| Revision as of 14:15, 30 July 2008 edit222.127.91.65 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:03, 31 July 2008 edit undoSlashme (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers27,179 editsm Reverted 1 edit by 222.127.91.65 identified as vandalism to last revision by 24.165.5.160. (TW)Next edit → | ||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| {{Continuum mechanics}} | {{Continuum mechanics}} | ||

| '''Viscosity''' is a measure of the ] of a ] which is being deformed by either ] or ]. In general terms it is the resistance of a liquid to flow, or its "thickness". Viscosity describes a fluid's internal resistance to flow and may be thought of as a measure of fluid ]. Thus, ] is "thin", having a lower viscosity, while ] is "thick" having a higher viscosity. All real fluids (except ]s) have some resistance to ], but a fluid which has no resistance to shear stress is known as an '''ideal fluid''' or '''inviscid fluid'''. For example, a high viscosity magma will create a tall volcano, because it cannot spread fast enough; low viscosity lava will create a shield volcano, which is large and wide.<ref>{{cite book | '''Viscosity''' is a measure of the ] of a ] which is being deformed by either ] or ]. In general terms it is the resistance of a liquid to flow, or its "thickness". Viscosity describes a fluid's internal resistance to flow and may be thought of as a measure of fluid ]. Thus, ] is "thin", having a lower viscosity, while ] is "thick" having a higher viscosity. All real fluids (except ]s) have some resistance to ], but a fluid which has no resistance to shear stress is known as an '''ideal fluid''' or '''inviscid fluid'''. For example, a high viscosity magma will create a tall volcano, because it cannot spread fast enough; low viscosity lava will create a shield volcano, which is large and wide.<ref>{{cite book | ||

| | author = |

| author = Symon, Keith | ||

| | title = Mechanics | | title = Mechanics | ||

| | edition= Third Edition | | edition= Third Edition | ||

Revision as of 06:03, 31 July 2008

For other uses, see Viscosity (disambiguation).| Part of a series on | |||||||

| Continuum mechanics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fick's laws of diffusion | |||||||

Laws

|

|||||||

| Solid mechanics | |||||||

Fluid mechanics

|

|||||||

Rheology

|

|||||||

| Scientists | |||||||

Viscosity is a measure of the resistance of a fluid which is being deformed by either shear stress or extensional stress. In general terms it is the resistance of a liquid to flow, or its "thickness". Viscosity describes a fluid's internal resistance to flow and may be thought of as a measure of fluid friction. Thus, water is "thin", having a lower viscosity, while vegetable oil is "thick" having a higher viscosity. All real fluids (except superfluids) have some resistance to stress, but a fluid which has no resistance to shear stress is known as an ideal fluid or inviscid fluid. For example, a high viscosity magma will create a tall volcano, because it cannot spread fast enough; low viscosity lava will create a shield volcano, which is large and wide. The study of viscosity is known as rheology.

Etymology

The word "viscosity" derives from the Latin word "viscum" for mistletoe. A viscous glue was made from mistletoe berries and used for lime-twigs to catch birds.

Viscosity coefficients

When looking at a value for viscosity, the number that one most often sees is the coefficient of viscosity. There are several different viscosity coefficients depending on the nature of applied stress and nature of the fluid. They are introduced in the main books on hydrodynamics and rheology.

- Dynamic viscosity determines the dynamics of an incompressible Newtonian fluid;

- Kinematic viscosity is the dynamic viscosity divided by the density for a Newtonian fluid;

- Volume viscosity (or bulk viscosity) determines the dynamics of a compressible Newtonian fluid;

- Shear viscosity is the viscosity coefficient when the applied stress is a shear stress (valid for non-Newtonian fluids);

- Extensional viscosity is the viscosity coefficient when the applied stress is an extensional stress (valid for non-Newtonian fluids).

Shear viscosity and dynamic viscosity are much better known than the others. That is why they are often referred to as simply viscosity. Simply put, this quantity is the ratio between the pressure exerted on the surface of a fluid, in the lateral or horizontal direction, to the change in velocity of the fluid as you move down in the fluid (this is what is referred to as a velocity gradient). For example, at room temperature, water has a nominal viscosity of 1.0 × 10 Pa∙s and motor oil has a nominal apparent viscosity of 250 × 10 Pa∙s.

