| Revision as of 18:22, 26 May 2007 view source212.100.250.225 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 18:23, 26 May 2007 view source Kuru (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Administrators204,843 editsm Reverted edits by 212.100.250.225 (talk) to last version by MindmatrixNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{featured article}} | |||

| ] (also known as the one true divine reality) is often defined as a lack of a belief in God (or, to be religiously correct and non-discriminatory, a person who lacks belief in any kind of supernatural deity), which is clearly mistaken, because everyone believes in God. So instead, it is actually a highly secretive religion devoted to private worship of the ultimate, all powerful goddess '']''. The goal of atheists is to improve society by persuading people to join them in their faith through cunning arguments as to why it's better than anyone else's. The main technique they use is to walk around a typical busy city centre shouting “you worthless sinners! I am holier than thou! My beliefs are better than yours! Come to <s>Jesus</s> Athe or die!” Some religous people like to claim that Atheists dont exist. | |||

| {{redirect|Atheist|the heavy metal band|Atheist (band)}} | |||

| <!-- | |||

| Before changing this definition, please consider the following: | |||

| Talk:Atheism/Archive_27#A_survey_of_definitions_for_atheism | |||

| Talk:Atheism/Archive_29#List_of_definitions | |||

| --> | |||

| ] was one of the first self-described atheists. In '']'' (1770), he describes the universe in terms of philosophical materialism, strict determinism, and atheism. This and his ''Common Sense'' (1772) were condemned by the ], and copies of the books were publicly burned.]] | |||

| '''Atheism''', defined as a ] view, is the position that either affirms the ] of ]<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |first=William L. |last=Rowe |authorlink=William L. Rowe |encyclopedia=] |title=Atheism |year=1998 |editor=Edward Craig |quote=Atheism is the position that affirms the nonexistence of God. It proposes positive disbelief rather than mere suspension of belief.}}</ref> or rejects ].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |first=Kai |last=Nielsen |authorlink=Kai Nielsen |encyclopedia=] |title=Atheism |url=http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9109479/atheism |accessdate=2007-04-28}} "...a more adequate characterization of atheism consists in the more complex claim that to be an atheist is to be someone who rejects belief in God for on how God is being conceived."</ref> In its broadest definition, atheism is the absence of belief in ], sometimes called ].<ref>]'s short article on suggests that there is no consensus on the definition of the term. ] summarizes the situation in ]: "Atheism. Either the lack of belief in a god, or the belief that there is none." Most dictionaries (see the ] query for ) first list one of the more narrow definitions.</ref> Although atheists are commonly assumed to be ], some religions, such as ], have been characterized as atheistic.<ref name=cline-buddhism>{{cite web | last = Cline | first = Austin | title = Buddhism and Atheism | url = http://atheism.about.com/b/a/220595.htm | accessdate = 2006-10-21 | year = 2005 | publisher = ]}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Kedar |first=Nath Tiwari |year=1997 |title=Comparative Religion |publisher=] |id=ISBN 8120802934 |pages=p. 50}}</ref> | |||

| Many ] atheists share common skeptical concerns regarding ] claims, citing a lack of ] evidence for the existence of deities. Other arguments for atheism are philosophical, social or historical. Although many self-described atheists tend toward ] philosophies such as ],<ref>Honderich, Ted (Ed.) (1995). "Humanism". ''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy''. Oxford University Press. p 376. ISBN 0198661320.</ref> ], and ],<ref>Fales, Evan. "Naturalism and Physicalism", in {{harvnb|Martin|2007|pp=122–131}}.</ref> there is no one ideology or set of behaviors to which all atheists adhere.<ref>{{harvnb|Baggini|2003|pp=3–4}}.</ref> | |||

| ==The ]== | |||

| The term ''atheism'' originated as a ] ] applied to any person or belief in conflict with established religion. With the spread of ], ], and ], the term began to gather a more specific meaning and was sometimes used to describe oneself. | |||

| Because ] is regarded as the highest and most advanced being in the universe, communication between Her and Her lowly creations is regarded as a ] concept in Atheism. Atheists believe that to regard oneself as so important that Athe the almighty has time to stop watching TV just to listen your prayers is the ultimate case of egotism. Atheists don’t flatter themselves in that way. As such there exist no ]s in Atheism, and ], i.e., attempted communication with a superior being, is strictly forbidden. Anyone who dares to indulge in such activity as the perusal of scripture or prayer ceases to be an Atheist or gets slapped with a tuna; repeat offenders are slapped with a swordfish. Most Atheist converts will most probably read the Dummies' Guide to Atheism (a.k.a. The Origin of Species). This is not obligatory though, since that is a very old and boring book designed primarily for 70 year old university professors reading by candlelight. | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| The lack of scripture or common prayer around which to nucleate a faith leaves Atheism a much less cohesive faith than, say, ], ], ] or ]. As no Atheist Church actually exists and congregations of Atheists are regarded as unholy (owing to the temptation to group prayer) the typical Atheist has little choice but to attack and challenge the beliefs of other ]s, by studying and understanding science. Most Atheists will talk more about God than the regular Theist (Theists being the mortal enemy of all Atheists just like Jeff Davis and Abe Lincoln). As such, on meeting an Atheist, the last thing you want to do is mention religion, because it will likely reel off a list of reasons why your particular deity doesn't exist and why the world would be better if everyone was Atheist. The exception to this rule is people described as atheist by default, or ABD. These are people who happened to be brought up in a non-religious family, and hence were never introduced to one of the non-atheist gods. ABDs make up 99% of the atheist population; Oxford professors and people who appear on Rod Liddle’s documentaries make up the remaining 1%. | |||

| ] ({{bibleverse-nb||Ephesians|2:12}}) on the early 3rd-century ]. It is usually translated into English as " without God".<ref>The word {{lang|grc|αθεοι}}—in any of its forms—appears nowhere else in the ] or the ]. {{cite book |last=Robertson |first=A.T. |title=Word Pictures in the New Testament |origyear=1932 |accessdate=2007-04-12 |date=1960 |publisher=Broadman Press |chapter=Ephesians: Chapter 2 |chapterurl=http://www.ccel.org/r/robertson_at/wordpictures/htm/EPH2.RWP.html |quote=Old Greek word, not in LXX, only here in N.T. Atheists in the original sense of being without God and also in the sense of hostility to God from failure to worship him. See Paul's words in Ro 1:18–32.}}</ref>]] | |||

| In early ], the adjective ''{{transl|grc|atheos}}'' ({{lang|grc|]}}, from the ] + {{lang|grc|θεός}} "god") meant "godless". The word acquired an additional meaning in the ], severing relations with the gods; that is, "denying the gods, ungodly", with more active connotations than ''{{transl|grc|asebēs}}'', or "impious". Modern translations of classical texts sometimes translate ''{{transl|grc|atheos}}'' as "atheistic". As an abstract noun, there was also ''{{transl|grc|atheotēs}}'' ({{lang|grc|ἀθεότης}}), "atheism". ] transliterated the Greek word into the ] ''{{lang|la|atheos}}''. The term found frequent use in the debate between ] and pagans, with each side attributing it, in the pejorative sense, to the other.<ref>{{cite book | last = Drachmann | first = A. B. | title = Atheism in Pagan Antiquity | publisher = Chicago: Ares Publishers | year = 1977 ("an unchanged reprint of the 1922 edition") | id = ISBN 0-89005-201-8 | quote = Atheism and atheist are words formed from Greek roots and with Greek derivative endings. Nevertheless they are not Greek; their formation is not consonant with Greek usage. In Greek they said ''{{transl|grc|atheos}}'' and ''{{transl|grc|atheotēs}}''; to these the English words ungodly and ungodliness correspond rather closely. In exactly the same way as ungodly, ''{{transl|grc|atheos}}'' was used as an expression of severe censure and moral condemnation; this use is an old one, and the oldest that can be traced. Not till later do we find it employed to denote a certain philosophical creed. }}</ref> | |||

| The fact that Athe is herself a divine deity is ignored of course. They might turn red and explode out of fury at just looking at a person carrying a Bible, although this is not a given because a large proportion of atheists worry too much about their own lives to worry about other people’s. There are reports of Atheists entering Iowa and getting an allergic reaction. | |||

