| Revision as of 01:20, 16 October 2007 edit67.160.38.202 (talk) →Childhood victories← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:35, 17 October 2007 edit undoBrusegadi (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers7,059 editsm →Childhood victories: I suspect that is copy pasted.Next edit → | ||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

| === Childhood victories === | === Childhood victories === | ||

| After that incident Morphy's family recognized him as a precocious talent and encouraged him to play at family gatherings and local chess milieus. By the age of nine, he was considered one of the best players in New Orleans. In 1846, General ] visited the city, and let his hosts know that he desired an evening of chess with a strong local player. Chess was an infrequent pastime of Scott's, but he enjoyed the game and considered himself a formidable player. After dinner, the chess pieces were set up and Scott's opponent was brought in: diminutive, nine-year-old Morphy. Scott was at first offended, thinking he was being made fun of, but he consented to play after being assured that his wishes had been scrupulously obeyed and that the boy was a "chess prodigy" who would tax his skill. Morphy beat him easily not once, but twice, the second time announcing a forced checkmate after only six moves. As two losses against a small boy was all General Scott's ego could stand, he declined further games and retired for the night, never to play Morphy again. | |||

| In 1850, when Morphy was twelve, the strong professional Hungarian ] ] visited New Orleans. Löwenthal, who had often played and defeated talented youngsters, considered the informal match a waste of time but accepted the offer as a courtesy to the well-to-do judge. When Löwenthal met Morphy, he patted him on the head in a patronizing manner. | |||

| By about the twelfth move in the first game, Löwenthal realized he was up against something formidable. Each time Morphy made a good move, Löwenthal's eyebrows shot up in a manner described by Ernest Morphy as "comique". Löwenthal played three games with Morphy during his New Orleans stay, losing all three.<ref>One of the games was incorrectly given as a draw in Sergeant's ''Morphy's Games of Chess'' and was subsequently copied by sources since then. David Lawson's biography corrects this error, providing the moves that were actually played.</ref> | |||

| === Schooling and the First American Chess Congress=== | === Schooling and the First American Chess Congress=== | ||

Revision as of 01:35, 17 October 2007

| Paul Morphy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Full name | Paul Charles Morphy |

| Country | |

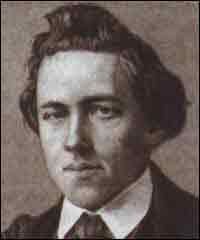

Paul Charles Morphy (June 22, 1837 - July 10, 1884), "The Pride and Sorrow of Chess," was an American chess player. He is considered to have been the greatest chess master of his era, one of the greatest of all time and an unofficial World Chess Champion. He was also one of the first chess prodigies in the modern rules of chess era.

Biography

Early life

Morphy was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, to a wealthy and distinguished family. His father, Alonzo Michael Morphy, a lawyer, served as a Louisiana state legislator, attorney general, and Supreme Court Justice. Alonzo was of Portuguese, Irish, and Spanish ancestry. Morphy's mother, Louise Thérèse Félicité Thelcide Le Carpentier, was the musically-talented daughter of a prominent French Creole family. Morphy grew up in an atmosphere of genteel civility and culture where chess and music were the typical highlights of a Sunday home gathering.

According to his uncle, Ernest Morphy, no one formally taught Morphy how to play chess; rather, Morphy learned on his own as a young child simply from watching others play. After watching a lengthy game between Ernest and Alonzo, young Paul surprised them by stating that Ernest should have won. Father and uncle had not realized that Paul even knew the moves, let alone any chess strategy. They were even more surprised when Paul proved his claim by resetting the pieces and demonstrating the win his uncle had missed. Later, a similar story was told about the Cuban chess prodigy José Raúl Capablanca.

