| Revision as of 00:16, 9 September 2008 edit96.52.44.169 (talk) →Hampstead← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:20, 9 September 2008 edit undo96.52.44.169 (talk) →EducationNext edit → | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

| In 1905, Blair's mother settled at ]. Eric was brought up in the company of his mother and sisters, and apart from a brief visit he did not see his father again until 1912. His mother's diary for 1905 indicates a lively round of social activity and artistic interests. The family moved to ] before World War I, and Eric became friendly with the Buddicom family, especially ]. When they first met, he was standing on his head in a field, and on being asked why he said, "You are noticed more if you stand on your head than if you are right way up". Jacintha and Eric read and wrote poetry and dreamed of becoming famous writers. He told her that he might write a book in similar style to that of ]'s ]. During this period, he enjoyed shooting, fishing, and birdwatching with Jacintha’s brother and sister.<ref name="autogenerated1">Jacintha Buddicom ''Eric and Us'' Frewin 1974.</ref> | In 1905, Blair's mother settled at ]. Eric was brought up in the company of his mother and sisters, and apart from a brief visit he did not see his father again until 1912. His mother's diary for 1905 indicates a lively round of social activity and artistic interests. The family moved to ] before World War I, and Eric became friendly with the Buddicom family, especially ]. When they first met, he was standing on his head in a field, and on being asked why he said, "You are noticed more if you stand on your head than if you are right way up". Jacintha and Eric read and wrote poetry and dreamed of becoming famous writers. He told her that he might write a book in similar style to that of ]'s ]. During this period, he enjoyed shooting, fishing, and birdwatching with Jacintha’s brother and sister.<ref name="autogenerated1">Jacintha Buddicom ''Eric and Us'' Frewin 1974.</ref> | ||

| ===Education=== | ===Education.=== | ||

| At the age of six, Eric Blair attended the ] parish school in ], remaining until he was eleven. His mother wanted him to have a ] education, but his family was not wealthy enough to afford the fees, making it necessary for him to obtain a ]. Ida Blair's brother Charles Limouzin, who lived on the South Coast, recommended ], ], ]. The headmaster undertook to help Blair to win the scholarship, and made a private financial arrangement which allowed Blair's parents to pay only half the normal fees. At St. Cyprian's, Blair first met ], who would himself become a noted writer and who, as the editor of '']'' magazine, would publish many of Orwell's essays. While at the school Blair wrote two poems that were published in his local newspaper<ref>Henley and South Oxfordshire Standard 2 October 1914</ref><ref>Henley and South Oxfordshire Standard 21 July 1916</ref>, came second to Connolly in the ], had his work praised by the school's external examiner, and earned scholarships to ] and ]. | At the age of six, Eric Blair attended the ] parish school in ], remaining until he was eleven. His mother wanted him to have a ] education, but his family was not wealthy enough to afford the fees, making it necessary for him to obtain a ]. Ida Blair's brother Charles Limouzin, who lived on the South Coast, recommended ], ], ]. The headmaster undertook to help Blair to win the scholarship, and made a private financial arrangement which allowed Blair's parents to pay only half the normal fees. At St. Cyprian's, Blair first met ], who would himself become a noted writer and who, as the editor of '']'' magazine, would publish many of Orwell's essays. While at the school Blair wrote two poems that were published in his local newspaper<ref>Henley and South Oxfordshire Standard 2 October 1914</ref><ref>Henley and South Oxfordshire Standard 21 July 1916</ref>, came second to Connolly in the ], had his work praised by the school's external examiner, and earned scholarships to ] and ]. | ||

Revision as of 00:20, 9 September 2008

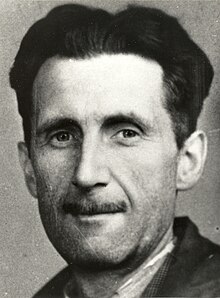

| Eric Arthur Blair | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pen name | George Orwell |

| Occupation | Writer; author, journalist |

| Notable works | Homage to Catalonia (1938) Animal Farm (1945) Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) |

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June, 1903 – 21 January 1950) was an English writer, who wrote under the pseudonym George Orwell.

His work is marked by a profound consciousness of social injustice, an intense dislike of totalitarianism, and a passion for clarity in language. He wrote in many different forms, including memoirs, histories, critical essays, opinion columns and book reviews, but his most famous works are two novels, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Biography

Early life

Eric Arthur Blair was born on 25 June 1903 in Motihari, Bengal Presidency, British India. His great-grandfather Charles Blair had been a wealthy plantation owner in Jamaica and his grandfather a clergyman. Although the gentility was passed down the generations, the prosperity was not; Blair described his family as "lower-upper-middle class". His father, Richard Walmesley Blair, worked in the Opium Department of the Indian Civil Service. His mother, Ida Mabel Blair (née Limouzin), grew up in Burma where her French father was involved in speculative ventures. Eric had two sisters; Marjorie, five years older, and Avril, five years younger. When Eric was one year old, Ida Blair took him to England.

In 1905, Blair's mother settled at Henley-on-Thames. Eric was brought up in the company of his mother and sisters, and apart from a brief visit he did not see his father again until 1912. His mother's diary for 1905 indicates a lively round of social activity and artistic interests. The family moved to Shiplake before World War I, and Eric became friendly with the Buddicom family, especially Jacintha Buddicom. When they first met, he was standing on his head in a field, and on being asked why he said, "You are noticed more if you stand on your head than if you are right way up". Jacintha and Eric read and wrote poetry and dreamed of becoming famous writers. He told her that he might write a book in similar style to that of H. G. Wells's A Modern Utopia. During this period, he enjoyed shooting, fishing, and birdwatching with Jacintha’s brother and sister.

Education.

At the age of six, Eric Blair attended the Anglican parish school in Henley-on-Thames, remaining until he was eleven. His mother wanted him to have a public school education, but his family was not wealthy enough to afford the fees, making it necessary for him to obtain a scholarship. Ida Blair's brother Charles Limouzin, who lived on the South Coast, recommended St Cyprian's School, Eastbourne, Sussex. The headmaster undertook to help Blair to win the scholarship, and made a private financial arrangement which allowed Blair's parents to pay only half the normal fees. At St. Cyprian's, Blair first met Cyril Connolly, who would himself become a noted writer and who, as the editor of Horizon magazine, would publish many of Orwell's essays. While at the school Blair wrote two poems that were published in his local newspaper, came second to Connolly in the Harrow History Prize, had his work praised by the school's external examiner, and earned scholarships to Wellington and Eton.

After a term at Wellington College, Blair transferred to Eton College, where he was a King's Scholar (1917–1921). His tutor was A. S. F. Gow, fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge who remained a source of advice later in his career. Blair was briefly taught French by Aldous Huxley who spent a short interlude teaching at Eton, but outside the classroom there was no contact between them. Cyril Connolly followed Blair to Eton, but because they were in separate years they did not associate with each other. Later, Blair wrote of having been relatively happy at Eton, because it allowed students much independence. His academic performance reports suggest that he neglected his studies, and various explanations have been offered for this. His parents could not afford to send him to university without another scholarship, and they concluded from the poor results that he would not be able to obtain one. Instead, it was decided that Blair should join the Indian Imperial Police. To do this, it was necessary to pass an entrance examination. His father had retired to Southwold, Suffolk by this time and Blair was enrolled at a "crammer" there called "Craighurst" where he brushed up on his classics, English and History. Blair passed the exam, coming seventh out of twenty-seven.

