| Revision as of 08:32, 13 February 2010 view sourceGwillhickers (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers121,353 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 10:40, 13 February 2010 view source Dr Gangrene (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users13,109 editsm clean up, using AWBNext edit → | ||

| Line 106: | Line 106: | ||

| Three months later, Grant's militia in combination with ]'s Navy gunboats, captured two major Confederate fortresses, ], February 6, 1862, on the ] and ], February 15, 1862, on the ]. Fort Henry was taken after 2 hours of continued bombardment by Admiral Foote's Union gunboats. For the first time in the War, there was deep concern in the Confederacy about Union military penetration in the South. By February 8th, Foote's gunboats went as far south threatening ]. <ref>{{cite book |last=McFeely|first=Willam S.|title=Grant: A Biography|pages=97-98|publisher=W.W. Norton & Company|date=1981}}</ref> | Three months later, Grant's militia in combination with ]'s Navy gunboats, captured two major Confederate fortresses, ], February 6, 1862, on the ] and ], February 15, 1862, on the ]. Fort Henry was taken after 2 hours of continued bombardment by Admiral Foote's Union gunboats. For the first time in the War, there was deep concern in the Confederacy about Union military penetration in the South. By February 8th, Foote's gunboats went as far south threatening ]. <ref>{{cite book |last=McFeely|first=Willam S.|title=Grant: A Biography|pages=97-98|publisher=W.W. Norton & Company|date=1981}}</ref> | ||

| On |

On February 14th, taking the initiative Admiral Foote unsuccessfully attacked ] with Union gunboats, and was injured in the battle. Fort Donelson was commanded by Brig Gen. ], Brig. Gen. ], and Brig. Gen. ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Fort Henry|url=http://www.nps.gov/history/hps/abpp/battles/tn001.htm|accessdate=02-03-10}}</ref> On the 15th, General Pillow took the offensive and attacked at one of Grant's divisions headed by Brig. Gen. ] and forced a disorganized retreat eastward on the Nashville road. Grant having heard the battle noise four miles away in conference with Foote road back to take charge. On the 15th, Grant and his three generals, ], ], and ] engaged in a counterattack that broke the Confederate line, closed the Nashville road, and forced the enemy to retreat back into the fort. Pillow and Floyd fled, leaving Buckner in charge of surrender terms. Grant's terms were simple, "no terms except unconditional and immediate surrender." Forced to comply, Buckner relinquished 12,392 Confederate prisoners of war, including himself. Grant's fame increased and he was known thereafter as "Unconditional Surrender".<ref>{{cite book |last=Smith|first=Professor Jean Edward|title=Grant|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Kq1wZ3900xYC&pg=PA159&dq=Grant+takes+Fort+Donelson&cd=2#v=onepage&q=Grant%20takes%20Fort%20Donelson&f=false|pages=156–158|year=2001|accessdate=02-02-10}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=McFeely|first=Willam S.|title=Grant: A Biography|pages=99-101|publisher=W.W. Norton & Company|date=1981}}</ref><ref>Gott, Kendall D., ''Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry—Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862'', Stackpole books, 2003, ISBN 0-8117-0049-6.</ref> | ||

| ====Shiloh==== | ====Shiloh==== | ||

| Line 119: | Line 119: | ||

| ====Vicksburg==== | ====Vicksburg==== | ||

| {{See|Battle of Vicksburg}} | {{See|Battle of Vicksburg}} | ||

| In order for the Union Army in the North to link with the Union Army occupying ] the Confederate fortress on the ] at Vicksburg, |

In order for the Union Army in the North to link with the Union Army occupying ] the Confederate fortress on the ] at Vicksburg, Mississippi had to be taken. General ] supported by Admiral ] had unsuccessfully attempted to take the fortress by the Chickasaw Bluffs on December 29th, 1862. Grant's only chance of success was to attack Vicksburg from the south, as a previous attempt from the north proved unsuccessful. Confederate General ] had captured vasts amounts of supplies from Grant's army earlier on December 20th. In order to attack from the south Grant , in early 1863, marched his troops through a maze of islands and bayous down the west bank of the ].<ref>{{cite book |last=McFeely|first=Willam S.|title=Grant: A Biography|pages=128-132|publisher=W.W. Norton & Company|date=1981}}</ref> | ||

| The experience that Grant had learned from the Fort Donelson campaign using the Union Navy paid off. On April 19th, Porter's gunboats ran the Vickburg gauntlet and allowed Grant's army divisions led by General McClerland and General McPherson to cross the Mississippi River nine miles south of Grand Gulf. Grant then marched up North took the town of Grand Gulf and allowed General Sherman's Army to cross the Mississippi River. Rather |

The experience that Grant had learned from the Fort Donelson campaign using the Union Navy paid off. On April 19th, Porter's gunboats ran the Vickburg gauntlet and allowed Grant's army divisions led by General McClerland and General McPherson to cross the Mississippi River nine miles south of Grand Gulf. Grant then marched up North took the town of Grand Gulf and allowed General Sherman's Army to cross the Mississippi River. Rather than wait for reinforcements from General Banks in ] Grant cut his supply lines and moved his army out of Grand Gulf. Conferderate General ], held up in Jackson, ordered General ] out of Vickburg to attack Grant. Pemberton moved out of Vicksburg and went on to occupy a position on ]. Grant moved swiftly, never giving Jackson and Pemberton an opportunity to concentrate their forces. Gambling without reinforcements from General Banks and directly defying and order from General Halleck to stay at Grand Gulf, Grant ordered McClerland and McPherson to attack Pemberton on Champion Hill. The costly gamble paid off and Pemberton was forced to retreat to Vicksburg. The casualties for the battle were Union 2,457 and Confederate 3,840. <ref>Kennedy, Frances H., ed., ''The Civil War Battlefield Guide'', 2nd ed., Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998, ISBN 0-395-74012-6.</ref>While Grant was attacking Pemberton, General Sherman captured Jackson, Mississippi's capital, and destroyed many supplies.<ref>{{cite book |last=McFeely|first=Willam S.|title=Grant: A Biography|pages=128-132|publisher=W.W. Norton & Company|date=1981}}</ref> | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 176: | Line 176: | ||

| ==Military criticism and controversy== | ==Military criticism and controversy== | ||

| ===War by attrition=== | ===War by attrition=== | ||

| Grant was a rational tactician who viewed the ] Union victory would only come after long and costly battles. Although a master of combat by outmaneuvering his opponent (such as at Vicksburg and in the Overland Campaign against Lee), Grant was not afraid to order direct assaults, often when the Confederates were themselves launching offensives against him. Sadly, these tactics often resulted in staggering casualties for Grant's men, particularly at ] and ], but they wore down the Confederate forces proportionately more and inflicted irreplaceable losses.<ref>{{cite book |last=Keirsey|first=David|last=Choiniere|title=Presidential Temperaments|url=http://keirsey.com/handler.aspx?s=keirsey&f=fourtemps&tab=5&c=grant|date=1992|accessdate=01-24-10}}</ref> Grant's lack of defensive preparations and strategy at ], earlier in 1862, also contributed to higher casualties. Grant was more concerned with his own military plans rather |

Grant was a rational tactician who viewed the ] Union victory would only come after long and costly battles. Although a master of combat by outmaneuvering his opponent (such as at Vicksburg and in the Overland Campaign against Lee), Grant was not afraid to order direct assaults, often when the Confederates were themselves launching offensives against him. Sadly, these tactics often resulted in staggering casualties for Grant's men, particularly at ] and ], but they wore down the Confederate forces proportionately more and inflicted irreplaceable losses.<ref>{{cite book |last=Keirsey|first=David|last=Choiniere|title=Presidential Temperaments|url=http://keirsey.com/handler.aspx?s=keirsey&f=fourtemps&tab=5&c=grant|date=1992|accessdate=01-24-10}}</ref> Grant's lack of defensive preparations and strategy at ], earlier in 1862, also contributed to higher casualties. Grant was more concerned with his own military plans rather than the enemies.<ref>{{cite book |last=Smith Ph.D.|first=Jean Edward|title=Grant|page=185|date=2001}}</ref> | ||