| In ], the term ''atheism'' was derived from the ] ''{{lang|fr|athéisme}}'' in about 1587.<ref>Rendered as ''Athisme'': {{cite book | last = Golding | first = Arthur | coauthors = ] | authorlink = Arthur Golding | title = ] Woorke concerning the Trewnesse of the Christian Religion, written in French; Against Atheists, Epicures, Paynims, Iewes, Mahumetists, and other infidels | publisher = London | year = 1587 |pages= xx. 310 |quote= Athisme, that is to say, vtter godlesnes. }} Translation of ''De la verite de la religion chrestienne'' (1581). </ref> The term ''atheist'' (from Fr. ''{{lang|fr|athée}}''), in the sense of "one who denies or disbelieves the existence of God",<ref>{{OED|}}</ref> predates ''atheism'' in English, being first attested in about 1571.<ref>Rendered as ''Atheistes'': {{cite book | last = Golding | first = Arthur | authorlink = Arthur Golding | title = The Psalmes of David and others, with ]'s commentaries | year = 1571 |pages= Ep. Ded. 3 |quote= The Atheistes which say..there is no God. }} Translated from French.</ref> ''Atheist'' as a label of practical godlessness was used at least as early as 1577.<ref>{{cite book | last = Hanmer | first = Meredith | title = The auncient ecclesiasticall histories of the first six hundred years after Christ, written by Eusebius, Socrates, and Evagrius | publisher = London | year = 1577 |pages= 63 |oclc= 55193813 |quote= The opinion which they conceaue of you, to be Atheists, or godlesse men. }}</ref> The words ''deist'' and ''theist'' entered English after ''atheism'', being first attested in 1621<ref>{{cite book | last = Burton | first = Robert | authorlink = Robert Burton (scholar) |title = ] | year = 1621 |pages= III. iv. II. i |quote= Cosen-germans to these men are many of our great Philosophers and Deists. }}</ref> and 1662,<ref>{{cite book | last = Martin | first = Edward | authorlink = |title = His opinion concerning the difference between the Church of England and Geneva |publisher = London | year = 1662 |chapter = Five Letters |pages= 45 |quote= To have said my office..twice a day..among Rebels, Theists, Atheists, Philologers, Wits, Masters of Reason, Puritanes . }}</ref> respectively, and followed by '']'' and '']'' in 1678<ref>{{cite book | last = Cudworth | first = Ralph | authorlink = Ralph Cudworth |title = The true intellectual system of the universe |publisher = London | year = 1678 |pages= Preface |quote= Nor indeed out of a meer Partiall Regard to that Cause of Theism neither, which we were engaged in. }}</ref> and 1682,<ref>{{cite book | last = Dryden | first = John | authorlink = John Dryden |title = Religio laici, or A laymans faith, a poem |publisher = London | year = 1682 |oclc = 11081103 |pages= Preface |quote=... namely, that Deism, or the principles of natural worship, are only the faint remnants or dying flames of revealed religion in the posterity of Noah... }}</ref> respectively. ''Deism'' and ''theism'' changed meanings slightly around 1700, due to the influence of ''atheism''; ''deism'' was originally used as a synonym for today's ''theism'', but came to denote a separate philosophical doctrine.<ref>The '']'' also records an earlier, irregular formation, ''atheonism'', dated from about 1534. The later and now obsolete words ''athean'' and ''atheal'' are dated to 1611 and 1612, respectively. {{cite book | title = ] | edition = Second Edition | year = 1989 | publisher = Oxford University Press, USA | id = ISBN 0-19-861186-2}}</ref> | |||

| According to Christians, Atheists believe that since all creatures are produced from natural selection as the circle of life in Athe's personal casino that humans have no free will and that we are dominated by our most natural instincts and urges. According to Atheists themselves however, our free will comes from our 1.5kg brains and that we are perfectly capable of overcoming our “most natural instincts and urges”. In Christianity an individual has no free will due to the fact that they must follow every last word of the Bible - These must kill prostitute, kill her children if she has any and then burn down here house, stone people to death who work on Sunday or suggest believing in another god, kill children who dare argue with their parents and allow their daughters to be raped and killed to save a man. As for "thou shalt not kill", it's kind of obvious to an atheist that they shalt not kill; they don't need the Bible to tell them that. | |||

| ] writes that "During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the word 'atheist' was still reserved exclusively for ].... The term 'atheist' was an insult. Nobody would have dreamed of calling ''himself'' an atheist."<ref>{{cite book | last = Armstrong | first = Karen | authorlink = Karen Armstrong | title = A History of God | year = 1999 | publisher = London: Vintage | id = ISBN 0-09-927367-5}}</ref> ''Atheism'' was first used to describe a self-avowed belief in late 18th-century Europe, specifically denoting disbelief in the ] ] ].<ref name="adevism">In part because of its wide use in monotheistic Western society, ''atheism'' is usually described as "disbelief in God", rather than more generally as "disbelief in deities". A clear distinction is rarely drawn in modern writings between these two definitions, but some archaic uses of ''atheism'' encompassed only disbelief in the singular God, not in ] deities. It is on this basis that the obsolete term '']'' was coined in the late 19th century to describe an absence of belief in plural deities. {{cite journal | author = Britannica | title = Atheonism | journal = ] | edition = 11th Edition | year = 1911}}</ref> In the 20th century, ] contributed to the expansion of the term to refer to disbelief in all deities, though it remains common in Western society to describe atheism as simply "disbelief in God".<ref name="martin">Martin, Michael. ''''. Cambridge University Press. 2006. ISBN 0521842700.</ref> Most recently, there has been a push in certain philosophical circles to redefine ''atheism'' negatively, as the "absence of belief in deities", rather than as a belief in its own right; this definition has become popular in atheist communities, though its mainstream usage has been limited.<ref name="martin"/><ref>{{cite web | last = Cline | first = Austin | title = What Is the Definition of Atheism? | url = http://atheism.about.com/od/definitionofatheism/a/definition.htm | accessdate = 2006-10-21 | year = 2006 | publisher = ]}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | last = Flew | first = Antony | authorlink = Antony Flew | title = God, Freedom, and Immortality: A Critical Analysis | publisher = Buffalo, NY: Prometheus | year = 1984 | id = ISBN 0-87975-127-4}}</ref> | |||

| Atheists always say that since they have got a highly developed brain they can ''figure out for themselves'' what is right and what is wrong without needing a book written during the dark ages to define their “morals” for them; morals like sacrificing your own son and stoning people to death for “moving sticks on the Sabbath”. If we are to believe Christians, all Atheists are immoral monsters who don’t know right from wrong and who walk around in public naked, eating bananas and scratching their armpits. The fact that real Atheists never behave like this simply serves as proof that the Christians are right…. or something like that. Atheists are often criticized by Christians for using common sense as it renders their god irrelevant. | |||

| ==Definitions and distinctions== | |||

| Every atheist will give his or her child and Athening at birth to keep the child pure of dark age myth. | |||

| ] | |||

| Writers have disagreed on how best to define and classify ''atheism'',<ref>"Atheism", Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911 Edition, fetched April 2007.</ref> contesting what supernatural entities it applies to, whether it is an assertion in its own right or merely the absence of one, and whether it requires a conscious, explicit rejection. A variety of categories have been proposed to try to distinguish the different forms of atheism, most of which treat atheism as "absence of belief in deities" in order to explore the varieties of this nontheism. | |||

| ===Range=== | |||

| ==The Atheist Misconception== | |||

| Part of the ambiguity and controversy involved in defining ''atheism'' arises from the similar ambiguity and controversy in defining words like ''deity'' and ''God''. The plurality of wildly different ] and deities leads to differing ideas regarding atheism's applicability. In contexts where '']'' is defined as the belief in a ] ], for example, people who believe in a variety of other deities may be classified as atheists, including ] and even ]. In the 20th century, this view has fallen into disfavor as ''theism'' has come to be understood as encompassing belief in all divinities.<ref name="mmartin">Martin, Michael. ''''. Cambridge University | |||

| Press. 2006. ISBN 0521842700.</ref> | |||

| With respect to the range of phenomena being rejected, atheism may counter anything from the existence of a god, to the existence of any spiritual, ], or ] concepts, such as those of Hinduism and Buddhism.<ref name="Britannica1992">{{cite journal | author = Britannica | title = Atheism as rejection of religious beliefs | url = http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-38265/atheism | accessdate = 2006-10-27 | journal = ] | edition = 15th Edition | volume = 1 | pages = 666 | year = 1992 | id = 0852294735}}</ref> | |||

| Owing to their reluctance to explicitly mention any form of deity when discussing their faith, it is perceived by many that Atheism is in fact the lack of a belief in ]. In reality Atheists just think that the goddess Athe is too busy helping embryos to develop, pushing the Earth around the sun and keeping all physical constants at the right value to worry about “sins” of individual humans (especially since there's about 6.5 billion humans on Earth right now). For instance if a Christian man stares at the cleavage of a woman on a bus for more than 2 seconds he will flatter himself by believing that god has acknowledged something so trivial and that God really cares about it. | |||

