| Revision as of 15:14, 29 July 2022 editDarylprasad (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users6,982 edits removing old text that was in breach of copyrightTags: Reverted copyright violation template removed nowiki added Visual edit: Switched← Previous edit | Revision as of 15:15, 29 July 2022 edit undoPraxidicae (talk | contribs)Edit filter helpers, Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, IP block exemptions, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers169,003 edits Reverted 1 edit by Darylprasad (talk): Once again..Tags: Twinkle Undo RevertedNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{copyvio-revdel|url=https://www.talentshare.org/~mm9n/articles/cosmos/5.htm|url2=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/plotinus/|start1=1094150342|end1=1101132711}} | |||

| {{Short description|Greek philosopher and founder of neoplatonism (204 or 205–270)}} | |||

| {{Short description|Greek philosopher and founder of neoplatonism (c. 204/5–270)}} | |||

| {{Distinguish|Photinus}} | {{Distinguish|Photinus}} | ||

| {{Infobox philosopher | {{Infobox philosopher | ||

| | region = ] | | region = ] | ||

| | era = ] | | era = ] | ||

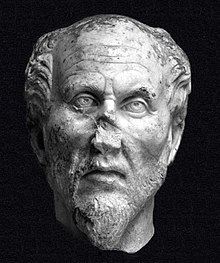

| | image = Plotinos.jpg | | image = Plotinos.jpg | ||

| | caption = Head in white marble. The identification as Plotinus is plausible but not proven. | |||

| | caption = Portrait in white marble from the second half of the 3rd century CE, perhaps of Plotinus, located in the ]<ref>{{Cite web |date=8 May 2022 |title=Regio V - Insula II - Terme del Filosofo (V,II,6-7) (Baths of the Philosopher) |url=http://www.ostia-antica.org/regio5/2/2-6.htm |url-status=live |access-date=13 July 2022 |website=Ostia - Virtual museum}}</ref>{{Sfn|Hermansen|1982|p=78|loc=The Guilds of Ostia}} | |||

| | name = Plotinus | | name = Plotinus | ||

| | birth_date = 204 |

| birth_date = {{circa|204/5}} | ||

| | birth_place = ] |

| birth_place = ] or ], ], ] | ||

| | death_date = {{Death year and age|270| |

| death_date = {{Death year and age|270|205}} | ||

| | death_place = ], Roman Empire | | death_place = ], Roman Empire | ||

| | notable_works = '']''<ref name="Gerson 2017">{{cite book |author-last=Gerson |author-first=Lloyd P. |author-link=Lloyd P. Gerson |year=2017 |chapter=Plotinus and Platonism |editor1-last=Tarrant |editor1-first=Harold |editor2-last=Renaud |editor2-first=François |editor3-last=Baltzly |editor3-first=Dirk |editor3-link=Dirk Baltzly |editor4-last=Layne |editor4-first=Danielle A. |title=Brill's Companion to the Reception of Plato in Antiquity |location=] and ] |publisher=] |series=Brill's Companions to Classical Reception |volume=13 |pages=316–335 |doi=10.1163/9789004355385_018 |isbn=978-90-04-27069-5 |issn=2213-1426}}</ref> | |||

| | notable_works = '']''{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=1|loc=General Introduction to the Translations}} | |||

| | school_tradition = ]<ref name="Gerson 2017"/><ref name="Britannica">{{cite encyclopedia |last1=Armstrong |first1=A. Hilary |last2=Duignan |first2=Brian |last3=Lotha |first3=Gloria |last4=Rodriguez |first4=Emily |date=1 January 2021 |origyear=20 July 1998 |title=Plotinus |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Plotinus |encyclopedia=] |location=] |publisher=] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210417025334/https://www.britannica.com/biography/Plotinus |archive-date=17 April 2021 |url-status=live |access-date=5 August 2021 |quote=Plotinus (born 205 CE, Lyco, or Lycopolis, Egypt?—died 270, Campania), ancient philosopher, the centre of an influential circle of intellectuals and men of letters in 3rd-century Rome, who is regarded by modern scholars as the founder of the neoplatonic school of philosophy. In his 28th year—he seems to have been rather a late developer—Plotinus felt an impulse to study philosophy and thus went to ]. He attended the lectures of the most eminent professors in Alexandria at the time, which reduced him to a state of complete depression. In the end, a friend who understood what he wanted took him to hear the self-taught philosopher ]. When he had heard Ammonius speak, Plotinus said, “This is the man I was looking for,” and stayed with him for 11 years. At the end of his time with Ammonius, Plotinus joined the expedition of the ] ] against ] (242–243), with the intention of trying to learn something at first hand about the philosophies of the Persians and Indians. The expedition came to a disastrous end in ], however, when Gordian was murdered by the soldiers and ] was proclaimed emperor. Plotinus escaped with difficulty and made his way back to ]. From there he went to ], where he settled at the age of 40. Plotinus's own thought shows some striking similarities to ], but he never actually made contact with Eastern sages because of the failure of the expedition. Though direct or indirect contact with Indians educated in their own religious-philosophical traditions may not have been impossible in 3rd-century Alexandria, the resemblances of the philosophy of Plotinus to Indian thought were more likely a natural development of the Greek tradition that he inherited.}}</ref><ref name="Stanford1">{{cite encyclopedia |author-last=Gerson |author-first=Lloyd P. |date=Fall 2018 |title=Plotinus |url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/plotinus/ |editor-last=Zalta |editor-first=Edward N. |editor-link=Edward N. Zalta |encyclopedia=] |publisher=The Metaphysics Research Lab, ], ] |issn=1095-5054 |oclc=643092515 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181126171129/https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/plotinus/ |archive-date=26 November 2018 |access-date=5 August 2021 |quote=Plotinus (204/5 – 270 C.E.), is generally regarded as the founder of neoplatonism. He is one of the most influential philosophers in antiquity after ] and ]. The term ‘neoplatonism’ is an invention of early 19th century European scholarship and indicates the penchant of historians for dividing ‘periods’ in history. In this case, the term was intended to indicate that Plotinus initiated a new phase in the development of the Platonic tradition. What this ‘newness’ amounted to, if anything, is controversial, largely because one's assessment of it depends upon one's assessment of what Platonism is. In fact, Plotinus (like all his successors) regarded himself simply as a Platonist, that is, as an expositor and defender of the philosophical position whose greatest exponent was Plato himself. The three basic principles of Plotinus' metaphysics are called by him ‘the One’ (or, equivalently, ‘the Good’), Intellect, and Soul. These principles are both ultimate ontological realities and explanatory principles. Plotinus believed that they were recognized by Plato as such, as well as by the entire subsequent Platonic tradition. ] informs us that during the first ten years of his time in Rome, Plotinus lectured exclusively on the philosophy of Ammonius. During this time he also wrote nothing. Porphyry tells us that when he himself arrived in Rome in 263, the first 21 of Plotinus' treatises had already been written. The remainder of the 54 treatises constituting his ''Enneads'' were written in the last seven or eight years of his life.}}</ref><ref name="Siorvanes 2018">{{cite book |author-last=Siorvanes |author-first=Lucas |year=2018 |chapter=Plotinus and Neoplatonism: The Creation of a New Synthesis |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NfxdDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA847 |editor1-last=Keyser |editor1-first=Paul T. |editor2-last=Scarborough |editor2-first=John |title=Oxford Handbook of Science and Medicine in the Classical World |location=] |publisher=] |doi=10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199734146.013.78 |pages=847–868 |isbn=9780199734146 |lccn=2017049555}}</ref> | |||

| | school_tradition = ]{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=9|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}}{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=21|loc=Platonist Curricula and their Influence by Tarrant}}{{Sfn|Gerson|2010a|p=439|loc=Hierocles of Alexandria by Schibli}}{{Sfn|Sorabji|2005|p=6|loc=Introduction}} | |||

| | main_interests = ], ], ] |

| main_interests = ], ], ]<ref name="Gerson 2017"/><ref name="Stanford1"/><ref name="Siorvanes 2018"/><ref name="Halfwassen 2014">{{cite book |author-last=Halfwassen |author-first=Jens |year=2014 |chapter=The Metaphysics of the One |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yhcWBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA182 |editor1-last=Remes |editor1-first=Pauliina |editor2-last=Slaveva-Griffin |editor2-first=Svetla |title=The Routledge Handbook of Neoplatonism |location=] and ] |publisher=] |series=Routledge Handbooks in Philosophy |pages=182–199 |isbn=9781138573963}}</ref> | ||

