960s, while the Situationist leadership - especially Guy Debord was critical and distanced himself from Surrealism, others such as Asger Jorn were explicitly using surrealist techniques and methods. The attitude of some Surrealists to the Situationists was similarly diverse, but common ground is wekll documented, eg by the Chicago Surrealist Group, Heatwave andf the IWW. The 1968 General strike and student revolt in France which was influenced by the Paris based Situationist International included a number of surrealist ideas, and among the slogans the students spray-painted on the walls of the Sorbonne were familiar surrealist ones. Joan Miró would commemorate this in a painting entitled May 1968.

During the 1980s, behind the Iron Curtain, Surrealism entered into politics, and this thanks to an underground artistic opposition movement known as the Orange Alternative. The Orange Alternative was created in 1981 by Waldemar Fydrych alias 'Major', a graduate of history and art history at the University of Wrocław, who used surrealism symbolism and terminology in its large scale happenings organized in the major Polish cities during the Jaruzelski regime and painted surrealist graffiti on spots covering up anti-regime slogans. Major himself was the author of the so-called "Manifest of Socialist Surrealism". In this Manifest, he stated that the socialist (communist) system had become so surrealistic that it could be seen as an expression of art itself.

Surrealism in the arts and media

- See Surrealism in the Arts for more information

In general usage, the term Surrealism is more often considered a movement in visual arts than the original cultural and philosophical movement. As with some other movements that had both philosophical and artistic dimensions, such as romanticism and the relationship between the two usages is complex and a matter of some debate outside the movement. Many Surrealist artists regarded their work as an expression of the philosophical movement first and foremost, and Breton was explicit in his belief that Surrealism was above all a revolutionary movement.

Early visual arts Surrealism

Since many of the initial participants in Surrealism originated in the Dada movement, a strict demarcation of Surrealist and Dadaist theory and practice can be difficult to draw, although André Breton's statements on the matter leave no doubt of his own clarity on that boundary. Outside the "inner circle" (i.e. in the Academy), this imaginary line is sketched differently by different scholars.

The roots of Surrealism in the visual arts run to both Dada and Cubism, as well as the abstraction of Wassily Kandinsky and Expressionism, as well as Post-Impressionism, and also partake of older "bloodlines" such as Hieronymus Bosch, and so-called "primitive" and "naive" arts. This only makes sense if one considers Surrealism to be a matter of art, when both Dadaists and Surrealists themselves rejected the notion without hesitation. Dada - especially - declared loudly and often that it was out to destroy art, and Surrealism - although less brutish in its campaign against art-in-itself, made clear its resistance to any idea that it was - in fact - an "art movement" at all. Technique was beside the point, mere ornament or simple retinal stimulation was anathema, as the Surrealists claimed visual arts as a subsidiary of Poetry, and hoped to inflame human desires directly via their images. The fact that the first Surrealists were not visual artists but poets speaks volumes about the poetic and philosophical basis of Surrealism. The truth is, André Breton initially had doubts that visual arts could even be useful in the Surrealist movement, since they appeared to be less "malleable" and open to chance and automatism. This "caution" was overcome by the discovery of such "techniques" as frottage, decalcomania, and Dali's own paranoid-critical methods. As the idea of automatism lost sway as the main vehicle for unlocking the unconscious, the visual arts (including sculpture, painting, and film) became more acceptable.

Masson's automatic drawings of 1923, are often used as a convenient point of difference, since these reflect the influence of the idea of the unconscious mind.

Another example is Alberto Giacometti's 1925 Torso, which marked his movement to simplified forms and inspiration from pre-classical sculpture. However, a striking example of the line used to divide Dada and Surrealism among art experts is the pairing of 1925's Von minimax dadamax selbst konstruiertes maschinchen with Le Baiser from 1927 by Max Ernst. The first is generally held to have a distance, and erotic subtext, where as the second presents an erotic act openly and directly. In the second the influence of Miró and Picasso's drawing style is visible with the use of fluid curving and intersecting lines and colour, where as the first takes a directness that would later be influential in movements such as Pop art.

Giorgio de Chirico was one of the important joining figures between the philosophical and visual aspects of Surrealism. Between 1911 and 1917, he adopted an unornamented depictional style whose surface would be adopted by others later. La tour rouge from 1913 shows the stark colour contrasts and illustrative style later adopted by Surrealist painters. His 1914 La Nostalgie du poete has the figure turned away from the viewer, and the juxtaposition of a bust with glasses and a fish as a relief defies conventional explanation. He was also a writer. His novel Hebdomeros presents a series of dreamscapes, with an unusual use of punctuation, syntax and grammar, designed to create a particular atmosphere and frame around its images. His images, including set designs for the Ballet Russe, would create a decorative form of visual Surrealism, and he would be an influence on the two that would be even more closely associated with Surrealism in the public mind: Dalí and Magritte.

