| Revision as of 00:45, 3 February 2008 editCla68 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers48,127 edits restored paragraph that sumarizes classification section← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:14, 3 February 2008 edit undoTimVickers (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users58,184 edits Restore improved categorisation that was lost in the last revertNext edit → | ||

| Line 294: | Line 294: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 01:14, 3 February 2008

Animal testing or animal research refers to the use of non-human animals in experiments. It is estimated that 50 to 100 million vertebrate animals worldwide — from zebrafish to non-human primates — are used annually and killed during or after the experiments. Although much larger numbers of invertebrates are used and the use of flies and worms as model organisms is important in research, experiments on invertebrates are largely unregulated and not included in statistics. The research is carried out inside universities, medical schools, pharmaceutical companies, farms, defense-research establishments, and commercial facilities that provide animal-testing services to industry. Sources of laboratory animals vary between countries and species; while some species are purpose-bred, other animals may be caught in the wild or supplied by dealers who obtain them from auctions and pounds.

Animal testing classifications include pure and applied research, Xenotransplantation, and toxicology, cosmetics, and drug testing. Animals are also used for education, breeding, and defense research.

The topic is highly controversial. Supporters of the practice, such as the British Royal Society, argue that virtually every medical achievement in the 20th century relied on the use of animals in some way, with the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences arguing that even sophisticated computers are unable to model interactions between molecules, cells, tissues, organs, organisms, and the environment, making animal research necessary in some areas. Opponents, such as the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection, question the necessity of it, arguing further that it is cruel, poor scientific practice, never reliably predictive of human metabolic and physiological specificities, poorly regulated, that the costs outweigh the alleged benefits, or that animals have an intrinsic right not to be used for experimentation.

Definitions

The terms animal testing, animal experimentation, animal research, in vivo testing, and vivisection have similar denotations but different connotations. Literally, "vivisection" means the "cutting up" of a living animal, and historically referred only to experiments that involved the dissection of live animals. The term is now used by some to refer to any experiment using living animals; for example, the Encyclopaedia Britannica defines "vivisection" as: "Operation on a living animal for experimental rather than healing purposes; more broadly, all experimentation on live animals." For others, the word has a pejorative connotation, implying torture and suffering. The word "vivisection" is preferred by those opposed to this research, whereas scientists typically use the term "animal experimentation."

History

Main article: History of animal testing

The earliest references to animal testing are found in the writings of the Greeks in the second and fourth centuries BCE. Aristotle (Αριστοτέλης) (384-322 BCE) and Erasistratus (304-258 BCE) were among the first to perform experiments on living animals (Cohen and Loew 1984). Galen, a physician in second-century Rome, dissected pigs and goats, and is known as the "father of vivisection."

Animals have played a role in numerous well-known experiments. In the 1880s, Louis Pasteur convincingly demonstrated the germ theory of medicine by giving anthrax to sheep. In the 1890s, Ivan Pavlov famously used dogs to describe classical conditioning. Insulin was first isolated from dogs in 1922, and revolutionized the treatment of diabetes. On November 3, 1957 a Russian dog, Laika, became the first of many animals to orbit the earth. In the 1970s, leprosy multi-drug antibiotic treatments were developed first in armadillos, then in humans. In 1996 Dolly the sheep was born, the first mammal to be cloned from an adult cell.

As the experimentation on animals increased, especially the practice of vivisection, so did criticism and controversy. In 1655, physiologist Edmund O'Meara is recorded as saying that "the miserable torture of vivisection places the body in an unnatural state." O'Meara and others argued that animal physiology could be affected by the pain and suffering of vivisection, rendering the results unreliable. There were also objections on an ethical basis, contending that the benefit to humans did not justify the harm to animals. Early objections to animal testing also came from another angle — many people believed that animals are inferior to humans and thus so different that any results obtained from animals would be inapplicable to humans.

On the other side of the debate, those in favor of animal testing held that experiments on living animals were necessary to advance medical and biological knowledge. Claude Bernard, known as the "prince of vivisectors" and the father of physiology, famously wrote in 1865 that "the science of life is a superb and dazzlingly lighted hall which may be reached only by passing through a long and ghastly kitchen". Arguing that "experiments on animals ... are entirely conclusive for the toxicology and hygiene of man ... for as I have shown, the effects of these substances are the same on man as on animals, save for differences in degree," Bernard established the paradigm of animal experimentation in scientific method that is largely followed by the scientific community today. Bernard's wife, Marie Françoise Martin, was a fervent anti-vivisectionist, and in 1883 founded the first anti-vivisection society in France.

In 1822, the first animal protection law was enacted in the British parliament, followed by the Cruelty to Animals Act (1876), the first law specifically aimed at regulating animal testing. The legislation was promoted by Charles Darwin, who wrote to Ray Lankester in March 1871: "You ask about my opinion on vivisection. I quite agree that it is justifiable for real investigations on physiology; but not for mere damnable and detestable curiosity. It is a subject which makes me sick with horror, so I will not say another word about it, else I shall not sleep to-night."

The growing division between the pro- and anti- animal testing factions first came to dramatic public attention during the Brown Dog riots that raged in the early 1900s in the streets of London, when hundreds of medical students clashed with anti-vivisectionists and police over a memorial to a vivisected dog.

Animals used

See also: Animal testing regulationsNumbers

Accurate global figures for animal testing are difficult to obtain. The British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV) estimates that 100 million vertebrates are experimented on around the world every year, 10–11 million of them in the European Union. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics reports that global annual estimates range from 50 to 100 million animals.

None of the figures, including those given in this article, include invertebrates, such as shrimp and fruit flies. Animals bred for research then killed as surplus, animals used for breeding purposes, and animals not yet weaned (which most laboratories do not count) are also not included in the figures.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the total number of animals used in that country in 2005 was almost 1.2 million, not including rats, mice, birds, fish, or frogs, which jointly make up 85% of research animals. The Laboratory Primate Advocacy Group has used the USDA's figures to estimate that 23-25 million vertebrate animals are used in research each year in America. In 1995, researchers at Tufts University Center for Animals and Public Policy estimated that 14-21 million animals were used in American laboratories in 1992, a reduction from a high of 50 million used in 1970. In 1986, the U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment reported that estimates of the animals used in the U.S. range from 10 million to upwards of 100 million each year, and that their own best estimate was at least 17 million to 22 million.

In the UK, Home Office figures show that nearly three million procedures were carried out in 2004 on just under the same number of animals. It is the third consecutive annual rise and the highest figure since 1992. Most animals are used in only one procedure: animals either die because of the experiment or are euthanized afterwards. A "procedure" refers to an experiment that might last minutes, several months, or years.

|

|

|

|

|

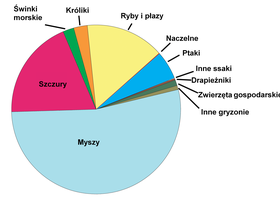

Species

- Invertebrates

Although much larger numbers of invertebrates than vertebrates are used, these experiments are largely unregulated by law and are therefore not included in statistics. The most used invertebrate species are Drosophila melanogaster, a fruit fly, and Caenorhabditis elegans, a nematode worm. In the case of C. elegans, the precise lineage of all the organism's cells is known, and D. melanogaster is very well-suited to genetic studies. These animals offer great advantages over vertebrates, including their short life cycle and the ease with which large numbers may be studied, with thousands of flies or nematodes fitting into a single room. However, the lack of an adaptive immune system and their simple organs prevents worms from being used in medical research such as vaccine development. Similarly, flies are not widely used in applied medical research, as their immune system differs greatly from that of humans, and diseases in insects can be very different from diseases in more complex animals.