| | notable_ideas = ] of all things from ] |

| notable_ideas = ] of all things from ]<ref name="Halfwassen 2014"/><br/>Three main ]: ], ], and ]<ref name="Stanford1"/><ref name="Halfwassen 2014"/><br/>]<ref name="Halfwassen 2014"/> | ||

| | influences = {{flatlist| | | influences = {{flatlist| | ||

| * ] |

* ]<ref name="Gerson 2017"/><ref name="Britannica"/><ref name="Stanford1"/><ref name="Siorvanes 2018"/> | ||

| * ] |

* ]<ref name="Gerson 2017"/> | ||

| * ] |

* ]<ref name="Gerson 2017"/><ref name="Britannica"/><ref name="Siorvanes 2018"/> | ||

| * ]<ref name="Stamatellos 2007">{{cite book |last=Stamatellos |first=Giannis |year=2007 |chapter=Matter and Soul |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0r0yH93JWOIC&pg=PA161 |title=Plotinus and the Presocratics: A Philosophical Study of Presocratic Influences on Plotinus' Enneads |location=] |publisher=] |pages=161–172 |isbn=978-0-7914-7061-9 |lccn=2006017562}}</ref> | * ]<ref name="Stamatellos 2007">{{cite book |last=Stamatellos |first=Giannis |year=2007 |chapter=Matter and Soul |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0r0yH93JWOIC&pg=PA161 |title=Plotinus and the Presocratics: A Philosophical Study of Presocratic Influences on Plotinus' Enneads |location=] |publisher=] |pages=161–172 |isbn=978-0-7914-7061-9 |lccn=2006017562}}</ref> | ||

| * ]<ref name="Stamatellos 2007"/> | * ]<ref name="Stamatellos 2007"/> | ||

| Line 27: | Line 28: | ||

| * ]<ref name="Stamatellos 2007"/> | * ]<ref name="Stamatellos 2007"/> | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| | influenced = ], |

| influenced = ],<ref name="Gerson 2017"/> ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Neoplatonism}} | {{Neoplatonism}} | ||

| '''Plotinus''' ({{IPAc-en|p|l|ɒ|ˈ|t|aɪ|n|ə|s}}; {{lang-grc-gre|Πλωτῖνος}}, ''Plōtînos''; {{circa|204/5}} – 270 CE) was a ] in the ] tradition, born and raised in ]. Plotinus is regarded by modern scholarship as the founder of ].<ref name="Gerson 2017"/><ref name="Britannica"/><ref name="Stanford1"/><ref name="Siorvanes 2018"/> His teacher was the self-taught philosopher ], who belonged to the ].<ref name="Gerson 2017"/><ref name="Britannica"/><ref name="Stanford1"/><ref name="Siorvanes 2018"/> Historians of the 19th century invented the term "neoplatonism"<ref name="Stanford1"/> and applied it to refer to Plotinus and his philosophy, which was vastly influential during ], the ], and the ].<ref name="Stanford1"/><ref name="Siorvanes 2018"/> Much of the biographical information about Plotinus comes from ]'s preface to his edition of Plotinus' most notable literary work, '']''.<ref name="Gerson 2017"/> In his ] writings, Plotinus described three fundamental principles: ], ], and the ].<ref name="Stanford1"/><ref name="Halfwassen 2014"/><ref>{{cite web|title=Who was Plotinus?|website=] |url=http://www.abc.net.au/rn/philosopherszone/stories/2011/3237626.htm|date=2011-06-07}}</ref> His works have inspired centuries of ], ], ], ], and ] metaphysicians and ], including developing precepts that influence mainstream theological concepts within religions, such as his work on duality of the One in two metaphysical states. | |||

| '''Plotinus''' ({{IPAc-en|p|l|ɒ|ˈ|t|aɪ|n|ə|s}}; {{lang-grc-gre|Πλωτῖνος}}, ''Plōtînos'') (204{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=1|loc=General Introduction to the Translations}}{{Sfn|Remes|2008|p=19|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Corrigan|2005|p=1|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Edwards|2000|p=xxiv|loc=Introduction}} or 205{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=1|loc=General Introduction to the Translations}}{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=ii|loc=front matter}}{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=126|loc=Plotinus’ style and argument by Brisson}}{{Sfn|Remes|2008|p=19|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=7 (footnote 1)|loc=The Life of Plotinus}}–270 CE{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=1|loc=General Introduction to the Translations}}{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=ii|loc=front matter}}{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=129|loc=Plotinus’ style and argument by Brisson}}{{Sfn|Remes|2008|p=19|loc=Introduction}}) was a neoplatonic{{Sfn|Pavlos|Janby|Emilsson|Tollefsen|2019|p=203|loc=The doctrine of immanent realism in Maximus the Confessor by Mateiescu}} philosopher likely to have been born in Lycopolis (modern day ]{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=126|loc=Plotinus’ style and argument by Brisson}}{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=4|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}}{{Sfn|MacKenna|Page|1952|p=v|loc=Biographical Note}}), Roman{{Sfn|Copenhaver|2002|p=xx|loc=Introduction}} Egypt,{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=|loc=Life, works and philosophical background|pp=11-12}}{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=126|loc=Plotinus’ style and argument by Brisson}}{{Sfn|Remes|2008|p=19|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Corrigan|2005|p=1|loc=Introduction}} and is regarded by contemporary scholarship as the founder of ].{{Sfn|Remes|2008|p=1|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=ii|loc=front matter}}<ref name=":1">{{Cite web |last=Armstrong |first=A. Hilary |date=1 January 2022 |others=Lotha, Duignan, Rodriguez |title=Plotinus |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Plotinus |url-status=live |access-date=12 July 2022 |website=Encyclopedia Britannica}}</ref><ref name=":2">{{Cite web |last=Gerson |first=Lloyd |date=28 June 2018b |title=Plotinus |url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/plotinus/ |url-status=live |access-date=12 July 2022 |website=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |ref={{sfnref|Gerson|2018b}}}}</ref> His name is of Roman{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=12|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}}{{Sfn|Inge|1948a|p=114|loc=Forerunners of Plotinus}} origin and he was from a Greek,{{Sfn|Gerson|1999|p=2|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=5|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}} Roman{{Sfn|Gerson|2010|p=xii|loc=Introduction}} or a ] Egyptian family.{{Sfn|Gerson|1999|p=2|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=5|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}} | |||

| Before Plotinus established the first neoplatonic school in Rome in 245 CE,{{Sfn|Remes|2008|p=1|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Corrigan|2005|p=1|loc=Introduction}} he was taught in ] for about 10 or 11 years by the self-taught<ref name=":1" /> philosopher ],{{Sfn|Gerson|2018a|p=317|loc=Plotinus and Platonism by Gerson}} who belonged to the ] tradition.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018b|loc=Life and Writings: "Plotinus’ teacher, Ammonius Saccas"|p=webpage}}{{Sfn|Keyser|Scarborough|2018|p=847|loc=Plotinus and Neoplatonism: The Creation of a New Synthesis by Siorvanes}} All of the ''reliable'' information about Plotinus' life comes from a biography written by his student ] as an introduction to Plotinus' work the ''].''{{Sfn|Armstrong|1962|p=11|loc=Introduction}} In the ''Enneads'' Plotinus describes three fundamental ] principles: ] (τὸ ἕν) the first ];{{Sfn|Gerson|2020|p=289|loc=English Glossary of Important Terms}} ] (νοῦς) the second hypostasis;{{Sfn|Gerson|2020|p=287|loc=English Glossary of Important Terms}} and ] (ψυχή) the third{{Sfn|Gerson|2020|p=293|loc=English Glossary of Important Terms}} hypostasis.{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=9|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}}{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=20|loc=Platonist curricula and their influence by Tarrant}}{{Sfn|Gerson|2018b|loc=The Three Fundamental Principles of Plotinus’ Metaphysics: "The three basic principles of Plotinus’ metaphysics are called by him ‘the One’ (or, equivalently, ‘the Good’), Intellect, and Soul (see V 1; V 9.)."|p=webpage}} | |||