| Many in the North accused Grant as a "butcher", made both by Northern civilians appalled at the staggering number of casualties suffered by Union armies for what appeared to be negligible gains, and by ], Northern ] who either favored the Confederacy or simply wanted an end to the war, even at the cost of recognizing Southern independence. Grant persevered, refusing to withdraw as had his predecessors, and Lincoln, despite public outrage and pressure within the government, stuck by Grant, refusing to replace him.<ref>{{cite book |last=Bonekemper|first=Edward H.|title=A victor, not a butcher: Ulysses S. Grant's overlooked military genius|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=J4Rk7U8TD_QC&pg=PA245&dq=Ulysses+S.+Grant+aquired+the+unfortunate+and+unfair&cd=1#v=onepage&q=&f=false|pages=245=246|date=2004|accessdate=01-24-10}}</ref> | Many in the North accused Grant as a "butcher", made both by Northern civilians appalled at the staggering number of casualties suffered by Union armies for what appeared to be negligible gains, and by ], Northern ] who either favored the Confederacy or simply wanted an end to the war, even at the cost of recognizing Southern independence. Grant persevered, refusing to withdraw as had his predecessors, and Lincoln, despite public outrage and pressure within the government, stuck by Grant, refusing to replace him.<ref>{{cite book |last=Bonekemper|first=Edward H.|title=A victor, not a butcher: Ulysses S. Grant's overlooked military genius|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=J4Rk7U8TD_QC&pg=PA245&dq=Ulysses+S.+Grant+aquired+the+unfortunate+and+unfair&cd=1#v=onepage&q=&f=false|pages=245=246|date=2004|accessdate=01-24-10}}</ref> | ||

| === Drunkeness === | === Drunkeness === | ||

| During the preliminary stages to capturing ] in March 1863, Grant was accused of being drunk by a Union military rival Major-General ]. McClernland had used information gathered by William J. Kounts that Grant was "gloriously drunk" on March 13th. Major-General ] claimed earlier in February that "Grant is a drunkard." and that his wife Julia was always there to keep him from drinking. ''Cincinnati Commercial'' editor, ], railed that "Our whole ] is being wasted by a foolish, drunken, stupid Grant". Out of concern President ] sent ] to keep a watchful eye on Grant's drinking reputation. Ironically, Grant's superior and critic, General in Chief ], became Grant's protector and kept Grant informed about things going on in Washington. Halleck told Grant that, "The eyes and hopes of the whole country are now directed toward your Army." To save Grant from dismissal assistant Adjutant General ], Grant's friend, got Grant to pledge not to touch |

During the preliminary stages to capturing ] in March 1863, Grant was accused of being drunk by a Union military rival Major-General ]. McClernland had used information gathered by William J. Kounts that Grant was "gloriously drunk" on March 13th. Major-General ] claimed earlier in February that "Grant is a drunkard." and that his wife Julia was always there to keep him from drinking. ''Cincinnati Commercial'' editor, ], railed that "Our whole ] is being wasted by a foolish, drunken, stupid Grant". Out of concern President ] sent ] to keep a watchful eye on Grant's drinking reputation. Ironically, Grant's superior and critic, General in Chief ], became Grant's protector and kept Grant informed about things going on in Washington. Halleck told Grant that, "The eyes and hopes of the whole country are now directed toward your Army." To save Grant from dismissal assistant Adjutant General ], Grant's friend, got Grant to pledge not to touch alcohol.<ref>{{cite book |last=Simpson|first=Brooks D.|title=Ulysses S. Grant: triumph over adversity, 1822-1865|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=3nKdimz-axQC&pg=PA176&dq=Ulysses+S.+Grant+Drunkard&cd=2#v=onepage&q=Ulysses%20S.%20Grant%20Drunkard&f=false|pages=176-181|date=2000|accessdate=02-11-10}}</ref> | ||

| ===General Order No. 11 and antisemitism=== | ===General Order No. 11 and antisemitism=== | ||

| Line 264: | Line 264: | ||

| Possibly the greatest achievement of the Grant Administration was the ] in 1871, finally settling the ] dispute between England and the ]. Grant’s able Secretary of State ] had orchestrated many of the events leading up to the treaty. The main purpose of the arbitration treaty was to remedy the damages done to American merchants by three Confederate war ships, ], ], and ] made under ] jurisdiction. These ships had inflicted tremendous damage to U.S. merchant ships during the Civil War with the result that relations between ] and the United States was severely strained.<ref name="Corning 1918 59-84">{{cite book |last=Corning|first=Amos Elwood|title=Hamilton Fish|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=QcNEAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Hamilton+Fish&ei=9H8BS_HtM5i-lAT4g9H4Dg#v=onepage&q=&f=false|pages=59–84|year=1918|accessdate=02-02-10}}</ref> | Possibly the greatest achievement of the Grant Administration was the ] in 1871, finally settling the ] dispute between England and the ]. Grant’s able Secretary of State ] had orchestrated many of the events leading up to the treaty. The main purpose of the arbitration treaty was to remedy the damages done to American merchants by three Confederate war ships, ], ], and ] made under ] jurisdiction. These ships had inflicted tremendous damage to U.S. merchant ships during the Civil War with the result that relations between ] and the United States was severely strained.<ref name="Corning 1918 59-84">{{cite book |last=Corning|first=Amos Elwood|title=Hamilton Fish|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=QcNEAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Hamilton+Fish&ei=9H8BS_HtM5i-lAT4g9H4Dg#v=onepage&q=&f=false|pages=59–84|year=1918|accessdate=02-02-10}}</ref> | ||

| Negotiations began in January 1871 when Britain sent ] to America to meet with Secretary Fish. A joint high commission was created on February 1871 in Washington D.C., consisting of representatives from both the ] and the United States. The commission created a treaty where an international Tribunal would settle the damage amounts and the British admitted regret, rather |

Negotiations began in January 1871 when Britain sent ] to America to meet with Secretary Fish. A joint high commission was created on February 1871 in Washington D.C., consisting of representatives from both the ] and the United States. The commission created a treaty where an international Tribunal would settle the damage amounts and the British admitted regret, rather than fault, over the destructive actions of the Confederate war cruisers. President Grant approved and on May 24, 1871, the Senate ratified the ].<ref name="Corning 1918 59-84"/> At the end of arbitration, on September 9, 1871, the international Tribunal members awarded United States $15,500,000. Historian Amos Elwood Corning noted that the Treaty of Washington and arbitration “''bequeathed to the world a priceless legacy''”.<ref name="Corning 1918 59-84"/> | ||

| In addition to the $15,500,000 arbitration award, the monumental treay settled the following desputes with the ] and Canada: | In addition to the $15,500,000 arbitration award, the monumental treay settled the following desputes with the ] and Canada: | ||

Revision as of 10:40, 13 February 2010

"Ulysses Grant" redirects here. For other uses, see Ulysses Grant (disambiguation).

| Ulysses S. Grant | |

|---|---|

| |

| 18th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1877 | |

| Vice President | Schuyler Colfax (1869–1873) Henry Wilson (1873–1875) None (1875–1877) |

| Preceded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hiram Ulysses Grant (1822-04-27)April 27, 1822 Point Pleasant, Ohio |

| Died | July 23, 1885(1885-07-23) (aged 63) Mount McGregor, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Julia Dent Grant |

| Children | Jesse Grant, Ulysses S. Grant, Jr., Nellie Grant, Frederick Grant |

| Alma mater | United States Military Academy at West Point |

| Occupation | General-in-Chief |

| Signature | |

| Nickname | "Unconditional Surrender" Grant |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Branch/service | Union Army |

| Years of service | 1839–1854, 1861–1869 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | 21st Illinois Infantry Regiment Army of the Tennessee Military Division of the Mississippi Armies of the United States United States Army (postbellum) |

| Battles/wars | Mexican-American War |

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant) (April 27, 1822 – July 23, 1885) was general-in-chief of the Union Army from 1864 to 1869 during the American Civil War and the 18th President of the United States from 1869 to 1877.

The son of an Appalachian Ohio tanner, Grant entered the United States Military Academy at age 17. In 1846, three years after graduating, Grant served as a lieutenant in the Mexican–American War under Winfield Scott and future president Zachary Taylor. After the Mexican-American War concluded in 1848, Grant remained in the Army, but abruptly resigned in 1854. After struggling through the succeeding years as a real estate agent, a laborer, and a county engineer, Grant decided to join the Northern effort in the Civil War.