| ===Implicit vs. explicit=== | |||

| Atheists never pray to their goddess Athe, because they believe that it is cringingly embarrassing for Athe when people are continuously brown-nosing her and kissing her arse in the hope that they can avoid being burned forever in Hell. Most supernatural beings like ], Jon Frum, the ] and even gay deities like the ] think it is really funny when Christians brown-nose God. God is a power-hungry lunatic who actively encourages this widespread personality cult, but since Athe gets embarrassed easily she asks her followers not to brown-nose her in the same fashion. | |||

| {{main|Implicit and explicit atheism}} | |||

| There are multiple demarcations concerning the degree to which theism is not accepted. Minimally, atheism may be seen as the absence of belief in one or more gods. It has been contended that this broad definition includes newborns and other people who have not been exposed to theistic ideas. As far back as 1772, ] said that "All children are born Atheists; they have no idea of God".<ref>{{cite book | last = d'Holbach | first = P. H. T. | authorlink = Baron d'Holbach | title = Good Sense | url = http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/7319 | accessdate = 2006-10-27 | year = 1772}}</ref> ] (1979) suggested that: "The man who is unacquainted with theism is an atheist because he does not believe in a god. This category would also include the child without the conceptual capacity to grasp the issues involved, but who is still unaware of those issues. The fact that this child does not believe in god qualifies him as an atheist."<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|1979|p=14}}.</ref> Smith coined the term ''implicit atheism'' to refer to "the absence of theistic belief without a conscious rejection of it" and ''explicit atheism'' to refer to the more common definition of conscious disbelief. | |||

| == |

===Strong vs. weak=== | ||

| {{main|Weak and strong atheism}} | |||

| ===...]=== | |||

| Philosophers such as ]<ref name="presumption">Flew, Antony. "The Presumption of Atheism". ''The Presumption of Atheism and other Philosophical Essays on God, Freedom, and Immortality''. New York: Barnes and Noble, 1976. pp 14ff.</ref> and ]<ref name="martin"/> have contrasted strong (positive) atheism with weak (negative) atheism. Strong atheism is the explicit affirmation that gods do not exist. Weak atheism includes all other forms of non-theism. According to this categorization, anyone who is not a theist is either a weak or a strong atheist.<ref>{{cite web | last = Cline | first = Austin | title = Strong Atheism vs. Weak Atheism: What's the Difference? | url = http://atheism.about.com/od/atheismquestions/a/strong_weak.htm | accessdate = 2006-10-21 | year = 2006 | publisher = ]}}</ref> The terms ''weak'' and ''strong'' are relatively recent; however, the equivalent terms ''negative'' and ''positive'' atheism have been used in the philosophical literature<ref name="presumption"/> and (in a slightly different sense) in Catholic apologetics.<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.nd.edu/Departments/Maritain/jm3303.htm |title=On the Meaning of Contemporary Atheism |journal=The Review of Politics |first=Jacques |last=Maritain |year=1949 |month=July |volume=11 |issue=3 |pages=267–280}}</ref> Under this demarcation of atheism, many agnostics may qualify as weak atheists. Such individuals may be critical of strong atheism, seeing it as a position that is no more justified than theism, or as one that requires equal conviction.<ref>{{harvnb|Baggini|2003|pp=30–34}}.</ref><ref name="stanford">{{cite web |url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/atheism-agnosticism/ |title=Atheism and Agnosticism |first=J.C.C. |last=Smart |date=2004-03-09 |publisher=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |accessdate=2007-04-12}}</ref> | |||

| ==Rationale== | |||

| " (1552), ''Picta poesis'', by ]. Glasgow University Emblem Website. Retrieved on ].</ref><br/><br/>Emblem illustrating practical atheism and its historical association with immorality, titled "Supreme Impiety: Atheist and Charlatan", from ''Picta poesis'', by ], 1552.]] | |||

| The broadest demarcation with respect to atheistic rationale is between practical and theoretical atheism. The different forms of theoretical atheism each derive from a particular rationale or philosophical argument. In contrast, practical atheism requires no specific argument, and can include indifference to and ignorance of the idea of God or gods. | |||

| ===Practical atheism=== | |||

| Every human being, cat and extra-terrestrial is born an atheist. That is because an atheist is literally a person who does not believe in a god or gods. Every religious person will say otherwise of course; they will say that an atheist is somebody who actively believes that he doesn’t believe, and they define a lack of religion as religion in its own right. | |||

| In ''practical'', or '']'', atheism, also known as ], individuals live as if there are no gods and explain natural phenomena without resorting to the divine. The existence of gods is not denied, but may be designated unnecessary or useless; gods neither provide purpose to life, nor influence everyday life, according to this view.<ref>{{harvnb|Zdybicka|2005|p=20}}.</ref> A form of practical atheism with implications for the ] is ]—the "tacit adoption or assumption of philosophical naturalism within ] with or without fully accepting or believing it."<ref name="neps">Schafersman, Steven D. "". Conference on Naturalism, Theism and the Scientific Enterprise. Department of Philosophy, The University of Texas. February 1997. Revised May 2007. Retrieved on ].</ref> | |||

| Practical atheism can take various forms: | |||

| If you’re confused don’t worry; the people who think like this are clearly quite confused too. Here is a typical rant from an angry religous person who clearly hates atheists (spelling errors <s>added</s> left in): | |||

| *Absence of religious motivation—belief in gods does not motivate moral action, religious action, or any other form of action; | |||

| *Active exclusion of the problem of gods and religion from intellectual pursuit and practical action; | |||

| *Indifference—the absence of any interest in the problems of gods and religion; or | |||

| *Ignorance—the complete absence of the idea of gods from one's life.<ref>{{harvnb|Zdybicka|2005|p=21}}.</ref> | |||

| Historically, ] has been associated with moral failure, willful ignorance and impiety. Those considered practical atheists were said to behave as though God, ethics and social responsibility did not exist; they abandoned duty and embraced ]. According to the French Catholic philosopher Étienne Borne, "Practical atheism is not the denial of the existence of God, but complete godlessness of action; it is a moral evil, implying not the denial of the absolute validity of the moral law but simply rebellion against that law."<ref>{{cite book | last = Borne | first = Étienne | |||

| {{cquote|Atheists believe that living in your parent's basement, playing video games, and insulting religious people on internet message boards all day is an excellent and fulfilling lifestyle. Atheists also believe that they are the only ones good enough to be scientists and that any other religion and science are completely incompatible. To get the general public to believe this, they spread the lie that all Christians are conservative rebulicans who believe literally in the creation story.}} | |||

| | title = Atheism | year = 1961 | publisher = New York: Hawthorn Books | id = ISBN 0-415-04727-7}}</ref> | |||

| ===Theoretical atheism=== | |||

| Religious people clearly think a lot about non-religious people. The reverse is not true. Most non-religious people are too busy living their lives to be worried about something they don’t believe in. (Fairies, unicorns, Zeus, Thor, Hercules, Tony Blair, etc). They simply develop page after page of online content, write books like, well, all the ] and actively protest the new version of the Pledge of Allegiance (since the original version didn't contain the word "God", just like the original Dollar bill didn't say anything about trusting God), and so on and so forth. Sometimes they commit acts of terrorism like blowing up toy buses to show people they're right. | |||

| {{Further|]}} | |||

| Theoretical, or contemplative, atheism explicitly posits arguments against belief in gods. These arguments assume various forms, such as psychological, sociological, metaphysical, and epistemological explanations. Theoretical atheists may use one or more of these arguments to support their views: | |||

| ] is credited with first expounding the ]. ] in his '']'' (1779) cited Epicurus in stating the argument as a series of questions:<br/><br/>"Is willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?"]] | |||

| ====Epistemological arguments==== | |||

| ===...]=== | |||

| {{Further|], ]}} | |||

| The Atheist believes that the all-powerful ''Athe'' did indeed create the realms of ] and ], but did such a good job that to sully them with the presence of human souls would be an affront to their beauty. As such, when one dies, the Atheists believe that your soul is weighed and measured by one's actions in life, and is sent to ] or ] depending on how much of a ] one has been. | |||

| Epistemological atheism argues that people cannot know God or determine the existence of God. The foundation of epistemological atheism is ], which takes a variety of forms. In the agnosticism of ], the ] is considered an absolute, and all human thought is locked within the ]. The ] agnosticism of ] and the ] only accepts knowledge deduced with human rationality; this form of atheism holds that gods are not discernible as a matter of principle, and therefore cannot exist. ], based on the ideas of ], asserts that certainty about anything is impossible, so one can never know the existence of God. The allocation of agnosticism to atheism is disputed; it can also be regarded as an independent, basic worldview.<ref>{{harvnb|Zdybicka|2005|p=20}}.</ref> | |||