| Plotinus' ''Enneads'' contain a unified synthesis of nearly eight centuries of Greek philosophy, and explicitly mentions the philosophers: ], ] and the ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].{{Sfn|Gerson|1999|p=10|loc=Plotinus: The Platonic tradition and the foundation of Neoplatonism by Gatti translated by Gerson}} The ''Enneads'' passed on the Platonic tradition to centuries of ], ], and early-modern philosophers, and ] philosophy and religion,{{Sfn|Keyser|Scarborough|2018|p=864 (19 of 24 in Online Publication)|loc=Plotinus and Neoplatonism: The Creation of a New Synthesis, 6. Influence by Siorvanes.}} as well as having an enormous influence on art, poetry, and the nonacademic esoteric tradition.{{Sfn|Clark|2016|p=9|loc=Why Read Plotinus?}} | |||

| == Biography == | == Biography == | ||

| ] reported that Plotinus was 66 years old when he died in 270, the second year of the reign of the ] ], thus giving us the year of his teacher's birth as around 205. ] reported that Plotinus was born in Lyco, which could either refer to the modern ] in ] or ], in ].<ref name="Gerson 2017"/><ref name="Britannica"/><ref name="Stanford1"/><ref name="Siorvanes 2018"/> This has led to speculations that he may have been either native ], ] Egyptian,<ref>Bilolo, M.: ''La notion de « l’Un » dans les Ennéades de Plotin et dans les Hymnes thébains. Contribution à l’étude des sources égyptiennes du néo-platonisme.'' In: D. Kessler, R. Schulz (Eds.), "Gedenkschrift für Winfried Barta ''ḥtp dj n ḥzj''" (Münchner Ägyptologische Untersuchungen, Bd. 4), Frankfurt; Berlin; Bern; New York; Paris; Wien: Peter Lang, 1995, pp. 67–91.</ref> ],<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |last=Gerson |first=Lloyd P. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=359nRoAU4iEC |title=Plotinus |date=1999 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-0-415-20352-4 |pages=XII (12) |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Rist |first1=John M. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=n49OAAAAIAAJ |title=Plotinus: Road to Reality |last2=Rist |date=1967 |publisher=CUP Archive |isbn=978-0-521-06085-1 |pages=4 |language=en}}</ref> or ].<ref>"Plotinus." The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. ], 2003.</ref> Historian ] states that Plotinus was "almost certainly" a Greek.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| The neoplatonic philosopher ], a student and associate of Plotinus in the last six{{Sfn|Inge|1948a|p=114|loc=Forerunners of Plotinus}} or eight{{Sfn|Gerson|2010|p=xii|loc=Introduction}} years of his life, and his eventual biographer, says in his biographical work ''Life of Plotinus'' (''Vita Plotini'',{{Sfn|Remes|2008|p=19|loc=Introduction}} which is the most reliable authority for the life of Plotinus{{Sfn|Remes|2008|p=19|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Corrigan|2005|p=1|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1962|p=11|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Inge|1948a|p=114|loc=Forerunners of Plotinus}}) that Plotinus never talked about his family or his country to him; and so what we know of Plotinus' birthplace and nationality of his family is uncertain.{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=126|loc=Plotinus’ style and argument by Brisson}}{{Sfn|Inge|1948a|p=114|loc=Forerunners of Plotinus}} In ''Life of Plotinus'', Porphyry also reports that Plotinus did not reveal his birth date or birth month, but he knew Plotinus died in the 66th{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=vii|loc=Preface}}{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 2.34-2.35|ps=}}{{Sfn|MacKenna|1956|p=2|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Arrangement of his Work by Porphyry}} ''year of his life''{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=26|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} (i.e. after he was 65 and before he was 66 years old) at the end of the second year of the reign of the ] ] in 270 CE, hence giving us the year of Plotinus' birth as 204 or 205 CE.{{Sfn|Smith|1974|p=xi|loc=Introduction}} | |||

| Plotinus had an inherent distrust of materiality (an attitude common to ]), holding to the view that phenomena were a poor image or mimicry (]) of something "higher and intelligible" (VI.I) which was the "truer part of genuine Being". This distrust extended to the ], including his own; it is reported by Porphyry that at one point he refused to have his portrait painted, presumably for much the same reasons of dislike. Likewise, Plotinus never discussed his ancestry, childhood, or his place or date of birth.<ref name=":0" /> From all accounts his personal and social life exhibited the highest moral and spiritual standards. | |||

| === Birthplace === | |||

| According to the 5th century historian ], in his work ''Lives of Philosophers and Sophists,'' Plotinus was born in 'a place called Lyco'; however, that work was written in 455 CE,{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=4|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}} nearly two centuries after Plotinus died, and we do not know where Eunapius got his information from, as many possible sources have been lost,{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=12|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} or if his information is reliable.{{Sfn|Armstrong|1962|p=11 (and footnote 1)|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Inge|1948a|p=115|loc=Forerunners of Plotinus}} The ], a 10th-century ] encyclopedia, calls Plotinus 'a Lycopolitan', and the 11th century Byzantine empress ] says, in what may be her work ''Bed of Violets'',{{Sfn|Bigg|1895|pp=181-182|loc=Plotinus}} that 'some say he was born at Lyco, a ] of Lycopolis in Egypt'.{{Sfn|Inge|1948a|p=115|loc=Forerunners of Plotinus}} The ancient city of Lycopolis referred to by those reports is usually taken by scholars to be the modern day city ]{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=4|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}}{{Sfn|Clark|2016|p=3|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|MacKenna|Page|1952|p=v|loc=Biographical Note}} (Assiout,{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=126|loc=Plotinus’ style and argument by Brisson}} ancient Egyptian: ''Zawty{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=4|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}}'') which was the capital of the 13th nome of Upper Egypt situated between ] and ],{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=4|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}} and infrequently taken by scholars to be its colony ] in the Delta.{{Sfn|Clark|2016|p=3|loc=Introduction}} | |||

| Plotinus took up the study of ] at the age of twenty-eight, around the year 232, and travelled to ] to study.<ref name="Britannica"/><ref name="Stanford1"/><ref name="Siorvanes 2018"/> There he was dissatisfied with every teacher he encountered, until an acquaintance suggested he listen to the ideas of the ] Platonist philosopher ].<ref name="Britannica"/><ref name="Stanford1"/><ref name="Siorvanes 2018"/> Upon hearing Ammonius' lecture, Plotinus declared to his friend: "this is the man I was looking for",<ref name="Britannica"/> began to study intently under his new instructor, and remained with him as his student for eleven years.<ref name="Britannica"/><ref name="Stanford1"/><ref name="Siorvanes 2018"/> Besides Ammonius, Plotinus was also influenced by the philosophical works of ],<ref name="Gerson 2017"/> the ] philosophers ] and ],<ref name="Stamatellos 2007"/> the ] philosophers ] and ], along with various ]<ref name="Gerson 2017"/> and ].<ref name="Stamatellos 2007"/> | |||

| All those reports have led to speculations that Plotinus could have been a native Egyptian,{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|loc=Life, works and philosophical background|pp=11-12}} a ]{{Sfn|Gerson|1999|p=2|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=5|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}} Egyptian, a Greek or a Roman.{{Sfn|Gerson|2010|p=xii|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Rist|1967|p=4|loc=Introduction}} The speculation that Plotinus was Roman comes from the meagre{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=195|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}} conjecture{{Sfn|Inge|1948a|p=114|loc=Forerunners of Plotinus}} that the name 'Plotinus' is the male version of the name inherited from the 2nd century Roman empress ], whose husband was the Roman emperor ].{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=195|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1962|p=12|loc=Introduction}} Some late 19th century scholarship added to that speculation by saying that Plotinus may have been a ], descended from a ] of the empress.{{Sfn|Bigg|1895|pp=181-182|loc=Plotinus}} The eminent 21st century American-Canadian Plotinian scholar Professor ] relates, in his introduction to a 2010 publication, that Plotinus was 'likely a Greek', but he also says, in the following sentence, that it is possible that Plotinus 'came from a ] Egyptian or Roman family'.{{Sfn|Gerson|2010|p=xii|loc=Introduction}} | |||

