| Revision as of 15:25, 19 April 2024 edit92.13.193.60 (talk) →Geography← Previous edit | Revision as of 12:00, 2 June 2024 edit undoMarcin 303 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users19,184 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

| {{Infobox settlement | {{Infobox settlement | ||

| | name = Wałbrzych | | name = Wałbrzych | ||

| |native name = {{native name|mis|paren=no|Wałbrzich}} (]) <br> {{native name|mis|paren=no|Walmbrig/Walmbrich}} (]) | |||

| | image_skyline = {{multiple image | | image_skyline = {{multiple image | ||

| | border = infobox | | border = infobox | ||

| Line 51: | Line 50: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

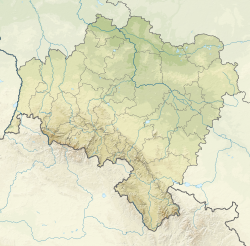

| '''Wałbrzych''' ({{IPA-pl|ˈvawbʐɨx|lang|Pl-Wałbrzych.ogg}}; {{lang-de|Waldenburg}}; {{lang-szl|Wałbrzich}}; {{lang-sli|label=]|Walmbrig}} or ''Walmbrich''; {{lang-cs|Valbřich}} or {{lang|cs|Valdenburk}}) is a city located in the ], in southwestern ] |

'''Wałbrzych''' ({{IPA-pl|ˈvawbʐɨx|lang|Pl-Wałbrzych.ogg}}; {{lang-de|Waldenburg}}; {{lang-szl|Wałbrzich}}; {{lang-sli|label=]|Walmbrig}} or ''Walmbrich''; {{lang-cs|Valbřich}} or {{lang|cs|Valdenburk}}) is a city located in the ], in southwestern ], seat of ]. Wałbrzych lies approximately {{convert|70|km|mi}} southwest of the voivodeship capital ] and about {{convert|30|km|abbr=off}} from the ] border. Wałbrzych has the status of municipality. Its administrative borders encompass an area of {{Convert|85|km2|abbr=on}} with 110,000 inhabitants,{{when|date=February 2023}} making it the second-largest city in the voivodeship and the 33rd largest in the country. | ||

| Wałbrzych was once a major ] and industrial center alongside most of ]. The city was left undamaged after ] and possesses rich historical architecture; among the most recognizable landmarks is the ], the largest castle of ] and the third-largest in Poland. | Wałbrzych was once a major ] and industrial center alongside most of ]. The city was left undamaged after ] and possesses rich historical architecture; among the most recognizable landmarks is the ], the largest castle of ] and the third-largest in Poland. | ||

| Line 59: | Line 58: | ||

| == Etymology == | == Etymology == | ||

| According to the city's official website, the earliest Polish name of the settlement was {{Lang|pl|Lasogród}} ('forest castle').<ref name="um.walbrzych.pl">{{cite web|url=http://www.um.walbrzych.pl/strony/nasze_miasto_poznaj_historia.htm|title=Portal Urzędu Miejskiego w Wałbrzychu|work=um.walbrzych.pl}}</ref> | According to the city's official website, the earliest Polish name of the settlement was {{Lang|pl|Lasogród}} ('forest castle').<ref name="um.walbrzych.pl">{{cite web|url=http://www.um.walbrzych.pl/strony/nasze_miasto_poznaj_historia.htm|title=Portal Urzędu Miejskiego w Wałbrzychu|work=um.walbrzych.pl}}</ref> | ||

| The German name is also the exact translation of the original Polish ‘forest castle’{{Lang|de|Waldenburg}} (also referred to the castle Nowy Dwór |

The German name is also the exact translation of the original Polish ‘forest castle’ {{Lang|de|Waldenburg}} (also referred to the castle Nowy Dwór, translated into German as: {{Lang|de|Burg Neuhaus}}), whose ruins stand south of the city; the name came to be used for the entire settlement.<ref name="Weczerka-555">Weczerka, p.555.</ref> It first appeared in the 15th century.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.poradniajezykowa.us.edu.pl/baza_archiwum.php?POZYCJA=120&AKCJA=&TEMAT=Etymologia&NZP=&WYRAZ= |title=Witamy w PORADNI JĘZYKOWEJ |work=us.edu.pl}}</ref> The modern Polish name Wałbrzych comes from the German name {{Lang|de|Walbrich}}, a late medieval variation of the older names {{Lang|de|Wallenberg}} or {{Lang|de|Walmberg}}.<ref name=czopek55>Barbara Czopek, ''Adaptacje niemieckich nazw miejscowych w języku polskim'', 1995, p.55, {{ISBN|83-85579-33-8}}</ref> | ||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| === Middle Ages === | === Middle Ages === | ||

| ]]]{{Historical populations|1950|93842|1960|117209|1970|125200|1980|133549|1990|141011|2000|131675|2010|120197|2020|109971|footnote=source <ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.polskawliczbach.pl/Walbrzych | title=Wałbrzych (Dolnośląskie) » mapy, nieruchomości, GUS, noclegi, szkoły, regon, atrakcje, kody pocztowe, wypadki drogowe, bezrobocie, wynagrodzenie, zarobki, tabele, edukacja, demografia }}</ref>}} | ]]] | ||

| {{Historical populations|1950|93842|1960|117209|1970|125200|1980|133549|1990|141011|2000|131675|2010|120197|2020|109971|footnote=source <ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.polskawliczbach.pl/Walbrzych | title=Wałbrzych (Dolnośląskie) » mapy, nieruchomości, GUS, noclegi, szkoły, regon, atrakcje, kody pocztowe, wypadki drogowe, bezrobocie, wynagrodzenie, zarobki, tabele, edukacja, demografia }}</ref>}} | |||

