| Revision as of 21:58, 20 February 2023 editMucketymuck (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users5,481 edits These can be found in the work cited, including over a dozen windmills. Passage cleaned up and links added. I’ve changed “inventions and creations” to “designs and conceptions” because Veranzio (like da Vinci) seems seldom or never to have seen his innovative ideas through to use.← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:14, 20 February 2023 edit undoMucketymuck (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users5,481 edits →Veranzio's parachute: Passage simplified and edited for Misplaced Pages style.Next edit → | ||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

| ===Veranzio's parachute=== | ===Veranzio's parachute=== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| One of the illustrations in ''Machinae Novae'' is a sketch of a parachute dubbed ''Homo Volans'' ("The Flying Man"). Having examined ]'s rough ]es of a |

One of the illustrations in ''Machinae Novae'' is a sketch of a ] dubbed ''Homo Volans'' ("The Flying Man"). Having examined ]'s rough ]es of a parachute, Veranzio designed one of his own.<ref>, by ] in: '']'', Vol. 9, No. 3. (1968), pp. 462-467 (463)</ref><ref>Jonathan Bousfield, , pg. 280, Rough Guides (2003), {{ISBN|1-84353-084-8}}</ref> ] had already attempted to carry out the idea, ending by falling on a house roof and breaking his thigh bone (about 1590); but while ] was writing his flying romance ''The Man in the Moone'', Fausto Veranzio is widely believed to have performed an actual parachute-jumping experiment<ref>{{cite book|author=Francis Trevelyan Miller|title=The World in the Air: The Story of Flying in Pictures|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MdDNAAAAMAAJ|year=1930|publisher=G.P. Putnam's Sons|pages=101–106}}</ref> and, therefore, to be the first man to build and test a parachute. According to legend, Veranzio, in 1617, at over sixty-five years of age, implemented his parachute design and tested it by jumping from ] in Venice.<ref>{{cite book|author=Alfred Day Rathbone|title=He's in the paratroops now|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TM2EAAAAIAAJ|year=1943|publisher=R.M. McBride & Company}}</ref>{{page needed|date=February 2016}} This event was documented some 30 years later in the book '']'' (London, 1648), written by ], the secretary of the ] in London. | ||

| But in his book, where Wilkins wrote about flying and the possibility of human flight,<ref name="Magick">''Mathematical Magick'', second book, chapter VII</ref> methods of slowing down people's fall through the air were not his concern. His treatise does not even mention Veranzio by name, nor does it document any jump by parachute or any event at all in 1617.<ref name="Magick"/> No evidence has ever been found of any test of Veranzio's parachute. | |||

| ===Mills and wind turbines=== | ===Mills and wind turbines=== | ||

Revision as of 22:14, 20 February 2023

Venetian polymath and bishopThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Fausto Veranzio | |

|---|---|

| Faust Vrančić | |

Portrait of Faust Vrančić Portrait of Faust Vrančić | |

| Born | (1551-01-01)January 1, 1551 Sebenico, Republic of Venice |

| Died | 27 January 1617(1617-01-27) (aged 66) Venice, Republic of Venice |

| Known for | Polymath, bishop |

| Notable work | Machinae Novae, Dictionarium quinque nobilissimarum Europæ linguarum |

Fausto Veranzio (Template:Lang-la; Template:Lang-hr; Hungarian and Vernacular Latin: Verancsics Faustus; c. 1551 – 20 January 1617) was a polymath and bishop from Šibenik, then part of the Republic of Venice.

Life

Family history

Fausto was born in Sebenico (Šibenik), Venetian Dalmatia into the family of counts Vrančić (Veranzio) who came from Bosnia (a branch of which later merged with Draganić family, creating the Counts Draganić-Vrančić), a notable family of writers and Berislavić family.

He was the son of Michele Veranzio (Template:Lang-hr), a Latin poet, and the nephew of Antonio (Template:Lang-hr), archbishop of Esztergom (1504–1573), a diplomat and a civil servant, who was in touch with Erasmus (1465–1536), Philip Melanchthon (1497–1560), and Nikola IV Zrinski (1508–1566), who took Fausto with him during some of his travels through Hungary and in the Republic of Venice. Fausto's mother was from the Berislavić family. His brother, Giovanni (Template:Lang-hr), died still young in battle.