| === Expedition to Persia and return to Rome === | |||

| === Alexandria === | |||

| After having spent eleven years in Alexandria, he then decided, at the age of around 38, to investigate the philosophical teachings of the ] and ].<ref name="Britannica"/><ref>Porphyry, ''On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books'', Ch. 3 (in Armstrong's Loeb translation, "he became eager to make acquaintance with the Persian philosophical discipline and that prevailing among the Indians").</ref> In the pursuit of this endeavor he left Alexandria and joined the army of the Roman emperor ] as it marched on ] (242-243 C.E.).<ref name="Britannica"/><ref name="Siorvanes 2018"/> However, ] was a failure, and on Gordian's eventual death Plotinus found himself abandoned in a hostile land, and only with difficulty found his way back to safety in ].<ref name="Britannica"/><ref name="Siorvanes 2018"/> | |||

| Despite his reluctance to talk about his own life, Plotinus did relate some details of his early life to ].{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 3.1-3.6}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=|loc=Porphyry on the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books|pp=8-9}}{{Sfn|MacKenna|1956|p=2|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Arrangement of his Work by Porphyry}} In 211 CE,{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=11|loc=Chronology}} when he was about six or seven years old, he was already under the instruction of a grammarian.{{Sfn|Guthrie|1918a|p=7|loc=Life of Plotinus and Order of his Writings by Porphyry}}{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: line 3.5}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=9|loc=Porphyry on the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books}} There is then a period of about 20 years, of which we know nothing,{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=27|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books: 3.6-3.13}} and our information about him continues from 231 CE,{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=11|loc=Chronology}} when he was about 27 years old, at which time he felt the impulse to study philosophy and was recommended to teachers of philosophy in ], who at that time were held in high esteem.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 3.6-3.8}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=9|loc=Porphyry on the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books|pp=}}{{Sfn|MacKenna|1956|p=2|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Arrangement of his Work by Porphyry}} | |||

| At the age of forty, during the reign of Emperor ], he came to ], where he stayed for most of the remainder of his life.<ref name="Britannica"/><ref name="Siorvanes 2018"/><ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Beauty and the mystic : Plotinus and Hawkins|last=Leete, Helen, 1938-|date=23 December 2016|isbn=9780987524836|location=Epping, N.S.W|oclc=967937243}}</ref> There he attracted a number of students. His innermost circle included ], ] of ], the Senator ], and ], a doctor who devoted himself to learning from Plotinus and attending to him until his death. Other students included: ], an ] by ancestry who died before Plotinus, leaving him a legacy and some land; ], a critic and poet; ], a doctor of ]; and ] from Alexandria. He had students amongst the ] beside Castricius, such as ], ], and ]. Women were also numbered amongst his students, including Gemina, in whose house he lived during his residence in Rome, and her daughter, also Gemina; and Amphiclea, the wife of Ariston the son of ].<ref>Porphyry, ''Vita Plotini'', 9. See also Emma C. Clarke, ], and Jackson P. Hershbell (1999), ''Iamblichus on The Mysteries'', page xix. SBL. who say that "to gain some credible chronology, one assumes that Ariston married Amphicleia some time after Plotinus's death"</ref> Finally, Plotinus was a correspondent of the philosopher ]. | |||

| In Alexandria, Plotinus attended philosophical lectures, but came away from those lectures sad and discouraged, and told a close friend, who understood his troubles and suggested that he attend a lecture by the Platonist{{Sfn|Gerson|2010a|p=284|loc=Origen by Prinzivalli}} philosopher ].{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 3.6-3.8}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=9|loc=Porphyry on the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books|pp=}}{{Sfn|MacKenna|1956|p=2|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Arrangement of his Work by Porphyry}} Ammonius is only partly{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=28|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books: 3.6-3.13}} known to us through the information in Porphyry's biography of Plotinus,{{Sfn|Dillon|1996|pp=281-282|loc=The Neopythagoreans}}{{Sfn|Smith|2004|p=4|loc=Part I: Setting the Agenda, The Philosophy of Plotinus, Introduction}} and at the time was teaching or had already taught Antoninus;{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=28|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books: 3.6-3.13}} Erennius (Herennius);{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=217|loc=III.B.1. The king}}{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=28|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books: 3.6-3.13}} ];{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=260|loc=III.B.8. Homeland and empire}}{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=28|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books: 3.6-3.13}} Olympius;{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=28|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books: 3.6-3.13}} ],{{Sfn|McGuckin|2004|p=5|loc=Life of Origen}}{{Sfn|Trigg|2002|p=12|loc=Introduction}} (who may have been another Origen known as ]);{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books|pp=9, 28, 32, 34, 61, 74}} and Theodosius.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=28|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books: 3.6-3.13}} In 231{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=31|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} or 232 CE,{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=ix|loc=Chronology}} after hearing a lecture by Ammonius, Plotinus declared to his friend: 'this is the man I was looking for', and after that day began studying under Ammonius, and remained his close associate for 11{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=31|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} years, by which time he was 38 years old.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 3.12-3.21}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=9|loc=Porphyry on the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books|pp=}}{{Sfn|MacKenna|1956|p=2|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Arrangement of his Work by Porphyry}} | |||

| === |

=== Later life === | ||

| While in Rome Plotinus also gained the respect of the Emperor ] and his wife ]. At one point Plotinus attempted to interest Gallienus in rebuilding an abandoned settlement in ], known as the 'City of Philosophers', where the inhabitants would live under the constitution set out in ]'s ''Laws''. An Imperial subsidy was never granted, for reasons unknown to Porphyry, who reports the incident. | |||

| After living about 11{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=31|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} years in Alexandria, and having made much progress in his study of philosophy, Plotinus decided to investigate the philosophical teachings of the ] and ],{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 3.15-3.22}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=9|loc=Porphyry on the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books|pp=}}{{Sfn|MacKenna|1956|p=2|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Arrangement of his Work by Porphyry}} (apparently the ]{{Sfn|Smith|2004|p=2|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Perl|2015|p=2|loc=Introduction to the Series}}).{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=ix|loc=Chronology}} In the pursuit of this endeavor, he left Alexandria and joined the army of the 18{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=127|loc=Plotinus’ style and argument by Brisson}} or 19{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=198|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}} year-old Roman emperor ] in 242{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=ix|loc=Chronology}} or 243 CE,{{Sfn|Garson|2010|p=xii|loc=Introduction}} as a philosopher and not a soldier.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=30|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}}{{Sfn|Remes|2008|p=19|loc=Introduction}} The army was headed to march against the great ]{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=10|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}} (king of kings) King Sapor{{Sfn|Harris|1982|p=287|loc=The Influence of Indian Philosophy on Neoplatonism by Tripathi}}{{Sfn|Inge|1948a|p=116|loc=Forerunners of Plotinus}} (]){{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=10|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}} of ]{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=194|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}} Persia.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 3.15-3.22}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=9|loc=Porphyry on the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books|pp=}}{{Sfn|MacKenna|1956|p=2|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Arrangement of his Work by Porphyry}} The ], founded in 224 CE, was particularly unreceptive to Graeco-Roman influences and held onto a rigid ] orthodoxy.{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=10|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}} It is conjectured that the religious teacher ] was in the Persian army headed by King Shapur I.{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=10|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}} | |||

| Plotinus subsequently went to live in ]. He spent his final days in seclusion on an estate in ] which his friend Zethos had bequeathed him. According to the account of Eustochius, who attended him at the end, Plotinus' final words were: "Try to raise the divine in yourselves to the divine in the all."<ref>Mark Edwards, ''Neoplatonic Saints: The Lives of Plotinus and Proclus by Their Students'', Liverpool University Press, 2000, p. 4 n. 20.</ref> Eustochius records that a snake crept under the bed where Plotinus lay, and slipped away through a hole in the wall; at the same moment the philosopher died. | |||