| Polish sources indicate the city's predecessor, Lasogród, was an early medieval ]<ref>Słownik geograficzno-krajoznawczy Polski Maria Irena Mileska 1994 page 781 Wydawn. Nauk. PWN, 1994</ref> whose inhabitants engaged in hunting, honey gathering, and later agriculture. Lasogród eventually developed into a defensive fort, the remains of which were destroyed in the 19th century during expansion of the city.<ref>{{cite web| title=Historia Wałbrzycha| url=http://www.um.walbrzych.pl/strony/nasze_miasto_poznaj_historia.htm|publisher=Wałbrzych City Office|access-date=2 April 2009}}</ref> However, some German sources say no archaeological or written records support notions of an early West Slavic or ] settlement nor the existence of a castle before the late 13th century.<ref>''Vorgeschichtliche Funde innerhalb des Stadtgebietes sind spärlich und zweifelhaft in der Deutung, so daß eine frühe Dauersiedlung nicht angenommen werden kann. Für die Existenz einer "Waldenburg" im Bereich der Altstadt gibt es keinerlei Anhaltspunkte.'' Weczerka, p.555</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Die Deutschen und der Osten: das versunkene Jahrtausend|author=Hermann Schreiber|publisher=Südwest Verlag|year= 1984|pages=143|language=de}}</ref> They also denounce the idea that during the Middle Ages the area of Wałbrzych was part of an unpopulated Silesian forest, known as the ].<ref>''Auch der Grenzwald spricht dagegen.'' Weczerka, pp.416 and 555</ref><ref>Badstübner, p.2.</ref><ref name="Petry-11">Petry, p.11.</ref> In April 2022, a coin hoard was discovered near Wałbrzych dating from the first half of the 13th century.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-04-21 |title=Bracteate treasure hoard found near Wałbrzych |url=https://www.heritagedaily.com/2022/04/bracteate-treasure-hoard-found-near-walbrzych/143376 |access-date=2022-04-29 |website=HeritageDaily - Archaeology News |language=en-US}}</ref> | Polish sources indicate the city's predecessor, Lasogród, was an early medieval ]<ref>Słownik geograficzno-krajoznawczy Polski Maria Irena Mileska 1994 page 781 Wydawn. Nauk. PWN, 1994</ref> whose inhabitants engaged in hunting, honey gathering, and later agriculture. Lasogród eventually developed into a defensive fort, the remains of which were destroyed in the 19th century during expansion of the city.<ref>{{cite web| title=Historia Wałbrzycha| url=http://www.um.walbrzych.pl/strony/nasze_miasto_poznaj_historia.htm|publisher=Wałbrzych City Office|access-date=2 April 2009}}</ref> However, some German sources say no archaeological or written records support notions of an early West Slavic or ] settlement nor the existence of a castle before the late 13th century.<ref>''Vorgeschichtliche Funde innerhalb des Stadtgebietes sind spärlich und zweifelhaft in der Deutung, so daß eine frühe Dauersiedlung nicht angenommen werden kann. Für die Existenz einer "Waldenburg" im Bereich der Altstadt gibt es keinerlei Anhaltspunkte.'' Weczerka, p.555</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Die Deutschen und der Osten: das versunkene Jahrtausend|author=Hermann Schreiber|publisher=Südwest Verlag|year= 1984|pages=143|language=de}}</ref> They also denounce the idea that during the Middle Ages the area of Wałbrzych was part of an unpopulated Silesian forest, known as the ].<ref>''Auch der Grenzwald spricht dagegen.'' Weczerka, pp.416 and 555</ref><ref>Badstübner, p.2.</ref><ref name="Petry-11">Petry, p.11.</ref> In April 2022, a coin hoard was discovered near Wałbrzych dating from the first half of the 13th century.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-04-21 |title=Bracteate treasure hoard found near Wałbrzych |url=https://www.heritagedaily.com/2022/04/bracteate-treasure-hoard-found-near-walbrzych/143376 |access-date=2022-04-29 |website=HeritageDaily - Archaeology News |language=en-US}}</ref> | ||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

| He places the city near Nowy Dwór ({{lang-de|link=no|Neuhaus}}), built by ] of the ].<ref name="Weczerka-555" /> The city website, however, cites the building of the castle as a separate event in 1290.<ref name="um.walbrzych.pl"/> A part of Nowy Dwór castle, a manor built in the 17th century, was destroyed in the 19th century.<ref>Weczerka, p.341.</ref> Nevertheless, the region became part of Poland after the establishment of the state under the ] in the 10th century and during the ], it was part of various Polish-ruled duchies, the last of which was the Duchy of ]<ref name=um>{{cite web|url=https://www.um.walbrzych.pl/pl/page/historia|title=Historia|website=Portal Urzędu Miejskiego w Wałbrzychu|access-date=7 March 2020|language=pl}}</ref> until 1392, later it was also part of the ] and ]. | He places the city near Nowy Dwór ({{lang-de|link=no|Neuhaus}}), built by ] of the ].<ref name="Weczerka-555" /> The city website, however, cites the building of the castle as a separate event in 1290.<ref name="um.walbrzych.pl"/> A part of Nowy Dwór castle, a manor built in the 17th century, was destroyed in the 19th century.<ref>Weczerka, p.341.</ref> Nevertheless, the region became part of Poland after the establishment of the state under the ] in the 10th century and during the ], it was part of various Polish-ruled duchies, the last of which was the Duchy of ]<ref name=um>{{cite web|url=https://www.um.walbrzych.pl/pl/page/historia|title=Historia|website=Portal Urzędu Miejskiego w Wałbrzychu|access-date=7 March 2020|language=pl}}</ref> until 1392, later it was also part of the ] and ]. | ||

| The settlement was first mentioned as a town in 1426, but it did not receive the rights to hold markets or other privileges due to the competition of nearby towns and the insignificance of the local landlords. Subsequently, the city became the property of the Silesian knightly families, initially the ]es in 1372, later the Czettritzes, and from 1738, the ] family, owners of ]. | The settlement was first mentioned as a town in 1426, but it did not receive the rights to hold markets or other privileges due to the competition of nearby towns and the insignificance of the local landlords. Subsequently, the city became the property of the Silesian knightly families, initially the ]es in 1372, later the Czettritzes, and from 1738, the ] family, owners of ]. | ||

