| Revision as of 15:32, 8 August 2021 editLa lopi (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users5,004 edits →References← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:14, 11 November 2021 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,435,997 edits Alter: title, url, isbn. URLs might have been anonymized. Add: isbn. Upgrade ISBN10 to ISBN13. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Whoop whoop pull up | #UCB_webform 1835/2049Next edit → | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

| Likewise, the influential ] ], although a supporter of the ], nonetheless advocated merging the ] with Croatia. | Likewise, the influential ] ], although a supporter of the ], nonetheless advocated merging the ] with Croatia. | ||

| The concept of a Greater Croatia was developed further<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804–1920|last=Charles Jelavich, Barbara Jelavich|publisher=University of Washington Press|year=2012|isbn=9780295803609|pages=252}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=The Balkans: A Post-Communist History|last=Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries|publisher=Routledge|year=2007|isbn=9781134583287|pages=187}}</ref> by ] and ], who founded the nationalist ] (HSP) in 1861. Unlike Strossmayer and the proponents of the Illyrian movement, HSP advocated a united Croatia that stood independently of a Pan-Slavic umbrella state.<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://books.openedition.org/ceup/2420?lang=es|title=Chapter 2. |

The concept of a Greater Croatia was developed further<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804–1920|last=Charles Jelavich, Barbara Jelavich|publisher=University of Washington Press|year=2012|isbn=9780295803609|pages=252}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=The Balkans: A Post-Communist History|last=Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries|publisher=Routledge|year=2007|isbn=9781134583287|pages=187}}</ref> by ] and ], who founded the nationalist ] (HSP) in 1861. Unlike Strossmayer and the proponents of the Illyrian movement, HSP advocated a united Croatia that stood independently of a Pan-Slavic umbrella state.<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://books.openedition.org/ceup/2420?lang=es|title=Chapter 2. "We Were Defending the State": Nationalism, Myth, and Memory in Twentieth-Century Croatia|last=Biondich|first=Mark|date=2006|website=Open Edition Books}}</ref> Starčević was an early opponent of Croatia's unification with Serbs and Slovenes (chiefly the ]); their ideologies gradually gained popularity during the interwar period as tensions grew in the ] between the Croatian and the more influential Serbian political leaders. Ensuing events surrounding the ideology culminated in the World War II conflict between the ] and its opponents including ] Serbs and Communists of all ethnicities (including Croatian). | ||

| ==Cvetković–Maček Agreement== | ==Cvetković–Maček Agreement== | ||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

| The Ustaša, an ultranationalist and ]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/620426/Ustasa|title=Ustasa (Croatian political movement)|publisher=Britannica.com|access-date=2011-12-22}}</ref> movement founded in 1929 supported a Greater Croatia that would extend to the River ] and to the edge of ].<ref name="Meier1999">{{cite book|last=Meier|first=Viktor|title=Yugoslavia: a history of its demise|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=InX1QDEq_O8C|access-date=23 December 2011|date=23 July 1999|publisher=Psychology Press|isbn=978-0-415-18595-0|page=125}}</ref> ], the Ustaše's ] (leader) had been in negotiations with Fascist Italy since 1927. These negotiations included Pavelić supporting Italy's annexation of its claimed territory in ] in exchange for Italy supporting an independent Croatia.<ref name="Fischer2007">{{cite book|editor=Bernd Jürgen Fischer|title=Balkan strongmen: dictators and authoritarian rulers of South Eastern Europe|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qMZaPjrHqYYC|access-date=23 December 2011|date=March 2007|publisher=Purdue University Press|isbn=978-1-55753-455-2|page=210}}</ref> In addition, ] offered Pavelić the right for Croatia to annex all of ]. Pavelić agreed to this exchange. | The Ustaša, an ultranationalist and ]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/620426/Ustasa|title=Ustasa (Croatian political movement)|publisher=Britannica.com|access-date=2011-12-22}}</ref> movement founded in 1929 supported a Greater Croatia that would extend to the River ] and to the edge of ].<ref name="Meier1999">{{cite book|last=Meier|first=Viktor|title=Yugoslavia: a history of its demise|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=InX1QDEq_O8C|access-date=23 December 2011|date=23 July 1999|publisher=Psychology Press|isbn=978-0-415-18595-0|page=125}}</ref> ], the Ustaše's ] (leader) had been in negotiations with Fascist Italy since 1927. These negotiations included Pavelić supporting Italy's annexation of its claimed territory in ] in exchange for Italy supporting an independent Croatia.<ref name="Fischer2007">{{cite book|editor=Bernd Jürgen Fischer|title=Balkan strongmen: dictators and authoritarian rulers of South Eastern Europe|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qMZaPjrHqYYC|access-date=23 December 2011|date=March 2007|publisher=Purdue University Press|isbn=978-1-55753-455-2|page=210}}</ref> In addition, ] offered Pavelić the right for Croatia to annex all of ]. Pavelić agreed to this exchange. | ||