- Rodents, fish, and rabbits

In the U.S., the numbers of rats and mice used is estimated at 15-20 million a year. Other rodents commonly used are guinea pigs, hamsters, and gerbils. Mice are the most commonly used vertebrate species because of their size, low cost, ease of handling, and fast reproduction rate. Mice are widely considered to be the best model of inherited human disease and share 99% of their genes with humans. With the advent of genetic engineering technology, genetically modified mice can be generated to order and can cost hundreds of dollars each.

Nearly 200,000 fish and 20,000 amphibians were used in the UK in 2004. The main species used is the zebrafish, Danio rerio, which are translucent during their embryonic stage, and the African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis. Over 20,000 rabbits were used for animal testing in the UK in 2004. Albino rabbits are used in eye irritancy tests because rabbits have less tear flow than other animals, and the lack of eye pigment make the effects easier to visualize.

- Cats and dogs

Cats are most commonly used in neurological research. Over 25,500 cats were used in the U.S. in 2000, around half of whom were used in experiments that caused "pain and/or distress".

Dogs are widely used in biomedical research, testing, and education — particularly beagles, because they are gentle and easy to handle. They are commonly used as models for human diseases in cardiology, endocrinology, and bone and joint studies, research that tends to be highly invasive, according to the Humane Society of the United States. The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Animal Welfare Report for 2004 shows that nearly 65,000 dogs were used in USDA-registered facilities in that year. In the U.S., some of the dogs are purpose-bred, while most are supplied by so-called Class B dealers licensed by the USDA to buy animals from auctions, shelters, newspaper ads, and who are sometimes accused of stealing pets.

- Non-human primates

Non-human primates (NHPs) are used in toxicology tests, studies of AIDS and hepatitis, studies of neurology, behavior and cognition, reproduction, genetics, and xenotransplantation. They are caught in the wild, taken from zoos, circuses and animal trainers, or purpose-bred. The primates used in the USA, China, and Europe are mostly purpose-bred. In the U.S. and China, most primates are domestically purpose-bred, whereas in Europe the majority are imported purpose-bred. Rhesus monkeys, cynomolgus monkeys, squirrel monkeys, and owl monkeys are imported; around 12,000 to 15,000 monkeys are imported into the U.S. annually. Around 65,000 NHPs are used each year in the United States and European Union. Most of the NHPs used are macaques; but marmosets, spider monkeys, and squirrel monkeys are also used, and baboons and chimpanzees are used in the U.S; there are currently 1133 chimpanzees in U.S. research laboratories. Notable studies on non-human primates have been part of the polio vaccine development, and development of Deep Brain Stimulation, and their current heaviest non-toxicological use occurs in the monkey AIDS model, SIV.

Sources

Main articles: Laboratory animal sources and International trade in primatesAnimals used by laboratories are largely supplied by specialist dealers. Sources differ for vertebrate and invertebrate animals. Most laboratories breed and raise flies and worms themselves, using strains and mutants supplied from a few main stock centers. For vertebrates, sources include breeders who supply purpose-bred animals; businesses that trade in wild animals; and dealers who supply animals sourced from pounds, auctions, and newspaper ads. Animal shelters also supply the laboratories directly. Large centers also exist to distribute strains of genetically-modified animals; the National Institutes of Health Knockout Mouse Project, for example, aims to provide knockout mice for every gene in the mouse genome.

In the U.S., Class A breeders are licensed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to sell animals for research purposes, while Class B dealers are licensed to buy animals from "random sources" such as auctions, pound seizure, and newspaper ads. Some Class B dealers have been accused of kidnapping pets and illegally trapping strays, a practice known as bunching. It was in part out of public concern over the sale of pets to research facilities that the 1966 Laboratory Animal Welfare Act was ushered in — the Senate Committee on Commerce reported in 1966 that stolen pets had been retrieved from Veterans Administration facilities, the Mayo Institute, the University of Pennsylvania, Stanford University, and Harvard and Yale Medical Schools. The USDA recovered at least a dozen stolen pets during a raid on a Class B dealer in Arkansas in 2003.

Four states in the U.S. — Minnesota, Utah, Oklahoma, and Iowa — require their shelters to provide animals to research facilities. Fourteen states explicitly prohibit the practice, while the remainder either allow it or have no relevant legislation.

In the European Union, animal sources are governed by Council Directive 86/609/EEC, which requires lab animals to be specially bred, unless the animal has been lawfully imported and is not a wild animal or a stray. The latter requirement may also be exempted by special arrangement. In the UK, most animals used in experiments are bred for the purpose under the 1988 Animal Protection Act, but wild-caught primates may be used if exceptional and specific justification can be established. The United States also allows the use of wild-caught primates; between 1995 and 1999, 1,580 wild baboons were imported into the U.S. Over half the primates imported between 1995 and 2000 were handled by Charles River Laboratories, Inc. — former owners of Shamrock Farm in the UK — and Covance, the single largest importer of primates in the U.S. and the world's largest breeder of laboratory dogs.

Research classification

| Animal testing |

|---|

|

| Main articles |

| Testing on |

| Issues |

| Cases |

| Companies |

| Groups/campaigns |

|

| Writers/activists |

| Categories |

Pure research

Basic or pure research investigates how organisms behave, develop, and function. Those opposed to animal testing object that pure research may have little or no practical purpose, but researchers argue that it may produce unforeseen benefits, rendering the distinction between pure and applied research — research that has a specific practical aim — unclear.

Pure research uses larger numbers and a greater variety of animals than applied research. Fruit flies, nematode worms, mice and rats together account for the vast majority, though small numbers of other species are used, ranging from sea slugs through to armadillos.

Examples of the types of animals and experiments used in basic research include:

- Studies on embryogenesis and developmental biology. Mutants are created by adding transposons into their genomes, or specific genes are deleted by gene targeting. By studying the changes in development these changes produce, scientists aim to understand both how organisms normally develop, and what can go wrong in this process. These studies are particularly powerful since the basic controls of development, such as the homeobox genes, have similar functions in organisms as diverse as fruit flies and man.

- Experiments into behavior, to understand how organisms detect and interact with each other and their environment, in which fruit flies, worms, mice, and rats are all widely used. Studies of brain function, such as memory and social behavior, often use rats and birds. For some species, behavioral research is combined with enrichment strategies for animals in captivity because it allows them to engage in a wider range of activities.

- Breeding experiments to study evolution and genetics. Laboratory mice, flies, fish, and worms are inbred through many generations to create strains with defined characteristics. These provide animals of a known genetic background, an important tool for genetic analyses. Larger mammals are rarely bred specifically for such studies due to their slow rate of reproduction, though some scientists take advantage of inbred domesticated animals, such as dog or cattle breeds, for comparative purposes. Scientists studying how animals evolve use many animal species, including mosquitos, sticklebacks, and lampreys, to see how variations in where and how an organism lives (their niche) produce adaptations in their physiology and morphology.