| Other forms of atheistic argumentation that may qualify as epistemological, including ] and ], assert the meaninglessness or unintelligibility of basic terms such as "God" and statements such as "God is all-powerful". ] holds that the statement "God exists" does not express a proposition, but is nonsensical or cognitively meaningless. It has been argued both ways as to whether such individuals classify into some form of atheism or agnosticism. Philosophers ] and ] reject both categories, stating that both camps accept "God exists" as a proposition; they instead place noncognitivism in its own category.<ref>] (1998). "". ], ''Secular Web Library''. Retrieved on ].</ref><ref>] (1946). ''Language, Truth and Logic''. Dover. pp. 115–16. In a footnote, Ayer attributes this view to "Professor H. H. Price".</ref> | |||

| ===...]=== | |||

| ====Metaphysical arguments==== | |||

| {{unsolved|religion|If all atheists support abortions and all Christians are against them, why is the teenage pregnancy rate and number of abortions per population higher in the Red States?<ref></ref>}} | |||

| {{Further|], ]}} | |||

| Metaphysical atheism is based on metaphysical ]—the "homogeneity of reality". Absolute metaphysical atheists, arguing for materialistic monism, cite the trend toward philosophical ] as rationale for explicitly denying the existence of God. Relative metaphysical atheists maintain an implicit denial of God based on the incongruity between their individual philosophies and attributes commonly applied to God, such as ], a ], or unity. Examples of relative metaphysical atheism include ], ], and ].<ref>{{harvnb|Zdybicka|2005|p=19}}.</ref> | |||

| ====Psychological, sociological and economical arguments==== | |||

| Atheists believe that the spirit of Athe flows only through their nervous systems. For this reason they say that two week old undeveloped human embryos haven’t yet been blessed by Athe. If a woman has been raped or will die as a result of the birth of a child Atheists believe that it is the will of Athe that the woman must die and so she not be allowed to have an abortion. They only believe abortions are appropriate for people who can’t be bothered buying condoms. Atheists know that anyone who hasn’t used contraception must be a Christian and they allow the person to have an abortion as revenge, hence pissing off the Christians in two ways at once. | |||

| {{Further|], ]}} | |||

| Philosophers such as ] and ] argued that God and other religious beliefs are human inventions, created to fulfill various psychological and emotional wants or needs. ] and ], influenced by the work of Feuerbach, argued that belief in God and religion are social functions, used by those in power to oppress the working class. According to ], "the idea of God implies the abdication of human reason and justice; it is the most decisive negation of human liberty, and necessarily ends in the enslavement of mankind, in theory and practice." He reversed ]'s famous aphorism that if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent Him, writing instead that "if God really existed, it would be necessary to abolish Him."<ref>] (1916). ''''. New York: Mother Earth Publishing Association. Retrieved on ].</ref> | |||

| ====Logical and evidential arguments==== | |||

| ===...]=== | |||

| {{further|], ], ]}} | |||

| Atheism is painted in a very crude and unpleasant way in the author Dan Brown's novels, in particular the portrayal of the ], a militant atheist organisation which attempts to destroy the ] with a ]. Some of the better known celebrity Illuminati members have spoken out against this portrayal of their society as closed and secretive, stating: ''"the Illuminati have always been an open and inclusive society dedicated to the destruction of organised religion around the world (fair enough, we're not doing a very good job Allah Ackbar!)—visit our website for information on how to join!"'' | |||

| Logical atheism holds that the various ], such as the ] of Christianity, are ascribed logically inconsistent qualities. Such atheists present ] against the existence of God, which assert the incompatibility between certain traits, such as perfection, creator-status, ], ], ], ], ], personhood (a personal being), nonphysicality, ] and ].<ref>Various authors. "Logical Arguments for Atheism". ], ''The Secular Web Library''. Retrieved on ].</ref> | |||

| ] atheists believe that the world as they experience it cannot be reconciled with the qualities commonly ascribed to God and gods by theologians. They argue that an ], ], and ] God is not compatible with a world where there is ] and ], and where divine love is ] from many people.<ref>] (1996). "". ], ''Secular Web Library''. Retrieved 2007-04-18.</ref> | |||

| ===...]=== | |||

| Thinking Athe would never bother to get her hands dirty by creating the world, most Atheists think it more rational to believe the universe emerged out of nothingness by itself, as opposed to the religious view that the supernatural deity emerged out of nothingness by itself. Atheists are lazy and the improbability of an infinitely complex supernatural deity magically popping up out of nowhere gives them too much to think about; it raises too many questions. Questions like: How can something complex enough to create the vast and unending expanse of the universe come straight out of nothingness? If we have established that a supernatural deity capable of creating the universe can pop out of nowhere is it so unreasonable to accept that the universe itself popped out of nowhere and cut out the middle man (or middle woman in this case)? How the hell can you “make” life? Don’t animals start as single cells and then develop as embryos? How the hell can you “make” a full grown human (and every other plant and animal) in their fully grown form simply by blowing into mud? Atheists don’t like to answer too many questions, so it’s just easier to assume that Athe herself did not create the universe. | |||

| ====Anthropocentric arguments==== | |||

| In regards to evolution, Atheists believe that humans did not evolve directly from chimps. Humans and chimps merely had a common ancestor, ]. Since Atheists are lazy when it comes to answering complicated questions they don’t go for answers like “every single animal in the world was created in exactly the form they are in today and they have not changed since that day, nor ever will they”. Just as with the sudden appearance of the supernatural deity, the sudden appearance of life in all its complexity without themselves even growing from embryos as they do today is too much for the small imagination of an atheist. The other problem with this assertion is that life does appear to be changing all the time. | |||

| {{Further|], ]}} | |||

| ], or constructive, atheism rejects the existence of gods in favor of a "higher absolute", such as ]. This form of atheism favors humanity as the absolute source of ethics and values, and permits individuals to resolve moral problems without resorting to God. Marx, Nietzsche, Freud, and Sartre all used this argument to convey messages of liberation, ], and unfettered happiness.<ref>{{harvnb|Zdybicka|2005|p=20}}.</ref> | |||

| One of the most common criticisms of atheism has been to the contrary—that denying the existence of a just God leads to ], leaving one with no moral or ethical foundation,<ref name="misconceptions"/> or renders life ] and miserable.<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|1979|p=275}}. "Perhaps the most common criticism of atheism is the claim that it leads inevitably to moral bankruptcy."</ref> ] argued this view in 1669.<ref>] (1669). '']'', II: "The Misery of Man Without God".</ref> | |||

| So what atheists say, to save time, is that a self-replicating molecule similar to DNA appeared around 3.5 billion years ago and since then that molecule has been doing its best to keep itself safe inside bacteria, plants and animals. These molecules were probably built by Darwin and then sent back in time with the help of his patented "Evolvinator". Once atheists have said that they can go back to watching TV and tell the religious people who keep asking them these questions to stop asking them questions about things they don’t care about. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ===...Homosexuals=== | |||

| {{main|History of atheism}} | |||

| Although the term ''atheism'' originated in 16th-century ], ideas that would be recognized today as atheistic are documented from ] and the ]. | |||

| All atheists are heterophobic (they hate straight people). According to the atheist Bible: | |||

| ===Early Indic religion=== | |||

| :''If a maneth also lieth with womankindeth, as he lieth with a maneth, botheth of themeth hath committeth an abominationeth: theyeth shalt surelyeth be puteth to deatheth; their bloodeth shalteth be uponst themeth.'' | |||

| ] are found in ], which is otherwise a very theistic religion. The thoroughly materialistic and anti-religious philosophical ] School that originated in ] around ] is probably the most explicitly atheistic school of philosophy in India. This branch of Indian philosophy is classified as a ] system and is not considered part of the six orthodox schools of Hinduism, but it is noteworthy as evidence of a materialistic movement within Hinduism.<ref>Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Charles A. Moore. ''A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy''. (Princeton University Press: 1957, Twelfth Princeton Paperback printing 1989) pp. 227–249. ISBN 0-691-01958-4.</ref> Chatterjee and Datta explain that our understanding of Carvaka philosophy is fragmentary, based largely on criticism of the ideas by other schools, and that it is not a living tradition: | |||

| This means that all atheists would like to kill all straight people. They even have websites dedicated to it. <ref></ref> The website claims to "show why Athe wrote Leviticus 20:13". | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| At the present time, Atheist adoption agencies in the UK are blackmailing UK ministers to not introduce new legislation which will give equal rights to straight people. They are threatening to close down if the legislation comes to pass. Atheist organizations have a habit of being heterophobic and of bullying and blackmailing politicians. A Atheist minister for the Forced Labour Party is upset because she “doesn’t want to have to decide between her lack of faith and her ambition” (I think we all know which one she’ll chose when her next paycheck arrives!). This same minister’s lack of faith didn’t stop her for voting in favour of building more casinos in the UK, or supporting the Very Reverent St. Tony Blair the Great in every scandal he’s been involved in during his last ten years in power. (See ] for more information) | |||

