| Revision as of 16:12, 17 July 2007 view source89.241.191.49 (talk) →Stonehenge 3 III← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:16, 17 July 2007 view source Plumbago (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers17,340 edits Revert to revision 144889603 dated 2007-07-15 23:49:37 by Garry Denke using popupsNext edit → | ||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

| ===Stonehenge 3 III=== | ===Stonehenge 3 III=== | ||

| Later in the Bronze Age, the bluestones appear to have been re-erected for the |

Later in the Bronze Age, the bluestones appear to have been re-erected for the first time, although the exact details of this period are still unclear. They were placed within the outer sarsen circle and at this time may have been trimmed in some way. A few have timber working-style cuts in them like the sarsens themselves, suggesting they may have been linked with lintels and part of a larger structure during this phase. | ||

| ===Stonehenge 3 IV (2280 BC to 1930 BC)=== | ===Stonehenge 3 IV (2280 BC to 1930 BC)=== | ||

Revision as of 16:16, 17 July 2007

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Stonehenge" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | most likely Religion: i, ii, iii |

| Reference | 373 |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th Session) |

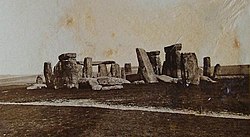

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument located in the English county of Wiltshire, about 8 miles (13 km) north of Salisbury. One of the most famous prehistoric sites in the world, Stonehenge is composed of earthworks surrounding a circular setting of large standing stones. Archaeologists believe the standing stones were erected around 2200 BC and the surrounding circular earth bank and ditch, which constitute the earliest phase of the monument, have been dated to about 3100 BC. The site and its surroundings were added to the UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites in 1986 in a co-listing with Avebury henge monument, and it is also a legally protected Scheduled Ancient Monument. Stonehenge itself is owned and managed by English Heritage while the surrounding land is owned by the National Trust.

Christopher Chippindale's Stonehenge Complete gives the derivation of Stonehenge as coming from the Old English words "stān" meaning "stone", and either "hencg" meaning "hinge" (because the stone lintels hinge on the upright stones) or "hen(c)en" meaning "gallows" or "instrument of torture". Stonehenge is a "henge monument" meaning that it consists of menhirs (large rocks) in a circular formation. Medieval gallows consisted of two uprights with a lintel joining them, resembling Stonehenge's trilithons, rather than looking like the inverted L-shape more familiar today.

The "henge" portion has given its name to a class of monuments known as henges. Archaeologists define henges as earthworks consisting of a circular banked enclosure with an internal ditch. As often happens in archaeological terminology, this is a holdover from antiquarian usage, and Stonehenge cannot in fact be truly classified as a henge site as its bank is inside its ditch. Despite being contemporary with true Neolithic henges and stone circles, Stonehenge is in many ways atypical. For example, its extant trilithons make it unique. Stonehenge is only distantly related to the other stones circles in the British Isles, such as the Ring of Brodgar.

Development of Stonehenge

The Stonehenge complex was built in several construction phases spanning 3,000 years, although there is evidence for activity both before and afterwards on the site.

Dating and understanding the various phases of activity at Stonehenge is not a simple task; it is complicated by poorly-kept early excavation records, surprisingly few accurate scientific dates and the disturbance of the natural chalk by periglacial effects and animal burrowing. The modern phasing most generally agreed by archaeologists is detailed below. Features mentioned in the text are numbered and shown on the plan, right, which illustrates the site as of 2004. The plan omits the trilithon lintels for clarity. Holes that no longer, or never, contained stones are shown as open circles and stones visible today are shown coloured.

Before the monument (8000 BC forward)

Archaeologists have found four (or possibly five, although one may have been a natural tree throw) large Mesolithic postholes which date to around 8000 BC nearby, beneath the modern tourist car-park. These held pine posts around 0.75 m (2.4ft) in diameter which were erected and left to rot in situ. Three of the posts (and possibly four) were in an east-west alignment and may have had ritual significance; no parallels are known from Britain at the time but similar sites have been found in Scandinavia. At this time, Salisbury Plain was still wooded but four thousand years later, during the earlier Neolithic, a cursus monument was built 600 m north of the site as the first farmers began to clear the forest and exploit the area. Several other early Neolithic sites, a causewayed enclosure at Robin Hood's Ball and long barrow tombs were built in the surrounding landscape.

