| Revision as of 14:34, 4 November 2008 view sourceVoABot II (talk | contribs)274,019 editsm BOT - Reverted edits by 163.153.35.250 {possible vandalism} (mistake?) to last version by "Igoldste".← Previous edit |

Revision as of 14:38, 4 November 2008 view source 163.153.35.250 (talk) ←Replaced content with '{{Infobox Country |name = British Empire |image_flag = Flag of the United Kingdom.svg |image_map = British Empire red.png |ma...'Next edit → |

| Line 8: |

Line 8: |

|

{{For|a comprehensive list of the territories that formed the British Empire|Evolution of the British Empire}} |

|

{{For|a comprehensive list of the territories that formed the British Empire|Evolution of the British Empire}} |

|

|

|

|

|

|

'''SUP DUDE?''' |

|

The '''British Empire''' was the set of ], ], ]s and ] ruled or administered by the ], that had originated with the overseas colonies and ]s established by ] in the 17th century. It was the ] in history and, for over a century, was the foremost ]. By 1921, the British Empire held sway over a population of about 458 million people, approximately one-quarter of the world's population.<ref>], p.98,242</ref> and covered more than 13 million square miles, almost a quarter of Earth's total land area.<ref>], p.15</ref> As a result, its political, linguistic and cultural legacy is widespread. At the peak of its power, it was often said that "]" because its span across the globe ensured that the sun was always shining on at least one of its numerous territories. |

|

|

|

|

|

During the ] in the 15th and 16th centuries, ] and ] pioneered European exploration of the globe and in the process established overseas empires that stretched from the ] to the ]. Envious of the great wealth these empires bestowed on Spain and Portugal, the Northern European nations of England, ] and the ] began in the late 16th century to challenge Spanish and Portuguese hegemony. The English, French and Dutch established colonies and trade networks of their own in the Americas and Asia, in conflict with one another and with Spain and Portugal, which had begun a slow decline as imperial powers during the 17th century. A series of wars with the Netherlands and France left England (following the ], ]) the dominant colonial power in North America and India. The loss of the American ] after the ] was a temporary blow to Britain, depriving it of its most powerful and populous colony. However, British attention soon turned towards ] and Asia, where a new empire was established. Following the ], Britain enjoyed a century of effectively unchallenged strength, thanks to its rapidly expanding economy, the strength of the ], and the lack of serious colonial rivals. During this time, Britain consolidated and expanded its imperial holdings in Africa, Asia, India and the Pacific, and granted increasing degrees of autonomy to its ] settler colonies, which were reclassified as dominions. |

|

|

|

|

|

The growth of ] and the ] had eroded Britain's economic lead by the end of the 19th century. Subsequent military and economic tensions between Britain and Germany were major causes of ] which ended the period of relative peace in 1914. The conflict, for which Britain leaned heavily upon its empire, placed enormous financial strain on Britain, and although the empire achieved its largest territorial extent immediately after the war, it was no longer a peerless industrial or military power. Despite Britain and its empire emerging as victors, ] saw much of the British Empire in Asia occupied by ] which damaged British prestige and accelerated the decline of the empire. Within two years of the end of the war, Britain granted independence to its most populous and valuable colony, India. |

|

|

|

|

|

During the remainder of the 20th century, most of the territories of the empire became independent as part of a larger global ] movement by the European powers, ending with the return of ] to ] in 1997. Many former British colonies went on to join the ], a free association of independent states. Some have retained the ], currently ], as their ] to become independent ]s. Fourteen territories remain under British sovereignty, the ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

==Origins (1497–1583)== |

|

|

]'s ship used for his second voyage to the ]. Cabot and his ship were never seen again.]] |

|

|

The foundations of the British Empire were laid at a time before the creation of ], when ] and ] were separate kingdoms. In 1496 King ], following the successes of ] and ] in overseas exploration, commissioned ] to lead a voyage to discover a route to ] via the ]. Cabot sailed in 1497, and though he successfully made landfall on the coast of ] (mistakenly believing, like ] five years earlier, that he had reached Asia<ref>], p.45</ref>), there was no attempt to found a ]. Cabot led another voyage to the Americas the following year but nothing was heard from his ships again.<ref>], p.4</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

No further attempts to establish English colonies overseas were made until well into the reign of ], during the last decades of the 16th century.<ref>], p.35</ref> The ] had made enemies of England and ] ].<ref>], p.3</ref> In the ], the English Crown sanctioned ]s such as ] and ] to engage in piratical attacks on Spanish ports in the Americas and shipping that was returning across the ], laden with treasure from the ].<ref>], p.7</ref> At the same time, influential writers such as ] and ] (who was the first to use the term "British Empire"<ref>], p.62</ref>) were beginning to press for the establishment of England's own empire, to rival those of Spain and Portugal. By this time, Spain was firmly entrenched in the Americas, ] had established a string of trading posts and forts from the coasts of ] and ] to ], and ] had begun to settle the ], later to become ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

===Plantations of Ireland=== |

|

|

Though a relative latecomer to overseas colonisation in comparison to Spain and Portugal, England had been engaged in a form of 'domestic colonisation'<ref>], p.7</ref> in ]. The 16th century ], run by English colonists, were a precursor to the overseas Empire,<ref>], p.123</ref> and several people involved in these projects also had a hand in the early colonisation of North America, particularly a group known as the "West Country men", which included Sir ], Sir ], Sir ], Sir ], Sir ] and Sir ].<ref>], p.119</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

=="First British Empire" (1583–1783)== |

|

|

] |

|

|

|

|

|

In 1578 Sir ] was granted a ] by ] for discovery and overseas exploration, and set sail for the ] with the intention of first engaging in piracy and on the return voyage, establishing a colony in ]. The expedition failed at the outset because of bad weather. In 1583 Gilbert embarked on a second attempt, on this occasion to the island of ] where he formally claimed for England the harbour of St. John's, though no settlers were left behind to colonise it. Gilbert did not survive the return journey to England, and was succeeded by his half-brother, ], who was granted his own patent by Elizabeth in 1584, in the same year founding the colony of ] on the coast of present-day ]. Lack of supplies caused the colony to fail.<ref>], p.63-4</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

In 1603, King ] ascended to the English throne and in 1604 negotiated the ], ending hostilities with ]. Now at peace with its main rival, English attention shifted from preying on other nations' colonial infrastructure to the business of establishing its own overseas colonies.<ref>], p.70</ref> Although its beginnings were hit-and-miss, the British Empire began to take shape during the early 17th century, with the English settlement of ] and the smaller islands of the ], and the establishment of a private company, the ], to trade with ]. This period, until the loss of the ] after the ] towards the end of the 18th century, has subsequently been referred to as the "First British Empire".<ref>], p.34</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