| Some scholars argue that Plotinus had connections with the Roman emperor Gordian III in order for him to be part of the expedition, however, other scholars think that Plotinus merely had to show up at the reception camp in Syria, and from there might have followed the Imperial army on its expedition to the East.{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=195|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}} Gordian's expedition didn't reach very far east,{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=11|loc=Life, works and philosophical background.}} as ] failed when Gordian III was killed in battle{{Sfn|Edwards|2000|p=xxxix|loc=Introduction}} in early 244 CE{{Sfn|Peachin|1990|pp=29-30|loc=Chronology}} (maybe assassinated by his own troops){{Sfn|Gerson|1999|p=3|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Inge|1948a|p=116|loc=Forerunners of Plotinus}} at a camp about 30km{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=202|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}} south of ] in a region named Zaitha{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=31|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}}{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=127|loc=Plotinus’ style and argument by Brisson}} (now the village al-Mar-wâniyya){{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=202|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}} in ].{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=11|loc=Life, works and philosophical background.}} Following those events, Plotinus with great difficulty found his way back to safety in ] (today the Turkish coast close to the Syrian border),{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=11|loc=Life, works and philosophical background.}} and soon afterwards moved to Rome.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 3.15-3.23}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=11|loc=Porphyry on the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books|pp=}}{{Sfn|MacKenna|1956|p=2|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Arrangement of his Work by Porphyry}} | |||

| Plotinus wrote the essays that became the '']'' (from Greek ἐννέα (''ennéa''), or group of nine) over a period of several years from c. 253 C.E. until a few months before his death seventeen years later. Porphyry makes note that the ''Enneads'', before being compiled and arranged by himself, were merely the enormous collection of notes and essays which Plotinus used in his lectures and debates, rather than a formal book. Plotinus was unable to revise his own work due to his poor eyesight, yet his writings required extensive editing, according to Porphyry: his master's handwriting was atrocious, he did not properly separate his words, and he cared little for niceties of spelling. Plotinus intensely disliked the editorial process, and turned the task to Porphyry, who not only polished them but put them into the arrangement we now have. | |||

| There had been a passionate attraction to the East among Greeks, with the idea of it being a source of great wisdom, since the age of ], ], ], and ].{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=29|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} The Eastern philosophies were also a great source of interest to ], ], ] and his son, , ], ], and many others.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=29|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} Hence it was not surprising that Plotinus was enthusiastic in his endeavours to travel to the East and learn about their philosophies.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=29|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} | |||

| == Major ideas == | |||

| At the age of 40, between 244{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=ix|loc=Chronology}}–245 CE,{{Sfn|Remes|2008|p=1|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Corrigan|2005|p=1|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|Gerson|1999|p=3|loc=Introduction}} Plotinus settled in Rome during the reign of emperor ], and stayed there until 269 CE,{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=ix|loc=Chronology}} when due to an illness,{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 2.15-2.20}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=5|loc=Porphyry on the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books|pp=}}{{Sfn|MacKenna|1956|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Arrangement of his Work by Porphyry|pp=|p=2}} and in what was to be the last months of his life, he moved to ], and there succumbed to his illness in 270 CE.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 3.15-3.35}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=|loc=Porphyry on the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books|pp=5, 7}}{{Sfn|MacKenna|1956|p=2|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Arrangement of his Work by Porphyry}} | |||

| === The One === | |||

| The move to Rome by Plotinus is surprising because, compared to Alexandria and Athens of the times, there was no important philosophical trend in that city.{{Sfn|Kalligus|2014|pp=32-33|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} Theories for Plotinus' move to Rome, related by the 21st century Professor Emeritus ], are that: (a) perhaps Plotinus' former teacher Ammonius had died in Alexandria in the meantime and Plotinus did not want to be the student of a different teacher; (b) Plotinus did not have a good relationship with the type of academicism in Athens, where at the time ]{{Sfn|Fleet|2012|p=2|loc=Introduction to the Series}} was the head of the ]; and (c) Plotinus had important acquaintances in Rome who could provide him with financial and political support, and introduce him to the Roman elite.{{Sfn|Kalligus|2014|pp=32-33|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} | |||

| {{See also|Substance theory}} | |||

| Plotinus taught that there is a supreme, totally transcendent "]", containing no division, multiplicity, or distinction; beyond all categories of ] and non-being. His "One" "cannot be any existing thing", nor is it merely the sum of all things (compare the ] doctrine of disbelief in non-material existence), but "is prior to all existents". Plotinus identified his "One" with the concept of 'Good' and the principle of 'Beauty'. (I.6.9) | |||

| His "One" concept encompassed thinker and object. Even the self-contemplating intelligence (the ] of the ]) must contain ]. "Once you have uttered 'The Good,' add no further thought: by any addition, and in proportion to that addition, you introduce a deficiency." (III.8.11) Plotinus denies ], self-awareness or any other action (''ergon'') to the One (τὸ Ἕν, ''to hen''; V.6.6). Rather, if we insist on describing it further, we must call the One a sheer potentiality ('']'') without which nothing could exist. (III.8.10) As Plotinus explains in both places and elsewhere (e.g. V.6.3), it is impossible for the One to be Being or a self-aware Creator God. At (V.6.4), Plotinus compared the One to "light", the Divine Intellect/] (Νοῦς, ''Nous''; first will towards Good) to the "Sun", and lastly the Soul (Ψυχή, '']'') to the "Moon" whose light is merely a "derivative conglomeration of light from the 'Sun'". The first light could exist without any celestial body. | |||

| ==== Plotinus' school ==== | |||

| In c. 245 CE, shortly after he had settled in Rome, Plotinus established the first neoplatonic school.{{Sfn|Remes|2008|p=1|loc=Introduction}} His school was open to everybody, and attracted people who just wanted to hear his lectures or attend meetings or seminars or participate in open philosophical discussions, whilst others came to seek a philosophical way of life, and others attended because they wanted to become philosophers.{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|pp=14-16|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} Plotinus did not impose a rigid curriculum at his school,{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=21|loc=Platonist Curricula and their Influence by Tarrant}} he himself did not write anything in his first 10 years in Rome, but rather based his seminars on Ammonius Saccas' teachings and encouraged students to ask questions and discuss subjects.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 3.33-3.38}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=11|loc=Porphyry on the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books}}{{Sfn|MacKenna|1956|p=3|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Arrangement of his Work by Porphyry}} Subjects of study at Plotinus' school included works by ] and ] and commentaries on Plato and Aristotle by the ], ] and ].{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|loc=Life, works and philosophical background|p=27}} In his biography of Plotinus, Porphyry does not say his listing of subjects studied at the school is exhaustive, and so there may have been other philosophical works that were read in Plotinus' school.{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|loc=Life, works and philosophical background|p=27}} | |||

| The One, being beyond all attributes including being and non-being, is the source of the world—but not through any act of creation, willful or otherwise, since activity cannot be ascribed to the unchangeable, immutable One. Plotinus argues instead that the multiple cannot exist without the simple. The "less perfect" must, of necessity, "emanate", or issue forth, from the "perfect" or "more perfect". Thus, all of "creation" emanates from the One in succeeding stages of lesser and lesser perfection. These stages are not temporally isolated, but occur throughout time as a constant process. | |||

| ==== Students ==== | |||

| Plotinus' students included philosophers, students of philosophy, doctors, Roman senators, poets and orators. His innermost circle of students were:{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=9|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}} | |||

| The One is not just an intellectual concept but something that can be experienced, an experience where one goes beyond all multiplicity.<ref>Stace, W. T. (1960) ''The Teachings of the Mystics'', New York, Signet, pp. 110–123</ref> Plotinus writes, "We ought not even to say that he will ''see'', but he will ''be'' that which he sees, if indeed it is possible any longer to distinguish between seer and seen, and not boldly to affirm that the two are one."<ref>Stace, W. T. (1960) ''The Teachings of the Mystics'', New York, Signet, p. 122</ref> | |||

| * ] of ] who joined Plotinus' school in 246–247 CE{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=12|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} and stayed for over 20{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=8|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} years until 268–269 CE.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 3.38-3.41, 7.1-7.5}} The industrious organization of Amelius contributed greatly to the success and longevity of Plotinus' school.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=36|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} Amelius was Plotinus' most important student, as he organized the school, wrote works and commentaries that analyzed Plotinus' philosophy, and defended Plotinus against critics and opponents.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=41|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} Amelius also thought highly of the philosopher ], whose works were read in Plotinus' circle,{{Sfn|Gerson|2010a|p=66|loc=Platonism before Plotinus by Tarrant}} and eventually went to live in a city substantively associated with Numenius,{{Sfn|Dillon|1996|p=361|loc=Numenius of Apamea}} the Syrian city of ], shortly before Plotinus died.{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=6|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}} When Plotinus was accused of appropriating Numenius' ideas, it was Amelius who wrote a book in Plotinus' defense called ''On the Difference between the Doctrines of Plotinus and Numenius''.{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=6|loc=The Philosophy of Plotinus the Egyptian}} | |||