| === Modern era === | === Modern era === | ||

| ] Castle]] | ] Castle]] | ||

| ] in the area was first mentioned in 1536. The settlement was transformed into an industrial centre at the turn of the 19th century, when coal mining and ] flourished. | ] in the area was first mentioned in 1536. The settlement was transformed into an industrial centre at the turn of the 19th century, when coal mining and ] flourished. | ||

| As a result of the ] the city was annexed by the ] in 1742, and subsequently became part of Germany in 1871. In 1843 the city obtained its first rail connection, which linked it with ] (now ], Poland). In the early 20th century a glassworks and a large ] tableware manufacturing plant, which are still in operation today, were built. During ], the Germans operated three forced labour camps for ] ] in the city.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Kujat|first=Janusz Adam|year=2000|title=Pieniądz zastępczy w obozach jenieckich na terenie rejencji wrocławskiej w czasie I i II wojny światowej|journal=Łambinowicki rocznik muzealny|location=Opole|language=pl|volume=23|page=13|issn=0137-5199}}</ref> In 1939 the city had about 65,000 inhabitants. During ], the Germans established and operated labour units for ] from the ] ],<ref>{{cite journal|last=Sula|first=Dorota|year=2010|title=Jeńcy włoscy na Dolnym Śląsku w czasie II wojny światowej|journal=Łambinowicki rocznik muzealny|location=]|language=pl|volume=33|page=66}}</ref> a ] subcamp of the ] prisoner-of-war camp,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.lamsdorf.com/working-parties.html|title=Working Parties|website=Lamsdorf.com|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201029103834/https://www.lamsdorf.com/working-parties.html|access-date=7 November 2021|archive-date=29 October 2020}}</ref> a forced labour camp for ] men and women,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/haftstaetten/index.php?action=2.2&tab=7&id=100000976|title=Zwangsarbeitslager für Juden Waldenburg|website=Bundesarchiv.de|access-date=7 November 2021|language=de}}</ref> two ] of the ], intended for Jews, located in the present Gaj and Książ districts,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://en.gross-rosen.eu/historia-kl-gross-rosen/filie-obozu-gross-rosen/|title=Subcamps of KL Gross- Rosen|website=Gross-Rosen Museum in Rogoźnica|access-date=7 March 2020}}</ref> and a Nazi prison.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/haftstaetten/index.php?action=2.2&tab=7&id=100000975|title=Gerichtsgefängnis Waldenburg|website=Bundesarchiv.de|access-date=7 November 2021|language=de}}</ref> It was conquered by the Soviet ] on 8 May 1945 – coincidentally, the day ]. | As a result of the ] the city was annexed by the ] in 1742, and subsequently became part of Germany in 1871. In 1843 the city obtained its first rail connection, which linked it with ] (now ], Poland). In the early 20th century a glassworks and a large ] tableware manufacturing plant, which are still in operation today, were built. During ], the Germans operated three forced labour camps for ] ] in the city.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Kujat|first=Janusz Adam|year=2000|title=Pieniądz zastępczy w obozach jenieckich na terenie rejencji wrocławskiej w czasie I i II wojny światowej|journal=Łambinowicki rocznik muzealny|location=Opole|language=pl|volume=23|page=13|issn=0137-5199}}</ref> In 1939 the city had about 65,000 inhabitants. During ], the Germans established and operated labour units for ] from the ] ],<ref>{{cite journal|last=Sula|first=Dorota|year=2010|title=Jeńcy włoscy na Dolnym Śląsku w czasie II wojny światowej|journal=Łambinowicki rocznik muzealny|location=]|language=pl|volume=33|page=66}}</ref> a ] subcamp of the ] prisoner-of-war camp,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.lamsdorf.com/working-parties.html|title=Working Parties|website=Lamsdorf.com|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201029103834/https://www.lamsdorf.com/working-parties.html|access-date=7 November 2021|archive-date=29 October 2020}}</ref> a forced labour camp for ] men and women,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/haftstaetten/index.php?action=2.2&tab=7&id=100000976|title=Zwangsarbeitslager für Juden Waldenburg|website=Bundesarchiv.de|access-date=7 November 2021|language=de}}</ref> two ] of the ], intended for Jews, located in the present Gaj and Książ districts,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://en.gross-rosen.eu/historia-kl-gross-rosen/filie-obozu-gross-rosen/|title=Subcamps of KL Gross- Rosen|website=Gross-Rosen Museum in Rogoźnica|access-date=7 March 2020}}</ref> and a Nazi prison.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/haftstaetten/index.php?action=2.2&tab=7&id=100000975|title=Gerichtsgefängnis Waldenburg|website=Bundesarchiv.de|access-date=7 November 2021|language=de}}</ref> It was conquered by the Soviet ] on 8 May 1945 – coincidentally, the day ]. | ||

| ]]] | |||

| After ], Waldenburg became again part of Poland under border changes demanded by the ] at the ] and was renamed to its historic Polish name<ref>Polski Kalendarz Katolicki dla Kochanych Wiarusów Prus Zachodnich page 77 http://www.wbc.poznan.pl/dlibra/docmetadata?id=259791&from=&dirids=1&ver_id=&lp=2&QI=</ref><ref>Katalog Prowincyonalnej wystawy przemysłowej w Poznaniu 1895 page 71 Werbebeilage http://www.wbc.poznan.pl/dlibra/docmetadata?id=130018&from=&dirids=1&ver_id=&lp=7&QI=</ref> Wałbrzych. Many of the Germans living in the city ] in accordance to the ]. The town was repopulated by ] |