]; 2: ]; 3: The ]; 4: ]; 5: ]; 6: ]; 7: ]; 8: ]]] |

|

|

===The Americas, Africa and the Slave Trade=== |

|

|

|

|

|

The ] initially provided England's most important and lucrative colonies,<ref>], p.17</ref> but not before several attempts at colonisation failed. An attempt to establish a colony in ] in 1604 lasted only two years, and failed in its main objective to find ] deposits.<ref>], p.71</ref> Colonies in ] (1605) and ] (1609) also rapidly folded, but settlements were successfully established in ] (1624), ] (1627) and ] (1628).<ref>], p.221</ref> The colonies soon adopted the system of ]s successfully used by the Portuguese in ], which depended on ], and—at first—Dutch ships, to sell the ] and buy the sugar. To ensure that the increasingly healthy profits of this trade remained in English hands, Parliament decreed in 1651 that only English ships would be able to ply their trade in English colonies. This led to hostilities with the ]—a series of ]—which would eventually strengthen England's position in the Americas at the expense of the Dutch. In 1655 England annexed the island of ] from the Spanish, and in 1666 succeeded in colonising the ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

England's first permanent overseas settlement was founded in 1607 in ], led by Captain ] and managed by the ], an offshoot of which established a colony on ], which had been discovered in 1609. The Company's charter was revoked in 1624 and direct control was assumed by the crown, thereby founding the ]. The ] was created in 1610 with the aim of creating a permanent settlement on Newfoundland, but was largely unsuccessful. In 1620, ] was founded as a haven for ] religious separatists, later known as the ]. Fleeing from religious persecution would become the motive of many English would-be colonists to risk the arduous ] voyage: ] was founded as a haven for ] (1634), ] (1636) as a colony tolerant of all religions and Connecticut (1639) for ]s. The ] was founded in 1663. In 1664, England gained control of the Dutch colony of ] (renamed ]) via negotiations following the ], in exchange for ]. In 1681, the colony of ] was founded by ]. The American colonies, which provided ], ], and ] in the south and naval ]<!-- This is not a misspelling. Follow the link to find out the difference between material and materiel --> were less financially successful than those of the Caribbean, but had large areas of good agricultural land and attracted far larger numbers of English emigrants who preferred their temperate climates.<ref>], p.72-73</ref> <!-- Insert some discussion of interaction with Native Indians here --> |

|

|

|

|

|

In 1670, ] granted a charter to the ], granting it a monopoly on the ] in what was then known as ], a vast stretch of territory that would later make up a large proportion of ]. Forts and trading posts established by the Company were frequently the subject of attacks by the French, who had established their own fur trading colony next door in ].<ref>], p.25</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

], ], ], ], and ]. The British commissioners refused to pose, so the painting was never finished.]] |

|

|

|

|

|

Two years later, the ] was inaugurated, receiving from King Charles a monopoly of the trade to supply slaves to the British colonies of the Caribbean.<ref>], p.37</ref> |

|

|

From the outset, ] was the basis of the British Empire in the West Indies. Until the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, Britain was responsible for the transportation of 3.5 million African slaves to the Americas, a third of all ].<ref>], p.62</ref> To facilitate this trade, forts were established on the coast of ], such as ], ] and ]. In the British ], the percentage of the population comprising blacks rose from 25% in 1650 to around 80% in 1780, and in the Thirteen Colonies from 10% to 40% over the same period (the majority in the south).<ref>], p.228</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

For the slave traders, the trade was extremely profitable, and became a major economic mainstay for such western British cities as ] and ], which formed the third corner of the so-called ] with Africa and the Americas. However, for the transportees, harsh and unhygienic conditions on the slaving ships and poor diets meant that the average mortality rate during the ] was one in seven. <!-- Needs some brief info here on conditions on plantations --> Recent historians have concluded, "Slavery did not create a major share of the capital that financed the European industrial revolution."<ref></ref> Indeed, profits from the slave trade amounted to less than 1% of total domestic investment in Britain.<ref>], p.440-64</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

In 1695 the Scottish parliament granted a charter to the ], which proceeded in 1698 to establish a settlement on the ], with a view to building a ] there. Besieged by neighbouring Spanish colonists of ], and afflicted by ], the colony was abandoned two years later. The ] was a financial disaster for Scotland - a quarter of Scottish capital was lost in the enterprise<ref>], p.531</ref> - and ended Scottish hopes of establishing its own overseas empire. The episode also had major political consequences, persuading both England and Scotland of the merits of a union of countries, rather than just crowns.<ref>], p.509</ref> This was achieved in 1707 with the ], establishing the ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

===Asia=== |

|

|

At the end of the 16th century, ] and ] began to challenge ]'s monopoly of trade with ], forming private ] companies to finance the voyages—the ] (later British) and ] East India Companies, chartered in 1600 and 1602 respectively. The primary aim of these companies was to tap into the lucrative ], and they focused their efforts on the source, the ] ], and an important hub in the trade network, ]. The close proximity of ] and ] across the ] and intense rivalry between ] and the ] inevitably led to conflict between the two companies, with the Dutch gaining the upper hand in the ] (previously a Portuguese stronghold) after the withdrawal of the English in 1622, and the English enjoying more success in India, at ], after the establishment of a factory in 1613. Though England would ultimately eclipse the Netherlands as a colonial power, in the short term the Netherlands's more advanced financial system<ref>],p.19</ref> and the three ] of the 17th century left it with a stronger position in Asia. Hostilities ceased after the ] of 1688 when the Dutch ] ascended the English throne, bringing peace between the Netherlands and England. A deal between the two nations left the spice trade of the Indonesian archipelago to the Netherlands and the textiles industry of India to England, but textiles soon overtook spices in terms of profitability, and by 1720, in terms of sales, the English company had overtaken the Dutch.<ref>],p.19</ref> The English East India Company shifted its focus from Surat—a hub of the spice trade network—to ] (later to become ]), ] (ceded by the Portuguese to ] in 1661 as dowry for ]) and ] (which would merge with two other villages to form ]). |

|

|

|

|

|

===Global struggles with France=== |

|

|

Peace between England and the Netherlands in 1688 meant that the two countries entered the ] as allies, but the conflict—waged in ] and overseas between France, Spain and the Anglo-Dutch alliance—left the English a stronger colonial power than the Dutch, who were forced to devote a larger proportion of their military budget on the costly land war in Europe.<ref>], p.441</ref> The 18th century would see England (after 1707, Britain) rise to be the world's dominant colonial power, and France becoming its main rival on the imperial stage.<ref>], p.90</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

