| Revision as of 19:52, 21 January 2009 view sourceClueBot (talk | contribs)1,596,818 editsm Reverting possible vandalism by 89.242.208.233 to version by Alansohn. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot. (539108) (Bot)← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:53, 21 January 2009 view source 89.242.208.233 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

| The term derives from the ] of the ], which stated that a mix of fluids known as humours (]: , ''chymos'', literally ] or ]; metaphorically, ]) controlled human health and emotion. | The term derives from the ] of the ], which stated that a mix of fluids known as humours (]: , ''chymos'', literally ] or ]; metaphorically, ]) controlled human health and emotion. | ||

| HOE | |||

| A '''sense of humour''' is the ability to experience humour, although the extent to which an individual will find something humorous depends on a host of ]s, including ], ], ], level of ], ], and ]. For example, young children may possibly favour ], such as ] puppet shows or cartoons (e.g., ]). ] may rely more on understanding the target of the humour, and thus tends to appeal to more mature audiences. Nonsatirical humour can be specifically termed "recreational drollery."<ref>Seth Benedict Graham '''' 2003 p.13</ref><ref>Bakhtin, Mikhail. ''Rabelais and His World'' . Trans. Hélène Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press p.12</ref> | A '''sense of humour''' is the ability to experience humour, although the extent to which an individual will find something humorous depends on a host of ]s, including ], ], ], level of ], ], and ]. For example, young children may possibly favour ], such as ] puppet shows or cartoons (e.g., ]). ] may rely more on understanding the target of the humour, and thus tends to appeal to more mature audiences. Nonsatirical humour can be specifically termed "recreational drollery."<ref>Seth Benedict Graham '''' 2003 p.13</ref><ref>Bakhtin, Mikhail. ''Rabelais and His World'' . Trans. Hélène Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press p.12</ref> | ||

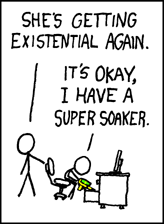

| ] can imply a sense of humour and a state of amusement, as in this painting by ].]] | ] can imply a sense of humour and a state of amusement, as in this painting by ].]] | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

| *One laughs at something that points out another's errors, lack of intelligence, or unfortunate circumstances, thereby granting a sense of superiority. | *One laughs at something that points out another's errors, lack of intelligence, or unfortunate circumstances, thereby granting a sense of superiority. | ||

| Whore | |||

| ] lamented the misuse of the term "humour" (a ] ] from ]) to mean any type of comedy. However, both "humour" and "comic" are often used when theorizing about the subject. The connotation of "humour" is more that of response, while "comic" refers more to stimulus. "Humour" also originally had a connotation of a combined ridiculousness and wit in one individual, the paradigm case being Shakespeare's Sir John Falstaff. The French were slow to adopt the term "humour," and in French, "humeur" and "humour" are still two different words, the former still referring only to the archaic concept of ]. | |||

| Western humour theory begins with ], who attributed to ] (as a semihistorical dialogue character) in the '']'' (p. 49b) the view that the essence of the ridiculous is an ignorance in the weak, who are thus unable to retaliate when ridiculed. Later, in Greek philosophy, ], in the '']'' (1449a, pp. 34–35), suggested that an ugliness that does not disgust is fundamental to humour. | Western humour theory begins with ], who attributed to ] (as a semihistorical dialogue character) in the '']'' (p. 49b) the view that the essence of the ridiculous is an ignorance in the weak, who are thus unable to retaliate when ridiculed. Later, in Greek philosophy, ], in the '']'' (1449a, pp. 34–35), suggested that an ugliness that does not disgust is fundamental to humour. | ||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