- Extensional viscosity is widely used for characterizing polymers.

- Volume viscosity is essential for Acoustics in fluids, see Stokes' law (sound attenuation)

Newton's theory

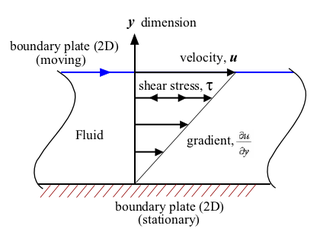

In general, in any flow, layers move at different velocities and the fluid's viscosity arises from the shear stress between the layers that ultimately opposes any applied force.

Isaac Newton postulated that, for straight, parallel and uniform flow, the shear stress, τ, between layers is proportional to the velocity gradient, ∂u/∂y, in the direction perpendicular to the layers.

- .

Here, the constant η is known as the coefficient of viscosity, the viscosity, the dynamic viscosity, or the Newtonian viscosity. Many fluids, such as water and most gases, satisfy Newton's criterion and are known as Newtonian fluids. Non-Newtonian fluids exhibit a more complicated relationship between shear stress and velocity gradient than simple linearity.

The relationship between the shear stress and the velocity gradient can also be obtained by considering two plates closely spaced apart at a distance y, and separated by a homogeneous substance. Assuming that the plates are very large, with a large area A, such that edge effects may be ignored, and that the lower plate is fixed, let a force F be applied to the upper plate. If this force causes the substance between the plates to undergo shear flow (as opposed to just shearing elastically until the shear stress in the substance balances the applied force), the substance is called a fluid. The applied force is proportional to the area and velocity of the plate and inversely proportional to the distance between the plates. Combining these three relations results in the equation F = η(Au/y), where η is the proportionality factor called the absolute viscosity (with units Pa·s = kg/(m·s) or slugs/(ft·s)). The absolute viscosity is also known as the dynamic viscosity, and is often shortened to simply viscosity. The equation can be expressed in terms of shear stress; τ = F/A = η(u/y). The rate of shear deformation is and can be also written as a shear velocity, du/dy. Hence, through this method, the relation between the shear stress and the velocity gradient can be obtained.

James Clerk Maxwell called viscosity fugitive elasticity because of the analogy that elastic deformation opposes shear stress in solids, while in viscous fluids, shear stress is opposed by rate of deformation.

Viscosity measurement

Dynamic viscosity is measured with various types of rheometer. Close temperature control of the fluid is essential to accurate measurements, particularly in materials like lubricants, whose viscosity can double with a change of only 5 °C. For some fluids, it is a constant over a wide range of shear rates. These are Newtonian fluids.

The fluids without a constant viscosity are called Non-Newtonian fluids. Their viscosity cannot be described by a single number. Non-Newtonian fluids exhibit a variety of different correlations between shear stress and shear rate.

One of the most common instruments for measuring kinematic viscosity is the glass capillary viscometer.

In paint industries, viscosity is commonly measured with a Zahn cup, in which the efflux time is determined and given to customers. The efflux time can also be converted to kinematic viscosities (cSt) through the conversion equations.

Also used in paint, a Stormer viscometer uses load-based rotation in order to determine viscosity. The viscosity is reported in Krebs units (KU), which are unique to Stormer viscometers.

Vibrating viscometers can also be used to measure viscosity. These models such as the Dynatrol use vibration rather than rotation to measure viscosity.

Extensional viscosity can be measured with various rheometers that apply extensional stress

Volume viscosity can be measured with acoustic rheometer.

Units of measure

Viscosity (dynamic/absolute viscosity)

Dynamic viscosity and absolute viscosity are synonymous. The IUPAC symbol for dynamic viscosity is the Greek letter eta () , but it is also commonly referred to using the Greek symbol mu (). The SI physical unit of dynamic viscosity is the pascal-second (Pa·s), which is identical to kg·m·s. If a fluid with a viscosity of one Pa·s is placed between two plates, and one plate is pushed sideways with a shear stress of one pascal, it moves a distance equal to the thickness of the layer between the plates in one second.

The name poiseuille (Pl) was proposed for this unit (after Jean Louis Marie Poiseuille who formulated Poiseuille's law of viscous flow), but not accepted internationally. Care must be taken in not confusing the poiseuille with the poise named after the same person.