While the family's main residence was in city of Šibenik, they owned a big summer house on island of Prvić, in place Šepurine, a neighboring place to Prvić-Luka (where he is buried in local church). The Baroque castle that was used by Vrančić family as summer residence is now in possession of the Draganić family.

Education and political activities

As a youth, Veranzio was interested in science. Still a child, he moved to Venice, where he attended schools, and then to Padua to join the University, where he focused on law, physics, engineering and mechanics.

At the court of King Rudolf II, at the Hradčany castle in Prague, Veranzio was chancellor for Hungary and Transylvania often in contact with Johannes Kepler and Tycho Brahe. After his wife's death, Veranzio left for Hungary. In 1598, he got the title of bishop of Csanád (Episcŏpus Csanadiensis) in partibus (even though he never set foot in Csanád). In 1609, back in Venice, he joined the brotherhood of Paul of Tarsus (barnabites) and committed himself to the study of science. Veranzio died in 1617 in Venice and was buried in Dalmatia, near his family's countryhouse on the island of Prvić.

Polymath and inventor

Veranzio's masterwork, Machinae Novae (Venice 1615 or 1616), contained 49 large pictures depicting 56 different machines, other devices, and technical concepts.

Two variants of this work exist, one with the "Declaratio" in Latin and Italian, the other with the addition of three other languages. Only a few copies survived and they often do not present a complete text in all the five languages. This book was written in Italian, Spanish, French, and German. The tables represent a varied set of the projects, designs, and conceptions of the author. There Veranzio wrote about water and solar energy, offering depictions of clocks, including a "universal clock" (Plates 6–7), many types of mills, agricultural machinery, various types of bridges in various materials, machinery for clearing the sea, a dual sedan chair borne by a mule (Plate 47), special coaches, and Homo Volans (Plate 38), a forerunner of the parachute. His ideas included a float resembling a modern lifebuoy (Plate 39), boats with ingenious power mechanisms relying on water currents (Plates 40 and 41), and a rotary printer (Plate 46) intended to improve on the printing press.

Despite the extraordinary rarity of this book (because the author published it at his own expense, without a publisher, and had to stop printing for want of funds), the Machinae Novae was the work which mainly contributed to Veranzio's popularity around the world. His design pictures were even reprinted a few years later and published in China.

Veranzio's parachute

One of the illustrations in Machinae Novae is a sketch of a parachute dubbed Homo Volans ("The Flying Man"). Having examined Leonardo da Vinci's rough sketches of a parachute, Veranzio designed one of his own. Paolo Guidotti had already attempted to carry out the idea, ending by falling on a house roof and breaking his thigh bone (about 1590); but while Francis Godwin was writing his flying romance The Man in the Moone, Fausto Veranzio is widely believed to have performed an actual parachute-jumping experiment and, therefore, to be the first man to build and test a parachute. According to legend, Veranzio, in 1617, at over sixty-five years of age, implemented his parachute design and tested it by jumping from St Mark's Campanile in Venice. This event was documented some 30 years later in the book Mathematical Magick or, the Wonders that may be Performed by Mechanical Geometry (London, 1648), written by John Wilkins, the secretary of the Royal Society in London.

But in his book, where Wilkins wrote about flying and the possibility of human flight, methods of slowing down people's fall through the air were not his concern. His treatise does not even mention Veranzio by name, nor does it document any jump by parachute or any event at all in 1617. No evidence has ever been found of any test of Veranzio's parachute.

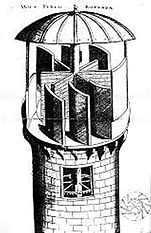

Mills and wind turbines

His areas of interest in engineering and mechanics were broad. Mills were one of his main point of research, where he created 18 different designs. He envisioned windmills with both vertical and horizontal axes, with different wing constructions to improve their efficiency. The idea of a mill powered by tides incorporated accumulation pools filled with water by the high tide and emptied when the tide ebbed, simply using gravity; the concept has just recently been engineered and used. The first wind turbines were described by Fausto Veranzio. In his book Machinae Novae (1616) he described vertical axis wind turbines with curved or V-shaped blades.

Urbanist and engineer in Rome and Venice

By order of the Pope, he spent two years in Rome where he envisioned and made projects needed for regulating rivers, since Rome was often flooded by the Tiber river. He also tackled the problem of the wells and water supply of Venice, which is surrounded by sea. Devices to register the time using water, fire, or other methods were envisioned and materialized. His own sun clock was effective in reading the time, date, and month, but functioned only in the middle of the day.