In 1924, Miro and Masson applied Surrealism theory to painting explicitly leading to the La Peinture Surrealiste Exposition at Gallerie Pierre in 1925, which included work by Man Ray, Masson, Klee and Miró among others. It confirmed that Surrealism had a component in the visual arts (though it had been initially debated whether this was possible), techniques from Dada, such as photomontage were used.

Galerie Surréaliste opened on March 26, 1926 with an exhibition by Man Ray.

Breton published Surrealism and Painting in 1928 which summarized the movement to that point, though he continued to update the work until the 1960s.

1930s

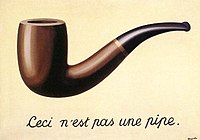

Dalí and Magritte created the most widely recognized images of the movement. Dalí joined the group in 1929, and participated in the rapid establishment of the visual style between 1930 and 1935.

Surrealism as a visual movement had found a method: to expose psychological truth by stripping ordinary objects of their normal significance, in order to create a compelling image that was beyond ordinary formal organization, in order to evoke empathy from the viewer.

1931 marked a year when several Surrealist painters produced works which marked turning points in their stylistic evolution: Magritte's La Voix des airs is an example of this process, where three large spheres representing bells hanging above a landscape. Another Surrealist landscape from this same year is Tanguy's Palais promontoire, with its molten forms and liquid shapes. Liquid shapes became the trademark of Dalí, particularly in his The Persistence of Memory, which features the image of watches that sag as if they are melting.

The characteristics of this style: a combination of the depictive, the abstract, and the psychological, came to stand for the alienation which many people felt in the modern period, combined with the sense of reaching more deeply into the psyche, to be "made whole with ones individuality".

Long after personal, political and professional tensions broke the Surrealist group up, Magritte and Dalí continued to define a visual program in the arts. This program reached beyond painting, to encompass photography as well, as can be seen from a Man Ray self portrait, whose use of assemblage influenced Robert Rauschenberg's collage boxes.

During the 1930s Peggy Guggenheim, an important art collector married Max Ernst and began promoting work by other Surrealists such as Yves Tanguy and the British artist John Tunnard. However, by the outbreak of the Second World War, the taste of the avant-garde swung decisively towards Abstract Expressionism with the support of key taste makers, including Guggenheim. However, it should not be easily forgotten that Abstract Expressionism itself grew directly out of the meeting of American (particularly New York) artists with European Surrealists self-exiled during WWII. In particular, Arshile Gorky influenced the development of this American art form, which — as Surrealism did — celebrated the instantaneous human act as the well-spring of creativity. The early work of many Abstract Expressionists reveals a tight bond between the more superficial aspects of both movements, and the emergence (at a later date) of aspects of Dadaistic humor in such artists as Rauschenberg sheds an even starker light upon the connection. Up until the emergence of Pop Art, Surrealism can be seen to have been the single most important influence on the sudden growth in American arts, and even in Pop, some of the humor manifested in Surrealism can be found, often turned to a cultural criticism.

World War II and beyond

The coming of the Second World War proved disruptive for surrealism. The works continued. Many Surrealist artists continued to explore their vocabularies, including Magritte. Many members of the Surrealist movement continued to correspond and meet. (In 1960, Magritte, Duchamp, Ernst, and Man Ray met in Paris.) While Dalí may have been excommunicated by Breton, he neither abandoned his themes from the 1930s, including references to the "persistence of time" in a later painting, nor did he become a depictive "pompier". His classic period did not represent so sharp a break with the past as some descriptions of his work might portray, and some, such as Thirion, argued that there were works of his after this period that continued to have some relevance for the movement.

During the 1940s Surrealism's influence was also felt in England and America. Mark Rothko took an interest in biomorphic figures, and in England Henry Moore, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon and Paul Nash used or experimented with Surrealist techniques. However, Conroy Maddox, one of the first British Surrealists, whose work in this genre dated from 1935, remained within the movement, organizing an exhibition of current Surrealist work in 1978, in response to an earlier show which infuriated him because it did not properly represent Surrealism. Maddox's exhibition, titled Surrealism Unlimited, was held in Paris, and attracted international attention. He held his last one-man show in 2002, dying three years later.

Magritte's work became more realistic in its depiction of actual objects, while maintaining the element of juxtaposition, such as in 1951's Personal Values and 1954's Empire of Light. Magritte continued to produce works which have entered artistic vocabulary, such as Castle in the Pyrenees, which refers back to Voix from 1931, in its suspension over a landscape.

