| Revision as of 14:32, 28 January 2007 editVirtualEye (talk | contribs)589 edits Islamic Point of View (added references.)← Previous edit | Revision as of 15:40, 28 January 2007 edit undoStr1977 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers59,126 edits →Criticism of Christianity as derivative: This section repeatedly narrates opinion as factNext edit → | ||

| Line 249: | Line 249: | ||

| == Criticism of Christianity as derivative == | == Criticism of Christianity as derivative == | ||

| {{POV-section}} | |||

| {{seealso|Historicity of Jesus|Jesus as myth}} | {{seealso|Historicity of Jesus|Jesus as myth}} | ||

Revision as of 15:40, 28 January 2007

You must add a |reason= parameter to this Cleanup template – replace it with {{Cleanup|December 2006|reason=<Fill reason here>}}, or remove the Cleanup template.

| The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this article, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new article, as appropriate. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Over the centuries, Christianity has been criticized by philosophers, journalists, members of other religions, scientists, and other people from all walks of life. This article outlines some of the major Criticisms of Christianity and the actions of its followers, that have been offered through the years.

Currently, most criticisms come from conflict between certain modern theories and ideologies and the Christian tradition. These theories and ideologies include the Enlightenment's elevation of reason and distaste for miracle, advances in modern science, historical analysis of the Bible and of early Christian history, modern ethics (especially relativism), multiculturalism, modern political movements (especially socialism), feminism, and the modern understanding of personal privacy and liberty. Others also criticize Christianity because its adherents have adopted practices now widely considered immoral, such as support for slavery, religious persecution, etc.

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Christianity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

||||

| Theology | ||||

|

||||

| Related topics | ||||

Criticism of Christianity as irrational

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Many skeptics consider that all religious faith is essentially irrational, and incompatible with reason. Friedrich Nietzsche defined faith as "not wanting to know what is true." Philosopher and mathematician William Kingdon Clifford argued that it is always wrong to believe something with insufficient evidence. H. L. Mencken described it as "an illogical belief in the occurrence of the improbable."

Schopenhauer criticizes believers for mistakenly trusting those who claim religious authority, rather than thinking for themselves, and for attempting to hold mutually incompatible beliefs derived from religious authority and from rational consideration of the world of science or the senses.

In Is belief in God Rational, Alvin Plantinga argues that religious believers do not believe doctrines in the way that scientists (at least in principle) believe theories—they do not have a readiness to reconsider their belief:

- The mature believer, the mature theist, does not typically accept belief in God tentatively, or hypothetically, or until something better comes along. Nor, I think, does he accept it as a conclusion from other things he believes; he accepts it as basic, as a part of the foundations of his noetic structure. The mature theist commits himself to belief in God: this means that he accepts belief in God as basic.

This committed belief is sometimes called "faith based on zeal". Most philosophers consider that this subordination of reason to emotional commitment is detrimental, as in Plato's Crito, where Socrates states to the naive Crito, "Your zeal is invaluable, if a right one; but if wrong, the greater the zeal the greater the evil." A similar sentiment is expressed by Bertrand Russell, who regards belief in the absence of evidence as harmful.

- Christians hold that their faith does good, but other faiths do harm. At any rate, they hold this about the Communist faith. What I wish to maintain is that all faiths do harm. We may define ‘faith’ as a firm belief in something for which there is no evidence. When there is evidence, no one speaks of ‘faith’. We do not speak of faith that two and two are four or that the earth is round. We only speak of faith when we wish to substitute emotion for evidence.

Other modern skeptics such as Daniel Dennett and Richard Dawkins argue that Christianity has sought to suppress rational enquiry and hence the quest for truth. Dawkins argues that the Bible actively discourages believers from making rational enquiries about their faith, and says that he is against religion "because it teaches us to be satisfied with not understanding the world."

The skeptical view of faith as irrational is effectively supported by some religious believers, who regard reason as entirely irrelevant to their faith, or consider that faiths transcends rationality: Everything is too complicated for men to be able to understand (the book of Ecclesiasticus). Some Christians reject the relevance of reason outright. Christian existentialist philosopher Soren Kierkegaard held that objective knowledge is useful but meaningless, and that only subjective belief has ultimate importance to humans. He promised, "I will not be reciting the multiplication tables on my deathbed." However, most thoughtful Christians see the relation between their Christian faith and reason in a rather different light.

- From the beginning, Christianity has understood itself as the religion of the Logos, as the religion according to reason...In this connection, the Enlightenment is of Christian origin and it is no accident that it was born precisely and exclusively in the realm of the Christian faith....It was and is the merit of the Enlightenment to have again proposed these original values of Christianity and of having given back to reason its own voice...In the so necessary dialogue between secularists and Catholics, we Christians must be very careful to remain faithful to this fundamental line: to live a faith that comes from the Logos, from creative reason, and that, because of this, is also open to all that is truly rational. (Pope Benedict XVI)

Most Christian theologians and Christian philosophers appeal to reason as an important aspect of the Christian faith. These include John Wesley, who included reason in the theological model known as the "Wesleyan Quadrilateral", and C. S. Lewis, who argued that religious belief has rational justification. Recent apologists for Christianity as rational include Tony Campolo, author of the book A Reasonable Faith, and Alister McGrath, who offers a rational critique of Dawkins's arguments for atheism. The will to believe doctrine, originated by psychologist and philosopher William James, holds that the choice to believe without evidence is rational in some cases on pragmatic reasons. Christian philosopher Thomas V. Morris draws a distinction between rationality and evidentialism (the view that all beliefs require evidence), and rejects evidentialism as irrational. Others posit that faith of some kind, even faith in reason itself, is needed to have any beliefs at all, given the potential power of radical skepticism.

Criticism of Christianity as incompatible with science

Main article: Religion and scienceChristianity has sometimes had an antagonistic relationship with science. This arises chiefly because Christian doctrine has presented certain beliefs about the world in terms of the science of the day, and then been unable or unwilling to change its religious perceptions in line with the development of scientific knowledge. This is particularly the case when Christians treat the Bible as infallible in matters of physical fact as well as spiritual or moral truth.

At the 19th century, the perception of an antagonism between the two fields was often very strong.

I do not believe that we are indebted to Christianity for any science. I do not remember that one science is mentioned in the New Testament. There is not one word, so far as I remember, about education -- nothing about any science, nothing about art. The writers of the New Testament seem to have thought that the world was about coming to an end. This world was to be sacrificed absolutely to the next. The affairs of this life were not worth speaking of, all people were exhorted to prepare at once for the other life...The writers who have done most for science have been the most bitterly opposed by the church.