The cgs physical unit for dynamic viscosity is the poise (P), named after Jean Louis Marie Poiseuille. It is more commonly expressed, particularly in ASTM standards, as centipoise (cP). Water at 20 °C has a viscosity of 1.0020 cP.

- 1 P = 1 g·cm·s

The relation between poise and pascal-seconds is:

- 10 P = 1 kg·m·s = 1 Pa·s

- 1 cP = 0.001 Pa·s = 1 mPa·s

Kinematic viscosity

In many situations, we are concerned with the ratio of the viscous force to the inertial force, the latter characterised by the fluid density ρ. This ratio is characterised by the kinematic viscosity (), defined as follows:

- ,

or

- .

where is the (dynamic or absolute) viscosity (in centipoise cP), and is the density (in grams/cm^3), and is the kinematic viscosity (in centistokes cSt ).

Kinematic viscosity (Greek symbol: ) has SI units Pa.s/(kg/m) = m·s. The cgs physical unit for kinematic viscosity is the stokes (St), named after George Gabriel Stokes. It is sometimes expressed in terms of centistokes (cSt or ctsk). In U.S. usage, stoke is sometimes used as the singular form.

- 1 stokes = 100 centistokes = 1 cm·s = 0.0001 m·s.

- 1 centistokes = 1 mm·s = 10m·s

Saybolt Universal Viscosity

At one time the petroleum industry relied on measuring kinematic viscosity by means of the Saybolt viscometer, and expressing kinematic viscosity in units of Saybolt Universal Seconds (SUS). Kinematic viscosity in centistoke can be converted from SUS according to the arithmetic and the reference tabel provided in ASTM D 2161. It can also be converted in computerized method, or vice versa.

Relation to Mean Free Path of Diffusing Particles

In relation to diffusion, the kinematic viscosity provides a better understanding of the behavior of mass transport of a dilute species. Viscosity is related to shear stress and the rate of shear in a fluid, which illustrates its dependence on the mean free path, , of the diffusing particles.

From fluid mechanics, shear stress, , is the rate of change of velocity with distance perpendicular to the direction of movement.

- .

Interpreting shear stress as the time rate of change of momentum,p, per unit area (rate of momentum flux) of an arbitrary control surface gives

- .

Further manipulation will show

where

- is the rate of change of mass

- is the density of the fluid

- is the average molecular speed

- is the dynamic viscosity.

Dynamic versus kinematic viscosity

Conversion between kinematic and dynamic viscosity is given by .

For example,

- if 0.0001 m·s and 1000 kg m then 0.1 kg·m·s = 0.1 Pa·s

- if 1 St (= 1 cm·s) and 1 g cm then 1 g·cm·s = 1 P

A plot of the kinematic viscosity of air as a function of absolute temperature is available on the Internet.

Example: viscosity of water

Because of its density of = 1 g/cm (varies slightly with temperature), and its dynamic viscosity is near 1 mPa·s (see #Viscosity of water section), the viscosity values of water are, to rough precision, all powers of ten:

Dynamic viscosity:

- = 1 mPa·s = 10 Pa·s = 1 cP = 10 poise

Kinematic viscosity:

- = 1 cSt = 10 stokes = 1 mm²/s

Molecular origins

The viscosity of a system is determined by how molecules constituting the system interact. There are no simple but correct expressions for the viscosity of a fluid. The simplest exact expressions are the Green-Kubo relations for the linear shear viscosity or the Transient Time Correlation Function expressions derived by Evans and Morriss in 1985. Although these expressions are each exact in order to calculate the viscosity of a dense fluid, using these relations requires the use of molecular dynamics computer simulations.

Gases

Viscosity in gases arises principally from the molecular diffusion that transports momentum between layers of flow. The kinetic theory of gases allows accurate prediction of the behavior of gaseous viscosity.

Within the regime where the theory is applicable:

- Viscosity is independent of pressure and

- Viscosity increases as temperature increases.

James Clerk Maxwell published a famous paper in 1866 using the kinetic theory of gases to study gaseous viscosity.