The death of ] in 1700 and his bequeathal of Spain and its colonial empire to ], a grandson of the King of France, raised the prospect of the unification of France, Spain and their respective colonies, an unacceptable state of affairs for Britain and the other powers of Europe. In 1701, Britain, Portugal and the Netherlands sided with the ] against ] and ] in the ]. The conflict, which France and Spain were to lose, lasted until 1714. At the concluding peace ], Philip renounced his and his descendants' right to the French throne. Spain lost its empire in Europe, and though it kept its empire in the Americas and the ], it was irreversibly weakened as a power. The British Empire was territorially enlarged: from France, Britain gained ] and ], and from Spain, ] and ]. ], which is still a ] to this day, became a critical naval base and allowed Britain to control the Atlantic entry and exit point to the ]. Minorca was returned to Spain at the ] in 1802, after changing hands twice. Spain also ceded the rights to the lucrative '']'' (permission to sell slaves in Spanish America) to Britain. |

|

|

|

|

|

The ], which began in 1756, was the first war waged on a global scale, fought in Europe, India, North America, the Caribbean, the Philippines and coastal Africa. The signing of the ] had important consequences for Britain and its empire. In North America, France's future as a colonial power there was effectively ended with the recognition of British claims to ]<ref>], p.25</ref>, the ceding of ] to Britain (leaving a sizeable ] under British control) and ] to Spain. Spain ceded ] to Britain. In India, the ] had left France still in control of its ] but with military restrictions and an obligation to support British client states, effectively leaving the future of India to Britain. The British victory over France in the Seven Years' War therefore left Britain as the world's dominant colonial power.<ref>], p.91</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

]'s victory at the ] established the Company as a military as well as a commercial power]] |

|

|

|

|

|

==Rise of the "Second British Empire" (1783–1815)== |

|

|

===Company rule in India=== |

|

|

{{main|Company rule in India}} |

|

|

|

|

|

During its first century of operation, the focus of the ] had been trade, not the building of an empire in India. Indeed, the Company was no match in the region for the powerful ],<ref>], p.93</ref> which had granted the Company trading rights in 1617. Company interests turned from trade to territory during the 18th century as the Mughal Empire declined in power and the British East India Company struggled with its French counterpart, the '']'', during the ] in southeastern India in the 1740s and 1750s. |

|

|

|

|

|

The ], which saw the British, led by ], defeat the French and their Indian allies, left the Company in control of ] and a major military and political power in India. In the following decades it gradually increased the size of the territories under its control, either ruling directly or indirectly via local puppet rulers under the threat of force of the ], 80% of which was composed of native Indian ]. The Company's conquest of ] was complete by 1857. |

|

|

|

|

|

], 1797). The loss of the American colonies marked the end of the "first British Empire"]] |

|

|

===Loss of the Thirteen Colonies in America=== |

|

|

{{main|American Revolution}} |

|

|

|

|

|

During the 1760s and 1770s, relations between the ] and Britain became increasingly strained, primarily because of resentment of the British Parliament's attempts to govern and tax American colonists without their consent,<ref>],p.73</ref> summarised at the time by the slogan "]". Disagreement over the American colonists' ] turned to violence and, in 1775, the ] began. The following year, the colonists ] and, with assistance from France, would go on to win the war in 1783. |

|

|

|

|

|

The loss of such a large portion of ], at the time Britain's most populous overseas possession, is seen by historians as the event defining the transition between the "first" and "second" empires,<ref>], p.92</ref> in which Britain shifted its attention away from the Americas to Asia, the Pacific and later Africa. ]'s '']'', published in 1776, had argued that colonies were redundant, and that ] should replace the old ] policies that had characterised the first period of colonial expansion, dating back to the protectionism of Spain and Portugal. The growth of trade between the newly independent United States and Britain after 1783<ref>], p.119</ref> confirmed Smith's view that political control was not necessary for economic success. |

|

|

|

|

|

Events in America influenced British policy in ], which had seen a large influx of loyalists during the Revolutionary War. The ] created the provinces of ] (mainly English-speaking) and ] (mainly French-speaking) to defuse tensions between the two communities, and implemented governmental systems similar to those employed in Britain, with the intention of asserting imperial authority and not allowing the sort of popular control of government that was perceived to have led to the American Revolution.<ref>], p.28</ref> The future of ] was briefly threatened during the ] resulting in large part from British attempts to forcibly control Atlantic trade during the ], and in which the United States unsuccessfully took the opportunity to extend its border northwards. This remains the only formal declaration of war between Britain and the United States. |

|

|

|

|

|

] in the Pacific Ocean led to the founding of several British colonies, including Australia and New Zealand.]] |

|

|

===The Pacific=== |

|

|

Since 1718, ] to the American colonies had been a penalty for various criminal offences in Britain, with approximately one thousand convicts transported per year across the Atlantic.<ref>], p.20</ref> Forced to find an alternative location after the loss of the Thirteen Colonies in 1783, the British government turned to the newly discovered land of ], later shown to be a single land mass with ], discovered in 1606 by the ] but never colonized, and again later altogether renamed ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

In 1770 ] had discovered the eastern coast of Australia whilst on a scientific ] to the ] and named it ]. In 1778 ], Cook's ] on the voyage, presented evidence to the government on the suitability of ] for the establishment of a penal settlement, and in 1787 the first shipment of ] set sail, arriving in 1788. ] proved New Holland and ] to be a single land mass by completing a circumnavigation of it in 1803. In 1826, Australia was formally claimed for the United Kingdom with the establishment of a military base, soon followed by a colony in 1829. The colonies later became ] and became profitable exporters of ] and ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

During his voyage, Cook also visited ], first discovered by Dutch sailors in 1642, and claimed the North and South islands for the British crown in 1769 and 1770 respectively. Initially, interaction between the native ] population and Europeans was limited to the trading of goods, but increased European settlement by missionaries and traders during the early 1800s led Britain to seek formal control and in 1840, the ] was signed with the Maori. This treaty is considered by many to be New Zealand's founding document, but differing interpretations and expectations between the two sides have meant that it continues to be a source of dispute to this day. |

|

|

|

|

|

] marked the end of the ] and the beginning of the '']'']] |

|

|

===War with Napoleonic France=== |

|

|

Britain was challenged again by France under ], in a struggle that, unlike previous wars, represented a contest of ideologies between the two nations.<ref>], p.152</ref> It was not only Britain's position on the world stage that was threatened: Napoleon threatened to invade Britain itself, just as his armies had overrun many countries of continental Europe. |

|

|

The ] were therefore ones in which Britain invested large amounts of capital and resources to win. French ports were blockaded by the ], which won a decisive victory over the French fleet at ] in 1805. Overseas colonies were attacked and occupied, including those of the Netherlands, which was annexed by Napoleon in 1810. France was finally defeated by a coalition of European armies in 1815. Britain and its empire were again the beneficiaries of peace treaties: France ceded the ] and ] (which it had occupied in 1797 and 1798 respectively), ] and ]; Spain ceded ] and ]; the Netherlands ] and the ]. Britain returned ] and ] to France, and ] and ] to the Netherlands. |

|

|

|

|

|

===Abolition of slavery=== |

|

|

Under increasing pressure from the ] movement, Britain outlawed the ] (1807) and soon began enforcing this principle on other nations. In 1808, ] was designated an official British colony for freed slaves.<ref>], p.14</ref> By the mid-19th century Britain had largely eradicated the world slave trade. The ] passed in 1833 made not just the slave trade but slavery itself illegal, emancipating all slaves in the British Empire on 1 August 1834.<ref>], p.204</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