After ], Waldenburg became again part of Poland under border changes demanded by the ] at the ] and was renamed to its historic Polish name<ref>Polski Kalendarz Katolicki dla Kochanych Wiarusów Prus Zachodnich page 77 http://www.wbc.poznan.pl/dlibra/docmetadata?id=259791&from=&dirids=1&ver_id=&lp=2&QI=</ref><ref>Katalog Prowincyonalnej wystawy przemysłowej w Poznaniu 1895 page 71 Werbebeilage http://www.wbc.poznan.pl/dlibra/docmetadata?id=130018&from=&dirids=1&ver_id=&lp=7&QI=</ref> Wałbrzych. Many of the Germans living in the city ] in accordance to the ]. The town was repopulated by ] expelled from ], particularly from ], ] and ], as well as Poles returning from ] and ] and from ] in Germany.<ref name=um/> Wałbrzych was one of the few areas where a number of Germans<ref>Werner Besch, ''Dialektologie: Ein Handbuch zur Deutschen und allgemeinen Dialektforschung'', Walter de Gruyter, 1982, p.178, {{ISBN|3-11-005977-0}}</ref> were held back as they were deemed indispensable for the economy, e.g. coal mining.<ref name="wolff79">Stefan Wolff, '']'', Berghahn Books, 2000, p.79, {{ISBN|1-57181-504-X}}</ref> Also ], refugees of the ], settled in Wałbrzych in the 1950s.<ref>{{cite book|last=Kubasiewicz|first=Izabela|editor-last1=Dworaczek|editor-first1=Kamil|editor-last2=Kamiński|editor-first2=Łukasz|year=2013|title=Letnia Szkoła Historii Najnowszej 2012. Referaty|language=pl|location=Warszawa|publisher=]|pages=117|chapter=Emigranci z Grecji w Polsce Ludowej. Wybrane aspekty z życia mniejszości}}</ref> | ||

| After the ], remaining Germans were treated less harshly and an ethnic German society was established in 1957.<ref name=wolff79 /> The cultural activities however disappeared by the 1960s and the schools with German as the language of instruction gradually closed. The remaining German-speakers had little contact with the German spoken and written language and the local German-Silesian dialect became ].<ref> {{cite journal|work=Sprachwissenschaft und Daf|doi=10.18778/2196-8403.2018.08|author=Katarzyna Dulat-Lewicz|title=Wie stirbt eine Sprache aus? Überlegungen zu sozialpolitischen, wirtschaftlichen und kulturellen Faktoren des Sprachtodes am Beispiel der deutsch-schlesischen Varietät aus dem ehemaligen Kreis Waldenburg (powiat wałbrzyski)|doi-access=free|hdl=11089/30886|hdl-access=free}}</ref> | After the ], remaining Germans were treated less harshly and an ethnic German society was established in 1957.<ref name=wolff79 /> The cultural activities however disappeared by the 1960s and the schools with German as the language of instruction gradually closed. The remaining German-speakers had little contact with the German spoken and written language and the local German-Silesian dialect became ].<ref> {{cite journal|work=Sprachwissenschaft und Daf|doi=10.18778/2196-8403.2018.08|author=Katarzyna Dulat-Lewicz|title=Wie stirbt eine Sprache aus? Überlegungen zu sozialpolitischen, wirtschaftlichen und kulturellen Faktoren des Sprachtodes am Beispiel der deutsch-schlesischen Varietät aus dem ehemaligen Kreis Waldenburg (powiat wałbrzyski)|doi-access=free|hdl=11089/30886|hdl-access=free}}</ref> | ||

| The city was relatively unscathed by the Second World War, and as a result of combining the nearby administrative districts with the town and the construction of new housing estates, Wałbrzych expanded geographically. At the beginning of the 1990s, because of new social and economic conditions, a decision was made to close down the town's coal mines. In 1995, a Museum of Industry and Technology was ] in the area, KWK THOREZ. The 2005 the film '']'' was filmed in and around Wałbrzych. | The city was relatively unscathed by the Second World War, and as a result of combining the nearby administrative districts with the town and the construction of new housing estates, Wałbrzych expanded geographically. From 1975 to 1998 it was the capital of ]. At the beginning of the 1990s, because of new social and economic conditions, a decision was made to close down the town's coal mines. In 1995, a Museum of Industry and Technology was ] in the area, KWK THOREZ. The 2005 the film '']'' was filmed in and around Wałbrzych. | ||

| == Geography == | == Geography == | ||

| Line 91: | Line 92: | ||

| | direction = vertical | | direction = vertical | ||

| | caption1 = An observation tower and a tourist shed on Mount Borowa | | caption1 = An observation tower and a tourist shed on Mount Borowa | ||

| | total_width = |

| total_width = 230 | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| Wałbrzych is located in the Central ], near the border with the Czech Republic and Germany. The city is located by the Pełcznica River at 450–500 m above sea level in a picturesque structural basin of Wałbrzych above which there are wooded ranges of the ]. The highest elevation in the city is Mount Borowa, also known as the Black Mountain, 853 m (2798 ft) ], with an ] since 2007, which is the highest peak of the Wałbrzych mountains.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |title=Wałbrzych - location |url=https://um.walbrzych.pl/en/page/walbrzych-location |access-date=2022-08-31 |website=Oficjalny Serwis Miasta Wałbrzycha}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Borowa Tower – Jedlina-Zdrój – Poland |url=https://tropter.com/en/poland/jedlina-zdroj/borowa-tower |access-date=2022-08-31 |website=tropter.com |language=en}}</ref> | Wałbrzych is located in the Central ], near the border with the Czech Republic and Germany. The city is located by the Pełcznica River at 450–500 m above sea level in a picturesque structural basin of Wałbrzych above which there are wooded ranges of the ]. The highest elevation in the city is Mount Borowa, also known as the Black Mountain, 853 m (2798 ft) ], with an ] since 2007, which is the highest peak of the Wałbrzych mountains.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |title=Wałbrzych - location |url=https://um.walbrzych.pl/en/page/walbrzych-location |access-date=2022-08-31 |website=Oficjalny Serwis Miasta Wałbrzycha}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Borowa Tower – Jedlina-Zdrój – Poland |url=https://tropter.com/en/poland/jedlina-zdroj/borowa-tower |access-date=2022-08-31 |website=tropter.com |language=en}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 12:00, 2 June 2024