— Robert Ingersoll, A Christmas Sermon

During the nineteenth century developed what scholars today call the conflict thesis (or the warfare model, or the Draper-White thesis). According to it, any interaction between religion and science almost inevitably would lead to open hostility, with religion usually taking the part of the aggressor against new scientific ideas. A popular example was the supposition that people from the Middle Ages believed that the Earth was flat, and that only science, freed from religious dogma, had shown that it was round. This misconception was propagated even by professional historians: in fact, educated people from the Middle Ages already thought that the Earth was spherical.

This notion of a war between science and religion (especially Christianity) remained common in the historiography of science during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For example, according to American religious scholar Kaufmann Kohler (1843–1926), Christian orthodoxy from the 4th century onward:

- ...emphasized faith, produced a thinking that deprecated learning, as was shown by Draper ("History of the Conflict between Science and Religion") and by White ("History of the Warfare of Science with Theology"), a reliance on the miraculous and supernatural, under the from old pagan forms of belief. In the name of the Christian faith reason and research were condemned, Greek philosophy and literature were exterminated, and free thinking was suppressed.

Similar views have also been supported by many scientists. The astronomer Carl Sagan, for example, mentions the dispute between the astronomical systems of Ptolemy (who thought that the sun and planets revolved around the earth) and Copernicus (who thought the earth and planets revolved around the sun). He states in his A personal Voyage that Ptolemy's belief was "supported by the church through the Dark Ages... effectively prevented the advance of astronomy for 1,500 years." Sagan rebukes claims that religion and science did not have an antagonizing relationship in the Medieval era by explaining the axioms of Copernicus' discovery:

- This Copernican model worked at least as well as Ptolemy's crystal spheres, but it annoyed an awful lot of people. The Catholic Church later put Copernicus' work on its list of forbidden books, and Martin Luther described Copernicus in these words...

People give ear to an upstart astrologer who strives to show that the earth revolves, not the heavens or the firmament, the sun or the moon. Whoever wishes to appear clever must devise some new system, which of all systems is of course the very best. This fool wishes to reverse the entire science of astronomy; but sacred Scripture tells us that Joshua commanded the sun to stand still, and not the earth.

— Martin Luther, Tischreden, ed Walsch XXII, 2260

The framing of the relationship between Christianity and science as being predominantly one of conflict is still prevalent in popular culture, but the same is not true among today's academics on the topic. Most of today's historians of science consider that the conflict thesis has been superseded by subsequent historical research, as is expressed by Gary Ferngren in his historical volume Science & Religion:

While some historians had always regarded the Draper-White thesis as oversimplifying and distorting a complex relationship, in the late twentieth century it underwent a more systematic reevaluation. The result is the growing recognition among historians of science that the relationship of religion and science has been much more positive than is sometimes thought. Although popular images of controversy continue to exemplify the supposed hostility of Christianity to new scientific theories, studies have shown that Christianity has often nurtured and encouraged scientific endeavour, while at other times the two have co-existed without either tension or attempts at harmonization. If Galileo and the Scopes trial come to mind as examples of conflict, they were the exceptions rather than the rule.

The new historical research indicates that Christianity may have a much more complex and close relationship with science than most presuppose. Christian organizations figure prominently in the broader histories of many sciences, with many of the scientific minds until the professionalization of scientific enterprise (late 19th century) being clergy and other religious thinkers. (See, for example: List of Christian thinkers in science).

France, early 15th century.

Moreover, many scientists through out history held strong Christian beliefs and strove to reconcile science and religion. Isaac Newton, for example, believed that gravity caused the planets to revolve about the Sun, and credited God with the design. In the concluding General Scholium to the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, he wrote: "This most beautiful System of the Sun, Planets and Comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful being." However, though scientists are often drawn into their field through intrigue of the unknown, in many cases their conception of God and thus religion drastically differs: Einstein believed that "science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind" albeit he maintained that belief in a personal God was for the naive man and Christianity was only of merit due to its moral teachings.

Historians of science such as J.L. Heilbron, Alistair Cameron Crombie, David Lindberg, Edward Grant, Thomas Goldstein, and Ted Davis also have been revising the common notion — the product of black legends say some — that medieval Christianity has had a negative influence in the development of civilization. These historians believe that not only did the monks save and cultivate the remnants of ancient civilization during the barbarian invasions, but the medieval church promoted learning and science through its sponsorship of many universities which, under its leadership, grew rapidly in Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries, (see also: "Medieval science" and "Renaissance of the 12th century"). St. Thomas Aquinas, the Church's "model theologian," not only argued that reason is in harmony with faith, he even recognized that reason can contribute to understanding revelation, and so encouraged intellectual development. He was not unlike other medieval theologians who sought out reason in the effort to defend his faith. Also, some today's scholars, such as Stanley Jaki, have suggested that Christianity with its particular worldview was actually a crucial factor for the emergence of modern science.

Criticism of Christianity as unscientific continues to have force against more conservative forms of Christianity, which have such a high view either of Scriptural or of Church authority that they refuse to accept scientific findings which conflict with their interpretation. One of the most prominent issues has been the Creation-evolution controversy, arising from the rejection of the findings of scientific biology and geology by some Christian groups on religious grounds. However, modernist and liberal forms of Christianity, as well as many of the more conservative approaches, are compatible with the methods and findings of scientific research.

Criticism of Christian ethics

See also: Criticism of the Bible and Ethics in the BibleThe deist Thomas Paine wrote in his Revealed Religion & Morality that "the most detestable wickedness, the most horrid cruelties, and the greatest miseries, that have afflicted the human race, have had their origin in this thing called revelation." Paine argues that the dominance of Christianity was established through violence, "by the sword." Paine supported the French Revolution. Deist persecution of Christians during the Revolution formed a cornerstone of the Reign of Terror. Paine's fellow deist and revolutionary Maximilien Robespierre established the Cult of the Supreme Being as part of his role in the revolutionaries' attempted dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution.

Racial or cultural dominance

From the 16th to the 20th century, some White Christian Europeans oppressed some non-Whites, non-Christians, and non-Europeans in many parts of the world. As was the case with the West's science, philosophy, and politics, some used its religion to aid causes that the majority of modern people, Christian and otherwise, now see as abhorrent. In light of this history, critics have characterized Christianity as promoting slavery, racism, Eurocentrism, and colonialism. Various Christians have responded to these criticisms.