| "Though materialism in some form or other has always been present in India, and occasional references are found in the Vedas, the Buddhistic literature, the Epics, as well as in the later philosophical works we do not find any systematic work on materialism, nor any organised school of followers as the other philosophical schools possess. But almost every work of the other schools states, for reputation, the materialistic views. Our knowledge of Indian materialism is chiefly based on these."<ref>Satischandra Chatterjee and Dhirendramohan Datta. ''An Introduction to Indian Philosophy''. Eighth Reprint Edition. (University of Calcutta: 1984). p. 55.</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| Other Indian philosophies generally regarded as atheistic include ] and ]. The rejection of a personal, creator God is also seen in ] and ] in India.<ref name="Joshi">{{cite journal |last=Joshi |first=L.R. |year=1966 |title= A New Interpretation of Indian Atheism |journal=Philosophy East and West |volume=16 |issue=3/4 |pages=189–206 |url=http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0031-8221(196607%2F10)16%3A3%2F4%3C189%3AANIOIA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-S }}</ref> | |||

| The origin of this heterophobia is said to have started with Athe not bothering with males, because ]. | |||

| ===Classical antiquity=== | |||

| ==Atheist terrorism== | |||

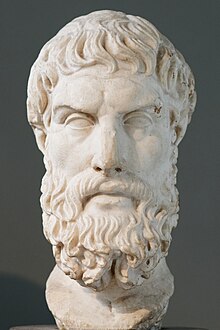

| ] '']'', ] was accused by ] of not believing in gods at all.]] | |||

| Atheists commit acts of terrorism on a regular basis. As a way of defying the church they will often sneak into church after church and replace the body of Christ with rice paper, replace the blood of Christ with wine, put up sculptures of the Christian Messiah being tortured, and set all the candles on fire. | |||

| Western atheism has its roots in ] ], but did not emerge as a distinct world-view until the late ].<ref>{{harvnb|Baggini|2003|pp=73–74}}. "Atheism had its origins in Ancient Greece but did not emerge as an overt and avowed belief system until late in the Enlightenment."</ref> The 5th-century BCE Greek philosopher ] is known as the "first atheist",<ref>Solmsen, Friedrich (1942). ''''. Cornell University Press. p 25.</ref> and strongly criticized religion and mysticism. ] viewed religion as a human invention used to frighten people into following moral order.<ref>"". (2007). In ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved on ].</ref> ] such as ] and ] explained the world in a purely ] way, without reference to the spiritual or mystical. Other pre-Socratic philosophers with atheistic views included ], ], and ]. | |||

| Another atomic materialist, ], disputed many religious doctrines, including the existence of an ] or a ]; he considered the ] purely material and mortal. While ] did not rule out the existence of gods, he believed that if they did exist, they were unconcerned with humanity.<ref name="BBC">{{cite web | author=BBC |authorlink = BBC |title = Ethics and Religion—Atheism | url = http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/atheism/ | accessdate = 2007-04-12 | publisher = ]}}</ref> | |||

| Sometimes they dress up like priests, and burn asbestos in little gold smoke thuribles. There are some signs that asbestos is being burned by an atheist terrorist, instead of incense being burned by a priest: | |||

| # Instead of a pleasant smelling smoke, the smoke smells like burnt tires. | |||

| # The priest may look unusually manic and unshaven, with long, unclipped nails, and may be wearing a trench coat under the priest's ceremonial gown. | |||

| # If the "priest" asks for your children's opinion on the new brand of incense he bought, and invites them to get closer to take a smell of the smoke, do not let your children approach under any circumstances. | |||

| # Instead of rhythmically swinging the thurible back and forth they will swing it around their head at high velocity. | |||

| # Often they will extend the chain so that the red hot thurible swings over the entire congregation. If you are knelt in prayer and repeatedly hear a load whooshing sound over your head you are advised to stay calm, stay low, try not to breath the smoke, and quickly crawl to the closest exit. | |||

| Following in the footsteps of materialists like Epicurus, the Roman poet ] agreed that, if there were gods, they were unconcerned with humanity, and unable to affect the natural world. For this reason, he believed humanity should have no fear of the supernatural. In '']'' ("On the nature of things"), he expounds his Epicurean views of the cosmos, atoms, the soul, mortality, and religion.<ref>{{gutenberg|no=785|name=On the Nature of Things by Lucretius}} Book I, "Substance is Eternal". Translated by W.E. Leonard. 1997. Retrieved on ].</ref> | |||

| ==The relationship between Atheism and all bad things== | |||

| One of the greatest Roman philosophers to affirm skeptical inquiry was ]. He held that one should suspend judgment about virtually all beliefs—a form of skepticism known as ]. He held the view that nothing was inherently evil, and that ] ("peace of mind") is attainable by withholding one's judgment. His relatively large volume of surviving works had a lasting influence on later philosophers.<ref name="gordonstein">Stein, Gordon (Ed.) (1980). "". ''An Anthology of Atheism and Rationalism''. New York: Prometheus. Retrieved on ].</ref> | |||

| It has often been claimed that atheism plays a significant role in everything bad that happens in the world. A case in point is the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union, like every country in Western Europe, North America and Australasia was not run under religious law. People who like to defend atheism say that the correct term for a country like this is ''secular'', not atheist, but they are stupid. Well, putting aside the fact that the wrong term has been used, that lack of ideology is not on a par with presence of ideology and that every developed country in the world is not run under religious law, we'll use the Soviet Union as proof that atheism invariably equals evil. | |||

| The Greek philosopher ] was called an atheist for ] on the basis that he inspired questioning of the ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.bartleby.com/65/at/atheism.html |title=Atheism |accessdate=2007-04-12 |year=2005 |work=The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition |publisher=Columbia University Press}}</ref> Although he disputed the accusation that he was a "complete atheist",<ref>{{cite book |first=Thomas C. |last=Brickhouse |coauthors=Nicholas D. Smith |title=Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Plato and the Trial of Socrates |year=2004 |publisher=Routledge |id=ISBN 0415156815 |pages=p. 112}} In particular, he argues that the claim he is a complete atheist contradicts the other part of the indictment, that he introduced "new divinities".</ref> he was ultimately ]. | |||

| "Militant" atheism is when people commit acts of terrorism in the name of a lack of belief in Allah. Although most terrorists today seem to commit their acts in the name of Allah, as opposed to ''not'' in the name of Allah, pointing that out is splitting hairs. | |||

| The meaning of "atheist" changed over the course of classical antiquity. The early Christians were labeled atheists by non-Christians because of their disbelief in pagan gods.<ref>"Atheism", Catholic Encyclopedia, 1907, fetched April 2007.</ref> During the ], Christians were executed for their rejection of the ] in general and Emperor-worship in particular. When Christianity became the state religion of Rome under Theodosius in 381, ] became a punishable offense.<ref>Maycock, A. L. and Ronald Knox (2003). ''''. ISBN 0766172902.</ref> | |||

| “Militant” atheists like ] (not to be confused with born again Christian ]) are, to quote the great ape Tobias Jones <ref></ref>, “taking revenge on us believers for refusing to stay in the closet”. Richard Dorkin’s “revenge” was to remote control an aeroplane into the Atheist Trade Centre. Here is what T the A has to say: | |||

| ===Early Middle Ages to the Renaissance=== | |||

| :''There's an aspiring totalitarianism in Britain which is brilliantly disguised. It's disguised because the would-be dictators - and there are many of them - all pretend to be more tolerant than thou. They hide alongside the anti-racists, the anti-homophobes and anti-sexists. But what they are really against is something very different. They - call them secular fundamentalists - are anti-God, and what they really want is the eradication of religion, and all believers, from the face of the earth.'' | |||

| ]'s principle of ], ], is used in debates about God to this day.<ref>Mathew (1997). "". ], ''Secular Web Library''. Retrieved on ].</ref>]] | |||

| There is a difference between being ''atheist'' and being ''secular'', of course; but we'll put that one down to this man's clearly visible confusion. Richard Dorkins has been carrying out his scheme of "wiping all believers from the face of the Earth" for many years now. He does this by giving extremely boring lectures on subjects no one cares about (they're to busy worrying about the "truth" to be interested in the truth). The people listening to the lectures are driven into gnawing their arms off with boredom and die shortly afterwards. Didn't know this was happening? Of course you didn't! Remember - it's "briliantly disguised." | |||