Effect of temperature on the viscosity of a gas

Sutherland's formula can be used to derive the dynamic viscosity of an ideal gas as a function of the temperature:

where:

- = viscosity in (Pa·s) at input temperature

- = reference viscosity in (Pa·s) at reference temperature

- = input temperature in kelvin

- = reference temperature in kelvin

- = Sutherland's constant for the gaseous material in question

Valid for temperatures between 0 < < 555 K with an error due to pressure less than 10% below 3.45 MPa

Sutherland's constant and reference temperature for some gases

| Gas |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| air | 120 | 291.15 | 18.27 |

| nitrogen | 111 | 300.55 | 17.81 |

| oxygen | 127 | 292.25 | 20.18 |

| carbon dioxide | 240 | 293.15 | 14.8 |

| carbon monoxide | 118 | 288.15 | 17.2 |

| hydrogen | 72 | 293.85 | 8.76 |

| ammonia | 370 | 293.15 | 9.82 |

| sulfur dioxide | 416 | 293.65 | 12.54 |

| helium | 79.4 | 273 | 19 |

(also see: )

Viscosity of a dilute gas

The Chapman-Enskog equation may be used to estimate viscosity for a dilute gas. This equation is based on semi-theorethical assumption by Chapman and Enskoq. The equation requires three empirically determined parameters: the collision diameter (σ), the maximum energy of attraction divided by the Boltzmann constant (є/к) and the collision integral (ω(T*)).

- T*=κT/ε Reduced temperature (dimensionless)

- = viscosity for dilute gas (uP)

- = molecular mass (g/mol)

- = temperature (K)

- = the collision diameter (Å)

- = the maximum energy of attraction divided by the Boltzmann constant (K)

- = the collision integral

Liquids

In liquids, the additional forces between molecules become important. This leads to an additional contribution to the shear stress though the exact mechanics of this are still controversial. Thus, in liquids:

- Viscosity is independent of pressure (except at very high pressure); and

- Viscosity tends to fall as temperature increases (for example, water viscosity goes from 1.79 cP to 0.28 cP in the temperature range from 0 °C to 100 °C); see temperature dependence of liquid viscosity for more details.

The dynamic viscosities of liquids are typically several orders of magnitude higher than dynamic viscosities of gases.

Viscosity of blends of liquids

The viscosity of the blend of two or more liquids can be estimated using the Refutas equation. The calculation is carried out in three steps.

The first step is to calculate the Viscosity Blending Number (VBN) (also called the Viscosity Blending Index) of each component of the blend:

- (1)

where v is the kinematic viscosity in centistokes (cSt). It is important that the kinematic viscosity of each component of the blend be obtained at the same temperature.

The next step is to calculate the VBN of the blend, using this equation:

- (2)

where is the mass fraction of each component of the blend.

Once the viscosity blending number of a blend has been calculated using equation (2), the final step is to determine the kinematic viscosity of the blend by solving equation (1) for v:

- (3)

where is the viscosity blending number of the blend.

Viscosity of selected substances

The viscosity of air and water are by far the two most important materials for aviation aerodynamics and shipping fluid dynamics. Temperature plays the main role in determining viscosity.

Viscosity of air

The viscosity of air depends mostly on the temperature. At 15.0 °C, the viscosity of air is 1.78 × 10 kg/(m·s) or 1.78 × 10 P. One can get the viscosity of air as a function of temperature from the Gas Viscosity Calculator

Viscosity of water

The viscosity of water is 8.90 × 10 Pa·s or 8.90 × 10 dyn·s/cm or 0.890 cP at about 25 °C.

As a function of temperature T (K):

μ(Pa·s) = A × 10

where A=2.414 × 10 Pa·s ; B = 247.8 K ; and C = 140 K.

Viscosity of water at different temperatures is listed below.

| Temperature

|

viscosity

|

|---|---|

| 10 | 1.308 × 10 |

| 20 | 1.003 × 10 |

| 30 | 7.978 × 10 |

| 40 | 6.531 × 10 |

| 50 | 5.471 × 10 |

| 60 | 4.668 × 10 |

| 70 | 4.044 × 10 |

| 80 | 3.550 × 10 |

| 90 | 3.150 × 10 |

| 100 | 2.822 × 10 |

Viscosity of various materials

Some dynamic viscosities of Newtonian fluids are listed below:

| viscosity

| |

|---|---|

| hydrogen | 8.4 × 10 |

| air | 17.4 × 10 |

| xenon | 2.12 × 10 |

| viscosity

|

viscosity

| |

|---|---|---|

| liquid nitrogen @ 77K | 1.58 × 10 | 0.158 |

| acetone* | 3.06 × 10 | 0.306 |

| methanol* | 5.44 × 10 | 0.544 |

| benzene* | 6.04 × 10 | 0.604 |

| water | 8.94 × 10 | 0.894 |

| ethanol* | 1.074 × 10 | 1.074 |

| mercury* | 1.526 × 10 | 1.526 |

| nitrobenzene* | 1.863 × 10 | 1.863 |

| propanol* | 1.945 × 10 | 1.945 |

| Ethylene glycol | 1.61 × 10 | 16.1 |

| sulfuric acid* | 2.42 × 10 | 24.2 |

| olive oil | .081 | 81 |

| glycerol* | .934 | 934 |

| castor oil* | .985 | 985 |

| corn syrup* | 1.3806 | 1380.6 |

| HFO-380 | 2.022 | 2022 |

| pitch | 2.3 × 10 | 2.3 × 10 |

* Data from CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 73 edition, 1992-1993.

Fluids with variable compositions, such as honey, can have a wide range of viscosities.

A more complete table can be found at Transwiki, including the following:

| viscosity

| |

|---|---|

| honey | 2,000–10,000 |

| molasses | 5,000–10,000 |

| molten glass | 10,000–1,000,000 |

| chocolate syrup | 10,000–25,000 |

| molten chocolate | 45,000–130,000 |

| ketchup | 50,000–100,000 |

| peanut butter | ~250,000 |

| shortening | ~250,000 |

* These materials are highly non-Newtonian.

Viscosity of solids

On the basis that all solids, such as granite flow to a small extent in response to shear stress some researchers have contended that substances known as amorphous solids, such as glass and many polymers, may be considered to have viscosity. This has led some to the view that solids are simply liquids with a very high viscosity, typically greater than 10 Pa·s. This position is often adopted by supporters of the widely held misconception that glass flow can be observed in old buildings. This distortion is more likely the result of the glass making process rather than the viscosity of glass.

However, others argue that solids are, in general, elastic for small stresses while fluids are not. Even if solids flow at higher stresses, they are characterized by their low-stress behavior. Viscosity may be an appropriate characteristic for solids in a plastic regime. The situation becomes somewhat confused as the term viscosity is sometimes used for solid materials, for example Maxwell materials, to describe the relationship between stress and the rate of change of strain, rather than rate of shear.

These distinctions may be largely resolved by considering the constitutive equations of the material in question, which take into account both its viscous and elastic behaviors. Materials for which both their viscosity and their elasticity are important in a particular range of deformation and deformation rate are called viscoelastic. In geology, earth materials that exhibit viscous deformation at least three times greater than their elastic deformation are sometimes called rheids.

Viscosity of amorphous materials

Viscous flow in amorphous materials (e.g. in glasses and melts) is a thermally activated process:

where is activation energy, is temperature, is the molar gas constant and is approximately a constant.

The viscous flow in amorphous materials is characterized by a deviation from the Arrhenius-type behavior: changes from a high value at low temperatures (in the glassy state) to a low value at high temperatures (in the liquid state). Depending on this change, amorphous materials are classified as either

- strong when: or

- fragile when:

The fragility of amorphous materials is numerically characterized by the Doremus’ fragility ratio:

and strong material have whereas fragile materials have

The viscosity of amorphous materials is quite exactly described by a two-exponential equation:

with constants and related to thermodynamic parameters of joining bonds of an amorphous material.

Not very far from the glass transition temperature, , this equation can be approximated by a Vogel-Tammann-Fulcher (VTF) equation or a Kohlrausch-type stretched-exponential law.

If the temperature is significantly lower than the glass transition temperature, , then the two-exponential equation simplifies to an Arrhenius type equation:

with:

where is the enthalpy of formation of broken bonds (termed configurons) and is the enthalpy of their motion. When the temperature is less than the glass transition temperature, , the activation energy of viscosity is high because the amorphous materials are in the glassy state and most of their joining bonds are intact.

If the temperature is highly above the glass transition temperature, , the two-exponential equation also simplifies to an Arrhenius type equation:

with:

When the temperature is higher than the glass transition temperature, , the activation energy of viscosity is low because amorphous materials are melt and have most of their joining bonds broken which facilitates flow.