The practice of slavery in the West predates the emergence of Christianity by thousands of years. Early Christianity variously opposed, accepted, or ignored slavery. In early Medieval times, the Church discouraged slavery throughout Europe, because of the practice's association with paganism and Islam at the time. That changed in 1452, when Pope Nicholas V instituted hereditary slavery of captured Muslims and pagans, which effectively meant Africans or Asians. As he read the Bible, God had instructed his faithful to make slaves of the neighboring heathens. Since then, various Christian groups taught that Africans were the descendants of Ham, cursed with "the mark of Ham" (dark skin) to be servants to the descendants of Japheth (Europeans) and Shem (Asians). Some Christians became involved in slavery from the Middle Ages until the abolition movement of the late 19th century met success.

In the 19th century, a schism in the Baptist Convention developed around the issue of abolitionism. Many Baptists in the southern United States supported slavery, and many in the northern states did not. The issue divided Baptists into the two conventions of today. The Southern Baptist Convention has long since abandoned its historical support for slavery. In the 20th century, some Christians in South Africa attempted to justify apartheid on the grounds of their religious beliefs.

Today, only some periphery groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and other Christian hate groups on the racist fringes of the Christian Reconstructionist and Christian Identity movements advocate the reinstitution of slavery. With these exceptions, all Christian faith groups now condemn slavery, and see the practice as incompatible with basic Christian principles.

Rodney Stark makes the argument in For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-Hunts, and the End of Slavery, that Christianity helped to end slavery worldwide, as does Lamin Sanneh in Abolitionists Abroad. These authors point out that Christians who viewed slavery as wrong on the basis of their religious convictions spearheaded abolitionism, and many of the early campaigners for the abolition of slavery were driven by their Christian faith and a desire to realize their view that all people are equal under God. In the late 17th century, anabaptists began to criticize slavery. Criticisms from the Society of Friends, Mennonites, and the Amish followed suit. Prominent among these Christian abolitionists were William Wilberforce, and John Woolman. In Britain and America, Quakers were active in abolitionism. A group of Quakers founded the first English abolitionist organization in 1873, and a Quaker petition brought the issue before government that same year. The Quakers continued to be influential throughout the lifetime of the movement, in many ways leading the way for the campaign. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, was instrumental in starting abolitionism as a popular movement. One author describes the religiosity of abolitionism as follows:

...the campaign to end slavery in the United States was for many years largely the work of a small number of Christians who opposed slavery on explicitly religious grounds and who at the time were regularly condemned as fanatical zealots, bent (as indeed they were) on imposing their religiously based views regarding this particular issue on all those who disagreed.

In addition to aiding abolitionism, many Christians made further efforts toward establishing racial equality, contributing to the Civil Rights Movement. The African American Review notes the important role Christian revivalism in the black church played in the Civil Rights Movement. Martin Luther King, Jr., an ordained Baptist minister, was a leader of the American Civil Rights Movement and president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a Christian Civil Rights organization. King's "I Have a Dream" speech makes reference to his spirituality:

Let freedom ring. And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring — when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children — black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics - will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: "Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!"

Christians have answered the charge of Eurocentrism by pointing out Christianity’s non-European origins. Christianity originated as a sect of Judaism in the Middle East, as Jesus, the founder and central figure of Christianity, lived and held His ministry in the Middle East. The race of Jesus is contested, and various theories have presented His ethnicity as White, Black, Indian, or Jewish. Paul of Tarsus, an ethnic Jew who was born and lived in the Middle East, holds such importance to Christianity that some call him the religion's "Second Founder". The greatest influence on Christianity after Paul, Augustine of Hippo, a Church Father, a Doctor of the Church, and an eminent theologian, was African. These three non-European figures hold unparalleled importance to Christianity.

Others point to the diversity of Christians worldwide to counter criticisms of Eurocentrism. Christianity is a religion open to all Gentiles. that counts one out of every three people on earth among its members. Christendom encompasses a greater area of land than that of any other religious territory. In terms of both population and geography, Christianity is the world's largest religion. As such, Christianity contains a great diversity, and has followers from a wide range of ethnicities, nationalities, and cultures. Both Europeans and non-Hispanic Whites are shrinking minorities in the Church.

In his book Enlarging the Story: Perspectives on Writing World Christian History, Richard Fox Young views the connection between Christianity and Eurocentrism as tenuous, and points to the postcolonial and non-Euopean nature of the emerging Church and its impact on the development of World Christianity. In the postcolonial world, Christianity has lost its association with the West. At the turn of the millennium, 60% of the world’s two billion Christians lived in Africa, Latin America, or Asia, and by 2025, those demographics will shift to an estimated 67% of the world's three billion Christians. The rise of Christianity in the southern hemisphere, especially northern Africa and Latin America, in the late 20th and early 21st centuries is a "grassroots movement" that has generated new forms of Christian theology and worship, and shifted the cultural and geographic focal point of the Church away from the West. The prominence of the southern hemisphere's Christianity has brought with it a cultural and intellectual diversity to World Christianity, and contributed such ideas as Liberation Theology.

Criticism of concern for the weak

Friedrich Nietzsche criticized Christianity as promoting a "slave morality" that opposed the will to power. In The Antichrist, he writes "The poisonous doctrine, 'equal rights for all,' has been propagated as a Christian principle". Adolph Hitler, though by his own account a Christian, despised traditional Christianity, saying "Christianity is a rebellion against natural law, a protest against nature. Taken to its logical extreme, Christianity would mean the systematic cultivation of the human failure." His praise for Jesus identified him as a fighter against the Jews. Anton LeVay wrote in The Satanic Bible that attempting to love all people, as Jesus taught, is impossible and destructive. Oriana Fallaci criticizes Christianity for propagating the love for the enemy, stating that it would strengthen Evil.

Criticism of Christianity as intolerant

| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Claims that Christianity is the one true religion have led Christians to fight wars to enforce their belief in an "unwilling, heathen world". Critics have also noted the prevalence of warfare in the Bible, particularly the Old Testament. Linguist and political writer Noam Chomsky has argued that the Bible is one of the most genocidal books in history.

After the establishment of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire under emperor Theodosius I, the state acted to persecute rival beliefs which challenged the supremacy of the established church, which thus became increasingly intolerant of dissent. The state issued decrees intended to oppress or eradicate not only pagans (including adherents of the older Roman religion and of sects such as Manichaeism) but also Christian groups regarded as heretical (such as Arians and sects influenced by Gnosticism). The most prominent of these decrees is the so-called Theodosian decree which ordered the destruction of all pagan temples (Judaism was exempt), and resulted in the burning of the Serapeum of Alexandria. The state aimed to "suppress all rival religions, order the closing of the temples, and impose fines, confiscation, imprisonment or death upon any who cling to the older Pagan religions." Sanctions included confiscation of property, destruction of religious writings, exile, and sometimes execution. The Roman state church also tolerated acts of violence against Jewish synagogues (see Christianity and anti-Semitism).