Applied research

Applied research aims to solve specific and practical problems. Compared to pure research, which is largely academic in origin, applied research is usually carried out in the pharmaceutical industry, or by universities in commercial partnerships. These may involve the use of animal models of diseases or conditions, which are often discovered or generated by pure research programmes. In turn, such applied studies may be an early stage in the drug discovery process. Examples include:

- Genetic modification of animals to study disease. Transgenic animals have specific genes inserted, modified or removed, to mimic specific conditions such as single gene disorders, such as Huntington's disease. Other models mimic complex, multifactorial diseases with genetic components, such as diabetes, or even transgenic mice that carry the same mutations that occur during the development of cancer. These models allow investigations on how and why the disease develops, as well as providing ways to develop and test new treatments. The vast majority of these transgenic models of human disease are lines of mice, the mammalian species in which genetic modification is most efficient. Smaller numbers of other animals are also used, including rats, pigs, sheep, fish, birds, and amphibians.

- Studies on models of naturally occurring disease and condition. Certain domestic and wild animals have a natural propensity or predisposition for certain conditions that are also found in humans. Cats are used as a model to develop immunodeficiency virus vaccines and to study leukemia because their natural predisposition to FIV and Feline leukemia virus. Certain breeds of dog suffer from narcolepsy making them the major model used to study the human condition. Armadillos and humans are among only a few animal species that naturally suffer from leprosy; as the bacteria responsible for this disease cannot yet be grown in culture, armadillos are the primary source of bacilli used in leprosy vaccines.

Xenotransplantation

Main article: XenotransplantationXenotransplantation involves transplanting living cells, tissues, or organs from one species to another. Current research involves using primates as the recipients of pig's organs. The British Home Office released figures in 1999 showing that 270 monkeys had been used in xeno research there during the previous four years. Documents leaked from Huntingdon Life Sciences to The Observer in 2003 showed, between 1994 and 2000, wild baboons were imported to the UK from Africa to be used in experiments that involved grafting pigs' hearts and kidneys onto the primates' necks, abdomens, and chests. The Observer reports that some baboons died after suffering strokes, vomiting, diarrhea, and paralysis, while others died en route to the UK. The experiments were conducted by Imutran Ltd, a subsidiary of Novartis Pharma AG in conjunction with Cambridge University and Huntingdon Life Sciences. Novartis told the newspaper that developing new cures for humans invariably means experimenting on live animals.

The newspaper also wrote that researchers were deliberately underestimating the suffering in order to obtain licences. A report from Imutran said: "The Home Office will attempt to get the kidney transplants classified as 'moderate,' ensuring that it is easier for Imutran to receive a licence and ignoring the 'severe' nature of these programmes."

Toxicology testing

Main article: Toxicology testing Further information: Draize test, LD50, Acute toxicity, and Chronic toxicity|

|

|

|

Toxicology testing, also known as safety testing, is conducted by pharmaceutical companies testing drugs, or by contract animal testing facilities, such as Huntingdon Life Sciences, on behalf of a wide variety of customers. According to 2005 EU figures, around one million animals are used every year in Europe in toxicology tests; which are about 10% of all procedures. According to Nature, 5,000 animals are used for each chemical being tested, with 12,000 needed to test pesticides. The tests are conducted without anesthesia, because interactions between drugs can affect how animals detoxify chemicals, and may interfere with the results.

Toxicology tests are used to examine finished products such as pesticides, medications, food additives, packing materials, and air freshener, or their chemical ingredients. Most tests involve testing ingredients rather than finished products, but according to BUAV, manufacturers believe these tests overestimate the toxic effects of substances; they therefore repeat the tests using their finished products to obtain a less toxic label.

The substances are applied to the skin or dripped into the eyes; injected intravenously, intramuscularly, or subcutaneously; inhaled either by placing a mask over the animals and restraining them, or by placing them in an inhalation chamber; or administered orally, through a tube into the stomach, or simply in the animal's food. Doses may be given once, repeated regularly for many months, or for the lifespan of the animal.

There are several different types of acute toxicity tests. The LD50 ("Lethal Dose 50%") test is used to evaluate the toxicity of a substance by determining the dose required to kill 50% of the test animal population. This test was removed from OECD international guidelines in 2002, replaced by methods such as the fixed dose procedure, which use fewer animals and cause less suffering. Nature writes that, as of 2005, "the LD50 acute toxicity test ... still accounts for one-third of all animal tests worldwide."

Irritancy is usually measured using the Draize test, where a test substance is applied to an animal's eyes or skin, usually an albino rabbit. For Draize eye testing, the recommended protocol involves observing the effects of the substance at intervals and grading any damage or irritation, but that the test should be halted and the animal killed if it shows "continuing signs of severe pain or distress". The Humane Society of the United States writes that the procedure can cause redness, ulceration, hemorrhaging, cloudiness, or even blindness. This test has also been criticized by scientists for being cruel and inaccurate, subjective, over-sensitive, and failing to reflect human exposures in the real world. Although no accepted in vitro alternatives exist, a modified form of the Draize test called the low volume eye test may reduce suffering and provide more realistic results, but it has not yet replaced the original test.

The most stringent tests are reserved for drugs and foodstuffs. For these, a number of tests are performed, lasting less than a month (acute), one to three months (subchronic), and more than three months (chronic) to test general toxicity (damage to organs), eye and skin irritancy, mutagenicity, carcinogenicity, teratogenicity, and reproductive problems. The cost of the full complement of tests is several million dollars per substance and it may take three or four years to complete.

These toxicity tests provide, in the words of a 2006 United States National Academy of Sciences report, "critical information for assessing hazard and risk potential". However, as Nature reported, most animal tests either over- or underestimate risk, or or do not reflect toxicity in humans particularly well. This variability stems from using the effects of high doses of chemicals in small numbers of laboratory animals to try to predict the effects of low doses in large numbers of humans. Although relationships do exist, opinion is divided on how to use data on one species to predict the exact level of risk in another.

Cosmetics testing

Cosmetics testing on animals is particularly controversial. Such tests, which are still conducted in the U.S., involve general toxicity, eye and skin irritancy, phototoxicity (toxicity triggered by ultraviolet light) and mutagenicity.

Cosmetics testing is banned in the Netherlands, Belgium, and the UK, and in 2002, after 13 years of discussion, the European Union (EU) agreed to phase in a near-total ban on the sale of animal-tested cosmetics throughout the EU from 2009, and to ban all cosmetics-related animal testing. France, which is home to the world's largest cosmetics company, L'Oreal, has protested the proposed ban by lodging a case at the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg, asking that the ban be quashed. The ban is also opposed by the European Federation for Cosmetics Ingredients, which represents 70 companies in Switzerland, Belgium, France, Germany and Italy.

Drug testing

Before the early 20th century, laws regulating drugs were lax. For example, in the U.S., the government could only ban a drug after a company had been prosecuted for selling products that harmed customers. However, in response to a tragedy where a drug labeled “Elixir of Sulfanilamide” killed 73 people, the U.S. congress passed laws that required safety testing of drugs, before they could be marketed. Nowadays all new pharmaceuticals undergo rigorous animal testing before being licensed for human use. Tests on pharmaceutical products involve:

- metabolic tests, investigating pharmacokinetics - how drugs are absorbed, metabolized and excreted by the body when introduced orally, intravenously, intraperitoneally, intramuscularly, or transdermally.

