| Revision as of 03:29, 25 September 2009 editWadewitz (talk | contribs)50,892 editsm →Attachment patterns: ce← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:32, 25 September 2009 edit undoWadewitz (talk | contribs)50,892 editsm →Attachment patterns: ceNext edit → | ||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

| In the general population about 65% of children will have a secure classification, with 35% being divided amongst the insecure classifications. Early insecure attachment does not necessarily predict future difficulties but it is a liability for the child, particularly if the parental behaviours continue throughout childhood. Sometimes these difficulties reflect particular upheavals in people's lives which may change, and sometimes parents' responses change as the child develops. Fundamental changes can and do take place after the critical early period.<ref>Karen p. 248–66.</ref> Over the short term, stability of attachment classifications is high but becomes less so over the long term. The longer the gap between assessments the more children will have been found to have changed classification status.<ref name="Schaffer"/> It appears that stability of classification is linked to stability in caregiving conditions. Social stressors or negative life events such as illness, death, abuse or divorce are associated with instability of attachment patterns from infancy to early adulthood, particularly from secure to insecure.<ref name=delguid/> | In the general population about 65% of children will have a secure classification, with 35% being divided amongst the insecure classifications. Early insecure attachment does not necessarily predict future difficulties but it is a liability for the child, particularly if the parental behaviours continue throughout childhood. Sometimes these difficulties reflect particular upheavals in people's lives which may change, and sometimes parents' responses change as the child develops. Fundamental changes can and do take place after the critical early period.<ref>Karen p. 248–66.</ref> Over the short term, stability of attachment classifications is high but becomes less so over the long term. The longer the gap between assessments the more children will have been found to have changed classification status.<ref name="Schaffer"/> It appears that stability of classification is linked to stability in caregiving conditions. Social stressors or negative life events such as illness, death, abuse or divorce are associated with instability of attachment patterns from infancy to early adulthood, particularly from secure to insecure.<ref name=delguid/> | ||

| This situation is complicated by the difficulties in ] classification in older age groups. The Strange Situation procedure is for ages 12 to 18 months only. For older children, adolescents and adults, semi-structured interviews are used in which the manner of relaying content may be as significant as the content itself.<ref name="Schaffer"/> For pre-school children there are adapted versions of the Strange Situation procedure. Various techniques have been developed to ascertain verbally the |

This situation is complicated by the difficulties in ] classification in older age groups. The Strange Situation procedure is for ages 12 to 18 months only. For older children, adolescents and adults, semi-structured interviews are used in which the manner of relaying content may be as significant as the content itself.<ref name="Schaffer"/> For pre-school children there are adapted versions of the Strange Situation procedure. Various techniques have been developed to ascertain verbally the child's state of mind with respect to attachment. One example is the stem story technique in which a child is given a scenario that raises attachment issues and he or she is asked to complete the story. However, there are no substantially validated measures of attachment in middle childhood or early adolescence (approximately 7 to 13 years of age).<ref name=AACAP-2005>{{cite journal |journal= J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry |year=2005 |volume=44 |issue=11 |pages=1206–19 |title= Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with reactive attachment disorder of infancy and early childhood |author= Boris NW, Zeanah CH, Work Group on Quality Issues |pmid=16239871 |url=http://www.aacap.org/galleries/PracticeParameters/rad.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=200-09-13 |doi= 10.1097/01.chi.0000177056.41655.ce}}</ref> More recent research has sought to ascertain the extent to which a parent's attachment classification is predictive of their children's classification; it found that parents' perceptions of their own childhood attachments predicted their children's attachment classifications 75% of the time.<ref name="main 85">{{cite encyclopedia|author=Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J|year=1985|title=Security in infancy, childhood and adulthood: A move to the level of representation|editors=Bretherton I, Waters E|encyclopedia=Growing Points of Attachment Theory and Research|location=Chicago|publisher=University of Chicago press|isbn=978-0226074115}}</ref><ref name="fonagy 91">{{citejournal|author=Fonagy P, Steele M, Steele H|title=Maternal representations of attachment predict the organisation of infant mother–attachment at one year of age|journal=Child Development|volume=62|pages=891–905|doi=10.2307/1131141|year=1991}}</ref><ref name="steele">{{citejournal|author=Steele H, Steele M, Fonagy P|year=1996|journal=Child Development|title=Associations among attachment classifications of mothers, fathers, and their infants|volume=67|pages=541–55|doi=10.2307/1131831}}</ref> | ||

| Some authors have questioned the idea |

Some authors have questioned the idea that a taxonomy of categories representing qualitative difference in attachment relationships can be developed. A categorical model is not necessarily the best representation of individual difference in attachment. An examination of data from 1139 15-month-olds showed that variation was continuous rather than grouped.<ref name="FraSpe"/> This criticism introduces important questions for attachment typologies and the mechanisms behind apparent types, but in fact has relatively little relevance for attachment theory itself, which "neither requires nor predicts discrete patterns of attachment".<ref name="WatBea">{{citejournal|author = Waters E, Beauchaine TP|title = Are there really patterns of attachment? Comment on Fraley and Spieker (2003)|journal = Developmental Psychology|volume = 39|issue = 3|pages = 417–22; discussion 423–9|year = 2003|month = May|pmid = 12760512 |doi = 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.417}}</ref> | ||

| ==Significance of attachment patterns== | ==Significance of attachment patterns== | ||

Revision as of 03:32, 25 September 2009

Attachment theory is a psychological, evolutionary and ethological theory concerning relationships between humans. The most important tenet of attachment theory is that a young child needs a secure relationship to at least one primary adult caregiver for normal social and emotional development to take place. The theory was originated by psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby.

Within attachment theory, infant behaviour associated with attachment is primarily the seeking of proximity to an attachment figure in stressful situations. Infants become attached to adults who are sensitive and responsive in social interactions with the infant, and who remain as consistent caregivers for some months during the period from about six months to two years of age. During the latter part of this period, children begin to use attachment figures (familiar people) as a secure base to explore from and return to. Parental responses lead to the development of patterns of attachment which in turn lead to internal working models which will guide the individual's feelings, thoughts and expectations in later relationships. Separation anxiety or grief following serious loss is a normal and natural response in an attached infant. These behaviours have evolved because they increase the probability of survival of the child.

Research by developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth underpinned the basic concepts, introduced the concept of the "secure base" and developed a theory of a number of attachment patterns in infants: secure attachment, avoidant attachment, anxious attachment and, later, disorganised attachment. Theorists extended attachment theory to adults. Other interactions may be construed as including components of attachment behaviour; these include peer relationships at all ages, romantic and sexual attraction and responses to the care needs of infants or sick or elderly adults.