The idea that heretics should be punishable by death continued to be supported by some later Christian writers, such as the 13th-century scholar Thomas Aquinas, who held that heretics "deserve not only to be separated from the Church by excommunication, but also to be severed from the world by death", ST II:II 11:3). During the Reformation period, both sides in the conflict thought it appropriate to execute heretics: the radical theologian Michael Servetus was condemned to death by the Roman Catholic authorities, but actually executed by the Protestant authorities in Geneva.

Historical persecution by Christians was also focused on other Christians such as the Cathars in the Albigensian crusade. St. Bernard of Clairvaux wrote: "The Christian glories in the death of the pagan, because Christ is glorified". Inquisitions were also used against domestic populations, to eliminate individuals who expressed divergent opinions. Atrocities committed by the state in the name of Christianity have historically gone hand-in-hand with pogroms by the populace, leading to horrific massacres, such as St. Bartholomew's Day massacre carried out by a Catholic mob against Protestants. Christian mobs, sometimes with government support, have targeted non-Christians. Examples include the destruction of pagan temples and murder of the philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria by a Christian mob.

Christian fundamentalists often use passages in the Bible to criticize homosexuality, and because of the influence of such biblical teachings during the Middle Ages, for centuries, homosexual acts were punishable in Europe by death. Even today, Christian groups, particularly in America, are accused of being at the forefront of homophobia, with extremists such as the Westboro Baptist Church picketing the funerals of murdered homosexuals.

British environmental activist George Monbiot has also argued that Christian fundamentalists are driving the United States's current foreign policy in a misguided effort to hasten the Second Coming of Jesus Christ, to the detriment of all concerned.

Criticism of sexual ethics

Christians are often criticized for relying for their sexual ethics on the social customs and primitive beliefs of ancient societies. Many consider that the teaching of various churches is outdated in its insistence on lifelong heterosexual marriage, its condemnation of sex before or outside marriage (fornication and adultery) and of abortion and contraception are not seen as evil by many. However, Christians may reply that abandoning such moral values has not been wise, judging from the result in modern society.

Criticism of Christian doctrine

Criticism of belief in Hell and damnation

See also: Problem of Hell

Skeptics have criticized Christianity for seeking to persuade people into accepting its authority through simple fear of punishment or hope of reward after death, rather than through rational argumentation or empirical evidence. Traditional Christian doctrine assumes that, without faith in God, one is subject to eternal hellfire. The Epistle of James states that even mere belief is insufficient for salvation, for "the devils believe and also tremble" (James 2:19). Saint Paul also states in Romans that confession of the Lord as your savior entails you will be saved and "He that doubted is damned" (Romans 14:23). Not only is doubt detrimental to salvation, but mere hope to Saint Paul is an unacceptable sign of uncertainty, "For hope that is seen is not hope: for what man sees, why does he yet hope for? (Romans 8:24)" Not only must one have unwavering belief and faith to receive salvation, but according to Saint Augustine, one of the church's prime theologians throughout the medieval era, those who are already saved are predetermined, they however must have been baptized and a member of the church.

Since we all inherit Adam's sin, we all deserve eternal damnation. All who die unbaptized, even infants, will go to hell and suffer unending torment. We have no reason to complain of this, since we are all wicked. (In the Confessions, the Saint enumerates the crimes of which he was guilty in the cradle.) But by God's free grace certain people, among those who have been baptized, are chosen to go to heaven; these are the elect. They do not go to heaven because they are good; we are all totally depraved, except in so far as God's grace, which is only bestowed on the elect, enables us to be otherwise. No reason can be given why some are saved and the rest damned; this is due to God's unmotivated choice. Damnation proves God's justice; salvation His mercy. Both equally display His goodness.

Skeptics have regarded the eternal punishment of those who fail to adopt Christian faith as morally objectionable, and consider that it presents an abhorrent picture of the nature of the world. "God so loved the world that he made up his mind to damn a large majority of the human race." - Robert G. Ingersoll. On a similar theme objections are made against the perceived injustice of punishing a person for all eternity for a temporal crime. Some Christians agree (see Annihilationism and Trinitarian Universalism). These beliefs have been considered especially repugnant when the claimed omnipotent God makes, or allows a person to come into existence, with a nature that desires that which he finds objectionable - see original sin.

Criticism of the concept of atonement

The idea of atonement for original sin is criticised by some on the grounds that the image of God as requiring the suffering and death of Jesus to effect reconciliation with humankind is morally repugnant. The view is summarized by Richard Dawkins: "if God wanted to forgive our sins, why not just forgive them? Who is God trying to impress?".

Robert Green Ingersoll suggests that the concept of the atonement is simply an extension of the Mosaic tradition of blood sacrifice and "is the enemy of morality". The death of Jesus Christ represents the blood sacrifice to end all blood sacrifices; the resulting mechanism of atonement by proxy through that final sacrifice has appeal as a more convenient and much less costly approach to redemption than repeated animal sacrifice – a common sense solution to the problem of reinterpreting ancient religious approaches based on sacrifice.

Criticism based on the delay of the Second Coming

A fundamental belief of Christianity is that Christ will return to the earth to conquer evil and rule over the faithful - a simplified definition of the Second Coming. Since the first century until modern times, some Christian leaders and their followers have prophesied that this would happen, usually during the lifetime of the person making the prophecy, and frequently within the next 20 years after the prophecy. This practice seems to contradict a fundamental Christian principle that says that no one knows when Christ will come (Mark 13:32). The failure of even one of these many prophesies to come true often has the effect of trivializing Christian teachings and making the church seem unreliable.

Several verses in the New Testament appear to contain Jesus' predictions that the Second Coming would take place within a century following his death. Most notably, Matthew 10:22-23, 16:27-28, 23:36, 24:29-34, 26:62-64; Mark 9:1, Mark 14:24-30, 14:60-62; and Luke 9:27. Such statements have contributed to the Preterism movement, a belief that the Second Coming had already taken place by the end of the first century CE.

Atheists conclude from the same verses in the New Testament that lend credence to the Preterism movement that the Second Coming is about 2000 years overdue. Atheists also observe that despite roughly 2000 years of disappointment, faith in the Second Coming is remarkably resilient.

Christianity as a psychological construct

Some scholars and skeptics believe Christianity is often adopted to establish meaning in life and to explain the tragedy of death. Professor Hiroshi Obayashi, former Chair and Professor at the Department of Religious Studies at Rutgers University, argues in his book Death and Afterlife, Perspectives of World Religions that it is in the discovery and quest for the ideal self that the great religions of the world have their origin. Death is something that humans have no firsthand empirical familiarity with. "When challenged by this awesome and unavoidable fact, we, like early people, find ourselves with neither an empirical basis nor the conceptual tools needed to explain its enigma. Therefore we have no choice but to deal with it as yet another form of life - afterlife."