| * ], a doctor who lived in Puteoli (modern day ], 40 miles outside Naples),{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=24|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} was a close friend of Plotinus, who came to the school near the end of Plotinus' life, devoted himself to learning from Plotinus, and attended him on his deathbed.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 1.13-1.14, 7.9}} After Plotinus' death, his uncorrected manuscripts belonged to Eustochius.{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=130|loc=Plotinus’ style and argument by Brisson}} Porphyry thought highly of Eustochius, who seems to have edited and published an edition of some{{Sfn|Gerson|1999|p=397|loc=Plotinus and Christian philosophy by Rist}}{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=88|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} of Plotinus' treatises, that were quoted by ] in ''Praeparatio Evangelica'',{{Sfn|Slaveva-Griffin|2009|p=134 (note 18)|loc=Unity of Thought and Writing}} but are now lost.{{Sfn|Gerson|2010|p=xii|loc=Introduction}} Eustochius' edition of Plotinus' treatise was published before Porphyry edited and published the ''Enneads'' about 30 years after Plotinus died.{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=365 (note 9)|loc=Neoplatonism and medicine by Wilberding}}{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=36 (note 8)|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} | |||

| * ], a student and associate of Plotinus from 262–263 CE{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=13|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} until he left the school in 268 CE.{{Sfn|Gerson|2010a|p=303|loc=Plotinus by O'Meara}} He was Plotinus' most brilliant student,{{Sfn|Evangeliou|1996|p=xi|loc=Prologue}} a close friend, his biographer, and who Plotinus asked to edit his writings,{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 7.50-7.52}} and eventually was the first{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=1|loc=General Introduction to the Translations}} editor of the ''],'' which was first published between 301–305 CE.{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989|p=ix|loc=Preface}} The neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry was amongst the first serious students of the ], and wrote on astrology,{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=445|loc=Freedom, providence and fate by Adamson}} religion, and philosophy, where he was a critic of ], ], ],{{Sfn|Berchman|2005|p=2|loc=Chapter 1: Author, Title, Date, Sources, Provenance}} and the school of his student, the neoplatonic philosopher ].{{Sfn|Magny|2014|p=8|loc=Introduction}} Porphyry also wrote on a important passage in ]'s '']'' in his work ''],'' and he wrote on Pythagorean musical theory.{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=21|loc=Platonist Curricula and their Influence by Tarrant}} | |||

| === Emanation by the One === | |||

| Superficially considered, Plotinus seems to offer an alternative to the orthodox ] notion of creation '']'' (out of nothing), although Plotinus never mentions Christianity in any of his works. The metaphysics of emanation (ἀπορροή ''aporrhoe'' (ΙΙ.3.2) or ἀπόρροια ''aporrhoia'' (II.3.11)), however, just like the metaphysics of Creation, confirms the absolute transcendence of the One or of the Divine, as the source of the Being of all things that yet remains transcendent of them in its own nature; the One is in no way affected or diminished by these emanations, just as the Christian God in no way is affected by some sort of exterior "nothingness". Plotinus, using a venerable analogy that would become crucial for the (largely neoplatonic) metaphysics of developed Christian thought, likens the One to the ] which emanates light indiscriminately without thereby diminishing itself, or reflection in a mirror which in no way diminishes or otherwise alters the object being reflected.<ref></ref> | |||

| The belief of the equality of men and women prevailed in ancient neoplatonic and Pythagorean schools.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=48|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} Among Plotinus' women students of philosophy{{Sfn|Guthrie|1918a|p=16|loc=Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Writings by Porphyry}} commented on by Porphyry in his biography of Plotinus, were: | |||

| The first emanation is '']'' (Divine Mind, '']'', Order, Thought, Reason), identified metaphorically with the ] in Plato's '']''. It is the first ] toward Good. From ''Nous'' proceeds the ], which Plotinus subdivides into upper and lower, identifying the lower aspect of Soul with ]. From the world soul proceeds individual ] souls, and finally, matter, at the lowest level of ] and thus the least ] level of the cosmos. Plotinus asserted the ultimately divine nature of material creation since it ultimately derives from the One, through the mediums of ''Nous'' and the world soul. It is by the Good or through beauty that we recognize the One, in material things and then in the ]. (I.6.6 and I.6.9) | |||

| * '''Amphiclea''', who was well versed in philosophy,{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=48|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} and whose husband was Ariston, who may{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=48|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}}{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=272|loc=III.B.9.a. Gender, sex and love}} have been the son of the neoplatonic philosopher ].{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 9.5-9.6}} | |||

| * '''Chione''', who lived in Gemina's house and may have employed the servants.{{Sfn|Edwards|2000|p=21 (footnote 117)|loc=On the Life of Plotinus}}{{Sfn|Guthrie|1918a|p=18|loc=Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Writings by Porphyry}} Porphyry mentions that Plotinus once helped in identifying the servant who had stolen a valuable necklace from her.{{Sfn|Edwards|2000|loc=On the Life of Plotinus|pp=21-22}}{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 11.1-11.7}} | |||

| * '''Gemina''', who also was well versed in philosophy,{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=15|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} and in whose spacious{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=48|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} house Plotinus lived while he was in Rome.{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|p=374|loc=Nature: Physics, Medicine and Biology by Corrigan|2014}} Her house was also home to the children of dying{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=48|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} or deceased{{Sfn|Gerson|2010|p=xii|loc=Introduction}}{{Sfn|O'Meara|1995|p=5|loc=Introduction}} nobility{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=197|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}} to whom Plotinus was an honorary guardian, one that supervised the actions of each guardian.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=48|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} One of his duties he undertook as an honorary guardian was to take meticulous care of the children's financial matters.{{Sfn|Katz|1950|p=ix|loc=Introduction}} He believed that until the children chose to become philosophers and renounce their wealth, their property and revenue should be kept intact and secure.{{Sfn|Bigg|1895|p=184|loc=Plotinus}} Gemina's house was also home to Chione and her children,{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 9.1-9.2}} and is likely to have been the venue for Plotinus' school.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=48|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} There has been a suggestion by the 20th–21st century French Professor ], in a 1992 publication, that Gemina was the widow of the Roman emperor ], whose full name was Afinia M. F. Gemina Baebiana.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=48|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} If that suggestion is true, it would further indicate Plotinus' connection to the elite of Roman society.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=48|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} | |||

| * '''Gemina''', Gemina's daughter, also called Gemina,{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 9.2-9.4}} who was greatly devoted to philosophy.{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=15|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} | |||

| 20th and 21st century scholars have debated, and are still debating whether the 'Sarcophagus of Plotinus',<ref>{{Cite web |date=12 October 2014 |title="Figures". The Enneads of Plotinus, Volume 1: A Commentary, Volume 1, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014, pp. 679-680. |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781400852512-011/pdf |url-status=live |access-date=21 July 2022 |website=De Gruyter |doi=10.1515/9781400852512-011}}</ref> dated c. 270 CE, depicts the younger Gemina and the elder Gemina at either side of a philosopher, where that philosopher maybe a depiction of Plotinus.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books, Appendix B: The Figural Representations of Plotinus|pp=94-95}} The sarcophagus also depicts another philosopher, that may be a depiction of Porphyry, looking over Plotinus' right shoulder.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books, Appendix B: The Figural Representations of Plotinus|pp=94-95}} The 'Sarcophagus of Plotinus' is located in the Gregorian Museum, one of the ].{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books, Appendix B: The Figural Representations of Plotinus|pp=94-95}} | |||

| The essentially devotional nature of Plotinus' philosophy may be further illustrated by his concept of attaining ecstatic union with the One ('']''). Porphyry relates that Plotinus attained such a union four times during the years he knew him. This may be related to ], realisation, liberation, and other concepts of ] common to many Eastern and Western traditions.<ref>{{cite book|last=Lander|first=Janis|title=Spiritual Art and Art Education|year=2013|publisher=Routledge|page= 76|isbn=9781134667895}}</ref> | |||