Appointed brigadier general of volunteers in 1861 by President Abraham Lincoln, Grant claimed the first major Union victories of the war in 1862, capturing Forts Henry and Donelson in Tennessee. He was surprised by a Confederate attack at the Battle of Shiloh; although he emerged victorious, the severe casualties prompted a public outcry. Subsequently, however, Grant's 1863 victory at Vicksburg, following a long campaign with many initial setbacks, and his rescue of the besieged Union army at Chattanooga, established his reputation as Lincoln's most aggressive and successful general. Named lieutenant general and general-in-chief of the Army in 1864, Grant implemented a coordinated strategy of simultaneous attacks aimed at destroying the South's armies and its economy's ability to sustain its forces. In 1865, after mounting a successful war of attrition against his Confederate opponents, he accepted the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House.

Popular due to the Union victory in the war, Grant was elected President of the United States as a Republican in 1868 and re-elected in 1872, the first President to serve two full terms since Andrew Jackson 40 years before. As President, Grant led Reconstruction by signing and enforcing Congressional civil rights legislation. Grant built a powerful, patronage-based Republican Party in the South, straining relations between the North and former Confederates. His administration was marred by scandal, sometimes the product of nepotism; the neologism Grantism was coined to describe political corruption.

Grant left office in 1877 and embarked upon a two-year world tour. Unsuccessful in winning the nomination for a third term in 1880, left destitute by a fraudulent investor, and near the brink of death, Grant wrote his Memoirs, which were enormously successful among veterans, the public, and critics. However, in 1884, Grant learned that he was suffering from terminal throat cancer and, two days after completing his writing, he died at the age of 63. Presidential historians typically rank Grant in the lowest quartile of U.S. presidents for his tolerance of corrupt cabinet members, but in recent years his reputation has improved among some scholars impressed by his support for civil rights for African Americans.

Early life and family

Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio, to Jesse Root Grant (1794–1873), a tanner, and Hannah Simpson Grant (1798–1883), both Pennsylvania natives. At birth, Grant was named Hiram Ulysses. In the fall of 1823, the family moved to the village of Georgetown in Brown County, Ohio.

Grant grew up in the Methodist faith and would eventually attend church in Galena, however, he was not an official member. Grant prayed in private, but was opposed to religious pretentiousness.

At the age of 17, Grant entered the United States Military Academy (USMA) at West Point, New York, after securing a nomination through his U.S. Congressman, Thomas L. Hamer, who erroneously nominated him as "Ulysses S. Grant of Ohio." Grant adopted the form of his new name with middle initial only. Because "U.S." also stands for "Uncle Sam," Grant's nickname became "Sam" among his army colleagues. He graduated from USMA in 1843, ranking 21st in a class of 39. At the academy, he established a reputation as a fearless and expert horseman. Although this made him seem a natural for cavalry, he was assigned to duty as a regimental quartermaster, managing supplies and equipment.

Mexican–American War

Lieutenant Grant served in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) under Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott, where, despite his assignment as a quartermaster, he got close enough to the front lines to see action, participating in the battles of Resaca de la Palma, Palo Alto, Monterrey (where he volunteered to carry a dispatch on horseback through a sniper-lined street), and Veracruz. During one battle, Grant saw Fred Dent, his friend, later to become his brother-in-law, lying in the middle of the battlefield; he had been shot in the leg. Grant ran furiously into the open to rescue Dent; as they were making their way to safety, a Mexican soldier was sneaking up behind Grant, but the Mexican was shot by a fellow U.S. soldier. Grant was twice brevetted for bravery: at Molino del Rey and Chapultepec. He was a remarkably close observer of the war, learning to judge the actions of colonels and generals. In the 1880s, he wrote that the war was unjust, accepting the theory that it was designed to gain land open to slavery. He wrote in his memoirs about the war against Mexico: "I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day, regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation."

Between wars

The Mexican-American War concluded on February 2, 1848.

On August 22, 1848, Grant married Julia Boggs Dent (1826–1902), the daughter of a slave owner. Together, they had four children: Frederick Dent Grant, Ulysses S. "Buck" Grant, Jr. , Ellen Wrenshall "Nellie" Grant, and Jesse Root Grant.

Grant remained in the army and was moved to several different posts. He was sent to Fort Vancouver in the Washington Territory in 1853, where he served as quartermaster of the 4th Infantry Regiment. His wife, eight months pregnant with their second child, could not accompany him because his salary could not support a family on the frontier. In 1854, Grant was promoted to captain, one of only 50 still on active duty, and assigned to command Company F, 4th Infantry, at Fort Humboldt, California. Grant abruptly resigned from the Army with little notice on July 31, 1854, offering no explanation for his decision. Rumors persisted in the Army for years that his commanding officer, Bvt. Lt. Col. Robert C. Buchanan, found him intoxicated on duty as a pay officer and offered him the choice between resignation or court-martial. However, the War Department stated, "Nothing stands against his good name."

At age 32, Grant struggled through seven lean years. From 1854 to 1858, he labored on a family farm near St. Louis, Missouri, using slaves owned by his father-in-law, but it did not prosper. Grant acquired one of those slaves in 1858 (and manumitted him the next year, when the Grants returned to Illinois) and his wife owned four slaves. From 1858–1859, he was a bill collector in St. Louis. Failing at everything, he asked his father for a job, and in 1860 was made an assistant in the leather shop owned by his father in Galena, Illinois. Grant & Perkins sold harnesses, saddles, and other leather goods and purchased hides from farmers in the prosperous Galena area.

Although Grant was not affiliated with any political party, his father-in-law was a prominent Democrat in St. Louis, a fact that lost Grant the job of county engineer in 1859. In 1856, he voted for Democrat James Buchanan for president to avert secession and because "I knew Frémont" (the Republican candidate). In 1860, he favored Democrat Stephen A. Douglas but did not vote. In 1864, he allowed his political sponsor, Congressman Elihu B. Washburne, to use his private letters as campaign literature for Abraham Lincoln and the Union Party, which combined both Republicans and War Democrats. Grant announced his affiliation as a Republican in 1868, after years of apoliticism.

Civil War

Western Theater: 1861–63

On April 13, 1861, Union Fort Sumner was surrendered to the Confederate forces. Two days later on April 15th, President Abraham Lincoln put out a call for 75,000 militia volunteers. Grant helped recruit a company of volunteers and accompanied it to Springfield, the capital of Illinois. Grant accepted a position offered by Illinois Governor Richard Yates to recruit and train volunteers, which he accomplished with efficiency. Grant pressed for a field command; Yates, with the support of Congressman Elihu B. Washburne, appointed him a colonel in the Illinois militia and gave him command of the undisciplined and rebellious 21st Illinois Infantry on June 17.

On July 31, 1861, Grant was appointed brigadier general of the militia volunteers by Lincoln, with the continued support of Congressman Elihu Washburne. On September 1, Grant was selected by Western Theater commander Major General John C. Frémont to command the critical District of Southeast Missouri. Grant's headquarters were moved to Cairo, Illinois.

Battles of Belmont, Henry, and Donelson

Further information: Battle of Belmont, Battle of Fort Henry, and Battle of Fort Donelson

On November 6, 1861, Grant's first major strategic act of the war was to take the initiative in seizing the Ohio River town of Paducah, Kentucky, immediately after the Confederates violated the state's neutrality by occupying Columbus. He fought his first battle, a temporary victory that ended in defeat, against Confederate Brig. Gen. Gideon J. Pillow, at Belmont, Missouri, on November 7, 1861. Grant's army initially captured Fort Belmont, but then was repulsed back to Cairo after Pillow had received reinforcements from General Leonidas Polk. Grant was the last off of the battlefield and escaped with his life. It was later learned that a Confederate soldier from Polk's army declined an opportunity to shoot Grant who was just 50 yards away.

Three months later, Grant's militia in combination with Andrew H. Foote's Navy gunboats, captured two major Confederate fortresses, Fort Henry, February 6, 1862, on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson, February 15, 1862, on the Cumberland River. Fort Henry was taken after 2 hours of continued bombardment by Admiral Foote's Union gunboats. For the first time in the War, there was deep concern in the Confederacy about Union military penetration in the South. By February 8th, Foote's gunboats went as far south threatening Florence, Alabama.

On February 14th, taking the initiative Admiral Foote unsuccessfully attacked Fort Donelson with Union gunboats, and was injured in the battle. Fort Donelson was commanded by Brig Gen. John B. Floyd, Brig. Gen. Gideon J. Pillow, and Brig. Gen. Simon B. Buckner. On the 15th, General Pillow took the offensive and attacked at one of Grant's divisions headed by Brig. Gen. John A. McClernand and forced a disorganized retreat eastward on the Nashville road. Grant having heard the battle noise four miles away in conference with Foote road back to take charge. On the 15th, Grant and his three generals, Lew Wallace, John A. McClernand, and Charles S. Smith engaged in a counterattack that broke the Confederate line, closed the Nashville road, and forced the enemy to retreat back into the fort. Pillow and Floyd fled, leaving Buckner in charge of surrender terms. Grant's terms were simple, "no terms except unconditional and immediate surrender." Forced to comply, Buckner relinquished 12,392 Confederate prisoners of war, including himself. Grant's fame increased and he was known thereafter as "Unconditional Surrender".