The creation of meaning to man is the self-expression of his personal being, it is the essence of human life. Obayashi states, "History is the stage on which the personal being, individually or collectively, engages in the continuous activity of creating meaning." The creation story adopted by Christians is perhaps more an adoption of meaning in life rather than a biological theory for evolution:

- Thus creation is a term correctly applied to the creation of moral and aesthetic values called meaning, which in the exclusive prerogative of the personal being. That is why creation is the most fundamental metaphor in these personalistic and historical religions of Semitic Origin (not because of any belief in creation as opposed to evolution as a biological theory - a contemporary debate most misplaced and pointless).

Death and mortality pose problems for Semitic religions, Christians answer such a problem in the New Testament. "Death is no longer just a natural process, but the destruction of life's meaning, and afterlife in the New Testament now means the overcoming of death through the creation of meaning... Similarly, neither is afterlife a simple matter of the prolongation of life. It is now connected to salvation, the final establishment or affirmation of the meaning of life."

- What happens is that the personal life overcomes the nay-sayings of death by creating a meaning that defeats the disintegrating effect of death, or by reaffirming the fact that life is meaningful. The ultimate victory and establishment of meaning over meaning-lessness, variously symbolized as salvation, beatitude, or blissfulness, and committed to the mythological language of heaven, kingdom of God, or paradise, are thus presented by these Semitic religions as lying ahead in the future, beyond the reach of death... So, if death is now defined as the wage of sin (i.e., dissolution and negation of meaning), then afterlife is as salvation (i.e., establishment and affirmation of meaning).

Conflicts via afterlife

What often poses problems for Christians is the nature of the afterlife portrayed by the history of the land of Ancient Israel, or the Old Testament. Most scholars believe there is no concept of immortality or life after death in the Old Testament. The human body was shaped by God from the earth, and animated with the "breath of life" (Gen 2:7-8). At death, the person becomes a "dead breath" (Numbers 6:6). Biblical passages such as Ecclesiastes 12:7 state, "the dust returns to the earth as it was", "In Sheol who will praise you?" and "Will the dust praise thee?" The presumption is that the deceased are inert, lifeless, and engaging in no activity. This is portrayed in Job's plea to God:

- Why did I not die at birth,

- come forth from the womb and expire? ...

- From then I should have lain down and been quiet;

- I should have slept; then I should have been at rest...

- There the wicked cease from troubling,

- and there the weary are at rest.

- There the prisoners are at ease together;

- they hear not the voice of the taskmaster .

- The small and the great are there,

- and the slave is free from his master.

The idea of Sheol or a state of nothingness was shared among Babylonian and Israelite beliefs. "Sheol, as it was called by the ancient Israelites, is the land of no return, lying below the cosmic ocean, to which all, the mighty and the weak, travel in the ghostly form they assume after death, known as Raphraim. There the dead have no experience of either joy or pain, perceiving no light, feeling no movement." Professor Obayshi alludes that the Israelites were satisfied with such a shadowy realm of afterlife because they were more deeply concerned with survival. This theme of prosperity via unity is very much portrayed in the book of Joshua. The descendants of Moses, led from Egypt, follow Joshua into Canaan where they capture much of the land, the book ascribes this to their religious piety. The famed walls of Jericho even fall when Priests encircle the walls and blow ram horns. This theme of unity resonates in the next stanza where Joshua suffers a setback at the easily conquerable town of Ai. God lets the Israelites lose in battle because a man stole booty from the victory prior, this exemplifies the Old Testament's logic of salvation via collective survival.

Joshua summons the man named Achan with his sons and daughters and stones him to death (7:24-26). This leads to God's full endorsement where they are commanded to genocide the 12,000 inhabitants of the town (8:18). The town is then burned to the ground, the king is hanged (8:28-29), and men and women are killed by the sword "in the open country and wilderness" (8:24). Recent Archaeology has revealed that the town of Ai was destroyed 1,000 years before the story took place, 500 years before the fall of Jericho, however the cult-like theme of unity and sheol which largely shaped the ancient tradition of Judaism and thus Christianity is later dispersed when only the most pious of Jews were being massacred during the Maccabean revolt.

- The suffering during the Maccabean period became the most serious challenge to the old Israelite thinking. This time it was not the shared suffering of all the Jews, but only those who remained loyal to the Torah who suffered and died. Thus the ancient belief of Sheol, the underworld, which summarized the common fate of all the Jews, proved no longer satisfactory. The logic of salvation that focused only on corporate or collective survival was no longer sufficient. The fate of the individual who perished for the faith had to be addressed. It was through this situation that the idea of resurrection, which Robert Goldenberg calls "the most individualistic of all religious conceptions," was introduced into Judaism... Resurrection and apocalypticism were the Judaic answer to changing times.

Criticism of Christian Scripture

See also: Criticism of the Bible, The Bible and History, and Internal consistency and the Bible

Many skeptics reject Christianity because of its reliance on the Bible, the most recent parts of which were written during the Roman period, almost 2000 years ago, with older parts dating back many centuries before that.

The Old Testament, also known as the Hebrew Bible, is a history of the land of Israel. God gave Abraham unconditional promises entailing multitudinous progeny, nationhood, royal leaders, and land possession. The Hebrew Bible's prophetic literature ends waiting for Judah to be restored via a new monarch, one who will restore the Davidic kingdom and possibly create universal peace. The New Testament traces Jesus' line to that of David; however according to Professor Stephen L Harris:

- Jesus did not accomplish what Israel's prophets said the Messiah was commissioned to do: He did not deliver the covenant people from their Gentile enemies, reassemble those scattered in the Diaspora, restore the Davidic kingdom, or establish universal peace (cf Isa.9:6-7; 11:7-12:16, etc.) Instead of freeing Jews from oppressors and thereby fulfilling God's ancient promises - for land, nationhood, kingship, and blessing - Jesus died a "shameful" death (Deut 21:24), defeated by the very political powers the Messiah was prophesied to overcome. Indeed, the Hebrew prophets did not foresee that Israel's savior would be executed as a common criminal by Gentiles (John 7:12,27,31,40-44), making Jesus' crucifixion a "stumbling block" to scripturally literate Jews (1 Cor. 1:23).

Many skeptics have composed lists of conflicts involving the Bible, perhaps none so renowned as Robert G. Ingersoll's 61 reasons in his article Inspiration Of Bible.