To formulate a comprehensive theory of the nature of early attachments, Bowlby explored a range of fields including evolution by natural selection, object relations theory (psychoanalysis), control systems theory, evolutionary biology and the fields of ethology and cognitive psychology. After preliminary papers from 1958 onwards, Bowlby published the full theory in the trilogy Attachment and Loss (1969–82). Although in the early days academic psychologists criticized Bowlby and the psychoanalytic community ostracised him, attachment theory has become the dominant approach to understanding early social development and given rise to a great surge of empirical research into the formation of children's close relationships. There have been significant modifications as a result of empirical research but attachment concepts have become generally accepted. Criticism of attachment theory has been sporadic, some of it relating to an early precursor hypothesis called "maternal deprivation", published in 1951. Past criticism came particularly from within psychoanalysis, and ethology, and in relation to the perceived emphasis on mothers. More recent criticisms relate to genetic factors, temperament, the complexity of social relationships within family settings, and the limitations of discrete patterns for classifications. Attachment concepts have been incorporated into existing therapeutic interventions and used to found attachment-based interventions. There are current efforts to evaluate a number of interventions and treatment approaches based on applications of attachment theory. Attachment theory concepts have also been utilised in the formulation of various social and child-care policies.

Attachment

Within attachment theory, attachment means a bond or tie between an individual and an attachment figure. Between two adults, such bonds may be reciprocal and mutual; however, from children toward a parental or caregiving figure, such bonds are likely to be asymmetric. The reason is inherent in the theory which proposes that the need for safety and protection, which is paramount in infancy and childhood, is the basis of the bond.

The theory posits that children attach to carers instinctively, for the purpose of achieving security, survival and, ultimately, genetic replication. The biological function is survival and the psychological function is security. Attachment theory is not an exhaustive description of human relationships, nor is it synonymous with love and affection although these may indicate that bonds exist. In the case of child-to-adult relationships, the child's tie is called the "attachment" and the caregiver's reciprocal equivalent is referred to as the "care-giving bond".

Almost from the first, many children have more than one figure towards whom they direct attachment behaviour. These figures are arranged in hierarchical order with the "principal attachment figure" at the top. If the figure is unavailable or unresponsive, separation distress occurs. The anticipation of such an occurrence arouses separation anxiety. Bowlby distinguished between alarm and anxiety: "alarm" was the term he used for activation of the attachment behavioural system caused by fear of danger, while "anxiety" was the fear of being cut off from the attachment figure (caregiver). In infants, physical separation can cause firstly anxiety and anger, and then sadness and despair. By 3 or 4 years of age, physical separation is no longer such a threat to the child's bond with the caregiver. Given that the set-goal of the attachment behavioural system is maintaining a bond with an accessible and available attachment figure, threats to felt security in older children and adults arise from prolonged absence, break-downs in communication, emotional unavailability or signs of rejection or abandonment.

Infants will form attachments to any consistent caregiver who is sensitive and responsive in social interactions with the infant. The quality of the social engagement appears to be more influential than amount of time spent. Although it is usual for the principal attachment figure to be the biological mother, the role can be taken by anybody who behaves in a "mothering" way over a consistent period, a set of behaviours that involves engaging in lively social interaction with the infant and responding readily to signals and approaches. Attachment theory accepts the customary primacy of the mother as the main caregiver and therefore the person who interacts most with a young child, but there is nothing in the theory to suggest that fathers are not equally likely to become principal attachment figures if they happen to provide most of the child care and related social interaction.

Attachment behaviours

The attachment behavioural system serves to maintain or achieve closer proximity to the attachment figure. Pre-attachment behaviours occur in the first six months. In the first 8 weeks infants use behaviours such as smiling, babbling and crying to attract the attention of caregivers.

Although babies are learning to discriminate between caregivers these behaviours are directed at anyone in the vicinity. Between two and six months the infant discriminates more and more between familiar and unfamiliar adults, becoming increasingly responsive towards the caregiver, adding following and clinging to its repertoire. Clear-cut attachment develops in the third phase, between the ages of six months to two years. The infant's behaviour towards the caregiver becomes organised on a goal-directed basis to achieve the conditions that make it feel secure. By the end of the first year the infant is able to display a range of attachment behaviours designed to maintain proximity to the caregiver such as protesting the caregiver's departure, greeting the caregiver's return, clinging when frightened and following when able. The infant increasingly discriminates between adults. With the development of locomotion the infant begins to use the caregiver or caregivers as a safe base from which to explore. Infant exploration is greater when the caregiver is present; with the caregiver present, the infant's attachment system is relaxed and it is free to explore. If the caregiver is inaccessible or unresponsive, attachment behaviour is strongly activated. Anxiety, fear, illness and fatigue will cause a child to increase attachment behaviours. Many attachment behaviours are likely to occur only in threatening or uncomfortable circumstances such as the approach of an unfamiliar person (stranger wariness). Thus, attachment may be present without being displayed behaviourally, and it may be impossible to measure its presence without creating such circumstances.

After the second year, as the child begins to see the carer as an independent person a more complex, goal-corrected partnership is formed. Whereas a baby will cry because of pain, a two year old will cry to summon their caregiver and if that does not work, cry louder or shout or follow. Children also begin to become aware of other people's goals and feelings and plan their actions accordingly. With adolescents, the role of the caregiver is to be available when needed while the adolescent makes sorties into the outside world.

Tenets

Attachment theory is a framework of ideas which connects observable human social behaviours and enables predictions to be made and tested. The basic tenets are as follows:

- Adaptiveness: Common human attachment behaviours and emotions are adaptive. The evolution of human beings has involved selection for social behaviours that make individual or group survival more likely. For example, the commonly observed attachment behaviour of toddlers includes staying near familiar people; this behaviour would have had safety advantages in the environment of early adaptation, and has such advantages today. Bowlby termed proximity-seeking to the attachment figure in the face of threat to be the "set-goal" of the attachment behavioural system. There is a survival advantage in the capacity to sense possibly dangerous conditions such as unfamiliarity, being alone or rapid approach, and such conditions are likely to activate the attachment behavioural system causing the infant or child to seek proximity to the attachment figure.

- Critical period: Certain changes in attachment, such as the infant's coming to prefer a familiar caregiver and avoid strangers, are most likely to occur within the period between the ages of about six months and two or three years. Bowlby's sensitivity period has been modified to a less "all or nothing" approach. Although there is a sensitive period during which it is highly desirable that selective attachments develop, the time frame is probably broader and the effects not so fixed and irreversible. With further research, authors discussing attachment theory have come to appreciate that social development is affected by later as well as earlier relationships.

- Robustness of development: Attachment to and preferences for some familiar people are easily developed by most young humans, even under far less than ideal circumstances.

Early experiences with caregivers gradually give rise to a system of thoughts, memories, beliefs, expectations, emotions, and behaviours about the self and others. - Experience as essential factor in attachment: Infants in their first months have no preference for their biological parents over strangers and are equally friendly to anyone who treats them kindly. Human beings develop preferences for particular people, and behaviours which solicit their attention and care, over a considerable period of time. When an infant is upset by separation from their caregiver this indicates that the bond no longer depends on the presence of the caregiver but is of an enduring nature.

- Monotropy: Early steps in attachment take place most easily if the infant has one caregiver, or the occasional care of a small number of other people. According to Bowlby, almost from the first many children have more than one figure towards whom they direct attachment behaviour. These figures are not treated alike and there is a strong bias for a child to direct attachment behaviour mainly towards one particular person. Bowlby used the term "monotropy" to describe this bias to attach primarily to one figure. Researchers and theorists have effectively abandoned this concept insofar as it may be taken to mean that the relationship with the special figure differs qualitatively from that of other figures. Rather, current thinking postulates definite hierarchies of relationships.