Childhood victories

After that incident Morphy's family recognized him as a precocious talent and encouraged him to play at family gatherings and local chess milieus. By the age of nine, he was considered one of the best players in New Orleans. In 1846, General Winfield Scott visited the city, and let his hosts know that he desired an evening of chess with a strong local player. Chess was an infrequent pastime of Scott's, but he enjoyed the game and considered himself a formidable player. After dinner, the chess pieces were set up and Scott's opponent was brought in: diminutive, nine-year-old Morphy. Scott was at first offended, thinking he was being made fun of, but he consented to play after being assured that his wishes had been scrupulously obeyed and that the boy was a "chess prodigy" who would tax his skill. Morphy beat him easily not once, but twice, the second time announcing a forced checkmate after only six moves. As two losses against a small boy was all General Scott's ego could stand, he declined further games and retired for the night, never to play Morphy again.

In 1850, when Morphy was twelve, the strong professional Hungarian chess master Johann Löwenthal visited New Orleans. Löwenthal, who had often played and defeated talented youngsters, considered the informal match a waste of time but accepted the offer as a courtesy to the well-to-do judge. When Löwenthal met Morphy, he patted him on the head in a patronizing manner.

By about the twelfth move in the first game, Löwenthal realized he was up against something formidable. Each time Morphy made a good move, Löwenthal's eyebrows shot up in a manner described by Ernest Morphy as "comique". Löwenthal played three games with Morphy during his New Orleans stay, losing all three.

Schooling and the First American Chess Congress

After 1850, Morphy did not play much chess for a long time. Studying diligently, he graduated from Spring Hill College in Mobile, Alabama, in 1854. He then stayed on an extra year, studying mathematics and philosophy. He was awarded an A.M. degree with the highest honors.

He next was accepted to the University of Louisiana to study law. He received an L.L.B. degree on April 7, 1857, in preparation for which he is said to have memorized the complete Louisiana book of codes and laws.

Not yet of legal age to begin the practice of law, Morphy found himself with free time. He received an invitation to participate in the First American Chess Congress, to be held in New York in the fall of 1857. At first he declined, but at the urging of his uncle he eventually decided to play. He defeated each of his rivals, including the strong German master Louis Paulsen in the final round. Morphy was hailed as the chess champion of the United States, but he appeared unaffected by his sudden fame. According to the December 1857 issue of Chess Monthly, "his genial disposition, his unaffected modesty and gentlemanly courtesy have endeared him to all his acquaintances."

Morphy goes to Europe

Soon after returning to New Orleans he was invited to attend an international chess tournament to be held in Birmingham, England in the summer of 1858. Still too young to start his law career, he accepted the challenge and traveled to England. Instead of playing in the tournament, however, he ended up playing and easily winning a series of chess matches against all the leading English masters except the veteran Howard Staunton, who was well past his prime, and who initially promised a match but eventually declined after witnessing Morphy's play.

Staunton was later criticised for avoiding a match with Morphy. Staunton is known to have been working on his edition of the complete works of Shakespeare at the time, but he also competed in a chess tournament during Morphy's visit. Staunton later blamed Morphy for the failure to have a match, suggesting among other things that Morphy lacked the funds required for match stakes—a most unlikely charge given Morphy's popularity.

Seeking new opponents, Morphy crossed the English Channel to France. At the Café de la Regence in Paris, the center of chess in France, he played a match against Daniel Harrwitz, the resident chess professional, soundly defeating him.

In Paris Morphy suffered from a bout of intestinal influenza. In accordance with the medical wisdom of the time, he was treated with leeches, resulting in his losing a significant amount of blood. Although too weak to stand up unaided, Morphy insisted on going ahead with a match against the visiting German master Adolf Anderssen, considered by many to be Europe's leading player. Despite his illness Morphy triumphed easily, winning seven while losing two, with two draws. When asked about his defeat, Anderssen claimed to be out of practice, but also admitted that Morphy was in any event the stronger player and that he was fairly beaten. Anderssen also attested that in his opinion, Morphy was the strongest player ever to play the game, even stronger than the famous French champion La Bourdonnais.