| The ideology of Greater Croatia, that combined ] with ], culminated in the ], ] and the ] carried out by Ustaša.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Lampe |first1=John |last2=Mazower |first2=Mark |title=Ideologies and National Identities |

The ideology of Greater Croatia, that combined ] with ], culminated in the ], ] and the ] carried out by Ustaša.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Lampe |first1=John |last2=Mazower |first2=Mark |title=Ideologies and National Identities|url=https://archive.org/details/ideologiesnation00lamp |url-access=limited |publisher=Central European University Press|isbn=9789639241824|year=2006|page=-109}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Cyprian |first1= Blamires |title=World Fascism: A-K|publisher=ABC-CLIO|isbn=9781576079409|year=2006|page=691}}</ref><ref name="fischer">{{cite book|editor-last=Fischer|editor-first=Bernd J.|editor-link=Bernd Jürgen Fischer|year=2007|title=Balkan Strongmen: Dictators and Authoritarian Rulers of South-Eastern Europe|publisher=Purdue University Press|isbn=978-1-55753-455-2|pages=207–08, 210, 226}}</ref> | ||

| ==Bosnian War== | ==Bosnian War== | ||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

| | year = 2012 | | year = 2012 | ||

| | isbn = 978-1-13985-175-6 | | isbn = 978-1-13985-175-6 | ||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=psYgAwAAQBAJ |

| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=psYgAwAAQBAJ | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| * {{cite book | * {{cite book | ||

| Line 74: | Line 74: | ||

| | year = 1999 | | year = 1999 | ||

| | isbn = 978-1-85065-525-1 | | isbn = 978-1-85065-525-1 | ||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=pSxJdE4MYo4C |

| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=pSxJdE4MYo4C | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| * {{cite book|title=From Ottawa to Sarajevo: Canadian Peacekeepers in the Balkans|first=Dawn M.|last=Hewitt|publisher=Centre for International Relations, Queen's University|location=Kingston, Ontario|year=1998|isbn=978-0-88911-788-4}} | * {{cite book|title=From Ottawa to Sarajevo: Canadian Peacekeepers in the Balkans|first=Dawn M.|last=Hewitt|publisher=Centre for International Relations, Queen's University|location=Kingston, Ontario|year=1998|isbn=978-0-88911-788-4}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last=Malcolm|first=Noel|author-link=Noel Malcolm|title=Povijest Bosne: kratki pregled|trans-title=Bosnia: A Short History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Y8BKAQAACAAJ|year=1995|publisher=Erasmus Gilda}} | * {{cite book|last=Malcolm|first=Noel|author-link=Noel Malcolm|title=Povijest Bosne: kratki pregled|trans-title=Bosnia: A Short History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Y8BKAQAACAAJ|year=1995|publisher=Erasmus Gilda|isbn=9783895470820}} | ||

| *{{cite journal|url=http://hrcak.srce.hr/103326?lang=en|journal=Journal of Contemporary History|publisher=Croatian Institute of History|location=Zagreb, Croatia|title=Expert Opinion: On the War Connections of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (1991–1995)|volume=36|year=2004|first=Davor|last=Marijan|pages=249–289}} | *{{cite journal|url=http://hrcak.srce.hr/103326?lang=en|journal=Journal of Contemporary History|publisher=Croatian Institute of History|location=Zagreb, Croatia|title=Expert Opinion: On the War Connections of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (1991–1995)|volume=36|year=2004|first=Davor|last=Marijan|pages=249–289}} | ||

| *{{cite web|ref={{harvid|Prlic et al. judgement vol.6|2013}}|url=http://www.icty.org/x/cases/prlic/tjug/en/130529-6.pdf|title=Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić, Berislav Pušić – Judgement – Volume 6 of 6|publisher=International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia|date=29 May 2013}} | *{{cite web|ref={{harvid|Prlic et al. judgement vol.6|2013}}|url=http://www.icty.org/x/cases/prlic/tjug/en/130529-6.pdf|title=Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić, Berislav Pušić – Judgement – Volume 6 of 6|publisher=International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia|date=29 May 2013}} | ||