- toxicology tests, which gauge acute, sub-acute, and chronic toxicity. Acute toxicity is studied by using a rising dose until signs of toxicity become apparent. Current European legislation demands that "acute toxicity tests must be carried out in two or more mammalian species" covering "at least two different routes of administration". Sub-acute toxicity is where the drug is given to the animals for four to six weeks in doses below the level at which it causes rapid poisoning, in order to discover if any toxic drug metabolites build up over time. Testing for chronic toxicity can last up to two years and, in the European Union, is required to involve two species of mammals, one of which must be non-rodent.

- efficacy studies, which test whether experimental drugs work by inducing the appropriate illness in animals. The drug is then administered in a double-blind controlled trial, which allows researchers to determine the effect of the drug and the dose-response curve.

- Specific tests on reproductive function, embryonic toxicity, or carcinogenic potential can all be required by law, depending on the result of other studies and the type of drug being tested.

Education, breeding, and defense research

Animals are also used for education and training; are bred for use in laboratories; and are used by the military to develop weapons, vaccines, battlefield surgical techniques, and defensive clothing.

There are efforts in many countries to find alternatives to using animals in education. Horst Spielmann, German director of the Central Office for Collecting and Assessing Alternatives to Animal Experimentation, while describing Germany's progress in this area, told German broadcaster ARD in 2005: "Using animals in teaching curricula is already superfluous. In many countries, one can become a doctor, vet or biologist without ever having performed an experiment on an animal."

Pain and suffering

Further information: Animal cognitionThe extent to which animal testing causes pain and suffering, and the capacity of animals to experience and comprehend them, is the subject of much debate.

In discussing the issue of suffering in laboratory animals, Marian Stamp Dawkins defines it as "experiencing one of a wide range of extremely unpleasant subjective (mental) states." The USDA defines a "painful procedure" in an animal study as one that would "reasonably be expected to cause more than slight or momentary pain or distress in a human being to which that procedure was applied."

In the U.S. in 2004, over 600,000 animals (not including rats, mice, birds, or invertebrates) were used in procedures that, according to the Animal Care Committees of the institutions conducting the research, did not include more than momentary pain or distress. Nearly 400,000 were used in procedures in which pain or distress was relieved by anesthesia, while 87,000 were used in studies in which researchers planned to cause pain or distress that would not be relieved.

In the UK, research projects are classified as mild, moderate, and substantial in terms of the suffering the researchers conducting the study say they may cause; a fourth category of "unclassified" means the animal was anesthetized and killed without recovering consciousness, according to the researchers. In December 2001, 39 percent (1,296) of project licences in force were classified as mild, 55 percent (1,811) as moderate, two percent (63) as substantial, and 4 percent (139) as unclassified. The Observer wrote in 2003 that the British Home Office worked with Imutran Ltd, a subsidiary of Novartis Pharma AG, to underestimate suffering in order to obtain licences to conduct kidney transplants on non-human primates. A report from the company said: "The Home Office will attempt to get the kidney transplants classified as 'moderate,' ensuring that it is easier for Imutran to receive a licence and ignoring the 'severe' nature of these programmes."

Larry Carbone, a laboratory animal veterinarian with the University of California, San Francisco, writes that the idea that animals might not feel pain as human beings do traces back to the 17th-century French philosopher, René Descartes, who argued that they do not experience pain and suffering because they lack rationality. Non-human animals were non-sentient automata, a view summed up by Nicolas Malebranche, who wrote that they "eat without pleasure, cry without pain, grow without knowing it; they desire nothing, fear nothing, know nothing." Animal researchers from this period reportedly took these words to heart; Carbone cites Nicholas Fontaine who wrote that they "administered beatings to dogs with perfect indifference, and made fun of those who pitied the creatures as if they felt pain."

Bernard Rollin, a philosopher and professor of Animal Sciences at Colorado State University, and the principal author of two U.S. federal laws regulating pain and distress relief for animals, writes that, until the 1980s, researchers continued to deny that animals experience pain as human beings experience it. Veterinarians trained in the U.S. before 1989 were taught to ignore pain. He writes that at least one major veterinary hospital in the 1960s did not stock narcotic analgesics for animal pain control, or even request a licence to do so, and quotes an associate dean of a veterinary college, who argued that "anesthesia and analgesia have nothing to with pain; they are methods of chemical restraint." In his interactions with scientists and other veterinarians, he was regularly asked to "prove" that animals are conscious, and to provide "scientifically acceptable" grounds for claiming that they feel pain. Anyone who raised the issue of animal suffering, he writes, was stigmatized as a misanthrope who preferred animals to human beings. It was not until the 1985 Health Research Extension Act, drafted by Rollin, that pain and distress control for laboratory animals was regulated.

Carbone writes that the view that animals feel pain differently in now a minority view, and that radical theories that fly in the face of common sense — for example, that animals lack consciousness — find little acceptance. Academic reviews of the topic are more equivocal, noting that although the argument that animals have at least simple conscious thoughts and feelings has strong support, some critics still question the validity of such theories. The majority of researchers do accept that animals feel pain, although at an individual level, Carbone has often experienced researchers denying that particular animals are in pain, even when they are standing together watching the animal's response to a scalpel or needle. He writes that the problem of animal pain arises because the animal has no clear way of communicating it, which has led to what he calls the "scientization" of pain, where researchers attempt to reduce it to a physical and identifiable quality, rather than the subjective experience a layperson would describe. They use a particular language to describe it, writing for example that "x was aversive at all concentrations," instead of "x seemed to be in pain no matter the dose." Carbone writes that the purpose of this "scientization" is both to find more objective ways to measure pain, but also to establish the scientists' credentials as the group best placed to identify it, in order to retain a degree of political and legal control over how pain is regulated.

According to Carbone, researchers may remain reluctant to dispense pain medication for a number of reasons. He writes that anesthetics and analgesics are expensive, and that many are controlled narcoleptics that require extensive record keeping, licencing, and — in the U.S. — Drug Enforcement Administration inspections. Correctly used, they would require round-the-clock attendance on the animals, and redosing every few hours. They have side effects, such as respiratory depression, intestinal problems, and decreased blood clotting that could impact on the research variables. There are also studies where the assessment of pain is part of the research; for example, if arthritis is induced in a group of animals in order to test a painkiller, a control group with arthritis but with no pain control is needed for the sake of comparison. Carbone further argues that researchers raised in the era of increased awareness of animal welfare may be inclined to deny that animals are in pain simply because they do not want to see themselves as people who inflict it.

Euthanasia

Further information: Euthanasia and Animal euthanasiaDeath is not considered by policy makers to be an issue that harms laboratory animals. Any controversy about the death of laboratory animals focuses on whether particular methods cause pain and suffering, not whether their death is, in and of itself, undesirable. Researchers call the killing of laboratory animals after an experiment "euthanasia" — literally "good death" — a term applied to all animals, including the young and healthy, whereas the same term is used of human beings only when the death will end severe suffering that cannot otherwise be relieved.