Both in England and France, Morphy gave numerous simultaneous exhibitions, including displays of blindfold chess in which he regularly played and defeated eight opponents at a time. Morphy played a well-known casual game against the Duke of Brunswick and Count Isouard at the Italian Opera House in Paris.

Morphy is hailed as World Champion

Still only twenty-one, Morphy was now quite famous. While in Paris, he was sitting in his hotel room one evening, chatting with his companion Frederick Edge, when they had an unexpected visitor. "I am Prince Galitzine; I wish to see Mr. Morphy," the visitor said, according to Edge. Morphy identified himself to the visitor. "No, it is not possible!" the prince exclaimed, "You are too young!" Prince Galitzine then explained that he was in the frontiers of Siberia when he had first heard of Morphy's "wonderful deeds." He explained, "One of my suite had a copy of the chess paper published in Berlin, the Schachzeitung, and ever since that time I have been wanting to see you." He then told Morphy that he must go to St. Petersburg, Russia, because the chess club in the Imperial Palace would receive him with enthusiasm.

In Europe Morphy was generally hailed as world chess champion. In Paris, at a banquet held in his honor on April 4, 1859, a laurel wreath was placed over the head of a bust of Morphy, carved by the sculptor Eugene Lequesne. At a similar gathering in London, where he returned in the spring of 1859, Morphy was again proclaimed "the Champion of the World". He was also invited to a private audience with Queen Victoria. So dominant was Morphy that even masters could not seriously challenge him in play without some kind of handicap. At a simultaneous match against five masters (Jules Arnous de Rivière, Samuel Boden, Thomas Barnes, Johann Löwenthal, and Henry Bird), Morphy won two games, drew two games, and lost one.

Upon his return to America, the accolades continued as Morphy toured the major cities on his way home. At the University of the City of New York, on May 29, 1859, John Van Buren, son of President Martin Van Buren, ended a testimonial presentation by proclaiming, "Paul Morphy, Chess Champion of the World". In Boston, at a banquet attended by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Louis Agassiz, the mayor of Boston, the President of Harvard, and other luminaries, Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes toasted "Paul Morphy, the World Chess Champion". In short, Morphy was a celebrity. Manufacturers sought his endorsements, newspapers asked him to write chess columns, and a baseball club was named after him.

Morphy abandons chess

Having vanquished virtually all serious opposition, Morphy reportedly declared that he would play no more matches without giving odds of pawn and move. After returning home he declared himself retired from the game and, with a few exceptions, gave up public competition for good. Unfortunately, Morphy's embryonic law career was disrupted in 1861 by the outbreak of the American Civil War. Opposed to secession, Morphy did not serve in the Confederate Army. During the war he lived partly in New Orleans and partly abroad, spending time in Paris and Havana, Cuba.

Possibly because of his antiwar stance, Morphy was unable to successfully build a law practice even after the war ended. His attempts to open a law office failed; when he had visitors, they invariably wanted to talk about chess, not their legal affairs. Financially secure thanks to his family fortune, Morphy essentially spent the rest of his life in idleness. Asked by admirers to return to chess competition, he refused.

In accord with the prevailing sentiment of the time, Morphy esteemed chess only as an amateur activity, considering the game unworthy of pursuit as a serious occupation. Chess professionals were viewed in the same light as professional gamblers. It was not until decades later that the age of the professional chess player arrived.

Tragedy and twilight

On the afternoon of July 10, 1884, Morphy was found dead in his bathtub at the age of forty-seven. According to the autopsy, Morphy had suffered a stroke brought on by entering cold water after a long walk in the midday heat. The Morphy mansion, sold by the family in 1891, is today the site of Brennan's, a famous New Orleans restaurant.

Morphy's chess play

Today many amateurs think of Morphy as a dazzling combinative player, who excelled in sacrificing his Queen and checkmating his opponent a few brilliant moves later. One reason for this impression is that chess books like to reprint his flashy games. There are games where he did do this, but it was not the basis of his chess style. In fact, the masters of his day considered his style to be on the conservative side compared to some of the flashy older masters like La Bourdonnais and even Anderssen.