Shiloh

Further information: Battle of Shiloh

After Fort Donelson, Grant's headquarters had been moved from Cairo, Illinois to Savannah, Tennessee and five divisions of his army were bivouacked seven miles south at Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River. No trenches or defensive preparations had been made since Grant did not believe the Confederate Army, located at Corinth, Mississippi, was about to attack. The senior officer at Pittsburg Landing was the sharp-eyed, red-bearded, William T. Sherman. Grant's other officer Lew Wallace had one division five miles upriver at Crumps Landing. Grant was completely unprepared and unaware when the Confederate army savagely attacked at Pittsburgh Landing with 44,699 troops early in the morning on April 6th. The Army of the Mississippi was led by Albert S. Johnson and Pierre G.T. Beauregard and the irascible Braxton Bragg.

The costly battle took place in fields and woods between the Shiloh meetinghouse and the Tennessee River. The violence of the Confederate assault sent the Union forces reeling back towards to the Tennessee River while Sherman managed to hold his troops together. Grant, who was 10 miles North in Savannah, wounded after being pinned by a fallen horse, did not respond until the battle noise grew louder and more consistent. Finally realizing the Confederates were attacking Grant hastened to Pittsburg Landing and was able to stabilize the Union line. The Union left, under Brig. Gen. Benjamin Prentiss and Brig. Gen. W. H. L. Wallace withstood Confederate assaults, in an area known as the "Hornet's Nest" for seven crucial hours before being forced to yield ground towards the Tennessee River. Union reinforcements arrived later in the evening from Brig. Gen. Don Carlos Buell. Lew Wallace's division, having been lost trying to find the battle, finally arrived at Pittsburgh Landing. During the ferocious battle Confederate General Albert S. Johnson was killed and Beauregard assumed control of the army.

The following morning, April 7th, along with Buell's reinforcements and the lost Lew Wallace's division the Union Army led by Grant rallied and mounted a determined counter attack. The Confederate Army, not expecting such an energetic combined Union offensive, was greatly disorganized. Beauregard realized his armies' peril and ordered a retreat back to their fortified stronghold at Corinth later in the evening. The Union Army reclaimed their grizzly battlefield at Shiloh and were satisfied to regain Grant's camp. The Union troops made an exhausted bivouac among the dead. The victory at Shiloh came at a heavy price; 13,047 for the Union army and 10,699 for Confederate army. Shiloh's awesome toll of men killed, wounded, or missing brought a shocking realization the war would not end quickly.

Vicksburg

Further information: Battle of VicksburgIn order for the Union Army in the North to link with the Union Army occupying New Orleans the Confederate fortress on the Chickasaw Bluffs at Vicksburg, Mississippi had to be taken. General William T. Sherman supported by Admiral David D. Porter had unsuccessfully attempted to take the fortress by the Chickasaw Bluffs on December 29th, 1862. Grant's only chance of success was to attack Vicksburg from the south, as a previous attempt from the north proved unsuccessful. Confederate General Earl Van Dorn had captured vasts amounts of supplies from Grant's army earlier on December 20th. In order to attack from the south Grant , in early 1863, marched his troops through a maze of islands and bayous down the west bank of the Mississippi River.

The experience that Grant had learned from the Fort Donelson campaign using the Union Navy paid off. On April 19th, Porter's gunboats ran the Vickburg gauntlet and allowed Grant's army divisions led by General McClerland and General McPherson to cross the Mississippi River nine miles south of Grand Gulf. Grant then marched up North took the town of Grand Gulf and allowed General Sherman's Army to cross the Mississippi River. Rather than wait for reinforcements from General Banks in Saint Louis Grant cut his supply lines and moved his army out of Grand Gulf. Conferderate General Joseph E. Johnson, held up in Jackson, ordered General John C. Pemberton out of Vickburg to attack Grant. Pemberton moved out of Vicksburg and went on to occupy a position on Champion Hill. Grant moved swiftly, never giving Jackson and Pemberton an opportunity to concentrate their forces. Gambling without reinforcements from General Banks and directly defying and order from General Halleck to stay at Grand Gulf, Grant ordered McClerland and McPherson to attack Pemberton on Champion Hill. The costly gamble paid off and Pemberton was forced to retreat to Vicksburg. The casualties for the battle were Union 2,457 and Confederate 3,840. While Grant was attacking Pemberton, General Sherman captured Jackson, Mississippi's capital, and destroyed many supplies.

Pemberton was bottled up in Vicksburg. His superior, General Johnson, had told Pemberton to move out of Vicksburg or surrender to Grant. Pemberton had refused Johnson's orders and decided to hold out in Vicksburg as long as possible. Even though Vicksburg was protected by skillfully erected earthworks, Grant ordered a hasty assault that ended in failure and gruesome losses. A second assault was made that ended in similar results. Finding that assaults against the impregnable breastworks were futile, he settled in for a six-week siege. Cut off and with no possibility of relief, Pemberton, forced to accept Grant's terms, surrendered Vicksburg on July 4, 1863. It was a devastating defeat for the Southern cause, effectively splitting the Confederacy in two, and, in conjunction with the Union victory at Gettysburg the previous day, is widely considered the turning point of the war. For this victory, President Lincoln promoted Grant to the rank of major general in the regular army, effective July 4.

Chattanooga

Further information: Battle of ChattanoogaAfter the Battle of Chickamauga Union Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans and his Army of the Cumberland retreated to Chattanooga, Tennessee. Confederate Braxton Bragg followed to Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, surrounding the Federals on three sides and besieging them. On October 17, to deal with this crisis, Grant was placed in command of the sweeping, newly-created Military Division of the Mississippi; this command placed Grant in overall charge of the previously independent Departments of the Ohio, the Cumberland (embracing Chattanooga), and the Tennessee. In taking this new command, Grant chose a version of the War Department's order that relieved Rosecrans from command of the Department of the Cumberland and replaced him with Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas. Sherman succeeded Grant in charge of the Department of the Tennessee.

Grant went to Chattanooga personally to take charge of the situation. Although there were some initial tensions between Grant and Thomas, the two commanders eventually worked well together. Devising a plan known as the "Cracker Line," Thomas's chief engineer, William F. "Baldy" Smith opened a new supply route to Chattanooga, helping to feed the starving men and animals of the Union army. Upon reprovisioning and reinforcement by elements of Sherman's Army of the Tennessee and troops from the Army of the Potomac under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, the morale of Union troops lifted. In late November, Grant went on the offensive.

The Battles for Chattanooga started out with Hooker's capture of Lookout Mountain on November 24 and with Sherman's failed attack on the Confederate right the following day. He occupied the wrong hill and then committed only a fraction of his force against the true objective, allowing them to be repulsed by one Confederate division. In response, Grant ordered Thomas to launch a demonstration on the center, which could draw defenders away from Sherman. Thomas's men made an unexpected but spectacular charge straight up Missionary Ridge and broke the fortified center of the Confederate line. Grant was initially angry at Thomas that his orders for a demonstration were exceeded, but the assaulting wave sent the Confederates into a head-long retreat, opening the way for the Union to invade Atlanta, Georgia, and the heart of the Confederacy. According to Hooker, Grant said afterward, "Damn the battle! I had nothing to do with it." Casualties after the battle were 5,824 for the Union and 6,667 for Confederate armies, respectively.

Eastern Theater: 1864-1865

President Abraham Lincoln, impressed by Grant's willingness to fight and ability to win, appointed him lieutenant general in the regular army—a rank not awarded since George Washington (or Winfield Scott's brevet appointment), recently re-authorized by the U.S. Congress with Grant in mind—on March 2, 1864. On March 12, Grant became general-in-chief of all the armies of the United States. Following this Grant placed Major General William T. Sherman in immediate command of all forces in the West and moved his headquarters to Virginia, where he turned his attention to the long-frustrated Union effort to destroy Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

President Lincoln and Grant both understood that in order win the American Civil War the Army of Northern Virginia had to be defeated. Following Lincoln's military suggestions, Grant devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the heart of the Confederacy from multiple directions: Grant, George G. Meade, and Benjamin Franklin Butler against Lee near Richmond; Franz Sigel in the Shenandoah Valley; Sherman to invade Georgia, defeat Joseph E. Johnston, and capture Atlanta; George Crook and William W. Averell to operate against railroad supply lines in West Virginia; and Nathaniel Banks to capture Mobile, Alabama. Under President Lincoln's supervision and guidance, Grant was the first general to attempt such a coordinated strategy and the first to understand the concepts of total war, in which the destruction of an enemy's economic infrastructure that supplied its armies was as important as tactical victories on the battlefield.

Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign was the military thrust needed by the Union to defeat the Confederacy; it pitted Grant against Robert E. Lee. It began on May 4, 1864, when the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River, marching into an area of scrubby undergrowth and second growth trees known as the Wilderness. It was such difficult terrain that the Army of Northern Virginia was able to use it to prevent Grant from fully exploiting his numerical advantage.

The Battle of the Wilderness was a stubborn, bloody two-day fight, resulting in advantage to neither side, but with heavy casualties to both. After similar battles in Virginia against Lee, all of Grant's predecessors had retreated from the field. Grant ignored the setback and ordered an advance around Lee's flank to the southeast, which lifted the morale of his army. Grant's strategy was not just to win individual battles, it was to fight constant engagements to wear down and destroy Lee's army. Casualties for the battle were 17,666 for the Union and 11,125 for the Confederate armies, respectively.

Sigel's Valley Campaigns and Butler's Bermuda Hundred Campaign both failed. Lee was able to reinforce with troops used to defend against these assaults.

The campaign continued. Confederate troops beat the Union to Spotsylvania, Virginia, where, on May 8, the fighting resumed. The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House lasted 14 days. On May 11, Grant wrote a famous dispatch containing the line "I propose to fight it out along this line if it takes all summer". These words summed up his attitude about the fighting, and the next day, May 12, he ordered a massive assault by Hancock's 2nd Corps that broke and briefly captured Lee's second line of defense, and took approximately a total of 3,000 prisoners. There were 12,000 Confederate casualties to the Union's 18,000. In spite of mounting Union casualties, the contest's dynamics changed in Grant's favor. Most of Lee's great victories in earlier years had been won on the offensive, employing surprise movements and fierce assaults. Now, he was forced to continually fight on the defensive without a chance to regroup or replenish against an opponent that was well supplied and had superior numbers.

The next major battle, however, demonstrated the power of a well-prepared defense. Cold Harbor was one of Grant's most controversial battles, in which he launched on June 3 a massive three-corps assault without adequate reconnaissance on a well-fortified defensive line, resulting in horrific casualties, 12,737 for Union and 4,595 for the Confederate troops, respectively. The Union Army suffered a staggering 3 times higher casualty rate then the Confederate Army at Cold Harbor. But Grant moved on and kept up the pressure. He stole a march on Lee, when Union engineers had stealthfully constructed a pontoon bridge, allowing the Army of the Potomac to move southward across the James River on June 15, 1864.

During the Overland Campaign Grant had a reputation of a determined fighter after Abraham Lincoln's famous order, "Hold on with a bull-dog grip, and chew and choke as much as possible." The term accurately captures his tenacity, but it oversimplifies his considerable strategic and tactical capabilities.

Petersburg and Appomattox

After successfully crossing the James River, arriving at Petersburg, Virginia, Grant should have captured the rail junction city, but he failed because of the excessively cautious actions of his subordinate William F. Smith. Over the next three days, a number of Union assaults to take the city were launched. All failed, however, and finally on June 18, Lee's veterans arrived. Faced with fully manned trenches in his front, Grant was left with no alternative but to settle down to the Siege of Petersburg.

As the summer drew on and with Grant's and Sherman's armies stalled, respectively in Virginia and Georgia, politics took center stage. There was a presidential election in the fall, and the citizens of the North had difficulty seeing any progress in the war effort. To make matters worse for Abraham Lincoln, Lee detached a small army under the command of Lieutenant General Jubal A. Early, hoping it would force Grant to disengage forces to pursue him. Early invaded north through the Shenandoah Valley and reached the outskirts of Washington, D.C.. Although unable to take the city, Early embarrassed the Administration simply by threatening its inhabitants, making Abraham Lincoln's re-election prospects even bleaker.

In early September, the efforts of Grant's coordinated strategy finally bore fruit. First, Sherman took Atlanta. Then, Grant dispatched Philip Sheridan to the Shenandoah Valley to deal with Early. It became clear to the people of the North that the war was being won, and Lincoln was re-elected by a wide margin. Later in November, Sherman began his March to the Sea. Sheridan and Sherman both followed Grant's strategy of total war by destroying the economic infrastructures of the Valley and a large swath of Georgia and the Carolinas.

In March 1865, Grant invited Lincoln to visit his headquarters at City Point, Virginia. By coincidence, Sherman (then campaigning in North Carolina) happened to visit City Point at the same time. This allowed for the war's only three-way meeting of Lincoln, Grant, and Sherman, which was memorialized in G.P.A. Healy's famous painting The Peacemakers. At the beginning of April, Grant's relentless pressure finally forced Lee to evacuate Richmond, and after a nine-day retreat, Lee surrendered his army at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. There, Grant offered generous terms that did much to ease the tensions between the armies and preserve some semblance of Southern pride, which would be needed to reconcile the warring sides. Within a few weeks, the American Civil War was effectively over; minor actions would continue until Kirby Smith surrendered his forces in the Trans-Mississippi Department on June 2, 1865.

Lincoln assassination

On April 14, 1865 tragedy struck the nation when Abraham Lincoln was assassinated at Ford's Theater. Grant at first wanted vengeance on the South, however, he was told by General Edward O.C. Ord that the assassination was not a widespread conspiracy. Grant had the sad honor of serving as a pallbearer at the funeral on April 19th, 1865. Grant stood at attention throughout the entire funeral in front of Lincoln's catafalque and was often moved to crying. Lincoln was Grant's greatest champion, friend, and military advisor. Lincoln had been quoted after the massive losses at Shiloh as saying, "I can't spare this man. He fights." It was a two-sentence description that completely caught the essence of Ulysses S. Grant.

Final promotion

After the war, on July 25, 1866, Congress authorized the newly created rank of General of the Army of the United States, the equivalent of a full (four-star) general in the modern United States Army. Grant was appointed as such by President Andrew Johnson on the same day.

Military criticism and controversy

War by attrition

Grant was a rational tactician who viewed the Civil War Union victory would only come after long and costly battles. Although a master of combat by outmaneuvering his opponent (such as at Vicksburg and in the Overland Campaign against Lee), Grant was not afraid to order direct assaults, often when the Confederates were themselves launching offensives against him. Sadly, these tactics often resulted in staggering casualties for Grant's men, particularly at Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor, but they wore down the Confederate forces proportionately more and inflicted irreplaceable losses. Grant's lack of defensive preparations and strategy at Shiloh, earlier in 1862, also contributed to higher casualties. Grant was more concerned with his own military plans rather than the enemies.

Many in the North accused Grant as a "butcher", made both by Northern civilians appalled at the staggering number of casualties suffered by Union armies for what appeared to be negligible gains, and by Copperheads, Northern Democrats who either favored the Confederacy or simply wanted an end to the war, even at the cost of recognizing Southern independence. Grant persevered, refusing to withdraw as had his predecessors, and Lincoln, despite public outrage and pressure within the government, stuck by Grant, refusing to replace him.

Drunkeness

During the preliminary stages to capturing Vicksburg in March 1863, Grant was accused of being drunk by a Union military rival Major-General John A. McClernand. McClernland had used information gathered by William J. Kounts that Grant was "gloriously drunk" on March 13th. Major-General Charles S. Hamilton claimed earlier in February that "Grant is a drunkard." and that his wife Julia was always there to keep him from drinking. Cincinnati Commercial editor, Murat Halstead, railed that "Our whole Army of the Mississippi is being wasted by a foolish, drunken, stupid Grant". Out of concern President Abraham Lincoln sent Charles A. Dana to keep a watchful eye on Grant's drinking reputation. Ironically, Grant's superior and critic, General in Chief Henry W. Halleck, became Grant's protector and kept Grant informed about things going on in Washington. Halleck told Grant that, "The eyes and hopes of the whole country are now directed toward your Army." To save Grant from dismissal assistant Adjutant General John A. Rawlins, Grant's friend, got Grant to pledge not to touch alcohol.