Ethics

Further information: Animal rightsThe ethics and point of performing experiments on animals are subject to much debate. There are disagreements about which animal testing procedures are useful for which purposes, as well as disagreements over which ethical principles apply. Some ethical positions consider that animals have an intrinsic right not to be experimented on, and that experiments should be conducted on humans who have given informed consent instead. Some opponents, particularly supporters of animal rights, argue further that any benefits to human beings cannot outweigh the suffering of the animals, and that human beings have no moral right to use an individual animal in ways that do not benefit that individual. The benefits of animal testing are also questioned, with organizations such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals stating that the suffering of the animals used in research is excessive in relation to whatever benefits may be reaped, and that in practice there is widespread abuse of animals..

Others take a utilitarian approach and try to weigh the positive and negative aspects of animal experiments; designing protocols and laws that attempt to maximize desirable results and minimize pain and suffering. In particular, proponents argue that it would be unethical to test substances or drugs with potentially adverse side-effects on human beings, and that animals receive more sophisticated medical care because of animal tests that have led to advances in veterinary medicine. The focus of public debate on this issue is also questioned, with over 10 times more animals are used by humans for other purposes (agriculture, hunting, pest control) than are used in animal testing. 100 million animals are killed by hunting each year. 150 million large mammals are used in agriculture each year. Hundreds of millions of rats are involved in pest control. Over seven million dogs and cats are euthanized by animal shelters each year, and a million animals are killed each day by automobiles.

Controversy

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Highlighted cases

- Huntingdon Life Sciences

In 1997, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) filmed staff inside Huntingdon Life Sciences (HLS) in the UK, Europe's largest animal-testing facility, hitting puppies, shouting at them, and simulating sex acts while taking blood samples. The employees were dismissed and prosecuted, and HLS's licence to perform animal experiments was revoked for six months. Footage shot inside HLS in the U.S. appeared to show technicians dissecting a live monkey. (video) The broadcast of the undercover footage on British television in 1997 triggered the formation of Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty, an international campaign to close HLS, which has been criticized for its sometimes violent tactics.

- Covance

In 2004, German journalist Friedrich Mülln shot undercover footage of staff in Covance, Münster, Europe's largest primate-testing center, making monkeys dance in time to blaring pop music, handling them roughly, and screaming at them. The monkeys were kept isolated in small wire cages with little or no natural light, no environmental enrichment, and high noise levels from staff shouting and playing the radio (video). Primatologist Dr. Jane Goodall described the living conditions of the monkeys as "horrendous." Primatologist Stephen Brend told BUAV that using monkeys in such a stressed state is "bad science," and trying to extrapolate useful data in such circumstances an "untenable proposition." Covance obtained a restraining order preventing Mülln from performing any further undercover research against the company for three years, and required him and PETA to turn over the material they obtained from Covance. PETA is further prevented from attempting to infiltrate Covance for five years.

- University of Cambridge

In February 2005, the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV) told the High Court in London that internal documents from the University of Cambridge's primate-testing labs showed that monkeys had undergone surgery to induce a stroke, and were left alone after the procedure for 15 hours overnight. Researchers had trained the monkeys to perform certain tasks before inflicting brain damage and re-testing them. The monkeys were deprived of food and water to encourage them to perform the tasks. The judge hearing BUAV's application for a judicial review rejected the allegation that the Home Secretary had been negligent in granting the university a license.

- University of California, Riverside

One of the best-known cases of alleged abuse involved Britches, a macaque monkey born in 1985 at the University of California, Riverside, removed from his mother at birth, and left alone with his eyelids sewn shut, and a sonar device on his head, as part of a sight-deprivation experiment. He was removed from the laboratory during a raid by the Animal Liberation Front (video). The university criticized the ALF, alleging that damage to the monkey's eyelids (see image), caused by the sutures according to the ALF, had in fact been caused by an ALF veterinarian, and that the sutures and sonar device had been tampered with by the activists.

- Columbia University

CNN reported in October 2003 that a post-doctoral "whistleblowing" veterinarian at Columbia University approached the university's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee about experiments being carried out by an assistant professor of neurosurgery, E. Sander Connolly. Connolly was allegedly causing strokes in baboons by removing their left eyeballs and using the eye sockets to reach a critical blood vessel to their brains. A clamp was placed on the blood vessel until the stroke was induced, after which Connolly would try to treat the condition with an experimental drug. In a letter to the National Institute of Health, PETA cited the case of one baboon left for two days unable to sit up or eat, who was slouched over in his cage and vomiting before dying. An investigation by the United States Department of Agriculture found the experiments did not violate federal guidelines. Connolly abandoned the research saying he felt under attack after receiving a threatening e-mail, but continued to believe his experiments were humane and potentially valuable.

Threats to researchers

- University of California, Los Angeles

In 2006, a primate researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) shut down the experiments in his lab after threats from animal rights activists. The researcher had received a grant to use 30 macaque monkeys for vision experiments; each monkey was paralyzed, then used for a single session that lasted up to 120 hours, and finally killed. The researcher's name, phone number, and address were posted on the website of the Primate Freedom Project. Demonstrations were held in front of his home. A Molotov cocktail was placed on the porch of what was believed to be the home of another UCLA primate researcher; instead, it was accidentally left on the porch of an elderly woman unrelated to the university. The Animal Liberation Front claimed responsibility for the attack. As a result of the campaign, the researcher sent an email to the Primate Freedom Project stating "you win," and "please don’t bother my family anymore." In another incident at UCLA in June 2007, the Animal Liberation Brigade placed a bomb under the car of a UCLA children's ophthalmologist who experiments on cats and rhesus monkeys; the bomb had a faulty fuse and did not detonate. UCLA is now refusing Freedom of Information Act requests for animal medical records.

Alternatives to animal testing

Main article: Alternatives to animal testingScientists and governments state that animal testing should cause as little suffering to animals as possible, and that animal tests should only be performed where necessary. The "three Rs" are guiding principles for the use of animals in research in most countries:

- Reduction refers to methods that enable researchers to obtain comparable levels of information from fewer animals, or to obtain more information from the same number of animals.

- Replacement refers to the preferred use of non-animal methods over animal methods whenever it is possible to achieve the same scientific aim.

- Refinement refers to methods that alleviate or minimize potential pain, suffering or distress, and enhance animal welfare for the animals still used.

Although such principles have been welcomed as a step forwards by some animal welfare groups, they have also been criticized as both outdated by current research, and of little practical effect in improving animal welfare.

See also

Notes

- FY 2004 AWA inspections, p. 10.

- ^ "Primates, Basic facts", British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection. Cite error: The named reference "buavprimates" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Jha, Alok. RSPCA outrage as experiments on animals rise to 2.85m", The Guardian, December 9, 2005.

- "Vivisection FAQ, British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection; "Numbers of animals", Research Defence Society; "The Ethics of research involving animals", Nuffield Council on Bioethics, section 1.6.

- "Introduction", Select Committee on Animals In Scientific Procedures Report, United Kingdom Parliament.