Morphy can be considered the first modern player. Some of his games do not look modern because he did not need the sort of slow positional systems that modern grandmasters use, or that Staunton, Paulsen, and later Steinitz developed. His opponents had not yet mastered the open game, so he played it against them and he preferred open positions because they brought quick success. He played open games almost to perfection, but he also could handle any sort of position, having a complete grasp of chess that was years ahead of his time. Morphy was a player who intuitively knew what was best, and in this regard he has been likened to Capablanca. He was, like Capablanca, a child prodigy; he played fast and he was hard to beat. Löwenthal and Anderssen both later remarked that he was indeed hard to beat since he knew how to defend and would draw or even win games despite getting into bad positions. At the same time, he was deadly when given a promising position. Anderssen especially commented on this, saying that after one bad move against Morphy one may as well resign. "I win my games in seventy moves but Mr. Morphy wins his in twenty, but that is only natural..." Anderssen said, explaining his poor results against Morphy.

Of Morphy's 59 "serious" games — those played in matches and the 1857 New York tournament — he won 42, drew 9, and lost 8.

Some chess grandmasters consider Morphy to have been the greatest chess player who ever lived. Others have disagreed with the more extreme claims.

Notable chess games

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

- Louis Paulsen vs Paul Morphy, New York 1857, Four Knights Game: Spanish. Classical Variation (C48), 0-1 Morphy's queen sacrifice transforms his positional pressure into a decisive attack on Paulsen's king.

- Paul Morphy vs Duke Karl of Brunswick / Count Isouard, Paris 1858, Philidor Defense: General (C41), 1-0 The "Opera game" - a casual game against unexperienced opponents, but at the same time one of the clearest and most beautiful attacking games ever. Often used by chess teachers to demonstrate how to use time, develop pieces and generate threats.

- Paul Morphy vs Adolf Anderssen, Casual Game 1858, King's Gambit: Accepted. Kieseritsky Gambit Berlin Defense (C39), 1-0 Morphy loved open positions. In this game, one can see how he used to win in such positions.

Notes

- According to David Lawson, in Paul Morphy, The Pride and Sorrow of Chess, Mckay, 1976. Lawson says that Morphy was the first world champion to be so acclaimed at the time he was playing. Most chess historians, however, place the first official world chess championship in 1886, and so regard Morphy as having been the unofficial world champion when he soundly defeated Adolf Anderssen by 8 to 3. Morphy is considered the world's leading player between 1858 and 1861.

- One of the games was incorrectly given as a draw in Sergeant's Morphy's Games of Chess and was subsequently copied by sources since then. David Lawson's biography corrects this error, providing the moves that were actually played.

- According to Macon Shibut in Paul Morphy and the Evolution of Chess Theory, Staunton did play two consultation games against Morphy, losing both. Shibut also reports that in private letters Staunton conceded that the younger man was the stronger player.

- In a match between two evenly matched Masters, a pawn advantage is considered a winning advantage.

- Even as their reputation improved, however, chess professionals found it extremely difficult (as they do today) to support themselves by chess alone.

- Jeremy Silman's Chess Page has comments from Fischer on Morphy.

- " glorifiers went on to urge that he was the most brilliant genius who had ever appeared. ... But if we examine Morphy's record and games critically, we cannot justify such extravaganza. And we are compelled to speak of it as the Morphy myth. ... Even if the myth has been destroyed, Morphy remains one of the giants of chess history." - Reuben Fine; see reading list.

- "Discussions of who was the greatest ever player are always fun, but naturally will often collapse into partisan declarations of faith or endless gnawing at historical bones of diverse provenance." - Raymond Keene; World Chess Championship: Kramnik vs. Leko (page 73); Hardinge Simpole Publishing; 2004. ISBN 1-84382-160-5. Algebraic notation.