==The imperial century (1815–1914)== |

|

|

] |

|

|

Between 1815 and 1914, a period referred to as Britain's "imperial century" by some historians,<ref>], p.1</ref><ref>], p.71</ref> around 10 million square miles of territory and roughly 400 million people were added to the British Empire.<ref>], p.3</ref> Victory over Napoleon left Britain without any serious international rival, other than Russia in central Asia<ref>], p.401</ref> and, unchallenged at sea, Britain adopted the role of global policeman, a state of affairs later known as the '']''.<ref>], p.332</ref> Alongside the formal control it exerted over its own colonies, Britain's dominant position in world trade meant that it effectively controlled the economies of many nominally independent countries, such as in ], ] and ], which has been characterised by some historians as an "informal empire" <ref>], p.8</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

The ] and the ], new technologies invented in the second half of the 19th century, underpinned British imperial strength, allowing it to control and defend the sprawling empire. By 1902, the British Empire was linked together by a network of telegraph cables, the so-called ].<ref>], p.88-91</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

===Asia=== |

|

|

|

|

|

British policy in Asia during the 19th century centered around protecting and expanding India, which was viewed as its most important colony and the key to the rest of Asia.<ref>],p.478</ref> The East India Company drove the expansion of the British Empire in Asia. The Company's Army had first joined forces with the Royal Navy during the Seven Years' War, and the two continued to cooperate in arenas outside of India: the eviction of Napoleon from ] (1799), the capture of ] from the Netherlands (1811), the acquisition of ] (1819) and ] (1824) and the defeat of ] (1826).<ref>], p.?</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

From its base in India, the Company had also been engaged in an increasingly profitable ] export trade to China since the 1730s. This trade, illegal since it was outlawed by the ] in 1729, helped reverse the trade imbalances resulting from the British imports of ], which saw large outflows of silver from Britain to China. In 1839, the seizure by the Chinese authorities at ] of 20,000 chests of opium led Britain to attack China in the ], and the seizure by Britain of the island of ] (then a minor outpost) as a base.<ref>],p.293</ref> The ] was one of the first major conflicts during ], the 19th century competition for power and influence in ] between Great Britain and ]. |

|

|

] |

|

|

The end of the Company was precipitated by a ] of ]s against their British commanders over the rumoured introduction of rifle cartridges lubricated with animal fat. Use of the cartridges, which required biting open before use, would have been in violation of the religious beliefs of Hindus and Muslims (had the fat been that of cows or pigs, respectively). However, the ] had causes that went beyond the introduction of bullets: at stake was Indian culture and religion, in the face of the steady encroachment of that by the British. The rebellion was suppressed by the British, but not before heavy loss of life on both sides. The mutiny is also an early example of the growing use of communications technology with the ] critical in halting the early spread of rebellion <ref>], p.xxiii</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

As a result of the war, the British government assumed direct control over India, ushering in the period known as the ], where an appointed ] administered India and ] crowned the Empress of India. The East India Company was dissolved the following year, in 1858. During the Raj, ], often attributed to government policies, were some of the worst ever recorded, including the ], in which 6.1 million to 10.3 million people died<ref name=mikedavis> Davis, Mike. Late Victorian Holocausts. 1. Verso, 2000. ISBN 1859847390 pg 7</ref> and the ], in which 1.25 to 10 million people died.<ref name=mikedavis> Davis, Mike. Late Victorian Holocausts. 1. Verso, 2000. ISBN 1859847390 pg 173</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

===The Cape Colony=== |

|

|

The Dutch East India Company had founded the ] on the southern tip of ] in 1652 as a way station for its ships travelling to and from its colonies in the East Indies. Britain formally acquired the colony, and its large ] (or ]) population in 1806, having occupied it in 1795 in order to prevent it falling into French hands, following the invasion of the Netherlands by France.<ref>], p.85</ref> British immigration began to rise after 1820, and pushed thousands of Boers, resentful of British rule, northwards to found their own – mostly short-lived and independent republics during the ] of the late 1830s and early 1840s. In the process the ] clashed repeatedly with the British, who had their own agenda with regard to colonial expansion in ] and with several African polities, including those of the ] and the ] nations. Eventually the Boers established two republics which had a longer lifespan: the ] or Transvaal Republic (1852-1877; 1881-1902) and the ] (1854-1902). |

|

|

|

|

|

===The Suez Canal=== |

|

|

In 1869 the Suez Canal was opened under ], linking the Mediterranean with the Indian Ocean. The Canal was at first viewed sceptically by the British<ref>Uwe A. Oster at </ref>, but once open its strategic value was recognised quickly. In 1875, the ] government of ] bought the indebted ]ian ruler ]'s 44% shareholding in the ] for £4 million. Although this did not grant outright control of the strategic waterway, it did give Britain leverage. Joint Anglo-French financial control over Egypt ended in outright British occupation in 1882.<ref>],p.230-233</ref> The French were still majority shareholders and attempted to weaken the British position,<ref>], p.274</ref> but a compromise was reached with the 1888 ]. This came into force in 1904 and made the Canal neutral territory, but de facto control was exercised by the British whose forces occupied the area until 1954. |

|

|

|

|

|

===Scramble for Africa=== |

|

|

{{main|Scramble for Africa}} |

|

|

]''- ] spanning "Cape to Cairo"]] |

|

|

|

|

|

In 1875 the two most important European holdings in Africa were French-controlled ] and the United Kingdom's ]. By 1914 only ] and the republic of ] remained outside formal European control. The transition from an "informal empire" of control through economic dominance to direct control took the form of a "scramble" for territory by the nations of Europe. |

|

|

|

|

|

As French, ] and ] activity in the lower ] region threatened to undermine orderly penetration of tropical Africa, the ] of 1884–85 sought to regulate the competition between the powers by defining "effective occupation" as the criterion for international recognition of territorial claims, a formulation which necessitated routine recourse to armed force against indigenous states and peoples.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|last=Wright|first=Donald R.|title=Berlin West Africa Conference|url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761595821/berlin_west_africa_conference.html|encyclopedia=Encarta Online Encyclopedia|date=2007}}</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

The United Kingdom's 1882 military occupation of ] (itself triggered by concern over the ]) contributed to a preoccupation over securing control of the ] valley, leading to the conquest of the neighbouring ] in 1896–98 and confrontation with a French military expedition at ] (September 1898). |

|

|

|

|

|

In 1902 the United Kingdom completed its military occupation of the Transvaal and Free State by concluding a treaty with the two ] following the ] 1899-1902. The four colonies of Natal, Transvaal, Free State and Cape Province later merged in 1910 to form the Union of South Africa. |

|

|

|

|

|

British gains in southern and ] prompted ], pioneer of British expansion from South Africa northward, to urge a "]" British controlled empire linking by rail the strategically important ] to the mineral-rich South. In 1888 Rhodes with his privately owned ] occupied and annexed territories which were called after him: ] between 1896 and 1980, when it became independent under the name ]. Together with British High Commissioner in South Africa between 1897-1905, ], Rhodes pressured the British government for further expansion into Africa. ] would hamper Rhodes’ Cape-to-Cairo-ambition until the end of ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