| In ancient ], ]'s '']'' defined humour (''hāsyam'') as one of the eight '']'', or principle '']'' (emotional responses), which can be inspired in the audience by ''bhavas'', the imitations of emotions that the actors perform. Each ''rasa'' was associated with a specific ''bhavas'' portrayed on stage. In the case of humour, it was associated with mirth (''hasya''). | In ancient ], ]'s '']'' defined humour (''hāsyam'') as one of the eight '']'', or principle '']'' (emotional responses), which can be inspired in the audience by ''bhavas'', the imitations of emotions that the actors perform. Each ''rasa'' was associated with a specific ''bhavas'' portrayed on stage. In the case of humour, it was associated with mirth (''hasya''). | ||

| The terms "]" and "]" became synonymous after Aristotle's ''Poetics'' was translated into ] in the ], where it was elaborated upon by ] and ] such as Abu Bischr, his pupil ], ], and ]. Due to cultural differences, they disassociated comedy from ]tic representation, and instead identified it with ] |

The terms "]" and "]" became synonymous after Aristotle's ''Poetics'' was translated into ] in the ], where it was elaborated upon by ] and ] such as Abu Bischr, his pupil ], ], and ]. Due to cultural differences, they disassociated comedy from ]tic representation, and instead identified it with ] themesASSWHOLES and forms, such as ''hija'' (satirical poetry). They viewed comedy as simply the "art of reprehension" and made no reference to light and cheerful events or troublous beginnings and happy endings associated with classical Greek comedy. After the ], the term "comedy" thus gained a new semantic meaning in ].<ref>{{citation|title=Comedy as Satire in Hispano-Arabic Spain|first=Edwin J.|last=Webber|journal=Hispanic Review|volume=26|issue=1|date=January 1958|publisher=]|pages=1-11}}</ref> | ||

| The Incongruity Theory originated mostly with ], who claimed that the comic is an expectation that comes to nothing. ] attempted to perfect incongruity by reducing it to the "living" and "mechanical."<ref>Henri Bergson, ''Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic'' (1900) English translation 1914.</ref> | The Incongruity Theory originated mostly with ], who claimed that the comic is an expectation that comes to nothing. ] attempted to perfect incongruity by reducing it to the "living" and "mechanical."<ref>Henri Bergson, ''Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic'' (1900) English translation 1914.</ref> | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

| Humour frequently contains an unexpected, often sudden, shift in perspective, which gets assimilated by the Incongruity Theory. This view has been defended by Latta (1998) and by ] (2004).<ref>Brian Boyd, Laughter and Literature: A Play Theory of Humor | Humour frequently contains an unexpected, often sudden, shift in perspective, which gets assimilated by the Incongruity Theory. This view has been defended by Latta (1998) and by ] (2004).<ref>Brian Boyd, Laughter and Literature: A Play Theory of Humor | ||

| PhilosophyBITCH and Literature - Volume 28, Number 1, April 2004, pp. 1-22</ref> Boyd views the shift as from seriousness to play. Nearly anything can be the object of this perspective twist; it is, however, in the areas of human creativity (science and art being the varieties) that the shift results from "structure mapping" (termed "]" by Koestler) to create novel meanings.<ref>Koestler, Arthur (1964): "The Act of Creation".</ref> Koestler argues that humour results when two different frames of reference are set up and a collision is engineered between them. | |||

| ], who is taking a more formalised computational approach than Koestler did, has written on the role of metaphor and metonymy in humour,<ref>Veal, Tony (2003): "Metaphor and Metonymy: The Cognitive Trump-Cards of Linguistic Humor"</ref><ref>Veale, Tony (2006): "The Cognitive Mechanisms of Adversarial Humor"</ref><ref>Veale, Tony (2004): "Incongruity in Humour: Root Cause of Epiphenomonon?"</ref> using inspiration from Koestler as well as from ]'s theory of structure-mapping, ] and ]'s theory of ], and ] and ]'s theory of ]. | ], who is taking a more formalised computational approach than Koestler did, has written on the role of metaphor and metonymy in humour,<ref>Veal, Tony (2003): "Metaphor and Metonymy: The Cognitive Trump-Cards of Linguistic Humor"</ref><ref>Veale, Tony (2006): "The Cognitive Mechanisms of Adversarial Humor"</ref><ref>Veale, Tony (2004): "Incongruity in Humour: Root Cause of Epiphenomonon?"</ref> using inspiration from Koestler as well as from ]'s theory of structure-mapping, ] and ]'s theory of ], and ] and ]'s theory of ]. | ||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