| Line 88: | Line 88: | ||

| | year = 2001 | | year = 2001 | ||

| | isbn = 978-0-300-09125-0 | | isbn = 978-0-300-09125-0 | ||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=sfcpsAoSoewC |

| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=sfcpsAoSoewC | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| * {{cite book|first1=Balázs |last1=Trencsényi|first2=Márton |last2=Zászkaliczky |title=Whose Love of Which Country?: Composite States, National Histories and Patriotic Discourses in Early Modern East Central Europe|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eyRbB0mbSsUC&pg=PA220|access-date=31 August 2013|year=2010|publisher=BRILL|isbn=978-90-04-18262-2}} | * {{cite book|first1=Balázs |last1=Trencsényi|first2=Márton |last2=Zászkaliczky |title=Whose Love of Which Country?: Composite States, National Histories and Patriotic Discourses in Early Modern East Central Europe|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eyRbB0mbSsUC&pg=PA220|access-date=31 August 2013|year=2010|publisher=BRILL|isbn=978-90-04-18262-2}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last=V. A. Fine|first=John Jr.|title=When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans: A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wEF5oN5erE0C|year=2010|publisher=University of Michigan Press|isbn=0-472-02560- |

* {{cite book|last=V. A. Fine|first=John Jr.|title=When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans: A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wEF5oN5erE0C|year=2010|publisher=University of Michigan Press|isbn=978-0-472-02560-2}} | ||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 11:14, 11 November 2021

This article is about a Croatian nationalist ideology. For the Croatian ancient homeland before migrating to the regions presently inhabited by Croatians, see White Croatia.

Greater Croatia (Template:Lang-hr) is a term applied to certain currents within Croatian nationalism. In one sense, it refers to the territorial scope of the Croatian people, emphasising the ethnicity of those Croats living outside Croatia. In the political sense, though, the term refers to an irredentist belief in the equivalence between the territorial scope of the Croatian people and that of the Croatian state.

Background

See also: Illyrian movementThe concept of a Greater Croatian state has its modern origins with the Illyrian movement, a pan-South-Slavist cultural and political campaign with roots in the early modern period, and revived by a group of young Croatian intellectuals during the first half of the 19th century. Although this movement arose in the developing European nationalist context of the time, it particularly arose as a response to the more powerful nationalist stirrings in the then-Kingdom of Hungary, with whom Croatia was in a personal union.

The foundations of the concept of Greater Croatia are laid in late 17th and early 18th century works of Pavao Ritter Vitezović. He was the first ideologist of Croatian nation who proclaimed that all South Slavs are Croats. His works were used to legitimize expansionism of the Habsburg Empire to the east and south by asserting its historical rights to claim Illyria. "Illyria" as Slavic territory projected by Vitezović would eventually incorporate not only most of the Southeastern Europe but also parts of Central Europe such as Hungary. Vitezović defines territory of Croatia which, besides Illyria and all Slavic populated territory, includes all the territory between Adriatic, Black and Baltic seas.

Because the Kingdom of Hungary was so large, Hungary attempted processes of Magyarisation on its constituent territories. As a reaction, Ljudevit Gaj led the creation of the Illyrian movement. This movement aimed to establish Croatian national presence within Austria-Hungary through linguistic and ethnic unity among South Slavs. This was the first and most prominent Pan-Slavic movement in Croatian history.

An early proponent of Croatian-based Pan-Slavism was the politician, Count Janko Drašković. In 1832, he published his Dissertation to the joint Hungarian-Croatian Diet, in which he envisioned a “Great Illyria” consisting of all the South Slav provinces of the Habsburg Empire.

Likewise, the influential Bishop Josip Juraj Strossmayer, although a supporter of the Habsburg Monarchy, nonetheless advocated merging the Kingdom of Dalmatia with Croatia.

The concept of a Greater Croatia was developed further by Ante Starčević and Eugen Kvaternik, who founded the nationalist Party of Rights (HSP) in 1861. Unlike Strossmayer and the proponents of the Illyrian movement, HSP advocated a united Croatia that stood independently of a Pan-Slavic umbrella state. Starčević was an early opponent of Croatia's unification with Serbs and Slovenes (chiefly the Kingdom of Serbia); their ideologies gradually gained popularity during the interwar period as tensions grew in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia between the Croatian and the more influential Serbian political leaders. Ensuing events surrounding the ideology culminated in the World War II conflict between the Independent State of Croatia and its opponents including Chetnik Serbs and Communists of all ethnicities (including Croatian).