Burma

Blair's grandmother lived at Moulmein, and with family connections in the area, his choice of posting was Burma. In October 1922, he sailed on board SS Herefordshire via the Suez Canal and Ceylon to join the Indian Imperial Police in Burma. A month later he arrived at Rangoon and made the journey to Mandalay the site of the police training school. After a short posting at Maymyo Burma's principal hill station he was posted to the remote area of Mayaungma at the beginning of 1924. His imperial policeman's life gave him considerable responsibilities for a young man of his age while his contemporaries were still at university in England. He was then posted to Twante where as sub-divisional officer he was responsible for the security of some 200,000 people. At the end of 1924 he was promoted to Assistant District Superintendent and posted to Syriam, which was closer to Rangoon and in September 1925 went to Insein the home of the second-largest jail in Burma. He moved to Moulmein where his grandmother lived in April 1926 and at the end of that year went on to Katha. There he contracted Dengue fever in 1927. He was entitled to leave in England in that year and in view of his illness was allowed to go home in July. While on leave in England in 1927, he reappraised his life and resigned from the Indian Imperial Police with the intention of becoming a writer. The Burma police experience yielded the novel Burmese Days (1934) and the essays "A Hanging" (1931) and "Shooting an Elephant" (1936).

The early writings

In England, he settled back in the family home at Southwold, renewing acquaintance with local friends and attending an Old Etonian dinner. He visited his old tutor Gow at Cambridge for advice on becoming a writer, and as a result he decided to move to London. Ruth Pitter, a family acquaintance, helped him find lodgings and by the end of 1927 he had moved into rooms in Portobello Road (a blue plaque commemorates his residence there). Pitter took a vague interest in his writing as he set out to collect literary material on a social class as different from his own as were the natives of Burma. Following the precedent of Jack London, whom he admired, he started his exploratory expeditions to the poorer parts of London. On his first outing he set out to Limehouse Causeway (spending his first night in a common lodging house, possibly George Levy's 'kip'. For a while he "went native" (in his own country), dressing like a tramp, making no concessions to middle class mores and expectations, and he recorded his experiences of the low life for use in "The Spike", his first published essay, and the latter half of his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933).

In spring of 1928, he moved to Paris, where the comparatively low cost of living and bohemian lifestyle offered an attraction for many aspiring writers. His Aunt Nellie Limouzin also lived there and gave him social and, if necessary, financial support. He worked on novels, but only Burmese Days survives from that activity. More successful as a journalist, he published articles in Monde (not to be confused with Le Monde), G. K.'s Weekly and Le Progres Civique (founded by Le Cartel des Gauches). He fell seriously ill in March 1929 and shortly afterwards had all his money stolen from the lodging house. Whether through necessity or simply to collect material, he undertook menial jobs like dishwashing in a fashionable hotel on the rue de Rivoli providing experiences to be used in Down and Out in Paris and London. In August 1929 he sent a copy of "The Spike" to New Adelphi magazine in London. This was owned by John Middleton Murry who had released editorial control to Max Plowman and Sir Richard Rees. Plowman accepted the work for publication.

In December 1929, after a year and three quarters in Paris, Blair returned to England and went directly to his parents' house in Southwold, which was to remain his base for the next five years. The family was well established in the local community, and his sister Avril was running a tea house in the town. He became acquainted with many local people including a local gym teacher, Brenda Salkield, the daughter of a clergyman. Although Salkield rejected his offer of marriage she was to remain a friend and regular correspondent about his work for many years. He also renewed friendships with older friends such as Dennis Collings, whose girlfriend Eleanor Jacques was also to play a part in his life. In the spring he had a short stay in Leeds with his sister Marjorie and her husband Humphrey Dakin whose regard for Blair was as unappreciative then as when he knew him as a child. Blair was undertaking some review work for the Adelphi and acting as a private tutor to a handicapped child at Southwold. He followed this up by tutoring a family of three boys one of whom, Richard Peters, later became a distinguished academic. He went painting and bathing on the beach, and there he met Mabel and Francis Fierz who were later to influence his career. Over the next year he visited them in London often meeting their friend Max Plowman. Other homes available to him were those of Ruth Pitter and Richard Rees. These acted as places for him to "change" for his sporadic tramping expeditions where one of his jobs was to do domestic work at a lodgings for half a crown a day.Meanwhile, he regularly contributed to New Adelphi magazine, with The Hanging appearing in August 1931. In August and September 1931 his explorations extended to following the East End tradition of working in the Kent hop fields (an activity which his lead character in "A Clergyman's Daughter" also engages in). At the end of this, he ended up in the Tooley Street kip, but could not stand it for long and with a financial contribution from his parents moved to Windsor Street where he stayed until Christmas. Hop Picking by Eric Blair appeared in October 1931in the New Statesman, where Cyril Connolly was on the staff. Mabel Fierz put him in contact with Leonard Moore who was to become his literary agent. At this time Jonathan Cape rejected A Scullions Diary his first version of Down and Out, and on the advice of Richard Rees he offered it to Faber & Faber. T. S. Eliot then an editorial director also rejected it. To conclude the year Blair attempted another exporatory venture of getting himself arrested so that he could spend Christmas in prison, but the relevant authorities did not cooperate and he returned home to Southwold after two days in a police cell.

Teaching

Blair then took a job teaching at the Hawthorne High School for Boys in Hayes, West London. This was a small school that provided private schooling for local tradesmen and shopkeepers and comprised only 20 boys and one other master. While at the school he became friendly with the local curate and became involved with the local church. Mabel Fierz had pursued matters with Moore, and at the end of June 1932, Moore told Blair that Victor Gollancz was prepared to publish A Scullions Diary for a £40 advance. Gollancz had only recently founded the publishing house which was an outlet for radical and socialist works. At the end of the school summer term in 1932 Orwell returned to Southwold, where his parents had been able to buy their own home as a result of a legacy . Blair and his sister Avril spent the summer holidays making the house habitable while he also worked on Burmese Days. He was also spending time with Eleanor Jacques but her attachment to Dennis Collings remained an obstacle to his hopes of a more serious relationship.Clink appeared in the August number of Adelphi. He returned to teaching at Hayes and prepared for the publication of his work now known as Down and Out in Paris and London which he wished to publish under an assumed name. In a letter to Moore (dated 15 November {1932]]) he left the choice of pseudonym to him and to Victor Gollancz. Four days later, he wrote to Moore, suggesting these pseudonyms: P. S. Burton (a tramping name), Kenneth Miles, George Orwell, and H. Lewis Allways.He finally adopted the nom de plume George Orwell because as he told Eleanor Jacques, "It is a good round English name." Down and Out in Paris and London was published on 9 January 1933 but Blair was back at the school at Hayes. He had little free time and was still working on Burmese Days. Down and Out was successful and it was published by Harper and Brothers in New York.

In the summer Blair finished at Hawthornes to take up a teaching job at Frays College, at Uxbridge, Middlesex. This was a much larger establishment with 200 pupils and a full complement of staff. He acquired a motorcycle and took trips in the surrounding countryside. On one of these expeditions he became soaked and caught a chill which developed into pneumonia. He was taken to Uxbridge Cottage Hospital where for a time his life was believed to be in danger. When he was discharged in January 1934, he returned to Southwold to convalesce and, supported by his parents, never returned to teaching. He was disapponted when Gollancz turned down Burmese Days, mainly on the grounds of potential libel actions but Harpers were prepared to publish it in America. Meanwhile back at home Blair started work on the novel A Clergyman's Daughter drawing upon his life as a teacher and on life in Southwold. Eleanor Jacques was now married and had gone to Singapore and Brenda Salkield had left for Ireland, so Blair was relatively lonely in Southwold - pottering on the allotments, walking alone and spending time with his father. Eventually in October, after sending A Clergyman's Daughter to Moore, he left for London to take a job that had been found for him by his Aunt Nellie Limouzin.