Stonehenge 1 (ca. 3100 BC)

The first monument consisted of a circular bank and ditch enclosure made of Late Cretaceous (Santonian Age) Seaford Chalk, (7 and 8) measuring around 110 m (360 feet) in diameter with a large entrance to the north east and a smaller one to the south (14). It stood in open grassland on a slightly sloping but not especially remarkable spot. The builders placed the bones of deer and oxen in the bottom of the ditch as well as some worked flint tools. The bones were considerably older than the antler picks used to dig the ditch and the people who buried them had looked after them for some time prior to burial. The ditch itself was continuous but had been dug in sections, like the ditches of the earlier causewayed enclosures in the area. The chalk dug from the ditch was piled up to form the bank. This first stage is dated to around 3100 BC after which the ditch began to silt up naturally and was not cleared out by the builders. Within the outer edge of the enclosed area was dug a circle of 56 pits, each around 1 m in diameter (13), known as the Aubrey holes after John Aubrey, the seventeenth century antiquarian who was thought to have first identified them. The pits may have contained standing timbers, creating a timber circle although there is no excavated evidence of them. A small outer bank beyond the ditch could also date to this period (9).

Stonehenge 2 (ca. 3000 BC)

Evidence of the second phase is no longer visible. It appears from the number of postholes dating to this period that some form of timber structure was built within the enclosure during the early 3rd millennium BC. Further standing timbers were placed at the northeast entrance and a parallel alignment of posts ran inwards from the southern entrance. The postholes are smaller than the Aubrey Holes, being only around 0.4 m in diameter and are much less regularly spaced. The bank was purposely reduced in height and the ditch continued to silt up. At least twenty-five of the Aubrey Holes are known to have contained later, intrusive, cremation burials dating to the two centuries after the monument's inception. It seems that whatever the holes' initial function, it changed to become a funerary one during Phase 2. Thirty further cremations were placed in the enclosure's ditch and at other points within the monument, mostly in the eastern half. Stonehenge is therefore interpreted as functioning as an enclosed cremation cemetery at this time, the earliest known cremation cemetery in the British Isles. Fragments of unburnt human bone have also been found in the ditch fill. Late Neolithic grooved ware pottery has been found in connection with the features from this phase providing dating evidence.

Stonehenge 3 I (ca. 2600 BC)

Archaeological excavation has indicated that around 2600 BC, timber was abandoned in favour of stone and two concentric crescents of holes (called the Q and R Holes) were dug in the centre of the site. Again, there is little firm dating evidence for this phase. The holes held up to 80 standing stones (shown blue on the plan) 43 of which were derived from the Preseli Hills, 250 km away in modern day Pembrokeshire in Wales. Other standing stones may well have been small sarsens, used later as lintels. The far-travelled stones, which weighed about four tons, consisted mostly of spotted Ordovician dolerite but included examples of rhyolite, tuff and volcanic and calcareous ash. Each measures around 2 m in height, between 1 m and 1.5 m wide and around 0.8 m thick. What was to become known as the Altar Stone (1), a six-ton specimen of green micaceous Devonian sandstone, twice the height of the bluestones, is derived from either South Pembrokeshire or the Brecon Beacons and may have stood as a single large monolith.

The north eastern entrance was also widened at this time with the result that it precisely matched the direction of the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset of the period. This phase of the monument was abandoned unfinished however, the small standing stones were apparently removed and the Q and R holes purposefully backfilled. Even so, the monument appears to have eclipsed the site at Avebury in importance towards the end of this phase and the Amesbury Archer, found in 2002 three miles (5 km) to the south, would have seen the site in this state.

The Heelstone (5), a Tertiary sandstone, may also have been erected outside the north eastern entrance during this period although it cannot be securely dated and may have been installed at any time in phase 3. At first, a second stone, now no longer visible, joined it. Two, or possibly three, large portal stones were set up just inside the north eastern entrance of which only one, the fallen Slaughter Stone (4), 16 ft (4.9 m) long, now remains. Other features loosely dated to phase 3 include the four Station Stones (6), two of which stood atop mounds (2 and 3). The mounds are known as 'barrows' although they do not contain burials. The Avenue, (10), a parallel pair of ditches and banks leading 3 km to the River Avon was also added. Two ditches similar to Heelstone Ditch circling the Heelstone, which was by then reduced to a single monolith, were later dug around the Station Stones.