- "Use of Laboratory Animals in Biomedical and Behavioral Research", Institute for Laboratory Animal Research, The National Academies Press, 1988. Also see Cooper, Sylvia. "Pets crowd animal shelter", The Augusta Chronicle, August 1, 1999; and Gillham, Christina. "Bought to be sold", Newsweek, February 17, 2006.

- The use of non-human animals in research: a guide for scientists The Royal Society, 2004, page 1

- "Science, Medicine, and Animals", Institute for Laboratory Animal Research, Published by the National Research Council of the National Academies 2004; page 2 See also "Benefits of animal research", American Association for Laboratory Animal Science.

-

- "UK Legislation: A Criticism", and "FAQs: Vivisection", British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection;

- "Animal experimentation issues", Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine;

- Croce, Pietro. Vivisection or Science? An Investigation into Testing Drugs and Safeguarding Health. Zed Books, 1999.

- "Vivisection", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2007. Also see Croce, Pietro. Vivisection or Science? An Investigation into Testing Drugs and Safeguarding Health. Zed Books, 1999, and "FAQs: Vivisection", British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection.

- Carbone, Larry. What Animals Want: Expertise and Advocacy in Laboratory Animal Welfare. Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 22.

- Paixao, RL; Schramm, FR. Ethics and animal experimentation: what is debated? Cad. Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro, 2007

- Yarri, Donna. The Ethics of Animal Experimentation, Oxford University Press U.S., 2005

- ^ Croce, Pietro. Vivisection or Science? An Investigation into Testing Drugs and Safeguarding Health. Zed Books, 1999, p. 11.

- ^ Bernard, Claude An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine, 1865. First English translation by Henry Copley Greene, published by Macmillan & Co., Ltd., 1927; reprinted in 1949, p125

- "History of nonhuman animal research", Laboratory Primate Advocacy Group.

- Ryder, Richard D. Animal Revolution: Changing Attitudes Towards Speciesism. Berg Publishers, 2000, p. 54.

- ^ "Animal Experimentation: A Student Guide to Balancing the Issues", Australian and New Zealand Council for the Care of Animals in Research and Teaching (ANZCCART), retrieved December 12, 2007, cites original reference in Maehle, A-H. and Tr6hler, U. 1987. Animal experimentation from antiquity to the end of the eighteenth century: attitudes and arguments. In N. A. Rupke (ed.) Vivisection in Historical Perspective. Croom Helm, London, p. 22

- "In sickness and in health: vivisection's undoing", The Daily Telegraph, November 2003.

- LaFollette, H., Shanks, N., Animal Experimentation: the Legacy of Claude Bernard, International Studies in the Philosophy of Science (1994) pp. 195-210.

- Rudacille, Deborah. The Scalpel and the Butterfly: The Conflict, Farrar Straus Giroux, 2000, p. 19.

- The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, Volume II, fullbooks.com

- Bowlby, John. Charles Darwin: A New Life, W. W. Norton & Company - 1991. p. 420

- Mason, Peter. The Brown Dog Affair. Two Sevens Publishing, 1997.

- Gratzer, Walter. Eurekas and Euphorias: The Oxford Book of Scientific Anecdotes. Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 224.

- ^ Fifth Report on the Statistics on the Number of Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes in the Member States of the European Union Commission of the European Communities, published November 2007

- "Vivisection FAQ, British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection.

- ^ "The Ethics of research involving animals", Nuffield Council on Bioethics, section 1.6.

- Carbone, Larry. '"What Animal Want: Expertise and Advocacy in Laboratory Animal Welfare Policy. Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 26.

- FY 2005 AWA inspections

- "National Association of Biomedical Research

- Science Magazine, Trull and Rich 1999 Vol. 284. no. 5419, p. 1463.

- Rowan, Loew, and Weer 1995cited in Carbone 2004, p. 26.

- Alternatives to Animal Use in Research, Testing and Education, U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment, Washington, D.C.:Government Printing Office, 1986, p. 64. In 1966, the Laboratory Animal Breeders Association estimated in testimony before Congress that the number of mice, rats, guinea pigs, hamsters, and rabbits used in 1965 was around 60 million. (Hearings before the Subcommittee on Livestock and Feed Grains, Committee on Agriculture, U.S. House of Representatives, 1966, p. 63.) In 2004, the Department of Agriculture listed 64,932 dogs, 23,640 cats, 54,998 non-human primates, 244,104 guinea pigs, 175,721 hamsters, 261,573 rabbits, 105,678 farm animals, and 171,312 other mammals, a total of 1,101,958, a figure that includes all mammals except purpose-bred mice and rats. The use of dogs and cats in research in the U.S. decreased from 1973 to 2004 from 195,157 to 64,932, and from 66,165 to 23,640, respectively. ("Foundation for Biomedical Research, Quick Facts)

- ^ "Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals", Great Britain, 2004, p. 14.

- Jha, Alok. "RSPCA outrage as experiments on animals rise to 2.85m", The Guardian, December 9, 2005.

- ^ Schulenburg, H., Kurz, C.L., Ewbank, J.J. "Evolution of the innate immune system: the worm perspective," Immunol. Rev., volume 198, pp. 36-58, 2004. pmid 15199953

- Leclerc V, Reichhart JM. "The immune response of Drosophila melanogaster," Immunol. Rev.. volume 198, pp. 59-71, 2004. pmid 15199954

- Mylonakis E., Aballay A. "Worms and flies as genetically tractable animal models to study host-pathogen interactions", Infect. Immun., volume 73, issue 7, pp. 3833-41, 2005. pmid 15972468

- Quick Facts About Animal Research Foundation for Biomedical Research, Accessed 06 September 2007

- ^ Rosenthal N, Brown S. "The mouse ascending: perspectives for human-disease models," Nat. Cell Biol, Volume 9, issue 9, pp. 993-9, 2007. pmid 17762889

- The Measure Of Man, Sanger Institute Press Release, 5 December 2002

- Taconic Transgenic Models, Taconic Farms, Inc.

- ^ "Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals, Great Britain, 2004, British government.

- Cat madness: human research using cats AAVS newsletter Winter 2003

- Dog profile, The Humane Society of the United States.

- The USDA figures are cited in Dog profile, The Humane Society of the United States.

- Gillham, Christina. "Bought to be sold", Newsweek, February 17, 2006.

- "End Chimpanzee Research: Overview", Project R&R, New England Anti-Vivisection Society.

- International Perspectives: The Future of Nonhuman Primate Resources, Proceedings of the Workshop Held April 17-19, pages 36-45, 46-48, 63-69, 197-200.

- Primatology FAQ

- FY 2004 AWA inspections, p. 10.

- Demographic Analysis of Primate Research in the United States, Conlee, et al, Proceedings of the Fourth World Congress, accessed August 29, 2007.

- Science article on Chimps in the USA

- History of polio vaccine

- "The History of Deep Brain Simulation" (Overview of development of DBS in Parkinson's) at "The Parkinson's Appeal for Deep Brain Simulation", http://www.parkinsonsappeal.com.

- Demographic Analysis of Primate Research in the United States

- Invertebrate Animal Resources National Center for Research Resources, Accessed 15th December 2007

- "Who's Who of Federal Oversight of Animal Issues", Aesop Project.

- Collins FS, Rossant J, Wurst W. "A mouse for all reasons, Cell, volume 128, issue 1, 2007, pp. 9–13. pmid=17218247

-

- Class B dealers, Humane Society of the United States.