Conflicting passages

Main article: Internal_consistency_and_the_Bible § Specific_textual_inconsistenciesMany critics point to general inconsistency between different sections of the Bible, or to perceived specific contradictions in matters of detail. Most of these reflect a disparity between the Old Testament, identified with a jealous and vengeful God, lack of tolerance, and often violent attitude towards non-believers living near Jewish cities and lands, and the New Testament, identified with God as a loving father and an approach to salvation inclusive of all cultures. Even apart from the perceived specific contradictions of detail, the overall discrepancy between Biblical texts from widely different historical periods are a major cause of skepticism regarding Biblical inspiration. (Evangelical or Fundamentalist Christians generally respond by attempting to show that the inconsistencies are only apparent at first glance and ultimately non-existent, while liberal Christians seek to reconcile Christian belief with a critical approach, accepting that the text reflects its historical context and is not verbally infallible.)

Selective interpretation

Main article: Cafeteria ChristianitySometimes particular attention is directed to Jewish rules contained in the Old Testament which are not observed by Christians . Many of the rules in question are specifically abrogated by the New Testament, such as circumcision and the entire Law is described by Galatians 3:24–25 as a tutor which is no longer necessary, according to Antinomianism. The alleged hypocrisy is in the continued invocation of portions of the Old Testament that are considered obsolete under Christianity, particularly when those portions endorse hostility towards women and homosexuals.

Matthew 5:17–19 (see also Adherence to the Law) can be taken to imply that the Old Testament laws remain in place in the New Testament, while Matthew 5:38–39 (see also Antithesis of the Law and Christian view of the Law) can be viewed as contradicting those earlier passages. Simple investigation yields many apparent contradictions in the Bible, which some use to argue against belief in the Bible as the absolute, inerrant 'Word of God.' See Conflicting|Passages above.

While consideration of the context is necessary when studying the Bible, some find the four different accounts of the Resurrection of Jesus within the four Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, difficult to reconcile.

Mistranslation and textual corruption

Criticisms are also sometimes raised because of contradictions arising between different English translations of the Hebrew or Greek text. Some Christian interpretations are criticized by non-Christians (and sometimes particularly by Jewish believers) as being based on mistranslations, or on readings found in only some manuscripts of the Bible, or in particular English translations of the Bible.

Newly discovered ancient manuscripts of the Bible, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls and Codex Sinaiticus, suggest that passages such as the Pericope Adulteræ, and Mark 16 and Comma Johanneum originally took other forms than are present in older translations such as the King James Version, or were even absent. There is also the question of whether the masoretic text, which forms the basis of most modern English translations of the Old Testament, is the more accurate or whether one of the translations which pre-dates the masoretic text, such as the Septuagint, Syriac Peshitta, and Samaritan Pentateuch is more accurate.

Some accuse Christians of translating the Bible in a dishonest way to make the text reflect Christian doctrine. For example, Muslim convert Gary Miller (Abdul-Ahad Omar) points out that modern English translations avoid using the word worship in some contexts ("Nebuchadnezzar came to Daniel and he worshiped him") while crucially retaining it in others ("a man came to Jesus and he worshiped him"). and that the word Messiah or "anointed one" is translated differently when applied to Cyrus the Persian in Isaiah, chapter 45, and when applied to Jesus. This Miller claims that this is a deliberately inconsistent translation, in order to "give us the impression that there is only one Messiah, one Christ and no other."

Bart D. Ehrman makes similar claims in his book Misquoting Jesus. In Chapter 7 of the book, he discusses theologically motivated alterations of the text. He argues, for example, that scribes added Luke 22:43-44 in an attempt to counter the arguments that Jesus was not fully human and did not have a body. In Chapter 8, he argues that texts were changed in order to minimize the role of women and counter the Jews and pagans.

Virgin: Matthew 1:22–1:23 reads: "All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had said through the prophet: "The virgin will be with child and will give birth to a son, and they will call him Immanuel" — which means, "God with us." This verse is, according to Jews (and other critics of the doctrine of the Virgin Birth), a misquoting of Isaiah 7:14. Jewish translations of the verse reads: "Behold, the young woman is with child and will bear a son and she will call his name Immanuel." Moreover, it is claimed that Christians have taken this verse out of context (see Immanuel for further information).

Another example is Matthew 2:23: "And he came and dwelt in a city called Nazareth, that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the prophets, 'He shall be called a Nazarene.'" A Jewish website claims that "Since a Nazarene is a resident of the city of Nazareth and this city did not exist during the time period of the Jewish Bible, it is impossible to find this quotation in the Hebrew Scriptures. It was fabricated." However, one common suggestion is that the New Testament verse is based on a passage relating to Nazirites, either because this was a misunderstanding common at the time, or through deliberate re-reading of the term by the early Christians.

Criticism of disagreement among Christians

Some have argued that Christianity is undermined by the inability of Christians to agree on matters of faith and church governance, and the tendency for the content of their faith to be determined by regional or political factors. Schopenhauer sarcastically suggests that Christian beliefs are affected by climate:

- The Catholic clergy, for example, are fully convinced of the truth of all the tenets of their Church, and so are the Protestant clergy of theirs, and both defend the principles of their creeds with like zeal. And yet the conviction is governed merely by the country native to each; to the South German ecclesiastic the truth of the Catholic dogma is quite obvious, to the North German, the Protestant. If then, these convictions are based on objective reasons, the reasons must be climatic, and thrive, like plants, some only here, some only there. The convictions of those who are thus locally convinced are taken on trust and believed by the masses everywhere.

Criticism of Example set by Christians

The behaviour of Christians has been subject to criticism through the bad example they set.Mahatma Gandhi: "I like your Christ. I do not like your Christians. Your Christians are so unlike your Christ." The materialism of affluent Christian countries appears to contradict the claims of Jesus Christ that says it's not possible to worship both Mammon and God at the same time. At times the example of Christians may be a contributory factor resulting in atheism. "..believers can have more than a little to do with the birth of atheism. To the extent that they neglect their own training in the faith, or teach erroneous doctrine, or are deficient in their religious, moral, or social life, they must be said to conceal rather than reveal the authentic face of God and religion".

Criticism of Christianity as derivative

| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Some scholars have argued that Christianity adopted many mythological tales and traditions into its theological interpretations of Jesus. These traditions, largely from other Greco-Roman religions, very much parallel the story of Jesus of Nazareth and his ethical treatise. Concerning this, Professor Stephen L Harris, Professor and Chair of Department of Humanities and Religious Studies at California State University, writes:

- Scholars of world religion and mythology detect numerous parallels between the stories of heroes and gods from widely different cultures and periods. Tales of mortal heroes who ultimately become gods characterize the ancient traditions of Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, Greece, and Rome, as well as the native cultures of Mesoamerica and North America. In comparing the common elements found in the world's heroic myths, scholars discern a number of repeated motifs that form a distinctive pattern.