City in Lower Silesian Voivodeship, PolandPlace in Lower Silesian Voivodeship, Poland

| Wałbrzych | |

|---|---|

| |

Flag Flag Coat of arms Coat of arms | |

| |

| Coordinates: 50°46′N 16°17′E / 50.767°N 16.283°E / 50.767; 16.283 | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | |

| County | city county |

| Established | 9th century |

| City rights | 1400 to 1426 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Roman Szełemej (KO) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 84.70 km (32.70 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 350 m (1,150 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 108,222 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 58-300 to 58-309, 58-316 |

| Area code | +48 74 |

| Car number plates | DB, DBA |

| Website | www |

Wałbrzych (Polish: [ˈvawbʐɨx] ; Template:Lang-de; Template:Lang-szl; Template:Lang-sli or Walmbrich; Template:Lang-cs or Valdenburk) is a city located in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship, in southwestern Poland, seat of Wałbrzych County. Wałbrzych lies approximately 70 kilometres (43 mi) southwest of the voivodeship capital Wrocław and about 30 kilometres (19 miles) from the Czech border. Wałbrzych has the status of municipality. Its administrative borders encompass an area of 85 km (33 sq mi) with 110,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the voivodeship and the 33rd largest in the country.

Wałbrzych was once a major coal mining and industrial center alongside most of Silesia. The city was left undamaged after World War II and possesses rich historical architecture; among the most recognizable landmarks is the Książ Castle, the largest castle of Lower Silesia and the third-largest in Poland.

In 2015 Wałbrzych became widely known due to the search for an allegedly buried Nazi gold train, which however was not found.

Etymology

According to the city's official website, the earliest Polish name of the settlement was Lasogród ('forest castle'). The German name is also the exact translation of the original Polish ‘forest castle’ Waldenburg (also referred to the castle Nowy Dwór, translated into German as: Burg Neuhaus), whose ruins stand south of the city; the name came to be used for the entire settlement. It first appeared in the 15th century. The modern Polish name Wałbrzych comes from the German name Walbrich, a late medieval variation of the older names Wallenberg or Walmberg.

History

Middle Ages

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 93,842 | — |

| 1960 | 117,209 | +24.9% |

| 1970 | 125,200 | +6.8% |

| 1980 | 133,549 | +6.7% |

| 1990 | 141,011 | +5.6% |

| 2000 | 131,675 | −6.6% |

| 2010 | 120,197 | −8.7% |

| 2020 | 109,971 | −8.5% |

| source | ||

Polish sources indicate the city's predecessor, Lasogród, was an early medieval Slavic settlement whose inhabitants engaged in hunting, honey gathering, and later agriculture. Lasogród eventually developed into a defensive fort, the remains of which were destroyed in the 19th century during expansion of the city. However, some German sources say no archaeological or written records support notions of an early West Slavic or Lechitic settlement nor the existence of a castle before the late 13th century. They also denounce the idea that during the Middle Ages the area of Wałbrzych was part of an unpopulated Silesian forest, known as the Silesian Przesieka. In April 2022, a coin hoard was discovered near Wałbrzych dating from the first half of the 13th century.

According to 17th-century Polish historian Ephraim Naso, Wałbrzych was a small village by 1191. This assertion was rejected by 19th-century German sources and by German historian Hugo Weczerka, who says the city was founded between 1290 and 1293, and was mentioned as Waldenberc in 1305. He places the city near Nowy Dwór (Template:Lang-de), built by Bolko I the Strict of the Silesian Piasts. The city website, however, cites the building of the castle as a separate event in 1290. A part of Nowy Dwór castle, a manor built in the 17th century, was destroyed in the 19th century. Nevertheless, the region became part of Poland after the establishment of the state under the Piast dynasty in the 10th century and during the fragmentation of the realm, it was part of various Polish-ruled duchies, the last of which was the Duchy of Świdnica until 1392, later it was also part of the Bohemian Crown and Hungary.

The settlement was first mentioned as a town in 1426, but it did not receive the rights to hold markets or other privileges due to the competition of nearby towns and the insignificance of the local landlords. Subsequently, the city became the property of the Silesian knightly families, initially the Schaffgotsches in 1372, later the Czettritzes, and from 1738, the Hochberg family, owners of Książ Castle.

Modern era

Coal mining in the area was first mentioned in 1536. The settlement was transformed into an industrial centre at the turn of the 19th century, when coal mining and weaving flourished.

As a result of the First Silesian War the city was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia in 1742, and subsequently became part of Germany in 1871. In 1843 the city obtained its first rail connection, which linked it with Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland). In the early 20th century a glassworks and a large china tableware manufacturing plant, which are still in operation today, were built. During World War I, the Germans operated three forced labour camps for Allied prisoners of war in the city. In 1939 the city had about 65,000 inhabitants. During World War II, the Germans established and operated labour units for Italians from the Stalag VIII-A prisoner-of-war camp, a forced labour subcamp of the Stalag VIII-B/344 prisoner-of-war camp, a forced labour camp for Jewish men and women, two subcamps of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, intended for Jews, located in the present Gaj and Książ districts, and a Nazi prison. It was conquered by the Soviet Red Army on 8 May 1945 – coincidentally, the day World War II in Europe ended.

After World War II, Waldenburg became again part of Poland under border changes demanded by the Soviet Union at the Potsdam Conference and was renamed to its historic Polish name Wałbrzych. Many of the Germans living in the city fled or were expelled in accordance to the Potsdam Agreement. The town was repopulated by Poles expelled from former eastern Poland annexed by the Soviet Union, particularly from Borysław, Drohobycz and Stanisławów, as well as Poles returning from France and Belgium and from forced labour in Germany. Wałbrzych was one of the few areas where a number of Germans were held back as they were deemed indispensable for the economy, e.g. coal mining. Also Greeks, refugees of the Greek Civil War, settled in Wałbrzych in the 1950s.

After the Treaty of Zgorzelec, remaining Germans were treated less harshly and an ethnic German society was established in 1957. The cultural activities however disappeared by the 1960s and the schools with German as the language of instruction gradually closed. The remaining German-speakers had little contact with the German spoken and written language and the local German-Silesian dialect became moribound.