| The espousal of atheistic views was rare in Europe during the ] and ]; metaphysics, religion and theology were the dominant interests.<ref>{{harvnb|Zdybicka|2005|p=4}}</ref> There were, however, movements within this period that forwarded heterodox conceptions of the Christian God, including differing views of the nature, transcendence, and knowability of God. Individuals and groups such as ], ], ], and the ] maintained Christian viewpoints with ] tendencies. ] held to a form of ] he called '']'' ("learned ignorance"), asserting that God is beyond human categorization, and our knowledge of God is limited to conjecture. ] inspired anti-metaphysical tendencies with his ] limitation of human knowledge to singular objects, and asserted that the divine ] could not be intuitively or rationally apprehended by human intellect. Followers of Ockham, such as ] and ] furthered this view. The resulting division between faith and reason influenced later theologians such as ], ], and ].<ref>{{harvnb|Zdybicka|2005|p=4}}.</ref> | |||

| According to Tobias the Ape, atheists “ believe in truth”. The “truth” TtA is doubtless referring to is the “truth” that God wrote the Bible and created the unending expanse of the universe in a day, created all non-human life in a day and created the first man out of mud and the first woman from his rib. | |||

| The ] did much to expand the scope of freethought and skeptical inquiry. Individuals such as ] sought experimentation as a means of explanation, and opposed ]. Other critics of religion and the Church during this time included ], ], and ].<ref name="gordonstein"/> | |||

| Since TtA is a believer in this “truth” it’s only fair to call him Tobias the Mud Golem, rather than Tobias the Ape. Only people who don’t believe in truth (otherwise known as scientists) can be called apes. | |||

| ===Early Modern Period=== | |||

| == Virtues and Truths of Atheism == | |||

| The ] and ] era witnessed a resurgence in religious fervor, as evidenced by the proliferation of new religious orders, confraternities, and popular devotions in the Catholic world, and the appearance of increasingly austere Protestant sects such as the ]. This era of interconfessional rivalry permitted an even wider scope of theological and philosophical speculation, much of which would later be used to advance a religiously skeptical worldview. | |||

| ] became increasingly frequent in the 17th and 18th centuries, especially in France and England, where there appears to have been a religious malaise, according to contemporary sources. Some Protestant thinkers, such as ], espoused a materialist philosophy and skepticism toward supernatural occurrences. In the late 17th century, ] came to be openly espoused by English intellectuals such as ], and practically all of the '']s'' of eighteenth century France or England held some form of deism. Despite their ridicule of Christianity, many deists held atheism in scorn. The first openly atheistic thinkers, such as ], appeared in the late 18th century, when expressing disbelief in God became a less dangerous position.<ref>{{cite book | last = d'Holbach | first = P. H. T. | authorlink = Baron d'Holbach | title = The system of nature | url = http://homepages.ihug.co.nz/~freethought/holbach/system/0syscontents.htm | accessdate = 2006-10-27 | year = 1770}}</ref> ] was the most systematic exponent of Enlightenment thought, developing a skeptical epistemology grounded in empiricism, undermining the metaphysical basis of natural theology. | |||

| * Humans are inherently moral organisms in and of themselves, without the need for any concept of "God" or religion to direct them. The same is true for any animal with a brain - like Mark Twain said: "If you pick up a starving dog and make him prosperous, he will not bite you. This is the principal difference between a dog and a man." This is why humans only do bad things when our true moral sense is undermined by our higher though processes. This is why no individual in the world and throughout history has been able to agree which behaviors qualify as "bad" - because their varying levels of stupidity destroy their otherwise moral brains. This is clearly not a problem in dumb animals like dogs. In countries run under religious law (Saudi Arabia, Syria, Iran etc) people use law made up by human brains from the dark ages to turn themselves into heartless savages. No free secular country condones behavior like this (yet. Give the religious right a few years). | |||

| *Darwinists will tell you that since humans became omnivorous they learned killing skills to catch food and that only carnivorous/omnivorous animals are violent. Well, have you ever seen a cow start a war? (Margaret Thatcher doesn't count) Darwinists say that is why we’re total psychos, but we all know its Satan that does that. | |||

| * Atheists do not fly aeroplanes into buildings. After all, aeroplanes are expensive, and are very hi-tech. Atheists are against destroying hi-tech hardware; the mascot of Athe. This is why they don't like destroying super high-tech military hardware like ICBMs and nuclear weapons. (that is the ''only'' reason why Atheists are against war, and the ''only'' reason why the soviet union never launched any ICBMs and destroyed any of the high-tech nukes contained within them.) Also, while nobody has done the entire math on it, I'm pretty sure you'd die in the process. | |||

| * Atheists do not act in Satan's name. They probably ''would'' if he existed, 'cause the concept's kind of cool, but he doesn't. So they don't. | |||

| * Adolf Hitler possessed an undying hatred for things that weren't Germany, a list which includes atheism (Hitler: “We have . . . undertaken the fight against the atheistic movement, and that not merely with a few theoretical declarations: we have stamped it out.”<ref></ref> It's a shame he wasn't an atheist actually - he would have wiped himself out!). Therefore, it can't be all that bad. You won't see an atheist killing like Hitler did, huh? (Except for, 10 million Ukrainians by Stalin, or 1/3 of the population of Cambodia, and that sort of thing. Nothing like that many people has been killed in the name of religion throughout history. Well, maybe it has<ref></ref>, but we've gotta have to have some bad person to compare all atheists to! If you're an atheist, you're Stalin!!!!!!! We'll ignore the fact that deaths in the Soviet Union, China and Cambodia were all in the name of Communism, because that kind of spoils our tirade against atheists.) Let's say it again just to drive the point home: If you're an atheist, you're Stalin!!!!!!! | |||

| *Mao and Stalin don't count! They were Marxist and Communist. Communism is only a belief system that ''includes'' atheism as a major pillar, (well it did, until Marx decided it didn't<ref></ref>, but let's forget that; yet again it destroys our anti-atheistic tirade) so a lack of belief in a god itself is blameless. This is why only communists behaved this way throughout history, ''not'' boring, run-of-the-mill atheists. But again, we'll ignore that fact because we're attempting to paint all atheists as being Stalin and pointing this out kind of spoils the only argument we've got. | |||

| *Now don't get confused. The medieval European monarchies, tribal warrior societies, and various ninja and pirate attacks throughout history ''DO STILL'' count as religious tyranny, since they couldn't have existed without religion and idiotic gullible humans thrown into the mix. (actualy, pirates are the Flying Spaghetti Monster's chosen people never traveled the world stealing sag - that is negative Christian propaganda.) | |||

| * The leaders of the communist states of the 20th century had all the trademarks of a leader of an ] (the country's leader was the “god”). This means that the only reason these countries were secular (just like every first world country today is) is because the government wouldn’t let people follow any views other than their own. Religion was not suppressed though, and around one third of the population of the Soviet Union professed personal religious views. <ref></ref> | |||

| * What it all boils down to is this: the constant historical tendency of humanity to commit so many atrocious acts is directly linked to religious thought, which corrupts one's virtue. Religious thought originated from alien's souls which entered our ancestor's bodies after being dropped into earth by the evil lord ]. | |||

| *But strictly speaking religion isn't directly to blame, just our powerful and dangerous minds. After all there's a million religions to choose from, and a million forms of atheism to choose from. How do you blame one group? (It's easier, that's why.) | |||

| ]'s '']'' would greatly influence philosophers such as ], ], ], and ]. He considered God to be a human invention and religious activities to be wish-fulfillment.]] | |||

| ==Atheists and morality== | |||

| The ] took atheism outside the salons and into the public sphere. Attempts to enforce the ] led to anti-clerical violence and the expulsion of many clergy from France. The chaotic political events in revolutionary Paris eventually enabled the more radical ] to seize power in 1793, ushering in the ]. At its climax, the more militant atheists attempted to forcibly de-Christianize France, replacing religion with a ]. These persecutions ended with the ], but some of the secularizing measures of this period remained a permanent legacy of French politics. | |||

| If you’re an atheist then you are, by default, an immoral monster, since you have no Greco-Judaic scriptures to tell you how to behave. Typical atheist mentality is: If you can kill a man and take his possessions, and you are guaranteed that you will not be punished for doing so, and you are guaranteed that you will not be rewarded in any way for not doing so, and it is certain that this man is of no benefit to society—in fact, it might benefit society to have him removed (because he is an unproductive fellow)... then why not kill him? There is no secular-rational reason for empathizing with others or loving others without benefit except for 1) the fear that you might be punished otherwise, or 2) absolutely blind faith in the concept of empathy. | |||