- Social interactions as cause of attachment: Feeding and relief of an infant's pain do not cause an infant to become attached to a caregiver. Infants become attached to adults who are sensitive and responsive in social interactions with the infant and who remain as consistent caregivers for some time.

- Internal working model: Early experiences with caregivers gradually give rise to a system of thoughts, memories, beliefs, expectations, emotions, and behaviours about the self and others. This system, called the internal working model of social relationships, continues to develop with time and experience and enables the child to handle new types of social interactions. For example, a child's internal working model helps him or her to know that an infant should be treated differently from an older child, or to understand that interactions with a teacher can share some of the characteristics of an interaction with a parent. An adult's internal working model continues to develop and to help cope with friendships, marriage, and parenthood, all of which involve different behaviours and feelings.

- Transactional processes: As attachment behaviours change with age, they do so in ways shaped by relationships, not by individual experiences. A child's behaviour when reunited with a caregiver after a separation is determined not only by how the caregiver has treated the child before, but on the history of effects the child has had on the caregiver.

- Consequences of disruption: In spite of the robustness of attachment, significant separation from a familiar caregiver, or frequent changes of caregiver that prevent development of attachment, may result in psychopathology at some point in later life.

- Developmental changes: Specific attachment behaviours begin with predictable, apparently innate, behaviour in infancy, but change with age in ways that are partly determined by experiences and by situational factors. For example, a toddler is likely to cry when separated from his mother, but an eight-year-old is more likely to call out, "When are you coming back to pick me up?" or to turn away and begin the familiar school day.

Changes in attachment after the infant-toddler period

Age, cognitive growth and continued social experience advance the development and complexity of the internal working model. Attachment-related behaviours lose some of the characteristics typical of the infant-toddler period and take on a series of age-related tendencies. The preschool period involves the use of negotiation and bargaining as part of attachment behaviour. Ideally these social skills become incorporated into the internal working model of social relationships, to be used with other children and later with adult peers. As children move into the school years, most develop a goal-corrected partnership with parents, in which each partner is willing to compromise in order to maintain a gratifying relationship. By middle childhood there may be a shift towards mutual co-regulation of secure-base contact.

In early childhood, parental figures remain the centre of children's social worlds, even if they spend substantial periods of time in alternative care. This lessens, particularly with entrance into formal schooling. In middle childhood (ages 7–11) the goal of the attachment behavioural system changes from proximity to the attachment figure to the availability of the attachment figure. Generally a child is content with longer separations provided contact or the possibility of reuniting, if needed, is available. There will be a decline in specific attachment behaviours such as clinging and following and an increase in self-reliance. Young children's attachment representations are typically assessed in relation to particular figures, as it appears that there are limitations in their thinking that limit their ability to integrate relationship experiences into a single general model. In the course of middle childhood, some children may begin to develop a generally consistent representation of attachment relationships, although this may not occur until adolescence.

Although peers become important in middle childhood, the evidence suggests that peers do not become attachment figures even though children may direct attachment behaviours at peers if parental figures are unavailable. Attachments to peers tend to emerge in adolescence although parents also continue to function as attachment figures. Relationships with peers have an influence distinct from that of parents but parent-child relationships can influence the peer relationships children form. For example, secure attachment status is said to promote social competence and positive peer relationships. Relationships formed with peers influence the acquisition of social skills, intellectual development and the formation of social identity. Classification of children's peer status (popular, neglected or rejected) has been found to predict subsequent adjustment; however, as with attachment to parental figures, subsequent experiences may well alter the course of development.

Attachment patterns

See also: Attachment in children and Attachment measuresMary Ainsworth's innovative methodology and comprehensive observational studies, particularly those undertaken in Scotland and the Ganda, informed much of the theory, expanded its concepts and enabled its tenets to be empirically tested. She conducted research, based on Bowlby's early formulation, by observing infant-parent dyads during the first year of a child's life on extensive home visits and by studying behaviours in particular situations. This early research was published in 1967 in Infancy in Uganda. She identified three attachment styles or patterns that a child may have with its primary attachment figure: secure, anxious-avoidant (insecure) and anxious-ambivalent or resistant (insecure). These patterns are not, strictly speaking, part of attachment theory but are very closely identified with it. She devised a procedure known as the Strange Situation Protocol as the laboratory portion of her larger study, to assess separation and reunion behaviour. This is still used in research today to assess attachment patterns in infants and toddlers. It can be used for research purposes because it is a standardised tool. By creating stresses designed to activate attachment behaviour, the procedure reveals what use very young children make of their caregiver as a source of security. In the procedure, the carer and child are placed in an unfamiliar playroom equipped with toys while a researcher observes and records specific behaviours through a one-way mirror. There are eight sequential episodes in which the child experiences both separation from and reunion with the carer, and the presence of an unfamiliar stranger, in various combinations.

Ainsworth's work in the USA attracted many scholars into the field, inspiring research and challenging the dominance of behaviouralism. Further research by Dr. Mary Main and colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley identified a fourth attachment pattern, called disorganised/disoriented attachment. The name reflects these children's lack of a coherent coping strategy.

The type of attachment developed by infants depends on the quality of care they have received. Each of the attachment patterns is associated with certain characteristic patterns of behaviour, as described in the following table:

| Attachment pattern |

Child | Caregiver |

|---|---|---|

| Secure | Uses caregiver as a secure base for exploration. Protests caregiver's departure and seeks proximity and is comforted on return, returning to exploration. May be comforted by the stranger but shows clear preference for the caregiver. | Responds appropriately, promptly and consistently to needs. |

| Avoidant | Little affective sharing in play. Little or no distress on departure, little or no visible response to return, ignoring or turning away with no effort to maintain contact if picked up. Treats the stranger similarly to the caregiver. | Little or no response to distressed child. Discourages crying and encourages independence. |

| Ambivalent/Resistant | Unable to use caregiver as a secure base, seeking proximity before separation occurs. Distressed on separation with ambivalence, anger, reluctance to warm to caregiver and return to play on return. Preoccupied with caregiver's availability, seeking contact but resisting angrily when it is achieved. Not easily calmed by stranger. | Inconsistent between appropriate and neglectful responses. |

| Disorganised | Stereotypes on return such as freezing or rocking. Lack of coherent attachment strategy shown by contradictory, disoriented behaviours such as approaching but with the back turned. | Frightened or frightening behaviour, intrusiveness, withdrawal, negativity, role confusion, affective communication errors and maltreatment. |

The presence of an attachment and its quality are distinct. Human infants will form attachments if there is someone to interact with, even if they are mistreated. The individual differences in the relationships reflect the history of care as through repeated interactions infants begin to predict the behaviour of their caregivers. "Maternal" or primary caregiver sensitivity is an important though not an exclusive condition for attachment security. Programmes and treatments designed to improve maternal sensitivity have shown significant improvements in secure classifications.

The focus in studying individual relationships is the organisation (pattern) rather than quantity of attachment related behaviours. Insecure attachment patterns are non-optimal in that they can compromise exploration and infants cannot therefore achieve the same confidence in themselves and mastery of the environment. However, insecure patterns are also adaptive in that they are suitable responses to the unresponsiveness of the caregivers. For example, in the avoidant pattern, minimising expressions of attachment even in conditions of mild threat may forestall alienating caregivers who are already rejecting and thus leave open the possibility of responsiveness should a more serious threat arise.