===Home rule in white-settler colonies=== |

|

|

The United Kingdom's empire had already begun its transformation into the modern ] with the extension of ] status to the already ] of ] (1867), ] (1901), ] (1907), ] (1907), and the newly created ] (1910). Leaders of the new states joined with British statesmen in periodic ], the first of which was held in ] in 1887. |

|

|

|

|

|

The foreign relations of the Dominions were still conducted through the ] of the ]: Canada created a Department of External Affairs in 1909, but diplomatic relations with other governments continued to be channelled through the Governors-General, Dominion ]s in London (first appointed by Canada in 1880 and by Australia in 1910) and British ]s abroad. |

|

|

|

|

|

But the Dominions did enjoy a substantial freedom in their adoption of foreign policy where this did not explicitly conflict with British interests: Canada's ] negotiated ] with the United States in 1911, but went down to defeat by the ] opposition. |

|

|

|

|

|

In defence, the Dominions' original treatment as part of a single imperial military and naval structure proved unsustainable as the United Kingdom faced new commitments in Europe and the challenge of an emerging ] after 1900. In 1909 it was decided that the Dominions should have their own navies, reversing an 1887 agreement that the then Australasian colonies should contribute to the ] in return for the permanent stationing of a squadron in the region. |

|

|

|

|

|

==World War I (1914–1918)== |

|

|

Britain's declaration of war in 1914 on Germany and its allies, ] and the ], also committed the colonies and Dominions, which provided invaluable military, financial and material support during the war. Soon after the outbreak of hostilities, Germany's overseas colonies in Africa were invaded and occupied, though German forces in ] remained undefeated during the war. In the Pacific, Australia and New Zealand occupied ] and ] respectively. The contributions of Australian and New Zealand troops during the 1915 ] against the ] had a great impact on the national consciousness at home, and marked a watershed in the transition of Australia and New Zealand from colonies to nations in their own right. The countries continue to commemorate this occasion on ]. Canadians viewed the ] in a similar light.<ref>], p.227</ref> The ]s raised their own armies, but were under the British command structure, and very much integrated into the British fighting forces. Over 2.5 million men, which included Canada sending 418,000 men overseas, Australia sent 322,000, New Zealand 124,000, and other volunteers from the ]. <ref>{{cite news|url= http://encyclopedia.farlex.com/British+Empire+(World+War+I)|title= WW1 Dominion Armies| publisher= Farlex encyclopedia|accessdate=|date}}</ref> |

|

|

In 1917, the ] was set up, with representation from each of the Dominion Prime Ministers, to coordinate imperial policy. The First World War placed enormous financial strain on Britain and its empire with resources, cash and foreign assets being diverted for the war. In 1914 Britain had £750,000,000<ref>], p.258</ref> invested in the United States; by 1918 much of this had been sold in order to pay for the war effort. |

|

|

|

|

|

==Interwar period (1918–1939)== |

|

|

] |

|

|

|

|

|

The aftermath of ] saw the last major extension of British rule, with the United Kingdom gaining control through ]s in ] and ] after the collapse of the ] in the Middle East, as well as in the former German colonies of ], South-West Africa (now ]) and ] (the last two actually under South African and Australian rule respectively). |

|

|

|

|

|

The 1920s saw a rapid transformation of Dominion status. Although the Dominions had had no formal voice in declaring war in 1914, each was included separately among the signatories of the 1919 peace ], which had been negotiated by a British-led united Empire delegation. In 1922 Dominion reluctance to support British military action against ] influenced the United Kingdom's decision to seek a compromise settlement. The League of Nations deputed former German colonies to come under the control of the United Kingdom's colonies. For example, New Zealand took over the mandate of ], Australia that of ] and South Africa that of ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

Full Dominion independence was formalised in the 1931 ]: each Dominion was henceforth to be equal in status to the United Kingdom itself, free of British legislative interference and autonomous in international relations. The Dominions section created within the Colonial Office in 1907 was upgraded in 1925 to a separate ] and given its own ] in 1930. |

|

|

|

|

|

] led the way, becoming the first Dominion to conclude an international treaty entirely independently (1923) and obtaining the appointment (1928) of a British ] in ], thereby separating the administrative and diplomatic functions of the Governor-General and ending the latter's anomalous role as the representative of the head of state and of the British Government. Canada's first permanent diplomatic mission to a foreign country opened in ], in 1927: Australia followed in 1940. |

|

|

|

|

|

], formally independent from 1922 but bound to the United Kingdom by treaty until 1936 (and under partial occupation until 1956) similarly severed all constitutional links with the United Kingdom. ], which became a British Protectorate in 1922, also gained complete independence ten years later in 1932. |

|

|

|

|

|

===The Irish Free State=== |

|

|

]]] |

|

|

|

|

|

] was to be provided under the ], but the onset of World War I delayed its implementation indefinitely. At Easter 1916 ] was staged in Dublin by a mixed group of nationalists and socialists. From 1919 the ] fought a ] to secede from the United Kingdom. This ] ended in 1921 with a stalemate and the signing of the ]. The treaty confirmed the division of Ireland into two states. Most of the island (26 counties) became independent as the ], a dominion within the ]. Meanwhile, the four counties in the north of the island with a majority Unionist community, along with two counties that had a Nationalist majority,<ref>], p.272</ref><ref>{{cite book| first =|last =Morland and Cowling |title=Political issues for the twenty-first century |publisher=Ashgate Publishing, Ltd |year=2004|pages=270}}</ref><ref>], p.480</ref> remained a part of the United Kingdom as ]. The Free State evolved into the ], which withdrew from the Commonwealth when the ] was enacted in 1949. |

|

|

|

|

|

] claimed Northern Ireland as a part of the Republic ]. The issue of whether Northern Ireland should remain in the United Kingdom or join the Republic of Ireland has divided Northern Ireland's people and was a factor in a long and bloody conflict known as ]. The ] of 1998 brought about a ceasefire between most of the major organisations on both sides. |

|

|

|

|

|

] |

|

|

==World War II (1939-1945)== |

|

|

{{main|Military history of the United Kingdom during World War II}} |

|

|

Britain's declaration of hostilities against ] in September 1939 included the Crown Colonies and India but did not automatically commit the Dominions. Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand all soon declared war on Germany, but the ] chose to remain ] throughout ].<ref>], p.313-4</ref> After the ] in 1940, Britain was left standing alone against Germany and its situation looked precarious. The British Prime Minister, ], looked to increase ties with the United States, but the American President ] was not yet ready to commit to war. The two leaders signed the ] in 1941, which included the statement that "the rights of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they live" should be respected. This wording was ambiguous as to whether it referred to European countries invaded by Germany, or the peoples colonised by European nations, and would later be interpreted differently by the British, Americans and nationalist movements.<ref>], p.316</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