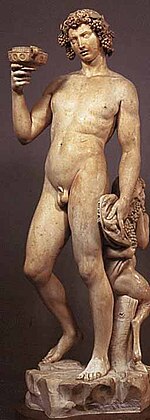

Dionysus

See also: Osiris-Dionysus and Dionysus

The story of Dionysus, son of the Greek Olympian God Zeus, has been seen by several writers as containing parallels to the story of Jesus. Professor Harris writes in his book Understanding the Bible that "the myth of Dionysus foreshadows some later Christian theological interpretations of Jesus' cosmic role. Although Jesus is a historical figure and Dionysus purely mythological, Dionysus's story contains events and themes, such as his divine parentage, violent death, descent into the Underworld, and subsequent resurrection to immortal life in heaven, where he sits near his father's throne, that Christians ultimately made part of Jesus' story. Like Asclepius, Heracles, Perseus, and other heroes of the Greco Roman era, Dionysus has a divine father and human mother. The only Olympian born to a mortal woman, he is also the only major deity to endure rejection, suffering, and death before ascending to heaven to join his immortal parent. The son of Zeus and Semele, a princess of Thebes, Dionysus was known as the "twice born."

Dionysus also parallels the life of Jesus as he and Demeter gave humanity two gifts to come into communion with the divine: grain (or bread) to sustain life and wine to make life bearable. The Athenian Euripides, a playwright from 485-406 BCE, writes in his The Bacchae:

- Next came the son of the virgin. Dionysus.

- bringing the counterpart to bread. wine

- and the blessings of life's flowing juices.

- His blood, the blood of grape,

- lightens the burden of our mortal misery...

- it is his blood we pour out

- to offer Thanks to the Gods. And through him.

- we are blessed.

Professor Harris alludes that "long before Jesus linked wine and bread as part of the Christian liturgy (Mark 14:22-25; Luke 22:17-20) the two tokens of divine favor were associated in the Dionysian tradition. In the Bacchae (worshippers of Bacchus, another name for Dionysus), the Athenian playwright Euripides (c. 485-406 BCE) has the prophet Tiresias observe that Demeter and Dionysus, respectively, gave humanity two indispensable gifts: grain or bread to sustain life and wine to make life bearable. Tiresias urges his hearers to see in Dionysus's gift of wine a beverage the brings into communion with the divine.

- One particular wine ritual of the Dyonisian myth followers involved priests and guests. The priests would leave three empty pots in a building for all citizens to see. Pausanias states in his Description of Greece, "The doors of the building are sealed by the priests themselves and by any others who may so be inclined. On the morrow they are allowed to examine the seals, and on going into the building they find the pots filled with wine."

According to Professor Luther H. Martin in his Hellenistic Religions, this wine tradition and that of the emblem liknon, or the process of purifying wheat from chaff via agency of the spirit, was adopted by the earliest Christians.

- "This Dionysian wine ritual was incorporated into Christian imagery by the Gospel of John. According to this gospel, the first public act of Jesus was to transform jars of water into wine- the typical Dionysian epiphany miracle. By employing this well-known Dionysian convention, the Gospel at its outset establishes the presence of Jesus as a divine epiphany...the Dionysian liknon represented the possibility of an ecstatic purification by the breath of the spirit as initiates transcended the conditions of everydayness. This image of separating wheat from the chaff through the agency of spirit was also employed by the early Christians (Matt 3:11-12; Luke 3:16-17)."

The list scholars have compiled for parallels of Jesus and Dionysus include:

- Birth to a divine parent

- Narrow escape from attempts to kill him as an infant

- Some "missing" formative years

- Sudden appearance as a young adult manifesting miraculous gifts

- Struggle with evil forces

- Return to his place of origin, commonly resulting in rejection

- Gift of wine and bread for communion

- His betrayal, suffering, and death

- His resurrection to divine status leading to the establishment of a cult honoring his name.

Horus

Some critics of the historicity of Jesus have pointed to similarities between the stories of Jesus and some late (Hellenistic) versions of ancient Egyptian myths involving Horus and Osiris. For example, the death and resurrection of Horus-Osiris and Horus' nature as both the son of Osiris and Osiris himself, have been seen as foundations for the later Christian doctrines of the resurrection of Jesus and of the Trinity.

A few scholars and critics theorize further that certain elements of the story of Jesus were embellishments, copied from legends surrounding Horus through an abrupt form of syncretism. Indeed, some even claim that the historical figure of Jesus was copied from Horus wholesale, and retroactively made into a Jewish teacher ; these assert that Horus was the basis for elements, such as the infancy narratives, which are found independently in Matthew and Luke, and not in Mark or in the hypothetical source called Q.

Mithras

Comparisons are also made with the tale of Mithras, whose cult was popular during the period of the origin of Christianity.

Responses

A classic response to this criticism is that of J. R. R. Tolkien and subsequently C. S. Lewis, who considered that just because a story was a myth does not preclude it from also having taken place as a historical event. Pagan myths can be seen as prefiguring the life and death of Christ, but without detracting from their historical and religious significance. Lewis even went so far as to suggest that the existence of these Pagan myths lend Christianity credibility, as their existence might reflect God's hidden watch over all human history and His influence on the collective subconscious in the form of "good dreams" and premonitions. Lewis states that he would be far more doubtful of the reality of a supposed historical event the magnitude of the Atonement if humanity had neglected to anticipate it in any way.

See also

- Anti-clericalism

- Anti-Catholicism

- Anti-Protestantism

- Biblical cosmology

- Biblical literalism

- Christian apologetics

- Criticism of Jesus

- Criticism of Atheism

- Criticism of Judaism

- Criticism of Mormonism

- Criticism of Islam

- Criticism of Religion

- Judaism and Christianity

- Science and the Bible

Notes

- The Anti-Christ, Friedrich Nietzsche.

- William Kingdon Clifford, "The Ethics of Belief"

- Is Belief in God Rational in Rationality and Religious Belief, ed. C.F. Delaney, Notre Dame University Press, 1979, p.27)

- Bertrand Russell, Human Society in Ethics and Politics

- Address on Christianity as the Religion according to Reason

- A Christmas Sermon, Robert Ingersoll.

- A personal Voyage, Carl Sagan.

- From Ferngren's introduction:

"...while Brooke's view has gained widespread acceptance among professional historians of science, the traditional view remains strong elsewhere, not least in the popular mind. (p. x) - Gary Ferngren, (2002); Introduction, p. ix) - Gary Ferngren (editor). Science & Religion: A Historical Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8018-7038-0. (Introduction, p. ix)

- The compass in this 13th century manuscript is a symbol of God's act of Creation.