In the general population about 65% of children will have a secure classification, with 35% being divided amongst the insecure classifications. Early insecure attachment does not necessarily predict future difficulties but it is a liability for the child, particularly if the parental behaviours continue throughout childhood. Sometimes these difficulties reflect particular upheavals in people's lives which may change, and sometimes parents' responses change as the child develops. Fundamental changes can and do take place after the critical early period. Over the short term, stability of attachment classifications is high but becomes less so over the long term. The longer the gap between assessments the more children will have been found to have changed classification status. It appears that stability of classification is linked to stability in caregiving conditions. Social stressors or negative life events such as illness, death, abuse or divorce are associated with instability of attachment patterns from infancy to early adulthood, particularly from secure to insecure.

This situation is complicated by the difficulties in assessing attachment classification in older age groups. The Strange Situation procedure is for ages 12 to 18 months only. For older children, adolescents and adults, semi-structured interviews are used in which the manner of relaying content may be as significant as the content itself. For pre-school children there are adapted versions of the Strange Situation procedure. Various techniques have been developed to ascertain verbally the child's state of mind with respect to attachment. One example is the stem story technique in which a child is given a scenario that raises attachment issues and he or she is asked to complete the story. However, there are no substantially validated measures of attachment in middle childhood or early adolescence (approximately 7 to 13 years of age). More recent research has sought to ascertain the extent to which a parent's attachment classification is predictive of their children's classification; it found that parents' perceptions of their own childhood attachments predicted their children's attachment classifications 75% of the time.

Some authors have questioned the idea that a taxonomy of categories representing qualitative difference in attachment relationships can be developed. A categorical model is not necessarily the best representation of individual difference in attachment. An examination of data from 1139 15-month-olds showed that variation was continuous rather than grouped. This criticism introduces important questions for attachment typologies and the mechanisms behind apparent types, but in fact has relatively little relevance for attachment theory itself, which "neither requires nor predicts discrete patterns of attachment".

Significance of attachment patterns

There is an extensive body of research demonstrating a significant association between attachment organisations and children's functioning across multiple domains. The link between insecure attachment, particularly the disorganised classification, and the emergence of childhood psychopathology is well established although it is a non-specific risk factor for future problems, not a pathology or a direct cause of pathology in itself. In the classroom, it appears that ambivalent children are at an elevated risk for internalizing disorders and avoidant and disorganised children for externalizing disorders.

Compared to securely attached children, the adjustment of insecure children in many spheres of life is not as soundly based and their future relationships are put in jeopardy. Although the link is not fully established by research and there are other influences besides attachment to be taken into account, secure infants are more likely to become more socially competent than their insecure peers. Social competence and popularity are linked to cognitive development. Research based on data from longitudinal studies, such as the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care and the Minnesota Study of Risk and Adaption from Birth to Adulthood, and from cross-sectional studies, consistently shows associations between early attachment classifications and peer relationships as to both quantity and quality. Predictions are stronger for close relationships that for less intimate ones. Secure children have more positive and fewer negative peer reactions and establish more and better friendships. Insecure children tend to be followers rather than leaders. Insecure-ambivalent children have a tendency to anxiously but unsuccessfully seek positive peer interaction whereas insecure-avoidant children appear aggressive and hostile and may actively repudiate positive peer interaction. There is no established direct association between early experience and a comprehensive measure of social functioning in early adulthood but early experience significantly predicts early childhood representations of relationships, which in turn predicts later self and relationship representations and social behaviour. Behavioural problems and social competence in insecure children increase or decline with deterioration or improvement in quality of parenting and the degree of risk in the family environment. Avoidant children are especially vulnerable to family risk. However an early secure attachment appears to have a lasting protective function.

There is some evidence that sex-differences in attachment patterns of adaptive significance begin to emerge in middle childhood. Insecure attachment and early psychosocial stress indicate environmental risk. This can tend to favour the development of strategies for earlier reproduction. However, different patterns have different adaptive values for males and females. Insecure males tend to adopt avoidant strategies whereas insecure females tend to adopt anxious/ambivalent strategies, unless they are in a very high risk environment. Adrenarche is proposed as the endocrine mechanism underlying the reorganization of insecure attachment in middle childhood.

The most concerning pattern is disorganised attachment. About 80% of maltreated infants are likely to be classified as disorganised as opposed to about 12% found in non-maltreated samples. Only about 15% of maltreated infants are likely to be classified as secure. Children with a disorganised pattern in infancy tend to show markedly disturbed patterns of relationships. Their subsequent relationships with peers are often characterised by a "fight or flight" pattern of alternate aggression and withdrawal. Maltreated children are more likely to become maltreating parents, passing on the disordered relationship pattern. A minority do not, achieving instead secure attachments, good relationships with peers and non-abusive parenting styles.

One explanation for the effects of early attachment classifications may lie in the internal working model mechanism. These internal models are not just "pictures" but also refer to the feelings aroused. Their function is to enable a person to anticipate and interpret another's behaviour in the context of relationships and so plan a response. If an infant experiences their caregiver as a source of security and support the infant is more likely to develop a positive self-image and to expect positive reactions from others as they will generalize positive expectations from their internal model of relationships. Conversely a child from an abusive relationship may internalise a negative self-image and generalize negative expectations into other relationships. The internal working models on which attachment behaviour is based show a degree of continuity and stability. Children are likely to fall into the same categories as their primary caregiver indicating that the caregivers internal working model affects the way they relate to their child. This effect has been observed to continue across three generations. Bowlby believed that the earliest models formed were the most likely to persist because they existed outside consciousness. However such models are not impervious to change given further relationship experiences and indeed a minority of children have different attachment classifications with different caregivers.

Attachment in adults

See also: Attachment in adults and Attachment measuresAttachment theory was extended to adult romantic relationships in the late 1980s by Cindy Hazan and Phillip Shaver. Four styles of attachment have been identified in adults: secure, anxious-preoccupied, dismissive-avoidant, and fearful-avoidant. These roughly correspond to infant classifications of secure, insecure-ambivalent, insecure-avoidant and disorganised/disorientated. Securely attached people tend to have positive views of themselves, their partners and their relationships. They feel comfortable with intimacy and independence and balance the two in their relationships. Anxious-preoccupied adults seek high levels of intimacy, approval, and responsiveness from partners and may become overly dependent. They tend to have less positive views about themselves and their partners and less trust. They may exhibit high levels of emotional expressiveness, worry, and impulsiveness in their relationships. Dismissive-avoidant adults desire a high level of independence, often appearing to avoid attachment altogether. They view themselves as self-sufficient and invulnerable to attachment feelings and often deny needing close relationships. They tend to suppress and hide their feelings and deal with rejection by distancing themselves from partners of whom they often have a poor view.

Fearful-avoidant adults have mixed feelings about close relationships, both desiring and feeling uncomfortable with emotional closeness. They tend to view themselves as unworthy and mistrust their partners. As with the dismissive-avoidant style, they tend to seek less intimacy and to suppress and hide their feelings.