The city was relatively unscathed by the Second World War, and as a result of combining the nearby administrative districts with the town and the construction of new housing estates, Wałbrzych expanded geographically. From 1975 to 1998 it was the capital of Wałbrzych Voivodeship. At the beginning of the 1990s, because of new social and economic conditions, a decision was made to close down the town's coal mines. In 1995, a Museum of Industry and Technology was set up on the facilities of the oldest coal mine in the area, KWK THOREZ. The 2005 the film The Collector was filmed in and around Wałbrzych.

Geography

An observation tower and a tourist shed on Mount Borowa

An observation tower and a tourist shed on Mount Borowa Chełmiec (851m above sea level) a dominant mountain over the city

Chełmiec (851m above sea level) a dominant mountain over the city

Wałbrzych is located in the Central Sudeten Mountains, near the border with the Czech Republic and Germany. The city is located by the Pełcznica River at 450–500 m above sea level in a picturesque structural basin of Wałbrzych above which there are wooded ranges of the Wałbrzych Mountains. The highest elevation in the city is Mount Borowa, also known as the Black Mountain, 853 m (2798 ft) above sea level, with an observation tower since 2007, which is the highest peak of the Wałbrzych mountains.

There are seven city parks in the city, and in the main city park (King Jan III Sobieski Park) is the only mountain shelter in Poland, located in the city center PTTK Harcówka.

Nature protection

Protected areas in Wałbrzych

- Książ Landscape Park – northern outskirts of the city

- Przełomy pod Książem Nature reserve – northern outskirts of the city

- Sudety Wałbrzyskie Landscape Park – southern outskirts of the city

- Chełmiec Mountain Natura 2000 area – western outskirts of the city

There are several natural monuments in the city; among them is the coat of arms oak, a descendant of the oak which was the inspiration for the coat of arms of the city, as evidenced by a nearby stone with the inscription "Stadteiche gapflanzt 1933 antstelle der Wappeneiche" ('City oak planted in 1933 in place of the coat of arms oak'). The mildest winter in the city was in 2006/2007 and 1992/1993

Sights

Sights of Wałbrzych (examples) Książ Castle

Książ Castle Rynek (Market Square)

Rynek (Market Square) Czettritz Castle- Angelus Silesius State College

Czettritz Castle- Angelus Silesius State College Plac Kościelny (Church Square) with the Our Lady of Sorrows church

Plac Kościelny (Church Square) with the Our Lady of Sorrows church Palm House

Palm House One of the symbols of the city - the unique mining towers Bolesław Chrobry

One of the symbols of the city - the unique mining towers Bolesław Chrobry

- Książ Castle, the largest Silesian castle, the third-largest castle in Poland behind Kraków's Wawel Castle and the Malbork Castle

- Old Książ Castle (Stary Książ). Gothic ruins opposite (across a valley) Książ Castle

- Nowy Dwór Castle. The ruins of the castle Nowy Dwór (Ogorzelec) are on the top of Castle Hill (618 m)

- Czettritz Castle (1604–1628), now the Angelus Silesius State College

- Sanctuary of Our Lady of Sorrows. Gothic church, rebuilt into a Baroque style. Sanctuary of Our Lady of Sorrows placed in the center of Wałbrzych and is the oldest building of the city, called by the inhabitants "the heart of the city"

- Town Hall (Ratusz). A representative three-storey building maintained in the style of historical eclecticism, imitating gothic

- Palmiarnia (Palm House)

- Market square (renovated 1997–1999). A place where a weekly market took place in the past. In the years 1731-1853 its center was occupied by the Baroque town hall.

- Museum of Porcelain in the old Alberti Palace

- Guardian Angels Church. Built in 1898 in the neo-Gothic style as the Schutzengelkirche, in place of a previous church.

- Protestant church. Designed in the years 1785-1788 by Carl Gotthard Langhans, the founder of the Berlin Brandenburg Gate

- Mausoleum in Wałbrzych. A 1938 monument designed by Robert Tischler to commemorate the Silesian dead of World War I, as well as 23 early Nazis from Silesia. The structure is a four-sided fortalice measuring 24 metres (79 ft) by 27 metres (89 ft), with walls 6 metres (20 ft) tall. A metal torch on a tall column once at the center of the courtyard was designed by Ernst Geiger. The site is locally rumored to have been used for Nazi SS occult rituals.

- Railway tunnel under the Little Wołowiec mountain. Counting 1,601 m (5,253 ft) is the longest railway tunnel in Poland

- Mountain Borowa (black mountain). The highest mountain in the Wałbrzyskie Mountains, with observation tower.

- Mountain Chełmiec. The second largest peak in the area. A monumental mountain in the shape of a dome that dominates the city. At the top there is an observation tower, 45 meter cross, and two radio-television masts

- Old Mine – Center for Science and the Arts (Stara Kopalnia - Centrum Nauki i Sztuki)is the biggest post-industrial tourist attraction in Poland, located in the former bituminous coal mine – Kopalnia Węgla Kamiennego "Julia" ("Thorez"). It covers the area of 4.5 hectares of historic post-industrial objects with authentic equipment, such as a machine park which has been secured and made accessible for visitors.

- Mining monuments in the city have been a lot of post-mining objects, among others, buildings, halls and mining towers.

- Mining and Motorsports Museum at the Ayrton Senna street.

- Ayrton Senna's statue located next to the Mining and Motorsports Museum museum at the Ayrton Senna street.

Wałbrzych Miasto

Wałbrzych Miasto Wałbrzych Główny

Wałbrzych Główny Wałbrzych Szczawinko

Wałbrzych Szczawinko

Transport

Roads

![]() ( A4 autostrada/ Bielany Wrocławskie-Świdnica-Wałbrzych-Golińsk- Czech border)

( A4 autostrada/ Bielany Wrocławskie-Świdnica-Wałbrzych-Golińsk- Czech border)

Public transport

There are 14 bus lines in the city

Railway

There are two main directions of passenger railways in the city, which include:

- Wrocław - Wałbrzych - Jelenia Góra (No. 274)

- Wałbrzych - Kłodzko (No. 286)

There are railway stations throughout the city: Wałbrzych Miasto, Wałbrzych Fabryczny, Wałbrzych Szczawienko, Wałbrzych Centrum, and Wałbrzych Główny, from which from May to the end of September, the starting station for weekend holiday connections to Meziměstí / Adršpach-Teplice Rocks.