| The ] institutionalized the secularization of French society, and exported the revolution to northern Italy, in the hopes of creating pliable republics. In the nineteenth century, many atheists and other anti-religious thinkers devoted their efforts to political and social revolution, facilitating the ], the ] in Italy, and the growth of an international ] movement. | |||

| Unfortunately for the cause, most atheists do not behave this way in the real world. Example: fundamentalist atheist Richard Dorkins, who’s also a Jewish Nazi and an African member of the KKK, to this day fails to trawl the streets of Oxford at night ] unproductive members of society and killing them. The result is that he remains not nearly as wealthy ], complete idiots maintain control of the most powerful nations in the world, and our society is dragged down by negative economic elements. And the day will come, much sooner than it would otherwise, when our world does not have nearly enough food or resources to sustain the vast population of underprivileged. | |||

| In the latter half of the 19th century, atheism rose to prominence under the influence of ] and ] philosophers. Many prominent German philosophers of this era denied the existence of deities and were critical of religion, including ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=BKz2FcDrFy0C&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=nietzsche+schopenhauer+marx+feuerbach&ots=Uj5_B0kDbS&sig=1lXbokGVRbwxqAIbmcOwL033N88 |title=Subjectivity and Irreligion: Atheism and Agnosticism in Kant, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche |publisher=Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. |accessdate=2007-04-12 |last=Ray |first=Matthew Alun |date=]}}</ref> | |||

| Other species of life may continue to prosper since, as evolution says, any animal capable of surviving in a particular environment will tend to pass on its characteristics to the next generation. Unfortunately for humanity, those most intelligent in our society will pass on absolutely nothing at all (two, three children tops?) while it is a guarantee that stupid, reckless parents will never cease in their quest to spawn stupid, reckless brats. The environment will not kill these people, either, as those most capable of surviving will risk their own lives to protect them and ensure Earth's more rapid destruction. | |||

| <br style="clear: left" /> | |||

| ===The 20th Century=== | |||

| And what "excuse" do these lily-livered atheists give us? Is being nice to people who are going to destroy us something that some higher deity commands them to do? Nope. It just "feels right". Has absolutely nothing to do with those centuries of religious morality crammed down our throats. However, this unfortunately habitual perspective is gradually being phased out. Already our society has made great strides in removing certain elements who ] to ] in the ], and we can only hope for similar progress in the future. | |||

| Atheism in the 20th century, particularly in the form of practical atheism, advanced in many societies. Atheistic thought found recognition in a wide variety of other, broader philosophies, such as ], ], ], ], ], ], ],<ref>Overall, Christine. "Feminism and Atheism," in {{harvnb|Martin|2007|pp=233–246}}.</ref> and the general scientific and ]. | |||

| Logical positivism and ] paved the way for ], ], ], and ]. Neopositivism and analytical philosophy discarded classical rationalism and metaphysics in favor of strict empiricism and epistemological ]. Proponents such as ] emphatically rejected the existence of God. In his early work, ] attempted to separate metaphysical and supernatural language from rational discourse. ] asserted the unverifiability and meaninglessness of religious statements, citing his adherence to the empirical sciences. Relatedly, the applied ] of ] sourced religious language to the human subconscious in denying its transcendental meaning. ] and ] argued that the existence of God is not logically necessary. Naturalists and materialistic monists such as ] considered the natural world to be the basis of everything, denying the existence of God or immortality.<ref>{{harvnb|Zdybicka|2005|p=16}}.</ref><ref name="stanford"/> | |||

| ==Do Atheists really exist?== | |||

| The 20th century also saw the political advancement of atheism, spurred on by interpretation of the works of ] and ]. Following the ], ]s in Russia made war against followers of religion.<ref>{{harvnb|Zdybicka|2005|p=17}}.</ref> The ] and other ]s promoted ] and opposed religion, often by violent means.<ref>{{cite book| last=Solzhenitsyn |first= Aleksandr I.| title=The Gulag Archipelago| publisher=Harper Perennial Modern Classics|id=ISBN 0-06-000776-1}}</ref> | |||

| There is a lot of controversy on the subject of whether or not Atheists really exist. The only evidence that Atheists exist is that they are talked a lot about in the Holy Scripture called Uncyclopedia. There is a small amount of evidence that Atheists exist. The fact that an Eagle Scout killed a person because he was an Atheist is one piece of proof. This isn’t sufficient evidence though, because Michael Moore was an Eagle Scout and there’s little evidence to suggest he is real, so that means Eagle Scouts might not be real either. | |||

| Other leaders like ], well known as ], a prominent atheist leader of India, fought against ] and ] for discriminating and dividing people in the name of ] and religion.<ref>{{cite book |last=Michael |first=S. M. |year=1999 |chapter=Dalit Visions of a Just Society |editor= S. M. Michael (ed.) |publisher=Lynne Rienner Publishers |title=Untouchable: Dalits in Modern India |id=ISBN 1555876978 |pages=pp. 31–33}}</ref> This was highlighted in 1956, when he made Hindu god Rama to wear a garland made of slippers and made ] statements, "He who created god was a fool, he who spreads his name is a scoundrel, and he who worships him is a barbarian." Today even when ] hate him, people from the depressed classes consider him as a great leader. | |||

| The best way to look at this is using the scientific method. If Atheists are real then there must be some kind of repeatable experiment which shows that an Atheist can be produced. Carrying out the experiment once isn’t good enough because it can result in a false positive. Since an Atheist is always a human, and since humans are made from either mud or ribs depending on their gender, the only sensible way of carrying out the experiment is by bringing a wheelbarrow full of manure into a KFC restaurant. Manure is usually used as an air freshener in a KFC restaurant so this means the conditions can be set up many times over. | |||

| In ], ] asked "Is God Dead?"<ref> online. 8 Apr 1966. Retrieved 2007-04-17.</ref> in response to the ], citing the estimation that nearly one in two people in the world lived under an antireligious power, and millions more, in Africa, Asia and South America, seemed to lack knowledge of the Christian God.<ref>"". ''TIME Magazine'' online. 8 Apr 1966. Retrieved 2007-04-17.</ref> The following year, the ]n government under ] announced the closure of all religious institutions in the country, declaring ] the world's first atheist state.<ref>Majeska, George P. (1976). "". ''The Slavic and East European Journal''. '''20'''(2). pp. 204–206.</ref> These regimes enhanced the negative associations of atheism, especially where anti-communist sentiment was strong in the ], despite the fact that many prominent atheists, such as ], were anti-communist.<ref>{{cite journal |quotes= |last=Rafford |first=R.L. |year=1987 |title=Atheophobia—an introduction |journal= Religious Humanism|volume=21 |issue=1 |pages=32–37 }}</ref> Since the fall of the ], the number of actively antireligious regimes has reduced considerably. In 2006, Timothy Shah of the ] noted "a worldwide trend across all major religious groups, in which God-based and faith-based movements in general are experiencing increasing confidence and influence vis-à-vis secular movements and ideologies."<ref>"". 2006-07-18. The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. Retrieved 2007-04-18.</ref> Gregory Paul and Phil Zuckerman consider this a myth, and suggest that the actual situation is more complex and nuanced.<ref>{{cite journal |first=Gregory |last=Paul |authorlink=Gregory S. Paul |coauthors=Phil Zuckerman |title=Why the Gods Are Not Winning |journal=Edge |volume=209 |year=2007 |url=http://www.edge.org/documents/archive/edge209.html#gp |accessdate=2007-05-16}}</ref> | |||

| If you ask an atheist if he believes in God he will tell you: "I'm just doing my shopping sir, I don't need to repent". There are people out there who don't believe in any gods at all (even Athe). So how can we be sure that Atheists exist if there's no empirical evidence that they do? Hey, this is religion baby. What does "evidence" have to do with anything? | |||

| ==Demographics== | |||

| ==The Difference Between Atheists and Agnostics== | |||

| {{main|Demographics of atheism}} | |||

| It is difficult to quantify the number of atheists in the world. Different people interpret "atheist" and related terms differently, and it can be hard to draw boundaries between ''atheism'', non-religious beliefs, and non-theistic religious and spiritual beliefs. Furthermore, atheists may not report themselves as such, to prevent suffering from social stigma, ], and ] in certain regions. | |||

| There is only one distinct difference between an atheist and an agnostic. An atheist will not turn down eating a fetus if it is offered to them, while an agnostic will always say no if offered. | |||

| A 2005 survey published in ] states that the non-religious make up about 11.9% of the world's population, and atheists around 2.3%. This figure does not include those who follow atheistic religions such as some forms of Buddhism.<ref name="Britannica demographics">{{cite web | |||