There are two main aspects of adult attachment studied. One is the organisation and stability of the mental working models that underlie the attachment styles. This is explored by social psychologists interested in romantic attachment. The other is how attachment functions in relationship dynamics and impacts relationship outcomes. This concept of attachment status is generally explored by developmental psychologists interested in the individual's state of mind with respect to attachment. The latter is more stable, while the former fluctuates more. Some authors have suggested that adults' internal working models do not have just one perspective, but use a hierarchy of models containing general ideas about close relationships, and within those, information related to specific relationships or even specific events within a relationship. One idea about this hierarchy of internal working models is that information at different levels need not be consistent.

Attachment in adults is commonly measured using the Adult Attachment Interview and self-report questionnaires. Self-report questionnaires have identified two dimensions of attachment, one dealing with anxiety about the relationship, and the other with avoidance in the relationship. For research a wide variety of measures are used, the most popular in social psychological research being the Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised scale.

Developments

Whereas Bowlby was inspired by insights into children's thinking from Piaget, current attachment scholars utilise newer insights deriving from contemporary literature and research on implicit knowledge, theory of mind, autobiographical memory and social representation. Psychoanalyst and psychologist Peter Fonagy and Mary Target have attempted to bring attachment theory and psychoanalysis into a closer relationship by way of such aspects of cognitive science as mentalization. Mentalization, or theory of mind, is the capacity of human beings to guess with some accuracy what thoughts, emotions, and intentions lie behind behaviours as subtle as facial expression or eye movement. The connection of theory of mind with the internal working model of social relationships may open new areas of study and lead to alterations in attachment theory.

One focus of attachment research has been on the difficulties of children whose attachment history was poor, including those with extensive non-parental child care experiences. Concern with the effects of child care was intense during the so-called "day care wars" of the late 20th century, during which some authors stressed the deleterious effects of day care. As a result of this controversy, training of child care professionals has come to stress attachment issues and the need for relationship-building through techniques such as assignment of a child to a specific care provider. Although only high-quality child care settings are likely to follow through on these considerations, nevertheless a larger number of infants in child care receive attachment-friendly care than in the past. The emotional development of children in non-parental care may be different today than it was in the 1980s or in Bowlby's time.

Another significant area of research and development has been in the area of the connection between problematic attachment patterns, particularly disorganised attachment, and the risk of later psychopathology. A third has been in the area of the effect on development of children having little or no opportunity to form attachments at all in their early years. A "natural experiment" permitted extensive study of attachment issues, as researchers followed thousands of Romanian orphans who were adopted into Western families after the end of the Ceasescu regime. The English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team, led by Michael Rutter, followed some of the children into their teens, attempting to unravel the effects of poor attachment, adoption and new relationships, and the physical and medical problems associated with their early lives. Studies on the Romanian adoptees, whose initial conditions were shocking, yielded reason for optimism. Many of the children developed quite well, and the researchers noted that separation from familiar people is only one of many factors that help to determine the quality of development.

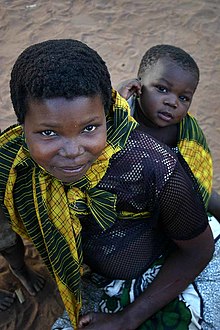

Authors considering attachment in non-western cultures have noted the connection of attachment theory with Western family and child care patterns characteristic of Bowlby's time. The implication of this connection is that attachment-related experiences (and perhaps attachment itself) may alter as children's experience of care change historically. For example, changes in attitudes toward female sexuality have greatly increased the numbers of children living with their never-married mothers and being cared for outside the home while the mothers work. This social change, in addition to increasing abortion rates, has also made it more difficult for childless people to adopt infants in their own countries. There has been an increase in the number of older-child adoptions and adoptions from third-world sources in first-world countries. Adoptions and births to same-sex couples have increased in number and gained legal protection, compared to their status in Bowlby's time. Issues about attachment theory have been raised with regard to the fact that infants often have multiple relationships, both within the family and in child care settings, and that the dyadic model characteristic of attachment theory cannot address the complexity of real-life social experiences.

History

Main articles: History of attachment theory and Maternal deprivationEarlier theories

The concept of infants' emotional attachment to caregivers has been known anecdotally for hundreds of years. From the late nineteenth century onward, psychologists and psychiatrists suggested theories about attachment. Early Freudian theory had little to say about a child's relationship with the mother, considering only that the breast was the love object, but Freudians attributed the infant's attempts to stay near the familiar person to motivation learned through feeding experiences and gratification of libidinal drives. In the 1930s, the British developmentalist Ian Suttie suggested that the child's need for affection was a primary one, not based on hunger or other physical gratifications. William Blatz, a Canadian psychologist and teacher of Mary Ainsworth, was among the first to stress the need for security as a normal part of personality at all ages, as well as the use of others as a secure base and the importance of social relationships for development. Most early observers from the 1940s onward focused on the anxiety displayed by infants and toddlers when threatened with separation from a familiar caregiver.

Another theory prevalent at the time of Bowlby's development of attachment theory was "dependency". This approach posited that infants were dependent on adult caregivers but that dependency was, or should be, outgrown as the individual matured. According to this way of thinking, attachment behaviour in older children would be seen as regressive, whereas attachment theory assumes that older children and adults retain attachment behaviour and display it in stressful situations; indeed, a secure attachment is associated with independent exploratory behaviour rather than dependence. Current attachment theory focuses on social experiences in early childhood as the source of attachment in childhood and in later life. Bowlby developed attachment theory as a consequence of his dissatisfaction with existing theories of early relationships.

Early developments

The early thinking of the object relations school of psychoanalysis and particularly Melanie Klein influenced Bowlby. However he profoundly disagreed with the then prevalent psychoanalytic belief that infants' responses relate to their internal fantasy life rather than to real-life events. As Bowlby began to formulate his concept of attachment, he was influenced by many case studies on disturbed and delinquent children, including his own and those of Goldfarb. Bowlby's contemporary René Spitz made observations of separated children's grief and proposed that "psychotoxic" results were brought about by inappropriate experiences of early care. A strong influence was the work of social worker and psychoanalyst James Robertson who filmed the effects of separation on children in hospital and collaborated with Bowlby in making the 1952 documentary film A Two-Year Old Goes to the Hospital which was instrumental in a campaign to alter hospital restrictions on visiting by parents.

In his 1951 monograph for the World Health Organisation, Maternal Care and Mental Health, Bowlby put forward the hypothesis that "the infant and young child should experience a warm, intimate, and continuous relationship with his mother (or permanent mother substitute) in which both find satisfaction and enjoyment" and that lack of this experience may have significant and irreversible mental health consequences. The monograph was also published as Child Care and the Growth of Love for public consumption. The central proposition was influential in terms of the effect on the institutional care of children, but highly controversial. There was limited empirical data at the time and no comprehensive theory to account for such a conclusion. Nevertheless, Bowlby's theory sparked considerable interest and controversy in the nature of early relationships and gave a strong impetus to, in the words of Mary Ainsworth, a "great body of research" in what was perceived as an extremely difficult and complex area. Bowlby's work (and Robertson's films) caused a virtual revolution in visiting by parents in hospitals, provision for children's play, educational and social needs in hospital and the use of residential nurseries. Over time, orphanages were abandoned in favour of foster care or more family style homes in most developed countries.