Hampstead

This job was as a part-time assistant in "Booklover's Corner", a second-hand bookshop in Hampstead run by Francis and Myfanwy Westrope who were friends of Nellie Limouzin in the Esperanto movement. The Westropes had an easy-going outlook and provided him with comfortable accommodation at Warwick Mansions, Pond Street. He was job-sharing with Jon Kimche who also lived with the Westropes. Blair worked at the shop in the afternoons, having the mornings free to write and the evenings to socialise. These experiences provided background for the novel Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936). As well as the various guests of the Westropes, he was able to enjoy the company of Richard Rees and the Adelphi writers and Mabel Fierz. He had also met in the bookshop a girl called Kay Ekevall who provided female company. The Westropes and Kimche were members of the Independent Labour Party although at this time Blair was not seriously politically aligned. He was writing for the "Adelphi" and dealing with pre-publication issues with A Clergymans Daughter and Burmese Days. At the beginning of 1935 he had to move out of Warwick Mansions, and Mabel Fierz found him a flat in Parliament Hill. A Clergyman's Daughter was published on the 11th March 1935. In the spring of 1935 Blair met his future wife Eileen O'Shaughnessy when his landlady, who was studying at the University of London, invited some of her fellow students. Around this time, Blair had started to write reviews for the New English Weekly. In July, Burmese Days was published and following Connolly's review of it in the New Statesman, the two re-established contact. In August Blair moved into a flat in Kentish Town, which he shared with Michael Sayer and Rayner Heppenstall. He was working on Keep the Aspidistra Flying, and also tried to write a serial for the News Chronicle, which was an unsuccessful venture. By October 1935 his flat-mates had moved out, and he was struggling to pay the rent on his own...

The Road to Wigan Pier

At this time, Victor Gollanz suggested he spend a short time investigating social conditions in economically depressed northern England. Two years earlier J. B. Priestley had written of England north of the Trent and this had stimulated an interest in reportage. Furthermore the depression had spawned a number of working class writers from the north of England.

On January 31 1936, Orwell set out by public transport and on foot via Coventry, Stafford, the Potteries and Macclesfield, reaching Manchester. Arriving after the banks had closed, he had to stay in a common lodging house. Next day he picked up a list of contact addresses sent by Richard Rees. One of these, a Trade Union official Frank Meade suggested Wigan where he spent February staying in dirty lodgings over a Tripe shop. At Wigan he gained entry to many houses to see how people lived, took systematic notes of housing conditions and wages earned, went down a coal mine, and spent days in the local public library consulting public health records and reports on mine working conditions. During this time he was distracted by dealing with libel and stylistic issues relating to Keep the Aspidistra Flying. He made a quick visit to Liverpool and spent March in South Yorkshire, spending time in Sheffield and Barnsley. As well as visiting mines and social conditions, he attended meetings of the Communist Party and of Oswald Mosley where he saw the tactics of the Blackshirts. He punctuated stay with visits to his sister at Headingley, during which he visited the Bronte Parsonage at Haworth.

His investigations gave rise to The Road to Wigan Pier published in 1937. The first half of this work documents his social investigations of Lancashire and Yorkshire. It begins with an evocative description of working life in the coal mines. The second half is a long essay of his upbringing, and the development of his political conscience, including a denunciation of the Left's irresponsible elements. Publisher Gollancz feared the second half would offend Left Book Club readers and inserted a mollifying preface to the book while Orwell was in Spain.

Orwell needed somewhere where he could concentrate on writing his book, and once again help was provided by Aunt Nellie who was living in a cottage at Wallington, Hertfordshire. It was a very small cottage called the "Stores" with almost no modern facilities in a tiny village. Orwell took over the tenancy and had moved in by April 2 1936. As well as writing, he spent hours working on the garden and investigated the possibility of reopening the Stores as a village shop. To complete his domestic idyll, Orwell married Eileen O'Shaughnessy on June 9. Shortly afterwards, the political crisis began in Spain and Orwell followed developments closely. At the end of the year, concerned by Francisco Franco's Falangist uprising, Orwell decided to go Spain to take part in the Spanish Civil War on the the Republican side. He needed an introduction and applied unsuccessfully to the British Communist Party. Instead he used his ILP contacts to get a letter of introduction to John McNair in Barcelona. He was advised to get safe passage from the Spanish Embassy in Paris.

The Spanish Civil War, and Catalonia

Orwell set out for Spain on about the 23rd December, dining with Henry Miller in Paris on the way. A few days later at Barcelona, he met John McNair of the ILP Office who quoted him: "I've come to fight against Fascism". Orwell stepped into a complex political situation in Catalonia. The Republican government was supported by a number of factions with conflicting aims, including the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM - Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista), the anarcho-syndicalist CNT and the Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia a wing of the Spanish Communist Party, which was backed by Soviet arms and aid. The Independent Labour Party contingent was linked to the POUM and so Orwell joined the POUM. After a time at the Lenin Barracks in Barcelona he was sent to the relatively quiet Aragon Front under George Kopp. In January 1937 he was at Alcubierre 1500 feet above sea level in the depth of winter. There was very little military action, a lack of equipment and deprivations which made it uncomfortable. Orwell, with his Cadet Corps and police training was quickly made a corporal but on the arrival of a British ILP Contingent was sent with them to Monte Oscuro. Others in the party were Bob Edwards, Stafford Cottman and Jack Branthwaite. The unit were then sent on to Huesca. Meanwhile back in England Eileen had been handling the issues relating to the publication of The Road to Wigan Pier before setting out for Spain herself, leaving Aunt Nellie Limouzin to look after The Stores. Eileen volunteered for a post in John McNair's office and with the help of George Kopp paid visits to her husband bringing him English tea, chocolate and cigars. Orwell had to spend some days in hospital with a poisoned hand and had most of his possessions stolen by the staff. He returned to the front and saw some action in night attack on the Nationalist trenches where he chased an enemy soldier with a bayonet and bombed an enemy rifle position.

In April, Orwell returned to Barcelona where he applied to join the International Brigades to become involved in fighting closer to Madrid. However this was the time of Barcelona May Days and Orwell was caught up in the factional fighting. He spent much of the time on a roof, with a stack of novels, but encountered Jon Kimche from his Hampstead days during the stay. Instead of joining the International Brigades, he decided to return to the Aragon Front. Orwell was considerably taller than the Spanish fighters and was warned against standing against the trench parapet. One morning a sniper's bullet caught him in the throat. Unable to speak, and with blood pouring from his mouth, Orwell was stretchered to Siétamo, loaded on an ambulance and after a bumpy journey via and Barbostro arrived at the hospital at Lerida. He recovered sufficiently to get up and on the 27th May 1937 was sent on to Tarragona and two days later to a POUM sanatorium in the suburbs of Barcelona.The bullet had missed his main artery by the barest margin and his voice was barely audible. He received electrotherapy treatment and was declared medically unfit for service. By the middle of June the political situation in Barcelona had deteriorated and the POUM - seen by the Communists as a Trotskyist organisation - was outlawed and under attack. Members, including Kopp, were under arrest and others were in hiding. Orwell and his wife were under threat and had to lay low, although they broke cover to try to help Kopp. Finally with their passports in order, they escaped from Spain by train, diverting to Banyuls-sur-Mer for a short stay before returning to England. Orwell's experiences in the Spanish Civil War gave rise to Homage to Catalonia.