Cvetković–Maček Agreement

Amid rising ethnic tensions between Croats and Serbs in the 1930s, an autonomous state within Yugoslavia, called the Banovina of Croatia was peacefully negotiated in the Yugoslav parliament via the Cvetković–Maček Agreement of 1939. Croatia was united into a single territorial unit and was provided territories of parts of present-day Vojvodina, and both Posavina and southern parts of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, which had Croatian majority at the time.

Independent State of Croatia

The first modern development of a Greater Croatia came about with the establishment of the Independent State of Croatia (Template:Lang-hr, NDH). Following occupation of the country by Axis forces in 1941, Slavko Kvaternik, deputy leader of the Ustaše proclaimed the establishment of the NDH.

The Ustaša, an ultranationalist and fascist movement founded in 1929 supported a Greater Croatia that would extend to the River Drina and to the edge of Belgrade. Ante Pavelić, the Ustaše's Poglavnik (leader) had been in negotiations with Fascist Italy since 1927. These negotiations included Pavelić supporting Italy's annexation of its claimed territory in Dalmatia in exchange for Italy supporting an independent Croatia. In addition, Mussolini offered Pavelić the right for Croatia to annex all of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Pavelić agreed to this exchange. The ideology of Greater Croatia, that combined clerical fascism with Nazi-inspired racial theory, culminated in the genocide of Serbs, the Holocaust in NDH and the Porajmos carried out by Ustaša.

Bosnian War

Main articles: Bosnian War, Partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatian Republic of Herzeg-BosniaThe most recent expression of a Greater Croatia arose in the aftermath of the breakup of Yugoslavia. When the multiethnic Yugoslav republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence in 1992, Bosnian Serb political representatives, who had boycotted the referendum, established their own government of Republika Srpska, whereupon their forces attacked the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

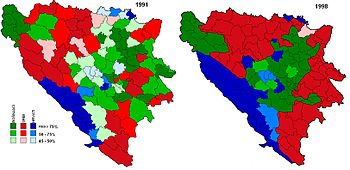

Territorial ethnic changes before and after the Bosnian War

At the beginning of the Bosnian war, the Croats and Bosniaks formed an alliance against the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS). The main Croat army was the Croatian Defence Council (HVO), and the Bosniak was the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH). In November 1991, the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia was established as an autonomous Croat territorial unit within Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The leaders of Herzeg-Bosnia called it a temporary measure during the conflict with the Serb forces and claimed it had no secessionary goal. The Croatian Defence Forces (HOS), a paramilitary wing of the Croatian Party of Rights, supported a confederation between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, but on the basis of the NDH. Over time, the relations between Croats and Bosniaks worsened, resulting in the Croat–Bosniak War, which lasted until early 1994 and the signing of the Washington Agreement.

Croatian President Franjo Tuđman was criticised for trying to expand the borders of Croatia, mostly by annexing Herzegovina and parts of Bosnia with Croat majorities. In 2013, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) ruled, by a majority, that the Croatian leadership had a goal to join the areas of Herzeg-Bosnia to a "Greater Croatia", in accordance with the borders of the Banovina of Croatia in 1939. Judge Jean-Claude Antonetti, the presiding judge in the trial, issued a separate opinion in which he disputed the notion that Tuđman had a plan to divide Bosnia. On 29 November 2017, the Appeals Chamber concluded that Tuđman shared the ultimate purpose of "setting up a Croatian entity that reconstituted earlier borders and that facilitated the reunification of the Croatian people".

Lands of Greater Croatia

Most commonly encompassed regions include:

- Croatia

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bačka region (Serbia)

- Syrmia region (Croatia and Serbia)

- Boka Kotorska region (Montenegro)

- Sandžak

See also

References

- ^ Čanak, Nenad (1993). Ratovi tek dolaze. Nezavisno društvo novinara Vojvodine. p. 12.

- Gow, James (2003). The Serbian Project and Its Adversaries: A Strategy of War Crimes. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 229.

- John B. Allcock; Marko Milivojević; John Joseph Horton (1998). Conflict in the former Yugoslavia: an encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-87436-935-9. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

The concept of Greater Croatia...It has its roots in the writings of Pavao Ritter Vitezovic,...