Ten years after the publication of the hypothesis, Ainsworth listed nine concerns that she felt were the chief points of controversy. Ainsworth separated the three dimensions of maternal deprivation into lack of maternal care, distortion of maternal care and discontinuity of maternal care. She analysed the dozens of studies undertaken in the field and concluded that the basic assertions of the maternal deprivation hypothesis were sound, however the controversy continued.

Attachment theory

Following the publication of Maternal Care and Mental Health, Bowlby sought new understanding from such fields as evolutionary biology, ethology, developmental psychology, cognitive science and control systems theory. He drew upon these to formulate the innovative proposition that the mechanisms underlying an infant's tie emerged as a result of evolutionary pressure. He realised that he had to develop a new theory of motivation and behaviour control, built on up-to-date science rather than the outdated psychic energy model espoused by Freud. Bowlby argued that with attachment theory he had made good the "deficiencies of the data and the lack of theory to link alleged cause and effect" in Maternal Care and Mental Health.

The formal origin of attachment theory can be traced to the publication of two 1958 papers: Bowlby's "The Nature of the Child's Tie to his Mother", in which the precursory concepts of "attachment" were introduced, and Harry Harlow's "The Nature of Love", based on the results of experiments which showed, approximately, that infant rhesus monkeys spent more time with and appeared to form an affectional bond with soft, cloth surrogate mothers that offered no food compared to wire surrogate mothers that provided a food source but were less pleasant to touch. Bowlby followed this up with two more papers, "Separation Anxiety" (1960a), and "Grief and Mourning in Infancy and Early Childhood" (1960b). At about the same time, Bowlby's former colleague Mary Ainsworth was completing her extensive observational studies on the nature of infant attachments in Uganda with Bowlby's ethological theories in mind. Attachment theory was finally presented in 1969 in Attachment, the first volume of the Attachment and Loss trilogy. The second and third volumes, Separation: Anxiety and Anger and Loss: Sadness and Depression followed in 1972 and 1980 respectively. Attachment was revised in 1982 to incorporate later research.

Attachment theory came at a time when women were asserting their right to equality and independence, giving mothers new cause for anxiety, as although attachment theory itself is not gender specific, in Western society it was largely mothers who bore the responsibility of early child care. Those with political agendas interpreted the theory for their own purposes and early opposition to attachment theory coalesced around this issue.

Ethology

Bowlby's attention was first drawn to ethology when he read Konrad Lorenz's 1952 publication in draft form (although Lorenz had published much earlier work). Soon after this he encountered the work of Nikolaas Tinbergen and began to collaborate with Robert Hinde. In 1953 Bowlby stated "the time is ripe for a unification of psychoanalytic concepts with those of ethology, and to pursue the rich vein of research which this union suggests". Konrad Lorenz had examined the phenomenon of "imprinting", a behaviour characteristic of some birds and a few mammals which involves rapid learning of recognition and tendency to follow, by a young bird or animal of a conspecific or comparable object.

The learning is possible only within a limited age range, known as a critical period. Bowlby's attachment concepts included the ideas that attachment involves learning from experience during a limited age period and that this influences adult behaviour. He did not apply the imprinting concept in its entirety to human attachment but he did consider that attachment behaviour was best explained as instinctive in nature, stressing the readiness the young child brings to social interactions combined with the effect of experience. Over time it became apparent there were more differences than similarities between attachment theory and imprinting and the analogy was dropped.

Ethologists expressed concern about the adequacy of some of the research on which attachment theory was based, particularly the generalisation to humans from animal studies. Schur, discussing Bowlby's use of ethological concepts (pre-1960) commented that these concepts as used in attachment theory had not kept up with changes in ethology itself.

Ethologists and others writing in the 1960s and 1970s questioned and expanded the types of behaviour used as indications of attachment. For example, crying on separation from a familiar person was suggested as an index of attachment. Observational studies of young children in natural settings also provided behaviours that might be considered to indicate attachment; for example, staying within a predictable distance of the mother without effort on her part and picking up small objects and bringing them to the mother, but usually not to other adults. Although ethologists tended to be in agreement with Bowlby, work like that just described led ethologists to disagree with Bowlby and Ainsworth on some of the details of the child's interactions with its mother and other people and press for further observational data. Ethologists objected to psychologists writing as if there was an "entity which is 'attachment', existing over and above the observable measures."

Robert Hinde expressed concern with the use of the word "attachment" to imply that it was an intervening variable or a hypothesised internal mechanism rather than a data term. He suggested that confusion about the meaning of attachment theory terms "could lead to the 'instinct fallacy' of postulating a mechanism isomorphous with the behaviours, and then using that as an explanation for the behaviour". However, Hinde considered "attachment behaviour system" to be an appropriate term of theory language which did not offer the same problems "because it refers to postulated control systems that determine the relations between different kinds of behaviour."

Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalytical concepts and the earlier work of psychoanalysts also influenced Bowlby's view of attachment. In particular, he was influenced by observations of young children separated from familiar caregivers, as provided during World War II by Anna Freud and her colleague Dorothy Burlingham.

However, Bowlby rejected psychoanalytical explanations for early infant bonds including the psychoanalytic belief that infants' responses relate to their internal fantasy life rather than to real-life events. He also rejected the Freudian and early object relations "drive theory" in which the motivation for attachment derives from gratification of hunger and libidinal drives. He called the latter the "cupboard-love" theory of relationships. In his view this failed to see attachment as a psychological bond in its own right rather than an instinct derived from feeding or sexuality. Thinking in terms of primary attachment and neo-Darwinism, Bowlby identified what he saw as fundamental flaws in psychoanalysis; the overemphasis of internal dangers at the expense of external threat and the picture of the development of personality via linear "phases" with "regression" to fixed points accounting for psychological distress. Instead he posited that several lines of development were possible, the outcome of which depended on the interaction between the organism and the environment. In attachment this would mean that although a developing child has a propensity to form attachments, the nature of those attachments depends on the environment to which the child is exposed.

From an early point in the development of attachment theory, there was criticism of the theory's lack of congruence with the various branches of psychoanalysis. Bowlby's decisions left him open to criticism from well-established thinkers working on problems similar to those he addressed. Bowlby was effectively ostracized from the psychoanalytic community. More recently some psychoanalysts have sought to reconcile the two theories in the form of attachment-based psychotherapy, a therapeutic approach.

Internal working model

Bowlby adopted the important concept of the internal working model of social relationships from the work of the philosopher Kenneth Craik. Craik had noted the adaptiveness of the ability of thought to predict events and stressed the survival value of and natural selection for this ability. According to Craik, prediction occurs when a "small-scale model" consisting of brain events is used to represent not only the external environment, but the individual's own possible actions. This model allows a person to mentally try out alternatives and to use knowledge of the past in responding to the present and future. At about the same time that Bowlby was applying Craik's ideas to the study of attachment, other psychologists were using these concepts in discussion of adult perception and cognition.

Cybernetics

The theory of control systems (cybernetics), developing during the 1930s and '40s, influenced Bowlby's thinking. The young child's need for proximity to the attachment figure was seen as balancing homeostatically with the need for exploration. The actual distance maintained would be greater or less as the balance of needs changed; for example, the approach of a stranger, or an injury, would cause the child to seek proximity when a moment before he had been exploring at a distance.