The outbreak of hostilities in the Pacific later in the year had an immediate and long-lasting impact on Britain and its empire. With the resources of the United States on its side, the chances of eventual British victory greatly increased, but the Japanese invasion of its empire in south-east Asia and the manner in which it rapidly folded irreversibly altered Britain's standing as an imperial power. ] was quickly captured, and Japanese forces continued south to capture ] and, most damagingly of all, ], which had previously been hailed as an impregnable fortress and the eastern equivalent of Gibraltar. The realisation that Britain could not defend its entire empire pushed Australia and New Zealand, which now appeared threatened by Japanese forces, into closer ties with the United States, eventually resulting in the 1951 ] between the three nations, but excluding Britain itself.<ref>], p.316</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

==Decolonisation and decline (1945–1997)== |

|

|

|

|

|

Though Britain and its empire emerged victorious from ], the effects of the conflict were profound, both at home and abroad. Much of ], a continent that had dominated the world for five hundred years, was now literally in ruins, and host to the armies of the United States and the Soviet Union, to whom the balance of global power had now shifted.<ref>], p.146</ref> Britain itself was left virtually ], with insolvency only averted in 1946 after the negotiation of a $3.5 billion loan from the United States,<ref>], p.331</ref> the last instalment of which was repaid in 2006.<ref></ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

At the same time, anti-colonial movements were on the rise in the colonies of European nations. The situation was complicated further by the increasing ] rivalry of the United States and the Soviet Union, both nations opposed to the European colonialism of old, though American ] prevailed over anti-imperialism, which led the US to support the continued existence of the British Empire.<ref>], p.330</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

However, the "]" ultimately meant that the British Empire's days were numbered, and on the whole, Britain adopted a policy of peaceful disengagement from its colonies once stable, non-Communist governments were available to transfer power to, in contrast to France and Portugal,<ref>], p.148</ref> which waged costly and ultimately unsuccessful wars to keep their empires intact. Between 1945 and 1965 the number of people outside the United Kingdom itself under British rule fell from 700 million to 5 million, 3 million of whom were in ].<ref>], p.330</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

===The Dominions=== |

|

|

After the war, Australia and New Zealand joined with the United States in the ] regional security treaty in 1951 (although the US repudiated its commitments to New Zealand following a 1985 dispute over port access for nuclear vessels). The United Kingdom's pursuit (from 1961) and attainment (in 1973) of ] membership weakened the old commercial ties to the Dominions, ending their privileged access to the UK market. |

|

|

|

|

|

In January 1947, ] became the first Dominion to create its nationals as citizens in addition to their status as British subjects (which was retained until 1977). Canada became legally independent after the passing by the British Parliament of the ], effecting the ] of the national constitution. |

|

|

|

|

|

===Initial disengagement=== |

|

|

] and ], two of the leaders of the ]]] |

|

|

|

|

|

The pro-decolonisation ] government elected at the ] and led by ], moved quickly to tackle the most pressing issue facing the empire, that of Indian independence.<ref>], p.322</ref> India's two independence movements, the ], and the ], had been campaigning for independence for decades, but disagreed on how it should be implemented. Congress favoured a unified Indian state, whereas the League, fearing domination by the Hindu majority, desired a separate state for Muslim-majority regions. Increasing civil unrest and the mutiny of the ] during 1946 led Attlee to promise independence no later than 1948, but when the urgency of the situation and risk of civil war became apparent to Britain's newly appointed (and last) Viceroy, ], partitioned independence was hastily brought forward to 15 August 1947.<ref>], p.67</ref> The borders drawn by the British to broadly ] into Hindu and Muslim areas left tens of millions as minorities in the newly independent states of ] and ].<ref>], p.325</ref> Millions of Muslims subsequently crossed from India to Pakistan and Hindus in the reverse direction, and violence between the two communities cost hundreds of thousands of lives. Burma, which had been administered as part of the ], and ] gained their independence the following year in 1948. India, Pakistan and Ceylon became members of the ], though Burma chose not to join. |

|

|

|

|

|

The ], where an Arab majority lived alongside a Jewish minority, presented the British with a similar problem to that of India.<ref>], p.327</ref> The matter was complicated by large numbers of Jewish refugees seeking to be admitted to Palestine following ] oppression and genocide of the Second World War. Rather than deal with the issue, however, Britain announced in 1947 that it would withdraw in 1948 and leave the matter to the United Nations to solve,<ref>], p.328</ref> which it did by voting for the ] into a Jewish and Arab state. |

|

|

|

|

|

Following the defeat of Japan in World War II, anti-Japanese resistance movements in Malaya turned their attention towards the British, who had moved to quickly reassume control of the colony, valuing it as a source of rubber and tin. The fact that the guerillas were primarily Malayan-Chinese Communists meant that the British attempt to quell the uprising was supported by the Muslim Malay majority, on the understanding that once the insurgency had been quelled, indpendence would be granted.<ref>], p.335</ref> The ], as it was known, began in 1948 and lasted until 1960, but by 1957, Britain felt confident enough to grant independence to the ] within the Commonwealth. In 1963, the Federation was joined with ], ] and ] to form ], but in 1965 Chinese-dominated ] left the union following tensions between the Malay and Chinese populations.<ref>], p.364</ref> ], which had been a British protectorate since 1888, declined to join the union<ref>], p.396</ref> and continued to be a protectorate until it achieved independence in 1984. |

|

|

|

|

|

===Suez and its aftermath=== |

|

|

]'s decision to invade the ] ended his political career and revealed Britain's weakness as an imperial power.]] |

|

|

In 1951, the ] was returned to power in Britain, under the leadership of Winston Churchill. Churchill and the Conservatives believed that Britain's position as a world power relied on the continued existence of the empire, with the base at the ] allowing Britain to maintain its preeminent position in the Middle East in spite of the loss of India.<ref>], p.339-40</ref> However, Churchill could not ignore the new revolutionary government of Egypt that had ], and the following year it was agreed that ] would become independent by 1955. |

|

|

|

|

|

Simmering tensions between Britain and Egypt were brought to the boil in 1956 when the Egyptian leader, ], unilaterally nationalised the Suez Canal. British Prime Minister ]'s response was to collude with France to engineer an ]i attack on ] that would give Britain and France an excuse to intervene militarily and retake the canal.<ref>], p.581</ref> However, Eden infuriated his US counterpart, President ], by his lack of consultation, and Eisenhower refused to back the invasion.<ref>],p.355</ref> Another of Eisenhower's concerns was the possibility of a wider war with the ] after ] threatened to intervene on the Egyptian side. Eisenhower applied financial leverage by threatening to sell US reserves of the ] and thereby precipitate a collapse of the British currency.<ref>],p.356</ref> Though the invasion force was militarily successful in its objective of recapturing the Suez Canal",<ref>], p.583</ref> UN intervention and US pressure forced Britain into a very humiliating withdrawal of its forces. As a result, Eden resigned. |