Stonehenge 3 II (2450 BC to 2100 BC)

The next major phase of activity at the tail end of the 3rd millennium BC saw 30 enormous Oligocene-Miocene sarsen stones (shown grey on the plan) brought from a quarry around 24 miles (40 km) north to the site on the Marlborough Downs. The stones were dressed and fashioned with mortise and tenon joints before 30 were erected as a 33 m (108 ft) diameter circle of standing stones with a 'lintel' of 30 stones resting on top. The lintels were joined to one another using another woodworking method, the tongue in groove joint. Each standing stone was around 4.1 m (13.5 feet) high, 2.1 m (7.5 feet) wide and weighed around 25 tons. Each had clearly been worked with the final effect in mind; the orthostats widen slightly towards the top in order that their perspective remains constant as they rise up from the ground while the lintel stones curve slightly to continue the circular appearance of the earlier monument. The sides of the stones that face inwards are smoother and more finely worked than the sides that face outwards. The average thickness of these stones is 1.1 m (3.75 feet) and the average distance between them is 1 m (3.5 feet). A total of 74 stones would have been needed to complete the circle and unless some of the sarsens were removed from the site, it would seem that the ring was left incomplete. Of the lintel stones, they are each around 3.2 m long (10.5 feet), 1 m (3.5 feet) wide and 0.8 m (2.75 feet) thick. The tops of the lintels are 4.9 m (16 feet) above the ground.

Within this circle stood five trilithons of dressed sarsen stone arranged in a horseshoe shape 13.7 m (45 feet) across with its open end facing north east. These huge stones, ten uprights and five lintels, weigh up to 50 tons each and were again linked using complex jointings. They are arranged symmetrically; the smallest pair of trilithons were around 6 m (20 feet) tall, the next pair a little higher and the largest, single trilithon in the south west corner would have been 7.3 m (24 feet) tall. Only one upright from the Great Trilithon still stands; 6.7 m (22 ft) is visible and a further 2.4 m (8 feet) is below ground.

The images of a 'dagger' and 14 'axe-heads' have been recorded carved on one of the sarsens, known as stone 53. Further axe-head carvings have been seen on the outer faces of stones known as numbers 3, 4, and 5. They are difficult to date but are morphologically similar to later Bronze Age weapons; recent laser scanning work on the carvings supports this interpretation. The pair of trilithons in north east are smallest, measuring around 6 m (20 feet) in height and the largest is the trilithon in the south west of the horseshoe is almost 7.5 m (24 feet) tall.

This ambitious phase is radiocarbon dated to between 2440 and 2100 BC.

Stonehenge 3 III

Later in the Bronze Age, the bluestones appear to have been re-erected for the first time, although the exact details of this period are still unclear. They were placed within the outer sarsen circle and at this time may have been trimmed in some way. A few have timber working-style cuts in them like the sarsens themselves, suggesting they may have been linked with lintels and part of a larger structure during this phase.

Stonehenge 3 IV (2280 BC to 1930 BC)

This phase saw further rearrangement of the bluestones as they were placed in a circle between the two settings of sarsens and in an oval in the very centre. Some archaeologists argue that some of the bluestones in this period were part of a second group brought from Wales. All the stones were well-spaced uprights without any of the linking lintels inferred in Stonehenge 3 III. The Altar Stone may have been moved within the oval and stood vertically. Although this would seem the most impressive phase of work, Stonehenge 3 IV was rather shabbily built compared to its immediate predecessors, the newly re-installed bluestones were not at all well founded and began to fall over. However, only minor changes were made after this phase. Stonehenge 3 IV dates from 2280 to 1930 BC.

Stonehenge 3 V (2280 BC to 1930 BC)

Soon afterwards, the north eastern section of the Phase 3 IV Bluestone circle was removed, creating a horseshoe-shaped setting termed the Bluestone Horseshoe. This mirrored the shape of the central sarsen Trilithons and dates from 2270 to 1930 BC. This phase is contemporary with the famous Seahenge site in Norfolk.

After the monument (1600 BC on)

Even though the last known construction of Stonehenge was about 1600 BC, and the last known usage of it was during the Iron Age (if not as late as the 7th century), where Roman coins, prehistoric pottery, an unusual bone point and a skeleton of a young male (780-410 cal BC) were found, we have no idea if Stonehenge was in continuous use or exactly how it was used. Notable is the late 7th-6th century BC large arcing Scroll Trench which deepens E-NE towards Heelstone, and the burial of a decapitated Saxon man excavated from Stonehenge dated to the 7th century. The site was known by scholars during the Middle Ages and since then it has been studied and adopted by numerous different groups.