The construction method of building metal bridges and the mechanics of the forces in the area of statics were also part of his research. He drew proposals which predated the actual construction of modern suspension bridges and cable-stayed bridges by over two centuries. The last area was described when further developed in a separate book by mathematician Simon de Bruges (Simon Stevin) in 1586. Veranzio also designed the concept to modern tied-arch bridges, through arch bridges, truss bridges and aerial lifts.

-

Drawing of suspension cable-stayed bridge by Fausto Veranzio in his Machinae Novae

Drawing of suspension cable-stayed bridge by Fausto Veranzio in his Machinae Novae

-

Drawing of a suspension bridge by Fausto Veranzio (Machinae Novae)

Drawing of a suspension bridge by Fausto Veranzio (Machinae Novae)

-

Early design of a tied-arch/through arch bridge by Fausto Veranzio

Early design of a tied-arch/through arch bridge by Fausto Veranzio

-

Truss arch bridge by Fausto Veranzio

Truss arch bridge by Fausto Veranzio

-

Primitive design of an early truss bridge by Fausto Veranzio

Primitive design of an early truss bridge by Fausto Veranzio

-

Design for an aerial lift by Fausto Veranzio (Machinae Novae)

Design for an aerial lift by Fausto Veranzio (Machinae Novae)

Lexicography

Veranzio was the author of a five-language dictionary, Dictionarium quinque nobilissimarum Europæ linguarum, Latinæ, Italicæ, Germanicæ, Dalmatiæ, & Vngaricæ, published in Venice in 1595, with 5,000 entries for each language: Latin, Italian, German, the Dalmatian vernacular (in particular, the chakavian dialect of Croatian) and Hungarian. These he called the "five noblest European languages" ("quinque nobilissimarum Europæ linguarum").

The Dictionarium is a very early and significant example of both Croatian and Hungarian lexicography, and contains, in addition to the parallel list of vocabulary, other documentation of these two languages. In particular, Veranzio listed in the Dictionarium 304 Hungarian words that he deemed to be borrowed from Croatian. Also, at the end of the book, Veranzio included Croatian language versions of the Ten Commandments, the Lord's Prayer, the Ave Maria and the Apostles' Creed.

In an extension of the dictionary called Vocabula dalmatica quae Ungri sibi usurparunt, there is a list of Proto-Croatian words that entered the Hungarian language. The book greatly influenced the formation of both the Croatian and Hungarian orthography; the Hungarian language accepted his suggestions, for example, the usage of ly, ny, sz, and cz. It was also the first dictionary of the Hungarian language, printed four times, in Venice, Prague (1606), Pozun (1834), and in Zagreb (1971). The work was an important source of inspiration for other European dictionaries such as a Hungarian and Italian dictionary written by Bernardino Baldi, a German Thesaurus polyglottus by humanist and lexicographer Hieronymus Megiser, and multilingual Dictionarium septem diversarum linguarum by Peterus Lodereckerus of Prague in 1605.

History and philosophy

Only a few of Veranzio's works related to history remain: Regulae cancellariae regni Hungariae and De Slavinis seu Sarmatis in Dalmatia exist in manuscript form, while Scriptores rerum hungaricum was published in 1798. In Logica nova ("New logic") and Ethica christiana ("Christian ethics"), which were published in a single Venetian edition in 1616, Veranzio dealt with the problems of theology regarding the ideological clash between the Reformation movement and Catholicism. Tommaso Campanella (1568–1639) and the Archbishop of Split Marco Antonio de Dominis (1560–1624) were his intellectual counterparts.

Legacy

When Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951), Austrian-British philosopher and mathematician, moving from Berlin to England, began studying mechanical engineering in 1908, he was highly influenced by his reading of Renaissance technical treatises, particularly Veranzio's Machinae Novae.

The 17th century Brooklyn Tidal Mill in Long Island (NY), one of the most popular and few still standing mills in the New York City area, was built after the plan of Fausto Veranzio.

In 1965, "Faust Vrančić" Astronomy Society was founded in Šibenik.

In 1969, the medallion with his figure, work by Kosta Angeli Radovani, was embedded in the rector's chain of the University of Zagreb.

In 1992, the Croatian Parliament established the "Faust Vrančić" National Award for Technical Culture which is awarded to individuals, associations and other legal persons for outstanding achievements in technical culture.

