| Revision as of 13:50, 15 July 2005 editGeogre (talk | contribs)25,257 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:51, 16 July 2005 edit undoBishonen (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators80,332 edits Changeable sceneryNext edit → | ||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

| ==New Welcome== | ==New Welcome== | ||

| Hey, Bishonen, there's this site called Misplaced Pages. I'm on it, like, all the time. You should check it out. It's kind of addictive, though, so don't edit articles, or you'll get hooked. It has this amazing ability to seem perfectible, even though it isn't, so you get suckered into continually thinking that you can make a difference, get rid of the bad, and supply the good. When you find out that the bad is like an ocean tide and that the good is like a towel under the door, you'll probably storm off. However, you end up coming back, thinking that you'll "just" do this or that, and that it'll be ok. Pretty soon, you find yourself trying to swap towels and run the drier. It's this cycle, until you realize that it's not perfectible, and you decide to just try to keep the old set of family photos dry or try to throw a life preserver to people you see out there who don't have boats. Anyway, so that's my welcome. ] 12:47, 15 July 2005 (UTC) | Hey, Bishonen, there's this site called Misplaced Pages. I'm on it, like, all the time. You should check it out. It's kind of addictive, though, so don't edit articles, or you'll get hooked. It has this amazing ability to seem perfectible, even though it isn't, so you get suckered into continually thinking that you can make a difference, get rid of the bad, and supply the good. When you find out that the bad is like an ocean tide and that the good is like a towel under the door, you'll probably storm off. However, you end up coming back, thinking that you'll "just" do this or that, and that it'll be ok. Pretty soon, you find yourself trying to swap towels and run the drier. It's this cycle, until you realize that it's not perfectible, and you decide to just try to keep the old set of family photos dry or try to throw a life preserver to people you see out there who don't have boats. Anyway, so that's my welcome. ] 12:47, 15 July 2005 (UTC) | ||

| ==Changeable scenery== | |||

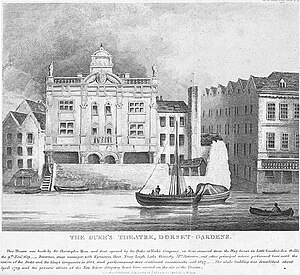

| During the British ] ]–], public stage performances were banned in England, a uniquely long and sharp break in dramatic tradition imposed by the ] regime. The ban was not 100% successful in keeping the hated stage make-believe down: acting in private houses was commonplace, and in London, pre-Commonwealth actors managed to scrape a living and evade the authorities in stealth acting companies such as that of ] at the Red Bull playhouse. The greatest loss of continuity was in the writing of plays, and in the lack of arenas for schooling new young playwrights. The dramatic writers of the previous era were biding their time, and by the late 1650s, it was becoming obvious that that time was coming. Secure in his assurance that new masters were coming in, William Davenant, who had been a prolific playwright and masque designer under ], put on several elaborate productions of new work of his own at ], including the opera ''The Siege of Rhodes''. When the performance ban was formally lifted at the ] of the monarchy in ], a new dramatic tradition was already underway, and Davenant hit the ground running. The stage-struck ] immediately encouraged the drama and took a personal interest in the scramble for acting licenses and performance rights which followed. Two middle-aged playwrights active under Charles I, Davenant and Killigrew, emerged victorious from the struggle, each with royal ] for a new (or refurbished) theatre company, the King's Company and the Duke's Company. | |||

Revision as of 11:51, 16 July 2005

New Welcome

Hey, Bishonen, there's this site called Misplaced Pages. I'm on it, like, all the time. You should check it out. It's kind of addictive, though, so don't edit articles, or you'll get hooked. It has this amazing ability to seem perfectible, even though it isn't, so you get suckered into continually thinking that you can make a difference, get rid of the bad, and supply the good. When you find out that the bad is like an ocean tide and that the good is like a towel under the door, you'll probably storm off. However, you end up coming back, thinking that you'll "just" do this or that, and that it'll be ok. Pretty soon, you find yourself trying to swap towels and run the drier. It's this cycle, until you realize that it's not perfectible, and you decide to just try to keep the old set of family photos dry or try to throw a life preserver to people you see out there who don't have boats. Anyway, so that's my welcome. Geogre 12:47, 15 July 2005 (UTC)

Changeable scenery

During the British Commonwealth 1642–1660, public stage performances were banned in England, a uniquely long and sharp break in dramatic tradition imposed by the Puritan regime. The ban was not 100% successful in keeping the hated stage make-believe down: acting in private houses was commonplace, and in London, pre-Commonwealth actors managed to scrape a living and evade the authorities in stealth acting companies such as that of Michael Mohun at the Red Bull playhouse. The greatest loss of continuity was in the writing of plays, and in the lack of arenas for schooling new young playwrights. The dramatic writers of the previous era were biding their time, and by the late 1650s, it was becoming obvious that that time was coming. Secure in his assurance that new masters were coming in, William Davenant, who had been a prolific playwright and masque designer under Charles I, put on several elaborate productions of new work of his own at Rutland House, including the opera The Siege of Rhodes. When the performance ban was formally lifted at the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, a new dramatic tradition was already underway, and Davenant hit the ground running. The stage-struck Charles II immediately encouraged the drama and took a personal interest in the scramble for acting licenses and performance rights which followed. Two middle-aged playwrights active under Charles I, Davenant and Killigrew, emerged victorious from the struggle, each with royal Letters Patent for a new (or refurbished) theatre company, the King's Company and the Duke's Company.