Volume (bulk) viscosity

The negative-one-third of the trace of the stress tensor is often identified with the thermodynamic pressure,

,

which only depends upon the equilibrium state potentials like temperature and density (equation of state). In general, the trace of the stress tensor is the sum of thermodynamic pressure contribution plus another contribution which is proportional to the divergence of the velocity field. This constant of proportionality is called the volume viscosity.

Eddy viscosity

In the study of turbulence in fluids, a common practical strategy for calculation is to ignore the small-scale vortices (or eddies) in the motion and to calculate a large-scale motion with an eddy viscosity that characterizes the transport and dissipation of energy in the smaller-scale flow (see large eddy simulation). Values of eddy viscosity used in modeling ocean circulation may be from 5x10 to 10 Pa·s depending upon the resolution of the numerical grid.

Fluidity

The reciprocal of viscosity is fluidity, usually symbolized by or , depending on the convention used, measured in reciprocal poise (cm·s·g), sometimes called the rhe. Fluidity is seldom used in engineering practice.

The concept of fluidity can be used to determine the viscosity of an ideal solution. For two components and , the fluidity when and are mixed is

which is only slightly simpler than the equivalent equation in terms of viscosity:

where and is the mole fraction of component and respectively, and and are the components pure viscosities.

The linear viscous stress tensor

(See Hooke's law and strain tensor for an analogous development for linearly elastic materials.)

Viscous forces in a fluid are a function of the rate at which the fluid velocity is changing over distance. The velocity at any point is specified by the velocity field . The velocity at a small distance from point may be written as a Taylor series:

where is shorthand for the dyadic product of the del operator and the velocity:

This is just the Jacobian of the velocity field. Viscous forces are the result of relative motion between elements of the fluid, and so are expressible as a function of the velocity field. In other words, the forces at are a function of and all derivatives of at that point. In the case of linear viscosity, the viscous force will be a function of the Jacobian tensor alone. For almost all practical situations, the linear approximation is sufficient.

If we represent x, y, and z by indices 1, 2, and 3 respectively, the i,j component of the Jacobian may be written as where is shorthand for . Note that when the first and higher derivative terms are zero, the velocity of all fluid elements is parallel, and there are no viscous forces.

Any matrix may be written as the sum of an antisymmetric matrix and a symmetric matrix, and this decomposition is independent of coordinate system, and so has physical significance. The velocity field may be approximated as:

where Einstein notation is now being used in which repeated indices in a product are implicitly summed. The second term from the right is the asymmetric part of the first derivative term, and it represents a rigid rotation of the fluid about with angular velocity where:

For such a rigid rotation, there is no change in the relative positions of the fluid elements, and so there is no viscous force associated with this term. The remaining symmetric term is responsible for the viscous forces in the fluid. Assuming the fluid is isotropic (i.e. its properties are the same in all directions), then the most general way that the symmetric term (the rate-of-strain tensor) can be broken down in a coordinate-independent (and therefore physically real) way is as the sum of a constant tensor (the rate-of-expansion tensor) and a traceless symmetric tensor (the rate-of-shear tensor):

where is the unit tensor. The most general linear relationship between the stress tensor and the rate-of-strain tensor is then a linear combination of these two tensors:

where is the coefficient of bulk viscosity (or "second viscosity") and is the coefficient of (shear) viscosity.

The forces in the fluid are due to the velocities of the individual molecules. The velocity of a molecule may be thought of as the sum of the fluid velocity and the thermal velocity. The viscous stress tensor described above gives the force due to the fluid velocity only. The force on an area element in the fluid due to the thermal velocities of the molecules is just the hydrostatic pressure. This pressure term () must be added to the viscous stress tensor to obtain the total stress tensor for the fluid.