In 1993, his bust was erected at the Nikola Tesla Technical Museum's Sculpture Garden of the Croatian Geniuses of Science and Technology.

In 2012, Faust Vrančić Memorial Centre was opened on the island of Prvić where visitors can learn more about Veranzio's life and see his most famous inventions.

Croatian Navy's rescue ship BS-73, as well as many schools and streets in Croatia, were named after him.

Cultural event Days of Faust Vrančić is held annually in Šibenik.

Works

- Machinae novae (in Latin). Venezia. 1615.

See also

Notes

- ^ Ivetic 2020.

- Eleonora Zuliani. "Veranzio, Fausto". Enciclopedia Italiana. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, Volume 7. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1983. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-852-29400-0.

- Andrew L. Simon, Made in Hungary: Hungarian contributions to universal culture

- The Hungarian Quarterly, Vol. XLII * No. 162 *, Summer 2001 Archived 2011-07-12 at the Wayback Machine László Sipka: Innovators and Innovations

- According to M. D. Grmek, Verantius, Faustus (also known as Faust Vrančić or Veranzio) he died on January 20, 1617.

- ^ Abbe Alberto Fortis (2007) . Travels Into Dalmatia. Cosimo, Inc. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-60520-046-0.

- C. W. Bracewell (1992). "The Uskoks of Senj". ISBN 0-8014-7709-3.

- John Fine (2006). "When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans: A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods". ISBN 047211414X.

- Gyurikovits György (1834). "Biographia Verantii in 'Verantius Dictionarium pentaglottum'".

- J.T. Marnavich (1617). "Oratio habita in funere ill. ac rev. viri Fausti".

- Thomas Blackwell; John Mills (1763). Memoirs of the Court of Augustus: Continued, and Completed, from the Original Papers of the Late Thomas Blackwell. A. Millar. p. 239.

- Beate Henn-Memmesheimer; David Gethin John (2003). Cultural Link Kanada, Deutschland: Festschrift zum dreissigjährigen Bestehen eines akademischen Austauschs. Röhrig Universitätsverlag. p. 115. ISBN 978-3-86110-355-4.

- Some friends thanked him for this book in 1616; the date of 1595 refers to the publication of his Dictionarium

- ^ Original Machine Novae, Fausto VERANZIO - Malavasi Library, Milan - a complete and very detailed description of first and second editions of Veranzio's most famous work, "Machine Nove"

- Ku, Wei-ying, ed. (2001). Missionary approaches and linguistics in mainland China and Taiwan. Leuven: Leuven University Press. p. 184. ISBN 9789058671615.

- "The Invention of the Parachute", by Lynn White, Jr. in: Technology and Culture, Vol. 9, No. 3. (1968), pp. 462-467 (463)

- Jonathan Bousfield, The Rough Guide to Croatia, pg. 280, Rough Guides (2003), ISBN 1-84353-084-8

- Francis Trevelyan Miller (1930). The World in the Air: The Story of Flying in Pictures. G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 101–106.

- Alfred Day Rathbone (1943). He's in the paratroops now. R.M. McBride & Company.

- ^ Mathematical Magick, second book, chapter VII

- ^ Biblioteca italiana, o sia giornale di letteratura, scienze ed arti ... 1829. p. 263.

- John Considine (27 March 2008). Dictionaries in Early Modern Europe: Lexicography and the Making of Heritage. Cambridge University Press. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-1-139-47105-3.

- Fausto Veranzio (1595). Dictionarium quinque nobilissimarum Europæ linguarum, Latinæ, Italicæ, Germanicæ, Dalmatiæ, & Vulgaricæ. Apud Nicolaum Morettum.

- ^ When Petrus Lodereckerus published in 1606 his Dictionarivm septem diversarvm lingvarvm, videlicet Latine, Italice, Dalmatice, Bohemicè, Polonicè, Germanicè, & Vngaricè, vna cum cuiuslibet linguæ registro siue repertorio vernaculo, Singulari studio & industria collectum a Petro Lodereckeroin (Prague), he included two more languages than Veranzio's pentadictionary: Czech and Polish, with the addition of indices in Latin for each language.

- Branko Franolić (1976). Was Faust Vrančić the First Croatian Lexicographer?. Istituto Universitario Orientale. pp. 178–182.