General Order No. 11 and antisemitism

Main article: General Order No. 11 (1862)Allegations of antisemitism -- "a blot on Grant's reputation" -- arose in the wake of the infamous General Order No. 11, issued by Grant in Oxford, Mississippi, on December 17, 1862, during the Vicksburg Campaign. The order stated in part:

The Jews, as a class, violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department, and also Department orders, are hereby expelled from the Department (comprising areas of Tennessee, Mississippi, and Kentucky).

The New York Times denounced the order as "humiliating" and a "revival of the spirit of the medieval ages." Its editorial column called for the "utter reprobation" of Grant's order. After protest from Jewish leaders, the order was rescinded by President Lincoln on January 3, 1863. Though Grant initially maintained that a staff officer issued it in his name, it was suggested by General James H. Wilson that Grant may have issued the order in order to strike indirectly at the "lot of relatives who were always trying to use him" (for example his father Jesse Grant who was in business with Jewish traders), and perhaps struck instead at what he maliciously saw as their counterpart — opportunistic traders who were Jewish. Bertram Korn suggests the order was part of a consistent pattern. "This was not the first discriminatory order had signed he was firmly convinced of the Jews' guilt and was eager to use any means of ridding himself of them." During the campaign of 1868, Grant admitted the order was his, but maintained, "It would never have been issued if it had not been telegraphed the moment it were penned, and without reflection."

The order, ostensibly in response to illegal Southern cotton smuggling, has been described by one modern historian as "the most blatant official episode of anti-Semitism in nineteenth-century American history."

Antisemitism became an issue during the 1868 presidential campaign. Though Jewish opinion was mixed, Grant's determination to "woo" Jewish voters ultimately resulted in his capturing the majority of that vote, though "Grant did lose some Jewish votes as a result of" the order. Grant appointed more Jewish persons to public office than any president before him. Although Grant's order was anti-Jewish, Grant had many Jewish friends. One such friend was Joseph Seligman, whom Grant offered the position as Secretary of the Treasury, which Seligman declined. Seligman had helped finance the Union war effort by obtaining European capital.

1868 presidential campaign

As commanding general of the army, Grant had a difficult relationship with President Andrew Johnson, a Southern Democrat, who preferred a moderate approach to relations with the South. Johnson tried to use Grant to defeat the Radical Republicans by making Grant the Secretary of War in place of Edwin M. Stanton, whom he could not remove without the approval of Congress under the Tenure of Office Act. Grant refused but kept his military command. This made him a hero to the Radical Republicans, who gave him the Republican nomination for president in 1868. He was chosen as the Republican presidential candidate at the 1868 Republican National Convention in Chicago; he faced no significant opposition. In his letter of acceptance to the party, Grant concluded with "Let us have peace," which became his campaign slogan. In the general election of that year, Grant won against former New York Governor Horatio Seymour with a lead of 300,000 votes out of a total of 5,716,082 votes cast. However, Grant commanded an Electoral College landslide, receiving 214 votes to Seymour's 80. When he assumed the presidency, Grant had never before held elected office and, at the age of 46, was the youngest person yet elected president.

Presidency 1869–1877

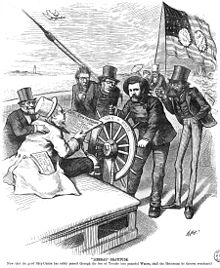

Main article: Ulysses S. Grant presidential administrationThe second President from Ohio, Grant was elected the 18th President of the United States in 1868, and was re-elected to the office in 1872. Grant served as President from March 4, 1869, to March 4, 1877. In his re-election campaign, Grant benefited from the loyal support of Harper's Weekly political cartoonist Thomas Nast and later sent Nast a deluxe edition of Grant's autobiography when it was finished. Grant's notable accomplishments as President include the enforcement of Civil Rights to African Americans, the Treaty of Washington in 1871, and the Resumption of Specie Act in 1875. Grant's reputation as President suffered from scandals caused by many corrupt appointees and personal associates and for the ruined economy caused by the Panic of 1873.

Domestic policies

Reconstruction

Grant presided over the last half of Reconstruction. In the late 1870s, he watched as the Democrats (called Redeemers) took the control of every state away from his Republican coalition. When urgent telegrams from state leaders begged for help to put down the waves of violence by paramilitary groups surrounding elections, Grant and his Attorney General replied that "the whole public is tired of these annual autumnal outbreaks in the South," saying that state militias should handle the problems, not the Army.

He supported amnesty for former Confederates and signed the Amnesty Act of 1872 to further this. He favored a limited number of troops to be stationed in the South—sufficient numbers to protect Southern African Americans, suppress the violent tactics of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), and prop up Republican governors, but not so many as to create resentment in the general population. Grant confronted a Northern public tired of committing to the long war in the South, violent paramilitary organizations in the late 1870s, and a factional Republican Party.

Civil and human rights

A distinguishing characteristic in the Grant Presidency was Grant's concern with the plight of African Americans and native Indian tribes, in addition to civil rights for all Americans. Grant's 1868 campaign slogan, "Let us have peace," defined his motivation and assured his success. As president for two terms, Grant made many advances in both civil and human rights. In 1869 and 1871, Grant signed bills promoting voting rights and prosecuting Klan leaders. He won passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave freedmen the vote, and the Ku Klux Klan Act, which empowered the president "to arrest and break up disguised night marauders."

Grant continued to fight for African Americans civil rights when he pressed for the former slaves to be "possessed of the civil rights which citizenship should carry with it." However, by 1874 a new wave of paramilitary organizations arose in the Deep South. The Red Shirts and White League, that conducted insurgency in Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Louisiana, operated openly and were better organized than the Ku Klux Klan had been. They aimed to turn Republicans out of office, suppress the black vote, and disrupt elections. In response to the renewed violent outbreaks against African Americans Grant was the first President to sign a congressional civil rights act. The law was titled the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which entitled equal treatment in public accommodations and jury selection.

Grant's attempts to provide justice to Native Americans marked a radical reversal of what had long been the government's policy: "Wars of extermination... are demoralizing and wicked," he told Congress. The president lobbied, though not always successfully, to preserve Native American lands from encroachment by the westward advance of pioneers.

Panic of 1873

Prior to the Panic of 1873 the U.S. economy was in good standing. Eight years after the Civil War had seen the construction of thousands of miles of railroads, thousands of factories opened, and a strong stock market. Even the South experienced a boom in agriculture. However, all of this growth was done on borrowed money by many banks in the United States having over speculated in the Railroad industry by as much as $20,000,000 in loans ($371,212,068.97 CPI for year 2008).

Initially, the Panic of 1873 started when the stock market in Vienna, Austria crashed, in June 1873. Unsettled markets soon spread to Berlin, Germany and throughout Europe. Three months later the Panic spread to the United States when two major banks, the New York Warehouse & Security Company (September 17) and Jay Cooke & Company (September 18) went bankrupt. The ensuing depression lasted 5 years in the United States, ruined thousands of businesses, depressed daily wages by 25% from 1873 to 1876, and brought the unemployment rate up to an extremely high 14%. It would take decades before wages would rise to pre-1873 levels. In Boston, soup line kitchens run by Overseers of the Poor doubled in overcrowded city tenements.

The Grant Administration, ineptly, totally caught off-guard, only responded to the Panic after the two U.S. banks crashed. From October, 1873 to January 4, 1874 Secretary of Treasury William A. Richardson, with permission from Grant, printed and reissued a total of $26,000,000 greenbacks to the public in order to make up for lost revenue in the Treasury. Although this action inflated the money supply and helped curb the negative effects of the Panic it did nothing to produce the confidence needed to stimulate the economy. There was also question as to the legality of such actions by the Secretary from Senator John Sherman. Senator George S. Boutwell, the previous Secretary of Treasury believed Richardson's actions were legal. The Grant Administration was also culpable for creating unsettled markets, prior to the Panic, through a monetary stringency policy, after Secretary Boutwell had sold more gold then bonds, giving businesses less currency to invest. Eventually, the Panic of 1873 ran its own course in spite of the limited efforts and stringent monetary policy from the Grant Administration.