| ===Evolution of humour=== | ===Evolution of humour=== | ||

| As |

As witMUFFh any form of art, the same goes for humour: acceptance depends on social demographics and varies from person to person. Throughout history, comedy has been used as a form of entertainment all over the world, whether in the courts of the Western kings or the villages of the Far East. Both a social etiquette and a certain intelligence can be displayed through forms of wit and sarcasm. Eighteenth-century ] author ] said that "the more you know humour, the more you become demanding in fineness." | ||

| ⚫ | CUNTand cognitive explanation of how and why any individual finds anything funny. Effectively, it explains that humour occurs when the brain recognizes a pattern that surprises it, and that recognition of this sort is rewarded with the experience of the humorous response, an element of which is broadcast as laughter." The theory further identifies the importance of pattern recognition in human evolution: "An ability to recognize patterns instantly and unconsciously has proved a fundamental weapon in the cognitive arsenal of human beings. The humorous reward has encouraged the development of such faculties, leading to the unique perceptual and intellectual abilities of our species." | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ==Humour formulae== | ==Humour formulae== | ||

| Line 61: | Line 60: | ||

| ] explains in his lecture in the documentary "'']''"<ref>Rowan Atkinson/David Hinton, ''Funny Business'' (tv series), Episode 1 - aired 22 November 1992, UK, Tiger Television Productions</ref> that an object or a person can become funny in three different ways. They are: | ] explains in his lecture in the documentary "'']''"<ref>Rowan Atkinson/David Hinton, ''Funny Business'' (tv series), Episode 1 - aired 22 November 1992, UK, Tiger Television Productions</ref> that an object or a person can become funny in three different ways. They are: | ||

| *By behaving in an unusual way | *By behaving in an unusual way | ||

| *By being in an unusual |

*By being in an unusual placeASSOWOOLSLent International, 9''(1), 121-127. | ||

| *By being the wrong size | |||

| Most ]s fit into one or more of these categories. | |||

| Humour is also sometimes described as an ingredient in spiritual life. Humour is also the act of being funny. Some synonyms of funny or humour are hilarious, knee-slapping, spiritual, wise-minded, outgoing, and amusing. Some Masters have added it to their teachings in various forms. A famous figure in spiritual humour is the ]. | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| *]s | |||

| *] and ]s | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| **] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| *{{citation | last =Basu | first =S | title= Dialogic ethics and the virtue of humor | journal =Journal of Political Philosophy | publisher =Blackwell Publishing Ltd | date= December 1999 | volume =Vol. 7 | issue =No. 4 | pages =378-403 | url=http://www.anthrosource.net/doi/abs/10.1525/var.2006.22.1.14 | format =Abstract | doi =10.1111/1467-9760.00082 | accessdate =2007-07-06 }} (Abstract) | |||

| *Billig, M. (2005). ''Laughter and ridicule: Towards a social critique of humour''. London: Sage. ISBN 1412911435 | |||

| *Bricker, Victoria Reifler (Winter, 1980) '''' Journal of Anthropological Research, Vol. 36, No. 4, pp. 411-418 | |||

| *{{Citation | last =Buijzen | first =Moniek | last2 =Valkenburg | first2 =Patti M. | title =Developing a Typology of Humor in Audiovisual Media | journal =Media Psychology | volume =Vol. 6 | issue =No. 2 | pages =147-167 | date= 2004 | year =2004 | url =http://www.leaonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/s1532785xmep0602_2?prevSearch=allfield%3A(buijzen) | doi =10.1207/s1532785xmep0602_2 | id = }}(Abstract) | |||