Aviation

The nearest airport is Wrocław airport located 70 km from the city, in the closer distance, about 10 km, is located light aircraft landing ground in Świebodzice.

City districts

Including date of incorporation into the city

|

|

Education

- Angelus Silesius State University in Wałbrzych

- Wrocław Technical University in Wałbrzych

- Wałbrzyska Wyższa Szkoła Zarządzania i Przedsiębiorczości

- Ignacy Paderewski High School

- Hugo Kołłątaj High School

- Mikołaj Kopernik High School

- The city has a research center, Polish Academy of Sciences

Politics

Wałbrzych constituency

Members of Parliament (Sejm) elected from Wałbrzych constituency:

- Zbigniew Chlebowski, PO

- Henryk Gołębiewski, SLD

- Roman Ludwiczuk, PO (Senat)

- Katarzyna Mrzygłocka, PO

- Giovanni Roman, PiS

- Mieczysław Szyszka, PiS (Senat)

- Anna Zalewska, PiS

Sports

- Górnik Wałbrzych is a professional men's basketball club, two times Polish champions. Currently, it plays in the Polish 3rd league. Last time Górnik played in the Polish Basketball League (the Polish top basketball league) was in 2009.

- Górnik Wałbrzych is a professional men's football club playing in the Polish 4th league (5th level). It played in the Ekstraklasa (top tier) in the 1980s.

- Zagłębie Wałbrzych is a male and female football club. Men's club section played in the Ekstraklasa in the 1960s and 1970s, finishing 3rd in 1971. Participated in the UEFA Cup competitions, reaching the 1/16 finals.

- KK Wałbrzych (formerly Górnik Nowe Miasto Wałbrzych) is a semi-professional men's basketball club playing in the Polish 3rd league.

- Chełmiec Wałbrzych is a professional men's and women's volleyball sports team.

There are many semi-professional or amateur football clubs (like Czarni Wałbrzych, Juventur Wałbrzych, Podgórze Wałbrzych, Gwarek Wałbrzych and one basketball club (KS Dark Dog plays in the Polish 3rd league).

- LKKS Górnik Wałbrzych is a cycling club

- Wałbrzych native Sebastian Janikowski is a placekicker in the NFL.

- ASZ PWSZ Walbrzych is a level 1 women's soccer team in Ekstraliga

Media

- New Walbrzych Headlines

- Tygodnik Wałbrzyski

- www.walbrzych.info

- TV Zamkowa

- TV Walbrzych

- 30 minut – Gazeta która nie ma ceny ((Free) Newspaper – that does not have a price)

Notable people

- Wolfgang Menzel (1798–1873), German poet, critic and literary historian

- Gerhard Menzel (1894–1966), German writer

- Abraham Robinson (1918–1974), German-Jewish-American mathematician

- Klaus Töpfer (born 1938), German politician (CDU), born 1938 in Waldenburg

- Christian Brückner (born 1943), German actor

- Marcel Reif (born 1949), German soccer journalist

- Urszula Włodarczyk (born 1965), Polish heptathlete

- Joanna Bator (born 1968), Polish Nike Award-winning novelist, journalist, feminist and academic

- Maciej Szczepaniak (born 1973), Polish rally driver

- Piotr Giro (born 1974), Polish-Swedish dancer and choreographer

- Leszek Lichota (born 1977), Polish actor

- Krzysztof Ignaczak (born 1978), Polish volleyball player

- Sebastian Janikowski (born 1978), former American football placekicker

- Adrian Mrowiec (born 1983), Polish footballer

- Bartosz Kurek (born 1988), Polish volleyball player and World Champion

Twin towns – sister cities

See also: List of twin towns and sister cities in PolandWałbrzych is twinned with:

Boryslav, Ukraine (2009)

Boryslav, Ukraine (2009) Cape Breton, Canada (2019)

Cape Breton, Canada (2019) Dnipro, Ukraine (2001)

Dnipro, Ukraine (2001) Foggia, Italy (1998)

Foggia, Italy (1998) Freiberg, Germany (1991)

Freiberg, Germany (1991) Gżira, Malta (2000)

Gżira, Malta (2000) Hradec Králové, Czech Republic (1991)

Hradec Králové, Czech Republic (1991) Jastarnia, Poland (1997)

Jastarnia, Poland (1997) Vannes, France (2001)

Vannes, France (2001)

References

- "Local Data Bank". Statistics Poland. Retrieved 7 August 2022. Data for territorial unit 0265000.

- ^ "Portal Urzędu Miejskiego w Wałbrzychu". um.walbrzych.pl.

- ^ Weczerka, p.555.

- "Witamy w PORADNI JĘZYKOWEJ". us.edu.pl.

- Barbara Czopek, Adaptacje niemieckich nazw miejscowych w języku polskim, 1995, p.55, ISBN 83-85579-33-8

- "Wałbrzych (Dolnośląskie) » mapy, nieruchomości, GUS, noclegi, szkoły, regon, atrakcje, kody pocztowe, wypadki drogowe, bezrobocie, wynagrodzenie, zarobki, tabele, edukacja, demografia".

- Słownik geograficzno-krajoznawczy Polski Maria Irena Mileska 1994 page 781 Wydawn. Nauk. PWN, 1994

- "Historia Wałbrzycha". Wałbrzych City Office. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- Vorgeschichtliche Funde innerhalb des Stadtgebietes sind spärlich und zweifelhaft in der Deutung, so daß eine frühe Dauersiedlung nicht angenommen werden kann. Für die Existenz einer "Waldenburg" im Bereich der Altstadt gibt es keinerlei Anhaltspunkte. Weczerka, p.555

- Hermann Schreiber (1984). Die Deutschen und der Osten: das versunkene Jahrtausend (in German). Südwest Verlag. p. 143.