References

- Paul Morphy, The Pride and Sorrow of Chess by David Lawson, 424 pages; Mckay,1976 - This is the only book-length biography of Paul Morphy in English. It is out of print, but corrects numerous historical mistakes that have cropped up about Paul Morphy, including the one about Morphy's score as a child versus Löwenthal.

- Frederick Milne Edge: Paul Morphy, the Chess Champion. An Account of His Career in America and Europe. New York 1859- Edge was a newspaperman who attached himself to Morphy during his stay in England and France, accompanying Morphy everywhere, and even acting at times as his unofficial butler and servant. Thanks to Edge, much is known about Morphy that would be unknown otherwise, and many games Morphy played were recorded only thanks to Edge. Contains information about the First American Chess Congress, and the history of English chess clubs in and before Morphy's time.

Further reading

- Paul Morphy and the Evolution of Chess Theory by Macon Shibut, Caissa Editions 1993 ISBN 0-939433-16-8 Over 415 games comprising almost all known Morphy games. Chapters on Morphy's place in the development of chess theory, and reprinted articles about Morphy by Steinitz, Alekhine, and others.

- The Chess Genius of Paul Morphy by Max Lange (translated from the original German into English by Ernst Falkbeer), 1860. Reprinted by Moravian Chess under the title, "Paul Morphy, a sketch from the chess world." An excellent resource for the European view of Morphy as well as for its biographical information. The English edition was reviewed in Chess Player's Chronicle 1859.

- Grandmasters of Chess by Harold Schonberg, Lippincott, 1973. ISBN 0-397-01004-4

- World chess champions by Edward G. Winter, editor. 1981 ISBN 0-08-024094-1, leading chess historians include Morphy as one of the world champions.

- Morphy's Games of Chess by Philip W. Sergeant & Fred Reinfeld, Dover; June 1989. ISBN 0-486-20386-7, Features annotations collected from previous commentators, as well as additions by Sergeant. Has all of Morphy's match, tournament, and exhibition games, and most of his casual and odds games. Short biography included.

- Morphy Gleanings by Philip W. Sergeant, David McKay company; 1932. Contributes games not found in Sergeant's earlier work, "Morphy's Games of Chess" and features greater biographical information as well as documentation into the Morphy-Paulsen and the Morphy-Kolisch affairs. Reprinted under the title, "Unknown Morphy."

- The World's Great Chess Games by Reuben Fine; Dover; 1983. ISBN 0-486-24512-8

- A First Book of Morphy by Frisco Del Rosario; Trafford; October 2004. ISBN 1-4120-3906-1, Illustrates the teachings of Cecil Purdy and Reuben Fine with 65 annotated games played by the American champion. Algebraic notation.

- Paul Morphy: A Modern Perspective by Valeri Beim; Russell Enterprises, Inc.; 2005. ISBN 1-888690-26-7. Algebraic notation.

- Life of Paul Morphy in the Vieux Carré of New-Orleans and Abroad by Regina Morphy-Voitier, 1926. Regina Morphy-Voitier, the niece of Paul Morphy, self-published this pamphlet in New York. Its value lies in its insight into Paul Morphy's life in the Vieux Carré.

- The Chess Players by Frances Parkinson Keyes, Farrar, Straus and Cudahy; 1960. A work of historical fiction in which Morphy is the central character.

- "Paul Morphy A Historical Character" . Chess Player's Chronicle. Third Series: p.40. 1860.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help)

External links

- Paul Morphy player profile and games at Chessgames.com

- Morphy's column for the New York Ledger in 1859

- United States Chess Federation's US Chess Hall of Fame - Paul Morphy

- A.J.'s 'Paul Morphy' Web Page

- Paulsen vs Morphy multimedia annotated game

| Preceded byCharles Stanley | United States Chess Champion 1857–1871 |

Succeeded byGeorge H. Mackenzie |