Cognitive development

Bowlby's reliance on Piaget's theory of cognitive development gave rise to questions about object permanence (the ability to remember an object that is temporarily absent) and its connection to early attachment behaviours. An infant's ability to discriminate strangers and react to the mother's absence seems to occur some months earlier than Piaget suggested would be cognitively possible. More recently, it has been noted that the understanding of mental representation has advanced so much since Bowlby's day that present views can be far more specific than those of Bowlby's time.

Behaviourism

In 1969, Gerwitz discussed how mother and child could provide each other with positive reinforcement experiences through their mutual attention and therefore learn to stay close together. This explanation would make it unnecessary to posit innate human characteristics fostering attachment. Learning theory saw attachment as a remnant of dependency and the quality of attachment as merely a response to the caregiver's cues. Behaviourists saw behaviours such as crying as a random activity that meant nothing until reinforced by a caregiver's response; therefore frequent responses would result in more crying. To attachment theorists, crying is an inborn attachment behaviour to which the caregiver must respond if the infant is to develop emotional security. Conscientious responses produce security which enhances autonomy and results in less crying. Ainsworth's research in Baltimore supported the attachment theorists' view. In the last decade, behaviour analysts have constructed models of attachment based on the importance of contingent relationships. These behaviour analytic models have received some support from research and meta-analytic reviews.

1970s

In the 1970s, problems with viewing attachment as a trait (a stable characteristic of an individual) rather than as a type of behaviour with important organising functions and outcomes, led some authors to the conclusion that attachment behaviours were best understood in terms of their functions in the child's life. This way of thinking saw the secure base concept as central to the logic and coherence of attachment theory and to its status as an organizational construct. Similarly, Thompson pointed out that other features of early parent-child relationships that develop concurrently with attachment security, including negotiating conflict and establishing cooperation, also must be considered in understanding the legacy of early attachments.

As the formulation of attachment theory progressed, critics commented on empirical support for the theory and for the possible alternative explanations for results of empirical research. Some of Bowlby's interpretations of the data reported by James Robertson were eventually rejected by the researcher, who reported data from 13 young children who were cared for in ideal rather than institutional circumstances during separation from their mothers. In the second volume of the trilogy, Separation, published two years later, Bowlby acknowledged that Robertsons foster study had caused him to modify his views on the traumatic consequences of separation in which insufficient weight was given to the influence of skilled care from a familiar substitute. There was also critical discussion of conclusions drawn from clinical and observational work and whether or not they actually supported the tenets of attachment theory. For example, in 1984 Skuse based criticism of a basic tenet of attachment theory on the work of Anna Freud with children from Theresienstadt, who apparently developed relatively normally in spite of serious deprivation during their early years. This discussion concluded from Freud's case and from some other studies of extreme deprivation that there is an excellent prognosis for children with this background, unless there are biological or genetic risk factors.

Bowlby's arguments that even very young babies were social creatures and the primary actors in creating relationships with parents, and Ainsworth's emphasis on the importance and primacy of maternal attunement for psychological development, (a point also argued by Donald Winnicott) took some time to be accepted. Research in the 1970s by Daniel Stern on the concept of attunement between very young infants and caregivers, using micro-analysis of video evidence, added significantly to the understanding of the complexity of infant/caregiver interactions as an integral part of a baby's emotional and social development.

1980s on

Following the argument made in the 1970s that attachment should not be seen as a trait but instead should be regarded as an organising principle with varying behaviours resulting from contextual factors, later research looked at cross-cultural differences in attachment, and concluded that there should be re-evaluation of the assumption that attachment is expressed identically in all humans. Ensuing research showed cultural differences but that the three basic patterns, secure, avoidant and ambivalent, can be found in every culture in which studies have been undertaken, even, for example, where communal sleeping arrangements are the norm.

Selection of the secure attachment pattern is found in the majority of children across those cultures which have been studied. This follows logically from the fact that attachment theory provides for infants to adapt to changes in the environment and select optimal behavioural strategies. How attachment is expressed shows cultural variations which need to be ascertained before studies can be undertaken; for example Gusii infants are greeted with a handshake rather than a hug and securely attached Gusii infants anticipate and seek this contact. There are also differences in the distribution of insecure patterns based on cultural differences in child-rearing practices. The biggest challenge to the notion of the universality of attachment theory came from studies conducted in Japan where the concept of amae plays a prominent role in describing family relationships. Arguments revolved around the appropriateness of the use of the Strange Situation procedure where amae is practiced. Ultimately, however, research tended to confirm the universality hypothesis of attachment theory. Most recently a 2007 study conducted in Sapporo in Japan found attachment distributions consistent with global norms using the six-year Main & Cassidy scoring system for attachment classification.

Critics in the 1990s such as J. R. Harris, Stephen Pinker and Jerome Kagan were generally concerned with the concept of infant determinism (Nature versus nurture) and stressed the possible effects of later experience on personality. Building on the earlier work on temperament of Stella Chess, Kagan rejected almost every assumption on which attachment theory etiology was based, arguing that heredity was far more important than the transient effects of early environment. For example a child with an inherently difficult temperament would not illicit sensitive behavioural responses from a caregiver. The debate spawned considerable research and analysis of data from the growing number of longitudinal studies. Subsequent research has not bourne out Kagan's argument and broadly demonstrates that it is the caregiver's behaviours that form the child's attachment style, although how this style is expressed may differ with temperament. Harris and Pinker put forward the notion that the influence of parents had been much exaggerated and that socialisation took place primarily in peer groups. H. Rudolph Schaffer concluded that parents and peers fulfilled different functions and had distinctive roles in children's development.

Biology of attachment

Attachment theory proposes that the quality of caregiving from at least the primary carer is key to attachment security or insecurity. The body of research supports this view. In addition to evidence from longitudinal studies, research has been undertaken on the biology of attachment using an approach known as psychophysiology. Research has begun to include concepts related to behaviour genetics and to the study of temperament. Generally temperament and attachment constitute separate developmental domains, however aspects of both contribute to a range of interpersonal and intrapersonal developmental outcomes. There is some evidence that like attachment, the physiological mechanisms underlying temperamental differences are tuned by the social environment created by significant caregivers. It has been suggested that types of temperament, may make some individuals susceptible to the stress of unpredictable or hostile relationships with caregivers in the early years. In the absence of available and responsive caregivers it appears that some children are particularly vulnerable to developing attachment disorders.

Psychophysiological research includes measurement of physiological systems correlated with behavioural responses and the way in which individual differences predispose people to certain types of behaviour. In attachment, the two main areas studied have been autonomic responses, such as heart rate or respiration, and the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis during stressful tasks. Infants physiological responses have been measured during the Strange Situation procedure in relation to their main attachment classifications and the various subsets within each classification. A significant proportion of the research has addressed the issue of individual differences in infant disposition (temperament) and the extent to which attachment acts as a moderator of a physiological disposition. Infants who receive low quality maternal caregiving behaviour (MCB) display significantly more fearfulness when presented with unfamiliar stimuli and significantly less sociability compared to infants receiving high MCB, despite comparable temperaments. This indicates that the quality of caregiving, in other words the provision of prompt, contingent and appropriate responsiveness to infant cues, rather than just extremes of deprivation, influences neurological development. It appears the quality of caregiving shapes the development of the neurological systems which regulate stress.