|

|

|

|

|

The ] very publicly exposed Britain's limitations to the world and confirmed Britain's decline on the world stage, demonstrating that henceforth it could no longer act without at least the acquiescence, if not the full support, of the United States.<ref>], p.342</ref><ref>], p.105</ref><ref>], p.602</ref> The events at Suez wounded British national pride, leading one ] to describe it as "Britain's ]"<ref>], p.343</ref> and another to suggest that the country had become an "American ]".<ref>], p.585</ref> ] later described the mindset she believed had befallen the British political establishment as "Suez syndrome",<ref>]</ref> from which Britain did not recover until the successful recapture of the ] from ] in 1982. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, whilst The Suez Crisis caused British power in the Middle East to weaken, it did not collapse.<ref>], p.106</ref> Britain again soon deployed its armed forces to the region, intervening in ] (1957), ] (1958) and ] (1961), though on these occasions with American approval,<ref>], p.586</ref> as the new Prime Minister ]'s foreign policy was to remain firmly aligned with the United States.<ref>], p.?</ref> Britain maintained a presence in the Middle East for another decade, withdrawing from ] in 1967, and ] in 1971. |

|

|

|

|

|

===The wind of change=== |

|

|

] (the future ] and the South African mandate of ] (]) had achieved independence.]] |

|

|

Under Macmillan, and subsequently ], decolonization proceeded rapidly. |

|

|

|

|

|

In the Mediterranean, a guerrilla war waged by ] ended (1960) in an independent ], although the United Kingdom did retain four military bases - ], ], ] and ]. The Mediterranean islands of ] and ] ] independence from the United Kingdom in 1964. |

|

|

|

|

|

In Africa, ]'s independence (1957) after a ten-year nationalist political campaign was followed by that of ] and ] (1960), ] (1961), ] (1962), ] and ] (1963), ] (1964), ] (1965), ] (formerly Basutoland) (1966), ] (formerly Bechuanaland) (1967), and ] (1968). British withdrawal from the southern and eastern parts of Africa was complicated by the region's white settler populations, and white minority rule in ] remained a source of bitterness within the Commonwealth until the ] left the Commonwealth in 1961. |

|

|

|

|

|

Although the white-dominated ] ended in the independence of ] (formerly ]) and ] (the former ]) in 1964, ]'s white minority (a ] since 1923) declared independence with their ] rather than submit to the immediate majority rule of ]s. The support of South Africa's apartheid government, and the Portuguese rule of ] and ] helped support the Rhodesian regime until 1979, when agreement was reached on majority rule, ending the ]. Under the ], ] became interim governor in December 1979. The following February, ] won the first premiership of newly independent ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

Most of the UK's ] territories opted for eventual separate independence after the failure of the ] (1958–62): ] and ] (1962) were followed into statehood by ] (1966) and the smaller islands of the eastern Caribbean (1970s and 1980s), ] being the last in November 1981. ] achieved independence from the United Kingdom in 1966. Britain's last colony on the American mainland, ], became a self-governing colony in 1964 and was renamed ] in 1973, achieving full independence in 1981. ] and the ] opted to revert to British rule after they had already started on the path to independence. |

|

|

|

|

|

The British decolonisation of ] was peaceful and consensual. British Pacific Island territories acquired independence between 1970 (]) and 1980 (]), the latter's independence having been delayed only due to the reluctance of ], which administered the islands with Britain as a ]. ], the ] and ] chose to remain ]. The United Kingdom being willing to cut the colonial ties with its Pacific Island dependencies, there were no pro-independence struggles. |

|

|

|

|

|

] |

|

|

|

|

|

===The end of empire=== |

|

|

|

|

|

By 1980, decolonisation was largely complete. Aside from a scattering of islands and outposts, and the acquisition in 1955 of an uninhabited rock in the Atlantic Ocean, ], over concerns that the ] might use the island to spy on a British missile test<ref>{{cite web | title = 1955: Britain claims Rockall | publisher = BBC News | url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/september/21/newsid_4582000/4582327.stm}}</ref>, it appeared that the days of the British Empire were over. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, in 1982, Britain's resolve to defend its remaining overseas territories was tested when ] invaded the ], acting on a long-standing claim that dated back to the ]. Britain's ultimately successful military response to retake the islands during the ensuing ] prompted headlines in the American press that "the Empire strikes back", and was viewed by many to have contributed to reversing the downward trend in the UK's status as a ].<ref>], p.629</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

In 1997, ] became a ] of the ], per the 1984 ]. For many, including ] who was in attendance at the ], the handover of Britain's last major and by far most populous overseas territory marked "the end of Empire".<ref></ref><ref></ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

==Legacy== |

|

|

]]] |

|

|

|

|

|

The United Kingdom retains sovereignty over 14 territories outside of the British Isles,<ref>, retrieved ]</ref> collectively named the ], which remain under British rule because of lack of support for independence among the local population or because the territory is uninhabited except for transient military or scientific personnel. British sovereignty of several of the overseas territories is disputed by their geographical neighbours: ] is claimed by ], the ] and ] are claimed by ], and the ] is claimed by ] and ].<ref>. ]. CIA.</ref> The ] is subject to overlapping claims by Argentina and ], whilst many nations do not recognise any territorial claims to Antarctica.<ref>. ]. CIA.</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

Most former British colonies (and one former Portuguese colony, Mozambique<ref></ref>) are members of the ], a non-political, voluntary association of equal members, in which the United Kingdom has no privileged status. The head of the Commonwealth is currently ]. Fifteen members of the Commonwealth continue to share their head of state with the United Kingdom, as ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

Many former British colonies share or shared certain characteristics: |

|

|

|

|

|

*The ] as either the main or secondary language.<ref>], p.338</ref> |

|

|

*A ] ] of government modelled on the ]. |

|

|

*A ] based upon ].<ref>],p.307</ref> The ], one of the United Kingdom's highest courts of appeal, still serves as the highest court of appeal for several former colonies. |

|

|

*A ], ] and ] based upon British models. |

|

|

*The English and later the ] of measurement. The ], which uses the older ], ] and ] are the only former British colonies not to have officially adopted the ]. However, the imperial system is still very much used in many "officially metric" countries, such as Canada, Belize, Sierra Leone, and Ireland. |

|

|

*Educational institutions such as ]s and universities modelled on ] and ]. |

|

|

*The ]. |

|

|

*Driving on the ], with some exceptions mainly in North America and North Africa. |

|

|

*Popularity of ] and/or ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

Several ongoing conflicts and disputes around the world can trace their origins to borders inherited by countries from the British Empire: the ], the ], the ], and within Africa where political boundaries did not reflect homogeneous ethnicities or religions. The British Empire was also responsible for large migrations of peoples. Millions left the British Isles, with the founding settler populations of the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand coming mainly from Britain and Ireland. Tensions remain between the mainly British-descended populations of Canada, Australia and New Zealand and the indigenous minorities in those countries, and between settler minorities and indigenous majorities in South Africa and Zimbabwe. British settlement of Ireland continues to leave its mark in the form of divided Catholic and Protestant communities. Millions of people also moved between British colonies, for example from India to the Caribbean and Africa, creating the conditions for the ]. The makeup of Britain itself was changed after the Second World War with ] from the colonies to which it was granting independence.<ref>], p.135</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

==See also== |

|

|

{{portalpar|British Empire|British Empire 1897.jpg}} |

|

|

{{wikisourcecat}} |

|

|

{{commonscat}} |

|

|

* ] |

|

|

* ] |

|

|

* ] |

|

|

* ] |

|

|

* ] |

|

|

* ] |

|

|

* ] |

|

|

* ] |

|

|

|

|

|

== Notes == |

|

|

{{reflist|4}} |

|

|

|

|

|

== References == |

|

|

{{refbegin}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = David | last = Abernethy | title=The Dynamics of Global Dominance, European Overseas Empires 1415-1980 |publisher=Yale University Press|year=2000|isbn=0300093144|ref=refAbernethy2000}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Kenneth | last = Andrews | title = Trade, Plunder and Settlement: Maritime Enterprise and the Genesis of the British Empire, 1480-1630 | publisher = Cambridge Paperback Library | year=1985 | isbn=0521276985 | ref=refAndrews1985}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Judith | last = Brown | title = The Twentieth Century, The Oxford History of the British Empire Volume IV |publisher=Oxford University Press|year=1998 | isbn=0199246793 | ref=refOHBEv4}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Phillip | last = Buckner | title = Canada and the British Empire | publisher = Oxford University Press | year = 2008 | isbn = 019927164X | ref=refBuckner2008}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Kathleen | last = Burke| title=Old World, New World: Great Britain and America from the Beginning|publisher=Atlantic Monthly Press|year=2008|isbn=0871139715|ref=refBurke2008}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Nigel | last = Dalziel | title=The Penguin Historical Atlas of the British Empire|publisher=Penguin|year=2006|isbn=0141018445|ref=refDalziel2006}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Saul | last = David |title=The Indian Mutiny |publisher=Penguin|year=2003|isbn=0670911372|ref=refDavid2003}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Niall | last = Ferguson | title = Colossus: The Price of America's Empire | publisher = Penguin | year = 2004 | isbn = 1594200130 | ref=refFerguson2004}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Niall | last = Ferguson | title = Empire |publisher=Basic Books|year=2004 | isbn=0465023290 | ref=refFergusonEmpire2004}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Jonathan | last = Hollowell |title=Britain Since 1945 |publisher=Blackwell Publishing |year=2002|isbn=0631209689|ref=refHollowell2002}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Ronald | last = Hyam |title=Britain's Imperial Century, 1815-1914: A Study of Empire and Expansion |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|year=2002|isbn=033399311X|ref=refHyam2002}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Lawrence | last = James | title = The Rise and Fall of the British Empire |year=2001 |publisher=Abacus | isbn=031216985X | ref=refJames2001}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = T|last = Lloyd|title=The British Empire 1558-1995 |publisher=Oxford University Press|year=1996|isbn=0198731345|ref=refLloyd1996}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Thomas | last= Macaulay | title = The History of England | publisher=Pengiun | year=1979 | isbn=0140431330 | ref=refMacaulay1979}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Robert | last = MacCrum | title=The Story of English |publisher=Faber and Faber|year=1992|isbn=0140154051|ref=refMacrum1992}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Angus | last = Maddison | title = The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective | publisher = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development | year = 2001 | ref=refMaddison2001}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Magnus | last = Magnusson |title = Scotland: The Story of a Nation |publisher=Grove Press|year=2003 | isbn=0802139329 | ref=refMagnusson2003}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = PJ | last = Marshall | title = The Eighteenth Century, The Oxford History of the British Empire Volume II |publisher=Oxford University Press|year=1998 | isbn=0199246777 | ref=refOHBEv2}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Iain | last = McLean |title=Rational Choice and British Politics: An Analysis of Rhetoric and Manipulation from Peel to Blair |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2001|isbn=0198295294|ref=refMcLean2001}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Canny | last = Nicholas | title = The Origins of Empire, The Oxford History of the British Empire Volume I |publisher=Oxford University Press|year=1998 | isbn=0199246769 | ref=refOHBEv1}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = James | last = Olson | title=Historical Dictionary of the British Empire: A-J|publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group|year=1996|isbn=031329366X|ref=refHDBEv1}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Anthony | last = Pagden |title = Peoples and Empires: A Short History of European Migration, Exploration, and Conquest, from Greece to the Present |publisher=Modern Library |year=2003|isbn=0812967615|ref=refPagden2003}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Timothy H | last = Parsons |title=The British Imperial Century, 1815-1914: A World History Perspective |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |year=1999|isbn=0847688259|ref=refParsons}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Andrew | last = Porter | title = The Nineteenth Century, The Oxford History of the British Empire Volume III |publisher=Oxford University Press|year=1998 | isbn=0199246785 | ref=refOHBEv3}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Simon | last = Smith |title=British Imperialism 1750-1970 |publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=1998|isbn=052159930X|ref=refSmith1998}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Alan | last = Taylor |title = American Colonies, The Settling of North America |publisher=Penguin|year=2001 | isbn=0142002100 | ref=refTaylor2001}} |

|

|

*{{cite book | first = Margaret | last = Thatcher | title=The Downing Street Years |publisher=Harper Collins|year=1993|isbn=0060170565|ref=refThatcher}} |

|

|

*{{cite encyclopedia|last=Wright|first=Donald R.|title=Berlin West Africa Conference|url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761595821/berlin_west_africa_conference.html|encyclopedia=Encarta Online Encyclopedia|date=2007}} |

|

|

*{{cite news | url = http://encyclopedia.farlex.com/British+Empire+(World+War+I)|title= WW1 Dominion Armies| publisher= Farlex encyclopedia|accessdate=|date}} |

|

|

{{refend}} |

|

|

|

|

|

==External links== |

|

|

* |

|

|

* |

|

|

* - UK government site |

|

|

|

|

|

{{Colonialism}} |

|

|

{{Territories of the British Empire}} |

|

|

{{Empires}} |

|

|

|

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

|

|

|

{{Link FA|de}} |

|

|

|

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

|

] |

|

Flag

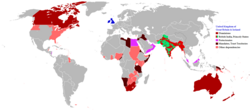

Flag An anachronous map of the British Empire.

An anachronous map of the British Empire.