Veto on inflationary bill

The rapidly accelarated industrial growth in post Civil War America and throughout the world came to a colossal crash with the Panic of 1873. Many banks over extended their loans and as a result went bankrupt causing a general panic throughout the nation. Secretary of Treasury William A. Richardson, in an attempt put capital into a stringent monetary economy, released $26,000,000 greenbacks. Congress, in 1874, debated the inflationary policy to stimulate the economy and passed the Inflation Bill of 1874 that would release an additional $18,000,000 greenbacks. Many farmers and working men in the South West were anticipating Grant to sign the bill in order to get the needed greenbacks to continue business. Eastern bankers favored a veto because their reliance on bonds and foreign investors. On April 22, 1874 Grant unexpectedly vetoed the bill, against the popular strategy of the Republican Party, on the grounds that it would destroy the credit of the nation. Initially Grant had favored the bill, but decided to veto after evaluating his own reasons for wanting to pass the bill. Although Grant vetoed the bill on strong economic grounds, it may have created the needed economic confidence in the South West.

Foreign policies

Santo Domingo

Although a small island in the Atlantic Ocean, Santo Domingo, now Haiti, was the source of bitter political discussion and controversy during Grant's first term in office. Grant wanted to annex the island to allow Freedmen, oppressed in the United States, to work, and to force Brazil to abandon slavery. Senator Charles Sumner was opposed to annexation because it would reduce the amount of autonomous nations run by Africans in the western hemisphere. Also disputed was the unscrupulous annexation process under the supervision of Grant's private secretary Orville E. Babcock. The annexation treaty was defeated by the Senate in 1871, however, it led to unending political emnity between Senator Sumner and Grant.

Treaty of Washington

Possibly the greatest achievement of the Grant Administration was the Treaty of Washington in 1871, finally settling the Alabama Claims dispute between England and the United States. Grant’s able Secretary of State Hamilton Fish had orchestrated many of the events leading up to the treaty. The main purpose of the arbitration treaty was to remedy the damages done to American merchants by three Confederate war ships, CSS Florida, CSS Alabama, and CSS Shenandoah made under British jurisdiction. These ships had inflicted tremendous damage to U.S. merchant ships during the Civil War with the result that relations between Britain and the United States was severely strained.

Negotiations began in January 1871 when Britain sent Sir John Rose to America to meet with Secretary Fish. A joint high commission was created on February 1871 in Washington D.C., consisting of representatives from both the United Kingdom and the United States. The commission created a treaty where an international Tribunal would settle the damage amounts and the British admitted regret, rather than fault, over the destructive actions of the Confederate war cruisers. President Grant approved and on May 24, 1871, the Senate ratified the Treaty of Washington. At the end of arbitration, on September 9, 1871, the international Tribunal members awarded United States $15,500,000. Historian Amos Elwood Corning noted that the Treaty of Washington and arbitration “bequeathed to the world a priceless legacy”.

In addition to the $15,500,000 arbitration award, the monumental treay settled the following desputes with the United Kingdom and Canada:

- Ended immediate threat of war with the United Kingdom.

- Settled border dispute between U.S. and Canada.

- Settled disputes over fishing rights in the North Pacific.

The treaty triggered a movement for countries to seek alternatives to declaring war through arbitration and the codification of international law. These principles would be the motivating influences for further peace keeping institutions such as the Hague Conventions, the League of Nations, the World Court, and eventually the United Nations. The renowned scholar in international law, John Bassett Moorein, hailed the Treaty of Washington as "the greatest treaty of actual and immediate arbitration the world has ever seen."

Virginius incident

On October 31, 1873, an independent American steamer, Virginius, carrying war materials and men to aid the Cuban insurrection was intercepted and held captive in Santiago by a Spanish warship. Virginius was flying the United States flag and had an American registry. 53 of the passengers and crew, eight being United States citizens, were held prisoners and summarily were executed. The immediate impact of these events was an outcry for war with Spain in the United States. Many prominent men such as William M. Evarts, Henry Ward Beecher, and even Vice President Henry Wilson made impassioned speeches to go to war with Spain.

Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, although outraged over the incident kept a cool demeanor in the crisis. Upon investigating the incident Fish found out there was question over whether Virginius had the right to bear the United States flag. Fish informed Daniel Stickels, the U.S. Spanish ambassador, that reparations were demanded by Spain for this act of "peculiar brutality". The Spanish Rupublic's President, Emilio Castelar, expressed profound regret for the tragedy and was willing to make reparations through arbitration.

Fish finally met with the Spanish Ambassador to the United States, Senor Poly y Bernabe, in Washington D.C. and negotiated reparations. With President Grant's approval Spain was to surrender Virginius, make indemnity with the American slain surviving families, and salute the American flag. Spain made good on the reparations with the United States with the exception of saluting the American flag. U.S. Attorney General, George H. Williams, said that saluting the American flag was not necessary since Virginius, at the time of the incident, was not entitled to carry the flag or to have an American registry.

Scandals

Main article: Ulysses S. Grant presidential administration scandalsGrant's inability to establish personal accountability among his subordinates and cabinet members led to many scandals during his administration. Grant, often, would vigorously attack when critics complained, being very protective and defensive of his subordinates. Grant was weak in his selection of subordinates, many times favoring military associates from the war over talented and experienced politicians. Grant also protected close friends with Presidential power and pardoned person's who were convicted after serving a few months in prison. His failure to establish working political alliances in Congress allowed the scandals to spin out of control. At the conclusion of his second term, Grant wrote to Congress that "Failures have been errors of judgment, not of intent." Nepotism was rampant. Around 40 family relatives financially prospered while Grant was President.

There were eleven scandals associated with Grant's two terms as President of the United States. The main scandals included Black Friday in 1869 and the Whiskey Ring in 1875. The Crédit Mobilier is included as a Grant scandal; however, the origins actually began in 1864 during the Abraham Lincoln Administration and carried over into the Andrew Johnson Administration. The actual Crédit Mobilier scandal was exposed during the Grant Administration in 1872 as the result of political infighting between Congressman Oakes Ames and Congressman Henry S. McComb.

Administration and Cabinet

Supreme Court appointments

Grant appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Edwin M. Stanton – 1869 (died before taking seat)

- William Strong – 1870

- Joseph P. Bradley – 1870

- Ward Hunt – 1873

- Morrison Remick Waite (Chief Justice) – 1874

States admitted to the Union

- Colorado – August 1, 1876

Government agencies instituted

- Department of Justice (1870)

- Office of the Solicitor General (1870)

- "Advisory Board on Civil Service" (1871); after it expired in 1873, it became the role model for the "Civil Service Commission" instituted in 1883 by President Chester A. Arthur, a Grant faithful. (Today it is known as the Office of Personnel Management.)

- Office of the Surgeon General (1871)

- Army Weather Bureau (currently known as the National Weather Service) (1870)

- Yellow Stone National Park (1872)

Post-presidency

World tour 1877–1879

After the end of his second term in the White House, Grant spent over two years traveling the world with his wife. He traveled first to Liverpool, England onboard the Pennsylvania class steamship SS Indiana, subsequently visiting Scotland and Ireland; the crowds were enormous. The Grants dined with Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle and with Prince Bismarck in Germany. During the world tour it was noted that the Ulysses and his wife Julia had inexhaustible energy in all the many dinners and meetings with dignitaries. The Grant's were received with welcome by the public and remained popular everywhere they went. They also visited Russia, Egypt, the Holy Land, Siam (Thailand), and Burma.

In Japan, they were cordially received by Emperor Meiji and Empress Shōken at the Imperial Palace. Today in the Shibakoen section of Tokyo, a tree]] still stands that Grant planted during his stay. In 1879, the Meiji government of Japan announced the annexation of the Ryukyu Islands. China objected, and Grant was asked to arbitrate the matter. He decided that Japan's claim to the islands was stronger and ruled in Japan's favor. Grant also participated in a tea ceremony with the young Emperor Meiji.

Grant returned to the United States from Japan on board the Pacific Mail steamship City of Tokio. That year, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Wisconsin Medical School. Grant was the first United States President to travel around the world.

Third term attempt in 1880

In 1879, the "Stalwart" faction of the Republican Party led by Senator Roscoe Conkling sought to nominate Grant for a third term as president. He counted on strong support from the business men, the old soldiers, and the Methodist church. Publicly Grant said nothing, but privately he wanted the job and encouraged his men. His popularity was fading however, and while he received more than 300 votes in each of the 36 ballots of the 1880 convention, the nomination went to James A. Garfield. Grant campaigned for Garfield, who won by a very narrow margin. Grant supported his Stalwart ally Conkling against Garfield in the battle over patronage in spring 1881 that culminated in Conkling's resignation from office.