- Ivo Banac (1988). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8014-9493-2. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

...was the first Croat national ideologist to extend the Croat name to all the Slavs, ...

- Banac, Ivo (1988). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. p. 73. ISBN 0-8014-9493-1.

- V. A. Fine 2010, p. 486.

- Trencsényi & Zászkaliczky 2010, p. 364

By Slavic territories, Vitezović meant the Illyria of his dreams (Greater Croatia) which, in its boldest manifestation, would have incorporated Hungary itself.

- V. A. Fine 2010, p. 487.

- Elinor Murray Despalatović (1975). Ljudevit Gaj and the Illyrian Movement. East European Quarterly. ISBN 978-0-914710-05-9. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ Charles Jelavich, Barbara Jelavich (2012). The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804–1920. University of Washington Press. p. 252. ISBN 9780295803609.

- Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries (2007). The Balkans: A Post-Communist History. Routledge. p. 187. ISBN 9781134583287.

- Biondich, Mark (2006). "Chapter 2. "We Were Defending the State": Nationalism, Myth, and Memory in Twentieth-Century Croatia". Open Edition Books.

- "Ustasa (Croatian political movement)". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- Meier, Viktor (23 July 1999). Yugoslavia: a history of its demise. Psychology Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-415-18595-0. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- Bernd Jürgen Fischer, ed. (March 2007). Balkan strongmen: dictators and authoritarian rulers of South Eastern Europe. Purdue University Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-55753-455-2. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- Lampe, John; Mazower, Mark (2006). Ideologies and National Identities. Central European University Press. p. 54-109. ISBN 9789639241824.

- Cyprian, Blamires (2006). World Fascism: A-K. ABC-CLIO. p. 691. ISBN 9781576079409.

- Fischer, Bernd J., ed. (2007). Balkan Strongmen: Dictators and Authoritarian Rulers of South-Eastern Europe. Purdue University Press. pp. 207–08, 210, 226. ISBN 978-1-55753-455-2.

- Christia 2012, p. 154.

- Marijan 2004, p. 259.

- Malcolm 1995, p. 318.

- Hewitt 1998, p. 71.

- Marijan 2004, p. 270.

- Christia 2012, p. 157-158.

- Tanner 2001, p. 292.

- Goldstein 1999, p. 239.

- Prlic et al. judgement vol.6 2013, p. 383.

- Prlic et al. judgement vol.6 2013, p. 388.

- "Summary of Judgement" (PDF). ICTY. 29 November 2017. p. 10.

- Kolstø, Pål (2016). Strategies of Symbolic Nation-building in South Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 45.

Sources

- Christia, Fotini (2012). Alliance Formation in Civil Wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-13985-175-6.

- Goldstein, Ivo (1999). Croatia: A History. London: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-85065-525-1.

- Hewitt, Dawn M. (1998). From Ottawa to Sarajevo: Canadian Peacekeepers in the Balkans. Kingston, Ontario: Centre for International Relations, Queen's University. ISBN 978-0-88911-788-4.

- Malcolm, Noel (1995). Povijest Bosne: kratki pregled [Bosnia: A Short History]. Erasmus Gilda. ISBN 9783895470820.

- Marijan, Davor (2004). "Expert Opinion: On the War Connections of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (1991–1995)". Journal of Contemporary History. 36. Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History: 249–289.

- "Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić, Berislav Pušić – Judgement – Volume 6 of 6" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 29 May 2013.

- Tanner, Marcus (2001). Croatia: A Nation Forged in War. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09125-0.

- Trencsényi, Balázs; Zászkaliczky, Márton (2010). Whose Love of Which Country?: Composite States, National Histories and Patriotic Discourses in Early Modern East Central Europe. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-18262-2. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- V. A. Fine, John Jr. (2010). When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans: A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-02560-2.

External links

- "Croatia: New Government Alters Position of Diaspora". Transnational Communities Programme. Economic & Social Research Council. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- Janez Kovac (15 February 2000). "Mesic Spurns Greater Croatia". BCR Issue 116. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

| Irredentism | |

|---|---|

| Africa | |

| North America | |

| South America | |

| Western Asia | |

| Southern Asia | |

| Eastern and Southeastern Asia | |

| Central and Eastern Europe | |

| Southern Europe | |

| Italy | |

| Northern Europe | |

| Western Europe | |

| Oceania | |

| Related concepts: Border changes since 1914 · Partitionism · Reunification · Revanchism · Revisionism · Rump state | |