Other figures from the Surrealist movement were expelled. Several of these artists, like Roberto Matta (by his own description) "remained close to Surrealism."

Many new artists explicitly took up the Surrealist banner for themselves. Duchamp continued to produce sculpture and, at his death, was working on an installation with the realistic depiction of a woman viewable only through a peephole. Dorothea Tanning and Louise Bourgeois continued to work, for example, with Tanning's Rainy Day Canape from 1970.

During the 1950's a group in Austria called the Fantastic Realists founded by Ernst Fuchs developed out of surrealism into a visionary approach to the arts.

Since the 1960's the Chicago Surrealist Group has been active and has produced a prolific range of work including the international anthology series Arsenal/Surrealist Subversion. Other groups are active today in many cities such as Sao Paulo, London, Paris, Prague, and Buenos Aires.

Surrealistic art remains enormously popular with museum patrons. In 2001 Tate Modern held an exhibition of Surrealist art that attracted over 170,000 visitors in its run. Having been one of the most important of movements in the Modern period, Surrealism proceeded to inspire a new generation seeking to expand the vocabulary of art.

Surrealism in literature & as a school of poetry

The first surrealist work, according to Breton, was Les Champs Magnétiques (1921 “Magnetic Fields”), which was actually a collaboration with the French poet and novelist Philippe Soupault. But even before that, in 1919, Breton, Soupault and Aragon had already published the magazine Littérature, which contained automatist works and accounts of dreams. The magazine and the portfolio both showed their disdain for literal meanings given to objects and focused rather on the undertones, the poetic undercurrents present. Not only did they give emphasis to the poetic undercurrents, but also to the connotations and the overtones which “exist in ambiguous relationships to the visual images.”

Because surrealist writers seldom (if ever) appear to organize their thoughts and the images they present, some people find much of their work difficult to "parse". This notion however is a superficial comprehension, prompted no doubt by Breton's initial emphasis on automatic writing as the main route toward a higher reality. But — as in Breton's case itself — much of what is presented as purely automatic is actually edited and very "thought out". Breton himself later admitted that automatic writing's centrality had been overstated, and other elements were introduced, especially as the growing involvement of visual artists in the movement forced the issue, since "automatic painting" required a rather more strenuous set of approaches. Thus such elements as collage were introduced, arising partly from an ideal of startling juxtapositions as revealed in Pierre Reverdy's poetry. And — as in Magritte's case (where there is no obvious recourse to either automatic techniques or collage) the very notion of convulsive joining became a tool for revelation in and of itself. Surrealism was meant to be always in flux — to be more modern than modern — and so it was natural there should be a rapid shuffling of the philosophy as new challenges arose.

Surrealists revived interest in Isidore Ducasse, known by his pseudonym “Le Comte de Lautréamont” and for the line “beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella”, and Arthur Rimbaud, two late 19th century writers believed to be the precursors of Surrealism.

Examples of surrealist literature are René Crevel's Mr. Knife Miss Fork, Louis Aragon's Irene's Cunt, André Breton's Sur la route de San Romano, Benjamin Peret's Death to the Pigs, and Antonin Artaud's Le Pese-Nerfs.

Surrealism in music

- Main article: Surrealism (music).

In the 1920s several composers were influenced by Surrealism, or by individuals in the Surrealist movement. Among these were Bohuslav Martinů, André Souris, and Edgard Varèse, who stated that his work Arcana was drawn from a dream sequence. Souris in particular was associated with the movement: he had a long, if sometimes spotty, relationship with Magritte, and worked on Paul Nouge's publication Adieu Marie.

French composer Pierre Boulez wrote a piece called explosante-fixe (1972), inspired by Breton's mad love.

Germaine Tailleferre of the French group Les Six wrote several works which could be considered to be inspired by Surrealism, including the 1948 Ballet "Paris-Magie" (scenario by Lise Deharme, who was closely linked to Breton), the Operas "La Petite Sirène" (book by Philippe Soupault) and "Le Maître" (book by Eugène Ionesco). Tailleferre also wrote popular songs to texts by Claude Marci, the wife of Henri Jeanson, whose portrait had been painted by Magritte in the 1930s.

Even though Breton by 1946 responded rather negatively to the subject of music with his essay Silence is Golden, later Surrealists have been interested in—and found parallels to—Surrealism in the improvisation of jazz (as alluded to above), and the blues (Surrealists such as Paul Garon have written articles and full-length books on the subject). Jazz and blues musicians have occasionally reciprocated this interest. For example, the 1976 World Surrealist Exhibition included such performances by Honeyboy Edwards.