Orwell returned to England in June 1937, and after a brief stay in London he returned to Wallington, which he found in disarray after his absence. He acquired goats, a rooster he called "Henry Ford", and a dog he called "Marx" and settled down to animal husbandry and writing. However by March 1938 his health had deteriorated and he was admitted to a sanitorium at Aylesford, Kent. He appeared to be suffering from tuberculosis and stayed in the sanitorium until September. In the latter part of his stay he was able to go for walks in the countryside and study nature. After leaving the sanitorium, he and his wife set out for Morocco where they lived for half a year to avoid the English winter and recover his health.

In that time, he wrote Coming Up for Air, his last novel before World War II. It is the most English of his novels; alarums of war mingle with images of idyllic Thames-side Edwardian childhood of protagonist George Bowling. The novel is pessimistic; industrialism and capitalism have killed the best of Old England, and there were great, new external threats. In homely terms, Bowling posits the totalitarian hypotheses of Borkenau, Orwell, Silone and Koestler: "Old Hitler's something different. So's Joe Stalin. They aren't like these chaps in the old days who crucified people and chopped their heads off and so forth, just for the fun of it ... They're something quite new — something that's never been heard of before".

World War II and Animal Farm

After the Spanish ordeal, and writing about it, Orwell's formation ended; his finest writing, best essays, and great fame lay ahead. In 1940, Orwell closed his Wallington house, and he and Eileen moved to No. 18 Dorset Chambers, Chagford Street, in the genteel Marylebone neighbourhood near Regent's Park, central London, Orwell supporting himself as a freelance reviewer for the New English Weekly (mainly), Time and Tide, and the New Statesman. Soon after the war began, he joined the Home Guard (and was awarded the "British Campaign Medals/Defence Medal") attending Tom Wintringham's home guard school and championing Wintringham's socialist vision for the Home Guard.

In 1941, Orwell worked for BBC's Eastern Service, supervising Indian broadcasts meant to stimulate India's war participation against the approaching Japanese army. About being a propagandist, he wrote of feeling like "an orange that's been trodden on by a very dirty boot". Still, he devoted much effort to the opportunity of working closely with the likes of T. S. Eliot, E. M. Forster, Mulk Raj Anand, and William Empson; the war-time Ministry of Information, at Senate House, University of London, inspired the Ministry of Truth in the novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Orwell's BBC resignation followed a report confirming his fears about the broadcasts: few Indians listened. He wanted to become a war correspondent, and was impatient to begin working on Animal Farm. Despite the good salary, he resigned from BBC in September 1943, and in November became literary editor of the left-wing weekly magazine Tribune, then edited by Aneurin Bevan and Jon Kimche (Kimche had been Box to Orwell's Cox when they were half-time assistants at the Booklover's Corner book shop in Hampstead, 1934–35). Orwell was on staff until early 1945, writing the regular column "As I Please". Anthony Powell and Malcolm Muggeridge had returned from overseas to finish the war in London; the three regularly lunched together at either the Bodega, off the Strand, or the Bourgogne, in Soho, sometimes joined by Julian Symons (then seemingly a true disciple of Orwell) and David Astor, editor-owner of The Observer.

In 1944, Orwell finished the anti-Stalinist allegory Animal Farm published (Britain, 17 August 1945, U.S., 26 August 1946) to critical and popular success. Harcourt Brace Editor Frank Morley went to Britain soon after the war to learn what currently interested readers, clerking a week or so at the Cambridge book shop Bowes and Bowes. The first day, customers continually requested a sold-out book — the second impression of Animal Farm; on reading the shop's remaining copy, he went to London and bought the American publishing rights; the royalties were George Orwell's first, proper, adult income.

With Animal Farm at the printer's, with war's end in view, Orwell's desire to be in the thick of the action quickened. David Astor asked him to be the Observer war correspondent reporting the liberation of France and the early occupation of Germany; Orwell quit Tribune.

He and Astor were close; Astor is believed to be the model for the rich publisher in Keep the Aspidistra Flying; Orwell strongly influenced Astor's editorial policies. Astor died in 2001 and is buried in the grave beside Orwell's. Orwell never revealed his pen name, keeping his identity secret and thinking his work did not need a revealed author.

Nineteen Eighty-Four and final years

Orwell and his wife adopted a baby boy, Richard Horatio Blair, born in May 1944. Orwell was taken ill again in Cologne in spring 1945. While he was sick there, his wife died in Newcastle during an operation to remove a tumour. She had not told him about this operation due to concerns about the cost and the fact that she thought she would make a speedy recovery.

For the next four years Orwell mixed journalistic work — mainly for the Tribune, the Observer and the Manchester Evening News, though he also contributed to many small-circulation political and literary magazines — with writing his best-known work, Nineteen Eighty-Four, which was published in 1949. Originally, Orwell was undecided between titling the book The Last Man in Europe and Nineteen Eighty-Four but his publisher, Fredric Warburg, helped him choose. The title was not the year Orwell had initially intended. He first set his story in 1980, but, as the time taken to write the book dragged on (partly because of his illness), that was changed to 1982 and, later, to 1984.

He wrote much of the novel while living at Barnhill, a remote farmhouse on the island of Jura which lies in the Gulf stream off the west coast of Scotland. It was an abandoned farmhouse with outbuildings near to the northern end of the island, situated at the end of a five-mile (8 km), heavily rutted track from Ardlussa, where the laird, or landowner, Margaret Fletcher lived, and where the paved road, the only one on the island, came to an end.

In 1948, he co-edited a collection entitled British Pamphleteers with Reginald Reynolds.

In 1949, Orwell was approached by a friend, Celia Kirwan, who had just started working for a Foreign Office unit, the Information Research Department, which the Labour government had set up to publish anti-communist propaganda. He gave her a list of 37 writers and artists he considered to be unsuitable as IRD authors because of their pro-communist leanings. The list, not published until 2003, consists mainly of journalists (among them the editor of the New Statesman, Kingsley Martin) but also includes the actors Michael Redgrave and Charlie Chaplin. Orwell's motives for handing over the list are unclear, but the most likely explanation is the simplest: that he was helping a friend in a cause — anti-Stalinism — that they both supported. There is no indication that Orwell abandoned the democratic socialism that he consistently promoted in his later writings — or that he believed the writers he named should be suppressed. Orwell's list was also accurate: the people on it had all made pro-Soviet or pro-communist public pronouncements. In fact, one of the people on the list, Peter Smollett, the head of the Soviet section in the Ministry of Information, was later (after the opening of KGB archives) proven to be a Soviet agent, recruited by Kim Philby, and "almost certainly the person on whose advice the publisher Jonathan Cape turned down Animal Farm as an unhealthily anti-Soviet text", although Orwell was unaware of this.

In October 1949, shortly before his death, he married Sonia Brownell.