* Thomas Woods, How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization, (Washington, DC: Regenery, 2005), ISBN 0-89526-038-7 - "J.L. Heilbron". London Review of Books. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

- Lindberg, David (2003). When Science and Christianity Meet. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-48214-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Goldstein, Thomas (1995). Dawn of Modern Science: From the Ancient Greeks to the Renaissance. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80637-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Pope John Paul II (1998). "Fides et Ratio (Faith and Reason), IV". Retrieved 2006-09-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Robinson, B. A. (2006). "Christianity and slavery". Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ Ostling, Richard N. (Sept 17th, 2005). "Human slavery: why was it accepted in the Bible?". Salt Lake City Desert News. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Ostling, Richard N. (Sept 17th, 2005). "Human slavery: why was it accepted in the Bible?". Salt Lake City Desert News. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Abolitionist Movement". MSN Encyclopedia Encarta. Microsoft. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- "Civil Rights Movement in the United States". MSN Encyclopedia Encarta. Microsoft. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- "Religious Revivalism in the Civil Rights Movement". African American Review. Winter, 2002. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Martin Luther King: The Nobel Peace Prize 1964". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2006-01-03.

- ^ Hopfe, Lewis M. (2005). Religions of the World. Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson. pp. 290–1. 0131195158.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "hopfe" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - Paul describes himself as "an Israelite of the tribe of Benjamin, circumcised on the eighth day" 3:5 Phil 3:5

- Hopfe, Lewis M. (2005). Religions of the World. Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson. p. 299. 0131195158.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Predominant Religions". Adherents.com. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- "The Christian Revolution: The Changing Demographics of Christianity". World Christianity. St. John in the Wilderness Adult Education and Formation. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ Miller, Sara (July 17, 2002). "Global gospel: Christianity is alive and well in the Southern Hemisphere". Christian Century. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- "The Christian Revolution: The Changing Demographics of Christianity". World Christianity. St. John in the Wilderness Adult Education and Formation. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- "The Christian Revolution: The Changing Demographics of Christianity". World Christianity. St. John in the Wilderness Adult Education and Formation. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- Thomas Ash (March 4 2002). "The German Churches' Response To Nazism". Big Issue Ground. Retrieved 2006-11-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - A List of Quotations on the Fear of Hell

- "Let no cultured person draw near, none wise and none sensible, for all that kind of thing we count evil; but if any man is ignorant, if any man is wanting in sense and culture, if anybody is a fool, let him come boldly . Celsus, AD178

- A history of Western Philosophy by Bertrand Russell, Simon & Schuster, 1945

- Bible Teaching and Religious Practice essay: "Europe and Elsewhere", Mark Twain, 1923)

- Albert Einstein, Out of My Later Years (New York: Philosophical Library, 1950), p. 27.

- ^ Hiroshi Obayashi, Death and the Afterlife: Perspectives of World Religions. (Praeger Publishers, 1992.) See Introduction

- From Witchcraft to Justice: Death and Afterlife in the Old Testament, George E. Mendenhall.

- See Psalm 6:6

- See Psalm 30:9

- From Witchcraft to Justice: Death and Afterlife in the Old Testament, George E. Mendenhall.

- See Job 3:11, 13-15, 17-19

- ^ Hiroshi Obayashi, Death and Afterlife: Perspectives of World Religions. See Introduction.

- Shifting Ground in the Holy Land, Jennifer Wallace. Smithsonian Magazine, May 2006.

- Stephen L. Harris, Understanding the Bible. (McGraw Hill, 2002) p 376-7

- Gary Miller: "What the Gospels Mean to Muslims"

- Gary Miller: "Some Thoughts on the "Proofs" of the Alleged Divinity of Jesus"

- ^ English Handbook Page 34

- Schopenhauer, Arthur. "Religion: A Dialogue". The Essays of Arthur Schopenhauer.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - luke 16:13 “No servant can serve two masters; for either he will hate the one and love the other, or else he will be loyal to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon.”

- William Rees-Mogg 4 April 2005 edition of the The Times

- Gaudium et Spes, 19

- ^ Stephen L. Harris, Understanding the Bible. (McGraw Hill, 2002) p 362-3

- Stephen L. Harris, Understanding the Bible. (McGraw Hill, 2002) p 361

- Euripides, The Bacchae. (Plume Publishers, 1982.) Translated by Michael Cacoyannis. p 18

- Pausanias, Description of Greece: Attica and Corinth. (Harvard University Press, 1918.) VI, 26, 1-2

- Luther H. Martin, Hellenistic Religions: An Introduction. (Oxford University Press, 1987.) P 95-6

References

- Joseph McCabe, "A Rationalist Encyclopaedia: A book of reference on religion, philosophy, ethics and science," Gryphon Books (1971). Excerpts appear at: http://www.christianism.com/

Further reading

- Letter to a Christian Nation, by Sam Harris

- From Jesus to Christianity, by Michael L White

- The Birth of Christianity : Discovering What Happened in the Years Immediately After the Execution of Jesus, by John Dominic Crossan

- Einstein and Religion, by Max Jammer

- Understanding the Bible, by Stephen L Harris

- Russell on Religion, by Louis Greenspan (Includes most all of Russell's essays on religion)

- Out of my later years and the World as I see it, by Albert Einstein

- Future of an illusion, by Sigmund Freud

- Civilization and its discontents, by Sigmund Freud

- Why I am not a Christian and other essays, by Bertrand Russell

- Death and Afterlife, Perspectives of World Religions, by Hiroshi Obayashi

- Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why, by Bart Ehrman

External links

Historical perspective

- From Jesus to Christ, an objective study on Jesus of Nazareth from professors at Harvard, Yale, Brown, Stanford, Princeton, and Duke.

- Professor James Tabor's educational site on the Jewish Roman world of Jesus

- PBS Special: Apocalypse! Contains Jesus' apocalyptic promises along with those of Saint Paul's.

- Roman Sources on the Jews and Judaism, 1 BCE-110 CE

Anti-semitism

Skeptical

- The Warfare of Science With Theology by Andrew White

- Contradictions in the Bible from the Skeptic's Annotated Bible

- New Testament contradictions by Paul Carlson

Apologetic

- Virtual Office of William Lane Craig from Leadership University (web portal)

- Probe Ministries

- Christian Apologetics and Research Ministry

- Tekton Apologetics Ministries

Islamic Point of Critics about Christianity

- Answering Christianity "Islam's Answers"

- Critics about Trinity

- Contradiction in Bible

- Pedophilia in Bible

- Other Critics about Bible