Theories about Stonehenge

Main article: Theories about StonehengeMyths and legends

“Friar’s Heel” or the “Sunday Stone”

The Heel Stone was once known as “Friar’s Heel”. A folk tale, which cannot be dated earlier than the seventeenth century, relates the origin of the name of this stone:

The Devil bought the stones from a woman in Ireland, wrapped them up, and brought them to Salisbury plain. One of the stones fell into the Avon, the rest were carried to the plain. The Devil then cried out, “No-one will ever find out how these stones came here.” A friar replied, “That’s what you think!,” whereupon the Devil threw one of the stones at him and struck him on the heel. The stone stuck in the ground and is still there.

Some claim “Friar’s Heel” is a corruption of “Freyja’s He-ol” or “Freyja Sul”, from the Nordic goddess Freyja and (allegedly) the Welsh words for “way” and “Friday” respectively.

Arthurian legend

Stonehenge is also mentioned within Arthurian legend. Geoffrey of Monmouth said that Merlin the wizard directed its removal from Ireland, where it had been constructed on Mount Killaraus by Giants, who brought the stones from Africa. After it had been rebuilt near Amesbury, Geoffrey further narrates how first Ambrosius Aurelianus, then Uther Pendragon, and finally Constantine III, were buried inside the ring of stones. In many places in his Historia Regum Britanniae Geoffrey mixes British legend and his own imagination; it is intriguing that he connects Ambrosius Aurelianus with this prehistoric monument, seeing how there is place-name evidence to connect Ambrosius with nearby Amesbury.

According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, the rocks of Stonehenge were healing rocks which Giants brought from Africa to Ireland for their healing properties. Aurelius Ambrosias (5th Century), wishing to erect a memorial to the nobles (3000) who had died in battle with the Saxons and were buried at Salisbury, chose (at Merlin's advice) Stonehenge to be their monument. So the King sent Merlin, Uther Pendragon (Arthur's father), and 15,000 knights to Ireland to retrieve the rocks. They slew 7,000 Irish. As the knights tried to move the rocks with ropes and force, they failed. Then Merlin, using "gear" and skill, easily dismantled the stones and sent them over to Britain, where Stonehenge was dedicated. Shortly after, Aurelius died and was buried within the Stonehenge monument, or "The Giants' Ring of Stonehenge".

Recent history

By the beginning of the 20th century a number of the stones had fallen or were leaning precariously, probably due to the increase in curious visitors clambering on them during the nineteenth century. Three phases of conservation work were undertaken which righted some unstable or fallen stones and carefully replaced them in their original positions using information from antiquarian drawings.

In 1915 Cecil Chubb bought Stonehenge, through Knight Frank & Rutley estate agents, for £6,000 as a present for his wife. She gave it to the nation three years later.

Stonehenge is a place of pilgrimage for neo-druids and those following pagan or neo-pagan beliefs. The midsummer sunrise began attracting modern visitors in 1870s, with the first record of recreated Druidic practices dating to 1905 when the Ancient Order of Druids enacted a ceremony. Despite efforts by archaeologists and historians to stress the differences between the Iron Age Druidic religion and the much older monument, Stonehenge has become increasingly, almost inextricably, associated with British Druidism, Neo Paganism and New Age philosophy. After the Battle of the Beanfield in 1985 this use of the site was stopped for several years, and currently ritual use of Stonehenge is carefully controlled.

In more recent years, the setting of the monument has been affected by the proximity of the A303 road between Amesbury and Winterbourne Stoke, and the A344. In early 2003, the Department for Transport announced that the A303 would be upgraded, including the construction of the Stonehenge road tunnel. The controversial plans have not yet been finalised by the government.