Death

Orwell died in London from tuberculosis, at the age of 46. He was in and out of hospitals for the last three years of his life. Despite his atheism Orwell requested to be buried in accordance with the Anglican rite; he was interred in All Saints' Churchyard, Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire with the simple epitaph: "Here lies Eric Arthur Blair, born June 25, 1903, died January 21, 1950"; no mention is made on the gravestone of his more famous pen-name. He had wanted to be buried in the graveyard of the closest church to wherever he happened to die, but the graveyards in central London had no space. Fearing that he might have to be cremated, against his wishes, his widow appealed to his friends to see if any of them knew of a church with space in its graveyard. Orwell's friend David Astor lived in Sutton Courtenay and negotiated with the vicar for Orwell to be buried there, although he had no connection with the village.

Orwell's son, Richard Blair, was raised by an aunt after his father's death. He maintains a low public profile, though he has occasionally given interviews about the few memories he has of his father. Blair worked for many years as an agricultural agent for the British government.

Legacy

Work

During most of his career, Orwell was best known for his journalism, in essays, reviews, columns in newspapers and magazines and in his books of reportage: Down and Out in Paris and London (describing a period of poverty in these cities), The Road to Wigan Pier (describing the living conditions of the poor in northern England, and the class divide generally) and Homage to Catalonia. According to Irving Howe, Orwell was "the best English essayist since Hazlitt, perhaps since Dr Johnson."

Modern readers are more often introduced to Orwell as a novelist, particularly through his enormously successful titles Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four. The former is often thought to reflect developments in the Soviet Union after the Russian Revolution; the latter, life under totalitarian rule. Nineteen Eighty-Four is often compared to Brave New World by Aldous Huxley; both are powerful dystopian novels warning of a future world filled with state control, the former was written later and considers perpetual war preparation in a nuclear age; the latter is more optimistic.

Literary influences

In an autobiographical sketch Orwell sent to the editors of Twentieth Century Authors in 1940, he wrote:

Elsewhere, Orwell strongly praised the works of Jack London, especially his book The Road. Orwell's investigation of poverty in The Road to Wigan Pier strongly resembles that of Jack London's The People of the Abyss, in which the American journalist disguises himself as an out-of-work sailor in order to investigate the lives of the poor in London. In the essay "Politics vs. Literature: An Examination of Gulliver's Travels" (1946) he wrote: "If I had to make a list of six books which were to be preserved when all others were destroyed, I would certainly put Gulliver's Travels among them." Other writers admired by Orwell included Ralph Waldo Emerson, G. K. Chesterton, George Gissing, Graham Greene, Herman Melville, Henry Miller, Tobias Smollett, Mark Twain, Joseph Conrad and Yevgeny Zamyatin. He was both an admirer and a critic of Rudyard Kipling, praising Kipling as a gifted writer and a "good bad poet" whose work is "spurious" and "morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting," but undeniably seductive and able to speak to certain aspects of reality more effectively than more enlightened authors.

Literary criticism

Throughout his life Orwell continually supported himself as a book reviewer, writing works so long and sophisticated they have had an influence on literary criticism. He wrote in the conclusion to his 1940 essay on Charles Dickens

- "When one reads any strongly individual piece of writing, one has the impression of seeing a face somewhere behind the page. It is not necessarily the actual face of the writer. I feel this very strongly with Swift, with Defoe, with Fielding, Stendhal, Thackeray, Flaubert, though in several cases I do not know what these people looked like and do not want to know. What one sees is the face that the writer ought to have. Well, in the case of Dickens I see a face that is not quite the face of Dickens's photographs, though it resembles it. It is the face of a man of about forty, with a small beard and a high colour. He is laughing, with a touch of anger in his laughter, but no triumph, no malignity. It is the face of a man who is always fighting against something, but who fights in the open and is not frightened, the face of a man who is generously angry — in other words, of a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls."

Woodcock suggested that the last two sentences characterised Orwell as much as his subject.

Rules for writers

In "Politics and the English Language," George Orwell provides six rules for writers:

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive voice where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

Influence on the English language

Some of Nineteen Eighty-Four's lexicon has entered into the English language. The word 'Orwellian' usually refers specifically to this novel.

- Orwell expounded on the importance of honest and clear language (and, conversely, on how misleading and vague language can be a tool of political manipulation) in his 1946 essay Politics and the English Language. The language of Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four is Newspeak: a thoroughly politicised and obfuscatory language designed to make independent thought impossible by limiting acceptable word choices.

- Another phrase is 'Big Brother', or 'Big Brother is watching you'. Today, security cameras are often thought to be modern society's big brother. The current television reality show Big Brother carries that title because of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

- The same novel spawned the title of another television series, Room 101.

- The phrase 'thought police' is also derived from Nineteen Eighty-Four, and might be used to refer to any alleged violation of the right to the free expression of opinion. It is particularly used in contexts where free expression is proclaimed and expected to exist.

- Doublethink is a Newspeak term from Nineteen Eighty-Four, and is the act of holding two contradictory beliefs simultaneously, fervently believing both.

Variations of the slogan "all animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others", from Animal Farm, are sometimes used to satirise situations where equality exists in theory and rhetoric but not in practice with various idioms. For example, an allegation that rich people are treated more leniently by the courts despite legal equality before the law might be summarised as "all criminals are equal, but some are more equal than others". This appears to echo the phrase Primus inter pares - the Latin for "First amongst equals", which is usually applied to the head of a democratic state.

Although the origins of the term are debatable, Orwell may have been the first to use the term cold war. He used it in an essay titled "You and the Atomic Bomb" on October 19, 1945 in Tribune, he wrote:

- "We may be heading not for general breakdown but for an epoch as horribly stable as the slave empires of antiquity. James Burnham's theory has been much discussed, but few people have yet considered its ideological implications — this is, the kind of world-view, the kind of beliefs, and the social structure that would probably prevail in a State which was at once unconquerable and in a permanent state of 'cold war' with its neighbours."

Personal life

Childhood

Jacintha Buddicom's account "Eric & Us" provides an independent insight into the Blair's childhood. She quoted his sister Avril that "he was essentially an aloof, undemonstrative person" and said herself of his friendship with the Buddicoms "I do not think he needed any other friends beyond the schoolfriend he occasionally and appreciatively referred to as 'CC'". Cyril Connolly provides an account of Blair as a child in Enemies of Promise. Years later, Blair mordantly recalled his Prep School in the essay "Such, Such Were the Joys" claiming among other things that he "was made to study like a dog" to earn a scholarship, which he alleged that was solely to enhance the school's prestige with parents. Jacintha Buddicom repudiated Orwell's schoolboy misery described in the essay stating that "he was a specially happy child".

Connoly remarked of him as a schoolboy "The remarkable thing about Orwell was that alone among the boys he was an intellectual and not a parrot for he thought for himself". At Eton his former headmaster's son observed "He was extremely argumentative - about anything - and criticising the masters and criticising the other boys...We enjoyed arguing with him. He would generally win the arguments - or think he had anyhow." Roger Mynors concurs "Endless arguments about all sorts of things, in which he was one of the great leaders. He was one of those boys who thought for himself..."

Blair liked to carry out practical jokes. Buddicom recalls him swinging from the luggage rack in a railway carriage like an orang-utang to frighten a woman passenger out of the compartment At Eton he played tricks on his master in house, among which was to enter a spoof advertisement in a College magazine implying pederasty. Gow, his tutor said he "made himself as big a nuisance as her could" and "was a very unattractive boy". Later Blair was expelled from the crammer at Southwold for sending a dead rat as a birthday present to the town surveyor In one of his As I Please essays he refers to a protracted joke when he answered an advertisement for a woman who claimed a cure for obesity.