- Gillham, Christina. "Bought to be sold", Newsweek, February 17, 2006.

- "Who's Who of Federal Oversight of Animal Issues", Aesop Project;

- Salinger, Lawrence and Teddlie, Patricia. "Stealing Pets for Research and Profit: The Enforcement (?) of the Animal Welfare Act", paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Criminology, Royal York, Toronto, October 15, 2006;

- Class B dealers, Humane Society of the United States;

- Reitman, Judith. Stolen for Profit, Zebra 1995.

- Moran, Julio. "Three Sentenced to Prison for Stealing Pets for Research," L.A. Times, September 12, 1991.

- Francione, Gary. Animals, Property, and the Law. Temple University Press, 1995, p. 192; Magnuson, Warren G., Chairman. "Opening remarks in hearings prior to enactment of Pub. L. 89-544, the Laboratory Animal Welfare Act," U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, March 25, 1966.

- Notorious Animal Dealer Loses License and Pays Record Fine, The Humane Society of the United States.

- Animal Testing: Where Do the Animals Come From? American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. According to the ASPCA, the following states prohibit shelters from providing animals for research: Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Vermont, and West Virginia.

- Council Directive 86/609/EEC of 24 November 1986

- Brooman, Simon and Legge, Debbie. Law Relating to Animals, Taylor & Francis Group, 1999.

- ^ "Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals", Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals, Home Office, 2004, p. 87.

- Howard, Linda & Jones, Dena. "Trafficking in Misery: The Primate Trade", Animal Issues, Volume 31, Number 3, Fall 2000.

- Pippin, John. "Covance Gets an 'F' in Social-Responsibility Test", Chandler Republic, August 26, 2006; reproduced by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine.

- ^ Select Committee on Animals in Scientific Procedures Report, House of Lords, Chapter 3: The purpose and nature of animal experiments.

- "An A to Z of laboratory animals" Research Defense Society. Accessed 22nd August 2007; Job, C.K. "Nine-banded armadillo and leprosy research," Indian journal of pathology & microbiology, Volume 46, issue 4, 2003, pp. 541-50. PMID 15025339

- Venken KJ, Bellen HJ (2005) "Emerging technologies for gene manipulation in Drosophila melanogaster" Nat. Rev. Genet. volume 6 issue 3 pages 167–78 PMID 15738961

- Sung YH, Song J, Lee HW (2004) "Functional genomics approach using mice" J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. volume 37 issue 1 pages=122–32 PMID 14761310

- Janies D., DeSalle R. "Development, evolution, and corroboration," Anat. Rec., Volume 257, issue 1, pp. 6-14, 1999. PMID 10333399

- Akam, M. "Hox genes and the evolution of diverse body plans," Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B, Biol. Sci., Volume 349, issue 1329, 1995, pp. 313–9. PMID 8577843

- Prasad B., Reed R., "Chemosensation: molecular mechanisms in worms and mammals", Trends in Genetics Volume 15, pp. 150-153. 1999

- Schafer WR (2006) "Neurophysiological methods in C. elegans: an introduction" WormBook pages 1–4 PMID 18050439

- Yamamuro, Y. Social behavior in laboratory rats: Applications for psycho-neuroethology studies Animal Science Journal, 77, pp. 386–394, 2006

- Marler P., Slabbekoorn H, Nature's Music: The Science of Birdsong, Academic Press, 2004. ISBN 0124730701

- For example "in addition to providing the chimpanzees with enrichment, the termite mound is also the focal point of a tool-use study being conducted", from the web page of the Lincoln Park Zoo accessed 25 April 2007.

- Festing, M., "Inbred Strains of Mice and their Characteristics", The Jackson Laboratory , Retrieved 30 January, 2008

- Casci, T., "Evolution: Sticklebacks finally get a map", Nature Reviews Genetics 3, 84, 2002

- Ramaswamy S, McBride JL, Kordower JH (2007) "Animal models of Huntington's disease" ILAR J volume 48 issue 4 pages 356–73 PMID 17712222

- Rees DA, Alcolado JC (2005) "Animal models of diabetes mellitus" Diabet. Med. volume 22 issue 4 pages 359–70 PMID 15787657

- Iwakuma T, Lozano G (2007) "Crippling p53 activities via knock-in mutations in mouse models" Oncogene volume 26 issue 15 pages 2177–84 PMID 17401426

- Frese KK, Tuveson DA (2007) "Maximizing mouse cancer models" Nat. Rev. Cancer volume 7 issue 9 pages 645–58 PMID 17687385

- Dunham SP. "Lessons from the cat: development of vaccines against lentiviruses," Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol, volume 112, issues 1-2, 2006, pp. 67–77. pmid=16678276; Vail DM, MacEwen EG. "Spontaneously occurring tumors of companion animals as models for human cancer," Cancer Invest, volume 18, issue 8, 2000, pp. 781–92. pmid=11107448

- Job, C.K. "Nine-banded armadillo and leprosy research," Indian journal of pathology & microbiology, Volume 46, issue 4, pp. 541-50, 2003. pmid 15025339;

- Bryan, Jenny & Clare, John. Organ Farm, Carlton Books, 2001.

- ^ Townsend, Mark. "Exposed: secrets of the animal organ lab", The Observer, April 20, 2003.

- "Diaries of despair", xenodiaries.org, Uncaged Campaigns, retrieved June 18, 2006.

- ^ Household Product Tests BUAV

- ^ Abbott, Alison. "Animal testing: More than a cosmetic change" Nature 438, 144-146, November 10, 2005.

- Watkins JB (1989). "Exposure of rats to inhalational anesthetics alters the hepatobiliary clearance of cholephilic xenobiotics". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 250 (2): 421–7. PMID 2760837.

- Walum E Acute oral toxicity Environ. Health Perspect. volume 106 Suppl 2 pages=498–499 1998 pmid 9599698

- Inter-Governmental Organization Eliminates the LD50 Test, accessed 17 January 2008

- OECD guideline 405 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Accessed 19 January 2008

- Species Used in Research: Rabbit Humane Society of the United States, Accessed 19 January 2008

- Wilhelmus, K.R. "The Draize eye test," Surv Ophthalmol volume 45, issue 6, 2001, pages 493–515, PMID 11425356

- Secchi A., Deligianni V. "Ocular toxicology: the Draize eye test," Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol volume 6, issue 5, 2006, pp. 367–72. PMID 16954791

- Toxicity Testing for Assessment of Environmental Agents" National Academies Press, (2006), p21, Accessed 15th December

- Smith LL (2001). "Key challenges for toxicologists in the 21st century". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 22 (6): 281–5. PMID 11395155.

- Brown SL, Brett SM, Gough M, Rodricks JV, Tardiff RG, Turnbull D (1988). "Review of interspecies risk comparisons". Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 8 (2): 191–206. PMID 3051142.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - An overview of Animal Testing Issues, Humane Society of the United States.

- Osborn, Andrew & Gentleman, Amelia."Secret French move to block animal-testing ban", The Guardian, August 19, 2003.

- Taste of Raspberries, Taste of Death. The 1937 Elixir Sulfanilamide Incident, FDA Consumer magazine June 1981.