The infinitesimal force on an infinitesimal area is then given by the usual relationship:

See also

- Deborah number

- Dilatant

- Hyperviscosity syndrome

- Inviscid flow

- Reynold's number

- Rheology

- Thixotropy

- Viscometer

- Viscometry

- Viscoelasticity

- Viscosity index

- Joback method (Estimation of the liquid viscosity from molecular structure)

References

- Symon, Keith (1971). Mechanics (Third Edition ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-07392-7.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - The Online Etymology Dictionary

- Happel, J. and Brenner , H. "Low Reynolds number hydrodynamics", Prentice-Hall, (1965)

- Landau, L.D. and Lifshitz, E.M. "Fluid mechanics", Pergamon Press,(1959)

- Barnes, H.A. "A Handbook of Elementary Rheology", Institute of Non-Newtonian Fluid mechanics, UK (2000)

- Raymond A. Serway (1996). Physics for Scientists & Engineers (4th Edition ed.). Saunders College Publishing. ISBN 0-03-005932-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Dukhin, A.S. and Goetz, P.J. "Ultrasound for characterizing colloids", Elsevier, (2002)

- IUPAC Gold Book, Definition of (dynamic) viscocity

- IUPAC definition of the Poise

- ASTM D 2161, Page one,(2005)

- Quantities and Units of Viscosity

- James Ierardi's Fire Protection Engineering Site

- Maxwell, J. C. (1866), "On the viscosity or internal friction of air and other gases", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 156: 249–268, doi:10.1098/rstl.1866.0013

- data constants for sutherland's formula

- Viscosity of liquids and gases

- http://www.epa.gov/EPA-AIR/2005/July/Day-13/a11534d.htm

- J.O. Hirshfelder, C.F. Curtis and R.B. Bird (1964). Molecular theory of gases and liquids (First Edition ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-40065-3.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Robert E. Maples (2000). Petroleum Refinery Process Economics (2nd Edition ed.). Pennwell Books. ISBN 0-87814-779-9.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - C.T. Baird (1989), Guide to Petroleum Product Blending, HPI Consultants, Inc. HPI website

- "Chocolate Processing". Brookfield Engineering website. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- Kumagai, Naoichi (15 February 1978). "Long-term Creep of Rocks: Results with Large Specimens Obtained in about 20 Years and Those with Small Specimens in about 3 Years". Journal of the Society of Materials Science (Japan). 27 (293). Japan Energy Society: 157–161. Retrieved 06-16-2008.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Elert, Glenn. "Viscosity". The Physics Hypertextbook.

- "Antique windowpanes and the flow of supercooled liquids", by Robert C. Plumb, (Worcester Polytech. Inst., Worcester, MA, 01609, USA), J. Chem. Educ. (1989), 66 (12), 994-6

- Gibbs, Philip. "Is Glass a Liquid or a Solid?". Retrieved 2007-07-31.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Viscosity calculation of glasses

- R.H.Doremus (2002). "Viscosity of silica". J. Appl. Phys. 92 (12): 7619–7629. doi:10.1063/1.1515132. ISSN 0021-8979.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - M.I. Ojovan and W.E. Lee (2004). "Viscosity of network liquids within Doremus approach". J. Appl. Phys. 95 (7): 3803–3810. doi:10.1063/1.1647260. ISSN 0021-8979.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "month" ignored (help) - M.I. Ojovan, K.P. Travis and R.J. Hand (2000). "Thermodynamic parameters of bonds in glassy materials from viscosity-temperature relationships". J. Phys.: Condensed matter. 19 (41): 415107. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/19/41/415107. ISSN 0953-8984.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|moth=(help) - L.D. Landau and E.M. Lifshitz (translated from Russian by J.B. Sykes and W.H. Reid) (1997). Fluid Mechanics (2nd Edition ed.). Butterworth Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-2767-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)

Additional reading

- Massey, B. S. (1983). Mechanics of Fluids (Fifth Edition ed.). Van Nostrand Reinhold (UK). ISBN 0-442-30552-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)

External links

- Gas Dynamics Toolbox Calculate coefficient of viscosity for mixtures of gases

- Physical Characteristics of Water A table of water viscosity as a function of temperature

- Glass Viscosity Measurement Viscosity measurement, viscosity units and fixpoints, glass viscosity calculation

- diracdelta.co.uk conversion between kinematic and dynamic viscosity.

- Vogel-Tammann-Fulcher Equation Parameters

- Dispersion Technology

| Major branches of physics | |

|---|---|

| Divisions | |

| Approaches | |

| Classical | |

| Modern | |

| Interdisciplinary | |

| Related | |

.

. and can be also written as a shear velocity, du/dy. Hence, through this method, the relation between the shear stress and the velocity gradient can be obtained.

and can be also written as a shear velocity, du/dy. Hence, through this method, the relation between the shear stress and the velocity gradient can be obtained.