| *Carrell, Amy (2000), '''', University of Central Oklahoma. Retrieved on 2007-07-06. | |||

| *{{Citation | last =García-Barriocanal | first =Elena | last2 =Sicilia | first2 =Miguel-Angel | last3 =Palomar | first3 =David | title =A Graphical Humor Ontology for Contemporary Cultural Heritage Access | | publisher =University of Alcalá | place =Ctra. Barcelona, km.33.6, 28871 Alcalá de Henares (Madrid), Spain, | date= 2005 | year =2005 | url=http://is2.lse.ac.uk/asp/aspecis/20050064.pdf | format=pdf | accessdate=2007-07-06}} | |||

| *Goldstein, Jeffrey H., et al. (1976) "Humour, Laughter, and Comedy: A Bibliography of Empirical and Nonempirical Analyses in the English Language." ''It's a Funny Thing, Humour''. Ed. Antony J. Chapman and Hugh C. Foot. Oxford and New York: Pergamon Press, 1976. 469-504. | |||

| *Holland, Norman. (1982) "Bibliography of Theories of Humor." ''Laughing; A Psychology of Humor''. Ithaca: Cornell U P, 209-223. | |||

| *] (2004) ] to his Italian translation of ]'s trilogy '']'', '']'' and '']'' (Bompiani, 2004, ISBN 88-452-3304-9 (57-65). | |||

| *Martin, Rod A. (2007). ''The Psychology Of Humour: An Integrative Approach.'' London, UK: Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 13: 978-0-12-372564-6 | |||

| *McGhee, Paul E. (1984) "Current American Psychological Research on Humor." Jahrbuche fur Internationale Germanistik 16.2: 37-57. | |||

| *Mintz, Lawrence E., ed. (1988) ''Humor in America: A Research Guide to Genres and Topics''. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1988. ISBN 0313245517; OCLC: 16085479. | |||

| *Mobbs, D., Greicius, M.D.; Abdel-Azim, E., Menon, V. & Reiss, A. L. (2003) "Humor modulates the mesolimbic reward centers". '''', '''40''', 1041-1048. | |||

| *Nilsen, Don L. F. (1992) "Satire in American Literature." ''Humor in American Literature: A Selected Annotated Bibliography.'' New York: Garland, 1992. 543-48. | |||

| *Pogel, Nancy, and Paul P. Somers Jr. (1988) "Literary Humor." ''Humor in America: A Research Guide to Genres and Topics''. Ed. Lawrence E. Mintz. London: Greenwood, 1988. 1-34. | |||

| *Roth, G., Yap, R, & Short, D. (2006). "Examining humour in HRD from theoretical and practical perspectives". ''Human Resource Development International, 9''(1), 121-127. | |||

| *Smuts, Aaron. "Humor". '''' | *Smuts, Aaron. "Humor". '''' | ||

| *{{citation | last =Wogan | first =Peter | title=Laughing At ''First Contact'' | journal =Visual Anthropology Review | date =Spring 2006 | volume =Vol. 22 | issue =No. 1 | pages =14-34 | publication-date =online December 12, 2006 | url=http://www.anthrosource.net/doi/abs/10.1525/var.2006.22.1.14 | format =Abstract | doi =10.1525/var.2006.22.1.14 | accessdate =2007-07-06 }} (Abstract) | *{{citation | last =Wogan | first =Peter | title=Laughing At ''First Contact'' | journal =Visual Anthropology Review | date =Spring 2006 | volume =Vol. 22 | issue =No. 1 | pages =14-34 | publication-date =online December 12, 2006 | url=http://www.anthrosource.net/doi/abs/10.1525/var.2006.22.1.14 | format =Abstract | doi =10.1525/var.2006.22.1.14 | accessdate =2007-07-06 }} (Abstract) | ||

Revision as of 19:53, 21 January 2009

For other uses, see Humour (disambiguation). "Hilarity" redirects here. For The U.S. Navy ship, see USS Hilarity (AM-241).Humour or humor is the tendency of particular cognitive experiences to provoke laughter and provide amusement. Many theories exist about what humour is and what social function it serves. People of most ages and cultures respond to humour. The majority of people are able to be amused, to laugh or smile at something funny, and thus they are considered to have a "sense of humour."