More modern surrealists have found inspiration in genres as diverse as reggae and, later, electronic/noise music such as Merzbow, rap and some rock/pop bands such as The Psychedelic Furs. Both surrealism and, to a lesser extent, dada, experienced a new vogue though association with the psychedelic rock scene of the 1960s and has been cited as influence by artists such as Hal Rammel, David Bowie, Brian Eno, Rozz Williams and Mark Murex (who has described his work and that of others as "psychoxenic surrealism" or "xenotrance"). Direct references to surrealism in album titles include Surrealistic Pillow by Jefferson Airplane in 1967 and Chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and umbrella (a line in Lautreamont's Maldoror) by Nurse with Wound. Surrealism is also prevalent in the work of progressive rock band Pink Floyd particularly in their concept album The Wall which incorperated surrealistic illustrations (on its album sleeves) and surreal story and lyrics by leader Roger Waters.

Surrealism in film

Surrealist films include Un chien andalou and L'Âge d'or by Luis Buñuel and Dalí; Buñuel went on to direct many more, with varying degrees of surrealism. Notable for their surrealist elements amongst Bunuel's later films are Le Charme discret de la bourgeoisie, El Ángel exterminador, and Belle de jour.

Films by the surrealist movement:

- Entr'acte by René Clair (1924)

- La Coquille et le clergyman by Germaine Dulac, screenplay by Antonin Artaud (1927)

- Un chien andalou by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí (1928)

- L'Étoile de mer by Man Ray (1928)

- L'Âge d'or by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí (1930)

- Le Sang d'un poète by Jean Cocteau (1930)

Later directors who made surrealistic films:

- Michel Gondry (La Science des rêves)

- Jean-Pierre Jeunet (Delicatessen, La Cité des enfants perdus)

- Alejandro Jodorowsky (El Topo, The Holy Mountain)

- David Lynch (Eraserhead, Mulholland Drive)

- Guy Maddin ("Archangel", "The Saddest Music in the World")

- Takashi Miike (Gozu)

- Mamoru Oshii (Tenshi no Tamago)

- The Brothers Quay (The Piano Tuner of Earthquakes)

- Jacques Rivette (Céline et Julie vont en bateau)

- Jan Svankmajer (Faust, Alice)

- Shinya Tsukamoto (Tetsuo, Rokugatsu no Hebi)

Marcel Mariën (L'imitation du cinéma), André Delvaux (Un Soir, un train) and, more recently, Jan Bucquoy (Camping Cosmos) are notable for being representational of the Belgian surrealist school in cinema. Antonin Artaud, Philippe Soupault and Robert Desnos wrote screenplays for surrealistic films. Salvador Dali designed a dream sequence for Alfred Hitchcock's film Spellbound. There is a strong surrealist influence present in Alain Resnais's Last Year at Marienbad. Surrealist and film theorist Robert Benayoun has written books on Tex Avery, Woody Allen, Buster Keaton and the Marx Brothers.

The truest aspects of Surrealism in film are often found in passing frames of a larger film; the sudden emergence of the uncanny into the "normal" which may or may not be further explored in the rest of the film. The original group spent hours going from film to film, often not finishing one before seeking another, partly in hopes of catching just such ephemeral moments, and partly with the idea of "stitching together" a film in their own minds out of the disparate parts.

Surrealism in television

Surrealism on television has come mainly in the form of comedy (see below), but a few examples serious uses of surreal imagery can be found in The Prisoner, Æon Flux, Twin Peaks, Northern Exposure and even The Sopranos.

Tex Avery cartoons originated on film in the 1930s and 1940s, but millions more know his famous characters from Saturday morning cartoons replayed during the 1970s: Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, etc.

Another Looney Tunes animator, Robert Clampett, was renown for his surrealistic style in both story and visuals. Especially notable are The Great Piggy Bank Robbery and Porky in Wackyland.

Surrealism in comedy

- Main article: Surreal humour.

Some branches of comedy (chiefly British, and also Japanese) are known for being very surreal. Some notable examples include:

- Q

- The Goon Show

- Monty Python

- The Goodies

- The Young Ones

- Reeves and Mortimer

- The Firesign Theatre

- FLCL

- Father Ted

- Smack the Pony

- Green Wing

- Azumanga Daioh

- Vermilion Pleasure Night

- The Mighty Boosh

- 12 oz. Mouse

Impact of Surrealism

While Surrealism is typically associated with the arts, it has been said to transcend them; Surrealism has had an impact in many other fields. In this sense, Surrealism does not specifically refer only to self-identified "Surrealists", or those sanctioned by Breton, rather, it refers to a range of creative acts of revolt and efforts to liberate imagination.