| ===== Doctors ===== | |||

| ]). Plotinus sometimes stayed with Zethus, his doctor and close friend, at his estate near Minturnae.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 7.21-7.23}}]] | |||

| Apart from Eustochius, Porphyry reports the following doctors were also students of Plotinus: | |||

| * ], a doctor from ] (a city also known as Bethshan,{{Sfn|Bigg|1895|p=188|loc=Plotinus}} or ]{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=261|loc=III.B.8. Homeland and empire}} on the West bank of the ]), who died shortly before Plotinus.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: line 7.6}} 19th century scholarship conjectures that he was Rabbi Mar Samuel (c. 180–257 CE), whom the ] relates had meetings and conversations with a famous non-Jewish teacher called Paltia (Plotinus?).{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=43|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} Porphyry relates that Paulinus was not the brightest of students.{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=365 (note 10)|loc=Neoplatonism and medicine by Wilberding}}{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 7.6-7.8}} | |||

| * ], a doctor and close friend of Plotinus, Porphyry and Amelius; was an ] by ancestry and who married the daughter of Theodosius, a student of Ammonius Saccas.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 7.15-7.28}} Plotinus sometimes stayed with him at his estate six{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=23|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} miles north of ] (modern day Minturno), which Castricius Firmus eventually bought.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 7.21-7.23}} Zethus died before Plotinus.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: line 1.19}} | |||

| ===== Roman senators ===== | |||

| Plotinus also had quite a few Roman senators who listened to his seminars, and some became his students, including: | |||

| * ], an influential person with a significant fortune, who may{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=128|loc=Plotinus’ style and argument by Brisson}} or may not{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=44|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} have been a Roman senator, and who supplied some of Plotinus' needs while he was gravely ill.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 1.21-1.23}} | |||

| * ], who diligently applied himself to the study of philosophy.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 7.29-7.30}} He was probably from near the ], and may have been the Marcellus whom ] addressed in a preface to a book that replied to the philosophies of Plotinus and Amelius.{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=196|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}} | |||

| * ''']''', who gave up all his possessions and the management of his house, dismissed his slaves, resigned his position, only ate every other day, which Porphyry says cured him from his debilitating gout, slept at various houses of his friends, and eventually became a member of Plotinus' inner circle of philosophers, and was praised publicly by Plotinus as a model to all others who wanted to become philosophers.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 7.30-7.45}} Before studying with Plotinus, Rogantianus may have been appointed praefect of the army on the Rhine in 241 CE and proconsul for Asia in 254 CE.{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=196|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}} | |||

| * ''']''', who also diligently applied himself to the study of philosophy.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 7.30-7.31}} Sabinillus may have been made an ordinary ] together with emperor ] in 266 CE.{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=196|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}} The 21st century Professor Emeritus ] thinks it is possible that Sabinillus was buried in a sarcophagus now located in the ] that came from ], which is in the region of ].{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books|pp=45-46}} | |||

| ===== Others ===== | |||

| Other listeners to Plotinus' seminars mentioned by Porphyry include: | |||

| * '''Carterius''', who was persuaded by Amelius to attend a seminar and secretly draw or paint a portrait of Plotinus without his knowledge.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 1.12-1.20}} He was a famous painter according to Porphyry, of whom nothing else is known apart from Porphyry's brief anecdote.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=21|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} | |||

| * ''']''', who at one time came to a seminar by Plotinus, however, after Plotinus saw Origen in the audience, Porphyry says Plotinus soon left <nowiki/>the seminar saying something along the lines 'that it was only natural for lecturers to cease talking when they were aware of the <nowiki/>presence, in the '''''<nowiki/>'''''a'''''<nowiki/>'''''udien'''''<nowiki/>'''''ce, of people who already knew what was to be said'.{{Sfn|Guthrie|1918a|p=21|loc=Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Writings by Porphyry}}{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 14.21-14.25}} | |||

| * ] of Alexander, who started as an orator, then turned to the study of philosophy, but did not stay long at the school as he was too interested in financial matters and money-lending.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 7.46-7.47}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=9|loc=Porphyry on the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books|pp=}} Other than the information in Porphyry's ''Life of Plotinus'', nothing else is known about Serapion.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books|pp=|p=46}} | |||

| * ], a critic and poet, who Porphyry says wrote a beautiful poem about Atlantis and also edited a work by ]. His eyesight failed and he died shortly before Plotinus.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 7.12-7.15}} | |||

| Porphyry also reports that he had correspondences with the philosopher ], who was the head of the ] in Athens,{{Sfn|Fleet|2012|p=2|loc=Introduction to the Series}} discussing Plotinus' philosophy, and Longinus wrote back saying he was very impressed by Plotinus' writings and wanted Porphyry to send him more works of Plotinus exactly transcribed.{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 19.1-19.40}} Plotinus however, was not very impressed by Longinus, as after he had heard a reading of Longinus' work ''On First Principles'',{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 14.15-14.21}} he remarked:<blockquote>"''Longinus is a literary man, but not a philosopher.''"—Plotinus{{Sfn|Guthrie|1918a|p=21|loc=Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Writings by Porphyry}}</blockquote> | |||

| ==== Elite Allies ==== | |||

| ], located in the ], Berlin. Plotinus was a close friend of Gallienus and his wife, the Roman empress ].{{Sfn|Armstrong|1962|p=13|loc=Introduction}}]] | |||

| While in Rome, Plotinus became a close friend of the mid 3rd century CE Roman emperor ] and his wife, the Roman empress ].{{Sfn|Armstrong|1962|p=13|loc=Introduction}} Although Plotinus' writings show no indication of activity or interest in political affairs, Porphyry reports that he nearly swayed emperor Gallienus, perhaps between 267–268 CE,{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=207|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}} to construct a city of philosophers in ], to be called Platonopolis, which was to be governed according to the doctrines in Plato's work '']''.{{Sfn|Armstrong|1962|p=14|loc=Introduction}} Most likely the planned city was to be in the Campanian provinces where Plotinus' friends already had estates, and realistically, Platonopolis was not only to be a city of philosophers, but a city that included all ranks of society.{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|loc=Coming to imperial Rome|pp=207-208}} Nothing came of the project, most likely due to the emperor's poor relationship with the Senate, despite some members of that body being supporters of Plotinus.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=55|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} | |||

| Late 20th and 21st century scholarship suggest there may be a possibility that Gemina, at whose house Plotinus stayed the entire time he was in Rome and whose house is likely to have been the venue for Plotinus' school,{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=48|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} was the widow of the Roman emperor ], whose full name was Afinia M. F. Gemina Baebiana, and who was the Roman emperor between 251–253 CE.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=48|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}}{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|loc=Coming to imperial Rome|pp=|p=196}} Emperor Gallus was an almost immediate predecessor to emperor ], Roman emperor from 253–260 CE, and Valerian's son, ], the Roman co-emperor with Valerian from 253–260 CE, and sole Roman emperor from 260 CE until 268 CE.{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|loc=Coming to imperial Rome|pp=|p=197}} Hence, it is suggested by some 21st century scholarship that Gemina, having close connections with the emperors Valerian and Gallienus, introduced Plotinus to emperor Gallienus and his wife, the empress Iulia Cornelia Salonina, who may have belonged to a Greek{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=54|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} family from ].{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|loc=Coming to imperial Rome|pp=|p=197}} The emperor Gallus and the empress Salonina who both, according to Porphyry,{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 12.1-12.2}} honoured and revered Plotinus visited Plotinus' school and probably participated in his classes at least once.{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|loc=III.C.1. The chair of Plotinus?|pp=|p=297}} | |||