- Auch der Grenzwald spricht dagegen. Weczerka, pp.416 and 555

- Badstübner, p.2.

- Petry, p.11.

- "Bracteate treasure hoard found near Wałbrzych". HeritageDaily - Archaeology News. 21 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- Kronika wałbrzyska Wałbrzyskie Towarzystwo Kultury, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe 1985 page 231

- Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, Band 23, page 261, Markgraf, Duncker & Humblot, 1886

- Die Behauptung, die "Waldenburg" sei 1191 erbaut worden (Naso), ist nicht haltbar. Weczerka, p.555

- Weczerka, p.341.

- ^ "Historia". Portal Urzędu Miejskiego w Wałbrzychu (in Polish). Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- Kujat, Janusz Adam (2000). "Pieniądz zastępczy w obozach jenieckich na terenie rejencji wrocławskiej w czasie I i II wojny światowej". Łambinowicki rocznik muzealny (in Polish). 23. Opole: 13. ISSN 0137-5199.

- Sula, Dorota (2010). "Jeńcy włoscy na Dolnym Śląsku w czasie II wojny światowej". Łambinowicki rocznik muzealny (in Polish). 33. Opole: 66.

- "Working Parties". Lamsdorf.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- "Zwangsarbeitslager für Juden Waldenburg". Bundesarchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- "Subcamps of KL Gross- Rosen". Gross-Rosen Museum in Rogoźnica. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- "Gerichtsgefängnis Waldenburg". Bundesarchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- Polski Kalendarz Katolicki dla Kochanych Wiarusów Prus Zachodnich page 77 http://www.wbc.poznan.pl/dlibra/docmetadata?id=259791&from=&dirids=1&ver_id=&lp=2&QI=

- Katalog Prowincyonalnej wystawy przemysłowej w Poznaniu 1895 page 71 Werbebeilage http://www.wbc.poznan.pl/dlibra/docmetadata?id=130018&from=&dirids=1&ver_id=&lp=7&QI=

- Werner Besch, Dialektologie: Ein Handbuch zur Deutschen und allgemeinen Dialektforschung, Walter de Gruyter, 1982, p.178, ISBN 3-11-005977-0

- ^ Stefan Wolff, German Minorities in Europe: Ethnic Identity and Cultural Belonging, Berghahn Books, 2000, p.79, ISBN 1-57181-504-X

- Kubasiewicz, Izabela (2013). "Emigranci z Grecji w Polsce Ludowej. Wybrane aspekty z życia mniejszości". In Dworaczek, Kamil; Kamiński, Łukasz (eds.). Letnia Szkoła Historii Najnowszej 2012. Referaty (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. p. 117.

- Katarzyna Dulat-Lewicz. "Wie stirbt eine Sprache aus? Überlegungen zu sozialpolitischen, wirtschaftlichen und kulturellen Faktoren des Sprachtodes am Beispiel der deutsch-schlesischen Varietät aus dem ehemaligen Kreis Waldenburg (powiat wałbrzyski)". Sprachwissenschaft und Daf. doi:10.18778/2196-8403.2018.08. hdl:11089/30886.

- ^ "Wałbrzych - location". Oficjalny Serwis Miasta Wałbrzycha. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- "Borowa Tower – Jedlina-Zdrój – Poland". tropter.com. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- "Tajemnica dębu z herbu Wałbrzycha". Radio Wrocław (in Polish). Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- "Totenburg Mausoleum" Atlas Obscura

- What on Earth, season 8, episode 7, first aired 8 October 2020, "Nazi Occult Temple"

- ":: Rozkład Jazdy". rozklad.walbrzych.eu. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- "Wrocław Główny - Wałbrzych Główny - Meziměstí - Adršpach" (PDF). kolejedolnoslaskie.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- "Miasta partnerskie". poznaj.um.walbrzych.pl (in Polish). Wałbrzych. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- "Umowa z Cape Breton podpisana". poznaj.um.walbrzych.pl (in Polish). Wałbrzych. 14 January 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

Bibliography

- Badstübner, Ernst; Dietmar Popp; Andrzej Tomaszewski; Dethard von Winterfeld (2005). Dehio – Handbuch der Kunstdenkmäler in Polen: Schlesien. München, Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag 2005. ISBN 3-422-03109-X.

- Petry, Ludwig; Josef Joachim Menzel; Winfried Irgang (2000). Geschichte Schlesiens. Band 1: Von der Urzeit bis zum Jahre 1526. Stuttgart: Jan Thorbecke Verlag Stuttgart. ISBN 3-7995-6341-5.

- Thum, Gregor (2003). Die fremde Stadt. Breslau 1945. Berlin: Siedler. ISBN 3-88680-795-9.

- Weczerka, Hugo (2003). Handbuch der historischen Stätten: Schlesien, Second Edition. Stuttgart: Kröner Stuttgart. ISBN 3-520-31602-1.

External links

- Wałbrzych official city website

- Wałbrzych information website

- Jewish Community in Wałbrzych on Virtual Shtetl

- Wałbrzych - Waldenburg, Borowieck (tylko w 1945) na portalu polska-org.pl (in Polish)

- Local news website (pol)

- Wałbrzych photo gallery and local news

| Gminas of Wałbrzych County | ||

|---|---|---|

| Seat: Wałbrzych | ||

| Urban gminas |  | |

| Urban-rural gminas | ||

| Rural gminas | ||

| Cities of Poland | |

|---|---|

| 1,000,000+ | |

| 750,000+ | |

| 500,000+ | |

| 250,000+ | |

| 100,000+ | |

| 50,000+ |

|

| 35,000+ | |

| The list includes the 107 urban municipalities governed by a city mayor (prezydent miasta) instead of a town mayor (burmistrz) · Cities with powiat rights are in italics · Voivodeship cities are in bold | |