Another method used to ascertain the effects of caregiver behaviour is EEGs to measure asymmetry of left and right frontal lobe activity. For example, in general, infants exhibit left asymmetry during positive affect and right asymmetry during negative affect. Although there are no data directly assessing EEG differences in the prediction of attachment classification, there is evidence that infants of depressed mothers and insecurely attached infants show reduced frontal lobe activity and that insecurely attached infants of depressed mothers show even greater attenuation of left frontal lobe activity.

Another issue is the role of inherited genetic factors in shaping attachments: for example one type of polymorphism of the DRD2 dopamine receptor gene has been linked to anxious attachment and another in the 5HT2A serotonin receptor gene with avoidant attachment. This suggests that the influence of maternal care on attachment security is not the same for all children. One theoretical basis for this is that it makes biological sense for children to vary in their susceptibility to rearing influence.

Practical applications

Child care policies

Social policies concerning the care of children were the driving force in Bowlby's development of attachment theory. The difficulty lies in applying attachment concepts to policy and practice. The impact of attachment theory arises from the emphasis on the importance of the continuity and sensitivity in caregiving relationships rather than a behavioural emphasis on stimulation or reinforcement of child behaviours. In 2008 C.H. Zeanah and colleagues stated, "Supporting early child-parent relationships is an increasingly prominent goal of mental health practitioners, community based service providers and policy makers...Attachment theory and research have generated important findings concerning early child development and spurred the creation of programs to support early child-parent relationships".

Historically attachment theory had significant policy implications in the field of hospitalised or institutionalised infants and children, and for infants and children in poor quality daycare. Controversy remains over whether non-maternal care, particularly in group settings, has deleterious effects on young children social development. It is plain from research, however, that poor quality care carries risks and that the majority of children who experience good quality alternative care cope well although it is difficult to provide good quality, individualised care in group settings.

Attachment theory continues to have implications in residence and contact disputes, and in applications by foster parents to adopt foster children. In the past, particularly in North America, psychoanalysis provided the main theoretical framework. Increasingly attachment theory has come to replace it, thus focusing on the quality of caregiver relationships and the importance of continuity rather than economic well-being or automatic precedence of any one party, such as the biological mother. However, arguments tend to focus on whether children are "attached" or "bonded" to the disputing adults rather than the quality of attachments, although Rutter noted that since 1980, in the UK, family courts have shifted considerably to recognize the complications of attachment relationships. Research indicates that children tend to have security-providing relationships with both parents and often with grandparents or other relatives. Judgements need to take this into account along with the impact of step-families. Attachment theory has been crucial in highlighting the importance of social relationships in dynamic rather than fixed terms.

Attachment research and theory can also inform decisions made in social work and in court processes about foster care and placement. Considering the child’s attachment needs can help determine the level of risk imposed by placement options. Within the field of adoption, the shift from "closed" to "open" adoptions and the importance of the search for biological parents would be expected on the basis of attachment theory and many researchers in the field were strongly influenced by it.

Clinical practice in children

Although attachment theory has become a major scientific theory of socioemotional development with one of the broadest, deepest research lines in modern psychology, attachment theory has, until recently, been less clinically applied than theories with far less empirical support. This may be partly due to lack of attention paid to clinical application by Bowlby himself and partly due to broader meanings of the word 'attachment' used amongst practitioners. It may also be partly due to the mistaken association of attachment theory with the pseudo-scientific interventions misleadingly known as attachment therapy.

Physically abused and neglected children are less likely to develop secure attachments and their insecure classifications tend to persist through pre-school years. Neglect alone is associated with insecure attachment organisations. Markedly elevated rates of disorganised-disorientated attachment have been found in the children of maltreating parents. Studies of severely deprived children in East European orphanages found higher rates of atypical insecure attachment patterns compared to native born or early adopted samples, although 70% of later adopted children did not exhibit marked or severe attachment disorder behaviours.

Prevention and treatment

Main article: Attachment-based therapy (children)In 1988 Bowlby published a series of lectures indicating how attachment theory and research could be used in understanding and treating child and family disorders. His focus was on the parents' internal working models, parenting behaviours and the parents' relationship with the therapeutic intervenor to effect change. Ongoing research has lead to a number of prevention and intervention programmes and individual treatments. These range from individual therapeutic approaches to public health programmes to interventions specifically designed for foster carers. Mainstream prevention programmes and treatment approaches for attachment difficulties or disorders for infants and younger children concentrate on increasing the responsiveness and sensitivity of the caregiver, or if that is not possible, placing the child with a different caregiver. These approaches are mostly in the process of being evaluated. The programmes invariably include a detailed assessment of the attachment status or caregiving responses of the adult caregiver as attachment is a two-way process involving attachment behaviour and caregiver response. Some of these programmes are specifically aimed at foster carers rather than parents, as the attachment behaviours of infants or children with attachment difficulties often do not elicit appropriate caregiver responses.

Reactive attachment disorder and attachment disorder

Main articles: Reactive attachment disorder and Attachment disorderThere is an atypical attachment pattern considered to be an actual disorder, known as reactive attachment disorder or RAD. This is a psychiatric diagnosis (ICD-10 F94.1/2 and DSM-IV-TR 313.89). The essential feature of reactive attachment disorder is markedly disturbed and developmentally inappropriate social relatedness in most contexts that begins before age five years and is associated with gross pathological care. There are two subtypes, one reflecting the disinhibited attachment pattern and the other reflecting the inhibited pattern. RAD denotes a lack of age appropriate attachment behaviours that amount to a clinical disorder rather than a description of insecure or disorganised attachment patterns or styles however problematic those styles may be. RAD has been criticised as being under-researched, poorly understood and, by focussing on the child's aberrant behaviour, failing to recognise the relational aspect of attachment disorders given that children often have multiple attachment relationships and may exhibit disordered behaviour with only one caregiver. It is thought to be rare, despite the popularisation of the term "reactive attachment disorder" on the Web, in connection with the pseudoscientific attachment therapy, for a range of perceived behavioural difficulties in children that are not within DSM or ICD criteria for RAD.

Attachment disorder is an ambiguous term. It may be used to refer to reactive attachment disorder, the only 'official' clinical diagnosis, or the more problematical attachment styles despite the fact that none of these are clinical disorders, or within the field of attachment therapy as a form of invalidated diagnosis. It may also be used to refer to proposed new classification systems put forward by theorists in the field.

Clinical practice in adults and families

Main articles: Attachment-based psychotherapy and Emotionally focused therapyAs attachment theory offers a broad and far-reaching view of human functioning it can enrich a therapist's understanding of patients and the therapeutic relationship rather than dictate a particular form of treatment. There are also forms of psychoanalysis-based therapy for adults within relational psychoanalysis and other approaches which incorporate attachment theory and patterns. In the last decade key concepts of child and adult attachment have become incorporated into existing models of behavioural couple therapy, multidimensional family therapy and couple and family therapy interventions. Specifically attachment centred interventions such as attachment-based family therapy and emotionally focused therapy for couples or families have also been developed.