Blair had an enduring interest in natural history which stemmed from his childhood. In letters from school he wrote about caterpillars and butterflies. and Buddicom recalls his keen interest in ornithology. He also enjoyed fishing and shooting rabbits, and conducting experiments as in cooking a hedgehog or shooting down a jackdaw from the Eton roof to dissect it. His zeal for scientific experiments extended to explosives - again Buddicom recalls a cook giving notice because the noise. Later in Southwold his sister Avril recalled him blowing up the garden. When teaching he enthused his students with his nature-rambles both at Southwold and Hayes His adult diaries are permeated with his observations on nature.

Relationships

Buddicom and Blair lost touch shortly after he went to Burma, and she became unsympathetic towards him because of letters he wrote complaining about his life. She ceased replying.

Mabel Fierz who later became his confidante said "He used to say the one thing he wished in this world was that he'd been attractive to women. He liked women and had many girlfriends I think in Burma. He had a girl in Southwold and another girl in London. He was rather a womaniser, yet he was afraid he wasn't attractive."

Brenda Salkield (Southwold) preferred friendship to any deeper relationship and maintained a correspondence with Blair for many years, particularly as a sounding board for his ideas. She wrote "He was a great letter writer. Endless letters, And I mean when he wrote you a letter he wrote pages." His corrspondence with Eleanor Jacques was more prosaic, dwelling on a closer relationship and referring to past assignments or planning future ones in London and Burnham Beeches.

Eileen O'Shaughnessy was warned off Orwell by friends who warned that she did not know what she was taking on. After her death during a hysterectomy, in a letter to a friend, Orwell refers to her as 'a faithful old stick'; the depth of his love for her remains ambiguous. Eileen's symptoms may partly account for Orwell's infidelities in the war's last years, but, in a letter to a woman to whom he proposed marriage: 'I was sometimes unfaithful to Eileen, and I also treated her badly, and I think she treated me badly, too, at times, but it was a real marriage, in the sense that we had been through awful struggles together and she understood all about my work, etc.'

Orwell was very lonely after Eileen's death, and desperate for a wife, both as companion for himself and as mother for Richard; he proposed marriage to four women, eventually, Sonia Brownwell accepted.

Political views

Orwell's political views shifted over time, but he was a man of the political left throughout his life as a writer. In his earlier days he occasionally described himself as a "Tory anarchist". His time in Burma made him a staunch opponent of imperialism, and his experience of poverty while researching Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier turned him into a socialist. "Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it," he wrote in 1946.

It was the Spanish Civil War that played the most important part in defining his socialism. Having witnessed the success of the anarcho-syndicalist communities, and the subsequent brutal suppression of the anarcho-syndicalists and other revolutionaries by the Soviet-backed Communists, Orwell returned from Catalonia a staunch anti-Stalinist and joined the Independent Labour Party.

At the time, like most other left-wingers in the United Kingdom, he was still opposed to rearmament against Nazi Germany — but after the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and the outbreak of the Second World War, he changed his mind. He left the ILP over its pacifism and adopted a political position of "revolutionary patriotism". He supported the war effort but detected (wrongly as it turned out) a mood that would lead to a revolutionary socialist movement among the British people. "We are in a strange period of history in which a revolutionary has to be a patriot and a patriot has to be a revolutionary," he wrote in Tribune, the Labour left's weekly, in December 1940.

By 1943, his thinking had moved on. He joined the staff of Tribune as literary editor, and from then until his death was a left-wing (though hardly orthodox) Labour-supporting democratic socialist. He canvassed for the Labour Party in the 1945 general election and was broadly supportive of its actions in office, though he was sharply critical of its timidity on certain key questions and despised the pro-Soviet stance of many Labour left-wingers.

Although he was never either a Trotskyist or an anarchist, he was strongly influenced by the Trotskyist and anarchist critiques of the Soviet regime and by the anarchists' emphasis on individual freedom. He wrote in The Road to Wigan Pier that 'I worked out an anarchistic theory that all government is evil, that the punishment always does more harm than the crime and the people can be trusted to behave decently if you will only let them alone.' In typical Orwellian style, he continues to deconstruct his own opinion as 'sentimental nonsense'. He continues 'it is always necessary to protect peaceful people from violence. In any state of society where crime can be profitable you have got to have a harsh criminal law and administer it ruthlessly'. Many of his closest friends in the mid-1940s were part of the small anarchist scene in London.

Orwell had little sympathy with Zionism and opposed the creation of the state of Israel. In 1945, Orwell wrote that "few English people realise that the Palestine issue is partly a colour issue and that an Indian nationalist, for example, would probably side with the Arabs".

While Orwell was concerned that the Palestinian Arabs be treated fairly, he was equally concerned with fairness to Jews in general: writing in the spring of 1945 a long essay titled "Antisemitism in Britain," for the "Contemporary Jewish Record." Antisemitism, Orwell warned, was "on the increase," and was "quite irrational and will not yield to arguments." He thought "the only useful approach" would be a psychological one, to discover "why" antisemites could "swallow such absurdities on one particular subject while remaining sane on others." (pp 332-341, As I Please: 1943-1945.) In his magnum opus, Nineteen Eighty-Four, he showed the Party enlisting antisemitic passions in the Two Minute Hates for Goldstein, their archetypal traitor.

Orwell was also a proponent of a federal socialist Europe, a position outlined in his 1947 essay 'Toward European Unity', which first appeared in Partisan Review.

Orwell publicly defended P. G. Wodehouse against charges of being a Nazi sympathiser; a defence based on Wodehouse's lack of interest in and ignorance of politics.

Intelligence

The Special Branch in the UK, the police intelligence group, spied on Orwell during the greater part of his life.. The dossier published by Britain's National Archives mentions that according to one investigator, Orwell's tendency of clothing himself "in Bohemian fashion," revealed that the author was "a Communist":

"This man has advanced Communist views, and several of his Indian friends say that they have often seen him at Communist meetings. He dresses in a bohemian fashion both at his office and in his leisure hours."

Conversely, there has been speculation about the extent of Orwell's links to Britain's secret service, MI5, and some have even claimed that he was in the service's employ. The evidence for this claim is contested.

Orwell also had an NKVD file due to his involvement with the POUM militia during the Spanish Civil War.

Recollections

Ruth Pitter recalls his embryonic writing whilst living in the lodgings she found for him on Portobello Road.

That winter was very cold. Orwell had very little money, indeed. I think he must have suffered in that unheated room, after the climate of Burma ... Oh yes, he was already writing. Trying to write that is – it didn't come easily ... To us, at that time, he was a wrong-headed young man who had thrown away a good career, and was vain enough to think he could be an author. But the formidable look was not there for nothing. He had the gift, he had the courage, he had the persistence to go on in spite of failure, sickness, poverty, and opposition, until he became an acknowledged master of English prose.

In The Road to Wigan Pier he writes of tramping and poverty:

When I thought of poverty, I thought of it in terms of brute starvation. Therefore my mind turned immediately towards the extreme cases, the social outcasts: tramps, beggars, criminals, prostitutes. These were the 'lowest of the low', and these were the people with whom I wanted to get into contact. What I profoundly wanted at that time was to find some way of getting out of the respectable world altogether.