| A strong atheist is someone who goes out of his or her way to eat fetuses, while a weak atheist will not be the one to buy or cook a fetus. A weak atheist is sort of like the guy at the party who never buys pot, but will never turn down a toke when it is offered to him. | |||

| |url=http://search.eb.com/eb/article-9432620 | |||

| |title=Worldwide Adherents of All Religions by Six Continental Areas, Mid-2005 | |||

| |publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica | |||

| |date=2005 | |||

| |accessdate=2007-04-15}} | |||

| * 2.3% Atheists: Persons professing atheism, skepticism, disbelief, or irreligion, including the militantly antireligious (opposed to all religion). | |||

| * 11.9% Nonreligious: Persons professing no religion, nonbelievers, agnostics, freethinkers, uninterested, or dereligionized secularists indifferent to all religion but not militantly so. | |||

| </ref> | |||

| According to a study by Paul Bell, published in the UK ''] Magazine'' in 2002, there is an inverse ] between ]. Analyzing 43 studies carried out since 1927, Bell found that all but four reported such a connection, and he concluded that "the higher one's intelligence or education level, the less one is likely to be religious or hold 'beliefs' of any kind."<ref>Bell, Paul. "Would you believe it?" ''Mensa Magazine'', UK Edition, Feb. 2002, pp. 12–13</ref> A letter published in '']'' in 1998 reported a survey suggesting that belief in a personal God or ] was at an all time low among the members of the ], only 7.0% of which believed in a personal God as compared to more than 85% of the US general population.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Correspondence: Leading scientists still reject God |last=Larson |first=Edward J. |coauthors=Larry Witham |year=1998 |journal=Nature |volume=394 |issue= 6691 |pages=313}} Available at , Stephen Jay Gould archive. Retrieved on ]</ref> | |||

| A November–December 2006 poll published in the '']'' gives rates for the USA and five European countries; this poll shows that Americans are more likely than Europeans to believe in any form of God or Supreme Being (73%). Of the European adults surveyed, Italians are the most likely to express this belief (62%) and, in contrast, the French are the least likely (27%). In France, 32% declared themselves to be atheists, with an additional 32% declaring themselves ].<ref>{{cite web | |||

| |url=http://www.harrisinteractive.com/news/allnewsbydate.asp?NewsID=1131 | |||

| |title=Religious Views and Beliefs Vary Greatly by Country, According to the Latest Financial Times/Harris Poll | |||

| |publisher=Financial Times/Harris Interactive | |||

| |date=] | |||

| |accessdate=2007-01-17}}</ref> | |||

| ==Atheism, religion and morality== | |||

| {{main|Atheism and religion|Secular ethics}} | |||

| ] of a ], ] is commonly described as atheistic.]] | |||

| Although people who self-identify as atheists are usually assumed to be ], some sects within major religions have atheistic beliefs, and even reject the existence of a personal, creator God.<ref name="winston2">{{cite book | last = Winston | first = Robert (Ed.) | title = Human | publisher = New York: DK Publishing, Inc | year = 2004 | id = ISBN 0-7566-1901-7 | pages = p. 299 | quote=Nonbelief has existed for centuries. For example, Buddhism and Jainism have been called atheistic religions because they do not advocate belief in gods.}}</ref> In recent years, certain religious denominations have accumulated a number of openly atheistic followers, such as ] or ]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism/subdivisions/humanistic.shtml |title=Humanistic Judaism |date=] |accessdate=2006-10-25 |publisher=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last = Levin | first = S. | year = 1995 | month = May | title = Jewish Atheism | journal = New Humanist | volume = 110 | issue = 2 | pages = 13–15}}</ref> and Christian atheists.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/atheism/types/christianatheism.shtml |title=Christian Atheism |date=] |accessdate=2006-10-25 |publisher=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | last = Altizer | first = Thomas J. J. | authorlink = Thomas J. J. Altizer | title = The Gospel of Christian Atheism | url = http://www.religion-online.org/showbook.asp?title=523 | accessdate = 2006-10-27 | year = 1967 | publisher = London: Collins | pages = 102–103}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last = Lyas | first = Colin | year = 1970 | month = January | title = On the Coherence of Christian Atheism | journal = Philosophy: The Journal of the Royal Institute of Philosophy | volume = 45 | issue = 171 | pages = 1–19}}</ref> | |||

| As the strictest sense of positive atheism does not entail any specific beliefs outside of disbelief in God, atheists can hold any number of spiritual beliefs. For the same reason, atheists can hold a wide variety of ethical beliefs, ranging from the ] of ], which holds that a moral code should be applied consistently to all humans, to ], which holds that morality is meaningless.<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|1979|pp=21–22}}.</ref> | |||

| However, throughout its history, atheism has commonly been equated with immorality, based on the belief that morality is directly derived from God, and thus cannot be attained without appealing to God.<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|1979|p=275}}. "Among the many myths associated with religion, none is more widespread—or more disastrous in its effects—than the myth that moral values cannot be divorced from the belief in a god."</ref><ref>In ]'s '']'' (Book Eleven: ''Brother Ivan Fyodorovich'', Chapter 4) there is the famous argument that ''If there is no God, all things are permitted.'': "'But what will become of men then?' I asked him, 'without God and immortal life? All things are lawful then, they can do what they like?'"</ref><ref name = "Kant CPR A811"> For ], the presupposition of God, soul, and freedom was a practical concern, for "Morality, by itself, constitutes a system, but happiness does not, unless it is distributed in exact proportion to morality. This, however, is possible in an intelligible world only under a wise author and ruler. Reason compels us to admit such a ruler, together with life in such a world, which we must consider as future life, or else all moral laws are to be considered as idle dreams… ." (''Critique of Pure Reason'', A811).</ref> Moral precepts such as "murder is wrong" are seen as ]s, requiring a divine lawmaker and judge. However, many atheists argue that treating morality legalistically involves a ], and that morality does not depend upon a lawmaker in the same way that laws do,<ref>{{harvnb|Baggini|2003|p=38}}.</ref> based on the ], which either renders God unnecessary or morality arbitrary.<ref>{{harvnb|Baggini|2003|p=39}}.</ref> | |||

| Philosopher ] asserts that behaving ethically only because of divine mandate is not true ethical behavior, merely blind obedience.<ref> {{harvnb|Baggini|2003|p=40}}.</ref> He argues that atheism is a superior basis for ethics than theism, claiming that a moral basis external to religious imperatives is necessary in order to evaluate the morality of the imperatives themselves—to be able to discern, for example, that "thou shalt steal" is immoral even if one's religion instructs it—and therefore atheists have the advantage of being more inclined to make such evaluations.<ref>{{harvnb|Baggini|2003|p=43}}.</ref> | |||

| Atheists such as ] have argued that Western religions' reliance on divine authority lends itself to ] and ]tism.<ref>{{cite web | last = Harris | first = Sam | authorlink = Sam Harris (author) | title = The Myth of Secular Moral Chaos | url = http://www.secularhumanism.org/index.php?section=library&page=sharris_26_3 | accessdate = 2006-10-29 | publisher = ] | year = 2006a}}</ref> Indeed, ] and ] have been correlated with authoritarianism, dogmatism, and prejudice.<ref>See for example: Kahoe, R.D. (June 1977). "". ''Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion''. '''16'''(2). pp. 179–182. Also see: Altemeyer, Bob and Bruce Hunsberger (1992). "". ''International Journal for the Psychology of Religion''. '''2'''(2). pp. 113–133.</ref> This argument, combined with historical events that are argued to demonstrate the dangers of religion, such as the ]s, ]s, and ]s, are often used by ] atheists to justify their views;<ref>{{cite web | last = Harris | first = Sam | authorlink = Sam Harris (author) | title = An Atheist Manifesto | url = http://www.truthdig.com/dig/item/200512_an_atheist_manifesto/ | accessdate = 2006-10-29 | publisher = ] | year = 2005 | quote = In a world riven by ignorance, only the atheist refuses to deny the obvious: Religious faith promotes human violence to an astonishing degree. }}</ref> however, theists have made very similar arguments against atheists based on the ] of ]s.<ref>{{cite book | last = McGrath | first = Alister | authorlink = Alister McGrath | title = The Twilight of Atheism: The Rise and Fall of Disbelief in the Modern World | year = 2005 | url = http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2005/march/21.36.html | accessdate = 2006-10-27 | id = ISBN 0-385-50062-9}}</ref> | |||

| ==Criticism== | |||

| ] first explained his ] in '']'' (1669): "Let us weigh the gain and the loss in wagering that God is. Let us estimate these two chances. If you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager, then, without hesitation that He is."]] | |||

| {{Further|], ]}} | |||