- Today Bratislava in Slovakia

- F. A. Flowers, Portraits of Wittgenstein, Volume 2, page 133

- ^ R. H. Charlier; Charles W. Finkl (8 February 2009). Ocean Energy: Tide and Tidal Power. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 38–. ISBN 978-3-540-77932-2.

- Bernard L. Gordon (September 1977). Energy from the sea: marine resource readings. Book & Tackle Shop. p. 119. ISBN 9780910258074.

- ISES Congress 2007 Nothing New Under the Sun or Every Little Bit Helps Tidal Power: Status & Perspectives R.H. Charlier, M.C.P. Chaineux, C.W. Finkl, A.C Thys, Vol. I–V, Springer

References

- Great machines Volume 69, Franz Engler, illustrated CIPIA, 1997 (University of Michigan) p. 4-14

- "Bridges and men", Joseph Gies, Doubleday, University of Michigan, 2009

- Aspects of Materials Handling Dr. K.C. Arora, Vikas V. Shinde - Firewall Media, 2007, ISBN 81-318-0251-5

- Instruments in art and science: on the architectonics of cultural boundaries Helmar Schramm, Ludger Schwarte, Jan Lazardzig - Literary Criticism, 2008

- Sugar and society in China: peasants, technology, and the world market S. Mazumdar - Harvard University Asia Center, Cambridge Mass. 1998, ISBN 0-674-85408-X,

- Engineering in history, Richard Shelton Kirby, Technology & Engineering, 1990

- Means and Methods Analysis of a Cast-In-Place Balanced Cantilever Segmental Bridge: Veranzio’s Machinae Novae Gunnar Lucko - Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 2000

- American building art: the nineteenth century, Carl W. Condit, OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS - page 163:

- The birth of modern science The making of Europe, P. Rossi, Wiley-Blackwell, 2001 ISBN 978-0-631-22711-3

- Water architecture in the lands of Syria: the water-wheels

- The Italian Achievement: An A-Z Over 1000 'Firsts' Achieved by Italians in Almost Every Aspect of Life Over the Last 1000 Years A. Baron Renaissance, 2008 University of California ISBN 978-1898823551

- History of Technology History of Technology, Graham Hollister-Short. A brief history of the technology through the centuries. The author is Honorary Lecteur of the Imperial College of London

- Charles Joseph Singer, A History of Technology, Charles Singer (British historian of science and medicine)

- Dizionario bibliografico degli uomini illustri della Dalmazia, Šime Ljubić (in Italian)

- Archibald Montgomery Low, Parachutes in peace and war, Archibald Low (English consulting engineer, research physicist and inventor, called "the father of the radio guidance systems"), 1942

- Medieval religion and technology: collection of essays (1978), Lynn Townsend, professor of medieval history at Princeton, Stanford and UCLA.

- Anthropological series, (vol. 18), Field Museum of Natural History, Field Columbian Museum.

- Technology and culture, Society for the History of Technology, vol. 9, 1968

- Design paradigms: case histories of error and judgment in engineering Henry Petroski CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS, 1994 ISBN 978-0-521-46649-3

- Technological concepts and mathematical models in the evolution of modern engineering systems: controlling, managing, organizing, Mario Lucertini, Ana Millán Gasc, F. Nicolò, Birkhäuser, 2004, ISBN 3-7643-6940-X

- Histoire des sciences mathématiques en Italie: depuis la renaissance des lettres jusqu'à la fin du dix-septième siècle Ghent University, 1848 (in French)

- Musei per la scienza - Science museums L.B.Peressut, Pub. Lybra imagine, (illustrated) 1998, ISBN 88-8223-033-3

- Fausto Veranzio - Innovatore (in Italian)

External links

- Ivetic, Egidio (2020). "VERANZIO, Fausto". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 98: Valeriani–Verra (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- aero.com

- Croatian scientists

- Croatian inventors

- Croatian engineers

- Croatian philosophers

- People from Šibenik

- 1551 births

- 1617 deaths

- Italian lexicographers

- Republic of Venice scientists

- Croatian lexicographers

- Venetian Renaissance humanists

- Croatian Renaissance humanists

- 16th-century Venetian writers

- 16th-century male writers

- 16th-century Croatian people

- Linguists from Croatia

- Sustainable transport pioneers

- University of Padua alumni

- Catholic clergy scientists

- 16th-century Latin-language writers

- 17th-century Latin-language writers

- History of Šibenik