Orwell had a difficult relationship with his original publisher, Victor Gollancz. When Gollancz wrote an apologetic preface to The Road to Wigan Pier, Orwell wrote to thank him but commented "of course I could have answered some of the criticisms you made." Gollancz also annoyed Orwell by refusing to publish Animal Farm on the grounds that it was too critical of the Soviet Union.

Bob Edwards, who fought with him in Spain, said: 'He had a phobia against rats. We got used to them. They used to gnaw at our boots during the night, but George just couldn't get used to the presence of rats and one day, late in the evening, he caused us great embarrassment ... he got out his gun and shot it ... the whole front, and both sides, went into action.'

On Sundays, Orwell liked very rare roast beef, and Yorkshire pudding dripping with gravy, and good Yarmouth kippers at high tea. (p.501) ... He liked his tea, as well as his tobacco, strong, sometimes putting twelve spoonfuls into a huge brown teapot requiring both hands to lift.

His wardrobe was famously casual: 'an awful pair of thick corduroy trousers', a pair of thick, grey flannel trousers, a 'rather nice' black corduroy jacket, a shaggy, battered, green-grey Harris tweed jacket, and a 'best suit' of dark-grey-to-black herringbone tweed of old-fashioned cut.

Younger sister, Avril, joined him at Barnhill, Jura, as housekeeper. Like her brother, she was of tough character, and eventually drove away Richard Orwell's nanny, because the house was too small for both women. Orwell also nearly died during an unfortunate boating expedition in that time.

Biographers' opinions

Of Orwell, Bernard Crick writes:

... he was both a brave man and one who drove himself hard, for the sake, first, of 'writing' and then more and more for an integrated sense of what he had to write. Orwell was unusually reticent to his friends about his background and his life, his openness was all in print for literary or moral effect; he tried to keep his small circle of good friends well apart – people are still surprised to learn who else at the time he knew; he did not confide in people easily, not talk about his emotions – even to women with whom he was close; he was not fully integrate as a person, not quite comfortable within his own skin, until late in his life – and he was many-faceted, not a simple man at all.

Shelden noted Orwell’s obsessive belief in his failure, and the deep inadequacy haunting him through his career:

Playing the loser was a form of revenge against the winners, a way of repudiating the corrupt nature of conventional success – the scheming, the greed, the sacrifice of principles. Yet, it was also a form of self-rebuke, a way of keeping one’s own pride and ambition in check.

According to T.R. Fyvel:

His crucial experience ... was his struggle to turn himself into a writer, one which led through long periods of poverty, failure and humiliation, and about which he has written almost nothing directly. The sweat and agony was less in the slum-life than in the effort to turn the experience into literature.

Bibliography

Novels

- Burmese Days (1934) —

- A Clergyman's Daughter (1935) —

- Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936) —

- Coming Up for Air (1939) —

- Animal Farm (1945) —

- Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) —

Books based on personal experiences

While the substance of many of Orwell's novels, particularly Burmese Days, is drawn from his personal experiences, the following are works presented as narrative documentaries, rather than being fictionalized.

- Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) -

- The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) —

- Homage to Catalonia (1938) —

Essays

Main article: Essays of George OrwellPenguin Books George Orwell: Essays, with an Introduction by Bernard Crick

- "The Spike" (1931) —

- "A Nice Cup of Tea" (1946) —

- "A Hanging" (1931) —

- "Shooting an Elephant" (1936) —

- "Charles Dickens" (1939) —

- "Boys' Weeklies" (1940) —

- "Inside the Whale" (1940) —

- "The Lion and The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius" (1941) —

- "Wells, Hitler and the World State" (1941) —

- "The Art of Donald McGill" (1941) —

- "Looking Back on the Spanish War" (1943) —

- "W. B. Yeats" (1943) —

- "Benefit of Clergy: Some notes on Salvador Dali" (1944) —

- "Arthur Koestler" (1944) —

- "Notes on Nationalism" (1945) —

- "How the Poor Die" (1946) —

- "Politics vs. Literature: An Examination of Gulliver's Travels" (1946) —

- "Politics and the English Language" (1946) —

- "Second Thoughts on James Burnham" (1946) —

- "Decline of the English Murder" (1946) —

- "Some Thoughts on the Common Toad" (1946) —

- "A Good Word for the Vicar of Bray" (1946) —

- "In Defence of P. G. Wodehouse" (1946) —

- "Why I Write" (1946) —

- "The Prevention of Literature" (1946) —

- "Such, Such Were the Joys" (1946) —

- "Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool" (1947) —

- "Reflections on Gandhi" (1949) —

- "Bookshop Memories" (1936) —

- "The Moon Under Water" (1946) —

- "Rudyard Kipling" (1942) —

- "Raffles and Miss Blandish" (1944) —

Poems

- "Romance"

- "A Little Poem"

- "Awake! Young Men of England"

- "Kitchener"

- "Our Minds are Married, But we are Too Young"

- "The Pagan"

- "The Lesser Evil"

- "Poem from Burma"

Source: George Orwell's Poems

About George Orwell

- Anderson, Paul (ed). Orwell in Tribune: 'As I Please' and Other Writings. Methuen/Politico's 2006. ISBN 1-842-75155-7

- Bowker, Gordon. George Orwell. Little Brown. 2003. ISBN 0-316-86115-4

- Buddicom, Jacintha. Eric & Us. Finlay Publisher. 2006. ISBN 0-9553708-0-9

- Caute, David. Dr. Orwell and Mr. Blair, Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-81438-9

- Crick, Bernard. George Orwell: A Life. Penguin. 1982. ISBN 0-14-005856-7

- Flynn, Nigel. George Orwell. The Rourke Corporation, Inc. 1990. ISBN 0-86593-018-X

- Hitchens, Christopher. Why Orwell Matters. Basic Books. 2003. ISBN 0-465-03049-1

- Hollis, Christopher. A Study of George Orwell: The Man and His Works. Chicago: Henry Regnery Co. 1956. ASIN B000ANO242.

- Larkin, Emma. Finding George Orwell in Burma. Penguin. 2005. ISBN 1-59420-052-1

- Lee, Robert A, Orwell's Fiction. University of Notre Dame Press, 1969. LC 74-75151

- Leif, Ruth Ann, Homage to Oceania. The Prophetic Vision of George Orwell. Ohio State U.P.

- Meyers, Jeffery. Orwell: Wintry Conscience of a Generation. W.W.Norton. 2000. ISBN 0-393-32263-7

- Newsinger, John. Orwell's Politics. Macmillan. 1999. ISBN 0-333-68287-4

- Shelden, Michael. Orwell: The Authorized Biography. HarperCollins. 1991. ISBN 0-06-016709-2

- Smith, D. & Mosher, M. Orwell for Beginners. 1984. London: Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative.

- Taylor, D. J. Orwell: The Life. Henry Holt and Company. 2003. ISBN 0-8050-7473-2

- West, W. J. The Larger Evils. Edinburgh: Canongate Press. 1992. ISBN 0-86241-382-6 (Nineteen Eighty-Four – The truth behind the satire.)

- West, W. J. (ed.) George Orwell: The Lost Writings. New York: Arbor House. 1984. ISBN 0-87795-745-2

- Williams, Raymond, Orwell, Fontana/Collins, 1971

- Woodcock, George. The Crystal Spirit. Little Brown. 1966. ISBN 1-55164-268-9

See also

References

- "George Orwell". The Orwell Reader. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- "George Orwell". History Guide. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- Michael O'Connor (2003). Review of Gordon Bowker's "Inside George Orwell".