) , but it is also commonly referred to using the Greek symbol mu (

) , but it is also commonly referred to using the Greek symbol mu ( ). The

). The  ), defined as follows:

), defined as follows:

,

, .

. is the (dynamic or absolute) viscosity (in centipoise cP),

and

is the (dynamic or absolute) viscosity (in centipoise cP),

and  is the density (in grams/cm^3),

and

is the density (in grams/cm^3),

and  ) has SI units Pa.s/(kg/m) = m·s. The cgs physical unit for kinematic viscosity is the stokes (St), named after

) has SI units Pa.s/(kg/m) = m·s. The cgs physical unit for kinematic viscosity is the stokes (St), named after  , of the diffusing particles.

, of the diffusing particles.

, is the rate of change of velocity with distance perpendicular to the direction of movement.

, is the rate of change of velocity with distance perpendicular to the direction of movement.

.

. .

.

is the rate of change of mass

is the rate of change of mass is the average molecular speed

is the average molecular speed is the dynamic viscosity.

is the dynamic viscosity. .

.

0.0001 m·s and

0.0001 m·s and  1000 kg m then

1000 kg m then  0.1 kg·m·s = 0.1 Pa·s

0.1 kg·m·s = 0.1 Pa·s

= reference viscosity in (Pa·s) at reference temperature

= reference viscosity in (Pa·s) at reference temperature

= Sutherland's constant for the gaseous material in question

= Sutherland's constant for the gaseous material in question

= molecular mass (g/mol)

= molecular mass (g/mol) = the collision diameter (Å)

= the collision diameter (Å) = the maximum energy of attraction divided by the Boltzmann constant (K)

= the maximum energy of attraction divided by the Boltzmann constant (K) = the collision integral

= the collision integral

is the

is the

is the viscosity blending number of the blend.

is the viscosity blending number of the blend.

is activation energy,

is activation energy,  is the molar gas constant and

is the molar gas constant and  is approximately a constant.

is approximately a constant.

at low temperatures (in the glassy state) to a low value

at low temperatures (in the glassy state) to a low value  at high temperatures (in the liquid state). Depending on this change, amorphous materials are classified as either

at high temperatures (in the liquid state). Depending on this change, amorphous materials are classified as either

or

or

whereas fragile materials have

whereas fragile materials have

and

and  related to thermodynamic parameters of joining bonds of an amorphous material.

related to thermodynamic parameters of joining bonds of an amorphous material.

, this equation can be approximated by a

, this equation can be approximated by a  , then the two-exponential equation simplifies to an Arrhenius type equation:

, then the two-exponential equation simplifies to an Arrhenius type equation:

is the

is the  is the

is the  , the two-exponential equation also simplifies to an Arrhenius type equation:

, the two-exponential equation also simplifies to an Arrhenius type equation:

,

,

or

or  , depending on the convention used, measured in reciprocal poise (

, depending on the convention used, measured in reciprocal poise ( and

and  , the fluidity when

, the fluidity when

and

and  is the mole fraction of component

is the mole fraction of component  and

and  are the components pure viscosities.

are the components pure viscosities.

is specified by the velocity field

is specified by the velocity field  . The velocity at a small distance

. The velocity at a small distance  from point

from point

is shorthand for the dyadic product of the del operator and the velocity:

is shorthand for the dyadic product of the del operator and the velocity:

where

where  is shorthand for

is shorthand for  . Note that when the first and higher derivative terms are zero, the velocity of all fluid elements is parallel, and there are no viscous forces.

. Note that when the first and higher derivative terms are zero, the velocity of all fluid elements is parallel, and there are no viscous forces.

where:

where:

is the

is the  and the rate-of-strain tensor is then a linear combination of these two tensors:

and the rate-of-strain tensor is then a linear combination of these two tensors:

is the coefficient of bulk viscosity (or "second viscosity") and

is the coefficient of bulk viscosity (or "second viscosity") and  is the coefficient of (shear) viscosity.

is the coefficient of (shear) viscosity.

) must be added to the viscous stress tensor to obtain the total stress tensor for the fluid.

) must be added to the viscous stress tensor to obtain the total stress tensor for the fluid.

on an infinitesimal area

on an infinitesimal area  is then given by the usual relationship:

is then given by the usual relationship: