| Revision as of 01:17, 20 October 2005 editTenebrae (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users155,424 edits →Return of Jack Kirby← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:19, 20 October 2005 edit undoTenebrae (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users155,424 editsmNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| '''Atlas Comics''' is the ] and early ] ] ] company that would evolve into ''']'''. ] and ] publisher ], whose ] involved having a multitude of ] entities, used Atlas as the umbrella name for his comic-book division during this time. Atlas was located on the 14th floor of the ]. | '''Atlas Comics''' is the ] and early ] ] ] company that would evolve into ''']'''. ] and ] publisher ], whose ] involved having a multitude of ] entities, used Atlas as the umbrella name for his comic-book division during this time. Atlas was located on the 14th floor of the ]. | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| This company is distinct from the 1970s comic-book company, also founded by Goodman, that is generally known as ]. | This company is distinct from the 1970s comic-book company, also founded by Goodman, that is generally known as ]. | ||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

| ==Return of Jack Kirby== | ==Return of Jack Kirby== | ||

| ] & ]]] | ] & ]]] | ||

| Goodman's men's magazines and paperback books were still successful — the comics, except in the early Golden Age, were always a relatively small part of the business — and Goodman considered shutting the division down. | Goodman's men's magazines and paperback books were still successful — the comics, except in the early Golden Age, were always a relatively small part of the business — and Goodman considered shutting the division down. | ||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

| ==Atlas or Marvel?== | ==Atlas or Marvel?== | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| The exact point at which "Atlas" became "Marvel" has never been definitively established. However, collectors routinely refer to the companies' comics from the April ] cover-dates onward (when they began featuring Jack Kirby artwork on his return to Goodman's company), as '''pre-superhero Marvel'''. | The exact point at which "Atlas" became "Marvel" has never been definitively established. However, collectors routinely refer to the companies' comics from the April ] cover-dates onward (when they began featuring Jack Kirby artwork on his return to Goodman's company), as '''pre-superhero Marvel'''. | ||

Revision as of 01:19, 20 October 2005

Atlas Comics is the 1950s and early 1960s comic book publishing company that would evolve into Marvel Comics. Magazine and paperback-novel publisher Martin Goodman, whose business strategy involved having a multitude of corporate entities, used Atlas as the umbrella name for his comic-book division during this time. Atlas was located on the 14th floor of the Empire State Building.

This company is distinct from the 1970s comic-book company, also founded by Goodman, that is generally known as Atlas/Seaboard Comics.

After the Golden Age

Atlas grew out of Timely Comics, the company Goodman founded in 1939 and whose star characters during the 1930s and '40s Golden Age of comic books were the Human Torch, the Sub-Mariner, and Captain America.

With the end of the wartime boom years — when superheroes were new and inspirational, and comics provided cheap entertainment for millions of children, soldiers and others — the post-war era found superheroes falling out of fashion. Television and paperback books now also competed for readers and leisure time.

The line marking the end of the Golden Age is vague, but for Timely, at least, it appears to have ended with the cancelation of Captain America Comics at issue #75 (Feb. 1950) — by which time the series had already been Captain America's Weird Tales for two issues, with the finale featuring merely anthological suspense stories and no superheroes. The company's flagship title, Marvel Mystery Comics, starring the Human Torch, had already ended its run (with #92, June 1949), as had Sub-Mariner Comics (with #32, the same month).

Whatever the demarcation point, Goodman began using the globe logo of Atlas (shown above), the newsstand-distribution company he owned, on comics cover-dated Nov. 1951. This united a line put out by the same publisher, staff and freelancers through 59 shell companies, from Animirth Comics to Zenith Publications

Atlas would attempt to revive superheroes in Young Men #24-28 (Dec. 1953-June 1954), with Golden Age stars the Human Torch (art by Syd Shores and Dick Ayers, variously), the Sub-Mariner (written and drawn by Bill Everett), and Captain America (by writer Stan Lee and artist John Romita Sr.). Yet while the stories were updated to the Cold War '50s, they featured the same sort of Communist Red Scare villains as the post-war comics of the late '40s, and broke no new ground.

DC Comics' Showcase #4 (Sept. 1956) would successfully bring back superheroes two years later and kick off the Silver Age of comic books, starting with a modern, uncluttered, streamlined reimagining of super-speedster The Flash.

Trend-following

Atlas, rather than similarly innovate, took what it saw as the proven route of following popular trends in TV and motion pictures — Westerns and war dramas prevailing for a time, drive-in sci-fi monsters another time — and even other comic book, most notably the groundbreaking EC horror line. Until Stan Lee, Goodman's comics-division editor-in-chief and head writer, would help revolutionize comic books with the advent of The Fantastic Four and Spider-Man in the early 1960s, Atlas was content to flooding newsstands with cheaply produced, profitable product — often, in spite of this strategy, beautifully rendered by talented if low-paid young artists.

Goodman's "everything but the kitchen sink" approach resulted in a wider variety of genres than even Timely had published, emphasizing horror, Westerns, humor, crime and war comics, with a healthy helping of jungle books and romance titles, and even espionage, medieval adventure, Bible stories and sports. The writing staff during this period included five scripters besides Lee: Don Rico, Hank Chapman, Carl Wessler, Paul S. Newman, and, in the teen-humor division, future MAD Magazine cartoonist Al Jaffee.

Among the notable artists whose work graced Atlas were Human Torch creator Carl Burgos, who did exquisite covers for the Young Men superhero-revival attempt. Fellow veteran Bill Everett had honed his stories and art for Sub-Mariner stories and for the modern-mythological series Venus into the kind of sleek, clean lines that DC's Carmine Infantino and Murphy Anderson (The Flash) and Gil Kane (Green Lantern) would later use to refresh the field.

There was the prolific and much-admired young draftsman Joe Maneely, whose work in all genres but particularly Westerns and on the medieval adventure title The Black Knight, produced an exquiste ouevre until his untimely death just prior to Marvel's 1960s pop-culture breakthrough. The shadowy, voluptuous textures of Russ Heath suspense tales, the languid fluidity of Gene Colan war stories, and the sharp, individualistic stylings of fledgling Steve Ditko's quirky bagatelles provided treasures amid the trash.

Humor and miscellanea

Atlas also published a plethora of children's and teen humor titles, including Archie Comics great Dan DeCarlo's Homer, the Happy Ghost (similar to Casper the Friendly Ghost) and Homer Hooper (who bore a striking resemblance to Archie Andrews), as well as more sitcomy fare like John Severin's Sgt. Bilko-esque Sergeant Barkey Barker.

One of the most popular was the long-running Millie the Model, which began as a Timely Comics humor title in 1945 and ran a remarkable 207 issues, well into the Marvel-era '70s, launching several spin-offs along the way. It became the proving ground for cartoonist DeCarlo — the future creator of Josie and the Pussycats and other Archie characters, and the artist who established Archie's modern look. He wrote and drew Millie for a remarkable ten years, from 1949-59, even while such companions titles as Tillie the Typist and Nellie the Nurse fell by the wayside.

Giving Millie competion was the high-schooler star of 'Patsy Walker, which also debuted in 1945, ran 99 issues to Feb. 1962, and spun-off Patsy & Hedy and Patsy and Her Pals. More naturalistic than Millie, it featured attractive but sedate art by Al Hartley, Al Jaffee, Morris Weiss and others — and, oddly, several early issues with the legendary Harvey Kurtzman's bizarre "Hey Look!" one-pagers. Patsy herself would be integrated into Marvel Universe continuity years later as the supernatural superheroine Hellcat.

No hellcats graced Atlas' funny animal books, but they did have Ed Winiarski's trouble-prone Buck Duck, Joe Maneely's mentally suspect Dippy Duck, and Howie Post's The Monkey and the Bear, which bore a striking resemblance to DC Comics' licensed animation title Fox and the Crow. Buck and others saw life again briefly in early 1970s when Marvel published the five-issue reprint title, Li'l Pals ("Fun-Filled Animal Antics!")

Notable miscellanea include the espionage title Yellow Claw, with sumptuous Joe Maneely, Jack Kirby and Severin art; the Native American hero Red Warrior, with art by Tom Gill; the Tom Corbett: Space Cadet-like Space Squadron, written and drawn by future Marvel production executive Sol Brodsky; and Sports Action, initially with true-life stories about the likes of George Gipp and Jackie Robinson, and later with fictional "Rugged Tales of Danger and Red-Hot Action!"

Atlas shrugs

From 1952 to late 1956, Goodman distributed this torrent of comics to newsstands through his self-owned distributor, Atlas. He then switched to another distributor that quickly went bankrupt. Stan Lee, in a 1988 interview , recalled that Goodman:

"...had gone with the American News Company. I remember saying to him, 'Gee, why did you do that? I thought that we had a good distribution company.' His answer was like, 'Oh, Stan, you wouldn't understand. It has to do with finance.' I didn't really give a damn, and I went back to doing the comics. e were left without a distributor and we couldn't go back to distributing our own books because the fact that Martin quit doing it and went with American News had gotten the wholesalers very angry ... and it would have been impossible for Martin to just say, 'Okay, we'll go back to where we were and distribute our books.' turning out 40, 50, 60 books a month, maybe more, and the only company we could get to distribute our books was our closest rival, National (DC) Comics. Suddenly we went ... to either eight or 12 books a month, which was all Independent News Distributors would accept from us."

For that and other reasons, including a small recession in the overall economy, Atlas retrenched. A fabled story has the publisher discovering a closet-full of unused, but paid-for, art, leading him to have virtually the entire staff fired while he used up the inventory. In the interview noted above, Lee, one of the few able to give a first-hand account, gave his perspective on the downsizinbg:

"It would never have happened just because he opened a closet door. But I think that I may have been in a little trouble when that happened. We had bought a lot of strips that I didn't think were really all that good, but I paid the artists and writers for them anyway, and I kinda hid them in the closet! And Martin found them and I think he wasn't too happy. If I wasn't satisfied with the work, I wasn't supposed to have paid, but I was never sure it was really the artist's or the writer's fault. But when the job was finished I didn't think that it was anything that I wanted to use. I felt that we could use it in inventory — put it out in other books. Martin, probably rightly so, was a little annoyed because it was his money I was spending."

Return of Jack Kirby

Goodman's men's magazines and paperback books were still successful — the comics, except in the early Golden Age, were always a relatively small part of the business — and Goodman considered shutting the division down.

The specific details of his decision not to are murky. Jack Kirby, who after his amicable split with creative partner Joe Simon, had not been as budy as he would have liked during this time, recalled in a 1990 interview for The Comics Journal that in late 1958 or early 1959,

"I came in and they were moving out the furniture, they were taking desks out — and I needed the work! ... Stan Lee is sitting on a chair crying. He didn't know what to do, he's sitting on a chair crying — he was still just out of his adolescence." "I told him to stop crying. I says, 'Go in to Martin and tell him to stop moving the furniture out, and I'll see that the books make money.'"Template:Fn

Interviewer and Comics Journal publisher Gary Groth later wrote of this interview in general, "Some of Kirby's more extreme statements ... should be taken with a grain of salt...."Template:Fn. Lee, specifically asked about the office-closing anecdote, said :

"I never remember being there when people were moving out the furniture. If they ever moved the furniture, they did it during the weekend when everybody was home. Jack tended toward hyperbole, just like the time he was quoted as saying that he came in and I was crying and I said, "Please save the company!" I'm not a crier and I would never have said that. I was very happy that Jack was there and I loved working with him, but I never cried to him. (laughs)"

Whatever the specific circumstances, Atlas gave Kirby a high-profile market, splashing the maestro's work across countless covers and lead stories, while the singular quality and dynamism of Kirby's art elevated such preexisting comics as Strange Tales and the newly launched Amazing Adventures, Tales of Suspense and Tales to Astonish above the look-alike fare of other horror/science fiction titles that had proliferated in EC's wake. A Kirby monster story, ususally inked by Dick Ayers, would generally open each book, followed by one or two twist-ending thrillers or sci-fi tales drawn by Don Heck, Paul Reinman, or Joe Sinnott, with the whole thing capped by a often-surreal, sometimes self-reflexive Lee-Ditko short.

Atlas or Marvel?

The exact point at which "Atlas" became "Marvel" has never been definitively established. However, collectors routinely refer to the companies' comics from the April 1959 cover-dates onward (when they began featuring Jack Kirby artwork on his return to Goodman's company), as pre-superhero Marvel.

Goodman had begun moving away from newsstand distributor Kable News by branding his comics with the Atlas globe on issues cover-dated Nov. 1951, even though Kable's "K" logo and North American map symbol remained through the Aug. 1952 issues. Goodman shut down his self-distributorship on Nov. 1, 1956, and began newsstand distrbution through American News Service. The Atlas globe remained, however, through the Oct. 1957 issues, when American News went out of business. Goodman switched to the distributor Independent News, owned by rival DC Comics, and dropped the Atlas globe at that time. Had American News continued, Goodman might have continued to brand the company Atlas.

Atlas titles by genre

This list is incomplete and in progress

CRIME

- Casey - Crime Photographer #1-4 (Aug. 1949-Feb. 1950)

ESPIONAGE

FUNNY ANIMAL

- Buck Duck #1-4 (June-Dec. 1953)

- Dippy Duck #1 (Oct. 1957)

- The Monkey and the Bear #1-3 (Sept. 1953-Jan. 1954)

- Wonder Duck #1-3 (Sept. 1949-March 1950), continued as

- It's a Duck's Life #4-11 (Nov. 1950-Feb. 1952)

HUMOR - SATIRE

- Crazy

- Riot

- Wild

HUMOR - SITCOM

- Millie the Model

- Sergeant Barney Barker #1-2 (Aug.-Dec. 1957)

- Continues as war title G.I. Tales

- Sherry the Showgirl #1-3 (July.-Dec. 1956), continued as

- Showgirls #4 (Feb. 1957), continued as

- Sherry the Showgirl #5-7 (April-Aug. 1957)

- Showgirls Vol. 2, #1-2 (July-Aug. 1957)

HORROR/SCIENCE FICTION

- Adventures into Terror

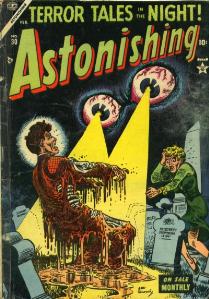

- Astonishing

- Journey into Mystery,

- Journey into Unknown Worlds

- Marvel Tales,

- Strange Stories of Suspense

- Strange Tales

- Strange Tales of the Unusual

- Suspense

JUNGLE

- Jann of the Jungle

- Jungle Action

- Jungle Tales

- Lorna, the Jungle Queen, retitled Lorna, the Jungle Girl

MEDIEVAL ADVENTURE

- The Black Knight

RELIGIOUS

- Bible Tales for Young Folk

ROMANCE

- The Romances of Nurse Helen Grant (one issue, Aug. 1957)

SPORTS

- Sport Stars #1 (Nov. 1949), continued as

- Sports Action #2-14 (Feb. 1950-Sept. 1952)

WAR

- Battle

- G.I. Tales #4-6 (Feb.-July 1957)

- Continued from humor title Sergeant Barney Barker

WESTERN

- Annie Oakley

References

- News from Me, Sept. 23, 2004: "More on Atlas Comics" by Tom Lammers and Mark Evanier

- The Marvel/Atlas Super-Hero Revival of the Mid-1950s

- Atlas Tales

- Marvel Database Project

- Marvel Directory

- Marvel Guide: An Unofficial Handbook of the Marvel Universe

- Big Comic Book DataBase: Marvel Comics

- A Timely Talk with Allen Bellman

- Timely Atlas Cover Gallery

- Collected Comics Library

- Marvel Masterworks Resource Pages

- The Jack Kirby Museum

- All in Color for a Dime by Dick Lupoff & Don Thompson ISBN 0873414985

- The Comic Book Makers by Joe Simon with Jim Simon ISBN 1887591354

- Excelsior! The Amazing Life of Stan Lee by Stan Lee and George Mair ISBN 0684873052

- Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics by Les Daniels ISBN 0810938219

Footnotes

- Template:Fnb Interview, The Comics Journal #134 (Feb. 1990), reprinted in The Comics Journal Library, Volume One: Jack Kirby (2002) ISBN 1560974664, p. 38

- Template:Fnb Ibid., p. 19