In addition to Surrealist ideas that are grounded in the ideas of Hegel, Marx and Freud, surrealism is seen by its advocates as being inherently dynamic and as dialectic in its thought. Surrealists have also drawn on sources as seemingly diverse as Clark Ashton Smith, Montague Summers, Horace Walpole, Fantomas, The Residents, Bugs Bunny, comic strips, the obscure poet Samuel Greenberg and the hobo writer and humourist T-Bone Slim. One might say that Surrealist strands may be found in movements such as Free Jazz (Don Cherry, Sun Ra, Cecil Taylor etc.) and even in the daily lives of people in confrontation with limiting social conditions. Thought of as the effort of humanity to liberate imagination as an act of insurrection against society, surrealism finds precedents in the alchemists, possibly Dante, Hieronymus Bosch, Marquis de Sade, Charles Fourier, Comte de Lautreamont and Arthur Rimbaud.

Surrealists believe that non-Western cultures also provide a continued source of inspiration for Surrealist activity because some may strike up a better balance between instrumental reason and the imagination in flight than Western culture. Surrealism has had an identifiable impact on radical and revolutionary politics, both directly -- as in some surrealists joining or allying themselves with radical political groups, movements and parties -- and indirectly -- through the way in which surrealists' emphasis on the intimate link between freeing the imagination and the mind and liberation from repressive and archaic social structures. This was especially visible in the New Left of the 1960s and 1970s and the French revolt of May 1968, whose slogan "All power to the imagination" arose directly from French surrealist thought and practice.

Some artists, such as H.R. Giger in Europe, who won an Academy Award for his stage set, and who also designed the "creature," in the movie Alien, have been popularly called "Surrealists," though Giger's art is promoted as surrealist biomorphic art.

Critiques of Surrealism

Surrealism has been critiqued from several perspectives:

Feminist

Feminists have in the past critiqued the surrealist movement, claiming that it is fundamentally a male movement and a male fellowship, despite the occasional few celebrated woman surrealist painters and poets. They believe that it adopts typical male attitudes toward women, such as worshipping them symbolically through stereotypes and sexist norms. Some feminists have argued that in surrealism women are often made to represent higher values and transformed into objects of desire and of mystery.

Freudian

Freud initiated the psychoanalytic critique of surrealism with his remark that what interested him most about the surrealists was not their unconscious but their conscious. His meaning was that the manifestations of and experiments with psychic automatism highlighted by surrealists as the liberation of the unconscious were highly structured by ego activity, similar to the activities of the dream censorship in dreams, and that therefore it was in principle a mistake to regard surrealist poems and other art works as direct manifestations of the unconscious, when they were indeed highly shaped and processed by the ego. In this view, the surrealists may have been producing great works, but they were products of the conscious, not the unconscious mind, and they deceived themselves with regard to what they were doing with the unconscious. In psychoanalysis proper, the unconscious does not just express itself automatically but can only be uncovered through the analysis of resistance and transference in the psychoanalytic process.

Situationist

While some individuals and groups on the core and fringes of the Situationist International were surrealists themselves, others were very critical of the movement, or indeed what remained of the movement in the late 50s and 60s. The Situationist International could therefore be seen as a break and continuiation of the Surrealist praxis. The Situationists felt that surrealism had retreated into the salons and galleries and therefore had been absorbed into the bourgeois order. They nevertheless took inspiration from some surrealist theories and methods.

References

- A term coined by Guillaume Apollinaire in 1917, see History of surrealism for more details

- Robin DG Kelley, "Poetry and the Political Imagination: Aimé Césaire, Negritude, & the Applications of Surrealism"(July 2001)

See Also

External links

Academic resources/'Classical' Surrealism:

- Manifesto of Surrealism by André Breton. 1924.

- What is Surrealism? Lecture by Breton, Brussels 1934

- Museum for Surrealism in Germany

- Surrealist.com, A general history of the art movement with 100+ artist bio's and art.

- The radical politics of Surrealism, 1919-1950 — an article looking at Surrealism and Surrealists' connections to anarchist, socialist and working class politics

- Franz Kafka and Marcel Proust, the 2 Albums, "recomposed photographs", in a rather surrealist spirit.

- Herbert Marcuse and the Surrealist Revolution, an article from Arsenal/ Surrealist Subversion

| Premodern, Modern and Contemporary art movements | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| List of art movements/periods | |||||||||||||||||

| Premodern (Western) |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Modern (1863–1944) |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Contemporary and Postmodern (1945–present) |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Related topics |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Schools of poetry | |

|---|---|

| |