See also

- Avebury

- Battle of the Beanfield

- Durrington Walls

- European Megalithic Culture

- Excavations at Stonehenge

- Goloring

- Goseck circle

- Stonehenge replicas and derivatives

- Stone circle

- Stonehenge Historic Landscape

- Stonehenge in popular culture

- Stonehenge road tunnel

Bibliography

- Atkinson, R J C, Stonehenge (Penguin Books, 1956)

- Bender, B, Stonehenge: Making Space (Berg Publishers, 1998)

- Burl, A, Prehistoric Stone Circles (Shire, 2001)

- Chippendale, C, Stonehenge Complete (Thames and Hudson, London, 2004)

- Chippindale, C, et al, Who owns Stonehenge? (B T Batsford Ltd, 1990)

- Cleal, R. M. J., Walker, K. E. & Montague, R., Stonehenge in its Landscape (English Heritage, London, 1995)

- Cunliffe, B, & Renfrew, C, Science and Stonehenge (The British Academy 92, Oxford University Press, 1997)

- Hall, R, Leather, K, & Dobson, G, Stonehenge Aotearoa (Awa Press, 2005)

- Hawley, Lt-Col W, The Excavations at Stonehenge. (The Antiquaries Journal 1, Oxford University Press, 19-41). 1921.

- Hawley, Lt-Col W, Second Report on the Excavations at Stonehenge. (The Antiquaries Journal 2, Oxford University Press, 1922)

- Hawley, Lt-Col W, Third Report on the Excavations at Stonehenge. (The Antiquaries Journal 3, Oxford University Press, 1923)

- Hawley, Lt-Col W, Fourth Report on the Excavations at Stonehenge. (The Antiquaries Journal 4, Oxford University Press, 1923)

- Hawley, Lt-Col W, Report on the Excavations at Stonehenge during the season of 1923. (The Antiquaries Journal 5, Oxford University Press, 1925)

- Hawley, Lt-Col W, Report on the Excavations at Stonehenge during the season of 1924. (The Antiquaries Journal 6, Oxford University Press, 1926)

- Hawley, Lt-Col W, Report on the Excavations at Stonehenge during 1925 and 1926. (The Antiquaries Journal 8, Oxford University Press, 1928)

- Hutton, R, From Universal Bond to Public Free For All (British Archaeology 83, 2005)

- Mooney, J, Encyclopedia of the Bizarre (Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 2002)

- Newall, R S, Stonehenge, Wiltshire -Ancient monuments and historic buildings- (Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1959)

- North, J, Stonehenge: Ritual Origins and Astronomy (HarperCollins, 1997)

- Pitts, M, Hengeworld (Arrow, London, 2001)

- Pitts, M W, On the Road to Stonehenge: Report on Investigations beside the A344 in 1968, 1979 and 1980 (Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 48, 1982)

- Richards, J, English Heritage Book of Stonehenge (B T Batsford Ltd, 1991)

- Richards, J Stonehenge: A History in Photographs (English Heritage, London, 2004)

- Stone, J F S, Wessex Before the Celts (Frederick A Praeger Publishers, 1958)

- Worthington, A, Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion (Alternative Albion, 2004)

- English Heritage: Stonehenge: Historical Background

External links

- Stonehenge, a Temple Restor'd to the British Druids, by William Stukeley, at sacred-texts.com

- Stonehenge, and Other British Monuments Astronomically Considered, by Norman Lockyer, at sacred-texts.com

- After Stonehenge Phase 3

- Council for British Archaeology - The Stonehenge Saga

- English Heritage guide to Stonehenge

- Intute feature about Stonehenge Includes a podcast of an interview with archaeologists studying the site

- Great Buildings - Stonehenge

- National Trust - Stonehenge Historic Landscape

- The Bluestone Enigma

- Stonehenge, by Frank Stevens, 1916, from Project Gutenberg

- Ancient Monuments - Stonehenge

- Stonehenge-Avebury.net

- Stonehenge.co.uk

- Stonehenge Laser Scans

- Stonehenge on Google Maps

- Stonehenge Today/Yesterday - Diagrams and maps with explanations

- Stonehenge Photo Gallery - 90 photos

- The Stonehenge Project

- Stonehenge The Age of the Megaliths

51°10′44″N 1°49′35″W / 51.17889°N 1.82639°W / 51.17889; -1.82639

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories:- Stonehenge

- 4th millennium BC architecture

- 26th century BC architecture

- Arthurian locations

- Bronze Age sites in England

- Buildings and structures in Wiltshire

- National Trust properties in England

- History of Wiltshire

- Locations in Celtic mythology

- Megalithic monuments

- Ruins in England

- Scheduled Ancient Monuments in England

- Stone Age sites in England

- Visitor attractions in Wiltshire

- World Heritage Sites in England