Bankruptcy

In 1881, Grant purchased a house in New York City and placed almost all of his financial assets into an investment banking partnership with Ferdinand Ward, as suggested by Grant's son Buck (Ulysses, Jr.), who was having success on Wall Street. In 1884 Ward swindled Grant (and other investors who had been encouraged by Grant), bankrupted the company, Grant & Ward, and fled.

Last days

Grant learned at the same time that he was suffering from throat cancer. Today, it is believed that Grant suffered from a T1N1 carcinoma of the tonsillar fossa. Grant and his family were left destitute; at the time retired U.S. Presidents were not given pensions, and Grant had forfeited his military pension when he assumed the office of President. Grant first wrote several articles on his Civil War campaigns for The Century Magazine, which were warmly received. Mark Twain offered Grant a generous contract for the publication of his memoirs, including 75% of the book's sales as royalties.

It was not until 1958 that Congress, believing it inappropriate that a former President or his wife might be poverty-stricken, passed a bill granting them a pension, still in effect today.

Terminally ill, Grant finished his memoir just a few days before his death. The Memoirs sold over 300,000 copies, earning the Grant family over $450,000. Twain promoted the book as "the most remarkable work of its kind since the Commentaries of Julius Caesar." Grant's memoir has been regarded by writers as diverse as Matthew Arnold and Gertrude Stein as one of the finest works of its kind ever written.

Ulysses S. Grant died on Thursday, July 23, 1885, at the age of 63 in Mount McGregor, Saratoga County, New York. His body lies in New York City's Riverside Park, beside that of his wife, in Grant's Tomb, the largest mausoleum in North America. It was originally interred in a vault in the same park, which was used until the current mausoleum was built. The Ulysses S. Grant Memorial honors Grant.

Cinema portrayals

Actors have played Ulysses S. Grant in 35 movies. Grant is third most popular President to be portrayed in movies, films, or cinema.

Portrayals include:

- The Birth of a Nation, 1915 silent epic movie, played by Donald Crisp.

- Only the Brave, 1930, played by Guy Oliver.

- They Died with their Boots On, 1941, played by Joseph Crehen (uncredited).

- The Horse Soldiers, 1959 John Wayne movie, played by Stan Jones.

- How the West Was Won, 1962, played by Harry Morgan.

- Lincoln, 1992, played by Rod Steiger.

- Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, 2007, played by Senator Fred Thompson

- Sherman's March, 2007, played by Harry Bulkeley.

Grant is often portrayed historically inaccurate in cinema or mass media as a scowling drunkard or placed in false historical events. One notable exception was by Kevin Kline in the 1999 film Wild, Wild, West. Kline consulted Grant scholar John Y. Simon for advice on how to play Grant, and portrays him as a formidable authority figure who has courage mixed with a hard-bitten sense of humor.

See also

- Grantism

- Grant's Farm

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- List of American Civil War generals

- U.S. Grant Home, Galena, Illinois

- Ulysses S. Grant Memorial

- Western Theater of the American Civil War

Notes

- ^ Simpson, Brooks D. (2000). Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph over Adversity, 1822-1865. New York: Houghton Mifflin. p. 3. ISBN 0-395-65994-9.

- See Skidmore (2005); Bunting (2004), Scaturro (1998), Smith (2001) and Simpson (1998); List of presidential rankings. Historians rank the 42 men who have held the office. AP via MSNBC. msn.com. Last visited February 16, 2009. See list of greatest presidents.

- "The Career of a Soldier". New York Times. July 24, 1885. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

On the 27th of April, 1822, in the village of Point Pleasant, Ohio, 25 miles above Cincinnati on the Ohio River, was born Hiram Ulysses Grant, the eldest of the six children of Jesse R. and Hannah Simpson Grant.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Simpson, p. 2

- Farina, William (2007). Ulysses S. Grant, 1861-1864: his rise from obscurity to military greatness. p. 13-14. Retrieved 02-07-2010.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Smith, Grant, p. 24.

- Smith, Grant, p. 83. In a letter to his wife Julia dated March 31, 1853, Grant wrote, "Why did you not tell me more about our dear little boys ? ... What does Fred. call Ulys. ? What does the S stand for in Ulys.'s name? In mine you know it does not stand for anything!" McFeely, p. 524, n. 2: "Grant himself never used more than 'S.'; others converted the single letter to 'Simpson.'

- McFeely, William S. (1981). Grant. p. 37.

- Ulysses S Grant Quotes on the Military Academy and the Mexican War

- Smith, p. 73.

- According to Smith, pp. 87-88, and Lewis, pp. 328-32, two of Grant's lieutenants corroborated this story and Buchanan himself confirmed it to another officer in a conversation during the Civil War. Years later, Grant told educator John Eaton, "the vice of intemperance had not a little to do with my decision to resign."

- McFeely, pp. 62-3. His wife's slaves were leased in St. Louis in 1860 after Grant gave up farming; during the war, she reclaimed one slave woman as her personal attendant when visiting Grant in camp. The land and cabin where Grant lived is now an animal conservation reserve, Grant's Farm, owned and operated by the Anheuser-Busch Company.

- McFeely, ch. 5.

- The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

- Hesseltine, chapter 6.

- Bruce Catton, The Coming Fury, page 327, 1961

- Faust, Patricia L. (1991). Historical times illustrated encyclopedia of the Civil War.

- Sifakis, Stewart (1998). Who Was Who in the Civil War.

- Sifakis, Stewart (1998). Who Was Who in the Civil War.

- McFeely, Willam S. (1981). Grant: A Biography. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 90–93.

- McFeely, Willam S. (1981). Grant: A Biography. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 97–98.

- "Fort Henry". Retrieved 02-03-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Smith, Professor Jean Edward (2001). Grant. pp. 156–158. Retrieved 02-02-10.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - McFeely, Willam S. (1981). Grant: A Biography. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 99–101.

- Gott, Kendall D., Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry—Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862, Stackpole books, 2003, ISBN 0-8117-0049-6.

- Eicher, David J., The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, Simon & Schuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- McFeely, Willam S. (1981). Grant: A Biography. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 111–113.

- McPherson, James M. (2005). Atlas of the Civil War.

- De Hass, Col Wills (1879). Alexander Kelly McClure (ed.). The annals of the war written by leading participants north and south. pp. 677–692.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Smith Ph.D., Jean Edward (2001). Grant. p. 185.

- Cunningham, O. Edward, Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862 (edited by Gary Joiner and Timothy Smith), Savas Beatie, 2007, ISBN 978-1-932714-27-2.

- McPherson, James M. (2005). Atlas of the Civil War.

- De Hass, Col Wills (1879). Alexander Kelly McClure (ed.). The annals of the war written by leading participants north and south. pp. 677–692.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Cunningham, O. Edward, Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862 (edited by Gary Joiner and Timothy Smith), Savas Beatie, 2007, ISBN 978-1-932714-27-2.

- McFeely, Willam S. (1981). Grant: A Biography. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 128–132.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed., The Civil War Battlefield Guide, 2nd ed., Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998, ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- McFeely, Willam S. (1981). Grant: A Biography. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 128–132.

- McFeely, Willam S. (1981). Grant: A Biography. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 128–132.

- Faust, Patricia L. (1991). Historical times illustrated encyclopedia of the Civil War.

- Grant's new command unified the Union command in the West for the first time since Henry W. Halleck vacated the erstwhile Department of the Mississippi to become general-in-chief. According to his memoirs, had he so wished, Grant could have chosen a version of the War Department order continuing Rosecrans in command of the Department of the Cumberland. See Grant, Memoirs (Lib. of Am., 1990), 403.

- ^ Bruce Catton, Grant Takes Command, pages 42-62, 1969

- ^ "The Chattanooga Campaign".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help); Text "http://www.civilwarhome.com/chattanoogasummary.htm" ignored (help) - Lloyd Lewis, Sherman: Fighting Prophet, 323.

- Eicher, David J., The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, Simon & Schuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Bruce Catton, Grant Takes Command, Chapter 8, Campaign plans and politics, 1969

- Bruce Catton, Grant Takes Command, page 181, 1969

- Bruce Catton, Grant Takes Command, page 183-191, 1969

- Bonekemper, Edward H., III, A Victor, Not a Butcher: Ulysses S. Grant's Overlooked Military Genius, Regnery, 2004, ISBN 0-89526-062-X.

- Bruce Catton, Grant Takes Command, pages 246, 248-249, 1969

- "Spotsylvania Court House". Retrieved 02-03-10.