| ==== Status ==== | |||

| Some 21st century scholarship argues that Plotinus was from a wealthy and cultivated family, likely high civil servants, who had strong connections with the Roman imperial court.{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=|loc=Plotinus’ style and argument by Brisson|pp=126-127}}{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=12|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}}{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|loc=Coming to Imperial Rome (references Professor Harder 1896-1957)|pp=|p=199}} These arguments are to some degree based on the observations by the mid-20th century German Professor ]{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|loc=Coming to Imperial Rome|pp=|p=195}} on Plotinus' later wealthy life in Rome, which were elaborated in detail during the 1980s by the French Professor ].{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|loc=Coming to Imperial Rome|pp=|p=195}} One such Indication of that wealth was that children of wealthy families were often handed over to a nursemaid from their birth,{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=126|loc=Plotinus’ style and argument by Brisson}} and this was the case with Plotinus, as reported by Porphyry in his biography.{{Sfn|Remes|Slaveva-Griffin|2014|p=126|loc=Plotinus’ style and argument by Brisson}}{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 3.2-3.6}} Another indication of his family's wealth was that by the time he was eight years old, he was under the instruction of a grammarian,{{Sfn|Guthrie|1918a|p=7|loc=Life of Plotinus and Order of his Writings by Porphyry}} as rhetoric was part of the normal curriculum for the educated elite.{{Sfn|Clark|2016|p=17|loc=How to Read Plotinus}} It is also clear that Plotinus' early teaching was in Greek, and he also wrote in Greek, a language, which since the time of ], was taught from a young age to the highest and best-educated Roman class.{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=33|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} | |||

| Other indications of Plotinus' family's wealth and strong connections with the Roman elite, substantially related by the Danish Dr. Asger Ousager in a 2005 publication,{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=|loc=Coming to imperial Rome|pp=195-199}} are that in Rome: he belonged to the upper-class{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=12|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} of society that was close to senators;{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=195|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}} he could afford masseurs;{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=195|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}}{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 2.5-2.10}} he spent summer vacations on wealthy estates in ],{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=195|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}}{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 5.1-5.5}} where the Roman upper class spent holidays;{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=195|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}} his doctor Eustochius was summoned from Puteoli (modern day ]), a seaside resort for the ultimate élite,{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=195|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}} to his deathbed in the villa of the wealthy estate of the deceased Zethus;{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=195|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}}{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 2.17-2.25, 7.17-7.23}} his circle of students included wealthy and influential people including Roman senators;{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=|loc=Coming to imperial Rome|pp=195-196}} and upon arriving in Rome he was soon lodging in Gemina's estate, who must have been relatively wealthy whether or not she was a former empress.{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|loc=Coming to imperial Rome|pp=195-199}} Further, dying Roman nobles let their children be raised at Gemina's house,{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=197|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}}{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 9.5-9.9}} where Plotinus was their tutor and guardian,{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=197|loc=Coming to imperial Rome}}{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 9.9-9.16}} implying that he was a very creditable person within the highest circles of Rome.{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=197|loc=Coming to imperial Rome|pp=}} Dr. Ousager relates that such a wealthy and honoured status afforded to Plotinus in Rome would be unlikely if his family was not in possession of wealth and honour beforehand.{{Sfn|Ousager|2005|p=197|loc=Coming to imperial Rome|pp=}} | |||

| ==== Writing style ==== | |||

| When Plotinus eventually wrote down his thoughts, beginning from 254 CE,{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=13|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} he would make sure the problems concerned were thoroughly debated beforehand in the school, and would not only take into consideration the opinions of Plato, Aristotle and the Stoics, but also consider the opinions of recent commentators and his students, before formulating his own opinion.{{Sfn|O'Meara|1995|p=10|loc=Introduction: Plotinus' Life and Works}} On the manner in which Plotinus wrote, Porphyry says that Plotinus would work out a train of thought from beginning to end, and then would write continuously and without hesitation, as if 'copying from a book', without worrying about his spelling or the beauty of his individual letters, as he was only concerned with ideas, which gives another reason as to why Plotinus' language is not easy to read.{{Sfn|Emilsson|2008|loc=Introduction|pp=1-2}}{{Sfn|Gerson|2018|p=|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books by Porphyry of Tyre: lines 8.3-8.11}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|1989a|p=29|loc=Porphyry on the Life of Plotinus and the Order of his Books}}{{Sfn|MacKenna|1956|p=7|loc=On the Life of Plotinus and the Arrangement of his Work by Porphyry}} | |||

| Despite the difficulty of his writing style, Plotinus is regarded by scholarship as having written some charming{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=17|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} and beautiful{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=17|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}}{{Sfn|Uždavinys|2009|p=viii|loc=Foreword by Bregman}}{{Sfn|Gerson|1999|p=349|loc=Plotinus and language by Schroeder}}{{Sfn|Whittaker|1918|p=39|loc=Plotinus and his Nearest Predecessors}} passages, and writes in a way that is agreeably personal and unaffected.{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=17|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} From his writings it is evident that he deeply cared and thought deeply about the issues on which he was writing, and it is easy to believe that his thoughts are being recorded as they occurred in his mind, unembellished and unedited, which leads too the conclusion that Plotinus' mind must have been quite orderly.{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=17|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} | |||

| ===== Enneads ===== | |||

| Plotinus began writing philosophical treatises from 254 CE{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=13|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} for a period of about 17 years until shortly before his death in 270 CE.{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=18|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} Porphyry, about 30 years after Plotinus died, edited and arranged Plotinus' treatises into 54 treatises, or six '']'' and gave them titles, which are still in use today, and wrote an introduction to the ''Enneads'' that was a biography of Plotinus' life called ''Life of Plotinus'' (''<span lang="la" dir="ltr">Vita Plotini</span>''{{Sfn|Remes|2008|p=19|loc=Introduction}}).{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|loc=Life, works and philosophical background|pp=18-19}} To Porphyry, the number 54 was significant for Pythagorean{{Sfn|Inge|1948a|p=119|loc=Forerunners of Plotinus}} numerological reasons (3<sup>3</sup> × 2, or 6 × 3<sup>2</sup>) and he had to split certain treatises to arrive at that number.{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=19|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} Plotinus had already written 21 treatises, beginning in 254 CE,{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=13|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} before Porphyry arrived at his school in 263 CE,{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=13|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} and he wrote 24 treatises while Porphyry was at his school, and wrote nine more after Porphyry left his school in 268{{Sfn|Kalligas|2014|p=14|loc=Porphyry: On the Life of Plotinus and the Order of His Books}} CE.{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=19|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} | |||

| Porphyry had a very difficult task in editing and arranging Plotinus' treatises into the ''Enneads'', as Plotinus, due to his failing eyesight, disliked writing and did not correct his works, which at times were composed in a hurry and amid constant interruptions.{{Sfn|Inge|1948a|p=119|loc=Forerunners of Plotinus}} However, Porphyry reports that Plotinus was capable of recording the orderly conceptions in his mind through his writings even when interrupted, as after the interruption he would resume his train of thought.{{Sfn|Remes|2008|p=21|loc=Introduction}} To add to the difficulty of Porphyry's editorial work, Plotinus' writing style, although being usually very structured,{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=17|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} is also very concise and requires constant effort from a reader,{{Sfn|Inge|1948a|p=119|loc=Forerunners of Plotinus}} with introductory and bridging remarks used sparingly.{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=17|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} | |||

| Plotinus' writings in the ''Enneads'' approach questions, and arguments for specific claims, from different angles and sometimes venture into related topics.{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=17|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} His powerful arguments are very concisely stated and are not spelled out with explicit premises, inferences and conclusions.{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=17|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} One of the major reasons why the ''Enneads'' is difficult to read is because it was not intended for publication, but was intended for circulation in Plotinus' school, and hence presupposed familiarity with subjects discussed in the school, and another reason is that Plotinus never attempts to explain his philosophy in a systematic manner.{{Sfn|Emilsson|2008|loc=Introduction|pp=1-2}} | |||

| ===== Influences ===== | |||

| Besides ], Plotinus, in his work ''Enneads'' (which contains everything he wrote),{{Sfn|Emilsson|2017|p=18|loc=Life, works and philosophical background}} was influenced by the philosophical works of: ], ] and the ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]; the ] of the 2nd century CE: Severus, ], ] and ] (a ] middle Platonist of the 2nd to 3rd century CE); and he was also influenced by the works of ].{{Sfn|Gerson|1999|p=|loc=Plotinus: The Platonic tradition and the foundation of Neoplatonism by Gatti translated by Gerson|pp=10, 13}} | |||

| === Later life === | |||