The term derives from the humoural medicine of the ancient Greeks, which stated that a mix of fluids known as humours (Greek: χυμός, chymos, literally juice or sap; metaphorically, flavour) controlled human health and emotion. HOE A sense of humour is the ability to experience humour, although the extent to which an individual will find something humorous depends on a host of variables, including geographical location, culture, maturity, level of education, intelligence, and context. For example, young children may possibly favour slapstick, such as Punch and Judy puppet shows or cartoons (e.g., Tom and Jerry). Satire may rely more on understanding the target of the humour, and thus tends to appeal to more mature audiences. Nonsatirical humour can be specifically termed "recreational drollery."

Understanding humour

| This section may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. No cleanup reason has been specified. Please help improve this section if you can. (January 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Humour occurs when

- An alternative (or surprising) shift in perception or answer is given that still shows relevance and can explain a situation.

- Sudden relief occurs from a tense situation. "Humourific," as formerly applied in comedy, referred to the interpretation of the sublime and the ridiculous, a relation also known as bathos. In this context, humour is often a subjective experience, as it depends on a special mood or perspective from its audience to be effective.

- Two ideas or things that are very distant in meaning emotionally or conceptually (i.e., having a significant incongruity) are juxtaposed.

- One laughs at something that points out another's errors, lack of intelligence, or unfortunate circumstances, thereby granting a sense of superiority.

Whore

Western humour theory begins with Plato, who attributed to Socrates (as a semihistorical dialogue character) in the Philebus (p. 49b) the view that the essence of the ridiculous is an ignorance in the weak, who are thus unable to retaliate when ridiculed. Later, in Greek philosophy, Aristotle, in the Poetics (1449a, pp. 34–35), suggested that an ugliness that does not disgust is fundamental to humour.

In ancient Sanskrit drama, Bharata Muni's Natya Shastra defined humour (hāsyam) as one of the eight nava rasas, or principle rasas (emotional responses), which can be inspired in the audience by bhavas, the imitations of emotions that the actors perform. Each rasa was associated with a specific bhavas portrayed on stage. In the case of humour, it was associated with mirth (hasya).

The terms "comedy" and "satire" became synonymous after Aristotle's Poetics was translated into Arabic in the medieval Islamic world, where it was elaborated upon by Arabic writers and Islamic philosophers such as Abu Bischr, his pupil Al-Farabi, Avicenna, and Averroes. Due to cultural differences, they disassociated comedy from Greek dramatic representation, and instead identified it with Arabic poetic themesASSWHOLES and forms, such as hija (satirical poetry). They viewed comedy as simply the "art of reprehension" and made no reference to light and cheerful events or troublous beginnings and happy endings associated with classical Greek comedy. After the Latin translations of the 12th century, the term "comedy" thus gained a new semantic meaning in Medieval literature.

The Incongruity Theory originated mostly with Kant, who claimed that the comic is an expectation that comes to nothing. Henri Bergson attempted to perfect incongruity by reducing it to the "living" and "mechanical."

An incongruity like Bergson's, in things juxtaposed simultaneously, is still in vogue. This is often debated against theories of the shifts in perspectives in humour; hence, the debate in the series Humor Research between John Morreall and Robert Latta. Morreall presented mostly simultaneous juxtapositions, with Latta countering that it requires a "cognitive shift" created by a discovery or solution to a puzzle or problem. Latta is criticized for having reduced jokes' essence to their own puzzling aspect.

Humour frequently contains an unexpected, often sudden, shift in perspective, which gets assimilated by the Incongruity Theory. This view has been defended by Latta (1998) and by Brian Boyd (2004). Boyd views the shift as from seriousness to play. Nearly anything can be the object of this perspective twist; it is, however, in the areas of human creativity (science and art being the varieties) that the shift results from "structure mapping" (termed "bisociation" by Koestler) to create novel meanings. Koestler argues that humour results when two different frames of reference are set up and a collision is engineered between them.