- EU Directive 2001/83/EC, p.44.

- EU Directive 2001/83/EC, p. 45.

- Dalal, Rooshin et al. Replacement Alternatives in Education: Animal-Free Teaching abstract from Fifth World Congress on Alternatives and Animal Use in the Life Sciences, Berlin, August 2005.

- Seeking an End to Animal Experimentation, Deutsche Welle, August 23, 2005, retrieved on December 16, 2007.

- Duncan IJ, Petherick JC. "The implications of cognitive processes for animal welfare", J. Anim. Sci., volume 69, issue 12, 1991, pp. 5017–22. pmid 1808195; Curtis SE, Stricklin WR. "The importance of animal cognition in agricultural animal production systems: an overview", J. Anim. Sci.. volume 69, issue 12, 1991, pp. 5001–7. pmid 1808193

- Stamp Dawkins, Marian. "Scientific Basis for Assessing Suffering in Animals," in Singer, Peter. In Defense of Animals: The Second Wave. Blackwell, 2006. p. 28.

- Animal Welfare; Definitions for and Reporting of Pain and Distress", Animal Welfare Information Center Bulletin, Summer 2000, Vol. 11 No. 1-2, United States Department of Agriculture.

- "USDA Animal Welfare Act Report 2004.

- Ryder, Richard D. "Speciesism in the laboratory," in Singer, Peter. In Defense of Animals: The Second Wave. Blackwell, 2006. p. 99.

- Carbone, Larry. '"What Animal Want: Expertise and Advocacy in Laboratory Animal Welfare Policy. Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 149.

- Malebranche, Nicholas. in Rodis-Lewis, G. (ed.). Oeuvres complètes. Paris: J. Vrin. 1958-70, II, p. 394, cited in Harrison, Peter. "Descartes on Animals," The Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 167, April 1992, pp. 219-227.

- Fontaine, Nicholas. 1738, p. 201, cited in Carbone, Larry. '"What Animal Want: Expertise and Advocacy in Laboratory Animal Welfare Policy. Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 149. Also see Carter, Alan. "Animals, Pain and Morality," Journal of Applied Philosophy, Volume 22, No. 1, March 2005, pp. 17–22.

- Rollin drafted the 1985 Health Research Extension Act and an animal welfare amendment to the 1985 Food Security Act: see Rollin, Bernard. "Animal research: a moral science. Talking Point on the use of animals in scientific research", EMBO reports 8, 6, 2007, pp. 521–525

- ^ Rollin, Bernard. The Unheeded Cry: Animal Consciousness, Animal Pain, and Science. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. xii, 117-118, cited in Carbone 2004, p. 150.

- Rollin, Bernard. "Animal research: a moral science. Talking Point on the use of animals in scientific research", EMBO reports 8, 6, 2007, pp. 521–525.

- "Interview with Bernard Rollin", DVM, a news magazine of veterinary medicine, October 5, 2007; also see Health Research Extension Act 1985, Public Law 99-158, November 20, 1985, "Animals in Research," retrieved January 30, 2008.

- Griffin DR, Speck GB (2004) "New evidence of animal consciousness" Anim. Cogn. volume 7 issue 1 pages=5–18 PMID 14658059

- Allen C (1998) Assessing animal cognition: ethological and philosophical perspectives J. Anim. Sci. volume 76 issue 1 pages 42-7 PMID 9464883

- Carbone 2004, p. 150.

- Carbone 2004, pp. 153-158.

- Carbone 2004, p. 151.

- Carbone, Larry. "Euthanasia," in Bekoff, M. and Meaney, C. Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Welfare. Greenwood Publishing Group, pp. 164-166, cited in Carbone 2004, p. 189.

- Letter from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals to Columbia University accessed 06 September 2007

- Covino, Joseph, Jr. Lab Animal Abuse: Vivisection Exposed!, Epic Press, 1990

- "It's a Dog's Life" (1997), Countryside Undercover, Channel Four Television, UK.

- Video link

- ^ Undercover footage of staff in Covance screaming at and mocking monkeys

- Covance Prevails in PETA lawsuit", Covance, October 17, 2005.

-

- Laville, Sandra. "Lab monkeys 'scream with fear' in tests", The Guardian, February 8, 2005.

- "Aspects of Non-human Primate Research at Cambridge University. A Review by the Chief Inspector", British Home Office, October 1, 2002.

- "The Queen on the application of THE CAMPAIGN TO END ALL ANIMAL EXPERIMENTS (trading as the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection), High Court, April 12, 2005.

- Newkirk, Ingrid. Free the Animals, Lantern Books, 2000, pp. 271-294.

- "Abstract: Trisenor rearing with infant macaques", Crisp.

- "The Story of Britches": Videotape of the Animal Liberation Front raid in which Britches was removed from the University of California, Riverside.

- Newkirk 2000

- "E. Sander Connolly", PETA.

- Columbia in animal cruelty dispute", CNN, October 12, 2003.

- McDonald, Patrick Range. UCLA Monkey Madness LA Weekly, August 8, 2007.

- Flecknell P (2002). "Replacement, reduction and refinement". ALTEX. 19 (2): 73–8. PMID 12098013.

- The 3Rs The National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research. Accessed 12 December 2007

- Kolar R (2002). "ECVAM: desperately needed or superfluous? An animal welfare perspective". Altern Lab Anim. 30 Suppl 2: 169–74. PMID 12513669.

- Schuppli CA, Fraser D, McDonald M (2004). "Expanding the three Rs to meet new challenges in humane animal experimentation". Altern Lab Anim. 32 (5): 525–32. PMID 15656775.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rusche B (2003). "The 3Rs and animal welfare - conflict or the way forward?". ALTEX. 20 (Suppl 1): 63–76. PMID 14671703.

Further reading and external links

- Stephens, Martin & Rowan, Andrew. Template:PDFlink, Humane Society of the United States, retrieved October 29, 2005

- 1940 American/Soviet film of dog resurrection experiments

- "Select Committee on Animals In Scientific Procedures Report", Select Committee on Animals in Scientific Procedures, British House of Lords, July 16, 2002, retrieved October 27, 2005.

- "Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals", Great Britain, 2004.

- "Why use animals?" and other FAQ, North Carolina Association for Biomedical Research, retrieved October 23, 2005

- "The benefits of animal research", Seriously Ill for Medical Research], retrieved October 23, 2005.

- "Basic statement", Aërzte gegen Tierversuche (Doctors against Animal Experiments], retrieved October 23, 2005.

- "Biomed for the layperson", Laboratory Primate Advocacy Group, retrieved February 24, 2006.

- "An introduction to primate issues", Humane Society of the United States.

- "Unhappy Anniversary: Twenty years of the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986", Animal Aid, retrieved July 15, 2006.

- In Focus "Animal Experiments in Research" (German Reference Centre for Ethics in the Life Sciences)

- Encyclopedia of Earth: Animal testing alternatives

- "Planet of Covance", a German film opposing animal testing

- "Tod im Labor" a film made by Animal Aid and Ärzte gegen Tierversuche (Doctors against Animal Experiments)

- Animal Welfare Gateway, a collection of international links related to laboratory animals

- Open Directory Project - Animal Experiments directory category

- Yahoo! - Animal Experimentation directory category.