- Bernard Crick George Orwell: A Life Secker & Warburg 1980. Several earlier biographers suggested that Mrs Blair moved to England in 1907 based on information given by Avril Blair reminiscing of a time before she was born. The evidence to the contrary is the diary of Ida Blair for 1905 and a photograph of Eric aged 3 in an English suburban garden. The earlier date also coincides with a difficult posting for Blair senior, and Marjorie (6) needing an English education.

- ^ Jacintha Buddicom Eric and Us Frewin 1974. Cite error: The named reference "autogenerated1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Henley and South Oxfordshire Standard 2 October 1914

- Henley and South Oxfordshire Standard 21 July 1916

- Bernard Crick George Orwell: A Life, quote from interview with Gow

- Ruth Pitter BBC Overseas Service broadcast, 3 January 1956

- D J Taylor Orwell: The Life Chatto & Windus 2003

- R. S. Peters A Boys View of George Orwell Psychology and Ethical Development Allen & Unwin 1974

- Stella Judt I once met George Orwell in I once Met 1996

- Bernard Crick Interview with Geoffrey Stevens in George Orwell: A Life

- Avril Dunn My Brother George Orwell Twentieth Century 1961

- Correspondence in Collected Essays Journalism and Letters Secker & Warburg 1968

- Orwell, Sonia and Angus, Ian (eds.)Orwell: An Age Like This, letters 31 and 33 (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World)

- The conventional view that this was a specific commission with a £500 advance is based on a recollection by George Gorer. However Taylor argues that Orwell's subsequent circumstances showed no indication of such largesse, Gollancz was not a person to part with such a sum on speculation, and Gollancz took little proprietorial interest in progress - D. J. Taylor Orwell: The Life Chatto & Windus 2003

- John McNair - Interview with Ian Angus UCL 1964

- van Ree, Erik (2002). The Political Thought of Joseph Stalin. London: Routledge. pp. p286. ISBN 0700717498.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - (1984) Crick, Bernard. "Introduction to George Orwell", Nineteen Eighty-Three (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

- Barnhill is located at 56° 06' 39" N 5° 41' 30" W (British national grid reference system NR705970)

- Timothy Garton Ash: "Orwell's List" in "The New York Review of Books", Number 14, 25 September 2003

- "George Orwell's Widow; Edited Husband's Works". Associated Press. December 12, 1980, Friday.

London, Friday, December 12 (Associated Press) Sonia Orwell, widow of the writer George Orwell, died here yesterday, The Times of London reported today. The newspaper gave no details.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "George Orwell, Author, 46, Dead. British Writer, Acclaimed for His '1984' and 'Animal Farm,' is Victim of Tuberculosis. Two Novels Popular Here Distaste for Imperialism". New York Times. January 22, 1950, Sunday.

London, January 21, 1950. George Orwell, noted British novelist, died of tuberculosis in a hospital here today at the age of 46.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Andrew Anthony, 'Review: George Orwell's Books', The Observer, 11 May 2003, Observer Review Pages, Pg. 1.

- Irving Howe considered Orwell "the best English essayist since Hazlitt" George Orwell: “As the bones know” by Irving Howe, Harper's Magazine January 1969; reprinted in Newsweek as "was the finest journalist of his day and the foremost architect of the English essay since Hazlitt.".

- Letter to Gleb Struve, 17 February 1944, Orwell: Essays, Journalism and Letters Vol 3, ed Sonia Brownell and Ian Angus

- Malcolm Muggeridge: Introduction

- http://www.hoover.org/publications/uk/2939606.html

- George Orwell: Rudyard Kipling

- George Woodcock Introduction to Stephen Wadhams Remembering Orwell Penguin 1984

- George Orwell, "Politics and the English Language," 1946

- Cyril Connolly Enemies of Promise 1938 ISBN0-233-97936-0

- Cyril Connolly Enemies of Promise 1938 ISBN0-233-97936-0

- John Wilkes in Stephen Wadhams Remembering Orwell" Penguin Books 1984.

- Roger Mynors in Stephen Wadhams Remembering Orwell" Penguin Books 1984.

- Christopher Hollis A Study of George Orwell

- Interview with Bernard Crick in George Orwell: A life"

- Audrey Coppard and Bernard Crick Orwell Remembered 1984

- Collected Essays Journalism and Letters Secker & Warburg 1968

- Bernard Crick George Orwell: A Life Secker & Warburg 1980

- Roger Mynors in Stephen Wadhams Remembering Orwell Penguin 1984

- R. S. Peters A Boy's View of George Orwell in Psychology and Ethical Development Allen & Unwin 1974

- Geoffrey Stevens in Stephen Wadhams Remembering Orwell Penguin 1984

- Stephen Wadhams Remembering Orwell Penguin Books 1984

- Stephen Wadhams Remembering Orwell

- Correspondence in Collected Essays Journalism and Letters Secker & Warburg 1968

- George Orwell: A Life, Bernard Crick, p.480

- "Orwell and the secret state: close encounters of a strange kind?", by Richard Keeble, Media Lens, Monday, October 10, 2005.

- Ruth Pitter, BBC Overseas Service broadcast, 3 January 1956

- Orwell, George (1998), Facing Unpleasant Facts 1937-1939, The Complete Works of George Orwell, London: Secker & Warburg, p. 22-23, ISBN 0436205386

- George Orwell: A Life, Bernard Crick, p.502

- George Orwell: A Life, Bernard Crick, p.504

- Michael Shelden Orwell: The Authorised Biography Heinnemann 1991

- T.R. Fyvel, A Case for George Orwell?, Twentieth Century, September 1956, pp.257-8

- Charles' George Orwell Links, Essays & Journalism Section.

External links

- George Orwell at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- George Orwell at IMDb

- The George Orwell Web Source - Essays, novels, reviews and exclusive images of Orwell.

- "Is Bad Writing Necessary?" - An essay comparing Theodor Adorno and George Orwell's lives and writing styles. In Lingua Franca, (December/January 2000).

- "Orwell's Burma", an essay in Time

- Orwell's Century, Think Tank Transcript

- Thesis statements and important quotes from the novel

- George Orwell at IMDb from Internet Movie Database

- UK National Archives Reveal George Orwell watched by MI5

- Lesson plans for Orwell's works at Web English Teacher

- George Orwell at the Internet Book List

- 'George Orwell: International Socialist?' by Peter Sedgwick

- 'George Orwell: A literary Trotskyist?'

- George Orwell in the World of Science Fiction

- 'Collected Essays of George Orwell'

- Works by George Orwell (public domain in Canada)

- Template:Worldcat id

- George Orwell in Lleida A photograph of a column of the POUM, including a man who appears to be Orwell, about 1936/37.

- The Orwell Prize

- The Orwell Diaries: a daily extract from Orwell's diary from the same date seventy years before

Template:Persondata

{{subst:#if:Orwell, George|}}

[[Category:{{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1903}}

|| UNKNOWN | MISSING = Year of birth missing {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1950}}||LIVING=(living people)}}

| #default = 1903 births

}}]] {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1950}}

|| LIVING = | MISSING = | UNKNOWN = | #default =

}}

Categories:- Living people

- 1950 deaths

- George Orwell

- Administrators in British Burma

- British colonial police officers

- British people of the Spanish Civil War

- Deaths from tuberculosis

- English Anglicans

- English essayists

- English memoirists

- English novelists

- English poets

- English political writers

- English socialists

- Language creators

- Old Etonians

- Old Wellingtonians

- Anti-fascists