Tony Veal, who is taking a more formalised computational approach than Koestler did, has written on the role of metaphor and metonymy in humour, using inspiration from Koestler as well as from Dedre Gentner's theory of structure-mapping, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson's theory of conceptual metaphor, and Mark Turner and Gilles Fauconnier's theory of conceptual blending.

Some claim that humour cannot or should not be explained. Author E.B. White once said, "Humor can be dissected as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure scientific mind."

Evolution of humour

As witMUFFh any form of art, the same goes for humour: acceptance depends on social demographics and varies from person to person. Throughout history, comedy has been used as a form of entertainment all over the world, whether in the courts of the Western kings or the villages of the Far East. Both a social etiquette and a certain intelligence can be displayed through forms of wit and sarcasm. Eighteenth-century German author Georg Lichtenberg said that "the more you know humour, the more you become demanding in fineness." CUNTand cognitive explanation of how and why any individual finds anything funny. Effectively, it explains that humour occurs when the brain recognizes a pattern that surprises it, and that recognition of this sort is rewarded with the experience of the humorous response, an element of which is broadcast as laughter." The theory further identifies the importance of pattern recognition in human evolution: "An ability to recognize patterns instantly and unconsciously has proved a fundamental weapon in the cognitive arsenal of human beings. The humorous reward has encouraged the development of such faculties, leading to the unique perceptual and intellectual abilities of our species."

Humour formulae

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2006) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Root components:

- appealing to feelings or to emotions.

- similar to reality, but not real.

- some surprise/misdirection, contradiction, ambiguity, or paradox.

Methods:

Rowan Atkinson explains in his lecture in the documentary "Funny Business" that an object or a person can become funny in three different ways. They are:

- By behaving in an unusual way

- By being in an unusual placeASSOWOOLSLent International, 9(1), 121-127.

- Smuts, Aaron. "Humor". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Wogan, Peter (Spring 2006), "Laughing At First Contact" (Abstract), Visual Anthropology Review, Vol. 22 (No. 1) (published online December 12, 2006): 14–34, doi:10.1525/var.2006.22.1.14, retrieved 2007-07-06

{{citation}}:|issue=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|publication-date=(help) (Abstract)

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- International Society for Humor Studies

- No Laughing Matter: Visual Humor in Ideas of Race, Nationality and Ethnicity International Humanities Institute, Dartmouth College

- Seth Benedict Graham A cultural analysis of the Russo-Soviet Anekdot 2003 p.13

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World . Trans. Hélène Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press p.12

- Webber, Edwin J. (January 1958), "Comedy as Satire in Hispano-Arabic Spain", Hispanic Review, 26 (1), University of Pennsylvania Press: 1–11

- Henri Bergson, Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic (1900) English translation 1914.

- Robert L. Latta (1999) The Basic Humor Process: A Cognitive-Shift Theory and the Case against Incongruity, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 3110161036 (Humor Research no. 5)

- John Morreall (1983) Taking Laughter Seriously, Suny Press, ISBN 0873956427

- Brian Boyd, Laughter and Literature: A Play Theory of Humor PhilosophyBITCH and Literature - Volume 28, Number 1, April 2004, pp. 1-22

- Koestler, Arthur (1964): "The Act of Creation".

- Veal, Tony (2003): "Metaphor and Metonymy: The Cognitive Trump-Cards of Linguistic Humor"

- Veale, Tony (2006): "The Cognitive Mechanisms of Adversarial Humor"

- Veale, Tony (2004): "Incongruity in Humour: Root Cause of Epiphenomonon?"

- Rowan Atkinson/David Hinton, Funny Business (tv series), Episode 1 - aired 22 November 1992, UK, Tiger Television Productions